Global Public Social Science[1]

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Department

of Sociology and Institute for Research on World-Systems (IROWS)

University

of California-Riverside

(v.

9-19-11)

6278

words

C. Wright Mills

Abstract: Burawoy’s classification of the complementary aspects of the discipline of sociology is used to describe an emergent global public social science that will assist transnational social movements in the building of a democratic and collectively rational global commonwealth.

A revised version was published as C. Chase-Dunn 2005 “Global public

social science” The American Sociologist

36,3-4:121-132 (Fall/Winter). Reprinted

Pp. 179-194 in

IROWS Working Paper # 73 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows73/irows73.htm

Michael Burawoy’s 2004 ASA presidential address (Burawoy

2005) has raised anew the significant issues about what sociology is and is

not, the connections between scholarship and activism, and the responsibilities

that sociologists have to larger publics, and to human society. These are the

big questions and have been since the emergence of modern social science. The tension

between humanism and science is not external to social science. It is internal

to it. And Burawoy’s most important thesis is that this is a productive and

generative contradiction that should be used to produce both better science and

a better society. I will employ the

distinctions that Burawoy has elaborated in his presidential address between

professional, critical, policy and public sociology to discuss the issues he

raises and to describe the emergence of global public social science.

I mainly agree with Burawoy’s analysis and strongly

support his effort to renew the dialogue within sociology about the symbiotic

relationship between science and activism.

The value of his approach is starkly demonstrated by those social

science disciplines (especially Anthropology) that have largely failed in the

effort to live under a big umbrella that includes professional, public,

critical and policy social science. The internecine battles between the

politically correct activists and the stalwart defenders of scientific purity

have left all the parties weaker and the interests of all the contenders have

been profoundly undermined by the combat.

This is not a path that any sane person would choose to follow. The

anger and mistrust that are often generated in conflicts of this kind live for

years in the psyches of the combatants. They erupt again and again, reinjuring

old warriors and harming younger generations of scholars and students. The big tent of activists, scientists,

scholars and scholar-activists is a good shelter and good social science has

been, and will be, crafted within it.

Public Sociology Is More Than

Sociologist-As-Citizen

Most

of the students that come into social science are motivated by a humanistic

desire to improve upon society, often by helping the most exploited and

oppressed peoples. They believe that social science will be an avenue for

designing policies, programs, and activities that will change society in a

progressive direction. These motivations

are an important basis of the ability of our social science disciplines to

recruit hard-working and smart young people. Social science is not a road to

wealth or power. So humanistic motivations are an important part of our

cultural capital and a substantial basis of our ability to recruit those who

will become the next generation of scholars.

One very valuable aspect of Burawoy’s approach is the

acknowledgement that

”professional sociology” is the necessary center and source of strength for

public, critical and policy sociology.

My own scholarly work is quite interdisciplinary (combining ecology,

geography, history, political science, anthropology and sociology), but I

nevertheless acknowledge the importance of core disciplinary values and

procedures in sociology. I agree with Burawoy that professional sociology is

central to the constitution of the discipline of sociology, and that public

sociology, and the other forms, derive immense cultural, political and

scientific value from their connection with, and interactions with, professional

sociology.

This

is the main reason why Burawoy’s insistence that public sociology is something

distinct from the sociologist in the citizen role is valuable and useful. The

“sociologist-as-citizen” makes claims to expertise that may, or may not, be

acknowledged by larger publics. But public sociology is a stance within

sociology, and it is evaluated by both external publics and by other

sociologists because it is a legitimate form of sociological practice that

should be recognized and encouraged by all sociologists because we have a duty

to serve the human societies that fund our science. This means that the

sociological methods and theories employed in public sociology need to meet the

standards of the discipline and that all sociologist bear some responsibility

to evaluate the work that is carried on in the name of the discipline. There

are no insuperable and conflictive contradictions between professional

scientific sociology and engaged public sociology, though they are not the same

thing. The big tent requires that we acknowledge and respect both the

scientific and the humanistic roots of our discipline.

