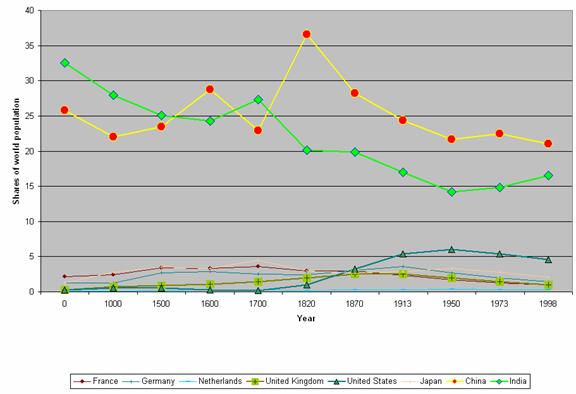

Hnpg009 Course readings

Fall, 2008

“Learning,

Leadership and Creativity”

v. 9-3-08, 15787 words

*W.

Warren Wagar 1999 A Short History of the

Future. (3nd Edition)

# 1 Thomas D. Hall and Christopher Chase-Dunn,

2006 “Global social change in the long run” Chapter 3 in C. Chase-Dunn and S.

Babones (eds.) Global Social Change.

#2 Christopher Chase-Dunn and Bruce Lerro, Social Change, Chapter 14 “The Modern

World-System” (Pp. 22-37 below).

#3 Christopher Chase-Dunn and Bruce Lerro, Social Change, Chapter 19 “The

World-System Since 1945” (Pp. 38-58 below).

#4 Christopher

Chase-Dunn, A. K. Jorgenson, T.E. Reifer and S. Lio 2005 “The trajectory of the

# 5 Volker Bornschier 2008 “Income inequality in

the world: looking back and ahead” Presented at the conference on “Inequality

Beyond Globalization” organized by the World Society Foundation and the RC02 of

the International Sociological Association, University of Neuchatel, June 28,

2008. (Pp. 80- 96 below).

“Global Social Change in the Long Run”

Thomas D. Hall and Chris Chase-Dunn, Chapter 3 in Global Social Change, C. Chase-Dunn and

S. Babones (eds.)

The comparative world-systems perspective is a strategy for explaining human socio-cultural evolution that focuses on whole intersocietal systems rather than single societies. The main insight is that important interaction networks (trade, information flows, alliances, and fighting) have woven polities and cultures together since the beginning of human social evolution. Explanations of social change need to take intersocietal systems (world-systems) as the units that evolve. But intersocietal interaction networks were rather small when transportation was mainly a matter of hiking with a pack. Globalization, in the sense of the expansion and intensification of larger interaction networks, has been increasing for millennia, albeit unevenly and in waves.

World-systems are systems of societies. Systemness means that these societies are interacting with one another in important ways – interactions are two-way, necessary, structured, regularized and reproductive. Systemic interconnectedness exists when interactions importantly influence the lives of people within societies, and are consequential for social continuity or social change. World-systems may not cover the entire surface of the planet. Some extend over only parts of the Earth. The word “world” refers to the importantly connected interaction networks in which people live, whether these are spatially small or large.

Only the modern world-system has become a global (Earth-wide) system composed of national societies and their states. It is a single economy composed of international trade and capital flows, transnational corporations that produce products on several continents, as well as all the economic transactions that occur within countries and at local levels. The whole world-system is more than just international relations. It is the whole system of human interactions. The world economy is all the economic interactions of all the people on Earth, not just international trade and investment.

The modern world-system is structured politically as an interstate system – a system of competing and allying states. Political Scientists commonly call this the international system, and it is the main focus of the field of International Relations. Some of these states are much more powerful than others, but the main organizational feature of the world political system is that it is multicentric. There is no world state. Rather there is a system of states. This is a fundamentally important feature of the modern system and of many earlier regional world-systems as well.

When we discuss and compare different kinds of world-systems it is important to use concepts that are applicable to all of them. Polity is a more general term that means any organization with a single authority that claims sovereign control over a territory or a group of people. Polities include bands, tribes and chiefdoms as well as states. All world-systems are politically composed of multiple interacting polities. Thus we can fruitfully compare the modern interstate system with earlier systems in which there were tribes or chiefdoms, but no states.

In the modern world-system it is important to distinguish between nations and states. Nations are groups of people who share a common culture and a common language. Co-nationals identify with one another as members of a group with a shared history, similar food preferences and ideas of proper behavior. To a varying extent nations constitute a community of people who are willing to make sacrifices for one another. States are formal organizations such as bureaucracies that exercise and control legitimate violence within a specific territory. Some states in the modern world-system are nation-states in which a single nation has its own state. But others are multinational states in which more than one nation is controlled by the same state. Ethnic groups are sub-nations, usually minorities within states in which there is a larger national group. Ethnic groups and nations are sociologically similar in that they are both groups of people who identify with one another and share a common culture, but they often differ with regard to their relationship with states. Ethnic groups are minorities, whereas nations are majorities within a state.

The modern world-system is also

importantly structured as a core/periphery hierarchy in which some regions

contain economically and militarily powerful states while other regions contain

polities that are much less powerful and less developed. The countries that are

called “advanced ” (in the sense that they have high levels of economic

development, skilled labor forces, high levels of income and powerful,

well-financed states) are the core powers of the modern system. The modern core

includes the

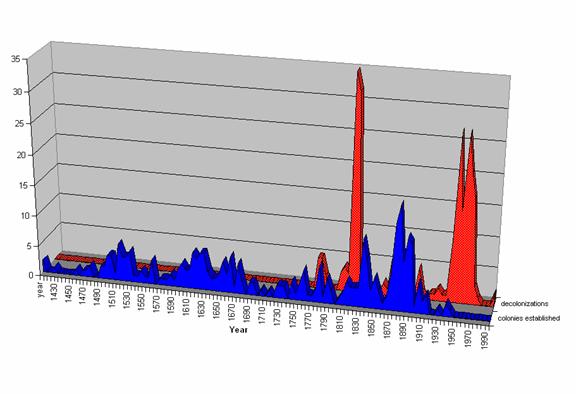

In the contemporary periphery

we have relatively weak states that are not strongly supported by the

populations within them, and have little power relative to other states in the

system. The colonial empires of the European core states have dominated most of

the modern periphery until recently. These colonial empires have undergone

decolonization. The interstate system of formally sovereign states was extended

to the periphery in a series of waves of decolonization that began in the last

quarter of the eighteenth century with the American independence. This was

follow in the early nineteenth century by the independence of the Spanish

American colonies, and in the twentieth century by the decolonization of Asia

and

In the past, peripheral countries have been primarily

exporters of agricultural and mineral raw materials. But even when they have

developed some industrial production, this has usually been less capital

intensive and using less skilled labor than production processes in the core.

The contemporary peripheral countries are most of the countries in Asia, Africa

and Latin America – for example

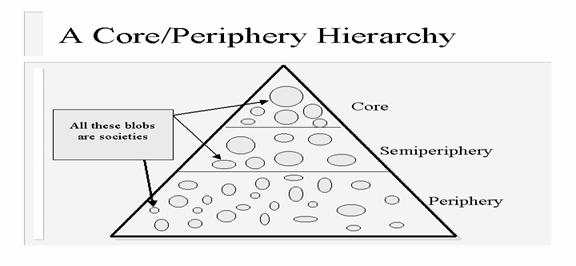

The core/periphery hierarchy in the modern world-system is a system of stratification in which socially structured inequalities are reproduced by the institutional features of the system (see Figure 1). The periphery is not “catching up” with the core. Rather both core and peripheral regions are developing, but most core states are staying well ahead of most peripheral states. There is also a stratum of countries that are in between the core and the periphery that we call the semiperiphery. The semiperiphery in the modern system includes countries that have intermediate levels of economic development or a balanced mix of developed and less developed regions. The semiperiphery includes large countries that have political/military power as a result of their large size, and smaller countries that are relatively more developed than those in the periphery.

