The SETPOL

Framework:

Settlements

and polities

in World-Systems

Artist’s conception of the

Cothon, the military harbor of Carthage

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Hiroko Inoue, Eugene Anderson and David

Wilkinson

v. 1-31-17, 15995 words

This is IROWS Working Paper

#116 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows116/irows116.htm

Institute for Research on World-Systems, University of California

Riverside

![]()

*Thanks

to Andrew Jorgenson and Thomas Hall for help in developing the ideas in this article.

This article presents the interdisciplinary framework

developed by the SetPol Working Research Group at the University of

California-Riverside for studying sociocultural evolution of complexity and hierarchy

by comparing world-systems. By focusing on the population sizes of settlements

and the territorial sizes of polities[1] we

can pinpoint those periods in which the scale of sociocultural systems were

significantly changing based on relatively simple and knowable quantitative

criteria. Human social organization and interaction

networks have expanded over the long run, but in the medium-run there have been

cycles of rise and fall and occasional upward sweeps and collapses. It is the upward sweeps that account for the

long-term upward trends toward larger cities and polities, and so specifying

when and where the upward sweeps occurred and examining their causes will help

to explain the long-term trend.[2]

This project should include all the

local, regional and intercontinental human interaction networks, including both

nomadic and sedentary world-systems,[3]

though in practice it is necessary to limit ourselves to those regions in which

fairly reliable and frequent estimates of the quantitative sizes of largest

polities and settlements are available.

We focus on the territorial sizes of polities and the population sizes of

settlements because these are relatively easily ascertainable quantitative

indicators of system size and complexity and they allow us to differentiate

between cycles and upsweeps. We need to have an interval scale metric in order

to tell the difference between small and large changes. When human sociocultural systems are studied

over long periods of time we usually find cyclical processes of population

growth and decline, the rise and fall of large and strong polities, etc. Our research needs to be able to tell the difference

between a “normal” upswing or downswing in which a feature of sociocultural

organization is fluctuating around an equilibrium level and a acale change event

of growth or decline that is larger than the “normal” fluctuations. We focus on

the largest settlements and polities in each region rather than on individual

settlements or polities. The size of the

largest settlement or polity are understood to be characteristics of each

regional world-system that vary over time. We identify those instances in which

there have been large increases or decreases in these system-wide

characteristics.[4]

A very long debate has waxed and

waned over how to best bound sociocultural systems in time and space for

purposes of explaining the emergence of complexity and hierarchy in human

societies (e.g. Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997; Mann 1986; Tilly 1984; Wallerstein

1974). Our theoretical approach is what we call institutional materialism: an

interdisciplinary approach that combines focusing on the historical emergence

and development of humanly constructed institutions (language, kinship,

production technology, states, money, markets, etc.) and the changing ways that

humans interact with their biological and physical environment. This

theoretical framework deploys what has been called the comparative

world-systems approach to spatially and temporally bounding human sociocultural

systems. Rather than comparing societies

with one another, we compare systems of interacting human polities (or

interpolity systems) and these are empirically bounded in space and time as

interaction networks—multilateral regularized exchanges of materials,

obligations, threats, ideas and information.

World-systems experience oscillations

of expansion and contraction, with occasional large expansions that bring

formerly separate regional systems into systemic intercourse with one another.

These waves of expanded integration, now called globalization, have, in the

last two centuries, created a single linked intercontinental political-economy

in which all national societies are strongly connected. But all earlier regional interaction networks

also experienced expansions and contractions of trade. Archaeological studies

of obsidian and shell exchange show these oscillations even among very

small-scale polities in many regions (e.g. Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998).

As Tilly (1984) has emphasized,

societies (defined as communities that share a common language and culture) are

messy entities when we consider interaction networks. Many of the networks in

which households are deeply involved are local, while many other important

interactions strongly link the inhabitants of many different societies to one

another. The world-systems perspective has argued that societies are subsystems within a larger system, and that in

order to understand historical development we must focus on the larger system

as a whole. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) have developed a nested network approach

for spatially bounding world-systems that enables the comparison of the modern

global system with earlier, smaller regional world-systems. They contend that

the world-system rather than single polities is the most important unit of

analysis for explaining long-term social change because interpolity conflict

and cooperation are very important sources of the selection pressures that

cause sociocultural development. In this essay we explain this nested network

approach to spatially bounding world-systems and we propose a practical

research design for studying the emergence of larger and larger interaction

networks that uses expanding network as the unit of analysis.

One problem with regional

analysis is the effort to define regions in terms of homogenous sociocultural

attributes. Thus, comparative civilizationists have mainly focused on the main

cultural characteristics that are embodied in religions or institutionalized

world-views and have tended to construct lists of such culturally defined

civilizations that then become the “cases” for the study of social change (e.g.

Toynbee 1947-57). The problem here is that most interactive sociocultural

systems are multicultural, and religious ideologies interact with one another,

both diffusing attributes to one another and reactively developing

distinctions. So the effort to spatially bound systems based on religious

beliefs or other ideological characteristics does not produce regions that are

autonomous from one another.

The “culture area” approach developed by

geographer Carl Sauer and used widely by ethnographers and archaeologists tries

to define regions as areas with homogenous contiguous characteristics (e.g.

Wissler 1927). The culture area project gathered and coded valuable information

on all sorts of cultural attributes such as languages, architectural styles,

technologies of production, and kinship structures, and used these to designate

bounded and adjacent “culture areas.”

A major problem with both the

civilizationist and the cultural area approaches is the assumption that

homogeneity is a good approach to spatially bounding social systems for purposes

of explaining social change. Heterogeneity rather than homogeneity has long

been an important aspect of human social systems because different kinds of

groups often complement one another and interaction

often produces differentiation rather than similarity. The effort to bound systems as homogeneous

regions obscures this important fact. Spatial distributions of homogeneous

characteristics do not bound separate social systems. Examples in which social

heterogeneity was produced by interaction include core/periphery

differentiation, urban/rural, and sedentary/nomadic systems. Owen Lattimore’s

(1940) classic, Inner Asian Frontiers of

China, shows how Central Asian diversified foragers evolved to become

specialized steppe pastoralists because of their interactions with farmers

along the ecological boundary between steppe and loess. The farmer/pastoralist interaction was a

powerful source of social change among Bronze and Iron Age societies for millennia

(e.g. Barfield 1989). And the interaction

between farmers and fishing populations led to the emergence of maritime

polities that specialized in naval power and sea-borne trade such as Dilmun

(Bahrein) in the Arabian/Persian Gulf (Tosi 1986), perhaps the first semiperipheral capitalist

city-state carrying goods between the Indus Valley civilization and Mesopotamia

in the Bronze Age. Bounding regions based on homogenous attributes completely

ignores important interactions among different kinds of societies.

Anthropologists and geographers have

developed complicated multidimensional approaches that examine distributions of

many spatial characteristics statistically (e.g.

Another important point is worth

making regarding the relationship between natural ecological regions (biomes)

and human interaction networks. Biomes are regions that are defined on the

basis of soil type, climate, characteristic plants and animals, etc. The

relationship between human social structures and the natural world is obviously

important, as stressed by cultural ecologists. Comparative research has

demonstrated that empires are more likely to expand into regions that are

ecologically similar to the home region, and so they are more likely to be wide

than to be tall (to expand in the East/West plane rather than North/South

(Turchin, Adams and Hall 2006). Cultural

ecology stresses the important ways in which local ecological factors

conditioned sociocultural institutions and modes of living. This has been an

especially compelling perspective for understanding small-scale systems in

which people were mainly interacting with adjacent neighbors not very far away.

