Global

Class Formation and the New Global Left in World Historical Perspective*

Chris Chase-Dunn and Shoon Lio

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of

California-Riverside

To be presented at the session on “Globalization, labor and the transformation of work" organized by Jonathan Westover at the annual meetings of the Pacific Sociological Association, April 7-11, 2010. Available as IROWS Working Paper # 57 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows57/irows57.htm

Draft v. 3/5/10 9469 words

*

Thanks to Richard Niemeyer, Preeta Saxena, Matheu Kaneshiro, and James Love for

their help on a related paper.

Abstract: This paper reviews some of the literature on

globalization and class relations and examines the changing nature of class

relations and the core/periphery hierarchy over the last several centuries. We

suggest ways to study how much class relations are becoming globalized and we

begin to resolve the disconcerting problem of viewing the world as a single

global society at the same time as it is also understood as system of national

societies. This is part of an historical and contemporary study of the

emergence of global classes, including transnational political and economic

elites, but also transnational organizations of workers, peasants, indigenous

peoples, women, environmentalists and other counter-hegemonic political

movements that are contesting capitalist globalization. We examine conceptual

issues that arise in the analysis of the relationships between class, nation,

and the core/periphery hierarchy, as well as transnational relations. We

formulate an approach to the conceptualization and operationalization of global

classes and propose a research strategy that will allow us to estimate the

trajectories of global class formation and integration over the last 200

years.

The

neoliberal globalization project has reorganized global class relations in the

world-system, producing a situation in which the labor movement is taking new

forms and is making alliances with other anti-systemic movements and

progressive regimes in an emerging constellation of progressive forces that has

become known as the New Global Left. This paper recapitulates the major

contributions to understanding recent changes in the global class structure,

discusses ways to empirically untangle the complicated relationship between the

global class structure and the core/periphery hierarchy as understood in the

world-systems perspective, and considers possible roles that the emerging

transnational working class might play in the world revolution of 20xx.

Waves of economic and political integration --

increasing and then decreasing trade and investment globalization as well as a

spiraling emergence of transnational and international political organizations

– have accompanied a process in which both elites and masses have oscillated

from predominantly local and national consciousness and organization toward

increasingly transnational and global identities and interconnections. Our

research focuses on problems of operationalizing and measuring several aspects

of global class formation and the trajectory of these trends since 1800. We

also consider the extent to which increasing transnational organization of

classes may have altered (or be altering) the other cyclical processes and

secular trends of the capitalist world-system. Especially important are the

possible consequences of global class formation for hegemonic rivalry and the

probability of war among core states.

The popular discourse about globalization presumes

the recent emergence of an international realm of economic competition that has

made military competition among the most powerful states obsolete. It is often

assumed that the core countries have achieved a degree of interdependence such

that future rivalries can easily be resolved without resort to warfare.

There is also an important literature about the

emergence of a new stage of global capitalism in which large transnational

corporations and financial markets operate on an intercontinental scale and a

relatively powerful and integrated transnational group of capitalists and

managers have emerged to constitute an organized and connected global ruling

class. It is alleged that this new stage of global capitalism has importantly

transformed the logic of economic development and governance. This approach claims that national states

have lost power to international financial markets and global corporations, and

that organized labor has lost leverage over firms because of capital flight,

job blackmail and flexible specialization.

Like the popular globalization discourse, the global capitalism thesis

tends to assume that warfare among the most powerful states is a thing of the

past. This is based on the notion that

the global capitalist class is so well integrated that it will settle future

disputes without resorting to warfare. The basic claim is that a transnational

elite has recently emerged that is much more solidly integrated than in earlier

periods. Most of the evidence adduced to

support this idea is anecdotal. An important part of our task is to devise a

strategy for comparing the amount and qualitative nature of elite integration

in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

We want to conceptualize, operationalize and

measure global class formation (at the elite as well as the popular levels)

over the last two centuries in order to evaluate the claims of the “global

capitalism” school. Our study of global class formation analyses changes in the

nature and distribution of economic and political/military power among states

and firms as well as regional and global proto-state organizations (Concert of

Europe, League of Nations, U.N., World Bank, IMF, OECD, Group of 8, WTO, etc.)

since 1800. The regional, geographical, national, core/periphery and

civilizational dimensions of these structural changes need to be

considered.

Both popular and most academic

discourses on globalization presume that the emergence of a global culture or a

global social order is a relatively recent phenomenon. According to this

literature, globalization involves two processes at work. The first process

entails the extension of a particular culture to the entire globe (Featherstone

1995) Heterogeneous cultures become incorporated and integrated into a dominant

culture which eventually covers the entire world. This suggests a greater

cultural integration, homogenization and unification that cross national

boundaries. The second process points to

the emergence of a global economic order in which the core countries have

achieved a degree of interdependence such that future rivalries can be easily

resolved without resort to warfare.

