Introduction

In this paper I review some of the understandings of frontiers and borders in a deep global and historical perspective to shine some light on contemporary issues. In particular I seek to sort out what is really new in the 21st century, what is typical of the modern era – modern as in the modern world-system – and what is a continuation of older processes that may stem back as far as the invention of the state at Ur some five millennia ago. I must caution, however, that this account is colored by the larger project of which it is a part. That project is a broad comparative study of frontiers, driven by variance maximizing strategy to begin to define the “universe” of frontiers (for elaboration of this theme see Hall 2009). This project is a first step in trying to extract salient characteristics of frontiers that might be useful in a boolean analysis (Ragin 1987) of frontiers, akin to John Foran’s (2005) of third world revolutions.

Thus, the

comparisons of the American Southwest, a frontier at least with respect to

European states since 1542 or so – and much older if one looks at inter-polity

frontiers among indigenous populations since well before European intrusion. The

Indeed, the

two areas New Spain/Southwest United States and what might be called greater

On the

other hand

In comparing these two regions I underscore my own argument (Hall 1989, 1998) and Yang’s argument (2009) that any frontier, especially these two can only be understood in the contexts of their larger, global interactions, but equally so analysis requires careful attention to specific, local contexts and interactions. Indeed, a first general lesson from this – and potentially many other – comparisons is that to neglect either the local or the global hinders comprehension of complex social interactions.

I begin with brief accounts of each region, then turn to a listing of similarities and differences, then focus on comparisons among pre-modern, proto-modern, and modern frontiers. I use these comparisons then to extract some border lessons and questions about contemporary frontiers and borders.

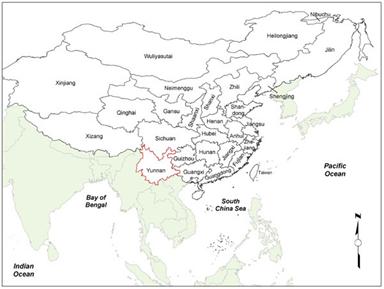

Yang 2009, Map 6.1, ca.

p. 208:

Southwest China, essentially what eventually became

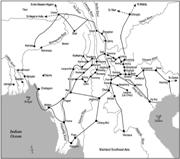

Yang, 2009, Chap 2, Maps 2.1, 2.2, 2.3: Southwest Silk Road in the Qin-Han Period (221bce-220ce), in the Nanzhao-Dali Period (8th cent – 13th cent), and in in the Yuan-Ming-Qing Period (1271 – 1912)

The

Prior to

the thirteenth century various local kingdoms were able to use geographic,

climatic, and geopolitical conditions to maintain a degree of autonomy from

other states, especially

As long as

those goals were met, local rule prevailed. The succeeding Ming Dynasty sought

stronger conquest of the region in order to avoid a dependency like that of the

Southern Song had experienced with

Ironically,

Up to this

time rule was primarily indirect through local, native or indigenous, leaders.

Yang argues that “Sinicization and indigenization were two sides of the process

through which a middle ground was negotiated” (2009, p. 102). Chinese had long ruled

frontier peoples based on native customs, but with the intentions of

“civilizing” (sinicizing) them eventually. This took approximately five

centuries in

The parallel strategies of direct and indirect administrative systems continued through the Mongol Yuan period and extended into the Ming Dynasty. Centralized, province-wide administration was built on governors who were appointed to rule sub-regions. In rural areas that had a preponderance of indigenous populations native chiefs were placed under the rule of these officials. While local leaders were required to pay tribute and meet other obligations, this did not eliminate continuing interactions including payments to other states in Southeast Asia.Slowly the Ming and Qing Dynasties adopted the gaitu guiliu policy that sought to transform native chief into a part of the imperial administration. Gradually, the domination of ethnicity over administration in the native chief areas changed to a system in which ethnicity became a subdivision of administration. This was facilitated many imperial regulations and practices such as regulating the inheritance of chieftainship and taking sons of chief to Chinese schools (central or local) to train them in Chinese language and administrative processes. Upon their return they became agents of sinicization.

