Uneven Political

Development:

Largest

Empires in Ten

world Regions and the Central International System since the Late Bronze Age*

Christopher

Chase-Dunn, Hiroko Inoue, Alexis Alvarez,

Rebecca

Alvarez, E. N. Anderson and Teresa Neal

Institute

for Research on World-Systems

University

of California, Riverside

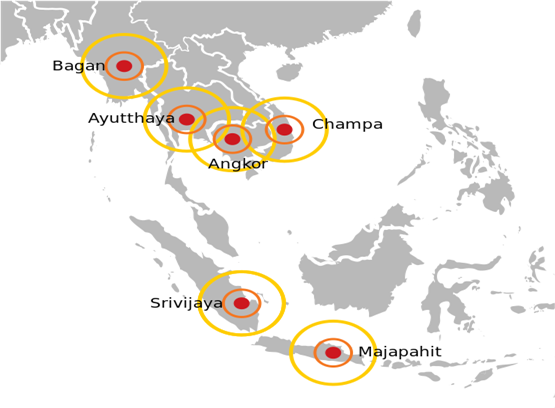

Galactic or mandala polities

in Southeast Asia

To be presented at

the annual conference of the California

Sociological Association,

Holiday Inn -- Capitol Plaza (near

Old Town) Sacramento, November 13 and

14, 2015

An

earlier version was presented at the Fourth European Congress on World and

Global History, September 6, 2014, École Normale Supérieure, Paris

Draft

v. 11-16-15, 11102 words

*We are indebted to those prodigious coders who made quantitative

comparative studies of settlements and polities possible: Tertius Chandler, Rein Taagepera and George Modelski.

![]()

This is IROWS Working Paper #85

available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows85/irows85.htm

Data

appendix for this paper is at https://irows.ucr.edu/cd/appendices/worregs/worregsapp.htm

Abstract:

This is a part of a study of the growth of settlements and polities in ten world regions over the past 3500 years. We discuss changes in the relationships linking political/military power, economic power and settlement systems. And we compare East Asian urban and empire growth with the original heartland of cities and states in Southwest Asia and Africa, as well as with Europe, the subcontinent of South Asia, Central Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania and the Americas. This quantitative measurement of the trajectories of largest city and empire growth and the changing relative scale of social organization in the different world regions provides an overall picture of the long-term patterns of uneven development in human sociocultural evolution and has important implications for analyses of the similarities and differences between the developmental trajectories of the world regions studied. We also investigate the extent to which the growth/decline phases of cities and empires in different world regions display synchrony or a see-saw (alternating) pattern across the centuries.

The

study of the long-run growth of settlements and polities is an important basis

of our understanding of comparative sociology and human sociocultural

evolution.[1] The processes by which a world inhabited by

small nomadic hunter-gatherer bands of humans became the single global

political economy of today involved the establishment and growth of

settlements, the expansion of interaction networks and the growing size of

polities. These processes of long-term growth and expansion were uneven in time

and space. There were cycles of growth

and decline. And some of those regions that originally developed larger cities

and polities were, in later epochs, no longer the leading regions.

Our

theoretical approach is the institutional

materialist comparative evolutionary world-systems perspective. World-systems are defined as being composed of those human

settlements[2]

and polities [3]

within a region that are importantly interacting with one

another. This

approach focuses on the ways that humans have organized social production and

distribution, and how economic, political, and religious institutions have

evolved in systems of interacting polities (world-systems) since the

Paleolithic Age. We employ an underlying model in which population pressures

and interpolity competition and conflict have always

been, and still remain, important causes of social change, while the systemic

logics of social reproduction and growth have gone through qualitative

transformations[4]

(Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014: Chapter 2). Our larger

research project studies the development of settlements and polities by

comparing regional world-systems and studying them over long periods of time.[5]

Our approach to the spatial bounding of the

unit of analysis is very different from those who try to comprehend a single

global system that has existed for thousands of years. Gerhard Lenski (2005); Andre Gunder Frank

and Barry Gills (1994) and George Modelski (2002; and

Modelski, Devezas and

Thompson 2008) and Sing Chew (2001; 2007) all analyze the entire globe as a

single system over the past several thousand years. We contend that this

approach misses very important differences in the nature and timing of the

development of complexity and hierarchy in different world regions. Combining

apples and oranges into a single global bowl of fruit is a major mistake that

makes it more difficult to both describe and explain social change. Our

comparison of different world regions and interaction networks of polities

makes it possible to discover both the similarities and the differences. Global

comparisons among these regional systems are certainly appropriate, but the

claim that there has always been a single global world-system is profoundly

misleading. [6]

Our earlier studies have used data on city sizes and the territorial sizes of empires to examine and compare different regional interaction systems (e.g. Chase-Dunn, Manning and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and Manning 2002; Inoue et al 2012; Inoue et al 2015). This article is a re-examination of the empire size data that uses better estimates and that will enable us to address claims about the relative importance of China and Europe that have been advanced by Andre Gunder Frank (1998) and more recently by Ian Morris (2010; 2012) and to reflect on the similarities and differences of the trajectories of development in the ten world regions we are studying.

The question we will try to answer in this article is: what

can patterns of polity growth tell us about the trajectories of development of

the different world regions and the expanding Central System? This paper is the

second part of a study that also uses the sizes of largest cities in world

regions to examine the nature of uneven development (Chase-Dunn, Inoue, A.

Alvarez, R. Alvarez, Anderson and Neal 2015).[7] But this paper looks only

at the sizes of the largest polities in each world region.

The issue of systemness and the spatial boundaries of whole

human systems remains contentious in social science. The description of

Earth-wide “global” history and processes is certainly a valid exercise, but

the question of bounding whole systems is more complicated. It depends on what

is meant by systemness. The idea of a whole system requires

being explicit about what is within the system and what is designated as

exogenous. Some explicit world-systems theoretical approaches claim that the

whole of humanity has constituted a single world-system since the emergence of

modern humans. This position has been explicitly taken by Gerhard Lenski (2005). Andre Gunder Frank and Barry Gills (1994) contended

that what they call “the world

system” emerged when states and cities arose in

Mesopotamia 5000 years ago. Frank

and Gills (1993:16, 84-85) designated a number of turning points of gradual

inclusion of world regions into the world system. Five thousand years ago

it was constituted only as Egypt and Mesopotamia, but China and the rest of

Eurasia became part of the system around 500 BC, and the incorporation of

Americas occurred after 1492. Their position was adopted by Sing

Chew 2001; 2007, but see 2014).

Immanuel Wallerstein

(2011[1974]) contended that the modern world-system was not yet global when it

emerged in Europe and the Americas in the long 16th century CE.

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1993; 1997) defined world-systems as human interaction

networks in which the interactions were two-way and regular. They adopted a

place-centric approach to spatially bounding world-systems because of the

observation that all human groups interact with their neighbors and so if you

count all indirect connections there has been a single linked network since the

humans populated the continents. The ideas of “fall-off” of effects of

interaction and place-centricity were adopted from archaeology.

The study of world

regions that we have undertaken here is not meant to confound the spatial

bounding of whole human interaction systems by means of interaction networks.

Rather it is intended to shed light on the literature that has emerged from the

critique of Eurocentrism and the rise of other centrisms.

We acknowledge that Eurocentrism has had huge detrimental effects on the

efforts of social scientists to describe and explain human sociocultural

evolution. And we agree that looking at reality from different perspectives is

a valuable exercise that can be enlightening and make big contributions to the

effort to explain the human past and present. We contend that the methodological

approach developed by Chase-Dunn and Hall for spatially bounding world-systems

is capable of providing a non-centric (or cosmocentric)

method for comparing small, medium-sized and large whole human systems. This

said, we admit that important work still needs to be done to accurately specify

the timing and location of changes in the spatial boundaries of world-systems (see

Chase-Dunn, Wilkinson, Anderson, Inoue and Denemark

2015).

