The Evolution of

Economic Institutions:

City-states and forms of imperialism since the Bronze Age

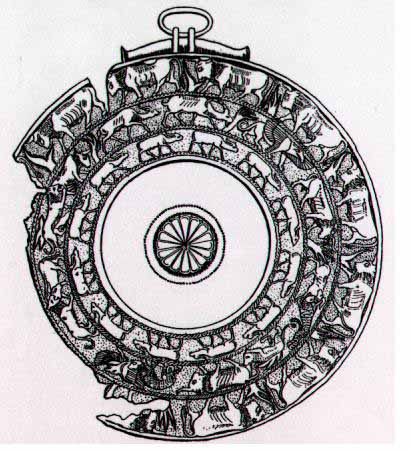

Circular seal from Dilmun

Christopher

Chase-Dunn, E. N. Anderson,

Hiroko Inoue and Alexis Álvarez

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

![]()

This is IROWS

Working Paper #79 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows79/irows79.htm

To be presented at the

International Studies Association 2015 annual meeting, New Orleans, Friday

February 20, 4 pm, Panel title: “Imperialism in World Regions”

Abstract:

This paper is part of a larger project that studies the evolution of

exchange and exploitation within an anthropological framework that includes

small-scale polities and interpolity systems composed

of sedentary foragers as well as states and empires.[1] The

cases surveyed are considered for their importance in understanding the

evolution of economic and political institutions and modes of

accumulation. The evolutionary

world-systems perspective sees semiperipheral

development as an important cause of human sociocultural evolution. In this paper we discuss the literature on the evolution of economic

institutions in prehistory and consider the roles that semiperipheral

trading polities have played in sociocultural evolution since the emergence of

cities and states in the early Bronze Age. We trace the emergence and spread of

Bronze Age land-based and maritime city-states that specialized in trade as

progenitors and promoters of commodification. We examine how city-states that

were controlled by those who gathered their wealth mainly from trade rather

than taxation may have acted as agents of the expansion and intensification of

commercial trade networks and how a concentration of such city-states in parts

of Europe, and the relative weakness of tributary empires after the decline of

Rome, led to the emergent predominance of capitalism as a logic of social

reproduction and development. We also examine the extent to which thallasocratic city-states pioneered a new form of colonial

imperialism that eventually replaced the older pattern in which states had

conquered their adjacent neighbors to form empires.

Semiperipheral Polities and

the Commodification of Wealth, Land, Labor and Goods Since the Bronze Age

Our theoretical perspective is the

institutional materialist evolutionary world-systems approach.[2]

This perspective focuses on the ways that humans have organized social

production and distribution, and how economic, political, and religious

institutions have evolved in systems of interacting polities (world-systems)

since the Paleolithic Age. We employ an underlying model in which population

pressures and interpolity competition have always

been, and still remain, important causes of social change, while the systemic

logics of social reproduction and growth have gone through qualitative

transformations (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 6). Thus we are both continuationists and transformationists.

The topic of the evolution of

economic and political institutions over the long run of human sociocultural

development is far from finding consensus among social scientists. A heated

debate about how to best characterize the continuities and transformations

since the age when all humans were nomadic foragers emerged with modern social

science and is quite as contentious now as it has always been despite huge

advances in our ability to obtain scientific evidence about human life in the

past. Part of the reason for continued controversy is that it is difficult to

determine the nature of sociocultural institutions with archaeological evidence

alone. And another main factor is that characterizations of the human past have

implications for current debates about human nature and what is possible for

the human future. In the past this debate was described as between “formalists”

who contend that all human societies share a common economic logic based on

individual decision-making and competitive bargaining, whereas “substantivists” claim that economic actions are always

embedded within normative and institutional orders and that there have been

qualitative transformations in the logic of social integration in the

prehistory and history of the emergence of sociocultural complexity.

Recently

a significant and articulate group of archaeologists have remounted the attack

on Karl Polanyi’s substantivist characterization of

the development of qualitatively different modes of socioeconomic integration.

Polanyi described a developmental sequence of institutional arrangements that

were said to characterize the economies of whole societies. His main forms of

economic integration were reciprocity, redistribution and market exchange. His most important contention was that market

trade is not a natural and universal logic of social interaction but is rather

an institutional invention with a history that can be studied. Polanyi claimed

that land, labor and goods are not naturally exchanged as commodities but they

become commercialized and monetized in

the development of human societies.[3]

This is not necessarily a smooth or continuous process. There are waves of

commodification and decommodification. Some things

are more difficult to commodify than other others. It

is easier for standardized goods to be treated as commodities or money than it

is for labor or land to be commodified. And so the

prehistoric and historical processes of commodification of goods, labor and

land were uneven across time and space. And though commodification spread and

deepened, no societies, even our own, commodify all human interactions. Normatively regulated sharing and reciprocity

and politically regulated taxation and tribute continue to exist, but they

exist in a context in which the market economy and commodified

property and labor are the predominant forms.[4]

Polanyi’s

ideas were employed by a whole generation of economic anthropologists as well

as world historians and sociologists, and this entire corpus has been attacked

as having used ideological blinders to force human societies into theoretical

categories that obscure reality. A succinct expression of this critique is

contained in a recent article in the Annual Review of Anthropology by

archaeologists Gary Feinman and Christopher Garraty (2010). This article summarizes the main points

contained in a collection of essays edited by Garraty

and Barbara L. Stark (2010; see also Blanton and Fargher 2012). The

archaeologists who have put together this most recent assault on Polanyi are mainly

Americanists who have themselves done excavations and surface surveys in North,

Central and South America. They make a convincing case that market institutions

and the use of money were important institutions in the political economies

that emerged in Mesoamerica and they note that this aspect of Mesoamerican

societies has been somewhat ignored in the social science literature.[5]

The Feinman and Garraty article contains a helpful overview of the problems

associated with the identification of market systems using only archaeological

evidence. We know that Mesoamerican civilization made extensive use of markets

primarily based on ethnohistoric accounts, not

archaeological evidence. Feinman and Nicholas (2010) propose a multiscalar

approach to the problem of identifying market systems with archaeological

evidence from the valley of Oaxaca and Stark and Garraty

(2010) also present an overview of the challenges and possible solutions for

the problem of identifying marketplace exchange when restricted to archaeological

evidence.

It is clear that Polanyi was wrong about

particular cases in which he believed that markets were absent but later

evidence emerged showing that they were present. The most famous of these

instances is not mentioned in the Feinman and Garraty article but came to light in a previous round of

attacks on Polanyi in the 1970’s. Polanyi had asserted that the recently

discovered Kultepe tablets showed that a colonial

enclave of Assur in the town of Kanesh in

Cappadocia, showed that the colonists were operating as political agents of

non-market “administered trade.” In

Polanyi’s theoretical scheme early states engaged in non-market exchange

(gift-giving or tribute) that employed political agents of the king to carry

out the transactions. This is called “administered trade.”

Later research based on a more complete reading

of the Kultepe tablets confirmed that the Old

Assyrians were true merchants calculating profits on their own accounts, not

agents of the Assyrian state (Curtin 1984; and see page 8 below). Polanyi and his students were also wrong

about Mesoamerica, though they were not wrong about the Andes. The problem is that some mistakes in the

identification of cases is not enough to completely discredit a theory.

