World-Systems

Theorizing

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Sociology

University of California-Riverside

Riverside, CA. 92521-0419 USA

chriscd@.ucr.edu

2001 "World-Systems Theorizing" in

Jonathan Turner (ed.) Handbook of Sociological Theory. New York: Plenum.

The intellectual history

of world-systems theorizing has roots in classical sociology, Marxian

revolutionary theory, geopolitical strategizing and theories of social

evolution. But in explicit form the world-systems perspective emerged only in

the 1970’s when Samir Amin, Andre Gunder Frank and Immanuel Wallerstein began

to formulate the concepts and to narrate the analytic history of the modern

world-system. Especially for Wallerstein,

it was explicitly a perspective rather than a theory or a set of theories. A

terminology was deployed to tell the story. The guiding ideas were explicitly not

a set of precisely defined concepts being used to formulate theoretical

explanations. Universalistic

theoretical explanations were rejected and the historicity of all social

science was embraced.[1]

Indeed, Wallerstein radically collapsed the metatheoretical opposites of

nomothetic ahistoricism/ideographic historicism into the contradictory unity of

“historical systems.” Efforts to formalize

a theory or theories out of the resulting analytic narratives are only

confounded if they assume that the changing meanings of “concepts” are

unintentional.[2] Rather there

has been sensitivity to context and difference that has abjured specifying definitions

and formalizing propositions.

And yet it has been possible to adopt a more nomothetic

and systemic stance, and then to proceed with world-systems theorizing with the

understanding that this is a principled difference from more historicist world-systems

scholars. Indeed world-systems scholars, as with other macrosociologists, may

be arrayed along a continuum from purely nomothetic ahistoricism to completely

descriptive idiographic historicism.

The possible metatheoretical stances are not two, but many, depending on

the extent to which different institutional realms are thought to be law-like

or contingent and conjunctural. Fernand

Braudel was more historicist than Wallerstein. Amin, an economist, is more nomothetic. Giovanni Arrighi’s (1994) monumental work on

600 years of “systemic cycles of accumulation” sees qualitative differences in

each hegemony, while Wallerstein, despite his aversion to explicating models,

sees rather more continuity in the logic of the system, even extending to the

most recent era of globalization.

Gunder Frank (Frank and Gills 1993) now claims that there was no

transition to capitalism, and that the logic of “capital imperialism” has not

changed since the emergence of cities and states in Mesopotamia 5000 years

ago. Metatheory comes before theory. It

focuses our theoretical spotlight on some questions while leaving others in the

shadows. No overview of world-systems

theorizing can ignore the issue of metatheoretical stances on the problem of

systemness.

In this chapter I will provide an

intentionally inclusive characterization of the late 20th century

cultural artifact that is designated by the words “world-systems/world systems

scholarship” (with and without the hyphen).

Some reflections on the intellectual ancestors of this artifact are

included in the discussion below. An earlier overview of the several heritages

that provoked world-systems theorizing is to be found in Chase-Dunn (1998,

Introduction). I will also outline my own view as to where world-systems theorizing

ought to be going. In his instructions to the chapter authors of this Handbook

of Sociological Theory Jonathan Turner (1999) said “…I am less interested in summaries of a

theoretical orientation, per se, than in what you are doing

theoretically in this area”. Thus the

theoretical research program I have been constructing with Tom Hall (Chase-Dunn

and Hall 1997) and my foray into praxis with Terry Boswell (Boswell and

Chase-Dunn 2000) will loom large in what follows.

What

It Is

The hyphen emphasizes the idea of the whole system, the

point being that all the human interaction networks small and large, from the

household to global trade, constitute the world-system. It is not just a matter

of “international relations.” This

converts the “internal-external” problem of the causes of social change into an

empirical question. The world-systems perspective emphatically does not deny

the possibility of agency because everything is alleged to be determined by the

global system. What it does is to make it possible to understand where agency

is more likely to be successful, and where not. This said, the hyphen has also come to connote a degree of

loyalty to Wallerstein’s approach.

Other versions often drop the hyphen. Hyphen or not, the world(-)systems

approach has long been far more internally differentiated than most of its

critics have understood.

The

world-systems approach looks at human institutions over long periods of time

and employs the spatial scale that is necessary for comprehending whole

interaction systems. It is neither

Eurocentric nor core-centric, at least in principle. The main idea is simple: human beings on Earth have been

interacting with one another in important ways over broad expanses of space

since the emergence of ocean-going transportation in the fifteenth

century. Before the incorporation of

the Americas into the Afroeurasian system there were many local and regional

world-systems (intersocietal networks).

Most of these were inserted into the expanding European-centered system

largely by force, and their populations were mobilized to supply labor for a

colonial economy that was repeatedly reorganized according to the changing

geopolitical and economic forces emanating from the European and (later) North

American core societies.

This

whole process can be understood structurally as a stratification system

composed of economically and politically dominant core societies (themselves in

competition with one another) and dependent peripheral and semiperipheral

regions, some of which have been successful in improving their positions in the

larger core/periphery hierarchy, while most have simply maintained their

relative positions.

This structural perspective on world history allows us to

analyze the cyclical features of social change and the long-term trends of

development in historical and comparative perspective. We can see the

development of the modern world-system as driven primarily by capitalist

accumulation and geopolitics in which businesses and states compete with one

another for power and wealth.

Competition among states and capitals is conditioned by the dynamics of

struggle among classes and by the resistance of peripheral and semiperipheral

peoples to domination from the core. In

the modern world-system the semiperiphery is composed of large and powerful

countries in the Third World (e.g. Mexico, India, Brazil, China) as well as

smaller countries that have intermediate levels of economic development (e.g.

the East Asian NICs). It is not possible to understand the history of social

change in the system as a whole without taking into account both the strategies

of the winners and the strategies and organizational actions of those who have

resisted domination and exploitation.

It is also difficult to understand why and where innovative

social change emerges without a conceptualization of the world-system as a

whole. As with earlier regional intersocietal systems, new organizational forms

that transform institutions and that lead to upward mobility most often emerge

from societies in semiperipheral locations.

Thus all the countries that became hegemonic core states in the modern

system had formerly been semiperipheral (the Dutch, the British, and the United

States). This is a continuation of a long term pattern of social evolution that

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) call “semiperipheral development.” Semiperipheral marcher states and

semiperipheral capitalist city-states had acted as the main agents of empire

formation and commercialization for millennia. This phenomenon arguably also

includes the semiperipheral communist states as well as future organizational

innovations in semiperipheral countries that will transform the now-global

system.

This

approach requires that we think structurally. We must be able to abstract from

the particularities of the game of musical chairs that constitutes uneven

development in the system to see the structural continuities. The core/periphery hierarchy remains, though

some countries have moved up or down.

The interstate system remains, though the internationalization of

capital has further constrained the abilities of states to structure national

economies. States have always been

subjected to larger geopolitical and economic forces in the world-system, and as

is still the case, some have been more successful at exploiting opportunities

and protecting themselves from liabilities than others.

