Globalization

in Nubia

during the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period

(2000- 1500 B.C.)

Walter de Winter

University of Leiden

The research to the economic function of the

Ancient Egyptian “Second Cataract” Forts, now in present day northern Sudan,

focuses on pottery studies and study to the sealing system that was used during

the Late Middle Kingdom. The abundance of the sealings due to mass production

in contrast with the Early Middle Kingdom points to a globalization leap in

interconnectivity. The system monitored the increased flow of goods, and

reflected a certain administrative control, and the use of economic institutes

like treasuries, granaries, magazines, provisions, “Upper Fort”, Seal of the

Governor, and Seal of Sesostris, with officials attached to that.The adoption

of this sealing system by the Kerma culture during the Second Intermediate

Period suggests trade contacts with Egypt and concurring social changes.

New research could point out that the

adoption of the sealing system could have been not after the Middle Kingdom,

but even during this period due to a chronological shift that shows an overlap

of previously considered successive timeperiods.

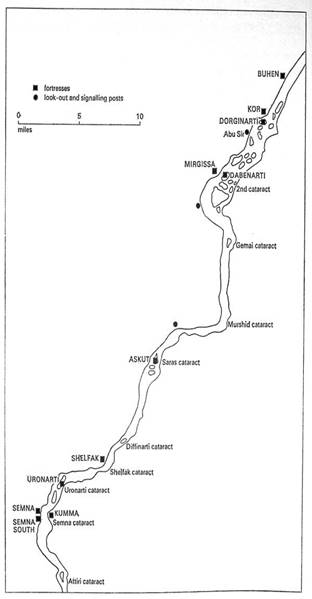

Egyptian forts in Lower Nubia, Northern

Sudan

Globalization

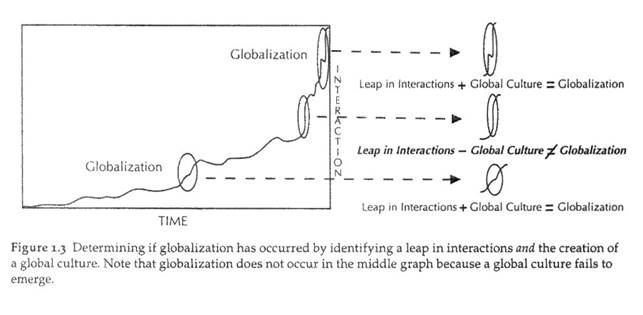

Globalization in present times can be regarded as an accelleration of a long term process, that has been research within Wallersteins world system of core periphery interactions, as a process of leaps in connectivity.

According to recent research in globalization processes in ancient societies, the phenomenon can be best described as a result of increasing interregional interactions (Jennings 2011:6) and hybridization (Jennings 2011: 10; Nederveen Pieterse 2004). Examples of ancient globalizations are the expansion of the Uruk culture in the fourth Millennium BC, the Mississippi in the United States, and the Huari culture, a Middle Horizon culture in the south central Andes region.

The Egyptian expansion to Lower Nubia at the beginning of the second millennium BC, has parallels with the increased connectivity that is characteristic for processes that are part of an ancient globalization. The construction of the forts along the Nile in Lower Nubia were initiated by Sesostris III, and the forts maintained a sealing system that points to a constant flow of goods and information between the forts, and the Theban residence up north. It is assumed that these forts functioned in the way that Egypt benefited from the Lower Nubian resources, by the lowering of transport costs (Smith 1995).

The nature of the Egyptian expansion into Lower Nubia is still being debated, in terms of ideology, trade, lowered costs, equilibrium, colonisation and imperialism (ST Smith 1995, Flammini 2009). However, the number of sealings discoverd in the forts could point to mass production during the late Middle Kingdom (Ben Tor 2007: 3), in comparison with the occurence of seals in the First Intermediate Period and early Middle Kingdom. The occurrence of Marl C (Upper Egyptian) pottery in Kerma, could suppose that the Second Cataract Forts played a significant part in the trade between Egypt and Nubia (Bourrieau 1995: 129-130), and the sealing system reflects an administrative standardization to a high degree (Smith 1990: 202), the importance of certain institutes. According to most researches on the Second Cataract Forts, an occupational gap is assumed at the end of the 13th Dynasty, the time when the transmission of the seal system could have taken place (Smith 1998: 224).