Polanyi’s contention that most small-scale societies are based on mainly on

reciprocity and sharing, especially as elaborated by Marshall Sahlins (1972), and that these institutional forms of

exchange predate the emergence of proto-money, tribute-gathering and commodified market exchange remains accurate even if he was

wrong about the timing or location of

the emergence of commodified forms. The article by Feinman and Garraty does not

address this issue. But the extreme version of the “formalist” theoretical

perspective claims that all human societies are based on the rational actor

model and a bargaining form of exchange that is similar to market trade. It remains quite plausible that there was

indeed a transition from reciprocity/sharing to redistribution and then later

to market exchange. But these

transitions may have taken place at an earlier and smaller level of complexity

than Polanyi claimed. If this is so it

means that the ability to identify commodified forms

of wealth, goods, property and exchange using archaeological evidence is more

important that has been thought and so the efforts to do this contained in the Garraty and Stark (2010) are to be applauded. One problem

with the existing efforts to develop purely archaeological evidence for market

exchange is that they almost exclusively focus on the comparison between market

exchange and redistributive integration which is presumed to be less efficient

because it requires bringing goods to a central location and then

redistributing them. Little attention has been given to the problem of

distinguishing market exchange (and redistribution) from sharing/reciprocity,

but this problem must be solved if we are to trace the important prehistory of

commodification stateless societies. [6]

Our approach, elaborated below and in Chase-Dunn

et al (2013), contends that early forms of commodification emerged within

small-scale systems based on reciprocity (Chase-Dunn et al 2013) and then slowly

and unevenly within some of the tributary empires, and that city-states

specializing in trade developed institutions and organizational forms and

technologies that facilitated expanded and deepened commodification.

A related

controversy has reemerged over the question of the emergence of capitalism.

Some world-systems theorists claimed that a “capital-imperialist” mode of

accumulation that oscillated between state-organized and market-organized

phases arose in the Bronze Age (Ekholm and Friedman

1982) and that there was no transition

to capitalism that occurred with the rise of European hegemony (Frank and Gills

1994). This perspective does not claim

to shed light on an earlier period in which market institutions were emerging,

and neither does it address the issue of the relative predominance of commodification.

It implies that capital-imperialism arose full-blown in the early states of the

Bronze Age and that there has been no upward trend toward increasing

commodification since then. Some of these same theorists (Frank and Gills) also

claim that there was a single Eurasian world system since the emergence of

early states in Mesopotamia, earning them the title of “ancient hyperglobalists” (Chase-Dunn, Inoue, Heimlich and Neal

2015).

Our

stylized model of the evolution of economic institutions

This

paper will focus mainly on the evolution of economic institutions and the roles

played by semiperipheral polities in the long-term

commodification of goods, wealth, labor and land. It uses the results of a

research project that studies the development of settlements and polities by

comparing regional world-systems and studying them over long periods of time.

We

start with a brief stylized overview of our version of the evolution of

qualitatively distinct economic institutions and then we will elaborate and

qualify this model by examining different world regions and some particular

cases. In small-scale and egalitarian systems social production is mainly based

on shared conceptions of norms that designate obligations among members of kin

groups. Anthropologists call this the kin-based

mode of production (Wolf 1997). It

is based on consensual moral orders that are imbedded in the mother tongues

that people learn from childhood. The

mobilization of social labor is primarily organized by means of family

obligations based on sharing and reciprocity (Sahlins

1972). In some of these small-scale societies there is also ritualized (sacralized) gifting that reinforces alliances across

households, settlements and sometimes across the boundaries of independent

polities (Douglas 1990). Most of these small-scale systems are egalitarian in

the sense that there may be some gender and age inequalities, but there are

only small inequalities across households.

As sociocultural systems became more

complex, hierarchical kinship distinctions emerged that allowed elites to use

institutionalized power to accumulate resources and to regulate the uses of

land and other valuable natural resources. Classes, forms of property and

prestige goods systems emerged that made it possible for the chiefly elite to

appropriate some of the labor and goods produced by commoners. In some of these

systems prestige goods emerge as a mechanism for symbolizing alliances among

village heads. Under some conditions prestige goods evolved into proto-money

that served as a more general symbol of value in trade networks. Intervillage and interpolity

exchange allowed surplus food to be acquired by villages that were experiencing

a temporary shortage without resort to raiding. In some systems prestige goods

were monopolized by elites and used to reward subalterns and to regulate

marriage, reinforcing the political hierarchy. These are called “prestige goods

systems” in the anthropological literature. But some egalitarian systems had

prestige goods or proto-money that mainly functioned to ensure the provision of

goods for the general population during periods of shortage (e.g. the Wintu – see Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998). Small-scale societies also differed in the

extent to which private property existed. Many had only the usufruct in which

procurement locations were allocated and reallocated by group decision-making

(e.g. the Wintu), whereas others designated privately

held procurement sites that were inheritable property (e.g. the California

Athabascans). But even when privately held sites existed these were not commodified because they could not be bought or sold.

In some systems specialized institutions of

regional control emerged within polities[7]

that were separate from, and over the top of, the kin-organized subsistence and

political economy. These were the first states, and the larger political

economy came to be based on various forms of tithing, taxation,

labor-appropriation and tribute. The general term for this kind of political

economy is the tributary mode of

accumulation. In some of the early states

primordial versions of commodified exchange emerged

such as lending money at interest and letters of credit, but most exchange

continued to be regulated by customary or politically specified rules and rates

of exchange (sharing, reciprocity and redistribution). Interpolity

(foreign) trade was usually carried out by representatives of the state – what

Karl Polanyi (1957a) called

“state-administered trade.” But there were also some early city-states that

specialized in trade. The commodified institutions

that emerged within early tributary states were surrounded by increasingly

powerful state-based institutionalized coercion that regulated most of the

economy, though there was still a sector in which kin-based reciprocity

operated (Zagerell 1986). For thousands of years commodified forms of wealth, land, goods and labor existed

and expanded within commercializing political economies in which

institutionalized coercion was the predominant mode of economic regulation.

Money, cylinder seals, the collection of interest on loans, sales of property,

slave markets, indebtedness, commercialized sexual services, and wage labor all

emerged during the Bronze and Iron Ages (Graeber

2011). There were waves of commercialization in which privately controlled

enterprises played a greater role in economic production and distribution

followed by periods in which states regained great control. Tributary states became semi-commercialized

and learned to extract taxes from business entrerprises

rather than simply confiscating them. And more and more semiperipheral

capitalist city-states specializing in trade and under the political control of

those who made profits from commodity production emerged.

We

define capitalism broadly as a mode

of accumulation in which an elite class of owners and controllers of the major

means of production derives most of its wealth from the production and

distribution of commodities and manipulations of money. This presumes the

existence of a market economy and so the Polanyian

processes of the commodification of goods, wealth, land and labor are well

advanced. But unlike Marx and many others we do not require that work be

primarily or mostly mobilize in the form of wage labor. Coming from the world-systems perspective, we

note that coerced cash crop labor (serfdom and slavery) were fundamental and

necessary parts of the development of modern capitalism, and we suppose that

earlier forms of capitalism also mobilized labor in these and other ways. [8]

The question of how labor was mobilized in the Bronze and Iron Age semiperipheral capitalist city-states is an important one

that has not been much addressed by historians, but should be. A capitalist

state is one in which the elites in control of the state accumulate wealth

mainly by means of profit from trade and the production of commodities.

Eventually

a rather highly commodified system emerged in Western

Europe during the period after the fall of the Roman Empire in which the power

of tributary states was weak. A large

number of semiperipheral capitalist city-states

concentrated first on the Italian peninsula and then spread across the Alps to

the low countries and then to the North Sea and the Baltic. These were agents

of an expanding Mediterranean and Baltic market economy. When territorial

states once again emerged after the infeudation that

followed the collapse of the Roman Empire,

the most powerful of them were shaped by the existence of this strongly commodified regional market economy. The emergent political

elites were dependent on support from merchants and bankers to meet the costs

of raising armies in this very competitive European interstate system. We agree

with Wallerstein (2011:63) that the nature of

European agriculture and class relations were important reasons why emergent

European states were more dependent on capitalists than were states in China or

other rice-growing regions (see also Palat 1995) .

