This

chapter explains the philosophical and scientific principles that will

be the basis of our study of social change.It

provides an overview of different theoretical approaches and the basic

concepts of institutional materialism, the sociological perspective to

social change that is employed in the rest of the book.

Science

and Objectivity

The

scientific study of social change is not as straight-forward as studying

rocks or frogs.If we were extra-terrestrials

sitting on the moon observing Earthlings through a telescope it would not

be hard to attain a high level of objectivity.But

each of us is a human speaker of a particular language living in a specific

place with a head full of a particular cultural heritage and standing in

a certain relationship with the rest of the occupants of our planet. We

are men or women, American or Chinese, from New York or Bombay, Catholic

or Moslem, Republicans or Greens, Hunt Club or Bowling League. Objectivity

is a key requirement of science, and yet we are trying to be objective

about ourselves and our own history.Some

think that the enormity of this problem means that social science is impossible,

and so we should just surrender to subjectivity and enjoy it.But

another path is to try to attain a sufficient degree of objectivity by

becoming aware of the sources and strengths of our prejudices.To

do this we need to understand how science itself is a cultural product

and how scientists are influenced by social processes.We

need to place ourselves in historical perspective and then to use that

understanding as a basis for examining our own biases. We need to be clear

what the goals of social science are, even if they are unreachable in any

absolute sense.

It

has been said that science should be value-free in the sense that scientists

should try to ascertain the objective truth without allowing their beliefs

about good and evil to influence their judgments about what is true. I

will maintain this distinction in what follows.But

science also has its own values. It is a philosophical venture that has

its own goals, which are themselves taken on faith, or at least they are

provisionally accepted. When we play chess or basketball we agree to operate

on the basis of the rules of the game.When

we do science it is likewise. The philosophical presuppositions of science

are not themselves provable by means of science. Instead, they are values

that we may choose to affirm and defend.

The

main goals of the scientific study of social change are to understand the

truth about what happened in the human past and to build explanations of

the patterns of human behavior and social institutions. These explanations

should be objectively testable, relatively elegant (simple), and powerful

in the sense that theoretical propositions account for a lot of the patterns

of social change that can be observed.

Causal

propositions can be evaluated using the comparative method (see below).Explanations

will probably never be perfect, but scientific progress means better and

better approximations of the way social change actually works.

Ideally

this enterprise should approach social change from an Earth-wide perspective

rather than from the point of view of any particular society or civilization.

Modern science emerged from the European Enlightenment’s encounter with

the rest of the world during the rise of European hegemony. This historical

fact must be acknowledged and examined in order for it to be transcended

by a truly Earth-wide science of social change.

Social

science should also be objective with respect to the focus on human beings

in relationship to other forms of life.Humanism

is a fine ethical point of view, but social science should not presume

that the human species is superior to other life forms.As

social scientistswe should focus

on the human species without making any presumptions about the value of

that species for good or ill.Some

scientists study amphibians and others study humans.

Humanism

And Values

But

that is not all. In addition to being scientists we are citizens, as well

as members of families and communities. Every scientist is also these other

things, and good social science can be helpful for pursuing the goals that

are associated with these other roles.The

idea here is that each of us plays more than one game, and we need to be

clear about which rules are which.A

person who is a social scientist during the day is a parentand

a citizen by night – s/he wears more than one hat. But the operations of

one game may have implications for another.

The

main focus of this book is to present the best current practices of the

science of social change, but in the final chapter we will go beyond social

science to suggest how what we know might be used to bring about a more

humane and sustainable world society.As

a citizen I am a humanist, so I will affirm that the survival of the human

species is a desirable goal.This

does not contradict what I have said above about my scientific goals.My

political and social valuesare choices

and commitments that I have made, and I recognize that these cannot be

proven by science.But science may

provide useful information for realizing political and philosophical goals.

Indeed almost all modern political philosophies make appeals to science

for support of their views of human nature and the possibilities for human

society.The important thing here

is to not put the cart before the horse.In

this text the science is first.

(drawing

of person with two hats: one says “scientist,” the other “humanist”)

Science

need not claim to be the only valid perspective on ultimate reality. In

asserting the value of the scientific approach against religious systems

of thought early scientists often took an arrogant stance that belittled

other approaches to reality. Now that science itself is the main religion

of the emerging global culture a more agnostic and tolerant philosophical

stance is desirable, though this need not go to the extremes of cultural

relativism and subjectivism advocated by many of the postmodernists.Science

can be modest and useful without the arrogance of scientism.

