Global Indigenism and

the Web of

Transnational Social Movements

World Social Forum, Belem, Amazon Basin 2008

Christopher Chase-Dunn, James

Fenelon, Thomas D. Hall,

Ian Breckenridge-Jackson and Joel Herrera

For presentation at

Social Science History Association Panel: Globalization in Long Duree, Sponsor: Macro-Historical Dynamics Network, Saturday, November 08: 03:15 PM-05:15 PM

And to be presented at the

annual meeting of the California Sociological Association, Mission Inn,

Riverside, CA, Saturday, November 8, 2014, 1 pm, San Diego West, Session 16: Social

Movements, Organizer and Presider: Tim Kubal, CSU Fresno

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

Draft 11-3-14; 8613530

words

![]()

This is IROWS Working

Paper #87

available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows87/irows87.htm

Abstract: A global indigenous movement has emerged as a visible player in global civil society and in the New Global Left. Advocates of indigenous rights have participated in the Social Forum process at the global, national and local levels and have had an important influence on the emerging character of the contemporary world revolution.

We use surveys taken at a succession of Social Forum gatherings to examine how indigenous rights activists are similar to, or different from, the other attendees at these events and to investigate the links that indigenous rights activists have with other social movements. While our findings are far from definitive, they are strongly suggestive and point to a need to explore these findings in greater depth. We also note that the questionnaires were not constructed to address directly the issues we discuss here. We find that the number of attendees who assert that they are actively involved in the indigenous rights movement is more than five times greater than the number who identify themselves as indigenous when asked about their racial/ethnic identity. Indigenous activists are somewhat more radical on some political issues than those who are not indigenous activists, and they are more likely to argue that the community arena is the most important locus for solving the majority of contemporary problems. The indigenous rights movement is strongly connected by overlapping memberships with the human rights movement and is also quite strongly connected with the environmental and peace movements.

The indigenous rights movement has been an important element

of the New Global Left and the current world revolution since the Zapatista

rebellion in Southern Mexico against the neoliberal North American Free Trade

Agreement in 1994. Autonomists from

The World

Social Forum process has been an important venue for the formation of a New

Global Left since 2001 (Santos 2006; Reitan 2007; Smith et al. 2014).

The founding of the World Social Forum in 2001, a reaction to the exclusivity

of the World Economic Forum held in

The Transnational Social Movement

Research Working Group at the University of California-Riverside[1]

began conducting paper surveys of the attendees at Social Forum meetings at the

world-level meeting held in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 2005. Similar surveys were

mounted at the United States Social Forum held in

Indigeneity in the geoculture and in the New Global Left

Indigenous resistance and adaptation to expanding world-systems is a long and very old story. Small-scale societies have generally been decimated by larger, more hierarchical societies. The Guns, Germs and Steel (Diamond 1997) story is mainly a huge human tragedy with many prodigious struggles of resistance (e.g. Hamalainen 2008). But some of the peoples who formerly lived in autonomous small-scale societies have survived and adapted as they have become incorporated into both ancient and current world-system (Hall and Fenelon 2009; Perry 1992; Ferguson and Whitehead 1992) and they now play an important role in world politics (Wilmer 1993).

The very idea of a global indigenous movement is a contradiction in terms. Indigenous peoples usually stress the importance of their connections to particular places. But since the 1930s indigenous groups have been appealing to the United Nations (2007) for help in resisting culturicide[3] (Fenelon 1998; Wilmer 1993) especially over collective, indigenous rights. What has been different about transnational and global Indigenous organizations and movements is that are keenly aware how their problems are fundamentally local, yet broadly similar. The larger movements are characterized by an ethos that demands respect for each Indigenous group’s values, culture, and social practices.

Growing

awareness of Eurocentrism in politics, culture and

social science has combined with old notions about the other, civilization,

barbarism and savagery and imagined original “states of nature” in European

social thought.

The European Enlightenment itself legitimated cultural self-determination, though this value was most often ignored when colonized peoples were concerned. But it is important to note that the legitimate rights of indigenous peoples are not just a concern of the New Global Left. It is a globally recognized issue as documented in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007)The mainstream of the emerging global geoculture also includes an important element of respect for indigenous cultures (see Wallerstein 2011).

Indeed,

indigeneity is sometimes used to promote various projects that are connected

with neoliberal politics and capitalist profit-making. A case in point was

included in Deborah Hobden’s (2014) study of development projects in

Figure 1: Indigenous beads used to promote mall project in Ghana (Hobden 2014) Mobus Property Development. 2013. Meridian City [Brochure]. Accra, Ghana. http://www.meridiancity.com.gh/

In the New Global Left indigenous rights have been an

important element. The Zapatista rebellion of 1994 is an iconic event in the

emergence of the current world revolution.[5] Several

of the movement organizations that spun out of the Battle of Seattle in 1999

had connections with the Zapatistas and with umbrella indigenous organizations

in the

The Red

Road movement is a New Age spiritualism that embraces certain forms of

indigenous-inspired approaches that have emerged since the 1960s, mainly in the

The idea of “buen vivir” as a harmonious, community-oriented and nature-friendly alternative approach to the human future was first articulated in Latin America in connection with the Cochabamba encuentro on the rights of mother earth. Buen vivir has been incorporated into the Ecuadorian constitution and has been championed by many social movements participating in the social forum process (Conway 2012; Smith et al 2014).