The

first core state (not a semiperipheral city-state)

that was controlled by capitalists was the Dutch federation in the 17th

century. This signaled the arrival of a capitalist world-system in which the

logic of profit making instead of tribute gathering had moved from the semiperiphery to the core and to systemic predominance. The

stylized model presented above needs examination regarding apparent exceptions

and possible misconceptions. Hence we tell our story for different world

regions and examine particular cases that may seem problematic, paying special attending to the actions of

states that specialize in trade and to the issue of “capitalist imperialism.”

Semiperipheral Capitalist

City-States and Commercialization in the Bronze and Iron Ages

We now examine ways in which semiperipheral capitalist city-states may have been agents

of commodification in the Bronze and Iron Ages. We define capitalist states as

those in which greater than half of

appropriated surplus derives from profits from trade and the state is

substantially controlled by those who obtain most of their wealth from

commodity production or market trade. A city-state is defined as an autonomous polity in which the territory

of sovereign control is limited to a single large city and some surrounding

agricultural land.[9] So a capitalist city-state is a city-state in

which over half of the accumulated surplus is derived from trade or commodity

production and that state is controlled by those who accumulate profits. Our focus on these entities stems from

Fernand Braudel’s (1984) discussion of “world

economies” and from Frederic Lane’s (1973, 1979) historical studies of Venice

and his conceptual essays about the nature of “violence-controlling

enterprises.” We have been further

inspired by David Wilkinson’s (2014; 2015) consideration of the nature of

capitalist empires. Wilkinson, also inspired by Braudel,

starts with Venice, Genoa and the Hanseatic League and then looks for and finds

similar entities in earlier ages and far-flung places. We start with the early Bronze Age, and use

Wilkinson’s insights and definitions in our examination of important cases. [10]

The ancient states that emerged in

Mesopotamia were all city-states, but they did not specialize in trade. We

suspect that nearly all primary (pristine) states (states that emerge in a

region in which there have not previously been states) were city-states in

their early years. City-states that specialized in trade emerged in the early

Bronze Age. We note that these specialized trading polities encouraged the

production of a surplus for exchange and that the institutional innovations

that they developed were often taken up by adjacent tributary states, which

impelled internal commercialization.

The capitalist

city-state phenomenon is clearly a different kind of semiperipheral

development from that of the semiperipheral marcher

state.[11] These states pursued a policy of profit

making rather than the acquisition of territory and the use of state power to

tax and extract tribute. They emerged in

the “interstices,” the spaces between the territorial states in world-economies

in which wealth could be had by “buying cheap and selling dear” (merchant

capitalism). One of their consequences was the expansion of trade networks

because their commercial activities provided incentives for farmers and

craftsmen to produce a surplus for trade with distant areas. Thus the

capitalist city-states were promoters of commodification and inter-regional

economic integration.

Most

of the early capitalist city-states were maritime regimes that made profits by

moving goods across the water[12]

e.g. Dilmun. But the old Assyrian city-state used

donkey caravans to move tin and bronze long distances (Larsen 1976). This paper

examines the role that semiperipheral capitalist

city-states played in the rising predominance of money economy, production for

exchange, and state power used for the purpose of accumulating profits rather

than taxes and tribute.

Semiperipheral capitalist city states are autonomous states

that pursue strategies of merchant capitalist trade and (often) the production

of commodities. Before the emergence of the predominance of capitalism in the

modern system these operated in the context of world-systems in which the

predominant mode of accumulation was based on the extraction of tribute and

taxes by means of state-organized institutionalized coercion.

Polanyi claimed that true markets did

not emerge until Iron Age Greece. But in

ancient Southwest Asia and in Mesoamerica, all parties recognized certain

neutral territories as international trade enclaves. These “ports of trade”

(Revere 1957; Chapman, 1957) allowed international exchange to go on even

during periods of warfare between states. Some of these neutral territories

were small cities near the boundaries of larger polities. But each Mesopotamian

city also had a port district within it, and these city districts were often

also treated as if they were neutral free-trade zones (van de Mieroop 1999). Scholars disagree about whether it was

primarily administered trade or market trade that occurred in these enclaves. Ratnagar (1981,: 226–227) contends that Dilmun

(Bahrain) in the Persian Gulf performed this port-of-trade function in the

exchanges between the Harrapan civilization of the

Indus River valley and Mesopotamia. He also cites evidence that indicates that

the Dilmunites later took on the functions of

middlemen carriers operating between the great states, thus becoming early

forbearers of the specialized trading city-states of the Phoenicians.

The rise of the early

empires was accompanied by the continued expansion and deepening of trade

networks (Jennings 2010). Periods of peace and the extension of imperial

governance allowed trade to become more intense and goods to travel farther.

The commodification of goods and wealth had long been emerging within and

between the states of Mesopotamia. Contracts of sale of lands and interest-bearing

loans were known from the Early Dynastic period, and prices were clearly

reflecting shortages in the Ur III period

In the Old Babylonian

period we find a clear instance of a semiperipheral

capitalist city-state. This was the Old Assyrian merchant dynasty centered in

the city of Assur on the upper Tigris (in what is now Syria), with its colonial

enclaves of Assyrian merchants located in distant cities far up into Anatolia

(what is now Turkey) (Larsen 1976, 1987). Assur was a land-based merchant

capitalist city-state with a far-flung set of colonies in the midst of an

interstate system in which most states were still extracting surplus from their

own peasants and pursuing a strategy of territorial expansion by means of

conquest. The Old Assyrians maintained an effective structure of

self-governance and religious devotion to the God of Assur that allowed them to

coordinate the activities of their central city and its distant colonies. This

is an early instance of what Philip Curtin (1984) called a “trade diaspora,” in

which an ethnic or religious group specializes in cross-cultural trade in a

region of great cultural diversity.[13]

The merchant capitalism of Assur, unlike that of most

capitalist city-states, was not based on sea trade (as were, e.g., the Phoenician,

Italian, and German city-states). But the Old Assyrians did occupy a key

transportation site on the Tigris that enabled them to tap into profit streams

generated by the exchange of eastern tin and Mesopotamian textiles for silver.

Bronze was being produced in Anatolia using copper from the north and tin

imported from Bactria (Afghanistan). The demand for tin was great, and the

merchants of Assur were able to make large profits by negotiating trade

treaties with the many states along the trade routes that allowed them access

to markets at agreed-upon taxation rates. They also organized the

transportation of goods over long distances by means of donkey caravans, and

they maintained an effective structure of self-governance and religious

devotion to the god of Assur that allowed them to coordinate the activities of

their central city and its distant colonies.

Much of the

evidence that we have about the institutional nature of exchange carried out by

the Old Assyrian city-state and its colonies comes from the Kultepe

tablets at Kanesh, an archive of business records and

letters that show how the merchants organized and governed their business

activities (Veenhof 1995). The records show that the

merchants were trading on their own accounts for profit. They were not agents

of the Assyrian state carrying out “administered trade ” akin to tribute exchanges

among states. As mentioned above, Karl Polanyi (1957a) had used an early and inaccurate examination of

the Kultepe tablets as evidence that the Assyrian

trade was state-organized exchange rather than market exchange. Polanyi

underestimated the antiquity of market-based exchange. But he was right to

claim that market exchange was an invention that emerged slowly in the context

of kin-based reciprocity and state-based administered trade.

The later history of Assur is also an

interesting case that is relevant for our understanding of semiperipheral

development. The Old Assyrians and the city of Assur were conquered by Hammarabi, the Amorite king of Babylon in 1756 BCE. The

Amorites were originally Semitic-speaking nomadic people from the mountains of

Syria. But they conquered states in Mesopotamia and established kingdoms in the

late Bronze Age. Thus the status of the claim that the Neo-Assyrians were a semiperipheral marcher state is based on the originally semiperipheral location of the capital far up the Tigris,

and on the conquest of the capital by formerly peripheral Amorites.

