The Development of World-Systems

Emperor Bonaparte

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Hiroko Inoue,

Teresa Neal and Evan Heimlich

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California, Riverside

An

earlier version was presented at the Fourth European Congress on World and

Global History,

September

6, 2014, École Normale Supérieure, Paris.; draft v. 9-16-14, 10590 words

![]()

This is

IROWS Working Paper #86 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows86/irows86.htm

v.

1-1-15, 10422 words

Abstract: This essay discusses conceptual issues that arise from the study of

human social change. The comparative and

evolutionary world-systems perspective is explained as a theoretical research

program for studying long-term social change. This approach employs an

anthropological framework of comparison for studying world-systems, including

those of hunter-gatherers. Problems of spatially bounding whole human

interaction networks are addressed and the utility of a comparative approach to

the study of hierarchical relations among human polities (core/periphery

relations) is examined. The hypothesis of semiperipheral development is

explained and criteria for empirically identifying semiperipheral regions are

specified. World history and global history are the most important evidential

bases, along with prehistoric archaeology, for the comparative study of

world-systems. Getting the grounds of comparison right by correctly

conceptualizing the spatial units of analysis and paying careful attention to

core/periphery relations are crucial issues in the effort to comprehend and

explain the development of world-systems.

The

sociology of development, broadly construed, is the study and explanation of

human social change in general, including the emergence of social complexity

and hierarchy during, and since, the Stone Age. Most of the social science

literature has focused on the transition from “tradition” to “modernity,” which

are usually understood as characteristics of national societies such as urbanization,

industrialization, and the demographic transition. The rise of globalization

studies has shifted the focus to an emerging world society in which

nation-states are understood as interacting organizations that claim

sovereignty over a delimited territory and national societies are seen to be

highly interdependent on the larger global system. The world-systems perspective on modernity

claims that this high degree of interdependence is not a recent phenomenon and

that an important dimension of the global system has been, and continues to be,

its stratification structure that is organized as a core/periphery hierarchy in

which some national societies have far more power and wealth than others.

The world-systems

perspective emerged during the world revolution of 1968 and the anti-war

movement that produced a generation of scholars who saw the peoples of Global

South (then called the “Third World”) as more than an underdeveloped backwater.

It became widely understood that a global power structure existed and that the

peoples of the non-core had been active participants in their own liberation.

The history of colonialism and decolonization were seen to have importantly

shaped the structures and institutions of the whole global system. A more

profound awareness of Eurocentrism was accompanied by the realization that most

national histories had been written as if each country were on the moon. World

history courses had introduced high school and college students to the stories

of non-European civilizations and global history. The nation state as an

inviolate, pristine unit of analysis was now seen to be an inadequate model for

the sociology of development.

This awareness of

a larger global context spread widely as globalization itself became a focus of

public and scholarly discourse. Some versions claimed that the world was now

flat, and that international hierarchy is a thing of the past that has been

transcended by instantaneous communication and the world market. Some of the global historians have claimed,

along with the theorists of a new global stage of capitalism, that the world

had, in the last decades of the twentieth century, transitioned from a set of

weakly linked national economies to a recently emerged single global economy.

Instead, the world-systems perspective sees waves of integration

(globalization) that have occurred throughout human history (Chase-Dunn 1999;

Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014) and the contemporary reproduction of global

inequalities that continue to make global collective action extremely

difficult. We agree with most of Michael Mann’s (2013:3) criticisms of the

“hyperglobalizers” who see a recent radical transformation to a completely

different kind of global social order. Mann’s (2013) analysis of four

inter-related but relatively autonomous strands of political, military,

economic and ideological globalization since 1945 is substantially accurate

despite his metatheoretical presumption that there is no single integrated

global system.

In this essay we

intend to clear up several common misunderstandings about the world-systems

perspective[1] and we

introduce and discuss the conceptual basis for comparing the contemporary

global system with earlier small and middle-sized regional world-systems. It is our contention that the world-systems

perspective is a still-emerging theoretical research program that has great

potential for enhancing our comprehension of the causes of long-term social

change and also as a framework that will be useful to world citizens who are

trying to deal with the problems that our species has shaped for itself in the

21st century.

The two main conceptual issues we shall consider

are:

·

core/periphery relations, and

·

the spatial bounding of whole world-systems

The comparative

world-systems perspective is a strategy for explaining social change that

focuses on whole interpolity systems rather than single polities. The main

insight is that important interaction networks (trade, information flows,

alliances, and fighting) have woven polities and cultures together since the

beginning of human sociocultural evolution.[2] Explanations of

social change need to take whole interpolity systems (world-systems) as the

units that evolve. But interpolity interaction networks were rather small when

transportation was mainly a matter of carrying goods on one’s back or in small

boats. Globalization, in the sense of the expansion and intensification of

larger interaction networks, has been increasing for millennia, albeit unevenly

and in waves (Chase-Dunn 2006; Beaujard 2010; Jennings 2010).

World-systems are

whole systems of interacting polities and settlements.[3] Systemness means that these polities and

settlements are interacting with one another in important ways – interactions

are two-way, necessary, structured, regularized and reproductive. Systemic interconnectedness exists when

interactions importantly influence the lives of people and are consequential

for social continuity or social change. All premodern world-systems extended

over only parts of the Earth. The word “world” refers to the importantly

connected interaction networks in which people live, whether these are

spatially small or large.

There

is also the question of endogenous (internal) systems versus exogenous

(external) impacts. The notion of systemness requires distinction between

endogenous processes that are regularly interactive and systemic, on the one

hand, and exogenous impacts that may have large effects on a system, but are

not part of that system. The diffusion of genetic materials and technologies

can have profound long distance effects even though there are no regularized or

frequent interactions. But single events that have such consequences should not

be considered to be part of a sociocultural system. Climatic changes often have important impacts

on human societies, but we do not try to include them as endogenous variables

in our models of social systems until climate change becomes anthropogenic.

Analogously collision with large asteroids have had huge consequences for

biological evolution, but biologists do not include these as endogenous factors

in biological evolution. Similarly, long distance diffusion of ideas,

technologies, plants and animals is an important process that needs to be

studied in its own right, and its impact on local systems must be acknowledged

and understood, but models of sociocultural change must distinguish between

endogenous processes and exogenous impacts.

Endogeniety vs. exogenous factors is the basic theoretical and empirical

issue that must be sorted out in specification of systemic wholeness.

Only the modern world-system has become a global

(Earth-wide) system composed of national societies and their states. It is a

single global economy composed of international trade and capital flows,

transnational corporations that produce products on several continents, as well

as all the economic transactions that occur within countries and at

local levels. The whole world-system is more than just international relations.

It is the whole system of human interactions. The world economy is now all the

economic interactions of all the people on Earth, not just international trade

and investment.

The modern

world-system is structured politically as an interstate system – a system of

competing and allying states. Political Scientists commonly call this the

international system, and it is the main focus of the field of International

Relations. Some of these states are much more powerful than others, but the

main organizational feature of the world political system is that it is multicentric.

There is, as yet, no world state. Rather there is a system of states. This is a

fundamentally important feature of the modern system and of most earlier

regional world-systems as well.

