Settlement Networks and

Sociocultural Evolution

Elizabeth Bogumil

and Christopher Chase-Dunn

Sociology, University of California-Riverside

Edward

Elgar Handbook on Cities and Networks

Editors: Zachary Neal, Michigan State University and Celine Rozenblat, University of Lausanne

v. 8/27/18 11342 words This is IROWS Working Paper #127 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows127/irows127.htm

Abstract: Settlement

networks provide a fundamental window on human social structures and their

connections with the biosphere. We present an overview of the roles that human

settlement interaction networks have played in the sociocultural evolution of

human societies since the Paleolithic Era using the comparative world-systems

perspective. We also summarize research

on the location and timing of changes in the scale of settlements and polities

since the Bronze Age, the emergence of the contemporary global city system and

discuss possible futures for the city of humans.

Keywords: world-system,

sociocultural evolution, settlement, interaction networks, cities, comparative

Anthropologists and historical

comparative social scientists have seen value in understanding not only how

different locations and cultures are distinct but also where and when sociocultural

complexity and hierarchy have emerged over the past twelve thousand years. Knowledge

of where and when the sizes of human settlements[1] have

changed over time is useful for testing aspects of general models of

sociocultural evolution.[2] This

chapter examines the roles of settlement networks in sociocultural evolution using

the comparative world-systems perspective. The first section focuses on settlements,

and the interaction networks built amongst them, before the emergence of states.

The second section describes how interaction networks were involved in the rise

and fall of large settlements and polities and in the emergence of settlements

that were larger than any that had existed before. The third section discusses

the early emergence of cities and states in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus River

Valley, the Yellow River Valley, Mesoamerica and the Andes. And the expansion

of empires and their building of empire cities. The fourth section considers

the emergence and spread of semiperipheral capitalist

city-states and their roles in the construction of commodity trade networks and

the spread of commercializations networks in

world-systems in which state power and tributary accumulation remained the main

instruments of reproduction. And then we consider how the emergence of the

Europe-centered capitalist world-system drove and was driven by the

establishment of core world cities and dependent colonial cities. Finally, we conclude by providing an overview

of the implications of research on the evolution of settlement systems for

understanding the contemporary global system of city-regions and possible futures

for the world city system.

Anthropological and World Historical

Frameworks of Comparison

The emergence of sedentism, the

growth of settlements and interaction networks among settlements and polities[3]

are fundamental processes of social change that required the invention of

institutions that could facilitate cooperation and enable polities to

effectively compete with one another for resources, including territory. The

study of settlement size distributions – the relative sizes of interacting

settlements – within polities and in networks of independent interacting

polities -- provides another important window for viewing and comprehending the

emergence and growth of human organizational complexity and hierarchy.

An anthropological and world

historical framework of comparison allows us to study the evolution of

small-scale (prestate) polities as well as the

emergence and growth of cities and the rise of more hierarchical of settlement-size

distributions. Ethnographers and archaeologists

have studied small-scale nomadic polities of foragers (hunter-gatherers). All

humans lived in small-scale nomadic polities until about 12.000 years ago.

Nomadic foragers lived in temporary camps, but they tended to follow yearly

migration circuits that brought them back to the same seasonal locations, and

so they too had “settlement systems” in the sense that they utilized

geographical space in a patterned way. About 11,000 years ago nomadic foragers in

the Levant (present day Lebanon) began staying longer in winter hamlets. This was the beginning of sedentism. Termed the

“Natufian culture” by archaeologist, these first sedentary people gathered

natural stands of grain that grew in the rain-watered valleys of the Levant and

stored this food so that they could remain in one location through the winter.

These were the first villagers on earth. They were not horticulturalists. They

were sedentary hunter-gatherers, and polities of this kind continued to exist

in certain locations, such as California, until they were colonized by the

expanding modern world-system in the 18th and 19th

centuries of our era. An anthropological

framework of comparison allows us to analyze the settlements systems of nomads

and the emergence of sedentism and the roles that nomads and small-scale polities

and interaction networks have played in the emergence of larger settlement

systems based on horticulture and agriculture. But in order to

comprehend the long-term processes of the development of complexity and

hierarchy we need to combine the study of small-scale systems with a world

historical framework that examines regional systems in which cities

(settlements with at least 50,000 residents) emerged. This occurred in

Mesopotamia and Egypt in the early Bronze Age and these civilizations also invented

writing, so now we have both archaeological and documentary evidence for

studying them.

The Comparative Evolutionary World-Systems

Perspective

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) reconfigured

the world-system perspective that had emerged to study the modern global system

(Hall et al. 2013; Shannon 1992) to compare

spatially small world-systems with medium-sized regional systems and the

now-global world-system of today. They defined world-systems as systemic interaction

networks that link settlements and polities in reciprocal interaction webs

(networks) that condition the reproduction and change of local social

structures.[4] The word “world” here refers to the world of

real interactions (trade, warfare, communications, intermarriage) that

reproduce the social structures and institutions of human groups. In this sense

“worlds” were small when transportation and communication technologies imposed

a tyranny of distance that constrained the consequences of interaction to

extend relatively short distances. These were the small social worlds in which

people lived (see also Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998 and Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2017).

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) noted that

different kinds of systemic interaction often have different spatial scales in

small and medium-sized world-systems. Bulk goods (food) networks were usually

smaller than political/military networks in which independent polities were

making war and security alliances with one another. And, these

political/military networks were smaller than prestige goods trade networks in

which goods that were very valuable relative to their weight were traded in

down-the-line[5] exchange networks or

carried by long-distance traders. The

spatial bounding of world-systems must choose a focal locale and then use the

principal of “fall-off” to determine the distances from that point to the outer

edge of the interaction system (Renfrew 1975, 1977). This is usually at most

two or three indirect (non-contiguous) links. The important point here is that

the networks in which individual settlements are linked with other settlements

typically cross the borders between independent polities (

and so they are “international.”)

Once one has

spatially bounded the interaction networks starting from a focal settlement,

then the issue of core/periphery relations can be examined. The modern core/periphery hierarchy is often

discussed in terms of the Global North and the Global South. World-systemists see the Global South as being composed of small,

poor and relatively powerless peripheral countries in Africa, Asia and Latin

America and larger semiperipheral countries (i.e. Mexico,

Brazil, China, Indonesia, India, Russia), or smaller countries at middle levels

of economic development (i.e. Taiwan, South Korea, Israel, South Africa) that

are in the modern semiperiphery. The core is composed

of most of the national societies in Europe and North America, but also Japan

and Australia. But core/periphery relations may also be studied in earlier

world-systems.[6] Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997)

distinguish between “core/periphery differentiation,” which exists when

polities with different degrees of population density[7]

systemically interact with one another, and “core/periphery hierarchy” which

exists when some polities exploit and dominate other polities. Chase-Dunn and

Hall (1997: Chapter 5) also propose that the phenomenon of “semiperipheral

develop” is an important cause of sociocultural evolution in which polities in semiperipheral positions often are the agents of increases

in the scale and complexity of world-systems.

Human settlements

before the rise of states

As we have said

above, the anthropological framework allows us to study the “settlement

systems” of nomads. Nomads do not wander aimless across the face of the

Earth. They move to most easily obtainable

and desireable food, water and other necessities.

They harvest nature, but nature is seasonal and the

harvesting depletes some of the resources that are being taken. The hunting of

big game depletes the local supply and so it is easier to move the camp than to

travel long distances to hunt. Camps are the settlements of nomadic peoples.