Results of Our Earlier Studies of

Scale Changes of Polities and Settlements

Our studies have used data on city sizes and

the territorial sizes of empires to examine and compare different regional

interaction systems (e.g. Chase-Dunn, Manning and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and

Manning 2002; Inoue et al 2012; Inoue

et al 2015). We have identified those instances in world

history for which quantitative indicators are available in which the scale of

polities and settlements have greatly increased. These are termed upsweeps

(Inoue et al 2012; Inoue et al 2015). We also identify downsweeps

and system-wide collapses in which the largest polities or settlements declined

below the level of the previous low point and stayed down for more than one

typical cycle. Using this method we found that, while the decline of individual

cities and empires was part of the normal cycle of rise and fall, there were

very few system-wide collapses in which a downsweep

was not followed very soon by another rise.

We also found a greater

rate of urban cycles in the Western (Central) system than in the East Asian

system, which supports the usual notion that the Western city system was less

stable than the Eastern city system. And our finding that the Central system

experienced two urban collapses, while the Eastern system experienced downsweeps but not collapses, supports the idea of greater

stability in the East. We found that nine of the eighteen urban upsweeps we

identified were produced by semiperipheral

development and eight directly followed, and were caused by, upsweeps in the

territorial sizes of polities.

We also

examined twenty-four upward sweeps of the largest polities in four world

regions and in the expanding Central interpolity

system since the Bronze Age to determine whether or not the upsweeps were (or

were not) semiperipheral marcher states. (Inoue, Álvarez,

Anderson, Lawrence, Neal, Khutkyy, Nagy and

Chase-Dunn 2013). We found that over half of the twenty-two

identified empire upsweeps were likely to have been produced by marcher states

from the semiperiphery (10) or from the periphery

(3). This means that the hypothesis of semiperipheral

development does not explain everything about the events in which polity sizes

significantly increased in geographical scale, but also that semiperipheral development must not be ignored in any

explanation of the long-term trend in the rise of polity sizes.

Relative Regional Complexity

Andre

Gunder Frank’s (1998) provocative study of the global

economy from 1400 to 1800 CE contended

that China had long been the center of an already global system. Frank also

argued that the rise of European power was a sudden and conjunctural development

caused by the emergence in 18th century China of a “high level

equilibrium trap” and the success of Europeans in using bullion extracted from

the Americas to buy their way into Chinese technological, financial and

productive success. Frank contended that

European hegemony was fragile from the start and will be short-lived with a

predicted new rise of Chinese global predominance in the near future. He also

argued that scholarly ignorance of the importance of China invalidates all the

social science theories that have mistakenly characterized the rise of the West

and the differences between the East and the West. In Frank’s view there never

was a transition from feudalism to capitalism that distinguished Europe from

other regions of the world. He argued that the basic dynamics of development

have been similar in the single global system for 5000 years (Frank and Gills

1994).

A

related effort to compare world regions as a window on relative sociocultural

evolution is contained in two recent books by Ian Morris (2010; 2012). Morris’s big idea is

that complex human systems, like other complex systems, need to capture free

energy in order to support greater scale and complexity, and that the ability

to capture free energy is the main variable that accounts for the growth of

cities and empires in human history. Morris traces the increasing size of human

settlements since the origins of sedentism in the Levant

about 12,000 years ago. And he uses estimates of the sizes of the largest

settlements in world regions as a main indicator of system complexity. Using

this method he notes that there was parallel evolution of sociocultural

complexity in Western Asia and Northern Africa, South Asia, East Asia, the

Andes and Mesoamerica, and that the leading edge of the development of

complexity diffused also from its points of origin. And sometimes the original

centers of complexity lost pride of place because new centers emerged out on

the edge. The Bronze Age Mesopotamian heartland of cities now has none of the

world’s largest cities. Development was spatially uneven in some regions, with

the center moving to new areas.

In the introductory chapter of The Measure of Civilization Morris

provides a useful overview of earlier efforts to measure social development,

and he also provides a helpful and insightful discussion of the social science

literature on sociocultural evolution since Herbert Spencer. Morris’s research is

unusual for an historian because he carefully defines his concepts, specifies

his assumptions and operationalizes his measures, and then uses the best

quantitative estimates of settlement sizes as the main basis of the story he is

telling. His estimates of the sizes of the largest cities utilize, and improve

upon, earlier compendia of city sizes.

The main focus of Morris’s Why the West Rules is the comparison of

what happened in Western Asia, the Mediterranean and Europe with what happened

in East Asia. Morris is careful to trace the histories of the diffusion of

complexity in these areas. Morris makes contemporaneous comparisons between the

East Asian and Western regions in which he notes the existence of a see-saw

pattern back and forth regarding which region was ahead or behind in the

development of sociocultural complexity.

The West (Western Asia) had an original head-start, but the East caught

up and passed, and then the West (Europe and North America) passed the East

again.

While The Measure of Civilization is about the quantitative basis of

Morris’s analysis, Why the West Rules

adds a lot of detail beyond the basic focus on energy capture. But the energy capture idea misses some of

the patterns that are of interest to those who want to study whole

world-systems over long historical time. The story tends to be rather

core-centric with little attention paid to the transformative roles played by

peripheral and semiperipheral marcher states and

city-states in the construction of large empires and the expansion of trade

networks. Morris does not discuss the

transformation of systemic logics of development over the long period he

studied, or how differences in the development of capitalism may have been an

important contributor to the rise of Europe.

But the foregrounding of energy and cities is a valuable strategy for

comprehending both the patterns of history and for considering the present and

the future of human sociocultural development.

Immanuel Wallerstein’s (2011 [1974]) analysis

of East-West similarities and differences that account for the rise of

predominant capitalism in Europe and the continued predominance of the

tributary logic in East Asia is presented in Chapter One of Volume 1 of The Modern World-System. Summing up his

detailed discussion of the main factors that account for the East/West

divergence, Wallerstein says:

The essential difference between China and

Europe reflects once again the conjuncture of a secular trend with a more

immediate economic cycle. The long-term secular trend goes back to the ancient

empires of Rome and China, the ways in which and the degree to which they

disintegrated. While the Roman framework remained a thin memory whose medieval

reality was mediated largely by a common church, the Chinese managed to retain

an imperial political structure, albeit a weakened one. This was the difference

between a feudal system and a world-empire based on a prebendal

bureaucracy. China could maintain a more advanced economy in many ways than

Europe as a result of this. And quite possibly the degree of exploitation of

the peasantry over a thousand years was less. To this given, we must add the

more recent agronomic thrusts of each, of Europe toward cattle and wheat, and

of China toward rice. The latter requiring less space but more men, the secular

pinch hit the two systems in different ways. Europe needed to expand

geographically more than China did. And to the extent that some groups in China

might have found expansion rewarding, they were restrained by the fact that

crucial decisions were centralized in an imperial framework that had to concern

itself first and foremost with short-run maintenance of the political

equilibrium of its world-system. So China, if anything seemingly better placed prima

facie to move forward to capitalism in terms of already having an extensive

state bureaucracy, being further advanced in terms of the monetization of the

economy and possibly of technology as well, was nonetheless less well placed

after all. It was burdened by an imperial political structure (p. 63).

We now know much more about China because of

the careful comparative work of the “California School” of world historians

(e.g., Bin Wong 1997; Kenneth Pomeranz 2001) and

Giovanni Arrighi’s Adam Smith in Beijing (2007) as well as the important collection of essays in Arrighi, Hamashita,

and Selden (2003).

