US Hegemony and Biotechnology:

The geopolitics of new lead technology

Christopher

Chase-Dunn

Thomas Reifer

Institute for Research on World-Systems

Working Paper # 9

University

of California, Riverside

Abstract:

The three hegemonies of the modern world-system have been

the Dutch in the seventeenth century, the British in the nineteenth century and

the hegemony of the United States in the twentieth century. Sociologists and

political scientists have carefully studied the process of hegemonic rise and

decline.Recent research by Rennstich (2001) retools Arrighi’s (1994)

formulation of the organizational evolutions that have accompanied the

emergence of larger and larger hegemons over the last six centuries. Modelski and

Thompson (1996) argued that the British successfully managed to enjoy two

“power cycles,” one in the eighteenth and another in the nineteenth centuries.

With this precedent in mind Rennstich considers the possibility that the US

might succeed itself in the twenty-first century. Rennstich’s analysis of the

organizational, cultural and political requisites of the contemporary new lead

industries – information technology and biotechnology – imply that the United

States has a large comparative advantage that will most probably lead to

another round of U.S. pre-eminence in the world-system. But important

resistance to genetically engineered products has arisen as consumers and

environmentalists worry about the unintended consequences of introducing

radically new organisms into the biosphere. This paper will examine the

agricultural biotechnology industry as a new lead industry and will consider

its possible future impact on the distribution of power in the world-system.

This will entail an examination of the loci and timing of private and publicly

funded research and development, biotechnology firms that are developing and

selling products, and the emergence of national and global policies that are

intended to regulate and test genetically engineered products. The recent

history of environmental impacts of genetically engineered products will be

reviewed, as well as the contentious literature about the supposed risks of

agricultural biotechnology. Several scenarios regarding the timing of the onset

of biotech profitability and their potential impact on US economic centrality

will be developed, and data on both the business history and the emergence of

resistance will be employed to examine the likelihood of these possible

scenarios.

(v. 6-26-02) 4026 words

To be presented at the ISA Research

Committee on Environment and Society RC24 XV ISA World Congress of Sociology, Brisbane,

Australia, July 7-13, 2002. Session 8. New technologies and the environment:

ICT and biotechnology, organized by Elim Papadakis and Ray Murphy. An

earlier version was presented at the Division of Social Science Seminar, Hong

Kong University of Science and Technology, November 15, 2001.

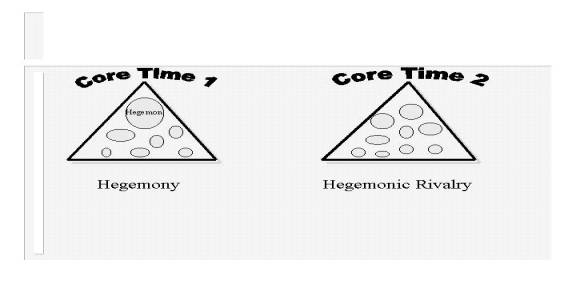

The

hegemonic sequence alternates between two structural situations as hegemonic

core powers rise and fall: hegemony and hegemonic rivalry.

Figure 1:

Unicentric vs. Multicentric Core

The

three hegemonies of the modern world-system have been the Dutch in the 17th

century, the British in the nineteenth century and the hegemony of the United

States in the twentieth century. Sociologists and political scientists have

studied the process of hegemonic rise and decline mainly by periodizing

hypothesized stages. Exceptions are Modelski and Thompson’s (1988) study of the

distribution of naval power capacity since the fifteenth century, and Modelski

and Thompson’s (1994) quantification of the rise of new lead industries. [1]

Recent

research by Rennstich (2001) retools Arrighi’s (1994) formulation of the

reorganizations of the institutional structures that connect finance capital

with states to facilitate the emergence of larger and larger hegemons over the

last six centuries. Modelski and Thompson (1996) argued that the British

successfully managed to enjoy two “power cycles,”[1]

one in the eighteenth and another in the nineteenth century. With this

precedent in mind Rennstich considers the possibility that the U.S. might

succeed itself in the twenty-first century. Rennstich’s analysis of the

organizational, cultural and political requisites of the contemporary new lead

industries – information technology and biotechnology – imply that the United

States has a large comparative advantage that will most probably lead to

another round of U.S. pre-eminence in the world-system.

