the Ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian World-Systems Christopher Chase-Dunn,Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis AlvarezInstitute for Research on World-SystemsUniversity of California, Riversidechriscd@ucr.edu

Thomas D. Hall, Sociology,DePauw University

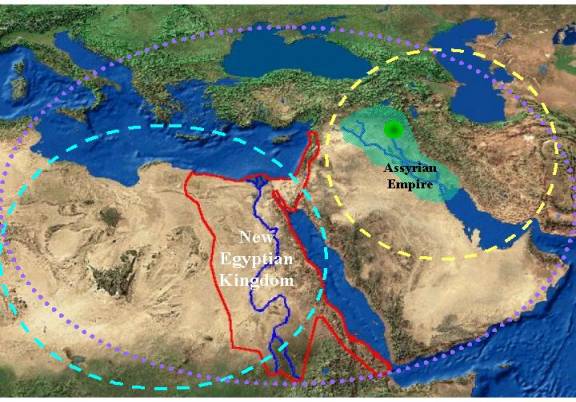

Northeast African and West Asian PMNs

An earlier

version was presented at the All-UC Multicampus Research Unit in World History

conference, UCLA December 6-7, 2003.

(10522 words) Thanks to Guillermo Algaze, Claudio Cioffi, Jerry Cooper

and Peter Peregrine for comments on an earlier version.

v. 12-8-03

Introduction

This

paper presents an overview of the development of complex and hierarchical

societies in ancient Southwestern Asia from a comparative world-systems

perspective, and presents an analysis of the timing of urban and empire

growth/decline cycles in Mesopotamia and Egypt to test the hypotheses that

these two regions may have experienced waves of development synchronously. We

also discuss how climate change may have influenced the patterns of

development. In a nutshell our argument

is that there have been systemic relations among different peoples since at

least the first human settlements by the Natufians some twelve thousand years

ago (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997). The developmental logic of these intersocietal

systems have changed over time as new techniques of power and institutions have

emerged but there are also broad continuities and similar patterns over

millennia as world-systems became larger.

This paper utilizes the conceptual apparatus of the comparative

world-systems perspective to examine the patterns of development in prehistoric

and ancient Western Asia. Thus we speak of strong core polities and weaker and

dependent peripheral societies, as well as societies in the middle, which we

call semiperipheral. And we bound systems by using interaction networks in

which important, two-way and regular interaction links peoples with different

cultures. This network approach to bounding world-system is explicated in

Chase-Dunn and Jorgenson (2003).

We

contend that some of the peoples who were semiperipheral in the ancient

world-systems were the main agents that brought about the transformations of

developmental logics. We also contend that the formation, differentiation, and

development of nomadic peoples in tandem with sedentary states and empires

played a crucial role. Nomads were

often the catalysts of systemic change in these early state-based world-systems.

This research paper builds on studies by David Wilkinson (2000), William R.

Thompson (2000. n.d.), and Guillermo Algaze (1993, 2000a, 2000b).

Karl

Butzer (1997) contends, with respect to Levantine development processes, that

the existence of cycles is prima facie evidence of some sort of

system. We have noted that all

world-systems large and small exhibit cycles of expansion and contraction of

trade networks, which we call pulsation. Furthermore, once chiefdoms emerge there is another cycle appears,

the rise and fall of large polities.

Following the work of David Wilkinson, we note that the Mesopotamian and Egyptian interstate systems merged around 1500 BCE to become a single larger system of states that we call the Central System. And about 1500 years earlier, around 3000 BCE, long-distance prestige good trade connected these two regions. As these mergers occurred it might be expected that growth/decline phases in the two regions would become synchronous. Indeed we have found an important instance of this kind of synchrony between East and West Asia that emerged around 500 BCE and lasted until around 1500 CE (Chase-Dunn, Manning, and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and Manning).

One

area worthy of further examination is the effects of climate change on patters

of social development. Brian Fagan (1999) contends that it was sudden climate

changes and natural disasters that provoked humans to invent new forms of

social organization. Bill Thompson has argued (n.d.: Figure 1] that climate

change may affect social systems in complex, and at times contradictory,

ways.

Pulsation, Rise and Fall and Semiperipheral

Development in the Southwestern Asian System

In

this paper we mainly focus on Southwestern Asia and the Mediterranean Levant.

The time period under consideration is from the emergence of mesolithic

sedentism (about 10,000 BCE) to the point at which the growing Southwestern

Asian political/military network (PMN) became linked with the Egyptian PMN by

the Hyksos conquest of Egypt (about 1500 BCE).

We will examine the hypothesis of semiperipheral transformative action

in the context of a discussion of the processes of polity-formation,

technological change, the rise and fall of larger polities, the pulsation of

interaction networks and the transformation of the very logic of social

integration from kin-based normative regulation to state-based

institutionalized coercion. The

hypothesis of semiperipheral development asserts that semiperipheral regions

in core-periphery hierarchies are fertile sites for innovation and the

implementation of new institutions that sometimes allow societies in these

regions to be upwardly mobile and/or to transform the scale (and sometimes the

qualitative nature) of institutional structures. This is not simply the notion that core traits diffuse toward the

periphery. It is rather the idea that semiperipheral innovation enables upward

mobility and occasionally transforms whole systems. Semiperipheral actors have

taken different forms in different systems. Semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms

and semiperipheral marcher states conquer older core states to form a new

core-wide polity. Semiperipheral capitalist city-states exploit an opportunity

to accumulate wealth based on trade and the production of commodities. And in

the modern world-system it is semiperipheral nation states that have risen to

become the hegemonic within still multicentric cores. This notion is further

explicated in Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997: Chapter 5).

The

hypothesis of semiperipheral development presumes a cross-cultural

conceptualization of core/periphery hierarchies in which more powerful

societies importantly interact with less powerful ones. The idea of

core/periphery hierarchy was originally developed to describe and account for

the stratified relations of power and dependency among societies in the modern

world-system. The comparative world-systems approach developed by Chase-Dunn

and Hall (1997) distinguishes between core/periphery differentiation, in

which there is important interaction among societies that have different

degrees of population density, and core/periphery hierarchy in which

some societies are exercising domination or exploitation of other societies. It

is not assumed that all world-systems have core/periphery relations. Rather

this is turned into a research question to be determined in each case.

The 8500 year period from

10,000 BCE to 1500 BCE in Western Asia witnessed a series of fundamental

pristine transformations in the nature of human societies: the original

Mesolithic emergence sedentary diversified foraging (the first dwellers in

permanent villages), the Neolithic invention and application of farming, the

emergence of the first hierarchical chiefdoms, the first multi-tier settlement

systems, and eventually the first cities and states. The Southwest Asian

world-system developed the first relatively stable core/periphery hierarchy in

which imperial core states exploited and dominated peripheral peoples. This region also witnessed the first instance

of a core-wide empire resulting from the conquest of a set of older core states

– the Akkadian Empire. As will be seen, our earlier characterization of this as

an instance of a semiperipheral marcher state erecting a pristine empire

(Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: 84-89) needs to be modified in some important

respects.

What follows is an analytic

narrative about the development of social complexity and hierarchy in

prehistoric and ancient Southwestern Asia and the Levant. The rapid and

dramatic emergence of states, cities and writing in the West Asian system in

the fourth millennium BCE was built upon a set of prior developments that

spread from the adjacent Levant over the previous five thousand years. The

metaphor of ecological succession is relevant for understand the evolution of

world-systems. Small plants breaking down rocks create soil. This produces what

is necessary for larger plants and trees to grow. The analogue of soil is

socially produced surplus and the institutional structures that allow human

societies to become larger and more hierarchical. But as with ecological

succession, this is not a smooth upward accession from small to large.

Regressions and collapses were frequent, and the areas in which the first

break-throughs occurred are most usually not the same locations in which later,

larger-scale developments emerged. It was a process of temporally and spatially

uneven social development. The institutional soil first formed in the

prehistoric Levant and then spread to ancient Southwestern Asia.

