Global

Social Change in the Long Run

Thomas D. Hall and Christopher Chase-Dunn

Forthcoming in Global Social Change: A Reader, Johns Hopkins University Press. (9720 words) v. 12-13-04

The comparative world-systems perspective is a

strategy for explaining social change that focuses on whole intersocietal

systems rather than single societies. The main insight is that important interaction

networks (trade, information flows, alliances, and fighting) have woven

polities and cultures together since the beginning of human social evolution.

Explanations of social change need to take intersocietal systems

(world-systems) as the units that evolve. But intersocietal interaction

networks were rather small when transportation was mainly a matter of hiking

with a pack. Globalization, in the sense of the expansion and intensification

of larger interaction networks, has been increasing for millennia, albeit

unevenly and in waves.

World-systems are systems of societies (see

Figure 1). Systemness means that these societies are interacting

with one another in important ways – interactions are two-way, necessary,

structured, regularized and reproductive. Systemic interconnectedness exists

when interactions importantly influence the lives of people within societies,

and are consequential for social continuity or social change. World-systems may

not cover the entire surface of the planet. Some extend over only parts of the

Earth. The word “world” refers to the importantly connected interaction

networks in which people live, whether these are spatially small or

large.

Figure 1: A world-system

is a system of societies

Only the modern world-system

has become a global (Earth-wide) system composed of national societies and

their states. It is a single economy composed of international trade and

capital flows, transnational corporations that produce products on several

continents, as well as all the economic transactions that occur within

countries and at local levels. The whole world-system is more than just

international relations. It is the whole system of human interactions. The

world economy is all the economic interactions of all the people on Earth, not

just international trade and investment.

The

modern world-system is structured politically as an interstate system – a

system of competing and allying states. Political Scientists commonly call this

the international system, and it is the main focus of the field of

International Relations. Some of these states are much more powerful than others,

but the main organizational feature of the world political system is that it is

multicentric. There is no world state. Rather there is a system of

states. This is a fundamentally important feature of the modern system and of

many earlier regional world-systems as well.

When we discuss and compare different kinds of

world-systems it is important to use concepts that are applicable to all of

them. Polity is a more general term that means any organization with a

single authority that claims sovereign control over a territory or a group of

people. Polities include bands, tribes and chiefdoms as well as states. All

world-systems are politically composed of multiple interacting polities. Thus

we can fruitfully compare the modern interstate system with earlier systems in

which there were tribes or chiefdoms, but no states.

In the modern world-system it is important to

distinguish between nations and states. Nations are groups of people who

share a common culture and a common language. Co-nationals identify with one

another as members of a group with a shared history, similar food preferences

and ideas of proper behavior. To a varying extent nations constitute a

community of people who are willing to make sacrifices for one another.

States are formal organizations such as bureaucracies that exercise and

control legitimate violence within a specific territory. Some states in the

modern world-system are nation-states in which a single nation has its own

state. But others are multinational states in which more than one nation is

controlled by the same state. Ethnic groups are sub-nations,

usually minorities within states in which there is a larger national group.

Ethnic groups and nations are sociologically similar in that they are both

groups of people who identify with one another and share a common culture, but

they often differ with regard to their relationship with states. Ethnic groups

are minorities, whereas nations are majorities within a state.

The modern world-system is also importantly

structured as a core/periphery hierarchy in which some regions contain

economically and militarily powerful states while other regions contain

polities that are much less powerful and less developed. The countries that are

called “advanced, ” in the sense that they have high levels of economic

development, skilled labor forces, high levels of income and powerful,

well-financed states, are the core powers of the modern system. The

modern core includes the United States, and the countries of Europe, Japan,

Australia and Canada.

In the contemporary periphery we have

relatively weak states that are not strongly supported by the populations

within them, and have little power relative to other states in the system. The

colonial empires of the European core states have dominated most of the modern

periphery until recently. These colonial empires have undergone decolonization

and the interstate system of formally sovereign states was extended to the

periphery in a series of waves of decolonization that began in the last quarter

of the eighteenth century with the American independence, follow in the early

nineteenth century by the independence of the Spanish American colonies, and in

the twentieth century by the decolonization of Asia and Africa. Peripheral

regions are also economically less developed in the sense that the economy is

composed of subsistence producers, as well as industries that have relatively

low productivity and that employ unskilled labor. Agriculture in the periphery

is typically performed using simple tools, whereas agriculture in the core is

capital-intensive, employing machinery and non-human, non-animal forms of

energy. Some industries in peripheral countries, such as oil extraction or

mining, may be capital-intensive, but these sectors are often controlled by

core capital.

In the past, peripheral countries have been

primarily exporters of agricultural and mineral raw materials. But even when

they have developed some industrial production, this has usually been less

capital intensive and using less skilled labor than production processes in the

core. The contemporary peripheral countries are most of the countries in Asia,

Africa and Latin America – for example Bangla Desh, Senegal and Bolivia.

The core/periphery hierarchy in the modern

world-system is a system of stratification in which socially structured

inequalities are reproduced by the institutional features of the system (see

Figure 2). The periphery is not “catching up” with the core. Rather both core

and peripheral regions are developing, but most core states are staying well

ahead of most peripheral states. There is also a stratum of countries that are

in between the core and the periphery that we call the semiperiphery.

The semiperiphery in the modern system includes countries that have

intermediate levels of economic development or a balanced mix of developed and

less developed regions. The semiperiphery includes large countries that have

political/military power as a result of their large size, and smaller countries

that are relatively more developed than those in the periphery.

Figure 2: Core/Periphery Hierarchy

The

exact boundaries between the core, semiperiphery and periphery are unimportant

because the main point is that there is a continuum of economic and

political/military power that constitutes the core-periphery hierarchy. It does

not matter exactly where we draw lines across this continuum in order to

categorize countries. Indeed we could as well make four or seven categories

instead of three. The categories are only a convenient terminology for pointing

to the fact of international inequality and for indicating that the middle of

this hierarchy may be an important location for processes of social change.

There have been a few cases of upward and downward

mobility in the core/periphery hierarchy, though most countries simply run hard

to stay in the same relative positions that they have long had. A most

spectacular case of upward mobility is the United States. Over the last 300

years the territory that became the U.S. has moved from outside the

Europe-centered system (a separate continent containing several regional

world-systems), to the periphery, to the semiperiphery,

to the core, to the position of hegemonic core state (see below), and now its

hegemony is slowly declining. An example of downward mobility is the United

Kingdom of Great Britain, the hegemon of the nineteenth century and now just

another core society.

