The World-System(s)

Dmytro

Khutkyy and Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute

for Research on World-Systems,

University

of California Riverside

Forthcoming in William Outhwaite and Stephen Turner (eds) Sage

Handbook on Political Sociology

v. 9-20-16 7634 words

This is IROWS Working Paper #112

available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows112/irows112.htm

The

world-systems perspective is an integral social science approach that advocates

the study of long-term, large-scale historical systems in their totality. Its

evolutionary version includes comparisons between the modern Europe-centered

system of the last six centuries with earlier regional whole interpolity

networks. Relevant evidence comes from archaeology, ethnography and historical

documents as well as demographic and economic estimates. Research by

anthropologists, political scientists, historians, ecologists, geographers,

economists and sociologists is often germane to studies of whole interaction

systems. The general theoretical approach rests on institutional materialism

with roots in the works of Marx and Weber (Chase-Dunn and Hall 2000).

Immanuel

Wallerstein, Samir Amin, Andre Gunder Frank and

Giovanni Arrighi were the originators of the

world-system perspective in the 1960s and the 1970s (Amin 1980a; Frank 1966,

1967,1969; Arrighi 2010[1994]; Wallerstein 2011a[1974]).

They focused primarily on the modern world-system that had emerged with

European predominance. Wallerstein (2000: 74) enounces:

we take the defining

characteristic of a social system to be the existence within it of a division

of labor, such that the various sectors or areas are dependent upon economic

exchange with others for the smooth and continuous provisioning of the needs of

the area.

In

such a formulation human social systems are clusters of social life with

recurrent social relations implying an established structure of interdependent

parts. In complexity science terms this approach emphasizes the primacy of properties

of the system as a whole over its components. Wallerstein’ s approach employs a

typology of world-systems as follows: a mini-system is an entity with a

complete division of labor and a single cultural framework; a world-economy is

a unit with a single division of labor and multiple cultural and political

entities; a world-empire is a division of labor with a single political authority

(Wallerstein 2000: 75). Then, the modern global system is a world-economy with

multiple sovereign states linked into a single economic division of labor. The

“world” idea refers to a whole self-sufficient entity, which is not necessarily

Earth-wide. In the past there were whole regional world-systems.

The

comparative evolutionary[1]

world-systems perspective emerged when some of the world-system scholars became

interested in the long-term continuities as well as the qualitative

transformations in the logic of development that only become evident when the

modern world-system is compared with earlier world-systems (Frank and Gills

1993; Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997).

The

comparative and evolutionary world-systems perspective is a strategy that

focuses on whole interpolity systems (world-systems) rather than single

polities; its main insight is that important interaction networks (trade,

information flows, alliances, and fighting) have woven polities together since

the beginning of human sociocultural evolution (Chase-Dunn and Khutkyy 2016).

World-systems

are defined as whole systems of interacting polities and settlements.[2]

Systemness here means that these polities and

settlements are interacting with one another in important ways – such

interactions are two-way, necessary, structured, regularized and reproductive. These

interactions impact human life and affect the resulting social continuity or

social change.

Systemic

Spatial Boundaries

Social

groups are connected by information flows, luxury goods exchanges, bulk goods

provisioning and trade, and political-military interactions. These interactions

form networks that have different spatial scales, especially in older and

smaller regional world-systems. In order to spatially bound whole interpolity

interaction networks it is necessary to adopt a “place-centric” approach. This

is because nearly all human polities interact with their immediate neighbors,

and so if we count all indirect connections there has been a single global

network since the humans migrated to all the continents. But such a diffuse

global network is not really a single system because the consequences of interactions

dissipate with distance. So it is necessary to focus on a single locale and to

ask what is the world-system of which this locale is a part?

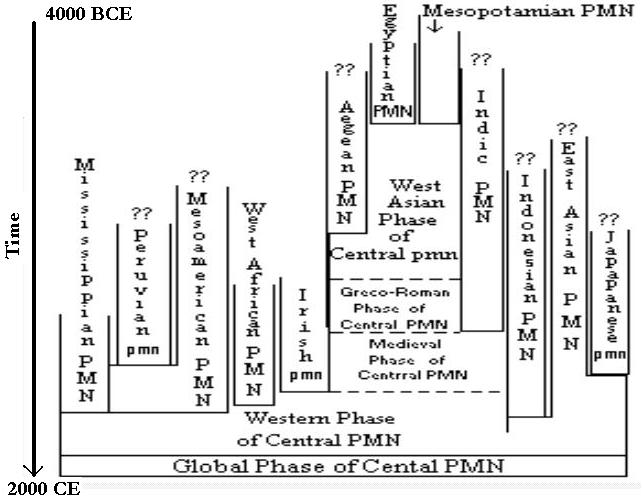

Bulk

goods such as everyday foods and building materials tend to have been mostly obtained

locally. Households and local kin groups provided most of the food, but feasts

were occasionally held in which neighboring villages or more distant allies

were invited to partake. The bulk goods provisioning network fell off quickly

with distance. Nearly all autonomous polities engage in warfare and military

alliances with other polities and so there is an interpolity[3]

warfare/alliance web that Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) call the

political/military network (PMN). This a network of fighting and allying

polities that is analogous to the contemporary international system of states

except that the polities may be bands, tribes, or chiefdoms as well as states

and empires. The political/military network tends to be larger than the bulk

goods network, as illustrated in Figure 1. An even larger network is based on

the exchange of prestige (luxury) goods. Wallerstein claimed that luxury goods,

which he called “preciosities” were not systemic and so they were exchanged

between a world-system and its “external arena” (other world-systems). But many

anthropologists contend that there have been prestige goods systems in which

local social hierarchies are constructed around the monopoly that elites have

over the importation of exotic goods that are required for important social

rituals such as marriage. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) also posit the existence

of a large information or communications network that can have systemic

importance in some world-systems (see Figure 1).

Figure

1: The spatial boundaries of interaction networks

These different types of interaction may also

differ with regard to their importance for the reproduction or change in local

social structures. The bulk goods and political/military networks are important

in all systems, but the prestige and information networks are typically less

important and may be not be systemic in some regions. The nature of these interactions

may also differ across systems. Bulk goods may be obtained through sharing and

reciprocity in small-scale world-systems, whereas in larger systems they may be

mainly obtained as purchased commodities. Prestige goods systems may be of the

kind mentioned above in which these goods serve as a mechanism for rewarding

subalterns, but they may also operate as storable forms of wealth that can be

used during times of shortage to obtain food from neighboring polities (Chase-Dunn

and Mann 1998).

