Modeling

dynamical nested networks in the Prehistoric U.S. Southwest

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute for

Research on World-Systems

College Building South

University of California, Riverside

To be presented at the workshop on ‘analyzing complex macrosystems as dynamic networks” at the Santa Fe Institute, April 29-30, 2004. (9370 words) draft v. 4-27-04

https://irows.ucr.edu/cd/papers/sfi04/c-dsfi04pap.htm

Modeling the causes of

social evolution

The comparative world-systems perspective

Spatial bounding of world-systems:

nested interaction networks (bgn,

pmn,pgn, in)

Core/periphery differentiation and

hierarchy

Semiperipheral Development

Pulsation of networks

Rise and fall of large and powerful

polities

The iteration model

Exogenous factors

affecting the iteration model:

climate change, geographical conditions, botanical and zoological

capital, long-distance diffusion of crops, animals and ideas.

Inter-regional

interactions

The Southwest

and its Neighbors

Southwest, Plains, Great Basin,

California, Mesoamerica

Interegional

Interactions, Endogenous Processes and Exogenous Impacts

This paper discusses issues of dynamical

modeling of the evolution of human interaction networks, briefly outlines the

main ideas used by the comparative world-systems approach, and examines the

development of nested interaction networks in the late prehistoric U.S.

southwest.

Dynamical

modeling of the causes of social evolution should arguably combine the

agent-based approach with macrostructural process models. Ideally multilevel

agents and systems could be represented, with individuals, households,

settlements, and polities as actors within multi-polity systems. This would be

a fair approximation of most world-systems. But as Peter Turchin (2003:5) notes,

hierarchical dynamic models with more than two levels are impractical because

it is very difficult to interpret the results. The best solution for

world-system studies is to model polities as agents and the interpolity system

level variables and processes as constraints on and opportunities for the

action of polities. While this ignores the household as agent that is preferred

in most agent-based approaches to small scale systems like the “artificial

Anasazi” (e.g. Kohler et al 2000; Dean et al 2000), it allows

some of the macroprocesses of world-systems to emerge from the intentional

actions of polities.

Place-centric

interaction networks are arguably the best way to bound human systemic

processes because approaches that attempt to define regions or areas based on

attributes necessarily assume homogenous characteristics, whereas interaction

itself often produces differences rather than similarities (Chase-Dunn and

Jorgenson 2003). The culture area approach that has become institutionalized in

the study of the pre-Columbian Americas is impossible to avoid (as below), but

the point needs to be made that important interactions occur across the

boundaries of the designated regions. Networks are the best way to bound

systems, but since all actors interact with their neighbors, a place-centric

(or object-centric) approach that estimates the fall-off of interactional

significance is also required.

The comparative

world-systems approach has adapted the concepts used to study the modern system

for the purpose of using world-systems as the unit of analysis in the

explanation of human social evolution. Nested networks are used to bound

systemic interaction because different kinds of interaction (exchange of bulk

goods, fighting and allying, long-distance trade and information flows) have

different spatial scales. Core/periphery relations are of great interest but

the existence of core/periphery hierarchy is not presumed. Rather the question

of exploitation and domination needs to be asked at each of the network levels.

Some systems may be based primarily on equal interdependence or equal contests,

while others will display hierarchy and power-dependence relations. It should

not be assumed that earlier systems are similar to the modern global system in

this regard. Rather it should be a question for research on each system.

The comparative

world-systems claim that whole systems must be the unit of analysis for

explaining much of social change is mainly sustained by the hypothesis of

“semiperipheral development.” Without looking at intersocietal relations it is

impossible to see this phenomenon.

Studies of

premodern interaction networks have found a pattern of pulsation in

which networks expand and contract over time, with an occasion vast new

expansion that integrates larger and larger territories. Recent waves of

globalization in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are a continuation of

this phenomenon. And another observation from comparing systems is that all

systems that have hierarchies exhibit a pattern of the rise and fall of

powerful polities. The modern rise and fall of hegemonic core states is thus

analytically similar to the rise and fall of empires and the rise and fall of

paramount chiefdoms.

Chase-Dunn and

Hall (1997) propose an explanation of human social evolution that combines

transformations of systemic logic across rather different modes of accumulation

with an underlying “iteration model” that posits causal relations among

population growth, intensification, population pressure, migration, circumscription,

conflict and hierarchy formation and technological change. It is an interaction

model because the outcomes (hierarchy formation and technological development)

have a positive effect on population growth, and so the model predicts a spiral

of world-system expansions.

A number of

important exogenous variable affect the iteration model. Climate change is

mainly an exogenous variable, though local climate may have also been impacted

by societies in the past, and is quite certainly being impacted in the present.

Geographical conditions can facilitate or hinder the emergence of larger

polities. Zoological and botanical capital can speed up processes of

technological development by providing species that are easily domesticated by

humans. And natural capital scarcity can also slow down technological change.

The

long-distance diffusion of domesticated crops and animals, and of technological

ideas from distant systems can have huge consequences for a local world-system

without signifying a systemic integration of the two systems. Systemic

integration requires two-way and regularized (frequent) interactions. Very

intermittent incursions or pandemic diseases can impact upon a system from

without. These possibilities of exogenous impacts on local and regional systems

need to be taken into account in order to fairly test the iteration model and

transformations of the modes of accumulation as explanations of human social

change.

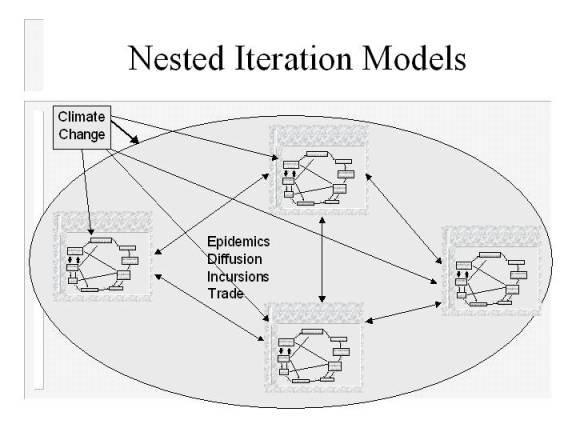

Figure 1: Regional iteration model

processes impacted by exogenous factors

It does not make sense to ask how many world-systems there were in prehistoric North America if we accept the group-centric approach to bounding world-systems mentioned above. If every group interacts with neighboring peoples then there are no major breaks in interaction across space. Thus there were as many "systemic wholes" as there were groups because each group had a somewhat different set of interactions.

Of course this is not to say that there were not differential densities of interaction. Natural barriers such as deserts, high mountains, and large bodies of water increased the costs of communication and transportation. But ethnographic and archaeological evidence reveals that most of these geographical "barriers" did not eliminate interaction. In California travel across the High Sierra was closed by deep snow in the winter. But when the snow thawed regularized trade across this high range resumed. Natural barriers do affect interaction densities, but in most cases they do not eliminate systemic interaction.