The use of a similar sealing system by the Kerma culture during the Second Intermediate Period, suggests an exchange that goes further than merely cultural and economic agents.

Socially, a change was established in Kerma in regard to secondary state formation and the growing power if the Kerman elite (Smith 1998: 226-227), which is actually the second criterium for a globalization leap in ancient societies as suggested by Jennings (2012: 12).

Artist impression of Fort Buhen

Wallerstein’s World-System

According to Jennings (2012), ancient globalizations have been researched as a modern phenomenon that “suddenly” could be spoken of, when it would have attained a certain level that we could call the beginning of modern globalization.

The other model is the idea that globalization is a gradual process that gets faster over a longer period of time. Jennings however has proposed a new view in which he sees globalization as a process of successive explosions of increasing interaction, and therefore globalization identifies multiple periods over time (Jennings 2012: 8-12).

The

world system model of Wallerstein has gained more importance in archaeology

(Kohl 1978, Blanton and Feinman 1984, Rowlands Larsen and Kristiansen 1978,

Champion 1989), in which production, exchange, and consumption are regarded as

unity, structures of inequality, and the combination of social and political

history (Edens 1992 121).

Flammini

summarises Wallerstein's (1974) three assumptions of the modern world system as

follows: Core dominance over the peripheries, secondly are symmetrical exchange

between regions, and trade as the prime cause of social development (Flammini

2008: 50). The problem of this theoretical approach is not always applicable to

non-capitalist societies, that is why the economic dimensions of core periphery

structures is mostly not given attention that it deserves (Edens 1992 121). Then again, the economic character of core

periphery relations is within the authoritative context of structured and class

divided societies that emphasises non-economic into regional forces in which

economic phenomenon is like trade and patterns of consumption are embedded. In

complex societies consumption is linked

with social ties, hierarchy domination and ideology (Edens 1992: 122).

Kohl (1987) is an advocate of the existence of

multiple core areas that integrate with one another, and that mostly the

peripheries were the places of technological innovation (Flammini 2008 :

50-51). Also Edens adheres to this by saying that core periphery relations were

not strong enough to create a world system as such, but he prefers to speak of

centre periphery structures (Edens 1992 134).

Flammini

points out that many ancient core periphery relationships processes in Lower

Nubia fit into the core driven model (2008: 51). She agrees with Chase Dunn and

Hall (1991) in regard to the definition of two different types of relationships

that exist between cores and peripheries. Core periphery differentiation is the

phenomenon of interaction without exploitation by the core, core periphery

hierarchy by which there is a political or economic dominance within the same

system (2008: 51). Nevertheless, emphasizing core domination neglects the

agency of native or local actors (Flammini 2008: 51; Smith 2003). Jennings

however, proposes an adjusted model of the world system, called a comparative

world systems approach (Jennings 2012: 13). He states that Wallerstein's

classical system is too much applied on modern societies, and he proposes a

more limited size of the system, less focus on a dominant core, a more active

role of the periphery, and above all more diverse connections between the two

zones (Jennings 2012: 12-13; Chase Dunn and Hall 1997: 12-15; Earle and D'

Altroy 1989; Kardulias 1999, 2007; Parkinson and Galaty 2007; Peregrine and

Feinman 1996; Schneider 1997; Stein 1999).

The

existence of the semiperiphery specifically defined as an area geographically

located between cores and peripheries that acts as an intermediate Flammini

2008: 51). The Egyptian forts in Lower Nubia could have played a part as such.

The

stratigraphy

The

Second Cataract Forts pose many challenges in research to the function and

motivation of the Egyptian presence during the Middle Kingdom and the Second

Intermetiate Period. Before research can be done properly, one has to take into

account the problems with lacking or the perceived lack of stratigraphy that

makes a diachronic analysis difficult.