When we compare

different kinds of world-systems it is important to use concepts that are

applicable to all of them. “Polity” is a general term that means any

organization with a single authority that claims control over a territory or a

group of people.[4]

Polities include bands, tribes and chiefdoms as well as states and empires. All

world-systems are composed of multiple interacting polities. Thus we can

fruitfully compare the modern interstate system with earlier interpolity

systems in which there were tribes or chiefdoms, but no states.[5]

So the modern

world-system is now a global economy with a global political system (the modern

interstate system). It also includes all the cultural aspects and interaction

networks of the human population of the Earth. Culturally the modern system is

composed of: several civilizational traditions, (e.g. Islam, Christendom,

Hinduism, Confucianism, etc.), nationally-defined cultural entities -- nations

(and these are composed of class and functional subcultures, e.g. lawyers,

technocrats, bureaucrats, etc.), and the cultures of indigenous and

minority ethnic groups within states. The modern system is multicultural in the

sense that important political and economic interaction networks connect people

who have rather different languages, religions and other cultural aspects. Most

earlier world-systems have also been multicultural.[6]

But the modern

system also has a single geoculture that has been emerging since the late 18th

century in the context of the

multicultural situation depicted above (Wallerstein 2011b; Meyer 2009). This

geoculture is most importantly structured by the core, but it has also evolved

in the context of a series of world revolutions in which the peoples of the

non-core have contested the global power structure, and these have had

important effects on the content of the geoculture.

One of the

important systemic features of the modern system is the rise and fall of

hegemonic core powers – the so-called “hegemonic sequence” (Wallerstein 1984;

Chase-Dunn 1998). A hegemon is a core state that has a significantly greater

amount of economic power than any other state, and that takes on the political

role of system leader. In the seventeenth century the Dutch Republic performed

the role of hegemon in the Europe-centered system, while Great Britain was the

hegemon of the nineteenth century, and the United States has been the hegemon

in the twentieth century. Hegemons provide leadership and order for the

interstate system and the world economy. But the normal operating processes of

the modern system – uneven economic development and competition among states –

make it difficult for hegemons to sustain their dominant positions, and so they

tend to decline. Thus the structure of the core oscillates back and forth

between unipolar hegemony and a situation in which several competing core

states have roughly similar amounts of power and are contending for hegemony –

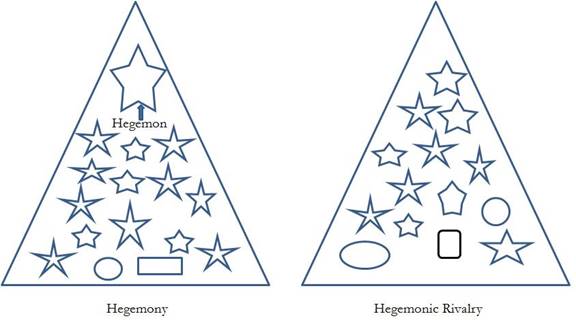

i.e. multipolar hegemonic rivalry (see Figure 1).

Figure

1: Unipolar Hegemony and Multipolar Hegemonic Rivalry in the Core Zone

So the modern world-system is composed of states that are linked to

one another by the world economy and other interaction networks. Earlier

world-systems were also composed of polities, but the interaction networks that

linked these polities were not intercontinental in scale until the expansion of

the Indian Ocean centered system and then European expansion to the Americas in

the long sixteenth century CE. Before that world-systems were smaller regional

affairs. But these had been growing in size with the expansion of trade

networks and long-distance military campaigns for millennia (Bentley 1993;

Beaujard 2005).

Core/Periphery Relations

The notion of

core/periphery relations has been a central concept in both the modern

world-system perspective (Wallerstein 2011a) and in the comparative

world-systems perspective (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997). World-systems are systems

of interacting polities and they often (but not always) are organized as

interpolity hierarchies in which some polities exploit and dominate other

polities.[7] Chase-Dunn and

Hall (1997) redefined the core/periphery distinction to make it more useful for

comparing the modern world-system with earlier regional world-systems.

The intent of

using the word “core” rather than “center” is to clearly signal the awareness

that most interpolity hierarchies are multicentric. There is a region or zone

at the top layer of the hierarchy that is occupied by a set of allying and

competing polities. All hierarchical world-systems go through a cycle of rise

and fall in which a most powerful polity in the core grows and then

declines. But most systems remain

multicentric. The exceptions are what Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997, see also

Scheidel 2009) call “core-wide empires” in which a single polity conquers and

rules an entire core region. These have been rare. Large empires that claim to

control the universe rarely control all the core polities in their interaction

system. Even the Roman Empire never conquered the Parthian Empire.

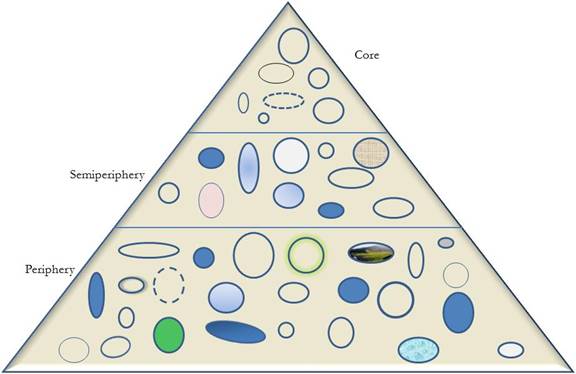

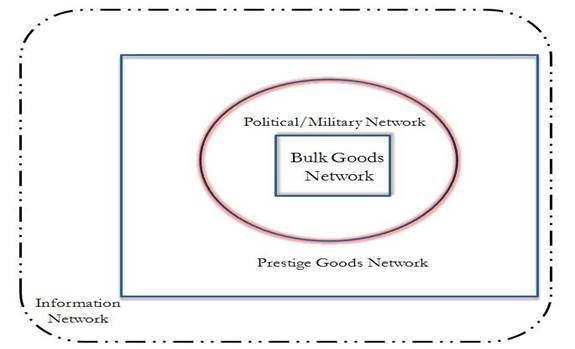

Figure 2: The Structure of a Core/Periphery Hierarchy

The modern

world-system has been, and is still, importantly structured as a core/periphery

hierarchy in which some regions contain economically and militarily powerful

states while other regions contain polities that are much less powerful and

less developed. The countries that are called “advanced,” in the sense that

they have high levels of economic development, skilled labor forces, high

levels of income and powerful, well-financed states, are the core powers of the

modern system. The modern core includes the United States, and the countries of

Europe, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

In the

contemporary periphery we have relatively weak states that are not

strongly supported by the populations within them, and have little power

relative to other states in the system. The colonial empires of the European

core states dominated most of the modern periphery until waves of

decolonization swept away the colonial empires starting in the late 18th

century. Peripheral regions are economically less developed in the sense that

the economy is composed of relatively less capital-intensive forms of

agriculture and industry. Some

industries in peripheral countries, such as oil extraction or mining, may be

capital-intensive, but these sectors are often controlled by core capital.

In the past, peripheral

countries have been primarily exporters of agricultural and mineral raw

materials. But even when they have developed some industrial production, this

has usually been less capital intensive and using less skilled labor than

production processes in the core. The contemporary peripheral countries are

most of the countries in Africa and many of the countries in Asia and Latin

America – for example Bangladesh, Senegal, Haiti and Bolivia.

Figure 3: The contemporary global hierarchy of national societies: core, semiperiphery and periphery (Source: Bond 2013)

The

core/periphery hierarchy in the modern world-system is a system of

stratification in which socially and ecologically structured inequalities are

reproduced by the institutional features of the system. The periphery is not

“catching up” with the core. Rather both core and peripheral regions are

developing, but most core states are staying well ahead of most peripheral

states. Though there is some upward and downward mobility, the overall structure

of inequality has remained quite stable.