But this kind of local ecological determinism is much less compelling when

world-systems get larger because long-distance interaction networks and the

development of larger scale technologies enable people to impose socially

constructed logics on local ecologies and to convert biomes into “anthroms” –

regions in which the ecology has been radically altered by the intervention of

humans (Ellis et al 2010). Some

social evolutionists have interpreted this to mean that social institutions

have become progressively less ecologically constrained (Lenski, Lenski, and

Nolan 1995). But what has happened instead is that the spatial scale of

ecological constraints has grown to the point where they are operating globally

rather than locally (Chase-Dunn and Hall 2006).

Spatially Bounding World-Systems

The world-systems perspective

originally emerged as a theoretical approach for explaining the expansion and

deepening of the modern Europe-centered system as it engulfed the globe over

the past 500 years (Arrighi 1994; Chase-Dunn 1998; Wallerstein 1974). The idea

of a core/periphery hierarchy composed of “advanced,” economically developed,

and powerful states dominating and exploiting “less developed” peripheral

regions has been a central concept in the world-systems perspective. In the

last two decades the world-systems approach has been extended to the analysis

of earlier interpolity systems. Andre Gunder Frank and Barry Gills (1993) have

argued that the contemporary world system is a continuation of a 5000-year old

system that emerged with the first states and cities in

The comparative world-systems

perspective is designed to be general enough to allow comparisons between quite

different systems. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) defined world-systems as

important networks of interaction that impinge upon a local society and

condition social reproduction and social change. They note that different kinds

of interaction often have distinct spatial characteristics and degrees of

importance in different kinds of systems. And they hold that the question of

the nature and degree of systemic interaction between two locales is prior to

the question of core/periphery relations. Indeed, they make the existence of core/periphery relations an empirical

question in each case, rather than an assumed characteristic of all

world-systems.

Part of Chase-Dunn and Hall’s claim

that world-system networks are the most important unit analysis for explaining

sociocultural development is based on the hypothesis of semiperipheral

development. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997, Chapter 5) contend that semiperipheral

regions within core/periphery hierarchies have been fertile locations for the implementation

of new technologies of power, and that

semiperipheral polities have played and continue to play important roles in the transformation of

world-systems. Of course semiperipherality is a relational concept that depends

on the nature of the larger system.

Semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms were often the agents of the formation

of larger paramount chiefdomships by conquest (Kirch 1984) and semiperipheral

marcher states have frequently been the founders of large core-wide empires

that accounted for upsweeps in polity size. Semiperipheral capitalist

city-states in the interstices between tributary states and empires were agents

of commodification that expanded trade networks in the Bronze and Iron Ages,

and more recently. The phenomenon of semiperipheral development is the main

force behind the movement in space of the cutting edge of complexity and

hierarchy in human social change. It has mainly been societies out on the edge

of older core regions that rewire the networks and expand the polities.

Spatially bounding world-systems

must necessarily proceed from a locale-centric beginning rather than from a

whole-system focus. This is because all human societies, even nomadic

hunter-gatherers, interact importantly with neighboring societies. Thus, if we

consider all indirect interactions to be of systemic importance (even very

indirect ones) then there has been a single, global world-system since

humankind spread to all the continents. But interaction networks, while they

always linked polities that were near to one another, have not always been

global in the sense that actions in one region had important and relatively

quick effects on very distant regions. When transportation and communication

occurred only over short distances world-systems were small. Thus the word

“world” refers to the network of interactions that impinge on any focal locale.

It is necessary to use the notion of

“fall-off” of effects over space (Renfrew 1977) to bound the networks of

interaction that importantly impinge upon any point of origin. The world-system

of which any locality is a part includes those peoples whose actions in

production, communication, warfare, alliance, and trade have a large and

interactive impact on that locality.

This

method of bounding systems is “place-centric.” It is also important to

distinguish between endogenous systemic interaction processes and exogenous

impacts that may change a system, but are not part of that system. Sweet

potatoes somehow got from South America to the

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) note that

in most intersocietal systems there are several important networks with

different spatial scales that impinge upon any particular locale:

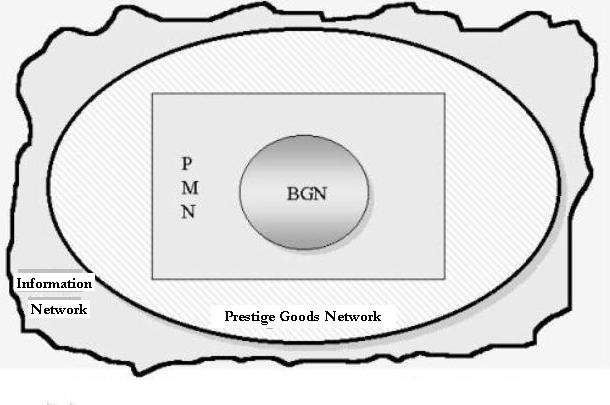

Information

Networks (INs)

Prestige

Goods Networks (PGNs)

Political/Military

Networks (PMNs) and

Bulk

Goods Networks (BGNs).

The largest networks are those in which information and

ideas travel. Information is light and it travels a long way, even in systems

based on down-the-line interaction.[6]

These are termed Information Networks (INs).

A usually somewhat smaller interaction network is based on the exchange of

prestige goods or luxuries that have a high value/weight ratio. Such goods

travel far, even in down-the-line systems. These are called Prestige Goods

Networks (PGNs). The next

largest interaction net is composed of polities that are allying or making war

with one another. These are called Political/Military Networks (PMNs). [7]And

the smallest networks are those based on a division of labor in the production

of basic everyday necessities such a food and raw materials. These are Bulk

Goods Networks (BGNs). Figure 1

illustrates how these interaction networks are spatially related in most

world-systems.

World-systems

vary in the degree to which these different kinds of interaction are systemic –

have important impacts on local sociocultural reproduction and social change.

In all systems the Bulk Goods Network (BGN) and the Political-Military Network

(PMN) are systemic. But the Prestige Goods Network varies across systems in

both the ways it may be systemic and the extent to which it is important for

sociocultural reproduction and social change. And the same may be said of the

Information Network (IN).

Immanuel Wallerstein (1974) defined

core/periphery relations in the modern world-system in terms of a hierarchical division of labor

in the production of necessities between different polities or regions. This is

the BGN. In world-system comparative perspective the BGN may or may not be

hierarchical in the sense of unequal exchange in different systems, but it is

always systemic because it is important for reproducing local households and

communities. Political-military interactions among polities (alliances and

warfare) may or may not correspond spatially with the Bulk Goods Network,

though the assumption that polities do not trade or intermarry with their traditional

enemies is often false.

Anthropologists have long noticed

the importance of prestige goods when they are used by elites to reward

subalterns and to control marriage (Sahlins 1972 ; Eckholm and Friedman 1982

; Peregrine 1992 ) And Jane Schneider (1991 ) claimed that, contra Wallerstein, prestige goods flows

across the Silk Roads had played an important role in the development of the

core regions of Eurasia as well. Mary

Helms (1988) has emphasized the importance of exotic ideas as well as goods in

the emergence of theocratic chiefdoms and early states. A study of a very small world-system in

Figure

1: Nested Interaction Networks

The first question for any locale concerns the nature and

spatial characteristics of its links with the above four interaction nets. This

is prior to any consideration of core/periphery relation because one region

must be linked to another by systemic interaction in order for a consideration

of whether or not interpolity relations involve exploitation or domination is

relevant. The spatial characteristics of these networks clearly depend on the

costs of transportation and communications, and whether or not interaction is

only with neighbors or there are regularized long-distance trade journeys being

made. But these factors affect all kinds of interaction and so the relative

size of networks is expected to approximate what is shown in Figure 1. Fall-off

in the PMN generally occurs

after two or three indirect links. Suppose polity X is fighting and allying

with its immediate neighbors and sometimes with the immediate neighbors of its

neighbors. So its direct links extend to the neighbors of the neighbors. But how

many indirect links will involve actions that will importantly affect this

original polity? The number of indirect links that bound a PMN is usually either two or three. As

polities get larger and interactions occur over greater distances, each

indirect link extends much farther across space. But the point of important

fall-off will usually be after either two or three indirect links.