The

suggestion that "culture areas" -- the culturally similar regions

designated by anthropologists (e.g. California, the Pacific Northwest, the

Southwest, etc[1].) -- can be

equated with world-systems is fallacious from the group-centric point of view

because important interactions frequently occurred across the boundaries of

these culture areas. Nevertheless it is

convenient to follow Stephen Kowalewski’s

(1996) lead in discussing how the world-systems in these traditional

culture areas were similar or different from one another. The literature on trade networks by

archaeologists is usually organized into discussions of these culture areas,

but there has been more and more study of trade interactions between the different

culture areas.[2] This section

discusses the U.S. Southwest and those recent adjacent to it that may have been

in systemic interaction with the Southwest. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1998) also

examine the other describe the world-system aspects of the other “culture

areas” in that part of North America that became the United States.

Humans

came across the Aleutian land bridge at least thirteen thousand years ago. An encampment of hunter-gatherers near Monte

Verde, Chile, complete with chunks of Mastodon meat, has been firmly dated at

12,500 B.P. (10,500 B.C.E) The land route was difficult to pass before about

12,000 years ago because of the large Pleistocene glaciers. But it is possible

that maritime-adapted peoples moved along the coasts. Most archaeologists

discount the possibility of early voyaging across the open ocean.

In

the region that became the United States so-called Paleoindians used large

distinctively fluted stone spear points known as Clovis points[3]

over a wide region of North America.

Archaeologists think that the peoples who lived during the epoch they

call “Paleoindian” (usually from 10,000 B.C.E to 8,000 B.C.E.) were small

groups of big game hunting nomads who ranged over wide territories. In the case

of the Paleoindians archaeologists disagree about whether or not there was trade

among groups. Many Clovis points have been found that are made of stone that

came great distances. But since it is

thought that the nomadic Paleoindians ranged widely, it is possible that they

procured the materials directly from quarries rather than trading for them.

The

general model of social evolution that has most often been applied to North

America is that groups migrated to fill the land, then population increased,

and trade and complexity emerged. This general sequence is implied in the periodizations

that archaeologists have developed to characterize the cultures for which they

find evidence in North America. In every region the Paleoindian period was

followed by the Archaic, a period in which groups became more diversified

hunter-gatherers, restricted their migrations to smaller regions and developed

distinctive regional lithic styles.

Sometimes distinctions are made between the Lower and Upper Archaic. The

Archaic lasted longer in some regions than in others. After the Archaic, the

periodization terms differ from region to region. The general picture is one of increasing population

density, the development of more complex societies in each region and

increasing trade within and between regions. But this general model becomes

more complicated when we look more closely.

The trends toward greater population density, complexity and trade were

broken by cyclical processes of the rise and fall of hierarchies and

complexity, changes in the patterns of interaction within and between regions

and important differences in the timing and nature of social change across

regions.

The notion of widely nomadic populations becoming gradually more

sedentary is related to the problem of cultural differences, social identities

and territoriality. Archaeologists note

that stylistic differences among groups became more pronounced as nomadic

circuits became smaller and sedentism developed. This is interpreted as the

formation of local cultural identities by which people distinguished their own

communities from those of their neighbors.[4]

The wide circles of year nomadic treks of the Paleoindians with their

continentally similar Clovis spear-points were replaced by smaller regional and

intersecting circles of migration by groups hunting smaller game species and

using regionally distinct projectile points. Thus the spatial nature of nomadic

“settlement systems” shrank toward the eventual development of sedentism. A

system of moving people to resources was replaced by a system of moving

resources to people through trade networks. At first the trade networks were

small, but over time they grew larger. It is this latter process of trade

network expansion that brought small regional systems into greater interaction

with distant peoples. This is analogous to the sequence of network expansions

in waves that occurred in Afroeurasia since the emergence of sedentism that

began twelve thousand years ago in the Levant.

The Southwest

Most of the research on the Southwest that

explicitly uses world-systems concepts has focused on relations among societies

within the Southwest (e.g. Upham 1982; Spielmann 1991; Baugh 1991; Wilcox 1991,

McGuire 1993, 1996), but there has also been an important literature on the

relationship between the Southwest and Mesoamerica (discussed below). The term

"Pueblo" is the generic word that Spanish colonizers applied to

sedentary horticulturists found in what is now New Mexico and Arizona. These groups had only a few traits in

common: they built adobe villages with

a central plaza and ceremonial structures, and they grew corn, beans, and

squash. In historical times (i.e. after

the arrival of Spanish colonists) there was no overarching unity among the

Pueblo peoples, and warfare occasionally occurred between different Pueblo

villages. The people who occupied these

villages spoke languages from at least three different major linguistic stocks.

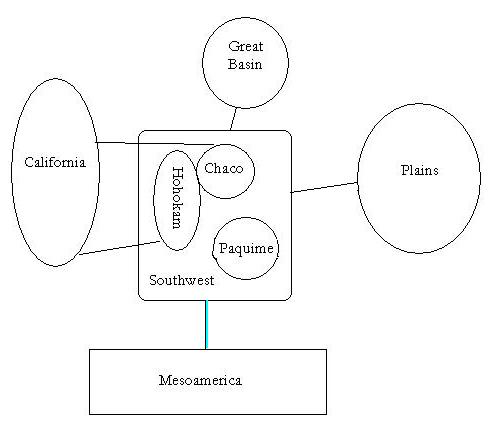

There are several culture

areas within the Southwest. The main centers that developed

political complexity about 1100 years ago were the

Hohokam in Arizona, the Anasazi Chacoan polities and a few centuries later,

Paquime (Casas Grandes) in Northern Chihuahua about 200 kilometers south of

Chaco Canyon (see Figure 3). Other important archaeologically known cultures in

the region are Mogollon and Mimbres.

Figure 3: Southwestern

macroregion and adjacent regions

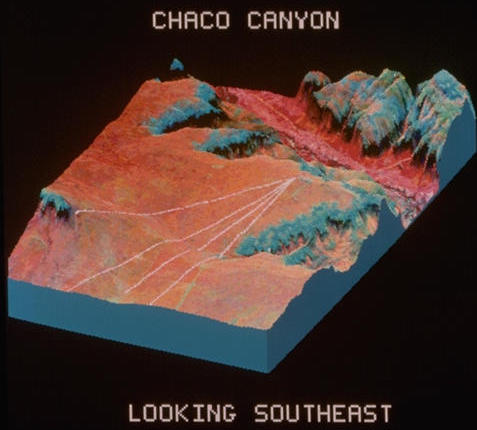

The ancestors of the historically known Pueblo Indians

were the Anasazi – the “people of old.” The Anasazi culture emerged from 900

C.E to 1150. Several large centers were built in this period. At Chaco Canyon a

very large center emerged in the tenth and eleventh centuries with perhaps more

than 10,000 people living in the Chaco core (Vivian 1990). The Chaco culture,

recognizable by distinctive pottery and architecture, spread widely in New Mexico

and Arizona through the establishment of many “Chaco outliers.”

After 1200 Chaco Canyon was

nearly abandoned as the region endured a fifty-year drought. Kintigh (1994:138)

notes that at the turn of the thirteenth century there was a renewed aggregation

of living units into large communities and abandonment of smaller

settlements. This suggests the

reestablishment of a regional system. This second wave of complexity also

collapsed. All this is reminiscent of the cycling, or rise and fall of

cheifdoms that Anderson (1994) describes for the prehistoric Southeast.