Who

are the indigenous rights activists?

We used the survey responses from the four Social Forum meetings at which surveys were mounted to see how many attendees identified themselves as racially/ethnically[6] indigenous and how many saw themselves as either strongly identified with, or actively involved in, the indigenous rights movements. We also looked to see whether or not indigenous rights activists were similar to, or different from, other attendees regarding demographic characteristics and attitudes toward political issues.[7]

|

|

Porto Alegre 2005 |

Nairobi 2007 |

Atlanta 2007 |

Detroit 2010 |

All |

|

Racially/Ethnically

identified indigenous |

10 (1.8%) |

15 (3%) |

4 (0.7%) |

4 (0.8%) |

33 (1.5%) |

|

Strongly

identify with indigenous rights |

211 (37.5%) |

96 (19.5%) |

182 (32.3%) |

149 (28.8%) |

638 (29.9%) |

|

Actively

involved in indigenous rights |

48 (8.5%) |

35 (7.1%) |

66 (11.7%) |

27 (5.2%) |

176 (8.2%) |

|

Total Sample |

563 |

492 |

562 |

518 |

2135 |

Table 1: Indigeneity and activism at the Social Fora

Table 1 shows the numbers and percentages of those who

identified themselves as indigenous[8] at

each of the four venues and for the whole sample of attendees that includes the

sum of all the responses at all four venues. A number of important observations

are implied by the findings in Table 1. Each of the surveys included around 500

respondents, but we are not entirely sure how representative our samples were

of all the people who attended the Social Fora and so we are not sure how well

we can generalize to the whole group of attendees. Combining the results from

all of the surveys increases the number of respondents to 2135, which is useful

for this study because we are examining a group that is small minority among

the whole sample of attendees. There are difficulties involved in combining the

results from the different surveys because in some cases the wording of

questions was different (e.g. Footnote 8, and also because indigeneity does not

have a uniform global meaning. It very likely means something different in

The biggest finding in Table 1 is the large difference between the numbers and percentages of attendees who identify themselves as ethnically/racially indigenous and the number and percentages of those who say they strongly identify or are actively involved in the indigenous rights movement. Looking at the last column in Table 1 we see that only 33 out of a total of 2135 (1.5%) surveyed attendees identified themselves as racially/ethnically indigenous, but 638 (almost 30%) said they strongly identified with the indigenous rights movement and 176 (8.2%) claimed to be actively involved in indigenous rights movements. So only around one fifth of the attendees who say they are actively involved identify themselves as racially/ethnically indigenous. This shows that the indigenous rights movement is much larger than would be expected on the basis of the number of indigenous people who are participating in the Social Forum process. There is a very large number of sympathizers and a large number of activists who are not racially/ethnically indigenous. It is interesting to note that Idle No More explicitly calls for all people to join them in their visions statement (http://www.idlenomore.ca/vision). This is the main reason we have discussed the ideational role of indigeneity in global culture and in the New Global Left above. We note that indigenous movements are not monolithic and vary greatly in goals and objectives and socio-political relationships to the state.

Table 1

also contains a number of other interesting features. One is the large drop-off

from “strongly identify” to “actively involved” (rows

2 and 3 in Table 1). We have found this same large drop-off for all social

movement themes in all of our surveys (e.g. Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro 2009). It

is not unique to the indigenous rights movement. It means that attendees take

seriously the difference between sympathizing with a movement and actually

doing work for that movement. This is important for the topic at hand because

of the finding of the large number of non-indigenous, but actively involved, participants.

These are not just sympathizers. They are activists. Looking at differences

across the four venues we note that there were more ethnically/racially

identified indigenes at the world level meetings in

We also

note the decline in the percentages of strongly identified and actively

involved that occurred when we compare the

Table 2 shows the racial/ethnic composition of the indigenous rights sympathizers and activists compare with the racial/ethnic breakdown of the other Social Fora attendees.

|

Respondents

on “race or ethnicity” (see Footnote 4) |

|||||

|

|

Porto Alegre 2005 |

Nairobi 2007 |

Atlanta 2007 |

Detroit 2010 |

All* |

|

Actively

involved in indigenous rights |

|||||

|

White or Caucasian |

12 (26.7%) |

12 (37.5%) |

23 (35.9%) |

10 (43.5%) |

57 (34.8%)1 |

|

Black, African |

7 (15.6%) |

6 (18.8%) |

7 (10.9%) |

1 (4.3%) |

21 (12.8%) |

|

Latina/o |

4 (8.9%) |

2 (6.3%) |

7 (10.9%) |

4 (17.4%) |

17 (10.4%) |

|

Mixed or multi-ethnic/racial |

2 (4.4%) |

3 (9.4%) |

11 (17.2%) |

4 (17.4%) |

20 (12.7%)2 |

|

Arab/Arabic/Middle Eastern |

1 (2.2%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (1.6%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (1.2%) |