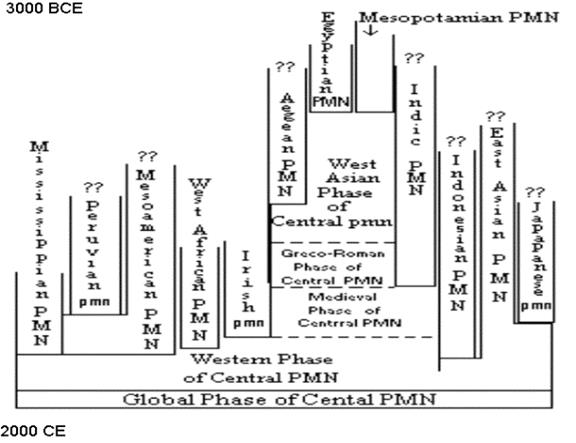

Figure

2: Chronograph of the Emergence of the

Using this conceptual apparatus, we

can construct spatio-temporal chronographs for how the social structures and

interaction networks of human populations changed their spatial scales to

eventuate in the single global political economy of today. Figure 2 uses PMNs as the unit of analysis to show

how what David Wilkinson (1987) calls “Central Civilization,” a PMN that was formed when the Mesopotamian

and Egyptian PMNs merged in about

1500 BCE and which eventually incorporated all the other PMNs into itself to become the

contemporary global interstate system. The timing of mergers and expansions

depicted in Figure 2 are based on Wilkinson’s careful reading of world history

to determine when the regions specified began to make war and alliances with

one another. This kind of chronograph could be constructed for other regions

using the same kinds of historical evidence, and this would be a huge

contribution to our knowledge of the expansion of socio-cultural systems.

World-System Cycles: Rise-and-Fall

and Oscillations

Comparative

research reveals that all world-systems exhibit cyclical processes of change.

There are two major cyclical phenomena: the rise and fall of large polities,

and oscillations in the spatial extent and intensity of trade networks. “Rise

and fall” corresponds to changes in the centralization of political/military

power in a set of polities. It is a question of the relative size and

distribution of power across a set of interacting polities.

All world-systems in which there are

hierarchical polities experience a cycle in which relatively larger polities

grow in power and size and then decline. This applies to interchiefdom systems

as well as interstate systems, to systems composed of empires, and to the

modern rise and fall of hegemonic core powers (e.g.,

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) contend

that the causal processes of rise and fall differ to some extent depending on

the predominant mode of accumulation. One big difference between the rise and

fall of empires and the rise and fall of modern hegemons is in the degree of

centralization achieved within the core. Tributary systems alternate back and

forth between a structure of multiple and competing core states on the one

hand, and core-wide (or nearly core-wide) empires on the other.[8]

The modern interstate system experiences the rise and fall of hegemons, but

these never take over the other core states to form a core-wide empire. This is

because the modern hegemons have pursued a capitalist, rather than a tributary,

form of accumulation.

Analogously, rise and fall works

somewhat differently in interchiefdom systems because the institutions that

facilitate the extraction of resources from distant groups are not as developed

in chiefdom systems. David G. Anderson’s (1994) study of the rise and fall of

Mississippian chiefdoms in the Savannah River valley provides an excellent and

comprehensive review of the anthropological literature about what

Chiefs relied more on hierarchical

kinship relations, control of ritual hierarchies, and control of prestige goods

imports than did the rulers of true states. These chiefly techniques of power

are all highly dependent on normative integration and ideological consensus.

States developed specialized organizations for extracting resources that

chiefdoms lacked—standing armies and bureaucracies. And states and empires in

the tributary world-systems were more dependent on the projection of armed

force over great distances than modern hegemonic core states have been. The

development of commodity production and mechanisms of financial control, as

well as further development of bureaucratic techniques of power, have allowed

modern hegemons to extract resources from far-away places with much less

overhead cost.

The development of techniques of

power has made core/periphery relations ever more important for competition

among core powers and has altered the way in which the rise-and-fall process

works in other respects. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997, Chapter. 6) argue that

population growth, degradation of natural resources, and changes in productive

technology and social structure, have generated sociocultural development that

is marked by cycles and occasional upsweeps. This is because any world-system

varies around an equilibrium as a result of both internal instabilities and

environmental fluctuations. Occasionally, on one of the upswings, a system

solves its problems in a new way that allows for substantial expansion. The

point is to explain expansions, qualitative transformations of systemic logics,

and collapses by studying whole world-systems over time and by comparing these

to one another.

The multiscalar regional method of

bounding world-systems as nested interaction networks outlined above is

complimentary with a multiscalar temporal analysis of the kind suggested by

Fernand Braudel’s work. Temporal depth, the longue durée, needs to be

combined with analyses of short-run and middle-run processes to fully

understand social change.

A strong case for the very longue

durée is made by Jared Diamond’s (1997) study of the long-term consequences

of original differences in zoological and botanical wealth or “natural

capital.” The geographical distribution of those species that could be easily

and usefully domesticated (combined with the relative ease of latitudinal vs.

longitudinal diffusion) explains a huge portion of the variation in which

world-systems expanded and incorporated other world-systems.

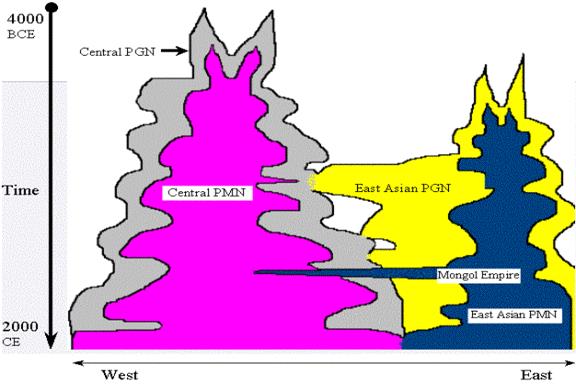

The diagram in Figure 3 depicts the

coming together of the East Asian and the West Asian/Mediterranean systems.

Both the PGNs and the PMNs are shown, as are the oscillations

and rise and fall sequences. The larger PGNs

linked intermittently and then joined. The PMNs

were joined briefly by the Mongol conquerors, and then more permanently when

the Europeans and Americans established Asian treaty ports. The pink area of

Figure 3 depicts the same

It should be noted that the

depiction in Figure 3 of the spatial boundaries of the PMNs and the PGNs is

only an approximation. Another rough depiction of expanding, contracting and

eventually merging is contained in Chase-Dunn and Hall’s (1998) study of

world-systems in

Figure

3: The Eastern and Western PMNs and PGNs

The following section describes the proposed structure and

format for a geo-chronological dataset that focuses on the religious, trade,

conquest, demographic, political, climate change and epidemiological aspects of

settlements and polities in four world regional PMNs and the Central PMN over

the past six millennia. The main purpose

of this dataset is to enable the determination of the

main causes of systemic integration and disintegration.

The Polities

and Settlements in World Interaction Networks (PSWIN) dataset will be

established and maintained by the Settlements and Polities Research Working

Group at the Institute for Research on World-Systems (IROWS) at the University

of California-Riverside in collaboration with colleagues at other universities.