Long-distance

trade initially involved luxury goods because they are valuable enough to move

long distances. At the beginning of the first millennium the Silk Road

connected states and empires in China, South-East Asia, India, Central Asia,

Western Asia, North Africa and Europe. Moreover, some states and empires were

organically linked to major trade routes – like Sogdiana, Turgis

Kaghanate, Arab Empire and the Byzantine Empire

(Beckwith 2009). At first, long-distance trade was small scale, monopolized,

and extremely profitable. Major wars were caused by efforts to control key

trade routes. The Crusades of the eleventh-thirteenth centuries CE had a latent

economic goal of seizing Palestinian cities in order to raise the Moslem blockade

of the Silk Road trade. The Portuguese circumnavigation of Africa was financed

by Genoese merchants who desired an alternative route to Southeast Asian spices

in order to compete with Venice.

Immanuel Wallerstein's (1974) definition of the

spatial boundaries of a world‑system focused on links in an

interdependent network of the

exchange of "fundamental commodities," by which he meant food and other necessities of everyday life (here called bulk

goods). He excluded the exchange of "preciosities" (luxuries)

that were alleged to not have important consequences for the exchanging parties

or their societies. Wallerstein also emphasized the importance of mode of

production (capitalism) as a feature of a whole world-system that could be used

to distinguish between the modern Europe-centered system and the Ottoman

Empire. And he used the idea of a core/periphery division of labor to

distinguish between “external arenas” and the periphery within the modern

system (Wallerstein 2011[1974]).

Some social scientists have claimed that there

has been a single global world system extending back for thousands of years

(e.g. Modelski 2003; Lenski 2005). Others focus exclusively on only one of the systems that

eventually incorporated all the others into a global system (Frank and Gills

1993). The first of these positions is misleading because it does not concern

itself with the strength of cultural, political and economic systemness across space. The second position is

impoverished by its failure to seize the opportunity to compare what were

separate regional world-systems with one another. Frank and Gills (1993) focused on the 5000-year history of what they

saw as a system with great continuities that began with the rise of cities and

states in Mesopotamia. They traced the expansion of this system and noted that it

did not include the Americas before 1492 CE. They claimed that this system that

began in Mesopotamia already displayed a “capital-imperial” mode of

accumulation[4] and that this mode was

continuous until the present, and so there was no “transition to capitalism”

that occurred with the rise of the West. They also emphasized the centrality of

China in the Eurasian world-system. But they failed to compare the expanding

system they were studying with other world-systems that existed outside it.

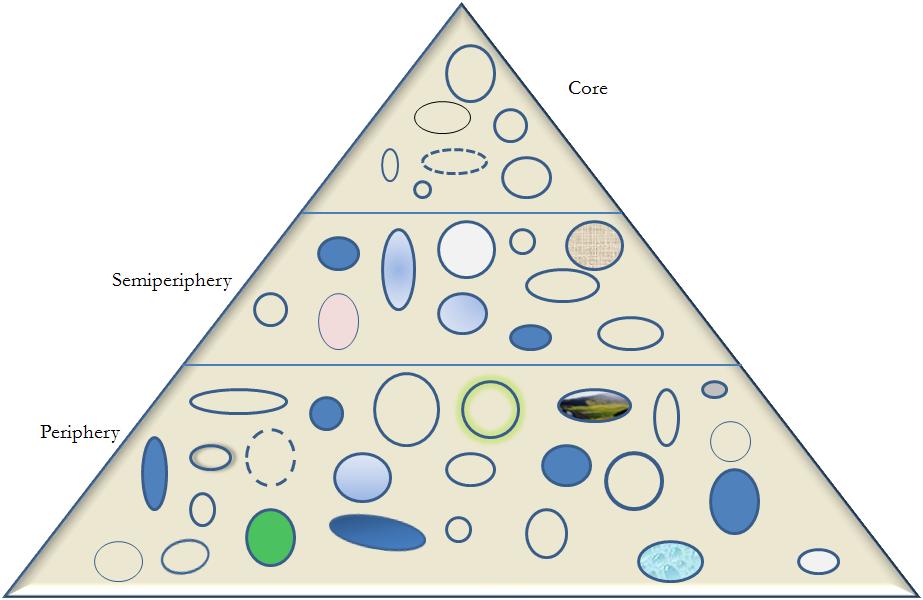

The

most explicit and detailed approach to specifying systemic spatial boundaries

in world history has been developed by David Wilkinson, a political scientist

who focuses on networks of fighting and allying states (what Chase-Dunn and

Hall call political/military networks (or PMNs). Wilkinson has mastered the

historical literature on warfare and alliance-making in order to determine the

times and places in which that interpolity network that emerged in Mesopotamia

became systemically linked with other areas (see Figure 2).

Figure

2: Chronograph of the spatial boundaries of political/military networks (PMNs)

showing the expansion of what David Wilkinson (1987) calls “Central

Civilization”

Core/Periphery

Hierarchies

Wallerstein’s

definition of a world-system as a division of labor has in mind a hierarchical division of labor in which

some polities exploit or dominate others. In world-systems parlance this kind

of structure is often called a core/periphery hierarchy in which core, peripheral

and semiperipheral polities are in systemic and asymmetric (hierarchical) interaction

with one another.

