Appendix:

Evidence

for the Classification of 21 Polity Upsweeps with regard to status as non-Core

marcher states

v. 3-30-2016 23502 words

https://irows.ucr.edu/cd/appendices/semipmarchers/semipmarchersapp.htm

Targaryen Marcher Lord

Excel data files of polity sizes: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Central System, South Asia, East Asia

Table

of Contents

§ Introduction

§ Typology of Territorial

Upsweeps

§ List of Polity Upsweeps

o Lagash

o Akkadia

o Mitanni

§

Egypt

o Hyksos

o Rome

o British

·

Shang

·

Western

Zhou

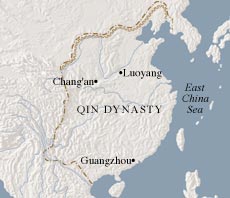

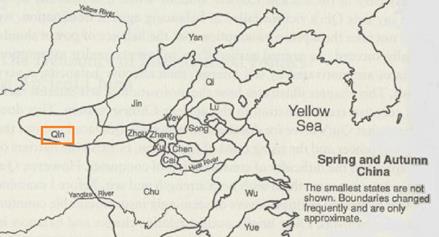

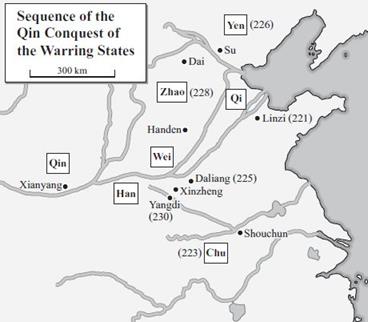

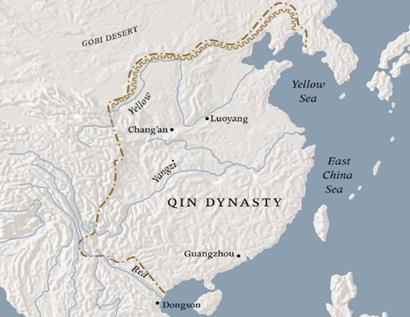

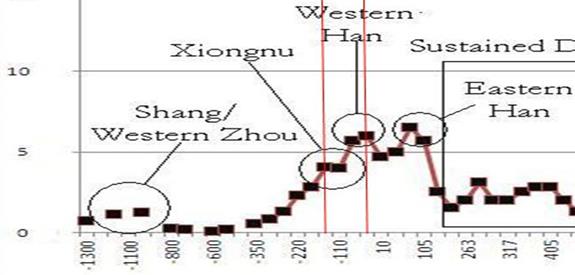

o Qin, Xiongnu, and Western Han

·

Qin

·

Xiongnu

o Sui-Tang

o Qing

o

Mauryan

Introduction

For each of the territorial upsweeps in the five political-military

networks we are studying we include a description of the evidence that is

relevant regarding whether or not the polity or polities that carried out the

upsweep were semiperipheral or peripheral marcher states. This involves

determining the world-system position of the polity in the centuries before it carried out the territorial upsweep. Our

definition of non-core marcher states and of empirical indicators of

world-system position are contained in the main paper. Here we summarize the

relevant scholarly literature to determine what kinds of evidence might exist

that is relevant to the determination we are trying to make

One problem we encounter

is that, because semiperipherality is a relational

concept, the determination of whether or not a particular polity was

semiperipheral or not depends on the nature of institutionalized power in the

core/periphery structures that existed in the particular world-systems of which

that polity is a part. Matters are also complicated by the fact that polities

often exist in a context in which they are interacting with more than one core

region and so their position relative to these two core regions may be different. We try to address these issues in the

summaries that follow.

Types

of Territorial Upsweeps

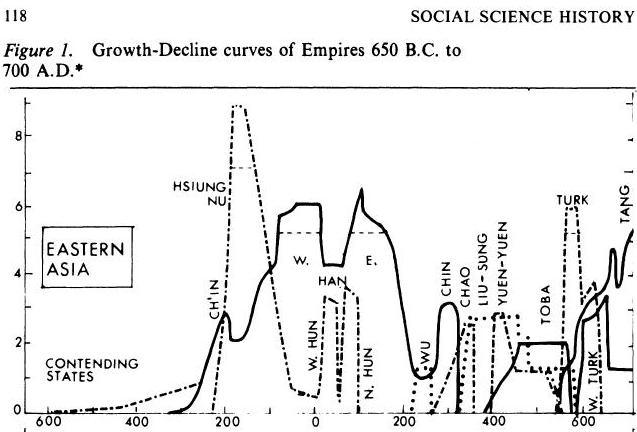

So we find five different kinds of

upsweeps:

- semiperipheral

marcher state (SMS), a

polity that is in a semiperipheral position within a regional system conquers

a large area and produces a territorial upsweep;

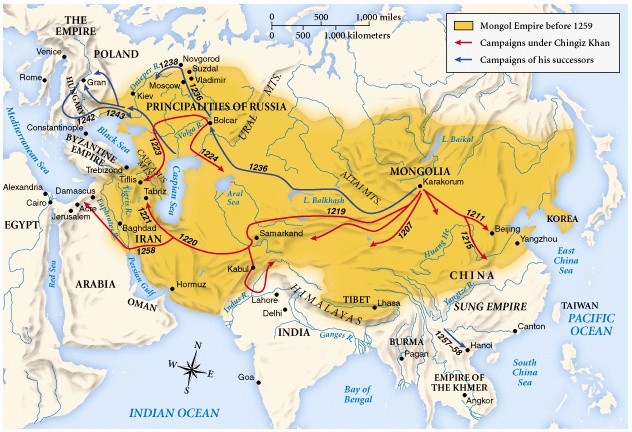

- peripheral marcher

state (PMS), in

which a polity that is peripheral in a regional system conquers the core,

(e.g. the Mongol Empire).

- mirror-empire (ME), in which

a core state that is under pressure from a non-core polity carries out a

territorial expansion

- internal revolt (IR), a state formed by an internal

ethnic or class rebellion, such as what Yoffee

(1991) argues for the Akkadian Empire, or the Mamluk

Empire

- internal dynastic

change (IDC), a coup

carried out by a rising faction within

the ruling class of a state leads to a territorial expansion[1]

List of 21 Polity Upsweeps

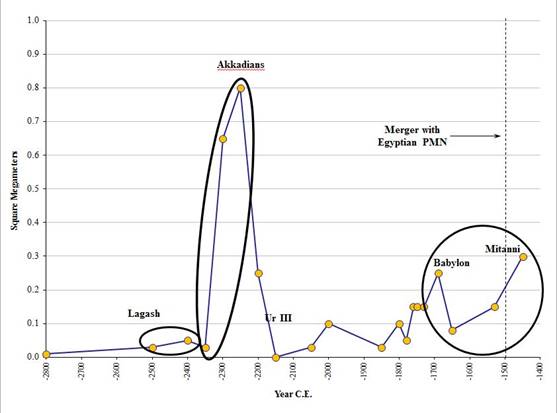

Mesopotamia 2800 BCE to 1500 BCE

|

Year |

Size |

Polity name |

|

-2400 |

0.05 |

Lagash |

|

-2250 |

0.8 |

Akkadia |

|

-1450 |

0.3 |

Mitanni |

Egypt 2850 BCE to 1500 BCE

|

Year |

Size |

Polity name |

|

-2400 |

0.4 |

5th Dynasty |

|

-1850 |

0.5 |

12th Dynasty |

|

-1650 |

0.65 |

Hyksos |

Central PMN 1500 BCE to 1991AD

|

Year |

Size |

Polity name(s) |

|

-1450 |

1 |

18th Dynasty |

|

-670 |

1.4 |

Neo-Assyrian |

|

-480 |

5.4 |

Achaemenid Persia |

|

117 |

‘5 |

Rome |

|

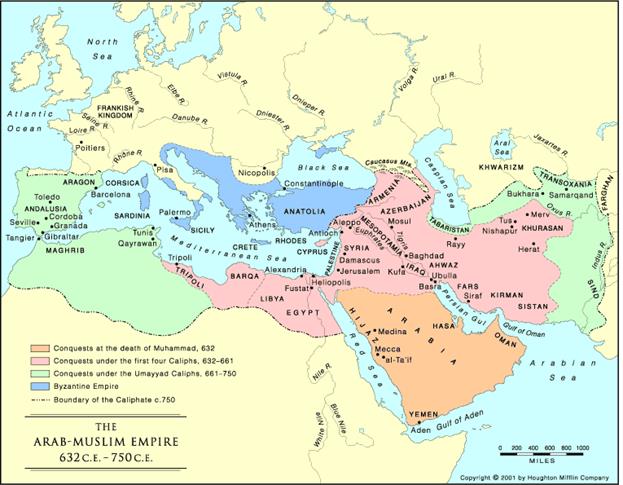

750 |

11.1 |

Islamic Empires |

|

1294 |

29.4 |

Mongol-Yuan |

|

1936 |

34.5 |

Britain |

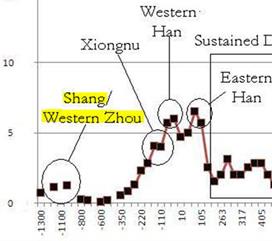

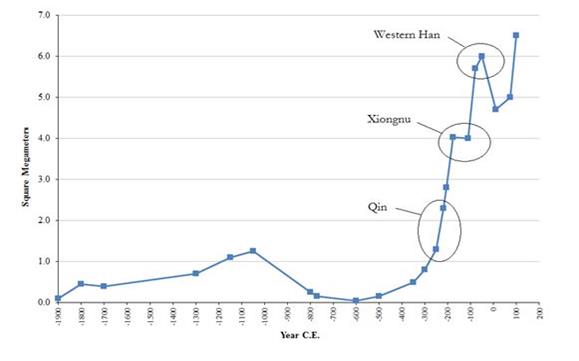

East Asia 1300 BCE to 1830 AD

|

Year |

Size |

Polity name(s) |

|

-1050 |

1.25 |

Shang/Western

Zhou (Chou)* |

|

-176 |

4.03 |

Qin/Western

Han/Xiongnu * |

|

-50 |

6 |

Western Han |

|

100 |

6.5 |

Eastern (Later)

Han |

|

624 |

4 |

E. Turks |

|

660 |

4.9 |

Sui-Tang |

|

1294 |

29.4 |

Mongol-Yuan

(already listed above in Central PMN) |

|

1790 |

14.7 |

Qing |

South Asia 420 BCE to 1008 AD

|

Year |

Size |

Polity name |

|

-260 |

3.72 |

Mauryan |

* If there is more than one polity name and the names are

separated by a / this means that the upsweep in territorial size is a composite upsweep involving more than

one polity. In order to be counted as a part of an upsweep a polity must attain

a size that is larger than the earlier peak size of polities.