Emergent World Society and Public Social Science

I do not agree entirely with Burawoy’s characterization

of the historical development of social science in the last few decades. His

characterization of the rise of radical sociology in the 1960s is mainly used

to make the point that mainstream sociology was rather conservative then, and

that most sociologists have become (or remained) fairly liberal while much of

the rest of American society has moved to the right. I do not disagree with

this, but Burawoy’s depiction of the

struggles and outcomes that occurred in the 1960s misses an important

development: the discovery that the

Burawoy’s

narrative of sociological practice does not really even acknowledge the other

path that emerged strongly in the sixties and seventies: Third Worldism and the

world-systems perspective. The Third Worldists argued that strong challenges to

capitalism are not likely to come from the core because the most exploited

peoples are in the periphery. Some of them also discovered that the “developed

and less developed” national societies are tightly linked into a global

stratification structure – the core/periphery hierarchy. These issues are

directly relevant for both professional and public sociology. One of the

mainstays of professional sociology is the study of socially constructed

inequalities. If there is really an institutionalized core/periphery hierarchy

(rather than a set of disconnected “advanced” and “underdeveloped” national

societies) then the most unequal contemporary socially structured inequalities

are global in scope. A sociology that focuses exclusively on inequality within

countries is ignoring the most important part of the phenomenon about which it

claims expertise.

With

regard to public sociology, it is not enough to simply be of service to

existing popular movements or groups or to address larger publics. The first

job is to analyze which groups are worth serving and which ones are likely to

have an important impact in the struggle to make human societies more humane

and more equal. This analysis requires an understanding of the processes of

modern social change and the probable directions that historical development is

likely to take.

I

am a proponent and producer of what has become known as the comparative

world-systems perspective. The basic idea is that social change occurs in

systems of societies rather than in single isolated societies, and that this

has been true since the Paleolithic, though earlier world-systems were small

regional affairs (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997).

From this point of view most of sociology, including all the types

designated by Burawoy, is hopelessly presentist and core-centric. Social change

is primarily about the historical development of human social institutions.

Social change has been a singular world historical process increasingly since

the sixteenth century. So telling stories of national societies as if they

occurred on separate planets is a major distortion of reality for both social

science and for progressive politics.

Contemporary social change can only be

comprehended in its world historical context. Focusing solely on the United

States, as most sociologists and most other people in the U.S. do, makes it

impossible not only to understand the extremely important world historical

events and developments that are occurring elsewhere, but also precludes

understanding of what is happening within the United States. Why did politics

in the

What are the implications of the above for Burawoy’s

public sociology project? His search for the relevant publics for public

sociology is a good idea, but the relevant publics need to be understood as

parts of an emerging global civil society. World sociology needs to analyze

non-U.S. realities and the whole emergent global system of which the

The crucial slip in Burawoy’s description of what

happened in sociology and what happened in the

Waves of Globalization

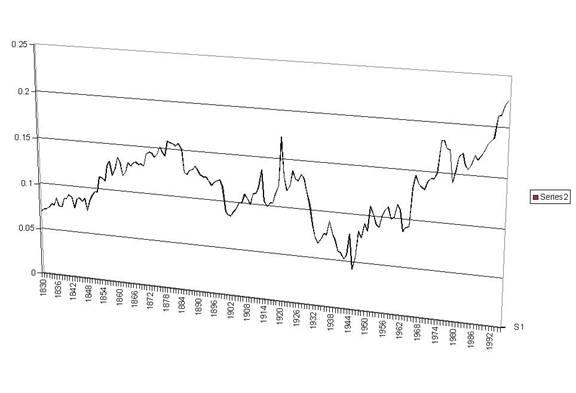

Understanding contemporary globalization requires that we compare the wave of globalization since World War II with earlier waves, especially the last half of the nineteenth century when international trade as a proportion of the whole world economy was nearly as high as it is now (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000). It is important to distinguish between globalization as large-scale connectedness, which is a structural and empirical question about economic, political, cultural and communications network linkages, and the “globalization project,” which is the political ideology of Reaganism-Thatcherism that became hegemonic in the 1980s (McMichael 2004). One reason why many see the contemporary wave of globalization as a completely new stage of global capitalism is that nationalism and Keynesian national development policies were powerfully institutionalized and centrally propagated from World War II until the 1970s. The Keynesian national development project (the Global New Deal) was itself a world historical response to the “Age of Extremes” (Hobsbawm 1994) and the deglobalization of the early decades of the twentieth century. It never really created a world of separate national economies, but it did focus strong attention on the problem of national import substitution and the development of the national welfare state. This focus on national policy is what allows many of the contemporary analysts of global capitalism to imagine that the world was really composed of separate national societies before the most recent wave of globalization.