The Hilly Flanks

The Mesolithic invention of

relatively permanent village life was made possible by a diversified foraging

strategy that mixed the gathering of vegetable resources, fishing and hunting

of small game. This developed in a context in which the villagers continued to

cooperate and compete with more nomadic hunter-gatherers. The Natufian culture

of the Levant is the earliest known example of Mesolithic sedentism based on

diversified foraging – this around 9000 BCE (Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 1991;

Moore 1982).[1]

Sedentary foragers probably invented territorial boundaries as well as a more

active intervention in the productive cycles of nature. In other regions

diversified foragers are know to have used fire to increase the growth of

food-producing plants and grazing areas attractive to game. These activities

have been termed "protoagriculture" (Bean and Lawton 1976). A similar

Mesolithic culture, dated to around 8650 BCE, has been found at Shanidar Cave

and village sites in the Zagros Mountains on a tributary of the Tigris (Solecki

and Solecki 1982).

In the smaller valleys in the

hills adjacent to the prime gathering regions of the Natufian peoples naturally

occurring stands of grain were less productive. It is plausible that when the nomads in these neighboring regions

tried to emulate the sedentary life-style of the mesolithic villagers, they

found those natural stands were quickly eaten up, and so they experimented with

planting the seeds that they had gathered. The proto-horticulture of the

diversified foragers may have been transformed into true horticulture and the

domestication of useful plants by the adjacent neighbors of the original

sedentary foragers (Hayden 1981). The further archaeological study of the

spread of diversified foraging and gardening will enable us to test this

hypothesis. It may be that the first instance of semiperipheral development was

the emergence of a new productive technology (planting) in a region adjacent to

one in which an earlier new departure had occurred (sedentism).

The techniques of gardening spread

both west into the valley of the Nile and east toward Mesopotamia. Gardening

increased the number of people that could be supported by a given area of land

making greater population density possible. Community sizes grew in

rain-watered regions and population growth led to the migration of farmers away

from the original heartland of gardening.

Horticultural techniques also diffused from group to group and were

combined with the domestication of pigs, sheep and goats. This was the

Neolithic “revolution.” Still-nomadic hunter-gatherers traded with the

Neolithic towns, and a new form of pastoral nomadism developed based on the

herding of domesticated animals

The simple model here is that

technological development increased population density and this facilitated the

emergence of social hierarchies. There is evidence from the Chesapeake region

of indigenous North America that migration of planters or in situ adoption of planting does not always immediately lead to

greater complexity and hierarchy (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1999). It appears that

the arrival of corn planting in the Chesapeake allowed the “mesolithic”

diversified foragers living in rather large villages to redisperse into widely

spread farmlets and to reduce the intensity of their trading and ritual

symbolization of group identity and social hierarchy. So technological change

can, under some conditions, lead to deconcentration and less social

hierarchy. This possibility needs to be

kept in mind as we examine the spread of gardening across Southwestern Asia.

As villages eventually grew

larger, trade networks did as well and craft specialists began producing for

export and importing raw materials.

Trade networks probably expanded and contracted along different spatial

dimensions, as was the case in other small-scale world-systems (Chase-Dunn and

Mann 1998). It is known that obsidian

(volcanic glass) was an important lithic material for the production of cutting

tools and weapons in regions adjacent to the Levant and Southwestern Asia

(Torrence 1986). Obsidian tools and debitage (waste materials that are

by-products of tool making) can be chemically fingerprinted so that the

original quarries can be identified. And obsidian hydration rinds can be used

as an indicator of the period in which the tool was formed. These techniques

can be used to indicate the patterns of obsidian trade and procurement networks

and how they changed over time. Similar

methods are also available for some other lithic materials. These techniques

have not been fully exploited for studying the emergence and pulsation of

trading networks in the prehistoric Levant and Southwestern Asia.

Some regions began displaying

mortuary practices that indicated the emergence of social stratification. In

Northern Mesopotamia a degree of hierarchy is evident in the Hassuna/Samarra

archaeological tradition from 6000 BCE to 5500 BCE. Precious minerals were traded over larger and larger regions, and

regionally defined pottery styles developed. The Halafian archaeological

tradition in Northern Mesopotamia (5500 BCE-5000 BCE) had quite large villages

and some have argued that these were chiefdoms.

To the Flood Plain

According to Nissen (1988:

Chapter 3) the first three-tiered settlement system in Southwest Asia emerged

on the Susiana Plain (in what is now Iran adjacent to the Mesopotamian flood

plain) in the Ubaid period (5500-4000 BCE).

This would indicate the presence of complex chiefdoms, and Wright (1986)

points to the importance of the existence of complex chiefdoms in a region as

the necessary organizational prerequisite for the emergence of pristine

states. In other words, first states do

not emerge directly from egalitarian societies. Evidence from Uqair, Eridu and

Ouelli shows that there were also Ubaid sites on the Lower Mesopotamian flood

plain that were as large as the sites on the Susiana Plain at this time. The

Early Ubaid phase at Tell Ouelli shows remarkably complex architecture as early

as anything on the Susiana Plain. Thus there was an interregional interaction

system of chiefdoms based on a mix of rain-watered and small-scale irrigated

agriculture.

In the next period (Uruk or Late Chalcolithic from 4000-3100

BCE) the first true city (Uruk) grew up

on the floodplain of lower Mesopotamia, and other cities of similar large size

soon emerged in adjacent locations.

Surrounding these unprecedented large cities were smaller towns and

villages that formed the first four-tiered settlement systems (Adams 1981).

This was the original birth of “civilization” understood as the combination of

irrigated agriculture, writing, cities and states.[2]

States also emerged somewhat later in the Uruk period on the Susiana Plain

(Wright 1998 and these also developed four-tiered settlement systems (Flannery

1998:17). This was an instance of uneven development -- the transition from an inter-regional interchiefdom system to

an inter-city-state system that emerged first in Mesopotamia and then spread to

the adjacent Susiana plain.

A System of States: the Temple and the Palace

The main architectural feature

of these new cities was the temple and this structure has long been considered

the primary institution of a theocratically organized political economy. Later evidence about Sumerian civilization

shows that each city was represented by a god in the Sumerian pantheon and the

priests and populace were defined as the slaves of the city god – this

justifying the accumulation of surplus product (Postgate 1992). Flannery (1998) claims that even the

earliest archaic states often also had palaces – residential buildings for the

war-leader king. But in Mesopotamia

most scholars think that palaces were a later development that emerged when

competitive warfare among the city-states for the control of land and trade

routes became more frequent. Congruent

with this is the evidence that shows an implosion of population from

surrounding towns and villages to live within the protected confines of walled

cities (Adams 1981). Thus was the early

“peer polity” or “early state module” (Renfrew 1986) of co-evolving

archaic states transformed into an intercity-state system of warring and

allying states.

This transition from theocracy

to the primacy of a warrior king was an important development in the emergence

of state-based modes of accumulation.

The Sumerian cities erected their states –specialized institutions of

regional control – over the tops of kin-based normative institutions (Zagarell

1986). Assemblies of lineage heads long continued to play an important role in

the politics of Mesopotamia. But the structures of institutional coercion

became ever more important for maintaining power and accumulating wealth. One

interesting apparent difference between the emergences of archaic states in

Mesopotamia from other instances of pristine state formation is the apparent absence

of ritual human sacrifice. A powerful

way to dramatize the power of a king is to bury a lot of other people with him

when he dies. Except for the EDIII period in the royal cemetery at Ur, there is

little evidence of human sacrifice in Mesopotamia. The temple economy required contributions of goods and labor

time, including animal sacrifices that were consumed in religious feasts. But the sacrifice of humans in Mesopotamia

was, as with modern states, mainly confined to killing in battle.