In this perspective many of the phenomena that

have been called “globalization” correspond to recently expanded international

trade, financial flows and foreign investment by transnational corporations and

banks. The globalization discourse generally assumes that until recently there

were separate national societies and economies, and that these have now been

superseded by an expansion of international integration driven by information

and transportation technologies. Rather

than a wholly unique and new phenomenon, globalization is primarily

international economic integration, and as such it is a feature of the

world-system that has been oscillating as well as increasing for centuries.

Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer (2000) have shown that trade globalization is

both a cycle and a trend.

The

Great Chartered Companies of the seventeenth century were already playing an

important role in shaping the development of world regions. Certainly the

transnational corporations of the present are much more important players, but

the point is that “foreign investment’ is not an institution that only became

important since 1970 (nor since World War II).

Giovanni Arrighi (1994) has shown that finance capital has been a

central component of the commanding heights of the world-system since the

fourteenth century. The current floods

and ebbs of world money are typical of the late phase of very long “systemic

cycles of accumulation.”

An inclusive bounding of the circle of world(-)system

scholarship should include all those who see the global system of the late 20th

century as having important systemic continuities with the nearly-global system

of the 19th century. While

this is a large and interdisciplinary group, the temporal depth criterion

excludes a large number of students of globalization who see such radical

recent discontinuities that they need know nothing about what happened before

1960.

A second criterion that might be invoked to draw a

boundary around

world(-)systems

scholarship is a concern for analyzing international stratification, what some

world-systemists call the core/periphery hierarchy. Certainly this was a primary focus for Wallerstein, Amin and the

classical Gunder Frank. These

progenitors were themselves influenced by the Latin American dependency school

and by the Third Worldism of Monthly Review Marxism. Wallerstein was an

Africanist when he discovered Fernand Braudel and Marion Malowist and the

earlier dependent development of Eastern Europe. The epiphany that Latin America and Africa were like Eastern

Europe – that they had all been peripheralized by core exploitation and

domination over a period of centuries -- mushroomed into the idea of the whole

stratified system.

It

is possible to have good temporal depth but still to ignore the periphery and

the dynamics of global inequalities.

The important theoretical and empirical work of political scientists

George Modelski and William R. Thompson (1994) is an example. Modelski and

Thompson theorize a “power cycle” in which “system leaders” rise and fall since

the Portuguese led European expansion in the 15th century. They also

study the important phenomenon of “new lead industries” and the way in which

the Kondratieff Wave, a 40 to 60 year business cycle, is regularly related to

the rise and decline of “system leaders.” Modelski and Thompson largely ignore

core/periphery relations to concentrate on the “great powers.” But so does

Giovanni Arrigui’s(1994) masterful 600 year

examination of “systemic cycles of accumulation.”[3] Gunder Frank’s (1999) latest reinvention, an

examination of Chinese centrality in the Afroeurasian world system and the

abrupt rise of European power around 1800, also largely ignores core/periphery

dynamics.

So

too does the “world polity school” led by sociologist John W. Meyer. This

institutionalist approach adds a valuable sensitivity to the civilizational

assumptions of Western Christendom and their diffusion from the core to the

periphery. But rather than a dynamic struggle with authentic resistance from

the periphery and the semiperiphery, the world polity school stresses how the

discourses of resistance, national self-determination and individual liberties

are constructed out of the assumptions of the European Enlightenment.

I contend that leaving out the core/periphery

dimension or treating the periphery as inert are grave mistakes, not only for

reasons of completeness, but because the dynamics of all hierarchical

world-systems involve a process of semiperipheral development in which a few

societies “in the middle” innovate and implement new technologies of power that

drive the processes of expansion and transformation. But I would not exclude scholars from the circle because of this

mistake. Much is to be learned from those who focus primarily on the core.

It is often assumed that world-systems must necessarily

be of large geographical scale. But systemness means that groups are tightly

wound, so that an event in one place has important consequences for people in

another place. By that criterion, intersocietal systems have only become global

(Earth-wide) with the emergence of intercontinental sea faring. Earlier

world-systems were smaller regional affairs. An important determinant of system

size is the kind of transportation and communications technologies that are

available. At the very small extreme we have intergroup networks of sedentary

foragers who primarily used “backpacking” to transport goods. This kind of

hauling produces rather local networks.

Such small systems still existed until the 19th century in

some regions of North America, and Australia (e.g. Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998).

But they were similar in many respects with small world-systems all over the

Earth before the emergence of states.

An important theoretical task is to specify how to bound the spatial

scale of human interaction networks.

Working this out makes it possible to compare small, medium-sized and

large world-systems, and to use world-systems concepts to rethink theories of

human social evolution on a millennial time scale.

Anthropologists and archaeologists have been doing just

that. Kasja Ekholm and Jonathan Friedman (1982) have pioneered what they have

called “global anthropology,” by which they mean regional intersocietal systems

that expanded to become the Earth-wide system of today. Archaeologists studying

the U.S. Southwest, provoked by the theorizing and excavations of Charles

DiPeso, began using world-systems concepts to understand regional relations and

interactions with Mesoamerica. It was archaeologist Phil Kohl (1987) who first

applied and critiqued the idea of core/periphery relations in ancient Western

Asia and Mesopotamia. Guillermo Algaze’s The Uruk World System (1993) is

a major contribution as is Gil Stein’s (1999) careful examination of the

relationship between his village on the upper Tigris and the powerful Uruk core

state. Stein develops important new concepts for understanding core/periphery

relations.[4]

Research and theoretical debates among Mesoamericanists has also mushroomed.

And Peter Peregrine’s (1992,1995) innovative interpretation of the

Mississippian world-system as a Friedmanesque prestige goods system has cajoled

and provoked the defenders of local turf to reconsider the possibilities of

larger scale interaction networks in the territory that eventually became the

United States of America (e.g. Neitzel

1999).[5]

The Comparative World-Systems Perspective

Tom Hall and I have entered the fray by formulating a

theoretical research program based on a reconceptualization of the

world-systems perspective for the purposes of comparing the contemporary global

system with earlier regional intersocietal systems (Chase-Dunn and Hall

1997). We contend that world-systems,

not single societies, have always been the relevant units in which processes of

structural reproduction and transformation have occurred, and we have

formulated a single model for explaining the changing scale and nature of

world-systems over the past twelve thousand years.[6]

Institutional

Materialism

Due in part to its multidisciplinary sources of

inspiration our formulation bridges many disciplinary chasms. The term we now

use for our general approach is “institutional materialism.” We see human social evolution as produced by

an interaction among demographic, ecological and economic forces and

constraints that is expanded and modified by the institutional inventions that

people devise to solve problems and to overcome constraints. Solving problems at one level usually leads

to the emergence of new problems, and so the basic constraints are never really

overcome, at least so far. This is what allows us to construct a single basic

model that represents the major forces that have shaped social evolution over

the last twelve millennia.

This

perspective is obviously indebted to the “cultural materialism” of Marvin

Harris and its elaboration by Robert Cohen, Robert Carneiro and Stephen

Sanderson. Our approach to conceptualizing and mapping world-systems is greatly

indebted to David Wilkinson, though we have changed both his terminology and

his meaning to some extent (See Chapters 1-3 in Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997).