But Wallerstein’s analysis of the main elements explaining the East/West

divergence since the sixteenth century is still the best because of its

fruitful combination of millennial and conjunctural

time scales.

Frank’s

model of development in Reorient focuses mainly on state expansion and

financial accumulation. His study of global flows of specie, especially silver,

was an important contribution to our understanding of what happened between

1400 and 1800 CE (see also Flynn 1996).

Frank also uses demographic weight, and especially population growth and

growth of the size of cities, as an indicator of relative developmental

success.

It

is our intention to systematically examine the growth of the largest

settlements and polities in order to shed more light on Frank’s and Morris’s

claims about the relative development of East and West. Our study will begin in

1500 BCE when we first have reliable absolute years for the population sizes of

cities and the territorial sizes of states and empires in different world

regions.

Chronologies for Comparative Analysis

For purposes of comparing the timing of changes

in city and polity sizes across different world regions it is important to have

accurate absolute chronologies for the regions being compared. Unfortunately

there is still considerable disagreement about the absolute dating for

Mesopotamia before 1500 BCE. Mario Liverani (2014:

9-16) explains why estimates of absolute dates are so uncertain. Relative dates

of events needed for estimating polity sizes are based on “king lists.” Thus an

event, such as a conquest, is said to have occurred in the third year of the

reign of King X. Considerable effort has been made to figure out the

correspondences between different king lists in Mesopotamia and their

correspondence with Egyptian king lists. These are then converted in to

calendar years by ascertaining their relationships with astronomical events

such as eclipses. Unfortunately there is a period after the fall of the

Babylonian empire in which king lists are missing for Mesopotamia, and there is

disagreement about the timing of astronomical events. Thus the length in years

of the occluded period is in dispute, and this results in so-called, short,

medium and long chronologies for the period before the Late Bronze Age, with an

error of as much as 100 years.[8]

Our efforts to estimate the sizes of polities are dependent on absolute dating

because we want to compare across world regions. So it matters to us

whether Ur was sacked in 2004 BCE, and thus is eliminated from the list of

large cities and large polities in 2000 BCE, or in some other year 50 years

earlier or later. Liverani (2014: 15) is satisfied to

use the middle chronology for Mesopotamia and the surrounding regions, but he

is not trying to compare the timing of changes in the Ancient Southwest Asia

with other world regions. So we begin in 1500 BCE.

Another temporal issue that we

should mention is the effort we have made to code the sizes of polities as

snap-shots taken every 100 years.

George Modelski (2003) had already organized

the city population estimates into 100 year intervals, but Rein Taagepera’s (1978a;1978b; 1979; 1997) estimates of polity

sizes were organized according to the year of the events that caused changes in

the sizes of polities, mainly conquests and rebellions. In order to be able to

compare city and polity sizes we converted Taagepera’s

estimates to the same time points as we are using for cities by means of

interpolation. We also improved upon Taagepera’s estimates by using more recent Atlases and web

sources such as Geacron and Wikipedia that have

information about the history of polities. But using 100-year snap-shots could

miss some important developments that are relevant to the study of scale

changes in polity and city sizes. So, for example, in

order not to miss the huge but short-lived Mongol Empire we have added 1250 CE

as a time point.

Units of analysis: world regions and interaction

networks

The comparative evolutionary world-systems perspective spatially bounds world-systems as networks of interacting polities (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 3; Chase-Dunn and Jorgenson 2003). In most of our studies we use political/military interaction networks (PMNs) composed of fighting and allying polities as the unit of analysis. But in this paper we want to examine the different trajectories of world regions. PMNs have the disadvantage that they expanded and contracted over time as smaller regional networks merged or were engulfed by larger systems, eventuating in the single global system of today. Thus all the world regions eventually became incorporated into a single global network that we call the Central International System, following Wilkinson (1987).[9] In order to compare the trajectories of different world regions, which is the main purpose of this article, we will hold the spatial boundaries of the ten specified different regions constant over time. This allows us to trace the timing and trajectories of changes in the spatial scale of settlements and polities without worry that the changes we find are due to alterations in the spatial boundaries of the regions we are studying. We will also want to compare our constant region findings with studies of expanding political-military networks, especially the Central PMN.

Thus the main unit of

analysis in this study is the world region, and regions are held

constant over the whole period. The ten

regions we will study are:

1.

Europe, including the Mediterranean and

Aegean islands, that part of the Eurasian continent to the west of the Caucasus

Mountains, but not Asia Minor (now most of Turkey).

2. Southwest Asia- Asia Minor (now Turkey), the Arabian Peninsula, Mesopotamia, Syria, Persia, the Levant, and Bactria (Afghanistan), but not north of Afghanistan.

3. Africa, including

Madagascar.

4. The South Asian

subcontinent, including the Indus river valley and Sri Lanka.

5. East Asia,

including China, Korea, Japan and Manchuria.

6. Central Asia and

Siberia: We define Central Asia broadly as:

the territory that lies between the eastern edge of the Caspian Sea

(longitude E53) and the old Jade Gate near the city of Dun Huang near longitude

E95, and that is north of latitude N37, (which is the northern edge of the

Iranian Plateau, the northern part of Afghanistan and the mountains along the

southern edge of the Tarim Basin). The northern

boundary is the northern edge of the steppes as they transition into forest and

tundra. So the Central Asia region we are studying includes deserts, mountains

and grasslands (steppes) (Hall et al

2009).

7. Southeast Asia,

including Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Cambodia, Burma, Vietnam and

Thailand.[10]

8. Oceania, the islands of

the Pacific including Australia, New Zealand and Borneo (Papua and Papua New

Guinea).

9. North and Central

America

10. South America,

including Panama and the Caribbean Islands

For some purposes we will also use the expanding Central PMN as a unit of comparison.

The ten specified world regions are defined for

purposes of examining the claims made by Frank and Morris about relative

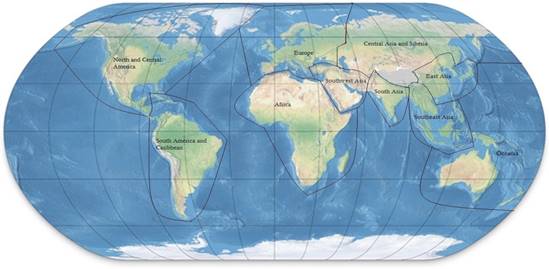

development of cities and empires (see Figure 1). [11]

These specified world regions are somewhat arbitrarily bounded but we have

developed this spatial set of categories based on our knowledge of where large

cities first emerged, and with attention to the issue of large empires.[12]

Figure 1: The ten world regions we are using for comparisons

Measures of relative complexity based

on the territorial sizes of empires

Determining relative

sizes requires real metric (interval-level) estimates, not just periodizations of growth and decline. What we want to know

is the size of the area over which a

central power exercises a degree of control that allows for the appropriation

of important resources (taxes and tribute). The ability to extract

resources falls off with distance from the center in all polities, and

controlling larger and larger territories requires the invention of new

transportation, communications and organizational technologies [what Michael

Mann (1986) has called “techniques of power”]. Military technologies and

bureaucracies are important institutional inventions that make possible the

extraction of resources over great distances, but so are new ideologies and new

technologies of communication (Innis 1950).

Political boundaries between states were not usually as formalized

before the modern era, and so these boundaries were often fuzzy regions of

declining ability to extract resources.

The galactic or mandala model of state structure developed by Stanley Tambiah (1977) to understand political structures in

Southeast Asia is broadly applicable. Thus the territorial size estimates that

have been compiled for Bronze and Iron Age polities contain a rather large

error component and these estimates, like the estimates of the population sizes

of cities, need to be continuously evaluated with consideration to recently

developed historical knowledge about the polities and regions.

