Historical

and Contemporary Processes of Global Party Formation From Above and Below

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Ellen Reese

Transnational Social Movement Research Working Group

University of California-Riverside

The new abolitionists

Keywords: political parties, world revolutions, global party

formation, transnational social movements, globalization, hegemony, global

social change, global democracy, World Economic Forum, World Social Forum,

north-south relations

This paper will be presented at the

session on Global Party Formation From Above and Below to be held at the annual

meeting of the International Studies Association, Chicago, Thursday, March 1,

1:45-3:30 pm.

This is IROWS Working Paper # 33 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows33/irows33.htm

v. 2-27-07

7660 words

Abstract: This paper

outlines an approach to the evolution of global governance in the modern

world-system. We discuss the extension of the Westphalian interstate system to

the periphery and the transformations in the institutions and capabilities that

have occurred with the rise and fall of three hegemonies. We also consider the

emergence of international political organizations since the Concert of Europe,

the development of global parties among both elites and non-elites, a series of

world revolutions since the Protestant Reformation and recent developments in

global civil society, the World Economic Forum and the World Social Forum. We

also address recent debates about

All

human societies have polities – authoritative institutions for making group

decisions, regulating conflict and access to scarce resources and for engaging

in relations with other polities. Human polities were originally quite small,

consisting of nomadic hunter-gatherer bands. But polities have gotten larger

and more hierarchical in the course of socio-cultural evolution, and they have

sometimes merged, but most frequently some have engulfed others, such that the

total number has decreased. The long-term rise in size and the decrease in

number suggests an evolutionary trend toward an eventual Earth-wide state,

though the processes of cyclical rise and fall, and only occasional upward

sweeps in the size of largest polities makes it clear that the evolutionary

process is anything but simple and inevitable. Elsewhere we have studied and

theorized about this long-term trend (Chase-Dunn, Inoue, Alvarez Niemeyer and

Sheikh-Mohamed 2007). Here we will focus primarily on the institutional and

structural developments of global governance that have occurred in the modern

world-system during the last 600 years.

The Trajectory of Global Governance and Political Globalization

Global

governance refers to the nature of power institutions in a world-system – a

system of multiple societies. So by this definition there has been global

governance all along. It has not emerged. But it has changed its nature. The

modern world-system was originally politically organized as a European

interstate system in which states allied and fought with one another for

territory, control of trade routes, and other resources. As

The interstate system that emerged

in

The emergence of colonial empires corresponded

with the reproduction of a multicentric core in which several European states

allied with and fought each other. This system came to be taken for granted by

international relations theorists as the natural mode of global governance.

Despite that earlier systems had repeatedly seen the emergence of “universal

states” such as the

The oscillation of earlier systems morphed

into the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers in the modern system. A series

of hegemons emerged from the semiperiphery -- the Dutch, the British and the

The evolution that occurred with the rise and fall of the hegemonic core powers needs to be seen as a sequence of forms of world order that evolved to solve the political, economic and technical problems of successively more global waves of capitalist accumulation. The expansion of global production involved accessing raw materials to feed the new industries, and food to feed the expanding populations (Bunker and Ciccantell 2004). As in any hierarchy, coercion is a very inefficient means of domination, and so the hegemons sought legitimacy by proclaiming leadership in advancing civilization and democracy. But the terms of these claims were also employed by those below who sought to protect themselves from exploitation and domination. And so the evolution of hegemony was a dynamic interaction between the global elites and the global masses. World orders were challenged and reconstructed in a series of world revolutions (Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein 1984; Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000)

Political Globalization and Global Party Formation

The nineteenth century saw the beginning of what we shall

call political globalization – the emergence and growth of an overlayer of

regional and increasingly global formal organizational structures on top of the

interstate system. We conceptualize

political globalization analogously to our understanding of economic

globalization -- the relative strength and density of larger versus smaller

interaction networks and organizational structures (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and

Brewer 2000). The most obvious indication of political globalization is

the evolution of the uneven and halting upward trend in the transitions from

the Concert of Europe to the

The

trend toward political globalization can also be seen in the emergence of the

Bretton Woods institutions (the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank)

and the more recent restructuring of the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade

as the World Trade Organization, and the heightened visibility of other

international fora (the Trilateral Commission, the Group of Seven [Eight].