The global stratification system is a continuum of

economic and political-military power that is reproduced by the normal operations

of the system. In such a hierarchy there are countries that are difficult to

categorize. For example, most oil-exporting countries have very high levels of

GNP per capita, but their economies do not produce high technology products

that are typical of core countries. They have wealth but not development. The

point here is that the categories (core, periphery and semiperiphery) are just

a convenient set of terms for pointing to different locations on a continuous

and multidimensional hierarchy of power. It is not necessary to have each case

fit neatly into a box. The boxes are only conceptual tools for analyzing the

unequal distribution of power among countries.

When

we use the idea of core/periphery relations for comparing very different kinds

of world-systems we need to broaden the concept a bit and to make an important

distinction (see below). But the most important point is that we should not

assume that all world-systems have core/periphery hierarchies just because

the modern system does. It should be an empirical question in each case as to

whether core/periphery relations exist. Not assuming that world-systems have

core/periphery structures allows us to compare very different kinds of systems

and to study how core/periphery hierarchies themselves emerged and

evolved.

In order to do this it is helpful to distinguish

between core/periphery differentiation and core/periphery hierarchy.

Core/periphery differentiation means that societies with different degrees of

population density, polity size and internal hierarchy are interacting with one

another. As soon as we find village dwellers interacting with nomadic neighbors

we have core/periphery differentiation. Core/periphery hierarchy refers to the

nature of the relationship between societies. This kind of hierarchy exists

when some societies are exploiting or dominating other societies. Examples of

intersocietal domination and exploitation would be the British colonization and

deindustrialization of India, or the conquest and subjugation of Mexico by the

Spaniards. Core/periphery hierarchy is not unique to the modern Europe-centered

world-system of recent centuries. Both the Roman and the Aztec empires

conquered and exploited peripheral peoples as well as adjacent core states.

Distinguishing between core/periphery

differentiation and core/periphery hierarchy allows us to deal with situations

in which larger and more powerful societies are interacting with smaller ones,

but are not exploiting them. It also allows us to examine cases in which smaller,

less dense societies may be exploiting or dominating larger societies. This

latter situation definitely occurred in the long and consequential interaction

between the nomadic horse pastoralists of Central Asia and the agrarian states

and empires of China and Western Asia. The most famous case was that of the

Mongol Empire of Chingis Khan, but confederations of Central Asian steppe

nomads managed to extract tribute from agrarian states long before the rise of

Mongols.

So the modern world-system is now a global economy

with a global political system (the interstate system). It also includes all

the cultural aspects and interaction networks of the human population of the

Earth. Culturally the modern system is composed of: several civilizational

traditions, (e.g. Islam, Christendom, Hinduism, etc.), nationally-defined

cultural entities -- nations (and these are composed of class and functional

subcultures, e.g. lawyers, technocrats, bureaucrats, etc.), and the

cultures of indigenous and minority ethnic groups within states. The modern

system is multicultural in the sense that important political and economic

interaction networks connect people who have rather different languages,

religions and other cultural aspects. Most earlier world-systems have also been

multicultural.

Interaction

networks are regular and repeated

interactions among individuals and groups. Interaction may involve trade,

communication, threats, alliances, migration, marriage, gift giving or

participation in information networks such as radio, television, telephone

conversations, and email. Important interaction networks are those that affect

peoples’ everyday lives, their access to food and necessary raw materials,

their conceptions of who they are, and their security from or vulnerability to

threats and violence. World-systems are fundamentally composed of interaction

networks.

One of the important systemic features of the

modern system is the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers – the so-called

“hegemonic sequence.” A hegemon is a core state that has a significantly

greater amount of economic power than any other state, and that takes on the

political role of system leader. In the seventeenth century the Dutch Republic

performed the role of hegemon in the Europe-centered system, while Great

Britain was the hegemon of the nineteenth century, and the United States has

been the hegemon in the twentieth century. Hegemons provide leadership and

order for the interstate system and the world economy. But the normal operating

processes of the modern system – uneven economic development and competition

among states – make it difficult for hegemons to sustain their dominant

positions, and so they tend to decline. Thus the structure of the core

oscillates back and forth between hegemony and a situation in which several

competing core states have a roughly similar amount of power and are contending

for hegemony – i.e. hegemonic rivalry (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hegemony and Hegemonic Rivalry

So

the modern world-system is composed of states that are linked to one another by

the world economy and other interaction networks. Earlier world-systems were

also composed of polities, but the interaction networks that linked these

polities were not intercontinental in scale until the expansion of Europe in

the fifteenth century. Before that world-systems were smaller regional affairs.

But these had been growing in size with the expansion of trade networks and

long-distance military campaigns for millennia.

Spatial Boundaries of World-Systems

One big difference between the modern world-system

and earlier systems is the spatial scale of different types of interaction

networks. In the modern global system most of the important interaction

networks are themselves global in scale. But in earlier smaller systems there

was a significant difference in spatial scale between networks in which food

and basic raw materials were exchanged and much larger networks of the exchange

of prestige goods or luxuries. Food and basic raw materials we call “bulk

goods” because they have a low value per unit of weight. Indeed it is

uneconomical to carry food very far under premodern conditions of

transportation.

Imagine that the only type of transportation

available is people carrying goods on their backs (or heads). This is a situation

that actually existed everywhere until the domestication of beasts of burden.

Under these conditions a person can carry, say, 30 kilograms of food. Imagine

that this carrier is eating the food as s/he goes. So after a few days walking

all the food will be consumed. This is the economic limit of food

transportation under these conditions of transportation. This does not mean

that food will never be transported farther than this distance, but there would

have to be an important reason for moving it beyond its economic range.

A prestige good (e.g. a very valuable food such as

spices, or jewels or bullion) has a much larger spatial range because a small

amount of such a good may be exchanged for a great deal of food. This is why

prestige goods networks are normally much larger than bulk goods networks. A

network does not usually end as long as there are people with whom one might

trade. Indeed most early trade was what is called down-the-line trade in

which goods are passed from group to group. For any particular group the

effective extent of its of a trade network is that point beyond which nothing

that happens will affect the group of origin.

In order to bound interaction networks we need to

pick a place from which to start – a so-called “place-centric approach.” If we

go looking for actual breaks in interaction networks we will usually not find

them, because almost all groups of people interact with their neighbors. But if

we focus upon a single settlement, for example the precontact indigenous village

of Onancock on the Eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay (near the boundary

between what are now the states of Virginia and Maryland), we can determine the

spatial scale of the interaction network by finding out how far food moved to

and from our focal village. Food came to Onancock from some maximum distance. A

bit beyond that were groups that were trading food to groups that were directly

sending food to Onancock. If we allow two indirect jumps we are probably far

enough from Onancock so that no matter what happens (e.g. a food shortage or

surplus), it would not have affected the supply of food in Onancock. This outer

limit of Onancock’s indigenous bulk goods network probably included villages at

the very southern and northern ends of the Chesapeake Bay.