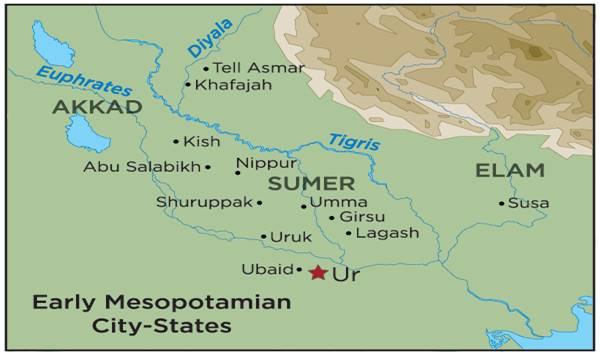

Mesopotamia: 2800 BCE to 1500 BCE

Lagash

Lagash was in southern Mesopotamia west of Uruk, south of Kish, and east of Susa. The city-state of

Lagash was made up of two towns, Lagash (Tell al-Hiba) and Girsu

(Tellow) (Yoffee 2006:57).

The main language of Lagash was Sumerian. Lagash

dates from somewhere in the third millennium BCE, about a millennium after Susa

and Uruk. Lagash was involved in a struggle for

control of the region with other city-states. Flannery calls it “subordinate”

to Kish before the area was unified (see below).

|

Table: Estimated Lagash

Polity Sizes |

||||||

|

Polity |

Date |

Location |

Approximate Size |

Estimated Population |

Type |

Source |

|

Lagash (al-Hiba) |

Third mill. |

Eastern alluvium, S.

Mesopotamia |

Around 600 hectares |

|

|

Algaze (2005:143) |

|

Lagash |

2500 BCE |

Southern Mesopotamia |

3200 sq kilometers |

105,000 |

Third generation regional state |

Wright (2006: 15-16) |

|

Lagash includes: Tell al Hiba Tello (Girsu) |

2500-2000 |

Southern Mesopotamia |

3000 sq km 4 sq km 80 hectares |

120,000 75,000 15,000 |

City-State |

Table in Yoffee (2006:43) |

The city of Lagash (Tell al-Hiba)

was the largest city in the region in the mid-third millennium. It’s areal size is estimated at 400 hectares, with a population

estimated at 75,000 (Yoffee 2006: 43, 57). With

regard to polity size, the city-state of Lagash became the largest in the

region once it had unified the area in the mid-third millennium. Its

territorial size has been estimated at more than 3000 km2, with

120,000 estimated population (Yoffee 2006: 43, 57;

see also Marcus 1998: 80-81).

The consensus of several scholars is

that Lagash was part of a number of city-states that were going through periods

of unification and independence from each other during the period before and

after the Akkadian empire. Marcus (1998:86) states that "Strong rulers

fought incessantly to incorporate their neighbors into a larger polity; weak

rulers did whatever they could to retain their autonomy. It might be more

accurate to describe such periods as consisting of relentless attempts to

create larger polities by alliance or conquest..."

A ruler named Eanatum

became King of both Lagash and Kish. Eanatum

[elsewhere spelled Eannatum] was the grandson of the

first king of Lagash, Ur-Nanshe. Eanatum

conquered all of southern Mesopotamia, including Uruk,

made Umma pay tribute, and also conquered Elam.

Flannery (1998:20) states that Lagash “shows a cyclic ‘rise and fall’ and uses

the word "subordinate" to describe Lagash in relation to the

pre-Sargon city-state of Kish: “Lagash was for a time subordinate to Mesalim of Kish,” and then it "rose to prominence

under a ruler named Eanatum, who assumed the kingship

of both Lagash and Kish.”

It

would appear that Lagash was in the core region of Mesopotamian city-states. in

about -2400. Eanatum,

grandson of Ur-Nanshe, was a king of Lagash who

conquered all of Sumer, including Ur, Nippur, Akshak

(controlled by Zuzu), Larsa,

and Uruk (controlled by Enshakushanna,

who is on the King List). He also annexed the kingdom of Kish, which regained

its independence after his death. He made Umma a

tributary, where every person had to pay a certain amount of grain into the

treasury of the goddess Nina and the god Ingurisa

after personally commanding an army to subjugate the city. Eannatum expanded

his influence beyond the boundaries of Sumer. He conquered parts of Elam,

including the city Az on the Persian Gulf, allegedly

smote Shubur, and demanded tribute as far as Mari.

However, often parts of his empire were revolting.

In c.2450 BC, Lagash and the

neighboring city of Umma fell out with each other

after a border dispute. As described in Stele of the Vultures the current king

of Lagash, Eannatum, inspired by the patron god of

his city, Ningirsu, set out with his army to defeat

the nearby city. Initial details of the battle are unclear, but the Stele is

able to portray a few vague details about the event. According the Stele's

engravings, when the two sides met each other in the field, Eannatum

dismounted from his chariot and proceeded to lead his men on foot. After

lowering their spears, the Lagash army advanced upon the army from Umma in a dense Phalanx. After a brief clash, Eannatum and his army had gained victory over the army of Umma. Despite having been struck in the eye by an arrow,

the king of Lagash lived on to enjoy his army's victory.

Eanatum’s

grandfather was Ur-Nanshe, the first king of the

First Dynasty of Lagash in the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period III. Ur-Nanshe was probably not of royal lineage, since in his

inscriptions he refers to his father as one Gunidu without an accompanying royal title.

The fact that the name does appear in offering lists from the time of the later

kings Lugalanda and Uruinimgina

suggests that Gunidu nevertheless held an important, possibly religious, office

in Lagash. The notion that Lagash was

subordinate to Kish before the rise of Eanatum, and

the possibility that

Eanatum’s family was not a royal lineage before

the rise of his grandfather Ur-Nanshe to kingship

might suggest the possibility that Lagash was semiperipheral vis-à-vis the other

polities in Mesopotamia before Eanatum’s conquest.

But these are slender reeds, and we prefer to conclude that there is not enough

evidence in the case of Lagash one way or the other. These features are more consistent with the

notion that Lagash was a case of Internal Dynastic Change in which a rising

faction of the ruling class led to the territorial upsweep.

References:

Algaze, Guillermo. 2005. The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early

Mesopotamian Civilization, 2nd Ed. Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

Beaujard,

Philippe. 2012. Les

mondes de l’Océan Indean, tome 1: De la formation de l’état au premier système-

monde

afro-eurasien. Paris: Armand Colin.

Cuneiform

Digital Library Initiative, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford,

http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=ur-nanshe

Cooper, Jerrold S. 1983 “Reconstructing

history from ancient inscriptions: the Lagash-Umma

border

conflict” Sources from the Ancient Near East 2,1; Malibu, CA: Undena Publications.

Flannery, Kent V. 1998. “The Ground

Plans of Archaic States.” Pp. 15-57 in Archaic

States, Gary M. Feinman and Joyce Marcus, eds.

Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Marcus, Joyce. 1988. “The Peaks and

Valleys of Ancient States: An Extension of the Dynamic Model.” Pp. 59-94 in Archaic States, Gary M. Feinman and Joyce Marcus, eds. Santa Fe, NM: School of

American Research Press.

Wright, Henry T. 2006. “Atlas of

Chiefdoms and Early States.” Structure and Dynamics: eJournal

of Anthropological and Related Sciences 1(4): 1-17 Avail:

http://repositories.cdlib.org/imbs/socdyn/sdeas/vol1/iss4/art1

Yoffee, Norman. 2006. Myths of the Archaic State: Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States,

and Civilizations. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Recent

scholarship on the origins of the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia (ca 2350 BCE)

has not differed much from the earlier, and in part, speculative positions held

by the preeminent authors (e.g., Algaze, Liverani, Weiss, and Yoffee).

There are two major reasons for this relative stasis: 1) the decades-long U.S.

and Iraq conflict limited archaeological research, and may have destroyed

unknown artifacts; and 2) the limited amount of written documentation from the

period, and the difficulty in separating historical fact from myth and/or

propaganda.

It is therefore not necessary to

revise the position taken by Chase-Dunn et

al in 2006 – the Akkadian upward sweep may have been initiated and/or

facilitated by an ethnic revolt of the Semitic-speaking people against the

Sumerian-speakers. The scholars essentially agree that the Akkadians had been

pastoralists from the Arabian desert who migrated into the Mesopotamian region

in waves, probably climate-induced or influenced (Weiss et al , around

the 3rd millennium. They settled in central Mesopotamia (around the

city of Kish) and in northern Mesopotamia (present day Syria) but they also

inhabited the southern section where the Sumerians were the majority. Liverani (2006) describes an ethnocentrism held by the

“urban” Sumerians against the “nomadic” peoples, enflamed by fear of attack and

migration from the latter. Yoffee (2005), taking a

more sanguine view, asserting that the ethno-linguistic differences were not

sources of serious conflict. The historical record is unclear on how much

conflict, if any, existed between the two groups at the time of the Akkadian

upward sweep, and it must be noted that over half a millennium had passed since

the major Semitic migration into the region.

