The Trajectory of the United States in the World-System: A Quantitative Reflection

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Rebecca Giem,

Andrew Jorgenson, Thomas Reifer, John Rogers

and Shoon Lio

Department of Sociology and Institute for Research

on World-Systems

University of California, Riverside

http//:irows.ucr.edu

IROWS

Working Paper # 8

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows8/irows8.htm

University of California, Riverside.

Riverside, CA. 92521

City

lights from satellite photographs

Abstract: Revised estimates of world GDP, population and GDP

per capita published by Angus Maddison (2001) make possible a quantitative

reexamination of the trajectory of the United States in world historical

perspective and comparisons between the U.S. economic hegemony of the twentieth

century with the Dutch hegemony of the seventeenth century and the British

hegemony of the nineteenth century. We also track the trajectories of

challengers to reflect on the future of hegemonic rivalry.

To be presented at the XV ISA World Congress of Sociology, Brisbane,

Australia, Wednesday, July 10, 2002, 1:30-5:30pm Sessions on “American Primacy or American

Hegemony?” Research Committee on Comparative Sociology, organized by Neil

Smelser and Mattei Dogan.

Draft

V. 7-2-02, 8969 words)

Concerns about empire, hegemony and the

distributions of power and wealth among the peoples of the world are both au

courant and deeply historical. An institutionalized global culture of human

rights and equality shines an embarrassing floodlight on the objective rise of

within-nation and global inequalities generated by state-corporate

globalization. This is producing a renewed reaction against the wave of

marketization and commodification of human social relations that is likely to

be similar in some respects to the globalization backlash that occurred during

the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This Polanyian (Polanyi

2001) “double-movement” of

commodification and the reassertion of political regulation over market forces

is an old phenomenon that reinvents itself in unique ways every time it comes

around, depending on the exact nature of the problems that need to be solved

and the actions of the agents who mobilize to solve them. An important

component of this elaborate dance is the recurrent phenomenon of “rise and

fall,” the centralization and decentralization of political/military and

economic power that is a characteristic of all hierarchical world-systems.

Complex

interchiefdom systems experienced a cycle in which a single paramount chiefdom

became hegemonic within a system of competing polities (Anderson 1994;

Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 5). Once states emerged within a region they

went through an analogous cycle of rise and fall in which a single state became

hegemonic and then declined. Eventually these systems of states (interstate

systems), experienced the phenomenon of semiperipheral marcher conquest

in which a new state from out on the edge of the circle of old states conquered

all (or most) of the states in the old core region to form a “universal empire”

(see Figure 1).

This

pattern repeated itself for thousands of years, with occasional leaps in which

a semiperipheral marcher state conquered larger regions than had ever before

been subjected to a single power ( Akkad, Assyria, Achaemenid Persia,

Alexandrian Hellenism, the Han Empire, Rome, the Islamic Caliphates, the Aztec

and Inca Empires, the Manchu Dynasty in China).

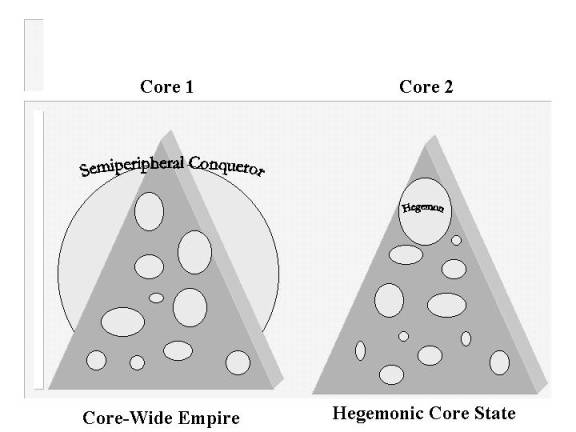

Figure 1:

Core-Wide Empire vs. Hegemonic Core State

With

the rise of Europe and intensified capitalism a modification of this old

pattern appeared. In the European interstate system the semiperipheral marcher

states were outdone by a new breed of capitalist nation-states. These

capitalist hegemons established primacy in the larger system without conquering

adjacent core states, and so the core remained multicentric despite the

continued rise and fall of hegemonic core powers. Imperialism was reorganized

as colonial empires in which each core state had its own peripheral “backyard.”

The efforts by some core powers to conquer their neighbors were defeated by

coalitions that sought to reproduce a multistate structure among core states.

Thus the oscillation between “universal state” and “interstate system” came to

end and was replace by the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers. The

hegemonic sequence of the modern interstate system alternates between two

structural situations as hegemonic core powers rise and fall: hegemony and

hegemonic rivalry. This was a new form of the process of rise and fall (see

Figure 2).