There is also a stratum of countries that are in between the core and

the periphery that is called the semiperiphery. The semiperiphery in the

modern system includes countries that have intermediate levels of economic

development or a balanced mix of developed and less developed regions. The

semiperiphery includes large countries that have political/military power as a

result of their large size (e.g. Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil, China, India), and

smaller countries that are relatively more developed than those in the

periphery (e.g. South Africa, Taiwan, South Korea, see Figure 3).

The exact

boundaries between the core, semiperiphery and periphery are unimportant

because the main point is that there is a continuum of economic and

political/military power that constitutes the core-periphery hierarchy. It does

not matter exactly where we draw lines across this continuum in order to

categorize countries. Indeed we could as well make four or seven categories

instead of three. The categories are only a convenient terminology for pointing

to the fact of international inequality and for indicating that the middle of

this hierarchy may be an important location for processes of social change.

There have been a

few cases of upward and downward mobility in the core/periphery hierarchy,

though most countries simply run hard to stay in the same relative positions

that they have long had. The most spectacular case of upward mobility in the

modern core/periphery hierarchy is the United States. Over the last 300 years

the territory that became the United States moved from being outside of the

Europe-centered system (a separate continent containing several regional

world-systems), to the periphery in the colonial era, to

the semiperiphery in the first half of the 19th century, to the core

by 1880, and then to the position of hegemonic core state in the 20th

century, and now its hegemony is slowly declining. An example of downward

mobility is the United Kingdom of Great Britain -- the hegemon of the

nineteenth century and now just another core society.

The contemporary

global stratification system is a continuum of economic and political-military

power that is reproduced by the normal operations of the system. In such a

hierarchy there are countries that are difficult to categorize. For example,

most oil-exporting countries have very high levels of GNP per capita, but their

economies do not produce high technology products that are typical of core

countries. They have wealth but not development. The point here is that the

categories (core, periphery and semiperiphery) are just a convenient set of

terms for pointing to different locations on a continuous and multidimensional

hierarchy of power. It is not necessary to have each case fit neatly into a

box. The boxes are only conceptual tools for analyzing the unequal distribution

of power among countries.

When

we use the idea of core/periphery relations for comparing very different kinds

of world-systems we need to broaden the concept and to make an important

distinction (see below). But the most

important point is that we should not assume that all world-systems have

core/periphery hierarchies just because the modern system does. It should

be an empirical question in each case as to whether core/periphery relations

exist. Not assuming that world-systems

have core/periphery structures allows us to compare very different kinds of

systems and to study how core/periphery hierarchies themselves have emerged and

evolved.

In

order to do this it is helpful to distinguish between core/periphery

differentiation and core/periphery hierarchy. “Core/periphery differentiation” means that

societies with different degrees of population density, polity size and

internal hierarchy are interacting with one another. As soon as we find village

dwellers interacting with nomadic neighbors we have core/periphery

differentiation. “Core/periphery

hierarchy” refers to the nature of the relationships between societies. This kind of hierarchy exists when some

societies are exploiting or dominating other societies. Examples of

intersocietal domination and exploitation would be the British colonization and

deindustrialization of India, or the conquest and subjugation of Mesoamerica

and the Andean region by the Spaniards. Core/periphery hierarchy is not unique

to the modern Europe-centered world-system of recent centuries. Both the Roman

and the Aztec empires conquered and exploited peripheral peoples as well as

adjacent core states.

Distinguishing

between core/periphery differentiation and core/periphery hierarchy allows us

to deal with situations in which larger and more powerful societies are

interacting with smaller ones, but are not exploiting them. It also allows us

to examine cases in which smaller, less dense societies may be exploiting or

dominating larger societies. This latter situation definitely occurred in the

long and consequential interaction between the nomadic horse pastoralists of

Central Asia and the agrarian states and empires of China and Western Asia. The

most famous case was that of the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan, but

confederations of Central Asian steppe nomads managed to extract tribute from

agrarian states long before the rise of Mongols (Barfield 1993; Honeychurch

2013).

The

question of core/periphery status also needs to be considered with regard to

different spatial scales of interaction. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) note that

regional world-systems may have important interaction networks that have different

spatial scales (see below). They adopt a “place-centric” approach to spatially

bounding interaction networks that begins from a focal settlement or polity.

The network is spatially bounded by considering how many indirect links are

needed to include all the interactions that have an important impact on the

reproduction or transformation of institutions at the focal place. Bulk goods

networks, which were usually relatively small, and political-military networks

(interpolity systems), which were usually somewhat larger, were important in

all systems, and prestige goods networks, which were often much larger, were

important in some systems but not others. The issue of core/periphery status

always needs to be asked for the bulk goods and political-military networks,

and also for the prestige goods level if prestige goods played an important

role in socio-cultural reproduction or change.

Spatial Boundaries of World-Systems

Whole interaction networks are composed of

regular and repeated interactions among individuals and groups. Interaction may

involve trade, communication, threats, alliances, migration, marriage, gift

giving or participation in information networks such as radio, television,

telephone conversations, and email. Conflict is also an important form of

sociation both within and between polities. Warfare, ranging from ritual

contests to ethnocide, has been an important player in the group selection

process that produces sociocultural evolution (Morris 2014, Turchin 2011).

Important interaction networks are those that affect peoples’ everyday lives,

their access to food and necessary raw materials, their conceptions of who they

are, and their security from, or vulnerability to, threats and violence.

World-systems are fundamentally composed of interaction networks.

One big

difference between the modern world-system and earlier systems is the spatial

scale of different types of interaction networks. In the modern global system

most of the important interaction networks are themselves global in scale. But

in earlier smaller systems there was a significant difference in spatial scale

between networks in which food and basic raw materials were exchanged and much

larger networks of the exchange of prestige goods or luxuries. Different kinds of important interaction had different spatial

scales. Food and basic raw materials we call “bulk

goods” because they have a low value per unit of weight. It is uneconomical to

carry bulk foods very far under premodern conditions of transportation.

Imagine that the

only type of transportation available is people carrying goods on their backs

(or heads). This is a situation that actually existed everywhere until the

domestication of beasts of burden. Under these conditions a person can carry,

say, 30 kilograms of food. Imagine that this carrier is eating the food as s/he

goes. So after a few days walking all the food will be consumed. This is the

economic limit of food transportation under these conditions of transportation.

This does not mean that food will never be transported farther than this

distance, but there would have to be an important reason for moving it beyond

its economic range.

Prestige goods are items that have great value

and small size or items that can easily be transported long distances intact

and typically hold or increase their value in transit (e.g. spices, jade,

jewels or bullion). Prestige goods have a much larger spatial range than do

bulk goods because a small amount of such a good may be exchanged for a great

deal of food. This is why prestige goods networks are normally much larger than

bulk goods networks. A network does not usually end as long as there are people

with whom one might trade. Indeed most early trade was what is called

“down-the-line” trade in which goods were passed from group to group. For any

particular group the effective extent of its

trade network is that point beyond which nothing that happens will

affect the group of origin.

In order to bound

interaction networks we need to pick a place from which to start – the so-called

“place-centric approach.” If we go looking for actual breaks in interaction

networks we will usually not find them, because almost all groups of people

interact with their neighbors. But if we focus upon a single settlement, for

example the indigenous village of Onancock on the Eastern shore of the

Chesapeake Bay before the arrival of the Europeans in the 17th

century CE (near the boundary between what are now the states of Virginia and

Maryland in the United States), we can determine the spatial scale of the bulk

goods interaction network by finding out how far food moved to and from our

focal village.[8]

Food came to Onancock from some maximum distance. A bit beyond that were groups

that were trading food to groups that were directly sending food to Onancock.