The Semitic pastoralists had

probably been peripheral in the Mesopotamian world-system prior to their settlement

in the 3rd Millennium. The area they settled in, centered around the

city of Kish, was semi-peripheral to the Uruk-based

southern regional core, although that hegemony was largely replaced by

internecine city-state conflict and then a measure of unification under Lugalzagesi in the south just prior to Sargon’s conquest of

the area. Kish was an important trade node between the southern and northern

areas (Steinkeller 1993) and was also one of the

sites that was granted divine kinship after the mythical flood. So it is not

incorrect to say that the Akkadian Empire was an example of the rise of a

semiperipheral marcher state. But the Semitic people didn’t simply ride into

the area and vanquish the core. Instead, they settled in the area in waves over

centuries and likely seized the opportunity to take control of a major, but

semiperipheral city-state when the advantage became theirs. It seems possible

that Sargon may have become King of Kish by coup d’etat.

The story of his ascent to

power in the city is shrouded in a legend in which Sargon, of meager beginnings

and then a cupbearer to the king Ur-Zababa, was a

usurper to the throne amidst a power struggle and possibly an assassination

attempt on his life by the king (Chevalas 2006: 84,

167; Cooper 1993: 18; Levin 2002). Powerlessness/subordination against the

temple ruling elite may have been a factor as “a kind of revenge of those

kin-based elites that had been set aside by the impersonal administration of

the temple institution” (Liverani 2006: 75). Yoffee, by contrast, states that “Sargon forged the first

pan-Mesopotamian state…having begun his ascent to power from the venerable city

of Kish (which he had conquered)…[italics are mine] (Yoffee

2006: 142).

There is general agreement that the

Akkadian Empire was more militant and territorially expansive than the

city-states they conquered had been. Mann’s (1986) contention that advanced

military technology was an important factor in the Akkadian rise was also

mentioned by the Russian Assyriologist, Igor Diakonoff (1973).

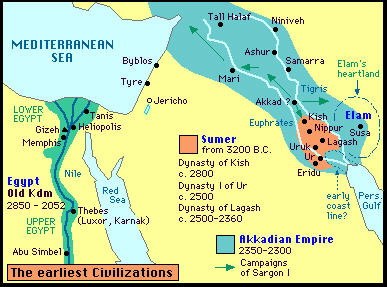

Mesopotamia

was an unbounded geographic area, but is in the Tigris and Euphrates alluvium,

and can be divided into northern, central, and southern regions, or upper and

lower. The north consisted of the area in the Habur

Plains in what is now Syria, the center was in central Iraq, the south near the

Persian Gulf (Figure 1). Southern Mesopotamia in the latter part of the Early

Dynastic period, ca. 2500-2350 BCE, was composed of multiple independent

city-states each with their own capital and a hinterland of smaller population

centers. Central Mesopotamia, by contrast, “formed a single territorial state

or, perhaps more accurately, a single political configuration” (Steinkeller 1993: 117). The largest cities in each area

were Tell Leilan in the north, Kish in the center,

and Uruk in the south (Table 1). Kish was the center

of a commercial network linking Upper and Lower Mesopotamia and was the defacto capital of central Mesopotamia (Steinkeller

1993). The central and southern city-states were engaged in regular internecine

conflict over access to arable land and trade routes. While a degree of

cultural unity existed across Mesopotamia, there was not a single unified

political system under central control until the Akkadian Empire was formed in

the late third millennium BCE (Yoffee 2006: 56-57).

According to Algaze

(2005), prior to the Akkadian system, Mesopotamia had a world-system, a

“complex, albeit loosely integrated, supraregional

interaction system” (p. 5) broken into competing regions, centered in southern

Mesopotamia (the largest settlements, population density, complexity), in the

Tigris and Euphrates alluvium, in the Uruk period (4th

millennium BCE). The Sumerian speaking people of the southern system colonized

the Susiana plain in SW Iran and the SW Syrian plateau, to take advantage of

abundant resources. Uruk enclaves and outposts were

established at key points in the periphery of the S. Mespotamia

Uruk system. Evidence exists for

interaction/integration from similar pottery and other artifacts. The Susiana

plain had some large settlements, Susa (25 ha) and Chogha

Mish (18 ha), that “developed in ways that were increasingly analogous to those

of the alluvial lowlands of southern Iraq (p. 11). But the Susiana plain seems

to have been politically independent of the SW Iraq system, and Susa and Chogha Mish politically independent of each other. By the

end of the Uruk period, Chogha

Mish had collapsed and Susa had a significant population reduction (p.18). In Syro-Mesopotamia, Tell Brak was

very large in the Late Chalcolithic period, at least 65 hectares, up to 160 if

you include the surrounding settlements (p. 138). Algaze

(p.142) notes that the Late Chalcolithic period system was only a second-order

level of complexity – large center surrounded by small village/hamlets. Tell

al-Hawa is similar, both with less complexity than

the southern Mesopotamia system in the same period (Middle Uruk

in south). Three-tier settlement systems appear in the north only after contact

with Uruk societies. Algaze

notes that Warka, what I think must also called Warku, was four times larger than the second-tier of

settlements, violating “Zipf’s Law” that states urban

populations are ranked in tiers with each one double the size of the next

(2005:141). Umma, and a site nearby called Umm al-Aqarib, both in S. Mesopotamia alluvium, are still being

excavated, but Algaze thinks they will be the

“missing” second-tier of settlements adhering to Zipf’s

Law (see #14 above). The estimate of 120 hectares is based on that formula, not

on excavations. Tablets found in the sites proclaim the economic importance of Umma in the Late Uruk period,

generating Algaze’s belief it may be second only to Warka in importance to the southern system (p.141).

But the competing city-states that emerged

across S. Mesopotamia in the mid-to late 4th millennium “was the

first time that the southern polities, both singly and in the aggregate,

surpassed contemporary societies elsewhere in southwest Asia in terms of their

scale and degree of internal differentiation, both social and economic” (Algaze 2005: ix). The fertility of the soil, water

transport, technology of accounting and writing systems were all advantages the

southern alluvium held over the peripheral areas (pp.147-149). It was during

this time that societies in the alluvium engaged in “an intense process of

expansion…[that] may be considered to represent the earliest well-attested

example of the cyclical ‘momentum toward empire’” (Algaze

2005: 6). Algaze states that the Uruk

Expansion in the 4th millennium could be the “Mesopotamia’s—and the

world’s—first imperial venture” and

“whether or not the Uruk phenomenon as Mespotamia’s first empire, it certainly was the world’s

earliest ‘world system’(p. 145). Stein disagrees, providing a “distance-parity”

model that argues that premodern control over socities

drops off with distance due to transportation (p.146) The Uruk

sites in the periphery were “gateways” located at nodes along exchange networks

between core and periphery, raw materials or semiprocessed

commodities from the periphery in exchange for fully processed goods from the

core, to the benefit of the core (145). By world system, he means an assymetrical economic interaction across societies of

varying complexity, DOL, technology, social control, administration (defn 145). The southern system also had settlements that

were close enough in distance to facilitate daily contact, and cultural

sharing, unlike the settlements on the Syro-Mesopotamian

Plains (p.142). As the southern system rose, the northern fell, by the

transition from the 4th to 3rd millennium the northern

settlements had effectively disappeared and would not reappear until the second

quarter of the third millennium. Warka reached 600

hectares at this time, and Al-Hiba in the eastern edge of the alluvium almost

as large (p. 143).

The Akkadian Empire originated in

the city of Kish in central Mesopotamia in the late 24th century

BCE. It was created by Semitic-speaking people, growing through conquest to

include Sumerian-speaking areas. There were differences between the social

organization of the Semitic-speaking people that formed the Akkadian Empire in

the center of the region and the Sumerian-speakers in the south. The Semites

came from the Arabian desert, and were distinguished by their pastoral mode of

production, kinship-based property structure, and tribal political

organization, and settled mostly in the valley. The Sumerians, in contrast,

lived in the delta, practiced irrigated agriculture, had a collective structure

for labor and property, in a temple-guided system (Liverani

1993; Steinkeller 1993).

But the Semites did not migrate to

the area and immediately conquer the existing system; instead, they had settled

in Mesopotamia “well before Sargon [the first leader of the Akkadian Empire],

since the beginning of the onomastic and linguistic documentation (Liverani 1993: 2-3). Steinkeller

contends that around the beginning of the 3rd millennium BCE, the

end of Uruk IV and through the Uruk

III period [3300-2900 BCE], “there occurred, probably in several waves and over

an extended period of time, a major intrusion of Semitic peoples into Syria and

Upper Mesopotamia. One of these peoples, probably the ancestors of the

Akkadians, migrated into the Diyala Region and

northern Babylonia, eventually settling there and adopting the urban mode of

life.” This immigration of Semitic people effectively ended the Uruk presence in the area as Semitic institutions were

dominant during the Early Dynastic period [29th century BCE] (1993:

115-116).

The reason for the migration of the

Semitic pastoralists from the desert is unclear, but follows a pattern of

urbanization that occurred in the region during the 3rd millennium.

It could have been caused by a changing climate as the region experienced severe

aridity and century-long droughts that accelerating beginning around 3500 BCE,

with a minimum of rainfall from 3200-2900 BCE and desertification of the Habur plains between 2200 and 1900 BCE. (Algaze 2001; Brooks 2006: 38; Fagan 2004; Weiss et al. 1993).