Onancock’s prestige goods network was much larger

because prestige goods move farther distances. Indeed, copper that was in use

by the indigenous peoples of the Chesapeake may have come from as far away as

Lake Superior. In between the size of bulk goods networks (BGNs) and prestige

goods networks (PGNs) are the interaction networks in which polities make war

and ally with one another. These are called political-military networks (PMNs). In the case of the Chesapeake world-system at the time of the

arrival of the Europeans in the sixteenth century Onancock was part of a

district chiefdom in a system of multi-village chiefdoms. Across the bay on the

Western shore were at least two larger polities, the Powhatan and the Conoy

paramount chiefdoms. These were core chiefdoms that were collecting tribute

from a number of smaller district chiefdoms. Onancock was part of an interchiefdom

system of allying and war-making polities. The boundaries of that network

included some indirect links, just as the trade network boundaries did. Thus

the political-military network (PMN) of which Onancock was the focal place

extended to the Delaware Bay in the north and into what is now the state of

North Carolina to the south.

Information, like a prestige good, is light

relative to its value. Information may travel far along trade routes and beyond

the range of goods. Thus information networks (INs) are usually as large or

even larger than Prestige Goods nets (PGNs).

A general picture of the spatial relationships between

different kinds of interaction networks is presented in Figure 4. The actual

spatial scale of important interaction needs to be determined for each

world-system we study, but Figure 4 shows what is generally the case – that BGNs

(bulk goods nets) are smaller than PMNs (political-military nets), and these

are in turn smaller than PGNs (prestige goods nets) and INs (information nets).

Figure 4 The Spatial

Boundaries of World-Systems

Defined

in the way that we have above, world-systems have grown from small to large

over the past twelve millennia as societies and intersocietal systems have

gotten larger, more complex and more hierarchical. This spatial growth of

systems has involved the expansion of some and the incorporation of some into

others. The processes of incorporation have occurred in several ways as systems

distant from one another have linked their interaction networks. Because

interaction nets are of different sizes, it is the largest ones that come into

contact first. Thus information and prestige goods link distant groups long

before they participate in the same political-military or bulk goods networks.

The processes of expansion and incorporation brought different groups of people

together and made the organization of larger and more hierarchical societies

possible. It is in this sense that globalization has been going on for

thousands of years.

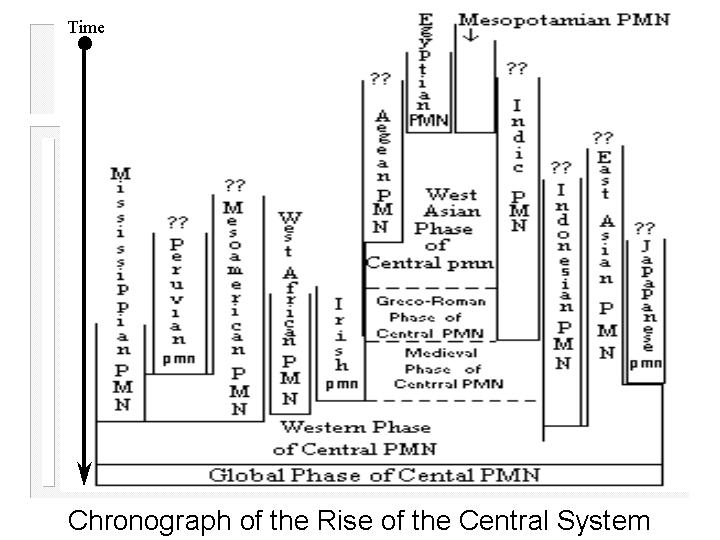

Using the conceptual apparatus for spatially

bounding world-systems outlined above we can construct spatio-temporal

chronographs for how the interaction networks of the human population changed

their spatial scales to eventuate in the single global political economy of

today. Figure 3 uses PMNs as the unit of analysis to show how a

"Central" PMN, composed of the merging of the Mesopotamian and

Egyptian PMNs in about 1500 BCE, eventually incorporated all the other PMNs

into itself.

Figure 5: Chronograph of PMNs [adapted from Wilkinson (1987)]

World-system

Cycles: Rise-and-Fall and Pulsations

Comparative research reveals that all

world-systems exhibit cyclical processes of change. There are two major cyclical

phenomena: the rise and fall of

large polities, and pulsations in

the spatial extent and intensity of trade networks. "Rise and fall" corresponds to changes in the centralization of

political/military power in a set of polities – an “international” system. It

is a question of the relative size of, and distribution of, power across a set

of interacting polities. The term "cycling" has been used to describe

this phenomenon as it operates among chiefdoms (Anderson 1994).

All world-systems in which there are hierarchical

polities experience a cycle in which relatively larger polities grow in power

and size and then decline. This applies to interchiefdom systems as well as

interstate systems, to systems composed of empires, and to the modern rise and fall

of hegemonic core powers (e.g. Britain and the United

States).

Though very egalitarian and small scale systems such as the sedentary foragers

of Northern California (Chase-Dunn and Mann, 1998) do not display a cycle of

rise and fall, they do experience pulsations.

All systems, including even very small and

egalitarian ones, exhibit cyclical expansions and contractions in the spatial

extent and intensity of exchange networks. We call this sequence of trade

expansion and contraction pulsation.

Different kinds of trade (especially bulk goods trade vs. prestige goods trade)

usually have different spatial characteristics. It is also possible that

different sorts of trade exhibit different temporal sequences of expansion and

contraction. It should be an empirical question in each case as to whether or

not changes in the volume of exchange correspond to changes in its spatial

extent. In the modern global system large trade networks cannot get spatially

larger because they are already global in extent.[1]

But they can get denser and more intense relative to smaller networks of

exchange. A good part of what has been called globalization is simply the

intensification of larger interaction networks relative to the intensity of

smaller ones. This kind of integration is often understood to be an upward

trend that has attained its greatest peak in recent decades of so-called global

capitalism. But research on trade and investment shows that there have been two

recent waves of integration, one in the last half of the nineteenth century and

the most recent since World War II (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000).

The simplest hypothesis regarding the temporal

relationships between rise-and-fall and pulsation is that they occur in tandem.