And seasonal migration routes are their patterned settlement systems. Camps and migration circuits are the

patterned ways in which nomads utilize space in socially constructed ways (Dodgshon 1987). Archaeologists

have discovered that seasonal migration circuits became smaller as the

population density of North American nomadic foragers rose (Fagan 1991; Nassany and Sassaman 1995) in the

transition from Paleoindian big game hunters to Archaic hunters who were still nomads

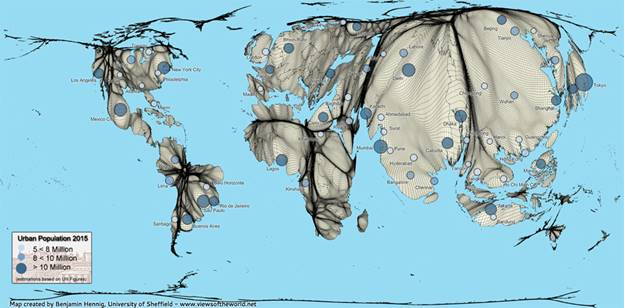

but were hunting smaller types of game (see Figure 1). The Archaic nomadic bands developed spear

point styles that were distinctive from those of their neighbors, whereas Paleo

spear points were much more similar across wide regions of North America.

Nassaney and Sassaman (1995) suggest that these regional

tool kit distinctions mean that the Archaic bands were forming distinct local

and regional cultural identities.

Figure 1: Paleo and Archaic

migration circuits

The shorter

migration circuits were a step on the way to sedentism in which nomadic bands

move down the food chain from hunting large game to relying on smaller game

(which depletes more slowly) and on more vegetable foraging. Population density

(the number of people per area of land) went up and resource use became more

diversified. Both nomadic and sedentary foragers are known to have used fire to

increase the growth of food-producing plants and grazing areas attractive to

game. This kind of activity has been called “protoagriculture”

(Bean and Lawton 1976).

The First Villagers

It is

commonly believed that all hunter-gatherers were nomadic and that sedentism

emerged with horticulture during the “Neolithic revolution.” But this is wrong.

Sedentism emerged before horticulture and sedentary foraging societies survived

into recent centuries in certain ecologically abundant locations such as

California and the Pacific Northwest. Some hunter-gatherers in prime

environments figured out how to exploit less vulnerable natural resources such

as seeds, tubers, small game, and fish. They were able to live much of the year

in semi-permanent winter villages without depleting the environment. These

Mesolithic diversified foragers moved to other locations during the summer for

seasonal hunting or gathering. Some of

the population of the winter villages moved to seasonal camps during the spring

and summer. Thus, the emergence of sedentism that began with the transition to

smaller seasonal circuits continued in small steps until the winter village

became the permanent home of most of the population. The transition from

nomadism to sedentism was a matter of seasonal camps becoming occupied for

longer and longer periods of time, and with some of the population remaining,

while others went off to other locations during special seasons. The earliest

sedentary societies were of diversified foragers in locations in which nature

was bountiful enough to allow hunter-gatherers to feed themselves all year without

migrating. These early villagers continued to interact with still-nomadic

peoples in both trade and warfare. This was the first instance of

core-periphery differentiation.

In many Mesolithic world-systems the largest villages had only

about 250 people. In other regions there were larger villages, and regions with

different population densities were often in systemic interaction with one

another (Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998). Settlement size hierarchies emerged when a

village at a crucial location, often located at the confluence of two streams,

became the home place of important personages and the location of larger non-residential

ritual spaces such as sweat lodges. Sedentary foragers developed long-distance trading

networks, and the shift from nomadism to sedentism can be understood as a

transition from a system in which people

moved to resources to one in which resources were moved to people.

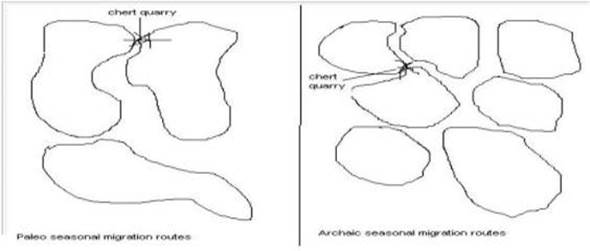

The spatial network aspects of this transition are interesting. As

we have seen above in the description of the emergence of smaller seasonal

migration circuits and regionally differentiated tool styles, nomadic systems

went from spatially very large (in the sense that people used larged territories on a part-time basis, to smaller, and to

very small with the emergence of sedentism. But the settlement systems of

sedentary peoples began again to get larger if we consider the rise of trade

networks that emerged to link settlements that were distant from one another

(see Figure 2). Exchange between settements and

polities allowed for the emergence of greater population density because

villagers were able to obtain needed food during periods of scarcity without

resorting to the raiding of neighboring settlements for supplies. These reciprocal exchange networks grew and

grew, though they also occasionally shrank, repeating pattern that Chase-Dunn

and Hall (1997) have called “oscillation.” Eventually, the systemic

interaction networks became global (Earth-wide) in extent, and it is then that

we call them globalization. So networks first shrank

with the coming of sedentism, and then expanded again to eventually become

completely global with the arrival of intercontinental oceanic voyaging.

Figure 2: Spatial networks shrank and then expanded with the emergence of sedentism

Sedentism

also increased the population growth rate because village life was much more

conducive to child-rearing than was the life of nomads. Families

living in permanent villages could afford to have more closely spaced children

than nomadic peoples could manage (McNeill and McNeill 2003).

This

speeded up the repeated emergence of population pressure on resources which was

a major driver of sociocultural evolution (Kirch 1984,

2017; Johnson and Earle 1987).

The Hilly Flanks

Sedentism arose in multiple locations

throughout the world, which had no known interaction or communication with each

other. This is an example of parallel or

convergent evolution in which somewhat similar circumstances led to somewhat similar

developmental outcomes. It was in regions adjacent to those that first

developed sedentary diversified foraging that Neolithic horticulture first

emerged. In the Levant it was neighbors

of the Natufians who occupied less naturally fecund upland valleys that first

went to the trouble of planting fields of grain (Moore 1982).

When the nomadic foragers

in neighboring areas tried to emulate the sedentary life-style of the Mesolithic

villagers, they found that their less abundant natural stands of grain were

quickly eaten up. To increase the productivity of their lands they experimented

with planting some of the seeds that they had gathered. This intervention

in nature’s production of food resources increased the productivity of land, but required more labor. It allowed more people to be

fed per area of land, once again increasing population density (Hayden

1981). This emergence of horticulture in the “hilly flanks” near the

earlier emergence of sedentary foragers was an early instance of semiperipheral development in which jealous hill dwellers were

willing to work harder to catch up with neighboring village-living low landers.

The emergence of horticulture was a

continuation of the trend from large nomadic circuits to smaller circuits to

sedentism and then to intensified production. Horticulture allowed villages to

be larger in population size. As with sedentism, horticulture emerged

independently in at least eight world regions, another instance of parallel

evolution.

The next steps in intensification of

production and the emergence of yet larger settlements occurred with the

formation of chiefdoms on the Susiana Plain (in what is now Iran) that used

small-scale irrigation systems to increase the productivity of agriculture. The

organization and coordination of irrigation projects is favored by the

emergence of hierarchy within polities, as has been shown in a recent study of

155 small-scale polities in Austronesia (Sheehan et al. 2018). But the first chiefdoms on Earth were in a region in

the fertile crescent not far from where sedentism and horticulture had first

emerged. The rise of chiefdoms produced the first two-tiered settlement size

hierarchies.

Settlement Size Hierarchies

The spatial aspect of population density is one of the most

fundamental variables for understanding the constraints and possibilities of

human social organization. The “settlement size distribution”—the relative

population sizes of the settlements within a region—is an important and easily

ascertained aspect of all sedentary social systems. And, the functional

differences among settlements are a basic feature of the division of labor that

links households and communities into larger polities and interpolity

networks. The emergence of social hierarchies is often related to and inferred

from the size hierarchy of a set of settlements. The building of monumental

architecture in larger settlements has been closely associated with the

emergence of more hierarchical social structures—complex chiefdoms and early

states.