It

is the whole package that is new, not its parts. We contend that world-systems

have evolved because of the basic demographic, ecological and economic forces

emphasized by cultural materialism, but we do not thereby adopt the formalist

and rational choice individual psychology that is bundled with the cultural

materialism of Harris and Sanderson.

Our approach is more institutional because we contend that there have

been qualitatively different logics of accumulation (kin-based, tributary and

capitalist) and that these have transformed the nature of the social self and

personality, as well as forms of calculation and rationality. We remain

partisans of Polanyi’s (1977) substantive approach to the embeddedness of

economies in cultures. This does not

mean that we subscribe to the idea that rationality was an invention of the modern

world. We agree with Harris and Sanderson and many anthropologists that people

in all societies are economic maximizers for themselves and their families, at

least in a general sense. But it is also important to note the differences in

the cultural constructions of personality, especially as between egalitarian

and hierarchical societies. Here we follow the general line explicated by

Jonathan Friedman (1994).

Semiperipheral

Development

We

also add the important hypothesis of semiperipheral development – that

semiperipheral regions are fertile locations for the emergence of new

innovations and transformational actors. This is the main basis of our claim

that world-systems are the most important unit of analysis for explaining

social evolution.

As

we have said above, the units of analysis in which our model is alleged to

operate are world-systems. These are defined as networks of interaction that

have important, regularized consequences for reproducing and changing local

social structures.[7] By this

definition many small-scale regional world-systems have merged or been

incorporated over the last twelve thousand years into a single global system.

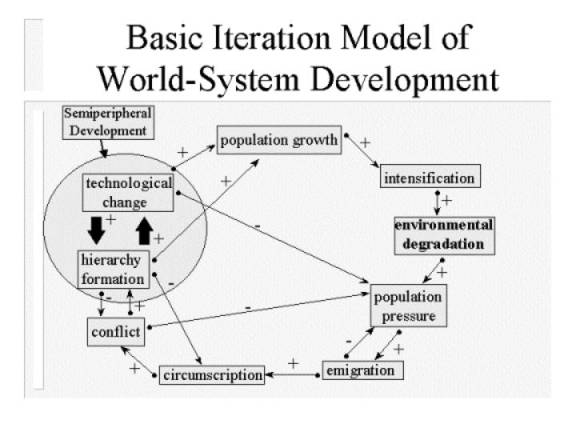

The Iteration Model

Our basic explanatory model shows what we

think are the main sources of causation in the development of more hierarchical

and complex social structures, as well as technological changes in the

processes of production. We call our schema an “iteration model” because the

variables both cause and are caused by the main processes. It is a positive

feedback model in which systemic expansion, hierarchy formation and

technological development are explained as consequences of population pressure,

and in turn they cause population growth, and so the sequence of causes goes

around again.[8] We use the term “iteration” because the

positive feedback feature repeats the same processes over and over on an

expanding spatial scale. Figure 1 illustrates the variables and our hypotheses

about the causal relations among them. Positive arrows signify that a variable

increases another variable. Negative arrows indicate that a variable decreases

another variable. Thicker arrows

indicate stronger effects.

Figure 1: Basic Iteration Model

The

model is not alleged to characterize what has happened in all world-systems. Many

have gotten stuck at one level of hierarchy formation or technological

development. Our model accounts for

instances in which hierarchy formation and technological development occurred.

There were many systems in which these outcomes did not occur. Our claim is not that every system evolved

in the same way. Rather we hold that those systems in which greater complexity

and hierarchy and new technologies did emerge went through the processes

described in our model.

At

the top of Figure 1 is Population Growth.

We realize that procreation is socially regulated in all societies, but we

contend, following Marvin Harris, that restricting population growth,

especially by premodern methods, was always costly, and so the moral order

tended to let up when conditions temporarily improved. This led to a long-run

tendency for population to grow. Population Growth leads to Intensification, defined by Marvin

Harris (1977:5) as “the investment of more soil, water, minerals, or energy per

unit of time or area.” Intensification

of production leads to Environmental

Degradation as the raw material inputs become scarcer and the unwanted

byproducts of human activity modify the environment. Together Intensification

and Environmental Degradation lead

to rising costs of producing the food and raw materials that people need, and

this condition is called Population

Pressure. In order to feed more

people, hunters must travel farther because the game nearest to home becomes

exhausted. Thus the cost in time and effort of bringing home a given amount of

food increases. Some resources are less subject to depletion than others (e.g.

fish compared to big game), but increased use usually causes eventual rising

costs. Other types of environmental degradation are due to the side effects of

production, such as the build-up of wastes and pollution of water sources.

These also increase the costs of continued production or cause other problems.

As long as there were available lands to

occupy, the consequences of population pressure led to Migration. And so humans populated the whole Earth. The costs of Migration are a function of the

availability of desirable alternative locations and the effective resistance to

immigration that is mounted by those who already live in these locations.

Circumscription (Carneiro 1970) occurs when the costs of leaving are higher than the costs of

staying. This is a function of available lands, but lands are differentially

desirable depending on the technologies that the migrants employ. Generally

people have preferred to live in the way that they have lived in the past, but Population Pressure or other push

factors can cause them to adopt new technologies in order to occupy new lands.

The factor of resistance from extant occupants is also a complex matter of

similarities and differences in technology, social organization and military

techniques between the occupants and the groups seeking to immigrate. When the

incoming group knows a technique of production that can increase the

productivity of the land (such as horticulture) they may be able to peacefully

convince the existing occupants to coexist for a share of the expanded product

(Renfrew 1987).[9] Circumscription

increases the likelihood of higher levels of Conflict in a situation of Population

Pressure because, though the costs of staying are great, the exit option is

closed off. This can lead to several

different kinds of warfare, but also to increasing intrasocietal struggles and

conflicts (civil war, class antagonisms, clan war, etc.) A period of intense conflict tends to reduce

Population Pressure if significant

numbers of people are killed off. And some systems get stuck in a vicious cycle

in which warfare and other forms of conflict operate as the demographic

regulator, e.g. the Marquesas Islands (Kirch 1991). This cycle corresponds to

the path that goes from Population

Pressure to Migration to Circumscription to Conflict, and then a negative arrow back to Population Pressure. When population again builds up the circle

goes around again.

Under

the right conditions a circumscribed situation in which the level of conflict

has been high will be the locus of the emergence of more hierarchical

institutions. Carneiro (1970) and Mann (1986) contend that people will tend to

run away from hierarchy if they can in order to maintain autonomy and equality.

But circumscription raises the costs of exit, and exhaustion from prolonged or

extreme conflict may make a new level of hierarchy the least bad alternative.

It is often better to accept a king than to continue fighting. And so kings

(and big men, chiefs and emperors) emerged out of situations in which conflict

has reduced the resistance to centralized power. This is quite different from

the usual portrayal of those who hold to the functional theory of

stratification. The world-system

insight here is that the newly emergent elites often come from regions that

have been semiperipheral.