Whether or not this is so, and how it might differ in distinct types of

world-systems, is a set of problems that are amenable to empirical research.

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) have contended that the

causal processes of rise and fall differ depending on the predominant mode of

accumulation. One big difference between the rise and fall of empires and the

rise and fall of modern hegemons is in the degree of centralization achieved

within the core. Tributary systems alternate back and forth between a structure

of multiple and competing core states on the one hand and core-wide (or nearly

core-wide) empires on the other. The modern interstate system experiences the

rise

and fall of hegemons, but these never take over the other core states to form a

core-wide empire. This is the case because modern hegemons are pursuing a

capitalist, rather than a tributary form of accumulation.

Analogously, rise and fall works somewhat

differently in interchiefdom systems because the institutions that facilitate

the extraction of resources from distant groups are less fully developed in

chiefdom systems. David G. Anderson's (1994) study of the rise and fall of

Mississippian chiefdoms in the Savannah River valley provides an excellent and

comprehensive

review of the anthropological and sociological literature about what Anderson

calls "cycling," the processes by which a chiefly polity extended

control over adjacent chiefdoms and erected a two-tiered hierarchy of

administration over the tops of local communities. At a later point these

regionally centralized chiefly polities

disintegrated

back toward a system of smaller and less hierarchical polities.

Chiefs relied more completely on hierarchical

kinship relations, control of ritual hierarchies, and control of prestige goods

imports than do the rulers of true states. These chiefly techniques of power

are all highly dependent on normative integration and ideological consensus.

States developed specialized organizations for extracting resources that

chiefdoms lacked -- standing armies and bureaucracies. And states and empires

in the tributary world-systems were more dependent on the projection of armed

force over great distances than modern hegemonic core states have been. The

development of commodity production and mechanisms of financial control, as

well as further development of bureaucratic techniques of power, have allowed

modern hegemons to extract resources from far-away places with much less

overhead cost.

The development of techniques of power have made

core/periphery relations ever more important for competition among core powers

and have altered the way in which the rise-and-fall process works in other

respects. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997:Chapter 6) argued that population growth in

interaction with the environment, and changes in productive technology and

social structure produce social evolution that is marked by cycles and periodic

jumps. This is because each world-system oscillates around a central tendency

(mean) due both to internal instabilities and environmental fluctuations.

Occasionally, on one of the upswings, people solve systemic problems in a new

way that allows substantial expansion. We want to explain expansions,

evolutionary changes in systemic logic, and collapses. That is the point of

comparing world-systems.

The multiscalar regional method of

bounding world-systems as nested interaction networks outlined above is

complementary with a multiscalar temporal analysis of the kind suggested by

Fernand Braudel’s work. Temporal depth, the longue

duree, needs to be combined with analyses of short-run and middle-run

processes to fully understand social change. The shallow presentism of most

social science and contemporary culture needs to be denounced at every

opportunity.

A strong case for the very longue duree is made by Jared Diamond’s

(1997) study of original zoological and botanical wealth. The geographical

distribution of those species that could be easily and profitably domesticated

explains a huge portion of the variance regarding which world-systems expanded

and incorporated other world-systems thousands of years hence. Diamond also

contends that the diffusion of domesticated plant and animal species occurs

much more quickly in the latitudinal dimension (East/West) than in the

longitudinal dimension (North/South), and so this explains why domesticated

species spread so quickly to Europe and East Asia from West Asia, while the

spread south into Africa was much slower, and the North/South orientation of

the American continents made diffusion much slower than in the Old World Island

of Eurasia.

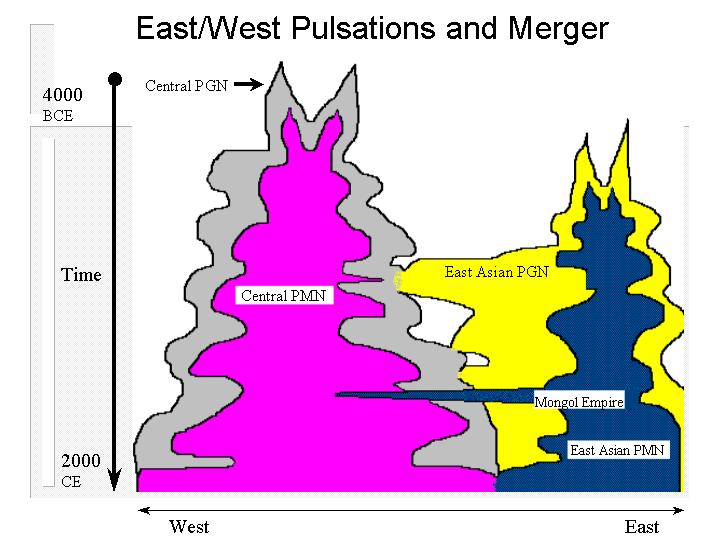

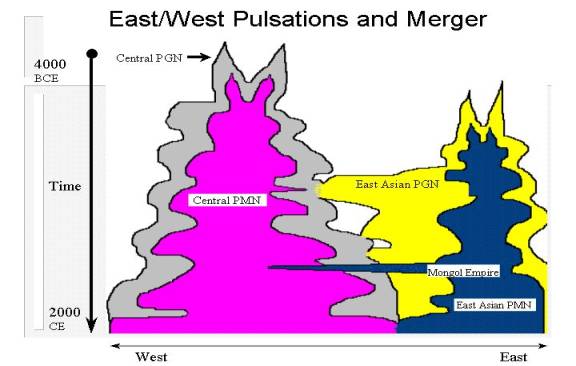

Figure 6 below depicts the coming

together of the East Asian and the West Asian/Mediterranean systems. Both the

PGNs and the PMNs are shown, as are the pulsations and rise and fall sequences.

The PGNs linked intermittently and then joined. The Mongol conquerors linked

the PMNs briefly in the thirteenth century, but the Eastern and Western PMNs

were not permanently linked until the Europeans and Americans established Asian

treaty ports in the nineteenth century.

Figure

6: East/West Pulsations and Merger

Modes of Accumulation

In

order to comprehend the qualitative changes that have occurred with the

processes of social evolution we need to conceptualize different logics of

development and the institutional modes by which socially created resources are

produced and accumulated. All societies produce and distribute the goods that

are necessary for everyday life. But the institutional means by which human

labor is mobilized are very different in different kinds of societies. Small

and egalitarian societies rely primarily on normative regulation organized as

commonly shared understandings about the obligations that members of families

have toward one another. When a hunter returns with his game there are definite

rules and understandings about who should receive shares and how much. All

hunters in foraging societies want to be thought of as generous, but they must

also take care of some people (those for whom they are the most responsible)

before they can give to others.

