Social Movements and Collective Behavior in Premodern polities*

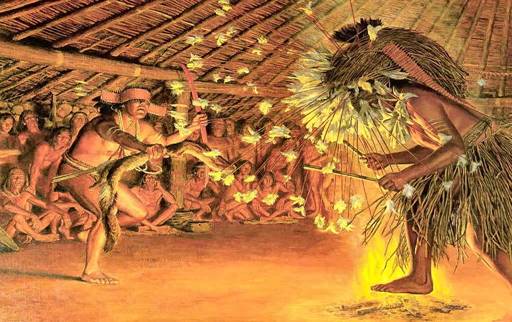

Pomo Bole Maru Big Head Dance, Indigenous Northern California

Christopher

Chase-Dunn

An earlier version was presented at the annual

meeting of the American Sociological Association, Seattle, Washington, August

22, 2016 Regular Session on Social Movements

Institute for Research

on World-Systems

University

of California-Riverside

Draft v. 9-21-16; 8245 words

![]()

This

is IROWS Working Paper #110 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows110/irows110.htm

This is a draft of Chapter 2 of Paul

Almeida and C. Chase-Dunn, Global Change

and Social Movements forthcoming

from Johns Hopkins University Press.

*Thanks

to E.N. Anderson and Bob Edwards for helpful suggestions.

Abstract: This paper contends

that collective behavior and social movements have been important drivers of

social change since the emergence of human language. Migrations to new

locations were usually motivated by population density and competition for

resources, but departure events and many other group decisions were legitimated in terms of ideological formulations

and disagreements. The emergence of larger-scale leadership, hierarchical

kinship and class formation were often legitimated in terms of discourses about

authority, connections with ancestors and disputes about origin myths or the

correct performance of rituals. Evidence of collective behavior and social movements

among hunter-gatherers is described, and premodern movements known from

historical accounts are recounted. The similarities and differences between

social movements in small scale systems and in larger state-based systems are delineated.

Social movements have

long been studied as instances of what sociologists have called collective

behavior (Blumer 1951; Smelser

1962). Collective behavior is understood to consist of non-institutionalized and

somewhat spontaneous actions by human individuals and groups, such as crowds,

riots, revolts, revolutions, fads and etc. Most

social scientists who study social movements think of them as a modern

phenomenon, but some historical ethnographers (e.g. Spier

1935; Wallace 1956; Laurence 1964) have

noted that premodern small-scale polities[1]

also reveal instances of collective behavior that seem rather similar in many

ways to the processes and patterns exhibited by modern social movements. Neil Smelser’s (1962) general theoretical approach contends that

collective behavior and social movements emerge when existing social

institutions are doing a poor job of meeting peoples’ needs and expectations

and that social movements are important agents of social change. This approach is easily extended to premodern

polities, and suggests that collective behavior and social movements have been

important causes of the evolution of social institutions since the Stone Age.[2]

Most

sociological theories see religions as mainstays of social structure and

stability. Institutionalized moral orders, assumptions about what exists and

what is right, are pillars that produce stable expectations and that reinforce

other institutions. Emile Durkheim (1915) described religions as projections of

social structure on the sky (see also Swanson 1960). Egalitarian polities projected beings who had

powers, but also quirks and faults, while many hierarchical polities project

and worship a single omniscient and omnipotent god of the universe.

But religious ideas have also been recurrent

matters of contestation. Religions, even animistic belief systems, are

discourses about authority that are often in dispute. Disagreements about creation

myths or the correct performances of rituals have often been the ideological forms

used to mobilize collective action in both modern and premodern human polities. Projections on the

sky may be used to defend older social structures or to propose and justify new

ones. And indeed, despite the emergence of secular humanism, religious

identities and doctrines continue to be the basis of much hegemonic and

counter-hegemonic contestation and mobilization in the contemporary world. Some

social movement theorists have tended to ignore “primitive” social movements

that are motivated by religious ideologies or that do not utilize modern

repertoires of contention in order to focus only on “modern” secular movements.

These latter are more likely to employ frames based on secular humanism and

legitimation of authority from below (popular sovereignty). But this approach obliterates prehension of the role that social movements have played in

sociocultural evolution and occludes the analysis of those contemporary social

movements that still employ religious ideologies and not so civil modes of

contention.

Globalization remains a contested

concept in both popular discourse and in social science. We propose to distinguish

between: 1. globalization as the spatial

expansion and deepening of human interaction networks and, 2. the “globalization project” that has emerged

since the 1970s as a hegemonic discourse about deregulation, privatization and

austerity (Chase-Dunn 2006).

Globalization understood as the expansion and intensification of spatial

interaction networks has been going on since modern humans migrated out of

Africa to occupy the other continents (Modelski, Devezas

and Thompson 2008; Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2014; Jennings 2010 ). This paper

discusses the roles that social movements have played in social change in

hunter-gatherer bands, world-systems of sedentary foragers and in the processes

of class formation and state formation that occurred in several different world

regions. We propose that the social movements have been an important aspect of

the processes that have driven the expansion and intensification of human

interaction networks since the Stone Age.

David Snow and Sarah Soule’s

(2010:6-7) primer on social movements defines them as “collectivities[3]

acting with some degree of organization

and continuity, partly outside institutional or organizational channels, for

the purpose of challenging extant systems of authority, or resisting change in such systems, in the organization, polity,

culture, or world system in which they are embedded.” This definition is

sufficiently flexible to allow for its application to premodern settings in

which authority structures were less hierarchical and organizational forms were

less bureaucratic. All human polities have had some kinds of authority and some

kinds of organization. But, though authority

in small-scale polities is less centralized and has less power, contentious disagreements

and disputes still occurred and people mobilized one another to address these.