|

Asian |

3 (6.7%) |

4 (12.5%) |

5 (7.8%) |

2 (8.7%) |

14 (8.5%)3 |

|

Indigenous |

7 (15.6%) |

4 (12.5%) |

1 (1.6%) |

0 (0%) |

12 (7.3%) |

|

Other |

9 (20%) |

1 (3.1%) |

9 (14.1%) |

2 (8.7%) |

21 (12.8%)4 |

|

Total |

45 |

32 |

64 |

23 |

164 |

|

NOT

actively involved in indigenous rights |

|||||

|

White or Caucasian |

195 (44.4%) |

116 (31.1%) |

244 (52%) |

264 (58.5%) |

819 (47.3%)1 |

|

Black, African |

62 (14.1%) |

178 (47.7%) |

60 (12.8%) |

43 (9.5%) |

343 (19.8%) |

|

Latina/o |

27 (6.2%) |

11 (2.9%) |

73 (15.6%) |

64 (14.2%) |

175 (10.1%) |

|

Mixed or multi-ethnic/racial |

45 (10.3%) |

11 (2.9%) |

41 (8.7%) |

41 (9.1%) |

138 (8%)2 |

|

Arab/Arabic/Middle Eastern |

3 (0.7%) |

9 (2.4%) |

7 (1.5%) |

3 (0.7%) |

22 (1.3%) |

|

Asian |

23 (5.2%) |

31 (8.3%) |

14 (3%) |

20 (4.4%) |

88 (5.1%)3 |

|

Indigenous |

1 (0.2%) |

7 (1.9%) |

3 (0.6%) |

4 (0.9%) |

15 (0.9%) |

|

Other |

83 (18.9%) |

10 (2.7%) |

27 (5.8%) |

12 (2.7%) |

132 (7.6%)4 |

|

Total |

439 |

373 |

469 |

451 |

1732 |

|

Strongly

identify with indigenous rights |

|||||

|

White or Caucasian |

73 (39%) |

31 (34.8%) |

76 (43.7%) |

67 (50.4%) |

247 (42.4%) |

|

Black, African |

23 (12.3%) |

33 (37.1%) |

21 (12.1%) |

14 (10.5%) |

91 (15.6%) |

|

Latina/o |

18 (9.6%) |

4 (4.5%) |

24 (13.8%) |

21 (15.8%) |

67 (11.5%) |

|

Mixed or multi-ethnic/racial |

17 (9.1%) |

3 (3.4%) |

24 (13.8%) |

18 (13.5%) |

62 (10.6%) |

|

Arab/Arabic/Middle Eastern |

3 (1.6%) |

5 (5.6%) |

2 (1.1%) |

0 (0%) |

10 (1.7%) |

|

Asian |

11 (5.9%) |

7 (7.9%) |

8 (42.1%) |

8 (6%) |

34 (5.8%) |

|

Indigenous |

7 (3.7%) |

5 (5.6%) |

2 (1.1%) |

1 (0.8%) |

15 (2.6%) |

|

Other |

35 (18.7%) |

1 (1.1%) |

17 (9.8%) |

4 (3%) |

57 (9.8%) |

|

Total |

187 |

89 |

174 |

133 |

583 |

|

1Z-test, p-value = .002*** 2Z-test, p-value = .061 |

3Z-test, p-value = .061 4Z-test, p-value = .020* |

||||

|

*p < .05 (two-tail), ***p

< .01 (two-tail) |

|||||

Table 2: Racial/ethnic

composition of indigenous sympathizers and activists at the Social Fora

About 1/3 of the indigenous rights activists (actively involved) and 42% of the sympathizers (strongly identified) say they are racially/ethnically white. The percentage of attendees who are not involved with indigenous rights are about ½ white. So indigenous rights sympathizers and activists are less likely to be white than other attendees and this difference is statistically significant (see z-test in Table 2). They are also less likely to be black and this difference is also statistically significant. Latina/o and Arabic percentages are about the same. Indigenous rights activist’s racial/ethnic identity percentages are higher than others in the indigenous, mixed, Asian and “other” categories but for only the “other” category is the difference statistically significant.

Similarities and Differences between Indigenous Rights

Activists and other attendees at the Social Fora

The following tables compare, across

the four venues, actively involved indigenous rights activists with all other

attendees and with all other attendees who were also actively involved in at

least one of the other social movement themes. We include other “actively

involved” because some of our findings imply greater radicalism on the part of

the indigenous rights activists, but we want to know if this is related to the

focus on indigenism, or is just a feature of all those who are actively

involved. It is generally known from social movement research that higher

participation by individuals is related to greater concern and we suspect that

this may also be related to greater radicalism.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1Z-test, p-value = .05 |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2Z-test, p-value= .308 |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 3: Attitudes toward

capitalism

The results

show in Table 3 could mean that indigenous rights activists have a more radical

position on capitalism because 59% want to abolish it versus only 51% for all

other attendees.[10] But

when we compare the indigenous rights activists with other attendees who also

claim to be actively involved in another social movement theme, the difference

is smaller (55%) and it is not statistically significant. This means that

indeed indigenous rights activists have a somewhat less sanguine attitude

toward capitalism than other participants in the New Global Left, but it should

also be noted that over half of the attendees favored abolishing capitalism

except at the

We note that Hall and Fenelon (2008, 2009) among others argue that many indigenous movements are inherently anti-capitalist, even when not explicitly or even intentionally so motivated. Since many seek to preserve communal ownership, administration, and stewardship of resources (on the latter see Ross et al. 2011) they challenge fundamental, often unstated, assumptions of enlightenment discourse on trade and capitalism: that humans are inherently individualistic and that private property is assumed to be “natural.” Furthermore, but not as directly challenging to capitalist or neoliberal ideology, many Indigenous Peoples have kinships systems that differ significantly from those of the West, and many other state-based systems. Similarly, they have very different views of spirituality and what western discourse is wont to call “religion.” In these senses then, many movements of Indigenous Peoples challenge fundamental axioms of neoliberal capitalism. Alas, the surveys do not provide sufficient detail to tease out these nuances numerically.

