“When north-south relations were east-west:

urban and empire synchrony (500 BCE-1500 CE)”

Christopher

Chase-Dunn, Richard Niemeyer, Alexis Alvarez,

Hiroko

Inoue, Kirk Lawrence and Anders Carlson

Institute for

Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

(v. 3-19-06)

Frederic Teggart’s

Earlier studies have demonstrated a curious interregional synchrony

in the growth and decline of large cities and empires. From about 500 BCE until

about 1500 CE cities and empires in East Asia and the West Asian/Mediterranean

region were growing and declining in the same periods, whereas intervening

To be presented at the 2006 conference

of the International Studies Association, San Diego, March 23, 3:45-5:30 PANEL: The Historical Long-Term. 5006

words

This

paper is available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows16/irows16.htm

The growth and decline patterns of the world’s largest cities and

empires and their changing locations over the past three millennia provide an

important window on world history. Earlier research has repeatedly demonstrated

a fascinating synchrony in the growth/decline phases of largest cities and

empires in East Asia and the West Asian/Mediterranean region (e.g. Chase-Dunn and Willard 1993; Chase-Dunn,

Manning and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and Manning 2002).

Using

data on the population sizes of largest cities and the territorial sizes of

largest empires it has been discovered and repeatedly confirmed that

medium-term growth/decline phases in

Earlier Findings

The population and areal sizes of

human settlements have increased since the emergence of sedentism around 12,000

years ago, and so have the sizes of the largest polities. But these general

long-term trends have been complicated by sequential middle-term declines in

the sizes of the largest cities and empires in all regions where urban and polity

sizes have been studied quantitatively. The population size estimates of both

modern and ancient cities are subject to large errors, and existing

compilations (Chandler 1987; Modelski 2003) badly need to be improved using

better methods of estimation (e.g. Pasciuti and Chase-Dunn 2002). The same can

be said for existing compilations of estimates of the territorial sizes of the

world’s largest empires (Taagepera 1978a, 1978b, 1979, 1997). When these

upgraded estimates become available, the East/West synchrony findings discussed

here will need to be reexamined with the improved data. We believe that the

East/West synchrony finding will be confirmed.

This phenomenon of East/West urban

and empire synchrony in middle-term growth/decline phases has been subjected to

several different methods of analysis, and it holds up across all of them. Both

changes in the size of the largest cities and changes in the steepness of the

city-size distributions have been used. And earlier studies have used two

different kinds of spatial units of analysis: constant regions and expanding

political-military networks (interaction networks of fighting and allying

states). The East/West synchrony has been found with both.

Detrending

is important because the long-term trend for city and empires sizes to increase.

Two different methods of detrending have been used: partial correlation

controlling for year and decadal change scores in which the earlier year is

subtracted from the later year. In the studies of empire sizes, empires that touch

adjacent macro-regions such as the Mongol Empire of the thirteenth century CE

have been removed from the analysis because they build in a degree of synchrony

by appearing in both regions at the same time. The synchrony finding is strong

even when this case has been removed from the calculations.

Frederick

Teggart’s (1939) path-breaking world historical study of temporal

correlations between events on the edges of the Roman and Han Empires argued

the thesis that incursions by Central Asian steppe nomads were the key to

East/West synchrony. An early study of city-size distributions in Afroeurasia

(Chase-Dunn and Willard 1993; see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: 222-223) found

an apparent synchrony between changes in city size distributions and the growth

of largest cities in

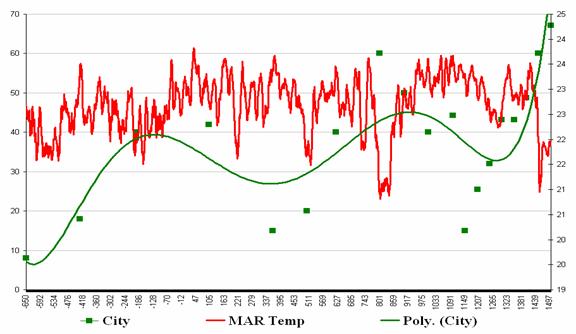

Figure 1: Sizes of Largest cities in

Figure 1: Sizes of Largest cities in

Comparable

other instances of distant systems that came into weak contact with one another

can be found. Within the Old World, the Mesopotamian and Egyptian core

regions were interacting with one another by means of prestige goods exchange

from about 3000 BCE until their political-military networks (state systems)