Emigration by groups (hiving off) was an important outcome of disagreements as

well as a response to population pressure. Decisions to leave were often framed

in terms disagreements about the moral order or appropriate ritualized

behavior. Formal authority structures that are centralized provide a clear and

convenient target for protests. So social movements in hierarchical polities

are more easily focused on the symbols and structures of power once these are

institutionally defined. As formal organizational forms emerged, social

movements were able to utilize these as both targets of protest and as

instruments for coordinating participants, increasing the scale and

effectiveness of the movements. And new and better technologies of

communication and transportation were also used by movements. These changes in scale and effectiveness are

why most social movement theorists define movements as a modern phenomenon, but

the less organized, more spontaneous, forms of collective behavior that were

frequent events in premodern polities also had important effects on regime

change and the development of new techniques of power.

Social movement theorists have also

usually assumed that movements come from below and target those above.

Consideration of how movements might have operated in egalitarian polities

makes this assumption problematic, but we contend that it is an assumption that

should be more generally questioned.

Social movement research has long confirmed that leaders of the masses

are more likely to have origins and resources that allow them the opportunities

to mobilize. The poorest and most down-trodden rarely have the resources that

are needed. So leaders of movements tend to be at least from the middle

classes. But it is also important to note that elites often sponsor and lead

social movements. The literature on

state collapse notes that revolutions tend to happen when elites are in contention

with one another. Elites are undoubtedly more likely to utilize

institutionalized forms of power because they have greater access to these. And this is one reason why social movement

theorists tend to assume that movements come from below. But the activities of

some elites seeking to mobilize public opinion and to influence the course of

history often take forms that are very similar to social movements from below. They may seek only to mobilize other elites or

they may mobilize the masses. Either

way, these efforts often take on aspects of collective behavior and need to be

included in order for us to analyze how movements have caused social change.

Collective

Behavior in Small-scale Polities

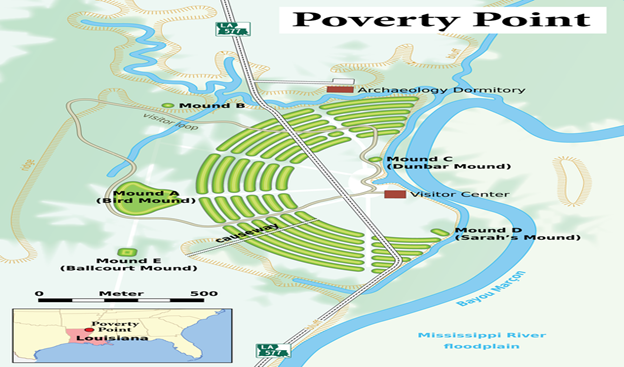

The sources of evidence about

collective behavior processes and premodern social movements in small scale [4]

polities is mostly indirect. We know that humans began burying their dead about

100,000 years ago. Beads appeared in Southern Africa about 70,000 years ago (Klein

and Edgar 2002) and dramatic cave

paintings in Europe are about 50,000 years old. Despite that humans only

arrived in the Americas about 15,000 years ago there is conclusive evidence

that nomadic hunter-gatherers were gathering together to build monumental

mounds in the Mississippi drainage as early as 5500 BCE (Watson Brake) (Saunders

et al 2005) with elaborate and rather

large scale mound complexes appearing between 1650 and 700 BCE at Poverty Point (Sassaman 2005).

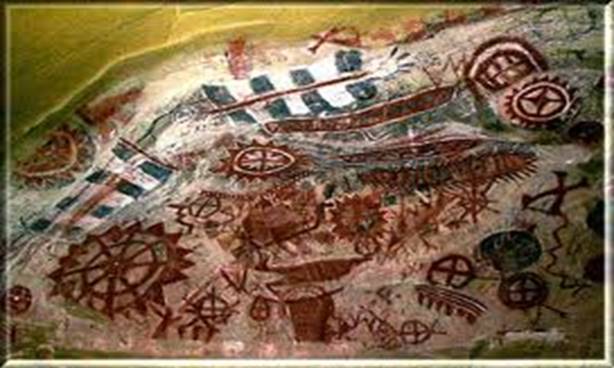

Nomadic and sedentary hunter-gatherers are

known ethnographically and the cave paintings of some of these are associated

with ritual activities. The Chumash were sedentary

foragers who lived along the Southern California coast in what is now Santa

Barbara and Ventura Counties. They built and used a distinctive plank canoe (tomol) that allowed them

to fish offshore and to develop a trade network that linked those living on the

Northern Channel Islands with the villages on the mainland (Arnold 2004). The large coastal villages were also

connected by trade in food items with smaller inland villages in the mountains

and valleys adjacent to the coast (Gamble 2008). The dramatic cave

paintings in the territory of the ethnographically known Chumash are thought to

have been associated with the ‘antap cult, a secret organization of elites who taught

esoteric astronomical knowledge and utilized mind-altering toloache

(jimson weed) to gain access to the spirit world (Johnson nd;

Romani 1981; Hudson 1981). Chumash polities were in transition from the more

typical egalitarian social structure of other California village-living

hunter-gatherers toward class formation. The ‘antap

cult was a manifestation of this transition in which the emergent elites from

autonomous polities demonstrated their superiority over non-elites by carrying

out exclusive ritual performances behind visual outdoor barriers or in isolated

remote locations such as Painted Cave, so that commoners could not see them

(Hudson 1981).

Painted Cave near Santa Barbara

Ethnographers

studying Northern California indigenous polities also observed cults (White Deer among the Hupa, Hesi, Kuksu and Waisaltu among the Patwin, as

well as the Bole-Maru and Bole-Hesi)

in which songs and dances were spread from group to group by moral

entrepreneurs and messingers (Halpern 1988). The most

closely studied instance of this phenomenon is the 1870 Ghost Dance. The 1870 Ghost Dance was an earlier version of

the more famous 1890 Ghost Dance studied by James Mooney 1965 [1896] and many

others (e.g. Wallace 1956;Thornton 1981; Smoak 2006). The 1890 ghost dance supposedly originated

when god spoke to Wovoka (Jack Wilson) while he was alone in the woods near the

Walker River cutting logs. Wovoka became the Paiute messiah who spread the word

from Nevada to many other tribes in the West. But it was Jack Wilson’s uncle

who had spread a very similar doctrine 20 years earlier. Wovoka’s word spread

east, exciting the Lakota and other tribes to don ghost shirts that were

supposed to repel bullets. The ensuing rebellion led to the tragic massacre at

Wounded Knee (Mooney 1965; Fenelon 1998: Chapter 5).