Structural

Globalization vs. the Globalization Project

It

is important to distinguish between different definitions of globalization,

especially between globalization as different kinds of large-scale integration

vs. globalization as a political project.

There

have been upward sweeps of economic, political and cultural integration since

the Stone Age. Globalization as

increased density and extent of interaction networks is not new,

although it has only become global in extent since the Europeans went around

the Earth in the 16th century. Since then there have been waves of

globalization as well as upward sweeps. So structural globalization is a cycle

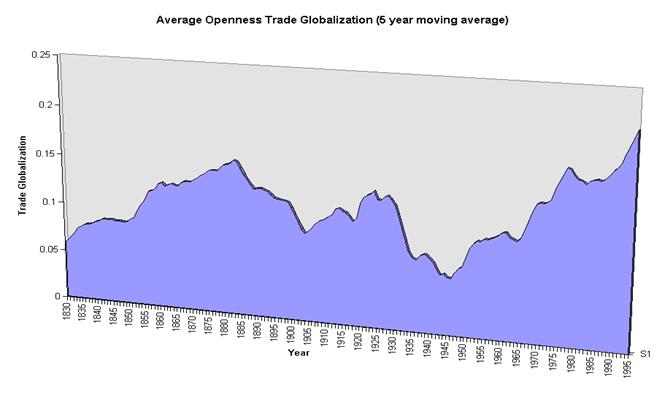

of expansion and deglobalization and also an upward trend. A quantitative study

of trade globalization, operationalized as the ratio of international imports

relative to the size of the whole world economy, produced the results shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Trade Globalization, 1830-1995

But much of what is referred to by

the word globalization is actually a set of ideological assumptions about how

the world works and political policy recommendations. Phil McMichael (2004)

calls this the ‘the globalization project.” Others have called it

“neoliberalism,” “Reaganism-

Thatcherism

“and “the

The core/periphery hierarchy and global class formation

Contemporary popular discourse about global inequalities and justice uses the

terms “Global North and Global South.” This replaced an earlier terminology

that referred to the “

In its evolution the core/periphery hierarchy has moved from a set of unequal relations among “mother countries” and their colonies, to unequal relations among formally sovereign national states, toward a set of global class relations. There has been a global class system all along, but waves of globalization and resistance have increasingly formed intraclass links so that the global hierarchy has moved in the direction of a global class system of the kind described in the works of William I. Robinson (2004, 2008). The core/periphery (c/p) hierarchy has always been a complicated nested system with core/periphery relations existing within countries as well as between them. But it has always been possible to assign national societies to the three zones of the c/p hierarchy: the core, the periphery and the semiperiphery. And this is still possible today despite the move toward a global class system. There are still significant advantages to being a worker in the core and disadvantages to being a worker in the periphery despite the move toward a global class system.

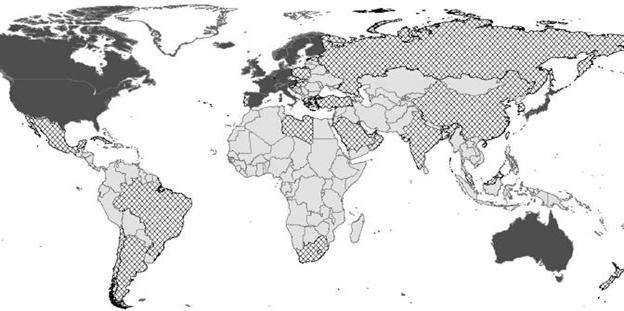

Jeffrey Kentor’s (2000, 2005) quantitative measure

of the position of national societies in the world-system remains the best

operationalization because it included GNP per capita, military capability, and

economic dominance/dependence (See Appendix). We have trichotomized Kentor’s

combined continuous indicator of world-system position into core, periphery and

semiperiphery categories for purposes of our research. The core category is

nearly equivalent to the World Bank’s “high income” classification, and is what

most people mean by the term “Global North.” We divide the “Global South” into

two categories: the semiperiphery and the periphery. The semiperiphery includes

large countries (e.g.

Figure 2: The global hierarchy of national societies: core, semiperiphery and periphery

Figure 2 depicts the global

hierarchy of national societies divided into the three world-system zones. The

core countries are in dark black, the peripheral countries are gray, and the

semiperipheral countries in the middle of the global hierarchy are in

cross-hatch. The visually obvious thing is that North America and Europe are

mostly core, Latin America is mostly semiperipheral, Africa is mostly

peripheral and

The comparative world-systems perspective developed by Chase-Dunn and Hall

(1997) suggests that semiperipheral regions have been unusually fertile sources

of innovations and have implemented social organizational forms that

transformed the scale and logic of world-systems. This is termed the hypothesis

of “semiperipheral development.” This hypothesis suggests that attention

should be paid to events and developments within the semiperiphery, both the

emergence of social movements and the emergence of national regimes. The World

Social Forum process is global in extent but its entry upon the world stage has

been primarily in semiperipheral

Theories

of Global Capitalism

We will explicate the arguments of several authors

who have developed the class structure aspects of the thesis of global

capitalism. Some of the globalization

scholars contend that globalization is a social integration process that runs

from tribal groups to nation-states, superstate blocs and a world-state society

(Featherstone 1995). The impetus for the emergence of such a global order is

alleged to be technological development (Haggard 1995;Featherstone 1995).