Not all maps in political atlases

show the boundaries of territorial control. They may represent linguistic or

religious groups or other distinctions that have little or nothing to do with

state power. And maps may not have good time resolution. Our estimates of the

territorial sizes of polities are mainly derived from the published articles of

Rein Taagepera (1978a, 1978b, 1979, 1997).[13]

Following Taagepera, we use square megameters to indicate the territorial sizes of polities. A

square megameter is a territory that is 1000 by 1000

kilometers in size.

Of

course territorial size is only a rough indicator of the power of a polity

because areas are not equally significant with regard to their ability to

supply resources. A desert empire may be large but weak. But this rough

indicator is quantitatively measureable in different world regions over long

periods of time, so it is valuable for comparative historical research.

Estimating

the territorial sizes of states and empires is based on the use of published

historical atlases and histories. It is very difficult to estimate the sizes

and political boundaries of polities with archaeological evidence alone. So

documentary evidence is the basis of these estimates. For the ancient and

classical worlds these are based primarily on knowledge about who conquered which

city, and whether or not and for how long tribute was paid to the conquering

polity. Knowledge of rebellions is also used to gage instances in which states

get smaller. Only asymmetrical (unequal) exchange signifies a tributary

imperial relationship. Otherwise it is just trade and does not signify an

extractive relationship and a boundary of political control. Sometimes it is

difficult to tell whether or not tribute is asymmetrical or symmetrical

exchange. Chinese dynasties often required formal suzerainty and tribute from

other states but also sent elaborate gifts to their alleged vassals. In some

cases (as with Central Asian steppe confederacies) the balance seemed to have

gone away from China rather than toward it.

Polities not only get larger, but their structures evolve over the

period of our study. Early states expanded into territorial empires, and then

large non-contiguous colonial empires emerged, and then these were replaced by

contiguous modern nation-states. Most of the large ancient and classical

empires involved the conquest of territory that that was contiguous with the

home territory. But once naval power was taken up by tributary states an empire

could conquer and dominate a client state that was far from its home territory,

such as Rome’s control of areas on the south shore of the Mediterranean Sea. If

these distant non-contiguous tribute-payers were small in number and/or size,

not including them in the estimates of the territorial sizes of empires would

not constitute a large error. But, as capitalism moved from the semiperiphery to the core, capitalist nation-states

increasingly adopted the thallassocratic form of

empire that had been pioneered by semiperipheral

capitalist city-states[14]—control

over distant overseas colonies. The modern colonial empires (British, French,

etc.) require estimating the territorial sizes of colonies that are spread

across the seas. Waves of decolonization have eventuated in the contemporary

international system of polities in which the largest are contiguous modern

nation-states such as Russia, the United States, Brazil, etc.. The increasing

institutionalization of the territorial boundaries of states makes it much

easier to determine the territorial sizes of polities than it was in the

ancient and classical worlds in which polity boundaries were often very fuzzy.

Comparing polity sizes across world

regions and PMNs

The

results of our comparisons of relative sizes of polities have important

implications for the huge literature that compares the trajectories of state

formation and economic development in East Asia with that of the West. Most of

the earlier literature compares China with Europe. Our use of world regions

allows us to compare East Asia with Europe, but also to track the political

military network (PMN) that came out of Mesopotamia and Egypt and expanded west

to include the Mediterranean, and eventually the Americas and east to include

South Asia. This is a comparison of the East Asian PMN with the Central PMN.

States and empires sometimes cross the boundaries between our designated world

regions. When this happens we assign the territorial size of the polity to the

region that contains its capitol.

Walter Scheidel’s

(2009) insightful consideration of the similar and different trajectories of

China and the Mediterranean contends that there were two great divergences. The

one that occurred in the 18th and 19th centuries has

received a lot of attention from Ken Pomeranz (2000),

who named it “the great divergence”, but also from Bin Wong (1997) and Andre Gunder Frank (1998).

Scheidel (2009) notes that there was an

earlier great divergence between China and the West. Both the Roman and the Han empires managed to

bring huge territories under a single authority, but after they declined

different things happened in the West and the East. In the East the decline of the Han was

followed, after an interval, by the rise of the Tang empire, which was nearly

as large as the Han had been. In the West, after the fall of Rome another

empire of a similar huge size, uniting the entire Mediterranean littoral, never

rose again. This was the first great

divergence. Scheidel

(2009: 12-13) also compares the percentage of time that the core of each region

has been politically united. He cites Victoria Hui (2008:59) regarding the

percentage of time between 214 BCE and 2000BCE that the Chinese core, defined

as the region controlled by the Qin dynasty at its height in 214 BCE, has been

united (42%). Hui is making the point that China has been less united than most

observers believe, but Scheidel (2008:13) reports

that “the western ecumene that was under Roman rule

at the death of Augustus in 14 CE” has been united for only 18% of the time,

and not at all for the past 16 centuries. Empires did emerge in the West after

the fall of Western Rome, but none of them were able to take over the entire

core region that had been held by Rome. [15]

The first great divergence can be

seen in Figure 5 below. Scheidel contends that

geographical and climate differences do not explain the first divergence. He assumes that empires are easier to erect

when there are fewer barriers to transportation and communication. He asserts

that the core region of China in two river valleys is a more difficult region

to integrate relative to the Mediterranean littoral because mountain ranges

separate the valleys. Indeed central regulation and control may be less needed

in a system in which the network structure was itself less centralized or

linear.[16]

Greater transportation and

communications costs (up to a point) give greater incentives for the non-center

to go along with the center because the center provides access to many

different locales.

The Mediterranean “Middle Sea” allowed many

network nodes to connect directly with many other nodes. Centralized control was

not needed in order to facilitate interaction. In China the Grand Canal project

that linked the valley of the Huang He River with the river valleys of

the south

by water required a centralized authority to build and maintain it while the

Middle Sea did not. Of course there were several other differences that may

have contributed to the first great divergence. Phonetic alphabets had been

adopted in the West, allowing local languages to each be written in their own

way, but making cross-language communication more difficult. The ideographic

characters used in China allowed different languages to use the same symbols,

making it possible for speakers of very different languages to read the same

documents. Scheidel

also mentions the possibility that differences in the nature of the

legitimation of authority may have facilitated centralization in China, but not

the West. The Chinese state used legalism and Confucianism, while the West

experienced competing (and conflicting) transcendent otherworldly religions.

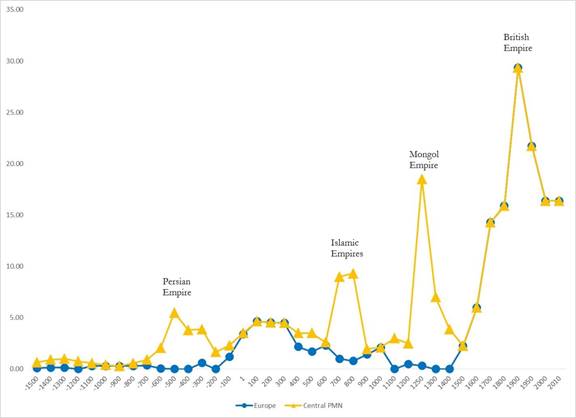

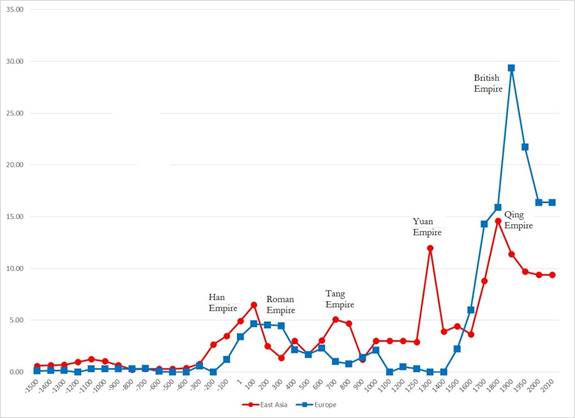

Figure 2: Sizes of largest polities in Europe and in the Central PMN

We will

be comparing East Asia with both Europe and the Central PMN below but the first

question is to compare Europe and the Central PMN to one another. So Europe and

the Central PMN overlap over most of the period we are studying, but the

Central PMN is larger. When Morris and Scheidel

compared East Asia (mainly China) with “the West” they were usually thinking

about what we here call the Central PMN. But much of the literature on

East/West comparisons is about Europe (the “little West”) and China. So here we

do both. Figure 2 shows the differences that it makes when we look at the

largest polities in the expanding Central PMN vs. in Europe as a constant world

region. These two series are rather highly correlated (partial Pearson’s r =

.78, see Table 2 below) but they diverge during certain periods. The big

divergences are due to the rises of the Persian, Islamic and Mongol Empires,

all of which had capitals outside of Europe but within the Central PMN. We

included Central Asia in the Central PMN after 30 CE (see Footnote 11 above)