The normative order defines the roles and the obligations,

and the norms and values are affirmed or modified by the continual symbolic and

non-symbolic action of the people. This socially constructed consciousness

is mainly about kinship, but it is also about the nature of the universe of

which the human group is understood as a part. This kind of social economy is

called a kin-based mode of production and accumulation. People work

because they need food and they have obligations to provide food for others.

Accumulation mainly involves the preservation and storage of food supplies for

the season in which food will become scarce. Status is based on the reputation

that one has as a good hunter, a good gatherer, a good family member, or a

talented speaker. Group decisions are made by consensus, which means that the

people keep talking until they have come to an understanding of what to do. The

leaders have authority that is mainly based on their ability to convince others

that they are right. These features are common (but not universal) among

societies and world-systems in which the kin-based modes of accumulation are

the main logic of development.

As societies become larger and more hierarchical,

kinship itself becomes hierarchically defined. Clans and lineages become ranked

so that members of some families are defined as senior or superior to members

of other families. Classical cases of ranked societies were those of the

Pacific Northwest, in which the totem pole represents a hierarchy of clans.

This tendency toward hierarchical kinship resulted in the eventual emergence of

class societies (complex chiefdoms) in which a noble class owned and controlled

key resources and a class of commoners was separated from the control of

important resources and had to rely on the nobles for access to these. Such a

society existed in Hawaii before the arrival of the Europeans.

The tributary modes of accumulation emerged

when institutional coercion became a central form of regulation for inducing

people to work and for the accumulation of social resources. Hierarchical kinship

functions in this way when commoners must provide labor or products to chiefs

in exchange for access to resources that chiefs control by means of both

normative and coercive power.

Normative power does not work well by itself as a basis

for the appropriation of labor or goods by one group from another. Those who

are exploited have a great motive to redefine the situation. The nobles may

have elaborated a vision of the universe in which they were understood to

control natural forces or to mediate interactions with the deities and so

commoners were supposed to be obligated to support these sacred duties by

turning over their produce to the nobles or contributing labor to sacred

projects. But the commoners will have an incentive to disbelieve unless they

have only worse alternatives. Thus the institutions of coercive power are

invented to sustain the extraction of surplus labor and goods from direct

producers. The hierarchical religions and kinship systems of complex chiefdoms

became supplemented in early states by specialized organizations of regional

control -- groups of armed men under the command of the king and bureaucratic

systems of taxation and tribute backed up by the law and by institutionalized

force. The tributary modes of accumulation develop techniques of power that

allowed resources to be extracted over great distances and from large

populations. These are the institutional bases of the states and the

empires.

The third mode of accumulation is based on

markets. Markets can be defined as any situation in which goods are bought and

sold, but we will use the term to denote what are called price-setting

markets in which the competitive trading by large numbers of buyers and

sellers is an important determinant of the price. This is a situation in which

supply and demand operate on the price because buyers and sellers are bidding

against one another. In practice there are very few instances in history or in

modern reality of purely price-setting markets, because political and normative

considerations quite often influence prices. But the price mechanism and

resulting market pressures have become more important. These institutions were

completely absent before the invention of commodities and money.

A commodity is a good that is produced for

sale in a price-setting market in order to make a profit. A pencil is an

example of a modern commodity. It is a fairly standardized product in which the

conditions of production, the cost of raw materials, labor, energy and

pencil-making machines are important forces acting upon the price of the

pencil. Pencils are also produced for a rather competitive market, and so the

socially necessary costs given the current level of technology, plus a certain

amount of profit, adds up to the cost.

The idea of the commodity is an important element

of the definition of the capitalist mode of accumulation. Capitalism is

the concentrated accumulation of profits by the owners of major means of the

production of commodities in a context in which labor and the other main

elements of production are commodified. Commodification means that things are

treated as if they are commodities, even though they may have characteristics

that make this somewhat difficult. So land can be commodified – treated as if

it is a commodity – even though it is a limited good that has not originally

been produced for profitable sale. There is only so much land on earth. We can

divide it up into sections with straight boundaries and price it based on

supply and demand. But it will never be a perfect commodity. This is also the case with human labor time.

The commodification of land is an historical

process that began when “real property” was first legally defined and sold. The

conceptualization of places as abstract, measurable, substitutable and salable

space is an institutional redefinition that took thousands of years to develop

and to spread to all regions of the Earth.

The

capitalist modes of production also required the redefinition of wealth as

money. The first storable and tradable valuables were probably prestige goods.

These were used by local elites in trade with adjacent peoples, and eventually

as symbols of superior status. Trade among simple societies is primarily

organized as gift giving among elites in which allegiances are created and

sustained. Originally prestige goods were used only in specific circumstances

by certain elites. This “proto-money” was eventually redefined and

institutionalized as the so-called “universal equivalent” that serves as a

general measure of value for all sorts of goods and that can be used by almost

anyone to buy almost anything. The institution of money has a long and

complicated history, but suffice it to say here that it has been a prerequisite

for the emergence of price-setting markets and capitalism as increasingly

important forms of social regulation. Once markets and capital become the

predominant form of accumulation we can speak of capitalist systems.

Patterns and Causes of Social Evolution

It

is important to understand the similarities, but also the important differences

between biological and social evolution. These are discussed in Chase-Dunn and

Lerro 2005: Chapter 1). This section describes a general causal model that

explains the emergence of larger hierarchies and the development of productive

technologies. It also points to a pattern that is noticeable only when we study

world-systems rather than individual societies. The pattern is called semiperipheral

development. This means that those innovations that transform the logic of

development and allow world-systems to get larger and more hierarchical come

mainly from semiperipheral societies. Some semiperipheral societies are

unusually fertile locations for the invention and implementation of new

institutional structures. And semiperipheral societies are not constrained to

the same degree as older core societies from having invested huge resources in

doing things in the old way. So they are freer to implement new institutions.

There are several different important kinds of

semiperipheries, and these not only transform systems but they also often take

over and become new core societies. We have already mentioned semiperipheral

marcher chiefdoms. The societies that conquered and unified a number of smaller

chiefdoms into larger paramount chiefdoms were usually from semiperipheral

locations. Peripheral peoples did not usually have the institutional and

material resources that would allow them to make important inventions and to

implement these or to take over older core regions. It was in the semiperiphery

that core and peripheral social characteristics could be recombined in new

ways. Sometimes this meant that new techniques of power or political legitimacy

were invented and implemented in semiperipheral societies.