The Amorites became

the ruling class, though they adopted the language and some of the religion of

the Assyrians. Their much later re-emergence as the Neo-Assyrian Empire was a

fascinating instance in which what had earlier been a semiperipheral

capitalist city-state eventually adopted the marcher state strategy of

conquest,[14] and their

success in this latter venture created an empire upward sweep that was larger

than any other that had been before it in Southwestern Asia (Inoue et al 2012).

Capitalist

city-states and ports of trade

Sabloff and Rathje (1975)

contend that the same settlement can oscillate back and forth between being a

“port of trade” (a neutral territory that is used for administered trade

between different competing states and empires – see Polanyi et al 1957) and a “trading port” (an

autonomous and sovereign polity that actively pursues policies that facilitate

profitable trade). This latter corresponds to what we have meant by a semiperipheral capitalist city-state. Sabloff and Rathje also contend

that a trading port is more likely to emerge during a period in which tributary

states within the same region are weak, whereas a port of trade is more likely

during a period in which there are large and strong tributary states.[15] Sabloff and Rathje carried out an archaeological investigation of

Cozumel, an island off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. Their

project on Cozumel was designed to try to test the hypothesis that it had been

a trading state with a cosmopolitan and tolerant merchant elite during the

so-called Late Post-classic period of the Mayan state system just before the

arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century (see also Kepecs,

Feinman and Boucher 1994). There had long been a busy

coastal trade network based on transportation in large dugout canoes among

Mayan and Mexican polities along Caribbean coast of Mesoamerica (McKillop 2005

and see Figure 3). If Sabloff and Rathje are right

autonomous trading ports (semiperipheral capitalist

city states) are more likely to emerge during the fall part of the cycle of

rise and fall of empires that all state systems seem to exhibit.

Figure

1: Linda Schele's drawing from an incised bone found

at Tikal, showing a number of Mayan paddler gods carrying a maize god in a

dugout canoe. © David Schele, Foundation for the

Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. www.famsi.org

This general idea also corresponds

with the notion that world-systems have oscillated between periods in which

they are more integrated by horizontal networks of exchange versus periods in

which corporate and hierarchical organization is more predominant (Ekholm and Friedman 1982; Blanton and Fargher

2012)). Such oscillations may have been

based on the alternative successes and failures of tributary marcher states and

capitalist city-states.

The

upward sweeps of empires in which very large empires emerged in regional

world-systems for the first time were probably facilitated by the actions of

specialized trading states. By extending trade networks local producers were

encouraged to produce for exchange and for export. This increased the value of

territories for expanding states. The

ground was prepared for the upward sweeps of empire conquest by the activities

of capitalist city-states. If this is true upward sweeps in which larger states

emerged to encompass regions that had already been unified by trade should have

occurred after a period in which semiperipheral

capitalist city-states had been flourishing. [16]

Regarding upward sweeps of the population sizes of cities, these generally

followed upward sweeps of empires because it was empires that built the largest

cities as their capitals. The settlements of semiperipheral

capitalist city-states were usually much smaller than the capital cities of

empires. As we shall see below, Carthage was the only capitalist city that

became the largest city in a world-system until the rise of London.

More

Capitalist City-States: the Phoenicians in the Eastern Mediterranean

In the Eastern Mediterranean the Minoans on

Crete and the Mycenaeans in the Aegean had carried on

an early sea-going trade. During the

late second millennium BCE the Mediterranean was upset by migrations from the

north, peripheral peoples who the Egyptians called the “Sea Peoples.” These sea-going raiders disrupted the

sea-borne trade relations between Egypt and the Levant. The early Lebanese town of Byblos had long been

a tributary supplier of cedar to Egypt, but the arrival of the Sea Peoples interfered

with this trade (Cline 2014).

Eventually the new peoples settled on

the Lebanese and Palestinian coast and mixed with the older Semitic tribes

there. Out of this admixture the

Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon emerged,

transforming piracy into merchant capitalism, an instance of what ecologists

call the emergence of mutualism from predation.

The Phoenicians specialized in trading across the whole Mediterranean,

especially in exchanging with primitive peoples to whom the products of the old

East were, at first, preciosities (prestige goods). They also maintained a degree of autonomy as

carriers of goods between empires, especially the Egyptians and the

Assyrians. The Phoenicians established a

colony for the production of copper on Cyprus, and began a manufacturing

industry that provided inexpensive glass vases to mass markets throughout the

Mediterranean. They had stolen the

Egyptian secret of glass production and improved upon it for use in the carrying

trade (Frankenstein 1978; Herm, 1975; Markoe 2000).

Thus the Phoenicians expanded the

“exchanging unequals”, in which trade occurs between

peoples that have not previously been integrated by exchange and so the items

have values that are unrelated to those of the separate economic spheres (Amin

1980). With repeated and increasing

exchanges the formerly separate regions become integrated into a single system

of economic value. Buying cheap and

selling dear (arbitrage) was the specialized purpose of the Phoenician

city-states. These independent temple-cities of coastal Lebanon were early

examples of autonomous capitalist states in which profit-taking through

commerce was the dominant raison d’etat (purpose of the state). Their success led to “hiving off” in which

groups of Phoenicians would to abroad to establish new city-states. They

eventually spread as far as present-day Cadiz (Gades)

on the Atlantic coast of Spain, and they traded down the Red Sea to East Africa

and India and down the west coast of Africa, where they had a port at Moghador in what is now Mauretania. The Phoenicians also had alliances with the

land-based Hebrew states of Judah and Israel, building the temple at Jerusalem

under contract.

There are intermediate forms between a

completely uncommodified exchange network and one in

which commodification is the

predominant form. Land, wealth and labor

are never perfect commodities in any historical system, even in the

present. Rather commodification is a

matter of degree. The Phoenicians

engaged in merchant capitalism by

buying and selling the products of different, relatively isolated areas around

the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. In doing this they brought the separate

economies of these areas into interaction, subjecting the division of labor

within each to the market forces generated in the network as a whole. The Phoenicians also produced manufactured

goods for export, and these were not only prestige goods. Of course one of

their most important exports was a prime example of a prestige good. They knew

the secret of how to die cloth with a brilliant purple derived from sea snails

and so they had a monopoly on “imperial purple” which every king and emperor

needed to symbolize power. They also specialized in producing cheap copies that

could expand market demand by lowering prices. The Phoenician glass implements

industry and the textile industry were not just merchant capitalism, but rather

production capitalism in which imported technical knowledge was applied to the

mass production of commodities (Herm, 1975: 80). We do not know how the logic of costs

operated regarding raw materials, built environment and labor in the cities of Tyre and Sidon where these industries were located. The commodification of labor power may have

been constrained in many ways, by kin networks or state regulation. But it seems reasonable to assume that these

forms of labor control, however they were organized, were influenced by the

competitive logic of the larger Mediterranean political economy.

The other great contribution

that the Phoenicians made to the culture of the Central PMN was the phonetic

alphabet. The Phoenicians seem to have

adapted earlier phonetic alphabets from Egypt and Ugarit and spread their

version all over the Mediterranean. A

phonetic script allows sounds to be represented by symbols. Hieroglyphic

writing represents ideas instead of sounds, so that thousands of characters

must be memorized in order to achieve literacy. Phonetic alphabets can

represent language with only several dozen symbols. This makes reading and

writing possible without having to spend years memorizing characters that

represent ideas. This implementation of

a new technology and its adaptation to everyday life was a huge contribution of

the Phoenicians and was an important part of their contribution to the spread

of market exchange in the Mediterranean.

Semiperipherality seems to facilitate

implementation of new technologies and organizational forms rather than the

original invention of those forms. The genius of both semiperipheral

marchers and semiperipheral capitalist city-states is

in knowing which innovations borrowed from elsewhere to invest in.