Semiperipheral

actors are unusually able to put together effective campaigns for erecting new

levels of hierarchy. This may involve both innovations in the “techniques of

power” and innovations in productive technology (Technological Change). Newly emergent elites often implement new

production technologies as well as new waves of intensification. This, along

with the more peaceful regulation of access to resources organized by the new

elites, creates the conditions for a new round of Population Growth, which brings us around to the top of Figure 1

again.

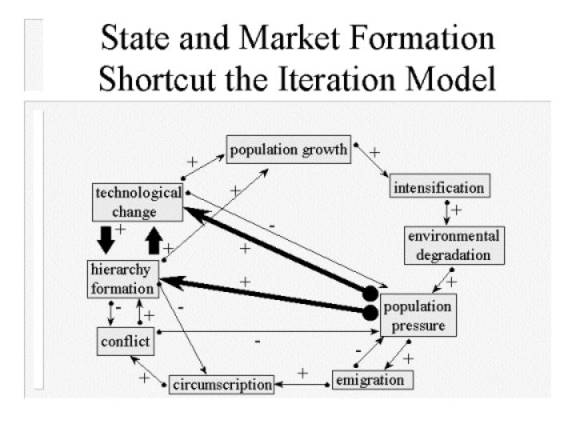

Short-cutting: How

Institutional Inventions Modified the

Iteration Model

We also contend that the institutional

inventions made and spread by semiperipheral actors qualitatively transform the

logic of accumulation and alter the operation of the variables in the iteration

model. But these qualitative changes are themselves the consequence of people

trying to solve the basic problems produced by the forces and constraints

contained in the model. The model displayed in Figure 1 best explains the

independent rise of complex chiefdoms, class distinctions and states in at

least four different regional world-systems. But these institutional

adaptations modified to some extent the operation of the variables in the

model. And likewise the long rise of commercialization and capitalism again

modified the operation of the processes and added new causal arrows to the

basic model.

Figure 2:

Temporary Institutional Short Cuts in the Iteration Model

Figure

2 illustrates in a general way what we think happened with the emergence of new

modes of accumulation, especially states and capitalism. The new modes allowed some of the effects of

Population Pressure to more directly

cause changes in hierarchies and technologies of production, thus short-cutting

the path that leads through Migration,

Circumscription and Conflict. How can the emergence of

states allow Population Pressure to

more directly affect Hierarchy Formation

and Technological Change? Once there are already states within a

region the phenomenon of secondary state formation occurs. Population pressure

in outlying semiperipheral areas combines with the threats and opportunities

presented by interaction with the existing states to promote the formation of

new states. This is the main way in which state formation short cuts the

processes at the bottom of Figure 2.

We

do not mean to say that conflict disappears, but rather that it does not need

to reach the same levels of intensity in order to provoke the formation of new

states once states are already present in a region.

State

formation also articulates the rising costs due to intensification with changes

in technology. The specialized organizations that states create (bureaucracies

and armies) sometimes use their powers and organizational capabilities to

invent new kinds of productive efficiency and to implement new kinds of

production. Governing elites sometimes mobilize resources and labor for

irrigation projects, clearing new land for agriculture, developing

transportation facilities and so forth. The portrayal of the early states and

agrarian empires as technologically moribund is due mainly to comparing them

with the much more powerful tendency of capitalist societies to revolutionize

technology. But compared to earlier, less hierarchical, systems the tributary

empires increased the rate of technological innovations and implemented them

across vast areas.

The

emergence of market mechanisms and capitalism also articulated the forces

produced by population pressure with new forms of hierarchy formation and

technological change. Obviously markets provide incentives to economize and to

develop cheaper substitutes for depleted resources that are becoming more

expensive because of intensification.

But markets and capitalism also alter the way in which hierarchy

formation occurs. Once capitalist

accumulation has become predominant in a system of regional core states the

sequence of the rise and fall of core-wide empires is replaced by the rise and

fall of hegemonic core powers in which hegemonic power is based as much on

comparative advantage in the production of core commodities as on superior

military capabilities. Capitalist

hegemons more directly respond to the changing economic and political forces

produced by ecological degradation and population pressure than tributary

empires did. Again, conflict is not eliminated, but the intensity of conflict

that is necessary to produce new levels of hierarchy formation is reduced.

Competition comes to be based less on military factors and more on economic

ones. Many now believe that this trend

has gone so far that future hegemonic rivalry will not involve military

conflict. Though we must all hope that this is true, there are good reasons to

be somewhat skeptical (see Chase-Dunn and Podobnik 1995). Another round of world war among core states might well

prove to be fatal for the human species. But it might also lead to the

formation of a global state that would outlaw warfare, as in the future

scenario painted by Warren Wagar (1992).

Our main point here is that capitalism transmits population pressure to

the hierarchy formation process, creating incentives for the emergence of

global governance.

The

industrial capitalism of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries has also

altered the operation of population pressure by producing the “demographic

transition” in core countries. Marvin

Harris (1977) contends that this has been the consequence of the concurrence

and interaction of three forces – the fuel revolution, the job revolution and

the contraception revolution. The

demographic transition means a decrease in mortality due to better public

health measures and rising wages, and then a decrease in fertility and family

size. These changes lower population

pressure in the core countries and, if they were replicable on a world scale,

population pressure might cease to be such a driving force of social change.

But Harris argues that the demographic transition in the core states since the

latter quarter of the nineteenth century was due to conditions that will be

difficult or impossible to replicate on a world scale.

Harris

contends that average wages in the core did not rise above subsistence until

the last quarter of the nineteenth century but other studies of wages show that

returns to labor rise and fall cyclically with long economic cycles such as the

Kondratieff wave and the long cycles of price inflation/equilibrium studied by

David Hackett Fischer (1996). Fischer

(1996:160) reports evidence of rising wages and returns to labor throughout the

nineteenth century. The demographic

transition was produce by a combination of rising wages with the invention of

inexpensive and effective methods of birth control and the shift from coal to

oil [which multiplied geometrically the

amount of energy utilized in production ].

Harris

also emphasizes that these concurrent and interactive “revolutions” were

probably a unique and time-bound phenomenon rather than the early stages of a

global transcendence of population pressure. The non-renewable character of

oil-based energy and the ecological impossibility extending the contemporary

American level of resource utilization to the vast populations of Asia add up

to what Peter Taylor (1996) has called “global impasse.” The model of development to which the global

majority has been encouraged to aspire is an ecological impossibility for all

to attain. If the Chinese eat the same

number of eggs and drive the same number of cars per capita as the United

Statesians do the biosphere will collapse. The best expert projection of proven

oil reserves with current techniques and current consumption levels is around

fifty years. That is not much time in the perspective of human social

evolution.

All this is to say that the current system has probably not permanently transcended the nasty bottom part of the iteration model. As did states, capitalism has allowed the number of people on Earth to increase greatly. It has also produced the tantalizing possibility of a new system in which population pressure has been brought under control. But the failure to extend the demographic transition to the peripheral countries, or rather to reduce fertility after reducing mortality, has resulted in population pressure on a scale greater than ever before. Under such circumstances a return to some new version of the nasty route would seem to be likely.