If we allow two indirect jumps we are probably far enough from Onancock so that

no matter what happens (e.g. a food shortage or surplus), it would not have

affected the supply of food in Onancock. This outer limit of Onancock’s

indigenous bulk goods network probably included villages at the very southern

and northern ends of the Chesapeake Bay.

Onancock’s

prestige goods network was much larger because prestige goods move farther

distances. Indeed, copper that was in use by the indigenous peoples of the

Chesapeake may have come from as far away as Lake Superior. In between the size

of bulk goods networks (BGNs) and prestige goods networks (PGNs) are the

interaction networks in which polities make war and ally with one another.

These are called political-military networks (PMNs). PMNs

are interpolity (interstate) systems. In the case of the Chesapeake

world-system at the time of the arrival of the Europeans in the sixteenth

century Onancock was part of a district chiefdom in a PMN of multi-village

chiefdoms. Across the bay on the Western shore were at least two larger

polities, the Powhatan and the Conoy paramount chiefdoms (Rountree 1993). These

were core chiefdoms that were collecting tribute from a number of smaller

district chiefdoms. Onancock was part of an interchiefdom system of allying and

war-making polities. The boundaries of that network included some indirect

links, just as the trade network boundaries did. Thus the political-military

network (PMN) of which Onancock was the focal place extended to the Delaware

Bay in the north and into what is now the state of North Carolina to the

south. Information, like a prestige good, is light relative to its value.

Information may travel far along trade routes and beyond the range of goods.

Thus information networks (INs) are usually as large, or even larger, than

Prestige Goods nets (PGNs).

A general picture

of the spatial relationships between different kinds of interaction networks is

presented in Figure 4. The actual spatial scale of important interaction needs

to be determined for each world-system we study, but Figure 4 shows what is

generally the case – that BGNs (bulk goods nets) are smaller than PMNs

(political-military nets), and these are in turn smaller than PGNs (prestige

goods nets) and INs (information nets).

Figure 4: The Spatial Boundaries of World-Systems

Defined in the way that we have above,

world-systems have grown from small to large over the past twelve millennia as

polities, and interpolity systems have gotten larger, more complex and more

hierarchical.

This spatial growth of systems has involved the

expansion of some and the incorporation of some into others. The processes of

incorporation have occurred in several ways as systems distant from one another

have linked their interaction networks. Because interaction nets are of

different sizes, it is the largest ones that come into contact first. Thus

information and prestige goods link distant groups long before they participate

in the same political-military or bulk goods networks. The processes of

expansion and incorporation brought different groups of people together and

made the organization of larger and more hierarchical societies possible. It is

in this sense that globalization has been going on for thousands of years.

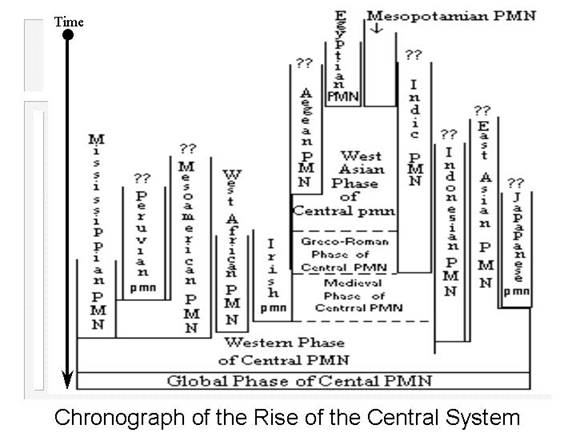

Using the conceptual apparatus for spatially

bounding world-systems outlined above we can construct spatio-temporal

chronographs for how the interaction networks of the human population changed

their spatial scales to eventuate in the single global political economy of

today. Figure 5 uses PMNs as the unit of analysis to show how a "Central"

PMN, composed of the merging of the Mesopotamian and Egyptian PMNs in about

1500 BCE, eventually incorporated all the other PMNs into itself.

Figure 5:

Chronograph of PMNs [adapted from Wilkinson (1987)]

Janet Lippman Abu-Lughod’s important 1989 study

of the multicentric Eurasian world-systems of the l3th century was a very

valuable and inspiring contribution. The most important theoretical issue

brought forth by Abu-Lughod’s study concerns differences between her approach

and that of Immanuel Wallerstein (2011a [1974]) regarding the spatial bounding

of world-systems (see Boles 2012). Abu-Lughod used interaction networks, mainly

long-distance trade, whereas Wallerstein uses a hierarchical regional division

of labor (see Wallerstein 1995). The upshot of this dispute is that both

conceptual approaches have proven to have productive uses for explaining the

causes of world-systems evolution. Wallerstein’s (2011a: Chapter 6) fascinating

analysis of why Russia was an “external arena” in the sixteenth century despite

that it was exporting the same goods to Europe as were being exported by

peripheralized Poland, is a fascinating case in favor of his method of

bounding. But Abu-Lughod’s focus on

trade, especially when combined with a consideration of geopolitical

interaction among polities (see Wilkinson 1987; Chase-Dunn and Jorgenson 2003),

is also a fruitful method that facilitates the comparative study of regional

world-systems small and large. Another

way in which Abu-Lughod helped to clear the way forward in world-systems

analysis was by rejecting the idea of the ancient hyperglobalists that there

has always been a single global (Earth-wide) system (ala Frank and Gills

1994; Modelski 2003 and Lenski 2005). She agreed with Wallerstein that as we go

back in time there were multiple regional whole systems that should be studied

separately and compared. Things would be much simpler if it made sense to use

the whole Earth as the unit of analysis since the humans came out of Africa.

The ancient hyperglobalists are correct that there has been a single global

network for millennia because all human groups interact with their neighbors

and so they are indirectly connected with all others. But this ignores the

issue of the fall-off of interaction effects discussed above. Frank

and Gills (1994) contended that there had been a single global system since the

rise of cities and states in Mesopotamia, though later they admitted that the

Americas were largely disconnected from Afroeurasia before 1492 CE. But if we

read Frank and Gills as studying the important continuities of the Central PMN

and the Eurasian PGN, as discussed above, much of their analysis of

core/periphery relations is quite valuable. They also raised the important

issue of the evolution of modes of accumulation, claiming that their had been a

“capitalist-imperialist” mode in the Bronze Age with alternating periods in

which tribute-taking and market based profit-making had been predominant (see

also Eklhom and Friedman 1982). This debate is far from over.

World-system Cycles: Rise-and-Fall and Pulsations

Comparative

research reveals that all world-systems exhibit cyclical processes of change.

There are two major cyclical phenomena: the rise and fall of large

polities, and pulsations in the spatial extent and intensity of trade

networks. "Rise and fall" corresponds to changes in the degree

of centralization of political/military power in a set of polities – an

“international” system. It is a question of the relative distribution of power across a set of interacting polities.

All world-systems

in which there are hierarchical polities experience a cycle in which relatively

larger polities grow in power and size and then decline. This applies to

interchiefdom systems as well as interstate systems, to systems composed of

empires, and to the modern rise and fall of hegemonic core powers (e.g. Britain

and the United States). Though very egalitarian and small scale systems such as

the sedentary foragers of Northern California do not display a cycle of rise

and fall, they do experience exchange network pulsations (Chase-Dunn and Mann,

1998:140-141).