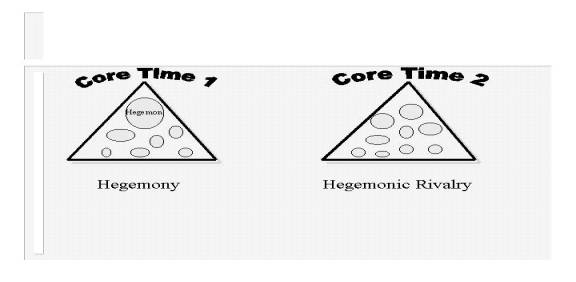

Figure 2: Unicentric vs. Multicentric Core

The

Westphalian interstate system, in which the sovereignty of separate and

competing states is institutionalized by the right of states to make war to

protect their independence, has become a taken for granted institution in the

modern world-system. Historians of international relations (e.g. Kennedy 1987) and theorists of international

relations (e.g. Waltz 1979) have come to define this situation as a natural

state of being. Authors with greater temporal depth (e.g. Wilkinson 1988, 1999)

have argued that the peculiar resistance of the modern interstate system to the

emergence of a universal state by means of conquest has been the result of an

evolutionary learning process unique to modern Europe in which states realized

that in order to protect their own sovereignty they should band together and

engage in “general war” whenever a “rogue state” threatens to conquer another

state.

A rather different explanation of the modern

transition from the pattern of semiperipheral marcher state conquest to the

rise and fall of hegemonic core powers points to the emergent predominance of

capitalist accumulation in the European-centered interstate system. Once capitalism had become the predominant

strategy for the accumulation of wealth and power it partially supplanted the

geopolitical logic of institutionalized political coercion as a means to

accumulation. Powerful capitalist core states emerged that could effectively

prevent semiperipheral marcher states from conquering whole core regions to

erect a “universal state.” The first capitalist-nation state to successfully do

this was the Dutch republic of the seventeenth century.

New Quantitative Data on Economic Hegemony

Angus Maddison (2001) has published a revision and

extension of his long-range estimates of populations, gross domestic products

and levels of economic development of countries and world regions. His most

recent endeavor presents quantitative snap-shots of economic and demographic

change over the past 2000 years. In this paper we combine the more detailed

estimates from Maddison’s (1995) earlier publication with the more recent and

revised estimates published in 2001 to paint a quantitative picture of the

trajectories of economic hegemony in the modern world-system.

Maddison’s

estimates make it possible examine the relative sizes and levels of development

of the national states and how these have changed over time. The necessary methodological operation for

these economic estimates has been to transform statistical evidence from all

over the world and from earlier centuries into a single comparable metric –

1990 “international dollars.” Maddison

(2001:171-175) carefully explains and justifies his use of PPP (purchasing

power parity) estimates rather than currency exchange rates to convert country

currency data into constant dollars. Purchasing power parity estimates convert

GDP estimates denominated in country currencies into one another by estimating

comparable purchasing power for consumer goods and the other elements that

compose the Gross Domestic Product. Maddison has worked for years on efforts to

produce comparable estimates for very different kinds of accounting systems

(e.g. the Net Material Product of centrally planned economies) and for

different kinds of economies (e.g. highly monetized vs. the partially monetized

economies in the periphery of the world-system). Maddison applies all this

experience to the most difficult task he has yet undertaken – the valuing of

the economic activity of premodern world regions. These quantitative estimates shed important light on the various

contentions of the social scientists and historians who have made comparisons

of the modern hegemons.

There has been a vociferous debate over

terminology that reflects underlying theoretical and disciplinary differences

among those who have sought to compare power processes over recent centuries.

As David Wilkinson has said, our concepts contain the bones of our disciplinary

ancestors. Some historians and

historical sociologists, while making the requisite comparisons between Dutch,

British and U.S. histories, reject the idea that these histories should be

considered instances of a single phenomenon(e.g. Mann 1993; O’Brien 2002). In

other words, they stress the differences to the extent of trivializing the

similarities, though the particular differences they stress are themselves

different. Both Mann and O’Brien refuse to characterize the role of Britain

during the Pax Britannica as hegemonic, especially as compared with the

superpowerdom of the United States in the post-World War II period. Britain is

seen as a fore-reacher leading the world in the ways of industrialization and

democracy, but not as a controller or exploiter of other countries. The

question of the relative size of the British economy in the larger world

economy during the nineteenth century compared with relative size of the U.S.

economy during the twentieth century is a matter that we shall investigate

below.

Among those who are more willing to analyze

structural similarities across different historical periods, the ways in which

these similarities are defined vary greatly. Several dimensions are at play in

these differences. One important distinction among theorists is between the

functionalists (who see emergent global hierarchies as serving a need for

global order,) and conflict theorists (who dwell more intently on the ways in

which hierarchies serve the privileged, the powerful and the wealthy). The term

“hegemony” usually corresponds with the conflict approach, while the

functionalists tend to employ the idea of “leadership,” though several analysts

occasionally use both of these terms (e.g. Arrighi and Silver 1999). Another

difference is between those who stress the importance of political/military

power vs. what we shall call “economic power.” This issue is confused by disciplinary

traditions (e.g. differences between economics, political science and

sociology). Most economists entirely reject the notion of economic power,

assuming that market exchanges occur among equals. Most political scientists

and sociologists would agree that economic power has become more important than

it formerly was. Some of the literature

on recent globalization goes so far as to argue that states and military

organizations have been completely subsumed by the power of transnational

corporations and global market dynamics (e.g. Ross 1995; Robinson 1998).