The 1870 Ghost Dance was

studied by Cora DuBois 2007 [1939]. She interviewed surviving participants and

observers of this movement as it spread from the Nevada Paiutes near Walker

Lake across Northern and Central California and Southern Oregon (see also Spier 1927 and Gayton 1930). The most

prevalent formulation of the Ghost Dance doctrine was that all the dead Indians

were going to return to Earth and the whites would die. DuBois was told that

the Ghost Dance doctrine predicted that all the dead Indians since the beginning of time were returning, coming

up from the south, and they would wreak a grim vengeance on the whites.[5]

Half-breeds would turn into rocks. Non-believers would turn into rotten logs.

And the future would be a happy world of abundance and restored nature in which

sickness and death did not occur. [6]

Arapahoe ghost shirt

Moral

entrepreneurs carried the “hurry up word” that the Indians should come together

with certain costumes and songs and dances in order to facilitate the return of

their dead loved ones.

Arapahoe Ghost Shirt

DuBois

tracked the spread and morphological changes of the 1870 Ghost Dance and

analyzed why some groups embraced the new cult while others rejected it. The messengers

were “dream doctors” who used horses and wagons to travel to the homelands of

other tribes in order to teach the dances and songs and spread the word. Most

of the indigenes still did not know how to read or write and so the dream

doctors were reliant on oral communication to spread the ideas of the ghost

dance.[7] The acceptors were those groups that had been

most disrupted by the arrival of the Euroamericans.

The rejecters were less disrupted and the authority of the traditional shamans [8] was more

intact. The traditional shamans regions that were more remote, and so less disrupted,

were able to convince their co-villagers to reject the ghost dance. The local entrepreneurs mixed ideas

from the Paiute ghost dance with older cults such as the Kuksu to produce new hybrids such

as the Bole Maru (Big

Head) dance. And so the form of the rituals became modified as they

traveled.

The

Ghost Dance ideology involved elements that were quite distinct

Arapahoe Ghost Shirt

from

earlier ritual practices and ideas, and some of these may have been due to the

influence of non-indigenous

ideologies

and practices. Women and children were usually not allowed to participate in

the older “dangerous” invocations of spiritual power, whereas they were allowed

and encouraged to attend the ghost dances. The previous indigenous beliefs of most California Indians

included a fear of the spirits of the dead and careful efforts to insure their

journey to a distant and separate realm. The idea that the dead would come back

was blasphemy to many of the traditional shamans. Some of the dream doctors who

took the word on the road were also economic entrepreneurs who instructed

dancers to bring their valuables to the ceremonies to contribute to the cause,

and who sold

ritual paraphernalia such as chicken-feather capes and charged admission to the

performances. In some cases the ideas of the ghost dance were remixed with the

older cult ideas, producing local variations. And the ghost dance ideas were

appropriated and further transmitted by local enthusiasts.[9]

ideologies

and practices. Women and children were usually not allowed to participate in

the older “dangerous” invocations of spiritual power, whereas they were allowed

and encouraged to attend the ghost dances. The previous indigenous beliefs of most California Indians

included a fear of the spirits of the dead and careful efforts to insure their

journey to a distant and separate realm. The idea that the dead would come back

was blasphemy to many of the traditional shamans. Some of the dream doctors who

took the word on the road were also economic entrepreneurs who instructed

dancers to bring their valuables to the ceremonies to contribute to the cause,

and who sold

ritual paraphernalia such as chicken-feather capes and charged admission to the

performances. In some cases the ideas of the ghost dance were remixed with the

older cult ideas, producing local variations. And the ghost dance ideas were

appropriated and further transmitted by local enthusiasts.[9]

One

problem with the study of movements that are ethnographically known is that

they usually occurred in a context in which indigenous life was being radically

altered and threatened by the processes of colonial integration into the

expanding modern world-system and so it is difficult to know which elements of

the movements were characteristics of precontact polities

and which were borrowed from the invading culture. The millenarian aspect of the Ghost Dance,

which was a “hurry up word” in which the old world was coming to an end and a

new world was coming in to being, is often thought to have been such a borrowing

from eschatological Christianity. Norman

Cohn (1970, 1993) contends that millenarianism did not exist before its

emergence with Zoroastrianism and then it spread to Judaism and Christianity. But it is entirely possible that most human polities

contain the cultural tropes of a stable cosmos versus an immanent radical transformation. The five suns of

Mesoamerican religion and related ideas known among village-living

hunter-gatherers of indigenous California suggest that the notion radical

cosmological transition was not uniquely invented by Zoroaster. Millenarianism is a powerful trope for

mobilizing collective action, that continues to play an important role in 21st

century social movements (Lindholm

and Zuquete 2010). It may be far older and more

widespread than Cohn contends. Many human cultures probably contain both notions

of eternal order and of imminent transformation.