Much better known than semiperipheral marcher

chiefdoms is the phenomenon of semiperipheral marcher states. The largest

empires have been assembled by conquerors who come from semiperipheral

societies. The following semiperipheral marchers are well known: the Achaemenid

Persians, the Macedonians led by Alexander The Great, the Romans, the Ottomans,

the Manchus and the Aztecs.

But some semiperipheries transform institutions,

but do not take over. The semiperipheral capitalist city-states operated on the

edges of the tributary empires where they bought and sold goods in widely

separate locations, encouraging people to produce a surplus for trade. The

Phoenician cities (e.g. Tyre, Carthage, etc.), as well as Malacca, Venice and

Genoa, spread commodification by producing manufactured goods and trading them

across great regions. In this way the semiperipheral capitalist city-states

were agents of the development of markets and the expansion of trade networks,

and so they helped to transform the world of the tributary empires without

themselves becoming new core powers.

In the modern world-system we have already

mentioned the process of the rise and fall of hegemonic core states. All of the

cases we mentioned – the Dutch, the British and the U.S. – were countries that

had formerly been in semiperipheral positions relative to the regional

core/periphery hierarchies within which they existed. And indeed the rise of

Europe within the larger Afroeurasian world-system was also a case of

semiperipheral development, one in which a formerly peripheral and then

semiperipheral region rose to become the new core of what had been a huge

multi-core world-system.

The idea of semiperipheral development does not

claim that all semiperipheral societies perform transformational roles, nor

does it contend that every important innovation came from the semiperiphery.

The point is rather that semiperipheries have been unusually prolific sites for

the invention of those institutions that have expanded and transformed many

small systems into the particular kind of global system that we have today.

This observation would not be possible without the conceptual apparatus of the

comparative world-systems perspective.

But what have been the proximate causes that led

semiperipheral societies to invent new institutional solutions to problems?

Some of the problems that needed to be solved were new unintended consequences

of earlier inventions, but others were very old problems that kept emerging

again and again as systems expanded – e.g. population pressure and ecological

degradation. It is these basic problems that make it possible for us to specify

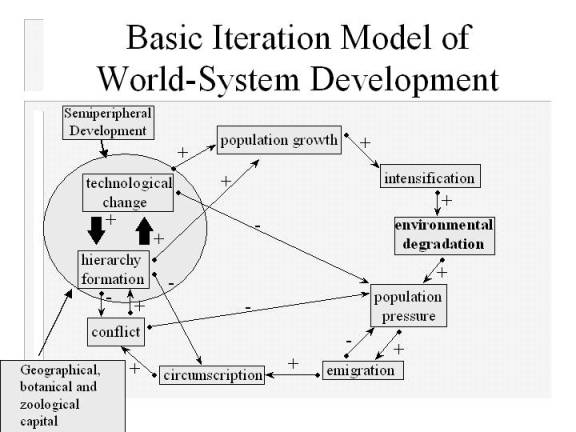

a single underlying causal model of world-systems evolution. Figure 7 shows

what is called the “ iteration model” that links demographic, ecological and

interactional processes with the emergence of new production technologies,

bigger polities and greater degrees of hierarchy.

Figure 7 Basic Iteration Model of World-System Evolution

This

is called an iteration model because it has an important positive feedback mechanism

in which the original causes are themselves consequences of the things that

they cause. Thus the process goes around and around, which is what has caused

the world-systems to expand to the global level. Starting at the top we see

population growth. The idea here is that all human societies contain a

biological impetus to grow that is based on sexuality. This impetus is both

controlled and encouraged by social institutions. Some societies try to

regulate population growth by means of e.g. infanticide, abortion and taboos on

sexual relations during nursing. These institutional means of regulation are

costly, and when greater amounts of food are available these types of

regulation tend to be eased. Other kinds of societies encourage population

growth by means of channeling sexual energy toward reproduction, pro-natalist

ideologies and support for large families. All societies experience periodic

“baby booms” when social circumstances are somewhat more propitious for

reproduction, and thus, over the long run, the population tends to grow despite

institutional mechanisms that try to control it.

Intensification is caused by population growth. This means that

when the number of mouths to feed increases greater efforts are needed to

produce food and other necessities of life and so people exploit the resources

they have been exploiting more intensively. This usually leads, in turn, to ecological

degradation because all human production processes use up the natural

environment. More production leads to greater environmental degradation. This

occurs because more resources are extracted, and because of the polluting

consequences of production and consumption activities. Nomadic hunter-gatherers

depleted the herds of big game and Polynesian horticulturalists deforested many

a Pacific island. Environmental degradation is not a new phenomenon. Only its

global scale is new.

As

Jared Diamond (1998) points out all continents around the world did not start

with the same animal and plant resources. In West Asia both plants (barley and

wheat) and animals (sheep, goats, cows, and oxen) were more easily domesticated

than the plants and animals of Africa and the New World. Since domesticated

plants and animals can more easily diffuse lattitudinally (East and West) than

longitudinally (North and South) these inventions spread more quickly to Europe

and East Asia than they did to Africa. These exogenous factors affect the

timing and speed of hierarchy formation and technological development, as so

climate change and geographical obstacles that affect transportation and

communications. It is widely believed that the emergence of an early large

state on the Nile was greatly facilitated by the ease of controlling

transportation and communications in that linear environment, while the more

complicated geography of Mesopotamia slowed stabilized the system of

city-states and slowed the emergence of a core-wide empire. Patrick Kirch

contends that it was the difficult geography of the Marquesas Island (short

steep valleys separated by high mountains and treacherous coasts) that

prevented the emergence of island-wide paramount chiefdoms, and kept the

Marquesas in the “nasty bottom” of the iteration model.

The consequences of the above processes are that the

economics of production change for the worse. According to Joseph Tainter

(1988), after a certain point increased investment in complexity does not

result in proportionate increasing returns. This occurs in the areas of

agricultural production, information processing and communication, including

education and maintenance of information channels. Sociopolitical control and

specialization, such as military and the police, also develop diminishing

returns. Tainter points out that marginal returns can occur in at least four

instances: benefits constant, costs rising; benefits rising, costs rising

faster; benefits falling, costs constant; benefits falling, costs rising.

When herds are depleted the hunters must go

farther to find game. The combined sequence from population growth to

intensification to environmental degradation leads to population pressure,

the negative economic effects on production activities. The growing effort

needed to produce enough food is a big incentive for people to migrate. And so

humans populated the whole Earth. If the herds in this valley are depleted we

may be able to find a new place where they are more abundant.

