Accelerating Global State Formation and Global Democracy

Christopher Chase-Dunn and Hiroko Inoue

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

![]()

To be presented at the workshop on Present Futures and Future Presents – World State Scenarios for the 21st Century, 24-26 June 2010 in Skagen, Denmark. An earlier version was presented at the the annual meeting of the International Studies Association, New Orleans, Thursday, February 18, 2010.

Draft v. 6/18/10 12224 words. National Science Foundation Grant #: NSF-HSD SES-0527720

This paper is available as IROWS Working Paper #55 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows55/irows55.htm

The emergence of hierarchies and the expansion of the size of polities have been important aspects of human socio-cultural evolution[1] since the beginnings of sedentism in the Stone Age. In the long term, polities have gotten larger and socially structured hierarchies have emerged within and between polities. At the same time there has been a cycle of the rise and fall of large polities. This is well-known as the rise and fall of empires, but chiefdoms and modern hegemons have also risen and fallen.

This essay is mainly about the evolution of global governance in the Europe-centered modern world-system since the 15th century, but the analysis of the trajectory of the modern system is done in the context of the study of human socio-cultural evolution on a millennial scale. We consider the emergence of the European system of sovereign states, the rise and fall of successively larger hegemons, the deepening of global capitalism, waves of economic globalization, the emergence of international regulatory institutions and the prospects for future increased global state formation and global democracy. The patterned sequence of the evolution of increasingly centralized and capacious global governance institutions is examined with an eye to the prospects for speeding up the processes of global state formation and the democratization of the institutions of global governance.

We specify the unique aspects of the current world historical situation in the context of the systemic cycles and trends of the modern world-system and we describe three possible future configurations that might emerge in the next decades. We will also discuss the most important factors that can affect the speed of global political integration and the progressive social movements and national regimes that might propel global integration in the direction of more effective, democratic and legitimate institutions of global governance. We lay out a program and plan for accelerating global state formation and global democracy so that significant democratic political integration might occur within the next three decades.

All world-systems contain multiple polities that importantly interact

with one another, and all hierarchical world-systems exhibit a cycle of rise

and fall in which a powerful polity emerges and then declines. The modern

Europe-centered system also exhibits such a cycle, but it has proven

exceptionally resistant to the formation of core-wide empires. Rather there

have been a series of hegemonic core states that have risen and declined: the

Dutch in the 17th century, the British in the 19th century, and the United States in the 20th century. The evolution of global governance by means of hegemony

displays a pattern in which the hegemon has become larger and larger relative

to the size of the whole system. Also the originally European interstate system

expanded to include the whole globe because of the waves of decolonization of

the colonial empires. And, since the Napoleonic Wars, international political

organizations have emerged and become more important. Thus the long-term trend

has been in the direction of global state formation, though that has not yet

happened. But this trend may take a very long time. The current world

historical situation is one in which the evolution of global governance by

means of hegemony seems to have hit a wall because there are no existing single

states large enough to replace the declining U.S. and yet the forces that might

lead to further global state formation seem relatively weak at present. This

paper examines the factors that could speed up global state formation in the

next few decades by considering the main world historical causes of political

integration in the past and by specifying the particularities of the current

conjuncture.

The Comparative World-Systems Perspective

Our theoretical approach to explaining the long-term pattern of human socio-cultural evolution uses systems of interacting polities as the unit of analysis. This is not a novel approach for International Relations scholars, but many other macrosocial scientists continue to analyze human societies as if they were (or are) closed systems, treating “external” factors as exogenous shocks to systemic processes occurring within each polity. We contend that human polities[2] have always interacted importantly with neighboring polities through trade, warfare and communication and that interpolity and transpolity interactions have been important all along for reproducing and transforming socio-cultural institutions (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997).

In earlier work we have analyzed chiefdom formation, state formation, the rise and fall of empires and the rise of the modern world-system and its sequence of hegemonic rise and fall. We note that all interpolity systems exhibit a cyclical pattern of centralization and decentralization in which a single polity emerges that is large and powerful, and then that polity declines. Among these cycles there are occasional upward sweeps[3] in which a polity that is larger and more powerful than any earlier polity has been in the same system. Our Polities and Settlements Research Working Group at the Institute of Research on World-Systems[4] has quantitatively identified twenty-four such empire upward sweeps in five world regions since the early Bronze Age (Alvarez et al 2010). These are the events that account for the long-term trend in which polities have become larger and more powerful.

Our analysis of the evolution of global governance is informed by research on the growth and decline phases and upsweeps of settlements and polities. We also use a model of the main causes of human hierarchy formation and technological development in world-systems since the Stone Age. Our basic explanation is a positive feedback loop that we call the “iteration model” in which population growth and population pressures lead to migration and eventual circumscription and rising levels of warfare, and that it is in this condition that hierarchies are most likely to emerge within and between human polities, and that these hierarchies often promote technological development, which eventually leads back to population growth as new resources come on line. Thus did humans move to the habitable corners of the Earth and the human population grew to its current size. We also note that some of these processes have been somewhat altered by the emergence of new institutional forms such as markets and states, and that many (or most) of the innovations and implementations of new “techniques of power” emerge from polities that are semiperipheral relative to the polities they are interacting with (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 5; Love et al 2010). This latter process is termed “semiperipheral development.”

Much of recent thinking about long-term social change has been premised on the rejection of functionalism. The evolutionary structural-functionalism of Talcott Parsons (1966; 1971) was vague and implied that the Harvard Faculty Club, like the earlier English redoubts at Oxford and Cambridge, was the highest form of human civilization. The United States, with its relatively autonomous educational, economic, political and religious institutions, was the most institutionally differentiated modern society, and this fit Parsons’ definition of evolution as increasing differentiation and autonomy of institutional domains. A entire generation of critics rejected this as just another instance of the use of evolutionary theory to prop up the claims of superiority by the powerful, as it had done in the 19th century.

But the idea of evolution can be applied without any assumptions about superiority or progress. The scientific study of patterned change and of the emergence of complexity and hierarchy within and between human societies does not require assumptions about progress or regress. It is not necessary to assume that complexity or hierarchies are superior to simplicity or equality in order to study these patterns and their causes.

Functionalism too, need not be thrown out once it is cleansed of non-scientific assumptions and combined with other explanations of social change (Turner 2010). For example, the insight that powerful elites often act to increase their rewards and to maintain their privileges should not preclude us from recognizing that some institutionalized inequalities may be functional for non-elites as well as for elites. Complex and differentiated societies require integration and leadership in order to meet both internal and external challenges. The combination of the functional and conflict theories of stratification leads to the supposition that there is an optimal level of inequality for allowing societies to coordinate their activities and to meet challenges, and that inequalities beyond that optimal level are probably due to the action of elites who are using their advantages to exploit and dominate non-elites.[5]

Archaeologists and anthropologists distinguish between primary (or pristine) state formation and secondary state formation. Secondary state formation occurs when a stateless polity that is in interaction with one or more already existing states develops a noble/commoner class structure and builds a new state with specialized institutions of regional control. Pristine state formation refers to those more unique events in which a new state arises in a context in which there are no extant other states. Pristine state-formation occurred in at least six unconnected or very lightly connected regions: Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus River Valley, the Yellow River valley, Mesoamerica and the Andes.[6] Pristine state formation is much more difficult because, though all these instances occurred in regions where there were already complex chiefdoms, there were no existing states that could serve as exemplars of how to meet the organizational and resource challenges posed by the emergence of a large settlement (a city). The building of the global state is a similar challenge in which the institutions that have worked on smaller scales will be useful, but may not be up to dealing with new complications that emerge as part of the scaling up process.