Is

our revised iteration model testable? In principle it is, but not with existing

data sets. The Human Relations Area File might be a good place to start, but

its unit of analysis is the society, not world-systems, and the characteristics

of the societies are conceptualize as synchronic, whereas we would need to

study processes of change over long periods of time. What is needed for formal comparative cross-world-systems

research is a “representative sample” of each of the major types of

world-systems.

In Rise

and Demise (Chase-Dunn and Hall

1997) we have begun to study bounded world-systems over long time periods, but

the numbers of cases remain small. This problem can be overcome by doing time

series analyses on individual world-systems, and this is the research design

that holds the most immediate promise for being able to evaluate the causal

propositions contained in our model. Time series analysis using structural

equations models could disentangle the

kind of reciprocal causation we hypothesize in our iteration models. It would also be desirable to study as many

separate systems as possible in order to see if the causal structures hold

across different systems.

Modeling the Modern System

My

Global Formation (1998) is an

effort to make a single model of the constants, cycles and trends of the modern

world-system and to work out major conceptual issues and arguments regarding

the “necessity of imperialism.” This

model of the structural constants, cycles and secular trends specifies the basic and normal operations of

the system. I argue elsewhere that this basic scheme continues to accurately

describe the system in the current period of global capitalism and the

“information age” (Chase-Dunn 1998).

Schema

of world-system constants, cycles and trends

The structural constants are:

1. Capitalism -- the accumulation of resources by

means of the production and sale of commodities for profit;

2. The interstate system -- a system of unequally

powerful sovereign national states that compete for resources by supporting

profitable commodity production and by engaging in geopolitical and military

competition;

3. The core/periphery hierarchy -- in which core

regions have strong states and specialize in high-technology, high-wage

production while peripheral regions have weak states and specialize in

labor-intensive and low-wage production.

These

structural features of the modern world-system are continuous and reproduced. I

argue that they are interlinked and interdependent with one another such that

any real change in one would necessarily alter the others in fundamental ways

(Chase-Dunn, 1998).

In

addition to these structural constants, there are two other structural features

that I see as continuities even though they involve patterned change. These are

the systemic cycles and the systemic trends. The basic systemic cycles are:

1.The Kondratieff Wave (K-wave) -- a worldwide

economic cycle with a period of from forty to sixty years in which the relative

rate of economic activity increases (during "A-phase" upswings) and

then decreases (during "B-phase" periods of slower growth or

stagnation).

2. The hegemonic sequence -- the rise and fall of

hegemonic core powers in which military power and economic comparative

advantage are concentrated into a single hegemonic core state during some

periods and these are followed by periods in which wealth and power are more

evenly distributed among core states. Examples of hegemons are the Dutch in the

seventeenth century, the British in the nineteenth century and the United States

in the twentieth century.

3. The cycle of core war severity -- the severity

(battle deaths per year) of wars among core states (world wars) displays a

cyclical pattern that has closely tracked the K-wave since the sixteenth

century (Goldstein, 1988).

4. The oscillation between market trade versus more politically structured

interaction between core states and peripheral areas. This is related to cycles

of colonial expansion and decolonization and is manifesting itself in the

current period in the form of emergent regional trading blocs that include both

developed and less-developed countries.

The

systemic trends that are normal operating procedure in the modern world-system

are:

1. Expansion and deepening of commodity relations

-- land, labor and wealth have been increasingly mediated by market-like

institutions in both the core and the periphery.

2. State-formation -- the power of states over

their populations has increased everywhere, though this trend is sometimes

slowed down by efforts to deregulate. State regulation has grown secularly

while political battles rage over the nature and objects of regulation.

3. Increased size of economic enterprises -- while

a large competitive sector of small firms is reproduced, the largest firms (those occupying what is called the monopoly

sector) have continuously grown in size. This remains true even in the most

recent period despite its characterization by some analysts as a new

"accumulation regime" of "flexible specialization" in which

small firms compete for shares of the global market.

4. International economic integration – the growth

of trade interconnectedness and the transnationalization of capital. Capital

has crossed state boundaries for millennia but the proportion of all production

that is due to the operation of transnational firms has increased in every

epoch. The contemporary focus on transnational sourcing and the single

interdependent global economy is the heightened awareness produced by a trend

long in operation.

5. Increasing capital-intensity of production and

mechanization (in several industrial

revolutions since the sixteenth century) has increased the productivity of

labor in agriculture, industry and services.

6. Proletarianization -- the world work force has

increasingly depended on labor markets for meeting its basic needs. This

long-term trend may be temporarily slowed or even reversed in some areas during

periods of economic stagnation, but the secular shift away from subsistence

production has a long history that continues in the most recent period. The

expansion of the informal sector is part of this trend despite its functional

similarities with earlier rural subsistence redoubts.

7.

The growing gap --

despite exceptional cases of successful upward mobility in the

core/periphery hierarchy (e.g. the United States,

Japan, Korea, Taiwan) the relative gap in incomes between core and peripheral

regions has continued to increase, and this trend has existed since at least

the end of the nineteenth century, and probably before.

8.

International political integration – the emergence of stronger

international

institutions for regulating economic and political

interactions. This is a trend since the rise of the Concert of Europe after the

defeat of Napoleon. The League of Nations, the United Nations and such

international financial institutions as the World Bank and the International

Monetary Fund show an upward trend toward increasing global governance.

The comparative world-systems perspective developed by

Chase-Dunn and Hall does not require the reformulation of this schema of

structural constants, cycles and trends. The very long-term perspective does reveal

that many of the dynamic processes that operate in the modern world-system are

analogous to patterns that can be seen in earlier systems. Kondratieff waves

(forty to sixty year business cycles composed of A-phases of expansion and

B-phases of stagnation) probably existed in tenth century China. The hegemonic

sequence (rise and fall of hegemonic core powers) is the particular manifestation

in the modern system of a general sequence of centralization and

decentralization of power that is characteristic of all hierarchical

world-systems. In all world-systems

small and large, culturally different groups trade, fight and make alliances

with one another in ways that importantly condition processes of social change.

The

cyclical trend of economic globalization (international economic integration)

needs to be understood in the context of the other cycles and trends specified

in the schema above. The trends and cycles reveal important continuities and

imply that future struggles for economic justice and democracy need to base

themselves on an analysis of how earlier struggles changed the scale and nature

of development in the world-system. This raises the question of the relevance

of these theoretical approaches for possible human futures.

Where

Is It Going?

The term globalization has been used to refer to “the

globalization project” – the abandoning of Keynesian models of national

development and a new emphasis on deregulation and opening national commodity

and financial markets to foreign trade and investment (McMichael 1996). This is to point to the ideological aspects

of the recent wave of international economic integration. The term I prefer for

this turn in global discourse is “neo-liberalism.” The worldwide decline of the political left may have predated the

revolutions of 1989 and the demise of the Soviet Union, but it was certainly

also accelerated by these events. The

structural basis of the rise of the globalization project is the new level of

integration reached by the global capitalist class. The internationalization of

capital has long been an important part of the trend toward economic

globalization. And there have been many claims to represent the general

interests of business before. Indeed every modern hegemon has made this claim.

But the real integration of interests of the capitalists in each of the core

states has probably reached a level greater than ever before.