Stephen Lekson (1999) has formulated an explanation for

the rise and fall sequence of the Southwest that focuses on the significance of

what he calls the “Chaco Meridian.”

Lekson sees immense significance in the geographical aspects of the great

straight roads that radiated from the ritual center of Chaco Canyon.[5]

He notes that after the decline of Chaco the next large central place to emerge

in the region, the so-called Aztec Ruin on the Salmon River, is directly to the

north of Chaco and that one of the ritual roads goes north from Chaco in the

direction of the Aztec Ruin. And after the decline of Aztec a new, larger

central place emerged that we know as Paquime (Casas Grandes) in a region that

allowed for the building of an elaborate canal-based irrigation system.

Lekson makes much of the observation that Casas

Grandes, though 200 kilometers to the south of Chaco, is also exactly on the

Chaco Meridian. Lekson’s explanation focuses on a hypothetical religious elite

that adapted to successive drought crises by moving its center of operation

first directly north, and then directly south of its original cult center.

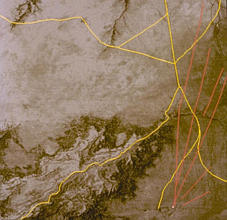

The

straight lines are the prehistoric roadways at Chaco Canyon

David

Wilcox’s (1999) interpretation of the hegemonic rise and falls in the Southwest

posits a system of competing polities that succeed one another rather than the

adaptation of a single cultural group that moves its center of operation. It

is, of course, possible that newly emergent groups tried to appropriate the

spiritual power and legitimacy of earlier dynasties. This phenomenon is well

known from state-based systems. So it is possible that Wilcox’s scenario can

also account for the phenomenon of the Chaco Meridian.

The debate over the nature of Southwestern complex

polities is reminiscent of similar controversies about Mississippian complex

chiefdoms. Wilcox points out that chiefdoms may be organized either around a

single sacred chief who symbolizes the apex of a polity or they may take a

different form that he calls “group-oriented” that is organized around a

council of chiefs. Few examples of

elite burials are found in the Southwest (though this may partly be a

consequence of the existence of cremation rituals). Wilcox contends that the

polity that emerged at Chaco Canyon started out as a ritual theocracy in which

an ethnic group of rainmakers migrated to the canyon, perhaps at the invitation

of the horticulturalists who already lived there. This group of ritual specialists

constituted a theocratic polity at first and the cult of the Great House was

established in the Chaco outliers to organize the collection of food and raw

materials. A new center was established at Aztec Ruin, but Wilcox believes that

this outlier became an independent and competing polity. He sees the emergence

of Chaco as stimulating secondary chiefdom formation in adjacent areas and the

emergence of “peer polities” that constitute a system of competing and allying

polities. Wilcox contends that institutionalized coercion eventually became a

more important feature of the Chacoan system. He cites evidence of mass burials

and cannibalism in the period just before the Chaco collapse. He characterizes

the transition from theocracy to institutionalized coercion as the emergence of

a tributary state. He thinks that the Chacoan hegemonic state conquered Chuska

to the east in order to gain control of timber resources.

But while Wilcox sees the Chacoan phenomenon as

involving a core/periphery hierarchy based on tribute-gathering, his

characterization of the Hohokam phenomenon in Arizona is quite different.

Hohokam settlements emerged in the context of the building of a large system

for irrigating maize horticulture in the Phoenix basis and adjacent regions. The

big Hohokam capital was a Snaketown. One of the main signatures of the Hohokam

religion was the circular ball court used in fertility rituals. The largest of

these ball courts was at Snaketown. Wilcox claims the centrality of Snaketown

was completely a matter of “ritual suzerainty” and that there was no coercive

element in the relationship between Snaketown and the Hohokam outliers.

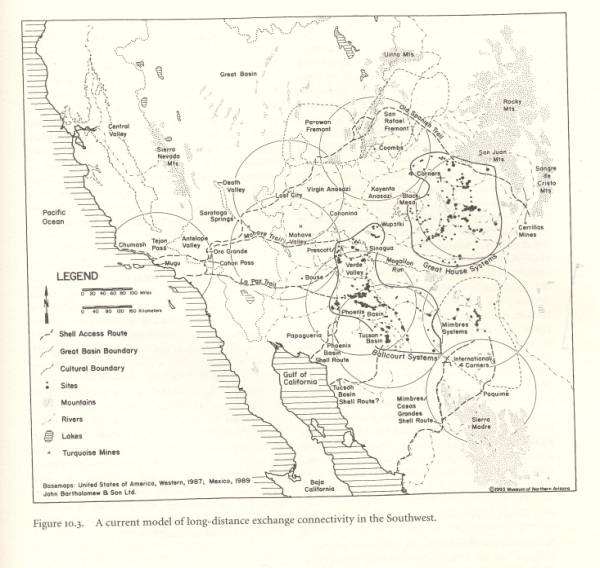

Figure 4: Trade connections between the Southwest and adjacent regions (Wilcox 1999)

Kowalewski’s (1996) comparison of the Southwest

with other U.S. culture areas describes a radical core/periphery identity

separation that emerged between closed corporate Pueblo communities of

horticulturalists and the more nomadic foragers and raiders that lived around

them. The Pueblo peoples live in defensible towns, often atop mesas

(flat-topped mountains), where they were able to protect their stores of corn

from nomadic raiders. And the dramatic Anasazi cliff dwellings (e.g. Mesa

Verde) have obvious defensive advantages.

But Feinman, Nicholas and Upham (1996), in

their explicitly world-systemic comparison of Mesoamerica and the Southwest

(which ignores the issue of the interaction between these two macroregions),

characterize the Southwest as a region in which networks were open and

permeable, without strong boundaries between societies. The contrast with Kowalewski’s portrayal is

vivid. Perhaps the earlier system was

open, while the bounded Pueblo communities emerged after the Spanish invasion

or after nomads obtained horses. But the existence of the Anasazi cliff

dwellings, built hundreds of years before the arrival of Spaniards and horses,

looks functionally quite similar to the mesa communities of historically known

Pueblos. It is a lot of trouble to

build houses into a cliff and carry water up from below. Defense against raiders would be a likely

explanation. Defensive communities and conflictive relations are often

associated with strong cultural boundaries between the conflicting groups.

In her discussion of

Plains/Pueblo interactions Katherine Spielmann (1991a, 1991b, 1991c) delineates

two ways in which exchange between what had heretofore been relatively

autonomous groups might have developed into systemic exchange (core-periphery

differentiation in world-system terms).[6] The first, which she favors, is mutualism, in which sedentary

horticulturalists engage in systematic exchange with nomadic hunters in such a

way that the total caloric intake over the necessary variety of food types

mutually benefits both groups. The second,

favored by Wilcox (1991) and Baugh (1991), is buffering in which sedentary agriculturists use exchange with

nomadic hunters to supplement food supplies during periods of scarcity.

The issue of pacific vs. conflictive

relations between horticulturalists and foragers has been raised in many other

contexts. Gregg’s (1988) discussion of

the expansion of gardening into Europe portrays a symbiotic relationship

between farmers and foragers who exchanged complementary goods. Spielmann’s

(1991) rendering of this relationship in the Southwest also favors a symbiotic

interpretation in which complementary surpluses were exchanged between Pueblos

and nomadic foragers. Baugh (1991) uses world-systems concepts to analyze this

same relationship. Both he and Wilcox (1991) see elements of a core/periphery

hierarchy in which the sedentary groups (Pueblos) were benefiting more than the

nomadic foragers from the interaction.