Evolution of Interpolity Institutional Orders

The comparative world-systems perspective can be used for understanding the continuities and development of interpolity interactions and interpolity institutional orders. We will distinguish between a general notion of patterned interaction due to polities pursuing their own interests (anarchic geopolitics) and “interpolity governance” which will refer to interpolity systems in which institutions that allow cooperation as well as competition to emerge between polities and across their territorial boundaries.[7] Interpolity governance may exist, but be very weak. It becomes stronger when international organizations dedicated to general regulatory functions emerge, but these may have very low capacity to actually reduce conflict and promote cooperation. Every interpolity system, whether it is composed of bands or tribes or chiefdoms or states, exhibits patterned interactions with its neighbors. This may be only based on the alliances and enmities that constitute a system of competing and conflicting polities, or it may also involve additional practices such as trade, tribute payments and shared cultural understandings. As Georg Simmel (1955) and many others have noted, conflict is a form of structured sociation that produces order and repeated patterns both within and between societies. The kinds of institutional structures and shared ideational understandings in such systems have varied greatly depending on the nature of religions and ethnic identities and the abilities of peoples from different polities to communicate with one another (Buzan and Little 2000). The main evolutionary history of these interpolity systems is the story of the emergence of larger and more complex polities, and of the development of institutions that structure interpolity and transpolity interaction and that allow cooperation to occur as well as conflict.

The big differences between interpolity systems are the size and complexity of the polities that are interacting. Bands were very small. Empires were very big and complex. These entities also became more internally differentiated and developed greater internal hierarchy as they got larger. Technologies and organizational instruments, what Michael Mann (1986) has called “techniques of power” were developed that allowed powerful centers to extract resources from people who were a long way away from the center. Thus did core/periphery hierarchies become an important component of the processes of socio-cultural evolution.

What do we mean by the term “state”? A state is a

type of polity, so it is a spatially-bounded realm of sovereign authority.

States differ from chiefdoms because they are typically larger in both

population and territorial size, and they have specialized institutions of

regional control such as dedicated bureaucratic organizations and full-time or

dedicated bodies of armed men (which chiefdoms do not). We are also partial to

Max Weber’s definition of a state as holding a monopoly of legitimate violence,

at least in theory.[8] By

these definitions we may compare the internal power of states one to another.

Each state in an interpolity system has two faces of power –

internal and external. Its external power is relative to the other states with

which it is interacting, typically indicated by its military or economic

capabilities. Internal state strength is the power of the government as an

organization vis a vis internal groups that might resist or obstruct

state regulation and activity. This is the kind of state strength we will be

mainly considering here because we are comparing national states with a

hypothetical global state that would only have internal state strength. Charles

Tilly’s (2007) recent book about democracy clearly lays out the issues involved

in analyzing internal state strength. Conventional measures of internal state

strength are discussed below.

In this perspective the interstate system that emerged in Europe in the seventeenth century was a late-comer that was able to take advantage of the institutional heritages that were handed down from a long evolutionary past. This obviously included the institutions of feudal Europe and the norms of diplomacy and respect for sovereignty that had developed among the city-states of the Italian peninsula. But it also included the heritage from the classical Western world, especially the Roman Empire, and also the economic institutions, productive and navigational technologies as well as the political, economic and religious institutions that had diffused from the Islamic world, Africa and East and South Asia.

Balance of power dynamics and the geopolitical logic of coalition-formation existed in all earlier interpolity systems, including those of interchiefdom systems as well as among early states and empires. Many scholars of the European interstate system suppose that the inscribed notion of “general war”[9] and the institutionalized option of equal and symmetrical relations among polities were original innovations in the European international system for the first time (e.g. Modelski 1964). Whether or not this is true, the Westphalian system has been the most important institutional structure of interpolity governance in the modern (European) world-system, and it was extended to the whole globe as a result of the waves of decolonization of the European colonial empires that began in the eighteenth century. Another important leg of interpolity governance in the modern world-system has been the hegemonic sequence. World orders have been structured by the economic and political/military rise and fall of three capitalist hegemons: the Dutch in the 17th century, the British in the 19th century and the U.S. in the 20th century. This evolutionary sequence has constituted interpolity governance by means of hegemony, interspersed by periods of hegemonic rivalry and world revolutions.[10] In our conceptualization of the evolution of interpolity governance there is a spiraling systemic interaction between the powerful elites led by the hegemons and the peasants and workers of the world, most of whom live in the Global South (the non-core). World revolutions are rebellions and movements that cluster together in time, and become problems for the centers of power because they must be confronted simultaneously (Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000; Chase-Dunn and Niemeyer 2008). The third leg of the modern system emerged after the Napoleonic Wars – international political organization.[11] The Concert of Europe was a somewhat informal and halting effort, but it was followed by the League of Nations, the United Nations and the international financial institutions that emerged after World War II. Thus the three institutional legs of contemporary global interpolity governance are:

· the interstate system,

· the hegemonic sequence, and

· international organizations.

David Wilkinson and other IR theorists have contended that the unusual extent to which Westphalian system has institutionalized its commitment to general war is one important reason for the longevity of the modern interstate system and its ability to resist conversion into a core-wide empire. We agree that the institutional nature of the modern interstate system has been important, but another important feature of the modern interstate system has also played a large role in its resistance to the formation of a core-wide “universal” empire. That is the unusually large role played by capitalism in the accumulation of wealth and power. The main power-balancers in this system (the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the United Kingdom of Great Britain) were also the most capitalist core states. As such they relied on commodity production, financial services and colonial empires rather than tribute extraction from adjacent conquests. Thus has the rising predominance of capitalism in the Europe-centered world-system played an important part preventing the formation of a world empire. It was not a case in which there were no efforts to create such a core-wide empire. Both Napoleonic France and twentieth century Germany made strong bids. But the capitalist hegemons were able to mobilize a coalition large enough to preserve the multicentric structure of the modern core (Chase-Dunn 1990; Chase-Dunn 1998, Chapters 7-9).

Clearly most contemporary national states have greater internal power with regard to a monopoly of legitimate violence than does the existing global proto-state – the United Nations and the international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization. In federal states, the composite provinces are not allowed to make war on one another, whereas national states can legitimately make war with other states and yet remain within the United Nations. This is why we use the term proto-state when referring to the U.N. and the IFIs. Below we discuss ideas about how to measure global state formation quantitatively.

Thinking Global State Formation

Understandings of global state formation are confused by the fact that nearly all human polities in the past have existed in close proximal relations with other independent polities. Even so-called “universal empires” interacted with other polities at their borders. This condition, which we agree is fundamental to understanding the processes of social change, has also produced a situation in which “the state” is often partly defined with regard to its interaction with other states. This fact makes it difficult for some theorists to think about a single global state, because there would be no “foreign relations.” We certainly agree that many of the processes of polity formation in the past have been importantly caused by interactions among polities, obviously including warfare. Charles Tilly’s (1975) dictum about the history of European state formation: “the state makes war and war makes the state” has been true. But we disagree that this insight means that world state formation is impossible by definition. We note that so-called “internal” processes, including population pressure, technological innovations, conflicts within and between classes, and fiscal crises have been important in the formation of states in the past and could be the kinds of processes that push toward global state formation. Indeed warfare among states itself may be the best reason to construct a global polity that can resolve conflicts peaceably. But a global state has to be thinkable before we can cogitate about how one might emerge and how that process might be accelerated.