This data set will be made available for public usage. The dataset will link with the World

Historical Dataverse at the University of

The proposed data set will use CSV data files that

will be stored on the IROWS web site at the

The PSWIN data set will include historical

quantitative estimates of several demographic, political, climate and

epidemiological characteristics of settlements and polities. The

characteristics will be grouped into several world regional PMNs. Additional world regions can be added if

quantitative estimates of the main variables are located. An effort will be made to use the same or

similar metrics across world regions, but in some cases this may not be

possible.

World

Regional PMNs and the Central Political-Military Network

Four

world regional PMNs and the expanding Central PMN will be initially studied:

Each of the

world regional PMNs mentioned is understood in world-systemic terms as

including populations that were importantly interacting. So, for example,

Mesopotamia includes the Susiana Plain in

The SetPol Project

The SetPol project is constructing a multidisciplinary theoretical

research program to test hypotheses about the causes of changes in city and

empire sizes from the second millennium BCE to the present in order to shed

light on the contemporary and near future global situation. The project is inventorying explanations of

scale changes from anthropology, sociology and political science and is developing

and populating templates for a graph database that will allow the use of geographical and network analyses for studying

interactions among cities and empires. This database structure makes it

possible to test causal propositions and models derived from the comparative

evolutionary world-systems perspective, geopolitics and human ecology --

theoretical perspectives that have been developed by sociologists,

anthropologists and political scientists—and constructs a multidisciplinary

sociohistorical theoretical research program. The quantitative graph database

includes the territorial sizes of states and empires (polities), the population

sizes of cities and polities, interaction links and climate change in ten world

regions over the past 3500 years. The project also spatially bounds whole

interaction networks by estimating changes in the boundaries and intensities of

human interactions of several kinds: everyday necessities, the trade of high

value goods, the interactions of fighting and allying polities and the

diffusion of ideas and genetic materials. SetPol codes the power configurations

(unipolar, bipolar, multipolar, etc.) of interstate systems and the

world-system positions of settlements and polities (core, semiperiphery and

periphery) within regional interaction networks. Causal propositions will be

tested using five different units of analysis: individual cities and polities,

networks of interacting cities and polities and spatially constant regions and

the whole Earth as a single context for studying the causes of changes in urban

and polity scales. A research team from archaeology, anthropology, geography,

history, political science, sociology, ecology and climatology will carry out

this first two-year phase. The multidisciplinary theoretical research program

that will be developed will come primarily from anthropology, sociology,

political science and geography, but participation by climatologists,

historians, computer scientists and ecologists will contribute to the

production of an improved database that allows for the use of geographical and

network research methods.

The

long-standing upward trends in the sizes of cities and polities is well known,

but still in dispute are the long-term, proximate and contextual causes of

these trends. The SetPol project improves upon and extends existing

quantitative compilations of estimates of the sizes of cities and polities to

identify those instances in ten world regions in which upsweeps in polity and

city sizes have occurred, and will empirically examine the human and natural

factors that have been hypothesized to be the causes of these instances of

scale change. The project also identifies instances of collapse in the sizes of

polities and cities and studies their causes. The project also develops

accurate approximations of the growth and intensity of interaction networks

that have constituted economic and political globalization since the late

Bronze Age. The project employs both standard comparative methods and recently

developed geographical and network approaches to data analysis that use both

GIS spatial analysis and formal network methods. This contributes to the

scientific understanding of the causes of the emergence of complexity and

hierarchy in human societies and deepens our understanding of sociocultural

evolutionary processes.

The SetPol project uses both quantitative estimates

of population sizes of the largest cities in world regions and estimates of the

territorial sizes of largest states and empires to study the causes of changes

in the scale of human institutions. Upsweeps are instances in which the largest

settlement or polity in a region significantly increases in size for the first

time. The project also uses spatially constant world regions as well as

spatially changing whole interaction networks (world-systems) as units of

analysis. This multidisciplinary research is organized around the territorial

sizes of polities and the population sizes of cities because these are

relatively easily ascertainable quantitative indicators of system size and

complexity. Interval scale metrics are needed in order to tell the difference

between small and large changes in scale.

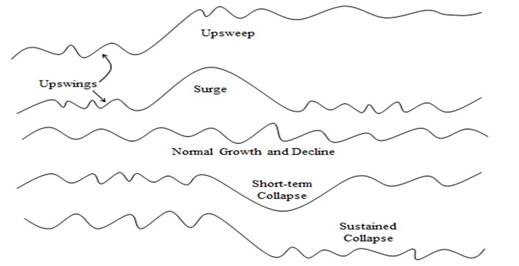

When human sociocultural systems are studied over long periods of time

cyclical processes of population growth and decline, the rise and fall of large

and strong polities, are empirically evident. This project will employ a

systematic method[10] of

differentiating between a “normal” upswing or downswing in which the scale of

sociocultural organization is fluctuating around an equilibrium level and an

event of growth or decline that is significantly greater than the normal

fluctuations (see Figure 1). Focusing on

the largest cities and polities in each region rather than on individual cities

or polities makes these cycles of upswings, downswings, upsweeps and collapses visible. Are the forces and conditions that cause

upsweeps simply larger than those that cause upswings, or are different factors

involved? Or do they combine in different ways? And are the causes of upsweeps

the same as the causes of collapses but in reverse? The project uses upswings,

upsweeps, downswings, downsweeps and collapses of city and polity sizes as

dependent variables to be explained. This project studies city and polity sizes

in ten world regions from 1500 BCE until 2010 CE.

Figure 1. Types of

Medium-term Scale Change in the Largest Cities and Polities

SetPol builds on and improves earlier data compendia and uses the

upgraded data to more accurately identify upsweep and collapse events (Inoue et

al 2012 and Inoue et al 2015).

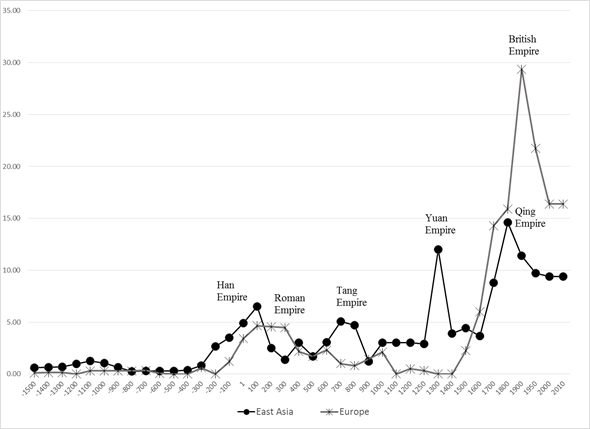

An example of results obtained using the territorial sizes of the

largest polities in Europe and East Asia is shown in Figure 2.

Figure

2: Sizes of largest polities in Europe and East Asia (square megameters): 1500 BCE- 2010CE

Figure 2 shows the

sizes of the largest states and empires in Europe and East Asia since 1500 BCE.

Both regions show the overall long-term trend toward greater polity sizes and

also the sequences of shorter-term fluctuations. When we look at Europe’s

trajectory vis a vis East Asia in Figure 2 we can see that the rise of

the Han Empire in China began earlier than the rise of the large Macedonian and

Roman empires in Europe and the decline began earlier in East Asia than it did

in Europe. China did it first, followed not long after by Europe. The European

peak then last rather longer than did the Chinese peak. This was what many have

observed as the unusually long tenure of the Roman Empire. Then Europe went

into a long slump while Tang China recovered. So these waves of empire

formation were partly, but not entirely, synchronous, and Walter Scheidel’s

(2009) idea of the first great divergence[11] is

supported. But the apparent divergence was partly due to the earlier start of

East Asia. The later rise of Europe began in the 15th century,

contrary to Andre Gunder Frank’s (1998,2014) contention that the great

divergence that was the rise of Europe was a late and conjunctural event. Qing

China also got very large but ended up only half as large, in terms of

territorial size, as the British Empire.