The story of the Uruk expansion

is well known, though its exact nature remains controversial (Algaze 1993,

2000; Stein 1999). The emerging cities

of Mesopotamia founded colonies and colonial enclaves within existing towns

across a vast region in order to gain access to desired goods and to control

trade routes (Algaze 1993; 2000). There

is some disagreement as to the degree of direct control that these core

city-states[3] were

able to exercise over distant peripheral regions.

Archaeologist Gil Stein’s (1999) confrontation of

world-systems ideas with evidence was inspired by the work of Phil Kohl (1987a,

1992). What Stein has done is to go beyond Kohl to formulate testable

alternative models of core/periphery relationships. His “distance-parity” model

is a major conceptual improvement over earlier work. And Stein’s careful

research at Hacinebe (on the Tigris in Turkey) has gone far to enlighten us

about the true nature of Uruk trading stations in that part of the world.

Despite

Stein’s critical appraisal of the comparative world-systems approach, his work

confirms what Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) have argued, that core/periphery

hierarchies in early state-based world-systems were limited in spatial scale

and relatively unstable. Early states were not able to extract resources from

distant peripheries because they were unable to project military power very far

and they did not have elaborated capitalistic mechanisms for facilitating

unequal exchange.

Joyce Marcus’s (1998) study of early states points

out that the interstate system of Mesopotamia exhibited a cycle of “rise and

fall” in which the largest polities increase and then decrease in size, and

that this phenomenon is also known in other cases of ancient state systems in

the Andes and Mesoamerica. Indeed, all

hierarchical world-systems exhibit a structurally similar cycle -- from the

“cycling” of chiefdoms (Anderson 1994) to the rise and fall of great empires,

and the rise and fall of hegemonic core states in the modern world-system.

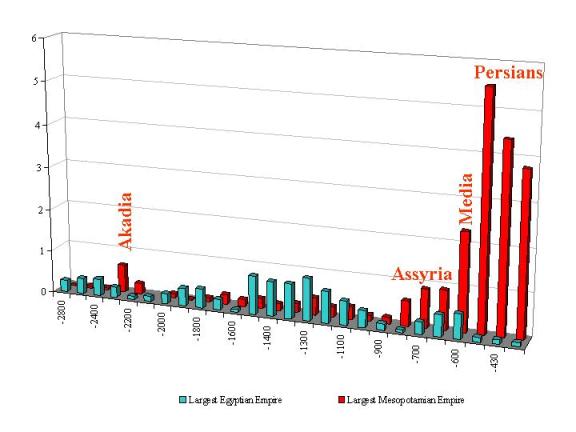

Figure 1

: Territorial sizes of Mesopotamian States and Empires (Source: Taagepera

1978a;1978b)

Figure 1 graphs the territorial

sizes of the largest states and empires in Mesopotamia from 3000 BCE to 1000

BCE as estimated by Taagepera (1978a, 1978b). The rise and fall phenomenon can

clearly be seen. Also the great size of Akkadian empire (6.5 square megametres)

was not equaled again until 800 BCE by the Neo-Assyrians, who then went on to

create a state that ruled 14 square megametres in 650 BCE. This was a new level

of political integration of territory more than twice the size of the Akkadian

empire. We also have data on the sizes of many of the largest cities in

Mesopotamia. The Pearson’s r

correlation coefficient for the relationship between Mesopotamian largest city

and empire sizes based on 13 time points from 2800 to 650 BCE is .59. This

indicates that, as would be expected, large empires build large cities and the

processes that cause growth and decline phases affect both urbanization and empire

formation.[4]

David

Wilkinson (2000) has coded the power configuration sequence of the ancient

Southwest Asian state system from Early Dynastic II through the Kassite-Hurrain

period. Wilkinson conceptualizes state systems in terms of a sequence of power

configurations and we have recoded these in terms of degrees of centralization

of power:

6: universal state (one superpower, no great powers, no more than two

local

powers)

5 : hegemony (either one superpower, no great powers, three or more

local powers; or no superpowers, one great power, no more than one

local

power)

4: unipolar (all other

configurations with one superpower)

3: bipolar (two great powers)

2 : tripolar (three great powers)

1: multipolar (more than three great powers)

0 : nonpolar (no great

powers)

It is

reasonable to suppose that power configurations should be positively correlated

over time with the territorial size of the largest empire. Figure 2 confirms

this correlation for ancient Southwest Asian system.[5]

Figure 2:

Power Configurations and the Territorial Size of the Largest Empire

Figure 2:

Power Configurations and the Territorial Size of the Largest Empire

The Jemdet Nasr and Early

Dynastic periods saw the further growth of cities in Mesopotamia and seven

centuries of an intercity-state system with the rise and fall of hegemonic core

states but no successful formation of a core-wide empire. This sequence is quite different from what

happened in Egypt, where the emergence of monumental cities and large-scale

agriculture led to much larger territorial states, and very soon to a core-wide

empire (see Figure 4 below).[6]

The explanations for these differences have long been alleged to be ecological,

having to do with the differences in the communications and transportation

possibilities in the two regions. Whereas the Nile is a single and quite

navigable river both upstream and downstream, the Tigris and the Euphrates are

much less navigable, and so communications and trade routes are more complex in

Mesopotamia. In Egypt a state can easily get effective control of the entire

agricultural heartland by controlling movement on the Nile, while in

Mesopotamia central control of flows of information and goods is much more

difficult to gain (Mann 1986). Thus the

process of empire building took much longer in Southwest Asia than it did in

Egypt (See Figure 4 below).

This ecological explanation is

now often disparaged by those who compare Mesopotamia and Egypt (e.g. Baines

and Yoffee 1998) in favor of cultural differences that may have led to the

differences in political organization. But it is equally plausible that the

cultural differences were themselves consequences of ecological and political

structures. In Egypt the temple economy last far longer before it was

transformed into state led by a warrior-king because early empire formation

along the Nile was not challenged by adjacent strong states. In Mesopotamia

each of the city-states needed to constantly defend its sovereignty from

competing adjacent states. Many of the cultural differences between the two

regions are due to these ecological and geopolitical differences.

Sargon

Though there were several

efforts by powerful states to conquer the whole core region of Mesopotamia,

this goal was not reached until the emergence of the Akkadian Empire in 2350

BCE. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997: 84-89)

presented a case for this first core-wide empire as an instance of a

semiperipheral marcher state conquest.

This was based on the notion that the Akkadian-speaking conquerors were

recently settled nomadic pastoralists in Northern Mesopotamia who used elements

of political organization and military technology stemming from there formerly

peripheral origins to conquer the old core city-states and erect a larger

empire. This portrayal is challenged by

evidence that the Akkadian language had long been present in both Northern and

Southern Mesopotamia and that Agade, the capital of the Akkadian Empire was

probably established after the

Sargonic conquest rather than being a city populated by recently settled

ex-nomads (Postgate 1992:36). Though archaeologists have not yet firmly

identified the location of Agade among the thousands of mud-heaps (tells) in

Iraq, it is thought that Agade was built in the northern part of the

Mesopotamian region.

By the time of the Sargonic

conquest the characterization of Northern Mesopotamia as semiperipheral is

problematic. The northern part of the alluvium was more heavily urbanized than

the south (Adams 1981) in the Early Uruk period, but the situation reversed

toward the end of the Uruk period with the exponential growth of Warka. The

north may have had a greater concentration of Akkadian speakers (Postgate

1992:38), but some of the northern cities, (e.g. Kish) had long been among the

contenders for hegemony in the intercity-state system of the Early Dynastic

period. These particulars favor an interpretation of the Akkadian conquest that

is more based on class and ethnic cleavages in Mesopotamia than on the

core/periphery dimension (Yoffee 1991).

The Akkadian regime, called an

"upstart dynasty" by Postgate (1992), made the Akkadian language the

official language of the state and, under Sargon’s son Naram-sin (2291 BCE),

imposed a standardized system of weights and measures across the Mesopotamian

core. After the fall of the Akkadian

dynasty there was a period of disorder in which the Gutians (nomadic people

from the Zagros Mountains) infiltrated the Mesopotamian core region and

contended for power. The north-south dimension of conflict continued to be a

cultural and geopolitical fault-line.