because of the Kushan Empire, but Central Asian steppe

confederacies such as the Xiongnu were obviously

important players in the East Asian PMN since

212 BCE. The Eastern and Western PMNs overlapped to some extent in Central

Asia. But, with the exception of the short-lived Mongol Empire, direct

connections did not exist until the 19th century CE. The issue here is to what extent could

indirect connections be strong enough to constitute systemness.

This issue will be investigated in a workshop on the spatial bounding of

world-systems (see Chase-Dunn, Wilkinson, Anderson, Inoue and Denemark 2015).

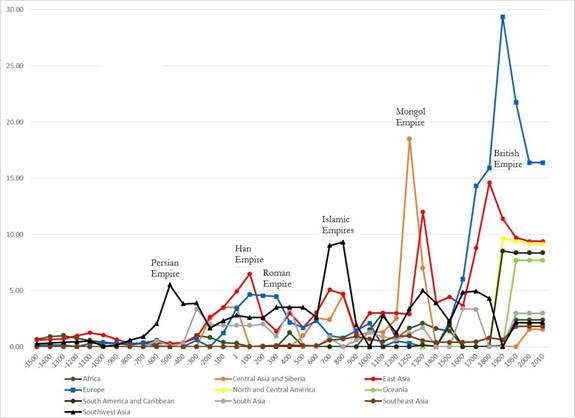

Figure

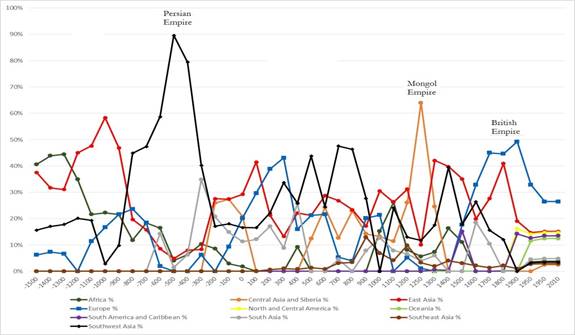

3: Sizes of largest polities in each of 10 world regions (square megameters): 1500 BCE- 2010CE

Figure 3 shows the sizes of the territories of the largest polities in each of our ten world regions from 1500 BCE until 2010 CE. There is the long-term trend toward larger polities in evidence in all the world regions, but also ample evidence of the patterns of rise and fall in each.

This graph is rather different from the one

produced by studying city sizes in all the regions (Chase-Dunn, Inoue, A. Alvarez, R. Alvarez, Anderson and

Neal 2015: Figure 3).

The

scale change for cities was far larger than the scale change for polities over

the last 3500 years. In 1500 BCE the largest city had only 75,000 people but by

2010 CE Tokyo had nearly 37 million people – a ratio increase of more than 492.

When we use the built-up area of cities the same scale change ratio for Thebes

and Tokyo is much greater (1696, see Table 1). But for polities the territorial size scale

change goes from .65 square megameters for the Theban

state to 17.1 square megameters for the Russian

Federation in 2010 CE. This is a scale

change ratio of only 26. The largest single formal empire ever was the British

Empire in 1900 CE with 29 square megameters of

territory, a ratio scale change of just 45 compared with Thebes in 1500 BCE. So

cities have grown much more than polities have over the last three and one half

millennia.

|

Scale Changes |

Largest City

(Population) |

Largest City (Built-up area) |

Largest Polity (Square Megameters) |

|

1500 BCE |

Thebes 75,000 |

8 km2 |

Thebes .65 |

|

2010 CE |

Tokyo 36,932,800 |

13,572 km2 |

Russian Federation

17.1 |

|

Scale change ratio |

492 |

1696 |

26 |

Table 1: Urban and Polity Territory Scale Changes, 1500 BCE to 2010 CE

The

city populations took off exponentially in the 19th century but the

polity sizes came down or leveled out because of collapse of the territorial

and colonial empires. Of course, as we have mentioned above, formal political

control over territory is not the only way that imperialism can be organized.

The extensive literature on neo-colonialism, hegemony and new forms of globalized

empire is germane here. But the overall trend toward larger formal states is

evident in the period since 1500 CE. It is hard to compare world regions when

we put them all in the same graph, but the strange trajectory of Central Asia

stands out in Figure 3, with the Mongol Empire showing itself as having been

the 2nd largest territorial empire in world history.

Figure

4: Percentage of each region held by its largest polity of the sum of the

largest polities in all ten regions

This

is what happens when we pit all the world regions against one another. The

percentages in Figure 4 are based on the denominator obtained by adding all the

territorial sizes in each of the regions together. We should note that our data

set is still not complete (see count of missing cases in Appendix), but the

main patterns displayed in Figure 4 will probably hold up when more estimates

are added. This a very complex set of patterns and it is hard to see what is

going on when we have all ten world regions. But some things jump out. The most obvious is

the 500 BCE overwhelming predominance of the Persian Empire in a period in

which the other regions had only small states.

We should remind the reader that we place an empire in its region

depending on where its capital is located.

So the Persians conquered Egypt, but Southwest Asia gets the points. Another interesting feature of Figure 4 is

what percentaging does to the relative standings of

the Mongol and British Empires. From the point of view of relative size, the

Mongols had a greater percentage than the British did, though neither come

close to the relative predominance of the earlier Persian Empire. Persia was

the proverbial 800 pound gorilla of the Central PMN.

Figure 5: Sizes of largest

polities in Europe and East Asia (square megameters):

1500 BCE- 2010CE

Figure

5 has the same numbers as Figure 3 above but without including the other seven

world regions. This figure shows the

sizes of the largest states and empires in Europe and East Asia since 1500 BCE.

Again both regions show the overall long-term trend toward greater polity sizes

and also the sequences of shorter-term rises and falls. Of interest here are

the two great divergences discussed above and the issue of synchrony vs.

see-sawing. We also want to compare the East Asian trajectory with that of the

Central PMN as well as with Europe. When we look at Europe’s trajectory vis a

vis East Asia in Figure 5 we can see that the rise of the Han Empire in China

began earlier than the rise of large Macedonian and Roman empires in Europe and

the decline began earlier in East Asia than it did in Europe. This has

implications for Scheidel’s notion of the first

divergence because the waves of empire formation were not entirely synchronous.

China did it first, followed not long after by Europe. The European peak then

last rather longer that the Chinese peak did. This was what many have observed

as the unusually long tenure of the Roman Empire. Then Europe went into a long

slump while Tang China recovered. With regard to the second great divergence,

the territorial size trajectories imply something different from Gunder Frank’s notion of stable Chinese centrality and late

and unstable European predominance. The

new rise of Europe begins earlier than Frank claims (in the 15th

century, not in the 18th) and Qing China is also getting larger but

ends up only half as large as the British Empire.