merged in 1500 BCE. Chase-Dunn, Pasciuti, Alvarez and Hall (2006) have already

examined this case for synchrony and have not found it, though the data on

Bronze Age city and empire sizes are very crude with regard to temporality and

accuracy. It is also possible to study the temporality of rise and fall and

oscillations among distant regions in the

Chase-Dunn,

Alvarez and Pasciuti (2005) also report detrended correlations between constant

regions for total population estimates taken from McEvedy and Jones

(1975). These total population estimates at 100-year intervals show rather high

growth/decline synchronies for several regions, also noted and discussed by

McEvedy and Jones (1975: 343-48).

The

East/West growth/decline synchrony seems to be rather robust, though better

estimates and finer temporal resolution of empire and city sizes might

challenge it. Interregional synchrony can be caused when two cyclical processes

get simultaneously reset, either by the same cause or by different causes. This

could be a one-shot occurrence. Or a process that is similarly cyclical can

cause synchrony. Candidates for the East/West synchrony are: climate change,

epidemic diseases, trade interruptions, or attacks by

Possible Explanations

Climate

change might affect regions by causing growth and decline of agricultural productivity

that in turn affects cities and empires. Perhaps because

But

climate change could also be involved in somewhat more complicated ways.

Central Asian steppe nomads (discussed below) were very susceptible to climate

change because their pastoral economy was greatly affected by changes in

temperature and rainfall. It is possible that climate change in

The

above hypotheses all conceive of climate change as an exogenous variable. But

it is also possible that city and empire growth change the climate. We know

that population growth and the development of complex civilizations changes the

environment by means of deforestation, soil erosion and the construction of

large irrigation systems (Diamond 2005). These changes may have affects on

climate. Modern studies show that the construction of large cities creates an

“urban heat island” that changes the environment in the immediate vicinity and

downwind of cities. Cities ingest and egest water, air and energy, and while

industrial cities do this on a much larger scale, earlier large cities also did

it to some extent. So large-scale agriculture and city-building may be causes

of climate change. Thus climate change may also be an endogenous variable.

We

know that Central Asian steppe nomads who raised horses and sheep periodically

formed large confederacies and attacked the agrarian empires of the East and

the West (Barfield 1989). Famous examples are the Huns and the Mongols. Perhaps

there was a cycle of Central Asian incursions that impacted upon the agrarian

civilizations of the East and the West and that accounts for the synchrony.

We

know that epidemic diseases spread across

We

also know that the Roman and Han empires were linked by long distance trade

routes across the Silk Roads and by sea. Perhaps interruptions to trade, or

periods of greater and easier trade flows, affected the Eastern and Western

civilizations simultaneously.

It

is also possible that two systems that are cycling independently can become

synchronized if they are both reset by a simultaneous accidental shock. This is

the so-called “Moran Effect” known in population ecology. We have discussed

this possibility in Chase-Dunn, Alvarez and Pasciuti (2006).

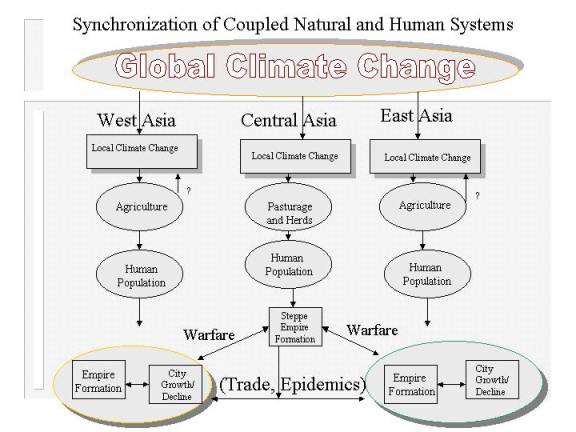

Figure

2 is a propositional inventory that includes most of the possible causes of

East/West synchrony.