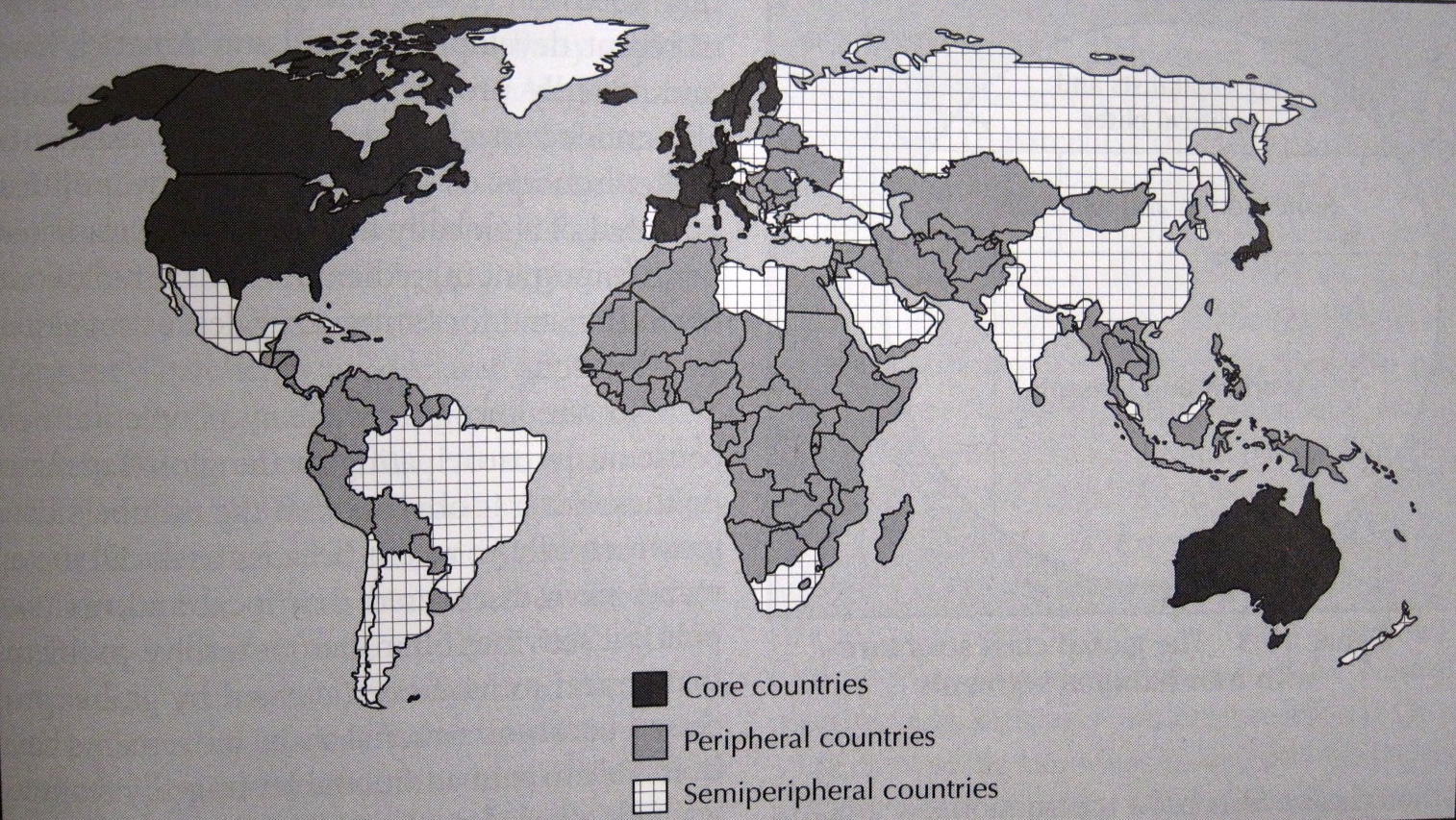

Figure

3: A core/periphery hierarchy

Core/periphery

relations are one of the most important foci of world-systems analysis (see

Figure 3.[5]

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) took the position that world-systems could exist in

the absence of core/periphery relations. Chase-Dunn and Mann (1998) studied

such a system in precontact Northern California but

it did not fit Wallerstein’s definition of a “mini-system” (single culture and

a division of labor) because the interacting (trading, allying and fighting)

polities spoke very different languages and had different cultures. This was a

small-scale world-system composed of sedentary foragers (hunter-gatherers) in

which there was little or no interpolity exploitation or domination. Core/periphery

hierarchies emerged and became institutionalized as some polities invented

methods for extracting resources from, and dominating, distant other polities.

The question of the spatial scale of interaction discussed above is prior to

the issue of core/periphery relations. Unconnected polities cannot have

core/periphery relations with one another.

The

first cities and states emerged in Mesopotamia (a region in which chiefdoms and

irrigated agriculture already existed) around 3,000 BCE. Uruk

was the first of these theocracies, and similar city-states soon emerged on the

floodplain of the Tigris and the Euphrates to form an intercity-state system of

allying and war-making states that were also interacting with adjacent

horticultural chiefdoms and nomadic pastoralists.

After a period of several centuries in which

hegemonic city-states rose and fell, Sargon’s Akkadian Empire conquered all the

Mesopotamian city-states as well some adjacent areas to form the first conquest

empire. This pattern of rise and fall of the largest settlements and polities

was repeated in several world regions with some interesting and important

differences: Egypt, the Indus River valley, the valley of the Huáng Hé (Yellow) River, the Andes, and Mesoamerica.

These are important instances of parallel sociocultural evolution in which

similar social structures and institutions emerged under similar conditions in

areas that were unconnected or only weakly connected with one another. This,

and the independent emergence of horticulture in eight world regions, is strong

evidence in favor of the existence of sociocultural evolution.[6]

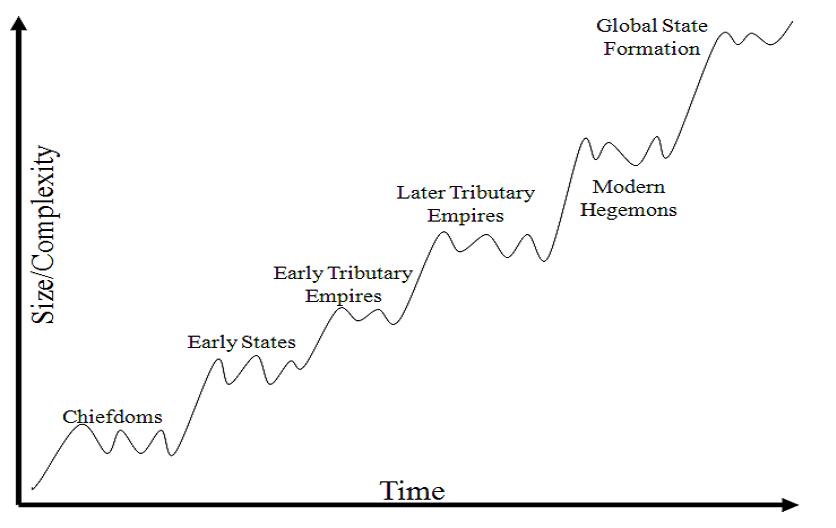

There

were long-term upward trends in the sizes of largest cities and largest polities

that corresponded with the increasing complexity and hierarchy of human

polities. These long-term trends in spatial scale and complexity of have been

constituted by upsweeps – events in which the sizes of cities and polities

increased significantly over what they had been in the past (Inoue et al 2012; Inoue et al 2015). A study of twenty-one upsweeps in the territorial

sizes of states and empires in five world regions since the Bronze Age found

that to thirteen of them involved the actions of non-core polities, mostly

semiperipheral marcher states ((see also Inoue et al 2016). This is strong evidence for the importance of

interpolity competition in processes of state expansion. And it demonstrates that core/periphery

relations need to be taken into account in explanations of sociocultural

evolution.