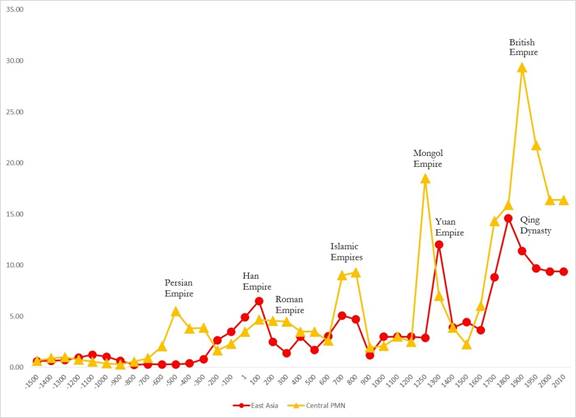

Figure 6: Sizes of largest

polities in East Asia and the Central PMN (square megameters):

1500 BCE- 2010CE

Figure

6 compares the largest polities in East Asia with those in the expanding

Central PMN. Recall that East Asia becomes part of the Central PMN in the

middle of the 19th Century CE but we can still compare the part with the whole

after that. Things look a bit different than when we compared with only the

“little West.” The Persian Empire, with its capital in Southwest Asia rises and

falls before the emergence of the Han. And the Islamic Empires are larger and

synchronous with the Tang. And since we have included Central Asia in the

Central PMN, the Mongol Empire appears just ahead of the very large Yuan Empire

which was, of course, founded by the Mongols. After 1500 CE the story is the

same as in Figure 6 because European powers, including the British Empire and

Russia, were the largest territorial polities. So Figure 6 seems to display

much more East/ “West” similarity than Figure 5 does.

The partial Pearson’s r correlation

coefficients among East Asia, Europe and the Central PMN are shown in Table 2.

|

Region or PMN |

Europe |

Central PMN |

East Asia |

|

Europe |

1 |

.78 sig = .000 |

.57 sig =.000 |

|

Central PMN |

.78 sig =.000 |

1 |

.51 sig =.001 |

|

East Asian Region and PMN |

.57 sig = .000 |

.51 sig = .001 |

1 |

Table 2: Pearson’s r

partial correlation coefficients (controlling for Year) for territorial

sizes of the largest polities in East Asia, Europe and the Central PMN from

1500 BCE to 2010 CE (n= 39)

Table 2 contains the correlation coefficients

produced by partial correlations in which year is held constant to control for

the long-term upward trend in the territorial sizes of polities. Unsurprisingly

given that Europe is an important part of the Central PMN, there is a .78

positive correlation across the 3500 year period studied. But somewhat more surprising

are the positive and statistically significant partial correlations between

Europe and East Asia and between the Central PMN and East Asia. Contrary to our examination of Figures 5 and

6 above, the partial correlation between the Central PMN and East Asia is

somewhat smaller than the partial correlation between Europe and East Asia.

Urban and Polity Conclusions

Our study of the largest cities in world

regions suggested problems with Andre Gunder Frank’s

(1998) characterization of the relationship between Europe and China before and

during the rise of European hegemony and the results of this study of largest

polities find the same things. Frank’s contention that Europe was primarily a

peripheral region relative to the core regions of the Afro-eurasian

world-system is supported by the city and polity data, with some

qualifications. Europe was for millennia

a periphery of the large cities and powerful empires of ancient Southwest Asia

and North Africa. The Greek and Roman cores were instances of semiperipheral marcher states that conquered important

parts of the older Southwest Asian/North African core. After the decline of the

Western Roman Empire, the core shifted back toward the East and Europe was once

again importantly peripheral. We find

partial support for Walter Schiedel’s idea of the

first great divergence between East and West after the decline of the Western

Roman Empire. Scheidel’s observation that the

Mediterranean was never again united as it had been under Rome is correct, but

the rise the Islamic Empires, part of the Central PMN was substantially

synchronous with the rise of the Tang dynasty in China. We also find more synchrony than the

see-sawing described by Morris, which would produce negative rather than

positive correlation coefficients.

Our

urban and polity synchrony findings support the idea proposed in Frank and

Gills (1994) that there was an integrated Afro-eurasian

world-system much earlier than most historians and civilizationists

suppose. But we cannot yet be certain that interaction networks were the

important causes of the synchrony and, if they were, we do not know which kind

of interactions were most important.

Counter

to Frank’s contention, however, the rise of European hegemony was not a sudden conjunctural event that was due solely to a developmental

crisis in China. The city population data indicate that an important renewed

core formation process had been emerging within Europe since at least the 14th

century. This was partly a consequence

of European extraction of resources from its own expanded periphery that is

seen in the expansion of the European colonial empires. But it was also likely

due to the unusually virulent form of capitalist accumulation within Europe,

and the effects of this on the nature and actions of states. The development of

European capitalism began among the city-states of Italy. It spread to the

European interstate system, eventually resulting in the first capitalist

nation-state (the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century) as well as the

rise of the hegemony of the United Kingdom of Great Britain in the nineteenth

century. This process of regional core formation and its associated emphasis on

capitalist commodity production further spread and institutionalized the logic

of capitalist accumulation by defeating the efforts of territorial empires

(Hapsburgs, Napoleonic France) to return the expanding European core to a more

tributary mode of accumulation.

Acknowledging

some of the uniquenesses of the emerging European

hegemony does not require us to ignore the important continuities that also

existed as well as the consequential ways in which European developments were

linked with processes going on in the rest of the Afroeurasian

world-system.

The

more recent emergence of East Asian cities as again the very largest cities on

Earth occurred in a context that was structurally and developmentally distinct

from the militarily multi-core system that still existed in 1800 CE. Now there

is only one global core because all the core states are directly interacting

with one another. While the military multi-core system prior to the nineteenth

century was undoubtedly systemically integrated to an important extent by trade

and information flows, it was not as interdependent as the global world-system became

in the nineteenth century.

A new East Asian

hegemony is by no means a certainty, as both the United States and German-led

Europe will be strong contenders in the coming period of multi-polar hegemonic

rivalry (Bornschier and Chase-Dunn 1999; Chase-Dunn,

Kwon, Lawrence and Inoue 2011). The transition from territorial empires to

colonial empires and now to a global polity composed of formally sovereign

nation states has not ended the long evolutionary trend toward larger and

larger polities. This trend can continue to be seen in the trajectory of the increasing

size of the capitalist states that have assumed the role of leadership and

hegemony in the modern world-system, first the tiny Dutch Republic of the 17th

century, then the British Empire and now the continental-sized United States.

The forms of power have evolved, but uneven development and the processes of

rise and fall continue.

References

Abu-Lughod, Janet Lippman 1989. Before

European Hegemony The World System A.D. 1250-1350

New

York: Oxford University Press.

Amin,

Samir 1980. Class and Nation, Historically and in the Current Crisis. New York:

Monthly

Review Press.

Anderson, E. N. and Christopher Chase-Dunn “The

Rise and Fall of Great Powers” in

Christopher

Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) 2005.

The Historical

Evolution of World-Systems. London: Palgrave.

Arrighi,

Giovanni 1994. The

Long Twentieth Century. London: Verso.

______________

2008 Adam Smith in Beijing. London:

Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Takeshi Hamashita, and Mark Selden

2003 The Resurgence of East Asia :

500, 150 and 50 Year

Perspectives. London: Routledge

Barfield, Thomas J. 1989 The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China. Cambridge, MA.:

Blackwell

Beaujard, Philippe. 2005 “The Indian Ocean in Eurasian and African

World-Systems Before

the

Sixteenth Century” Journal of World History 16,4:411-465.