There is some evidence to suggest

that the possibility that Semitic people were part of the Mesopotamian

world-system prior to the beginning of the third millennium BCE. There was

extensive Uruk colonization during the Late Uruk period throughout the area, including the area near to

where the Semitic people migrated from, established at least in part to

facilitate material exchange, particularly as a means to acquire prestige goods

for elites (Algaze 2001; Liverani

2006; Weiss and Courty 1993: 132). For Algaze (2001), the Uruk informal

empire was large and asymmetrical, but this seems to be a minority viewpoint

(Rothman 2001). Steinkeller (1993) disagrees with the

intensity and reach of Uruk control, but he does

contend that control over some areas was likely. Steinkeller

also speculates that the Diyala area in which the

Semitic people had settled was included in the Kish-based kingdom during the

Early Dynastic period (1993: 119-120).

But there is little evidence documenting the type of relationship that

involved the Semitic pastoralists prior to their movement into the region, and

it is unclear what resources they controlled, beyond sheep, that were valued by

the core of the Mesopotamian system. Once they settled in the region, however,

they were most likely in a semi-peripheral or peripheral position. Although Steinkeller’s assertion that “we have convincing evidence

that the institutions of chattel slavery and villeinage

had been known in northern Babylonia” during this period, there is no

indication that Semitic people were involved (1993: 121).

There is also little documentation

regarding their ascent to power once they arrived, beyond the story of Sargon,

the originator and first leader of the Akkadian Empire, that is. Sargon’s tale

is shrouded in legend and myth, some of which was created by his own

administration or written centuries later. Scholars generally agree that Sargon

came from the area around the city of Kish in central Mesopotamia. Kish was a

city-state that formed upon the “merger” of independent villages, with an

approximate size of 5.5km2 and a population of 60,000 during the

second half of the 3rd millennium (Yoffee

2006: 43, 57). Sargon was of relatively meager beginnings and rose through the

administration in the city of Kish. (Legend has Sargon as cupbearer to the king

of Kish, Ur-Zababa) (Chevalas

2006: 84, 167, Levin 2002). Not being part of the royal family whose authority

was divine, Sargon became king of Kish as a usurper to the throne, but how he

took power is unspecified, although legend reveals a struggle for power between

the king and the aspirant, and possibly an assassination attempt on Sargon by

the Ur-Zababa, as told in the legend “Curse of Akkad”

(Cooper 1993: 18; Levin 2002). (Liverani (2004: 96)

notes that most protagonists in tales from this time period were usurpers,

rising to power outside of the normal route and coming from modest

backgrounds). Powerlessness against the temple ruling elite may have been a

factor as “a kind of revenge of those kin-based elites that had been set aside

by the impersonal administration of the temple institution” (Liverani 2006: 75). Yoffee, by

contrast, states that “Sargon forged the first pan-Mesopotamian state…having

begun his ascent to power from the venerable city of Kish (which he had

conquered)…[italics are mine] (Yoffee 2006: 142).

Having taken the city of Kish,

Sargon—his taken name, meaning “True King”—conquered the southern Mesopotamian

region that had been unified under Lugal-zagesi, the

king of Umma who, around 2300 BCE, had gained

hegemony by force or coalition building over the cities of Uruk,

Ur, Umma, and Lagash (Steinkeller

1993). Sargon then went north,

conquering Mari, Ebla, Ashur, and Nineveh, and pushing into Anatolia and the

Mediterranean (Levin 2002). He may have had a standing army of around 5400

people (Van De Mieroop 2007: 64).

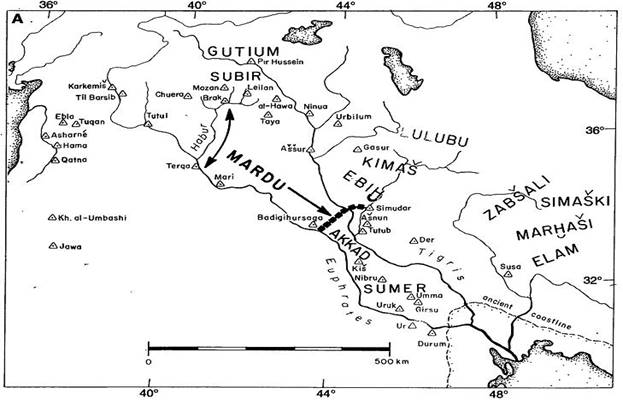

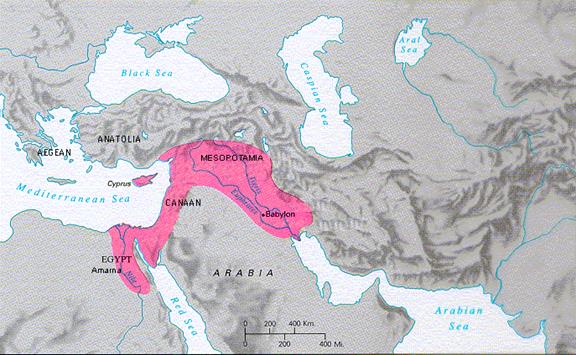

Figure 1: Syro-Mesopotamia,

2600 to 2000 BCE. (Arrows indicate tribal pastoralist Amorite seasonal

north-south transhumance before their movement down the Euphrates and the

Tigris. The Repeller of the Amorites wall of

fortresses was constructed from about 2054 to 2030 BCE from Badigihursaga

to Simudar to control Amorite infiltration.) Source:

Weiss et al. 1993b

Figure 1: Syro-Mesopotamia,

2600 to 2000 BCE. (Arrows indicate tribal pastoralist Amorite seasonal

north-south transhumance before their movement down the Euphrates and the

Tigris. The Repeller of the Amorites wall of

fortresses was constructed from about 2054 to 2030 BCE from Badigihursaga

to Simudar to control Amorite infiltration.) Source:

Weiss et al. 1993b

Sargon moved his capital from the

city of Kish to Akkad (also Agade) (location unknown) and proclaimed himself

“King of Sumer and Akkad,” adding this to his previous title “King of Kish.”

(King of Kish meant a divinely authorized ruler over all of Sumer and was

distinct from the kingship of the city of Kish, although the city of Kish was

one of the cities where kingship was lowered from heaven after the flood,

according to the Sumerian King List). This title came to mean “king of

everything,” changing to “King of the Four Corners of the Universe” during

Sargon’s grandson Naram-Sin (Michalowski 1993: 88).

Sargon was Semitic and adapted the Sumerian cuneiform script to his language,

which became known as Akkadian (Levin 2002). Steinkeller

(1993) contends that the central Mesopotamian region was a distinct cultural

entity, Akkadian, differing from the south that was Sumerian, but Yoffee (1998, 2001) disagrees, seeing much integration of

people as well as Akkadian being the official administrative language of the

entire region. Liverani (1993) attributes the claims

of ethno-linguistic conflicts to an earlier historical tradition, and minimizes

their impact, stating that “the ethnic factor had a limited and indirect

relevance on the organization of states, on their politics and mutual

relationships” (p. 2).

But there was clearly ethnic disdain

in the region between the people of the core and periphery. Liverani

(2006) is worth quoting at length:

The most

recurrent [mental maps] are those that contrast nomads to the sedentary people

and the alluvium to the mountains. The pastoral people of the steppe (the Martu) and of the mountains (the Guti)

are characterized by the very absence of the most basic traits of urban

culture. They have no houses, they have not tombs, they do not know

agriculture, and they do not know the rites of the cult. It is an ethnocentric

vision that aims to strengthen the self-esteem of those living in a world that

is culturally superior, but that is potentially threatened by the insistent and

violent pressures of foreign peoples. (P. 65)

The core also clearly desired

resources from the periphery, such as wood, metal, and stone, that were not

available in the alluvium (ibid, 65-66).

Liverani

points out that recent scholars contend that the Akkadian empire was not the

first empire, that distinction could be applied to Uruk

or Ebla in the Sumerian south prior to the Akkadian emergence. But “the

originality of Akkad would consist in a “heroic” and warring kingship, quite

different from the Sumerian idea of the ensi

who administered in the god’s name the large farm that was the city-state”

(1993: 4, see also Nissen 1993). Indeed, “for the

first time, the power basis was created for large military actions against

neighboring areas” (Nissen 1993: 97).

|

Table 1: Estimated Mesopotamia City Sizes |

|||||

|

City Name |

Period |

Area |

Land |

Population |

Source |

|

Tell Leilan |

mid 6th-2nd Millennium |

North |

75-100 hectares max |

|

Weiss et al. 1993 |

|

Uruk |

3200 BCE |

South |

250 ha |

20,000 |

Yoffee 2006 |

|

Kish |

2500-2000 BCE |

Central |

550 ha |

60,000 |

Yoffee 2006 |

|

Lagash (Tell al-Hiba) |

2500-2000 BCE |

South |

400 ha |

75,000 |

Yoffee 2006 |

References:

Algaze, Guillermo. 2001. “The Prehistory of

Imperialism: The Case of Uruk Period Mesopotamia.”

Pp. 27-83 in Uruk Mesopotamia & Its

Neighbors: Cross-Cultural Interactions in the Era of State Formation,

edited by M. S. Rothman. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

______. 2005. The Uruk

World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization, 2nd

Ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Brooks, Nick. 2006. “Cultural Responses

to Aridity in the Middle Holocene and Increased Social Complexity.” Quaternary

International 151: 29-49.

Chavalas, ed. 2006. The Ancient Near East:

Historical Sources in Translation.

Cooper, Jerrold S. 1993. “Paradigm and Propoganda: The Dynasty of Akkade

in the 21st Century.” Pp. 11-23 in in Akkad, The First World

Empire: Structure, Ideology, Traditions, edited by M. Liverani.

Padova, Italy: Tipografia Poligrafica Moderna.

Diakonoff, Igor M. 1973. "The Rise of the Despotic State in

Ancient Mesopotamia." Pp. 173-203

in I. M. Diakonoff (ed.) Ancient Mesopotamia, edited by I. M. Diakonoff,

trans by G. M. Sergheyev Walluf

bei Weisbaden: Dr. Martin Sandig.