All systems,

including even very small and egalitarian ones, exhibit cyclical expansions and

contractions in the spatial extent and intensity of exchange networks. We call

this sequence of trade expansion and contraction pulsation. Different

kinds of trade (especially bulk goods trade vs. prestige goods trade) usually

have different spatial scales. In the modern global system large trade networks

cannot get spatially larger because they are already global in extent. But they can get denser and more intense

relative to smaller networks of exchange. A good part of what has been called

globalization is simply the intensification of larger interaction networks

relative to the intensity of smaller ones. This kind of integration is often

understood to be an upward trend that has attained its greatest peak in recent

decades of so-called global capitalism. But research on changes in the level of

trade and investment globalization shows that there have been two and ½ recent

waves of integration, one in the last half of the nineteenth century and the

most recent since World War II (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000).

The simplest

hypothesis regarding the temporal relationships between rise-and-fall and

pulsation is that they occur in tandem. Whether or not this is so, and how it

might differ in distinct types of world-systems, is a set of problems that are

amenable to empirical research.

Chase-Dunn and

Hall (1997) have contended that the causal processes of rise and fall differ

depending on the predominant mode of accumulation. One big difference between

the rise and fall of empires and the rise and fall of modern hegemons is in the

degree of centralization achieved within the core. Tributary systems alternate

back and forth between a structure of multiple and competing core states on the

one hand and core-wide (or nearly core-wide) empires on the other. The modern

interstate system experiences the rise and fall of hegemons, but the efforts

that have been made to take over the other core states to form a core-wide

empire have always failed in the modern system. This is the case mainly because

modern hegemons are pursuing a capitalist, rather than a tributary form of

accumulation.

Analogously, rise

and fall works somewhat differently in interchiefdom systems because the

institutions that facilitate the extraction of resources from distant groups

are less fully developed in chiefdom systems. David G. Anderson's (1994) study

of the rise and fall of Mississippian chiefdoms in the Savannah River valley

provides an excellent and comprehensive review of the anthropological and

sociological literature about what Anderson calls "cycling" -- the

processes by which a chiefly polity extended control over adjacent chiefdoms

and erected a two-tiered hierarchy of administration over the tops of local

communities. At a later point these regionally centralized chiefly polities

disintegrated back toward a system of smaller and less hierarchical polities.

Chiefs relied

more completely on hierarchical kinship relations, control of ritual

hierarchies, and control of prestige goods imports than do the rulers of true

states. These chiefly techniques of power are all highly dependent on normative

integration and ideological consensus. States developed specialized

organizations for extracting resources that chiefdoms lacked -- standing armies

and bureaucracies. And states and empires in the tributary world-systems were

more dependent on the projection of armed force over great distances than

modern hegemonic core states have been. The development of commodity production

and mechanisms of financial control, as well as further development of

bureaucratic techniques of power, have allowed modern hegemons to extract resources

from far-away places with much less overhead cost.

The development

of techniques of power has made core/periphery relations ever more important

for competition among core powers and has altered the way in which the

rise-and-fall process works in other respects. Chase-Dunn and Hall

(1997:Chapter 6) argued that population growth in interaction with the

environment, and changes in productive technology and social structure produce

sociocultural evolution that is marked by cycles and periodic jumps. This is

because each world-system oscillates around a central tendency due both to

internal instabilities and environmental fluctuations. Occasionally, on one of

the upswings, people solve systemic problems in a new way that allows

substantial expansion. We want to explain expansions, evolutionary changes in

systemic logic (Chase-Dunn 2014), and collapses. That is the point of comparing

world-systems.

The

multiscalar regional method of bounding world-systems as nested interaction

networks outlined above is complementary with a multiscalar temporal analysis

of the kind suggested by Fernand Braudel’s (1972,1984) work. Temporal depth,

the longue duree, needs to be combined with analyses of short-run and

middle-run processes to fully understand social change.

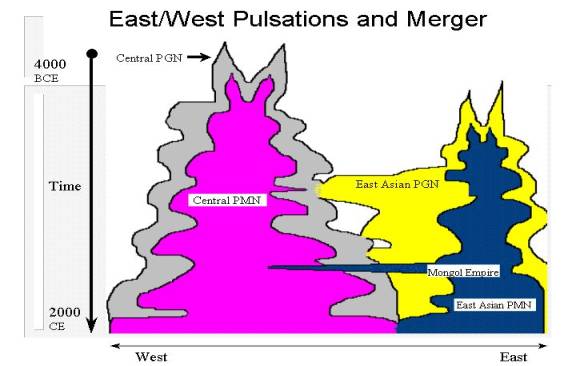

Figure

6 below depicts the coming together of the East Asian and the West

Asian/Mediterranean systems. Both the PGNs and the PMNs are shown, as are the

pulsations and rise and fall sequences. The PGNs linked intermittently and then

joined. The Mongol conquerors linked the PMNs briefly in the thirteenth

century, but the Eastern and Western PMNs were not permanently linked until the

Europeans and Euro-Americans established Asian treaty ports in the nineteenth

century.

Figure 6: East/West Pulsations and Merger

Semiperipheral Development

The semiperiphery

concept was originally developed to study the modern world-system (Wallerstein

2011). But it too has been expanded for use in comparing different kinds of

systems. For Wallerstein the

semiperiphery is a middle stratum in the global hierarchy that helps keep the

system from breaking down due to polarization. But Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997)

claimed that semiperipheral societies have often been agents of change in both

the modern and earlier systems.

Hub theories of

innovation have been popular among world historians (e.g. McNeill and McNeill

2003; Christian 2004) and human ecologists (Hawley 1950). These hold that new

ideas and institutions emerge in central settlements where information

crossroads are located. The mixing and recombination of ideas and information

facilitates the emergence of new formulations. The hub theory is undoubtedly

partly correct, but it cannot explain some of the long-term patterns of human

sociocultural evolution, because if a large information cross-road was able to

out compete all contenders then the original information hub would still be the

center of the world. But that is not the case. We know that cities and states

first emerged in Mesopotamia around 5000 years ago. Mesopotamia is now Iraq.

Mesopotamia had 100% of the world’s largest settlements and the most powerful

polities on Earth in the Early Bronze Age. Now it has none of these. All of the

regional world-systems have undergone a process of uneven development in which

the old centers were replaced by new centers out on the edge.[9]

Chase-Dunn and

Hall (1997) asserted it had most often been polities out on the edge (in

semiperipheral regions) that had transformed the institutional structures and

accomplished the upward sweeps. This hypothesis is part of a larger claim that

is people in semiperipheral locations that usually play the transformative

roles that cause the emergence of greater sociocultural complexity and

hierarchy within world-systems. This hypothesis of semiperipheral development

is an important justification supporting the claim that world-systems rather

than single polities are the right unit of analysis for explaining human

socio-cultural evolution.

The hub theory of innovation does not well account

for the spatially uneven nature of sociocultural evolution. The cutting edges

of power and scale move. Polities out on the edge that are able to conquer

large territories or to rewire networks and to expand their spatial scale often

transcend old centers. This is due to two things. Competitive success is not

only about where new and adaptive technologies, ideas and organizational forms

are created. It is also importantly about which polities invest in and

implement these innovations. Innovations do often emerge outside of large

networks nodes. New weapons, military techniques and religions often emerge

from peripheral or semiperipheral regions (e.g. Hamalainen 2008). But it is

implementation rather than innovation that is the more important aspect that

explains the phenomenon of semiperipheral development. Polities in semiperipheral

locations often implement innovations that originated elsewhere. This is an important part of the explanation

of semiperipheral development.