_______________ 2009 Les mondes de l’océan

Indien Tome I: De la formation de l’État

au

premier système-monde

Afro-Eurasien (4e millénaire

av. J.-C. – 6e siècle apr. J.-C.).

Paris: Armand Colin.

_______________2010. “From

Three possible Iron-Age World-Systems to a Single Afro-

Eurasian

World-System.” Journal of World History

21:1(March):1-43.

_______________ 2112 Les mondes

de l’océan Indien Tome II: L’océan Indien, au coeur des

globalisations

de l’ancien Monde du 7e au 15e siècle. Paris: Armand

Colin

Beckwith,

I. Christopher. 1991. "The Impact of the Horse and Silk Trade on the

Economies

of T'ang China and

the Uighur Empire." Journal of the

Economic and Social History of the

Orient 34:2:183-198.

Bentley, Jerry H.

1993. Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in

Pre-

Modern Times. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Blanton, Richard E. , Stephen A. Kowalewski, and Gary Feinman. 1992.

"The Mesoamerican World-System." Review

15:3(Summer):418-426.

Bornschier, Volker and Christopher Chase-Dunn

(eds.) 1999 The Future of Global

Conflict London: Sage

Braudel, Fernand 1972 The

Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II.

New

York: Harper and Row, 2 vol.

_____________. 1984. The Perspective of the World, Volume 3

of Civilization and Capitalism.

Berkeley: University of California Press

Chandler, David 1996 A History of Cambodia. Boulder, CO:

Westview Press.

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1988. "Comparing world-systems:

Toward a theory of semiperipheral

development," Comparative

Civilizations Review, 19:29-66, Fall.

Chase-Dunn, C and Thomas D. Hall

1993"Comparing World-Systems:

Concepts and

Working

Hypotheses" Social Forces

71:4(June):851-886.

____________________________1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems

Boulder,

CO.: Westview Press.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Thomas D. Hall. 2011“East and West in world-systems

evolution” Pp. 97-119 in Patrick Manning and Barry K. Gills (eds.) Andre Gunder Frank and Global Development, London: Routledge.

Chase-Dunn, C. , Thomas D. Hall and Peter Turchin. 2007 “World-Systems in the Biogeosphere: Urbanization, State Formation, and Climate Change Since the Iron Age.” Pp.132-148 in The World System and the Earth System: Global Socioenvironmental Change and Sustainability Since the Neolithic, edited by Alf Hornborg and Carole L.

Crumley. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Books.

Chase-Dunn,

Chris, Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence and Hiroko Inoue 2011 “Last of the

hegemons: U.S. decline and global

governance” International Review of Modern

Sociology 37,1: 1-29 (Spring).

Chase-Dunn, C. , Susan Manning and Thomas D.

Hall 2000 “Rise and fall: East-West

synchronicity

and Indic exceptionalism reexamined,” Social

Science History. 24,4:727-

754.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Andrew K. Jorgenson 2003 “Regions and Interaction Networks: an

institutional

materialist perspective,” International Journal of Comparative Sociology

44,1:433-450.

Chase-Dunn,

C. Eugene N. Anderson, Hiroko Inoue,

Alexis Álvarez, Lulin Bao,

Rebecca Álvarez,

Alina Khan and Christian Jaworski 2013 “Semiperipheral Capitalist

City-States and the Commodification of Wealth,

Land, and Labor Since the Bronze Age”

IROWS Working Paper #79 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows79/irows79.htm

Chase-Dunn, C.

and Dmytro Khutkyy 2015 “The evolution of

geopolitics and imperialism

in interpolity

systems” IROWS Working Paper # 93

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows93/irows93.htm

Chase-Dunn,

C and Bruce Lerro 2014 Social Change: Globalization from the Stone Age to the

Present. Boulder, CO: Paradigm

Chase-Dunn, C. Hiroko Inoue, Alexis Alvarez, Rebecca Alvarez, E.

N. Anderson and Teresa

Neal 2015 “Urban uneven development: largest

cities since the Late Bronze Age”

Presented

at the annual conference of the American Sociological Association, Chicago,

August 24, 2015. IROWS Working Paper # 98

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows98/irows98.htm

Data appendix for this paper is at https://irows.ucr.edu/cd/appendices/worregs/worregsapp.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. David Wilkinson, E.N. Anderson,

Hiroko Inoue and Robert Denemark

2015

“Time-mapping globalization since the Bronze Age” IROWS Working Paper #

100 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows100/irows100.htm

Chew,

Sing C. 2001 World ecological degradation : accumulation, urbanization, and

deforestation, 3000

B.C.-A.D. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press

___________ 2007 The Recurring Dark Ages : ecological stress,

climate changes, and system

transformation Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press

___________ 2014 “The Southeast Asian connection in

the first Eurasian world economy,

200

BC- AD 500” Journal of

Globalization Studies,

Vol. 5 No. 1: 82–109

Coe, Michael D. 2003 Angkor and the Khmer Civilization. New

York: Thames and Hudson.

Ekholm, Kasja

and Jonathan Friedman 1982 “’Capital’ imperialism and exploitation in the

ancient world-systems” Review 6:1 (summer): 87-110.

Elvin,

Mark. 1973. The Pattern of the Chinese

Past. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Fitzpatrick,

John. 1992. "The Middle Kingdom, the Middle Sea, and the Geographical

Pivot

of History." Review XV, 3 (Summer): 477-521

Flynn, Dennis O. 1996 World Silver and Monetary History in the 16th and 17th

Centuries.

Brookfield,

VT: Variorum.

Frank, Andre Gunder

1998 Reorient: Global Economy in the

Asian Age. Berkeley: University of

California

Press.

_________________ 2014 Reorienting the 19th Century: Global Economy in the

Continuing Asian

Age.

Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Frank, Andre Gunder

and Barry Gills 1994 The World System:

500 or 5000 Years? London:

Routledge.

GeaCron World History Atlas & Timelines since 3000 BC . Luis Músquiz

http://geacron.com

Hall, Thomas D., Christopher Chase-Dunn and Richard Niemeyer. 2009 “The Roles of Central Asian Middlemen and Marcher States in Afro-Eurasian World-System Synchrony.” Pp. 69-82 in The Rise of Asia and the Transformation of the World-System,

Political Economy of the World-System Annuals. Vol XXX, edited by Ganesh K. Trinchur. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Press.

Honeychurch, William 2013 “The Nomad as State Builder: Historical Theory

and Material

Evidence from Mongolia” Journal of World Prehistory 26:283–321

Hui, Victoria Tin-Bor 2005 War and state Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press._________________ 2008 “How China was ruled” China Futures, Spring, 53-65Innis, Harold 1972 [1950] Empire and Communications. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Inoue, Hiroko 2014

“Settlement dynamics and empire dynamics: a comparative and

evolutionary world-systems perspective” Paper

presented at the annual meeting of

the American Sociological Association, San Francisco,

August 17.

Inoue,

Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez,

Kirk Lawrence, Anthony Roberts, Eugene N Anderson and

Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2012 “Polity scale shifts in world-systems since the Bronze Age:

A comparative inventory of upsweeps and

collapses” International Journal of

Comparative Sociology

http://cos.sagepub.com/content/53/3/210.full.pdf+html

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Eugene N. Anderson, Andrew Owen, Rebecca Álvarez, Kirk

Lawrence and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2015 “Urban scale shifts since the Bronze

Age: upsweeps, collapses and semiperipheral development” Social Science History Volume 39 number 2, Summer

Inoue, Hiroko Alexis Álvarez, E.N. Anderson, Kirk

Lawrence, Teresa Neal, Dmytro

Khutkyy, Sandor Nagy and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2013

“Comparing World-

Systems:

Empire Upsweeps and Non-core marcher states Since the Bronze Age”

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows56/irows56.htm

Lattimore, Owen 1940 Inner Asian Frontiers of China. New York: American Geographical

Society.