The

forts of Buhen and Mirgissa were denuded, and the mixing of the deposits

resulted in a very unreliable context, and in Buhen's case, most of the

non-diagnostic pottery was saved (Smith 1995: 24; Emery et al. 1979: 93-94). In

Mirgissa's Inner Fort, deposits varied from 50 to 20 cm.

Semna

South was completely denuded, but the area around the fort was preserved better

(Smith 1995: 24; Zabkar and Zabkar 1982).

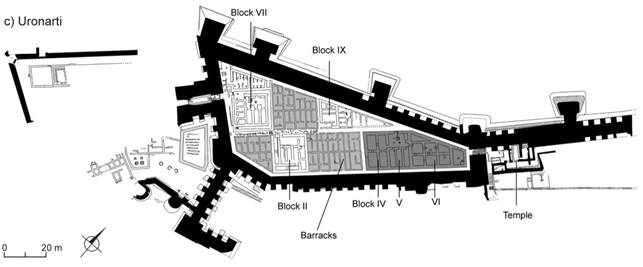

The

stratigraphy at Shalfak, Uronarti and Kumma were excavated in such a way that

research can not rely too heavily on the cultural layers, however at Uronarti,

a distinction has been made between

levels K, and B, and “lower” and “upper level”. In exceptional cases,

objects in the objectlists are registered with an accompanying height level

(Dunham 1967).

At

Askut however, the stratigraphy was preserved to 1.5 m in the Upper Fort and

between 0.2 and 0.5 m in the Southeastern Sector, which provided a much better

horizontal and vertical control of the “spiral stratigraphy” (Smith 1995: 24,

53; Knoblauch 2007: 226). Then again, it is important to make a difference

between the reliability of the date within and outside of structures.

The

inconsistencies in depth of deposits and dating could be explained by, on the

one hand, maintenance of floors, and abandonement of structures elsewhere in

Askut (Smith 1995:53) However, in Uronarti no such restructuring was found (Ben

Tor et al. 1999: 57). In general it is very difficult to make out clearly the

difference between 12th and 13th dynasty deposits, and

between Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period deposits (Ben Tor 2007:

5).

Fort Uronarti

Dating

through the pottery

Hemispherical

cups

Stuart

Tyson Smith's research on Askut, resulted in a continuous four phased pottery

sequence, that is invaluable for the Second Cataract Forts (Knoblauch 2007:

225). Besides that, it provides a context for the synchronization of the Middle

Bronze Age, the Middle Kingdom and the Nubian- Kerma cultures. Research to the

sealing system of the forts also relies on Smith's research (Ben Tor 2007, Ben

Tor/ Allen 1999).

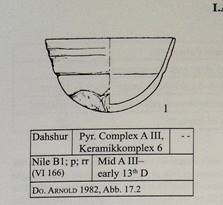

Pottery

has been accepted as the most reliable source for relative dating of

archaeological deposits (Ben Tor 1999: 53). However, Smith based his research

on the so-called Vessel Index of the pottery, in an attempt to bypass the

spiral stratigraphical contex that mainly existed within the barracks

structures at Askut, instead of the vertical relationship of the pottery in

itself. In his research the following sequence could be established in

comparison with Dorothea Arnold's research in Dashur:

Phase

1= Late 12th – Early 13th Dynasty = Dashur 6

Phase

2= Mid 13th Dynasty = intermediate phase between Dashur 6 and 7

Phase

3= Mid to Late 13th Dynasty = Dashur 7

Phase

4= Second Intermediate Period/ Upper Egyptian 17th Dynasty = Upper

Egyptian pottery types. (Knoblauch 2007: 226-228).

One

of the problems is that the publication of the Dashur corpus is not a final

one, and there are many objections to base a Lower Nubian ceramic sequence on a

Lower Egyptian one, in spite of the cultural influences of the Delta on the

forts during the centralized government of the Middle Kingdom. Smith's

assumptions are based on the absence of a regional development of the pottery,

standardization and import from the Delta (Knoblauch 2007: 228-229). Still,

Smith's use of the pottery from Dashur 7 makes sense in regard to the

abandonment of the royal funerary complex of Amenemhat III at the site. This is

an archaeological marker of the transition from the Middle Kingdom to the

Second Intermediate Period (Ben Tor 2004: 28). During the 12th

Dynasty, the rotating garrisons in the forts were being backed up by the

capital near El Lisht in the Delta, so a influx of Lower Egptian pottery in

Lower Nubia is assumed. During the 13th Dynasty, the settlers in the

forts were more independent form the Delta, and had close relationships with

Upper Egypt (Bourrieau 1997).