This

is the part of the model of a global stage of capitalism that must be taken

most seriously, though it can certainly be overdone. The world-system has now reached a point at which both the old

interstate system based on separate national capitalist classes, and new

institutions representing the global interests of capitalists exist and are

powerful simultaneously. In this light

each country can be seen to have an important ruling class fraction that is

allied with the transnational capitalist class.

Neo-liberalism began as the Reagan-Thatcher attack on the

welfare state and labor unions. It

evolved into the Structural Adjustment Policies of the International Monetary

Fund and the triumphalism of the ideologues of corporate globalization after

the demise of the Soviet Union. In

United States foreign policy it has found expression in a new emphasis on

“democracy promotion” in the periphery and semiperiphery. Rather than propping up military

dictatorships in Latin America, the emphasis has shifted toward coordinated

action between the C.I.A and the U.S. National Endowment for Democracy to

promote electoral institutions in Latin America and other semiperipheral and

peripheral regions (Robinson 1996).

Robinson points out that the kind of “low intensity democracy” that is

promoted is really best understood as “polyarchy,”

a regime form in which elites orchestrate a process of electoral competition

and governance that legitimates state power and undercuts more radical

political alternatives that might threaten the ability of national elites to

maintain their wealth and power by exploiting workers and peasants. Robinson

(1996) convincingly argues that polyarchy and democracy-promotion are the

political forms that are most congruent with a globalized and neo-liberal world

economy in which capital is given free reign to generate accumulation wherever

profits are greatest.

The spiral of capitalism and socialism

The interaction between expansive commodification

and resistance movements can be denoted as “the spiral of capitalism and

socialism.” The world-systems perspective provides a view of the long-term

interaction between the expansion and deepening of capitalism and the efforts

of people to protect themselves from exploitation and domination. The

historical development of the communist states is explained as part of a

long-run spiraling interaction between expanding capitalism and socialist

counter-responses. The Russian and Chinese revolutions were socialist movements

in the semiperiphery that attempted to transform the basic logic of capitalism,

but which ended up using socialist ideology to mobilize industrialization for

the purpose of catching up with core capitalism.

The

spiraling interaction between capitalist development and socialist movements is

revealed in the history of labor movements, socialist parties and communist

states over the last 200 years. This long-run comparative perspective enables

one to see recent events in China, Russia and Eastern Europe in a framework

that has implications for future efforts to institutionalize democratic

socialism. The metaphor of the spiral

means this: both capitalism and socialism affect one another's growth and

organizational forms. Capitalism spurs socialist responses by exploiting and

dominating peoples, and socialism spurs capitalism to expand its scale of

production and market integration and to revolutionize technology.

Defined

broadly, socialist movements are those political and organizational means by

which people try to protect themselves from market forces, exploitation and

domination, and to build more cooperative institutions.[10]

The several industrial revolutions, by which capitalism has restructured

production and reorganized labor, have stimulated a series of political

organizations and institutions created by workers and communities to protect

their livelihoods and resources. This happened differently under different

political and economic conditions in different parts of the world-system.

Skilled workers created guilds and craft unions. Less skilled workers created

industrial unions. Sometimes these coalesced into labor parties that played

important roles in supporting the development of political democracies, mass

education and welfare states (Rueschemeyer, Stephens and Stephens 1992). In

other regions workers and peasants were less politically successful, but

managed at least to protect access to rural areas or subsistence plots for a

fallback or hedge against the insecurities of employment in capitalist

enterprises. To some extent the burgeoning contemporary "informal

sector" in both core and peripheral societies provides such a fallback.

The

mixed success of workers’ organizations also had an impact on the further

development of capitalism. In some areas workers and/or communities were

successful at raising the wage bill or protecting the environment in ways that

raised the costs of production for capital. When this happened capitalists

either displaced workers by automating them out of jobs or capital migrated to

where fewer constraints allowed cheaper production. The process of capital

flight is not a new feature of the world-system. It has been an important force

behind the uneven development of capitalism and the spreading scale of market

integration for centuries. Labor unions and socialist parties were able to

obtain some power in certain states, but capitalism became yet more

international. Firm size increased. International markets became more and more

important to successful capitalist competition. Fordism, the employment of

large numbers of easily-organizable workers in centralized production

locations, has been partially supplanted by "flexible

accumulation" (small firms

producing small customized products) and global sourcing (the use of substitutable

components from broadly dispersed competing producers). These new production

strategies make traditional labor organizing approaches much less viable.

Socialists were able to gain state power in

certain semiperipheral states and to

create political mechanisms of protection against competition with core

capital. This was not a wholly new phenomenon. As discussed below, capitalist

semiperipheral states had done, and were doing, similar things. But, the

communist states claimed a fundamentally oppositional ideology in which

socialism was allegedly a superior system that would eventually replace

capitalism. Ideological opposition is a phenomenon that the capitalist

world-economy had seen before. The geopolitical and economic battles of the

Thirty Years War were fought in the name of Protestantism against Catholicism.

The content of the ideology may make some difference for the internal

organization of states and parties, but every contender must be able to

legitimate itself in the eyes and hearts of its cadre. The claim to represent a

qualitatively different and superior socio-economic system is not evidence that

the communist states were ever able to become structurally autonomous from

world capitalism.

The

communist states severely restricted the access of core capitalist firms to

their internal markets and raw materials, and this constraint on the mobility

of capital was an important force behind the post-World War II upsurge in the

spatial scale of market integration and a new revolution of technology. In

certain areas capitalism was driven to further revolutionize technology or to

improve living conditions for workers and peasants because of the demonstration

effect of propinquity to a communist state. U.S. support for state-led

industrialization in Japan and Korea (in contrast to U.S. policy in Latin

America) is only understandable as a geopolitical response to the Chinese

revolution. The existence of "two superpowers" -- one capitalist and

one communist -- in the period since World War II provided a fertile context

for the success of international liberalism within the "capitalist"

bloc. This was the political/military basis of the rapid growth of

transnational corporations and the latest round of "time-space

compression" made possible by radically lowered transportation and communications

costs (Harvey 1989). This technological

revolution has once again restructured the international division of labor and

created a new regime of labor regulation called "flexible

accumulation." The process by which the communist states have become

reintegrated into the capitalist world-system has been long, as described

below. But, the final phase of reintegration was provoked by the inability to

be competitive with the new form of capitalist regulation. Thus, capitalism

spurs socialism, which spurs capitalism, which spurs socialism again in a wheel

that turns and turns while getting larger.

The

economic reincorporation of the communist states into the capitalist

world-economy did not occur recently and suddenly. It began with the

mobilization toward autarchic industrialization using socialist ideology, an

effort that was quite successful in terms of standard measures of economic

development. Most of the communist states were increasing their percentage of

world product and energy consumption up until the 1980s (Boswell and Chase-Dunn

2000).