|

In the long run, what do you think should be done about these existing global

institutions: The World

Bank: o Reform o

Abolish o Replace o Do Nothing |

||||

|

|

Nairobi 2007 |

Atlanta 2007 |

Detroit 2010 |

All |

|

Actively

involved in indigenous rights |

||||

|

Reform |

13 (39.4%) |

8 (13.8%) |

6 (25%) |

27 (23.5%) |

|

Replace |

9 (27.3%) |

15 (25.9%) |

5 (20.8%) |

29 (25.2%) |

|

Abolish |

11 (33.3%) |

34 (58.6%) |

13 (54.2%) |

58 (50.4%)1,2 |

|

Nothing |

0 (0%) |

1 (1.7%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (0.9%) |

|

Total |

3 |

58 |

24 |

115 |

|

NOT

actively involved in indigenous rights |

||||

|

Reform |

188 (54.2%) |

119 (26.9%) |

117 (26.4%) |

424 (34.4%) |

|

Replace |

63 (18.2%) |

93 (21%) |

88 (19.8%) |

244 (19.8%) |

|

Abolish |

80 (23.1%) |

218 (49.2%) |

226 (0.9%) |

524 (42.5%)1 |

|

Nothing |

16 (4.6%) |

13 (2.9%) |

13 (2.9%) |

42 (3.4%) |

|

Total |

347 |

443 |

444 |

1234 |

|

Actively

involved in any other movement |

||||

|

Reform |

131 (51.8%) |

92 (24.9%) |

99 (24.5%) |

322 (31.4%) |

|

Replace |

47 (18.6%) |

86 (23.3%) |

84 (20.8%) |

217 (21.2%) |

|

Abolish |

66 (26.1%) |

182 (49.3%) |

210 (52%) |

458 (44.6%)2 |

|

Nothing |

9 (3.6%) |

9 (2.4%) |

11 (2.7%) |

29 (2.8%) |

|

Total |

253 |

369 |

404 |

1026 |

|

1Z-test, p-value = .099 |

|

|

|

|

|

2Z-test, p-value= .238 |

|

|

|

|

Table 4: Attitudes toward the

World Bank

Table 4 shows the pattern of responses to a question about

global institutions, specifically the World Bank. The

in

Table 4). We also note that the percentage favoring abolition of the bank was significantly lower

at the Nairobi meeting than at the Atlanta and Detroit meetings.

|

Do you think it is a good or bad idea to

have a democratic world government? Check one. o Good idea, and it is possible o Good idea, but not possible o Bad idea, and it is possible o Bad idea, and not possible |

||||||

|

|

Porto Alegre 2005 |

Nairobi 2007 |

Atlanta 2007 |

Detroit 2010 |

All |

|

|

Actively involved in indigenous rights |

||||||

|

Good idea and possible |

16 (37.2%) |

11 (36.7%) |

22 (44.9%) |

11 (52.4%) |

60 (42%)1,2 |

|

|

Good idea, but not possible |

13 (30.2%) |

12 (40%) |

11 (22.4%) |

4 (19%) |

40 (28%) |

|

|

Bad idea |

14 (32.6%) |

7 (23.3%) |

16 (32.7%) |

6 (28.6%) |

43 (30%) |

|

|

Total |

43 |

30 |

49 |

21 |

143 |

|

|

NOT actively involved in indigenous rights |

||||||

|

Good idea and possible |

137 (28.6%) |

167 (44.3%) |

185 (45.2%) |

150 (36.3%) |

639 (38.1%)1 |

|

|

Good idea, but not possible |

189 (39.5) |

153 (40.6%) |

106 (25.9%) |

125 (30.3%) |

573 (34.1%) |

|

|

Bad idea |

153 (31.9%) |

57 (15.1%) |

118 (28.9%) |

138 (33.4%) |

466 (27.8%) |

|

|

Total |

479 |

377 |

409 |

413 |

1678 |

|

|

Actively involved in any other movement |

||||||

|

Good idea and possible |

108 (28.6%) |

119 (44.1%) |

149 (45.3%) |

141 (37.5%) |

517 (38.2%)2 |

|

|

Good idea, but not possible |

150 (39.7%) |

108 (40%) |

84 (25.5%) |

116 (30.9%) |

458 (33.9%) |

|

|

Bad idea |

120 (31.7%) |

43 (15.9%) |

96 (29.2%) |

119 (31.6%) |

378 (27.9%) |

|

|

Total |

378 |

270 |

329 |

376 |

1353 |

|

|

1Z-test, p-value = .358 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2Z-test, p-value= .379 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table

5: Attitudes toward democratic world government

The surveys

also asked Social Fora attendees about their attitude toward the idea of a

democratic world government. Table 5 shows that indigenous

rights activists may be more likely to think that a democratic global

government is a good idea and is possible than are those who are not involved

in indigenous rights and this is not related to active involvement in general.

But these differences are not statistically significant (see z-tests in Table

5). Indigenous rights activists also seem to be somewhat more likely to think

that a democratic world government is a bad idea. This is because of the

response in the middle, for which indigenous rights activists are less likely

than others to think that a democratic world government is a good idea, but not

possible than those who are not indigenous rights activists. Thus it seems that

indigenous rights activists disagree with one another in their attitudes toward

the desirability of a democratic world government.