Rather

than reviewing the entire social science corpus of theories, we will describe

four contrasting and overlapping approaches in some detail – those of

Wallerstein (1984, 2002), Modelski and Thompson (1994); Arrighi (1994) and

Rennstich (2001, 2002). Wallerstein defines hegemony as comparative advantages

in profitable types of production. This economic advantage is what serves as

the basis of the hegemon’s political and cultural influence and military power.

Hegemonic production is the most profitable kind of core production, and

hegemony is just the top end of the global hierarchy that constitutes the

modern core/periphery division of labor. Hegemonies are unstable and tend to

devolve into hegemonic rivalry.

Wallerstein

sees a Dutch seventeenth century hegemony, a British hegemony in the nineteenth

century and U.S. hegemony in the twentieth century. He perceives three stages within each hegemony. The first is

based on success in the production of consumer goods; the second is a matter of

success in the production of capital goods; and the third is rooted in success

in financial services and foreign investment stemming from the

institutionalized centrality of the hegemon in the larger world-system.

George Modelski and William R. Thompson

(1994) are political scientists whose theoretical perspective contains a strong

dose of Parsonsian structural functionalism as applied to international

systems. The world needs order and so world powers rise to fill this need. They

rise on the basis of economic comparative advantage in new lead industries that

allow them to acquire the resources needed to win wars among the great powers

and to mobilize coalitions that keep the peace. World wars are the arbiters that

function as selection mechanisms for global leadership. But the comparative advantages of the

leaders diffuse to competitors and new challengers emerge. Successful

challengers are those that ally with the declining world leader against another

challenger (e.g. the U.S. and Britain against Germany).

Modelski

and Thompson (1994) measured the rise of certain key trades and industries,

so-called “new lead industries,” that are seen as important components of the

rise of world powers. They also have measured the degree of concentration of

naval power in the European interstate system since the fifteenth century

(Modelski and Thompson 1988). Their “twin peaks” model posits that each “power

cycle” includes two Kondratieff waves.[1] Their list of world powers begins with

Portugal in the fifteenth century. Then they include the Dutch period of world

leadership in the seventeenth century. And they see the British as having

successfully performed the role of world leader twice, once in the eighteenth

century and again in the nineteenth century. Thus they introduce the

possibility that a world leader can succeed itself. They designate the United

States as the world leader of the twentieth century.

Giovanni

Arrighi’s (1994) The Long Twentieth Century employs a Marxist and

Braudelian approach to the analysis of what he terms “systemic cycles of

accumulation.” Arrighi rejects any consideration of K-waves as being unrelated

to theories of capitalist accumulation.[2]

He sees hegemonies as successful collaborations between capitalists and

wielders of state power. His tour of the hegemonies begins with Genoese

financiers who ally with Spanish and Portuguese statesmen to perform the role

of hegemon in the fifteenth century. In Arrighi’s approach the role of hegemon

itself evolves, becoming more deeply entwined with the organizational and

economic institutional spheres that allow for successful capitalist

accumulation. He sees a Dutch hegemony of the seventeenth century, then a

period of contention between Britain and France, and a British hegemony in the

nineteenth century, followed by U.S. hegemony in the twentieth century. A

distinctive element of Arrighi’s approach is his contention that profit making

from trade and production becomes more difficult toward the end of a ‘systemic cycle

of accumulation” and so big capital becomes increasing focused on making

profits through financial manipulations.

Arrighi’s approach is compatible with the idea that new lead industries

are important in the rise of a hegemony, but he sees the economic activities of

big capital during the declining years in terms of speculative financial

activities. These latter often correspond with a period of “growth” in which

incomes are rising during a latter-day belle époque of the systemic

cycle of accumulation. But this period of accumulation is based on the economic

power of haute finance and the centering of world markets in the global

cities of the hegemons rather than on their ability to produce real products

that people will buy, and so these belle époques are unsustainable and

are followed by decline.

Recent research by Joachim Rennstich (2001) retools Arrighi’s (1994) formulation of the reorganizations of the institutional structures that connect capital with states to facilitate the emergence of larger and larger hegemons over the last six centuries. Modelski and Thompson (1996) argued that the British successfully managed to enjoy two “power cycles,”[3] one in the eighteenth and another in the nineteenth century. With this precedent in mind Rennstich considers the possibility that the U.S. might succeed itself in the twenty-first century. Rennstich’s analysis of the organizational, cultural and political requisites of the contemporary new lead industries – information technology and biotechnology – imply that the United States has a large comparative advantage that will most probably lead to another round of U.S. pre-eminence in the world-system. He argues that a hegemon can succeed itself if the rising industrial sectors within the hegemon are able to separate themselves sufficiently from the old declining industrial sectors. Rennstich focuses on the regional and institutional differences between old and new sectors of the U.S. economy.

Earlier

studies have often most often proceeded by designating particular countries or

networks as hegemonic during certain periods and dividing these periods up into

subperiods. Only a few studies have quantitatively compared the hypothesized

hegemons with other core powers or subjected the subperiodizations to

quantitative analysis. Modelski and Thompson (1988) examined the distribution

of naval power among the “great powers” of the European interstate system since

the fifteenth century. This is the most thorough and comprehensive quantitative

study that actually measures hegemony by comparing contending countries over a

long period of time. Modelski and Thompson’s (1996) quantitative study of new

lead industries does not break these down by country.