Some of

the proponents of a recent stage of global capitalism contend that strong

transnational capitalist firms and their political operatives working within

national states have combined with existing international organizations to

constitute an emerging transnational capitalist state (e.g. Robinson 2004).

This version of the global state formation hypothesis claims that a rather

integrated transnational capitalist class has emerged since the 1970s, and that

this global class uses both international organizations and existing national

state apparatuses as coordinated instruments of its rule. A related perspective

holds that the

An internationally

integrated global capitalist class was also in formation in the second half of

the nineteenth century, but this did not prevent the world polity from

descending into the violent interimperial rivalry of the two twentieth century

World Wars (Barr et al 2006). The

degree of integration of both elites and masses is undoubtedly greater in the

current round of globalization, but will it be strongly integrated enough to

allow for readjustments without descent into a repetition of the Age of

Extremes? That is the question.

In addition to the formation of regional and global

international organizations, the nineteenth and twentieth centuries also saw

the emergence of transnational social movements and the enlargement of what has

come to be known as global civil society.[1]

These have also altered the form of global governance by providing expanded

arenas in which individuals and organizations participate directly in world

politics rather than through the mediating shell of national states.

Specialized international and transnational non-governmental organizations

(e.g. the International Postal Union) exploded in the middle of the 19th

century (Murphy 1994). Abolitionism, feminism and the labor movement became

increasingly transnational in nature.

Earlier local movements had also had a transnational aspect because

sailors, pirates, slaves and indentured servants carried ideas and

sentiments back and forth across the

Atlantic (Linebaugh and Rediker 2000), but the large global consequences of

these movements resulted when many mainly local developments (e.g. slave

revolts) occurred synchronously or within the same time period.

The

Black Jacobins of the Haitian revolution, by depriving Napoleonic France of

important sources of food and wealth, played a role in the rise of British

hegemony (Santiago-Valles 2005). These kinds of effects of resistance from

below became stronger in the middle decades of the 19th century –

the years around the world revolution of 1848.

This is usually thought of in terms of developments in Europe, but

millenarian and revolutionary ideas traveled to the New World to play a role in

the “burned over district” in upstate

These developments ramped up during the Age of Extremes,

the first half of the twentieth century.

Internationalism in the labor movement had emerged in the second half of

the nineteenth century. Global political

parties were becoming active in world politics, especially during and after the

world revolution of 1917. The Communist International (Comintern) convened

large conferences of representative from all over the globe in

The Comintern was abolished in 1943, though the

The Bandung Conference in 1954 was an important forum in

which the leaders of the emerging nations explicated

Contemporary

Contestation in World Politics

While

transnational social movements date back to at least the Protestant

Reformation, the scope and scale of international ties among social activists

have risen dramatically over the past few decades, as they have increasingly

shared information, conceptual frameworks and other resources, and coordinated

actions across borders and continents (Moghadam 2005). In the 1980s and 1990s,

the number of formal transnational social movement organizations (TSMOs) rose

by nearly 200 percent. While TSMOs are

still largely housed in the global north, a rising portion are located in, and

have ties to, the global south; the number of TSMOs with multi-issue agendas

increased significantly, from 43 in 1983 to 161 in 2000 (Smith 2004). This rise in transnational organizing

contributed to, and helped to produce the global justice movement. The global justice movement is a “movement

of movements,” that includes all those who are engaged in sustained and

contentious challenges to neoliberal global capitalism, propose alternative

political and economic structures, and mobilize poor and relatively powerless

peoples. While this movement resorts to non-institutional forms of collective

action, it often collaborates with institutional “insiders,” such as NGOs that

lobby and provide services to people, as well as policy-makers (Tarrow 2005;

Keck and Sikkink 1998). The global justice movement includes a variety of

social actors and groups: unions, NGOs, SMOs, transnational advocacy networks,

as well as policy-makers, scholars, artists, journalists, entertainers and

other individuals.