Lenski,

Gerhard 2005 Ecological-Evolutionary Theory. Boulder, CO: Paradigm

Publishers

Lieberman, Victor. 2003. Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830. Vol.

1:

Integration on the Mainland.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

______________ 2009. Strange

Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global

Context, c. 800-1830. Vol 2:

Mainland

Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands. Cambridge:

Cambridge

University Press.

Liu,

Xinru and Lynda Norene

Shaffer. 2007. Connections across

Eurasia: Transportation,

Communication, and Cultural Exchange on the Silk Roads. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Liverani, Mario 2013 The Ancient Near East. New

York: Routledge.

Mann,

Michael. 1986. The Sources of Social Power, Volume 1:

A history of power from the beginning

to A.D. 1760.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

McNeill,

John R. and William H. McNeill 2003 The Human Web. New York: Norton.

Modelski, George 2003 World

Cities: –3000 to 2000. Washington, DC:

Faros 2000

______________ Tessaleno

Devezas and William R. Thompson (eds.) 2008 Globalization

as

Evolutionary

Process: Modeling Global Change.

London: Routledge

Morris, Ian 2010 Why the West Rules—For Now.

New York: Farrer, Straus and

Giroux

______ 2013 The

Measure of Civilization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

_______ and Walter Scheidel

(eds.) The Dynamics of Ancient Empires:

State Power from Assyria to

Byzantium. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Neal, Teresa 2013 “The Sasanian empire and world-systems Research” Working Paper,

Department of History, University of

California-Irvine

Pomeranz, Kenneth 2000 The Great Divergence: Europe,

China and the Making of the Modern World

Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sanders,

William T., Jeffrey R. Parsons, and Robert S. Santley

1979 The Basin of Mexico:

Ecological Processes in the Evolution of a Civilization. New York: Academic

Press,

Scheidel, Walter

2009 “From the “great convergence” to the “first great divergence”:

Roman and Qin-Han state formation”

Pp. 11-23 in Walter Scheidel (ed.) Rome and

China: Comparative Perspectives on

Ancient World Empires.

New York: Oxford University

Press.

SESHAT :

The Global History Data Bank http://seshatdatabank.info/

____________

and Sitta Von Reden (eds.) The Ancient Economy. New York:

Routledge.

Sherratt, Andrew G. 1993a. "What Would a Bronze-Age World

System Look Like? Relations

Between Temperate

Europe and the Mediterranean in Later Prehistory."

Journal

of European Archaeology 1:2:1-57.

_____. 1993b.

"Core, Periphery and Margin:

Perspectives on the Bronze Age."

Pp. 335-345 in

Development

and Decline in the Mediterranean Bronze Age, edited by C. Mathers and S. Stoddart.

Sheffield:

Sheffield Academic Press.

_____. 1993c. "Who are You Calling

Peripheral? Dependence and Independence

in European

Prehistory." Pp.

245-255 in Trade and Exchange in

Prehistoric Europe, edited by C. Scarre and F.

Healy.

Oxford: Oxbow (Prehistoric

Society Monograph).

_____. 1993d. "The Growth of the Mediterranean

Economy in the Early First Millennium BC."

World Archaeology 24:3:361-78.

Schwartzberg, Joseph E. 1992 A Historical Atlas of South Asia New

York: Oxford

University Press. eMap :

Atlas : Document : English : 2nd impression. Chicago, Ill. :

Digital South Asia

Library, Center for Research Libraries

http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/schwartzberg/

Taagepera, Rein 1978a

"Size and duration of empires: systematics of size" Social Science

Research 7:108-27.

______

1978b "Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600

B.C."

Social Science Research, 7

:180-96.

______1979

"Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 600 B.C. to 600

A.D."

Social Science History

3,3-4:115-38.

_______1997

“Expansion and contraction patterns of large polities: context for Russia.”

International Studies Quarterly 41,3:475-504.

Tambiah, Stanley J. 1977 "The galactic

polity: the structure of traditional

kingdoms in

Southeast

Asia", Anthropology and the Climate of Opinion, Annals of the

New York

Academy of Sciences 293: 69–97

Teggart,

Frederick J. 1939 Rome and China: A Study

of Correlations in Historical Events Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Thompson,

William R and Kentaro Sakuwa

2013 “Was Wealth Really Determined in 8000 BCE,

1000 BCE, 0 CE, or Even 1500 CE? Another, Simpler

Look” Cliodynamics 4,1: 2-29

http://escholarship.org/uc/item/64q20336

Tilly,

Charles. 1990. Coercion,

Capital, and European States, AD 990-1990. Cambridge, MA:

Basil Blackwell

Turchin, Peter 2011 “Strange Parallels: Patterns in

Eurasian Social Evolution” Journal

of World Systems Research 17(2):538-552

Turchin, Peter, Jonathan M. Adams, and Thomas D. 2006.

“East-West Orientation of

Historical Empires and Modern States.” Journal of World-Systems Research. 12:2(December):218-229.

___________

and Sergey Gavrilets 2009 “The evolution of complex

hierarchical societies”

Social Evolution & History,

Vol. 8 No. 2, September: 167–198.

______________Thomas E. Currie, Edward A.L. Turner and Sergey Gavrilets 2013

“War, space, and the evolution of Old World complex societies”

PNAS October

vol. 110 no. 41: 16384–16389

Appendix: http://www.pnas.org/content/suppl/2013/09/20/1308825110.DCSupplemental/sapp.pdf

Turchin, Peter, Rob Brennan,

Thomas E. Currie, Kevin C. Feeney, Pieter François, Daniel

Hoyer, J. G. Manning, Arkadiusz Marciniak, Daniel

Mullins, Alessio Palmisano,

Peter Peregrine, Edward A. L. Turner, Harvey

Whitehouse. 2015.

“Seshat: The Global History

Databank” Cliodynamics 6: 77–107

Wallerstein, Immanuel 2011 [1974] The Modern World-System, Volume 1.

Berkeley: University

of

California Press.

Wilkinson, David 1987 "Central

Civilization." Comparative

Civilizations Review 17:31-59.

______________1991 "Core, peripheries and

civilizations." Pp. 113-166 in Christopher

Chase-Dunn

and Thomas D. Hall (eds.) Core/Periphery

Relations in Precapitalist Worlds,

Boulder,

CO.: Westview.

_______________1992a "Decline phases in

civilizations, regions and oikumenes." A paper

presented

at the annual meetings of the International Studies Association, Atlanta,

GA. April 1-4.

______________ 1992b "Cities,

civilizations and oikumenes:I." Comparative Civilizations

Review 27:51-87 (Fall).

_______________ 1993 “Cities, civilizations and

oikumenes:II”

Comparative Civilizations

Review 28: 41-72.

_______________2004 The Power Configuration Sequence of the

Central World System, 1500-700 BC

Journal of World-Systems Research Vol. 10, 3.

Wilkinson, Toby C., Susan Sherratt and John

Bennet 2011 Interweaving Worlds: Systemic

Interactions in

Eurasia, 7th to

1st Millennia BC. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Wohlforth, William

C., Richard Little, Stuart J. Kaufman, David Kang, Charles A Jones,

Victoria Tin-Bor Hui, Arther Eckstein, Daniel Deudney and William L Brenner 2007

“Testing balance of

power theory in world history” European

Journal of

International Relations 13,2:

155-185.

Wolf , Eric

1997 Europe and the People Without

History, Berkeley: University of

California

Press.

Wong,

R. Bin 1997 China Transformed: Historical

Change and the Limits of European Experience.

Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Endnotes