Using

economic (total GDP and per capita GDP) and military indicators (military

expenditures) to create composite measures of power in the world-economy,

Kentor (2000) explores the changes in core power and hegemony by providing

snapshots profiles for core countries in 1820, 1900, 1930, 1950, 1970, and

1990. Results indicate that in 1820,

the U.K. was the dominant core power with an overall standardized composite

score twice that of its nearest rival, France (Kentor 2000). The U.K.’s relative strength came primarily

from its level of capital intensity (as indicated by GDP per capita), and

military strength. By 1900,

relationships between core powers had changed dramatically. The U.K. still possessed the highest overall

score, but its strength was based primarily upon its military power. The U.S.

and China had surpassed the U.K. in output, and the U.S. was approaching the

U.K.’s level of capital intensity (Kentor 2000). The shift in hegemony was quite evident by 1930 where the U.S.

achieved dominance through its advantage in national output. In 1950, national output for the U.S. had

grown to more than three times that of its nearest rival (USSR), its relative

level of capital intensity was twice that of the U.K., and its relative level

of military power increased to an almost identical level with the USSR (Kentor

2000). By 1970 U.S. relative military

strength had increased while its advantages in output and capital intensity had

declined. By 1990 the USSR lost its

military dominance, Japan had continued its rise in the world-economy with

increases in all areas, China had grown to the second largest producer in the

world-economy, and the U.S. had increased its global dominance with relative

growth in all three power dimensions (Kentor 2000).

The

relationship between population and intersocietal power is complicated and has

changed greatly as new techniques of power have evolved. Polities with more

people have often been able to exercise power over polities with fewer people

because more people means more warriors in a confrontation. But this

relationship has been complicated by other factors. Military technology and

organization, solidarity within societies, transportation and communication

technology, logistics and geography are factors that have influenced

geopolitics somewhat independently of demography. And demography itself has

several dimensions. A polity may have large numbers, but where are they located

and how are they organized and how quickly can they communicate with one

another? What are the advantages conferred by geographical location? What kinds

of societies can more effectively innovate and implement new strategies and

techniques of power?

The

phenomenon of semiperipheral development (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 5)

points to a recurrent pattern in which smaller, less stratified, and less

population dense semiperipheral societies outcompete older core societies that

have higher population densities. These issues need to be sorted out by a

systematic comparative study of the relationships between different dimensions

of demography (total population, population density, settlement sizes and

locations) and different dimensions of intersocietal power relations. Maddison’s (1995, 2001) revised estimates of

population sizes of regions and polities provide us with a fresh opportunity to

examine the question of size and power.

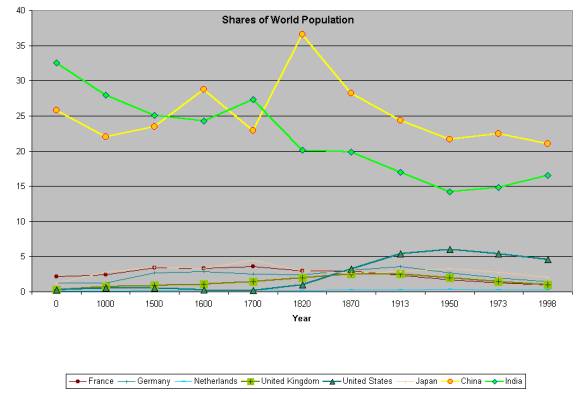

Figure 3: Shares of World Population, Last Two Thousand Years

Figure 3 shows shares of the total global population since the beginning of the Common Era two thousand years ago according to Maddison’s (2001) estimates. The time scale on the horizontal axis of Figure 3 is misleading because the intervals are not equal. Keeping this in mind we can see that the countries that became hegemonic in recent centuries were never very significant and did not change much in terms of their shares of world population. The countries with the big shares, India and China, still have huge shares, though India declined quite a lot until 1950 and then begins to rise again. China peaked in 1820 and has mainly been declining since then. The United States rose above 5% of world population in 1913 and dropped below that level in about 1985.

Is the total population of a region related to its power vis a vis other regions with smaller populations? This is part of the question of demographic power. Other dimensions of demographic power include relative population densities, and the sizes of settlements and cities. Total population size is obviously partly a reflection of territorial size. The “China” and “India” in Maddison’s data are regions rather than single unified polities through the time span shown in Figure 3. Another potential problem with Figure 3 is the “systemness” of the included regions. It is usually presumed that China and India were not strongly connected with Europe and the Americas during the whole period shown. In the case of the Americas this is obviously true. The European countries only became linked directly through political/military interactions with India and China in the last few centuries, though pan-Eurasian prestige goods trade was already well developed two thousand years ago. Relative power assumes regularized interaction. We contend that regularized interaction networks should be the proper unit of analysis for studying world-systems (see Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997).