AFC Wallace’s (1956) depiction of

the1890 Ghost Dance and cargo cults[10] as

“revitalization movements” focusses on the ways in which these nativist movements

were adaptive responses to the colonial disruption of indigenous cultures that

mixed older institutional forms with new elements inspired by contact with the

expanding Europe-centered world-system. Cora Dubois’s (2007:116) take on this

is less functionalist, but more interesting. Discussing the effects of

Christian ideas on the ideology of the dream doctors she says “… it mirrors the accumulating

despair of the Indians and their realization that there was no room for them in

the new social order. Christian beliefs, which were an outgrowth of a not

dissimilar cultural situation, offered a ready-made escape into supernaturalism

from realities that had become intolerable because they offered nothing but

defeat.” In other words, there was a useful congruence between the ideology of

salvation that emerged from an Iron Age Roman colony in Palestine and the

situation of indigenous peoples of the Americas.[11]

Wallace also surmises that James Mooney’s sympathy with the American indigenes

was partly due to his support for Irish national independence from British

colonialism (Wallace 1965:vi).

There

is evidence that the 1870 and 1890 Ghost Dances were a later reincarnation of

an earlier Prophet Dance that had emerged among the plateau and coastal groups

in British Columbia and Washington (Spier 1935).[12] Spier demonstrated

many similarities between the prophet dance complex that emerged in the early

decades of the 19th century with the Ghost Dance doctrines and

practices that emerged in the 1870s and the 1890s. He contended that the

prophet dance complex was not caused by the disruption of indigenous societies

by the arrival of the Europeans. Suttles (1987) agrees

and proposes that the prophet dance, in which dream doctors proselytized[13]

across a wide area based on dances and songs they had learned by visiting the

land of the dead, was a response to the need of indigenous polities for larger

scale political leadership. This is an importance instance in which a

millenarian social movement is connected with the emergence of new and larger

scale forms of authority.

Cargo cults

were Melanesian millenarian movements encompassing a diverse range of

practices and that occurred in the wake of contact with the commercial networks

of colonizing European polities. The name derives from the belief that various

ritualistic acts will lead to a bestowing of material wealth

("cargo"). Worsley

(1968) saw the millenarianism of the cargo cults as having been borrowed from

Christian missionaries, whereas Lawrence (1964) contended that millenarianism

was part of the precontact Melanesian culture.

Chiefdoms experienced a rise and fall pattern that was somewhat similar in

form to that of larger states and empires (Anderson 1994). Some of the rises

were the result of conquest by semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms, but others may

have been the outcome of a demographic process somewhat similar to the ”secular

cycles” described for state-based systems by Jack Goldstone (1991) and Peter

Turchin and Sergey Nefedov (2009). Turchin

and Nefedov formalized Jack Goldstone’s (1991) model of the secular cycle, an

approximately 200 year long demographic cycle, in which population grows and

then decreases. Population pressures emerge because the number of mouths to be

fed and the size of the group of elites get too large for the resource base,

causing conflict and the disruption of the polity. Turchin and Nefedov test their model on a number of agrarian empires,

confirming the principle that population growth and elite overproduction leads

to sociopolitical instability within states. However, we think that somewhat

similar processes may have been operating within chiefdom polities.

The main differences

between social movements in small-scale polities and those that occur in larger

and more complex polities is the social structural context itself. As mentioned

above, small-scale human polities were fiercely egalitarian. They suppressed

aggrandizing behavior by alpha males, minimized the inheritance of wealth by

burying or burning personal possessions at death and redistributed use rights

to natural resources based on need (Flannery and Marcus 2012; Turchin 2016: Chapter 5). Decisions were made by consensus

in discussions that included all adults. The social movement literature tends

to assume that hierarchy exists and that social movements challenge

hierarchical authorities. When there is little or no hierarchy, how is

collective action mobilized?. The example of the 1870 Ghost Dance provides the

answer. Charismatic bearers of new songs and dances and visions of

transformation (dream doctors) challenged the ideas and ritual practices of

older authorities (sucking doctors) and mobilized action around the new ideas.

Even in small-scale egalitarian polities there were some authorities and there

were taken-for-granted practices and ideas that could be challenged. In the

case of the revitalization movements these were adaptive changes to the larger

colonial situation. It is likely that other reorganizations were similarly

implemented by religious social movements.

Theocratic Early State Formation

The emergence

of socially constructed hierarchy had to overcome great resistance. There is

considerable evidence that hierarchies emerged during periods of warfare and

internal strife in which people were motivated to accept the claims of

superiority of a chiefly class or a charismatic leader who was able to promise

(and deliver) better security. Fatigue

from insecurity plus circumscription (the lack of feasible emigration

destinations) (Carneiro 1970, 1978) lowered the resistance

of the people to claims of superiority on the part of emergent elites. These new elites usually legitimated their

actions in terms of reformulated religious ideologies and they used these to

mobilize collective labor toward both monumental and productive projects. As

interaction networks and polities got larger and more complex, collective

behavior and social movements took forms that were more recognizable by students of modern

collective behavior.

Most studies of the emergence of

early states depict a situation in which religion played an important role in

the establishment of a layer of authority over the top of existing kinship

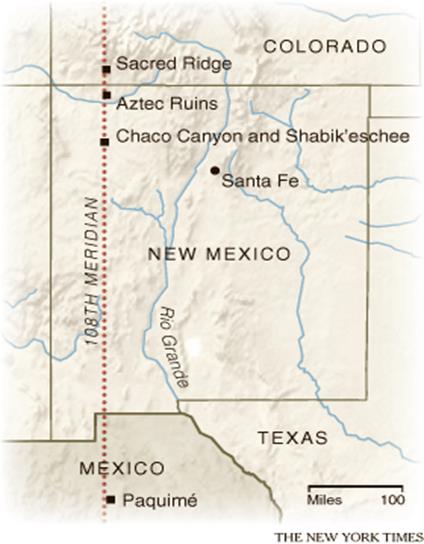

structures. Stephen Lekson (1999) contends that the

rise of a relatively large polity with monumental architecture at Chaco Canyon

( in what is now Northwestern New Mexico) was organized by a religious elite

using astronomical ideas (indicated by the ritual roads centered on the biggest

edifice (Pueblo Bonito) in the canyon). The settlement at Chaco Canyon was

largely abandoned in the twelfth century CE and most archaeologists ascribe

this to climate change (reduced rainfall and catastrophic floods that lowered

the water table by washing out a deep arroyo (e.g. Fagan 1991). Lekson contends

that the Chaco priests led a large group to establish another central place directly

north of Chaco (Aztec Ruin near the Animas River) and then, after another

flooding episode that destroyed an irrigation system, led a third migration to establish Paquimé (Casas Grandes) directly south of both Chaco

Canyon and the Aztec Ruin settlement. If Lekson is

correct Chaco elites were employing an astronomical ideology to mobilize their

populations to adapt to ecological and climatic conditions by relocating and

developing more resilient forms of irrigation.