Figure 2: Possible Causes of East/West Synchrony

More

research is required to find out which of these possible causes was responsible

for the East/West synchrony. We have found some evidence that temperature

changes in

East Asian Climate Change and Growth/Decline

Phases

We

have located time series data on two indicators of climate change in

The

first indicator we have of climate change from China is an estimate of changes in average temperature that are inferred from

measurements taken of stalagmites formed in the Shihua cave near Beijing (Tan et

al 2003).[2] Ideally

the indicator of climate change should be geographically near the area of city

and empire growth. Recent research on El Nino and the Southern Ocean

Oscillation shows that climate dynamics on a global scale are linked by huge

inter-regional “teleconnections” in which changes in ocean temperature in one

region affect rainfall and temperature in distant other regions, but the

resulting patterns are very different from region to region (Davis 2001). This

means that we need to have information on climate change that is spatially near

to the areas where we are studying the possible impacts. Knowing what happened

in Greenland or

The

estimated temperature series as well as the plots for largest city and largest

polity from 650 BCE to 1800 CE are shown in Figure 3.

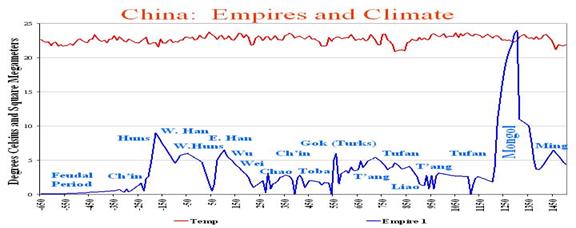

Figure 3: Temperature Change (

Figure 3 graphs the temperature changes inferred

from

Table 1 reveals a significantly steady rate of

empire growth throughout the period, when plotted against DECADE (correlation

is 0.587, p < 0.01). Similarly, the

population of the largest city in

Table 1: Bivariate

and partial correlations: largest city, largest empire, temperature estimate

from

Table 1 also confirms an earlier finding of a

significant bivariate and partial temporal correlation between city and empire

sizes in

The results in Figure 1 and Table 1 are based on only 26

time points because of the paucity of data on city population sizes, which have

been estimated at only very widely-spaced intervals, especially for the earlier

time periods. When we examine the relationship between empire sizes and

temperature change separately we have far better temporal resolution. Figure 4

graphs the empire sizes using ten-year interpolated values and the ten-year

moving average of yearly temperature estimates. The bivariate correlation is

.02.

Figure 4: Largest Empire and Temperature Change in

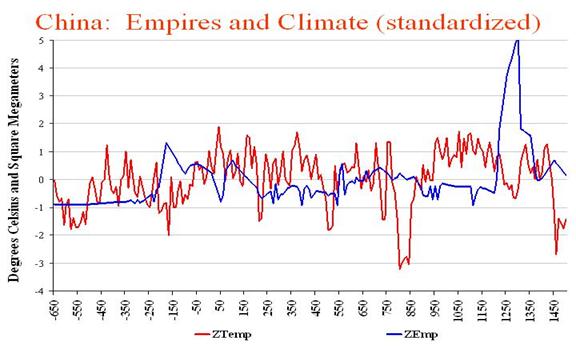

Figure 5 shows the same

relationship, but it is easier to see what is going on because the scores have

been standardized.