Figure 3 tells an important story despite its temporal and spatial problems. East Asia and South Asia were the population centers of the Earth, but have become less so over the past two millennia. But total population size is not very useful indicator of demographic power. Population density, urbanization (the proportion of total population living in cities (urbanization), and the sizes of the largest cities are much better reflections of the kinds of power that greater population confers. A recent study of the sizes of the largest cities in world regions over the past four millennia has demonstrated that the largest European cities began increasing their shares of population of the world’s 20 largest cities in the thirteenth century of the Common Era (Chase-Dunn and Manning 2002). Contra Andre Gunder Frank (1997), the rise of Europe was not a last minute development that occurred in the late eighteenth century. Formerly peripheral Europe had been developing its own internal core region and expanding its cities and the power of its states for hundreds of years by the time China was finally eclipsed in the nineteenth century.

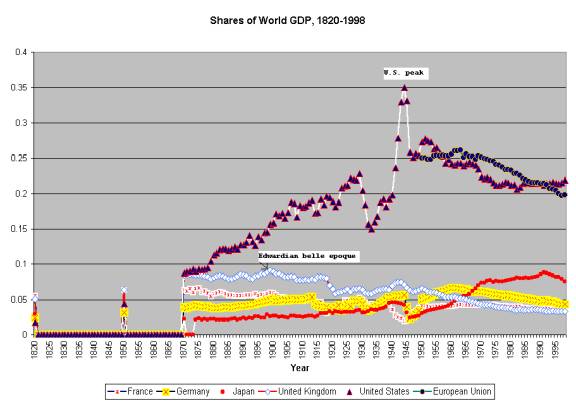

Total GDP combines both economic development and economic

size. It rises simply because there are more people. Thus a graph of shares of

world GDP over the last two millennia looks quite similar to Figure 3 above

until the beginning of the nineteenth century. This is to say that India and

China contained most of the world’s GDP because they contained most of the

world’s population. But after 1800 CE this began to change because of the rapid

increase in GDP per capita in certain European countries and the United States.

Figure 4 (below) shows the shares of world GDP held by the core countries of

the European interstate system since 1820. Maddison (1985) provides estimates

for 1820 and 1850, and then yearly estimates from 1870 on. We have interpolated

his estimates of total world GDP in order to calculate the yearly shares after

1870, and we have added data from Maddison (2001) for the years after

1994.

Figure 4: Shares of World GDP, 1820-1998

Sources: Maddison 1995, 2001.

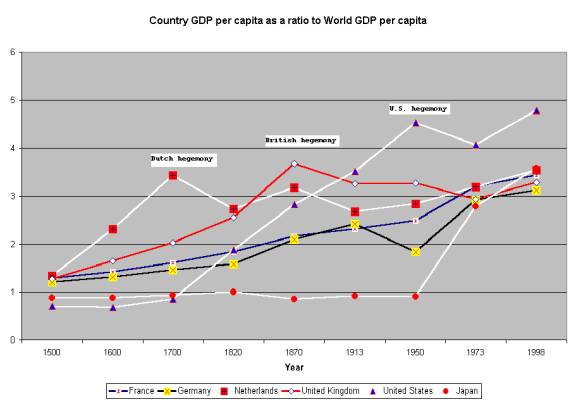

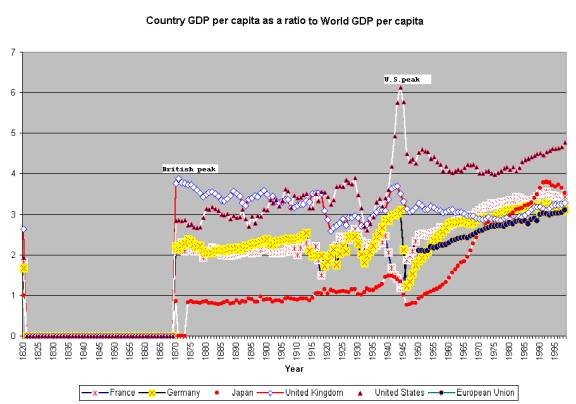

Figure 5: Country GDP per Capita as a ratio to Average World GDP per capita, 1500-1998

Source: Maddison 2001

The first thing we can notice about Figure 5 is that all

the core countries show a general upward trend in the ratio of their national

GDP per capita to the world average GDP per capita. This is an indication that

the trend toward greater inequality between the core and the periphery that has

been noted in recent decades is in fact of long standing. But this is not our

main concern in this paper. Rather we are investigating changes in relative differences

among countries within the core and upwardly mobile semiperipheral challengers.

The seventeenth century economic hegemony of the

Netherlands is indicated by its peak ratio of 3.4 in 1700. Interestingly, the

Netherlands has returned to this same high point in 1998. The difference is

that in 1700 the Netherlands was far ahead of its closest competitor, the

United Kingdom, while in 1998 it was bunched together with all the other

countries, save the United States, which was much higher.

The British hegemony of the nineteenth century is much

more evident in Figure 5 than it was in Figure 4, and its high point appears to

have been in 1870 (but see Figure 6 below). Maddison’s books do not contain

estimates of British GDP per capita between 1700 and 1820 and so we are not

able to see if the Modelski and Thompson contention of a British power cycle in

the eighteenth century would be borne out by comparative economic data.