These results might be interpreted

somewhat differently. As noted earlier, social organizational features –

communal control of resources, kinship and marriage systems, religious values,

etc. – among indigenous peoples are arguably further distant from the

Eurocentric approaches among most of the world. So for instance, non-indigenist

activists typically come from that tradition and see democracy as a general

good and general goal. Indigenous peoples have had a number of bad interactions

with democratic governments: witness,

This may be due to sharp

distinctions of indigenous activists and movement groups toward working with

the state and governmental organizations, or working against them, or in just

working altogether separate from them. Besides the aforementioned Zapatistas,

who ask for all Indigenous Peoples to decide for themselves outside state

interests, a most applicable example would be perspectives toward the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples (2007) passed by the United Nations (after thirty years of

struggle). Some indigenous movement leaders see this as great progress to be built

upon, while others see it as capitulation to state-system politics that will

only further reign in indigenous collective rights in opposition to neoliberal

and state capitalist interests.[12]

|

Out of the following, which level is most important for

solving the majority of contemporary problems? |

||||||

|

|

Porto Alegre 2005 |

Nairobi 2007 |

Atlanta 2007 |

Detroit 2010 |

All |

|

|

Actively involved in indigenous rights |

||||||

|

Communities/ sub-national |

30 (73.2%) |

14 (53.8%) |

34 (63%) |

19 (90.5%) |

97 (68.3%)1,2 |

|

|

Nation-states |

3 (7.3%) |

3 (11.5%) |

6 (11.1%) |

0 |

12 (8.5%) |

|

|

International/ global |

8 (19.5%) |

9 (34.6%) |

14 (25.9%) |

2 (9.5%) |

33 (23.2%) |

|

|

Total |

41 |

26 |

54 |

21 |

142 |

|

|

NOT actively involved in indigenous rights |

||||||

|

Communities/ sub-national |

245 (57.6%) |

169 (49%) |

230 (56%) |

326 (76.2%) |

970 (60.3%)1 |

|

|

Nation-states |

42 (9.9%) |

36 (10.4%) |

40 (9.7%) |

36 (8.4%) |

154 (9.6%) |

|

|

International/ global |

138 (32.5%) |

140 (40.6%) |

141 (34.3%) |

66 (15.4%) |

485 (30.1%) |

|

|

Total |

425 |

345 |

411 |

428 |

1609 |

|

|

Actively involved in any other movement |

||||||

|

Communities/ sub-national |

198 (59.1%) |

112 (46.3%) |

191 (56.3%) |

294 (76%) |

795 (61%)2 |

|

|

Nation-states |

31 (9.3%) |

27 (11.2%) |

32 (9.4%) |

35 (9%) |

125 (9.6%) |

|

|

International/ global |

106 (31.6%) |

103 (42.6%) |

116 (34.2%) |

58 (15%) |

383 (29.4%) |

|

|

Total |

335 |

242 |

339 |

387 |

1303 |

|

|

1Z-test, p-value = .060 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2Z-test, p-value= .089 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table

6: Best level for solving problems

The surveys

also asked about which level is most important for

solving the majority of contemporary problems: communities, nation-states, or

international/global. Sixty-eight percent of indigenous rights activists

indicated that the community level is most important and this percentage was

higher than for those not involved in indigenous rights and for those who were

actively involved in other movement themes. These first differences in

proportions are quite close to the .05 level of statistical significance

according to the z-test.

|

Do you consider yourself to be part of a

global social movement? o No o Yes |

||||

|

|

Nairobi 2007 |

Atlanta 2007 |

Detroit 2010 |

All |

|

Actively involved in indigenous rights |

||||

|

Yes |

30 (90.9%) |

61 (95.3%) |

22 (84.6%) |

113 (91.9%)1,2 |

|

No |

3 (9.1%) |

3 (4.7%) |

4 (15.4%) |

10 (8.1%) |

|

Total |

33 |

64 |

26 |

123 |

|

NOT actively involved in indigenous rights |

||||

|

Yes |

325 (86.2%) |

405 (86.4%) |

328 (73.7%) |

1058 (82%)1 |

|

No |

52 (13.8%) |

64 (13.6%) |

117 (26.3%) |

233 (18%) |

|

Total |

377 |

469 |

445 |

1291 |

|

Actively involved in any other movement |

||||

|

Yes |

247 (91.5%) |

352 (91.2%) |

308 (77.2%) |

907 (86%)2 |

|

No |

23 (8.5%) |

34 (8.8%) |

91 (22.8%) |

148 (14%) |

|

Total |

270 |

386 |

399 |

1055 |

|

1Z-test, p-value =

.005*** |

|

|

|

|

|

2Z-test, p-value= .069 |

|

|

|

|

Table

7: Are you part of a global social movement?

But the local focus indicated by the results in Table 6 is somewhat contradicted by the results in Table 7. The surveys asked attendees whether or not they think of themselves as involved in global social movement. Nine out of ten global indigenous rights activists said yes, and this was a higher percentage than those not involved in indigenous rights and than those that were actively involved in other movement themes. The first difference is highly statistically significant and the second is nearly so at the .05 level according the the z-tests reported in Table 7 (see earlier comments on significants of local issues for Indigenous Peoples).