This

process, however was not one-sided. Yang argues that sinicization and

indigenization were sides of the same coin. They contributed to the emergence

of Yunnanese as provincial identity and in turn became an avenue for the

absorption of some Yunnanese practices into Chinese identity and culture. By

the end of the Ming Dynasty immigration, settlement of soldiers, and movement

of traders, Han people became the largest ethnic population in

The

presence of large mining communities led to types of urbanization different

from those in the

Gradually

the economy became redirected to

In the Qing

Dynasty immigration to

Copper

mining was the primary force toward industrialization. Reduction of Japanese

copper supply heightened interest in Yunnanese copper. While Chinese

administrations generally discouraged concentration of miners as potential

sources of unrest, they were necessary in

Clearly,

“The Greater Southwest”: A Brief History [3]

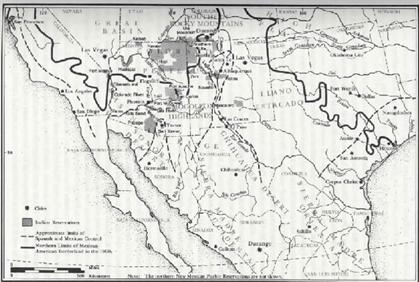

Defining the “Greater Southwest,” like defining

The Southwest is a distinctive place to the American mind but a somewhat blurred place on American maps, which is to say that everyone knows that there is a Southwest but there is little agreement as to just where it is... . The term "Southwest" is of course an ethnocentric one: what is south and west to the Anglo-American was long the north of the Hispanic-American... .

Reed (1964:175) facetiously defined the Southwest as

reaching from Durango to Durango (

Hall 1989, Map III.1, pg. 35: The Southwest: A Context for Definition

For

approximately the first three centuries of European domination, the American

Southwest was the northwestern frontier of

Spaniards

entered the area in the 1530s and colonized

Continual lack of state support pushed the military to supplement its pay with booty taken during conflicts. Indeed, occasionally obtaining spoils of conflict were a major motivator of it. The main resources available from nomadic groups were captives to be used as domestic servants or sold to the miners in the south. Horses, and to a lesser extent guns, gradually spread to indigenous peoples, despite Spanish efforts to monopolize both. Again, acquiring horses and guns were a major motivator of indigenous raids. Nomads who wanted horses or guns to defend themselves against raids by rivals had little to trade but captives taken from their own enemies. Raids by on indigenous group on another prompted vengeance by kinsmen, which quickly led to a state of endemic warfare.[7] The continuous trade in captives, the shortage of military resources, and Spanish civil-ecclesiastic bickering reinforced engendered endemic warfare among indigenous groups, and between them and Spanish settlers. Oppression, both economic and religious, of Pueblos during the seventeenth century led to a rebellion (Pueblo Revolt) in 1680 which drove the Spaniards from New Mexico for thirteen years.

Worry about

European rivals and Church worry over the few Christianized Indians left behind

prompted reconquest and recolonization of

The

Viceroys of New Spain needed to pacify the frontier, but had limited resources

to do so. Endemic warfare was a major obstacle and source of expense. Even after

the late eighteenth century reorganization of the frontier provinces (Bourbon

Reforms)

Governors

tried to settle nomadic groups into compact farming communities in imitation of

Spanish villages. This process had worked in central

Few nomads were sedentarized effectively, but they did become somewhat more centrally organized, that is they developed somewhat more institutionalized forms of leadership. This pressure was strongest on Comanche bands (Kavanaugh 1996; Hämäläinen 2008), while an opposing divide and conquer strategy promoted fragmentation of Apache bands.

Comanches, who occupied territory at and beyond the edge of the northern frontier, were able to trade with Plains groups and some Europeans to obtain guns. There are some reports, disputed by some scholars, that Comanches brought French flintlocks to the Pecos (NM) trade fairs. Settlers eagerly sought such guns to circumvent the official restriction of firearms to the military. Comanches obtained horses in return and also from Apaches and other groups. Comanches quickly became very successful mounted hunters and warriors by capitalizing on their middle position in the horse and gun trade. They developed extensive trade networks of their own and came to dominate the region north and west of the New Mexican frontier (Hämäläinen 1993, 2003, 2008).