The main

multidisciplinary theoretical thrust of SetPol is based on a scope of

comparison that comes from anthropology, archaeology and world history. This

scope is combined with competing explanations of scale changes that come from

ecology, sociology, history and political science, especially international

relations theory.[12] Sociology gave birth to the world-system

perspective (Wallerstein 1974), which posits the existence of a hierarchical

Europe-centered interstate system that emerged in the long sixteenth century CE[13] in

which some polities (those in the core) exploit and dominate others (the

semiperiphery and the periphery). SETPOL

will utilize an anthropological and world historical framework to compare

small, regional and global world-systems over the past 3500 years (Chase-Dunn

and Hall 1997; Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014). .

Political scientists focus on political

institutions and on international relations, especially regarding power

dynamics among competing states, institutions of diplomacy and arms races.

International relations theory focuses on geopolitics as a struggle for power

in which military capabilities and warfare are central components. Geopolitics

is most often understood as a multiplayer game in which territorial strategies

are an important element, in means and ends, of power struggles. Most

international relations theorists focus on the interstate system that emerged

in Europe after being institutionally defined by the treaty of Westphalia in

1648 CE. SETPOL uses an anthropological and world historical framework to

examine the nature of interstate systems since the emergence of early states in

Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Chase-Dunn and Hall

(1997) contended that world-systems, defined as interaction networks with

consequential effects for local social structures, are the most important unit

of analysis for explaining large-scale social change. The evolutionary[14]

world-systems perspective allows comparisons between whole interaction networks

that are different in size, period and location. They point out that different kinds of

interaction have distinct spatial characteristics and degrees of importance in

different kinds of world-systems. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) employ a

place-centric approach that bounds spatial networks by asking what reproduces

or changes the social structures of a designated locality. Always important are

low value per unit of weight food and other everyday raw materials (bulk goods)

that form a network that is usually spatially smaller than the network of

political/military interaction. And there are even larger networks formed by

exchanges of information and prestige goods that may be consequential for local

social structures. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) also turn the issue of

core/periphery hierarchies into an empirical question rather than a

definitional assumption. The evolutionary comparative world-systems approach

allows for the possibility that world-systems might exist that do not have

core/periphery hierarchies, and indeed the small-scale system in indigenous

Northern California studied by Chase-Dunn and Mann (1998) had very limited

interpolity domination and exploitation. Core/periphery hierarchies emerge and

evolve, along with other types of inequality, as the capabilities of some

polities to extract resources from distant peoples develop.

Most state-based

world-systems are organized as hierarchical interstate systems in which core

polities and cities exploit and dominate non-core peoples. Power is organized

in different ways in different systems and so what semiperipherality is in any

system depends on what coreness and peripherality are. These are relational

concepts. But it is possible to identify these world-system positions in very

different kinds of systems based on common characteristics that are associated

with them such as population density, geographical location, and differences in

modes of accumulation (foraging, pastoralism, horticulture, agriculture, scale

of irrigation, industrialization). Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) describe a

phenomenon they call “semiperipheral development.” This involves the observation that peoples

and polities that are semiperipheral vis a vis the larger world-system

of which they are a part are more likely to implement technological and

organizational forms that facilitate upward mobility and/or that change the

developmental logic of world-systems.

One variety of this phenomenon involves semiperipheral marcher

states that conquer older core regions to produce an upsweep in polity size.

Another variety involves semiperipheral capitalist city-states that are agents

of commodification—the expansion and deepening of trade networks. Increasing

trade and production for exchange facilitates provides a fertile context for

the emergence of larger cities and larger polities.

There are several possible processes that might

account for the phenomenon of semiperipheral development.

Randall Collins (1999) has argued that the phenomenon of marcher states

conquering other states to make larger empires is due to the “marcher state

advantage.” Being out on the edge of a core region of competing states allows

more maneuverability because it is not necessary to defend the rear. This

geopolitical advantage allows military resources to be concentrated on

vulnerable neighbors. Peter Turchin (2003) has argued that the relevant process

is one in which group solidarity is enhanced by being on a “metaethnic

frontier” in which the clash of contending cultures produces strong cohesion

and cooperation within a frontier polity, allowing it to perform great feats.

Carroll Quigley (1961) distilled a somewhat similar theory from the works of

Arnold Toynbee. Another factor affecting within-group solidarity is the

different degrees of internal stratification usually found in premodern systems

between the core and the semiperiphery. Core societies develop old, crusty and

bloated elites who rely on mercenaries and “foreigners” as subalterns, while

semiperipheral leaders are often charismatic individuals who identify with

their soldiers and citizens (and vice versa). Less inequality within a polity

often means greater group solidarity and this may be an important part of the

semiperipheral advantage. Ibn Khaldun’s (1958) model of nomadic barbarians

conquering decrepit old civilizations has been an inspiration to some of this

thinking. And the tie with internal inequality may also be linked with waves of

population growth and unrest within polities – the so-called “secular cycle”

(Goldstone 1991; Turchin and Nefadov 2009).

Hub theories of innovation have been popular among

world historians (e.g. McNeill and McNeill 2003; Christian 2004) and human

ecologists (Hawley 1950). These hold that new ideas and institutions emerge in

central settlements where information crossroads are located. Mixing and recombination

of ideas and information leads to the emergence of new formulations. Recent studies have shown evidence that

information exchange, innovations, and political, economic and social

activities increase exponentially with city size (Ortman et al. 2014; Ortman

et al. 2015).

Esther Boserup (1965) developed a

demographic theory that focuses on population growth and population pressure as

the master variables behind social change. Technological change was explained

as an adaptation to population density nearing or exceeding the carrying

capacity of the environment under a given technological regime. Cultural

ecology and population pressure have important implications for sociocultural

development when they are combined with the idea of social and ecological

circumscription proposed by Robert Carneiro (1978). Carneiro explained

the social organizational ruptures that produced the first states in terms of

population pressure in a geographic situation in which outmigration was

impossible or very costly. Under these conditions people stay and fight rather

than migrating. High levels of warfare killed off population and reduced

population pressures. Some systems got caught in a vicious cycle in which

warfare operated as a demographic regulator (e.g. Kirch 1991). But in other

systems people became tired of warfare and allowed the emergence of elites who

organized larger polities that regulated conflict and resource allocation

(property). The elements of population pressure, intensification of production,

ecological degradation, technological change, conflict, and circumscription are

combined in different ways by different theorists, but these are the main

ingredients that comprise most of the explanations of long run cultural

evolution by archaeologists and many anthropologists (e.g., Johnson and Earle

1987; see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 6).

SetPol’s main dependent variables are changes in

the scale of polities and cities. Individual polities and cities will be

studied, and the sizes of the largest of these within regions and interaction

networks will be studied as characteristics of the region or the network.[15]

As mentioned above this project will divide the indicators of scale change into

upswings, upsweeps, downswings, downsweeps, surges and collapses (Inoue et

al 2012). Though these are all based on the sizes of largest cities and

polities, timing and the way in which the unit of analysis is employed (regions

vs different kinds of networks) will affect the identification of these scale

changes. The main independent variables that will be studied are: the

world-system positions of polities and cities (core-semiperiphery-periphery),

the power configurations of interstate systems (unipolar, bipolar, multipolar,

etc.) (Wilkinson 2003), changes in the intensity of warfare, network node

centrality, the centralization of whole networks (graph centrality); climate

change, and environmental degradation. The project will also examine the extent

to which changes in the sizes of cities are associated with changes in the

sizes polities. In addition to focusing on the largest cities or polities in

each region or network, the project will also compute and study the size

distributions of largest cities and polities. Urban geographers have long

theorized about the causes and consequences of city size distributions.[16]

Our comparison of largest polities in East Asia, Europe and the Central

Political/Military Network[17] enable us to ascertain how the size

distributions have changed over time and how these may be related with scale

changes and possible inter-regional synchronies.