Figure 5 indicates the long ascent of the United States

to an apparent peak in 1950 (ratio = 4.52), then a decline to 4.06 in 1973, and

rise back to 4.78 in 1998 (but see Figure 6 below). The U.S. ratio in 1998 is

significantly larger than that of the second country as gauged by the GDP per

capita ratio, Japan (ratio = 3.57). The story of Germany and France is a

similar long rise, except for Germany’s dip in 1950. Figure 5 Japan shows no

rise in the GDP per capita ratio until after 1950, contradicting all the

literature about Japanese development after the Meiji restoration (but see

Figure 6 below). Japan’s ascent after 1950 is quite rapid and in 1998 it is

higher than any of the other core countries, save the United States.

In order to more closely examine the temporality of the

changes indicated in Figure 5 we have combined estimates from Maddison’s (1995)

earlier presentation with his updated estimates (2001) to produce Figure

6. Figure 6 uses Maddison’s new

estimates from 1950 on and his yearly estimates from 1870 to 1950 to calculate

the ratio of country GDP per capita to the average world GDP per capita.

Figure 6: Country GDP per capita as a ratio to World GDP per capita, 1820-1998

Sources: Maddison 1995, 2001.

Figure 6 can be compared with Figure 4 above to see the

differences between shares of world GDP and the ratios of country GDP per

capita to world GDP per capita. Figure 6 shows that British capital intensity

was already significantly higher than French capital intensity in 1820, whereas

their shares of world GDP were nearly the same (Figure 4). The French economy

was demographically and territorially larger that the British economy, and this

accounts for their similar size and share of world GDP. But the British economy

was GDP per capita ratio to average world GDP per capita was 2.6, whereas the

French ratio was 1.8. This indicates a significant advantage in average capital

intensity for the British. Figure 6

shows that the British economic hegemony as indicated by relative capital

intensity peaked in 1871, when the British ratio was nearly 3.9. The British

ratio then decline slowly until 1918, when it took a dive to a low point of 2.6

in 1921, from whence it wobbled around below 3 until 1932 and then experienced

a revival to 3.7 in 1943 and then another slow decline to 2.8 in 1977 followed

by a slow rise to 3.3 in 1998.

The trajectory of U.S. relative capital intensity is

similar in many respects to U.S. GDP share as shown in Figure 4 but there are

also some interesting differences. The U.S. rise during the nineteenth century

was steeper by the GDP share measure than by the relative capital intensity

ratio. This is because the U.S. population and territory were growing as fast

as was its relative capital intensity during the nineteenth century. The

capital intensity ratio shows the same peak in 1944 as was revealed in the GDP

shares in Figure 4. But after that the U.S. trajectory is a bit different. The

post-war plummet is followed by a recovery, as was the GDP share indicator, but

the successive plateaus and declines after that are less evident, and there is

a new upward movement that begins in 1982 and reaches a rather high level of

4.8 in 1998. This last might be interpreted as indicating a renewal of U.S.

economic hegemony as hypothesized by Rennstich, but another aspect of Figure 6

needs to be noted. Beginning in the middle of the 1970s all the core powers

have been increasing their relative capital intensities. This is because global

inequality has been increasing for the last three decades, with the core

countries experiencing greater growth in GDP per capita than most of peripheral

and semiperipheral countries. The rise in relative capital intensivity for the

core countries shown in Figure 6 is probably due to increasing global

inequality of development.

What we need to do in order to examine relative

trajectories of the core countries is to calculate the country ratios to the

average GDP per capita of the core group. These calculations will be reported

in the next revised version of this paper.

Maddison’s (1995, 2001) new estimates are not the best

possible measures of relative economic power of core countries, as discussed

above. But they do make it possible to make some long run and large-scale

quantitative comparisons, and the results of have implications for future

research on the problem of hegemony. It should be noted that the hegemonic

rises of the Dutch, British and United States constitute a continuation of the

phenomenon of semiperipheral development in which a formerly semiperipheral

society transforms institutional structures and ascends to the top of a

world-system. All of the hegemons were former semiperipheral countries before

the rose to hegemony.

Abu-Lughod, Janet 1989 Before

European Hegemony. New York: Oxford University Press

Agnew, John A. 1987 The

United States in the World Economy: A Regional Geography. Cambridge:

Cambridge

University Press.

________ 2001 “The new

global economy: time-space compression, geopolitics and global uneven

development.” Journal of World-Systems Research 7,2: 133-154.

Anderson, David G. 1994 The

Savannah River Chiefdoms: Political Change in the Late Prehistoric

Southeast. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The

Long Twentieth Century. New York: Verso

Arrighi, Giovanni and

Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos and Governance. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

_______ 2002 "The Autumn of World Hegemonies: Three Belles Époques Compared."

Paper presented at the annual spring Political Economy of World-Systems

conference, University of California, Riverside, May 3-4.

Bairoch, Paul and Richard Kozul-Wright

1998“Globalization myths: some historical reflections on integration,

industrialization and growth in the world economy,” pp.37-68 in Richard

Kozul-Wright and Robert Rowthorn (eds.) Transnational

Corporations and the Global Economy. London: MacMillan

Bergesen, Albert 1996 "The Art of Hegemony."

Pp. 259-278 in Sing Chew and Robert

Denmark

(eds.), The Development of Underdevelopment: Essays in Honor of André

Gunder

Frank. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage,

1996.

Bergesen, Albert J. and John Sonnett, "The

Global 500: Mapping the World Economy

at

Century's

End." American Behavioral

Scientist Vol. 44, No. 10 (June 2001): 1602-1615.