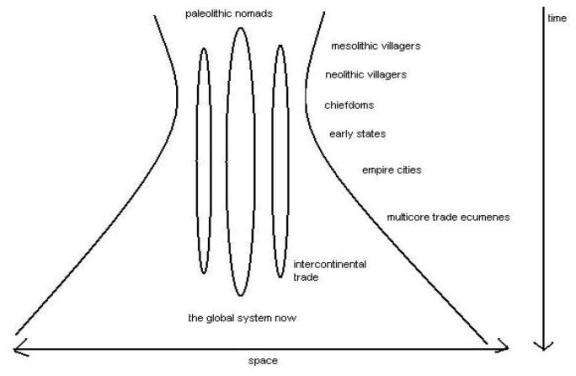

The spatial relationships among settlements in a region and their

relative sizes can be infered from archeological evidence,

and so this is an empirically useful pattern that allows us to compare

preliterate systems with those for which we have documentary evidence. Figure 3

below shows Hans Nissen’s drawings of 1-tiered (a), 2-tiered (b), 3-tiered (c)

and 4-tiered (d) settlement size hierarchies.

Figure 3:

Settlement size hierarchies (Nissen 1988:42)

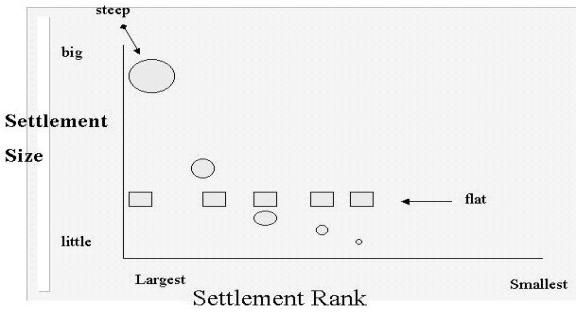

Settlement

size distributions are often graphed to show the relative population sizes of

the settlements in a region. Figure 4 shows a steep settlement size

distribution in which the largest settlement is much larger than the second

largest, and a flat distribution in which all the settlements are about the

same size. Urban geographers suggest that a spatial size hierarchy is often

related to the distribution of functions across settlements and transportation

costs (Christaller 1966). Production of goods and

services that can easily be distributed across a whole region from a

central place will tend to be located in the largest

settlement, whereas products that cannot easily be stored or transported will

be produced locally in the smaller settlements. The “range of goods” creates

the space economy. This approach was developed to describe market societies, but is also relevant for understanding settlement

systems in which exchange was organized as reciprocity, because transportation

costs and labor time had to be considered in the effort to be generous.

Urban

geographers contend that there is a tendency for settlement size hierarchies to

approximate a rank-size or lognormal size distribution. A rank-size

distribution exists when the 2nd largest settlement is ½ the

size of the largest, the 3rd largest is 1/3 the size of the

largest, etc. A lognormal distribution is similar in shape. It exists when the

ranked population sizes of settlements in a region fall on a straight line when

the population sizes have been transformed to a logarithmic scale. “Urban

primacy” is said to exist when the largest city in a region is larger than

would be expected based on the rank-size or lognormal distributions – larger

than twice the size of the second largest settlement. Empirical studies have

shown that many settlement size hierarchies do approximate the rank-size rule,

but some are flat (as with a 1-tiered size distribution) and many are primate

(e.g. Chase-Dunn 1985).

Figure 4: Flat and

steep settlement size distributions

The

rise of cities and states

The original gardening (horticulture) in the Levant spread both

west into the valley of the Nile and east toward Mesopotamia. Larger villages

and towns emerged in rain-watered regions and population growth led to the

migration of farmers away from the original heartland of gardening.

Horticultural techniques also diffused from group to group and were combined

with the domestication of pigs, sheep, and goats. Domestication of animals and

the use of dairy products and meat from domesticated animals eventually made it

possible to move a few notches back up the food chain, reversing some of the

descent that had followed the depletion of big game. Still-nomadic hunter-gatherers

traded with the Neolithic towns, and new forms of specialized pastoral nomadism

developed based on the herding of domesticated animals in areas that were

adequate for pasture but not for farming.

The simple model here is that technological development (planting

and animal husbandry) increased population density and this facilitated the

emergence of larger settlements and social hierarchies. McNeill and McNeill

(2003) noted that state formation in East Asia followed the spread of rice

cultivation (e.g. from China to Korea to Japan). They contend that storable and

tradable grain is far more conducive to state formation than are crops that are

not easily stored (such as yams).[8] But

there is evidence from the Chesapeake region of indigenous North America that the

adoption of planting of storeable food does not

always immediately lead to greater complexity and hierarchy (Chase-Dunn and

Hall 1999).

The arrival of maize planting in the Chesapeake region allowed the

formerly Mesolithic diversified foragers living in rather large villages to redisperse into widely spread farmsteads and to reduce the

intensity of their trading and ritual symbolization of group identity and

social hierarchy. So, increasing productivity can, under some conditions, lead

to deconcentration and less social

hierarchy. The ability to produce a surplus does not automatically lead to

hierarchy formation. Surplus production must be possible in

order to support non-producers, but hierarchy formation tends to occur

when population pressures have led to increasing levels of conflict. In the

case of the Chesapeake, the arrival of maize reduced population pressure and so

those hierarchies and larger villages that had already emerged went into

decline. It was not until population pressure had returned after a period of

population growth and increasing competition for land that villages and

hierarchies grew again. New hierarchies emerged to regulate access to scarce

resources and to reduce the intensity of conflict (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter

6).

As villages eventually grew larger, so did trade networks. Craft

specialists began producing for export and importing raw materials. Trade

networks expanded and intensified, but not permanently. All networks exhibited

a pattern of expansion and contraction (oscillation), and these waves were

punctuated by occasional upward sweeps that connected much larger regions. Thus,

the waves of globalization and deglobalization that have been shown to have

occurred in the last 150 years (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000), are only

the most recent and largest instances of a much older pattern of exchange network

expansion and contraction.

To the Flood Plain

According to Nissen (1988: Chapter 3) the first three-tiered

settlement system in Southwest Asia emerged on the Susiana Plain (in what is

now in Iran adjacent to the Mesopotamian flood plain) during the Ubaid period

(5500-4000 BCE). This would indicate the presence of complex chiefdoms,

and Wright (1986) points to the importance of the existence of complex

chiefdoms in a region as the necessary organizational prerequisite for the

emergence of pristine states (states that emerge in a context in which there

have been no previous states). In other words, the first states did not emerge

directly from egalitarian societies. Evidence from Uqair,

Eridu and Ouelli shows that

there were also Ubaid sites on the Lower Mesopotamian flood plain that were as

large as the sites on the Susiana Plain. The Early Ubaid phase at Tell Ouelli shows remarkably complex architecture as early as

anything on the Susiana Plain. Thus, there was an interregional exchange and

warfare network of chiefdoms based on a mix of rain-watered and small-scale

irrigated agriculture. This was the context in which cities and states first

emerged on Earth.

In the next period (Uruk or Late

Chalcolithic from 4000-3100 BCE) the first true city (Uruk)

grew up on the floodplain of lower Mesopotamia, and other cities of similar

large size soon emerged in adjacent locations. Uruk

had a peak population of about 50,000. Surrounding these unprecedentedly

large settlements were smaller towns and villages that formed the first

four-tiered settlement systems (Adams 1966). Other cities soon emerged on

the floodplain constituting a world-system of city-states. For seven centuries

after the emergence of Uruk, the Mesopotamian

world-system was an interactive network of city-states competing with one

another for land, glory and for control of the complicated transportation

routes that linked the Mesopotamian floodplain with the peoples and natural

resources of adjacent regions.

Mesopotamia was the original heartland of “civilization”

understood as the combination of irrigated agriculture, writing, cities, and

states. States also emerged somewhat later in the Uruk

period on the Susiana Plain (Wright 1998) and these also developed four-tiered

settlement systems (Flannery 1998:17). This was an instance of uneven development --

the transition from an inter-regional interchiefdom

system to an inter-city-state system that emerged first in Mesopotamia and then

spread to the adjacent Susiana plain.