Knoblauch

proposes the origin of the hemispherical cups with a Vessel Index from

130-140 in Upper Egypt, specifically

Elephantine (von Pilgrim 1996) or Thebes (Moeller and Marouard 2011: 114), and

not the Delta. This results in the dating of certain contexts of the forts to a

later date, in the 17th Dynasty instead of mid-late 13th

Dynasty.

This

is also a complementary statement to the occurence of 17th Dynasty

jars in Building D/ Block VI at Uronarti, in which the major corpus of sealings

were found (Ben Tor/ Allen 1999: 57; Schiestl and Seiler 2012: 675). Knoblauch

however states that the vessel index in itself does not provide a reliable

dating, nor it reflects a specific pottery type (personal communication).

Example of a

hemispherical cup

Tell

el Yahidiya Ware

There

are three pieces of Tell el Yahudiya ware found at Uronarti. At Room F32, Room

26 and the South Passage (Dunham 1967: Figure 1). This pottery was also found

at Askut, and at both sites the ware is belonging to class Pyriform 1b-c (

Smith 2004: 210-212; Ben Tor et al 1999:

58).

According

to Bietak, this specific type of pottery can be dated to the mid-late 13th

Dynasty, as well as Askut (Smith 2004: 210) as Uronarti (Ben Tor 1999: 58), in

relation to Tell el Dab'a in the Delta.

Smith

relates the occurrence of Tell el Yahudiya ware in Askut to the ceramic

evidence at Tell el Dab'a on the one hand, but again to the Vessel Index

128-136 from Arnold and places the date in the advanced 13th

Dynasty, correlating with Dashur complex 7 (Smith 2004: 210).

The

association of this Tell el Yahidiya pottery with hemispherical cups that are

supposedly dated too early, together with assosiated sealings of M3-ib-R' king

of the 14th Dynasty, in Uronarti, proposes a date in that time, and

thus has implications for the supposed abandoning, and the sealing system of

the forts during this time.

“Gilt

ware”

Recently, the material from some of the Second Cataract Forts is being reviewed and researched with a fresh point of view. Christian Knoblauch (Knoblauch, C. 2011 All that glitters: A Case Study of Regional Aspects of Egyptian Middle Kingdom Pottery Production in Lower Nubia and the Second Cataract, Cahiers de la Céramique Egyptienne 9, 167-183) researches the pottery named by Reisner “gilt/gilded ware”, or pottery consisting of a “gilt polish”, “gilt wash” and “gilding”, abbreviated as “GW” in the Pottery Drawing Sheets. Koblauch states that this terminology corresponds to different manufacturing processes (Knoblauch, Cripel 9, 168).

Knoblauch's terminology for

this originally considered to be an independent pottery group as “micaceaous

slipped ware”, categorizes the pottery

according to the application of a slip layer containing mica, which gives the

pottery a romantic “golden” appearance.

This phenomenon occurs at

the Second Cataract Forts, however it is not an indication of a pottery type,

but a trend. Knoblauch concludes that it was a local Nubian adaptation to cover

Egyptian Middle Kingdom pottery with a micaceous layer, and this trend was

relatively short, dating from the Twelfth- Thirteenth Dynasties into the Second

Intermediate Period (Knoblauch, Cripel 9, 176).

Schiestl

and Seiler pottery types

When one goes through

original publications from the excavations for instance from the Nubian Second Cataract

Forts, one can feel lost in the abundance of recorded data. Unfortunately,

Reisner and Wheeler did not always use a standard way to describe the material

that was excavated in the forts during the 1920's and 1930's, and eventually

got published by Dunham and Janssen in 1960 and 1967 (1967 Second Cataract Forts Volume I + II.

Uronarti, Shalfak; Semna- Kumma Mirgissa Boston).