Another factor that has made it hard to think about global state formation is the institutionalization of the Westphalian international system. International relations theorists who focus mainly on the West have come to think of an interstate system with a number of competing “great powers” as the norm. This did indeed become the norm with the rise of capitalism in Europe. But earlier interstate systems were periodically transformed into core-wide empires in which a single “universal state” became the 800 pound gorilla of the system. Indeed the East Asian network of fighting and allying states remained such a system until it was incorporated into the Europe-dominated state system in the 19th century. In the modern Europe-centered system this pattern of core-wide empires was transformed into the rise and fall of hegemonic core states. The hegemons predominated, but they did not conquer the other core states. As capitalism rose to become the predominant mode of accumulation in the Europe-centered world-system, the main pattern of interpolity domination shifted from tributary empires constructed by conquering adjacent core states to colonial empires in which a set of competing core states subjugated distant colonies in the noncore. The strategy of core-wide empire did not disappear, but those efforts that were made along this line by Napoleonic France and Germany in the 20th century were defeated by capitalist hegemons and their allies. Thus did the system of states and the reproduction of a core composed several autonomous states, rather than a single “universal” state, come to be the new normal. This is another factor that makes it difficult to think about global state formation.

But globalization, and consciousness of it, have come along to challenge the verities of the institutionalized interstate system. The acceptance of the idea of a single global economy makes a single global political system thinkable. And much of the discourse about globalization has focused on the claim that national states have lost sovereignty vis a vis transnational corporations and the global market place. The world-systems perspective on globalization is that there have been waves of large-scale integration all along and that the wave since World War II needs to be understood by comparing it for similarities and differences with earlier waves, especially the one that occurred in the nineteenth century (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000).

Some scholars contend that global state formation is impossible because state formation and socio-cultural evolution in general are caused mainly by competition among states -- both warfare and economic competition, and so a single standing by itself is impossible (e.g. Turchin and Gavrilets 2009). Social cooperation and integration occur mainly because polities that do it can outcompete polities that do not do it. So those that do not get conquered or exploited by those that do. But even in the successful polities social integration breaks down because of the free-rider problem and so external threats are necessary to revive it. In the absence of external threats social order would break down and there would be nothing to revive it. There is a constant within-polity selection favoring free riders, and eventually all polities succumb to it. This is primarily cultural, but there may be also a genetic component to it. So social norms promoting cooperation and suppressing selfishness are replaced by norms that are permissive or even promote selfishness ("greed is good"). At some point the polity becomes unable to maintain itself and is replaced (e.g., conquered) by another one with functional social norms (promoting cooperation etc). The selfish norms are replaced wholesale by cooperative norms, but then the process of degradation resumes, until another carrier of prosocial norms sweeps in.

The major assumption in this approach is that the selection pressures in favor of cooperation and organization are external, resulting from interpolity competition. It is undoubtedly true that intersocietal competition is an important factor in socio-cultural evolution. But this approach ignores the existence of strong internal factors, and the possibility that institutions of interpolity cooperation can emerge that alter the dynamics of interpolity relations. So this approach tends to exclude the possibility of world government by its emphasis on the necessity of external competition. This is a substantive argument that we should keep in mind when we are considering how proto-global state formation has already occurred, and how a stronger, more capable and more democratic world government might emerge in the future.State Formation

Thus global state formation is often ruled out by definition. But those who do consider it to be at least a theoretical possibility usually see it as something that is not likely to happen for a long time. Some observers of human socio-cultural evolution predict the emergence of a single Earth-wide state based on the long term trend in which polities to get larger and larger. Projecting from historical trends, Raoul Naroll(1967) forecasted a .40 probability of a world state emerging by 2125 and a .95 probability by 2750. Naroll’s student, Louis Marano(1973), predicted a world empire around 3500 C.E. Robert Carneiro (2004) projected the decline in autonomous political units from 600,000 in 1500 B.C.E. to a single global government in 2300 C.E. The main point of this essay is to consider those factors that might speed up global state formation, allowing it to happen within the next few decades.

But before we tackle that we will review theories of state formation, using the distinction we have developed between cycles and upward sweeps. As we have already mentioned, the largest polities within a region display a cycle of rise and fall. The recovery of the same or a different polity within the same interaction network (regional world-system) usually attains a size that is similar to the earlier peak. But sometimes a new, much larger size is attained. These latter cases we call upward sweeps or upsweeps. We will contend that it is valuable to distinguish between the causes of cyclical recovery and the causes of the much less usual upsweeps and to investigate the relationships among all these causes.

Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov (2009) have developed Jack Goldstone’s (1991) neo-Malthusian demographic-structural theory of the dynamic interactions among population growth (and decline), resources, expansion of numbers and consumption by elites, political instability and state formation and collapse. Turchin and Nefedov examine eight cases of the rise and fall of agrarian dynasties in order to test their model of the “secular cycle” in which population growth causes pressure on resources, prices rise, remunerations to labor fall, the numbers and consumption levels of elites grow, political instability increases because peasants rebel and elites fight amongst themselves, states experience fiscal crises and collapse, population goes down because people die from famines, epidemics and wars, and then the cycle starts up again.

This model of the dynamical causes of state rise

and fall is similar to the iteration model mentioned above except that, rather

than including a set of interacting polities (a world-system) as the unit of

analysis, it focuses on the internal causes within each polity. External

processes such as climate change, attacks from abroad, and epidemics from

abroad are treated as exogenous factors that sometimes impact what is happening

within each polity. One thing that needs to be done is to build and test a

model that endogenizes some of these exogenous factors by considering the

dynamics of interpolity systems. As Turchin and Nefedov point out, regions

within polities as well as polities as a whole are sometimes not in synchrony,

whereas at other times they are. And there are interesting instances of lagged

synchrony – for example the enserfment waves that first succeeded in Eastern

Europe and then happened in Russia two centuries later (Turchin and Nefedov

2009:255). Whether or not demographic and class struggle cycles are in

synchrony across regions and states has huge implications for system-wide

dynamics. And interpolity systems have emergent properties and relational

characteristics that are generally not present within polities, such as waves

of hegemony and core/periphery structures. It would be very useful to have a

well worked out model of world-system secular cycles before we tackle the more

difficult issues of explaining upsweeps and evolution.