The Chaco Meridian

Timothy Pauketat (2009) presents

a thorough overview of the archaeological evidence that has accrued regarding

the rise of Cahokia and the Mississippian culture complex of which it was an

important center (see also Mann 2005). Pauketat contends that the construction of this large

settlement in the American Bottom (now East St. Louis) was organized by

religious entrepreneurs who created a dramaturgical set of monuments organized

around a religious ideology that attracted large numbers of immigrants and

legitimated the mobilization of a huge investment of human labor time in the

building of the dramatic monuments. Some archaeologists prefer to consider

Cahokia to have been a complex chiefdom rather than an early state. But the

archaeological evidence of large-scale human sacrifice favors the idea that

this was indeed a state.[14]

Mound 72 contained the remains of fifty-three decapitated young women,

apparently appropriated from poorer families in outlying villages, who seem to

have been honored to join a recently deceased king in the afterworld (Pauketat 2009:133-4).

Timothy Pauketat (2009) presents

a thorough overview of the archaeological evidence that has accrued regarding

the rise of Cahokia and the Mississippian culture complex of which it was an

important center (see also Mann 2005). Pauketat contends that the construction of this large

settlement in the American Bottom (now East St. Louis) was organized by

religious entrepreneurs who created a dramaturgical set of monuments organized

around a religious ideology that attracted large numbers of immigrants and

legitimated the mobilization of a huge investment of human labor time in the

building of the dramatic monuments. Some archaeologists prefer to consider

Cahokia to have been a complex chiefdom rather than an early state. But the

archaeological evidence of large-scale human sacrifice favors the idea that

this was indeed a state.[14]

Mound 72 contained the remains of fifty-three decapitated young women,

apparently appropriated from poorer families in outlying villages, who seem to

have been honored to join a recently deceased king in the afterworld (Pauketat 2009:133-4).

Cahokia (East St. Louis)

In the Uruk or Late Chalcolithic period

(4000-3100 BCE) the first true city (Uruk) grew

up on the floodplain of lower Mesopotamia, and other cities of similar large

size soon emerged in adjacent locations. This was the original birth of

“civilization” understood as the combination of irrigated agriculture, writing,

cities and states. The main architectural feature of these new Sumerian cities was

the temple and this structure has long been considered the primary institution

of a theocratically organized political

economy. Later evidence about Sumerian civilization shows that each

city was represented by a god in the Sumerian pantheon and the priests and

populace were defined as the slaves of the city god – this justifying the

accumulation of surplus product and the mobilization of human labor for building

monumental architecture (Postgate

1992). The Sumerian cities erected their states –specialized

institutions of regional control – over the tops of kin-based normative

institutions (Zagarell 1986). Assemblies of lineage

heads long continued to play an important role in the politics of Mesopotamia

(Van de Mieroop 1999). One interesting difference

between the emergences of archaic states in Mesopotamia from other instances of

pristine state formation is the apparent absence of ritual human sacrifice. A

powerful way to dramatize the power of a king is to bury a lot of other people

with him when he dies. Except for the Third Dynasty of Ur period (the royal

cemetery at Ur), there is little evidence of ritual human sacrifice in

Mesopotamia. The temple economy required contributions of goods and

labor time, including animal sacrifices that were consumed in religious

feasts. But the sacrifice of humans in Mesopotamia, as with modern

states, was mainly confined to killing in battle.

Mesopotamian Ziggurat

(temple)

Revolutions in the Ancient World

Jack

A. Goldstone (2014: Chapter 4) devoted a chapter of his Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction to “Revolutions in the

Ancient World.” We have much better evidence regarding social movements once polities

had developed the ability to record events in writing. The rise of primary or pristine states

occurred in at least five largely unconnected world regions: Mesopotamia,

Egypt, the Indus River Valley, the

Yellow River Valley, the Andes and

Mesoamerica. This is a dramatic case of parallel sociocultural evolution in

which somewhat similar conditions led to the emergence of large settlements and

large polities. In all these cases food production techniques, mainly

irrigation, domestication of animals, and the application of the plow, had

developed to make possible the feeding of large numbers of people living close

together in large cities. The cases of Cahokia and Mesopotamia discussed above are

instances of this kind.

Research

on scale changes in the population sizes of cities and territorial sizes of

polities shows that around half of the cases of upward sweeps in these size

indicators were the result of conquests by non-core marcher states (Inoue, et al 2016). This confirms our

hypothesis that core/periphery relations and uneven development are important

for explaining the emergence of complexity and hierarchy in world-systems, but

it also shows that a significant portion of upsweeps were not associated with

the actions of non-core marcher states. We are developing a multilevel model

(Chase-Dunn and Inoue 2017) that combines interpolity dynamics with the

“secular cycle” model developed by Turchin and Nefadov (2009). This model will include social movement

mobilization and revolutions along with demographic and economic variables.

Goldstone’s chapter is useful because it suggests that his demographic model of

state collapse (formalized by Turchin and Nefadov 2009 as a “secular cycle”) can be applied to

chiefdoms and early states as well as classical and modern ones. Goldstone’s

earliest case of revolution is during and after the reign of Pepy II, the last pharaoh of Old Kingdom Egypt whose reign

ended during the 22nd century BCE. The power of the central

government was being challenged by regional nomes who

were building large funerary monuments to themselves in what Van der Mieroop (2001:xxx) describes as the “democratization of the

afterlife” because the local leaders were presuming to join the pharaoh in the

glorious next world. Social order was breaking down. The poor displayed little

regard for those of rank.