Figure 4 does not depict what has happened in

any single regional system but rather what has happened when the totality of

all the systems are considered.

Figure

4: The rise-and-fall polities with occasional upward sweeps in polity size and

complexity

The

Modern World-System and Definitions of Capitalism

Fernand

Braudel (1992) performed an encompassing study of

material life in medieval Europe that portrayed the links between simple household

and village production (the first level of the local economy) with market exchange

(the second level of economy), manufacturing, long-distance trade, banking, and

monopolies (the third level of economy) marking the last level as the realm of

capitalist accumulation. Braudel noted that market

exchange is usually beneficial for all parties and is substantially fair. He

contrasts this with capitalist accumulation which is usually based on unequal

exchange, exploitation and monopolization that employs military, political,

religious, and ideological means to extract surplus. Among the many definitions

of capitalism, one of the most laconic is that capitalism is a system that is

organized around the endless accumulation of capital (Arrighi

2010[1994]: 33). Of course, there can be different sources of capital

accumulation. Profits can be made from long-distance trade, banking, agricultural

or industrial production or services. This provides capitalism with its

outstanding flexibility (Arrighi 2010[1994]: 5). In

modern times profitable commercial deployment of new leading technologies

(alternative energy, biotechnologies, nanotechnologies, artificial

intelligence, cloud computing etc.) endow both corporations and states with

considerable advantages.

A

longer list of capitalism’s defining characteristics should include: (1)

generalized commodity production in which the “fictitious commodities” of land,

labor, and wealth are substantially commodified, (2) ownership and/or control

of the means of production, exercised by individuals, organizations and states,

(3) accumulation of capital based on a mix of competitive production of

commodities and political-military power, (4) exploitation of commodified

labor, and (5) a combination of class exploitation and core/periphery exploitation

(Chase-Dunn 1998: 43).

The

world-systems perspective views capitalism as a logic of development that

combines Marx’s definition of capital accumulation based on wage labor with an

equally necessary component of accumulation based on coerced labor that occurs

in the non-core. It is emphasized that capitalist slavery and capitalist

serfdom were very important to the development of the capitalist world-system

and that extra-economic coercion remains a significant aspect of even the 21st

century capitalism.

Capitalism

first became a predominant logic of accumulation in a whole world-system six hundred

years ago, when Genoa and Portugal combined forces to rewire the emerging

Europe-centered world-system (Arrighi 2010[1994]). And then in the seventeenth century the United

Provinces of the Netherlands rose as a fore-reaching capitalist state that

combined features of earlier city-states with a federal structure that supported

the emergence of joint stock companies, a stock exchange and a colonial empire

built around profit-taking rather than taxation (Wallerstein 2000).

A

capitalist state is one in which those gaining most of their wealth from

commodity production and market trade hold predominant control over the state

apparatus. Capitalist city-states had existed since the Bronze Age, but they

were usually located in the semiperiphery of larger world-systems in which

tributary states (that used state power itself as the main institutional basis

of accumulation) were predominant. The rise of the capitalist city-states of

Italy and then the capitalist nation-state of the Dutch signified a move from

the semiperiphery to the core and the rise of a world-system in which

capitalism was increasingly becoming the predominant mode of accumulation.

But

even in the capitalist world-system economic agents still rely on states to

promote their interests by military and political means and to deal with social

unrest. At the same time, the existence of multiple competing states – the

international system – provides maneuvering space for capitalists who can

bargain better conditions for profit making by pitting competing states against

one another. This is why many capitalists are wary of the emergence of a world

state (Chase-Dunn 1998).

New

lead industries and generative sectors have played important roles in the

unequal distribution of surplus within different parts of the modern

world-economy (Modelski and Thompson 1996; Bunker and

Ciccantell 2005). The emergence of new technologies

and sectors allows those who control them to earn technological rents because

they hold a monopoly until these innovations spread to the competitive sector. The

large accumulators flexibly move their capital to new leading industries in new

regions, creating quasi-monopolies that facilitate capitalist accumulation

(Wallerstein 2004: 27). But there is also an important degree of uneven

development in the competition among core states and the emergence of

challengers from the none-core zones.

An

important debate about the nature of socialist states occurred among political

sociologists in the 1970s. Albert Szymanski (1979) claimed that "state

socialism" did exist in the Soviet Union and that the existing socialist

states constituted a separate socialist world-system. On the other hand, Tony Cliff (1974) contended that the Soviet

political economy was “state capitalism" while Paul Sweezy

and Charles Bettelheim (1975) argued that that the Soviet Union and China were

transitional forms between socialism and capitalism. Alternatively, Christopher

Chase-Dunn (1980) claimed that the existing socialist states in which communist

parties held state power had become functional parts of the larger capitalist

world-economy that played an important supportive role in the reproduction of the

global system. He argued that the semiperipheral Soviet Union had mobilized

autarchic national development, industrializing the national economy and

attempting to be upwardly mobile within the global system. Chase-Dunn contended

that this was a version of semiperipheral development not entirely dissimilar

to the developmental path that had been taken by earlier semiperipheral

challengers. But did the communist states constitute a separate socialist

world-system as argued by Szymanski? Indeed, there had been a substantial political-economic

interaction within the communist bloc and relatively autonomous centrally

planned industrialization. But the heavy geopolitical and military competition

within the global system of states was an important constraint on the Soviet

efforts to construct socialism, and in the end it was the huge expenditures on

arms at the expense of consumer goods that brought the Soviet regime down.

Despite

a significant cooperation within the bloc, socialist states were affected by

global geopolitics and their economies were influenced by the world market.

They remained functional parts of the global capitalist system. The Yalta

agreements after World War II cemented the post-war borders and implied

ideological condemnation, so the struggle between the so-called Communist and

Free Worlds permitted a tight internal control within each camp (Wallerstein

1992). In 1970s and the 1980s scholars observed that the socialist states were

becoming reintegrated into the capitalist world economy by growing East-West

trade and efforts to keep up with the West with regard to consumer products (Derluguian 2005, Frank 1980). The these trends were

subsequently confirmed by the collapse of the Soviet Union, the entrance of the

Eastern European states into the European Union and NATO, Chinese neoliberal

reforms, as well as diplomatic and touristic openings.

Some

have claimed that the world-system perspective overemphasizes political economy

and structure over agency. Wallerstein has responded to this criticism by

focusing his most recent work on “geoculture”, by

which he means the evolution of the political ideology of liberalism in the 19th

century (Wallerstein 2011b). Arrighi, Hopkins and

Wallerstein (2011[1989]) have also focused on “world revolutions” –

constellations of rebellions and transnational social movements – that have

driven the evolution of global governance institutions for centuries.