New Mexican

governor de Anza (1778-1787) repeatedly defeated Comanche bands and banned

trade with them, while

Without the

treaty

Initially Apache groups gained advantage over other groups by early possession of horses. In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries they had developed semi-permanent villages on the Plains allowing organization of large war parties. However, they had poor access to guns, because Spanish policy attempted to restrict guns to the Spanish army. Later Apaches gave up this village living and gradually were displaced from the Plains by Comanches who had better access to guns. Large horse herds became necessary for fighting, and pushed toward a more nomadic life.

As Apaches

were forced southwest from the Plains their raids made trade and communications

between the far north and the interior provinces of

Thus, Apache social ecology differed significantly from that of Comanches. Apaches competed directly with Spanish settlers for resources. Their trade was local and typically played one Spanish community against others. Settled Apaches and settlers resented the cost of help given to those recently pacified.

In late eighteenth

century peace became precarious, but differently for Apaches and Comanches.

Apache population decreased during war and increased during peace. Apaches

hindered Spanish development. Comanches thrived under the subsequent alliance

with the

Slowly the frontier became more tightly incorporated into the Spanish Empire, and became more fully peripheralized. The change was moderate because frontier policy needed to balance competing goals. Still there was some development.

When

rebellions in

With

independence trade along the Santa Fe Trail from

The

American conquest (1846-1848) transferred much of northwest

There were

four major differences under American control. First, all territory became part

of the national state. Second, the

Large

numbers of Europeans, most for the

After annexation

by the

Comanches

blocked westward expansion into

The

Apaches lived in a large number of small bands scattered over a diverse territory making their final subjugation comples. That history is difficult to summarize. Unlike Comanches, Apache had long been a barrier to trade, and had developed a very effective raiding mode of production. They did not depend on any one food source and could change targets frequently.

Because of competition

with new settlers military pressure grew.

After the Civil War nomadic groups were forced on to reservations eliminating or severely modifying traditional lifestyles. Nomadism, barter, raiding, and sale of captives could not coexist with more intensive uses of natural resources. Farming, ranching, and mining were seen to use the land “more efficiently” than foraging or gardening. The American state did not tolerate such "inefficient" use of resources – a thinly disguised rationale for seizing Indian territories. Native Americans had two choices: join the lower class of a capitalist state, or die resisting. Many chose the second option. Only where Americans had no desire for the land did native groups get reservations where they became "captive nations" and welfare recipients.

Again, pacification

had different effects on Comanches and Apaches. First, they had different

degrees of ecological and political flexibility. Comanches depended heavily on

the buffalo. Intentional destruction of the buffalo herds destroyed their base

of adaptation. Apaches had more diverse survival strategies. For Comanches the

slight increase in centralization and intense dependence on the buffalo made them

more vulnerable to rapid defeat. Apaches could disperse and avoid annihilation.

Over centuries they had become adept at forming new alliances, using multiple

survival strategies, and adapting to rapidly changing circumstances. Second was

geopolitical location. Comanches blocked expansion and communication across

western

In the late nineteenth centure the Dawes Act, also knows as the General Allotment Act [1887] “freed surplus” Indian land by forcing Indians on reservations to take up farming, often with allotments that were far too small for the sparsely watered west. Also during the time the government under direction of Louis Henry Pratt sought to “kill the Indian, but save the man” with required education in boarding schools that sought to eliminate indigenous languages and cultures. While originally intended as a liberal, humane reform as opposed to outright genocide, this policy was disastrous. One of it major, unintended side effects was to facilitate organization of nationwide Native American associations (Adams 1995; Wilkins 2006).

Incorporation

processes were episodic and sporadic, but tended to become stronger. The

introduction of horses and guns in the Spanish era made pre-contact practices

impossible. The contemporary groupings of indigenous peoples in the Southwest

were constructed during this era. The

This example suggests that incorporation into any world-system is problematic: (a) according to the type of system doing the incorporating; (b) with respect to social organization of incorporated groups; (c) with respect to the conditions of the incorporating system; and (d) with respect to a variety of local factors. The degree to which an area or group is incorporated into a world-system defines the context within which local changes may occur. Local actions are major factors in the costs of incorporation. Incorporation is a matter of degree and is not fully elastic. Sometimes changes engendered by incorporation they are difficult or even impossible to reverse, as with the consequences of the spread of horses.