The relationships that indigenous rights

activists have with other social movements

Social movement organizations may be integrated both informally and formally. Informally, they are connected by the voluntary choices of individual persons to be active participants in multiple movements. Such linkages enable learning and influence to pass among movement organizations, even when there may be limited official interaction or leadership coordination. At the formal level, organizations may provide legitimacy and support to one another, and strategically collaborate in joint action. The extent of formal cooperation among movements within “the movement of movements” both causes and reflects the informal connections. In the analysis below we assess the extent and pattern of informal linkages among social movement themes based on the responses we got from our four surveys of attendees at the four Social Fora meetings we studied.

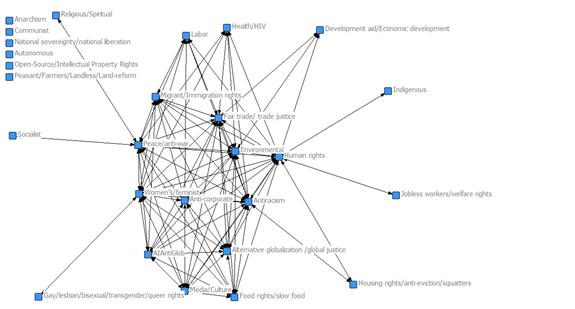

The

Table 8: Symmetrical

affiliation matrix of movement links: the number of affiliations based on

active involvement in 27 movement themes from the Social Fora surveys in

Nairobi, Atlanta and Detroit

Table 8 does not include the

The numbers in red in Table 8 show

the overlaps between indigenous activists and the other movement themes. The

movement theme with the least overlaps with indigenous rights activism is

communist (13). The movement theme with the largest number of overlaps is human

rights (88).

Figure 2: Movement links: the number of

affiliations based on active involvement in 27 movement themes from the Social

Fora surveys in Nairobi, Atlanta and Detroit

Figure 2 displays the network connections for the 27 movement themes using data from Nairobi, Atlanta and Detroit. In order to produce this figure it is necessary to dichotomize the distribution of affiliations shown in Table 8. We use the same cutting point that we have used in earlier studies of the network of movement ties, 1.5 standard deviations about the mean number of affiliations in Table 8. Using this cutting point results in a figure that indicates that Human Rights is the main contact point between indigenous rights and the other movements. This happens because indigenous rights is a relatively small movement theme and so when we use the mean of the whole distribution as the cutting point the ties that indigenism has with other movements are coded as zeroes. Only the tie with human rights is large enough to be 1.5 standard deviations above the mean. By this same criterion the six movement themes in the upper left corner have no connections with other movement themes that are large enough to show up in the diagram. This figure is good for showing the relative location of the largest and most central movement themes such as human rights, anti-racism, environmental, fair trade, and anti-corporate, but it is not very helpful for showing the nature of the connections between a small movement theme like indigenism with other movements.

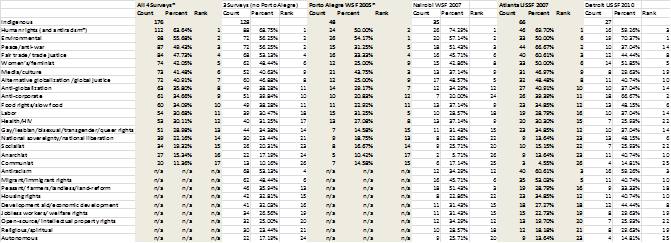

Table 9: Ego network of

Indigenous Overlaps

Table 9 uses the affiliation data that was in Table 8 but looks at it from the point of view of the indigenous rights movement theme, a so-called ego network approach, rather than from the point of view of the whole network. This allows us to see more clearly which other movement themes indigenism is strongly connected with and those with which it is only weakly connected. Table 9 also includes both the results when all four surveys are included (based on 18 movement themes) and the results when only the last three surveys are included (based on 27 movement themes). Table 9 also includes the indigenist overlaps for each of the surveys separately.

The first

at the second and third columns in Table 9 contain the results with and without

Table 9

also shows that the second biggest overlap of indigenism is with environmentalism.

This is not very surprising, but there is an interesting wrinkle. When we look

at the surveys separately environmentalism was first in

We should also discuss the other end of the spectrum, those movements that are little connected with indigenism. The Old Left movements (anarchism, communism, socialism) are in this group, but somewhat surprisingly so is autonomism despite the substantial support that European autonomists have voiced for Latin American indigenism (Lopez and Iglesias Turrion 2006). And though New Age spiritualism is often thought to be an important element in the Red Road movement, in the Social Forum context the religious/spiritual movement theme has little overlap with indigenism. This may be a wording problem, since indigenous belief systems have different labels: “spirituality” with positive connotation; “superstition” with a very negative connotation.