Two important sections of

global civil society and transnational activism are: (1) The participants in

the World Economic Forum (WEF), who tend to see neo-liberal corporate

globalization as a positive development, and (2) those that identify with the

global justice movement and attend the World Social Forum (WSF). The WSF and

the WEF represent two rather different slices of global civil society and may

presage a new era in global party formation and political contention over the

future of world society (Carroll 2006a,2006b; Chase-Dunn and Reese forthcoming).[2]

The organizational forms, discourses, and goals are intentionally different,

with the WSF being a popular alternative to the “leadership” focus of the

WEF. And yet some of the discourse and

goals of the two forums overlap, and some individuals and organizations

participate in both.

The

WEF was established in 1971 as a non-partisan independent international

organization committed to improving the state of the world by engaging leaders

in partnerships to shape global, regional and industry agendas.[3]

The WEF maintains a headquarters in

Ulrich

Beck’s (2005) effort to rethink the nature of power in a globalized world makes

the claim that the power of global capitalist corporations is based mainly on

the threat of the withdrawal of capital investment, and thus it does not need

to be legitimated. Beck further argues that the transnational capitalist class

does not need to form political parties, because its power is translegal and

does not need legitimation. While this may be true to some extent, it is still

the case that one may discern an evolution of political ideology that is

promulgated by the lords of capital and the states that represent them. The Keynesian national development project

that was the hegemonic ideology of the West from World War II to the 1970s was

replaced by neoliberalism, a rather different set of claims and policies.

William Carroll (2006a, 2006b) traces the history liberalism and neoliberalism

as it emerges from the eighteenth century, takes hiding in monastery-like think

tanks during the heyday of Keynesianism, and then reemerges as

Reaganism-Thatcherism in the 1970s and 1980s. The further evolution can be seen

in the rise of the neoconservatives in the 1990s, and concerns for dealing with

those pockets of poverty that seem impervious to market magic in the writings

of such neoliberals as Jeffrey Sachs (2005). Stephen Gill’s (2000) suggestive

discussion of “the post-modern prince” – a left global political party emerging

out of the global justice movement, also proposes an analysis of corporate

media, think-tanks, and institutions such as the World Economic Forum as

participants in a process of global political contestation. Necessary or not,

the transnational capitalist class and its organic intellectuals engage in

efforts to legitimate its own power, and this can be seen to interact with

popular forces. Thus did the advertised concerns of the World Economic Forum

shifted considerably after the rise of the World Social Forum.

The World Social Forum (WSF)

was established in 2001 as a counter-hegemonic popular project focusing on

issues of global justice and democracy.[5]

Initially organized by the Brazilian labor movement and the landless peasant

movement, the WSF was intended to be a forum for the participants in, and

supporters of, grass roots movements from all over the world rather than a

conference of representatives of political parties or governments. The WSF was

organized as the popular alternative to the WEF. The WSF has been supported by

the Brazilian Workers Party, and has been most frequently held in

Some have claimed that the pattern of hegemonic rise and fall is now morphing into a new

structure of core condominium (Goldfrank 1999) while others see the rise of the

neoconservatives in the United States as a repetition of the pattern of

“imperial overstretch” that may portend another period of contentious

interimperial rivalry. Several outcomes are possible, including a repeat

of what happened after the last decline of a hegemon -- another world war among

core states (Chase-Dunn and Podobnik 1995). The current crisis of the

world-system seems fraught with several possible, and potentially interactive,

dangers of collapse – huge international and growing within-nation

inequalities, ecological disaster, what would appear to be an unsustainable

trade and investment imbalance, and a huge mountain of debt structured as

“secure” claims on future profit streams.

Manifestos

Galore in the World Revolution of 20xx

It is in this context that a new world revolution is brewing.

The movement of movements at the World Social Forum is in the midst of a

manifesto/charter writing frenzy as those who seek a more organized approach to

confronting global capitalism and neoliberalism attempt to put workable

coalitions together (Wallerstein 2007).