This account shows that incorporation begins with early contact. Second, incorporated groups, even nonstate societies, play an active role in the process.[10] Third, incorporation is a variable and sporadic. Finally, more than economic reasons prompt attempts at incorporation.

I will now turn to comparison of the two southwests, then to some more general conclusions about the twenty-first century.

The Two Southwests:

Comparisons and Contrasts

Some key similarities between the two regions are that both

supplied valuable goods, and avenues of trade to other areas for other goods. Both

have highly variegated topography. Both have a high density of indigenous,

non-state peoples. Both were avenues for the penetration of new ideologies in

the form of religions: Buddhism in Asia, Christianity in the

There are some other similarities that seem to be quite common in frontier areas.

Traders intermarried with local women to gain better access

to local networks. This was also officially promoted for soldiers in

For both it

was quite late in the incorporation process that local population was surpassed

by immigrants from the incorporating state. Doubly so in the American

Southwest: for Spanish populations versus indigenous populations, and under the

There are

also key differences. Most obvious is the much greater time depth of the

Finally the

indigenous populations were quite different. In the U.S. Southwest the most

complex societies were the

These comparisons make clear that the concepts of nation-state and precise borders are quintessentially modern. Setting precise borders is a continuing project even while borderlands remain, like the frontiers that preceded them, frontier zones.

Even though separated by over a millennium, there were similar processes, though the particulars varied immensely. According to Yang:

The power struggles among Han

China, the

Under

Yang also points out an important difference on the effects of the frontier regions on the central or core states:

Yunnan silver in the Ming period,

copper cash replacing cowry currency during the Ming-Qing transition, and

Yunnan copper in the Qing period, collectively demonstrated the central

penetration over the frontier on the one hand and the significance of a

frontier in the Chinese world-economy on the other hand. Thus,

This is an important contrast, albeit slightly overstated.

There were effects of the Southwest on the now capitalist world-system, albeit

considerable lower and indirect. By annexing the land from

However it

remains a somewhat open question whether the roots of these differences lies in

the differences between ancient and modern frontiers, or in the relative power

of the state with respect to the frontier, or in a combination, or in something

else. It is not clear whether the gap in power between

Bin Yang

draws the following comparisons between the

Another

difference is the role of disease, especially tropical and sub-tropical

diseases on contact, conquest, and colonization. In the Southwest, as

throughout the

All three

incorporating states –

A clear

difference is that indirect rule was used for a much longer time, and used more

complex relations than in northwest

Finally,

Yang (2009, pp. 205-6) asks “But was

What then might we learn from all this for twentieth century border issues?

Lessons for Borders

& Frontiers

So how should be make comparative studies of frontiers?[12]

Clearly, variations can be spatial, temporal, physiographic, or organizational,

different kinds of native peoples, and different sorts of settlers. These are

all factors that must be considered in comparisons. Also important are type of

cycle, phase of cycle, type of boundary, and state of the world-system(s) that

are shaping frontiers and that frontiers are influencing. It would also seem

reasonable to consider whether the frontier was on the edge of a world-system,

whether it be at the bulk goods, political-military, luxury goods or

informational edge or along some internal boundary. Internal boundaries could

be between states or groups in similar positions within the world-system (e.g.,

core, periphery, or semiperiphery) or they could be between these different

zones. A reasonable working hypothesis would be that these two broad categories

of frontiers would exhibit different dynamics. Blackhawk’s (2006) study of the

very fringes of the Southwest frontier focuses on the very edge of the system,

whereas Reséndez’s (2005) study is concerned with the processes of identity

change within the system (when what is now southwestern

A subsidiary hypothesis might be that frontiers between different positions in a world-system might also differ. Here it is useful to recall Chase-Dunn and Hall’s (1997) argument that how many layers, and how differentiated they are in a world-system is an empirical as well as a theoretical problem.