Technological developments such as means of transportation and the rapid

development of mass media and communication technology have enabled the binding

together of larger expanses of time-space at an inter-societal and global

level. For instance, the rapid

development of communications technology has been significant for the spatial

expansion and intensification of financial activities. Computers and

telecommunication satellites have slashed the cost of transmitting information

internationally, of confirming transactions and of paying for transactions

(Haggard 1995:xiv). The development of the technology of war has also furthered

the binding of people together in a sociation of conflict over large areas.

Globalization is conceived by Robinson and Harris

(2000) as being furthered by the expansion of economic activity in so far as

the common forms of industrial production, commodities, market behavior, trade

and consumption have become generalized around the world. Particular kinds of

economic and social institutions have arisen and proliferated throughout the

world that bind diverse people together. Robinson and Harris contend that the

nineteenth century rise of the Joint Stock Company and national corporations

led to the globalization of a particular form of economic institutions and

practices as well as the development of national capitalist classes. Capitalist

classes within the boundaries of the nation-state developed interests in

opposition to rival national capitalists in other countries. What Robinson and

Harris allege to be different between the pre-World War I integration and that

of today is that the pre-1913 integration was through “arms-length” trade in goods and services between

nationally based production systems and through cross border financial flows in

the form of portfolio capital. Robinson

and Harris (2000:19) contend that in the nineteenth century national capitalist

classes organized national production chains and mobilized domestic labor to

produced commodities within their own borders, which they then traded for

commodities produced in other countries.

Robinson and Harris also observe that national

governments have traditionally taxed goods moving in international trade and

tried to limit and constrain international capital movement. Arguably, this led

to the lengthening of the worldwide Great Depression. However, after World War

II, national governments have generally lowered their trade barriers.

Multilateral negotiations under General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT)

such as the Kennedy Round in the 1960s, the Tokyo Round in the 1970s and the

Uruguay Round of the 1990s are examples of the lowering of barriers to the

international flows of goods and capital (Haggard 1995).

Bill

Robinson (1996) contends that an integrated

global capitalist class has emerged and that the

Leslie Sklair (2001) explicitly links his

definition of the transnational capitalist class to the transnational

corporation as an institution. Saskia Sassen (1991), on the other hand, focuses

on both the organizational and market-structured aspects of the emergence of

global financial institutions within global cities such as

Scholars such as George Ritzer and Mike Featherstone

argue that there is greater functional and cultural integration in production

and consumption now than ever before. For instance, certain retailing forms of

business techniques and marketing have rapidly proliferated around the world

e.g. the global success of fast-food franchises such as McDonald’s. Ritzer

(1993) and Featherstone (1995) argue that the principles of the fast-food

restaurant are dominating more sectors of American society and the rest of the

world.

Emergence

of a Transnational Capitalist Class For Itself

According to David Kowalewski (1997), networks of

private and public elites have been constructed within national societies

across the world in the post World War II period. These networks or “establishments” have become

more transnational in their structure and processes. Increasingly the political

and economic elites of the North have established links with those of the South

into a web of mutual benefit. The emergence of a transnational or global elite

class has been facilitated by the increasing concentration of capital in the

world. Transnational elites have been

the major agents for a new global class formation. Kowalewski quotes from the

speech that Walter Wriston of Citicorp delivered to the International

Industrial Conference:

The development of the World Corporation into a truly multinational organization has produced a group of managers of many nationalities whose perception of the needs and wants of the human race know no boundaries. They really believe in One World…. They are managers who are against the partitioning of the world …on the pragmatic ground that the planet has become too small…to engage in the old nationalistic games (Cited in Kowalewski 1997:20).

Kowalewski (1997:15) contends that the

transnational capitalist class has emerged because of the secular trend of

capital concentration. The world’s

capitalist elites have merged through a number of informal and formal

connections. Informal connections are

those connections that have expressive rather than instrumental objectives.

These include ties and relationships that ease the frictions arising from more

formal connections. Examples of informal connections include family, school and

social clubs.

Formal connections are those

institutional connections that have instrumental objectives (Kowaleski 1997:

16). They include interlocking directorates, shareholdings, joint ventures,

economic associations, public enterprises, and political payments. All of these

various networks form the structure that permits the transnational elite to

“form a collective consciousness of identity, values, and solidarity. It allows them to formulate common strategies

“(Kowalewski 1997:18). Many scholars have focused on the emergence of

transnational and global institutions that furthered the concentration of

capital and facilitated the emergence of this transnational elite. Most accounts begin with World War II and

argue that class formation in the twentieth century is a new phenomenon that

needs to be explained. We will take up

this historical challenge by examining global processes in the nineteenth

century and compare them with the twentieth century.