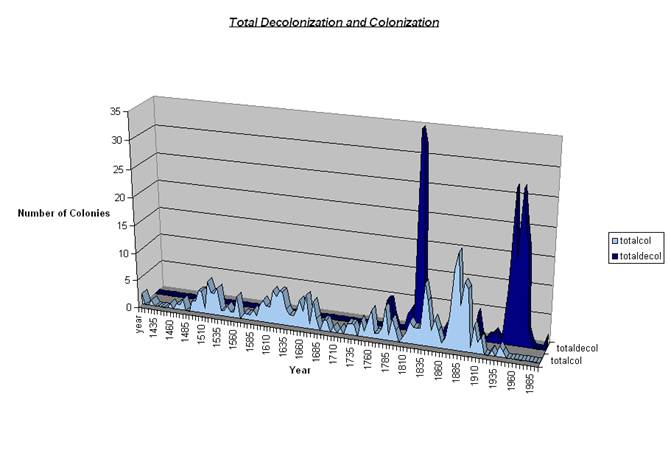

Figure 1: Waves of colonization and decolonization based on Henige (1970)

The approach that we propose is to model the main causes of state formation and upward sweeps taking into account the ways in which these basic processes have been altered by the emergence of new institutions. We will elaborate and improve upon the recent work of Robert Bates Graber (2004). Graber develops two models, which he calls “ahistorical” and “historical.” Both are population pressure models of political integration. His “ahistorical” model is a very simplified version of the iteration model discussed above that includes population growth rates and the number of independent polities. Graber’s “historical” model takes account of the emergence of the League of Nations and the United Nations, as our approach does. But we add the rise and fall of hegemons, the emergence of markets and capitalism, and the growth of other international political organizations and non-governmental organizations model political globalization and global state formation.

As we have said above, the main political structure of the modern world-system has been, and remains, the international system of states as theorized and constituted at the Peace of Westphalia. This international system of competing and allying national states was extended to the periphery of the modern world-system in two large waves of decolonization of the colonial empires of core powers. The modern system differed from earlier imperial systems in that its core remained multicentric rather than being occasionally conquered and turned into a core-wide empire. Instead, empires were organized as distant peripheral colonies rather than as conquered adjacent territories. This strategy of colonial imperialism had been pursued earlier by thallasocratic states, mainly semiperipheral capitalist city-states that specialized in maritime trade. In the modern system this form of colonial empire became the norm, and the European core states rose to global hegemony by conquering and colonizing the Americas, Asia and Africa in a series of expansions (see Figure 1). The international system of sovereign states was extended to the colonized periphery in two large waves of decolonization (see Figure 1). These waves of decolonization occurred in the context of the world revolutions of 1789 and 1917, and were thus part of the evolution of global governance. After a long-term trend in which the number of independent states on Earth had been decreasing, that number rose again. And with decolonization the core states decreased in size when they lost their colonial empires and the size of the average state decreased because most of the former colonies were not large. This counter-trend to the millennial fall in the total number and rise of the average size of polities has made it harder for those who focus only on recent centuries to comprehend the long-term rise of political globalization and global state formation.

Extension of the State System to the Periphery

The decolonization waves were part of the formation of a global polity of states. And one of the decolonized regions became “the first new nation,” and eventually rose to hegemony to become the largest hegemon the modern system has seen – the United States. The doctrine of national self-determination, long a principle of the European state system, was extended to the periphery.

This multistate system has also experienced waves of international political integration that began after the Napoleonic Wars early in the nineteenth century. Britain organized a “Concert of Europe” (Jervis 1985) that was intended to prevent future French revolutions and Napoleonic adventures. During the middle of the nineteenth century a large number of specialized international organizations emerged such as the International Postal Union (Murphy 1994) that underwrote the beginnings of a global civil society that included more than elites, and this network of transnational voluntary associations grew much larger during the most recent wave of economic globalization since World War II (Boli and Thomas 1999). After World War I the League of Nations was intended to provide collective security, though it was seriously weakened because the United States did not join. After World War II the United Nations became a proto-world-state, the efficacy of which has waned and waxed since then. The system of national states is being slowly overlain by global and regional transnational political organizations that blossom after periods of war and during periods of economic globalization.

Our historical model adds marketization, decolonization, new lead technologies, the rise and fall of hegemons, and the rise of international political organizations to the population pressure model in order to forecast future trajectories of global state formation. We will also take into account the structural differences between recent and earlier periods. For example, the period of British hegemonic decline moved rather quickly toward conflictive hegemonic rivalry because economic competitors such as Germany were able to develop powerful military capabilities. The decline of U.S. hegemony has been different in that the United States ended up as the single superpower after the demise of the Soviet Union. Economic challengers (Japan and Germany) cannot easily use the military card because they are stuck with the consequences of having lost the last World War. This, and the immense size of the U.S. economy, will probably slow the process of hegemonic decline down relative to the speed of the British decline. Modeling the global future should also consider changes that have occurred in labor relations, urban-rural relations, the nature of emergent city regions, and the shrinking of the global reserve army of labor (Silver 2003).

The Causes of Upward Sweeps

Above we mentioned that upward sweeps probably have somewhat different causes and necessary conditions than do recovery cycles. And there may be different kinds of upward sweeps that have different causes. The most usual kind of upward sweep is carried out by a semiperipheral marcher state that uses the marcher advantage to roll up the system. This usually occurs when there is an adjacent multistate region that is worth conquering because a surplus of food or other resources is being produced that can be appropriated by the conquering state. Thus the big empires generally expanded into regions where agriculture had already emerged. They also expanded to control valuable trade routes. The point here is that an upward sweep of state formation is risky and expensive, and it does not pay to conquer and subjugate poor regions where no economic surplus can be appropriated. Thus the development of productivity in distant regions is an important condition for an empire upward sweeps. Upward sweeps are also facilitated by innovations in military weapons, as well as transportation, communications and production technologies. The formation of a larger state or empire requires the appropriation of great resources, and the institutional ability to bring off this appropriation.

In the modern world-system the series of successful hegemons have been facilitated by generative economic sectors and new lead technologies that have funded successful performance in world wars and profitable accumulation by means of production for the world market (Modelski and Thompson 1996; Bunker and Ciccantell 2005). New lead technologies generate both profits and revenues. Revenues are important for the fiscal health of national states. Staying ahead of the product cycle by developing new high technology products is a key to the rise of challengers and to the maintenance of the hegemony once it is attained.

Hegemony also has an ideological dimension, as argued by Antonio Gramsci (1971; Gill 2003). It is part coercion and part consent. The consent part is obviously facilitated by economic success and the ability to reward loyal allies. And the ideological basis is also important. Britain suppressed the slave trade, thus taking high ground in the global moral order. The U.S. claimed to be the leader of global democracy and ‘the first new nation.” It provided some support for the decolonization of the colonial empires of other core powers, albeit while negotiating the placement of a global network of military bases at the same time. Hegemony and global leadership generally, requires universalistic ideals. These ideals have been formed in the struggles that constitute the series of world revolutions. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was the result of movements from below asserting rights. These rights are not universally recognized even by the core states. But they are the precipitate of a long-term historical contest over global governance in which social movements have become increasingly transnational. This is an element that needs to be considered in our discussion of speeding up global state formation below.

As it has been explained in earlier work, we have developed an “Iteration Model” that explains the evolutionary formation of hierarchy and technological innovation of world-systems. Applying this comprehensive model, yet reflecting the arguments we made so far, we observe that some key mechanisms are more significant than others in actual modeling of global state formation. A couple of such factors that are distinct in the case of modeling global state formation are listed as follows.

In thinking about global state formation, given the fact that there are no competing polities outside the Earth, for the foreseeable future it is highly unlikely that there will be warfare or economic competition between the world government and other human polities. So there will be external pressures that enforce centralization at the global level. The values placed on the variables that are related with external warfare in the evolutionary model will be reduced or eliminated in the maintenance of the world government. But warfare and economic competition may play important roles in the emergence of world government. In this sense, a model of the maintainance of a global state will be similar to those models of the dynamics of state formation that focus primarily on internal forces.