Migration eventually leads to circumscription. Circumscription

is the condition that no new desirable locations are available for emigration.

This can be because all the herds in all the adjacent valleys are depleted, or

because all the alternative locations are deserts or high mountains, or because

all adjacent desirable locations are already occupied by people who will

effectively resist immigration.

The condition of social circumscription in which

adjacent locations are already occupied is, under conditions of population

pressure, likely to lead to a rise in the level of intergroup and intragroup

conflict. This is because more people are competing for fewer resources.

Warfare and other kinds of conflict are more prevalent under such conditions.

All systems experience some warfare, but warfare becomes a focus of social

endeavor that often has a life of its own. Boys are trained to be warriors and

societies make decisions based on the presumption that they will be attacked or

will be attacking other groups. Even in situations of seemingly endemic warfare

the amount of conflict varies cyclically. Figure 7 shows an arrow with a

negative sign going from conflict back to population pressure. This is because

high levels of conflict reduce the size of the population as warriors are

killed off and non-combatants die because their food supplies have been

destroyed. Some systems get stuck in a vicious cycle of population pressure and

warfare.

But

situations such as this are also propitious for the emergence of new

institutional structures. It is in these situations that semiperipheral

development is likely to occur. People get tired of endemic conflict. One

solution is the emergence of a new hierarchy or a larger polity that can

regulate access to resources in a way that generates less conflict. The

emergence of a new larger polity usually occurs as a result of successful

conquest of a number of smaller polities by a semiperipheral marcher. The

larger polity creates peace by means of an organized force that is greater than

any force likely to be brought against it. The new polity reconstructs the

institutions of control over territory and resources, often concentrating control

and wealth for a new elite. And larger and more hierarchical polities often

invest in new technologies of production that change the way in which resources

are utilized. They produce more food and other necessaries by using new

technologies or by intensifying the use of old technologies. New technologies

can expand the number of people that can be supported in the territory. This

makes population growth more likely, and so the iteration model is primed to go

around again.

The iteration model has kept expanding the size of

world-systems and developing new technologies and forms of regulation but, at

least so far, it has not permanently solved the original problems of ecological

degradation and population pressure. What has happened is the emergence of

institutions such as states and markets that articulate changes in the

economics of production more directly with changes in political organization

and technology. This allows the institutional structures to readjust without

having to go through short cycles at the messy bottom end of the model.

Figure 8: Temporary Institutional Shortcuts in the

Iteration Model

Another way to say this is that political and market institutions allow

for some adjustments to occur without greatly increasing the level of systemic

conflict. This said, the level of conflict has remained quite high, because the

rate of expansion and technological change has increased. Even though

institutional mechanisms of articulation have emerged, these have not

permanently lowered the amount of systemic conflict because the rates of change

in the other variables have increased.

It is also difficult to understand

why and where innovative social change emerges without a conceptualization of

the world-system as a whole. New organizational forms that transform

institutions and that lead to upward mobility most often emerge from societies

in semiperipheral locations. Thus all

the countries that became hegemonic core states in the modern system had

formerly been semiperipheral (the Dutch, the British, and the United States).

This is a continuation of the long-term pattern of social evolution that

Chase-Dunn Hall (1997) have called “semiperipheral development.” Semiperipheral marcher states and

semiperipheral capitalist city-states had acted as the main agents of empire

formation and commercialization for millennia. This phenomenon arguably also

includes organizational innovations in contemporary semiperipheral countries

(e.g. Mexico, India, South Korea, Brazil) that may transform the now-global

system.

This approach requires that we think structurally.

We must be able to abstract from the particularities of the game of musical

chairs that constitutes uneven development in the system to see the structural

continuities. The core/periphery

hierarchy remains, though some countries have moved up or down. The interstate system remains, though the

internationalization of capital has further constrained the abilities of states

to structure national economies. States

have always been subjected to larger geopolitical and economic forces in the

world-system, and as is still the case, some have been more successful at

exploiting opportunities and protecting themselves from liabilities than

others.

In this perspective many of the phenomena that

have been called “globalization” correspond to recently expanded international

trade, financial flows and foreign investment by transnational corporations and

banks. Much of the globalization discourse assumes that until recently there

were separate national societies and economies, and that these have now been

superseded by an expansion of international integration driven by information

and transportation technologies. Rather

than a wholly unique and new phenomenon, globalization is primarily

international economic integration, and as such it is a feature of the world-system

that has been oscillating as well as increasing for centuries. Recent research

comparing the 19th and 20th centuries has shown that

trade globalization is both a cycle and a trend.

The Great Chartered Companies of the seventeenth

century were already playing an important role in shaping the development of

world regions. Certainly the transnational corporations of the present are much

more important players, but the point is that “foreign investment’ is not an

institution that only became important since 1970 (nor since World War II). Giovanni Arrighi (1994) has shown that

finance capital has been a central component of the commanding heights of the

world-system since the fourteenth century.

The current floods and ebbs of world money are typical of the late phase

of very long “systemic cycles of accumulation.”

Most world-systems scholars contend

that leaving out the core/periphery dimension or treating the periphery as

inert are grave mistakes, not only for reasons of completeness, but also

because the ability of core capitalists and their states to exploit peripheral

resources and labor has been a major factor in deciding the winners of the

competition among core contenders. And the resistance to exploitation and

domination mounted by peripheral peoples has played a powerful role in shaping

the historical development of world orders.

Thus world history cannot be properly understood without attention to

the core/periphery hierarchy.

Phillip McMichael (2000) has studied the

“globalization project” – the abandoning of Keynesian models of national

development and a new (or renewed) emphasis on deregulation and opening

national commodity and financial markets to foreign trade and investment. This approach focuses on the political and

ideological aspects of the recent wave of international integration. The term

many prefer for this turn in global discourse is “neo-liberalism” but it has

also been called “Reaganism/Thatcherism” and the “Washington Consensus.” The

worldwide decline of the political left predated the revolutions of 1989 and the

demise of the Soviet Union, but it was certainly also accelerated by these

events. The structural basis of the

rise of the globalization project is the new level of integration reached by

the global capitalist class. The internationalization of capital has long been

an important part of the trend toward economic globalization. And there have

been many claims to represent the general interests of business before. Indeed

every modern hegemon has made this claim. But the real integration of the

interests of capitalists all over the world has very likely reached a level

greater than at the peak of the nineteenth century wave of globalization.