Both cities and states got larger with the development of social

complexity, but they did not grow smoothly. Rather there were cycles of growth

and decline and sequences of uneven development in all the regions of the world

in which cities and states emerged. It was the invention of new techniques of

power, production and exchange that ultimately made possible the more complex

and hierarchical societies that emerged. The processes of uneven development by

which smaller and newer semiperipheral settlements

overcame and transformed larger and older ones has been a fundamental aspect of

sociocultural evolution since the invention of sedentary life. And sociocultural

evolution is somewhat analogous to ecological succession. Higher levels of

complexity cannot emerge directly out of low levels. Production of surplus and

the formation of chiefdoms must form the “institutional soil” out of which

state formation can grow. But states do not form automatically. They are the

products of human innovation in a situation in which they have been made

possible by earlier developments, and in which they can solve problems that are

posed under current conditions. Thus, there is a degree of historical

contingency and agency in the process, and this is very evident in the pattern

of semiperipheral development, because it is not all semiperipheries that transform the systems of which they

are a part.

Sedentary/Nomadic Coevolution

Sedentary societies interacted with still-nomadic societies from

the beginning of sedentism. The original

core/periphery division of labor was between sedentary and nomadic foragers. As

sedentary societies developed horticulture, they also domesticated both plants

and animals, especially in ancient Southwest Asia and Egypt. Domesticated wheat

and barley retain their grains longer and are easier to harvest than the wild

varieties. Foragers had lived with dogs for millennia, but goats, sheep, pigs,

cattle, donkeys, horses and cattle were domesticated by either sedentary

peoples, or by nomadic peoples who became pastoralists in interaction with

sedentary farmers. Archaeologists have studied farmer-forager interactions in

many contexts (e.g. Gregg 1988, 1991). Nomadism co-evolved with sedentism, a

process most famously described for East and Central Asia by Owen Lattimore

(1940) where Central Asian steppe nomads became specialists in the herding of

sheep and horses, trading meat and animals with farmers along the steppe

frontier. Nomadic pastoralists played an important role in the formation of

sedentary states and empires because they not only supplied meat and animal

products, but they soon underwent political evolution as well. The Central

Asian steppe nomad confederacies were able to mobilize large cavalries to

attack agrarian empires, and they both pillaged and extracted tribute in a

process most clearly described by Thomas Barfield (1989). It was also former

nomadic pastoralists who formed sedentary semiperipheral

states on the edges of old core regions, and who were often the protagonists of

empire formation when they conquered adjacent core states. Thus, the dynamics

of sedentary/nomadic relations played an important role in the evolution of the

tributary modes of accumulation – the uses of institutionalized coercion to

structure a system of hierarchical exploitation and domination.

Power and size: cities and empires

What is

the relationship between the sizes of settlements and power in intergroup

relations? Under what circumstances does a society with greater population

density have power over adjacent societies with lower population density, and

when might this relationship not hold? Population density is often

assumed to be a sensible proxy for relative societal power. Indeed, Chase-Dunn

and Hall (1997) employ high relative population density as a major indicator of

core status within a world-system. But Chase-Dunn and Hall are careful to

distinguish between “core/periphery differentiation” and “core/periphery

hierarchy.” Only the latter constitutes actively employed intersocietal

domination or exploitation, and Chase-Dunn and Hall warn against inferring

power directly from differences in population density.

In many world-systems, military superiority is a key dimension of intersocietal relations. Military superiority is generally

a function of population density and the proximity of a large and coordinated

group of combatants to contested regions. The winner of a confrontation is that

group that can bring the larger number of combatants together quickly.

This general demographic basis of military power has been transformed by

military technology, including transportation technologies. Factors such as

better weapons, better training in the arts of war, faster horses, better

boats, greater solidarity among soldiers and their leaders, as well as

advantageous terrain, alter the simple correlation between population size and military

power.

Ironically, George Modelski’s (2003)

important study of the growth of world cities completely ignored the growth of

states and empires, though Modelski is himself an

astute scholar of international relations and geopolitical power. Modelski contended that cities were the most important

driving force of world system evolution and that we may conveniently ignore

states and empires. The relationship between political power and settlements

itself evolved over the millennia, so that analysis of the relationship between

size and power is necessary to understand what happened.

The most important general exception (in comparative evolutionary

perspective) to the size/power relationship is the phenomenon of semiperipheral development mentioned

above. The pattern of uneven development by which formerly more complex polities

lost their place to “less developed” polities has taken several forms depending

on the institutional terrain on which interpolity

competition was occurring. Less relatively dense semiperipheral

marcher chiefdoms often conquered older core chiefdoms to create larger paramount

chiefly polities (Kirch 1984). Likewise, semiperipheral marcher states, usually recently settled

peripheral peoples out on the edge of an old region of core states, frequently were

the agents of a new core-wide empire based on conquest (Mann 1986; Turchin 2003).

Another exception is the phenomenon of semiperipheral

capitalist city-states –polities in the spaces between tributary empires and

states that specialized in long-distance trade and commodity production.[9]

Though these were rarely the largest cities within the world-systems dominated

by tributary empires, they played a transformational role in the expansion of

production for exchange and commodification in the ancient and classical world-systems.

And, less dense semiperipheral Europe was the locus

of a virile form of capitalism that condensed in a region that was home to many

unusually proximate semiperipheral capitalist

city-states. This development, and the military technology that emerged in the

competitive and capitalist European interstate system, made it possible for

less dense Europe to erect a global predominance over the more densely

populated older core regions of Afroeurasia

(Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997; Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2016).

The more recent hegemonic ascent of formerly semiperipheral

national states such as England and the United States are further examples of

the phenomenon of semiperipheral development.

The phenomenon of semiperipheral

development does not totally undermine the proposition that societal power and

demographic size are likely to be correlated. What it implies is that this

correlation can be overcome by other factors, and that these processes are not

entirely random. Denser core polities are regularly overcome or out-competed by

less dense semiperipheral polities, but it does not

follow that all semiperipheral or peripheral regions

have such an advantage. On the contrary, in most world-systems most low-density

polities are subjected to the power of more dense polities. Semiperipheral development is a rather important exception

to this general rule.

Why should a settlement system have a steeper size distribution

when there is a greater concentration of power? The simple answer is that large

settlements, and especially large cities, require greater concentrations of

resources to support their large populations. Therefore, population size has

itself been suggested as an indicator of power (Morris 2010, 2013; Taagepera, 1978: 111). But these resources may be

obtainable locally and the settlement size hierarchy may simply correspond to

the geographical distribution of resources. People cluster near oases in a

desert environment. In such a case it is not the political or economic power of

the central settlement over surrounding areas that produces a centralized

settlement system, but rather the geographical distribution of necessary or

desirable resources (water). In many systems, however, we have reason to

believe that relations of power, domination and exploitation do affect the

distribution of human populations in space. Many large cities are as large as

they are because they can draw upon far-flung regions for food and raw

materials. If a city can use political/military power or economic power to

acquire resources from surrounding cities, it will be able to support a larger

population than the dominated cities can, and this will produce a hierarchical settlement

size distribution.

Of course, the effect can also go the other way. Some cities can

dominate others because they have larger populations, as discussed above. Great

population size makes possible the assembly of large armies or navies, and this

may be an important factor creating or reinforcing steep settlement size

distributions.

The relationship between power and settlement systems is

contingent on technology as well as political and economic networks manifested

through their institutions. Thus, the relationship between urban growth and

decline sequences and the growth/decline sequences of empires varies across

different systems or in the same regional system over time as new institutional

developments emerge. We know that the development of new techniques of power,

as well the integration of larger and larger regions into systems of interaction,

production and trade, facilitate the emergence of larger and larger polities as

well as larger and larger cities. Thus, there has been a secular trend at the global level

and within regions between settlement sizes and polity sizes over the past six

millennia.

Studies of the relationship between the rise and fall of empires

and the growth/decline phases of the largest cities in the same regions have

found differences in the temporal relationship between the growth and decline

of largest cities and largest empires. Partial correlations that take out the

long-term trend show that the medium-term relationship between city and empire

growth is significantly positive in Mesopotamia (2800 BCE-650 BCE), South Asia

(1800 BCE-1500 CE), and Europe (430 BCE-1800 CE), but not in Egypt, West Asia,

and East Asia (Chase-Dunn, Alvarez, and Pasciuti

2005: Table 5.2). In the regions in which there are significant correlations

this is sometimes due to the big empires building their own big capital cities,

but at other times a big city appears that is outside of the largest empire.