Classes

in the World-System: The Spiral of Integration

An alternative approach is provided by the

world-systems perspective (Wallerstein 1974; Chase-Dunn 1998; Arrighi 1994). In

this view the modern world-system has been importantly integrated by

transnational relations for centuries. National development has occurred within

a larger arena of geopolitical and economic competition. The objective class

structure of the world has been structured politically as an interstate system,

a system of competing and unequally powerful states, but transnational

alliances and business activities have been central to the evolution of

organizational strategies and the expansion of the world-system for six hundred

years.

There has been a global capitalist class

for centuries in the "an sich" (objective) sense. It has gotten bigger

(fewer landed aristocracies to compete with), and it has gotten more integrated

in a series of waves separated by periods of disintegration and conflict (World

Wars). The global capitalist class is probably more integrated now than it has

ever been, but how much more? And is it integrated enough to prevent future

world wars? Also the transnational capitalist class has evolved while it has

grown. Most of its early integration was based on informal and kin-based ties

of the kind discussed below. But the trend since World War II has been toward

integration based on formal institutions. The World Economic Forum, founded in

1971, is the most important institution for integrating the global capitalist

class by bringing the leadership groups of the largest transnational

corporations together with politicians, entertainers and academicians.

The organizational structure of classes and states

has oscillated back and forth between greater transnational integration and

more “mercantile” and state-organized national structures. This cycle corresponds to waves of expansion

and intensification of international trade and investment and is affected by

the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers – the Dutch in the seventeenth

century, the British in the nineteenth century and the

Figure 3 diagrams the global class structure,

indicating that a portion of each class is transnationally linked. For the

global capitalism theorists this is a condition of recent origin, whereas for

world-systemites it has long been the case, but the size of the transnational

segments has been getting larger with each upward spiral of integration. The

big question that we would like to answer is how much larger are the transnational

segments now than they were in the nineteenth century; and are they large

enough to prevent the system from undergoing another period of world war?

Figure 3: World Classes with Transnational Segments

Nineteenth Century Globalization and

the Ideology of Liberalism

Cultural integration existed between the different

elites of the core nations and also between core and peripheral elites in the

nineteenth century. For instance, the ruling class that governed

As with the contemporary wave of global

integration, a nineteenth century liberal ideology generated the widespread

expectation that free trade would bring about the end of an era of

despotism. However, for free trade and

democratic government to spread globally, there must be greater international

economic and social integration. In the last half of the nineteenth century

international trade and finance became highly integrated and cosmopolitan. The Pax Britannica championed free

trade and strove to overcome the structure of the mercantilist era in which

states placed substantial restrictions on trade as part of the project of

nation building.

International

migration spurred global integration. Continental merchants and bankers settled

in

Partnerships and collaborations in the form of

joint ventures crossed national

boundaries.

For instance, the Discount Bank of

Intermarriage

and the Emergence of a Global Elite Culture

Intermarriage between groups is an important form

of intergroup integration in nearly all world-systems (Chase-Dunn and Hall

1997: 135). In kin-based systems kin groups create political and economic

alliances primarily by means of marriage. In modern complex systems family

structures only complement other institutional structures, but they still

remain an important aspect of the informal linkages that create trust among

both elites and masses. The institutions of informal association have long been

examined as an important aspect of national class formation (e.g. Domhoff

1998), but this kind of analysis is also important to the examination of

transnational class linkages.

Intermarriage was an important mechanism for

the formation and integration of a transnational mercantile class in the

nineteenth century. Families concerned with foreign trade usually place their

sons in the houses of their overseas correspondents to learn the trade (Jones

1987: 88). Apprenticeship not only led to the diffusion of a cosmopolitan

liberal ideology across national boundaries, it also created social contracts

that would lead to intermarriage. For

instance, the children of

In the first half of the century, European

businessmen on the African coast took

indigenous wives who were active partners in their trading ventures (Jones

1987). Many of the West African mercantile elites were the result of such

liaisons. Anglo-American intermarriages

were also becoming fashionable by the late 1880s. Between 1870 and 1914 there

were 454 rich young American women who crossed the

The most prominent of the Anglo-American marriages

was the Churchill family (Fowler 1993).

Intermarriage also created cross-national relationships that mitigated

the risks of international trade. Merchant banks preferred working with a

trusted house that would perform business for them on commission and joint

accounts (Jones 1987:99). Intermarriage facilitated the creation of integrated

international connections. For instance, the Rathbones of Liverpool relied on

Henry Gair for representation in the

Structural

Integration via Legal Incorporation and Joint Stock Companies

In the seventeenth century Dutch investors from

In

the nineteenth century wartime disruptions, the move to more capital-intensive

manufacturing, the breakdown of established systems of regulated trade, and the

diffusion of a global liberal ideology accelerated the processes of

international mercantile apprenticeship. Migration facilitated the

intermingling of merchants of different nationalities (Jones 1987).