Fagan, Brian. 2004. The Long Summer:

How Climate Changed Civilization. New York: Basic Books.

Liverani, Mario. 1993. “Introduction.” Pp. 1-10

in Akkad, The First World Empire: Structure, Ideology, Traditions,

edited by M. Liverani. Padova,

Italy: Tipografia Poligrafica

Moderna.

______. 2004. Myths and Politics in

Ancient Near Eastern Historiography, edited and introduced by Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

______. 2006. Uruk:

The First City, edited and translated by Z. Bahrani

and M. Van De Mieroop. London: Equinox.

Michalowski, Piotr. “Memory and Deed:

The Historiography of the Political Expansion of the Akkad State.” Pp. 69-90 in

Akkad, The First World Empire: Structure, Ideology, Traditions, edited

by M. Liverani. Padova,

Italy: Tipografia Poligrafica

Moderna.

Nissen, Hans J. 1993. “Settlement Patterns and

Material Culture of the Akkadian Period: Continuity and Discontinuity.” Pp.

91-106 in Akkad, The First World Empire: Structure, Ideology, Traditions,

edited by M. Liverani. Padova,

Italy: Tipografia Poligrafica

Moderna.

Rothman, Mitchell S. 2001. “The Local

and the Regional: An Introduction.” Pp. 3-26 in Uruk

Mesopotamia & Its Neighbors: Cross-Cultural Interactions in the Era of

State Formation, edited by M. S. Rothman. Santa Fe, NM: School of American

Research Press.

Steinkeller, Piotr. 1993. “Early Political Developments

in Mesopotamia and the Origins of the Sargonic

Empire.” Pp. 107-129 in Akkad, The First World Empire: Structure, Ideology,

Traditions, edited by M. Liverani. Padova, Italy: Tipografia Poligrafica Moderna.

Van De Mieroop.

2007. A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC. 2nd

Edition. Blackwell.

Yoffee, Norman. 1979. “The Decline and Rise of

Mesopotamian Civilization: An Ethnoarchaeological

Perspective on the Evolution of Social Complexity.” American Antiquity 44(1):

5-35.

______. 1998. The Collapse of Ancient

Mesopotamian States and Civilization. Pp. 44-68 in The Collapse of

Ancient States and Civilizations, edited by Norman Yoffee

and George L. Cowgill. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

______.

2006. Myths of the Archaic State: Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States,

and Civilizations. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Weiss, Harvey and Marie-Agnès Courty. 1993a. “The Genesis

and Collapse of the Akkadian Empire: The Accidental Refraction of Historical

Law.” Pp. 131-155 in Akkad, The First World Empire: Structure, Ideology,

Traditions, edited by M. Liverani. Padova, Italy: Tipografia Poligrafica Moderna.

Weiss, H., M.-A Courty,

W. Wetterstrom, F. Guichard,

L. Senior, R. Meadow, and A. Curnow. 1993b. “The Genesis and Collapse of Third

Millennium North Mesopotamian Civilization.” Science 261(5124):

995-1004.

The Mitanni occupied the area of the northern Euphrates

steppe between the Euphrates and Tigris, an area the Assyrians called Hanigalbar. Its capital, Washukkanni,

lay at the head of the Khabur River. The origins of

the Mitanni are uncertain but seem closely related to the history of the Hurrians. The Hurrians appear to

have been a people given to migration or clan travel. The archaeological

records suggest that the Hurrians formed in Sumer

small groups of immigrants comparable to Armenians in modern Iraq. There is

evidence that colonies of Hurrians had been extant in

various parts of Mesopotamia for millennia. The Hurrians

inflated their numbers in the Syrian town of Alalah

and formed the majority of population in 1800 B.C. It was probably around this

time that a warrior caste of Aryan (Indo-Iranian) dynasts came to impose

themselves on the Hurrian people and become a new aristocracy in command of war

and government. We do not know when and how the Indo-Aryans came to be mixed

with the Hurrians and took control over them, but

there is little doubt that, at least during the fifteenth and fourteenth

centuries B.C., they were settled among them as a leading aristocracy. The

names of several Mitannian kings, such as Mattiwaza and Tushratta, and the

term mariannu, which is applied to a category of

warriors, are most probably of Indo-European origin. Moreover, in a treaty

between Mitannians and Hittites, the gods Mitrasil, Arunasil, Indar and Nasattyana – which are,

of course, the well-known Aryan gods Mithra, Varuna, Indra and the Nasatyas – are

invoked side by side with Theshup (Hurrian god of sky

and storm) and Hepa (mother goddess).

The Hurrians became

dominant in northern Syria. By 1550 B.C.E. Hittite texts report a major

Hurrian-based kingdom, known as the Mitanni, having come into being east of the

Euphrates and having become a major competitor to Hittite and Egyptian

influence in Syria.

The kingdom of Mitanni had formulated when the

Hittite king Mursili conquered the Kingdom of Aleppo

in approximately 1530 B.C.E. and left a power vacuum in the northern Syria.

Because Assyrian kings were weak and Mursili of the

Hittite was assassinated by Hantili who took the

throne after he returned to his kingdom, Mitanni had an opportunity to fill the

vacuum which these successes had created. The Hurrian kingdom was powerful

enough to hold in check the Assyrians in the east, the Hittites and Egyptians

in the west.

Starting from the king Parattarna,

Mitanni expanded the kingdom west to Aleppo, north-east to Carchemish and

south-west to Nuzi.. The political structure of the

Mitanni was probably a Mitanni innovation superimposed on the old Hurrian

social order and seems to have been imposed on Mitanni’s vassal states as well,

turning them into provinces whose governance and military administration were

directed from the center.

There are two assumptions about Mitanni’s success

and its character as a semi-peripheral marcher state. First, they seem to have

imposed themselves peacefully and to have adopted the culture of the land into

which they entered. Their main contribution seems to have been the introduction

of a new form of political and social organization that was more effective at mobilizing

and employing resources for war. The pattern was a familiar one among

Indo-Aryans, namely strong king drawn from a “great family” tied by blood to

his vassals, who acted as a council of advisors. The Mitanni system was similar

to the Hittite whose origins are also obscure and who superimposed a new caste

on the then extant Hattian society.

Second, the Mitanni were the first to use the

military technology of horse with the spoked-wheel chariot as a primary combat

vehicle. The spoked-wheel war chariot made its first appearance among the

Mitanni sometime soon after their arrival in the Hurrian land circa 1600 B.C.E.

The validity of this claim can be deduced from the Hittite texts of this time

that recount the story of Kikkui of the Land of the

Mitanni, who was hired by the Hittite king to instruct his army in the breeding

and use of the horses.

References:

Bromiley,

Geoffrey W. 1995. International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J. Grand

Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Bryce, Trevor. 1998. The

Kingdom of the Hittites. New York: Oxford University Press.

Garbriel, Richard A. 2007. The Ancient World. Westport,

Connecticut: Greenwood Press

Novak, Mirko. 2007 “Mitani Empire and the Qeustion of

Absolute Chronology: Some Archaelogical Considerations” in M. Bietak - E. Czerny

(eds.), The Synchronisation of Civilisations

in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. III. Proceedings of

the SCIEM 2000 – 2 ndEuro Conference (Wien 2007),

Pp. 389–401

Roux,

Georges. 1992. Ancient Iraq. Third Edition (First publish in 1966). New

York:

Penguin

Books

Sagona, Antonio G. and Paul Zimansky. 2009. Ancient Turkey. New York: Routledge.

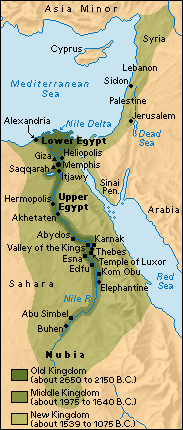

Egypt:2850 BCE to

1500 BCE

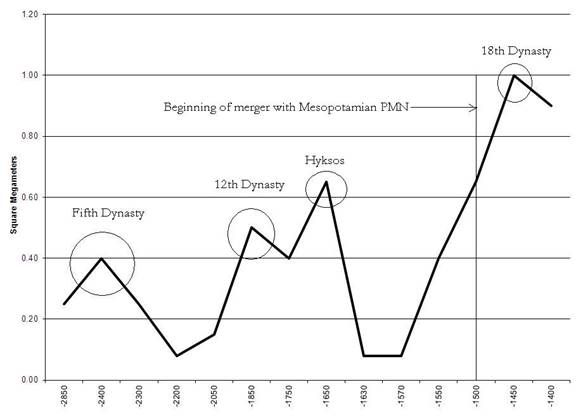

Largest states and empires in the Egyptian PMN, 2850 BCE-1500 BCE

The upsweep

shown in the figure above started with the 2nd Egyptian dynasty so

in order to understand its causes we need to consider what was going on in the

2nd through 5th dynasties.

The 2nd

dynasty capital was the city of Memphis. It is poorly known from archaeological

and documentary evidence. But Kathryn Bard (2000:85 says “There is much less evidence for the kings of the 2nd Dynasty

than those of the 1st Dynasty until the last two reigns (Peribsen

and Khasekhemwy). Given what is known about the early

Old Kingdom in the 3rd Dynasty, the 2nd Dynasty must have been a time when the

economic and political foundations were put in place for the strongly

centralized state, which developed with truly vast resources. Such a major

transition, however, cannot be demonstrated from the archaeological evidence

for the 2nd Dynasty.”

The origins of

the Old Kingdom 5th Dynasty--as those of the 1st--are shrouded in legend.