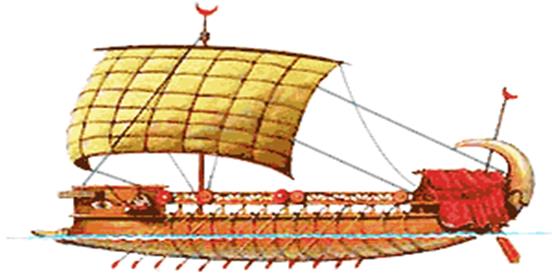

Figure 2: Phoenician

war galley c.700 BCE

Dominant powers at sea, the Phoenicians

built their cities on promontories or islands where they could be protected

from land attack. Tyre

was built on a rocky reef that was separated from the the

mainland by open water. It was only conquered after Alexander's army built a

causeway to it (Markoe 2000). Although fairly

autonomous, as mentioned by Diakonoff above, the

Phoenicians were not averse to paying tribute to whichever land-based empire

was currently responsible for the peace. They allied with the Persians in their

war against Greece, thereby gaining the permanent enmity of the Greeks, who characterized

them as “pirates.” The Phoenicians never achieved political unity amongst their

far-flung cities, and one of their split-off groups founded Carthage, to become

the center of a largely independent

trade network in the Western Mediterranean. The Carthaginians long battled with

the Greeks over Sardinia, and in one of their temporary conquests of a Greek

colony they discovered the superior art and craft products of Greek

culture. After this, statues of Greek

gods appeared in the gardens of Carthaginian aristocrats, although when they

were direly pressed by a Greek conqueror from Sardinia, they flooded back to

their old religion, carrying out a massive human sacrifice to try to appease

their old gods.

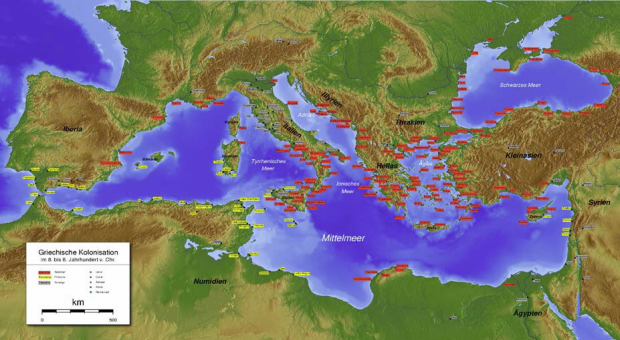

Figure 3: Greek and Phoenician

colonies in the Mediterranean, 4th century BCE . Source: Griechischen und phönizischen

Kolonien.jpg. Gepgepgep

The rise of Carthage was due to the successful

trading enterprises of its Phoenician founders.

Carthage became the largest city in the Central PMN[17]

in terms of population size (Inoue et al

2015), whereas earlier and later semiperipheral

capitalist city-states were more usually smaller cities specializing in the

carrying trade between the larger capitals of territorial empires. Carthage

began as a typical Phoenician city-state specializing in trade rather than

conquest, but it shifted toward the territorial strategy and this may be why

the city became so large (Ameling 2011). Though

Carthage did develop a sizeable territorial empire, it was not large compared

with earlier or contemporary largest empires. But its combination of trade and

conquest produced an urban population size upsweep. Regarding the issue of capitalist

imperialism, Walter Scheidel’s (xxxx)

essay on Carthage points out that the politics of empire involves strong

contradictions because an expanding empires granting of rights to conquered

territories necessarily reduces the value of the rights of older citizens.

The Greek city-states invented a new

type of polity that combined sea-borne trade with advanced commodity production

in agriculture (Roztoftzeff 1941). The Phoenician

temple-cities were so specialized in trade that they did not usually concern

themselves with revenues or profits from agricultural land, preferring to

import most of their food. Their colonies in the Western Mediterranean, like

the original cities on the Lebanese coast, were set up on promontories, and

oriented toward the sea. The Greek

polies, on the other hand, were associations of landholders. Their uniqueness

was not in their autonomy from imperial rule. This was shared by other autonomous

cities of Western Asia and the Mediterranean.

What made the Greek cities different was the small and inconsequential

nature of the state sector compared with the private sector (Diakonoff, 1982).

Sparta, of course, was a notable

exception.

The polity of most of the Greek city-states

was primarily an association of private landowners rather than itself a major

landowner and economic sector. This, and the high level of commodity

production, was the main feature that made Greek society different.

Unlike the Phoenicians, who, with the

exception of Carthage, only set up ports

of trade, the Greeks had more traditional attitudes toward expansion and

conquest. The purpose of conquest was

booty and the purpose of colonies was to settle citizens who could farm, and

provide food for the mother city. The

cultural disapproval of merchants did not prevent Greeks from engaging in

trade, but it may have partly accounted for the large number of foreigners (metics) who lived in

Athens. While most Greek colonies were established

for the purposes designated above, there were a few that specialized in trade

(Curtin, 1984). And as the cultural

Hellenization of the Central PMN proceeded, many Greeks became long-distance

traders.

Karl Polanyi argued in favor of the existence

of price-setting markets at Athens in his essay entitled “Aristotle Discovers

the Economy” (Polanyi 1957b:87). He

contended that coinage in small denominations indicates a real peoples’ market

in which it had become possible to buy a prepared meal on the street. Greek

generals undertook to provide meals for their troops on the road by encouraging

local provisioners to set up markets ahead of the

army's arrival. Polanyi saw these as indicators that a generalized commodity

economy had emerged within the Greek sphere of influence.

How should the political economy of the early

Central System be described? Within the great empires trade and production for

exchange grew, but two tendencies limited both.

As of old, empires tried to monopolize exchange. This was accomplished

by trying to convert long-distance trade into tribute-taking and local trade

into royal monopolies by which the king

could extract surplus product from a dependent population. But private trading and markets tended to

emerge and to grow. They were often constrained by a shortage of generalized

media of exchange (money). Shortage of

money stimulated and was reinforced by usury (very high interested

loan-making), and by the tendency of emperors and kings to horde money.

In the interstices between the tributary

empires, as along the Lebanese coast, and in other peripheral and semiperipheral areas, market trade was less constrained.

This is where the capitalist city-states emerged, the purest cases being the

autonomous Phoenician cities of the Eastern Mediterranean. The Greeks, especially at Athens,

demonstrated that even an agricultural state can expand market market exchange and can benefit from it. This trick, the

coexistence of a tributary mode of accumulation with a large measure of

commercialization, was pioneered in semiperipheral

Athens, but was later learned by some of the large commercializing empires

(Sanderson 1995).

The literature on the Italian and

German city-states is vast. Fernand Braudel (1984)

defined a “world economy” as rotating around a single economically central

city. Frederic Lane’s studies of Venice led him to examine the relationship

between state power and profits. He developed the idea of “protection rent” by

which he meant the differential return to capitalists due to having the support

of a state that provided protection at cost or with less overhead (Lane 1979).

The profit difference between this and that of capitalists in competing states

that were less efficient is termed protection rent. This idea is still important in the notion of

“the lean state.”

Giovanni Arrighi

(1984) saw the original hegemony that led the emergence of predominant

capitalist in Europe as due largely to an alliance between Genoa and Portugal.

The Genoese supported Portugal’s effort to circumnavigate Africa as a way of

going around the Venetian monopoly of spices from the East Indies.

Semiperipheral Capitalism in

Other World Regions

It

is important to ask about the existence of

capitalist city-states in other world regions. What happened to

capitalist efforts to gain state power in South Asia, East Asia and South East

Asia? Commercialization was occurring in these regions as it did in the West.