Recently,

Schiestl and Seiler (2012, Volumes I and II) have published a database of

Middle Kingdom pottery from published and unpublished sources. By means of

cross referencing, they provide a new overview on Middle Kingdom Pottery in

Egypt, Nubia and the Levant.

Also

the original Pottery Sheets from Dunham and Janssen (1960) and Dunham (1967)

concerning the Second Cataract Forts were being reviewed and categorized by

Schiestl and Seiler.

From

these, for 46 pottery types (and subtypes) that occur in the Lower Nubian

forts, a (fine) dating range is provided, which makes a diachronic relation

between the forts possible.

Schiestl

and Seiler also deal with certain groups of “hemispherical cups” but unlike

Smith, they only use the types from which a certain degree of standardization

is established, in order to make an attempt to correlate context different from

Tell el Dab'a or Dashur. According to the authors, only shape group I.A.14

(hemisperical cups, group 6) has been identified as with certainty in Lower

Egypt and Lower Nubia (Schiestl and Seiler 2012: 84, 108). However group I.A.12

is also present at the fort of Uronarti.

The

seals themselves

The

high occurrence of scarabs in the Levant and Egypt during the second millennium

BC resulted in research to a reliable chronological typology. This is still

inconclusive due to the stylistic developement, the post quem use of royal

names, their use as heirlooms.

When

one turns to scarab seals in a clear archaeological context, the absolute

dating and historical conclusions are still controversial (Ben Tor 2007: 1-2).

The scarab seals are however very useful in the historical recontruction of the

first half of the second millennium BC, the same time as the second cararact

forts in Lower Nubia. Recent research by Ben Tor can shed light on the

historical background that resulted in the mass production of scarabs during

the Late Middle Kingdom (Ben Tor 2007: 3), and their possible use during the

Second Intermediate Period. It is important to clearly make a distiction

between official seals, private seals, counterseals and royal seals, and seals

portraying a royal name.

Ben

Tor eventually uses very broad definitions for the phases to group the scarabs:

early Middle Kingdom, Late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period.

Together with the new pottery research of Knoblauch and Schiestl and Seiler, it

is possible to give a more precise date to the 2233 scarab sealings that have

been found in situ in Building D at Uronarti (Smith 1998: 222) , and thus has

implications for the dating of the sealings found in other Second Cataract

forts, and the sealings in Kerma.

Ben

Tor (2007) bases her research on the study of Tufnell and Ward (1975) who dated

the seals of Uronarti to the end of the 12th Dynasty (Tufnell 1975:

69). Ryholt and Reisner thought the seals to be dated to the early 13th

Dynasty (Ben Tor 1999: 55). Later research pointed out that the seals from

Uronarti (specifically Building D) would probably date to the advanced 13th

Dynasty/ Early Second Intermediate Period (Ben Tor 2007: 9; Smith 1990:206-207;

Kemp 1986), and specifically the last year(s) of occupation (Ben Tor 1999: 56;

Smith 1990).

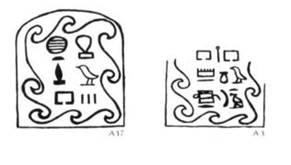

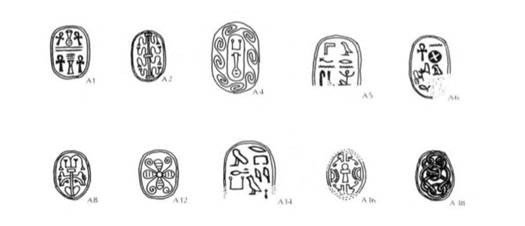

Example

of institutional seals

Examples

of counterseals that were found stamped on institutional seals

Ben

Tor (2007) refers to a selection of the many seals in Uronarti, not the entire

corpus. She decribes various design types for the early-and Late Middle

Kingdom, and some types overlap (2007). A review of the seals that she did not

incorporate in her study could be considered, in regard to the stylistic dating

of the seals, and their association with the revised pottery.

There

are several seals found that could date to the Second Intermediate Period,

according to royal name scarabs from Hyksos kings from the 14th-17th

Dynasties (Ben Tor 2007, 2010).