The SetPol theoretical

research program is developing and testing an integrated synthetic model of the

long-term causes of human sociocultural evolution – specifically the growth of

cities and polities, but also increasing structural complexity and hierarchy in

human polities and world-systems. The integrated model combines the iteration

model produced by Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997: Chapter 6; Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2014: Figure 2.5 on page 27) with the structural demographic model developed by

Jack Goldstone (1991) and elaborated and formalized by Peter Turchin and Sergey

Nefadov (2009). This multilevel model includes processes that operate within

settlements and polities, especially demographic growth, population pressure,

growing inequalities, social movements and state failure, with processes that

operate between polities (warfare, interpolity trade, semiperipheral

development, etc.) and climate change and epidemic diseases.

The Comparative Framework

SetPol

studies expanding and contracting interaction networks among human polities and

settlements as both units of analysis and as causal contexts of scale changes

in the sizes of cities and empires. Human interaction networks have expanded

and intensified over the long run (globalization), but in the medium-run there

have been cycles of network expansion and contraction.

The best way to spatially bound human social

systems is an old question that continues to generate heated disputes among

social scientists. Michael Mann (1986) notes that different important kinds of

interaction have different spatial scales, and so the notion that societies

have single spatial boundaries is usually incorrect and causes much

misunderstanding. Many regionalists define regions in terms of homogenous

attributes, either natural or social.

Comparative civilizationists have tended to focus on the core cultural

characteristics that are embodied in religions or world-views and have

constructed lists of such culturally defined civilizations that then become the

“cases” for the study of social change (e.g. Melko and Leighton 1987). Another

approach that defines regions as areas with homogenous characteristics is the

“culture area” approach developed by Alfred L. Kroeber and his colleagues (e.g.

Wissler 1927; Kroeber 1944). This project gathered valuable information on all

sorts of cultural attributes such as languages, architectural styles,

technologies of production, and kinship structures, and used these to designate

bounded and adjacent “culture areas” that have been widely used to organize

studies of indigenous peoples (e.g. Sturtevant 1978-2007, the Smithsonian

Handbook of North American Indians).

A major problem with both the civilizationist and

the cultural area traditions is the assumption that homogeneity is a good

approach to bounding whole social systems. Heterogeneity rather than

homogeneity has long been an important aspect of human social systems because

different kinds of groups often complement one another and interaction often

produces co-evolution and differentiation.[18] The

effort to bound systems as homogeneous regions obscures this important fact.

Spatial distributions of homogeneous characteristics do not bound separate

social systems. Indeed, social heterogeneity is often produced by interaction,

as in the cases of core/periphery differentiation, urban/rural, and

sedentary/nomadic systems. Even sophisticated approaches that examine

distributions of spatial characteristics statistically must make quite

arbitrary choices in order to specify regional boundaries (Burton, Moore,

Whiting and Romney 1996).

David Wilkinson (2003) has made a strong case for

studying civilizations as networks of allying and fighting polities and he has

produced a chronograph of the expansion of the interstate system that emerged

when the Mesopotamian and Egyptian systems became linked around 1500 BCE

(Wilkinson 1987). Many world-systems scholars have contended that trade

networks are the best unit of analysis for spatially bounding whole systems

(Abu-Lughod 1989; Beaujard 2005, 2010). Immanuel Wallerstein (1995; 2011

[1974]) contends that a hierarchical core/periphery division of labor,

especially the one that emerged with Europe as its core in the long 16th

century CE, is the best way to spatially bound a world-system. And several

eminent scholars have claimed that there has been a single global (Earth-wide)

system for millennia (Lenski 2005; Frank and Gills 1994; Modelski 2003;

Modelski, Devezas and Thompson 2008, and Chew 2001, 2007). The SetPol project

operationalizes all these units of analysis and pits them against one another

regarding their relevance for explaining scale changes of polities and cities.

We also have convened a workshop to more completely and accurately specify the

changes in trade and PMN network boundaries since 1500 BCE (Chase-Dunn et al

2015a). And we also use constant regions to make comparisons so that it is

possible to compare the results with what we find when we use spatially-bounded

networks.

.

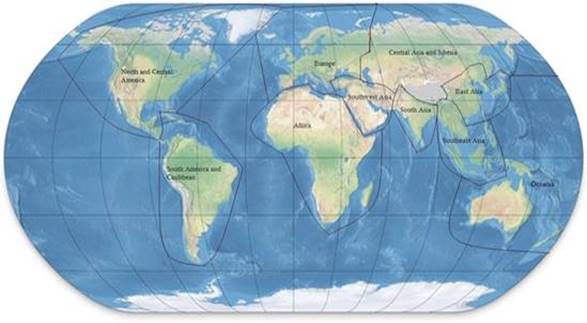

Figure 3: Ten world regions for studying the

emergence of large cities and polities

These boundaries have been chosen in order to

facilitate the comparative study of the emergence of largest cities and polities

over the past 3500 years. The regional

boundaries shown are mainly matters of convenience. All cities and polities are

geocoded so that different regional configurations can easily be used by other

researchers. These regions have been chosen in order to construct a data

compendium that will include information on all the areas of the Earth where

humans have lived in large numbers. The regions specified in Figure 3 are

mainly based on our knowledge of where large cities and empires emerged in the

period we are studying. But we have also considered the social science

literature that has hypothesized comparisons and connections among regions in

our designation of regions. We are well aware of the issue of Eurocentrism in

social science and the obvious point that “Europe” is not a continent, but is

rather a promontory of Eurasia (Lewis and Wigen 1997). Social science itself

has been constructed around comparisons between East and West and so an

important way to scientifically address the issues of comparison and

connections is to use some of the categories that have been constructed in the

past to see whether alleged differences (or similarities) are supported or

contradicted by quantitative data.

Admittedly some of the

bounding decisions we have made are somewhat arbitrary. We included the

Caribbean with South America rather than with North and Central America because

migrants from South America mainly peopled it. We made a great effort to have

only ten world regions rather than some larger number of regions in order to

keep our data gathering structure from becoming too complicated. But it should

be recalled that all of the settlements and polities we study are geocoded, so

if other researchers want to reconfigure regions in a different way they easily

can.

Using world regions designated in this way allows

us to address the important issues raised by world historians and

civilizationists who compare regions (e.g. Pomeranz 2000; Scheidel 2009, Wong

1997; Morris 2010, Frank 1998). The SetPol project is also be able to compare

the use of these spatially constant regions with what we find when we use

expanding networks (e.g. Chase-Dunn et al 2015b). The proposed

operationalization of network boundaries is based on a propositional inventory

of statements by social scientists about when smaller networks expanded, merged

and when larger networks engulfed smaller ones (e.g. Beaujard 2005; 2010;

Wilkinson 1992a; 1992b, 1993). The project uses data on trade networks,

historical accounts of warfare and diplomacy and studies of the diffusion of

plants, animals, and technologies and ideas to evaluate the claims made by

scholars about interaction networks and the timing of their expansions.