Many case

studies of frontiers can be [re]interpreted as “incorporated comparisons”

(McMichael 1990) which are often a series of comparisons within an historical

trajectory of a case. In Colony and

Empire William Robbins (1994) examines the American West and argues that

far from being an open or free frontier, it was highly constrained by the

demands of assorted capitalist enterprises. This, of course, makes sense within

a world-systems framework. But it also sheds a different light on the common

claim that in

Blackhawk

(2006) shows that violence served to ‘ethnically cleanse’ the

In analogous ways comparisons of modern and ancient frontiers show that genocide, ethnocide, culturicide, ethnogenesis, amalgamation, hybridization, and fractionation are common processes on many different frontiers. What remains to be studied systematically is how various local, regional, state-level, and world-system conditions and dynamics shape these processes. Again, states seem to be as important as mode of accumulation and local relations of production in shaping ethnic change.

Finally, the study of frontiers illustrates how much can be learned by the study of peripheral regions and peoples and their roles in system change. Indeed, some of these processes may be visible only in peripheral and/or frontier areas. This then becomes a method to explore how it is that actions and changes in peripheral areas (and semiperipheral areas) play important roles in world-system evolution. A key point here is that many if not most of these questions can only be asked from a world-system perspective, even if they must be answered in large part locally.

Given that humans now are facing an impending crisis, and most likely a bifurcation point (Wallerstein 2010, 2011a,b), further spurred by political and economic collapse. It is useful to examine past instances of similar major changes. Since, by their nature, the processes and results of such a bifurcation are not predictable, charting a predictable result is not possible. But we may be able to perceive the outlines of a “possibility space” of results which can suggest indicators of patterns and as cautionary tales. Two other sets of recent developments play into this.

First is

Sing Chew’s work on “dark ages” (2001, 2008, 2009). Dark ages may be

intermediate between a complete bifurcation and what we might call “routine

change,” or what until now have been more or less routine cycles in

world-system processes. In his third volume (2009) Chew sketches some

insightful comparisons among the onsets of dark ages. While by no means

certain, climate change, decline of oil, rise in spills, and as the 2011

Add to this Glen Kuecker’s (2007) analysis of a “perfect storm” of political, economic, demographic, and ecological changes leading to global collapse. Much like Joseph Tainter’s (1988) analyses of past collapses, and even “dark ages,” it is very unlikely that core states will be able to continue to function and that they will be hurt the most severely. Kuecker builds on this (Kuecker and Hall 2011) drawing on Chase-Dunn’s analyses of semiperipheral marcher states (1988; Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997, ch. 5; and Chase-Dunn et al. 2006, 2010; Hall et al. 2009 ) to argue that peoples living in semiperipheral and even especially peripheral areas will have the highest likelihood of survival. This is both because they are often less embedded in the current system, and have often been able to been able to maintain lifeways that are significantly different from the variety of lifeways found in core areas. Chief among these are indigenous peoples, who have preserved lifeways that are the most different, and often most challenging to the current world-system (Hall and Fenelon 2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2008, 2009). Indeed Wallerstein says:

The so-called forgotten peoples (women, ethnic/racial/religious “minorities,” “indigenous” nations, persons of non-heterosexual sexual orientations), as well as those concerned with ecological or peace issues asserted their right to be considered prime actors on an equal level with the historical subjects of the traditional antisystemic movements (2011, p. 34, emphasis added).

It is important to underscore that they are not predictors, nor saviors. Rather, they maintain lifeways that may be suggestive of alternatives to the current system. They cannot be copied directly. Rather, how and why they have been able to preserve lifeways that do not meld with the current, neoliberal, modern world-system can be studied for clues to developing new ways of living and developing a new world-system.

This, then brings us, back (at last!) to the issues of borders and frontiers. These survivors are, and have been for millennia, most common in frontier regions of states and especially of world-systems. That is where the evidence is. For sure we can learn from studies of the rapid changes – and the more common static quality of repeated processes – of contemporary borders. Indeed, following the argument above these are the areas where survival and development of a new world-system are most likely. But we must be cautious to not get bogged down in studying elements that are simply repeated, albeit with their own special features, of older cycles. Here again, comparison with past frontiers can be very useful. As already argued, such comparison can help us identify what is actually new and what are only permutations of old processes.