The

economic reincorporation of the communist states moved to a new stage of

integration with the world market and foreign firms in the 1970s. Andre Gunder

Frank (1980:chapter 4) documented a trend toward reintegration in which the

communist states increased their exports for sale on the world market,

increased imports from the avowedly capitalist countries, and made deals with

transnational firms for investments within their borders. The economic crisis

in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union was not much worse than the economic

crisis in the rest of the world during the global economic downturn that began

in the late 1960s (see Boswell and Peters 1990, Table 1). Data presented by

World Bank analysts indicates that GDP growth rates were positive in most of

the "historically planned economies" in Europe until 1989 or 1990

(Marer et al, 1991: Table 7a).

Put

simply, the big transformations that occurred in the Soviet Union and China

after 1989 were part of a process that had long been underway since the 1970s.

The regime changes were a matter of the political superstructure catching up

with the economic base. The democratization of these societies is, of course, a

welcome trend, but democratic political forms do not automatically lead to a

society without exploitation or domination. The outcomes of current political

struggles are rather uncertain in most of the ex-communist countries. New types

of authoritarian regimes seem at least as likely as real democratization.

As trends in the last two decades have shown, austerity

regimes, deregulation and marketization within nearly all of the communist

states occurred during the same period as similar phenomena in non-communist

states. The synchronicity and broad similarities between Reagan/Thatcher

deregulation and attacks on the welfare state, austerity socialism in most of

the rest of the world, and increasing pressures for marketization in the Soviet

Union and China are all related to the B-phase downturn of the Kondratieff

wave, as were the moves toward austerity and privatization in most

semiperipheral and peripheral states. The trend toward privatization,

deregulation and market-based solutions among parties of the Left in almost

every country is thoroughly documented by Lipset (1991). Nearly all socialists

with access to political power have abandoned the idea of doing anything more

than buffing off the rough edges of capitalism.

The way in which the pressures of a

stagnating world economy impact upon national policies certainly varies from

country to country, but the ability of any single national society to construct

collective rationality is limited by its interaction within the larger system.

The most recent expansion of capitalist integration, termed "globalization

of the economy," has made autarchic national economic planning seem

anachronistic. Yet, political reactions

against economic globalization are now under way in the form of revived

ex-communist parties and economic nationalism in both the core and the

periphery (e.g., Pat Buchanan, the Brazilian military, the Indonesian prime

minister) and a growing coalition of popular forces who are critiquing the

ideological hegemony of neo-liberalism (e.g., Ralph Nader, environmentalists,

and a resurgent labor movement that defeated the “Fast Track” legislation in

the U.S., etc.) (See Mander and Goldsmith 1997). Anti-globalization

demonstrations from Seattle to Prague have made the headlines and the glory

days of neo-liberal economics have passed even within the international financial

institutions.

Political

implications of the world-systems perspective

The

age of U.S. hegemonic decline and the rise of post-modernist philosophy have

cast the liberal ideology of the European Enlightenment (science, progress,

rationality, liberty, democracy and equality) into the dustbin of repressive

totalizing universalisms. It is alleged that these values have been the basis

of imperialism, domination and exploitation and, thus, they should be cast out

in favor of each group asserting its own set of values. It is important to note that

self-determination and a considerable dose of multiculturalism (especially

regarding religion) were already central elements in Enlightenment liberalism.

A structuralist and historical materialist

version of the world-systems approach poses this problem of values in a

different way. The problem with the

capitalist world-system has not been with its values. The philosophy of

liberalism is fine. It has quite often been an embarrassment to the pragmatics

of imperial power and has frequently provided justifications for resistance to

domination and exploitation. The

philosophy of the Enlightenment has never been by itself a major cause of

exploitation and domination. Rather, it

was the military and economic power generated by capitalism that made European

hegemony possible. Power was legitimated in the eyes of the agents and some of

the victims by recitation of the great liberal values, but it was not the

values that mainly enabled conquest and exploitation, but rather the gun ships

and the cheap prices of commodities.

To

humanize the world-system we may need to construct a new philosophy of

democratic and egalitarian liberation. Of course, many of the principle ideals

that have been the core of the Left’s critique of capitalism are shared by

non-European philosophies. Democracy,

in the sense of popular control over collective decision-making, was not

invented in ancient Greece. It was a

characteristic of all non-hierarchical human societies on every continent before

the emergence of complex chiefdoms and states.

My point is that a new egalitarian universalism can usefully incorporate

quite a lot from the old universalisms. It is not liberal ideology that caused

so much exploitation and domination. It was the failure of real capitalism to

live up to its own ideals (liberty and equality) in most of the world.

A

central question for any strategy of transformation is the question of agency.

Who are the actors who will most vigorously and effectively resist capitalism

and construct democratic socialism?

Where is the most favorable terrain, the weak link, where concerted

action could bear the most fruit? Samir

Amin (1990,1992) contends that the agents of socialism have been most heavily

concentrated in the periphery. It is there that the capitalist world‑system

is most oppressive, and thus peripheral workers and peasants, the vast majority

of the world proletariat, have the most to win and the least to lose.

On

the other hand, Marx and many contemporary Marxists have argued that socialism

will be most effectively built by the action of core proletarians. Since core

areas have already attained a high level of technological development, the

establishment of socialized production and distribution should be easiest in the

core. And, organized core workers have had the longest experience with

industrial capitalism and the most opportunity to create socialist social

relations.

I

submit that both "workerist" and "Third Worldist" positions

have important elements of truth, but there is another alternative that is

suggested by a structural and comparative theory of the world‑system: the

semiperiphery as the weak link.

Core

workers may have experience and opportunity, but a sizable segment of the core

working classes lack motivation because they have benefited from a less

confrontational relationship with core capital. The existence of a labor

aristocracy has divided the working class in the core and, in combination with

a large middle stratum, has undermined political challenges to capitalism.

Also, the "long experience" in which business unionism and social

democracy have been the outcome of a series of struggles between radical

workers and the labor aristocracy has created a residue of trade union

practices, party structures, legal and governmental institutions, and

ideological heritages which act as barriers to new socialist challenges. These conditions have changed to some extent

during the last two decades as hyper-mobile capital has attacked organized

labor, dismantled welfare states and downsized middle class work forces. These developments have created new

possibilities for popular movements within the core, and we can expect more

confrontational stances to emerge as workers devise new forms of organization

(or revitalize old forms). Economic

globalization makes labor internationalism a necessity, and so we can expect to

see the old idea take new forms and become more organizationally real. Even small victories in the core have

important effects on peripheral and semiperipheral areas because of

demonstration effects and the power of core states.

The

main problem with "Third Worldism" is not motivation, but

opportunity. Powerful external forces that either overthrow them or force them

to abandon most of their socialist program soon beset democratic socialist

movements that take state power in the periphery. Liberation movements in the

periphery have most usually been anti‑imperialist class alliances that

succeed in establishing at least the trappings of national sovereignty, but not

socialism. The low level of the development of the productive forces also makes

it harder to establish socialist forms of accumulation, although this is not

impossible in principle. It is simply harder to share power and wealth when

there are very little of either. But, the emergence of democratic regimes in

the periphery will facilitate new forms of mutual aid, cooperative development

and popular movements to challenge the current ideological hegemony of

neoliberalism.