The Third Dynasty of Ur (2113 BCE) reasserted southern dominance and

Sumerian culture. David Wilkinson (1991) notes a pattern that he calls

"shuttling" in which centralized power shifted back and forth between

two adjacent regions. This pattern of shuttling rise and fall, now increasingly

composed of multi-city states, characterizes what happened in Southwestern Asia

throughout the rest of the period until the Babylonian Empire and the end of

the period we are studying in this paper. Subsequent Mesopotamian Empires until

1500 BCE were not larger than the Akkadian Empire had been (see Figure 1), and

the location of the most powerful states shuttled back and forth between

Northern and Southern Mesopotamia.

Core and Periphery

The most serious incursions of

peripheral tribes occurred during periods of political disorder in the core

regions. There were probably both “push” and “pull” factors involved in this

pattern of recurrent incursions. Disorder amongst the “civilized” states made

them vulnerable and encouraged interlopers. And nomadic pastoralists and hill

tribes probably had their own organizational dynamics (Hall 1991; 2000). We

know from other areas that nomadic pastoralists have their own cycles of

centralization and decentralization (Barfield 1989). And climate changes affected both the abilities of the agrarian

states to produce food and the abilities of the nomads to raise herds. Thompson (2000: Figure 3) indicates that

there is a fairly good correspondence over time between the size of the largest

Mesopotamian state and the Tigris/Euphrates river levels. This is encouraging for the hypothesis that

climate change is related to rise and fall, and it may be an important factor

in peripheral incursions.

The Amorite tribes were nomadic

pastoralists coming from the deserts of the northwest. In order to prevent

their incursions the Ur III dynasty constructed a Great Wall of Mesopotamia

clear across the northern edge of the core region (Postgate 1992:43). But there were also new invasions from the

east by Elamites and it was a combination of Amorite and Elamite incursions

that led to the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur. There followed the Isin-Larsa period in which small independent

states each had an Amorite ruling house, and the Old Babylonian period that

followed was a system of rather larger multicity states. The Amorite kings of

Babylon, including the famous Hammurapi, expanded their empire until Babylon

was itself conquered in 1595 BCE by a new group of nomadic invaders, the

Hittites, led by Murcilis.

Merchant Capitalism

During these developments trade

networks continued to expand, albeit unevenly. Periods of peace and empire

allow trade to become more intense and goods to travel farther. The commodification of goods and wealth had

long been emerging within and between the states of Mesopotamia. Contracts of

sale of lands and interest-bearing loans were know from the Early Dynastic

period, and prices were clearly reflecting shortages in the Ur III period. In the Old Babylonian period we find a clear

instance of a phenomenon that became more frequent and widespread in the later

commercializing tributary empire systems -- the semiperipheral capitalist

city-state (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997:90-93).[7] This was the Old Assyrian merchant dynasty

based in Assur on the upper Tigris, with its colonial enclaves of Assyrian

merchants located in distant cities far up into Anatolia and beyond (Larsen

1987,1992). Assur was a merchant capitalist city-state with a far-flung set of

colonies in the midst of an interstate system in which most states were still

pursuing a strategy of territorial expansion.

The capitalist city-state

phenomenon is clearly a different kind of semiperipheral development from that

of the semiperipheral marcher state.

These states pursued a policy of profit making rather than the

acquisition of territory and the use of state power to tax and extract

tribute. They emerged in the

interstices between the territorial states in world-economies in which wealth

could be had by buying cheap and selling dear (merchant capitalism). One of

their consequences was the expansion of trade networks because their commercial

activities provided incentives for distant producers and accumulators to use

surpluses for trade and to produce surpluses beyond local needs for this purpose.

Thus the capitalist city-states were agents of commodification and the

expansion and intensification of a regional division of labor.

The Old Assyrian merchants,

unlike most capitalist city-states, were not maritime specialists (as were e.g.

the Phoenicians, Venice, Genoa, Malacca, etc.). But they did occupy a key

transportation site that enabled them to tap into profit streams created by the

exchange of eastern tin and Mesopotamian textiles for silver. Bronze was being

produced in Anatolia using copper from the north and tin imported from the

east, probably from regions that are now part of Afghanistan. The demand for tin was great and the

worshippers of Assur were able to profitably insert themselves into this trade

by negotiating treaties with the other states in the region that allowed them

access to markets at agreed upon taxation rates. They also organized and carried out the transportation of goods

over long distances by means of donkey caravans, and they produced an effective

structure of self-governance. This is an early instance of what Philip Curtin

(1984) has called a “trade diaspora,” in which a single cultural group

specializes in cross-cultural trade.[8]

Most of the evidence that we

have about the Old Assyrian city-state and its colonies comes from the Kultepe

tablets at Kanesh, an archive of business records and letters that show how the

Old Assyrians organized and governed their business activities (Veenhof

1995). The records show that these were

merchants trading on their own accounts for profit, not agents of states

carrying out "administered trade" akin to tribute exchanges. Though Karl Polanyi (1957) was wrong about

the Old Assyrians in this regard, his larger perspective on the evolution of

institutional modes of exchange remains an important contribution to our

understanding of the qualitative differences between kin-based, state-based and

market forms of integration. The conquest empire of the Hittites was certainly

a case of the semiperipheral marcher state strategy in which recently settled

nomads overwhelmed an interstate system and created a new and larger empire.

The later history of Assur is

also an interesting case that is relevant for our understanding of

semiperipheral development. The Old Assyrians were conquered by an Amorite

sheik. Their later re-emergence as the Neo-Assyrian empire was a fascinating

instance of a semiperipheral capitalist city-state switching to the marcher

state strategy of conquest,[9]

and their success in this venture created an empire that was larger than any

other that had been before it in Southwestern Asia (see Figure 1).

From Peripherality to Semiperipherality

In

the hinterlands, "beyond the pale" dwelt those labeled

"barbarians," which might be glossed "the not like us"

peoples. What were their relations to

sedentary peoples and how did they change?

Much of this will be forever shrouded by the paucity of hard

evidence. Hence we are forced to use

much later sedentary - nomad relations to gain insights into the first

relations. Such ethnographic

"upstreaming" is always hazards, the more so when origins of are the

subject of investigation. Still, we can

posit trading and raiding two ways in which nomadic peoples can interact with

sedentary peoples. Even when the

nomadism is bipedal, nomads have immense advantages over sedentary

peoples: they are fewer, they are

mobile, more importantly, their resources are also mobile, they now their

territory intimately, and their sedentary foes are, literally, sitting

ducks. In fact, the only way raiding

nomads can be subdued is to sedentarize them -- something seldom if ever

possible until last few centuries.

On

the other hand, we learn from Barfield's account that the popular image of

nomads as destroyers is a gross exaggeration.

Here one must distinguish between a city or village that is destroyed in

a raid, versus an entire empire which readily outlasts all such raids. Nomads

cannot profit from either raiding or trading with a failing state

because there will be little or nothing to raid or trade for! This is fundamentally what is behind

Barfield's seemingly surprising finding that steppe confederacies were strong

only when China was strong, and weak when it was weak. He does note, however, that things were

often different in West Asia where states were smaller and weaker than

China. While Bronze Age states were

assuredly weaker, so were the various surrounding nomads.

Owen

Lattimore (1968) cites a Chinese proverb to the effect that while one can

conquer from horseback, one cannot rule from there. Whether we are discussing mounted pastoralists, or prehorse

nomads, the principle is the same: To

maintain a conquest over sedentary peoples, nomads must cease being nomads. One of the major problems with ancient

accounts of nomadic incursions is that it is often difficult to tell ay

particular instance was a relatively gradual process of in-migration with new

language coming into dominance, or a military conquest that transformed the

nomadic conquerors into a new dynasty.