Figure 1. Core/Periphery Hierarchy

The exact boundaries between the core, semiperiphery and periphery are unimportant because the main point is that there is a continuum of economic and political/military power that constitutes the core-periphery hierarchy. It does not matter exactly where we draw lines across this continuum in order to categorize countries. Indeed we could as well make four or seven categories instead of three. The categories are only a convenient terminology for pointing to the fact of international inequality and for indicating that the middle of this hierarchy may be an important location for processes of social change.

There have been a few cases of

upward and downward mobility in the core/periphery hierarchy, though most

countries simply run hard to stay in the same relative positions that they have

long had. A most spectacular case of upward mobility is the

The global stratification system is a continuum of economic and political-military power that is reproduced by the normal operations of the system. In such a hierarchy there are countries that are difficult to categorize. For example, most oil-exporting countries have very high levels of GNP per capita, but their economies do not produce high technology products that are typical of core countries. They have wealth but not development. The point here is that the categories (core, periphery and semiperiphery) are just a convenient set of terms for pointing to different locations on a continuous and multidimensional hierarchy of power. It is not necessary to have each case fit neatly into a box. The boxes are only conceptual tools for analyzing the unequal distribution of power among countries.

When we use the idea of core/periphery relations for comparing very different kinds of world-systems we need to broaden the concept a bit and to make an important distinction (see below). But the most important point is that we should not assume that all world-systems have core/periphery hierarchies just because the modern system does. It should be an empirical question in each case as to whether core/periphery relations exist. Not assuming that world-systems have core/periphery structures allows us to compare very different kinds of systems and to study how core/periphery hierarchies themselves emerged and evolved.

In order to do this it is helpful

to distinguish between core/periphery differentiation and core/periphery

hierarchy. Core/periphery differentiation means that societies with different

degrees of population density, polity size and internal hierarchy are

interacting with one another. As soon as we find village dwellers interacting with

nomadic neighbors we have core/periphery differentiation. Core/periphery

hierarchy refers to the nature of the relationship between societies. This kind

of hierarchy exists when some societies are exploiting or dominating other

societies. Examples of intersocietal domination and exploitation would be the

British colonization and deindustrialization of

Distinguishing between

core/periphery differentiation and core/periphery hierarchy allows us to deal

with situations in which larger and more powerful societies are interacting

with smaller ones, but are not exploiting them. It also allows us to examine

cases in which smaller, less dense societies may be exploiting or dominating

larger societies. This latter situation definitely occurred in the long and

consequential interaction between the nomadic horse pastoralists of Central

Asia and the agrarian states and empires of

So the modern world-system is now a global economy with a global political system (the interstate system). It also includes all the cultural aspects and interaction networks of the human population of the Earth. Culturally the modern system is composed of: several civilizational traditions, (e.g. Islam, Christendom, Hinduism, etc.), nationally-defined cultural entities -- nations (and these are composed of class and functional subcultures, e.g. lawyers, technocrats, bureaucrats, etc.), and the cultures of indigenous and minority ethnic groups within states. The modern system is multicultural in the sense that important political and economic interaction networks connect people who have rather different languages, religions and other cultural aspects. Most earlier world-systems have also been multicultural.

Interaction networks are regular and repeated interactions among individuals and groups. Interaction may involve trade, communication, threats, alliances, migration, marriage, gift giving or participation in information networks such as radio, television, telephone conversations, and email. Important interaction networks are those that affect peoples’ everyday lives, their access to food and necessary raw materials, their conceptions of who they are, and their security from or vulnerability to threats and violence. World-systems are fundamentally composed of interaction networks.

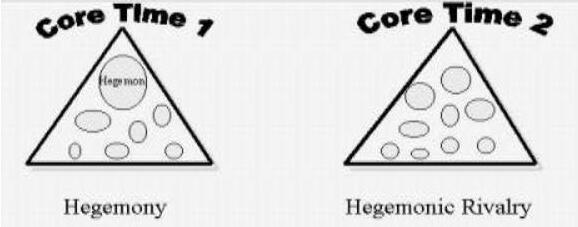

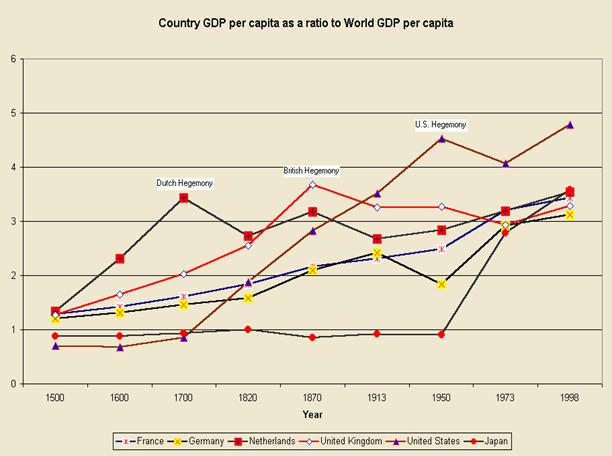

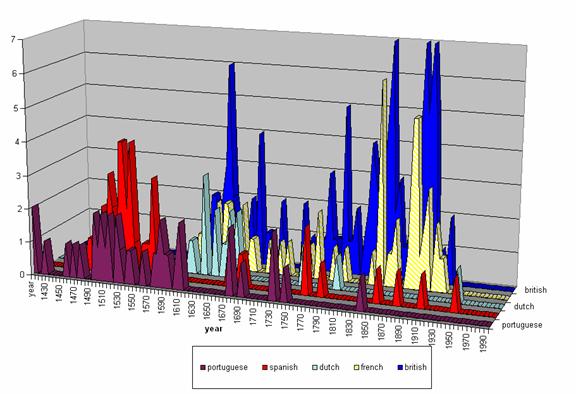

One of the important systemic features of the modern system

is the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers – the so-called “hegemonic

sequence.” A hegemon is a core state that has a significantly greater amount of

economic power than any other state, and that takes on the political role of

system leader. In the seventeenth century the

Figure 2. Hegemony and Hegemonic Rivalry

So the modern world-system is

composed of states that are linked to one another by the world economy and

other interaction networks. Earlier world-systems were also composed of

polities, but the interaction networks that linked these polities were not

intercontinental in scale until the expansion of

SPATIAL BOUNDARIES OF WORLD SYSTEMS

One big difference between the modern world-system and earlier systems is the spatial scale of different types of interaction networks. In the modern global system most of the important interaction networks are themselves global in scale. But in earlier smaller systems there was a significant difference in spatial scale between networks in which food and basic raw materials were exchanged and much larger networks of the exchange of prestige goods or luxuries. Food and basic raw materials we call “bulk goods” because they have a low value per unit of weight. Indeed it is uneconomical to carry food very far under premodern conditions of transportation.

Imagine that the only type of transportation available is people carrying goods on their backs (or heads). This is a situation that actually existed everywhere until the domestication of beasts of burden. Under these conditions a person can carry, say, 30 kilograms of food. Imagine that this carrier is eating the food as s/he goes. So after a few days walking all the food will be consumed. This is the economic limit of food transportation under these conditions of transportation. This does not mean that food will never be transported farther than this distance, but there would have to be an important reason for moving it beyond its economic range.

A prestige good (e.g. a very valuable food such as spices, or jewels or bullion) has a much larger spatial range because a small amount of such a good may be exchanged for a great deal of food. This is why prestige goods networks are normally much larger than bulk goods networks. A network does not usually end as long as there are people with whom one might trade. Indeed most early trade was what is called down-the-line trade in which goods are passed from group to group. For any particular group the effective extent of its of a trade network is that point beyond which nothing that happens will affect the group of origin.

In order to bound interaction

networks we need to pick a place from which to start – a so-called

“place-centric approach.” If we go looking for actual breaks in interaction

networks we will usually not find them, because almost all groups of people

interact with their neighbors. But if we focus upon a single settlement, for

example the precontact indigenous village of Onancock on the Eastern shore of

the Chesapeake Bay (near the boundary between what are now the states of

Virginia and Maryland), we can determine the spatial scale of the interaction

network by finding out how far food moved to and from our focal village. Food

came to Onancock from some maximum distance. A bit beyond that were groups that

were trading food to groups that were directly sending food to Onancock. If we

allow two indirect jumps we are probably far enough from Onancock so that no

matter what happens (e.g. a food shortage or surplus), it would not have

affected the supply of food in Onancock. This outer limit of Onancock’s

indigenous bulk goods network probably included villages at the very southern

and northern ends of the

Onancock’s prestige goods network

was much larger because prestige goods move farther distances. Indeed, copper

that was in use by the indigenous peoples of the

Information, like a prestige good, is light relative to its value. Information may travel far along trade routes and beyond the range of goods. Thus information networks (INs) are usually as large or even larger than Prestige Goods nets (PGNs).