This intermingling led to a more complete social

integration; the newcomers diversified out of international trade into

landownership in their adoptive countries. Intermarriage between the northern

elites and indigenous elites led to the formation of a cosmopolitan elite in

which ethnicity and nationality were not the primary determinants of

status. Structurally, the system still

impeded the creation of strong transnational interlocking partnerships. For instance, unlimited liability made these

interlocking partnerships too risky. Thus, there were attempts to push for

partnership with limited liability.

Major railways and banks achieved limited liability through legislative

acts in one country after another (Jones 1987:104). Easier legal incorporation of limited

liability firms permitted the rapid spread of banks, shipping companies and

other ventures (Jones 1987: 106).

This limited liability made it easier for an owner

to leave direct supervision in the hands of a local managing agent while he

lived a life as a rentier, spreading his capital in a number of

securities. Another effect of incorporation was that it reduced the risks

involved in the diversification of firms.

Firms would diversify by creating a new corporation for every

venture.

Nationalism

and Fragmentation of the Transnational Bourgeoisie

According to Jones (1987) merchants from both the

core and periphery moved into banking and land, insurance, railways, public

utilities, manufacture, distribution and mining. In the process, more

vertically integrated systems for the finance, processing and shipment of

internationally traded commodities emerged. This led to greater contact and competition

between firms. Railways facilitated the

movement of produce and commodities to markets and the people to work.

Native and expatriate international merchants

found their ambiguous nationality and comprador status more of a liability in

countries where the political tide had turned against cosmopolitan liberalism

(Jones 1987: 197). The cosmopolitan

bourgeoisie were under simultaneous threat from local populist pressures and

the competitive forces of metropolitan capital (Jones 1987:198). When Mexico’s

Minister of finance, Jose Yves Limantour ran for president in 1900, he was

attacked by his enemies for being a Frenchman because of his parentage and

because he had sacrificed the short-run domestic interests of Mexico through

conservative monetary and spending policies (Topik 200:732). Merchants tried to

deal with these twin threats by developing closer accommodation with the local

states that were willing to help those businessmen who identified with and

resided in the country.

Though we are unconvinced by many of the arguments

that portray the contemporary period as a qualitatively new form of global

capitalism based on transnational corporations, globalized financial markets or

flexible specialization, we do see at least one development that indicates that

a new dynamic may be operating. The series of global debt cycles that began in

the early nineteenth century virtually always ended in a collapse of the

financial structures and a recalibration of the relationship between the real

world of production and consumption and the symbolic world of financial claims

to future income streams (Suter 1992). The global debt crisis of the 1980s did

not eventuate in such a collapse. The debt was restructured and some was

written off, but the majority of the load of symbolic claims survived. This

non-collapse was made possible by the organizational coordination of the

We have demonstrated that there was a good deal of

transnational integration in the last half of nineteenth century and that it

declined during the contraction of international economic integration that

occurred in early twentieth century. What we have not been yet able to do is

figure out how to move toward a quantitative estimate of the degree of

transnational elite integration for the world-system as a whole. As with other

efforts to measure globalization (e.g.

Chase-Dunn, Kawano, and Brewer 2000), the estimation of a global characteristic

needs to take account of the changing size of the system as a whole. Of course

there are more transnational communications and interactions now than there

were in the nineteenth century. There are also more within-nation

communications and interactions because the world population and the world

economy have become larger. It is the ratio of these that must be studied.

Intermarriage, interlocking directorates and joint

ventures are possible empirical indicators of elite integration that might be

operationalized in order to construct the measurements that we see as vital. We

propose to compare these indicators of integration of the global capitalist

class for two time periods, the last two decades of the nineteenth century and

the last two decades of the twentieth century.

The boundaries between classes are usually fuzzy

and so an effort to study the whole global capitalist class would quickly

encounter the sticky problem of where to draw the line. We will avoid this

conundrum by focusing on only the very top segment of the global capitalist

class, and this will be defined as two entities; the richest 100 individuals on

earth as indicated by wealth and income, and the largest 100 business

enterprises as indicated by yearly gross revenues and number of employees. It

should be possible to identify these segments for the decades under study and

to study the degree of integration of these segments regarding informal and formal

ties.