World-System

Structures

Fernand

Braudel viewed the ascendance of world cities as

constitutive centers of capitalist world-economies (1992: 26-35). Later, Saskia Sassen (2000: 1-4) explicated the interconnectedness and

hierarchy of global cities, and their central role in the contemporary world

economy. They serve as central locations for international transactions – containers

of industry and physical infrastructure and highly concentrated business

districts and banking centers).

The

political dimension of the modern world-system has been constituted as a system

of states are connected by trade, alliances and completion within a coherent

interstate system. The interstate system is composed of unequally powerful

nation states that compete for resources by supporting profitable commodity

production and by engaging in geopolitical and military competition (Chase-Dunn

1998: 49). Nevertheless geopolitics is

not just an anarchic competition for power.

A semblance of global order has been provided by the sequential rise and

fall of hegemonic core powers. This governance by hegemony and continues to be

the strongest institutional element in the contemporary world-system though it

has become imbricated within a dense matric of international organizations.

Hegemony

is one of the central concepts of the world-system perspective. Chase-Dunn (1998:50) explicates the idea of

the hegemonic sequence as follows “The hegemonic sequence… refers to a

fluctuation of hegemony versus multicentricity in the

distribution of military power and economic competitive advantage in production

among core states. ” Hegemony in the interstate system occurs during a time period, “in which the ongoing rivalry

between the so-called "great powers" is so unbalanced that one power

can largely impose its rules and its wishes… in the economic, political,

military, diplomatic, and even cultural arenas” (Wallerstein 2000: 255). While

Antonio Gramsci’s notion of hegemony refers to ideological class domination

within national societies, Immanuel Wallerstein’s concept of hegemony refers to

the concentration of power in the world-system. According to Wallerstein, the

United Provinces of the Netherlands was the first hegemon during the 17th

century, and it was followed by the United Kingdom of Great Britain in the 19th

century which was followed by the United States of America in the 20th

century. [7]

According to Immanuel Wallerstein, hegemony is based on advantages in three

critical economic domains: agro-industrial, commercial, and financial (2000:

256). For instance, Great Britain first intensified its agricultural

production, then developed its industry, followed by extensive overseas trade

and financial operations, establishing pound sterling as world money, dominated

militarily, and only later enjoyed language, educational, tourist and other

cultural benefits. Elaborating on Wallerstein’s conception of hegemony, we

would suggest a more comprehensive list of its aspects: technological-economic

(technological, production, commercial, and financial), military-political

(military, political, and diplomatic), socio-cultural (institutional,

normative, and cultural).

Both

Wallerstein and Arrighi note that each hegemony (or

what Arrighi calls “systemic cycles of accumulation”)

develops in a sequence of similar stages. The first stage is based on the successful

production and export of consumer goods. The second stage is based on capital

goods. And the third stage is based on the advantages that the hegemon has

accrued as a center of global trade and finance. Financial services and control

of world money are the key to the last stage. As leading technologies spread

out, production and other economic advantages are lost. Eventually military

capability is reduced as well as remaining socio-cultural benefits. According

to Giovanni Arrighi and Beverly Silver (1999: 29, the

hegemonic crisis is marked by an increase of competition, social conflicts and

the emergence of systemic chaos. States and elites group around the contenders

for a new round of hegemony. The system systems heads back into an inter-regnum

in which interimperial rivalry heightens the probably

of world war (Bornschier and Chase-Dunn 2012; Klare 2016).

The

Modern Core/Periphery Hierarchy

Based

on historical studies of medieval Europe Fernand Braudel

outlined a pattern of the concentration of wealth and resources in particular

sites of accumulation at the expense of other regions (1992: 35-38). As we have

said, a fundamental organizing principle of the modern world-system is the

structural hierarchy composed of the core, the semiperiphery and the periphery.

Core areas specialize in core production – relatively capital intensive

production utilizing skilled, high wage labor. Peripheral areas contain mostly

peripheral production – labor intensive, low wage and unskilled labor (Chase-Dunn

1998: 49). The core/periphery relationship was brought into existence by extraeconomic plunder, conquest, and colonialism, and is

sustained by the normal operation of political-military and economic

competition in the capitalist world-economy (Chase-Dunn 1998: 39). Core

production is controlled by quasi-monopolies and is thus more profitable,

whereas peripheral production is truly competitive and hence less profitable. In

the process of global trade monopolized products from the core are in a

stronger position than competitive products from periphery. This results in a

flow of surplus-value from the periphery to the core – unequal exchange

(Wallerstein 2004: 28).

The

semiperiphery is characterized by a rough balance of core and peripheral

production. The semiperiphery mediates the surplus extraction from periphery to

the core, and serves as a buffer zone between the two hierarchical components

of the world-system, providing an ideological fig leaf by holding out the

possibility of “development” for the non-core.

Salvatore

Babones (2005) has conducted a vivid quantitative

estimation of the structural positions of nation-states in the modern

world-system. Applying GDP per capita measurements to the 1975-2002 cross

national data panel, he concluded that 25 countries (33.8%) were organic to the

core, 14 counties (18.1%) – were organic to the semiperiphery, and 35 countries

(48.1%) – were organic to the periphery. Eighteen countries (24.3%)

demonstrated inter-zonal mobility, but exactly half of them moved downward and half

moved upward. The main finding is that the three zones are strikingly stable

over time (see Figure 5).