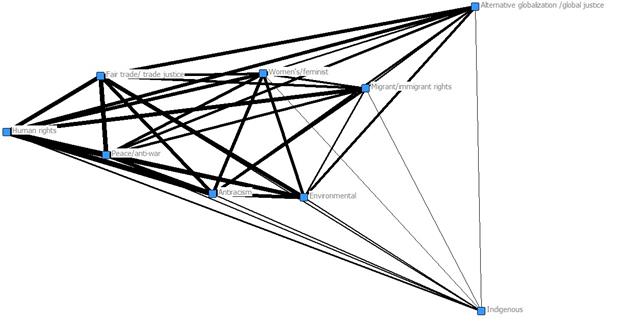

Figure 4: Indigenous Ego

Network, 3 Survey Dataset (27 movements – No Porto Alegre)

Figure 4 uses lines of different width to distinguish

between connections of different strength in the indigenous ego network. This

figure used the combined data from

Summary

Our main purpose is to investigate the nature of the current world revolution and ways in which indigenism is working within it. We have noted that indigenism as an ideology is far larger than the number of people who consider themselves to be indigenous in the New Global Left. This, in itself, is a significant finding. Indigenism has been an important element in the emergence of the New Global Left but it is also an important feature of the larger emerging global culture and is used frequently to sell commodities and to promote all kinds of projects. We have used the results of surveys conducted at Social Forum meetings to see how indigenous sympathizers and indigenous activists are similar to or different from other attendees. The Social Forum process is itself a project of the New Global Left, so we are mainly comparing indigenists with other progressive activists, not with the population of the world. [tdh1]We find that the numbers of both sympathizers and activists are far larger than the number of attendees who identify themselves as racially/ethnically indigenous. We also find that indigenous activists are both less white and less black than other attendees, and more likely to classify themselves as mixed or other. But 34% of indigenous activists classify themselves as White/Caucasian. We find that indigenous activists want to abolish capitalism and the World Bank more than other attendees, and this holds even in comparison with those who are actively involved in other social movement themes. But indigenous activists are not[tdh2] more radical in general (Table A5 in the Appendix). Indigenous activists are both more in favor of and more against a future democratic world government (Table 5), indicating that this issue is contentious among indigenous activists. Or may be a reflection of past experiences with “democratic” states. Indigenous activists see the local community as the most important for solving problems more than do other attendees (Table 6) but they also consider themselves to be part of a global movement to a greater extent than other attendees (Table 7).

Regarding the links that indigenistas have with other social movement themes as indicated by overlaps in which individuals claim active involvement with movements we find that indigenous rights movements are strongly connected with human rights, environmentalism, and anti-racism. The overlap with feminism is also strong and may be getting stronger.

Bibliography

*Beckett, Jeremy 1996. "Contested images: Perspectives on the indigenous terrain in the late 20th century." Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, Pp. 1-13

Borgatti, S. P. and

Everett, M. G. and Freeman, L. C. 2002 UCINET

6 For Windows:

Software for Social Network Analysis http://www.analytictech.com.

Casas, Tanya. 2014 “Transcending the Coloniality of Development: Moving Beyond Human/Nature Hierarchies” American Behavioral Scientist Vol. 58, No.1Chase-Dunn, C. and R.E. Niemeyer. 2009. “The world revolution of 20xx” Pp. 35-57 in

Mathias Albert, Gesa

Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational Political Spaces.

Campus Verlag:

Chase-Dunn, C. and Matheu Kaneshiro. 2009 “Stability and

Change in the contours of Alliances Among movements in the social forum

process.” Pp. 119-133 in David Fasenfest (ed.) Engaging Social Justice.

Coates, Ken S. 2004. A Global History of Indigenous Peoples:

Struggle and Survival.

Cobo, José Martinez. 1986. “Who are the Indigenous Peoples? A Working Definition.” International Working Group for Indigenous Affairs, on line at: http://www.iwgia.org/sw310.asp [accessed March 1, 2006].

Conway, Janet M 2012 Edges of Global Justice : The World Social Forum

and Its

'Others' London: Routledge.

Coyne, Gary, et

al. 2010. 2010

data at IROWS: http://www.irows.ucr.edu/research/tsmstudy.htm

Diamond, Jared. 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human

Societies.

Dunaway, Wilma A.

1996. The First American Frontier:

Transition to Capitalism in

_____. 1997. "Rethinking Cherokee Acculturation: Women's Resistance to Agrarian Capitalism and Cultural Change, 1800-1838." American Indian Culture and Research Journal 21:1:231-268.

_____. 2000.

"The International Fur Trade and Disempowerment of Cherokee Women,

1680-1775." Pp. 195-210 in World-Systems

Reader: New Perspectives on Gender, Urbanism, Cultures, Indigenous Peoples, and

Ecology, edited by Thomas D. Hall.

Fenelon, James V.

1998. Culturicide,

Resistance and Survival of the Lakota (“Sioux Nation”).

Fenelon, James V.

2012. “Indigenous Peoples, Globalization,and Autonomy

in World-Systems Analysis.” Pp. 304-312 in Routledge

Handbook of World-Systems Analysis edited by Salvatore J. Babones and

Christopher Chase-Dunn, 2012.

*Fischer, Edward

F. (ed) 2010 Indigenous Peoples, Civil Society and The

Hall, Thomas D. and James V. Fenelon. 2008. “Indigenous Movements and Globalization: What is Different? What is the Same?” Globalizations 5:1(March):1-11.

Hall, Thomas D. and James V. Fenelon. 2009. Indigenous Peoples and Globalization:

Resistance and Revitalization. Boulder ,

CO

Hall, Thomas D. and Joane Nagel. 2000. “Indigenous Peoples.”

Pp. 1295-1301 in The Encyclopedia of

Sociology, Vol. 2, revised edition, edited by Edgar F. Borgatta and Rhonda

J. V. Montgomery.

Hamalainen, Pekka

2008 The Comanche Empire.

Hodgson, Dorothy

L. 2002. “Precarious Alliances: The Cultural Politics and Structural

Predicaments of the Indigenous Rights Movement in

_____. 2011. Being Maasai, Becoming Indigenous:

Postcolonial Politics in a Neoliberal World.