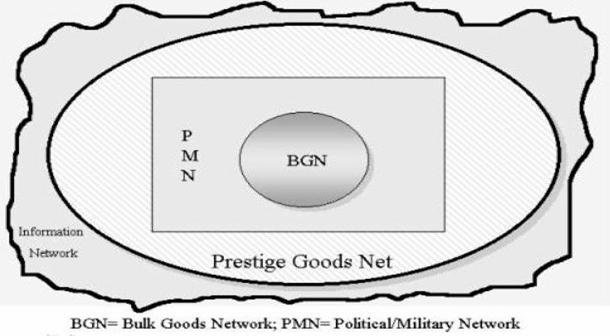

A general picture of the spatial relationships between

different kinds of interaction networks is presented in Figure 3. The actual

spatial scale of important interaction needs to be determined for each

world-system we study, but Figure 4 shows what is generally the case – that

BGNs (bulk goods nets) are smaller than PMNs (political-military nets), and

these are in turn smaller than PGNs (prestige goods nets) and INs (information

nets).

Figure 3. The Spatial Boundaries of World Systems

Defined in the way that we have above, world-systems have grown from small to large over the past twelve millennia as societies and intersocietal systems have gotten larger, more complex and more hierarchical. This spatial growth of systems has involved the expansion of some and the incorporation of some into others. The processes of incorporation have occurred in several ways as systems distant from one another have linked their interaction networks. Because interaction nets are of different sizes, it is the largest ones that come into contact first. Thus information and prestige goods link distant groups long before they participate in the same political-military or bulk goods networks. The processes of expansion and incorporation brought different groups of people together and made the organization of larger and more hierarchical societies possible. It is in this sense that globalization has been going on for thousands of years.

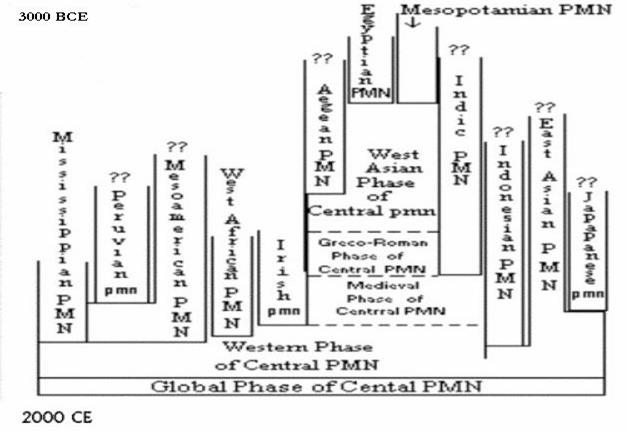

Using the conceptual apparatus for spatially bounding world-systems outlined above we can construct spatio-temporal chronographs for how the interaction networks of the human population changed their spatial scales to eventuate in the single global political economy of today. Figure 4 (see next page) uses PMNs as the unit of analysis to show how a "Central" PMN, composed of the merging of the Mesopotamian and Egyptian PMNs in about 1500 BCE, eventually incorporated all the other PMNs into itself.

WORLD-SYSTEM CYCLES: RISE-AND-FALL AND PULSATIONS

Comparative research reveals that

all world-systems exhibit cyclical processes of change. There are two major

cyclical phenomena: the rise and fall of large polities, and pulsations in the

spatial extent and intensity of trade networks. "Rise and fall"

corresponds to changes in the centralization of political/military power in a

set of polities – an “international” system. It is a question of the relative

size of, and distribution of, power across a set of interacting polities. The

term "cycling" has been used to describe this phenomenon as it

operates among chiefdoms (

Figure 4. Chronograph of PMNs [adapted from Wilkinson (1987)

All world-systems in which there

are hierarchical polities experience a cycle in which relatively larger

polities grow in power and size and then decline. This applies to interchiefdom

systems as well as interstate systems, to systems composed of empires, and to

the modern rise and fall of hegemonic core powers (e.g.

States). Though very egalitarian and small scale systems

such as the sedentary foragers of

All systems, including even very small and egalitarian ones, exhibit cyclical expansions and contractions in the spatial extent and intensity of exchange networks. We call this sequence of trade expansion and contraction pulsation. Different kinds of trade (especially bulk goods trade vs. prestige goods trade) usually have different spatial characteristics. It is also possible that different sorts of trade exhibit different temporal sequences of expansion and contraction. It should be an empirical question in each case as to whether or not changes in the volume of exchange correspond to changes in its spatial extent. In the modern global system large trade networks cannot get spatially larger because they are already global in extent. [1] But they can get denser and more intense relative to smaller networks of exchange. A good part of what has been called globalization is simply the intensification of larger interaction networks relative to the intensity of smaller ones. This kind of integration is often understood to be an upward trend that has attained its greatest peak in recent decades of so-called global capitalism. But research on trade and investment shows that there have been two recent waves of integration, one in the last half of the nineteenth century and the most recent since World War II (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000).

The simplest hypothesis regarding the temporal relationships between rise-and-fall and pulsation is that they occur in tandem. Whether or not this is so, and how it might differ in distinct types of world-systems, is a set of problems that are amenable to empirical research.

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) have contended that the causal processes of rise and fall differ depending on the predominant mode of accumulation. One big difference between the rise and fall of empires and the rise and fall of modern hegemons is in the degree of centralization achieved within the core. Tributary systems alternate back and forth between a structure of multiple and competing core states on the one hand and core-wide (or nearly core-wide) empires on the other. The modern interstate system experiences the rise and fall of hegemons, but these never take over the other core states to form a core-wide empire. This is the case because modern hegemons are pursuing a capitalist, rather than a tributary form of accumulation.

Analogously, rise and fall works

somewhat differently in interchiefdom systems because the institutions that

facilitate the extraction of resources from distant groups are less fully

developed in chiefdom systems. David G. Anderson's (1994) study of the rise and

fall of Mississippian chiefdoms in the Savannah River valley provides an

excellent and comprehensive review of the anthropological and sociological literature

about what

disintegrated back toward a system of smaller and less hierarchical polities.

Chiefs relied more completely on hierarchical kinship relations, control of ritual hierarchies, and control of prestige goods imports than do the rulers of true states. These chiefly techniques of power are all highly dependent on normative integration and ideological consensus. States developed specialized organizations for extracting resources that chiefdoms lacked -- standing armies and bureaucracies. And states and empires in the tributary world-systems were more dependent on the projection of armed force over great distances than modern hegemonic core states have been. The development of commodity production and mechanisms of financial control, as well as further development of bureaucratic techniques of power, have allowed modern hegemons to extract resources from far-away places with much less overhead cost.

The development of techniques of power have made core/periphery relations ever more important for competition among core powers and have altered the way in which the rise-and-fall process works in other respects. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997: Chapter 6) argued that population growth in interaction with the environment, and changes in productive technology and social structure produce social evolution that is marked by cycles and periodic jumps. This is because each world-system oscillates around a central tendency (mean) due both to internal instabilities and environmental fluctuations. Occasionally, on one of the upswings, people solve systemic problems in a new way that allows substantial expansion. We want to explain expansions, evolutionary changes in systemic logic, and collapses. That is the point of comparing world-systems.

The multiscalar regional method of bounding world-systems as nested interaction networks outlined above is complementary with a multiscalar temporal analysis of the kind suggested by Fernand Braudel’s work. Temporal depth, the longue duree, needs to be combined with analyses of short-run and middle-run processes to fully understand social change. The shallow presentism of most social science and contemporary culture needs to be denounced at every opportunity.