(sketch

of person with two hats: one says “scientist,” the other says “humanist”)

The

Comparative Method

All

science is based on the comparative method in the sense thatcausality

is inferredby comparing sequences

of events. When it is possible to manipulate the processes under study

scientists do true experiments because causal inferences can be made more

reliable by isolating and simplifying the operation of variables.If

we want to know whether A causes X we can experimentally manipulate A and

see what happens to X and isolate X from other influences. In most of social

science it is not feasible to carry out true experiments, but we can still

employ the logic of the experimental method in order to make inferences

about causality.Thus we design our

research as if we were manipulating variables and we look for opportunities

in nature in which processes seem to be simplified and isolated.We

measure variables A and X and see if, in the course of events,a

change in A seems to regularly correspond with a change in X.Or

we observe a number of comparable cases and see if there is a patterned

relationship between A and X that might indicate causality. We can also

measurevariation in other variables

to try to infer how they may be involved in the relationship between A

and X.

The

comparative method allows us to infer causality, albeit with varying degrees

of certitude.We choose comparable

cases or instances of the processes of social change we care about, and

then we measure the variables that we think are causing the main (dependent)

variable of interest, and we test causal propositions by studying variation

over space or time (or both).Whether

we study one case over time or several comparable cases we are employing

the comparative method and the strategy of quasi-experimental research

design.

Figure

1.1:Does A Cause X?

We

use probabilistic logic rather than deterministic logic in our models of

social change.A probabilistic statement

says that A is likely to cause X a certain percentage of the time. There

is an explicit element of randomness or indeterminacy.A

deterministic statement says that A always causes X.We

use probabilistic logic for two reasons:

1. because

there is usually error in our measurements of variables, and

2. because

social action is itself probabilistic rather than deterministic.

Thus

we do not speak of “laws” of social change, but rather of causal tendencies.

Probabilistic

logic is also used in much of natural science, but it is even more important

to use it in social science because we are trying to predict and explain

the behavior of intelligent beings.The

amount of indeterminacy in the behavior of a billiard ball is considerably

less than the amount of indeterminacy in the behavior of a person.If

you tell a billiard ball your prediction of the path it will take after

bouncing off the side of the pool table, your statement cannot affect the

behavior of the ball. But if you tell a voter that she is likely to vote

for the Bullmouse Party your prediction may influence her decision. Intelligent

beings are difficult subjects of scientific study. We need to take these

special problems into account in our efforts to explain and predict what

humans do.So we use probabilistic

statements and we try to comprehend the ways in which our subjects interpret

their own worlds.

Types

of Evidence

The

evidence that we use to study social change over the long run is of several

different kinds.For studying people

who lived before the invention of writing we use archaeological evidence

– the remains of peoples’ lives as found in artifacts, evidence of what

they ate, how they constructed their habitations, the sizes of settlements.

The ability to accurately date artifacts is an important method for understanding

sequences of development and what was going on at the same time in different

regions.We can often infer a great

deal about patterns of trade and interaction from the distributions of

artifacts for which the original sites of procurement can be determined.

For example, volcanic glass (obsidian) can be chemically “finger-printed”

so that it is possible to know that a particular obsidian arrowhead originally

came from a quarry far from where the arrowhead was found.By

studying the composition of arrowheads at a site we can see how trade and

procurement patterns changed over time. We can sometimes find archaeological

evidence of proto-money, the use of certain trade items as generalized

media of exchange.Archaeological

evidence cannot tell us directly about what people thought or felt, but

we can make educated guesses about their social organization based on the

remnants that human occupation leaves.

Ethnographic

evidence is that information that has been gathered by anthropologists

who have studied people who live in less complex societies that survived

until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.The

ethnographers moved in with the remaining hunter-gatherers and tribal peoples

of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to study their languages, and

their material and ideological cultures.The

greatest use of this corpus of evidence for the study of social evolution

is the light that it sheds on the lives of people who lived thousands of

years ago, but it is important to realize that hunter-gatherers who managed

to survive until recently may not accurately represent of hunter-gatherers

who lived long ago.Obviously those

who have been long in contact with more complex societies are likely to

have adapted to these interactions in important ways that change the nature

of their institutions.The usage

of ethnographic evidence to supplement archaeological evidence needs to

be cautious regarding this problem.