Semiperipheral

development has taken various forms: semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms,

semiperipheral marcher states, semiperipheral capitalist city-states, the

peripheral and then semiperipheral position of Europe in the larger

Afroeurasian PGN, modern semiperipheral nation-states that have risen to

hegemony (the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States), and

contemporary peoples in semiperipheral locations that are engaging in, and

supporting, novel and potentially transformative movements.

There

are several possible processes that might account for the phenomenon of

semiperipheral development. Randall Collins (1981) has

argued that the phenomenon of marcher states conquering other states to make

larger empires is largely due to the “marcher state advantage.” Being out on

the edge of a core region of competing states allows more maneuverability

because it is not necessary to defend the rear. This geopolitical advantage

allows military resources to be concentrated on vulnerable neighbors. Peter

Turchin (2003) has argued that the relevant process is one in which group

solidarity is enhanced by being on a “metaethnic frontier” in which the clash

of contending cultures produces strong cohesion and cooperation within a

frontier society, allowing it to perform great feats. Carroll Quigley (1961)

distilled a somewhat similar theory from the works of Arnold Toynbee. Another

factor affecting within-polity solidarity is the different degrees of internal

stratification usually found in premodern world-systems between the core and

the semiperiphery. Core polities develop old, crusty and bloated elites who

rely on mercenaries and “foreigners” as subalterns, while semiperipheral

leaders are often charismatic heroes who are strongly supported by their

soldiers and citizens. Less stratification often facilitates greater group

solidarity. And this may be an important part of the semiperipheral advantage.

But Quigley also suggested another way in which the peoples of semiperipheral

regions might be motivated to take risks with new ideas, technologies and

strategies. Semiperipheral polities are often located in ecologically marginal

regions that have poor soil and little water or other geographical

disadvantages. Patrick Kirch relies on this idea of ecological marginality in

his depiction of the process by which semiperipheral marcher chiefs often are

the conquerors that unify island-wide paramount chiefdoms in the Pacific (Kirch

1984). It is quite possible that all these features combine to produce what

Alexander Gershenkron (1962) called “the advantages of backwardness” that allow

some semiperipheral polities to transform and to dominate their world-systems.

As

we have already said, the hypothesis of semiperipheral development claims that

many of those innovations that make it possible for world-systems to get

larger, more complex and more hierarchical are created by peoples in

semiperipheral locations and that some semiperipheral polities invest in, and

implement, transformative innovations that are borrowed from core or peripheral

societies.[10]

Some semiperipheral polities are involved in processes of rapid internal class

formation and state formation and they do not have large investments in, and

commitments to, doing things the way they have been done in older core

polities. They do not have institutional or infrastructural sunk costs. So they

are freer to reinvent themselves, to implement new institutions and to

experiment with new technologies.

There are several different important kinds of semiperipheries, and they not only transform systems but they also often take over and become the new hegemonic core polity. We have already mentioned semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms. The societies that conquered and unified a number of smaller chiefdoms into larger paramount chiefdoms were usually from semiperipheral locations. Peripheral peoples did not usually have the institutional and material resources that would allow them to implement new technologies or organizational forms or to take over older core regions, though there were also some well-known “peripheral marcher polities” (e.g. the vast steppe confederacy organized by Genghis Khan that produced the Mongol Empire). It was mainly in the semiperiphery that core and peripheral social characteristics were more likely to be recombined in new ways and where enough resources were available to allow significant investment in transformative instruments.

Much

better known than semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms is the phenomenon of

semiperipheral marcher states. Many of the largest empires were assembled by

conquerors who came from semiperipheral polities. Well-known examples are the Achaemenid

Persians, the Macedonians led by Phillip and Alexander, the Romans, the Islamic

Caliphates, the Ottomans, the Manchus and the Aztecs. (Alvarez et al

2013).

But

some semiperipheral peoples and polities transform institutions, but do not

take over the interpolity system of which they are a part. The semiperipheral capitalist city-states

operated on the edges of the tributary empires where they bought and sold goods

in widely separate locations, encouraging peoples near and far to produce

surpluses for trade. The Phoenician

cities (e.g. Byblos, Sidon, Tyre, Carthage, etc.), as well as Malacca, Venice,

Genoa and the German Hanse cities, spread commodification by producing manufactured

goods and trading them across great regions. Some cities even in the Bronze Age

(e.g. Dilmun and Assur of the Old Assyrian city-state) specialized in

long-distance trade. The semiperipheral capitalist city-states were agents of

the development of markets and the expansion of trade networks, and so they

helped to transform the world of the tributary empires without themselves

becoming new core powers.[11] These were the first capitalist states in which

state power was mainly used to facilitate profit making rather than the

extraction of taxes and tribute (Chase-Dunn et al 2013).

Philippe Beaujard

(2005:239) makes the point that core/periphery relations often involve

co-evolution. Even when exploitation and domination of the non-core by the core

occurs, polities in both zones are altered and co-evolve. In many systems in

Afroeurasia and the Americas interactions between hunter-gatherers and farmes

led to the emergence of polities that specialized in pastoralism. (Lattimore

1940; Barfield 1989; Honeychurch 2013; Hamalainen 2008). Some of the pastoralists

were exploited and dominated by core polities but others turned the tables and

were able to extract resources from agrarian states.

Indicators of Semiperipherality

The Settlements

and Polities (EmpCit) Research Working Group at the Institute for Research on

World-Systems at the University of California-Riverside uses quantitative

estimates of the population sizes of large cities and of the territorial sizes

of polities to identify instances of “upsweeps” in which city and polity sizes

significantly increased in scale ((Inoue et al 2012; Inoue et al

2015). We also determine how many of the urban and polity upsweeps so

identified were due to the actions of semiperipheral or peripheral marcher

states. This task requires greater

specificity about what is meant by semiperipherality. The core/periphery

distinction is a relational concept. In other words, what

semiperipherality is depends on the larger context in which it occurs – the

nature of the polities that are interacting with one another and the nature of

their interactions. The most general definition of the semiperiphery is: an intermediate

location in an interpolity core/periphery structure. The minimal definition of

core/periphery relations, as mentioned above, is that polities with different

degrees of population density and internal hierarchy and complexity are

interacting with one another. This is what we have called “core/periphery

differentiation.” We are looking for evidence that a polity that conquered

other polities and was responsible for an upward sweep was semiperipheral

relative to the other polities it was interacting with before it started on the

road to conquest.

The alternatives

to semiperipherality are coreness and peripherality. Core

polities are usually older, more stratified, have bigger settlements, and they

have had the accoutrements of civilization, such as writing, longer. Peripheral

societies are nomadic hunter-gatherers or pastoralists, hill people, or desert

people. If they are sedentary, their villages are small relative to the

settlements of those with which they are interacting. We have already noted that some conquest

empires were formed by peripheral marcher states. Other polity upsweeps were

caused by regime changes in old core states or by older civilizational cultures

that made a comeback. David Wilkinson’s (1991) survey of the core, peripheral and

semiperipheral zones of thirteen interpolity systems, is helpful in suggesting

criteria for designating these zones, but Wilkinson did not address the

question we are asking here: were the polities that produced empire and urban

upsweeps semiperipheral before they did this?