As it has been discussed above and in earlier works, locational dynamics—"semiperiphery development"— is one of the significant theoretical as well as empirically-supported mechanisms for the emergence of much larger-scale polities. Similar processes are explained in some historical studies with cultural dynamics. Large-scale polities are more likely to develop in meta-ethnic frontier regions (Khaldun 1958; Turchin and Nefedov 2009). This is partly due to the intensity of warfare with the high level of threats caused by the encounter of culturally heterogeneous populations (Turchin and Gavrilets 2009). The same dynamics are again endogenized in the modeling of global state formation. In combination with spatial dynamics, warfare and economic competition as selection mechanisms for the emergence of a larger polity are important factors for semiperipheral development in global state formation modeling. Likewise, we contend that selection mechanisms operating on technological competition in combination with spatial dynamics also forms another decisive mechanism for semiperipheral development toward global state formation. It has been convincingly shown with historical data that technological innovation has affected expansion and the rate of the expansion toward formation of a larger political units (Hart 1944, 1948).

Measuring Global State Formation

We conceptualize global state formation analogously to our understanding of economic globalization as the relative strength and density of larger versus smaller interaction networks and organizational structures (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000). Much has been written about the emergence and development of global governance and many see an uneven and halting upward trend in the transitions from the Concert of Europe to the League of Nations and the United Nations toward the formation of a proto-world state. The emergence of the Bretton Woods institutions (the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank) and the more recent restructuring of the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade as the World Trade Organization, and the visibility of other international fora (the Trilateral Commission, the Group of Eight; the World Economic Forum, the World Social Forum meetings, etc.) support the idea of an upward trend toward political globalization. The geometric growth of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) is also an important phenomenon the emergence of global civil society (Murphy 1994; Boli and Thomas 1999).

We propose to quantitatively operationalize global state formation. The cross-national quantitative literature uses several operationalizations of internal state strength of national states, such as central government revenues as a percentage of GDP, military expenditures per capita, etc. For global state formation we could use analogous indicators, such as the size of the U.N budget (or that plus the budgets of the international financial institutions) as a ratio to the world GDP or world population. We could also use the U.N. expenditures on peace-keeping forces as a ratio to world GDP or population. These would be strictly analogous to the most frequently used indicators of internal state strength of national states. But there is a big difference between the structure of global governance and the structure of national governance that needs to be taken into account in our measures: the issue of the monopoly of legitimate violence. The strength of most national central governments does not need to take into account the size of lower levels of jurisdiction, because national governments enjoy a monopoly of legitimate violence in the sense that subjurisdictions (provinces, cities, counties) do not have the right to fight one another militarily. That is not the case at the global level, and so an indicator of global state formation needs to take into account the size of the central proto-state relative to the sizes of the “substates” – the national states.[12] Thus we propose to use two kinds of indicators of global state formation that can be quantitatively estimated over time:

1. the operating budget of the UN plus the other global level institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization as a ratio to the size of the whole world economy, and per capita (relative to the whole population of the Earth), and

2. the rank of the operating budget of the UN plus the other global level institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization in the ranked distribution of central government revenues of national states, and changes in this rank over time.

Many observers now agree that the hegemony of the United States is in decline. World-systems theorists and some others have been talking about this since the 1970s. Giovanni Arrighi’s (1994) analysis of “systemic cycles of accumulation” presents an evolutionary model of the modern world-systems trajectory over the past 600 years that includes careful comparisons of the similarities and differences of four hegemonies. Arrighi notes that financialization is a strategy that is adopted by wealthy elites and promoted by powerful states during the latter phases of a systemic cycle of accumulation as the profit rate goes down in manufacturing and trade. Arrighi also carefully examines the differences between the period in which the U.S. is declining and the conditions that existed at the end of the 19th century and early decades of the 20th century when the British hegemony was in decline.

The recent global financial crisis seems to have convinced many of those who were ignoring the earlier signs of U.S. hegemonic decline. From the point of view of hegemonic stability theory, the problem is to get through the “inter-regnum” to a new form of legitimate global governance that can address the many serious problems that are global in scope and that contending national states cannot well address individually. First on the list of such problems is hegemonic rivalry and the potential for warfare to once again break out among the great powers. Most observers agree that this is very unlikely as long as the U.S remains the single superpower. But if the U.S. continues to decline, the costs of maintaining its 787 military bases across the globe may cease to be possible. If that comes to pass the interstate system could return to a multicentic power configuration similar to that which existed just before World War I. Hegemonic rivalry in such a power configuration would be very dangerous because of the existing weapons of mass destruction.

Other problems that need globally coordinated attention and might benefit from a legitimate and capacious world state are:

· global inequalities. The U.N. Millenium Development goals are good but will probably not be attained, and

· Ecological degradation, peak oil, potential disasters from global warming, etc.

· Additional financial collapse. The mountain of fictitious capital beyond the “real economy” has not been much reduced by the financial collapse up to now. If further disruptions occur, coordinated action will be desirable and global regulation of finance capital could help avert disasters of this type in the future.

· a failed system of global governance in the wake of U.S. hegemonic decline.

Despite our world historical and evolutionary approach to social change, we agree with most other analysts the human history is open-ended. What will happen depends on what we and other people do. The election of Barack Obama to the Presidency of the United States is perhaps a good reminder that the outcomes of conjunctures are not completely predictable. This said, it is possible to use our knowledge of the human past to make predictions about possible futures. Elsewhere (Chase-Dunn and Lawrence 2010) we have proposed that the major structural alternatives for the trajectory of the world-system during the twenty-first century by positing three basic scenarios (and then discussing possible combinations and changing sequences):

1. Another round of U. S. economic hegemony based on comparative advantage in new lead industries and another round of U.S. political hegemony (instead of supremacy).

2. Collapse: further U.S. hegemonic decline and the emergence of hegemonic rivalry among core states and with rising semiperipheral states. Deglobalization, financial collapse, economic collapse, ecological disaster, resource wars and deadly epidemic diseases.

3. Capable, democratic, multilateral and legitimate global governance strongly supported by progressive transnational social movements and global parties, semiperipheral democratic socialist regimes, and important movements and parties in the core and the periphery. This new global polity accomplishes environmental restoration and the reduction of global inequalities. It is in the context of these scenarios that our consideration of accelerating global state formation and democratization of global governance will procede.

Accelerating Global State Formation

How might global state formation and the democratization of global governance be accelerated? We will discuss several factors that are likely to have implications for the effort to accelerate the emergence of global governance. Theoretically, the issue can usefully be analyzed at different levels— the national state and the organizational level, and the global, or very macro level. In other words, some of the dynamics are observable as a bottom-up process, while others may be top-down processes, or a combination of the two. We have to examine under what conditions, bottom-up, social movements transform national political economies most successfully and effectively. We also need to investigate if the same conditions operate similarly at the global level. Further, we need to consider what conditions are the most effective in performing top-down institutional transformation and we need to know whether the same conditions are applied at the national as well as world-polity level.

Among the mechanisms that we have dsicussed so far, one of the strong causes for a large-scale transformation toward a global polity revolves around semiperipheral dynamics, which is a bottom-up mechanism for social transformation. An additional, yet interrelated, strong mechanism is warfare dynamics. As our iteration model shows, within-polity conflict and inter-polity warfare form a strong selection pressures for political integration.

