The Growth of Hangzhou and the Geopolitical Context in East

Asia

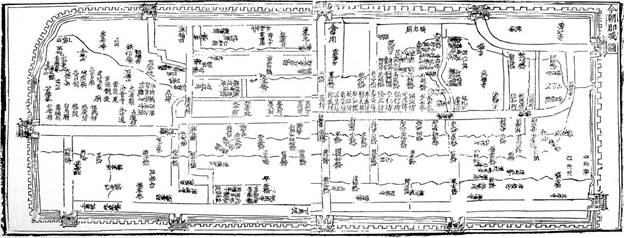

Schematic map of Hangzhou during the Ming dynasty

Chris

Chase-Dunn, Hiroko Inoue and E.N. Anderson

Institute

for Research on World-Systems

University

of California-Riverside

This is IROWS Working

Paper #111 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows111/irows111.htm

v. 8/16/16 1766 words

Hangzhou is

a large Chinese city at the southern terminal of the Grand Canal and connected

by river with the East China Sea near the mouth of the Yangtze River. Hangzhou was called Linan when it was

the capital of the Southern Sung dynasty. We are comparing changes

in the sizes of largest polities with changes in the sizes of largest cities in

the East Asian interstate system. We utilize three compendia of city size

estimates – those by Ian Morris (2013), Tertius

Chandler (1987) and George Modelski (2003). At first we had used

George Modelski’s (2003:63) estimate of 1.5 million

for the population size of Hangzhou in 1300 CE. We then discovered an

inconsistency in Modelski’s compilation. His Table 12

on page 63 shows 1.5 million for 1300 CE, but his note about Hangzhou on p 65

says it was 1.5 million in 1250 CE.

Like Baghdad, Kaifeng

was besieged by the Mongols and captured by them in 1232-3, reportedly with

great loss of life. In the meantime the Song dynasty had moved south and, after

a brief sojourn in Nanjing, selected Hangzhou as their capital. This then served

as the second base for economic growth that produced a powerful expansion of

maritime trade. Even after the Southern Song were finally conquered by the

Mongols (1279), Hangzhou continued to impress contemporary travelers including

Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo. The Venetian in particular left behind a

superlative account of that city that prompted many a trader and traveler from

Europe to reach out to Chinese markets. Once again, population estimates are

uncertain, and range as high as 2.5 m (Elvin 176) but a household enumeration

of the Linan capital commandery

(fu) (reported in Bielenstein

1987:50-1) suggests a figure of 1.5 million for about 1250. That is impressive but it did not

last long for as its port silted up and as the city lost its capital status, it

also abandoned its world position.”[1] Check bielenstein

Modelski’s estimate of 1.5 million for 1300 CE in

Table 12 must be a typographical error because Linan

was no longer the capital by then. It had been conquered by the Mongols in 1279

and the river had silted up. The estimated sizes of Hangzhou in the 13th

and 14th centuries vary from Chandler’s low ones (see Table 1) to

very high ones based on Mark Elvin’s(1973) belief in the reports of Marco Polo

(1992).

|

|

|

|

Size

(thousands) |

|

622 CE |

21 |

Hangchow |

60 |

|

800 |

23 |

Hangchow |

70 |

|

900 |

20 |

Hangchow |

75 |

|

1000 |

19 |

Hangchow |

80 |

|

1100 |

18 |

Hangchow |

90 |

|

1150 |

9 |

Hangchow |

145 |

|

1200 |

1 |

Hangchow |

255 |

|

1250 |

1 |

Hangchow |

320 |

|

1300 |

1 |

Hangchow |

432 |

|

1350 |

1 |

Hangchow |

432 |

|

1400 |

5 |

Hangchow |

235 |

|

1450 |

4 |

Hangchow |

250 |

Table 1: Population size estimates for Hangzhou made by Tertius Chandler (1987)

|

|

|

Size (thousands) |

|

1200 CE |

Hangzhou |

1000 |

|

1300 |

Hangzhou |

1500 |

Table 2: George Modelski (2003: 63 Table 12) (but see discussion above)

|

year |

Size (thousands) |

|

|

1200 CE |

1000 |

Hangzhou |

|

1300 |

800 |

Hangzhou |

Table 3: Ian Morris (2010: 118) estimates of the populations of Hangzhou

The Wikipedia

article on Hangzhou says:

During the Southern Song dynasty, commercial expansion, an influx of refugees from the conquered north, and the growth of the official and military establishments, led to a corresponding population increase and the city developed well outside its 9th-century ramparts. According to the Encyclopćdia Britannica

, Hangzhou had a population of over 2 million at that time, while historian Jacques Gernet has estimated that the population of Hangzhou numbered well over one million by 1276. (Official Chinese census figures from the year 1270 listed some 186,330 families in residence and probably failed to count non-residents and soldiers.) It is believed that Hangzhou was the largest city in the world from 1180 to 1315 and from 1348 to 1358.And:

Hangzhou was chosen as the new

capital of the Southern Song dynasty in 1132, when most of northern China had

been conquered by the Jurchens in the Jin–Song wars. The Song court had retreated south to the

city in 1129 from its original capital in Kaifeng, after it was captured by the

Jurchens in the Jingkang

Incident of 1127. From Kaifeng they moved to Nanjing, modern Shangqiu, then to Yangzhou in 1128. The government of the