Figure 5: East Asian Largest Empires and Average

Temperatures (standardized values)

Figure 6 depicts the relationship between

Figure 6: Largest Cities and Average Temperature with city

polynomial

The

results so far imply that there is no regular relationship between climate

change and the growth/decline phases of cities and empires in

Also

temperature is only one indicator of climate change. Yearly rainfall, the

distribution of rainfall throughout a year, the frequency of large and

destructive storms – all these are important aspects of climate change that may

have large effects on agriculture and irrigation systems but are not well

reflected in temperature changes. It is also possible that climate change near

We also want to examine the possibility of time lags

between climate change and city and empire growth decline phases. The methods

employed above presume a simultaneous causality, whereas it is likely that

changes in climate take some period of time to affect the sizes of cities and

empires. This can be systematically examined using the techniques employed by

Turchin and Korotayev (nd) for studying lagged dynamical relations among time

series variables. We plan to do this in the next version of our research.

Understanding

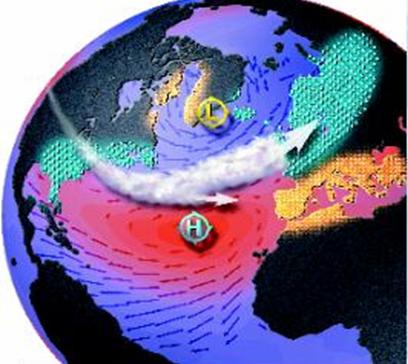

Climate Oscillations in the

Much

of the climate change within

the Mediterranean region is a product of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO),

a hemispheric meridional oscillation in atmospheric mass between the polar

regions near

Figure 7: Atmospheric

regions responsible for North Atlantic Oscillation

http://sciencebulletins.amnh.org/earth/f/nao.20040910/essays/28_1.php

Figure 8: Atmospheric effects and climate results of

the NAO positive phase.

http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/~visbeck/nao/presentation/html/NAO.htm

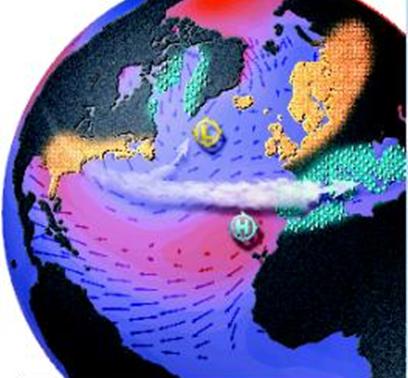

Figure 9: Atmospheric

effects and climate results of the NAO negative phase

http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/~visbeck/nao/presentation/html/NAO.htm

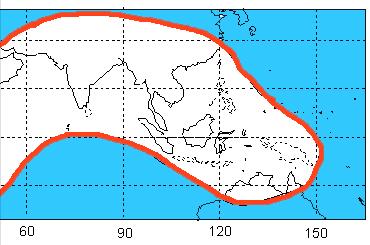

Climate conditions within

Figure 10. Regions affected by the Asian Monsoon

http://daac.gsfc.nasa.gov/atmosphere/dynamics/images/monsoon.qt

Connections

between the NAO and the Asian Monsoon

Recent research has

supposedly established a synchronic connection between regions affected by the

NAO and regions affected by the Asian Monsoon (Wang et al. 2005). Generally speaking, many of the abrupt

climate change events in the paleoclimatology record of the Asian Monsoon

correlate with abrupt climate change in the Mediterranean and

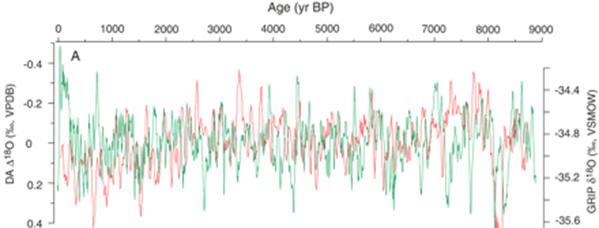

Figure 11:

Comparison of the smoothed (5-point running average) detrended China climate

proxy data (green) with the smoothed 20-year averaged Greenland climate proxy

record (5-point running average, red) over the past 9000 years. The broad

correlations between the

From Wang et al. 2005, http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/308/5723/854