Goldstone also describes the social movements

and revolutions known from the classical Greek and Roman worlds. Here there is

much more documentary and literary evidence describing the processes of social

movements and revolutions. Goldstone recounts the unsuccessful struggles of the

Gracchus brothers in Republican Rome to protect the interests of farmers

against the acquisition of large plantations by slave-owning latifundistas (Brunt 1971). Peasants revolts, slave

revolts, urban food riots, attacks by pastoral nomads, bandits, pirates,

internecine struggles among elites occurred repeatedly in the context of the

rise and fall of regimes and of empires in the ancient and classical

world-systems. Turchin (2003: Chapter 9) notes the

relevance of Ibn Khaldun’s cyclical model of the rise

and fall of regimes and the importance of changing levels of asabiyah (loyalty,

solidarity and group feeling) as old regimes became decadent and new

challengers emerged from the desert to form new regimes (see also Amin 1980; Chase-Dunn

and Anderson 2005).

The rise of the world religions[15]

during and after the axial age display the

interaction between social movements and forms of governance. World

religions in our sense separate the moral order from kinship, allowing for and

encouraging the inclusion of non-kin into the circle of protection. This is the

expansion of human rights beyond the bounds of kinship and the expansion of what Peter Turchin (2016) calls “Ultrasociety”

– altruistic behavior among non-kin. Marvin

Harris (1977) pointed to the frequency of ritual cannibalism practiced on

enemies in systems of small scale polities. In small systems non-kin are not

really humans. They are enemy others that are not due any positive reciprocity

(Sahlins 1972). The question of who are humans and who are not

the humans is important in all cultures. In small-scale polities the

distinction between “the people” and the non-people is usually a mixture of

kinship relations and familiarity with a language. The moral order applies to

the circle of the people and heavy othering sees the non-people as animals or

enemies. When world-systems expanded important debates occurred as to whether

newly encountered peoples had souls, or not. The rise of what we currently call

humanity was a long slow, back and forth and uneven process that continues in

the current struggle over citizenship.

World religions locate great agency in the

individual person even if it is only the right to declare obedience. To become a member of the moral order a

convert must herself confess and proclaim belief in the godhead. This is the

act of an individual person. One’s own action is required. Non-world religions

usually tie membership to one’s birth parents. Salvation is also a further

democratization of the afterlife. Now

the masses too may go to heaven or become enlightened.

Harris contends that the rise of world

religions was functional for expanding empires because they included the conquered populations within the

moral order of the conquerors. This proscribed cannibalism and reduced the

amount of resistance mounted by prospective conquerees.

The king makes you pay tribute and taxes but he will not eat you. Most world

religions began as social movements from the semiperiphery or the periphery

(Bactria, Palestine) that were eventually adopted by the emperors. Prophets and

charismatic leaders mobilized cadres who spread the word orally and with

written documents. Sects and communities of believers were organized,

eventually producing formally structure churches. Older institutions resisted,

often repressing the new movements, but they continue to spread, in some cases

becoming conquering armies, and in other cases becoming adopted by kings and

emperors. Some of the world religions

were monotheistic, but others had no godhead at all except the path to

enlightenment.

There is a well-developed and convincing literature

on early Christianity as a social movement (Blasi

1988; Mitchell, Young and Bowie 2006). The interesting thing already mentioned

is world-systemic context of the origin of the movement. Christ and his

followers emerged in a context of a powerful Roman colonialism in which the

colonized peoples were faced with overwhelming force. The ideology of

individual salvation and rendering unto Caesar what is Caesar’s with

concentration on the rewards of life after death was powerful medicine for

those who faced a mighty Roman imperialism. Paul’s mission to other colonized

peoples and the delinking of salvation from ethnic origin was a recipe that

allowed the movement to spread back to the poor peoples of the core. And

eventually it was adopted by the Roman emperors themselves as a universalistic

ideology that could serve as legitimation for a multi-ethnic empire. The prince

of peace and salvation ironically proved to be a fine motivator for later

imperial projects such as the reconquest of Spain

from the Moors and the conquest of Mesoamerica and the Andes (Padden 1970). And as Cora Dubois (2007:116)

has said,

it also worked for the conquered as a way for them to survive psychologically

and to adapt to a world in which their indigenous lifeways were coming to an

end. Recall the discussion of “revitalization movements” above.[16]

Hinduism and Confucianism are not very

proselytizing but they both spread successfully because they provided a new

justification for hierarchy and state-formation. The spread of Hinduism to mainland and island

Southeast Asia occurred because its notion of the god-king (deva-raja) provided

a useful ideology for the centralization of state power in a context of smaller

contending polities (Wheatley 1975). Confucianism provided a different

justification for state power based on the notion of the mandate of heaven and

it spread from its original heartland to the rest of China and Korea.

So what

were the similarities and differences between social movements in small scale

polities and those that occurred in larger-scale chiefdoms and states? As we

have already said, the biggest differences were in the social structural

contexts. In egalitarian polities authority

was more diffuse. But it still existed and movements could define themselves as

revised versions of authority such as occurred in the contest between the traditional

shamans and the dream doctors. The diffusion of new ideas was constrained by

modes of transportation and by simple technologies of communication in systems

of small scale polities. The new words, songs, dances had to be carried on

foot. This was a limitation on how far and fast the ideas could spread. In

multilingual situations the signal to noise ratio was low as the original ideas

were lost in translation. This could be seen in the mixing of the ghost dance

ideas with other, earlier, cult forms. Down-the-line transmission of

information also adds noise. Sign languages were also in use in indigenous

North America (Davis 2010), but these were not good media for transmitting the

subtleties of new cult ideas (Mooney 1965: 19). Obviously the invention of

writing and literacy increased the signal to noise ratio and allowed ideas to

spread much faster and farther, not to mention the telegraph the radio and the

internet. New “religions of the book” transformed rituals of the spoken word

into worship of the text.