Recent

research on sealings from the Hyskos at Tell Edfu, has pointed out close

similarities between the sealings of Khayan from Tell Edfu and sealings of

Hyksos kings Yabubhar and Shesi/ M3-ib-re, found at Uronarti. Besides that,

sealings of Khayan have been found in Tell Edfu in a closed archaeological

context together with Late Middle Kingdom seals. This points to contacts

between the Hyksos and Upper Egypt, and also a possible overlap of the late 13th

Dynasty and the 15th Dynasty (Moeller and Marouard 2011:109).

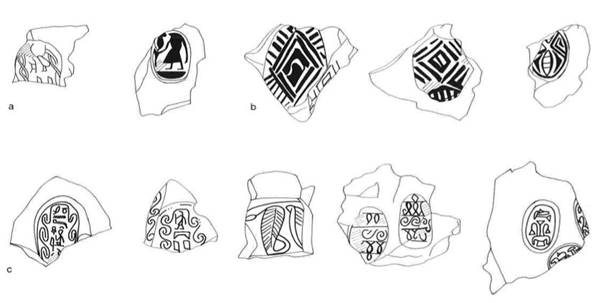

At

Kerma, many scarabs have been found in a burial context, dating from the Second

Intermediate period, specifically the late Classic Kerma phase.

At

location K1 at the Western Duffufa (main religious complex), cemetery chapel

KX1, in in from of the door in front of the tumulus KX, 101 types distibuted

over 765 sealings, have been found (Smith 1998; Bonnet 2001; Gratien 1991).

This is in indicator of administrative activity (Reinser 1923: 81-84). Apart

from sealings that reflect local Nubian designs (Gratien 2004: 78), these

sealings have close parallels with the ones found at the Egyptian second

cataract forts. However, the system seems less complex than the system at

Uronarti, that consisted of archival sealing and countersealing.

Examples

of seals found at Kerma, Upper Nubia. One can see clearly the Middle Egyptian style,

and a local Nubian style

According

to Smith (1998: 224) this system could have been transmitted at the end of the

13th Dynasty, during a supposed occupational gap. During the second

intermediate period, it is thought that such sealings were only used in Kerma,

not in Egypt (Ben Tor 2007: 62) apart from some sealings from Uronarti that

could be stylictically attibuted to the Second Intermediate Period (Ben Tor

2007: 47).

This

seems to be an outdated conclusion. With the new pottery research of the forts,

that could point to the 17th Dynasty as a date of the seals in

Building D at Uronarti, together with the overlap of the late 13th

and the 15th Dynasty, this has implications for the chronology of

the Late Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate period in Nubia, and the

ongoing increasing contacts between the Hyksos in the Delta, the Upper Egyptian

Dynasties and Kerma.

Methodology

The

material for this research, the pottery and the seals need first to be

correlated in such a way that several restricted time periods can be

established, that correlate between the rooms of the several forts. The pottery

provides a fine dating, that can be as detailed as “second quarter of the 13th

Dynasty” but sometimes a very broad 11th to 13th Dynasty

date can only be found.

With

the broad dating of the pottery, the research should take the possible dating

of the sealings themselves into account, and this highly depending on cross

referencing with other sites with closed archaeological contexts.

In

the second cataract forts, some pottery consists of Nile clay, that could point

to import from the Delta. One can trace the proportion of

imported cooking wares, storage jars, table wares, etc., in a determined number

of sites, and this can tell you which kind of relationship (immigration, trade,

colonialism, etc.) the forts had with

Lower Egypt. Pottery that would be produced in the region of Upper

Egypt, would be in general consisting of Marl clays. However, a large group of

Marl A3 ware, would have been imported into Nubia (Schiestl and Seiler 2012:

25).

With a vertical analysis you

can study the numerical proportion of imported and locally produced items, or

of specific kinds of imported items, through the different “strata” in the

forts. So you will have a measure of the contacts of one or several sites with

neighbouring regions through different periods. In this case you will know the

temporal distribution of imported items,

but not yet the cause of that, for example trade.