Chronological

Issues

For purposes of comparing the timing of changes in

city and polity sizes across different world regions it is important to have

accurate absolute chronologies for the regions being compared in order to

examine issues of priority and synchrony. Unfortunately there is still

considerable disagreement about the absolute dating for Mesopotamia before 1500

BCE. Mario Liverani (2014: 9-16) explains why estimates of absolute dates are

so uncertain. Relative dates of events needed for estimating polity and city

sizes are based on “king lists.” Thus an event, such as a conquest, is said to

have occurred in the third year of the reign of King X. Considerable effort has

been made to figure out the correspondences between different kings’ lists in

Mesopotamia and their correspondence with Egyptian king lists, which are more

continuous. These are then converted in to calendar years by ascertaining their

relationships with astronomical events such as eclipses. Unfortunately there is

a period after the fall of the Babylonian empire in which king lists are

missing for Mesopotamia, and there is disagreement about the timing of

astronomical events. Thus the length in years of the occluded period is in

dispute, and this results in so-called, short, medium and long chronologies for

the period before the Late Bronze Age, with an error of as much as 100 years.

Absolute dating is needed in order to compare the timing of scale changes

across world regions. It matters whether or not the city of Ur was sacked

in 2004 BCE, and thus is eliminated from the list of large cities and large

polities in 2000 BCE, or in some other year 50 years earlier or later. Liverani

(2014: 15) is satisfied to use the middle chronology for Mesopotamia and the

surrounding regions, but he is not trying to compare the timing of changes in

the Ancient Near East with other world regions. The SetPol project uses the

middle chronology, while being careful to determine which chronology has been

used in the sources from which estimates are coded. It is important to be chary

regarding temporal comparisons among regions before 1500 BCE.

The

SetPol goal is to achieve a minimum temporal resolution of every twenty-five

years because the project is studying middle-run growth/decline phases of

polities and cities. Archaeological evidence of the areal sizes of settlements

and hearth counts can be used to estimate settlement sizes, but the limitation

here is often temporal resolution. Studies that rely on radiocarbon dating and

archaeological phase periodization often do not achieve a level of temporal

resolution that would make settlement growth/decline phases visible (e.g.

Ortman, Cabaniss, Sturm and Bettancourt 2014). When temporal resolution is

poorer than every 100 years it is likely that some of the cycles of growth and

decline will be missed. In the first

phase of our project we will focus on regions for which both documentary and

archaeological evidence are available, and since this phase begins with 1500

BCE we do not need to worry about the issue of absolute dates when comparing

world regions.

Data Upgrading[19]

Improving of estimates of the population sizes of settlements and the

territorial sizes of polities is an endless task, but much has been

accomplished. The long term intent of the SETPOL project is to include all the

towns and cities with 10,0000 or more people and all the polities with .01 or

larger square megameters of territory in the ten world regions from 4000 BCE to

2010 CE. But in the exploratory phase of the project (the first two years) the

project will prioritize by focusing on upgrading existing data sets that

include the ten largest cities and polities in each of the world regions

at 25-year intervals since 1500 BCE.

Improving estimates of the territorial sizes of polities

Determining

scale shifts requires real metric (interval-level) estimates, not just

periodizations of growth and decline. The territorial sizes of polities are

difficult to estimate from archaeological evidence alone (see Smith and Montiel 2001). What the SETPOL project wants to know is the size of the area

over which a central power exercises a degree of control that allows for the

appropriation of important resources (taxes and tribute). The ability to

extract resources falls off with distance from the center in all polities, and

controlling larger and larger territories requires the invention of new

transportation, communications and organizational technologies [what Michael

Mann (1986) has called “techniques of power”]. Military technologies and bureaucracies

are important institutional inventions that make possible the extraction of

resources over great distances, but so are new ideologies and new technologies

of communication (Innis 1950).[20]

Estimating

the territorial sizes of states and empires has been based on the use of

published historical atlases and historical accounts. Premodern states and

empires often had fuzzy boundaries. Bounding polities is based primarily on

knowledge about who conquered which city, and whether or not, and for how long,

tribute was paid to the conquering polity. Sometimes it is difficult to tell

whether or not tribute is asymmetrical or symmetrical exchange. Only

asymmetrical (unequal) exchange signifies a tributary imperial relationship.

Otherwise it is just trade and does not signify an extractive relationship.

The pioneer coder of the territorial sizes of

polities is Rein Taagepera (1978a, 1978b, 1979, and 1997). The SETPOL project

builds upon Taagepera’s monumental work and uses his methods. Taagepera used

Atlases and historical descriptions of events to estimate the territorial sizes

of states and empires. This project will improve upon his estimates by using

Atlases that had not been published when Taagepera did his work (e.g.

Schwartzberg (1992). The project will also use

online sources such as the University of Sydney Timemap Project. The values

produced from these tertiary sources will be checked with regional experts (see

Data Management section).The SETPOL polity data template utilizes Taagepera’s

method of coding the year in which polity sizes change, usually as a result of

conquests, and will designate area in square megameters as Taagepera did.[21] It will

also include a standardized identification code for each separate polity,

fields for alternative names of the polity, geocodes for the location of the

capital city and estimates of the population size of the polity.[22]

Improving estimates of the population sizes of

cities and territorial sizes of states and empires

SETPOL is developing a template for coding characteristics

of individual cities that include estimates of the size of the built up area as

well as estimates of the population size. The city template also includes

unique identifiers for each city, fields for alternative names of the city and

the geocode of the city center. For the

location identification, the geo URI scheme is applied.[23] The data are structured in the three

dimensions—each city has sets of variables, and each of these variables has

varying value ranges and time intervals. The variables and their definitions

are being developed in collaboration with the SESHAT project team in order to

avoid redundancies in collecting data. A template for polities for coding

similar variables is also being constructed.

Making accurate

estimations of the population sizes of both contemporary and early urbanized

areas involves several complicated problems. Daniel Pasciuti (Pasciuti 2003;

Pasciuti and Chase-Dunn 2003) has proposed a measurement error model for

estimating the sizes of settlements based on the literature in archaeology,

demography and urban geography.[24] The SETPOL

project defines a settlement as a spatially contiguous built-up area.[25] This is

the best operationalization for comparing the sizes of settlements across

different polities and cultures because it ignores the complicated issues of

governance boundaries (e.g. municipal districts, etc). But it still has some

problems. Most cultures have nucleated settlements in which residential areas

surround a monumental, governmental or commercial center. In such cases it is

fairly easy to spatially bound a contiguous built up area based on the

declining spatial density of human constructions. But other cultures space

residences out rather than concentrating them near a central place (e.g. many

of the settlements in the prehistoric American Southwest such as Chaco Canyon). In such cases it is necessary to choose a

standard radius from the center in order to make comparisons of population

sizes over time or across cultures.

Existing compilations of city sizes rely primarily

on:

1.

Tertius Chandler 1987 Four Thousand Years of

Urban Growth: The Edwin Mellen Press

2.

George Modelski 2003 World Cities: –3000 to 2000.

Washington, DC: Faros 2000

3.

Ian Morris

2013 The Measure of Civilization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Tertius

Chandler’s (1987) compendium is still the most comprehensive study of large

cities, but substantial improvements were made in George Modelski’s (2003)

compendium. Ian Morris also provides estimates of the largest cities in his

book on measuring the development of Eastern and Western civilizations (Morris

2013). The SETPOL project will improve upon existing city size compilations by

collaborating with other projects and incorporating data sets produced by

others.[26]

The proposed city template includes both the calendar year in which the size of

a city is known to have rapidly changed (e.g. the example of the sack of Ur

mentioned above) as well as interpolated estimates for the standardized years

used by Chandler and Modelski.[27]

This project

will contribute to the scientific understanding of the emergence of complexity

and hierarchy in human societies. The long-term upsweep of the scale of cities

and polities is widely known, but heated debates still rage regarding the

proximate and contextual causes of these trends. While certain human and

natural factors have been famously hypothesized to be the causes of instances

of these scale changes, empirical testing of hypothetical causes has been

daunted by the limited comprehensiveness, accuracy, and verifiability of extant

data sets on the scale changes. So SETPOL will improve the testability of

causal hypotheses by generating a data set that is better in these regards. SETPOL

will also contribute to the accurate delineation of the spatial boundaries of

trade and political/military interaction networks as they merged and engulfed

one another to constitute the contemporary global system of today.[28] The project will use not only

well-established methods for organizing and analyzing data, but also a graph

data structure that will allow the combination of GIS with formal network

analysis. The project will increase the legibility of the complex spatial

processes that led to the emergence of the increasingly global society of

today.