Bornschier, Volker and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 1998 The Future of Global Conflict. London:

Sage.

Boswell, Terry 2002 "Hegemonic decline and World

Revolution: When the world is up for grabs" Paper presented at the annual

spring Political Economy of World-Systems conference, University of California,

Riverside, May 3-4.

Boswell, Terry and Albert

Bergesen (eds.) 1987 America’s Changing Role in the World-System.

New

York: Praeger.

Boswell, Terry and Mike

Sweat. 1991. "Hegemony, Long Waves and Major Wars: A Time

Series Analysis of Systemic Dynamics, 1496-1967." International

Studies Quarterly. 35, 2:

123-150.

Boswell, Terry and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral of Capitalism and

Socialism:

Toward Global Democracy. Boulder,

CO.: Lynne Rienner.

Calleo,

David, Beyond American Hegemony: The Future of the Western Alliance, New

York: Basic

Books, A Twentieth Century Fund Book, 1987.

Camilleri,

Joseph A., Kamal Malhotra and Majid Tehranian 2000 Reimagining the Future:

Towards Democratic Governance. Bundoora, Australia: Department of Politics,

LaTrobe

University.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher 1998

Global Formation: Structures of the World-Economy. Lanham,

MD.:

Rowman and Littlefield.

__________ 2001 “Globalization: a world-systems

perspective,” Protosociology

15:26-50.

__________ and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and

Demise: Comparing World-Systems. Boulder, CO: Westview

__________ and Susan Manning, 2002 "City

systems and world-systems: four millennia of city growth and decline," Cross-Cultural

Research 36,4 (November) http://www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/papers/isq01/isq01.htm

___________ and Bruce

Podobnik 1995 “The Next World War: World-System Cycles and Trends” Journal of World-Systems Research 1, 6

http://csf.colorado.edu/jwsr/archive/vol1/v1_n6.htm

___________, Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000

“Trade globalization since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system.” American Sociological Review, February.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Thomas E. Reifer 2002 “U.S.

hegemony and biotechnology,”

Presented at the ISA Research Committee on Environment and

Society RC24, XV

ISA

World Congress of Sociology, Brisbane, Australia, July 7-13.

Collins, Randall 1999 Macrohistory.

Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Dehio,

Ludwig, The Precarious Balance: Four Centuries of the European Power Struggle,

New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 1962.

Frank, Andre Gunder 1998 Reorient:

Global Economy in the Asian Age. Berkeley: University of

California

Press.

Friedman, Edward (ed.) Ascent

and Decline in the World-System. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Friedman, Jonathan 1994 Cultural

Identity and Global Process. London: Sage.

____________1983 “The

limits of an analogy: hegemonic decline in Great Britain and

the United States.” Pp. 143-54 in Albert

Bergesen (ed.) Crises and the World-System.

Beverly

Hills: Sage.

Goldstein, Joshua 1988 Long

Cycles: Prosperity and War in the Modern Age. New Haven: Yale

University

Press.

Gordon, David M. 1980 “Stages

of accumulation and long economic cycles.”

Pp. 9-45 in

Terence

K. Hopkins and Immanuel Wallerstein (eds.) Processes of the World-System.

Beverly

Hills: Sage.

Hamashita, Takeshi 1988

"The Tribute Trade System and Modern Asia," The Memoirs of the

Toyo Bunko, 46: 7-25.

Hardt, Michael, and

Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University

Press.

Hart, Jeffrey A. 1992 Rival

Capitalists: International Competitiveness in the United States, Japan and

Western

Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University

Press.

Held, David, Anthony McGrew, David Goldblatt and

Jonathan Perraton 1999 Global

Transformations: Politics, Economic and

Culture. Palo Alto, CA.: Stanford University Press.

Hobsbawm, Eric 1968 Industry

and Empire. Baltimore: Penguin.

Hopkins, Terence K. and

Immanuel Wallerstein 1979 “Cyclical rhythms and secular trends

of

the capitalism world-economy.” Review 2,4:483-500.

Huntington, Samuel 1996 The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, New

York:

Simon & Schuster.

Junne, Gerd 1999 “Global

cooperation or rival trade blocs?” in Volker Bornschier and Christopher

Chase-Dunn (eds.) The Future of Global

Conflict. London: Sage.

Kennedy, Paul, 1980 The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914, London: Ashfield

Press.

__________ 1987 The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, New York: Vintage Books.

Kentor, Jeffrey. 2000. Capital and Coercion: The Economic and Military Processes That Have

Shaped the World Economy 1800-1990. New York: Garland Publishing.

_________ 2002 "Conduits of Power:

Transnational Corporate Networks and Hegemony" Paper presented at the

annual spring Political Economy of World-Systems conference, University of

California, Riverside, May 3-4.

Kowalewski, David. 1997. Global Establishment: The Political Economy of North/Asian Networks.

New York. Macmillan Press.

Maddison, Angus 1995 Monitoring

the World Economy, 1820-1992. Paris: Organization for

Economic

Cooperation and Development.

_________ 2001 The

World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. Paris: Organization of Economic

Cooperation

and Development

Mandel, Ernest 1980 Long

Waves of Capitalist Development: the Marxist interpretation. London:

Cambridge

University Press.