Figure

5: The contemporary global core/periphery hierarchy

The

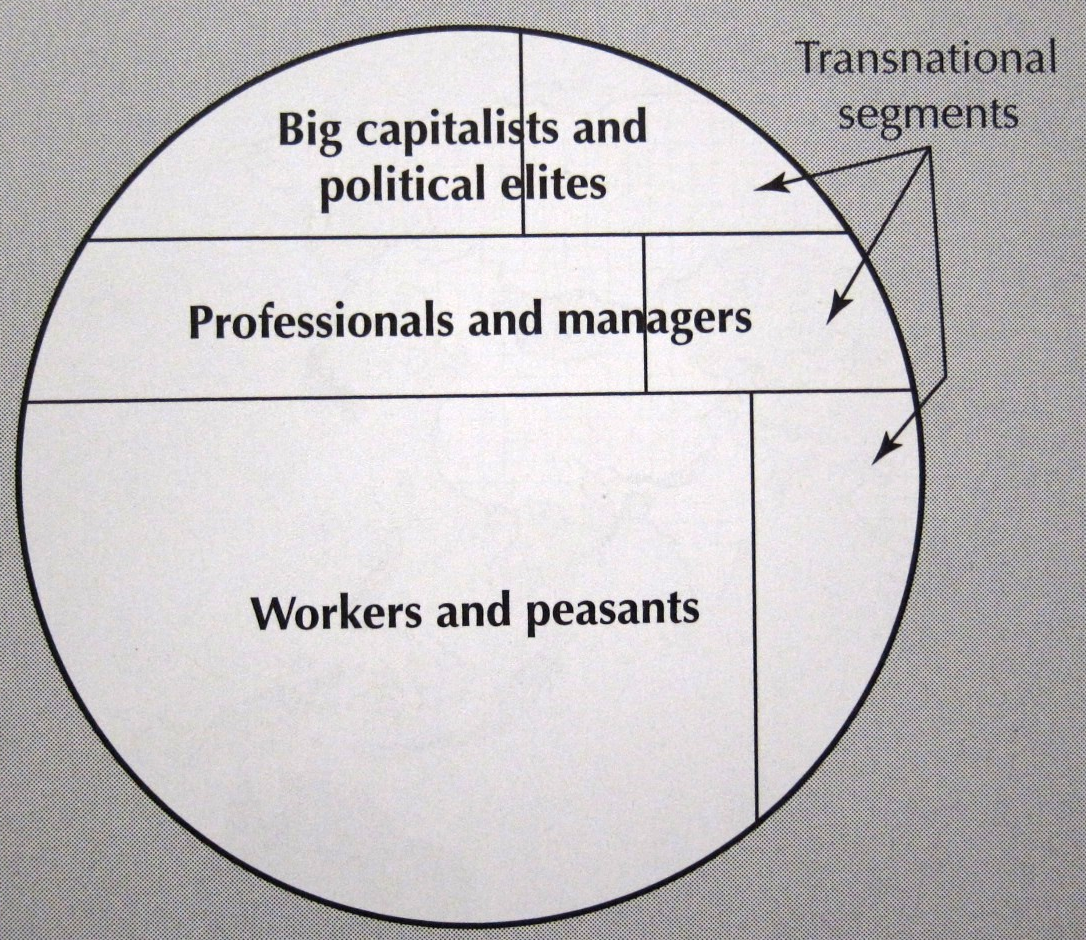

“global capitalism” school has emphasized the interconnectedness of elites into

a global network (Carroll 2010, Robinson

2014). Leslie Sklair (1995: 71) argues that there is

a transnational capitalist class comprised of corporate executives, state

bureaucrats, neoliberal politicians and professionals from many countries. William

Robinson (2014: 8) explains the mechanisms by which the transnational

capitalist class can influence governments – competition among national states

to attract transnationally mobile capital provides structural power of

capitalists over states. Robinson also theorizes an emerging global class

structure in which transnationalized segments of

different classes exist in within countries in the emerging global society (see

Figure 6). And he contends that a transnational state has emerged in which

existing state structures act as agents of the transnational capitalist class.

The world-system scholars have noted that there

has long been a global class structure in the sense of objective class

membership. Samir Amin (1980b) analyzed the global class structure prior to the

emergence of the global capitalism school. Guy Standing’s designation of the

emergence of a

global precariat acknowledges that the class situation of most workers in the non-core has always been precarious (Standing 2011).

Figure 6: The global class structure with transnational

segments (based on Robinson 2014).

There

has been a great debate among social scientists regarding trends in global

wealth and income inequality. Many contend that, due to the rising household

incomes in China and India, global inequality has decreased, while others contend

that global economic inequality has increased during recent decades. Both within-county and between-country inequality trends

need to be taken into account in order to know the true overall trend in income

distribution for the whole population of the Earth. And there are difficult

issues regarding the conversion of national currencies into a single global

metric (usually U.S. dollars). A conservative estimate based on the

contentious quantitative literature on trends in global income inequality is

that global inequality increased greatly during the 19th century and it has remained at about

the same high level or possibly decreased slightly since then (Bornschier 2010). Though the magnitude of

global income inequality expanded in the 19th century, there were already important

amounts of political inequality that had emerged between the core and the

periphery as a result of European colonialism. And these structures were both

outcomes of, and causes of, resistance and rebellions that occurred within the

European core and in the colonized regions.

The

cycle of world war severity has had a 40- to 60-year period (Chase-Dunn 1998:

51). Hegemony and resistance have co-evolved and this tension has been a major

factor in structuring world historical social change. Resistance and rebellions

by subordinate classes and in the non-core have tended to cluster together in

time as the contradictions of power, domination and exploitation have produced

somewhat similar conditions in regions that are distant from one another (Chase-Dunn

and Khutkyy 2016). Even though the non-core

rebellions and resistance movements were not very directly connected with one

another in earlier centuries, their synchronous consequences converged on the

core states, and especially on the hegemon. This phenomenon of widespread

synchronous resistance and rebellion is termed “world revolution.” World

revolutions have become much more directly interconnected as social movements

have become increasingly transnational, and popular groups and global parties

have emerged to engage in politics on a global scale. Wars and revolutions

periodically reset the rules of international politics and the global economy resulting

in a spiral of capitalism and socialism (Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000).

One

important long term trend has been the increased size of the hegemons: from the

Italian city-states to the United Provinces of the Netherlands to the United

Kingdom of Great Britain to the continent-wide United States. In order for this

trend of increasing scale to continue the next hegemon would need to be either an

alliance of states or a federal world state.

Structural

Continuities and Possible Futures

In

1970s the world-system entered another period of economic stagnation: core

states witnessed a decline of profits in manufacturing as Germany and Japan

caught up with the U.S., producing global overcapacity relative to effective

demand. Many industries began relocating to the noncore where there were lower

wages and fewer regulations. Economic growth slowed down and there was a shift

of investments from production to financial speculation. The United States lost

a major war against Vietnam and economic challengers emerged from the non-core

(Wallerstein 2006). This was the beginning of the end of U.S. hegemony. But since

United States domestic economy was such a large portion of the global economy

and the U.S. global military apparatus was so huge, the decline of the U.S. has

been gradual.

The

U.S. domestic economy was 35% of world GDP in 1945 and there were 737 U.S. military

bases all over the world in 2011 (Chase-Dunn et al 2011: 7). The United States has lost much of its predominance

in manufacturing and in world trade to China. But its continued predominance in

global financial services and its ability to print world money (what Michael

Mann 2002; 2006) has called dollar seigniorage) cannot

last forever. Global financial centrality and dollar seigniorage

have allowed the U.S. to engage in unilateral military engagements without

having to raise taxes. Another global financial debacle along the lines of what

happened in 2008 may bring the bubble down.