This

paper will propose a research strategy for the examination of the biotechnology

industry as a new lead industry and will consider its likely future impact

on the distribution of power in the world-system.

Our

research focuses upon the geopolitical aspects and consequences of the

agricultural biotechnology industry. How will this industry affect the global

distribution of economic and military power in the next decades? Will it be a

big success economically and help to facilitate another round of United States

economic hegemony, or will it be a bust and so contribute to U.S. economic

decline relative to competing world regions and states. This question comes out

of research on the role of "new lead industries” in hegemonic rise and

decline.

Our

research will time-map the world-wide loci and timing of:

·

Medical and

agricultural biotechnology research and development,

·

Medical and

agricultural biotechnology firms that are developing products, and

·

national and global

policies that are intended to regulate and test genetically engineered

products, and to regulate medical biotechnology research and development.

The recent history of environmental impacts of genetically engineered products will be studied, as well as the contentious literature about the supposed risks of agricultural biotechnology. Several scenarios regarding the timing of the onset of biotech profitability and potential impacts on U.S. economic centrality will be modeled. Data on biotech business history and resistance to genetically modified foods and food inputs will be employed to examine the likelihood of these scenarios.

New

lead industries typically follow a growth curve in which a period of innovation

and relatively slow growth is followed by a period of implementation and

adaptation and rapid growth as the technologies spread, which is later followed

by a period of saturation in which growth slows down. The logistic or S-curve

is the hypothetical form, which is only approximated in the actual records of

new lead industries in economic history. Figure 2 illustrates the important

differences in the form of the growth curves of fourteen new lead industries in

world economic history since the fourteenth century as calculated by Michael A.

Alexander (2000).

Figure 2: New Lead Industries in the World-System

Source: Alexander (2000), P. 141.

In

about 1992 the U.S. share began again to increase, while the East Asian crisis

led the Japanese share to decline. Some observers have attributed this to a

reemergence of U.S. economic hegemony based on successes in information

technology. Rennstich contends that the United States has cultural and social

advantages over Europe and Japan that enable its workers to adapt quickly to

technological changes and that these, combined with the huge size of the U.S.

domestic market, will serve as the basis for a new “power cycle” of U.S.

concentration of economic comparative advantage based on information and

biotechnology.

Figure 3:Core

State's Shares of World GDP, 1950-1994

The reversal of the downward trend of the U.S.

share of the world economy in Figure 3 is also contemporaneous with a huge

reversal in the U.S. balance of payments. A huge inflow of foreign investment

in bonds, stocks and property beginning in the early 1990s turned the U.S. into

one of the world’s most indebted national economies and was arguably an

important contributor to the high growth rates and incredibly long stock market

boom of the 1990s. The dot.com stock bubble that burst in 2000 was a typical

example of how financial speculation can create profits by means of selling

stocks rather than be selling products that people buy and use. In such an

economy the stocks themselves become the product.

The “new economy speak” of the last decade was

typical of periods of financial speculation in which hypothetical future

earnings streams are alleged to be represented in the value of securities. But

the stock market operates according to a middle-run time horizon. Profits need

to be made within the next few years. Investments that do not pay a return

sooner than a decade hence are nearly valueless in conventional financial

calculations. This is why basic science is considered a public good that is

usually financed by governments. It is not usually reasonable to expect a financial

return soon enough for private investors, even venture capitalists, to assume

the necessary risks.

Biotechnology has been heralded as the potential

basis for a new round of U.S. economic hegemony. In this discussion we will

need to use a distinction between medical biotechnology and agricultural

biotechnology because of the somewhat different ways in which these branches of

the application of applied biology are related to factors that may influence

the economic potential of these technologies. Agricultural biotechnology is the

application of genomics to create new crops, new sources of animal protein, and

to protect crops and domesticated animals from pests. Agricultural

biotechnology is intended to improve the human food supply by lowering the

costs of production and by improving the products. Medical biotechnology is

intended to improve human health by developing new techniques for preventing

diseases, curing ailments, producing products for transplants and improving the

genetic makeup of individuals.