Figure 1: Trade Globalization 1830-1994

A profit squeeze and accumulation

crisis occurred in the 1970s when

Neoliberalism was a political ideology that took hold and became hegemonic beginning in the 1970s. It was a revival of the nineteenth century ideology of “market magic” and an attack on the welfare state and organized labor. It borrowed the anti-statist ideology of the New Left and used new communications and information technologies to globalize capitalist production, undercutting nationally organized trade unions and attacking the entitlements of the welfare state as undeserved and inefficient rents. This “global stage of capitalism” is what has brought globalization into the popular consciousness, but rather than being the first time that the world has experienced strong global processes, it was a response to the problems of capitalist accumulation as they emerged from the prior Global New Deal, which was itself a response to the earlier Age of Extremes and deglobalization. This is what I mean by saying that social change is world-historical.

The pace of

global social change accelerated dramatically with the late eighteenth century

industrial revolution, culminating in the first wave (1840-1900) of what can

properly be called globalization in the sense of Earth-wide integration and

connectedness. The United Kingdom of Great Britain was the world leader in

industrialization, an exporter of the key technologies (railroads, steamships

and telegraph communications) and the advocate of free trade policies and the

gold standard (O’Rourke and Williamson 2000). As

The decline

of British hegemony was accompanied by a downturn of trade globalization from

1880 to 1900 and then by a period of interimperial rivalry – two world wars

with

World Wars I and II were long and massively destructive battles in a single struggle over who would perform the role of hegemon. Between the wars was a short wave of economic globalization in the 1920s followed by the stock market crash of 1929 and a global retreat to economic nationalism and protectionism during the depression of the 1930s. Fascism was a virulent form of zealous nationalism that spread widely in the second tier core and the semiperiphery during the Age of Extremes. This was deglobalization.

The point here is that globalization is not just a long-term trend. It is also a cycle. Waves of globalization have been followed by waves of deglobalization in the past, and this is also an entirely a plausible scenario for the future.[2]

The

The

Mass education created a large throng of not-yet

politically incorporated students in all the countries of the world, and this

group led the world revolution of 1968, a protest against the capitalist

welfare state, the shams of parliamentary democracy and the fakeries of state

communism. In the wake of this political

and cultural challenge and the emergence of a spate of “new social movements,”

core capital experienced a profit squeeze because Germany and Japan caught up

with the U.S. in the production of the most profitable lead technologies, and

so prices could no longer be raised to keep profits high (Brenner 2002).

This spurred a change of strategy by the now-global

capitalist class in which the Keynesian national development project that had

justified the capitalist welfare state and the developmental programs in the

periphery and semiperiphery was scuttled in favor of Reaganism-Thatcherism.

Free markets were to replace government intervention. Downsizing, streamlining,

attacks on politically guaranteed entitlements, all this was justified by the eighteenth

century idea that the market is the most efficient and fairest arbiter of human

interactions.

With

new technologies of communications, transportation and infomatics businesses

were able to relocate to take advantage of cheaper labor costs, lower tax

rates, and less environmental protection.

This was the globalization project and the new international division of

labor (McMichael 2004). Industry moved from the core to the semiperiphery and

the periphery. New lead technologies

(the Internet, biotechnology) were touted as the potential basis for a new

round of

To make a long story short, with a few important

differences, the world-system is repeating what happened during the decline of

British hegemony at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning decades

of the twentieth century. To be sure, the

But

the basic logic of capitalist uneven development and the mismatch between the

economic and political structures are quite similar. The hegemon is desperately trying to stay on

top. Financial centralization only works for a while. It is the first card that

is played, but when the potential for instability and collapse becomes obvious,

the powers-that-be pull out their other remaining card: military capability.

This produces what has been called the “new imperialism “ (Harvey 2003) and the

neo-conservative “Global Gamble” (Gowan 1999).

Oil is running out. If “we” can control global oil the potential challengers

(

Some see this as pouring gasoline on the smoldering coals

of resistance. It appears to blatantly contradict the very ideologies of

equality and democracy that the

The continuing decline of

In the

The contemporary wave of global industrialization based on fossil

fuel may have already led to a substantial overshoot in the ability of human

society to sustain a livable biosphere. If this is the case we may encounter

environmental disasters that require global cooperation in order to restore the

balance between human society and the natural systems upon which it depends.