With a horizontal analysis

you can study the numerical proportion of imported or local items, in different sites. You will have a measure

of the contacts of different sites or

geographical areas with neighbouring regions.

If the sample is

representative enough, you can plot the fall off (i.e. a decreasing curve of

number of objects through

different sites) between different sites or areas, and the

characteristics of the

resulting curve can tell you which kind of depositional process (trade,

gift-giving, colonialism,

etc.) was the cause of such curve. (Tebes, personal communication).

This

will also answer the use of the sealing system (archival or not), and the

timeframe of the transmission to Kerma, and insight in the chronology of the

Late Middle Kingdom in regard to the Second Intermediate period, especially the

Theban 17th Dynasty.

The

mass production of the scarab seals during the Late Middle Kingdom/ Second

Intermediate Period, could point to a globalization leap characterised by

interconnectivity. The transmission of the Egyptian sealing system in Kerma, is

a social change, due to the contact with Egypt. Possibly the Egyptian

institutes indicated by the seals remained in use not until the Late Middle

Kingdom, but even during the Second Intermediate period, and maybe were even

adopted as such by the Kerman people.

The

possible prolonged use of the institutes is an indication of the ongoing

Egyptian influence and centralized state that was characteristic of the Middle

Kingdom, and research to this contributes to the chronology of the much debated

timeframe of the Second Intermediate Period, that could be shorter, or a more

contemporary with the Middle Kingdom, than traditionally assumed.

Selected

Bibliography

Ben-Tor, D. 2007 Scarabs,

chronologies and interconnections:Egypt and Palestine

in the Second Intermediate Period,

Academic Press Tribourg, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Gottingen

Ben Tor, D. and Allen, J. and

Allen S. 1999 Seals and Kings, Bulletin of the American

Schools of Oriental Research No. 315 (Aug., 1999), p.

47-74

Ben Tor , D. 2004 Egyptian-

Levantine relations and chronology in the Middle Bronze Age: scarab research,

in The

synchronisation of civilisations

in the eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. II, Proceedings of Sciem 2000, eds. By Bietak, M.p. 239-248

Blanton, R. and Feinman, G. M. 1984. The Mesoamerican World-System. American Anthropologist (86 ed.): p. 673–682.

Bonnet, C. 2001 Charles BONNET : Les empreintes

de sceaux et les sceaux de Kerma : localisation des découvertes,

CRIPEL 22, Champion, T.C. ed.

1989

Bourriau, J. 1991 Relations between

Egypt and Kerma during the Middle and New Kingdoms.

in Egypt and Africa.

Nubia from the Prehistory to

Islam. (edited by W.V. Davies). London. p. 129-144

Chase-Dunn, C. and Hall,T. 1991 Conceptualizing Core/Periphery Hierarchies for

Comparative Study. p.. 5-44 in Core/Periphery

Relations

in Precapitalist Worlds, edited by C. Chase-Dunn and T. Hall. 2d ed. Boulder, CO:

Westview Press

Dunham, D. 1967 Second

Cataract Forts: Uronarti, Shalfak,

Mirgissa / excavated by George Andrew Reisner, and

Noel F. Wheeler, Dows Dunham

Earle, T. and D’Altroy, T. 1989 The Political Economy of the Inka Empire:

The Archaeology of Power and Finance. In

Archaeological Thought in

America, ed. C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, p. 183-204.

Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Edens, C. 1992 Dynamics of Trade in

the Ancient Mesopotamian "World System” American

Anthropologist, New

Series, Vol. 94, No. 1 (Mar.,

1992), p. 118-139

Emery, W. B. Smith, H.S. and

Millard, A. 1979. The Fortress of Buhen: The

Archaeological Report. London.

Gratien, B. 1991 Empreintes

de sceaux et administration à Kerma

(Kerma classique », in Kerma 1988-1989

- 1989-

1990 - 1990-1991, Genava, n.s., t. XXXIX, p. 21-23.

__________2004 Administrative

practices and movements of goods between Egypt and Kush during the Middle

Kingdom and the Second

Intermediate Period», dans T. Kendall (éd.), Nubian studies 1998, Boston,

2004, p. 74-82.