Song intended it to be a temporary capital. However, over the decades Hangzhou

grew into a major commercial and cultural center of the Song dynasty. It rose

from a middling city of no special importance to one of the world's largest and

most prosperous. Once the prospect of retaking northern China had diminished,

government buildings in Hangzhou were extended and renovated to better befit

its status as an imperial capital and not just a temporary one. The imperial

palace in Hangzhou, modest in size, was expanded in 1133 with new roofed

alleyways, and in 1148 with an extension of the palace walls. From the early

12th century until the Mongol invasion of 1276, Hangzhou remained the capital

and was known as Lin'an. It served as the seat of the

imperial government, a center of trade and entertainment, and the nexus of the

main branches of the civil service. During that time the city was a

gravitational center of Chinese civilization: what used to be considered

"central China" in the north was taken by the Jin,

an ethnic minority dynasty ruled by Jurchens.

We end up using Ian Morris’s estimates. Morris’s note about

Hangzhou says:

1300 CE: Hangzhou, 800,000 (Bairoch 1988: 355); 7.5 points. Bairoch

suggests that four other Chinese cities

around 1300 had populations in the

200,000-500,000 range while Hangzhou was

“perhaps considerably larger.”

His calculations from the figures for rice

consumption, however, point more

precisely to 800,000, while Elvin (1973: 177)

calculates 600,000-700,000

from the rice figures. Rozman

(1973: 35) also thought 12th-13th century

Hangzhou’s population was over 500,000, and

could have been as high as 1million. Kuhn (2009: 205) and Christian (2004: 368)

also lean toward 1

million, and Skinner (1977: 30), 1.2 million.

I take the higher figure of

roughly 1 million for 1200 CE, and the lower

figure of 800,000 for 1300 CE,

by which time population was falling across

China as a whole. The city was

certainly the biggest in the world when Marco

Polo visited in the late 13

century (Kuhn 2009: 205-209), but the figure

implied by Marco’s

comments—5-7 million—must be far too high.

There was probably no way

Marco could have known Hangzhou’s population,

beyond the simple fact

that it was enormous compared to European or

Muslim cities of his day.[2]

The large size that Hangzhou reached in the 13th

century is relevant to our study of the ways in which changes in geopolitical

structures impact the sizes of cities. The usual path is that an empire arises

by conquest and then expands an old city or builds a new capital. But the

growth of Hangzhou is less directly a function of empire-building. The invasion

of Northern China by forest (Jurchin) and steppe

nomad (Mongols) marcher states pushed the urban functions that had been located

in the Song capital of Kaifeng toward the south, along with a substantial

migration of former residents of Kaifeng.

And this corresponded with the long-term rise of the Yangtze River valley as an important center of rice cultivation.

The Song Dynasty ruled at first from Kaifeng, well south of

Beijing, and the lower Yangtze was already building up. So when the Song

lost Kaifeng and had to move farther south, they naturally went to the southern end

of the Grand Canal, making Hangzhou the main and most strategically located

city in East Asia and one of the largest cities in the world in the 13th

and 14th centuries CE [3]

Hangzhou

Bibliography

Bairoch, Paul 1988. Cities and Economic Development: From the Dawn of History

to the Present. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press. P. 355

Bielenstein, Hans 1987 “Chinese

historical demography A.D. 2 to 1982” Pp 1-282 in Bulletin of the

Museum

of Far Eastern Antiquities, Vol. 59. Stockholm.

Britannica Concise Encyclopedia https://www.britannica.com/place/Hangzhou

Chandler, Tertius 1987 Four

Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellon Press

Cheung, Desmond H. H.2011” A

socio-cultural history of sites in Ming Hangzhou” A THESIS

SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE

DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF

PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE

STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0072182

Elvin, Mark. 1973 The Pattern of the Chinese Past. Stanford: Stanford University Press. P. 176

Gernet, Jacques 1962. Daily

Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250-1276. Tr. H. M.

Wright. Stanford:

Stanford University Press

Latham,

Ronald 1958 “Introduction” to Marco Polo The

Travels. New York: Penguin.

Modelski, George 2003 World Cities: –3000 to

2000. Washington, DC: Faros 2000

Morris,

Ian. 2013 The Measure of Civilization. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

http://ianmorris.org/docs/social-development.pdf

Mungello, D.E. 1994 The

Forgotten Christians of Hangzhou. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Needham, Joseph Shorter science and civilization in china_

pp. 241-2 refers to the Hang-chou Fu Chih

[Hang-zhou Fu Zhi] a

Gazetteer and historical topography of Hangzhou 1687 and reports that a

navigation light on the river dates

from the early Song Dynasty.

Oxford Handbook of Cities in World History “Hangzhou”

Polo, Marco 1992 The Travels

of Marco Polo, 2 vols. New York: Dover, Vol 2: pp 201.

Wikipedia “Hangzhou” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hangzhou#cite_ref-29

Xie, Jing 2016 “Disembodied Historicity: Southern Song

Imperial Street in Hangzhou”

Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 75 No. 2, June

2016; (pp. 182-

200)

http://jsah.ucpress.edu/content/75/2/182