An

alternative to U.S. hegemonic decline would be a second round of U.S. hegemony.

Recall that Modelski and Thompson (1996) contended

that Great Britain enjoyed two “power cycles.” The United States still has,

despite the depredations of neoliberal austerity, comparative advantages in

higher education and research. It continues to lead in technological

innovations in biotechnology, green technology and nanotechnology and to have a

relatively flexible institutional structure. These features suggest that another

round of hegemony for the U.S. is a possibility. But iIn

order for this to happen there would have to be a serious and sustained effort

by the federal government and state governments that was supported by a significant

contingent of the U.S. capitalist class. This seems unlikely. And so the 21st

century world is moving toward multipolarity with intensified

political and economic rivalry among strong contenders. Military rivalry is

also likely to emerge as the U.S. loses its advantages in the global financial

system and so has to tax its own citizens in order to fund the global military

apparatus.[8]

Michael Klare’s (2016) report that big wars are back

on the drawing boards of military strategists because of Russian intransigence

reveals more about the institutional resilience of the war machine than it does

about the current geomilitary situation. Russia is in

no position to challenge NATO or the U.S. militarily at present. But that

situation is likely to change as the costs of the U.S. monopoly on military

capability can no longer be sustained by dollar seignorage.

Wallerstein

(2011: 35) contends that the capitalist world-system has been experiencing a

systemic crisis since 1970s. This crisis is characterized chaotic fluctuations

that will lead to either systemic revival or to collapse. Wallerstein argues

that the world revolution of 1968 was a decisive turning point that marked the

end of the supremacy of centrist liberal ideology, disassembling the global geoculture that fused the political institutions of the

world-system (Wallerstein 2004: 77). Student, civil rights and anti-war

protests in the big cities of the U.S., Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, the United Kingdom,

France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Yugoslavia, Poland, Czechoslovakia and China shook

both capitalist and socialist states. They indicated mass discontent with

social inequalities and political coercion and manifested demands for a more

just social order. Though these movements were repressed and did not transform

the world-system, they initiated processes that brought more civil rights to

some segments of population. The protests of 1989-1991 in the USSR were based

on socio-economic demands from blue-collar and white-collar proletarians that,

faced with weakness and unresponsiveness of central authorities, sought

expression on movements for civil rights (Derluguian

2005). The Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 were a similar incarnation of

civil rights demands. The latest major protests of 2010-2012, commonly called “the

Arab Spring”, occurred in Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan,

Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria,

Tunisia, Western Sahara,and Yemen. These were

constellations of local, national, and transnational protest movements that were

united by similar agendas and signified opposition to oppressive national and

global governance.

Wallerstein

(2004) notes that capitalism is reaching assymtotes

based on the costs of labor, taxation and raw materials. Capitalists are

experiencing pressures to internalize previously externalized costs. Wages are

going up as global proletarianization labor movements

in the non-core continue to emerge (Silver 2003). Capitalist who employ the “spatial fix” by

outsourcing, moving production from the

core to the periphery find that there are fewer and fewer places with cheap,

disciplined and skilled labor, low ecological standards, cheap raw materials,

low taxation levels and modest welfare expectations. Formerly profitable

production in China, India, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan is

becoming more expensive, as local workers demand higher wages.

We

agree with Michael Mann’s (2013) point that the global capitalism school, which

he calls “hyperglobalists”, often overemphasizes the extent to which the

nation-state has been transcended or repurposed by global capitalism. But we do

not agree with Mann’s contention that contingency and the loose coupling of

political, ideological, military and economic trajectories of development mean

that there is no such thing as a single global system. While human history is

undoubtedly somewhat open ended because social change is a complex and

contingent outcome of accidents and contentious intentions, this does not mean

that there is no global system. Nor does it mean that the future is completely

unpredictable. Demographic trends are relatively certain. And some of the

possible 21st century futures are far more probable than others.

Mann

and those world historians who emphasize contingency and open-endedness are protagonists

of a hyperhumanism, in which both individuals and

organizations are deemed capable of, and are expected to, author themselves and

their destinies. While we also value the human species, individual lives and

collective freedoms, these values do not blind us to the existence of

structural and institutional forces that condition the possible human futures

of the 21st century. And as social scientists we are duty bound to

report upon and dissect the predominant cultural values of our own global

society as well as the moral orders of the past. We are not determinists, but

we agree with Marx that the institutions that past humans have created strongly

act upon and condition the possibilities for the humans of the present and the

future. Understanding these constraints is a strong medicine that will be of

great use to the struggle for a better future.

Bibliography

Amin, S. 1980a Class

and Nation, Historically and in the Current Crisis. New York: Monthly

Review Press.

Amin, S. 1980b

“The class structure of the contemporary imperialist system.” Monthly

Review 31,8:9-26.

Arrighi, G. 2010[1994] The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power,

and the Origins of Our Time. London:

Verso.

Arrighi, G., & B. J.

Silver 1999 ‘Introduction’, In Arrighi, G., Silver,

B.J., et al, Chaos and Governance in the Modern World-System. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press. Pp. 1-36.

Arrighi, G., & T. K. Hopkins, & I. Wallerstein.

2011 [1989] Antisystemic Movements.

London and New York: Verso.

Babones, S. J. 2005 “The

Country-Level Income Structure of the World-Economy” Journal of World-

Systems

Research, 11,

29-55. Retrieved April 8, 2015 from http://www.jwsr.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/jwsr-v11n1-babones.pdf

Beckwith,

C. I. 2009 Empires of the Silk Road: A

History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the

Present. Princeton: Princeton

University Press.

Bornschier, V. 2010 “On the evolution of inequality in the

world system” Pp. 39-64 in

Christian Suter (ed.) Inequality Beyond Globalization:

Economic Changes, Social

Transformations

and the Dynamics of Inequality. Zurich: LIT Verlag

Bornschier, V. and C. Chase-Dunn (eds.)

2012 The Future of Global Conflict.

London: Sage.

Boswell,

T., & C. Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral

of Capitalism and Socialism: Toward Global Democracy.

Boulder: Lynne Reinner

Publishers, 2000.

Braudel, F. 1992 Civilization and Capitalism, 15th – 18th

Century. Vol. 3: The Perspective of the World.

Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Bunker, S., & and P. Ciccantell

2005 Globalization and the Race for Resources. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Carroll,

W. K. 2010 The Making of a Transnational Capitalist Class: Corporate Power in the

Twenty-First Century. London: Zed Books.