Another round of conflict over global hegemony may be forthcoming despite the

current monopolization of serious military power by the

If

this sounds gloomy, I want to also point out that the coming period of

contestation is an opportunity to create global democratic cooperative

institutions that set up a more sustainable relationship between human society

and the natural environment and more humane and just relationships among the

peoples of the world. A global democratic and collectively rational

commonwealth will probably emerge eventually, unless we manage to completely

extinguish ourselves (Wagar 1999). With intelligent political action based on a

world historical understanding of global social change, it is possible that this

will emerge sooner rather than later.

A new call is rising from global civil society and from

those countries in the semiperiphery that have both the motivation and the

means to resist global corporate capitalism. The World Social Forum (Fisher and

Ponniah 2003) is a movement of movements and a forum for organizing a global

party (or parties) that will challenge the transnational capitalist class.

Another world revolution is in the making. Global public social science needs

to explain world historical processes to people and to actively engage with

global civil society so that the worst excesses of deglobalization can be

(hopefully) avoided and we can move toward a democratic and collectively

rational global commonwealth (Wagar 1999; Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000).

I have declared the value of disciplinary sociology above

in my discussion of the centrality of professional sociology. But many of the

institutional boundaries between contemporary social science disciplines are

annoying obstacles to both the scientific and the political understanding of

social reality. I do not recommend abolishing the disciplines, but rather that

a sizeable number of professional and public sociologists should learn the

basics of theories and methods in geography, history, political science,

economics, ecology and anthropology. This will allow the disciplinary blinders

to be thrown off without wrecking the good parts of the disciplines.

Global Public Social Science

So what is global public social science? And,

following Burawoy’s typology, what are global professional, critical and policy

social science? The short answer is that these all take the emergent Earth-wide

human system as an important unit of analysis in its own right, although other

entities are also important. Global professional social science studies social

realities (culture and institutions, politics, inequalities, transnational

relations, globalization processes, etc.) on a global scale using the

methodological tools and theoretical perspectives of the social sciences.

Examples in economics, geography, political science, history, anthropology and

sociology are too numerous to enumerate here. Michael Burawoy’s (2000) work on

global ethnography is certainly a valuable exemplar.

Global critical social science critiques, deconstructs

and reformulates important global social science concepts (such as

globalization) as well as global institutions. It also proposes critical ways

of categorizing social forces, contradictions and antagonisms in ways that are

intended to be of use for transnational social movements. This is also a

voluminous literature. Important recent examples are Michael Hardt and Antonio

Negri’s (2004) Multitude, a valiant effort to rethink political theory

for the purposes of building global democracy, and Amory Starr’s (2000) Naming

the Enemy, an analysis of the main dimensions of the antiglobalization

movements and a structural conceptualization of global corporate capitalism as

the enemy that must be confronted.

Global policy social science would seem to be an unlikely

activity, since there is (currently) no true world state that could implement

global policies. There are, however, important global institutions that do

formulate and try to implement global policies (e.g. the United Nations, the World

Bank, etc.). But all people now need to formulate global policies because

everyone lives in a global polity, a global economy, and an increasingly

globalized set of cultures. Global policies are planful ways of coping with

global economic, political and social forces.

Global Policy Institutes (by that name or some close variant) now exist

in New York, Geneva, Berlin, Honolulu, and at the University of Virginia at

Charlottesville, and many public policy institutes and centers all over the

world are establishing globally oriented policy research programs.

Global

public social science refers to social scientists who use their research skills

and analytic abilities to address global civil society and in the service of

transnational social movements. Burawoy reminds us that one of our important

publics is our undergraduate students. Teaching and writing textbooks for

undergraduates is an important part of public sociology. A growing number of

universities have established interdisciplinary undergraduate majors in global

studies (e.g. University of

The

Global Studies Association (http://www.net4dem.org/mayglobal/index.htm)

has had several exciting conferences and it has been attacked by right-wing

ideologues as famous as Michael Horowitz. This red badge of courage may be the

highest credential in public social science. Some very useful textbooks and

readers for global studies courses are those by McMichael (2004), Hall (2000)

and Chase-Dunn and Babones (2006).