We use four main

empirical indicators to make such determinations:

キ

the geographical location of the polity relative to other

polities that have greater or lesser amounts of population density. Is it out

on the edge of a region of core polities?, and

キ

the relative level of development: population density, which

is usually indicated by the sizes of settlements, the relative degree of

complexity and hierarchy, the mode of production: e.g foraging, pastoralism,

nomadism vs. sedentism, horticulture vs. agriculture, the size of irrigation

systems, etc. Hunter-gatherers or pastoralists are usually peripheral to more

sedentary agriculturalists; and

キ

the recency of the adoption of sedentism, agriculture, class formation

and state formation, and

キ

relative ecological marginality.

The Aztecs

(Mexica-Culhua) are a proto-typical example of a semiperipheral marcher state.

They were nomadic hunter-gatherers who migrated into the Valley of Mexico and

settled on an uninhabited island in a lake. There had already been large states

and empires in the Valley of Mexico for centuries. The Aztecs hired themselves

out to older core states as mercenary soldiers, developed a class distinction

between nobles and commoners and claimed to have been descended from the

Toltecs, an earlier empire. Then they began conquering the older core states in

the Valley of Mexico, strategically picking first on weak and unpopular ones

until they had gathered enough resources to “roll up the system.” The Aztec

story has most of the elements that we are using to examine our upsweep cases:

marginal geographical location, recency of sedentism, class formation and state

formation.

Another

indicator of semiperipheral location is relative environmental desirability.

Core societies usually hold the best locations in terms of soil and water.

Non-core polities hold ecologically marginal territories. The semiperipheral

marcher chiefdoms of the Pacific Islands were typically from the dry side of

the island where land was steeper, rainfall was less frequent and soil was

thinner.[12]

Another issue is “semiperipheral to what?” A polity may have different relationships with other polities in the same interpolity network. For example, Macedonia had one kind relationship with the other Greek states, and a different kind of relationship with the Persian Empire. Semiperipherality is relative to the system as a whole, but may also be affected by important differences between other states in a system and by the existence of different kinds of relations with those other states.

Philippe

Beaujard (2005) makes good use of the semiperiphery concept in his study of the

emergence of world-systems in the Indian Ocean. Beaujard (2005:442) mentions

instances in which the emergence of regional settlements that connected

hinterlands with core areas were facilitated by the presence of merchants and

religious elites who were migrants from core regions. Beuajard’s study of the emergence of unequal

exchange between the coastal Swahili cities and the interior of the East

African mainland notes that immigrants from the Arabian core helped to form

commercial ties, intermarried with local elites, and converted locals to Islam,

thereby promoting a process of class-formation that led to the emergence of a

semiperipheral polities along the coast. Beaujard also affirms our point that

innovations sometimes occur in semiperipheral polities (445).

Results from Studies of Scale Changes of Polities and

Settlements

The EmpCit

studies use estimates of city sizes and the territorial sizes of empires to

examine and compare different regional interaction systems (e.g. Chase-Dunn,

Manning and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and Manning 2002; Inoue et al 2012;

Inoue et al 2015). We identify

those instances in which the scale of polities and settlements has greatly

increased. These are termed “upsweeps” (Inoue et al 2012; Inoue et al

2015). We have also identified

downsweeps and system-wide collapses in which the largest polities or

settlements declined below the level of the previous low point and stayed down

for more than one typical cycle. We found that, while the decline of individual

cities and empires is part of the normal cycle of rise and fall, there were few

system-wide collapses in which a downsweep was not followed rather soon by a

recovery.

We also found a greater rate of urban cycles in

the Western (Central) PMN than in the East Asian PMN, which supports the usual

notion that the West was less stable than the East. And our finding that the

Central PMN experienced two urban collapses while the Eastern PMN experienced

downsweeps but not collapses supports the idea of greater stability in the

East. We also found that nine of the eighteen urban upsweeps were produced by

semiperipheral development and eight directly followed, and were caused by,

upsweeps in the territorial sizes of polities.

We also identified twenty-two upsweeps of the

largest polities in four world regions and in the expanding Central PMN since

the Bronze Age and we examined these to determine whether or not they were the

result of semiperipheral marcher conquests (Álvarez et al 2013).[13] We found that over half of

the polity upsweeps were produced by marcher states from the semiperiphery (10)

or from the periphery (3). This means that the hypothesis of semiperipheral

development does not explain everything about the events in which polity sizes

significantly increased in geographical scale, but also that the phenomenon of

semiperipheral development can not be ignored in any explanation of the

long-term trend in the rise of polity sizes.

Conclusions

World-system

scholars contend that leaving out the core/periphery dimension or treating the

periphery as inert are grave mistakes, not only for reasons of completeness,

but also because the ability of core elites and their polities to exploit

peripheral resources and labor has been, and continues to be, a major factor in

deciding the winners of the competition among core contenders. The resistance

to exploitation and domination mounted by non-core peoples has played a

powerful role in shaping the historical development of world-systems since the

Bronze Age. Thus sociocultural development

cannot be properly understood without attention to the core/periphery hierarchy

and world-systems are a fundamental unit of analysis for explaining long-term

sociocultural evolution.

This said, the

world-systems theoretical research program is yet in its infancy. Alternatives

to the method proposed above for spatially bounding world-systems need to be

operationalized and pitted against one another to see which methods of spatial

bounding are more powerful for explaining the events that have caused the

long-term trends toward greater complexity, integration and hierarchy. And the

project to accurately estimate the sizes of settlements and polities needs

further work. Temporal resolution needs improvement, especially in the

Americas, in order to make it possible to identify upsweeps in the way that has

been done in Afroeurasia. More settlement and polity sizes will make it

possible to study changes in size distributions within regions and to examine

claims about the emergence of synchrony between regions. Geocoded data on

climate change, warfare, polity boundaries and trade networks will make it

possible to examine the causes of “normal” upswings and downswings as well as

the less frequent upsweeps and downsweeps. The scientific study of the

development of world-systems will have important implications for issues such

as human responses to climate change, ecological degradation, population

density, the changing nature of the global city system, the rise and fall of

hegemonic core powers, transitions from unipolar to multipolar power

situations, as well as resilience and systemic collapse.

References

Abu-Lughod, Janet

L. 1989 Before European Hegemony: The

World-System, AD l250-l350. New

York: Oxford

University Press.

Álvarez, Alexis. E.N.

Anderson, Elisse Basmajian, Hiroko Inoue, Christian Jaworski, Alina

Khan, Kirk Lawrence,

Andrew Owen, Anthony Roberts, Panu Suppatkul and

Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2013 “Comparing

World-Systems: Empire Upsweeps and

Non-core marcher

states Since the Bronze Age” Presented at the annual meeting of the American

Sociological Association, New York, August

Anderson, David G. 1994 The Savannah River Chiefdoms. Tuscaloosa:

University of Alabama Press.

Barfield, Thomas

J. 1989.

The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic

Empires and China. Cambridge, MA:

Basil Blackwell.

Beaujard, Philippe. 2005 The Indian Ocean in Eurasian and African

World-Systems Before

the Sixteenth

Century・ Journal of World History 16,4:411-465.

_______________ 2009 Les mondes de l’océan Indien Tome I: De

la formation de l’État au premier système-monde Afro-Eurasien (4e millénaire

av. J.-C. – 6e siècle apr. J.-C.). Paris: Armand Colin.

_______________2010. “From Three possible Iron-Age World-Systems

to a Single Afro-

Eurasian

World-System.”Journal of World History 21:1(March):1-43.