The

conventional approach, that nomads conquer weak states, may hold when nomads

essentially overplay their hand of raiding to gain better terms of trade and

then end up running the place, and ceasing to be nomads. This, of course, would be highly remarked in

written records. Whereas, centuries of

intermittent raids, which alternate with trade, would go unremarked.

But

other than accidentally overplaying their raiding, why would nomads conquer

sedentary peoples? There may have been

variants in Western Asia of what William McNeill (1987) has called the Steppe

gradient. There was a tendency for

steppe pastoralists in Central Asia to move westward because the grasses are

better toward the east, so strong nomadic confederations tended to emerge in

the east, near China, displacing losing groups toward the west. There were probably localized versions of

this phenomenon in Western Asia.

This

is one of the ways in which climate change, even relatively small climate

change, can have strong effects. Slight

shifts in rainfall patterns can change considerably the limits of useful

rangeland for pastoralists. If any one

group moves, all their neighbors, sedentary and nomadic, are affected. Here it is important to keep in mind the

volatility of pastoral strategies. An

abundance of grass in just a few seasons can lead to an explosion of herd

sizes, unleashing quest for more pastures.

The quest will intensify if the climate turns dryer and grasses become

scarce. This, too, can unleash

migrations and conquests, in which nomads seek to take over farmland for

pastureland.

Here

it is vital to see this as part of a larger system. Farmers and herders utilize different resources and different

ecologies. Typically, but not always,

land that is very suitable for pastoralism is not suitable for farming. This

produces differentiation between farming and herding. Yet neither adaptation is

wholly self-sufficient and this produces incentives for trade. But this type of differentiation readily

turns into hierarchy, since sedentary populations far outnumber pastoral

populations. By trading assorted

"surplus" goods, sedentary peoples encourage nomads to produce a

surplus of meat and animal by- products on land that is often not suitable for

cultivation.

Most

important for our argument about systemness and the entraining of processes across regions, nomads are often a key

link that transmit changes in one region to distant regions. This, of course, was the argument of Frederick

Teggart (1939) in Rome and China. For instance, one can imagine a

state becoming weakened by a dynastic succession struggle. This could undercut the amount of surplus

available for trade, especially with pesky barbarians. Those barbarians then could either step up

raids to acquire what could no longer be obtained by trade, further weakening

the state and undermining the legitimacy of the ruling elite. If this led to a collapse of the agrarian

state nomads might take over and run the state themselves. But unless they had

sufficient numbers, knowledge, and organization this outcome would be rare.[10]

If nomadic peoples are frustrated in their interactions with existing states

they seek elsewhere for necessary goods, and to sell off their surplus. This could start a gradient of clashes that

would ramify far across intervening territories. If no alternatives were available, the nomadic society might

itself experience a secondary collapse in reaction to the agrarian state

collapse. This could actually open new

territory to nomads from elsewhere looking for new pastures. Nomads can also

facilitate or hinder long distance trade between agrarian states. Small nomadic

groups that raid trade caravans make long-distance trade risky and expensive.

But a large nomadic confederation can agree to supply security to merchant

caravan for a fee, making the risks and returns from trade venture much more

calculable. Thus, we can expect some correlation of events between distant

sedentary states and empires due to the transmission belts that nomadic groups

constitute.

Egyptian and Mesopotamian Synchrony?

As the Mesopotamian and

Egyptian cores and their trade networks expanded they came to have more and

more direct and consequential connections with one another. Writing developed

in Mesopotamia and Egypt at about the same time and there may have been a

diffusion of the idea of two-dimensional systems of symbolic codes (writing) in

one direction or both. This would indicate that the information networks and

the prestige goods networks were already connected. This raises the possibility

that the cycles of rise and fall and the growth of cities may have become

synchronized in the two core regions.

Research has demonstrated this

phenomenon for the later cases of East and West Asia between 600 BCE and 1500

CE (Chase-Dunn, Manning and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and Manning 2002). These were two distant core regions linked

by a prestige goods network, but they had no direct political/military

interaction. This synchronization of

East and West Asian city growth/decline phases and the rise and fall of large

states has been tested and retested and now begins to assume the status of a

fact. It was a similar situation in some ways to the relationship between

Mesopotamia and Egypt before 1500 BCE. Two separate agrarian core regions were

trading prestige goods with one another, and much of the intervening territory

was inhabited by nomadic pastoralists.

Regarding the hypothesis of

Mesopotamian/Egyptian synchrony, Chase-Dunn and Hall (2000: 105) examined

estimates of the population sizes of cities in Mesopotamia and Egypt based on

data from Chandler (1987) and the territorial sizes of empires from Taagepera

(1978a, 1978b). They found little support for the synchronization

hypothesis. Table 1 below replicates

that earlier effort by supplementing the Chandler (1987) data with estimates

from Modelski (2003) and with an improved method of detrending. The empire size

data are from Taagepera.

Although these data still contain the same reliability limitations as previous estimates of urban populations, Modelski’s compendium represents the most complete and current compilation of urban populations. Modelski began with Chandler’s compendium of urban populations and then expanded and improved the coverage using newer and more recent historical information. Using Modelski’s data set we have enlarged our data set for Egyptian and Mesopotamian cities from 7 to 23 time points in the Egyptian PMN and from 16 time points to 25 time points in Mesopotamia.

|

|

City-to-city

correlations across PMNs |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Region |

Pearson’s r |

Sig. Lev. |

N |

Years |

|

|

|

Egypt-Mesop |

0.073 |

0.370 |

23 |

2800 B.C.E. - 400

B.C.E. |

|

|

|

Egypt-Mesop |

0.152 |

0.348 |

9 |

2800 B.C.E. - 1500

B.C.E. |

|

|

|

Egypt-Mesop |

0.177 |

0.264 |

15 |

1500 B.C.E. - 400

B.C.E. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Empire-to-empire

correlations across PMNs |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Region |

Pearson’s r |

Sig. Lev. |

N |

Years |

|

|

|

Egypt-Mesop |

-0.086 |

0.344 |

24 |

2800 B.C.E. - 400

B.C.E. |

|

|

|

Egypt-Mesop |

-0.140 |

0.350 |

10 |

2800 B.C.E. - 1500

B.C.E. |

|

|

|

Egypt-Mesop |

-0.049 |

0.432 |

15 |

1500 B.C.E. - 400

B.C.E. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

Pearson's r significant at the 0.05 level. |

|

|

|

||

|

** |

Pearson's r significant at the 0.01 level. |

|

|

|

||

Table 1:

Mesopotamian and Egyptian City and Empire Correlations based on Percentage

Change Scores For Different Time Periods

We tested the hypothesis of

synchrony of growth and decline between Egyptian and Mesopotamian city sizes

and empires sizes using the percentage change score. The change score

methodology was used to rule out the long-term secular increase in city and

empire sizes. The synchrony hypothesis is about the phase relationships among

medium-run growth/decline phases. A simple bivariate correlation between

regions would necessarily be positive in part due to the long-run secular

upward trend. In our earlier work we detrended by calculating a partial

correlation that controls for time. But this presumes that the long-term trend

is linear, while observations of city and empire growth suggest a long-term

accelerating increase. Detrending with percentage change scores does not

presume the shape of the long-term trend. The percentage change score is

calculated as follows: %Δ = (T2-T1/T1)/N where N in the number of decades

comprising interval T. The latter term is necessary because the intervals

between measurement time points are not always of equal lengths.

None

of the correlation coefficients in Table 1 are statistically significant,

confirming our earlier finding of no support for the hypothesis of synchrony

between Mesopotamia and Egypt. We examine three different time periods, and

find no synchrony for any of them.

Figures 3 and 4 display the raw size data for the largest

cities and the largest empires in Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Figure 3: Largest Cities in Egypt and Mesopotamia from 2800 BCE to 430 BCE

Figure 4: Largest Empires in Egypt and Mesopotamia from 2800 BCE to 430 BCE

The

question of synchrony and the causes of rise and fall and urban growth/decline

phases in early state systems will require further empirical examination. Both the city and territorial size data sets

need to be improved by correcting mistakes and adding data from recently

published studies. Even though there is little indication of

Mesopotamian/Egyptian inter-regional synchrony, it remains possible that

climate change and interactions with peripheral nomads can explain the cyclical

patterns in each that are revealed in Figures 3 and 4.