Hull, Michael 2000 Sun Dancing: A Spiritual Journey on the Red Road. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International

Hobden, Deborah. 2014. "The Globalizers and the Globalized: Public and Private Sector

Development

Visions in 21st Century

Jaimes, M.

Annette with Halsey, Theresa. 1992. "American Indian Women: At the Center

of Indigenous

*Josephy, Alvin

M., Joane Nagel andTroy Johnson 1999 Red

Power: The American Indians’ Fight For

Freedom.

*Karides, Marina,

Walda Katz-Fishman, Rose M. Brewer, Jerome Scott and Alice Lovelace. 2010 The

López, Jesús Espasandín and Pablo Iglesias Turrión (eds.) 2006.

Lincoln, Kenneth.

1987 The Good Red Road: Passsages into

Native America.

*Maiguashca, Bice 1994 “The transnational indigenous movement in a changing world

order”. Global Transformation: Challenges to the State System. Yoshikazu

Sakamoto, ed, 356-382.New York United Nations University Press.

*Martin, William

G. et al, 2008 Making Waves: Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005.

McGaa, Ed 1992 Rainbow Tribe: Ordinary People Journeying on

the Red Road.

Meyer, John W.

2009 World Society.

*Nagel, Joane

1996 American Indian Ethnic Renewal: Red

Power and the Resurgence of Identity and Culture.

*Nabokov, Peter

2002 A

Osava,

Mario 1999 “World Social Forum: ‘Stateless Peoples’

Defend Diversity”

Interpress Service New Agency http://www.ipsnews.net/2009/02/world-social-forum-stateless-peoples-defend-diversity/

Perry, Richard J.

1996 From Time Immemorial: Indigenous Peoples and

State Systems.

Pickering,

Kathleen Ann. 2000. Lakota Culture, World

Economy.

Reese, Ellen, Mark Herkenrath, Chris Chase-Dunn, Rebecca Giem, Erika Guttierrez,

Linda Kim, and Christine Petit 2007 “North-South Contradictions and

Convergences at the World Social Forum” Rafael Reuveny and William R.

Thompson (eds.) Globalization, Conflict and Inequality: The Persisting

Divergence of the Global North and South. Blackwell.

Reese, Ellen,

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Kadambari Anantram, Gary Coyne, Matheu Kaneshiro,

Ashley N. Koda, Roy Kwon and Preeta Saxena 2008 “Research Note: Surveys of

World Social Forum participants show influence of place and base in the global

public sphere” Mobilization: An

International Journal. 13,4:431-445. Revised version in A Handbook of the World Social Forums,2012,

edited by Jackie Smith, Scott Byrd, Ellen Reeseand Elizabeth Smythe.

Reitan, Ruth.

2007. Global Activism.

Ross, Anne, Kathleen Pickering Sherman, Jeffrey G. Snodgrass, Henry

D. Delcore, and Richard Sherman. 2011. Indigenous Peoples and the Collaborative Stewardship of Nature:

Knowledge Binds and Institutional Conflicts.

*Smith, Jackie and Dawn Weist 2012 Social Movement in the World-System

Smith, Jackie, Marina

Karides, Marc Becker, Dorval Brunelle,

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Donatella della Porta, Rosalba Icaza Garza, Jeffrey S.

Juris, Lorenzo Mosca, Ellen

Reese, Peter Jay Smith and Rolando Vazquez 2014 Global Democracy and the World Social Forums.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and

Indigenous Peoples.

*Snipp, C.

Matthew 1989 American Indians: The First

of This Land.

Snow, David A. and Sarah A. Soule 2009 A Primer on Social Movements

Norton.

Snow, Dean R.

1996. The Iroquois.

*Steger, Manfred,

James Goodman and Erin K. Wilson 2013 Justice

Globalism: Ideology, Crises, Policy.

*Thornton,

Russell 1987 American Indian Holocaust

and Survival.

Tsosie, Rebecca.

2003. "Land, Culture and Community: Envisioning Native American Sovereignty

and National Identity in the Twenty-First Century. Pp. 3-20 in The

Future of Indigenous Peoples: Strategies for Survival and Development,

edited by Duane

United Nations.

2007. Declaration of the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples. United Nations General Assemply Resolution 61/295.

September 13, 2007. (Available on line in several languages).

*Wallerstein, Immanuel 1990 “Antisystemic

movements: history and dilemmas” in Transforming

the Revolution edited by Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi,

Andre Gunder Frank and Immanuel

Wallerstein.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2011. “Structural Crisis in the World-System: Where Do We Go from Here?” Monthly Review 62:10(March):31-39.

_____ 2012 The

Modern World-System, Volume 4 “The triumph of centrist liberalism”

Ward, Carol, Elon Stander, and Yodit Solom. 2000.

"Resistance through Healing among American Indian Women." Pp. 211-236

in A World-Systems Reader: New

Perspectives on Gender, Urbanism, Cultures, Indigenous Peoples, and Ecology,

edited by Thomas D. Hall.

Wilmer, Franke 1993 The

Indigenous Voice in World Politics,

Zald, Mayer N and John D. McCarthy 1987 “Social movement

industries: competition and conflict” Pp. 161-184 in

Mayer N. Zald and John D. McCarthy (eds.) Social Movements in

and Organizational Society.