Manetho wrote that the Dynasty

V kings ruled from Elephantine, but archaeologists have found

evidence clearly showing that their palaces were still located at Ineb-hedj ("White Walls") in the city of Memphis. There

is evidence of significant changes in religious structure, such as the writing

of the "Pyramid Texts" (funerary prayers

inscribed on royal tombs),

the rise of Ra as the prominent deity (and his cult's prominence), followed at

the end of the dynasty by the succession of the cult of Osiris, and the

"solar cult" (which would centuries later be solidified under the Sun

God Pharoah, Akhenaten) and its obelisks and other

"solar temples." Beaujard (2112:176) interprets the rise of the cult of

Osiris during the 5th dynasty

as an indication of the internal consolidation of power of the Egyptian

hegemon.

Regarding

original Egyptian state formation Van de Mieroop

says:

This still did not explain why territorial

unification occurred. Theories that the concept was inspired from abroad -

Babylonia and Nubia have both been suggested - are mostly rejected now (cf. Midant - Reynes 2003 : 275 -307),

and scholars prefer to focus on indigenous forces. Many think that centers of

production and exchange developed along the Nile Valley and that elites in them

sought increased territorial powers to gain access to trade items and

agricultural areas. When the zones of influence of neighboring centers started

to intersect, conflict arose, which was settled through either war or alliances

(Bard 1994: 116 - 18). But Egypt was rich in resources and had a small

population in late prehistoric times, so why would people have competed over

them? Non - materialist motives may have driven expansion. People who settled

down became territorial and like players in a Monopoly game tried to expand

their holdings. Thousands of such games took place along the Nile and

increasingly fewer players became more powerful until one triumphed (Kemp 2006

: 73 - 8). Conquest was not necessarily the main force of unification; peaceful

arrangements (marriages, etc.) may have been more important (Midant - Reynes 2003 : 377 - 80).

In recent years the view that the valley was the primary locus of change has

been under attack. Remains in the desert, which was more fertile in the fourth

millennium bc than it is now, show that pastoralists

flourished more than the early farmers of the valley. Part of the evidence on

them derives from rock art in the eastern desert (T. Wilkinson 2003 : 162 -

95), other evidence comes from the western desert oases (Riemer

2008 ). For centuries the people who moved around outside the valley were more

active and wealthier than those who farmed. They developed a greater social

hierarchy and an elite that controlled resources and they ultimately unified

the whole of Egypt - valley, Delta, and desert regions - into a vast territory

with a bureaucracy to administer it (Wengrow 2006).

Archaeological finds at Byblos attest to diplomatic expeditions sent to that Phoenician city.

For this dynasty, we rule out the rise of a semiperipheral marcher state and

inter-core conflicts, and for now assume this dynastic shift was the result of

an internal succession.

M.Barta (2013:261) speaks about an increase in

of the central administration and bureaucratic elite during the 5th

and 6th dynasties. In spite of a decrease in the size of the

pyramids in the late Old Kingdom, there was an increase in standardization of

measurements and royal symbolism in royal mortuary architecture during the 5th

dynasty. The increased occurrence of extra space for storage rooms in

connection with the offering cult of the king points to more emphasis on a

royal and centralized worship. (Barta 2013: 265-266)

During the fifth dynasty there was an increased occurrence of “family-tombs”

with the non-royal funerary architecture. This is a result of the fact that

many offices at various levels became hereditary (Barta

2013: 269). State administration, however, came into the hands of more

non-royal officials, in contrast with the royal-related vizers

during the fourth dynasty.

References

Bard, Kathryn A.

2000 "Chapter 4 — The Emergence of the Egyptian State". In Ian Shaw. The Oxford

History of Ancient Egypt(paperback)

(1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barta, M. 2013 “Egyptian Kingship during the

Old Kingdom: Experiencing power generating

authority” Pp. 257-284 in Jane A. Hill, Philip

Jones, and Antonio J. Morales (eds.) Cosmos, Politics,

and the Ideology of Kingship in Ancient

Egypt and Mesopotamia,

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Beaujard, Philippe 2012 Les mondes de l’océan Indien Tome

II: L’océan Indien, au coeur des

globalisations

de l’ancien Monde du 7e au 15e siècle. Paris: Armand

Colin

Dee, Michael, David Wengrow

, Andrew Shortland , Alice Stevenson , Fiona Brock ,

Linus Girdland

Flink and Christopher Bronk

Ramsey 2013 “An absolute chronology for early Egypt using

radiocarbon

dating and Bayesian statistical modelling”

Proceedings of the Royal Society A 469:

20130395.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2013.0395

Flammini, Roxana 2008 “ANCIENT CORE-PERIPHERY INTERACTIONS:

LOWER

NUBIA DURING MIDDLE KINGDOM EGYPT (CA. 2050-1640

B.C.)”

jOURNAL OF wORLD-sYSTEMS rESEARCH vOL 14, nUMBER 1.

http://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/jwsr/article/view/348

Garcia, Juan Carlos Moreno 2007 “The state and the organization of

the rural landscape in the

3rd Mill BC

pharaonic Egypt, in Aridity, Change and conflict in Africa”

Hassan,

Fekri A.1988 “The predynastic

of Egypt” Journal of World Prehistory Vol. 2, Number 2.: 135-

185

_____________

1997 “Holocene paleoclimates of Africa” African Archaeological Review 14,4:

213-

230 http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1022255800388

Hill, Jane A.,

Philip Jones, and, Antonio J. Morales (eds.). 2013. Experiencing Power,

Generating

Authority: Cosmos, Politics, and the Ideology

of Kingship in Ancient Egypt and

Mesopotamia. Philadelphia: University

of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and

Anthropology.Romer, John 2013 A History of Ancient Egypt.

Volume 1. London: Penguin

Books.

Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt.

Oxford University Press.

Smith, W.

Stephenson 1962 The Old Kingdom in Egypt

and the beginning of the First Intermediate Period.

London: Cambridge University Press

Smith, S.T., 1995 Askut in Nubia, the

Economics and Ideology of Egyptian Imperialism in the Second Millennium B.C.

Trigger, Bruce 1976 Kerma, the rise of

an African civilization; International Journal of African Historical

Studies Vol.9 No. 1 p. 1-21

“The collapse of Egypt’s Old Kingdom was not caused

by climatic change” http://seshatdatabank.info/egypt-old-kingdom/

Turchin, Peter 2014 “The

Circumscription Model of the Egyptian State” Social Evolution Forum November 19

https://evolution-institute.org/blog/the-circumscription-model-of-the-egyptian-state/?source=sef

Van De Mieroop, Marc 2011 A History of Ancient Egypt. Malden, MA:

Wiley-Blackwell

Warburton,

David 2001. Egypt and the Near East:

Politics in the Bronze Age. Recherches et Publications, Neuchâtel, Paris.

_______________ 2003 Macroeconomics

from the Beginning, The General Theory, Ancient Markets, and the Rate of Interest

Wengrow, David

2006 The Archaeology of Early

Egypt: Social Transformations in

North-East Africa,

10,000 to 2650 BC.

Cambridge University Press, New York

Wilkinson. Toby

A. H 1996 State Formation in Egypt: chronology and society Oxford: Tempus

Repartum

The territorial

upsweep that peaked during the 12th dynasty in 1850 BCE began during

the 6th dynasty during the First Intermediate period. And the peak was followed by the beginning of

a decline that began during the 12th dynasty (see Egypt data).

The 12th Dynasty—according to Manetho—emerges not from a nomadic or semiperipheral rise

within the region, but from an internal succession of viziers over established

pharaohs. The scope of their power

eventually came to encompass semiperipheral peoples along the Upper Nile (Shaw

2000.)

The 12th Dynasty—according to Manetho—emerges not from a nomadic or semiperipheral rise

within the region, but from an internal succession of viziers over established

pharaohs. The scope of their power

eventually came to encompass semiperipheral peoples along the Upper Nile (Shaw

2000.)

References

Arnold, Dorothea 1991 “Amenemhat I and the Early Twelfth

Dynasty at Thebes” Metropolitan Museum

Journal, 26 :5-48 Chicago: University of Chicago Press http://www.jstor.org/stable/1512902 .\

Bourriau, J. 1997 Relations between Egypt and Kerma

during the Middle and New Kingdom

Grajetzki, Wolfram 2006 The Middle

Kingdom of ancient Egypt, London: Duckworth

Shaw, Ian, ed. 2000. The

Oxford History of Ancient Egypt.

Oxford University Press

Van De Mieroop, Marc 2011 A History of Ancient Egypt. Malden, MA:

Wiley-Blackwell

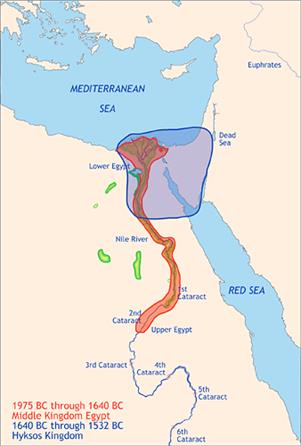

Hyksos

Archaeologists such as McGovern (2000)

and Bietak (1996) regret that they have little to

work with in order to reconstruct an unbiased account of the Hyksos’ rule in

Egypt. Given that the Hyksos were not

indigenous to the region, and were never fully accepted by the native

Egyptians, their brief rule ends with the destruction of the bulk of their

contributions to the region (primarily infrastructure, pottery, and writing),

which, if not destroyed, would allow contemporary Egyptologists to better piece

together the actual events of that time.

Archaeologists such as McGovern (2000)

and Bietak (1996) regret that they have little to

work with in order to reconstruct an unbiased account of the Hyksos’ rule in

Egypt. Given that the Hyksos were not

indigenous to the region, and were never fully accepted by the native

Egyptians, their brief rule ends with the destruction of the bulk of their

contributions to the region (primarily infrastructure, pottery, and writing),

which, if not destroyed, would allow contemporary Egyptologists to better piece

together the actual events of that time.