Mann, Michael 1993 The

Sources of Social Power, Vol. 2.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

McCormick, Thomas J. 1989 America’s Half Century: United

States Foreign Policy in the Cold War.

Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press.

McNeill, William H., The Pursuit of Power:

Technology, Armed Force, and Society Since A.D. 1000, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Misra, Joya and Terry

Boswell 1997 “Dutch hegemony: global leadership during the age of

mercantilism”

Acta Politica: International Journal of Political Science 32:174-209.

Modelski, George and

William R. Thompson 1996 Leading Sectors and World Powers: the

Coevolution

of Global Economics and Politics. Columbia: University of South Carolina

Press.

Murphy, Craig 1994

International Organization and Industrial

Change: Global Governance since 1850. New York: Oxford.

O’Brien, Patrick K. 2002 “The Pax Britannica,

American hegemony and the international economic order, 1846-1914 and

1941-2001.” Paper presented at the annual spring Political Economy of

World-Systems conference, University of California, Riverside, May 3-4.

O’Rourke, Kevin H

and Jeffrey G. Williamson 1999 Globalization

and History: The Evolution of a 19th Century Atlantic Economy.

Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

World-System"

International Studies Quarterly,

31:239-272.

Polanyi, Karl 2001 [1944] The Great Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press.

Pomeranz, Kenneth 2000 The

Great Divergence. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Rasler, Karen and William

R. Thompson 1994 The Great Powers and Global Struggle,

1490-

1990. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

(ed.)

New Theoretical Directions for the 21st Century World-System New York:

Greenwood

Press.

_______

2002 “The phoenix cycle: global

leadership transition in a long-wave

perspective.” Paper

presented at the annual spring Political Economy of World-

Systems

conference, University of California, Riverside, May 3-4.

Reifer, Thomas E. 2002 “Globalization & the

National Security State Corporate Complex

(NSSCC) in the Long Twentieth

Century,” Greenwood Press, The

Modern/Colonial

Capitalist

World-System in the 20th Century, Ramon Grosfoguel and Margarita Rodriguez,

eds., Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Robinson, William I. 1996 Promoting Polyarchy: Globalization, U.S. Intervention and Hegemony,

Cambridge University Press.

__________1998 "Beyond Nation-State

Paradigms: Globalization, Sociology and

the Challenge of Transnational

Studies. Sociological Forum 13:561-594

Ross, Robert J.S. 1995 “The theory of global

capitalism: state theory and variants of capitalism on a world scale.” Pp. 19-36 in David Smith and Jozsef Borocz

(eds.) A New World Order?: Global Transformations in the Late Twentieth

Century. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Sassen, Saskia 2001 The Global City: New York,

London, Tokyo, Princeton: Princeton

University

Press Second revised edition.

Silver,

Beverly and E. Slater 1999. “The Social Origins of World Hegemonies”. In G.

Arrighi, et al. Chaos and Governance in

the Modern World System. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

151-216.

Sklair, Leslie. 2001. The Transnational Capitalist Class. Malden, MA: Blackwell

Publishers.

Su,

Tieting. 1995. "Changes in World Trade Networks: 1938, 1960, 1990" Review XVIII, 3:431-

459 (Summer)

Suter, Christian 1992 Debt Cycles in the World Economy: Foreign Loans, Financial Crises and

Debt Settlements, 1820-1987. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Taylor, Peter J. 1996 The

Way the Modern World Works: World Hegemony to World Impasse. New

York:

Wiley

Thompson, William R. 1992 "Dehio, long

cycles, and the geohistorical context of

structural transition," World Politics, Vol. 45,1:127-152.

__________. 2000a The

Emergence of the Global Political Economy. London, Routledge

__________ 2000b

“K-waves, leadership cycles and global war:…” Pp. 83-104 in Thomas

D.

Hall (ed.) A World-Systems Reader. Lanham, MD.: Rowman and Littlefield.

Van der Pijl, Kees. 1984. The Making of an Atlantic Ruling Class. London: Verso.

Wallerstein, Immanuel

1974 The Modern World-System, Volume 1. New York: Academic Press

__________1980 The

Modern World-System Volume 2. New York: Academic Press.

__________1984 ‘The three

instances of hegemony in the history of the capitalist

world-economy,”

Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and Research

in

Macrosociology, International

Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology, Vol.

37

Leiden: E,J. Brill.

________ 1989 The

Modern World-System Volume 3, New York: Academic Press.

_________ 2002a“The United

States in decline?” Paper presented at the annual spring Political Economy of

World-Systems conference, University of California, Riverside, May 3-4. Forthcoming

in Thomas E. Reifer (ed.) Hegemony, Globalization and Anti-Systemic

Movements. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

_________2002b

“The eagle has crash landed.” Foreign Policy (July-August) Pp. 60-68.

Waltz, Kenneth

N. 1979 Theory of International Politics. New York: McGraw-Hill

Wilkinson, David 1988

“Universal empires: pathos and engineering.” Comparative Civilizations

Review 18:22-44 (Spring).

__________ 1999 “Unipolarity without hegemony.” International

Studies Review. 2 :141-172. (Summer)