An

important literature has emerged that discusses the ethical dimensions and

political implications of biotechnology (e.g. Shiva 1997; Rifkin 1998) .

Extremely fundamental issues are becoming important in public discourse, and

the governance of biotechnology research and applications will be an

increasingly central part of politics in the twenty-first century (e.g.

Fukuyama 2002). In this paper we will discuss the politics of biotechnology

only insofar as it is likely to be an important influence on the potential role

of biotechnology as a new lead industry that might function as the basis of a

new round of U.S. economic hegemony.

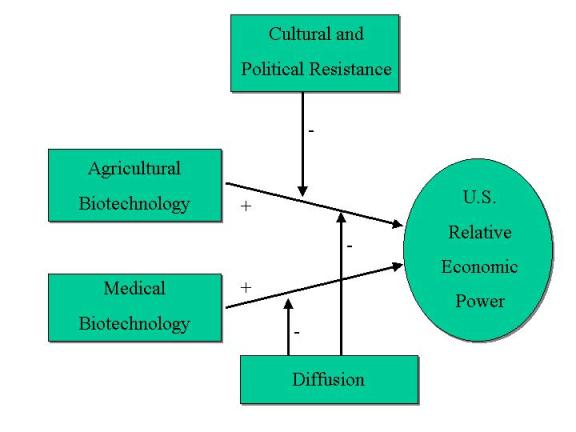

Figure 4:Diffusion and

Resistance Lower the Impact of Biotechnology on U.S. Economic Comparative

Advantage

Complete testing this model is impossible because

we have no information about the future. But we can quantify trends in recent

decades and see how they seem to interact temporally and spatially with one

another. The unit of analysis for this research is the world-system as a whole,

especially those countries and transnational networks that are engaging in

medical and agricultural biotechnology research and product development, but

also important potential markets for the biotechnology products. These latter

will include studies of public opinion regarding genetically modified organisms

and public policies regarding research, product testing and regulation of the

biotech industry. Large retailers of food products have been noticeably

important players in the drama of resistance to transgenic foods, and so they

need to be studied as well.

Arrighi,

Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth Century London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos and

Governance in the Modern World-System: Comparing Hegemonic

Transitions.

Minneapolis: University ofMinnesota Press.

Baark, Erik and Andrew Jamison

1990 “Biotechnology and culture: the impact of public debates on

government

regulation in the United States and Denemark.” Technology in Society

12:27-44.

Bello,

Walden 2001 The Future in the Balance: Essays on Globalization and

Resistance. Oakland, CA: Food First Books.

Bergesen,

Albert and John Sonnett 2001 “The Global 500: mapping the world economy at

century’s end” American

Behavioral Scientist 44,10:1602-1615.

Bonanno, Alessandro Lawrence

Busch, William Friedland, Lourdes Gouveia and Enzo Mingione (eds.) From

Columbus

to Conagra: the Globalization of Agriculture and Food.

Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Bornschier,

Volker and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.)2000 The Future of Global Conflict.

London: Sage

Boswell, Terry andMike

Sweat 1991 “Hegemony, long waves and major wars: a time series analysis of

systemic

dynamics, 1496-1967” International Studies Quarterly 35,2: 123-150.

Busch, Lawrence, W.B. Lacy, J.

Burkhardt, D. Hemken, J. Moraga-Rojel, T. Koponen and J. de Souza Silva

1995 Making

Nature, Shaping Culture. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Casper, Steven and Hannah

Kettler 2001 “National institutional frameworks and the hybridization of

entrepreneurial

business models: the German and UK biotechnology sectors.” Industry and

Innovation

8,1:5-30

(April).