Multidisciplinary Character of the Project

The SETPOL database will use standardized

geographical network protocols in order to make the data freely available for

use by scholars from different disciplines. The framework of comparison is

anthropological and world historical. The hypotheses to be tested come from

causal models proposed by political scientists, anthropologists and

sociologists, especially those who are informed by multidisciplinary

perspectives such as geopolitics, human ecology, and the comparative evolutionary

world-systems approach. The SETPOL project emphasizes cooperative

multidisciplinary exploration of the pathways by which scale changes have

occurred in cities and polities. The project

will coordinate and collaborate with other multidisciplinary consortia that are

currently compiling relevant data. The project will further develop a

multidisciplinary theoretical research program by engaging scholars from

different disciplines at the levels of empirical measurement and the

development and testing of causal models. The SETPOL project produces articles,

monographs and infograms that are intended for a broad multidisciplinary

audience.

Broader Impacts

The project's intellectual impact lies in the

development of a more holistic multidisciplinary approach to understanding the

connections between climate change, demographic expansion and contraction and

the size and complexity of human social organization. By

confirming or disconfirming the accuracy of contending scientific models of the

development of complexity and hierarchy in human societies, the project will

help scholars, educators and policy-makers to grasp the main patterns of

historical sociocultural evolution. Such

understanding matters for societal responses to major challenges of the 21st

century: climate change, ecological degradation, population density, the

emergence of global city regions, the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers,

and transitions from a unipolar to a multipolar geopolitical structure. The

project will also allow provide fresh evidence on the comparisons of

similarities and differences across world regions with important implications

for explanations of uneven East/West development – issues that have been

totemic and fundamental in the development of social sciences since the

eighteenth century. The project will have important implications regarding the

understanding of past systemic resilience and collapse, and these will have

significant implications for the future. The SETPOL project will develop

undergraduate and graduate-level courses and research projects to train

students to do multidisciplinary research and particularly to develop

infographic presentations for teaching scholars and the general public.

REFERENCES

Abu-Lughod,

Janet. 1989. Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Adams, Robert

McCormick. 1981. The Heartland

of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain

of the Euphrates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Alexandria

Digital Library (ADL) Gazetteer http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january99/hill/01hill.html

Algaze,

Guillermo. 1993. The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early

Mesopotamian Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Allen,

Mitchell. 1995. Contested Peripheries: Philistia in the Neo-Assyrian

World-System. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, UCLA.

_____.

2005. “Power is in the Details: Administrative Technology

and the Growth of Ancient Near Eastern Cores.” Pp. 75-91 in The Historical Evolution of World-Systems,

edited by Christopher Chase-Dunn and E.

N. Anderson.

Anderson,

Eugene. N. 2014. Food and

Environment in Early and Medieval China. Philadelphia, PA:

University

of Pennsylvania Press.

Anderson, Eugene. N. and C. Chase-Dunn. 2005“The Rise and Fall of Great Powers” in Christopher

Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The Historical

Evolution of World-Systems. London:

Palgrave.

Anderson, David G. 1994 The

Arrighi, Giovanni. 1994. The Long Twentieth Century:

Money, Power and the Origins of Our

Times.

Bairoch, Paul. 1988. Cities and Economic Development Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Barfield, Thomas J. 1989. The

Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and

Blackwell.

Beaujard,

Philippe. 2005 The Indian Ocean in Eurasian and African World-Systems Before

the Sixteenth Century. Journal of

World History 16,4:411-465.

_____. 2009 Les mondes de l’océan Indien Tome

I: De la formation de l’État au premier système-monde Afro-Eurasien (4e

millénaire av. J.-C. – 6e siècle apr. J.-C.). Paris: Armand Colin.

_____. 2010. “From Three possible Iron-Age

World-Systems to a Single Afro Eurasian World-System.” Journal of World

History 21:1(March):1-43.

_____. 2012. Les

mondes de l’océan Indien Tome II:

L’océan Indien, au coeur des globalisations de l’ancien Monde du 7e au

15e siècle. Paris: Armand Colin

Bibby, Geofrey 1969 Looking For Dilmun.

Boles, Elson E.

2012. “Assessing the debate between

Abu-Lughod and Wallerstein over the thirteenth-century origins of the modern

world-syste”・Pp. 21-29 in S.

J. Babones and C. Chase-Dunn (eds.) Routledge Handbook of World-Systems

Analysis. New York: Routledge.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett,

M. G. and Freeman, L. C. 2002 UCINET 6 for Windows: Software for Social

Network Analysis http://www.analytictech.com.

Brohan, P., R.

Allan, E. Freeman, D. Wheeler, C. Wilkinson, and F. Williamson. 2012.

"Constraining the temperature history of the past millennium using early

instrumental observations" Clim. Past, 8, 1551-1563.

www.clim-past.net/8/1551/2012/

Burton, M.L,

C.C. Moore, J.W.M. Whiting, and A.K. Romney. 1996. "Regions based on

Social Structure." Current Anthropology 37:87-123.

Carneiro,

Robert L. 1978 “Political expansion as an expression of the principle of

competitive exclusion,” pp. 205-223 in Ronald Cohen and Elman R. Service (eds.)

Origins of the State: The Anthropology of Political Evolution.

Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

_____. 2004. “The political

unification of the world: whether, when and how – some speculations.” Cross-Cultural

Research 38 (2):162-177.

Chandler,

Tertius. 1987. Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An

Historical Census. Lewiston,N.Y.: Edwin Mellon Press.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher.

1988 "Comparing World Systems: Toward a Theory of Semiperipheral Development." Comparative

Civilizations Review 19(Fall):29-66.

__________ 1990

"Resistance to Imperialism:

Semiperipheral Actors." Review 13:1(Winter):1-31.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and E.N.

Anderson (eds.) 2005. The Historical Evolution of World-Systems.

____________

and

Kelly M. Mann. 1998 The

Wintu and Their Neighbors: A Small World-System in Northern

California, University of

________________

and Thomas D. Hall 2006 “Ecological

degradation and the evolution of world-systems”

Pp. 231-252 in Andrew Jorgenson and Edward Kick (eds.)

Globalization and the

Environment.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Susan

Manning, 2002 "City systems and world-systems: four millennia of city growth and decline," Cross-Cultural Research 36, 4:

379-398 (November).

Chase-Dunn, C., Susan

Manning, and Thomas D. Hall, 2000 "Rise and Fall: East-West Synchronicity and Indic

Exceptionalism Reexamined" Social

Science History 24,4: 721-48(Winter).

____________

Alexis Álvarez, and Daniel Pasciuti 2005 "Power

and Size; urbanization and empire formation in world-systems"

Pp. 92-112 in C. Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The Historical

Evolution of World-Systems.

_____________and T.D.

Hall (eds.) 1991 Core/Periphery Relations

in Precapitalist Worlds.

_______________ and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise

and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

____________________and Thomas D. Hall, 1998

"World-Systems in North America: Networks, Rise and Fall and Pulsations of

Trade in Stateless Systems," American Indian Culture

and

Research Journal 22,1:23-72.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis Alvarez and

Thomas D. Hall 2006 “Waves of globalization and semiperipheral

development in the ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian world-systems. Pp. 114-138 in Globalization