Boat and

caravan transportation facilitated the more rapid and distant spread of ideas.

Institutions such as money and the law emerged in part as efforts to control

social movements from below, but they could also be used by social movements.

The same goes for economic and military organization. Bureaucracies and formal

organizations were usually created to reproduce social orders, but social

movements could also appropriate these inventions and use them to mobilize

social change.

In the modern world-system there has been a

spiral of interaction between world revolutions and the evolution of global

governance that we will discuss in the next chapter. World revolutions are

periods in world history in which a large number of rebellions break out across

the world- system, often unconnected with one another, but known, and responded

to, by imperial authorities. Since the protestant reformation such

constellations of social movements have played an important role in the

evolution of global governance because the powers that can best handle

collective behavior challenges are the ones who succeed in competition with

competing elites. It is possible that similar phenomena existed in premodern

world-systems. Oscillations in the expansion of trade networks, the rise and

fall of chiefdoms, states and empires, and increasing synchronization of trade

and political cycles may have been connected with waves of social movements.

This is a hypothesis that we have only begun to think.

References

Amin, Samir 1980. Class

and Nation, Historically and in the Current Crisis. New York:

Monthly Review Press.

Anderson, David G. 1994 The Savannah River Chiefdoms:

Political Change in the Late Prehistoric Southeast. Tuscaloosa, AL:

University of Alabama Press.

Arnold, Jeanne E. (ed.) 2004 Foundations of Chumash

Complexity. Perspectives in California

Archaeology,

Volume 7. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute

of Archaeology, University of

California-Los

Angeles.

Blasi, Anthony D. 1988 Early

Christianity as a Social Movement. New York: Peter Lang

Blumer,

Herbert 1951 “Collective Behavior” Pp 166-222 in A.M. Lee (eds.) New Outline of the

Principles

of Sociology.

New York: Barnes and Noble.

Brunt, P.A. 1971 Social

Conflicts in the Roman Republic. London, Chatto and Windus

Chase-Dunn, C. and Kelly M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and

Their Neighbors. Tucson: University of

Arizona Press.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher. 2006. “Globalization: A World System Perspective.” Pp. 79-105 in

C. Chase-Dunn and

S. Babones, eds., Global

Social Change: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Baltimore: John

Hopkins University Press.

Chase-Dunn, C. and E.N.

Anderson (eds.) 2005 The Historical Evolution of World-Systems London: Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn, C. Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis Alvarez and Thomas D. Hall. 2006 “Waves of

Globalization and Semiperipheral Development in the

Ancient Mesopotamian and

Egyptian World-Systems” Pp. 114-138 in Barry Gills and William R.

Thompson (eds.),

Globalization and Global History London:

Routledge.

Chase-Dunn, C. and B. Lerro

2014 Social Change: Globalization From

the Stone Age to the Present.

London:

Routledge

Chase-Dunn, C and Hiroko Inoue 2017 “Spirals of sociocultural

evolution within polities and in

interpolity

systems” To be presented at the annual meeting of the International Studies

Association,

Baltimore, Maryland February 22nd-25th

Cohn,

Norman 1970 The Pursuit of the Millennium.

New York: Oxford University Press.

____________

1993 Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come New

Haven: Yale University Press

Davis,

Jeffrey E. 2010 Hand Talk: Sign Language

among American Indian Nations. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

DuBois,

Cora 2007 [1939] The 1870 Ghost Dance.

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press

Durkheim, Emile 1915 The

Elementary Forms of Religious Life New York:Macmillan

Fagan, M. Brian 1991 Ancient North

America: The Archaeology of a Continent. London:

Thames

and Hudson.

Fenelon, James 1998 Culturicide,

Resistance and Survival of the Lakota New York: Garland Publishing

Flannery,

Kent and Joyce Marcus 2012 The Creation

of Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Freeden, Michael 2003 Ideology. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Gamble,

Lynn 2008 The Chumash at European Contact.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gayton, Anna H. 1930 The

Ghost Dance of South Central California. American Archaeology and

Ethnology,

v28,No, 2: 57-88

(March)

_______________2014

Revolutions. New York: Oxford

University Press

Halpern, Abraham M.

1988 Southeastern Pomo

Ceremonials: The Kuksu Cult and Its Successors.

University of California Publications,

Anthropological Records Volume 29,

Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Harris,

Marvin 1977 Cannibals and Kings New

York: Random House

Herrmann, Edward

W, G. William

Monaghan, William F. Romain, Timothy M. Schilling,,

Jarrod Burks, Karen L. Leone, Matthew P. Purtill, and Alan C. Tonetti 2014 “A new multistage

construction chronology for

the Great Serpent Mound, USA” Journal of

Archaeological Science

Volume 50, Pages

117–125. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440314002465

Hobsbawm, Eric 1957 Primitive Rebels : studies in archaic forms of social movement

in the 19th and 20th

centuries, Manchester: Manchester

University Press.

Hudson,

Travis 1982 Guide to Painted Cave.

Santa Barbara, CA: McNally and Loftiin

Inoue,

Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez,

E.N. Anderson, Kirk Lawrence, Teresa Neal, Dmytro Khutkyy,

Sandor

Nagy, Walter De Winter and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2016

“Comparing World-Systems: Empire

Upsweeps and Non-core marcher states Since the Bronze Age’ IROWS

Working Paper #56

Jennings,

Justin 2010 Globalizations and the

Ancient World. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Johnson, John n.d. “California

Indian Religions”

http://www.anth.ucsb.edu/classes/anth131ca/CA%20Indian%20Religion.pdf

Klein, Richard G. and Blake Edgar 2002 The Dawn of Human Culture. New York:

John Wiley

Lawrence, Peter 1964 Road Belong Cargo: A study of the cargo movement in the Southern Madang

District,

New Guinea Manchester:

Manchester University Press

Leckson, Stephen H. 1999 The

Chaco Meridian: Centers of Political Power in the Ancient

Southwest. Walnut

Creek, CA; Altamira Press.