There

is considerable support for cycles of rise and fall and sequences of trade

expansion and contraction in the Bronze Age and early Iron Age world-systems.

The hypotheses of semiperipheral development is confirmed for some instances of

tranformation, but not for others. We have presented a strong case for the

importance of interactions with nomads and the likelihood that climate change

has played an important role in the processes of uneven development in the

prehistoric and early state-based world-systems.

Bibliography

Adams, Robert McCormick 1965 Land Behind Baghdad: A History of Settlement on the

Diyala Plains.

Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

____________1966 The

Evolution of Urban Society: Early Mesopotamia and Prehispanic

Mexico. Chicago:

Aldine.

____________1981 Heartland

of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on

the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

____________1984 "Mesopotamian social evolution: old

outlooks, new goals." Pp. 79-

129 in Timothy Earle (ed.) On

the Evolution of Complex Societies: Essays in

Honor of Harry Hoijer. Malibu, CA.: Undena Publications.

Adams, Robert McCormick and Hans Nissen 1972 The Uruk Countryside. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Algaze, Guillermo 1993 The

Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early

Mesopotamian Civilization Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

________ 2000 “The prehistory of imperialism:

the case of Uruk period

Mesopotamia”

in M. Rothman. (ed.) Uruk Mesopotamia and

its

Neighbors:

Cross-cultural Interactions and their Consequences in the Era of

State

Formation.

Santa Fe: School of the Americas

Al Khalifa, Shaikha Haya and Michael

Rice (eds.) 1986 Bahrain through the

ages: the archaeology. London:

Routledge.

Allen,

Mitchell. 1992. "The Mechanisms of Underdevelopment: An

Ancient

Mesopotamian

Example." Review 15:3(Summer)453-476.

Anderson, David G. 1994 The Savannah River Chiefdoms: Political Change in the Late

Prehistoric Southeast. Tuscaloosa: University of

Alabama Press.

Baines, John and Norman Yoffee 1998 “Order, legitimacy

and wealth in ancient Egypt

and Mesopotamia,” Pp. 199-260

in Gary M. Feinman and Joyce Marcus

(eds.)

Archaic States. Santa Fe: School of American Research.

Bar-Josef, Ofer and Anna Belfer-Cohen 1991 “From

sedentary hunter-gatherers to

territorial farmers in the

Levant.” Pp. 181-202 in Susan A. Gregg (ed.) Between

Bands and States. Carbondale, IL.: Center for Archaeological

Investigations,

Occasional Papers #9.

Barfield, Thomas J. 1989 The Perilous Frontier. Cambridge, MA.: Blackwell.

Bean, Lowell John and Harry Lawton 1976 " Some

explanations for the rise of

cultural complexity in Native

California with comments on proto-agriculture

and agriculture." Pp.

19-48 in Native Californians: A

Theoretical Retrospective.

L. J. Bean and Thomas C.

Blackburn (eds.) Socorro, NM: Ballena Press.

Bosworth, Andrew 1995

“World cities and world economic cycles”

Pp. 206-228 in

Stephen Sanderson (ed. ) Civilizations and World Systems. Walnut

Creek, CA.: Altamira.

Butzer, Karl 1995

“Environmental change in the Near East and human impact on the land,”

Pp.

123-151 in Jack M. Sasson et al Civilizations of the Ancient Near

East Vol. 1. New

York:

Scribners

Butzer Karl.W. 1997 "Sociopolitical Discontinuity in

the Near East C. 2200 BCE:

Scenarios from Palestine and Egypt," in H.N. Dalfes,

G. Kulka, and H. Wiess,

eds.,

Third Millennium BC CLimate Change and

Old World Collapse. Berlin:

Springer

Chandler, Tertius 1987 Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth

Lewiston,NY: Edwin

Mellen

Press.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Kelly M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and Their

Neighbors: A

Very Small World-System in Northern California.

Tucson, AZ.: University of

Arizona

Press.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise:

Comparing

World-Systems. Boulder, CO.: Westview.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Thomas

D. Hall 1999 "The Chesapeake world-system"

http://wsarch.ucr.edu/archive/papers/c-d&hall/asa99b/asa99b.htm

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Thomas D. Hall 2000 “Comparing world-systems to explain

social

evolution.” Pp. 85-111 in Robert Denemark, Jonathan Friedman, Barry Gills

and George Modelski (eds.) World System History. London: Routledge

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Susan

Manning and Thomas D. Hall, 2000

"Rise

and Fall: East-West Synchronicity and Indic Exceptionalism Reexamined"

Social Science History 24,4: 721-48(Winter) .

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Susan Manning, 2002

"City systems and

world-systems: four millennia of city growth and decline,"

Cross-Cultural Research 36, 4: 379-398

(November).

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Andrew K.

Jorgenson, “Regions

and Interaction Networks:

an institutional materialist perspective,” 2003 International Journal of Comparative

Sociology 44,1:433-450. http://www.irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows13/irows13.htm

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Alexis Alvarez and Daniel Pasciuti Forthcoming. “Size and

power:

urbanization and empire formation in world-systems” In C. Chase-Dunn and

E.N.

Anderson (eds.) The Evolution of World-Systems. London: Palgrave.

http://www.irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/isa02/isa02.htm

Cioffi-Revilla, Claudio

1991 “The long-range analysis of war,” Journal

of

Interdisciplinary History 21:603-29.

________ 1995 “War and

politics in ancient Mesopotamia, 2900-539 BC: measurement

and

comparative analysis.” LORANOW Project. Political Science, University

of

Colorado.

Collins, Randall 1992 "The geographical and

economic world-systems of kinship-based

and agrarian-coercive societies." Review 15,3:373-88 (Summer). Westport,

CT.:

Greenwood

Press.

Cooper, J.S. 1973 "Sumerian and Akkadian in Sumer

and Akkad." Pp. 239-246 in G.

Buccellati (ed.) Approaches to the Study of the Ancient Near

East: A Volume of

Studies Offered to Ignace J.

Gelb. Orientalia 42.

Cooper, Jerrold S. 1983a The Curse of Agade.

Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins

University Press.

_________1983b "Reconstructing History of Ancient

Inscriptions: The Lagash-Umma

Border

Conflict." Sources from the Ancient

Near East 2,1. Malibu, CA. Undena

_________1989 "Writing." International

Encyclopedia of Communications 4:321-31.

_________ 1993 "Paradigm and propaganda: the dynasty

of Akkad in the 21st

century."

Pp. 11-23 in M. Liverani (ed.) Akkad: The First World Empire.

Padua: Sargon.

Curtin, Philip D.1984 Cross-cultural

Trade in World History. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Diakonoff, Igor M. 1954 "Sale of land in

pre-Sargonic Sumer." Papers

presented by

the Soviet delegation at the

Twenty-third International Congress of

Orientalists, Assyriology

Section. Moscow: USSR Academy of

Sciences.

_________1969 "Main features of the economy in the

monarchies of ancient Western

Asia." Ecole Practique des Hautes Etudes-Sorbonne,

Congres at Colloques 10,

3: 13-32. Paris and The Hague:

Mouton.

__________1973 "The rise of the despotic state in

ancient Mesopotamia." Pp. 173-203

in I. M. Diakonoff (ed.) Ancient Mesopotamia. G. M. Sergheyev

(transl.) Walluf

bei Wiesbaden: Dr. Martin Sandig.

__________1974 Structure

of Society and State in Early Dynastic Sumer. Monographs

on The Ancient Near East 1,

3. Los Angeles: Udena Publications.

_________1982 "The structure of Near Eastern society

before the middle of the 2nd

millenium B.C." Oikumene 3: 7-100, Publishing House of

the Hungarian

Academy of Sciences.