This suggests that regions go through general phases of expansion and

contraction in which both cities and empires grow and then decline, and this

supposition is confirmed by the finding in all regions of high partial

correlations between the growth/ decline phases of largest and second largest

cities (Chase-Dunn, Alvarez, and Pasciuti 2005: Table

5.3). And, rather surprisingly, there is a similar set of significant positive

partial correlations in all five regions studied between the growth/decline

phases of largest and second largest empires (Chase-Dunn, Alvarez, and Pasciuti 2005: Table 5.4). This latter is surprising

because territorial growth is a zero-sum game among adjacent empires, and yet

the medium-term temporal correlations are positive, indicating that empires get

larger and smaller together within regions. This is strong evidence that

regions experience cycles of growth and decline that affect both cities and

states.

We should also note an important finding reported in Gilbert Rozman’s (1973) comparison of the rise of cities in Japan

and China. Rozman notes that in China early dynasties

built large primate capitals in a context of agricultural villages, but it took

2000 years for this to evolve into a log-normal city-size distribution with

middle-sized cities performing intermediary roles linking the capital with the villages.

In Japan the process started later but the emergence of middle-sized cities

occurred much more quickly because the Japanese adopted the Chinese

organizational and institutional feature that facilitated the emergence of

middle-sized cities.

To better understand the timing and

location of scale changes in the sizes of cities, George Modelski

(2003) improved Tertius Chandler’s (1987) compendium of the population sizes of

largest cities since the Bronze Age.[10]

Studies of the populations sizes of the largest cities in world regions show

that there have been cycles in which the largest city in each region increased

in size and then decreased in size and these cycles were punctuated by

occasional upsweeps in which the largest city increased to a size that was a

lot bigger than that of the earlier size peaks.[11] From

studies of the growth and decline of large cities Modelski

(2003) and Fletcher (1995) both noticed the emergence of size ceilings before

an upsweep to the next larger ceiling. Fletcher contended that, in addition to

resource constraints on the sizes of settlements, large settlements require the

invention of institutions that allow large numbers of people to live close to

one another. Settlement sizes increased when one polity in a region figured out

how to make a large city work, and then other polities in adjacent regions copied,

and sometimes improved upon, these techniques and so their cities were able to

catch up in size with the earlier large city. A size ceiling was reached because of both resource

and institutional constraints.

The SetPol Research Working Group has identified

those instances in which the scale of cities significantly changed (upsweeps

and downsweeps) (Inoue et al. 2015)

and has begun testing the hypothesis that these scale changes were caused

by semiperipheral marcher states

(Inoue et al. 2016). In

our studies of upsweeps and non-core (peripheral and semiperipheral)

marcher states we examined four regional world-systems (Mesopotamia, Egypt,

East Asia, and South Asia) as well as the expanding central political/military network

that is designated by David Wilkinson’s (1987) temporal and spatial bounding of

state systems since the Bronze Age. We found that nine of the eighteen urban upsweeps

we studied were produced by noncore marcher state conquests and eight directly

followed, and were caused by, upsweeps in the territorial sizes of polities

(Inoue et al. 2015). Whereas about half of the

upsweep events were caused by one or another form of non-core development,

there were a significant number of upsweep events in which the causes seem to

be substantially internal to the polity that carried out the upsweep (Inoue et

al. 2016). Another important finding is that collapses, in

which the largest settlements in a region go down below the level of the

earlier trough, and stay down for a long period, are rather rare. Individual

cites collapse, but systems of cities rarely do.

The modern world city network

The problem of sustainable urbanization is crucial for the human

encounter with the consequences of our ballooning environmental footprint (Gruebler and Buettner

2013). Over half of the human

population of the Earth now lives in very large cities, and these have spread

rapidly over the land as population densities within cities have decreased

(suburbanization) and cities have become interconnected into huge city-regions.

The size hierarchy of world cities has been flattening as megacities in the

non-core countries have caught up in terms of overall population size with the

global cities of the core. This flattening has important implications for

theories of urban growth, globalization and the future of global

inequalities. This section considers the conceptualization of world

cities and city-regions and the idea of a global system of cities. We shall

consider the global city-size distribution and the implications of its

flattening for the question of the limits of settlement size and the problems

of how to spatially bound cities and city-regions. And, we further discuss the

emergence of low density and multicentric cities.

The role of city systems in

the reproduction and transformation of human social institutions was altered by

the emergent predominance of capitalist accumulation. Whereas most of the

important cities of agrarian tributary states were centers of control and coordination

for the extraction of labor and resources from vast empires by means of

institutionalized coercion, the most important cities in the modern world have

increasingly supplemented the coordination of force with the manipulations of

money and the production of commodities. Many of those

who studied the

early modern world-system noted the importance of cities as primary nodes

through which goods and services flowed and the importance of finance capital

and its relationship with state power in the core (Arrighi

1994; Braudel 1984).

The

long rise of capitalism was promoted by semiperipheral

capitalist city-states, usually maritime coordinators of trade protected by

naval power. The Italian city-states of Venice and Genoa are perhaps the most

famous of these, but the Phoenician city-states of the Mediterranean exploited

a similar interstitial niche within a larger system dominated by tributary

empires. These capitalist trading

city-states rewired, expanded and intensified the existing networks of

exchange. The niche pioneered by capitalist city-states expanded and became

more predominant in the guise of core capitalist nation-states in a series of

transformations from Venice and Genoa to the Dutch Republic (led by Amsterdam)

and eventually the Pax Britannica coordinated by the great

world city of the nineteenth century, London (Chase-Dunn and Willard 1994). Thus,

did capitalism move from the semiperiphery to the

core, constituting a world-system in which the logic of profit making had

become more important than the logic of tribute and taxation. In 1900 CE London

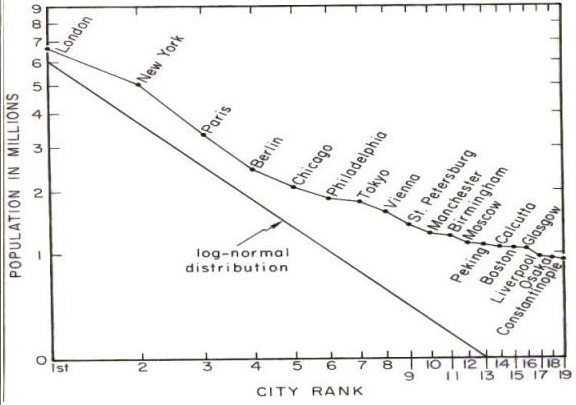

was still the largest world city, but New York was coming up fast (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: The world city size distribution in

1900 CE

Within London the political and financial functions were spatially

separated: empire in Westminster and money in the City. In the twentieth century

hegemony of the United States these global functions became located in separate

cities (Washington, DC and New York). Thus, the role of cities in

world-systems changed greatly as capitalism became the predominant mode of

accumulation over the last 500 years. In the tributary world-systems

the biggest cities were the capitals of empires based on their ability to

extract resources using institutionalized coercion (armies, bureaucracies,

etc.) Capitalist cities existed, but they were in the semiperipheral

interstices between the large tributary empires. With the rise of Europe,

capitalist cities became the most important cities in the whole world-system.

Amsterdam, London and New York have been the global centers of the modern

world-system.