In the

comparison sketched here between the U.S. Southwest and Southwest China (

One also thinks of Warren Wagar’s oft discussed (1996) Short History of the Future (1999), wherein he suggests possible forms of organization that transcend the state. Some of these processes can be studied through examination of contemporary borders. Still, there are myriad other possibilities as yet unexplored. The possibilities of such discoveries and understandings are a fundamental value of continued examinations of border processes.

Acknowlegements

I thank Bin Yang for sharing many papers with me, and saving

me from at least some egregious mistakes about the history of

References

Adams, David W.

1995. Education for Extinction: American

Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928.

Blackhawk, Ned. 2006. Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires

in the Early American West.

Brooks, James F. 2002. Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and

Community in the Southwest Borderlands. Chapel Hill:

Carter, William B. 2009. Indian Alliances and the Spanish in the

Southwest, 750-1750.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 1988. "Comparing World Systems: Toward a Theory of Semiperipheral Development." Comparative Civilizations Review 19(Fall):29-66.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Thomas D. Hall. 1997. Rise

and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis Alvarez and Thomas D. Hall. 2006.

Growth/Decline Phases and Semiperipheral Development in the Ancient

Mesopotamian and Egyptian World-Systems. Pp. 114-138 in Globalization and Global History edited by Barry K. Gills and

William R. Thompson.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Thomas D. Hall, Richard Niemeyer, Alexis Alvarez, Hiroko Inoue, Kirk Lawrence,

and Anders Carlson. 2010. “Middlemen and Marcher

States in Central

Asia and East/West Empire Synchrony.” Social Evolution and History 9:1(March):52-79.

Chew, Sing C. 2001. World Ecological Degradation: Accumulation,

Urbanization, and Deforestation 3000 B.C. - A. D. 2000.

Chew, Sing C. 2007. The Recurring Dark Ages: Ecological Stress,

Climate Changes, and System Transformation.

Chew, Sing. C. 2008. Ecological Futures: What History Can Teach

Us.

Crossley, Pamela Kyle, Helen P. Siu,

& Donald S. Sutton, eds. 2006. Empire

at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern

Crown, Patricia

L. and W. Jeffery

American Southwest." Proceedings of

the National

______. 1992.

"The Violent Edge of Empire. Pp. 1-30 in R. B. Ferguson and N. L.

Whitehead, eds. War in the Tribal Zone.

Foran, John. 2005. Taking

Power: On the Origins of

Giersch, Charles

Patterson. 2001. "A Motley Throng: Social Changes on

Guy, Donna J. and

Thomas E. Sheridan, eds. 1998. Contested

Ground: Comparative Frontiers on the Northern and Southern Edges of the Spanish

Empire.

______. 1998b.

"On Frontiers: The Northern and Southern Edges of the Spanish Empire in

Hall, Thomas D. 1989.

Social Change in the Southwest, 1350-1880.

_____. 1998. "The

_____. 2009. “Puzzles in the Comparative Study of Frontiers: Problems, Some Solutions, and Methodological Implications.” Journal of World-Systems Research 15:1:25-47.

_____. Review of Between Winds and

Clouds: The Making of

Hall, Thomas D. and James V. Fenelon. 2004. “The Futures of Indigenous Peoples: 9-11 and the Trajectory of Indigenous Survival and Resistance.” Journal of World-Systems Research,10:1(Winter):153-197.

_____. 2005a. “Indigenous Peoples and Hegemonic Change: Threats to Sovereignty

or Opportunities for Resistance?” Pp. 205-225 in Hegemonic Decline: Present and Past, edited by Jonathan Friedman

and Christopher Chase-Dunn.

_____. 2005b. “Trajectories

of Indigenous Resistance Before and After 9/11.” Pp. 95 – 110 in Transforming

Globalization: Challenges and Opportunities in the Post 9/11 Era, edited by

Bruce Podobnik and Thomas Reifer.

Hall, Thomas D. and James V. Fenelon. 2008. “Indigenous Movements and Globalization: What is Different? What is the Same?” Globalizations 5:1(March):1-11.