Eckhardt, William 1992 Civilizations, Empires and Wars: A

quantitative history of war

Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Ekholm, K. and J. Friedman 1982 "Capital"

Imperialism and Exploitation in Ancient

World-Systems, Review 6 (1): 87-110.

Fagan, Brian 1999 Floods, Famines and Emperors: El

Nino and the Fate of Civilizations. New York:

Basic Books.

Falkenstein, Adam 1974 The Sumerian Temple City.

Monographs on the Ancient

Near East 1, 1 Los Angeles:

Udena Publications.

Farber, Howard 1978 "A price and wage study for

Northern Babylonia during the

Old Babylonian period," Journal of the Economic and Social History

of the Orient

21, 1:1-51.

Feinman, Gary M. and J. Marcus (eds.) 1998 Archaic States. Santa Fe: School of

American Research.

Flannery, Kent V. 1999a “Process and agency in early

state formation.” Cambridge

Archaeological Journal 9,1: 3-21.

______________ 1999b “The ground plans of archaic

states.” Pp. 15-57 in G. Feinman

and J. Marcus (eds.) Archaic States. Santa Fe, NM: School of

American Research

Frank, Andre Gunder 1993 “The bronze age world system and

its cycles.” Current

Anthropology 34:383-413.

Friedman, Jonathan and Michael J. Rowlands 1977

"Notes towards an epigenetic

model of the evolution of

`civilization'." Pp. 201-278 in J.

Friedman and M. J.

Rowlands (eds.) The Evolution of Social Systems. London: Duckworth.

Galvin, Kathleen F. 1987 “Forms of finance and forms of

production: the evolution of

specialized livestock

production in the ancient Near East.” Pp. 119-129 in

Elizabeth Brumfiel and Timothy

K. Earle (eds.) Specialization, Exchange

and

Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gibson, McGuire 1972 The

City and Area of Kish. Miami: Field

Research Projects.

Gills, Barry K.1995 “Capital and power in the processes

of world history,” Pp. 136-162

in

Stephen Sanderson (ed.) Civilizations and

World Systems. Walnut Creek,

CA.: Altamira Press.

Hall, Thomas D. 1991 “The role of nomads in core/periphery

relations.” Pp. 212-239

in C. Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall

(eds.) Core/Periphery Relations in

Precapitalist

Worlds. Boulder, CO.: Westview.

_______ 2000

“Sedentary-nomad relations in prehistoric and ancient Western Asia:

questions and speculations.” Paper presented

at the annual meeting of the

International

Studies Association, Los Angeles.

Hayden, Brian 1981 “Research and development in the Stone

Age: technological

transition among

hunter-gatherers.” Current Anthropology

22,5:519-548.

Helms, Mary

W. 1988. Ulysses' Sail: An Ethnographic Odyssey of Power, Knowledge,

and Geographical Distance.

Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

_____. 1992.

"Long-distance Contacts, Elite Aspirations, and the Age of

Discovery

in Cosmological

Context." Pp. 157-174 in Resources, Power, and Interregional

Interaction,

edited by Edward

Schortman and Patricia Urban. New

York: Plenum Press.

Kardulias, P. Nick

1999 “Multiple levels in the Aegean Bronze Age World-System.”

Pp. 179-202 in P.

Nick Kardulias (ed.) World-Systems Theory

in Practice. Lanham, MD.:

Rowman and Littlefield.

Kenoyer, Jonathan

M. (ed.) 1994 From Sumer to Meluhha:

Contributions to the archaeology of

South and West Asia in memory of George F. Dales,

Jr. Wisconsin Archaeological Reports,

Vol. 3.Madison,

WI.: Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin

Kenoyer, Jonathan

M. 1998 Ancient Cities of the Indus

Valley Civilization. Karachi:

Oxford University

Press.

Kohl, Phillip

L. 1978. "The Balance of Trade in Southwestern Asia in the

Mid-Third Millennium B.C." Current

Anthropology 19:3(Sept.):463-492.

_____. 1979.

"The 'World Economy' in West Asia in the Third Millennium

B.C."

Pp. 55-85 in South Asian Archaeology 1977, edited by M. Toddei.

Instituto

Universitario Orientale, Naples.

_____. 1981.

"Materialist Approaches in Prehistory." Annual

Review of Anthropology 10:89-118.

_____. 1985.

"Symbolic Cognitive Archaeology:

A New Loss of Innocence."

Dialectical Anthropology 9:105-117.

_____. 1987a.

"The Use and Abuse of World Systems Theory: the Case of the

'Pristine' West Asian State." Pp. 1-35 in Archeological Advances in Method and Theory

11:1-35. New York:

Academic Press.

_____. 1987b. "The Ancient Economy,

Transferable Technologies and the Bronze

Age

World-system: A View from the

Northeastern Frontier of the Ancient Near East." Pp. 13-24 in Centre and

Periphery in the Ancient World, edited by Michael Rowlands, Mogens Larsen

and Kristian Kristiansen.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

_____. 1988.

"State Formation: Useful

Concept or Idée Fixe?" Pp. 27-34

in Power Relations and State Formation,

edited by Christine W. Gailey and Thomas C. Patterson, pp. 27-34. Washington, D. C.: American Anthropological Association.

_____. 1992.

"The Transcaucasian "Periphery" in the Bronze Age: A Preliminary Formulation." Pp. 117-137 in Resources, Power, and Interregional Interaction, edited by Edward

Schortman and Patricia Urban. New

York: Plenum Press.

Kohl, Philip L.

and Rita P. Wright. 1977. "Stateless Cities: The Differentiation

of Societies in the Near Eastern Neolithic." Dialectical Anthropology

2:271-283.

Lamberg-Karlovsky,

C. C. 1975. "Third Millennium Modes of Exchange and Modes of

Production." Pp. 341-368 in Ancient Civilization and Trade, edited

by J. A. Sabloff and C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky.

Albuquerque: University of New

Mexico Press.

Larsen, Mogens Trolle 1976 The Old Assyrian City-State and Its Colonies. Copenhagen:

Akadmisk Forlag.

Larsen, Mogens

Trolle. 1987. "Commercial Networks in the Ancient Near East." Pp. 47-56 in Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World, edited by Michael

Rowlands, Mogens Larsen, and Kristian Kristiansen. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

_____. 1992.

"Commercial Capitalism in a World System of the Early Second

Millennium B.C." Paper presented

at International Studies Association, Atlanta, GA.

Lerro, Bruce 2000 From Earth-Spirits to Sky-Gods. Lexington

Press.

Mann, Michael.

1986. The Sources of Social Power: A

History of Power from the Beginning to A.D. 1760. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Marcus, Joyce 1999 “The peaks and valleys of ancient

states.” Pp. 59-94 in G. Feinman

and J. Marcus (eds.) Archaic States. Santa Fe, NM: School of

American

Research.

Marfoe, Leon 1987

"Cedar forest and silver mountain: social change and the development of

long-distance trade in early Near Eastern societies," Pp. 25-35 in M.

Rowlands et al Centre and Periphery in

the Ancient World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McNeill, William

H. 1963 The Rise of the West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Modelski, George

2003 World Cities: –3000 to 2000. Washington, DC: Faros 2000

Moore, Andrew M.T.

1982 “The first farmers in the Levant.” Pp. 91-112 in Young, Smith and

Mortenson, The Hilly Flanks.

McNeill, William

H. 1963 The Rise of the West. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Midlarski, Manus

I. 2000 “The rise and decline of ancient civilizations: the case of Egypt.”

Paper presented at the meetings of the International Studies Association, Los

Angeles, March 18.

Modelski, George

1997 “Early world cities: extending the census to the fourth millennium,”

Prepared for the annual meeting of the International Studies

Association,Toronto, March 21

__________ 1999

“Ancient world cities 4000-1000 BC: centre/hinterland in the world system.” Global

Society 13,4:383-392.