Chase-Dunn, Christopher 1998 Global Formation:

Structures of the World-Economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman and

Littlefield.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Thomas

Reifer, Andrew Jorgenson, Rebecca Giem, John Rogers and Shoon Lio

2002 “ The trajectory of the

United States in the World-System: a quantitative reflection.” presented

at the XV ISA World Congress of Sociology, Brisbane,

Australia, Wednesday, July 10, 2002, 1:30-5:30pm Sessions on “American Primacy or American Hegemony?”

Far Easter Economic Review June

14, 2001 “Saying no to transgenic crops”

Fukuyama, Francis 2002 Our

Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. New York:

Farrar, Straus

and

Giroux.

Goodman, David and Michael J.

Watts (eds.) Globalising Food: Agrarian Questions and Global Restructuring.

London:

Routledge.

Henwood, Doug 1998 Wall

Street. New York: Verso.

Kharbanda, V.P. and Ashok Jain

1999 Science and Technology Strategies for Development In India and China.

Har-

Anand.

Kloppenburg, Jack R. 1988a First

the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology 1492-2000.Cambridge:

Cambridge

University Press.

Kloppenburg, Jack R. (ed.)

1988b Seeds and Sovereignty: The Use and Control of Plant Genetic Resources.

Durham:

Duke

University Press.

McKelvey, Maureen 2000 Evolutionary

Innovations: the Business of Biotechnology.New York: Oxford University

Press.

McMichael, Phillip 1993

“Agro-Food restructuring in the Pacific Rim: A comparative international

perspective

on

Japan, South Korea, the United States, Australia and Thailand.” In Ravi Palat

(ed.) Pacific-Asia and

the

Future of the World-System. Westport: Greenwood.

_____________ (ed.) 1994 The

Global Restructuring of Agro-Food Systems. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

_____________ 2000 Development

and Social Change: A Global Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA.: Pine Forge

Press.

_____________ 2001 “The impact

of globalisation, free trade and technology on food and nutrition in the

new

millennium,” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 60:215-220.

Modelski, George and William R.

Thompson 1996 Leading Sectors and World Politics. Columbia, S.C.:

University

of South Carolina Press

National Research Council 2000 Genetically

Modified Pest-Protected Plants: Science and Regulation.Washington, DC:

National

Academy Press.

Owen, Geoffrey 2001

“Entrepreneurship in UK biotechnology: the role of public policy.” Working

Paper #

14. The

Diebold Institute Entrepreneurship and Public Policy Project.

Pistorius, Robin and Jeroen van

Wijk 1999 The Exploitation of Plant Genetic Information: Political

Strategies in Crop

Development. New

York: CABI.

Rennstich, Joachim K. 2001 “The Future of Great Power

Rivalries.” In Wilma Dunaway (ed.) New Theoretical

Directions for the 21st Century

World-System New York: Greenwood Press.

_______ 2002 “The phoenix

cycle:global leadership transition in a long-wave perspective.” Paper presented at

the annual spring Political Economy of World-Systems

conference, University of California,

Riverside, May 3-4.

Rifkin, Jeremy 1998The Biotech Century. New York:

Penguin Putnam.

Sassen,

Saskia, 2001 The Global City:New York, London, Tokyo, Second revised

edition, Princeton:

Princeton University Press

Shiva, Vandana 1997 Biopiracy: the Plunder of Nature

and Knowledge. Boston, MA: South End Press.

Suter, Christian 2002 “Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering: A New Technological Style or a New

Technology Controversy?” (unpublished paper).

Thompson, William R. 2000 The Emergence of the

International Political Economy. London: Routledge.

Vernon, Raymond 1966 “International investment and

international trade in the product cycle.” Quarterly

Journal of Economics 80:

190-207.

_________ 1971 Sovereignty at Bay: The Multinational

Spread of U.S. Enterprises. New York: Basic Books.

Yok-Shiu Lee and Alvin Y. So (editors). 1999 Asia's

Environmental Movements: Comparative Perspectives. Armonk:

M.E. Sharpe.

Zucker, Lynne G., Michael Darby and Yusheng Peng 1998 “

Fundamentals or population dynamics and the

geographic distribution of U.S.

biotechnology enterprises, 1976-1989” National Bureau of Economic

Research Working Paper 6414. www.nber.org/papers/w6414