It

is often possible to use the written observations and records made by the

first literate observers of preliterate peoples (missionaries, etc), though

these sources of information are usually heavily biased by the civilizational

perspectives of the observers. Once societies have developed writing we

can decipher their own written records and documents as sources of evidence

about social institutions and practices. The firstwritten

languages emerged along with the original invention of states in Mesopotamia

about 5000 years ago.Records and

documents were written on clay tablets that preserve rather well under

dry conditions. Ironically, the development of papyrus documents in later

millennia created a larger hole in the evidence because papyrus is more

fragile than clay tablets. Our documentary knowledge of the great Persian

Empire of the Achaeminids is largely confined to epigraphs, inscriptions

on stone monuments, because the papyrus documents have decayed.We

use documentary evidence in conjunction with archaeological evidenceto

gain an understanding of the early civilizations. We also see the development

of formal systems of money and can infer much about ancient economies and

polities by studying coinage.

Ancient

states began to gather systematic evidence about their own finances and

the populations under their control. This evolved into the modern system

of statistics,censuses and national

accounts that we use as evidence of social change. Sample surveys and systematic

studies of large populations allow us to be much more thorough andprecise

about social changes that have occurred in the last half century.We

can now use satellite data to study large-scale social processes such as

urbanization and global deforestation.

Social

Evolution

Social

evolution is most simply the idea that social change is patterned and directional

– that human societies have evolved from small and simple affairs to large

and complex ones. The idea of social evolution has had a rough career in

social science and it is still in disrepute in some circles. Part of the

problem has been that earlier formulations of the idea embodied certainassumptions

that are unscientific in nature. The idea that some human societies are

superior to others because they are “more advanced”has

been used as a justification by some people for dominating and exploiting

others. The social evolutionism of the British anthropologists of the nineteenth

century presented London society as the highest form of civilization and

depicted colonized peoples as savages and barbarians. Evolutionary ideas

were used to support a philosophy of social Darwinism in which the current

winners were depicted as better adapted and loserswere

portrayed as on the way to extinction because of genetic and/or cultural

deficiencies. More recently Talcott Parsons’s (1966) version of structural/functional

evolution presented the United States in a similar light.

In

reaction to these problems many social scientists embraced a radical cultural

relativism in which each society was understood as a unique constellation

of institutional practices.It was

assumed that there were no inherently superior social structures, but rather

that all human cultures were equal, though different from one another.

The ethnographer Franz Boas was the greatest proponent of this approach

and modern anthropology was heavily influenced by his stress on careful

fieldwork that recorded the linguistic, spiritual and material attributes

of human societies.The ethnographic

corpus produced by following Boas’sapproach

is a vast resource for our knowledge of ways of life different from our

own despite the cultural biases and problems of objectivity of those who

have “tented with the natives.”But

the rejection of social evolutionism has ebbed as the elements that made

it obnoxious have been separated from the more basic notions of patterned

and directional change (Sanderson 1990).

There were three main problems with social evolutionary thinking thatneeded to be rectified:

1.Social evolution is easilyconfused with biological evolution, and yet these are largely distinct and different processes.

2.Evolutionary thinking has tended to involve teleological assumptions in which the purposes of things have been asserted to be their cause.

3.Evolution has been confused with the idea of progress – the notion that things are getting better.

Social

vs. Biological Evolution

Social

evolution and biological evolution are different processes, though they

share some similar characteristics.Confusing

these processes causes great misunderstanding and facilitates theoretical

reductionism in which social science is subsumed as a sub-branch of biology.While

biological evolution is based on the inheritance of genetic material, social

evolution is based on the development of cultural inventions.Both

genes and cultural codes are information storage devices by which the experiences

and outcomes of one generation are passed to future generations.Social

evolution did not exist before the invention of culture.Animals

that do not have the biological ability to manipulate symbols and to communicate

them do not experience the process of social evolution.The

human animal is uniquely equipped to evolve socially because of the presence

of the relatively large unpreprogrammedcortex

of the human brain. This unusual piece of equipment makes possible the

learning of complex codes and their infinite recombination.

Humans

have a lot of RAM relative to ROM, whereas non-human animals have more

ROM than RAM. In computers RAM is RANDOM ACCESS MEMORY that can contain

changeable software, whereas ROM is READ-ONLY MEMORY that is permanently

programmed at birth. This is another way of saying that humans are less

instinctual than non-humans.Ants

live in large and complex societies, but their behavior in these is largely

instinctive. Their social structures are hard-wired, and the architecture

of their mounds is rigidly bound by theinstinctive

behaviors of mound-building. Humans learn the cultural software that enables

them to build large and complex societies and the plan is coded in language

and blueprints that may be modified without having to wait for the evolution

of new instinctive behaviors.Language

itself has an instinctive basis and this is why speakers of all natural

languages share a somewhat similar grammatical structure. But this biological

ability makes possible the great variation that we see in meaning systems

and social institutions.

When

nomadic hunters developedstone tools

they obviated the need to genetically select for carnivorous teeth.Thus

cultural evolution allowed humans to occupy new niches and to adapt in

new ways without waiting for biological evolution. This slowed down the

rate of already-slow biological evolution of human genes.

The

similarities between biological evolution and social evolution are these:

·both

rely on information storage to pass the experiences of one generation on

to another;

·both

are mechanisms whereby individuals and groups adapt to changing environments

or exploit new environments;

·in

both more adaptive changes drive out less adaptive characteristics through

competition.

·And

there is onemore similarity. In

both biological and social evolution more

complex systems develop out of simpler systems.

There

are, however, rather large and important differences between biological

and social evolution:

·In

biological evolution the source of innovations is the random process of

genetic mutation, while in social evolution recombinations and innovations

occur intentionally as people try to solve problems.This

is not to say that social evolution is entirely rational or even intentional,

because many social changes occur as the unintended consequences of the

actions of many individuals and groups. But the important point here is

that, compared with genetic mutation, social innovation contains an important

element of intentionality.

·The

second big difference is in the rate of change. Biological evolution takes

a long time, while social evolution is much faster and is accelerating.

Biological evolution occurs slowly because it is dependent on mating and

reproduction and on those few unusual genetic mutations that are adaptive.Social

evolution is accomplished by means of cultural inventions, and these can

spread from group to group. Societies

can “mate” and exchange cultural material, whereas species cannot exchange

genetic material.

·Another

important difference is in the relationship between simpler and more complex

forms.In biological evolution simple

one-celled forms of life co-evolve along with more complex multi-celled

organisms.Indeed, they seem to thrive.

Viruses and bacteria are doing just fine. In social evolution the situation

is vastly different. Small scale societies get wiped out by larger societies.

There is not co-evolution of small and large. Rather states and empires

destroy stateless societies(.e.g

hunter-gatherer bands) by either killing off their members or by assimilating

them into state-based societies, or both.The

history of the indigenous Americans is a case at hand.Anthropologists

have termed this the “law of cultural dominance.”It

is not anatural law in the sense

that it is impossible for more powerful cultures to allow less powerful

ones to survive, but this has not happened to any appreciable extent.

So

cultural and biological evolution are quite different processes, and it

is important to understand this distinction because the word “evolution”

is often used in ways thatcause

confusion.Many of the claims of

sociobiology and evolutionary behaviorism are exaggerations of the extent

to which human actions are instinctive and based on biological evolution.

The idea of human nature is itself a culturally constructed notion that

has powerful effects in legitimating social institutions.And

yet, to argue that human behavior is less instinctive than the behavior

of other animals does not require that we deny the biological basis of

human actions. There are clearly constraints, as well as possibilities,

that emanate from our bowels and our brain-stems.But

social and cultural evolution has radically reconstructed these constraints.

Regarding

the relationship between biological and social evolution, it is obvious

that there would have been no cultural evolution if the human species had

not evolved the ability to speak and a brain capable of storing and reconfiguring

complex codes and symbols.These

were the key developments that allowed culture to emerge.Once

culture emergedit acted back upon

biological evolution.Social structure

has taken over as a main source of influence over which humans and otherlife

forms survive and prevail. Domestication of certain animals and plants,

selective breeding, and now the development of genetic surgery, cloning

and genetic engineering have massively affectedbiological

evolution on Earth, and this impact will only become greater if the human

species survives its own experiments.

Teleology

and Unilinear Evolution

Teleology

is a form of explanation in which the purpose of a thing is alleged to

be its cause.The most famous teleological

explanation is that order in the universe is a consequence of the will

of God. Aristotle contended that all of nature reflects the purposes of

an immanent final cause.The problem

is that general purposes of the universe cannot be scientifically demonstrated

to exist. Science is limited to knowledge of proximate causation. The causes

of a thing must be demonstrably present or absent in conjunction with the

presence or absence of the thing to be causally explained.Proving

causality requires variation. General statements about characteristics

of the universe that are invariably present cannot serve as scientifically

knowable causes precisely because they do not vary.

A

related unscientific characterization of historical processes is inevitabilism

or the idea that history is the result of an unfolding process in which

stages follow one from another in a necessary order, like the pages of

a book.Another term for this kind

of theory is unilinear evolution.Much

of the rhetorical power of Marxism came from the stage theory of history

which alleged that socialism and communism would inevitably supersede capitalism.

Thus hard-working revolutionaries could claim to have history on their

side.Now, ironically, Marxism has

itself been thrown into the dustbin of history and the ideologues of capitalism

claim that socialism is an outdated ideology that was produced by the strains

of transition from traditional to modern society and global capitalism.

All stage theories need to be treated with skepticism, but this does not

mean that we should abandon the effort to see the patterns of social change.

The

probabilistic approach to social change outlined above disputes the scientific

validity of inevitabilism or unilinear evolution. This is not the same

as arguing that there are no directional patterns of social change or that

all outcomes are equally probable. But it is important to know that scientific

social change theory is about probabilities,not

inevitabilities.Social evolution

has not been a process in which a single society goes through a set of

stages to arrive at the most developed point. It has been uneven in space

and time. Societies that are at the highest level of complexity at one

point often collapse and the emergence of larger, more hierarchical and

more complex societies occurs elsewhere.Indeed,

this uneven pattern is one of the most important processes in the evolution

of world-systems.

A

scientific approach to social evolution does not assert final causes or

ultimate purposes. It proposes causal propositions that are empirically

testable and falsifiable with evidence about human history and social change.Neither

does social evolution claim that particular outcomes are inevitable.Contingency

and unexpected events can alter the course of human history fundamentally.

The fate of the dinosaurs, probably destroyed by the impact on Earth of

a large asteroid, powerfully reminds us about the potential importance

of unexpected events that come from elsewhere. But this should not prevent

us from trying to see the more likely patterns of development in both the

past and the future, or the trajectories that social change will take in

the absence of catastrophic events.

Progress

and Social Evolution

Progress

is not a scientific idea in itself because it involves evaluations of the

human condition that are necessarily matters of values and ethics.The

idea that a world populated by humans is better than a world in which they

are absent is an esthetic or ethical matter of choice.Even

the idea that warm and well-fed humans are better off than cold and hungry

ones, or that long, healthy life is better than shortdisease-ridden

existence --these too are value

choices, albeit ones that would be widely agreed upon by most people. When

we turn to matters of religion,family

form, cuisine, or the ideal degree of social equality it is more obvious

that we have entered the world of value decisions.One

of the biggest problems with many theories of social evolution is that

they have tended to be permeated with assumptions about what is better

and worse and many have simply assumed that evolution itself is a movement

from worse to better.And with this

powerful element embedded in them evolutionary theories have served as

potent justifications of conquest, domination and exploitation. We have

already pointed out that this problem was the main one that led the second

generation of anthropologists to reject social evolutionism in favor of

a strong dose of cultural relativism.

Theories

of progress are still important ideological elementsin

the world of politics, and so ideas about social evolution are still susceptible

to being used badly. But so are other products of science and humanistic

endeavor.Physicists are painfully

aware of how the knowledge they have produced has been turned into the

threat of nuclear holocaust.Historians,

even those who studiously avoid makinggeneralizations

about the human predicament, may find their interpretations of historical

events turned to uses of which they disapprove.Neither

scientists nor humanists can control the usage to which their works are

put.

This

said, if we agree on a list of desirable ends that constitute our notion

of human progress, then it can be a scientific question as whether things

have improved with respect to this list, or which kind of society does

better at producing the designated valuables.The

list is one of preferences, not scientifically determinable, but philosophically

chosen. This list may be my personal preferences, or some collectively

agreed upon set of preferences. This approach to the problem of progresswill

be considered near the end of this book when we ask about the implications

of our study of social change for world citizens.

The

notion that it is plausible to formulate general theories of social evolution

is given credence by the observation that many instances of parallel evolution

have occurred. Parallel evolution means that similar developments emerge

under similar circumstances, but largely independently of one another.If

horticulture (planting) had only been invented once and then had diffused

from its single place of invention it might be argued that this was merely

a fortuitous accident. But horticulture was invented independently several

times in regions far from one another. Similarly states and empires emerged

in both the Eastern and Western hemispheres with little interaction between

the two despite that the emergence of states in the Western hemisphere

occurred some three millennia later than in the Eastern. It is also quite

likely that the emergence of states in East Asia, near the bend of the

Yellow River in what is now China, occurred largely independently of the

earlier emergence of states in West Asia, in the region that we call Mesopotamia

(now Iraq). The significance of important instances of parallel social

evolution is that they imply that general forces of social change are operating.

Our task is to determine with evidence which conditions and tendencies

were the most important causes of these developments.

Idiographic

Historicism vs. Nomothetic Ahistoricism

Before

we present an overview of different theoretical approaches to social change

we need to examine a long-standing controversy in the philosophy of social

science.Social scientists have long

argued over the degree to which human society and human behavior can be

scientifically explained and predicted. At the extremes are two antithetical

stances.Some argue that human beings

are so smart and societies are so complex that scientific explanation and

prediction by means of general laws is impossible. The only thing that

can be done from this perspective is to interpret the meaning of particular

historical events or conjunctures because meaningful generalization across

different situations is impossible.This

so-called “idiographic” approach records detailed descriptions of settings

or events and tries to understand and evoke the mentalities of the participants.This

approach often presumes that efforts to develop a transhistorical species-wide

science of human behavior and human societies are doomed to fail and theories

that claim to be scientifically universalistic are only sham fig-leaves

that are used by the powerful to legitimate their privileges. Extreme historicism,

in this meaning, is the position that every village and every human event

are unique instances that cannot be meaningfully compared with other instances.

The

other extreme position claims that social science is basically like physics.

It is possible to discover a set of universal laws that explain human behavior

and the nature of all human societies.While

nobody claims that this has already been accomplished, the historical trajectory

of social science over the past 200 years is seen by ahistoricistsas

progress toward the development of“nomothetic,”

or law-like, theories of social change.Perhaps

the sociological theory that is closestto

extreme ahistoricism is the structural functionalism of Talcott Parsons

(1966), in which all societies are understood as systems of social actors

having the same basic set of functional prerequisites.

In

practice there are few social scientists that occupy either of the extreme

stances. But many historians are partial to the idiographic stance, while

it is usually sociologists,political

scientists or anthropologists who are sympathetic to the goals of general

explanation.Most practitioners combine

the insights of the extreme positions into a stance that contains elements

of both, but in this they differ as to emphasis.It

is useful to imagine a continuum with idiographic historicism at one end

and nomothetic ahistoricism at the other (See Figure 1.2)

It

is not necessary to assert that all human behavior is equally amenable

to scientific explanation. There may be whole sectors of human action that

are quite conjunctural and extremely path dependent, in which causality

is so complex and interactive that simplifications of the usual sort employed

in scientific models are incapable of representing reality.Acknowledging

that architectural fashions or literary trends are beyond scientific prediction

does not require us to believe that there are no important causal tendencies

in the processes of economic and political development.Scholars

not only differ with respect to their location on the nomothetic/idiographic

continuum, but they also differ with regard to which aspects of social

reality they see as more patterned versus those that are understood as

primarily conjunctural or unpredictable.

Theories

of Social Change

Theories

of long-term social change differ from one another in two basic ways. One

is the extent to which they posit qualitative as opposed to merely quantitative

change. And the other is the extent to which they emphasize a single master

variable that is allegedly the main cause of change.

Some

theories posit a single logic of social change that is thought to adequately

describe the important processes in all types of human societies and in

all periods of time. Others argue that the logic of social change has itself

altered qualitatively, and so that a model that explains, for example,

the emergence of horticulture, is not adequate for explaining the emergence

of capitalism.Those who see long-run

continuities of developmental logic are called “continuationists,” while

those who posit the existence of fundamental reorganizations of the logic

of social change are called “transformationists.”Continuationists

contend that similar processes of social change have operated for millennia,

while transformationists see qualitative reorganizations of the processes

of change as having occured. The content of the models within each of these

categories is quite variable depending on what sorts of social change are

seen as most central or powerful – the master variables.

The

master variables can be broadly categorized as either cultural or material,

but within each of these two boxes there are several significant subtypes.Culturalists

often emphasize the importance of the ways in which values are constructed

in human societies, and so they focus on religion or the most central institutions

that indicate the consensual and most powerful value commitments of a society.

From this point of view the most important kind of social change involves

redefinition of what is alleged to exist (ontology), and changes in ideas

about good and evil.Social evolution

is understood by culturalists as the reorganization of socially institutionalized

beliefs. For example,the important

changes in social evolution are understood to have been the transitions

from the animistic philosophy of the hunter-gatherer band to the radical

separation of the natural and supernatural realms in early states, and

then the rise of the “world religions,” followed

by the emergence of formal rationality and science – the dominant “religion”

of the modern world.Other social

changes are seen by culturalists as down stream from these most fundamental

transformations of ideational culture.

Materialists

focus primarily on the material problems that all human societies face

and the inventions that people employ to solve these problems. They note

that humans must eat and that in order for human groups to survive they

must provide enough food and shelter to allow babies to be born and to

grow up.Thus all human societies

face demographic and economic problems, and the ways in which these problems

are solved are important determinants of other aspects of social life.Materialists

assertthat human societies need

to adapt to the natural environment and to the larger social environment

in which they compete and cooperate with other human societies.Materialists

often differ as to which material problem is seen as most crucial and determinant.

Some emphasize demographic and ecological constraints, while others focus

on technologies of production or of power.Technologies

of production are those techniques and practices by which resources are

acquired or produced from the natural environment.Technologies

of power are those institutions that create and sustain hierarchies within

human societies and that allow some societies to conquer and dominate other

societies.

Institutional

Materialism

The

theoretical approach employed hereis

termed “institutional materialism.” It is a synthetic and flexible combination

of culturalist and materialist approaches that sees human social evolution

as produced by an interaction among demographic, ecological and economic

forces and constraints that is expanded and modified by the institutional

inventions that people devise to solve problems and to overcome constraints.Institutional

inventions include ideological constructions such as religion as well as

technologies of production and power.Technologies

of production are such things as bows and arrows, the potter’s wheel and

hydroelectric dams. Technologies of power are such things as secret societies,

special bodies of armed men, methods of keeping records of who has paid

taxes, tithes or tribute, as well as intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Solving

problems at one level usually leads to the emergence of new problems, and

so the basic constraints are never really overcome, at least so far.Institutional

materialism sees a geographical widening of the scale of ecological and

social problems created by social evolution rather than a transcendence

of material constraints.This is

what allows us to construct asingle

basic model that represents the major forces that have shaped social evolution

over the last twelve millennia.

As

mentioned above, institutions are inventions that are made by people for

solving problems. Much of the taken for granted aspects of our world are

composed of institutions that have been socially constructed by people

in the past. Thus we all learn a language when we are children, a particular

language with particular meanings and connotations.Our

mother-tongues are social constructions of people who spoke and made meaning

in the past, including those who raised us and those who taught them. Our

particular languages are central institutions that heavily influence our

understanding of what exists, what is possible, what is good and what is

evil.Other institutions that are

historical inventions are money, the family and productive technology.

Institutions

in the sociological sense are more than just hospitals or schools. They

are all the socially constructed and taken for granted aspects of everyday

life, including who we think we are and what we think exists. The self,

in the sense of our idea of our individual identity and what we think human

nature is,is an institution in this

sense.Institutional materialism

analyzes the interactions between the material aspects and necessities

of human life and the invention of culturally constructed institutions.

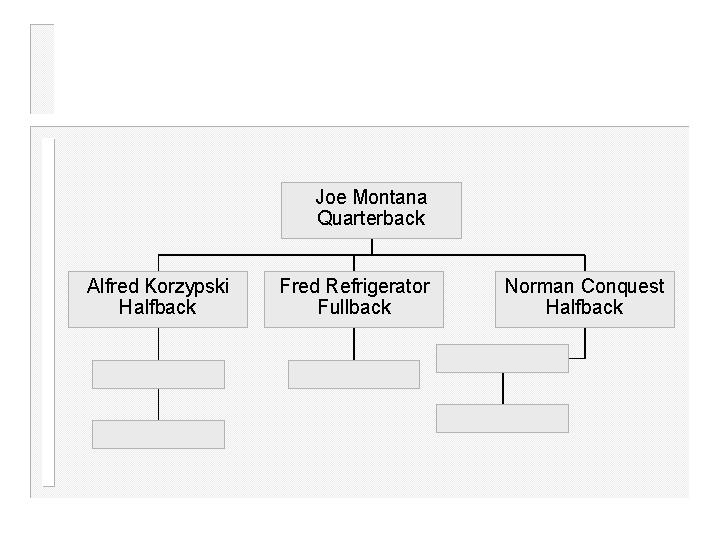

Social

structure is the main focus for the study of social change. Individuals

are born and die and so all societies are composed of structures in which

individuals either reproduce institutions in much the way that they have

been in the past, or they alter these institutions. The easiest way of

conceptualizing social structure is as an organizational chart in which

the various positions that constitute the organization are shown along

with their relationships with one another.

All

formal organizations and bureaucracies are explicitly conceptualized as

constellations of social positions (statuses) in which different individuals

occupy the various positions. So a football team has a quarterback, and

a halfback and a center and etc. Specific duties are assigned to these

positions, and a particular player is evaluated in terms of how well or

poorly he or she carries out the duties associated with the position.Sociologists

point out that informal as well as formal groups may be viewed as having

social structures.A group of friends

having lunch may be understood as performing certain scripts appropriate

to equals who care about one another, with a degree of improvisation thrown

in to constitute genuineness and agency.All

social groups are constituted in this way as organizations with rules and

assumptions.

This

structural view of human society focuses on the rules and definitions that

provide the boundaries within which individuals carry out and reproduce

social structures.But these structures

also change, and the study of social change is, in large part, the effort

to explain why structures change in the way that they do.

Social

structures are held together by three basic kinds of institutional “glue.”Social

order is produced by institutions that make human behavior somewhat predictable.In

order to compete, fight or cooperate with others I need to be able to guess

what they will do in reaction to what I do.There

are three basic institutional inventions that facilitate relatively stable

expectations about the behavior of others:

1.normative

regulation in which people agree about the proper kinds of behavior,

2.coercive

regulation in which institutionalized sanctions are applied to discourage

behavior that is considered to be inappropriate;

3.market

regulation in which individuals are expected to maximize their returns

in competitive buying and selling.

Normative

regulation based on consensus about proper behavior is the original institution

of social order. It requires

a shared language and a good deal of consensus about basic values and proper

behavior. Individuals learn the rules and internalize them and regulate

themselves and others with appeals to the moral order. This works well

in small societies in which people interact with one another frequently

and on a relatively egalitarian basis.Itworks

less well (by itself) in larger societies that require that culturally

different and spatially separated peoples cooperate with one another.

Coercive

institutions (but not coercion) were invented with the rise of social hierarchies.Institutions

such as the law do not require that each individual know or agree with

the law. Thus they work better for integrating communities that do not

share common cultures and moral orders. Legal

regulation is backed up by legitimate violence, the right of the lord or

the king to enforce the law by means of punishment and prisons. Special

bodies of armed men are used to enforce decisions made by states, as well

as to engage in conflict with other societies. Courts

are part of institutionalization of coercion as an important form of social

regulations.

Market

regulation emerged even more recently with the invention of money and commodities.

Market regulation, like institutionalized coercion, does have a basis in

presumed norms, but these norms themselves only provide the framework for

interaction. They do not require agreement about much, except that money

is useful.Markets articulate the

actions of large numbers of buyers and sellers without requiring these

players to identify with one another or even to agree about the general

rules of legality.Markets are institutions

that allow for relatively peaceful cooperation and competition among peoples

that are spread over wide distances and who have rather different cultures.

Much

of the sociology of roles, statuses and social structure is based on the

assumption that normative regulation is operating, but many social structures

operate in the absence of much consensus because they are regulated by

coercive or marketinstitutions.The

invention of these institutional forms of regulation have made organized

social interaction possible on a greater and greater spatial scale until

now we have a single global network in which all three kinds of regulation

play important parts.The story of

how these inventions came about is central focus of the study of social

evolution.

The

structuralist approach that is an important part of institutional materialism

is not, contrary to what some critics have alleged, a necessarily deterministic

approach to social life that eliminates the possibility of human freedom.

Institutional structuralism allows us to understand the constraints that

our own cultures have placed upon us so that, to some degree, we can transcend

these constraints.We see socially

constructed institutions as human inventions that both empower us and constrain

us in certain ways. The fact that the U.S. government has purchased, graded

and maintained a piece of property that is 3000 miles long and 200 feet

widemakes it possible for me to

drive from Baltimore to San Francisco in less than three days, while my

ancestors took three months to make the same trip.This

is technological and institutional empowerment.But

the same Interstate highway system means that the U.S. has invested a huge

amount of money, energy, property and human labor into a particular kind

of transportation network that might become obsolete due to some future

change in technology or in the cost of energy. The canals of Venice or

Amsterdam represent sunk costs that could not easily be reconstructed when

transportation technology changed.Our

religions, the ways in which we have defined male and femaleness, the huge

psychic investments in nationalistic sentiments, the expensive rituals

by which we demonstrate our commitments to some people and our enmities

to others -- all these institutionalized aspects of our society make it

possible for us to do some things, and very difficult to do others.This

is empowerment and structural alienation.The

analysis of institutional structures makes it possible to understand how

our history has constructed us and what we may need to do to reconstruct

the future.

Institutional

materialism is an synthetic and eclectic theoretical focus that draws from

several social science disciplines: history, anthropology, sociology, political

science, economics, demography and geography. This

will be combined with social geography as it has emerged from the comparative

world-systems perspective, the main topic of the next chapter.These

tools will help us to see the broad patterns as well as the unique aspects

of different kinds of societies in the process of social evolution.