Semiperipheral

democratic socialism

In

the semiperiphery both motivation and opportunity exist. Semiperipheral areas,

especially those in which the territorial state is large, have sufficient

resources to be able to stave off core attempts at overthrow and to provide

some protection to socialist institutions if the political conditions for their

emergence should arise. Tom Hall and I

found that semiperipheral societies have played transformational roles in many

earlier world-systems, an observation that we dub “semiperipheral development”

(Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 5).

Some semiperipheral societies have continued to be both upwardly mobile

and transformative of social relations in the modern world-system. All the

hegemonic core powers (the Dutch, the British and the United States) were

former semiperipheral countries. John Markoff (1998) shows that innovations in

democratic institutions tended to occur in semiperipheral countries in the

nineteenth century. And semiperipheral

regions (e.g., Russia and China) have experienced more militant class‑based

socialist revolutions because of their intermediate position in the

core/periphery hierarchy. While core exploitation of the periphery creates and

sustains alliances among classes in both the core and the periphery, in the

semiperiphery an intermediate world‑system position undermines class

alliances and provides a fruitful terrain for strong challenges to capitalism.

Semiperipheral revolutions and movements are not always socialist in

character, as we have seen in Iran. But, when socialist intentions are strong

there are greater possibilities for real transformation than in the core or the

periphery. Thus, the semiperiphery is the weak link in the capitalist world‑system.

It is the terrain upon which the strongest efforts to establish socialism have

been made, and this is likely to be true of the future as well.

On

the other hand, the results of the efforts so far, while they have undoubtedly

been important experiments with the logic of socialism, have left much to be desired.

The tendency for authoritarian regimes to emerge in the communist states

betrayed Marx’s idea of a freely

constituted association of direct producers. And, the imperial control of

Eastern Europe by the Russians was an insult to the idea of proletarian

internationalism. Democracy within and between nations must be a constituent

element of true socialism.

It

does not follow that efforts to build socialism in the semiperiphery will

always be so constrained and thwarted. The revolutions in the Soviet Union and

the Peoples' Republic of China have increased our collective knowledge about

how to build socialism despite their only partial successes and their obvious

failures. It is important for all of us who want to build a more humane and

peaceful world‑system to understand the lessons of socialist movements in

the semiperiphery, and the potential for future, more successful, forms of

socialism there.

Once

again the core has developed new lead industries -- computers and biotechnology

-- and much of large-scale heavy industry, the classical terrain of strong

labor movements and socialist parties, has been moved to the semiperiphery

(Silver 1995, forthcoming). This means that new socialist bids for state power

in the semiperiphery (e.g., South Africa, Brazil, Mexico, perhaps Korea) will

be much more based on an urbanized and organized proletariat in large-scale

industry than the earlier semiperipheral socialist revolutions were. This

should have happy consequences for the nature of new socialist states in the

semiperiphery because the relationship between the city and the countryside

within these countries should be less antagonistic. Less internal conflict will

make more democratic socialist regimes possible, and will lessen the likelihood

of core interference. The global expansion of communications has increased the

salience of events in the semiperiphery for audiences in the core and this may

serve to dampen core state intervention into the affairs of democratic

socialist semiperipheral states.

Some

critics of the world‑systems perspective have argued that emphasis on the

structural importance of global relations leads to political do‑nothingism

while we wait for socialism to emerge at the world level. The world‑systems

perspective does indeed encourage us to examine global constraints (and

opportunities), and to allocate our political energies in ways that will be

most productive when these structural constraints are taken into account. It

does not follow that building socialism at the local or national level is

futile, but we must expend resources

on transorganizational, transnational and international socialist relations.

The environmental, feminist and indigenous movements are now in the lead with

regard to internationalism and labor needs to follow their example.

A

simple domino theory of transformation to democratic socialism is misleading

and inadequate. Suppose that all firms or all nation‑states adopted

socialist relations internally but continued to relate to one another through

competitive commodity production and political/military conflict. Such a

hypothetical world‑system would still be dominated by the logic of

capitalism, and that logic would be likely to repenetrate the

"socialist" firms and states. This cautionary tale advises us to invest

political resources in the construction of multilevel (transorganizational,

transnational and international) socialist relations lest we simply repeat the

process of driving capitalism to once again perform an end run by operating on

a yet larger scale.

A

market socialist global democracy

These

considerations lead us to a discussion of socialist relations at the level of

the whole world‑system. The emergence of democratic collective

rationality (socialism) at the world‑system level is likely to be a slow

process. What might such a world‑system look like and how might it

emerge? It is obvious that such a

system would require a democratically controlled world federation that can

effectively adjudicate disputes among nation‑states and eliminate warfare

(Wagar 1996). This is a bare minimum. There are many other problems that badly

need to be coordinated at the global level:

ecologically sustainable development, a more balanced and egalitarian

approach to economic growth, and the lowering of population growth rates.

The

idea of global democracy is important for this struggle. The movement needs to

push toward a kind of popular democracy that goes beyond the election of

representatives to include popular participation in decision-making at every

level. Global democracy can only be real if it is composed of civil societies

and national states that are themselves truly democratic (Robinson 1996). And

global democracy is probably the best way to lower the probability of another

war among core states. For that reason it is in everyone’s interest.

How

might such a global democracy come into existence? The process of the growth of

international organizations, which has been going on for at least 200 years,

will eventually result in a world state if we are not blown up first. Even

international capitalists have some uses for global regulation, as is attested

by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Capitalists do not want

the massive economic and political upheavals that would follow the collapse of

the world monetary system, and so they support efforts to regulate

"ruinous" competition and beggar‑thy‑neighborism. Some of

these same capitalists also fear nuclear holocaust, and so they may support a

strengthened global government that can effectively adjudicate conflicts among

nation‑states.

Of

course, capitalists know as well as others that effective adjudication means

the establishment of a global monopoly of legitimate violence. The process of

state formation has a long history, and the king's army needs to be bigger than

any combination of private armies that might be brought against him. While the

idea of a world state may be a frightening specter to some, I am optimistic

about it for several reasons. First, a world state is probably the most direct

and stable way to prevent nuclear holocaust, a desideratum that must be at the

top of everyone's list. Secondly, the creation of a global state that can

peacefully adjudicate disputes among nations will transform the existing

interstate system. The interstate system (multiple sovereignties in the core)

is the political structure that stands behind the maneuverability of capital

and its ability to escape organized workers and other social constraints on

profitable accumulation (Chase-Dunn 1998: Chapter 7). While a world state may

at first be dominated by capitalists, the very existence of such a state will

provide a single focus for struggles to socially regulate investment decisions

and to create a more balanced, egalitarian and ecologically sound form of production

and distribution.

The

progressive response to neoliberalism needs to be organized at national,

international and global levels if it is to succeed. Democratic socialists should be wary of strategies that focus

only on economic nationalism and national autarchy as a response to economic

globalization. Socialism in one country has never worked in the past and it

certainly will not work in a world that is more interlinked than ever before.

The old forms of progressive internationalism were somewhat premature, but

internationalism has finally become not only desirable but also necessary. This does not mean that local, regional and

national-level struggles are irrelevant. They are just as relevant as they always

have been. But, they need to also have

a global strategy and global-level cooperation lest they be isolated and