One

hypothesis that stems from the iteration model of world-systems evolution

(Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 6) is that all systems go through cycles of

increase and decrease in the level of conflict among societies. Farmer/forager interactions are more likely

to be symbiotic under conditions of low population pressure, but when

ecological degradation, climate change or population growth raises the costs of

production, conflict among societies is likely to increase. It is during these periods that new

institutional solutions are more likely to be invented and implemented. But if

new hierarchies or new technologies are not employed conflict itself will

reduce the population and a period of relative peace will return.

Randall

McGuire’s (1996) study of core/periphery relations in the Hohokam interaction

sphere reveals evidence of the rise of a culturally innovative center near what

is now Phoenix, Arizona. Several different surrounding peripheral regions

adopted styles from this core. McGuire demonstrates the dangers of applying

assumptions based on the modern world-system to stateless systems. He finds

that the peripheral Hohokam regions did not culturally converge, but rather

they become more different from one another as climate changed and they

interacted with other distant core regions.

Of course the hypothesis of convergence among peripheral regions is also

contradicted for the modern world-system because peripheral areas often

experience quite different developmental paths.

Little is known

archaeologically about nomad-nomad relations in the Southwest. Some of the

nomadic groups may have been recent arrivals (Wilcox 1981a). Baugh (1991) and Wilcox (1991) suggest that

trade among nomadic foragers was an alternative to centralization in

stabilizing volatile food supplies. The arrival of Spaniards (from 1530s on)

vastly disrupted intergroup relations (see Hall 1989). The alliances that some of the nomadic

groups made with the Spanish (e.g. the Comanches) may have had prehistoric

analogues in which nomadic groups allied with particular Pueblo core societies

to provide protection against other nomadic groups, and possibly to serve as

allies in disputes among Pueblo societies.

The

nested network approach to bounding world-systems is helpful for understanding

the ways in which precontact North American societies were linked to one

another and the relevance of these links for processes of development. As with

state-based systems, bulk goods, political-military interactions, prestige

goods networks and information networks formed a set of nested nets of

increasing spatial scale. Some of the earliest explicit usage of world-systems

concepts by archaeologists (Whitecotton

and Pailes 1986; Weigand and Harbottle 1977) were arguments that the Southwest

constituted a periphery of the Mesoamerican world-system.

There

has been a huge controversy about the importance or unimportance of links

between the U.S. Southwest and Mesoamerica (Mathien and McGuire 1986; Cobb

Maymon and McGuire 1999)). An early

advocate of the importance of these linkages was Charles Dipeso (1974) who

argued that the great houses at Chaco Canyon were erected as warehouses and

dwellings for a small group of Toltec traders, the pochteca[7]. DiPeso contended that it was the withdrawal

of the Toltec pochteca in the twelfth

century that prompted the rapid decline of the Chaco Canyon polity.

That there were at least

some connections between the Greater Southwest and Mesoamerica is now widely

accepted. However, their importance for

local development is still the subject of considerable dispute. Weigand

and Harbottle (1993) continue to argue that the Southwest was a periphery of

Mesoamerica based on the proven fact that turquoise from the Cerrillos Hills

just south of Santa Fe was mined and exported to the states in the Valley of

Mexico (where Mexico City now is). They

claim that turquoise played an important role in the overall structure of trade

between these two regions and that the demand for turquoise was an important

factor in the rise of complex societies in the Southwest. Other features of societies in the

Southwest, such ball-courts, ceremonial mounds and scarlet macaws kept as pets,

also suggest influences from Mesoamerica. Striking similarities in Southwestern

and Mayan mythology (spider woman, warrior twins, etc.) are downplayed by Cobb,

Maymon and McGuire (1999). They suggest that the feather-serpent motif

associated with Quetzecoatl may have been part of an ancestral mythology common

to all the Native Americans. Cobb, Maymon and McGuire also contend that

important large settlements in Western Mexico linked to the states of the Valley

of Mexico were are relatively recent phenomenon, and that before that the huge

region of northern Mexico was inhabited only by nomadic foragers.

Late Mississippian chiefdoms such as that at

Etowah in Georgia have been found to have produced iconographs that employ

design elements and symbolic content that is strikingly similar to the icons of

Mesoamerican states (see Figure 3). (e.g. Anderson (1994:83). Archaeologists refer to the cultural complex

that produced these iconographs as the “Southern Cult” (Galloway 1989). Most

archaeologists contend that influences from Mesoamerica were unimportant to the

processes of development that occurred in the Southwest and other areas of what

is now the United States. Some argue that these cultural resemblances are due

to parallel evolution, not interaction (e.g. Fagan 1991).

Figure 3:This iconograph was found at Etowah , Georgia. (Anderson (1994:83)

The evidence of turquoise sourcing shows that there was definitely

trade between highland Mesoamerica and the Southwest. Certainly there was

down-the-line trade, but there could have also been at least a few

long-distance trade expeditions undertaken by pochteca from the Mexican highlands or from Western Mexico. It is

hard to imagine how down-the-line trade could have transmitted the ideologies

behind the iconographs of the Southern Cult, though the predominant consensus

among both Southwestern and Southeastern archaeologists (e.g. Webb 1989; Cobb,

Maymon and McGuire 1999) is that direct influence was slight. The predominant

opinion among archaeologists after a several decades of dispute is that local

and regional processes were much more important determinants of development in

the Southwest and the Southeast than were the long-distance connections with

Mesoamerica.

The Plains

The

Plains Indians are best known in the ethnographic literature for large bands of

horsemen who hunted buffalo and made war.

But horses were introduced by Spaniards in the sixteenth century and

rapidly adopted by nomadic groups on the Plains. The coming of the horse had a

revolutionary effect on the societies of the Plains because of increased

mobility and increased efficiency of the hunt.

Groups that formerly needed to disperse to find food could now come

together to form larger polities and alliances. These developments had important affects on adjacent regions

where peoples both adopted Plains features and organized to defend against the

military power of the Plains peoples.

But an earlier story is less well known. Contemporaneous with the emergence of the

Mississippian interaction sphere was the florescence on the southern Plains of

a mound-building culture that had important trade and cultural links with both

the Mississippian heartland, especially Spiro, and with the Southwest (Vehik

and Baugh 1994). This is known as Caddoan culture. The Caddoans built large mounds and villages and planted corn,

but they were culturally somewhat

different from similarly complex societies to the east and west. This cultural distinction might be

interpreted as only marginal differentiation if we did not also know that the

Caddoans cut themselves of from trading beyond the Plains and constructed a

network centered on the Caddoan heartland (Vehik and Baugh 1994). This was an instance of a semiperipheral

region turning itself into a core by means of delinking from other distant

cores. Around 1200 C.E. Caddoan trade

with the Mississippian societies collapsed.