As such, we are left with the

retrospective accounts of Manetho, whose work is

produced during the 3rd-century BCE, over a millennium after the

expulsion of the Hyksos from the Nile region.

This view—which paints the Hyksos as ubiquitously militant conquerors

who entered the Nile valley and easily crushed the fragmented Egyptian empires

from as early as the 13th Dynasty to the last Egyptian dynasty to be

subjugated by Hyksos rulers: the 17th—has

until recently been the primary source of the Hyksos’ chronology for most

modern historians (Redford 1992, 1997; Redmount

1995).

This epoch—ranging from the 18th

century BCE to the rise of Tao I around 1560 BCE, and typically classified as

the 2nd Intermediate Period—is described in Manetho’s

writings as militarily driven, though not necessarily strewn with warfare. Though sparsely chronicled, the Hyksos are

reputed to have participated in uprisings against the established Egyptian

cities, burning them down with little resistance from the local elites (Bietak 1975: 102).

It would not be until after these initial conflicts that the Hyksos

would be in a position to exact tribute from the indigenous dynasties in both

Upper and Lower Egypt.

Beaujard (2012: 183) states that Egypt maintained trade/diplomatic relations

with Kush to the south, even during the

momentous incursions from Canaan by the Hyksos.

A new school of Egyptologists has

recently gained momentum on the nature of the Hyksos as they enter Egypt from

the northeast. Booth (2005) states that

they did not enter by primarily military means, but as merchants and immigrant

laborers. Due to internal logistical

problems—brought on by famine and plague—the 13th Dynasty was powerless to stop

or effectively regulate the influx of these Asiatic (Canaanite)

immigrants. She suspects that the

extensive mining and architectural aspirations of Amanemhat

III may have even encouraged the advent of these laborers.

Bourriau’s

(1997) account of the transition to Hyksos rule is similar to Booth’s. Her excavation of Memphis does not point to a

military campaign or a forced entry into Egypt by the Hyksos, but rather

debunks Manetho’s depictions of the Hyksos as roving

bands of marauders to be nationalistically motivated, as has been the norm for

most historians until our own times. For

Bourriau, there is no evidence that points to the

sacking of Memphis or any other major urban center by the hands of the Hyksos.

These reconstructed histories,

relying on archaeology rather than classical and ancient historians’

allegations, paint a drastically different picture of the Hyksos as certainly

peripheral or semiperipheral, but not necessarily as an exemplary case of a

marcher state. Having never found any

chariots at Avaris, the capital of the Hyksos, these

contemporary archaeologists assert there to be no clear evidence of the use of

the chariot by the Hyksos as a significant contribution to their rise to

prevalence in Egypt. In short, their

findings do not point to a war of incursion by Canaanite foreigners. They do, however, note some of the Hyksos’

contributions to Egyptian civilization:

bureaucracy. Insofar as the formalization

of an already existing bureaucracy can be taken as an indicator of an upward

sweep, or an intensification of previous modes of government, we can conclude

with some certainty that the Hyksos were far from a peripheral people by the

time they entered Egypt, though there is similarly no conclusive data that

would support the notion that they were an established core power in Canaan and

the Levant.

References:

Beaujard, Philippe 2012 Les mondes de l’océan Indien Tome

II: L’océan Indien, au coeur des globalisations de l’ancien Monde

du 7e au 15e siècle. Paris: Armand Colin

Bietak, Manfred 1975 Tell el-Dab’a

II. Vienna: Osterreichishcen Akademie der Wissenschaften

_____________ 1981 Avaris

and Piramesse: archaeological exploration in the

Eastern Nile delta. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

______________ 1996 Avaris, the Capital of

the Hyksos. Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab’a,

Booth, Charlotte 2005 The

Hyksos Period in Egypt. p.10. Shire Egyptology,

Bourriau, Janine. 1997 The

Hyksos: New Historical and

Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer Oren, University of Pennsylvania

Pp. 159-182.

McGovern, Patrick E.2000 The Foreign

Relations of the “Hyksos”: A neutron

activation study of Middle Bronze Age pottery from the Eastern

Mediterranean. Oxford: Archaeopress

Redford, Donald B. 1992 Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press

________________, 1997 “The Hyksos in

history and tradition” Orientalia,

39:, 1-52.

Redmount, Carol A. 1995 “Ethnicity, Pottery, and

the Hyksos at Tell El-Maskhuta in the Egyptian

Delta”, The Biblical Archaeologist,

58:182 – 190 American Schools of Oriental Research.

Van De Mieroop, Marc 2011 A History of Ancient Egypt. Malden, MA:

Wiley-Blackwell

The Central PMN: 1500 BCE to 1991AD

The accounts of

Reeves (2001: 31 - 32), Aldred (1988),

Wilkinson (1999) and Redford (1984) ubiquitously point to Akhenaten's 18th

dynasty as a core polity when they drove the Hyksos out of Egypt. They

not only are an established power sharing continuity with the pre-Amorite

rulers of Egypt, but their levels of bureaucracy and sophistication allow these

indigenous rulers to resurrect the power structure of the Middle Kingdom and

bring the Nile region back into prominence after the 2nd Intermediate Period.

References:

Aldred, Cyril 1988 Akhenaten: King of Egypt London: Thames & Hudson

Redford, Donald B. 1984 Akhenaten: The Heretic King

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Reeves, Nicholas 2001 Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet London: Thames & Hudson Wilkinson,

Toby A. H. 1999 Early Dynastic Egypt London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis

The Neo-Assyrian Empire at its peak size in 670 BCE

Assyria originally was one of a

number of Akkadian city states in Mesopotamia. In the late 24th

century BC, Assyrian kings were regional leaders only, and subject to Sargon of

Akkad who united all the Akkadian, Semites, and Sumerian speaking peoples of

Mesopotamia under the Akkadian Empire which lasted from 2,334 BC to 2,154 BC.

Assyria gradually expanded its control over a vast area from western Iran to

the Mediterranean and from Anatolia to Egypt, dominating political and economic

life. The development of the empire was accomplished by a series of powerful

rulers who led their army on campaigns almost every year. Progress was neither

smooth nor linear. Two phases can be distinguished: the first in the ninth

century BC and a second phase starting in the mid-eighth century BC (Van De Mieroop 2004:216). In the period of empire building, it is

referred to as the Neo-Assyrian period. The Neo-Assyrian Empire began in 934 BC

and ended in 609 BC.

The rise of Neo-Assyrian Empire was

explained by many factors. First, towards the end of the tenth century BC,

Assyria began to escape its long dark ages. The lack of unity among enemies had

saved it from rapid destruction. Babylonia was partly occupied and plundered by

the Aramaeans; Elam had disappeared from the political stage; Egypt, ruled by

Libyan princes, was almost powerless; the Phrygians in Anatolia, the Medes and

Persians in Iran were still remote and harmless competitors; and Urartu was not

yet fully grown. These situations gave Assyria the best opportunities to expand

(Roux 1992:300).

Assyria had a very strong military.

All men could be called up for military service and all state officers were

designated as military ones. The king was at the top of the structure and his

primary role was to conduct war for the benefit of the state. Thus, there was

an ideology that the king must lead his army into battle annually (Van De Mieroop 2004:217).

Second, Assyria was a multi-ethnic

state composed of many peoples and tribes of different origins. Historical

documents mention numerous Assyrian citizens identified or identifiable as

Egyptians, Israelites, Arabs, Anatolians and Iranians on the basis of their

names or the ethnic labels attached to them (Parpola

2004: 5-7). Despite comprising of many ethnicities, Aramaic was also made an

official language of the empire, alongside the Akkadian language (Frye 1992).

The reasons for the spread of the Aramic language

were not only the expansion of the Aramaeans themselves into the Fertile

Crescent since 2,000 B.C., but also the policies of deportation of populations

by the Assyrian state under Sargon II (722 – 705 BC) and Tiglath-Pileser

III (745-727 BC). Large numbers of peoples, including Aramaens,

were deported and settled all over the Fertile Crescent (Frye 1992). The mass

deportations served many purposes. It provided labor and people to inhabit its

new cities, reduced opposition in peripheral territories as rebellious

populations were resettle in foreign environments where they needed imperial

protection against local hostility. They would not escape as they were

unfamiliar with the country (Van De Mieroop

2004:219). Also, a

multiethnic population base in each region would have curbed nationalist

sentiment, making the running of the Empire smoother.

The first peak is dominated by the

two long and successful reigns of Ashurasirpal II

(883-859 BC) and Shalmaneser III (859-824 BC) (Liverani 2004:213). Soon after Assyria initiated its first

phase of expansion, Ashurasirpal II moved the capital

to Kalhu and rebuilt many palaces and temples inside

an 8-kilometer-long city-wall (Van De Mieroop

2004:220).

Focusing

on military technology, Nefadov 2008 notes that the

Neo-Assyrians adopted iron swords, helmets and armor from Urartu after 735 BC

while their Urartan rivals were subsequently smashed

by the Cimmerians, who had cavalry. The

Neo-Assyrians invented a new three-line battle tactic using shielded warriors

(1st line) covered shooting bowmen (2nd line), and then heavy infantry with iron armor and weaponry

(3rd line).). By 729 BC they had captured lands from Mediterranean Sea to the

Persian Gulf. Later, in 7th century BC they conquered Egypt and Elam as well. Tiglapatalasar

III came to power through an anti-elite revolt that was supported by commoners,

and introduced the principle of meritocratic promotion in the army and widened

the state economy sector. War captives were settled on new land (distant from

their original homes), paid state taxes and could be drafted. All this

stimulated the expansion of a centralized bureaucracy. The Neo-Assyrians lost their military edge to

the Scythians, who had cavalry, and from 623 BC were conquered by them. So semiperipheral marcher Urartu fostered

reactive and adaptive Neo-Assyrian technological and military innovations and

organizational transformations. The Neo-Assyrian upswing was stimulated by

pressure from a semiperipheral

marcher state. This is a variant of Turchin’s “mirror

empires” model discussed above.