Hall, Thomas D. and James

V. Fenelon. 2009. Indigenous Peoples and Globalization: Resistance and

Revitalization.

Boulder , CO

Hall, Thomas D., Christopher Chase-Dunn and Richard Niemeyer. 2009. “The

Roles of Central Asian Middlemen and

Hall, Thomas D., P. Nick Kardulias, and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2011. “World-Systems Analysis and Archaeology: Continuing the Dialogue.” Journal of Archaeological Research 19:3(Sept.): forthcoming in print. [http://www.springerlink.com/content/104889/?Content+Status=Accepted].

Hämäläinen, Pekka. 1998. "The

_____. 2003. “The Rise and Fall of Plains Indians Horse Cultures.” Journal of American History 90:3(Dec.):833-862.

_____. 2008. The

Comanche Empire.

Kardulias, P.

Nick. 2007. “Negotiation and Incorporation on the Margins of World-Systems:

Examples from

Kavanaugh, Thomas

K. 1996. Comanche Political History: An

Ethnohistorical Perspective 1706-1875.

Kessell, John. 2002.

_____. 2008.

Kuecker, Glen D. 2007. “The Perfect Storm: Catastrophic

Collapse in the 21st Century.” The

International Journal Of Environmental, Cultural, Economic And Social

Sustainability 3:5: 1-10.

Kuecker, Glen D. and Thomas D. Hall. 2011. “Facing Catastrophic Systemic Collapse: Ideas from Recent Discussions of Resilience, Community, and World-Systems Analysis.” Nature and Culture 6:1(Spring):18–40.

Liu, Xinru. 2011. “A Silk Road Legacy: The Spread of Buddhism and Islam.” Journal of World History 22:1(March):55-81.

Liu, Xinru and

Lynda Norene Shaffer. 2007. Connections

across

Mann, Charles C. 2005. 1491: New Revelations of the

Manning, Patrick,

ed. 2005. World History: Global and Local

Interactions.

McMichael, Philip. 1990. "Incorporating Comparison within a World-Historical Perspective: An Alternative Comparative Method." American Sociological Review 5:3(June):385-397.

Meinig, Donald W.

1971. Southwest: Three Peoples in

Geographical Change, 1600-1970.

Ragin, Charles.

1987. The Comparative Method: Moving

Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies.

Reed, Erik K.

1964. "The Greater Southwest." Pp. 175-191 in Jesse D. Jennings and

E. Nordbeck (eds.), Prehistoric Man in

the

Reséndez, Andrés. 2005. Changing National Identities at the Frontier:

Richardson,

Rupert Norval and Carl Coke Rister. 1934. The

greater Southwest:The Economic, Social, and Cultural Development of Kansas,

Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, and California

from the Spanish Conquest to the Twentieth Century.

Robbins, William

G. 1994. Colony and Empire: The

Capitalist Transformation of the American West.

Snyder,

Stoddard, Ellwyn

R., Richard L. Nostrand, and Jonathan P. West. 1983. Borderlands Sourcebook: A Guide to the Literature on

Wagar, W.

Wagar, W.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2010. “Structural Crises.” New Left Review 62 (March/April):133-142.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2011a. “Structural Crisis in the World-System: Where Do We Go from Here? Monthly Review 62:10(March):31-39.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2011b. “The Current Conjuncture: Short-run and Middle-run Projections.” MRZine [on line: http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2009/wallerstein151209.html].

Weber, David J.

1982. The Mexican Frontier, 1821-1846.

_____. 1992. The Spanish Frontier in

White, Richard.

1991. The Middle Ground.

Wilkins, David E. 2006. American Indian Politics and the American Political System,

2nd ed.

Yang, Bin. 2004. “Horses, Silver, and Cowries:

Journal of World History

15:3(Sept.):281-322.

Yang, Bin. 2009. Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of

Yang, Bin. 2010. “The Zhang on Chinese Southern Frontiers: Disease Constructions, Environmental Changes, and Imperial Colonization.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 84:2(Summer):163-192.

Yang, Bin. 2011. “The Rise and Fall of Cowrie Shells: The Asian Story.”Journal of World History 22:1(March):1-25.