This caused societies on the eastern Plains (on the border between the

Plains and the Mississippian interaction sphere) to decrease in

complexity. It also created a Plains

trade network centered in the Caddoan heartland that was largely separated from

both the Southwest and the Mississippian networks. Later the Caddoan core declined at about the same time as the

Cahokian core chiefdoms. And this was contemporaneous with declines in the

Southwest. A fascinating instance of synchronous growth/decline phases of

cities and empires in East and West Asia from 650 BCE to 1500 CE (Chase-Dunn,

Manning and Hall 2000) suggests the possibility of similar synchronies in the

growth/decline sequences in the Americas.

The

Great Basin

In what are now the states of Utah,

Nevada and eastern California is a region of high desert in which water does

not flow to the seas, but rather into large land-locked basins. Some rather

large rivers run for hundreds of miles and disappear into the sand. It is an ecologically sparse environment

that is punctuated by small areas where water, game and plant life are more

abundant. In addition to the lack of rainfall in most areas, the distribution

of rainfall varies greatly from year to year. This ecologically coarse

environment was the home of nomadic foragers, known ethnohistorically as the

Paiute, the Western Shoshone and the Ute, who adapted to the desert environment

by moving to where food was most available. This region was also the

inspiration of the theory of social evolution known as cultural ecology that

emphasizes the importance of social adaptations to the local environment.

Julian Steward, a major figure in the development of cultural ecology (1938;

1955), did important ethnographic surveys in which he charted population

densities across the entire Great Basin region and analyzed why there were

important organizational and cultural differences among the ethnohistorically

known groups in this large region. The ecological constraints on human

societies are dramatic in the basin and range geography studied by Stewart.

As the debate about whether or not

the Southwest was a periphery of Mesoamerica has raged, there has been an

analogous controversy over whether or not the Great Basin was a periphery to

the Southwest. The early peoples who

moved into the Great Basin occupied the few locations where there were good

supplies of game and food plants. Subsequent population growth and more recent

arrivals led groups to occupy more marginal regions. What emerged was a mosaic of social structures that mapped the

ecological geography almost perfectly. The desert mosaic was composed of small

settled groups near isolated food resources (e.g. near rivers and lakes)

surrounded by more nomadic groups who were following the yearly variation in

food availability. This desert mosaic

was impinged upon by outside influences from California, the Plains and the

Southwest, but despite these factors and changes in climate, the basic mosaic

pattern still existed when the Euroamericans came to explore this region in the

1840s.

Southwestern-type village-living horticulturalists and pot-makers,

called the Fremont culture, emerged in the southern Great Basin in about 400

C.E. Upham (1994) has argued that Great

Basin peoples alternated back and

forth from settled versus nomadic strategies depending on climatic, ecological

and interactional shifts. Trade

networks that are visible in the potsherd evidence (broken pieces of pots with

distinctive designs) indicate that the settled groups used trade networks to

insure against local food shortages (McDonald 1994). Between 1250 and 1350 C.E. the Fremont peoples abandoned the

Great Basin, probably because of the droughts of the Little Ice Age. It was

this same climatic change that probably caused the abandonment of the Anasazi

regions on the Colorado plateau to the south.

New groups of people, presumably the ancestors of the Shoshoni, may have

moved into the region at this time (Madsen and Rhode 1994).

Julian

Steward’s (1938) analysis shows that

the local sedentary core groups developed religious rituals, collective

property rights, and political organization at the village level, whereas their

more nomadic neighbors existed primarily with only family-level

organization. Steward does not discuss

the interactions among these groups. Indeed he claims that there was little

trade and little interaction. But the

groups occupying prime sites would have needed to protect their resources from

intruders. They developed political organization to regulate internal access,

but also to protect from external appropriation. Steward argues that warfare was not an important emphasis for any

of these groups, except those few who adopted some of the cultural trappings

from neighboring societies on the Great Plains. Nevertheless the development of bounded territories and the

enforcement of legitimate claims to resources by means of coercion – even if

only yelling and stone-throwing – represented an institutional response to a

core/periphery differentiation in which some groups needed to protect their

ecological resources from other groups.

As for the peripheral peoples, their culture, as

Steward (1938) says, was primarily

“gastric” -- focused on food. In order

to not starve they needed to cache enough food to survive through the winter.

The key food for this purpose was the nut from the cone of the Pinion

pine. These were available for harvest

in the fall. Pinion nut crops varied

greatly from location to location and from year to year, and when they were

plentiful in one location there was usually enough for all those who had the ability

to harvest and process them. This set of characteristics was not propitious for

the development of property rights, and so groups did not try to control

particular Pinion stands.

This

was a rather elemental form of a local core/periphery structure. There was no

core/periphery hierarchy in which core societies exploited the labor or

resources of peripheral societies. What the core societies did was to protect

their assets from potential peripheral intruders. And for their part the peripheral peoples were disorganized by

the ecological circumstances, in which “optimal foraging strategy” dictated

that they remain spread out in very small groups. Thus when hunger gripped them

they had not the ability to attack the stores of the core societies. Rather

they simply starved.

Contrary to Steward’s claim that

Great Basin peoples did not trade, their is ample archaeological evidence that

they did participate in long distance trade networks.

Bennyhoff

and Hughes (1987) show that an olivella shell-based trade network that linked

the Western Great Basin to the coast of Northern California expanded from 2000

B.C.E. to 200 B.C.E. and then contracted from 200 B.C.E. to 700 C.E. and then

expanded again from 700 C.E. to 1500 C.E.

After 1500 C.E. there was a major expansion within California based on a

different kind of shells (clam disk beads), but this network did not extend

into the Great Basin. Hughes (1994)

shows that two cave dwellings in the Western Great Basin that are rather close

to one another, were parts of very different obsidian exchange networks, but

were linked into the same shell network. This cautions us against assuming that

all sorts of trade items fit into the same exchange networks.

California

This

section considers the whole California culture area in comparative perspective.

In California only a few societies had clans and moieties,[8]

and there were no hierarchical kinship systems. In the area of Northern California that was studied by Chase-Dunn

and Mann (1998) (see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 7) the largest

polity was the tribelet, a very small unit consisting of a few villages. Larger political entities did not exist

except in the San Joaquin Valley (Yokuts) and in Santa Barbara (Chumash). Though California has been characterized as

a culture area based on social structural and artifactual similarities, there

were enormous differences within California as well. Linguistic differences are the most obvious. Linguists contend that six major linguistic

stocks were present in indigenous California.

Whereas clay pots were not used by most of the indigenous peoples of

California, the Western Mono, Paiute and some of the Yokuts peoples made

pottery in southeastern California. The

only maize horticulturalists in California lived along the Colorado River on

the border between California and Arizona, although nearly all groups in

California planted small amounts of tobacco.

We have already mentioned the

studies of trade linkages between California and the Great Basin. These show

that the expansion and contraction of trade networks is a feature of

intersocietal relations even when the constituent societies are very

egalitarian. Shell and shell artifacts from the Pacific were traded with the

Southwest. Wilcox (1999) emphasizes the notion that the Chumash traded abalone

shell and shell fishhooks with the Chacoans.

Interaction Nets over the Long Run

Rather than a

simple model of interaction nets getting larger, the sequence found in several

North American regions shows a more complicated pattern. The “settlement

systems” of nomads were spatially huge as they ranged over great territories.