One issue is whether or not the World Social Forum itself

should formulate a political program and take formal stances on issues. The

Charter of the WSF explicitly forbids this and a significant group of

participants strongly supports maintaining the WSF as an “open space” for

debate and organizing. A survey of 625 attendees at the World Social Forum

meeting in

But this is not necessary. The WSF Charter also

encourages the formation of new political organizations. So those participants

who want to form a new global political organization are free to act, as long

as they do not do so in the name of the WSF as a whole.

In recent Social Forum meetings, “Assemblies of Social Movements”

and other groups have issued calls for global action and other political

statements. At the end of the 2005 meeting in

At present there is an impasse between those who are willing

to risk charges of Napoleonism and those who want proposals and totemic texts

to bubble up from the movements. And there are also important disagreements

about both goals and tactics. Such political statements, particularly those

issued by the 19 notables in 2005 and the Bamako Appeal, have generated

considerable controversy about process and legitimacy, since they were issued

by socially privileged and unelected leaders, mainly intellectuals, who claim

to speak on behalf of the “masses.” Creating democratic mechanisms of

accountability through which WSF participants can engage in global collective

action and move towards greater political unity remains an important political

task.

The

issue of process is strongly raised in several of the critiques of the Bamako

Appeal in a collection of documents published just before the World Social

Forum meeting in Nairobi in January of 2007 (Sen et al 2007). This

collection includes the Communist Manifesto, documents that came out of the

Bandung Conference, recent communiqués from the Zapatistas in

The

Multicentric Network of Movements

Just as world revolutions

in the past have resulted in restructuring world orders, it can be presumed

that the current one will also do this. But do the activists themselves agree

on the nature of the most important problems, visions of a desirable future or

notions of appropriate tactics and forms of movement organization? We performed

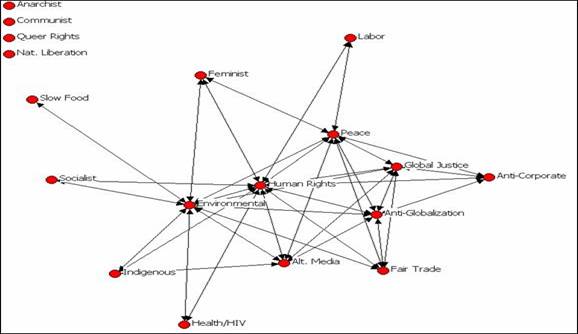

a network analysis of movement ties based on the responses to the 2005 WSF

Survey.[6] Our

study of the structure of overlapping links among movements as represented by

attendees of the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre in 2005 who identify with

and/or are actively involved in a long list of movements shows that the

structure of movement overlaps is a multicentric network (Chase-Dunn, Petit,

Niemeyer, Hanneman, Alvarez, Gutierrez and Reese 2006). Human rights, anti-war,

alternative media, anti-globalization and environmental movements are strongly

linked with one another and are bridges to almost all the other movements (See

Figure 1).  Figure 1: The network of WSF

movement linkages

Figure 1: The network of WSF

movement linkages

Figure 1 shows the network structure produced by

examining the patterns of those who say they are actively involved in

movements. All the movements have some people who are actively involved in

other movements. In order to compare the relative sizes of linkages among

movements we eliminate connections that are below the average number of

linkages.

The overall structure of the network of movement linkages

shows a multicentric network organized around four main movements that serve as

bridges that link other movements to one another” peace, global justice, human

rights and environmental. While no single movement is so central that it could

call the shots, neither is the network structure characterized by separate

cliques of movements that might be easily separated from one another. Remember

that Figure 1 does not show all the connections in the network but rather shows

those connections that are significant in size relative to all the connections

in the network.

This structure means that

the transnational activists who participate in the World Social Forum process

share goals and support the general global justice framework asserted in the

World Social Forum Charter. It also means that this group is relatively

integrated and is not prone to splits. A Third Worldist and cosmopolitan united

front approach that pays attention to the nature of this network structure can

have reasonable hope for mobilizing a strong force for collective action in

world politics, though solutions need to be found to address the issues of

process that have become apparent in the first wave of manifesto-writing.

North-South Issues

The

focus on global justice and north/south inequalities and the critique of

neoliberalism provide strong orienting frames for the transnational activists

of the World Social Forum. But there are difficult issues for collective action

that are heavily structured by the huge international inequalities that exist

in the contemporary world-system and these issues must be directly confronted.