References:

Allen, Mitchell. 1997 Contested Peripheries: Philistia

in the Neo-Assyrian World-System.

Unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, Interdepartmental

archaeology program, UCLA.

_____. 2005. “Power is in the Details:

Administrative Technology and the Growth of

Ancient Near Eastern Cores.” Pp. 75-91 in The

Historical Evolution of World-Systems, edited by Christopher Chase-Dunn and

E. N. Anderson. New York and London: Palgrave.

Frye, Richard

Nelson. 1992. “Assyria and Syria: Synonyms.” Journal of Assyrian Academic

Studies, 51(4): 281-285.

Harper,

Prudence O. et al, ed. 1995. Discoveries at Ashur on the Tigris: Assyrian

Origins.

Worcester,

MA: Mercantile Printing

Joannès, Francis. 2004. The Age of Empires:

Mesopotamia in the First Millennium BC.

Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press.

Liverani, Mario. 2004. “Assyria in the Ninth

Century: Continuity or Change in From the Upper Sea

to

the Lower Sea: Studies on the History of Assyria and Babylonia in honour of A.K. Grayson, ?” pp.213-226, edited by G. Frame, Leiden : Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten

Nefedov, S.A. 2008 Faktornyy analiz istoricheskoho processa. Istoriya Vostoka (Factor analysis

of historical

process. The

History of the East) Moscow: Publishing house

Parpola, Simo. 2004. "National and Ethnic

Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian

Identity

in Post-Empire Times." Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 18(2):

5-22.

Radner, Karen 2014 “The Neo-Assyrian Empire” Pp.

101-119 in Michael Gehler and Robert Rollinger (eds.) Imperien und Reiche in der Weltgeschichte, Teil 1. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag

Rollinger, Robert. 2006. "THE TERMS

"ASSYRIA" AND "SYRIA" AGAIN." Journal of

Near

Eastern Studies, 65(4):283-287.

Roux, Georges. 1992. Ancient Iraq.

3rd ed, New York: Penguin Books

Van De Mieroop, Marc. 2004. A History of the Ancient Near East,

ca. 3000-323 BC. Malden, MA:

Blackwell.

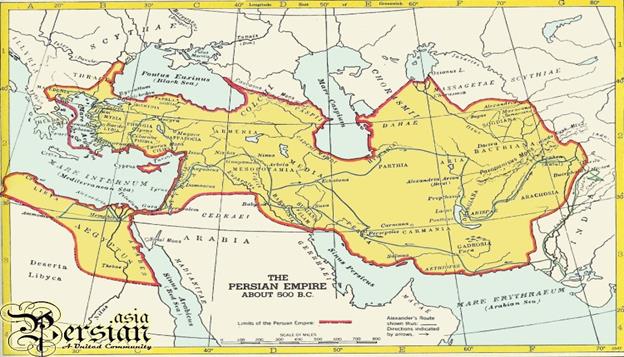

At

its height the Achaemenid Empire, around 550 BCE, stretched from Greece and the Black Sea, over

all of Turkey and as far east as the Indus River (Gershevitch

1985). Originating in the Anshan or Parsuwah region of what is now south central Iran, a

collection of tribes originating from central Asia unified under a central king

in the mid 670 BCE. Caught in between

several stronger empires, the new unified Persians under the rule of the

Achaemenid dynasty continued expanding, conquering and incorporating a number

of Iranian cities and empires until reaching a peak under Darius the Great and

Xerxes. However, following defeats by

Alexander the Great during a long series of Greek wars and internal instability

in the mid-300 BCE, the Achaemenid Dynasty fell and the vast empire was broken

up into several smaller polities or was conquered by invading Greeks (Venetis 2012).

Around

the 8th century BC, a group of agriculturalists and pastoralists (Garthwaite 2005) migrated to the Iranian plateau, from

central Asia (Brosius 2006). The migration of several different groups to

the same region, melding together and eventually becoming known as

Persians. Most likely, the first

Persians migrants from central Asia appeared through gradual the infiltration

of mounted and armed pastoral nomads (Garthwaite

2005). Nevertheless, their migration

route was influenced by the already settled powers west of the plateau. The Assyrian empire was dominant in western

Iran. Because of this, Persians avoided

conflict and moved south between the Zargos Mountains

and the desert until they reached the plains of Fars. To the southwest were the Elemaites

and Medes. These neighboring people were

of material importance both to the evolution of the Persian Empire and urban

life in the ancient east (Irving, 1979).

Cyrus I of Paruwash, Ruler of Anshan

By the first millennium BC, Ashan had become the homeland of Achaemenian

Persians. This area is in what is today

south central Iran. Anshan (an ancient

Persian city), as a result of diplomacy, was part of the Akkadian empire (Gershevitch 1985).

However, there is strong evidence that Anshan was political center of

the Elamites (Gershevitch 1985). Assyrian texts record the land of Parsua first in the 9th century BC when they

invaded the land several times.

Inscriptions of Sargon II (721-705 BC) identify the same area was

invaded previously, but known as Parsuash, and show

it under the reign of Assyrian provincial rule.

This suggests Persians were originally under the control of the Assyrian

empire (Gershevitch 1985). The Assyrian record claims that the Achaemenids were immigrants that did not settle into the

region until Cyrus I consolidated different tribes. However, there is evidence

that settlements date back as far as 675 BCE.

It is obvious that there were several separate tribes and settlements in

the Persian homeland before 675 BCE (Gershevitch

1985).

Cyrus

I, the grandfather of Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II), was credited with the

formation of the first Persian Empire. Before the naming of East Asian

immigrants as Persians they were known as Achaemenid dynasty, of whom Cyrus I

was the ancestor of the founder, Achaemenes (Frye 2010). They thrived

independently as rulers of the Anshan and Parsuwah

region before an invasion by Ashurbanipal, an Assyrian King in 627 BCE. However, it is difficult to determine when

exactly these tribes arrived in this area and when they joined together to form

the Persian Empire. Also, many of these

tribes could have remained separate from the establish Persian empire and

slowly joined the Achaemenians to eventually form the

larger Persian Empire. Their assimilation and integration into other, dominant

societies, eventually allowed for their domination of the entire Zargos mountain region.(Gershevitch

1985).

Vassals of

the Medes and Adoption of Elamite Codes

Before the rise of the Persian

Empire, the Medes ruled much of what is modern-day Iran and controlled all

pastoral tribes (Irving 1979). Around

675 BC, the Medes gained control over the Persians, which would eventually lead

to a joint semi-peripheral marcher state that would dominate the region (Briant 2002). In addition

to being control by the Medes, the newly arrived Persians also adopted the

codes and scripts of Elamite administration to be used in their own

bureaucratic structures. Persian kings

and royalty also adopted Elamite art and culture and the line between Persian

and Elamite became convoluted (Brosius 2006).

Thus,

the Achaemenid Persians, who would soon dominate

modern-day Iran, where definitely the combination of several different groups,

Medes, Elamites, and other central Asian immigrants. Nevertheless, the Persian

migration to the region should not be seen in terms of a peripheral marcher

state as they were soon dominated by the Medes and attempted to integrate

themselves into Elamite culture and tradition.

This domination reversed course as the Achaemenid Persians soon sought

to force assimilation and incorporate previous established cultures (Gershevitch 1985).

Internal

Revolt and the Beginnings of Empire

The rise of the Persian Empire was

the result of an internal revolt led by Cyrus II, against his Median overlords

(Olmstead 1948; Briant 2002). There is no clear birthdate for Cyrus II, or

Cyrus the Great. Estimation ranges from

600 BCE to 575 BCE. Cyrus first united

all Persians who were vassals of the Medes and under his control he sought an

ally against the Medians. Eventually the

Persians were joined by the Babylonians to challenge Median rule. Through the conquest of the Median Empire,

Cyrus II gained large amounts of land and power, which was originally gained

during the Median’s conquest of Assyria.

These large gains were soon seen as a direct challenge to Babylonian

rule and all alliances disappeared. The

destruction of the Medes upset a delicate balance that had existed in the

region and the Persians and the Babylonians soon came into direct conflict

(Olmstead 1948; Briant 2002; Chadwick 2005).

With

the two major power being Persia and Babylon, the Persians soon began the

conquering of other powers in the region, beginning with the Lydians (Briant, 2002). They soon subjugated the Greeks and the Lycians while also conquering much of the region to the

east of the empire. Finally, by 539 BC

the Persians conquered Babylon and gained complete power within the

region. The empire would continue to

rule and challenge all others until 330 BC when it began to decline (Olmstead

1948; Briant 2002; Chadwick, 2005). It was Cyrus II who first fought in Egypt,

and conquered the northern section for the Achaemenid Empire (Gershevitch 1985).

During the expansion period of Cyrus

the Great, the capital Pasargadae was founded.

Politically, the control of the nascent empire was continually

consolidated in this city in the southern central part of Iran. However, it was still under construction when

Cyrus II was killed in battle, sometime around 540 BCE, warring with other

Persian tribes during the Achaemenid expansion.

His tomb was crafted in Pasargadae (Holland 2005).

Darius I

Darius the Great (Darius I)

consolidated the power and expanded the rule of the Achaemenid Empire after the

chaotic period immediately following the death of Cyrus the Great. A politically ruthless man, doubts still

linger if he had inherited the throne legitimately or through murder. Regardless, the young king was born in 550

BCE in a small city in the far eastern limits of the Persian Empire, what is

now Afghanistan. After cementing his

power from inside the Achaemenid Empire, Darius set out to systematically

conquer a series of weaker neighbors through a combination of brilliant

military victories, expert diplomacy, and a relatively humanistic style of

governance. Darius first put down a