As population density increased these nomadic ranges became smaller until the

transition to sedentism emerged. The first sedentary societies had very small

interaction nets, but these got larger and then smaller again, and then once

again larger. This is network pulsation.

The early Paleoindians were explorers and colonizers of land that was yet uninhabited. They chased herds of big game, and they also tended to concentrate in areas that had greater amounts of game and other foods (Anderson 1995). As with other colonization sequences, the first arrivals probably took the best locations and then tried to hang on to them. Population density was so low at first that there were plenty of good new locations, and so interactions among groups were mainly friendly. But as the best locations became utilized and the megafauna became scarce, more competition emerged. Some groups developed seasonal migration rounds in particular territories and tried to defend the best camping sites against new arrivals. The small bands always needed to gather with other bands seasonally to trade and exchange marriage partners. But the sizes of these seasonal gatherings were limited by the availability of food stocks at the meeting place.

A kind of

territoriality emerged among nomads, but it was probably not well

institutionalized. We do not know whether or not the Paleoindian pioneers

brought with them a cultural apparatus for claiming and defending collective

territory. The Polynesian pioneers of the Pacific brought with them an

ancestral culture that included the concepts of mana an tapu [9]that

were the basis of sacred chiefdoms. The Polynesians temporarily abandoned

ceremony and hierarchy and to become egalitarian hunter-gatheres when they

landed on islands populated by large and delicious flightless megabirds (e.g.

New Zealand). But when the birds were all eaten, the Polynesians reconstructed

class societies and territoriality using the linguistic and ideological

equipment that was embedded in their ancestral culture.

Very likely the immigrants to North America did not have such a hierarchical cultural heritage because the Asian societies from whence they came had not yet developed ideas and kin relations appropriate to the symbolization of the linkage between place and blood. This means that the original America pioneers had to invent these institutions as they came to need them.

The Paleoindian interaction networks were large, especially for exchanging fine and useful objects such as Clovis points and exotic lithic blanks. Cultural styles were widely shared across macroregions. And the territories exploited by human groups were huge, though the numbers of people in each macroband were small. As bands became somewhat less mobile they developed more differentiated tool-kits depending in part on the nature of the territories they inhabited, but also as a way of symbolizing alliances with friends and differences with foes.

The question of

systemic versus conjunctural or intermittent relations among macro-regions in

prehistoric North America remains. The consensus among archaeologists is that

the patterns of network development, complexity and hierarchy seen in the

Southwest were predominantly endogenously caused, though exogenous impacts from

climate change obviously were important. The notion that Toltec pochtecas from

Mesoamerica were major players in the emergence of large polities in the

southwest has been largely dismissed and no direct evidence in support of this

idea has been found. The idea that the export of turquoise to the South had an

important impact on developments in the Southwest is plausible, but the

mechanisms by which this may have worked have not been investigated. Did the

mining and trading of turquoise play an important role in the development of

the Chacoan polity? The turquoise trade constitutes a prestige good connection

with Mesoamerica, but how important was it in terms of volume and what role did

it play in Southwestern social change? These questions have not been answered

by those who point to the turquoise connection as evidence that the Southwest

was a periphery of Mesoamerica.

References

Anderson, David

G. 1994. The Savannah River

Chiefdoms: Political Change in the Late

Prehistoric Southeast. Tuscaloosa,

AL: University of Alabama Press.

Baugh, Timothy. 1984. "Southern

Plains Societies and Eastern Frontier Pueblo Exchange during the Protohistoric

Period." Pp. 156-67 in Papers of the Archaeological Society of New

Mexico, Volume 9. Albuquerque: Archaeological Society Press.

_____. 1991. "Ecology and Exchange:

The Dynamics of Plains-Pueblo Interaction." Pp. 102-107 in Farmers,

Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the Southwest and the Southern

Plains, edited by Katherine A. Spielmann. Tucson: University of Arizona

Press.

_____. 1992. "Regional Polities and

Socioeconomic Exchange: Caddoan and Puebloan Interaction." Paper presented

at Southeast Archaeological Conference, Little Rock, AR.

Baugh, Timothy G. and Jonathan E. Ericson

(eds.) Prehistoric Exchange Systems in North America. New York: Plenum

Press.

Bennyhoff, J.A. and R.E. Hughes 1987 "Shell bead and ornament exchange networks between California and the Great Basin" Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 64,2.

Blanton, Richard, Stephen Kowalewski and

Gary Feinman 1992 "The Mesoamerican world- system" Review

15,3:419-426.

Brandt, Elizabeth A. 1994.

"Egalitarianism, Hierarchy, and Centralization in the Pueblos." Pp.

9-23 in The Ancient Southwestern Community: Models and Methods for the Study

of Prehistoric Social Organization. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico

Press.

Brose,

David S. 1994 "Trade and exchange in the Midwestern United States,"

in Baugh

and

Ericson.

Caldwell,

Joseph R. 1964 "Interaction spheres in prehistory." Hopewellian

Studies 12,6:133-156 Springfield,IL.: Illinois State Museum Scientific

Papers

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems

Boulder, CO.: Westview Press.

Christopher

Chase-Dunn and Thomas D. Hall, 1998

"World-Systems in North America: Networks, Rise and Fall and Pulsations of

Trade in Stateless Systems," American Indian Culture and Research

Journal 22,1:23-72.

http://wsarch.ucr.edu/archive/papers/c-d&hall/isa97.htm

Christopher

Chase-Dunn and Andrew K. Jorgenson, “Regions and Interaction Networks: an

institutional materialist perspective,” 2003

International Journal of Comparative Sociology

44,1:433-450.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Kelly M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and Their Neighbors: A

Very

Small World-System in Northern California. University of Arizona Press.

Chase-Dunn, C., Susan Manning

and Thomas D. Hall 2000 “Rise and fall: East-West

synchrony

and Indic exceptionalism reexamined,” Social

Science History 24,4:727-

754.

Cobb,

Charles R. Jeffrey Maymon and Randall McGuire 1999 “Feathered, horned and

antlered serpents: Mesoamerican connections with

the Southwest and the Southeast”

Pp. 165-182 in Neitzel.

Collins,

Randall 1992 "The geographical and economic world-systems of kinship-based

and

agrarian-coercive societies." Review

15,3:373-88 (Summer). Westport, CT.:

Greenwood Press.

Dean,

Jeffrey S., George J. Gumerman, Joshua M. Epstein, Robert L. Axtell, Alan C.

Swedlund, Miles T. Parker and Stephen McCarroll

2000 “Understanding Anasazi

culture change through agent-based modeling,” Pp.

179-206 in Kohler and

Gumerman.

Dozier,

Edward P. 1970. The Pueblo Indians of North America. New York: Holt,

Rinehart and Winston.

Ericson,

Jonathan and Timothy Baugh (eds.) 1993 The American Southwest and

Mesoamerica: Systems of Prehistoric Change. New York: Plenum.

________________________________1994

"Systematics of the study of prehistoric

regional

exchange in North America," Pp. 3-16 In Timothy Baugh and Jonathan E.

Ericson (eds.) Prehistoric Exchange Systems in North America. New York:

Plenum Press.

Fagan,

M. Brian 1991 Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent. London:

Thames and Hudson.