A survey of the attendees of the 2005 World Social Forum found several

important differences between activists from the core, the periphery and the

semiperiphery (Chase-Dunn, Reese, Herkenrath,

Alvarez, Gutierrez, Kim, and Petit. Forthcoming).

Those

from the periphery were fewer, older, and more likely to be men. In addition,

participants from the periphery were more likely to be associated with

externally sponsored NGOs, rather than with self-funded SMOs and unions, as

NGOs have greater access to travel funds. Southern respondents were significantly

more likely than those from the global

north to be skeptical toward creating and

strengtheningor reforming global-level political

institutions and to favor the abolition of global institutions.

Those

who favor reforming or replacing global institutions in order to resolve global

problems (see discussion of Monbiot below) need to squarely face these facts.

This skepticism probably stems from the historical experience of peoples from

the non-core with colonialism and global-level institutions that claim to be

operating on universal principles of fairness, but whose actions have either

not solved problems or have made them worse. These new abolitionists are posing

a strong challenge to both existing global institutions and to those who want

to reform or replace these institutions. These realities must be addressed, not

ignored.

Democratizing

Global Governance

Ideas

of democracy that are deeply institutionalized in modern societies are being

increasingly applied at the global level, raising issues about the democratic

nature of existing institutions of global governance. Why are some countries

allowed to have weapons of mass destruction while others are not? How have

these decisions been made? Are the institutions and actors that made them

legitimate in the eyes of the peoples of the world?

Ann Florini (2004) acknowledges the need for

democratic global governance processes to address global issues that simply

cannot be dealt with by separate national states. Florini contends that global

state formation is impossible, undesirable and would engender huge opposition

from all quarters. Instead she sees a huge potential for democratizing global

governance through uses of the Internet for mobilizing global civil society.

Florini and many others point out that existing institutions of global

governance have a huge democratic deficit. The most important and powerful

elective office in the world is that of the U.S. presidency, but only citizens

of the United States can vote for contenders for this office. Thus is existing

global governance illegitimate even by its own rules..

George Monbiot’s Manifesto

for a New World Order (2003) is a reasoned and insightful call for

radically democratizing the existing institutions of global governance and for

establishing a global peoples’ parliament that would be directly elected by the

whole population of the Earth. Ulrich Beck’s (2005) call for “cosmopolitan

realism” also ends up supporting the formation of global democratic

institutions. Monbiot also advocates the establishment of a trade clearinghouse

(first proposed by John Maynard Keynes at Bretton Woods) that would reward

national economies with balanced trade, and that would use some of the

surpluses generated by those with trade surpluses to invest in those with trade

deficits. He also proposes a radical reversal of the World Trade Organization

regime, which imposes free trade on the non-core but allows core economies to

engage in protectionism – a “fair trade organization” that would help to reduce

global development inequalities. Monbiot also advocates abolition of the U.N.

Security Council, and shifting its power over peace-keeping to a General

Assembly in which representatives’ votes would be weighted by the population

size of their country.

And Monbiot advocates global enforcement of a carbon

tax and a carbon swap structure that would reduce environmental degradation and

reward those who utilize green technologies.

Monbiot also points out that the current level of indebtedness of

non-core countries could be used as formidable leverage over the world’s

largest banks if all the debtors acted in concert. This could provide the

muscle behind a significant wave of global democratization. But in order for

this to happen the global justice movement would have to organize a strong

coalition of the non-core countries that can overcome the splits that tend to

occur between the periphery and the semiperiphery. This is far from being a utopian

fantasy. It is a practical program for

global democracy.

Upward

sweeps of city and polity growth have led to new levels of political

integration in the past (Chase-Dunn, Inoue, Alvarez, Niemeyer and

Sheikh-Mohamed 2007). What are the prospects for another upward sweep that

would result in the formation of a real global state? It is generally the case

that increases in organizational complexity and hierarchy require the

appropriation and control of greater amounts of energy (Christian 2003). The

last big upward sweep of city sizes and colonial empires was greatly

facilitated by the harvesting of fossil fuels that stored the sunlight and heat

of billions of years of photosynthesis and the storage of concentrated energy

below the surface of the Earth.