Chase-Dunn,

C. K. 1980 Socialist States in the

Capitalist World-Economy. Social

Problems, 27, 505-525.

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1998 Global Formation. Structures of

the World-Economy. 2nd Ed. Boston: Rowman and

Littlefield Publishers.

Chase-Dunn,

C. & T. D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise:

Comparing World-Systems. Boulder: Westview

Press.

Chase-Dunn. C., & T.

D. Hall 2000 "Paradigms Bridged: Institutional

Materialism and

World-Systemic

Evolution," in Sing Chew and David Knottnerus

(eds.) Structure, Culture, and

History Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield

Chase-Dunn C., & K. M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and Their Neighbors: A Small

World-System in

Northern

California Tucson: University of Arizona Press

Chase-Dunn, C., and D. Khutkyy 2016 ‘The Evolution of Geopolitics and Imperialism

in Interpolity Systems.’ in The Oxford

World History of Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chase-Dunn, C., Kwon, R.,

Lawrence, K., & Inoue, H. 2011 “Last of the Hegemons: U.S. Decline and

Global Governance” International Review

of Modern Sociology, 37, 1-29.

Chase-Dunn, C., & B.

Lerro 2014 Social

Change: Globalization from the Stone Age till Present. Boulder: Paradigm

Publishers.

Cliff, T. 1974 State Capitalism in Russia. London:

Pluto Press.

Derluguian, G.M. 2005 Bourdieu's Secret Admirer in the Caucasus: A

World-System Biography. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ekholm, K., & J. Friedman 1982

“’Capital’ imperialism and exploitation in the ancient world-systems” Review 6:1

(summer): 87-110.

Frank, A. G. 1966. "The Development of

Underdevelopment." Monthly Review September:17-31. [Republished

in 1988, reprinted 1969 pp. 3-17 in Latin America: Underdevelopment or

Revolution, edited by A. G. Frank. New York: Monthly Review Press.]

Frank, A. G. 1967 Capitalism and underdevelopment in

Latin America. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Frank, A.G. 1969 Latin America: Underdevelopment or

revolution? New York: Monthly Review Press

Frank, A. G. 1978 World Accumulation, 1492-1789 New

York: Monthly Review

Press.

Frank, A.

G. 1980 Crisis: In the World Economy.

New York: Holmes & Meier.

Frank, A.

G., & Gills, B. K. (Eds.). 1993 The 5,000-Year World System: An

Interdisciplinary Introduction” In A.G. Frank and B.K. Gills, Eds. The World System: Five Hundred Years or Five

Thousand? London: Routledge. Pp. 3-55.

Harvey, D.

2014 Seventeen Contradictions and the End

of Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inoue, H., A. Álvarez, K. Lawrence, A. Roberts, E. N. Anderson, & C. Chase-Dunn 2012 “Polity scale

shifts in world-systems since the Bronze Age: A comparative inventory of

upsweeps and collapses” International Journal of Comparative Sociology June 53 (3): 210-229 http://cos.sagepub.com/content/53/3/210.full.pdf+html

Inoue, H., Alvarez, A.,

Anderson, E. N., Lawrence, K., Neal, T., Khutkyy, D.,

Nagy, S., & Chase-Dunn, K. 2016 “Comparing World-Systems: Empire Upsweeps

and Noncore Marcher States Since the Bronze Age” IROWS Working Paper #56,

IROWS, University of California-Riverside. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows56/irows56.htm

Klare, M. T. 2016

“Sleepwalking into a big war” Le Monde Diplomatique (September)

http://mondediplo.com/2016/09/02war#tout-en-haut

Korotayev, A., Goldstone, J. A.,

& Zinkina, J. (2015). Phases of global

demographic transition correlate with phases of the Great Divergence and Great

Convergence. Technological Forecasting

& Social Change. Retrieved March 20, 2015 from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162515000244

Lenski, G. 2005 Ecological-Evolutionary Theory: Principles

and Applications. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

Mann, M. 2002

Incoherent Empire. New York, NY: Verso.

Mann, M. 2006 “The Recent Intensification of American Economic and

Military Imperialism:

Are They

Connected? Presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological

Association, Montreal, August 11.

Mann, M.

2013 The Sources of Social Power. Vol. 4:

Globalizations, 1945-2011. Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press.

Mann, M.

2016 “Have human societies evolved? Evidence from history and pre-history” Theory and

Society 45:203-237.

Modelski, G. 2003 World

Cities: -3000 to 2000. Washington, DC: FAROS2000.

Modelski, G., & W. R. Thompson

1988 Seapower in Global Politics, 1494-1993. Seattle:

University of

Washington Press.

Modelski, G., & W. R.

Thompson 1996 Leading Sectors and World

Powers: The Coevolution of Global Politics and Economics. Columbia, SC: University

of South Carolina Press.

Patomaki, H. 2008 The

Political Economy of Global Security War Future Crises and Changes in Global

Governance. London: Routledge.

Robinson,

W. I. 2014 Global Capitalism and the

Crisis of Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Sanderson, S. K. 1990 Social

Evolutionism. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Sassen, S. 2000 Cities in a World Economy. 2nd Ed.

Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

Silver, Beverly J. 2003 Forces of labor : workers'

movements and globalization since 1870

Sklair, L. 1995 Sociology of the Global System. 2nd Ed.

Prentice Hall: London.

Standing,

G. 2011 The Precariat. London:

Bloomsbury

Sweezy, P., & Bettelheim,

C. 1975 On the Transition to Socialism.

New York: Monthly Review Press.

Szymanski,

A. 1975 Is the Red Flag Flying?: The

Political Economy of the Soviet Union in the World Today.

London: Zed Press.

Wallerstein,

I. 1992 “America and the World: Today, Yesterday, and Tomorrow” Theory and Society

21,

1-28

Wallerstein,

I. 2000 The Essential Wallerstein,

New York: The New Press.

Wallerstein,

I. 2006 The Curve of American Power. New

Left Review, 40, 77-94.

Wallerstein,

I. 2004 World-Systems Analysis: An

Introduction. London: Duke University Press.

Wallerstein,

I. 2011a [1974] The

Modern World-System, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Wallerstein,

I. 2011b Structural Crisis in the World-System Where Do We Go from Here? Monthly

Review, 62, 31-39.

Wallerstein,

I. 2011c The

Modern World-System IV: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789-1914 Berkeley:

University of

California Press.

Wilkinson, D. 1986 “Central Civilization,” 17 Comparative Civilizations Review (Fall), pp. 31-59.