Research

at the behest of global civil society is another important activity of global

public social science. A large corpus of the research and published monographs

and journal articles comprising global professional social science serves

global civil society and transnational social movements. My recent favorites

are Rich Appelbaum and Edna Bonacich’s (2000) Behind the Label, Stephen

Bunker and Paul Ciccantell’s (2005) Globalization and the Race for

Resources, big historian David Christian’s (2004) inspiring Maps of Time,

Jared Diamond’s (2004) Collapse, Michael Mann’s (2003) Incoherent

Empire, Valentine Moghadam’s Globalizing Women (2005), J.R. and

William McNeill’s (2003) The Human Web, William I. Robinson’s (2004) A

Theory of Global Capitalism, Beverly Silver’s (2004) Forces of Labor and

Immanuel Wallerstein’s (2003) The Decline of American Power. These are

works of professional sociology that serve global civil society and local

groups trying to deal with the forces of globalization by providing research

and theories that help people understand what is going on.

But

Burawoy’s most important precept of public sociology endorses direct

interaction with, and participation in, civil society groups, and research that

is directed toward helping these groups achieve their goals. Since, as I have

pointed out above, everyone now needs to deal with the issues and forces of

globalization, practically any project could qualify. But I will focus on the

research of those who have studied and participated in transnational social

movements. Arguably social movements have been importantly transnational at

least since the nineteenth century in the sense that the conceptual frames, collective

action repertoires, and

communications networks already involved intercontinental interaction,

migration, and flows of other important resources (Keck and Sikkink 1998). But

here I will discuss social science research on, and involvement with, the

emerging movements that have focused on contemporary globalization. I already

mentioned Amory Starr’s (2000) excellent contribution to global critical

sociology above. Starr’s new book (2005), Global Revolt, is an inspiring

and informative “how-to-do-it” manual for antiglobalization activists based

mainly on Starr’s intensive participant observation in anti-globalization

protest demonstrations.[3]

Jackie Smith’s (Smith and Johnston 2002, Smith

2004) studies of transnational social movements are based on both careful

formal analyses of systematic data and Smith’s involvement with, and

participation in, the movements she is studying. Bruce Podobnik’s (2004)

studies of the changing location and frequency of anti-globalization protest

events is another important contribution, and the new book that he co-edited

with Tom Reifer (Podobnik and Reifer 2005) contains several works that must be

included in a survey of global public sociology. I have already mentioned the important work

by Thomas Ponniah and William Fisher (2003) on the World Social Forum.

UCR Project on Transnational Social Movements

At

the University of California-Riverside (UCR) the Research Working Group on

Transnational Social Movements has undertaken a study of the participants in

the World Social Forum that is intended to help the participating groups better

understand the contradictions and overlapping issues and agendas among the

movements so that they might be better able to cooperate and collaborate with

each other in forming a credible and effective political force in world

politics. Professor Ellen Reese and I organized the research working group,

which is composed of graduate and undergraduate students at UCR, most of whom

are majoring in sociology.[4]

This participant observation and survey research is sponsored by the UCR

Institute for Research on World-Systems (irows.ucr.edu). Ellen and five of our

students attended the 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil where

they obtained over 600 written responses to a survey questionnaire (in

Portuguese, Spanish and English)

(irows.ucr.edu/research/tsmstudy/wsfsruvey.htm) that gathers information on the

backgrounds of participants and their involvements in different kinds of issues

and social movements. We also asked respondents to help us identify possible

contradictions among the participating transnational social movements, and to

suggest ways in which two well-known contradictions might be overcome

(see http://www.irows.ucr.edu/research/tsmstudy.htm). [5]

Figure 2: UCR Transnational Research Working Group

surveyors at the World Social Forum in

At

the time of this writing we are still in the midst of processing and analyzing

the survey results. We will present papers based on our research at the annual

meetings of the Society for the Study of Social Problems, the American

Sociological Association, the International Studies Association and the World Congress

of Sociology in

The

issue of representation and legitimacy is a huge one for the participants at

the World Social Forum and our study will be able to add to the available

knowledge about who attends and what participants believe about representation.

Earlier research (Schonleitner 2003) found that a majority of the attendees are

majoring in, or have undergraduate or graduate degrees in, social sciences and

our survey confirms this. The activists in the emerging global civil society,

who are very concerned about the extent to which poor and disadvantaged groups

are able to participate in global politics, are themselves mainly people who

have training in the social science disciplines. This simple fact speaks

volumes about the complementary relationship between global professional and

public social science and also about the real makeup of global civil society.