The comparative study of ties needs to pay

attention not only to the overall degree of integration but also to the

structure of the integration. Our main motivation for studying elite

integration is to shed light on the probabilities and possibilities of future

wars among the great powers. Studies of earlier world wars and their

relationship with the processes of hegemonic rise and fall, or what Modelski

and Thompson (1996) call the “power cycle” of the rise and fall of “system

leaders” have noted some interesting patterns. William R. Thompson (2000) notes that declining “system leaders”

often ally with an amiable rising challenger against another challenger that is

perceived at more threatening. Thompson then looks closely at the formerly

hostile relationship between the

The question this raises for our study of integration

is “integration with whom?” A truly global integration that would prevent bloc

formation in a conflictive situation would need to crosscut the most friable

cleavages. This instructs us to pay close attention to whatever links there may

have been before World War I across the fault lines that emerged as chasms of

the Great War.

The

World Working Class

Defined objectively in terms of

control over the means of production there has been a single world proletariat

for centuries. Its fully proletarianized segment has undoubtedly grown as a

proportion of the whole world work force, but there has long been a large

semi-proletariat of part-time workers who rely on rural redoubts for at least

some of their sustenance. The classical migrant labor forces have evolved into

a more permanently urbanized group of “informal sector” workers in the

megacities of the periphery and semiperiphery.

In order to study the question of transnational class integration

analogous to our study of the global capitalist class we need to first get a

good grip on the structure of the global work force. In this we need to include

peasants who grow their own food and/or produce for the market. In order to

keep our study feasible we will adopt the same strategy of looking at the two fin-de-sciecle

decades of each century. So the first question is to compare the structure of

the world work force in these two time periods.

The second question is about

integration. And here we are interested in communications, direct interactions,

organizational ties, and participation in explicitly international and

transnational political organizations. Migration is an important aspect of

these ties.

Boswell

and Chase-Dunn (2000) have conceptualized “world revolutions” in which the

mobilization of movements of resistance to domination and exploitation has

restructured the normative and institutional structures of “world orders.” Thus

they see the abolition of legal slavery and the eventual elimination of formal

colonialism as the result of movements of resistance that eventually culminated

in structuring normative regimes that all states and actors are sanctioned for

violating. The labor movement, the socialist movement and the communist states

are all understood as efforts of resistance to capitalism that attempted to

fundamentally restructure its logic, but that instead impelled capitalists and

their statesmen to expand and reorganize the institutions of capital

accumulation. In this view the workers and peasants are not inert victims.

Rather their efforts to resist and to found less exploitative institutions have

been an important driving force in the evolution of global capitalism.

The

question at hand is about the comparison of transnational integration of the

global working class in the last two decades of the last two centuries. This

question is also germane to the problem of global conflict broached above.

Labor internationalism has long been understood as a potential force for peace.

The classical failure of the Second International on the eve of World War I is

perhaps the most poignant episode.

Samuel

Huntington (1973) long ago predicted that the growth and multiplication of

transnational corporations would eventually lead to the building of global

unions as a necessary counter-response by organized labor. Transborder

organizing and global labor agreements have indeed been implemented in the

following years (Stevis and Boswell 2008) but these efforts have continued to

suffer from the problems created by nationalism, cultural differences and

North/South differences income and interests. The global labor movement has a

long way to go in becoming a powerful force. Much progress has been made in allying

with other social movements, but there are still big problems of collective

action on a global scale. The socialist

and communist claims that the working class would be the agent of the

transformation of capitalism to a more cooperative and humane social logic has

fallen on hard times, though the theories of global capitalism and the idea of

a globalized working class may hold out hope for a revitalization of these

ideas.

The Pink Tide

The World Social Forum (WSF) is not the only political force that demonstrates the rise of the New Global Left. The WSF is embedded within a larger socio-historical context that is challenging the hegemony of global capital. It was this larger context that facilitated the founding of the WSF in 2001. The anti-IMF protests of the 1980s and the Zapatista rebellion of 1994 were early harbingers of the current world revolution that challenges the neoliberal capitalist order.

History proceeds in a series of waves. Capitalist expansions ebb and flow, and

egalitarian and humanistic counter-movements emerge in a cyclical dialectical

struggle. Polanyi(1944) called this the double-movement (Polanyi 1944), while

others have termed it a “spiral of capitalism and socialism.” This spiral of

capitalism and socialism describes the undulations of the global economy that

has alternated between expansive commodification throughout the global economy,

followed by resistance movements on behalf of workers and other oppressed

groups (Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000). The Reagan/Thatcher neoliberal capitalist

globalization project extended the power of transnational capital. This project

has reached its ideological and material limits. It has increased inequality

within and between countries, exacerbated rapid urbanization in the Global

South (so-called Planet of Slums), attacked the welfare state and institutional

protections for the poor, and led to global financial collapse. The

globalization project was crisis management because of overaccumulation in core

manufacturing and a declining profit rate in the 1970s and 1980s. Obvious

limitations of the expansion of financialization led certain neoconservative

elements of the global elite to support “imperial over-reach” an effort to use

military power to control the global oil supply as a means to prop up declining

A global countermovement has arisen to challenge neoliberalism and

neoconservatism and decades of capitalist expansion. This progressive

countermovement is composed of increasingly transnational social movements and

a growing number of populist governments in

|

Country |

Pink Tide |

Year |

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

1992 |

|

|

0 |

1996 |

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

2 |

1959 |

|

|

2 |

1998 |

|

|

1 |

1993 |

|

|

2 |

2000 |

|

|

1 |

2001 |

|

|

2 |

2002 |

|

|

2 |

2003 |

|

|

2 |

2003 |

|

|

2 |

2005 |

|

|

2 |

2006 |

|

|

2 |

2006 |

|

|

2 |

2006 |

|

|

1 |

2007 |

|

|

1 |

2007 |

|

|

2 |

2008 |

|

|

2 |

2009 |

Table 1: Pink Tide status of Latin American countries: 0= not Pink Tide; 1= Partial Pink Tide,