Comparison of

Mediterranean and

Figure 12: Geographic

locations of proxy measures for climate conditions

In order to further examine the hypothesis of

East/West climate synchrony we compared proxy precipitation data from the Red

Sea (Lamey et al. 2006) with

Contrary to the previous research cited above, a

positive correlation between

Figure

13: East/West Estimated Precipitation Oscillations (Sources: Wang et al 2005

and Lamey et al 2006)

With regard to the correlation between the precipitation estimates

from

Figure 14: East Asian

Precipitation and Temperature

The relationship between the

Figure

15:

At

this point we are lacking firm conclusions. There do not appear to be big

climate events in either East or

Bibliography

Alvarez, Alexis 2003

“Cycles of primacy in Afroeurasia: 200-1850 CE” Department of

Sociology,

University of California, Riverside http://home.earthlink.net/~alexisalvarez/propaper.htm

Bairoch, Paul 1988 Cities

and Economic Development: From the Dawn of History to the Present.

Barfield, Thomas J. 1989 The

Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and

Barnes,

Ian, and Robert Hudson. 1998. The History Atlas of

Boyle, Peter. 1977. The

Mongol World Empire, 1206 – 1370.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Alice Willard, 1993 "Systems of

cities and world-systems: settlement size hierarchies and cycles of political

centralization, 2000 BC-1988AD" A paper presented at the International

Studies Association meeting, March 24-27,

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Susan Manning and Thomas D. Hall, 2000 "Rise

and Fall: East-West Synchronicity and Indic Exceptionalism Reexamined"

Social Science History 24,4: 721-48(Winter) .

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Susan Manning, 2002 "City systems and

world-systems: four millennia of city growth and decline," Cross-Cultural

Research 36, 4: 379-398 (November).

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

Alexis Alvarez, and Daniel Pasciuti 2005 "Power and

Size; urbanization and empire formation in world-systems" Pp. 92-113

in C. Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The Historical Evolution of

World-Systems.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher ,

Alexis Alvarez and Daniel Pasciuti, 2005 “World-systems in the

biogeosphere: three thousand years of urbanization, empire formation and

climate change.” Pp. 311-332 in Paul Ciccantell, David A. Smith and Gay Seidman

(eds.) Nature, Raw Materials, and Political Economy.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis Alvarez and Thomas D. Hall 2006 “Growth/decline phases

and semiperipheral development in the ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian

world-systems” Pp. 114-138 in Barry K. Gills and William R. Thompson (eds.) Globalization and Global History.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Thomas D. Hall Forthcoming “Global social change in

the long run” in C. Chase-Dunn and Salvatore Babones (eds.) Global

Social Change.

Christian, David 2004 Maps

of Time.

Cioffi-Revilla, Claudio and David Lai 2001 “Chinese Warfare and Politics in the Ancient East Asian International System, ca. 2700 B.C. to 722 B.C.” International Interactions 26,4: 1-32.

Diamond, Jared 2005 Collapse.

Fagan, Brian 1999 Floods,

Famines and Emperors: El Nino and the Fate of Civilizations.

Basic Books.

Friedman, Jonathan and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2005 Hegemonic Declines: Past and Present.

Gong, Gaofa and Sultan Hameed 1991 “The variation of moisture conditions in China

Lattimore, Owen 1940

Inner Asian Frontiers of

Haywood, John. 1998. Historical Atlas of the Ancient World. Oxforshire, OX: Andromeda Oxford Ltd.

_______

1998. Historical Atlas of the

Classical World. Oxforshire,

OX: Andromeda Oxford Ltd..

_______

1998. Historical Atlas of the

Medieval World. Oxforshire, OX: Andromeda Oxford Ltd..

_______

1998. Historical Atlas of the

Modern World. Oxforshire, OX: Andromeda Oxford Ltd.

Kradin, Nikolay N.. 2002.

“Nomadism, Evolution and World-Systems:

Pastoral Societies in Theories of Historical Development.” Journal of

World-Systems Research, 8,3.