Feinman,

Gary. M., and Linda. M. Nicholas. 1996. "The Changing Structure of

Macroregional Mesoamerica." Journal of World-Systems Research 2:x.

Feinman,

Gary, Linda Nicholas and Steadman Upham 1996 "A macroregional

comparison

of the American Southwest and Highland Mesoamerica in pre-Columbian times:

preliminary thoughts and implications" PP. 65-76 in Peregrine and Feinman.

Feinman,

Gary and Jill Neitzel 1984 "Too many types: an overview of sedentary

prestate societies in the Americas" Pp. 39-102 in M. B. Schiffer (ed.) Advances

in Archaeological Method and Theory, Volume 7. New York: Academic Press.

Ford,

Richard I. (19xx) “Inter-indian exchange in the Southwest,” Pp. 711-722 in

Alfonso

Ortiz (ed.) Handbook of North American Indians,

Vol. 10, Southwest. Washington DC:

Smithsonian Press.

Foster,

Michael S. 1986. "The Mesoamerican Connection: A View from the

South." Pp. 55-

69 in Ripples in the Chichimec Sea: New

Considerations of Southwestern-Mesoamerican

Interactions, edited by Frances Mathien and Randall McGuire. Carbondale, IL:

Southern Illinois University Press.

Gregg,

Susan A. 1988 Foragers and Farmers: Population Interaction and Agricultural

Expansion in Prehistoric Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

______(ed.)

1991 Between Bands and States. Center for Archaeological Investigations,

Occasional Paper #9, Carbondale, IL.: Soutehern Illinois University.

Habicht-Mauche,

Judith A. 1991. "Evidence for the Manufacture of Southwestern-style

Culinary Ceramics on the Southern

Plains." Pp. 51-70 in Farmers, Hunters, and

Colonists: Interaction Between the Southwest and

the Southern Plains, edited by

Katherine A.

Spielmann.

Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Hall,

Thomas D. 1989. Social Change in the Southwest, 1350-1880. Lawrence, KS:

University Press of Kansas.

_____________.

1991 "Nomadic peripheries" in C. Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.)

Core/Periphery Relations in Precapitalist Worlds. Boulder, CO.: Westview.

Hughes,

Richard E. 1994 "Mosaic patterning in prehistoric California-Great Basin

exchange," Pp. 363-384 in Baugh and Ericson.

Johnson,

Gregory A. 1989. "Dynamics of Southwestern Prehistory: Far

Outside--Looking

In." Pp. 371-389 in Dynamics of Southwest

Prehistory, edited by Linda S. Cordell and

George J. Gumerman. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian

Institution Press.

Johnson,

Jay K. "Prehistoric exchange in the Southeast," Pp. 99-126 in Baugh

and Ericson.

Kohler,

Timothy A. and George J. Gumerman (eds.) Dynamics in Human and Primate

Societies.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Kohler,

Timothy A., James Kresl, Carla Van West, Eric Carr and Richard H. Wilshusen

2000

“Be there then: a modeling approach to settlement

determinants and spatial

efficiency among late ancestral Pueblo populations

of the Mesa Verde Region, U.S.

Southwest,”Pp. 145-178 in Kohler and Gummerman.

Kintigh,

Keith W. 1994. "Chaco, Communal Architecture,and Cibolan

Aggregation."

Pp,

131-140 in The Ancient Southwestern Community: Models and Methods for the

Study of Prehistoric Social Organization. Albuquerque: University of New

Mexico Press.

Kirch,

Patrick V. 1984 The Evolution of Polynesian Chiefdoms. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Lafferty,

Robert H. III 1994 "Prehistoric exchange in the Lower Mississippi

valley," Pp. 177-214 in Baugh and Ericson.

Leckson,

Stephen H. 1999 The Chaco Meridian: Centers of Political Power in the

Ancient Southwest.

Walnut Creek, CA; Altamira Press.

Levine,

Francis. 1991. "Economic Perspectives on the Comanchero Trade." Pp.

155-169

in

Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the Southwest and the

Southern Plains, edited by Katherine A. Spielmann. Tucson: University of

Arizona Press.

Lintz,

Christopher. 1991. "Texas Panhandle-Pueblo Interactions from the

Thirteenth Through the Sixteenth Century." Pp. 89-106 in Farmers,

Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the Southwest and the Southern

Plains, edited by Katherine A. Spielmann. Tucson: University of Arizona

Press.

Mathien,

Frances. 1986. "External Contacts and the Chaco Anasazi." Pp. 220-242

in Ripples in the Chichimec Sea: New Considerations of

Southwestern-Mesoamerican Interactions, edited by Frances Mathien and

Randall McGuire. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Mathien,

Frances Joan and Randall McGuire, eds. 1986. Ripples in the Chichimec Sea:

Consideration

of Southwestern-Mesoamerican Interactions. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

McGuire,

Randall H. 1980. "The Mesoamerican Connection in the Southwest." Kiva

46:1-2:3-38.

_____.

1983. "Prestige Economies in the Prehistoric Southwestern Periphery."

Paper presented at Society for American Archaeology, Pittsburgh.

_____.

1986. "Economies and Modes of Production in the Prehistoric Southwestern

Periphery." Pp. 243-269 in Ripples in the Chichimec Sea: New

Considerations of Southwestern-Mesoamerican Interactions, edited by Frances

Mathien and Randall McGuire. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University

Press.

_____.

1989. "The Greater Southwest as a Periphery of Mesoamerica. Pp. 40-66 in Centre

and Periphery: Comparative Studies in Archeology, edited by Timothy

Champion. London: Unwin.

_____.

1992. A Marxist Archaeology. New York: Academic.

_____. 1996.

"The Limits of World-Systems Theory for the Study of Prehistory." Pp.

51-

64

in Pre-Columbian World-Systems, edited by Peter N. Peregrine and Gary M.

Feinman. (Monographs in World Archaeology No. 26) Madison, WI: Prehistory

Press, 1996.

Neitzel,

Jill E. 1994. "Boundary Dynamics in the Chacoan Region System." Pp.

209-

240

in TheAncient Southwestern Community: Models and Methods for the Study of

Prehistoric Social Organization. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico

Press.

Neitzel,

Jill E. (ed.) Great towns and regional polities in the prehistoric American southwest

and southeast. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

O'Brien,

Patricia 1992 "The world-system" of Cahokia within the middle

Mississippian

tradition," Review 15,3:389-418 (Summer).

Pailes,

Richard A. and Joseph W. Whitecotton. 1975. "Greater Southwest and

Mesoamerican World-Systems." Paper presented at the Southwestern

Anthropological Association meeting, Santa Fe, NM, March. Revised version

published 1979. [This is the first application of world-system theory to

precapitalist settings]

_____.

1979. "The Greater Southwest and Mesoamerican "World" System: an

Exploratory Model of Frontier Relationships." Pp. 105-121 in The

Frontier: Comparative Studies, Vol. 2, edited by W. W. Savage and S. I.