The tributary states were developing commodified

wealth (money), markets, and small commodity production within the tributary

states. The Sung Dynasty in China is famous for its use of paper money and that

vast scale of its steel industry. Melakka, a

city-state in what is now Malaysia, was a semiperipheral

capitalist city-state in the sea-borne carrying trade and allied with China

(Curtin 1984). But there was also a maritime capitalist state in Fujian and

Taiwan that emerged in the 17th century transition from the Ming to

the Qing dynasties (Arrighi 2007:333-4; Hung

2001). Koxinga was the local nickname of the adventurer Zheng Chenggong who took Taiwan from the Dutch and tried, for a

time, to maintain autonomy from the Qing dynasty as a semiperipheral

capitalist city-state. Instead he returned to the mainland in an effort to

depose the Manchus, but failed. The semiperipheral capitalist city-states in the East were not

as densely concentrated as they became in Europe, where the Italian and German

Hanse city-states flourished to create a regional maritime economy that

influenced the emergence of national states. Capitalists were not absent from

the stage in East Asia, but neither did they succeed in conquering the

commanding heights of state power as they did in some of the emerging powerful

states in the West.

[more on

specialized trading cities in East Asia (Osaka) and the story of capitalism in

Japan told by Randy Collins and Stephen Sanderson]

Southeast Asian Trading City-states

Indian and Indonesian commerce made the Indian

Ocean a very busy place from the Roman Empire times on. The Roman Empire had a

huge spice trade from India and Indonesia (Miller 1969; Crone 1987 disputed the

size and importance of this trade, but archaeology has since proved Miller

right). India and Indonesia had huge

voyaging and trading enterprises in their own right. East Africa was explored by Indonesians

during Roman times, and Madagascar was colonized from Borneo and to a lesser

extent other Indonesian islands by 500 CE.

It has been noted that the south Indian coast

is littered with Roman coins and other goods, but none occurs in China (Hansen

2012), and in fact there are almost no Indian imports in China either. Later, however, trade from west to east

became extensive. Medieval records show

that China was importing quite large amounts of frankincense and other

items. Apparently the rise of the

Islamic empires was more important than Rome, in large part because southeast

Asia was so undeveloped in Roman times that it could not serve as a major

throughput zone. However, after 600, the

southeast Asian cities managed a good deal of throughput trade and voyaging,

bringing such goods as “frankincense, storax…,

myrrh,…dragon’s blood [resin], glassware,…ivory, gems,…rosewater and dates” (Heng 2009:32).

The first

known city-state in the region was called Funan in

modern Chinese, representing what was originally probably the Khmer word Phnom,

as in Phnom Penh. This kingdom was more

or less the modern Khmer area: Cambodia and far south Vietnam. It was evidently Khmer-speaking, and had ties

with India, beginning the heavy influx of Indian high culture to the area. It flourished ca. 100-600 CE. Meanwhile, China was conquering northern

Vietnam, bringing its own influences.

This was the beginning of the cultural mix that led to the region being

called “Indo-China.” The city Oc Eo was a trading city in the

southern area of Funan, and probably a key trading

city. The whole kingdom seems to have

depended on rice agriculture, but also on the India-China trade and on

Southeast Asian trade with both. Almost

completely unknown city-states south of it are barely recorded in Chinese

records from China’s time of disunion in the 3rd-7th

centuries.

Later, there were countless local trade-based

states and city-states, mostly in the area from southernmost Vietnam and

Cambodia through Malaya to Sumatera and Java, with outliers (late, mostly) in

the Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Moluccas. There were similar city-states (mostly much

earlier) in south India.

Interestingly, East Asia never had trade-based

city-states. The nearest approach was

the Ryukyu kingdom with its capital at Naha, but even the Ryukyus

were agrarian, producing a wide variety of foodstuffs. The Chinese world always privileged

agriculture over trade. The lowest

farmer was theoretically superior to the highest merchant, though in reality

“money talked.” Chinese and

China-influenced East Asian polities were all agrarian, based on land rents (in

the broad sense, including taxes) from large hinterlands.

Shadowy

references to “polities” (small city-states, quasi-independent cities, or local

tribal groups) exist from the 600s, with Chinese names like Holotan,

Pota, Pohuang, Holing and Shepo assigned to them (Heng

2009:23-5). More identifiable is Malayu, which at least has its own name—it developed into Srivijaya. The

general Chinese term for the region, or part of it, was kunlun, confusingly the same as

the name of a mountain range in central Asia.

Srivijaya flourished from the 7th to the 13th

centuries and included Sumatera, much of Java, and the coasts of Malaya. Srivijaya was an

expansion of the Palembang city-state in the 600s or thereabouts. It lasted, with migration of the capital to Malayu-Jambi, till around 1300, and even after that

Palembang and Malayu-Jambi survived as trading

cities. It seems to have been a sort of

Venice of Indonesia: holding maritime lands but basically a trading urban

complex (see also Wilkinson 2015).

At its peak it conquered the coastal areas of

most of today’s Indonesia, and it is thus hailed as an ancestor of

Indonesia. It developed and spread the

Malay language. It was trade-based and

centered on port cities, especially Jambi (the early capital) and Palembang

(later capital, and major city) on the southern east coast of Sumatera across

from (and south of) modern Singapore.

The capital later reverted to Jambi (Malayu). This was a very powerful empire and a major

player in world trade. It had very

extensive trade connections with the Tang and Song Dynasties. (It became Sanfoqi

in modern Chinese, reflecting a medieval pronunciation something like Samfokay.) In spite

of its theoretically large landholdings it qualifies as a trade-based

city-state empire, the way Venice in the 15-17th centuries

does. Its success had much to do with

its lack of coherence and monolithic rule; it could adapt, contract or expand,

change, delegate local authority to local rulers, and otherwise live an

amoeboid life (Lieberman 2009:779). Even

after it fell, Malayu-Jambi continued as an important

trade city.

Contemporary was Mataram,

in Java, but it was land-based and a more normal (for the time) agrarian

state. It was replaced by Majapahit, based in Java, which lasted around 1293-1600 and

included basically the modern Indonesia (less New Guinea but including also at

least some influence over Malaya and neighboring areas of Thailand, and also up

into the Philippines). Its last

dwindling power fell to Europeans. Its

successor state, Mataram (the second; fl. 1580-1670),

was like its predecessor of the same name in being a land-based state centered

on interior Java.

Major Malayan ports including Tambralingga, Ligor, Langkasuka, Kelantan, Trengganu,

Pahang, and Temasik (now Singapore) were

theoretically under Srivijaya, at least most of the

time (see map, Heng 2009:105). Some of these probably spoke Mon-Khmer

languages rather than Malay. They must

have operated fairly independently most of the time, given the difficulties of

shipping. On the other hand, we know

from records and wrecks that shipping was incredibly well-developed, both

technologically and economically, in those centuries. It was very far ahead of European shipping in

terms of marine technology, with fore-and-aft rigging, stern rudders,

watertight compartments, outriggers, efficient rigging management, possibly the

compass, and other advanced things not known in the west. The extent of trade is shown by the fact that

a local outbreak of violence in Guangzhou in the 9th century led to

the deaths of thousands of traders from an “Arab” trading settlement thought to

number 200,000 people; most were local Chinese or southeast Asians, but there

were indeed very large numbers of Arabs and Persians.

Later

independent city-states included Singhapura

(Singapore) and Melaka (fl. 1377-1511, then a Portuguese colony, then Dutch,

then English).

Marco Polo came home to Italy by the sea route,

and considered it a routine trip; Buddhist monks had left earlier records,

showing that travel was very difficult in the early 7th century but

had become routine and fairly safe by the 8th.

Meanwhile,

many independent city-states and river-basin statelets

flourished in Malaya and elsewhere.

Melaka (Malacca) in particular rose around 1400 and lasts to this day,

after various conquests and wars. It is

now basically a tourist city. When

co-author E.N. Anderson was there in 1971 it was a fascinating town—a sleepy

backwater that preserved the glorious architecture of the 16th-19th

centuries. It was a real time-warp.