2= Full-Blown Pink Tide

An important difference between these and many earlier Leftist regimes in the non-core is that they have come to head up governments by means of popular elections rather than by violent revolutions. This signifies an important difference from earlier world revolutions. The spread of electoral democracy to the non-core has been part of a larger political incorporation of former colonies into the European interstate system. This evolutionary development of the global political system has mainly been caused by the industrialization of the non-core and the growing size of the urban working class in non-core countries (Silver 2003). While much of the democratization of the Global South has taken the form of “polyarchy” in which elites play musical chairs (Robinson 1996), in some countries Most of the Pink Tide Leftist regimes have been voted into power. This is a very different form of regime formation than the revolutionary road taken by most earlier Leftist regimes in the non-core.

The ideologies of the Pink Tide regimes have been both socialist and

indigenist, with different mixes in different countries. The acknowledged

leader of the Pink Tide as a distinctive brand of leftist populism is the

Bolivarian Revolution led by Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez. But various

other forms of progressive political ideologies are also heading up states in

The development of states in

Thus one sees waves between the spread of capital domination and the struggle

for popular rights throughout the history of many countries in

Figure 4: The Pink

Tide in

As one can see from Figure 4,

the rise of the left has engulfed nearly all of South America and a

considerable portion of

Wallerstein’s long run rise of wages (pp 58-59) in

his Decline of American Power, 3 major

trends that reach asymptotes (wages, taxes, ecological degradation).

Stages of w-s devel. Arrighi, systemic cycles of

accum. Iw. Millenariansism and asymtotes, continuity and change. The stages

issue. What are the important diffs from

the last sysemic cycle of accum and the last period of hegemonic downturn? See 3 futures.

Measuring global class formation: class in itself, class for itself

How to measure. How not to. Within/between diffs,

struggle to deal with north/south diffs within labor movment and other

movements. Issues. South/south diffs.

How much global class formation? Compare with 19th

century or earlier

Bergesen on globology and the global mode of

production

John Meyer, et al on world society

Leslie Sklair on transnational practices

Bill robinson on transnational capitalist class,

transnational capitalist state, and new

informalized global working class.

Struna paper on global proletarian fractions

Roberts and Struna asa paper on C/p and class

More on the core periphery hierarchy and global class

formation

Bev Silver, informalization, planet of slums, deruralization.

The global reserve army of labor. Semiproletarianization.

Evo of glob class and c/p hierarchy interact. Waves

of. Spiral of cap and soc.

Class relations in and for an sich and fur sich.

Globalized workers- attack on unions. History of

Job blackmail., regional-global

When all labor is free we will

have socialism

Coercion and free labor’ pkap.

The function of class harmony in the core.

Urbanization,

proletarianization, informal sector, casualized labor

References

Amin, Samir. 1980a. Class and Nation, Historically and

in the Current Crisis.

Review Press.

_______1980b “The class structure of

the contemporary imperialist system.” Monthly Review 31,8:9-

26.

__________ 2008. “Towards the fifth international?” Pp. 123-143 in Katarina Sehm-

Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Global Political Paties.

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth Century

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K. Hopkins and

Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic

Movements.

Arrighi,

Giovanni and Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos

and Governance in the Modern World-

System:

Comparing Hegemonic Transitions.

Minnesota Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni

2009 Adam Smith in Beijing.

Bairoch, Paul 1996

"Globalization Myths and Realities: One Century of External Trade

and Foreign

Investment",

in Robert Boyer and Daniel Drache (eds.)

, States Against Markets: The Limits of

Globalization,

Bornschier, Volker and Christopher Chase-Dunn

(eds.) 2000 The Future of Global Conflict.

Borrego, John 2000 "Twenty-fifty: the

hegemonic moment of global capitalism" in Bornschier and

Chase-Dunn.

Boswell,

Terry and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The

Spiral of Capitalism and

Socialism:

Toward Global Democracy.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher 1998 Global Formation:

Structures of the World-Economy (2nd

ed.)

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Bruce Podobnik 1995 “The Next

World War: World-System

Cycles

and Trends” Journal of World-Systems

Research 1, 6

http://csf.colorado.edu/jwsr/archive/vol1/v1_n6.htm

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 “Trade

globalization since 1795: waves of integration in

the world-system.”