Thompson. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Patterson,

Orlando. 1982. Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Peregrine,

Peter. 1991. "Prehistoric Chiefdoms on the American Mid-contentinent: A

World-system Based on Prestige Goods." Pp. 193-211 in Core/Periphery

Relations in Precapitalist Worlds, edited by Christopher Chase-Dunn and

Thomas D. Hall. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

_____.

1992. Mississippian Evolution: A World-System Perspective. Monographs in

World Archaeology No. 9. Prehistory Press, Madison, WI.

_____.

1995. "Networks of Power: The Mississippian World-System." Pp.

132-143 in Native American Interactions, edited by M. Nassaney and K.

Sassaman. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press.

_____.

1996a. "Archaeology and World-Systems Theory." Sociological

Inquiry.

______1996b

"Hyperopia or Hyperbole?: the Mississippian World-System" Pp.39-50 in

Peter N. Peregrine and Gary M. Feinman (eds.) Pre-Columbian World Systems.

Madison: Prehistory Press.

Peregrine,

Peter N. and Gary M. Feinman. 1996. PreColumbian World Systems.

(Monographs in World Archaeology No. 26) Madison, WI: Prehistory Press.

Price,

T. Douglas and James A. Brown (eds.) 1985. Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers: The

Emergence of Cultural Complexity. New York: Academic Press.

Spielmann,

Katherine A. 1989. "Colonists, Hunters, Farmers: Plains-Pueblo Interaction

the Seventeenth Century." Pp. 101-113 in Columbian Consequences.

Volume 1: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on the Spanish

Borderlands, edited by David Hurst Thomas. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian

Institution Press.

_____,

ed. 1991a. Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the

Southwest and the Southern Plains. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

_____.

1991b. "Interaction Among Nonhierarchical Societies." Pp. 1-17 in in Farmers,

Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the Southwest and the Southern

Plains, edited by Katherine A. Spielmann. Tucson: University of Arizona

Press.

_____.

1991c. "Coercion or Cooperation? Plains-Pueblo Interaction in the

Protohistoric Period." Pp. 36-50 in Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists:

Interaction Between the Southwest and the Southern Plains, edited by

Katherine A. Spielmann. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Stark,

Barbara. 1986. "Perspectives on the Peripheries of Mesoamerica." Pp.

270-290 in Ripples in the Chichimec Sea: New Considerations of

Southwestern-Mesoamerican Interactions, edited by Frances Mathien and

Randall McGuire. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Steward,

Julian 1938 Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups. Bureau of

American

Ethnology, Bulletin 120 Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution

Tainter,

Joseph A. 1988. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge

University

Press.

Upham,

Steadman. 1982. Polities and Power: An Economic and Political History of the

Western Pueblo. New York: Academic Press.

_____.

1986. "Imperialists, Isolationists, World Systems and Political Realities:

Perspectives on Mesoamerican-Southwestern Interaction." Pp. 205-219 in Ripples

in the Chichimec Sea: New Considerations of Southwestern-Mesoamerican

Interactions, edited by Frances Mathien and Randall McGuire. Carbondale,

IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

_____.

1990. The Evolution of Political Systems: Sociopolitics in Small-Scale

Sedentary Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

_____.

1992. "Interaction and Isolation: The Empty Spaces in Panregional

Political and Economic Systems." Pp 139-152 in Resources, Power, and

Interregional Interaction, edited by Edward Schortman and Patricia Urban.

New York: Plenum Press.

Upham,

Steadman, Gary Feinman and Linda Nicholas. 1992. "New Perspectives on the

Southwest and Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregional Approach." Review

15:3(Sum.):427-451.

Upham,

Steadman, Kent G. Lightfoot, and Roberta A. Jewett, eds. 1989. The

Sociopolitical Structure of Prehistoric Southwestern Societies. Boulder,

CO: Westview Press.

Vehik,

Susan C. and Timothy G. Baugh 1994 "Prehistoric Plains trade," Pp.

249-274 in

Baugh

and Ericson.

Weigand,

Phil C. 1992. "Central Mexico's Influences in Jalisco and Nayarit During

the Classic Period. Pp. 221-232 in Resources, Power, and Interregional

Interaction, edited by Edward Schortman and Patricia Urban. New York:

Plenum Press.

Weigand,

Phil C., Garman Harbottle and Edward V. Sayre

1977

"Turquoise sources and source analysis: Mesoamerica and the Southwestern

U.S.A." Pp. 1534 in T. K. Earle and J. E. Ericson (eds.) Exchange Systems

in Prehistory. New York: Academic Press

Weigand,

Phil C. and Garman Harbottle 1993 "The role of turquoises in the ancient

Mesoamerican trade structure," Pp. 159-178 in Ericson and Baugh.

Whitecotton,

Joseph W. and Richard A. Pailes. 1979. "Mesoamerica as an Historical Unit:

A World-System Model." Paper presented to XLIII International Congress of

Americanists, Vancouver.

_____.

1983. "Pre-Columbian New World Systems." Paper presented at Society

for American Archaeology, Pittsburgh.

_____.

1986. "New World Precolumbian World Systems." Pp. 183-204 in Ripples

in

the

Chichimec Sea: New Considerations of Southwestern-Mesoamerican Interactions, edited by Frances Mathien and Randall McGuire.

Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press

Wilcox,

David R. 1984 "Multi-Ethnic Division of Labor in the Protohistoric

Southwest

During the Protohistoric Period." Pp. 141-154

in Papers of the Archaeological Society of

New Mexico 9. Albuquerque: Archaeological Society Press.

_______

1986a. "A Historical Analysis of the Problem of Southwestern-Mesoamerican

Connections." Pp. 9-44 in Ripples in the Chichimec Sea: New

Considerations of Southwestern-Mesoamerican Interactions, edited by Frances

Mathien and Randall McGuire. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University

Press.

_____.

1986b. "The Tepiman Connection: A Model of Mesoamerican-Southwestern

Interaction. Pp. 135-154 in Ripples in the Chichimec Sea: New Considerations

of Southwestern-Mesoamerican Interactions, edited by Frances Mathien and

Randall McGuire. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

_____.

1991. "Changing Contexts of Pueblo Adaptations, A.D. 1250-1600." Pp.

128-154 in Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the

Southwest and the Southern Plains, edited by Katherine A. Spielmann.

Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

_____.

1993. "The Evolution of the Chacoan Polity." Pp. 76-90 in Chimney

Rock Achaeological Symposium, edited by J. McKim Malville and Gary Matlock.

USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-227. Fort Collins, CO: USDA

Forest Service.

Wilcox,

David R. 1999 “A Peregrine view of macroregional systems in the North American

Southwest,” Pp. 115-142 in Jill E. Neitzel (ed.) Great

Towns and Regional Polities in the

Prehistoric Southwest and Southeast. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Wills,

W. H. and Robert D. Leonard, eds. 1994. The Ancient Southwestern

Community:

Models and Methods for the Study of Prehistoric Social Organization. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Wilkinson,

David 1991 "Cores, peripheries and civilizations" Pp. 113-166 in C.

Chase- Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.) Core/Periphery Relations in Precapitalist

Worlds Boulder,CO.: Westview.

Wissler,

Clark. 1927. "The Culture Area Concept in

Social Anthropology." American Journal of Sociology

32:6(May):881-891.

Wright,

Henry T. 2000 “Agent-based modeling of small-scale societies: state of the art

and future prospects.” Pp. 373-386 in Kohler and Gumerman.