As it has already been discussed, evolutionary history tells us that developments from semiperiphery oftentimes attain expanded, large-scale polity formation. Are the movements from semiperiphery—such as semiperiphery upsweeps or semiperipheral marcher state formation—revolutionary, rapid change or slower evolutionary transformation? Literature on organizational and institutional change suggests that rapid and dramatic change is short-lived and does not survive. Many small changes over time are more likely to produce successful and long-lasting transformation (Coser 1956). Semiperipheral development is oftentimes a formation of a gradual and cumulative change, although the expansion is characterized by sudden territorial expansion (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997).

Numerous studies on social change have indicated that technology is one of the critical conditions for accelerating institutional changes. David Harvey (1989) has noted the phenomenon of “time-space compression” that has accompanied the transition to flexible accumulation and globalized capitalism. Technological change has certainly speeded up and social change in general may have speeded up as well. The world revolutions seem to have begun to overlap one another.[13] This may mean that the evolution of global governance might also speed up.

Technological change is probably also important for producing the conditions that would be needed for global state formation. We have noted the importance of new lead industries in the process of hegemonic rise and fall. New lead industries might also facilitate global state formation. The ability to use less expensive fuels in generative sectors was important for both the British (coal) and the U.S. rise (oil). If some new technological fix could produce another source of cheap energy this could help provide the resources needed for a more rapid global state formation. Unfortunately some now contend that the fossil fuel party is soon to be over, and that no new source of cheap energy is likely to come about for awhile. If this is true the energy part of the equation could slow things down, or make it necessary to pursue a low-energy strategy of global state formation.

Technological changes certainly accelerate the institutional transformation. At the same time, it brings up cultural and structural “lags” (Vebren 1915/1964). Technological change does not necessarily connect to the instant institutional change since cultural norms, laws, already existing interest relations create a lag-time for actual prosecution. How such lag effects play out at global world-system level is also be an interesting question.

All the previous advances in global state formation have taken place after a hegemon has declined and challengers have been defeated in a world war among hegemonic rivals. In Warren Wagar’s A Short History of the Future (1999) a global socialist state is able to emerge only after a huge war among core states in which two thirds of the world’s population are killed. A somewhat similar scenario has been suggested by Heikki Patomäki (2008) and Jacques Attali (2009). The idea here is that major organizational changes emerge after huge catastrophes when the existing global governance institutions are in disarray and need to be rebuilt. But using a global war as a deus ex machina in a science fiction novel is quite different from planning and implementing a real strategy that relies on a huge disaster in order to bring about change – “disaster socialism,” to invent a phrase suggested by Naomi Klein’s (2007) discussion of how neoliberal globalizers have been able to make hay out of tragedies. Obviously political actors who seek to promote the emergence of an effective and democratic global state must also do all that they can to try to prevent another war among the great powers. Humanistic morality must trump what ever advantages might result from such a catastrophe.

This said, it is very likely that major calamities will occur in the coming decades regardless of the efforts of far-sighted world citizens and social movements. And it would make both tactical and strategic sense to have plans for how to move forward if indeed a perfect storm of calamities were to come about.

But let us try to imagine how an effective and democratic global government might emerge in the absence of a huge calamity. Instead we will suppose that a series of moderate-sized ecological, economic and political calamities that are somewhat spaced out in time can suffice to provide sufficient disruption of the existing world order and motivation for its reconstruction along more cooperative, effective and democratic lines.

The scenario we have in mind involves a network of alliances among progressive social movements and political regimes of countries in the Global South along with some allies in the Global North. We are especially sanguine about the possibility of relatively powerful semiperipheral states coming to be controlled by democratic socialist regimes that can provide resources to progressive global parties and movements. The long-term pattern of semiperipheral development that has operated in the socio-cultural evolution of world-systems at least since the rise of paramount chiefdoms suggests that the “advantages of backwardness” may again play an important role in the coming world revolution (Chase-Dunn and Boswell 2009).

One scenario would involve a coalescent party-network of the New Global Left that would emerge from the existing “movement of movements” that have been participating in the World Social Forum. Positive historical exemplars of direct democracy are the various workers’ councils that appeared during the Paris Commune of 1871, the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Spanish Revolution of 1936-1939, the Chilean Revolution of 1970-1973, and the Seattle General Strike of 1919. Similar forms have recent emerged in the factory committees in Argentina and Venezuela and peasant councils in Brazil (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2008). Recent decades have seen the further expansion of transnational social movements (Moghadam 2005; Reitan 2007; Smith 2008). The World Social Forums (WSF), established as an alternative to the World Economic Forum, have been remarkable efforts to build the foundation for a just and democratic world. The WSF events are open spaces of dialogue, where members of the “movement of movements” organize to oppose neoliberal globalization.

Semiperipheral Russia, trying to regain global status after the demise of the Soviet Union, has called for a more democratic world order. The Russian government hosted a conference in 2009 to foster an alliance among some of the semiperipheral countries: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. For millennia new visions and actualized dramatic changes in the hierarchal structure of world-systems have emerged from semiperipheral societies. The so-called “Pink Tide” of recent populist regimes in Latin America represent a renewed challenge to the predominance of global capitalism and perhaps the prefigurative appearance of a 21st century socialism (Robinson 2008).

Another way to speed up global state formation would be for the United Nations to take over command of the U.S. global military apparatus. The defacto situation is that a global state already exists. It is the United States. Superpower status, with no serious challengers to U.S. military supremacy, means that the U.S. is the defacto holder of a near- monopoly of violence, but it is not legitimate because the Commander-In-Chief is elected by the citizens of the U.S., not by the citizens of the Earth. This could be quickly fixed by democratizing the United Nations and transferring control of the global military to it. Of course, this is very unlikely to happen, but it is a useful mental exercise. The institutional elements of a global democratic state already exist. But they would need to be restructured and rearranged. The task at hand is how to move these pieces around quickly and to avoid the worst excesses of the kind of interregnum that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, what Eric Hobsbawm (199x) has called “the Age of Extremes.”

We have not attained our goal of developing a plan for accelerating democratic global governance. But we have explained the perspective from which such a plan needs to emerge.

References

Álvarez, Alexis, Hiroko Inoue, Kirk Lawrence, James Love, Evelyn Courtney and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2010 “Upsweep Inventory: Scale Shifts of Settlements and Polities Since the Stone Age” Social Science History.

Anderson, David G. 1994 The Savannah River Chiefdoms. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Archibugi, D 2008 The Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth Century. London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos and Governance in the Modern World-System: Comparing Hegemonic Transitions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Attali, Jacques. 2009. A brief history of the future: a brave and controversial look at the twenty-first century. Trans. by J. Leggatt. New York: Arcade.

Bergesen, Albert and Ronald Schoenberg 1980 “Long waves of colonial expansion and contraction 1415-1969” Pp. 231-278 in Albert Bergesen (ed.) Studies of the Modern World-System. New York: Academic Press

Boli, John and George M. Thomas 1997 “World culture in the world polity,” American Sociological Review 62,2:171-190 (April).

__________ (eds.)1999 Constructing World Culture: International Nongovernmental Organizations Since 1875. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bornschier, Volker and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.) The Future of Global Conflict. London: Sage

Boserup, Ester1981. Population and Technological Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boswell, Terry and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral of Capitalism and Socialism. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner.

Bunker, Stephen and Paul Ciccantell 2005 Globalization and the Race for Resources. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Buzan, Barry and Richard Little 2000 International Systems and World History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cabrera, Luis 2010 “World government: renewed debate, persistent challenges” European Journal of International Relations 20,10:: 1-20.