Lamey, Frank, Helge W. Arz, Gerard C. Bond, Andre

Bahr, and Jurgen Patzold. (2006) Multicentennial-scale hydrological changes in

the Black Sea and northern Red Sea during the Holocene and the Artic/North

Atlantic Oscillation Paleoceanography, 21,

PA 1008

Lee, J. S. 1931. “The Periodic Recurrence of Internecine

Wars in

Lee, J. S. (1933) in Studies Presented to Ts’ai Yuan P’ei on His Sixty-fifth Birthday Part I, ed. Fellows and Assistants of the Institute of History and Philology (Institute of History and Philology, Taipei), pp. 157-166.

McEvedy, Colin and

Richard Jones 1975 Atlas of World Population History.

Penguin.

McNeill, William H. 1976 Plagues

and

McNeill, John R. and

William H. McNeill 2003 The Human Web.

Modelski, G. (2003).

World cities: -3000 to 2000.

Modelski, George “Evolutionary World Politics” web site http://faculty.washington.edu/modelski/worldcities.html

Pasciuti, Daniel and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2002 “Estimating the population sizes of

cities.” https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/estcit/estcit.htm

Peregrine,

Peter N. 2005 “Synchrony in the new world: an example of archaeoethnology”

Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Crosscultural

Research, February 23-27, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Taagepera,

Rein 1978a "Size and duration of empires: systematics of size"

Social Science Research 7:108-27.

______

1978b "Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600

B.C." Social Science Research, 7 :180-96.

______1979

"Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 600 B.C. to 600

A.D." Social Science History 3,3-4:115-38.

_______1997

“Expansion and contraction patterns of large polities: context for

Tan,

Ming, Tungsheng Liu, Juzhi Hou, Xiaoguang Qin, Hucai Zhang and Tieying Li 2003

“Cyclic

rapid warming on centennial-scale revealed by a 2650-year stalagmite record of

warm season temperature” Geophysical Research

Letters Vol. 30, No. 12, 1617 (June). http://wdc.cricyt.edu.ar/paleo/pubs/tan2003/tan2003.html

Teggart,

Frederick J. 1939

Turchin,

Peter and Thomas D. Hall 2003 “Spatial synchrony among and within

world-systems: insights from theoretical ecology.” Journal of World-Systems Research 9,1:

37-64.

Turchin,

Peter and Andrey Korotayev n.d. “Population dynamics and internal warfare: a

reconsideration”

http://eclectic.ss.uci.edu/~drwhite/Global/Turchin-Korotayev-plus.pd

Quansheng Ge, Jingyun

Zheng, Xiuqi Fang*, Xueqin Zhang, Piyuan Zhang, Zhimin Man, and

Wei-Chyung Wang “Winter half-year temperature reconstruction for the middle and

lower reaches of the Yellow River and Yangtze River, China, during the past

2000 years.” Holocene 13, 6:933-940, 2003

http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/paleo/pubs/ge2003/ge2003.htmlWang, Shaowu and Wei-Chyung Wang 1994 “Application of historical documentary records in resonstruction of the paleo-climate series in China

Wang, Yongjin, Hai Cheng, R. Lawrence Edwards,

Yaoqi He, Xinggong Kong, Zhisheng An, Jiangying Wu, Megan J. Kelly, Carolyn A.

Dykoski, Xiangdond Li. The Holocene

Asian Monsoon: Links to Solar Changes and

Wu, Xiangding 1994 “Tree-ring chronologies and their response to climate in the Qinling mountains, China Yang, B., Braeuning, A., Johnson, K.R., and Yafeng, S., 2002,“General characteristics of temperature variation in China http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/paleo/pubs/yang2002/yang2002.html

Zhang, Jiacheng and

Thomas J. Crowley 1989 “Historical climate records in China and reconstruction

of past climates” Journal of Climate 2,8: 833-849.

Zhu, Kezhen (Chu,

K.) 1973 "A preliminary study on the climatic fluctuations during the last

5000 years in