New energy

technologies will eventually emerge that can facilitate new levels of human

complexity, but in the mean time we will have to deal with the negative

anthropogenic environmental consequences of this colossal harvest of energy,

the coming of “peak oil” and the eventual exhaustion of the fossil fuel

stores. It would be reckless to bet on a

“technological fix” that will arrive in time to allow us to continue to rely on

the existing institutions of global governance. Thus the processes of political

globalization, the growth of transnational activism, and the potentials for

democratizing global governance that we have discussed above are needed to

manage the huge issues that are on the immediate horizon: the interimperial

rivalry between a declining U.S. economic hegemony and the rise of East Asia,

the timely achievement of demographic stability as the non-core moves on from

an industrial death rate and an agricultural birth rate to the demographic

transition, the transition to a sustainable relationship with the biosphere and

the geosphere, and the reduction of global inequalities.

The global

democracy movement is global state formation from below, whether or not it is

politic to say so. Perhaps it would be better to call it “multilateral global

governance.” Hopefully the

The European

Union process itself only creates a larger core state that can contend with the

References

Aguirre,

Adalberto and Ellen Reese. 2004. “The Challenges of Globalization for Workers:

Transnational and Transborder Issues.” Special Issue: Justice for Workers in

the Global Economy, edited by Adalberto Aguirre and Ellen Reese. Social Justice: A Journal of Crime,

Conflict, and World Order. 31(2).

Amin, Samir. 2006. “Towards the fifth international?” Pp. 121-144

in Katarina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Democratic Politics Globally. Network Institute for Global

Democratization (NIGD Working Paper 1/2006),

Arrighi, Giovanni. 2006. “Spatial and other ‘fixes’ of

historical capitalism” Pp. 201-212 in C., Chase-Dunn and Salvatore Babones

(eds.) Global Social Change: Historical

and Comparative Perspectives.

Bamako Appeal 2006 http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/bamako.html

Barr, Kenneth,

Shoon Lio, Christopher Schmitt, Anders Carlson, Kirk Lawrence,

Jonathan

Krause, Yvonne Hsu, Christopher Chase-Dunn

and Thomas E. Reifer 2006 “Global

Conflict and Elite Integration in the 19th

and Early 20th Centuries” IROWS Working Paper #27 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows27/irows27.htm

Boswell, Terry and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2000. The Spiral of Capitalism and Socialism:

Toward Global Democracy.

Beck, Ulrich 2005 Power in

the Global Age.

Bunker, Stephen and Paul

Ciccantell 2004 Globalization and the Race for Resources.

Buzan, Barry and Richard

Little 2000 International Systems and World History.

Byrd, Scott C. 2005. “The

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Christine Petit, Richard

Niemeyer, Robert A. Hanneman, Rebecca Alvarez, Erika Gutierrez and Ellen Reese

2006 “The Contours of Solidarity

and Division Among Global movements” IROWS Working Paper # 26 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows26/irows26.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Ellen Reese

Forthcoming “Global party formation in world historical perspective” in

Katarina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Global Party Formation. London

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Ellen Reese,

Mark Herkenrath, Rebecca Giem, Erika Guttierrez, Linda Kim, and Christine

Petit. 2007 [forthcoming]. “North-South

Contradictions and Bridges at the World Social Forum,” in NORTH AND SOUTH IN THE WORLD POLITICAL ECONOMY, edited by Rafael

Reuveny and William R. Thompson. Blackwell.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Hiroko Inoue, Alexis Alvarez, Richard Niemeyer and Hala

Sheikh-Mohamed 2007 “Global state formation in world historical perspective”

IROWS Working Paper #32. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows32/irows32.htm

della Porta, Donatella. 2005. “Making the Polis: Social Forums and

Democracy in the Global Justice Movement.”

Mobilization. 10(1): 73-94.

Florini, Ann 2005 The Coming Democracy: New Rules for Running A

Fisher, Dana R. Kevin Stanley, David Beerman, and

Gina Neff. 2005. “How Do Organizations Matter? Mobilization

and Support for Participants at Five Globalization Protests.” Social

Problems. 52: 102-121.