Gramsci,

Gouldner and many other observers of social change have long noted the

important role of intellectuals in both sustaining and challenging the

structures of power. That most of the activists in global civil society are

trained in the social sciences would come as no surprise. The reaction of

popular forces against global corporate capitalism and the ideology of

neoliberalism is generating new constellations of ideas and new forms of

organization. Elites have long participated in the global polity as statesmen,

diplomats, publicists, scientists, religious leaders and etc. What is happening

now is the emergence of large transnationalized segments of the popular classes

who are using new information technologies to organize globally. The World

Social Forum is the most important arena for the organization of global

networks and parties that claim to represent the peoples of the Earth (Gill

2000). The processes of party-network formation are what we are studying, and

also what we intend to facilitate. This is both professional and public global

social science.

References

Appelbaum, Richard and

Edna Bonacich 2000 Behind the Label.

Arrighi, Giovanni,

Terence K. Hopkins, and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic

Movements.

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The

Long Twentieth Century.

Boswell, Terry and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral of Capitalism and Socialism:

Toward

Global Democracy.

Brenner, Robert 2002 The

Boom and the Bubble: The

Burawoy, Michael 1979 Manufacturing

Consent.

Burawoy, Michael 1985 The

Politics of Production: factory regimes under capitalism and socialism.

Burawoy, Michael et

al. 2000 Global Ethnography.

Burawoy, Michael 2005

“2004 ASA Presidential Address: For public sociology” American

Sociological

Review 70,1:4-28 (February).

in

Mark Herkenrath, et al (eds.) The Future of World Society.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Yukio Kawano and Benjamin D. Brewer 2000 “Trade

globalization

since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system.” American

Sociological

Review 65,1: 77-95 (February).

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Salvatore Babones (eds.) 2006. Global Social Change: Comparative

and Historical Perspectives.

Fisher, William F. and

Thomas Ponniah 2003 Another World Is Possible: Popular Alternatives to

Globalization

at the World Social Forum.

new

politics of globalization” Millennium 29,1: 131-140.

Gowan, Peter

1999 The Global Gamble:

Hall, Thomas D. (ed.)

2000 A World-Systems Reader.

Hardt, Michael and

Antonio Negri 2004 Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire.

Harvey, David 2003 The

New Imperialism.

Hobsbawm, Eric 1994 The

Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991. New

Jeffries, Vincent 2005 “Piterim A. Sorokin’s

Integralism and Public Sociology” American Sociologist. American

Sociologist, Vol 36.

Keck, Margaret E. and

Katherine Sikkink. 1998. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in

International Politics.

Lipset, Seymour Martin

1963 The First New Nation: The

Mann, Michael 2003 Incoherent Empire.

McMichael, Phillip 2004 Development and Social

Change.

Forge Press

Moghadam, Valentine 2005 Globalizing Women.

O’Rourke, Kevin H. and Jeffrey G. Williamson 2000 Globalization

and History.

Podobnik, Bruce 2004

“Resistance to globalization: cycles and evolution in the

globalization

protest movement” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the

American Sociological

Association,

Podobnik, Bruce and

Thomas Erlich Reifer (eds.) 2005 Transforming Globalization: Challenges and

Opportunities in the Post 9/11 Era.

Robinson, William I. 2004

A Theory of Global Capitalism.

University

Press.

Sachs, Jeffrey 2005 The

End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities of Our Time.

Schönleitner, Günter 2003

"World Social Forum: Making Another World Possible?" Pp.

127-149

in John Clark (ed.): Globalizing Civic Engagement: Civil Society and

Transnational

Action.

Silver, Beverly 2003 Forces

of Labor.

Smith, Jackie 2004 “The

World Social Forum and the challenges of global democracy.”

Global Networks 4,4:413-421.

Smith, Jackie and Hank

Johnston (eds.). 2002. Globalization and Resistance:

Transnational

Dimensions of Social Movements.

Littlefield.

Starr, Amory 2000 Naming

the Enemy: Anti-corporate Movements Confront Globalization.

Zed Press.

Starr, Amory 2005 Global

Revolt: A Guide to the Global Revolt Against Globalization.

Silver,

Beverly and Giovanni Arrighi 2005 “Polanyi's

‘Double Movement’:

The

Belle Époques of British and

Friedman and Christopher Chase-Dunn

(eds.) Hegemonic Declines: Present and

Past.

Wagar, Warren W 1999 A Short History of the

Future.

Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel 2003 The Decline of

American Power: the

World.