Morner, N.-A. and W.

Karlen (eds.) 1984 Climatic Changes on a Yearly to Millennial

Basis Boston: D. Reidel

Neumann, J. and S.

Parpola 1987 “Climatic change and the eleventh-tenth century

eclipse

of Assyria and Babylonia,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies

46:161-182.

Nissen, Hans J.

1988. The Early History of the Ancient Near East,9000-2000 B.C. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Oppenheim, A. L. 1957 "A bird's-eye view of

Mesopotamian economic history."

Pp.

27-37 in K. Polanyi, C. M.

Arensberg and H. E. Pearson (eds.) Trade

and

Market in the Early Empires. Chicago: Regnery.

___________1969 "Comment on Diakonoff's 'Main

features of the economy...'" Ecole

Practique des Hautes

Etudes--Sorbonne, Congres et Colloque 10, 3:33-40.

Polanyi, Karl 1957

"Marketless trading in Hammarabi's time." Pp. 12-26 in K.

Polanyi, C. M. Arensberg and H.

E. Pearson (eds.) Trade and Market in the

Early Empires.

Chicago: Regnery.

Polanyi, Karl, Conrad M. Arensberg and Harry W. Pearson

(eds.) 1957 Trade and

Market in the Early Empires. Chicago: Regnery.

Postgate, J. N. 1992

Early Mesopotamia : society and

economy at the dawn of

history London ;

New York : Routledge.

Redman, Charles L.

1978 The rise of civilization :

from early farmers to urban society in

the ancient Near East San Francisco : W. H. Freeman, c1978.

Renfrew, Colin R. (ed.) 1971 The Explanation of Culture Change: Models in Prehistory.

Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Renfrew, Colin

R. 1975. "Trade as Action at a Distance: Questions of Integration and Communication." Pp. 3-59 in Ancient Civilization and Trade, edited by J. A. Sabloff and C. C.

Lamborg‑Karlovsky. Albuquerque,

NM: University of New Mexico Press.

_____. 1977.

"Alternative Models for Exchange and Spatial

Distribution." Pp. 71-90 in Exchange Systems in Prehistory, edited

by T. J. Earle and T. Ericson. New

York: Academic Press.

_____. 1986.

"Introduction: Peer Polity

Interaction and Socio-political Change," Pp. 1-18 in Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-political Change, edited by C.

Renfrew and John F. Cherry.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Renfrew, Colin R.

and John F. Cherry, eds. 1986. Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-political

Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rice, Michael 1985

Search for Paradise: an introduction to

the archaeology of Bahrein and the Arabian Gulf, from earliest times to the

death of Alexander the Great. London: Longman.

Rowlands, Michael,

Mogens Larsen, and Kristian Kristiansen, eds.

1987. Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Runnels, Curtis

and Tjeerd H. van Andel 1988 “Trade and the origins of agriculture in the

Eastern Mediterranean.” Journal of

Mediterranean Archaeology 1,1:83-109.

Sahlins, Marshall 1972 Stone Age Economics. New

York: Aldine.

Schwartz, Glenn 1988 “Excavations at Karatut Mevkii and

perspectives on the

Uruk/Jemdet Nasr expansion.” Akkadica 56:1-41.

Seaman, Gary (ed.) 1989 Ecology and Empire: Nomads in the Cultural

Evolution of the

Old World Los Angeles: Ethnographics/USC, Center for

Visual

Anthropology,

University of Southern California

Schmandt-Besserat, Denise 1992 Before Writing: From Counting to Cuneiform. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

Solecki, Rose L. and Ralph S. Solecki 1982 “Late

pleistocene/ early holocene cultural

traditions in the Zagros.” Pp.

123-140 in Young, Smith and Mortenson. The

Hilly Flanks.

Snell, Daniel C. 1982 Ledgers

and Prices: Early Mesopotamian Merchant Accounts.

New Haven: Yale University Press.

Stein, Gil J. 1999 Rethinking

World-Systems: Diasporas, Colonies and

Interaction in

Uruk Mesopotamia. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Struve, V. V. 1973 [1933] "The problem of the

genesis, development and disintegration

of the slave societies in the

ancient orient" Inna Levit (Transl.) Pp. 17-69 in I.

M. Diakonoff (ed.) Ancient

Mesopotamia. Walluf bei

Wiesbaden: Dr. Martin

Sandig.

Taagepera, Rein 1978a "Size and duration of empires:

systematics of size," Social

Science Research 7, 108-127.

___________1978b "Size and duration of empires:

growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600

B.C.," Social Science Research 7, 180-196.

Thomas, H. L. 1982 “Archaeological evidence for the

migrations of the Indo-

europeans.” Pp. In E.C. Polome (ed.)

The Indo-europeans in the Fourth and

Third

Millennia. Ann Arbor: Karoma.

Thompson, William

R. 2000 “Climate, water, and center-hinterland conflict in the ancient

world-system.” Paper presented at the meetings of the International Studies

Association, Los Angeles, March 18.

Torrence, Robin 1986 Production

and Exchange of Stone Tools: Prehistoric Obsidian in

the Aegean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van de Mieroop, Marc 1999 The Ancient Mesopotamian

City. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Veenhof, Klass R. 1995 "Kanesh: an Assyrian colony

in Anatolia." Pp. 859-871 in

Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, Vol.

2. New York: Simon and Schuster

MacMillan.

Weiss, Harvey; M.-A

Courty, W. Wetterstron, F. Guichard, L. Senior and A. Curnow

1993 “The genesis and collapse of third millenium North

Mesopotamian

Civilization,”

Science 261:995-1004 (August 20).

___________ and Marie-Agnes Courty 1993 “The genesis and

collapse of the

Akkadian

Empire: the accidental refraction of historical law,” Pp. 131-155 in

Mario

Liverani (ed.) Akkad: the First World

Empire Padua: Sargon.

Wilkinson, David 1987

“Central Civilization.” Comparative Civilizations Review

17:31-59

(Fall).

______________ 1991

“Cores, peripheries and civilizations”

Pp. 113-166 in C. Chase-

Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.) Core/Periphery Relations in

Precapitalist Worlds

Boulder,CO.: Westview.

_________1992 “Cities,

civilizations and oikumenes,” Comparative

Civilizations

Review

Fall 1992, 51-87 and Spring 1993, 41-72.

_______2000 “Problems in

power configuration sequences: the Southwest Asian

Macrosystems to 1500 BC” Presented at the

meeting of the International Studies

Association, Los Angeles,

CA. February.

Wright, Henry

T. 1986. "The Evolution of Civilization." Pp. 323-365 in American

Archaeology, Past and Future: A Celebration of the Society for American

Archaeology, 1935-1985,

edited by David J.

Meltzer. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institutional Press.

___________1998

“Uruk states in Southwestern Iran.” Pp. 173-197 in Gary Feinman

and Joyce Marcus

(eds.) Archaic States. Santa Fe, NM:

School of American Research.

Yoffee, Norman

1991 “The collapse of ancient Mesopotamian states and civilization.”

Pp. 44-68 in

Norman Yoffee and George Cowgill (eds.) The

Collapse of Ancient States

and Civilizations. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Young, T.Cuyler,

Jr., Philip E. L. Smith and Peder Mortensen (eds.) 1982 The Hilly

Flanks and Beyond: Essays in the Prehistory of

Southwestern Asia Presented to Robert J.

Braidwood. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, Number

36. Chicago:

Oriental Institute

of the University of Chicago

Zaccagnini,

Carlo. 1987. "Aspects of Ceremonial Exchange in the Near East

During the Late Second Millennium

BC." Pp. 57-65 in Centre and Periphery in

the

Ancient World, edited by Michael

Rowlands, Mogens Larsen and Kristian

Kristiansen. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Zagarell,

Allen. 1986. "Trade, Women, Class and Society in Ancient Western

Asia."

Current Anthropology

27:5(Dec.):415-430.