The other

states of West Malaysia are also based on old trade centers: Johore, Kelantan, Trengganu,

Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Kedah. The only

exceptions (of sorts) are Penang, developed by the British, and Negri Sembilan, populated by relatively recent immigrants

from Sumatera—but they were following trade routes. In Indonesia, Aceh, now a terrible thorn in Indoesia’s side because of its Islamic extremism and

constant rebelliousness, was a major trade center, being the first port that

Arab and Indian traders would hit when they sailed east. Aceh was a major player in Southeast Asian

politics for centuries, and without its extreme brand of Islam might have been

the great modernizing force in the islands.

(Instead, Minangkabau came nearest to having that distinction.) Aceh’s resistance to the Dutch was one of

the most incredible stories in the annals of colonialism; total unity, superb

guerrilla competence, dauntless courage, incredible ability to maneuver

politically, and undying hatred of outside interference kept it independent

during a 25-year war that was one of the costliest and bloodiest ever faced by

the Netherlands. The Dutch were fought

to a draw; they occupied Aceh but never managed to govern the place

effectively. The great Dutch Islamist Snouck Hurgronje (1906) wrote a

book at the time about Aceh and the war; it is fascinating because Hurgronje could not help doing a thorough job and showing a

grudging admiration for Aceh courage, but at the same time his pen literally

dripped hate because of what the Acehnese had done to his country and some of

his friends. This fascinating read in

totally UN-objective history has just been issued in a new version (2009-10).

Surabaya, Banda, Jakarta, and other major

coastal cities of western Indonesia all have trading heritages. The Riau-Lingga

islands, now inconsequential, were a center of activity for a time, because of

their centrality on trade routes. In the

Philippines, Manila developed as a center of Chinese trade, and had hundreds or

thousands of Chinese traders when the Spanish took the islands in 1571.

The scope

of trade in these cities was incredible.

They sent countless vast ships around the islands, and carried on active

trade in huge ships and flotillas with India, China, and even farther

afield. Arab and Indian traders swarmed

to them. Chinese began to settle in the

“Nanyang” (“Southern Ocean,” i.e. the areas bordering

the South China Sea and Indonesian waters) in the Song Dynasty or earlier, and

this turned to a flood in Ming, following the great fleets led by Zheng

He. Settlements of thousands of Chinese

were in the area by 1600, and continued to grow and thrive. Bangkok is probably largely Chinese by

descent, and tens of millions of people of Chinese descent live in Vietnam,

Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia. In

Indonesia the Chinese tended to marry into the local societies, the resulting

population being the Peranakan (“those who have

become children [of the land]”).

(First-generation Chinese were called Totok,

in contrast.)

The local states were, however, mainly involved

in exporting local luxury items.

Especially important were many types of plant gum and wood used for

incense: sandalwood, gharuwood, Barus

camphor (named for the port of Barus in western

Sumatera), eaglewood, aloeswood, etc. Other items included tin (generally mined by

Chinese immigrants), rhinoceros horn, local ivory, gems (including rubies and

sapphires from Burma—late, at least), hornbill casques,

animal pelts, and, later at least, edible birds’ nests (from Collocalia swiftlets), sea cucumbers, specialty fish, and other foods

(Tagliacozzo and Chang 2011). In return, there was an enormous import of

silks and porcelain from China, and all sorts of fabrics from India, along with

some metal goods. Fabrics were the great

luxury and art form in island southeast Asia, and imported fabrics were the

symbols of wealth. (This is recognized

in the wry Malay proverb on poverty:

“Even though ten ships come, the dogs have no loincloths but their

tails.”) China’s rather inferior, but

cheap, cast iron was popular (Heng 2009:106). So were its copper coins. Porcelain from China, Thailand, and Vietnam

flowed everywhere in the region, especially in the 14-16th

centuries. The extent of this trade has

been revealed only recently, as shipwrecks have been found; it is now known

that ships loaded with many tons of ceramics were regular on the seas of the

area. Even the east African coast has

turned up many early Ming sherds.

The Ming Dynasty pulled steadily back on trade

after 1420, but could not stop it. The

fall of Ming and the chaos from 1630 to 1644 (and even after) slowed trade, but

it revived in the 18th century.

However, by then, Europeans were out-competing local people.

The common thread of all these city-states and

local empires is that they were the antithesis of Genoa, Venice, Amsterdam or

London. They never innovated or

developed much economically. Majapahit and presumably

Srivijaya were amazing cultural centers; the last

faint gasps of Majapahit glory, in Jogyakarta and Surakarta, were as aesthetically brilliant

as Venice in its glory. But this did not

translate into new science or technology.

Why did the Southeast Asian city-states and thalassocra tic empires not anticipate Venice, Genoa, and

Amsterdam, and invent capitalism? Early

European observers of the Indonesian city-states had no doubts. Marsden (1966, orig. ca. 1800) and Raffles

(1965, orig. ca. 1820) both have long, thoughtful, well-supported analyses of

why southeast Asia was behind the times, and they both concluded that the

problem was the heavy-handed, top-down control by kings and bureaucrats. This had also stifled China’s trade. The rulers in southeast Asia (like the

emperors of China) were more interested in maximizing their take of wealth by

gouging the merchants, and in maintaining their power by keeping merchants and

other independent souls down. Of course one

might argue that European monarchs tried this too, and sometimes

succeeded. As far as the southeast Asian

cities were concerned, the real difference, the “story behind the story,” lies

in the nature of the trade: luxuries

from the rainforest, as opposed to state-of-the-art manufactured goods. They imported everything requiring much

knowledge and skill. China, then as now,

could and did beat out everyone else at producing consumer goods cheaply and

efficiently.

The

European city-states generally were in the position that China occupied in

Asia: trading manufactured goods for raw materials from the periphery. Value-added always wins the game. Anybody can farm, and anyone with a

rainforest can extract precious woods and gums, but only a developed state with

a major institutional, educational, and physical infrastructure can indulge in

cheap mass production of manufactured goods.

It will thus have an advantage.

The more value added, other things being equal, the more the

advantage. The southeast Asian

city-states drew on tributary states and undeveloped hinterlands for forest

products. They were at the very bottom

of the value-added chain.

The costs

of being a primary-products exporter are serious. It makes sense for the elites to keep the

people as backward, ignorant, and divided as possible. This makes them easy to exploit, and prevents

them from getting ideas—such as progress, or freedom, or rebellion. The “resource curse” is well known in modern

societies, and it was, if anything, worse a thousand years ago, when local

rulers had a freer hand and primary production was really primitive

technologically in southeast Asia. (It

was already sophisticated in China by that time.) The only advantage the ordinary poor people

had a thousand years ago was that the implements of repression were not so

developed as now, and the elites depended on a fair number of educated and

fairly free-to-act courtiers, clerks, and local headmen as well as on a large

minimum-wage labor pool. They thus could

not indulge in genocide, mass political murders, and other traits of the modern

primary-production state. (Some states

outside Southeast Asia tried, and quickly fell.

Southeast Asia, always tolerant and imbued with local and Buddhist

values, did not try, until postcolonial regimes imitated their former

masters.)

Conversely,

China, though much less free than post-Enlightenment Europe, had neither the

will nor the means to repress education and educated people. The empire depended on having a numerically

huge number of educated people, and did not have the tax revenues to create a

true autocracy—though that meant that it also did not have enough tax revenues

to hire many of the educated, or to do much to develop. In any case, China remained the metropole, and the Southeast Asian city-states were

classically peripheralized, like the east Baltic and

Black Sea cities in medieval and Renaissance Europe.