Carneiro, Robert L. 1978 “Political expansion as an expression of the principle of competitive exclusion,” Pp. 205-223 in Ronald Cohen and Elman R. Service (eds.) Origins of the State: The Anthropology of Political Evolution. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

________ 2004 “The political unification of the world: whether, when and how – some speculations.” Cross-Cultural Research 38,2:162-177 (May).

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 1990 "World state formation: historical processes and emergent necessity" Political Geography Quarterly, 9,2: 108-30 (April). https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows1.txt

Chase-Dunn, Christopher 1998 Global Formation: Structures of the World- Economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Alexis Alvarez, and Daniel Pasciuti 2005 "Power and Size; urbanization and empire formation in world-systems" Pp. 92-112 in C. Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The Historical Evolution of World-Systems. New York: Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Salvatore Babones (eds.) Global Social Change: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Terry Boswell 2009 “Semiperipheral devolopment and global democracy” in Phoebe Moore and Owen Worth, Globalization and the Semiperiphery: New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Chase-Dunn, C. Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 “Trade globalization since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system” American Sociological Review 65,1:77-95.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Kirk Lawrence 2010 “ The Next Three Futures” Another U.S. Hegemony, Global Collapse or Global Democracy?” Global Society. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows47/irows47.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. Thomas Reifer, Andrew Jorgenson and Shoon Lio 2005 "The U.S. Trajectory: A Quantitative Reflection, Sociological Perspectives 48,2: 233-254.

Chase-Dunn C. and Ellen Reese 2007 “Global political party formation in world historical perspective” in Katarina Sehm-Patomaki & Marko Ulvila eds. Global Political Parties. London: Zed Press.

Chase-Dunn, C. and R.E. Niemeyer 2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” Pp. 35-57 in Mathias, Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational Political Spaces. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/New York

Chase-Dunn, C. Richard Niemeyer, Alexis Alvarez and Hiroko Inoue 2009 “Scale transitions and the evolution of global governance since the Bronze Age” Pp. 261-284 in William R. Thompson (ed.) Systemic Transitions. New York: Palgrave MacMillan

Chase-Dunn, C. and Bruce Lerro 2008 “Democratizing Global Governance” Paper presented at the annual meetings of the International Studies Association, San Francisco, March 28.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Bruce Podobnik 1995 “The Next World War: World-System Cycles and Trends” Journal of World-Systems Research,Volume 1, Number 6, http://jwsr.ucr.edu/archive/vol1/v1_n6.php

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Hiroko Inoue forthcoming The Evolution of Global Governance.

Chimni, B.S. 2004 “International institutions today: an imperial global state in the making” European Journal of International Law 15,1:1-37.

Collins, Randall 2010 “Geopolitical conditions of internationalism, human rights and world law” Journal of Globalization Studies 1,1: 29-45.

Conti, Joseph A. 2010 “Producing legitimacy at the World Trade Organization: the role of expertise and legal capacity” Socio-Economic Review 8,1:131-156.

Cook, J.A. 2007 Global Government Under the U.S. Constitution. Lanham, MD: University Press of

America.

Coser, Luis. 1956. Function of Social Conflict. Glencoe, Ill: Free Press.

Cox, Robert W. 2002 The Political Economy of a Plural World London: Routledge

Cutler, A. Claire 2010 “The legitimacy of private transnational governance: experts and the transnational market for force” Socio-Economic Review 8,1:157-186.

Craig, C. 2008 “The resurgent idea of world government” Ethics and International Affairs 21,2: 133- 142.

Curtin, Philip 1984 Crosscultural Trade in World History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Einstein, Albert 1956 “Towards a World Government” in Out Of My Later Years: the Scientist, Philosopher and Man Portrayed Through His Own Words New York: Wings Books.

Fligstein, Neil 2005 “The political and economic sociology of international economic arrangements” Pp. 183-204 in Neil J. Smelser nd Richard Swedberg (eds) The Handbook of Ecnomic Sociology (2nd ed.) Princeton: Princeton University Press

Gereffi, Gary 2005 “The global economy: organization, governance and development” Pp. 160-182 in Neil J. Smelser nd Richard Swedberg (eds) The Handbook of Ecnomic Sociology (2nd ed.) Princeton: Princeton University Press

Goldfrank, Walter L. 1999 “Beyond hegemony” in Volker Bornschier and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.) The Future of Global Conflict. London: Sage.

Goldstone, Jack A. 1991 Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Graber, Robert Bates 2004 “Is a world state just a matter of time?: a population-pressure alternative.” Cross-Cultural Research 38,2:147-161 (May).

________________ 2006 Plunging to Leviathn: Exploring the World’s Political Future. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Gramsci, Antonio 1971 Selections for the Prison Notebooks. New York: International Publishers

Gill, Stephen 2000 “Toward a post-modern prince? : the battle of Seattle as a moment in the new politics of globalization” Millennium 29,1: 131-140.

__________ 2003 Power and Resistance in the New World Order. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Haas, Ernst. 1966. "International integration: the European and the universal process," pp. 93- 130 in International Political Communities: An Anthology. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Hart, Hornell 1944. Can world government be predicted by mathematics? Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards.

___________1948 “The logistic growth of political areas” Social Forces ,4: 396-408.

Harvey, David 1989 The Condition of Postmodernity. Cambirdge, MA: Blackwell

Henige, David P. 1970 Colonial Governors from the Fifteenth Century to the Present. Madison, WI.:

University of Wisconsin Press.

Heylighen, Francis 2008 “Accelerating socio-technological evolution: from ephemeralization and stigmergy to the Global Brain” Pp. 284-309 in George Modelski, Tessaleno Devezas and William R. Thompson (eds.) Globalization as Evolutionary Process: Modeling Global Change. London: Routledge.

Hobsbawm, Eric 1994 The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991. New

York: Pantheon.

Johnson, Chalmers 2000 Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire. New York:

Henry Holt.

Jervis, Robert 1985 "From Balance to Concert: A Study in International Security

Cooperation," World Politics 38,1: 58-79

Klein, Naomi. 2007 The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Lawrence, Kirk. 2009 “Toward a democratic and collectively rational global commonwealth: semiperipheral transformation in a post-peak world-system” in Phoebe Moore and Owen Worth, Globalization and the Semiperiphery: New York:Palgrave MacMillan.

Love, James, Alexis Alvarez, Hiroko Inoue, Kirk Lawrence, Evelyn Courtney, Edwin Elias, Tony Roberts, Joseph Genoa, Victoria Autelli, Sean Liyanage, Joshua Hopps and Chris Chase- Dunn 2010 “Semiperipheral Development and Empire Upsweeps Since the Bronze Age” Presented at the annual meetings of the International Studies Association, New Orleans.

Mann, Michael 1986 The Sources of Social Power, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Marano, Louis A 1973 “A macrohistoric trend toward world government.” Behavior Science Notes 8,1, 35-39. Modelski, George. 1964. "Kautilya: foreign policy and international system in the ancient Hindu world," American Political Science Review 58, 3:549-60.Modelski, George and William R. Thompson. Seapower in Global Politics, l494-1993. Seattle, WA.: University of Washington Press.

Modelski, George and William R. Thompson. 1996. Leading Sectors and World Powers: The Coevolution of Global Politics and Economics. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina

Press.