Fisher,

William F. and Thomas Ponniah (eds.).

2003. Another World is Possible: Popular Alternatives to Globalization at the

World Social Forum.

Gowan,

Peter 2006 “Contemporary intracore relations and world systems theory” Pp. xxx

in C. Chase-Dunn and S. Babones (eds.) Global Social Change.

Giem, Rebecca L. and Erika J. Gutierrez. 2006. “The

Politics of Representation in the World Social Forum: Preliminary Findings”

Presented at the World Congress of Sociology,

Joint

Session of RC02 and RC07: Alternative Visions of World Society: Global Economic Elites and Civil Society in Contestation.

Durban , South Africa

July 28.

Gill, Stephen 2000 “Toward

a post-modern prince? : the battle of Haas,

Peter. "Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy

Coordination," International Organization, vol. 46, no. 1. 1992

Held,

David and Anthony McGrew. 2002. Globalization/Antiglobalization.

Kaldor,

Mary 2003 Global Civil Society: An Answer to War.

Keck,

Margaret E. and Katherine Sikkink. 1998. Activists

Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics.

Linebaugh, Peter

and Marcus Rediker. 2000. The Many-Headed

Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary

Moghadam,

Valentine 2005 Globalizing Women.

University Press.

Monbiot, George

2003 Manifesto for a

Murphy, Craig

1994 International Organization and

Industrial Change: Global

Governance

since 1850.

Patomaki, Heikki and

Teivo Teivainen. 2006. “Epilogue: Beyond the Political Party/Civil Society

Dichotomy,” Pp. 180-188 in Democratic

Politics Globally: Elements for a Dialogue on Global Political Party Formations,

edited by Katarina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila.

--------------------------------------------------.

2004. “The World Social Forum: an open space or a movement of movements,” Theory, Culture and Society 21,6:

145-154.

Reese,

Ellen, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Mark Herkenrath, Christine Petit, Linda Kim and

Darragh White. 2006. “Alliances and Divisions in the Global Justice Movement:

Survey Findings from the 2005 World Social Forum,” Presented at the annual

meeting of the American Sociological Association in

Roberts,

J. Timmons and J. Bradley Parks 2006 A

Climate of Injustice: Global Inequality, North-South Politics

and Climate Policy.

Robinson, William R. 2004. A Theory of Global Capitalism. Baltimore , MD : Johns Hopkins University Sachs, Jeffrey 2005 The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities For Our Time. New York

Santiago-Valles,

Kelvin. 2005. “World historical ties among “spontaneous” slave rebellions in

the

Scholte, Jan Aart. 2004. “Civil Society and

Democratically Accountable Global Governance.” Government and Opposition 39(2):211-233.

Sehm-Patomaki, Katarina and Marko Ulvila (eds.). 2006. Democratic Politics Globally: Elements for a

Dialogue on Global Political Party Formations.

Sen, Jai and Madhuresh Kumar with Patrick

Bond and Peter Waterman 2007 A Political Programme for the World Social Forum?:

Democracy, Substance and Debate in the

---------------.

2005. “

Smith,

Jackie, Marina Karides, et al. forthcoming [2007]. The World Social Forum and the Challenges of Global Democracy.

Starr,

Amory. 2000. Naming the Enemy: Anti-corporate Movements Confront Globalization.

Sworakowski,

Witold S. 1965. The

Communist International and Its Front Organizations.

Tarrow, Sidney.

2005. “The Dualities of Transnational Contention: ‘Two Activist

Solitudes’ or a

Teivainen, Teivo. 2004.

“Dilemmas of Democratization in the World Social Forum.”

Institute for World Systems Research,

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984. “The

three instances of hegemony in the history of the capitalist world-economy.”

Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and Research in

Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology,

Vol. 37.

________________ 2007 “The World Social Forum:

from defense to offense” http://www.sociologistswithoutborders.org/documents/WallersteinCommentary.pdf

Waterman, Peter 2006 “Toward a Global Labor

Charter Movement?” http://wsfworkshop.openspaceforum.net/twiki/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=6