The evolution of economic institutions and the

transition from City-States to a World State

A

Polanyian perspective on the emergence of

capitalism depicts waves of deepening of commodification interspersed by

periods of decommofication. No human society has ever commodified

everything. The moral and political orders shelter some aspects of life from

market forces and privatization. But the history of the modern world-system has

seen waves of commodification that correspond with changes in the nature of

political power and the logics of exploitation and domination. The issue of when capitalism became the

predominant mode of accumulation is still contentious, but the notion of waves

of expansion and deepening reduces this to quibbles about when to call a whole

world-system capitalist. Commodification

expanded and deepened from the Stone Age on, and the modern Europe-centered

system has become increasingly capitalist in waves of commodification and decommodification since the 13th century

CE. These waves of capitalism

corresponded to the increasing size of the hegemonic core state, but also to

changes in the structure of interpolity

relations. The old form of tributary

empire that involved conquering adjacent territory and extracting tribute and

taxes became supplanted by the emergence of thallasocratic

colonial empires in which a “mother country” establish sovereignty over distant

colonies in order to facilitate competitive commodity production and

profit-making. Recall that colonial empires were pioneered by both Phoenician

and Greek city-states, so the modern colonial empires were replicating a

strategy that emerged in the Bronze Age, but was interstitial between the

tributary empires (see Figure 4).

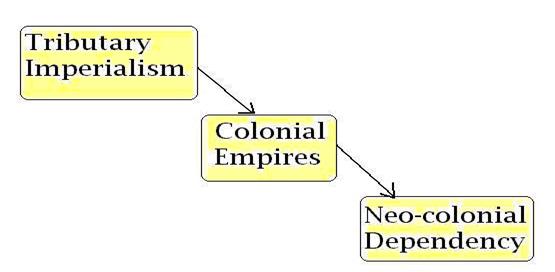

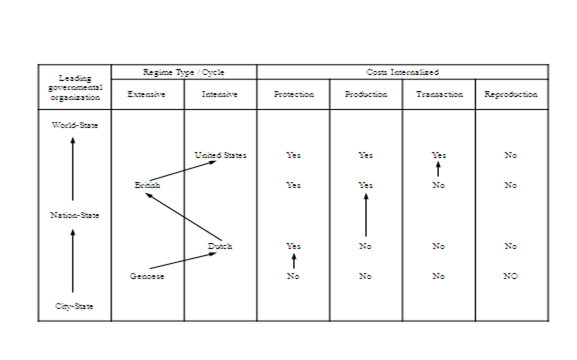

Figure 4: Evolution of forms of imperialism

Waves of decolonization since the late 18th

century have now transformed the system of colonial empires in to a system of

neocolonialism in which global power is exercised through International

Governmental Organizations, financial exchanges and property arrangements that

allow actors in rich and powerful countries to exploit, if not dominate,

non-core peoples. This demise of the

colonial empires creates a single global polity of formally sovereign

nation-states and a system in which economic power is stronger than it has ever

been at the level of a whole world-system. Such a system is ripe for the

emergence of a true world state, though that has not happened yet and may not

happen soon because the interstate system is highly institutionalized.

Figure

5 depicts Giovanni Arrighi’s schematic representation

of the evolution of economic and political institutions since the rise of the

modern world-system. He sees a transition from city-states (recall his analysis

of the key role of Genoa in the formation of the Europe-centered system) to

nation-states and then to an eventual future world state. He also notes an

oscillation in the forms of empire that may be analogous to earlier

oscillations between horizontal networks and more corporate forms of

organization noted by archaeologists, anthropologists, political scientists and

world historians (e.g. Blanton, Ekholm and Friedman,

and Wilkinson). And Arrighi’s

scheme also shows the deepening of commodification by the penetration of

regulation into the political economy with the waves of hegemonic rise and

fall.

Figure 5: Arrighi’s

evolutionary scheme of the deepening of commodification and forms of political

globalization. Source: Arrighi (2006: 206)

Arrighi’s scheme raises new

questions that are beyond our current focus on the importance of semiperipheral capitalist city-states, but it shows the

general direction which we intend to go in our analysis of the evolution of

institutions. We will eventually want to put our studies of semiperipheral

capitalist city-states in to a larger comparative work that examines

sociocultural evolution since the Paleolithic Age.

Testable hypotheses by the EmpCit project on the growth and collapse of empires and

cities since 4000 BCE are as follows:

(1 )cycles

of tributary empire strength and weakness interspersed with periods in which

there are more and larger capitalist city-states and capitalist empires.

(2)

Capitalist city-state expansion of trade networks makes it possible to

construct larger empires in the next round by strengthening transportation

networks and encouraging the production of surpluses for exchange.

References

Abu-Lughod, Janet 1991 Before European Hegemony: The World-System A.D. 1250-1350. New York:

Oxford

University Press.

Algaze, Guillermo. 1993. The Uruk

World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ameling, Walter 2011 “The rise of Carthage to 264 BC” Pp.

39-57 in Dexter

Hoyos (ed.) A Companion to the Punic Wars. New York: Wiley-Blackwell

Amin, Samir 1980. Class

and Nation, Historically and in the Current Crisis. New York:

Monthly Review Press.

Anderson, Eugene. N.

2014. Food and Environment in Early and Medieval China. Philadelphia, PA:

University

of Pennsylvania Press.

Appadurai,

Arjun (ed.) 1986 The Social Life of

Things: commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge:

Cambridge

University Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni 2006 “Spatial and other ‘fixes’ of historical

capitalism” Pp. 201-212 in C. Chase-

Dunn and

S. Babones (eds.) Global

Social Change. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bairoch, Paul. 1988. Cities and Economic Development Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Beaujard, Philippe. 2005 The

Indian Ocean in Eurasian and African World-Systems Before the Sixteenth Century. Journal of World History 16,4:411-465.

_____. 2009 Les mondes de l’océan Indien Tome I: De la formation de l’État

au premier système-monde Afro-Eurasien

(4e millénaire av. J.-C. – 6e siècle apr. J.-C.). Paris: Armand Colin.

_____. 2010. “From Three

possible Iron-Age World-Systems to a Single Afro Eurasian World-System.” Journal

of World History 21:1(March):1-43.

_____. 2012. Les mondes de l’océan Indien Tome II: L’océan Indien, au coeur des globalisations de l’ancien Monde

du 7e au 15e siècle. Paris: Armand Colin

Bibby, Geoffrey 1969 Looking

for Dilmun. New York: Knopf.

Blanton,

Richard E. and Lane F. Fargher 2012 “Market

Cooperation and the Evolution of the Pre-

Hispanic Mesoamerican World-System”

in Salvatore Babones and Christopher Chase-Dunn

(eds.) Routledge Handbook of World-Systems Analysis: Theory and Research London:

Routledge

Block,

Fred and Margaret R. Somers. 2014. The

Power of Market Fundamentalism: Karl Polanyi’s Critique.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Braudel, Fernand 1972 The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. New York:

Harper

and Row, 2 vol.

Brenner, Robert L. 1977: "The origins

of capitalist development: a critique of neo-Smithian

Marxism" New

Left Review 104, 25-92

______________1984

The Perspective of the World, Volume 3 of New York: Harper and Row.

Chapman,

Anne C. 1957 “Port of trade enclaves in Aztec and Maya civilizations” Pp.

114-153 in

Karl Polanyi, Conrad M. Arensberg and Harry W. Pearson, Trade and Markets in the Early

Empires.

Chicago: Henry Regnery.

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1988. "Comparing world-systems:

Toward a theory of semiperipheral

development," Comparative

Civilizations Review, 19:29-66, Fall.

Chase-Dunn,

C. 2008 “World urbanization: the role of settlement systems in human social

evolution” in World System History, [Eds. George Modelski and Robert A.Denemark],

in the

Encyclopedia of Life Support

Systems (EOLSS), Developed under the Auspices of the

UNESCO, Eolss

Publishers, Oxford ,UK, [http://www.eolss.net]

Chase-Dunn, C. 2013

“The evolution of systemic logics” https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows77/irows77.htm

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Kelly M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and Their Neighbors. Tucson: University of

Arizona Press.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and E.N. Anderson (eds.) 2005. The Historical

Evolution of World-Systems. London:

Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn, C., Thomas

D. Hall, Richard Niemeyer, Alexis Alvarez, Hiroko Inoue, Kirk Lawrence,