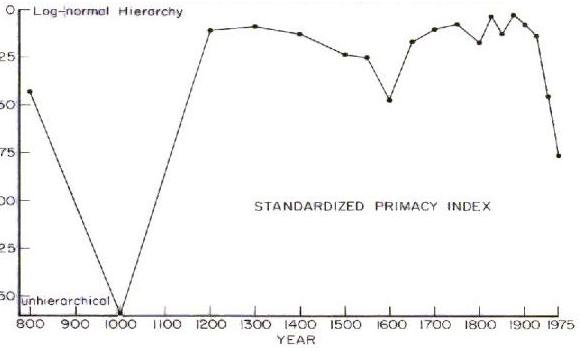

But the relationship between power and size continued to operate

(until recently) in the modern system. Figure 6 displays changes in the settlement

size distribution of the largest cities in the European-centered world-system

since 800 CE (Chase-Dunn and Willard 1994). The city size distribution of

interstate systems is almost always flatter than the size distributions of

settlements within a single polity, because the multicentric political

structure of interstate networks affects the size distribution of settlements

(e.g. Figure 5). Figure 6 uses the “Standardize Primacy Index,” a measure of

deviation from the lognormal rule (Walters 1985). The Europe-centered city system was never

steeper than the lognormal distribution and it was occasionally much flatter.

The periods of flatness mainly correspond with times of political

decentralization in which there was the absence of a hegemonic core power

(Chase-Dunn and Willard 1994). The descent into city-size flatness that began

in the last half of the 20th century has continued since then.

Figure 6: Changes in the city-size distribution

of the Europe-centered system, 800 to 1975 CE

World cities and the global settlement system

According to the theorists of global capitalism it was during the

1970’s that the world-system entered a new period in which the system’s

structure was qualitatively altered by the rise of the neoliberal globalization

project (Castells 1996; Robinson 2014). This new model of development

displaced the Keynesian national development model that had been hegemonic

since World War II. Neoliberalism attacked, and tried to dismantle, the

institutions of reformed capitalism that had been built in response to the

World Revolution of the 1917 – the welfare state, labor unions that had

succeeded in obtaining middle class incomes for primary sector workers,

progressive tax policies, controls on currency manipulations and capital flows,

and public education institutions that had expanded access to formerly excluded

groups. The neoliberals used advantages stemming from new information and

communication technologies to financialize and globalize the world economy,

with the export of manufacturing jobs from the core to the semiperiphery

and periphery and the rise of global cities exercising economic power over the

global economy (Sassen 1991). John Friedmann’s (1986)

“world city hypothesis” identified a set of world cities and the contradictory

relations globalized production and management and the territorialized political

networks of the international system of states.

Although

the global city network in recent decades is hierarchical, with “world cities”

at the top (Friedmann 1986; Sassen 2001), according

to Alderson and Beckfield (2007) this hierarchy does

not exactly mirror the tripartite core/periphery hierarchy because the world city network

became partially decoupled from the geopolitical network of states over the

course of 20th

century globalization. But, contrary to the

neo-liberal claim that there is now a level

playing field (Friedman 2006), the structure of the world city system network

has not become less hierarchical across the era of globalization (Alderson and Beckfield 2007). In fact, the world city network became

more unequal when some cities such as New York, London, and Tokyo gained more

control over the finances of the world economy relative to other megacities

such as those in Latin America (Timberlake and Smith 2012).

Saskia Sassen and others have further developed

the global city hypotheses. Global cities acquired new functions beyond acting

as centers of international trade and banking. They became: (1) concentrated

control locations in the world-economy that use advanced telecommunication

facilities, (2) important centers for finance and specialized producer service

firms, (3) coordinators of state power, (4) sites of innovative post-Fordist

forms of industrialization and production, and (5) markets for the products and

innovations produced (Brenner 2004; Sassen 2006).

These structural shifts in the functioning of cities “impacted both the

international economic activity and urban form where major cities concentrate

control over vast resources, while financial and specialized service industries

have restructured the urban social and economic order” (Sassen

1991: 4). During the 1990’s New York became specialized in equity trading,

London in currency trading and Tokyo in large bank deposits (Slater 2004).

Beaverstock, Smith and Taylor

(1999) and Taylor (2003) used Sassen’s focus on

producer services to classify 55 alpha, beta and gamma world cities based on

the presence of office networks and headquarters of accountancy,

advertising, banking/finance and law firms (see Figure 7.)

Figure 7: Alpha, beta and gamma world

cities according (Beaverstock, Smith and Taylor 1999)

The hierarchy of global cities shown in Figure 7 provides an

important insight into the world settlement system that has emerged in the

period of neoliberal global capitalism. Though the world city-size distribution

based on the population sizes of the largest cities has flattened since 1950,

this has not produced a flat globalized world in which a core/periphery

hierarchy no longer exists. Rather the world cities of the Global North

continue to concentrate the command and control functions of the world economy,

while joined to some extent by megacities in the rising countries of the semiperiphery in Asia and Latin America and including a

third tier of megacities in peripheral countries -- huge metropoli

containing vast numbers of recent migrants from the country-side who subsist in

informalized slums lacking regular employment and urban services (Davis 2006). [12]

Much of the research on the global city system and affiliated

networks has been based on case studies of individual cities that seek to

identify the processes leading to their emergence and positioning within the

larger system. Janet Abu-Lughod (1999) traced the

developmental histories of New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles through

their upward mobility in the world city system (see also Taylor and Lang 2005) While these U.S. metropoles share similar

characteristics with other world cities, they have substantial differences in

geography, original economic functions, transportation, and political history that

make the stories of each fascinating instances of globalization and local

peculiarities (see also Davis 1992).

City

Regions

Another

phenomenon of recent urbanization is the emergence of city-regions, large areas

in which big cities are located rather closely to one-another and intervening

areas are mainly suburbanized. Urban geographers have noted that populations in

the rural areas and small towns of core countries are thinning and people are

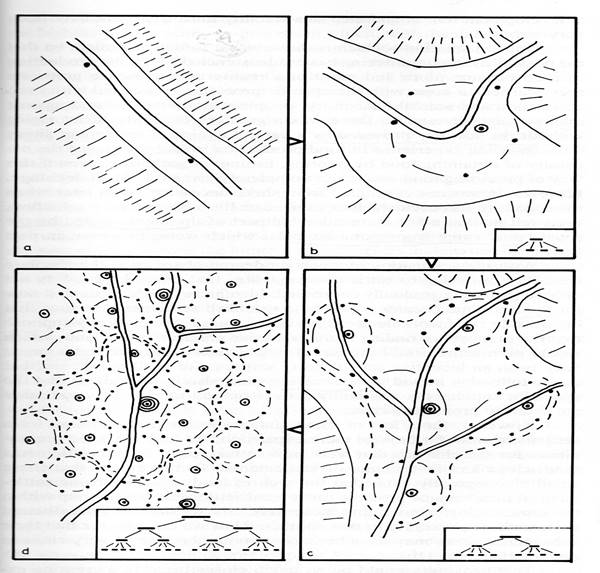

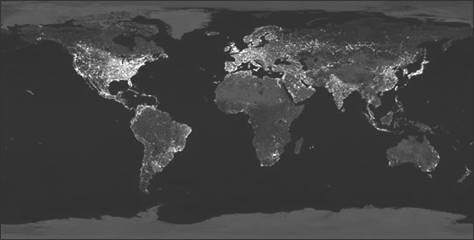

concentrating in these city regions (Scott 2001; Simmonds and Hack 2000; Segbers 2007). The city region phenomenon is made plain by observing

global maps that show city lights at night produced from satellite and shuttle

images (see Figure 8).

All

the continents have city regions, but the largest are those found in the

eastern half of the United States and the western portion of Europe, with

several other regions also displaying this phenomenon. These city regions are

linked together spatially by overlapping suburban areas.

Figure 8: City lights photographed from satellites and shuttles

The

flattening of the global city-size distribution since 1950, shown in Figure 6

above, has several causes. As in earlier periods, the city-size distribution

became less hierarchical (flatter) during times in which a global hegemon was

in decline. The cities of challenging powers grow, and the cities of the former

hegemon cease to grow as fast. The recent descent into flatness of the world city size

distribution is partly due to the declining hegemony of the United States and

the rise of challengers with very large cities. Many of the world’s largest

cities are now in the semiperiphery and the periphery.