American

Sociological Review, February.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Salvatore Babones (eds.) 2006 Global

Social Change.

University

Press.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Richard Niemeyer 2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” in Mathias Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational Political Spaces. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/New York Chase-Dunn, C. and Ellen Reese 2007 “The World Social Forum – A Global Party in the Making?”Pp. 53-91 in Katarina Sehm-Patamaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Global Political Parties.

Domhoff,

G. William 1998 Who Rules

View, CA.:

Mayfield.

Featherstone,

Mike. 1995. Undoing Culture:

Globalization, Postmodernism, and Identity.

Fowler,

Marian. 1993. In a Gilded Cage: From

Heiress to Duchess.

Quarterly Journal of Ideology 1,2:32-7.

Haggard,

Stephan.1995. Developing Nations and the

Politics of Global Integration.

368.

1880-1910” Journal of Historical Sociology 1: 74-101.

Jones,

Charles A. 1987. International Business

in the Nineteenth Century: The Rise and Fall of a Cosmopolitan

Bourgeoisie.

Jones,

Gareth Steadman 1971 Outcaste

Kentor,

Jeffrey 2000 Capital and Coercion: The Role of Economic and Military Power

in the World-Economy

1800-1990 .

Kentor, Jeffrey. 2005. “Changes in the Global Hierarchy, 1980-2000.” IROWS Working Paper #46

Kowalewski,

David. 1997. Global Establishment: The

Political Economy of North/Asian Networks.

Mann,

Michael 1993 The Sources of Social Power, Vol. 2: The Rise of Classes and

Nation-states, 1760-1914.

McMichael,

Phillip 2004 Development and Social

Change.

Modelski,

George and William R. Thompson 1996 Leading Sectors and World Powers: the

Coevolution of

Global Politics and World Economics.

Moghadam,

Valentine 2005 Globalizing Women: Transnational Feminist Networks.

Murphy, Craig 1994 International Organization and Industrial

Change: Global Governance since 1850. New

O’Rourke, Kevin H and Jeffrey G.

Williamson 1999 Globalization and History: The Evolution of a 19th

Century Atlantic

Economy.

Roberts, Anthony 2010 “Leading firm size

and the transnational working class”

Roberts Anthony and Jason Struna 2010 “The interface of global class

formation and core/periphery relations: toward a synthetic theory of global

inequalities”

Robinson,

William I. 1996 Promoting Polyarchy:

Globalization,

_______________

2004 A Theory of Global Capitalism.

_______________

2008

University Press

Robinson,

William I. and Jerry Harris. 2000. “Toward a Global Ruling Class?: Globalization

and the

Transnational Capitalist Class,” Science & Society

64(1): 11-54

Ross, Robert and Kent

Trachte 1990 Global Capitalism: The New

Leviathan.

Sassen, Saskia.1991. Global Cities. Princeton:

___________ 2006 Territory*Authority*Rights.

Princeton:

Shannon,

Thomas R. 1996 An Introduction to the

World-System Perspective Boulder, CO.: Westview.

Silver,

___________ 2002

2003 Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization Since 1870.

Silver, Beverly and E. Slater (1999). The Social Origins

of World Hegemonies. In G. Arrighi, et al.

Chaos

and Governance in the Modern World System.

Sklair,

Leslie. 2001. The Transnational

Capitalist Class.

Publishers.

Sklar,

Holly (ed.) 1980 Trilateralism: the Trilateral Commission and Elite Planning

for World

Management.

Smith, Jackie, Marina Karides, et al. 2007 The World Social Forum and the Challenges of Global Democracy.

Stevis, Dmitris and Terry Boswell 2008 Globalization and labor:

democratizing global

governance.

Struna,

Jason 2009 “Toward a theory of global proletarian fractions”

Suter,

Christian 1992 Debt Cycles in the World Economy: Foreign Loans, Financial

Crises and Debt

Settlements, 1820-1987.

Thompson,

William R. 2000 The Emergence of the Global Political Economy.

Routledge.

Topik,

Steven C. 2000. “When

Bankers, and Nationalists, 1862-1910.” American Historical Review:714-738.

Van

der Pijl, Kees. 1984. The Making of an

accumulation’: the example of the MAI, the

Multilateral Agreement on Investment.”

Journal of World-Systems Research 6,3:728-747 Fall/Winter.

Wallerstein, Immanuel 1974 The Modern

World-System: Volume 1.

____________ 1979 The Modern World-System:

Volume II.

_____. 1989. The Modern World-System III: The Second Era of Great Expansion of the

Capitalist World-

Economy,

1730-1840s.

_____________ 2001

_________________ Forthcoming The Modern World-System, IV:

Waterman, Peter 2006 “Toward a Global Labor

Charter Movement?” http://wsfworkshop.openspaceforum.net/twiki/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=6