This is the part of the theory of a global stage

of capitalism that must be taken most seriously, though it can certainly be

overdone. The world-system has now

reached a point at which both the old interstate system based on separate

national capitalist classes, and new institutions representing the global

interests of capital exist, and are powerful simultaneously. In this light each country can be seen to

have an important ruling class fraction that is allied with the transnational

capitalist class. The big question is whether or not this new level of

transnational integration will be strong enough to prevent competition among

states for world hegemony from turning into warfare, as it has always done in

the past, during a period in which a hegemon (now the United States) is

declining.

The insight that capitalist

globalization has occurred in waves, and that these waves of integration are

followed by periods of globalization backlash has important implications for

the future. Capitalist globalization increased both intranational and

international inequalities in the nineteenth century and it has done the same

thing in the late twentieth century (O’Rourke and Williamson 2000). Those

countries and groups that are left out of the “beautiful époque” either

mobilize to challenge the hegemony of the powerful or they retreat into

self-reliance, or both.

Globalization protests emerged in the non-core

with the anti-IMF riots of the 1980s. The several transnational social

movements that participated in the 1999 protest in Seattle brought

globalization protest to the attention of observers in the core, and this

resistance to capitalist globalization has continued and grown despite the

setback that occurred in response to the terrorist attacks on New York and

Washington in 2001.

There is an apparent tension between

those who advocate deglobalization and delinking from the global capitalist

economy and the building of stronger, more cooperative and self-reliant social

relations in the periphery and semiperiphery, on the one hand, and those who

seek to mobilize support for new, or reformed institutions of democratic global

governance. Self-reliance by itself, though an understandable reaction to

exploitation, is not likely to solve the problems of humanity in the long run.

The great challenge of the twenty-first century will be the building of a

democratic and collectively rational global commonwealth. World-systems theory

can be an important contributor to this effort.

References

Amin,

Samir 1997 Capitalism in the Age of

Globalization. London: Zed Press.

Arrighi,

Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth

Century. London: Verso.

Bairoch, Paul 1988 Cities

and Economic Development: From the Dawn

of History to the Present.

Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Barfield, Thomas J. 1989 The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and

China. Cambridge, MA.:

Blackwell

Chandler, Tertius 1987 Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An

Historical Census.

Lewiston,N.Y.:

Edwin Mellon Press

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher 1998 Global Formation.

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield

Chase-Dunn, C and Thomas

D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing

World-Systems Boulder,

CO.:

Westview Press.

Chase-Dunn, C and Kelly

M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and Their

Neighbors: A very Small World-System in Northern California Tucson:

University of Arizona Press.

Chase-Dunn, C., Susan

Manning and Thomas D. Hall 2000 “Rise and fall: East-West

synchrony

and Indic exceptionalism reexamined,” Social

Science History 24,4:727-

754.

Chase-Dunn, C. Daniel Pasciuti and Alexis Alvarez 2005 “The

ancient Mesopotamian and

Egyptian

World-Systems” forthcoming in Barry Gills and William R. Thompson

(eds.) The

Evolution of Macrohistorical Systems. London: Routledge. http://www.irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows14/irows14.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and Alice Willard 1993 "Systems of cities

and world-systems: settlement

size

hierarchies and cycles of political centralization, 2000 BC-1988AD" A

paper

presented

at the International Studies Association meeting, March 24-27, Acapulco.

http://www.irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows5/irows5.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Bruce Lerro 2005 Social Change: World Historical Social

Transformations. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher 2004 “Modeling dynamic nested networks in pre-Columbian

North

America” Presented at the workshop on “analyzing complex macrosystems as

dynamic

networks,” Santa Fe Institute, April 29-30.

Diamond, Jared 1997 Guns,

Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human

Societies. New York: Norton

Hall, Thomas D. 2000 A

World-Systems Reader: new

perspectives on gender, urbanism,

cultures, indigenous peoples, and ecology. Lanham,

MD: Rowman and Littlefield

Kirch, Patrick V. 1984 The

Evolution of Polynesian Chiefdoms. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

_____. 1991.

"Chiefship and Competitive Involution: the Marquesas Islands of Eastern Polynesia." Pp. 119-145 in Chiefdoms: Power, Economy and

Ideology, edited by Timothy Earle.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Mann, Michael 1986 The Sources of Social Power: A History of

Power from the Beginning to A.D.

1760. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Marfoe, Leon 1987

"Cedar forest and silver mountain: social change and the development of

long-distance trade in early Near Eastern societies," Pp. 25-35 in M.

Rowlands et al Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Modelski, George

and William R. Thompson. 1995. Leading Sectors and World Powers: The

Coevolution of Global Politics and Economics. Columbia, SC: University

of South Carolina Press.

Modelski, George

2003 World Cities, -3000 to 2000. Washington, DC: Faros 2000

O’Rourke, Kevin H. and

Jeffrey G. Williamson 2000 Globalization

and History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pasciuti, Daniel 2003 “A measurement error model

for estimating the populations of cities,” https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/estcit/modpop/modcitpop.htm

Shannon,

Thomas R. 1996 An Introduction to the

World-Systems Perspective. Boulder, CO: Westview

Taagepera, Rein 1978a

"Size and duration of empires: systematics of size" Social Science

Research

7:108-27.

______ 1978b "Size

and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600 B.C."

Social Science Research, 7 :180-96.

______1979 "Size and

duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D."

Social Science History 3,3-4:115-38.

_______1997 “Expansion

and contraction patterns of large polities: context for Russia.”

International Studies Quarterly 41,3:475-504.

Tainter, Joseph

A. 1988. The Collapse of Complex

Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Teggart, Frederick J.

1939 Rome and China: A Study of

Correlations in Historical Events Berkeley:

University

of California Press.

Thompson, William

R. 1995. "Comparing World Systems:

Systemic Leadership Succession and the Peloponnesian War Case." Pp. 271-286 in The Historicial Evolution of the International Political Economy,

Volume 1, edited by Christopher Chase-Dunn.

Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar.

Turchin, Peter 2003 Historical

Dynamics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wallerstein,

Immanuel 2000 The Essential Wallerstein.

New York: New Press.

Wilkinson, David 1987

"Central Civilization." Comparative

Civilizations Review 17:31-59.

______ 1992 "Cities,

civilizations and oikumenes:I." Comparative

Civilizations Review 27:51-

87

(Fall).

_______ 1993 “Cities, civilizations and oikumenes:II” Comparative Civilizations Review 28

Wright, Henry

T. 1986 "The Evolution of Civilization." Pp. 323-365 in American Archaeology, Past and Future:

A Celebration of the Society for American Archaeology, 1935-1985,

edited by David J. Meltzer. Washington,

D. C.: Smithsonian Institutional Press.