___________2006 Au sujet des Nubiens dans les forteresses égyptiennes de la deuxième cataracteau Moyen Empire et

à la Deuxième

Période Intermédiaire», dans B. Gratien (éd.), Mélanges offerts à Francis Geus,

CRIPEL 26, 2006-2007, p. 151-162.

Jennings. J. 2011 Globalizations and the ancient world,

Cambridge University Press, New York.

Flammini, R. 2009: Ancient

core-periphery interactions: Lower Nubia during Middle KingdomEgypt

(ca. 2050- 1640 B.C. Journal of World System Research ,Vol. XIV number 1, p.

50-74

Kardulias, P. N. (1999). Flaked stone

and the role of the palaces in the Mycenaeanworld

system. In Parkinson, W. A., and Galaty, M. (eds.), Rethinking Mycenaean Palaces: NewInterpretations

of an Old Idea ,Institute of Archaeology,

University of California, LosAngeles, p. 61–71.

Kardulias, P. N. (2007). Negotiation

and incorporation on the margins of worldsystems: Examples

from Cyprus and North America. Journal of World-Systems Research 13:p. 5–82

Knoblauch, C. 2007 Askut in Nubia: A re-examination of the Ceramic Chronology,

in K. Endrefy and A. Gulyas (eds.)

Proceedings

of the Fourth Conference of Young Egyptologists, Studia Aegyptiaca

XVIII, Budapest,

225-238

____________ 2011 All that glitters: A Case Study of Regional Aspects of Egyptian Middle

Kingdom Pottery

Production in Lower Nubia and

the Second Cataract, Cahiers de la Céramique Egyptienne 9, 167-183

Kohl. P.L. 1978 The balance of

trade in southwestern Asia in the mid-third Millennium B.C. Current Anthropoloy,

Vol. 19, No. 3 (Sep., 1978),

pp. 463-492 University of Chicago Press

Moeller, N. and Marouard, G. with a contribution by Ayers, N. 2011 Khayan Sealings from Tell Edfu, in: Ägypten und Levante

XXI, , 87-121

Nederveen Pieterse,

J. 2012 Periodizing Globalization: Histories of

Globalization, University of California- Santa Barbara

Parkinson, W. A., and Galaty, M. (2007). Secondary states in perspective: An

integrated approach to stateformation in the

prehistoric Aegean. American Anthropologist

109: 113–129

Peregrine, P. N., and Feinman, G. M. (eds.) (1996). Pre-Columbian World Systems,

Prehistory Press,Madison, WI.

Reisner. G. A. 1923a Excavations at Kerma I-III. Harward African

Studies 5. Cambridge Mass.

Reisner. G. A. 1923b Excavations at Kerma IV-V. Harward African

Studies 6. Cambridge Mass.

Rowlands, M.,Larsen,

M.T. & Kristiansen,K. eds. 1987. Centre and

Periphery in the Ancient World, Cambridge University Press, New Directions in Archaeology

Robert Schiestl, Anne Seiler. 2012 Handbook of Pottery of

the Egyptian Middle Kingdom. Volume I: The Corpus Volume, Volume II:

The Regional Volume.

Schneider, J. 1977 Was there a

pre-capitalist world-system? Peasant Studies 6: p. 20–29.

Smith, S.T. 1995 Askut in Nubia: the economics and ideology of Egyptian

Imperialism in the second millennium

B.C., London and New York,

Kegan Paul International

__________ 1998 The

transmission of and administrative sealing system from Lower Nubia to Kerma, CRIPEL 17, p.

219-230, Universite

Charles de Gaulle, Lille.

Stein, G. 1999 Rethinking

World-Systems. Diasporas, Colonies, and Interaction in Uruk

Mesopotamia, University

of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Tufnell, O. 1975 Seal impression

from Kahun town and Uronarti

Fort, Journal of Egyptian archaeology 61, p. 67-

101, The Egyptian Exploration

Society, London.

Zabkar, L.V. And Zabkar,

J.J. 1982 Semna South. A Preliminary Report on the

1966-68 Excavations of the University of Chicago

Oriental Institute Expedition

to Sudanese Nubia, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt vol. 19, p.

7-50