Lindholm, Charles and Jose

Pedro Zuquete 2010 The Struggle for the World: Liberation Movements for the

21st Century. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Mann, Charles C. 2005 1491:New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York:

Vintage

Marx, Karl 1844. A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy

of Right

_________1972 [1869] The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

New York: International Publishers.

Mitchell, Margaret M., Frances M. Young

and K. Scott Bowie (eds.) 2006 The

Cambridge History of

Christianity, Volume 1 : Origins

to Constantine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Modelski, George, Tessaleno Devezas and William R.

Thompson 2008 Globalization as

Evolutionary

Process. London: Routledge.

Mooney, James 1965 [1896] The Ghost Dance Religion and Sioux Outbreak

of 1890. Chicago: University

of

Chicago Press

Padden, R.C. 1970 The Hummingbird and the Hawk: conquest and sovereignty in the valley of Mexico, 1503-

1541. New York: Harper and Row

Pauketat, Timothy 2009 Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi. New York:

Viking

Postgate, J. N. 1992 Early Mesopotamia :

society and economy at the dawn of history London ; New

York :

Routledge.

Romani, John. F. 1981 “ASTRONOMY AND SOCIAL INTEGRATION:

AN

EXAMINATION OF ASTRONOMY IN A HUNTER AND GATHERER POLITY”

thesis

submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master

of Arts in Anthropology,

CALIFORNIA

STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE http://scholarworks.csun.edu/handle/10211.3/127672

Ruby, Robert H. amd John A Brown 1989 Dreamer-Prophets of the Columbia Plateau: Smohalla and Skolaskin.

Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Sahlins, Marshall 1972 Stone Age Economics. Chicago: Aldine.

Sassaman, J.A. 2005 “Poverty Point as Structure,

Event, Process” Journal of Archaeological

Method and Theory

Volume 12, Issue 4, pp 335–364.

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10816-005-8460-4

Saunders, Joe W., Rolfe D. Mandel,

C. Garth Sampson, Charles M. Allen, E. Thurman Allen,

Daniel

A. Bush, James K. Feathers, Kristen J. Gremillion, C.

T. Hallmark, H. Edwin

Jackson,

Jay K. Johnson, Reca Jones, Roger T. Saucier, Gary L.

Stringer and Malcolm F.

Vidrine 2005 “Watson Brake, a Middle Archaic Mound Complex in Northeast

Louisiana”

American Antiquity Vol. 70, No. 4 pp. 631-668

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40035868?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Scarborough,

Vernon L and David R. Wilcox (eds.) 1991 The

Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson:

University of Arizona Press.

Schaeffer,

Robert K. 2014 Social Movements and

Global Social Change. Lanham, MD: Rowman

and Littlefield.

Smelser, Neil

J. 1962 Theory of Collective Behavior.

New York; The Free Press

Smoak,

Gregory E. 2006 Ghost Dances and Identity: Prophetic Religion and American Indian Ethnogenesis in

the

Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Snow, David A. and Sarah A. Soule

2009 A Primer on Social Movements New

York: Norton.

Spier, Leslie 1921 “The

Sun Dance of the Plains Indians: Its Development and Diffusion” New

York: Anthropological Papers of the

American Museum of Natural History, Vol. 16, Part 2

__________1927

The Ghost Dance of 1870 Among the Klamath

of Oregon. Seattle: University of

Washington Press.

__________

1935 “The Prophet Dance of the Northwest and its Derivatives: The Source of the

Ghost Dance” General Series in

Anthropology. Number 1. Menasha, WI: George Banta

Publishing Company

Suttles, Wayne 1987 Coast Salish Essays. Seattle: University

of Washington Press.

Swanson,

Guy E. 1960 The Birth of the Gods: the

origin of primitive beliefs Ann Arbor: University

of Michigan Press.

Thornton, Russell 1981 “Demographic Antecedents of a Revitalization

Movement:

Population Change, Population Size

and the 1890 Ghost Dance” American

Sociological

Review, Vol. 46, No. 1

(Feb.), pp. 88-96

______________

1986 We Shall Live Again: The 1870 and

1890 Ghost Dance movements as

demographic

revitalization. ASA

Rose Monograph Series, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Turchin, Peter 2003 Historical Dynamics Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

____________2016

Ultrapolity Chaplin, CT: Beresta

Books

__________

and Sergey A. Nefadov 2009 Secular Cycles. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Van de Mieroop, Marc 1999 The

Ancient Mesopotamian City. New York: Oxford University

Press.

_________________ 2011 A

History of Ancient Egypt. Malden, MS: Wiley-Blackwell

Wallace, Anthony F.C. 1956 “Revitalization

movements” American Anthropologist 58: 264-281.

___________________

1965 “James Mooney (1861-1921) and the study of the Ghost Dance

religion” Pp.v-x

in James Mooney The Ghost-Dance Religion

and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890.

Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Wheatley, Paul. 1975.

"Satyanrta Suvarnadvipa: from Reciprocity to Redistribution in Ancient

Pp. 227-284 in Ancient Civilization and Trade, edited by J. A. Sabloff

and C. C. Lamberg-Karlovski.

Wolf, Eric R. 1997 Europe and the People Without

History, Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Worsley, Peter 1968 The Trumpet Shall Sound: A Study of “Cargo”

Cults in Melanesia. New York:

Schocken

Zagarell,

Allen. 1986. "Trade, Women, Class and Society in

Ancient Western Asia."

Current

Anthropology 27:5(Dec.):415-430.