_______________ 2112 Les

mondes de l’océan Indien Tome II:

L’océan Indien, au coeur des

globalisations de

l’ancien Monde du 7e au 15e siècle. Paris: Armand Colin

Bentley, Jerry H. 1993 Old World

Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times.

Oxford: Oxford University Press

Boles, Elson E. 2012 “Assessing the debate between Abu-Lughod and

Wallerstein over the thirteenth-century origins of the modern world-syste”・Pp. 21-29 in S. J. Babones and C. Chase-Dunn (eds.) Routledge

Handbook of World-Systems Analysis. New York: Routledge.

Bond, Patrick 2013 “Subimperialism as

lubricant of neoliberalism: South African ‘deputy sheriff’ duty within

BRICS” Paper to be presented at the Santa Barbara Global Studies Conference

session on "Rising Powers: Reproduction or Transformation?"

February 22 – 23, 2013

Braudel,

Fernand 1972 The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of

Philip II. New

York: Harper and Row, 2 Volumes.

_____________. 1984. The

Perspective of the World, Volume 3 of Civilization and Capitalism. Berkeley:

University

of California Press.

Chapman, Anne C. 1957 “Port of trade enclaves in Aztec and Maya

civilizations” Pp. 114-153 in Karl Polanyi, Conrad

M. Arensberg and

Harry W. Pearson, Trade and Markets in the Early Empires. Chicago: Henry Regnery.

Chase-Dunn, C. 1998 Global

Formation: Structures of the World- Economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman

and Littlefield.

Chase-Dunn,C. 1999

"Globalization: A World-Systems Perspective" Journal of

World-Systems Research, Vol

V, Number 2, Pp. 165-185. http://www.jwsr.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Chase-Dunn-v5n2.pdf

____________ 2006 “Globalization: A world-Systems perspective” Pp.

79-108 in C. Chase-Dunn and S. J. Babones (eds.) Global Social Change

Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

_____________ and Elena Ermolaeva 1994 “The Ancient Hawaiian World-System” IROWS Working

Paper #4, http://www.irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows4.txt

_____________ and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Boulder, CO: Westview.

_____________ Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 “Trade

globalization since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system” American

Sociological Review 65,1:77-95

_____________ and Susan Manning, 2002 "City systems and world-systems: four millennia of city growth and

decline," Cross-Cultural Research 36, 4:

379-398 (November

______________Susan Manning and Thomas D. Hall 2000 “Rise and fall:

East-West synchronicity and Indic

exceptionalism reexamined,” Social Science History. 24,4:727-

754.

_____________ and Andrew K.

Jorgenson, “Regions and Interaction Networks: an

Institutional

materialist perspective,” 2003 International Journal of Comparative

Sociology

44,1:433-450.

______________ and Bruce Lerro 2014 Social Change: Globalization

from the Stone Age to the

Present. Boulder, CO: Paradigm

______________ and Kelly M. Mann

1998 The Wintu and Their Neighbors: A Very Small World-System in

Northern California. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

______________ Eugene N. Anderson, Hiroko Inoue, Alexis Álvarez,

Lulin Bao, Rebecca Álvarez, Alina Khan and Christian Jaworski 2013

“Semiperipheral Capitalist City-States and the Commodification of Wealth, Land,

and Labor Since the Bronze Age” IROWS

Working Paper # #79 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows79/irows79.htm

Christian, David 2004 Maps of Time. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Collins, Randall

1981 “Long term social change and the territorial power of states,” Pp. 71-106 in R. Collins (ed.) Sociology

Since Midcentury. New York: Academic Press.

Ekholm, Kasja and Jonathan Friedman 1982 "'Capital' Imperialism and Exploitation

in the Ancient World-systems." Review

6:1(Summer):87-110. (Originally

published pp. 61-76 in History and Underdevelopment, (1980) edited by L.

Blusse, H. L. Wesseling and G. D. Winius. Center for the History of European

Expansion, Leyden University.

Frank, Andre Gunder and Barry Gills 1994 The World System: 500 or

5000 Years? London: Routledge

Gershenkron, Alexander.

1962. Economic Backwardness in

Historical Perspective. Cambridge:

Harvard University Press.

Hamalainen, Pekka 2008 The Comanche Empire. New Haven: Yale

University Press.

Hawley, Amos. 1950. Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure.

New York: Ronald

Press Co.

Honeychurch, William 2013 “The Nomad as State Builder: Historical

Theory and Material Evidence from

Mongolia” Journal

of World Prehistory 26:283–321

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Kirk Lawrence, Anthony Roberts, Eugene

N Anderson and

Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2012 “Polity scale shifts in world-systems since the Bronze Age: A

comparative

inventory of upsweeps and collapses” International Journal of Comparative

Sociology

http://cos.sagepub.com/content/53/3/210.full.pdf+html

____________, Alexis

Álvarez, Eugene N. Anderson, Andrew Owen, Rebecca Álvarez,

Kirk Lawrence and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2015 “Urban scale shifts since the

Bronze Age:

upsweeps, collapses and semiperipheral development” Social Science

History Volume 39 number 2, Summer

Jennings, Justin 2010 Globalizations and the Ancient World.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kirch, Patrick V. 1984 The Evolution of Polynesian Chiefdoms.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lattimore,

Owen. 1940. Inner Asian Frontiers of China. New York:

American Geographical Society, republished 1951, 2nd ed. Boston: Beacon Press.

Lenski, Gerhard 2005 Ecological-Evolutionary Theory. Boulder,

CO: Paradigm Publishers

Mann, Michael 2013 The Sources of Social Power, Volume 4:

Globalizations, 1945-2011. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McNeill, William

H. 1963 The Rise of the West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McNeill, John R. and William H. McNeill 2003 The Human Web.

New York: Norton.

Meyer, John W. 2009 World Society. Edited by Georg Krukcken

and Gili S. Drori. New

York: Oxford

University Press.

Modelski, George 2003 World

Cities: -3000 to 2000. Washington,

DC: FAROS2000.

Quigley, Carroll 1961 The Evolution of Civilizations. Indianapolis: Liberty

Press.

Rountree, Helen C. 1993 (ed.) Powhatan

Foreign Relations, 1500-1722 Charlottesville: University of

Virginia

Press.

Sabloff, Jeremy and William J. Rathje 1975 A

Study of Changing Pre-Columbian Commercial Systems.

Cambridge: Peabody

Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Harvard University.

Shannon, Thomas Richard 1992 An Introduction

to the World-System Perspective. Boulder, CO:

Westview

Press.

Turchin, Peter 2003 Historical

Dynamics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

___________ 2011.

“Warfare and the Evolution of Social Complexity: a Multilevel Selection

Approach”

Structure and Dynamics Vol. 4, Iss. 3, Article 2:1 -37

Wallerstein, Immanuel 1984 “The three instances of hegemony in the

history of the capitalist world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski

(ed.) Current Issues and Research in Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology and Social

Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

__________________1995 “Hold the tiller firm: on method and the unit

of analysis” Pp. 239-247 in Stephen K. Sanderson (ed.) Civilizations and

World-Systems. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

__________________2011a [1974] The Modern World-System I:

Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the

Sixteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

_______________ 2011b The Modern World-System IV: Centrist

Liberalism Triumphant, 1789-1914 Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wilkinson, David. 1987 "Central civilization" Comparative

Civilizations Review 17:31-59 (Fall).

________ 1991 “Core, peripheries and civilizations,”Pp. 113-166 in C.

Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.) Core/Periphery Relations in Precapitalist

Worlds. Boulder, CO: Westview Press http://www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/books/c-p/chap4.htm