A strong case for the very longue duree is made by Jared Diamond’s (1997) study of original zoological and botanical wealth. The geographical distribution of those species that could be easily and profitably domesticated explains a huge portion of the variance regarding which world-systems expanded and incorporated other world-systems thousands of years hence. Diamond also contends that the diffusion of domesticated plant and animal species occurs much more quickly in the latitudinal dimension (East/West) than in the longitudinal dimension (North/South), and so this explains why domesticated species spread so quickly to Europe and East Asia from West Asia, while the spread south into Africa was much slower, and the North/South orientation of the American continents made diffusion much slower than in the Old World Island of Eurasia.

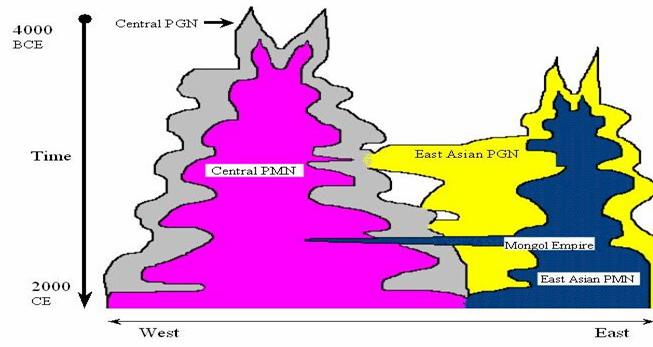

Figure 5 below depicts the coming together of the East Asian and the West Asian/Mediterranean systems. Both the PGNs and the PMNs are shown, as are the pulsations and rise and fall sequences. The PGNs linked intermittently and then joined. The Mongol conquerors linked the PMNs briefly in the thirteenth century, but the Eastern and Western PMNs were not permanently linked until the Europeans and Americans established Asian treaty ports in the nineteenth century.

Figure 5. East/West Pulsations and Merger (next page)

MODES OF ACCUMULATION

In order to comprehend the qualitative changes that have occurred with the processes of social evolution we need to conceptualize different logics of development and the institutional modes by which socially created resources are produced and accumulated. All societies produce and distribute the goods that are necessary for everyday life. But the institutional means by which human labor is mobilized are very different in different kinds of societies. Small and egalitarian societies rely primarily on normative regulation organized as commonly shared understandings about the obligations that members of families have toward one another. When a hunter returns with his game there are definite rules and understandings about who should receive shares and how much. All hunters in foraging societies want to be thought of as generous, but they must also take care of some people (those for whom they are the most responsible) before they can give to others.

The normative order defines the roles and the obligations, and the norms and values are affirmed or modified by the continual symbolic and non-symbolic action of the people. This socially constructed consciousness is mainly about kinship, but it is also about the nature of the universe of which the human group is understood as a part. This kind of social economy is called a kin-based mode of production and accumulation. People work because they need food and they have obligations to provide food for others. Accumulation mainly involves the preservation and storage of food supplies for the season in which food will become scarce. Status is based on the reputation that one has as a good hunter, a good gatherer, a good family member, or a talented speaker. Group decisions are made by consensus, which means that the people keep talking until they have come to an understanding of what to do. The leaders have authority that is mainly based on their ability to convince others that they are right. These features are common (but not universal) among societies and world-systems in which the kin-based modes of accumulation are the main logic of development.

As societies become larger and more

hierarchical, kinship itself becomes hierarchically defined. Clans and lineages

become ranked so that members of some families are defined as senior or

superior to members of other families. Classical cases of ranked societies were

those of the

The tributary modes of accumulation emerged when institutional coercion became a central form of regulation for inducing people to work and for the accumulation of social resources. Hierarchical kinship functions in this way when commoners must provide labor or products to chiefs in exchange for access to resources that chiefs control by means of both normative and coercive power.

Normative power does not work well by itself as a basis for the appropriation of labor or goods by one group from another. Those who are exploited have a great motive to redefine the situation. The nobles may have elaborated a vision of the universe in which they were understood to control natural forces or to mediate interactions with the deities and so commoners were supposed to be obligated to support these sacred duties by turning over their produce to the nobles or contributing labor to sacred projects. But the commoners will have an incentive to disbelieve unless they have only worse alternatives. Thus the institutions of coercive power are invented to sustain the extraction of surplus labor and goods from direct producers. The hierarchical religions and kinship systems of complex chiefdoms became supplemented in early states by specialized organizations of regional control -- groups of armed men under the command of the king and bureaucratic systems of taxation and tribute backed up by the law and by institutionalized force. The tributary modes of accumulation develop techniques of power that allowed resources to be extracted over great distances and from large populations. These are the institutional bases of the states and the empires.

The third mode of accumulation is based on markets. Markets can be defined as any situation in which goods are bought and sold, but we will use the term to denote what are called price-setting markets in which the competitive trading by large numbers of buyers and sellers is an important determinant of the price. This is a situation in which supply and demand operate on the price because buyers and sellers are bidding against one another. In practice there are very few instances in history or in modern reality of purely price-setting markets, because political and normative considerations quite often influence prices. But the price mechanism and resulting market pressures have become more important. These institutions were completely absent before the invention of commodities and money.

A commodity is a good that is produced for sale in a price-setting market in order to make a profit. A pencil is an example of a modern commodity. It is a fairly standardized product in which the conditions of production, the cost of raw materials, labor, energy and pencil-making machines are important forces acting upon the price of the pencil. Pencils are also produced for a rather competitive market, and so the socially necessary costs given the current level of technology, plus a certain amount of profit, adds up to the cost.

The idea of the commodity is an important element of the definition of the capitalist mode of accumulation. Capitalism is the concentrated accumulation of profits by the owners of major means of the production of commodities in a context in which labor and the other main elements of production are commodified. Commodification means that things are treated as if they are commodities, even though they may have characteristics that make this somewhat difficult. So land can be commodified – treated as if it is a commodity – even though it is a limited good that has not originally been produced for profitable sale. There is only so much land on earth. We can divide it up into sections with straight boundaries and price it based on supply and demand. But it will never be a perfect commodity. This is also the case with human labor time.

The commodification of land is an historical process that began when “real property” was first legally defined and sold. The conceptualization of places as abstract, measurable, substitutable and salable space is an institutional redefinition that took thousands of years to develop and to spread to all regions of the Earth.

The capitalist modes of production also required the redefinition of wealth as money. The first storable and tradable valuables were probably prestige goods. These were used by local elites in trade with adjacent peoples, and eventually as symbols of superior status. Trade among simple societies is primarily organized as gift giving among elites in which allegiances are created and sustained. Originally prestige goods were used only in specific circumstances by certain elites. This “proto-money” was eventually redefined and institutionalized as the so-called “universal equivalent” that serves as a general measure of value for all sorts of goods and that can be used by almost anyone to buy almost anything. The institution of money has a long and complicated history, but suffice it to say here that it has been a prerequisite for the emergence of price-setting markets and capitalism as increasingly important forms of social regulation. Once markets and capital become the predominant form of accumulation we can speak of capitalist systems.

Patterns and Causes of

Social Evolution

It is important to understand the similarities, but also the important differences between biological and social evolution. These are discussed in Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2005: Chapter 1). This section describes a general causal model that explains the emergence of larger hierarchies and the development of productive technologies. It also points to a pattern that is noticeable only when we study world-systems rather than individual societies. The pattern is called semiperipheral development. This means that those innovations that transform the logic of development and allow world-systems to get larger and more hierarchical come mainly from semiperipheral societies. Some semiperipheral societies are unusually fertile locations for the invention and implementation of new institutional structures. And semiperipheral societies are not constrained to the same degree as older core societies from having invested huge resources in doing things in the old way. So they are freer to implement new institutions.

There are several different important kinds of semiperipheries, and these not only transform systems but they also often take over and become new core societies. We have already mentioned semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms. The societies that conquered and unified a number of smaller chiefdoms into larger paramount chiefdoms were usually from semiperipheral locations. Peripheral peoples did not usually have the institutional and material resources that would allow them to make important inventions and to implement these or to take over older core regions. It was in the semiperiphery that core and peripheral social characteristics could be recombined in new ways. Sometimes this meant that new techniques of power or political legitimacy were invented and implemented in semiperipheral societies.