Changes the city-size distribution reflect to

some extent changes in the distribution of economic and political/military

power. The flattening since the 1950s is partly due to the rapid growth of

large cities in Japan and China. But megacities in the Global South have also

grown greatly during the period of recent globalization. As mentioned above,

these megacities in non-core countries are very different animals, despite

their large size. The neoliberal structural adjustment policies of the

International Monetary Fund, which were part of the globalization project,

imposed austerity on countries of the Global South and encouraged large-scale

export agriculture that drove small farmers from the land into the Planet of Slums (Davis 2006). Another factor that accounts for cities in

the Global South catching up with core cities in population size has to do with

differences in the demographic transition. Most core countries have achieved a

replacement fertility rate, but most of the Global South still has a higher

fertility rate and faster population growth, boosting the growth of megacities.

Roland Fletcher (personal communication) contends that

contemporary institutional and infrastructural inventions only allow for

megacities to function at maximum populations of around twenty million and this

serves as a kind of ceiling effect which has allowed cities in the Global South

to catch up in terms of population size with the largest cities in the core

states. Fletcher’s notion of an upper limit on the size of large cities may

also be part of the explanation for the emergence of city-regions rather than

gigacities.

The

size and density of city-regions are related to global differences in the level

of economic development. The global city-region-size hierarchy is related to differential

economic and political/military power. Countries in the periphery have

succeeded in producing very large megacities, but their city-regions are not as

large and dense as those in the core (see Figure 8 above).

The future city of humans

Over

half of the 7.6 billion people on Earth now live in cities. The low-density

suburban sprawl that has taken over the process of urban growth in the core is

immensely expensive in terms of resource use. Urbanization has a huge direct

effect on the environment, as cities absorb heat from the sun and then release

it, and humans use great amounts of energy in cities, which contributes to

global warming. The “urban heat island,” in which urban regions are hotter than

surrounding areas because of energy usage and because building materials absorb

more heat from the sun (Sailor 2011), is an important phenomenon that is

contributing to warming.

While many core cities have deindustrialized, large cities

in the semiperiphery have industrialized and are now

the new sites of intense labor struggles (Silver 2003). The global “reserve

army of labor” (rural people still not employed in the formal economy) is still

large but the long-run tendency for wages, materials and taxes to rise will likely

resume and continue, eventually causing a crisis for capitalist accumulation

(Wallerstein 2003). The expansion of the sharing economy during the neoliberal

crackdown on wages will also challenge the logic of capitalism (Mason 2015).

Peter Taylor (2003) contends that globalization has decreased the

importance of nation-states and increased the importance of cities, and that

this may be a good thing because cities are more easily governable by

communities of citizens. Human settlement systems have been strongly involved

in the processes of sociocultural evolution for thousands of years as both

cybernetic nodes of innovation, and in the processes of uneven development that

have led to the rise and fall of states, empires and modern hegemons. Regarding

the latter, we can expect that new forms of governance relevant to solutions of

the emergent problems of the twenty-first century may be invented and

implemented in the cities of the Global South, especially Brazil, India, Mexico

and China. Curitiba, Brazil has already successfully demonstrated a new form of

sustainable urbanism that will become increasingly relevant as the natural

resources that have been the basis of urban sprawl become further depleted

(Rabinowitz and Leitman 1996). The Pink Tide left

populist regimes that emerged in Latin America in reaction to neoliberal

globalization (Rodrik 2018) were important supporters of transnational global

justice movements that have contested neoliberal global governance and pushed

toward a new kind of globalization from below. The cities of the Global

South remain fertile spaces for finding solutions for our increasingly

urbanized planet.

The world settlement system has become a network of large cities

and city regions that contain over half of the human population. There are

immense inequalities between those powerful global cities that control global

financial and military apparatuses that affect everyone and the huge cities of

the Global South that face growing problems of poverty, disease and insecurity.

The modern world-system has, over the past several centuries, exhibited cycles

of globalization (Chase-Dunn, Brewer, and Kawano 2000), the rise and fall of

hegemonic core powers, and upward trends in population growth and economic

development. The massive global inequalities that emerged during the 19th

century have not been reduced despite the rapid economic development of India and China (Bornschier 2010).

The three

main challenges of the 21st century are:

addressing

huge environmental issues and moving in the direction of sustainable

development; and

addressing

the issue of huge inequalities between the global North and South.

restructuring

global governance to prevent a recurrence of warfare among the great powers and

to improve the capacity for managing the other two challenges.

All the large cities of the world will be affected by the timing

and rapidity of these emerging crises and so a plan for restructuring the

global system to more effectively meet these challenges is greatly

needed. The strengthening and democratization of the United Nations would enhance

global cooperation for meeting these challenges and for supporting the

empowerment of the peoples of the world.

Bibliography

Abu-Lughod, Janet Lippman. 1999. New

York, Chicago, Los Angeles: America’s Global Cities. Minneapolis, MN:

University of Minnesota Press.

Adams, Robert McCormick. 1966. The Evolution of Urban Society: Early

Mesopotamia and Prehispanic Mexico. Chicago: Aldine.

Adams, Robert McCormick and Hans J. Nissen. 1972.

The Uruk

Countryside: The Natural Setting of Urban Societies. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Alderson, Arthur S. and Jason Beckfield.

2007. “Globalization and the World City System:

Preliminary

Results from a Longitudinal Data Set.” Pp. 21-35 in Theories Peter J. Taylor, Ben Deruder,

Pieter Saey and Frank Witlox,

eds., Cities in Globalization: Practices,

Policies and. London: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Anderson, E. N. 2019 Mandate of Heaven. Berlin: Springer VerlagArrighi, Giovanni. 1994. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Time. London:

Verso.

Bar-Yosef, O. and Belfer-Cohen,

A. 1991. “From Sedentary Hunter-gatherers to Territorial Farmers in the Levant.”

Pp 181-202 in S.A. Gregg, ed., Between

Bands and States. Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations,

Occasional Papers #9.

Bean, Lowell John and Harry Lawton. 1976.

"Some Explanations for the Rise of Cultural Complexity in Native

California with Comments on Proto-Agriculture and Agriculture." Pp. 19-48 in Lowell John Bean and Thomas C.

Blackburn, eds., Native Californians: A Theoretical Retrospective. Socorro, NM: Ballena Press.

Beaverstock, J.V., P.J. Taylor

and R.G. Smith. 1999. “A roster of world cities.” Cities 16:

445-458.

Bornschier, Volker. 2010. “On the

evolution of inequality in the world system” Pp. 39-64 in

Christian Suter ed., Inequality Beyond Globalization. New

Brunswick, NJ: Transaction

Publishers.

Bosworth, Andrew. 2000. “The Evolution of the World

City System, 3000 BCE to AD

2000.” In Jonathan Friedman, Barry K. Gills, and

George Modelski Robert A. Denmark eds., World System History: The Social Science of

Long-Term Change. New York: Routledge.

Braudel, Fernand.

1984. Civilization and Capitalism 15th

-18th Century Volume III The Perspective of

the World. London: Collins.

Brenner, Neil. 2004. New

State Spaces: urban governance and the rescaling of

statehood. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Bruegmann, Robert. 2008. Sprawl. Chicago: The University of

Chicago Press.

Chandler, Tertius. 1987. Four thousand years of urban

growth. Lewiston, N.Y.: St. David's University Press.

Castells, Manuel. 1996. The

Rise of the Network Society. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Chapman. A.C. 1957. “Ports of Trade Enclaves in Aztec and

Maya Civilizations” Pp. 114-153 in K. Polanyi, C. Arensberg, and

H. Pearson, eds., Trade and Markets in

the Early Empires. Chicago: Henry Regnery.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 1985. “The coming

of urban primacy in Latin America” Comparative

Urban Research, 11(1-2):14-31.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Alexis Alvarez, and Daniel Pasciuti.

2005. "Power and Size; urbanization and empire formation in

world-systems" Pp. 92-112 in C. Chase-Dunn

and E.N. Anderson, eds., The

Historical

Evolution of World-Systems. New York: Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. and Hall T.D. 1991. “Conceptualizing

Core/Periphery Hierarchies for Comparative Study” Pp 1-44 in C. Chase-Dunn and

T.D. Hall, eds., Core-Periphery Relations

in Precapitalist Worlds. Boulder: Westview Press.