Moghadam, Valentine 2005 Globalizing Women. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Monbiot, George 2003 Manifesto for a New World Order. New York: New Press

Murphy, Craig 1994 International Organization and Industrial Change: Global

Governance since 1850. New York: Oxford.

Naroll, Raul 1967 “Imperial cycles and world order,” Peace Research Society: Papers, VII, Chicago Conference, 1967: 83-101.

Parsons, Talcott 1966 Societies: Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

_____________1971 The System of Modern Societies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Patomaki, Heikki 2008 The Political Economy of Global Security. New York: Routledge.

Peregrine, Peter N., Melvin Ember and Carol R. Ember 2004 “Predicting the future state of the world using archaeological data: an exercise in archaeomancy.” Cross- Cultural Research 38,2: 133-146 (May).

Robinson, William R. 2004. A Theory of Global Capitalism. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press

_________________2008 Latin America and Global Capitalism. Roscoe, Paul 2004 “The problem with polities: some problems in forecasting global political integration” Cross-Cultural Research 38,2: 102-118.Santos, Boaventura de Sousa 2006 The Rise of the Global Left. London: Zed Press.

Service, Elman R 1975 The Origins of the State and Civilization. New York: Norton. Shaw, Martin 2000 Theory of the Global State: Globality as an Unfinished Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Silver, Beverly J. 2003 Forces of Labor: Workers Movements and Globalization Since 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Simmel, Georg 1955 Conflict and the Web of Group Affiliations. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.Smith, Jackie 2008 Social Movements for Global Democracy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.__________, Marina Karides, Marc Becker, Doval Brunelle, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Donatella della Porta, Rosalba Icaza Garza, Jeffrey S. Juris, Lorenzo Mosca, Ellen Reese, Peter (Jay) Smith and Roland Vazquez. 2008 Global Democracy and the World Social Forums. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Taagepera, Rein 1978a "Size

and duration of empires: systematics of size" Social Science Research 7:108-27.

______ 1978b "Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600 B.C." Social Science Research, 7 :180-96.

______1979 "Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D." Social Science History 3,3-4:115-38.

_______1997 “Expansion and contraction patterns of large polities: context for Russia.” International Studies Quarterly 41,3:475-504.

Taansjo, Torbjorn2008 Global Democracy: The Case for World Covernment. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Talbott, S. 2008 The Great Experiment: The Story of Ancient Empires, Modern States, and the Quest for a Global Nation. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Taylor, Peter 1996 The Way the Modern World Works: Global Hegemony to Global Impasse. New York: Wiley.

Tetalman, Jerry and Byron Belitsos 2005 One World Democracy. San Rafael, CA: Origin Press

Thompson, William R. 2008 “Measuring long-term processes of political globalization”Pp. 58-87 in George Modelski, Tessaleno Devezas and William R. Thompson (eds.) Globalization as Evolutionary Process: Modeling Global Change. London: Routledge.

Tilly, Charles (ed.) 1975 The Formation of national States in Western Europe.Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press.

___________2007 Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turchin, P. 2003. Historical dynamics: why states rise and fall. Princeton University Press,

Princeton, NJ.

Turchin, P., and T. D. Hall. 2003 “Spatial synchrony among and within world-systems: insights from theoretical ecology”. Journal of World Systems Research 9,1

http://csf.colorado.edu/jwsr/archive/vol9/number1/pdf/jwsr-v9n1-turchinhall.pdf

Turchin, Peter and Sergey A. Nefedov 2009 Secular Cycles. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Turchin, Peter and Sergey Gavrilets 2009 “Evolution of Complex Hierarchical Societies” Social History and Evolution 8(2): 167-198.

Turner, Jonathan H. 2010 Principles of Sociology, Volume 1 Macrodynamics. Springer Verlag

Veblen, Thorstein. 1915/1964. Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution. Augustus M. Kelley, New York.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984. “The three instances of hegemony in the history of the capitalist world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and Research in Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Weber, Max 1978 Economy and Society, Volume 1, Part 1, Chapter 1, Section 6, Pp. 33-36 “Types of legitimate order: convention and law” (Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich) Berkeley: University of California Press

Weiss, T. G. 2009 “What happened to the idea of world government? International Studies Quarterly 53,2:253-271.

Wendt, Alex 2003 “Why a world state is inevitable” European Journal of International Relations.9,4: 491-542.

Wilkinson, David. 1987 "Central civilization" Comparative Civilizations Review 17:31-59 (Fall).

______________1985 "States systems: ethos and pathos," a paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for the Comparative Study of Civilizations, Yellow Springs,Ohio, May 30- June l.

__________. 1986a. "State systems: pathology and survival," a paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for the Comparative Study of Civilizations, Santa Fe, New Mexico, May 29- 31.

__________. 1986b. "Universal empires: pathos and engineering," a paper presented to the annual meeting of the International Society for the Comparative Study of Civilizations, Santa Fe,

New Mexico, May 29-31.

_________ 1991 “Core, peripheries and civilizations,” Pp. 113-166 in C. Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.) Core/Periphery Relations in Precapitalist Worlds. Boulder, CO: Westview Press http://www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/books/c-p/chap4.htm

Yunker, James A. 2000 Common progress : the case for a world economic equalization program Westport, Conn. : Praeger

_______ 2007 Political globalization : a new vision of federal world government Lanham : University Press of America

Hornell Hart (1944) explained upsweeps of polity size with logistic growth.

Paul Roscoe (2004) says:

Hornell Hart (1944; see also 1948) was one of the first scholars to attempt a prediction of global political unification. Hart came at the problem using a variety of data, but the core of his approach was to extrapolate past rates of political expansion calculated from the maximal areas controlled by “each successive record-breaking government” (Hart, 1944, p. 2) in different parts of the world. Hart recognized that technologies of locomotion would significantly affect both the ability to expand and the rate of this expansion. Most of the empires of history, he pointed out, had been terrestrially confined, and his figures indicated a maximum expansion rate of 5,200 square miles per year (13,468 km2 per year) among the land-borne empires oAsia (from 3,900 to 710 B.C.) and 2,665 square miles per year (6,902 km2 per year) for the empires of the Near East, Africa, and Europe (from 4,400 to 200 B.C.).With advances in naval technology, however, the world had seen the rise of sea-borne empires with much faster expansion rates, peaking at 46,750 square miles per year (121,082 km2 per year). Finally, Hart recognized, the success of the Wright brothers in 1903 had initiated a new era of airborne empires. In 1944, he had no reliable figures from which to calculate how this development had affected rates of political unification, but he concluded that some type of world government would be an early outcome of the Second World War.

Hart’s approach was not to try to predict when the globe would be unified but rather to compute the likelihood that it would be unified by 1950.On the basis of his calculations of imperial growth rates in the past and accelerative trends in technologies of air transportation and military armaments, he concluded that by this date, either the world would be divided between two or more nearly-equal rival groups (in which case a ThirdWorldWar would follow) or the world would be unified. If we were to accept that the United Nations represents a form of world government, then Hart’s conclusion would not be far off. Whether Hart himself would also accept it is unclear.On one hand, he predicted that, absent a ThirdWorldWar, either the globe would be in the hands of a despotic conqueror (or a union of conquerors) or it would be unified as a federation of nations—perhaps a regenerated League of

Nations or “a continuation and development of the United Nations”

(Hart, 1944, p.13). (At the time of Hart’s writing, the United Nations