Much better known than semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms is the phenomenon of semiperipheral marcher states. The largest empires have been assembled by conquerors who come from semiperipheral societies. The following semiperipheral marchers are well known: the Achaemenid Persians, the Macedonians led by Alexander The Great, the Romans, the Ottomans, the Manchus and the Aztecs.

But some semiperipheries transform

institutions, but do not take over. The semiperipheral capitalist city-states

operated on the edges of the tributary empires where they bought and sold goods

in widely separate locations, encouraging people to produce a surplus for

trade. The Phoenician cities (e.g.

In the modern world-system we have

already mentioned the process of the rise and fall of hegemonic core states.

All of the cases we mentioned – the Dutch, the British and the

The idea of semiperipheral development does not claim that all semiperipheral societies perform transformational roles, nor does it contend that every important innovation came from the semiperiphery. The point is rather that semiperipheries have been unusually prolific sites for the invention of those institutions that have expanded and transformed many small systems into the particular kind of global system that we have today. This observation would not be possible without the conceptual apparatus of the comparative world-systems perspective.

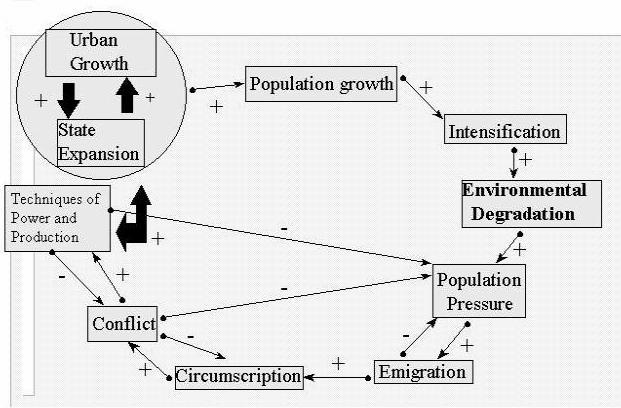

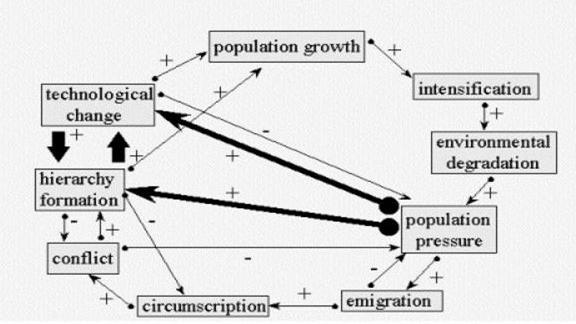

But what have been the proximate causes that led semiperipheral societies to invent new institutional solutions to problems? Some of the problems that needed to be solved were new unintended consequences of earlier inventions, but others were very old problems that kept emerging again and again as systems expanded – e.g. population pressure and ecological degradation. It is these basic problems that make it possible for us to specify a single underlying causal model of world-systems evolution. Figure 6 shows what is called the “iteration model” that links demographic, ecological and interactional processes with the emergence of new production technologies, bigger polities and greater degrees of hierarchy. In this model, arrows indicate effects, and signs indicate directions of effects.

Figure 6. Basic Iteration Model of World-System Evolution

This is called an iteration model because it has an important positive feedback mechanism in which the original causes are themselves consequences of the things that they cause. Thus the process goes around and around, which is what has caused the world-systems to expand to the global level. Starting at the top we see population growth. The idea here is that all human societies contain a biological impetus to grow that is based on sexuality. This impetus is both controlled and encouraged by social institutions. Some societies try to regulate population growth by means of e.g. infanticide, abortion and taboos on sexual relations during nursing. These institutional means of regulation are costly, and when greater amounts of food are available these types of regulation tend to be eased. Other kinds of societies encourage population growth by means of channeling sexual energy toward reproduction, pro-natalist ideologies and support for large families. All societies experience periodic “baby booms” when social circumstances are somewhat more propitious for reproduction, and thus, over the long run, the population tends to grow despite institutional mechanisms that try to control it.

Intensification is caused by population growth. This means that when the number of mouths to feed increases greater efforts are needed to produce food and other necessities of life and so people exploit the resources they have been exploiting more intensively. This usually leads, in turn, to ecological degradation because all human production processes use up the natural environment. More production leads to greater environmental degradation. This occurs because more resources are extracted, and because of the polluting consequences of production and consumption activities. Nomadic hunter-gatherers depleted the herds of big game and Polynesian horticulturalists deforested many a Pacific island. Environmental degradation is not a new phenomenon. Only its global scale is new.

As Jared Diamond (1998) points out

all continents around the world did not start with the same animal and plant

resources. In West Asia both plants (barley and wheat) and animals (sheep,

goats, cows, and oxen) were more easily domesticated than the plants and

animals of Africa and the

The consequences of the above processes are that the

economics of production change for the worse. According to Joseph Tainter

(1988), after a certain point increased investment in complexity does not

result in proportionate increasing returns. This occurs in the areas of

agricultural production, information processing and communication, including

education and maintenance of information channels. Sociopolitical control and

specialization, such as military and the police, also develop diminishing

returns. Tainter points out that marginal returns can occur in at least four

instances: benefits constant, costs rising; benefits rising, costs rising

faster; benefits falling, costs constant; benefits falling, costs rising.

When herds are depleted the hunters must go farther to find game. The combined sequence from population growth to intensification to environmental degradation leads to population pressure, the negative economic effects on production activities. The growing effort needed to produce enough food is a big incentive for people to migrate. And so humans populated the whole Earth. If the herds in this valley are depleted we may be able to find a new place where they are more abundant.

Migration eventually leads to circumscription. Circumscription is the condition that no new desirable locations are available for emigration. This can be because all the herds in all the adjacent valleys are depleted, or because all the alternative locations are deserts or high mountains, or because all adjacent desirable locations are already occupied by people who will effectively resist immigration.

The condition of social circumscription in which adjacent locations are already occupied is, under conditions of population pressure, likely to lead to a rise in the level of intergroup and intragroup conflict. This is because more people are competing for fewer resources. Warfare and other kinds of conflict are more prevalent under such conditions. All systems experience some warfare, but warfare becomes a focus of social endeavor that often has a life of its own. Boys are trained to be warriors and societies make decisions based on the presumption that they will be attacked or will be attacking other groups. Even in situations of seemingly endemic warfare the amount of conflict varies cyclically. Figure 7 shows an arrow with a negative sign going from conflict back to population pressure. This is because high levels of conflict reduce the size of the population as warriors are killed off and non-combatants die because their food supplies have been destroyed. Some systems get stuck in a vicious cycle of population pressure and warfare.

But situations such as this are also propitious for the emergence of new institutional structures. It is in these situations that semiperipheral development is likely to occur. People get tired of endemic conflict. One solution is the emergence of a new hierarchy or a larger polity that can regulate access to resources in a way that generates less conflict. The emergence of a new larger polity usually occurs as a result of successful conquest of a number of smaller polities by a semiperipheral marcher. The larger polity creates peace by means of an organized force that is greater than any force likely to be brought against it. The new polity reconstructs the institutions of control over territory and resources, often concentrating control and wealth for a new elite. And larger and more hierarchical polities often invest in new technologies of production that change the way in which resources are utilized. They produce more food and other necessaries by using new technologies or by intensifying the use of old technologies. New technologies can expand the number of people that can be supported in the territory. This makes population growth more likely, and so the iteration model is primed to go around again.

The iteration model has kept expanding the size of world-systems and developing new technologies and forms of regulation but, at least so far, it has not permanently solved the original problems of ecological degradation and population pressure. What has happened is the emergence of institutions such as states and markets that articulate changes in the economics of production more directly with changes in political organization and technology. This allows the institutional structures to readjust without having to go through short cycles at the messy bottom end of the model.

Figure 7. Temporary Institutional Shortcuts in the Iteration Model

Another way to say this is that political and market institutions allow for some adjustments to occur without greatly increasing the level of systemic conflict. This said, the level of conflict has remained quite high, because the rate of expansion and technological change has increased. Even though institutional mechanisms of articulation have emerged, these have not permanently lowered the amount of systemic conflict because the rates of change in the other variables have increased.

It is also difficult to understand why and where innovative

social change emerges without a conceptualization of the world-system as a

whole. New organizational forms that transform institutions and that lead to

upward mobility most often emerge from societies in semiperipheral

locations. Thus all the countries that

became hegemonic core states in the modern system had formerly been

semiperipheral (the Dutch, the British, and the

This approach requires that we think structurally. We must be able to abstract from the particularities of the game of musical chairs that constitutes uneven development in the system to see the structural continuities. The core/periphery hierarchy remains, though some countries have moved up or down. The interstate system remains, though the internationalization of capital has further constrained the abilities of states to structure national economies. States have always been subjected to larger geopolitical and economic forces in the world-system, and as is still the case, some have been more successful at exploiting opportunities and protecting themselves from liabilities than others.

In this perspective many of the phenomena that have been called “globalization” correspond to recently expanded international trade, financial flows and foreign investment by transnational corporations and banks. Much of the globalization discourse assumes that until recently there were separate national societies and economies, and that these have now been superseded by an expansion of international integration driven by information and transportation technologies. Rather than a wholly unique and new phenomenon, globalization is primarily international economic integration, and as such it is a feature of the world-system that has been oscillating as well as increasing for centuries. Recent research comparing the 19th and 20th centuries has shown that trade globalization is both a cycle and a trend.

The Great Chartered Companies of the seventeenth century were already playing an important role in shaping the development of world regions. Certainly the transnational corporations of the present are much more important players, but the point is that “foreign investment’ is not an institution that only became important since 1970 (nor since World War II). Giovanni Arrighi (1994) has shown that finance capital has been a central component of the commanding heights of the world-system since the fourteenth century. The current floods and ebbs of world money are typical of the late phase of very long “systemic cycles of accumulation.”

Most world-systems scholars contend that leaving out the core/periphery dimension or treating the periphery as inert are grave mistakes, not only for reasons of completeness, but also because the ability of core capitalists and their states to exploit peripheral resources and labor has been a major factor in deciding the winners of the competition among core contenders. And the resistance to exploitation and domination mounted by peripheral peoples has played a powerful role in shaping the historical development of world orders. Thus world history cannot be properly understood without attention to the core/periphery hierarchy.

Phillip McMichael (2000) has

studied the “globalization project” – the abandoning of Keynesian models of

national development and a new (or renewed) emphasis on deregulation and

opening national commodity and financial markets to foreign trade and

investment. This approach focuses on the

political and ideological aspects of the recent wave of international

integration. The term many prefer for this turn in global discourse is

“neo-liberalism” but it has also been called “Reaganism/Thatcherism” and the

“Washington Consensus.” The worldwide decline of the political left predated

the revolutions of 1989 and the demise of the

This is the part of the theory of a global stage of

capitalism that must be taken most seriously, though it can certainly be

overdone. The world-system has now

reached a point at which both the old interstate system based on separate

national capitalist classes, and new institutions representing the global

interests of capital exist, and are powerful simultaneously. In this light each country can be seen to

have an important ruling class fraction that is allied with the transnational

capitalist class. The big question is whether or not this new level of

transnational integration will be strong enough to prevent competition among

states for world hegemony from turning into warfare, as it has always done in the

past, during a period in which a hegemon (now the

The insight that capitalist globalization has occurred in waves, and that these waves of integration are followed by periods of globalization backlash has important implications for the future. Capitalist globalization increased both intranational and international inequalities in the nineteenth century and it has done the same thing in the late twentieth century (O’Rourke and Williamson 2000). Those countries and groups that are left out of the “beautiful époque” either mobilize to challenge the hegemony of the powerful or they retreat into self-reliance, or both.

Globalization protests emerged in

the non-core with the anti-IMF riots of the 1980s. The several transnational social

movements that participated in the 1999 protest in

There is an apparent tension between those who advocate deglobalization and delinking from the global capitalist economy and the building of stronger, more cooperative and self-reliant social relations in the periphery and semiperiphery, on the one hand, and those who seek to mobilize support for new, or reformed institutions of democratic global governance. Self-reliance by itself, though an understandable reaction to exploitation, is not likely to solve the problems of humanity in the long run. The great challenge of the twenty-first century will be the building of a democratic and collectively rational global commonwealth. World-systems theory can be an important contributor to this effort.

REFERENCES

Amin, Samir.1997.Capitalism

in the Age of Globalization.

Arrighi, Giovanni.1994. The

Long Twentieth Century.

Bairoch, Paul.

the Present.

Barfield, Thomas J. 1989. The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 1998. Global Formation.

Littlefield

Chase-Dunn, C and Thomas D. Hall. 1997. Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems

Chase-Dunn, C and Kelly M. Mann. 1998. The Wintu and Their Neighbors: A Very Small

World-System in Northern California

Chase-Dunn, C., Susan Manning and Thomas D. Hall. 2000. “Rise and Fall: East-West

Synchrony

and Indic Exceptionalism Reexamined,” Social

Science History

24,4:727-754.

Chase-Dunn,

C. Daniel Pasciuti and Alexis Alvarez.

2005. “The Ancient Mesopotamian

and Egyptian

World-Systems” forthcoming in Barry Gills and William R.

Thompson (eds.) The

Evolution of Macrohistorical Systems.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Alice Willard. 1993. "Systems of cities and world-systems:

settlement size hierarchies and cycles of

political centralization, 2000 BC-

1988AD." Paper presented at the International Studies

Association meeting,

March 24-27,

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Bruce Lerro. 2005. Social Change: World Historical

Social Transformations.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 2004. “Modeling dynamic nested networks in

pre-Columbian

Macrosystems as Dynamic Networks,” Santa Fe Institute, April 29-30.

Diamond, Jared. 1997. Guns,

Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies.

Hall, Thomas D. 2000. A

World-Systems Reader: new perspectives on gender, urbanism,

cultures, indigenous peoples, and ecology.

Kirch, Patrick V. 1984. The

Evolution of Polynesian Chiefdoms.

University Press.

_____. 1991.

"Chiefship and Competitive Involution: the

Timothy Earle.

Mann, Michael. 1986. The

Sources of Social Power: A History of Power from the

Beginning to A.D. 1760.

Development of Long-Distance Trade in Early Near Eastern Societies," Pp. 25-

35 in M. Rowlands et al Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World.

Modelski,

George and William R. Thompson. 1995. Leading Sectors and World Powers:

The Coevolution of Global Politics and

Economics.

of

Modelski,

George. 2003. World Cities, -3000 to 2000.

O’Rourke, Kevin H. and Jeffrey G. Williamson. 2000. Globalization and History.

Pasciuti, Daniel 2003. “A

Measurement Error Model for Estimating the Populations of

Cities,” https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/estcit/modpop/modcitpop.htm

Shannon, Thomas R. 1996. An

Introduction to the World-Systems Perspective.

CO: Westview

Taagepera, Rein. 1978a. "Size and Duration of Empires:

Systematics of Size" Social

Science

Research 7:108-27.

______ 1978b. "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 3000 to 600

B.C." Social Science Research 7:180-96.

______1979 "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600

A.D." Social Science History 3:115-38.

_______1997 “Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for

Tainter,

Joseph A. 1988. The

Collapse of Complex Societies.

University Press.

Teggart, Frederick J. 1939.

Events

Thompson, William R. 1995. "Comparing World Systems: Systemic Leadership

Succession and the Peloponnesian War

Case." Pp. 271-286 in The Historical

Evolution of the International Political Economy, Volume 1, edited by

Christopher Chase-Dunn.

Turchin, Peter. 2003. Historical

Dynamics.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2000. The Essential Wallerstein.

Wilkinson, David. 1987. "Central Civilization." Comparative Civilizations Review 17:31-

59.

______ 1992. "Cities, Civilizations and Oikumenes:I." Comparative Civilizations Review

27:51-87.

_______ 1993. “Cities, Civilizations and Oikumenes:II” Comparative Civilizations

Review 28.

Wright, Henry

T. 1986.

"The Evolution of Civilization." Pp. 323-365 in American

Archaeology, Past and Future: A Celebration of the Society for American

Archaeology, 1935-1985, edited by David J. Meltzer. Washington, D. C.:

Smithsonian Institutional Press.

EndNOTES

1. If we manage to get through several sticky wickets looming in the 21st

century the human system will probably expand into the solar system, and so

“globalization” will continue to be spatially expansive.

Chapter 14: The Modern World-System

From C. Chase-Dunn and B. Lerro, Social Change (forthcoming)

Three

chapters that tell the story of the modern system chronologically since the

fifteenth century will follow. But the unfolding story obscures certain general

patterns that can only be see by looking at the whole system over the entire

period of time since the 15th century. These patterns are the

subject of this chapter. The modern system shares many similarities with

earlier regional world-systems, but it is also qualitatively different from

them in some important ways. Obviously it is larger, becoming global

(Earth-wide) with the incorporation of all the remaining separate redoubts

during the nineteenth century. The key defining feature of the modern world-system

is capitalism. We have already seen the long emergence of those institutions

that are crucial for capitalism (private property, commodity production, money,

contract law, price-setting markets, commodified labor) over the previous

millennia in Afroeurasia. But it was in

Capitalism has many definitions and its fundamental

nature is still a matter of lively debate.[i]

We agree with those who define capitalism as an economic process of the

accumulation of profits that interacts fundamentally with a geopolitical

process of state-building, competition among states and increasingly

large-scale political regulation involving institutions of coercion and

governance. Capitalism is not solely an economic logic.

Some theorists contend that

state power and “violence-producing enterprises” were only involved in setting

up the basic underlying political conditions for capitalism during an age of

“primitive accumulation” and once these institutions were in place capitalism

began to operate as a purely economic logic of production, distribution and

profit-making – so-called “expanded reproduction.” [ii]

The world-systems perspective allows us to see that both economic and political

institutions continue to evolve, and the central logic of capitalism is

embedded in the dialectical dance of their co-evolution and expansion.

From a world-systems perspective the political body of

capitalism is the interstate system rather than the single state. Single states

all exist within a larger structure and set of processes that heavily influence

the possibilities for social change. And the interstate system interacts with a

core/periphery hierarchy in which powerful and more developed states and

regions exploit and dominate less powerful and less developed regions.

States are just organizations that claim to exercise a

monopoly of legitimate violence within a particular territory. They are not

whole systems and they never have been. Much of contemporary social science

treats national societies as if they are on the moon, with completely

self-contained (endogenous) patterns of social change. That is even more a

mistake for the modern world-system than it was for the more distant past.

Capitalism and capitalist states existed in earlier

world-systems, but capitalism was only a sideshow within the commercializing

tributary empires, while real capitalist states were confined to the

semiperiphery. Capitalism became predominant in the modern system by becoming

potent in the core. In the modern system the most successful states became

those in which state power was used at the behest of groups who were engaged in

commodity production, trade and financial services. State powers to tax and

collect tributes did not disappear, but these became less important than, and

largely subordinate to, more commercial forms of accumulation.

The very logic of capitalism produces economic, social and political crises in which elites jockey for position and less-favored groups try to protect themselves and/or to fundamentally change the system. Capitalism does not abolish imperialism but rather it produces new kinds of imperialism. Neither does it abolish warfare. It is not a pacific (warless) mode of accumulation as some have claimed (e.g. Schumpeter 1951). Rather the instruments of violence and the dynamics of interstate competition by means of warfare have been increasingly turned to serve the purposes of profitable commodity production and financial manipulations rather than the extraction of tribute. The growing “efficiency” of military technology produced in the capitalist world-system has made warfare much more destructive.

The

core/periphery dimension is not abolished. On the contrary, the institutional

mechanisms by which some societies can exploit and dominate others become more

powerful and efficient and are increasingly justified by ideologies of

civilization, development, foreign investment and foreign aid. “Backwardness”

is reproduced and the world-system becomes even more divided between the

included and the excluded than were earlier systems. The growing inequalities

within and between national societies are justified by ideologies of

productivity and efficiency, with underlying implications that some people are

simply more fit for modernity than others. Nationalism, racism and gender

hierarchies are both challenged and reproduced in a context in which the real

material inequalities amongst the peoples of the world are increasing. This

occurs within a context in which the values of human rights and equality have

become more and more institutionalized, and so huge movements of protest and

struggles over ideas and power occur. All this is characteristic, not only of

the most recent period of globalization and globalization backlash, but of the

whole history of the expansion of modern capitalism.

The

similarities with earlier systems are important. There is a political-military

system of allying and competing polities, now taking the form of the modern

international system (studied mainly by political scientists who focus on

international relations.) There are still different kinds of interaction

networks with different spatial scales, though in the modern system many of the

formerly smaller networks have caught up with the spatial size of the largest

networks. Much of the bulk goods network is now global. One of the unusual

features of the modern system in comparative perspective is that the

differences in spatial scale among different kinds of networks has been greatly

reduced, which makes its far easier for people to comprehend the complex

networks in which they are involved.

The

phenomenon of rise and fall remains an important pattern, albeit with some

significant differences. As with earlier state-based systems, there is a

structurally important interaction between core regions and less powerful

peripheral regions. There remains an important component of multiculturalism in

the system as a whole, a feature that is typical of most world-systems.

Semiperipheral development continues. As discussed in Chapter 13, the rise of

But

the nature of the mode of accumulation is quite different and there are related

other differences that are connected with the emergent predominance of

capitalism. Both the pattern of rise and

fall and the nature of core/periphery relations are significantly different.

Since accumulation is predominantly capitalist and the most powerful core

states are also the most important centers of capitalist accumulation, they do

not use their military power to conquer other core states in order to extract

revenues from them. In world-systems in which the tributary mode of

accumulation is predominant, semiperipheral marcher states conquer adjacent

core states in order to extract resources and erect “universal” empires.

Similar versions of this strategy have been attempted in the modern system

(e.g. the Hapburgs in the 16th century, Napoleon at the end of 18th

century,

Another

sense in which capitalism may be thought of as progressive is its effects on

technological change. Technological change has been a crucial aspect of human

social evolution since the emergence of speech. The rate of innovation and

implementation increased slowly as societies became more complex, but

capitalism shoves the rate of technological change toward the sky. This is

because economic rewards are more directly linked to technological innovation

and improvements in production processes. There are, to be sure, countervailing

forces within real capitalism, as when large companies sit on new technologies

that would threaten their existing profitable operations. But because permanent

world-wide monopolies do not exist (in the absence of a world state), the

efforts of the powerful to protect their profits have repeatedly come under

attack by a dynamic market system and competition among states. The

institutionalization of scientific research and development has also added

another strong element to the development and implementation of new

technologies, so that in the most developed countries rapid technological

change and accompanying social changes have become acceptable to people despite

their disruptive aspects. This is a major way in which the modern world-system

differs from earlier systems. Social change of all kinds has speeded up.

Another

major difference between the modern system and earlier state-based systems is

in the way in which the cycle of rise and fall occurs. The hegemonic sequence

(the rise and fall of hegemonic core states) is the modern version of the

ancient oscillation between more and less centralized interstate systems. As we

have seen, all hierarchical systems experience a cycle of rise and fall, from

“cycling” in interchiefdom systems to the rise and fall of empires, to the

modern sequence of hegemonic rise and fall. [iii]

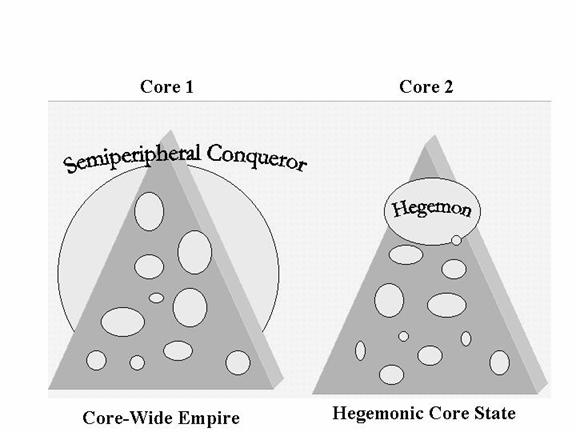

In tributary world-systems this oscillation typically takes the form of

semiperipheral marcher states conquering older core states to form a core-wide

empire.[iv]

(see Figure 1). Figure 1 contrasts the structure of a core-wide empire with

that of a more multicentric system in which one state is the hegemon.

Figure 1: Core-Wide Empire vs. Hegemonic

One

important consequence of the coming to predominance of capitalist accumulation

has been the conversion of the rise and fall process from semiperipheral

marcher conquest to the rise and fall of capitalist hegemons that do not take

over other core states. The hegemons rise to economic and political/military

preeminence from the semiperiphery, but they do not construct a core-wide world

state by means of conquest. Rather, the core of the modern system oscillates

between unipolar hegemony and even more multicentric hegemonic rivalry.

Capitalist

accumulation usually favors a multicentric interstate system because this

provides greater opportunities for the maneuverability of capital than would

exist in a world state. Big capitals can play states off against one another

and can escape movements that try to regulate investment or redistribute

profits by abandoning the states in which such movements attain political

power.

Another

difference produced by the rise of capitalism is the way in which imperialism

is organized in a capitalist world-system. The predominant form of modern

imperialism has taken the form of what has been called “colonial empires.”

Rather than conquering ones immediate neighbors to make an empire, the most

successful form of core/periphery exploitation in the modern system has

involved European core states establishing political and economic controls over

distant colonies in the

There

is another important difference between the modern core/periphery hierarchy and

the earlier Afroeurasian system in the

nature of core/periphery relations. The ability to extract resources from

peripheral areas has long been an important component of successful

accumulation in state-based world-systems and this is also true for the modern

world-system. But there is an

interesting and important difference -- the reversal of the location of

relative intrasocietal inequalities. In state-based world-systems core

societies had relatively greater internal inequalities than did peripheral

societies. Typical core states were urbanized and class-stratified while

peripheral societies were nomadic pastoralists or horticulturalists or

less-densely concentrated peoples living in smaller towns or villages. These

kinds of peripheral groups usually had less internal inequality than did the

core states with which they were interacting.

In

the modern world-system this situation has reversed. Core societies typically

have less (relative) internal inequality than do peripheral societies. The

kinds of jobs that are concentrated in the core, and the eventual development

of welfare states in the core, have expanded the size of the middle classes

within core societies to produce a more-or-less diamond-shaped distribution of

income that bulges in the middle. Typical peripheral societies, on the other

hand, have a more pyramid-shaped income distribution in which there is a small

rich elite, a rather small middle class, and a very large mass of very poor

people.[vi]

This

reversal in the location of relative internal inequality between cores and

peripheries was mainly a consequence of the development and concentration of

complex economies needing skilled labor in the core and the politics of

democracy and the welfare state that have accompanied capitalist

industrialization.

These

processes have occurred in tandem with, and dependent upon, the development of

peripheral capitalism, colonialism, and neo-colonialism in the periphery, which

have produced the greater relative inequalities within peripheral societies.

Core capitalism is dependent upon peripheral capitalism in part because

exploitation of the periphery provides some of the resources that core capital

sometimes uses to pay higher incomes to core workers. Furthermore, the reproduction of an

underdeveloped periphery legitimates the national capital/labor alliances that

have provided a relative harmony of class relations in the core and undercut

radical challenges to capitalist power (Chase-Dunn 1998:Chap. 11). We do not

claim that all core workers compose a

"labor aristocracy" in the modern world-system. Obviously

groups within the core working class compete against each other and some are

downsized and streamlined, etc. in the competition of core capitalists with one

another. But the overall effect of core/periphery relations has been to

undercut challenges to capitalism within core states by paying off some core

workers and groups and convincing others that they should support and identify

with the “winners.”

In

premodern systems core/periphery relations were also important for sustaining

the social order of the core (e.g., the bread and circuses of

Another

important difference is that the Central System before 1800 contained three

non-adjacent core regions(Europe/West Asia; South Asia; and East Asia), each

with its "own" core/periphery hierarchy, whereas the rise of the

European core produced a global system with a single integrated set of core

states and a global core/periphery hierarchy. This brought about the complete

unification of the formerly somewhat separate regional world histories into a

single global history.

Political

ecologists have argued that capitalism is fundamentally different from earlier

modes of accumulation with respect to its relationship to the natural

environment (O’Conner 1989, Foster 2000). There is little doubt that the

expansion and deepening of the modern system global capitalism has had much

larger effects on the biogeosphere than any earlier system. There are many more

people using hugely increased amounts of energy and raw materials, and the

global nature of the human system has global impacts on the environment.

Smaller systems were able to migrate when they depleted local supplies or polluted

local natural resources and this relationship with the environment has been a

driving force of human social change since the Paleolithic. But is all this due

only to capitalism’s greater size and intensity, or is there also something

else which encourages capitalists to “externalize” the natural costs of

production and distribution and produces a destructive “metabolic rift” between

capitalism and nature (Foster 2000)?

Capitalism,

in addition to being about market exchange and commodification, is also

fundamentally about a certain kind of property – private property in the major

means of production. Within modern capitalism there has been an oscillating

debate about the virtues of public and private property, with the shift since

the 1980s toward the desirability of “privatization” being only the most recent

round of a struggle that has gone on since the enclosures of the commons in

The

ongoing debate about the idea of the “commons” –collective property-- is

germane to understanding the relationship between capitalism and nature. The

powerful claims about the commons being a “tragedy” because no one cares enough

to take care of and invest in public property carries a powerful baggage that

supports the notion that private ownership is superior. Private owners are

supposed to have an interest in the future value of the property, and so they

will keep it up, and possibly invest in it. But whether or not this is better

than a more public or communal form of ownership depends entirely on how these more

collective forms of property are themselves organized.

Capitalism

seems to contain a powerful incentive to externalize the natural costs of

production and other economic activities, and individual capitalists are loathe

to pay for the actual environmental costs of their activities as long as their

competitors are getting a free ride. This is a political issue in which core

countries in the modern capitalist system have been far more successful at

building institutions for protecting the national environment than non-core

countries. And, indeed, there is convincing evidence that core countries export

pollution and environmental degradation to the non-core (Jorgenson 2004).

Certainly

modern capitalism has been more destructive of the natural environment than any

earlier system. But it is important to know whether or not this is completely

due to its effects on technology and the rapidity of economic growth, or

whether or not there is an additional element that is connected to the specific

institutions and contradictions of capitalism. Technological development,

demographic expansion and economic growth cause problems for the environment.

But are there better alternatives? And is capitalism more destructive of the

environment than earlier modes of accumulation net of its demographic and

technological effects?

Undoubtedly

the human species can and must do better at inventing institutions that protect

the geobiosphere. Regarding earlier modes of accumulation, certainly some

cultures did better than others at protecting the environment. The institutions

of law, the state and property evolved, in part, as a response to environmental

degradation (recall our “iteration model” in Chapter 2). It is not obvious that

contemporary capitalist institutions are worse than earlier ones in this

regard. The main problem is that the scale and scope of environmental

degradation has increased so greatly that very powerful institutions and social

movements will be required to bring about a sustainable human civilization. Capitalism

may not be capable of doing this, and so those theoretical perspectives that

point to the need for a major overhaul may be closer to the point than those

that contend that capitalism itself can be reformed to become sustainable.

The Schema of

Constants, Cycles, Trends and Cyclical Trends

Most

histories of the modern world tell a story, and we shall do the same in the

following chapters. But here we will begin with a model, as if the modern

world-system were a great machine or a superorganism. The systemic analogy will

be stressed at this point so that we can see whether, and in what ways, the

basic system has changed in the chapters that follow. One way to help us think

about the modern world-system as a whole is to describe its structures and

processes in terms of patterns that are more or less constant, those that are

cyclical, and those that are upward (or downward) trends. And some important

characteristics of the whole system, like globalization, are both cycles and

trends. This means that there are waves of globalization in the sense of larger

and more intense interactions, and that these waves also go up over time – an