________________________ .1997. Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems. New York: Routledge.

________________________. 1999. “The Chesapeake world-system:

complexity, hierarchy and pulsations of long range

interactions in prehistory.” Presented at the annual meeting of the American

Sociological Association http://wsarch.ucr.edu/archive/papers/c-d&hall/asa99b/asa99b.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher., Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer.

2000. “Trade globalization since 1795: waves of integration in the

world-system.” American Sociological Review 65(1): 77-95..

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. and

Bruce Lerro. 2016. Social Change:

Globalization From the Stone Age to the

Present. New York: Routledge

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Kelly M. Mann. 1998 The Wintu and Their Neighbors: A Small

World-System in Northern California, University of Arizona Press.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. and Susan Manning. 2002. “City systems and

world-systems” Cross-

Cultural Research

36 (4): 379-398. https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/ccr02/ccr02.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. and Willard, A. 1994. Systems of

Cities and World-Systems. [online] Irows.ucr.edu. Available at: https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows5/irows5.htm.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Alice Willard 1994 "Cities in the

Central Political-Military Network Since CE

1200" Comparative

Civilizations Review, 30:104-32 (Spring) 1994.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher., Kawano, Y. and Brewer, B. 2000. “Trade

Globalization since 1795: Waves of Integration in the World-System” American

Sociological Review, 65(1), p.77.

Christaller, Walter. 1966. Central Places in Southern Germany.

Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Collins, Randall. 1978. "Some Principles of Long-term Social

Change: The Territorial Power of

States." Pp. 1-34 in Louis F. Kriesberg, ed., Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change,

Volume 1, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

______________. 1992.

“The Geographical and Economic World-Systems of Kinship-Based and

Agrarian-Coercive Societies.” Review 15(3):373-88.

Davis, Mike. 1992. City of Quartz: Excavating the future in Los Angeles. New York:

Vintage.

_________2006.

Planet of Slums. London: Verso.

Dezzani, Raymond J., and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2010. “The Geography of

World Cities.” Pp. 2969–2986 in Robert A. Denemark,

ed., The International Studies

Encyclopedia, Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Dodgshon, R. A. 1987. The European Past: Social Evolution and

Spatial Order. London: MacMillan.

Fagan, Brian. M. 1991. Ancient

North America. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Feuerstein, G., Kak S. and

Frawley D. 1995. In Search of the Cradle

of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India. Los Angeles: Quest Books.

Flannery, Kent V.

1998. “The ground plans of archaic states.” Pp. 15-57 in G. Feinman

and J. Marcus,

eds., Archaic

States. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research.

Fletcher, Roland. 1995. The Limits of Settlement Growth: A Theoretical Outline. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Friedman,

Thomas L. 2006. The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century. New

York:

Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Friedmann, John. 1986. “The World City Hypothesis.” Development and Change 17(1): 69-83.

Garreau, J. 2011. Edge City: Life on the New Frontier. New

York: Random House.

Gregg, Susan A. 1988. Foragers and Farmers: Population Interaction and Agricultural

Expansion in Prehistoric Europe.

Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

____________, ed.

1991. Between Bands and States.

Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Paper #9, Carbondale,

IL.: Southern Illinois University.

Hall, Thomas D., Christopher

Chase-Dunn, and Hiroko Inoue. 2013. “Wallerstein, Immanuel.” Pp. 909-012 in McGee,

R. Jon and Richard L. Warms, eds., Theory in Social and Cultural

Anthropology, Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA. Sage Publications. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows125/irows125.htm

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Eugene N.

Anderson, Andrew Owen, Rebecca Álvarez, Kirk Lawrence, and

Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2015, “Urban scale shifts since the Bronze Age:

upsweeps, collapses and semiperipheral development.” Social

Science History 39

(2): 175-200.

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, E.N. Anderson,

Kirk Lawrence, Teresa Neal, Dmytro Khutkyy,

Sandor Nagy, Walter DeWinter, and

Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2016. "Comparing World-Systems: Empire Upsweeps and

Non-core marcher states Since the Bronze Age" http://ierows.ucr.edu/papers/irows56/irows56.htm

Jones, Gareth Stedman. 1971. Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship between Classes in Victorian

Society Oxford: Clarendon.

Johnson, A.W. and Earle T. 1987. The Evolution of Human Societies: From Foraging Tribe to Agrarian State.

Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Kirch, Patrick V. 1984. The Evolution of Polynesian Chiefdoms.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

_____________ 2017 On

The Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of

the Pacific Islands Before European Conquest. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Lattimore, Owen.

1940. Inner Asian Frontiers of China. New York: American

Geographical Society,

republished 1951, 2nd ed. Boston: Beacon Press.

Lenski G. and J. Lenski, ed. 1987. Human Societies. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lightfood, K. G. and Feinman G.M. 1982. “Social Differentiation and Leadership

Development in Early Pithouse Villages in the Mogollon

region of the American Southwest”. American

Antiquity, 47(1): 64-86.

Linduff, K.M. 1998. “The

Emergence and Demise of Bronze-Producing Cultures Outside the Central Plains of

China” Pp. 619-643 in V. Mair, ed., The

Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern Central Asia. Volume 2.

Washington, D.C.: The Institute for the Study of Man.

Mason, Paul. 2015. Postcapitalism

New York: Farrer, Straus and Giroux.

McNeill, J. and McNeill W.H. 2003. The Human Web. New York: Norton.

Modelski, George. 2003 World Cities: -3000 to 2000. Washington, DC: Faros 2000

Moore, A. M.T. 1982. “The First Farmers in the Levant” Pp.91-112

in Young, Smith, and Mortenson, eds., The

Hilly Flanks and Beyond: Essays on the Prehistory of Southwestern Asia.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Morris, Ian. 2010. Why the West Rules – For Now. New York: Farrer,

Straus, and Giroux.

Morris, Ian. 2013. The Measure

of Civilization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nassaney, Michael S. and Kenneth E. Sassaman, eds. 1995. Native

American Interactions: Multiscalar Analyses and Interpretations in the Eastern

Woodlands. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Neitzel, Jill E. (ed.) Great

Towns and Regional Polities in the Prehistoric American Southwest and Southeast.

Albuquerque: University of New

Mexico Press.

Nissen, H. J. 1988. The

Early History of the Ancient Near East, 9000-2000 B.C. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the 21st Century.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Puett. M. 1998. “China in Early Eurasian

History: A Brief Review of Recent Scholarship on the Issue.” Pp.699-715. in V.

Mair, ed., The Bronze Age and Early Iron

Age Peoples of Eastern Central Asia. Volume 2. Washington D.C.: The

Institute for the Study of Man.

Rabinovitch, Jonas and Josef Leitman. 1996. “Urban Planning in Curitiba.” Scientific

American 274(3).

Renfrew, Colin R.

1975. "Trade as Action at a Distance: Questions of Integration and

Communication." Pp. 3-59 in J. A. Sabloff and C. C. Lamborg‑Karlovsky,

eds., Ancient Civilization and Trade. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

____________.

1977. "Alternative Models for Exchange and Spatial

Distribution." Pp. 71-90 in T. J.

Earle and T. Ericson, eds., Exchange

Systems in Prehistory,. New York:

Academic Press.

Revere, R.B. 1957. “No Man’s Coast: Ports of Trade in the

Eastern Mediterranean.” Pp.38-63 in K. Polanyi, C. Arensberg,

and H. Pearson, eds., Trade and Markets

in the Early Empires. Chicago: Henry Regnery.

Robinson, W. I.

2014. Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Humanity. Cambridge:

Cambridge University

Press.

Rodrik, Dani. 2019. “Populism and the economics

of globalization.” Journal of

International Business

Policy 1: 12-33.

Rozman, Gilbert. 1973. Urban Networks in Ching China and Tokugawa

Japan. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton

University Press.

Sailor, D. J. (2011). "A review of methods for

estimating anthropogenic heat and moisture emissions

in the urban

environment" International Journal of Climatology 31,2: 189–199

Sassen, Saskia. 1991. Global Cities. Princeton, NJ: