Comrades-in-Arms?:

Socialists and Communists at the World Social

Forum

Bridgette Portman

Sociology 240A

v. 8/3/08, 7440 words

Activists march in a parade during the US Social Forum

in

![]()

UCR

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

Paper presented at the Critical Sociology

conference on “Power and Resistance: Critical Reflections, Possible Futures,”

This is IROWS Working Paper #38 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows38/irows38.htm

The

World Social Forum and the related “global justice movement” are generally

considered to be novel phenomena, creative forms of opposition to the relatively

novel process of neoliberal capitalist globalization. This paper asks to what extent older social

movements – specifically, socialist and communist movements – are involved in

the World Social Forum and the global justice movement. How have these older, and some would say

Western-centric, movements responded to the “new” Social Forum process centered

in the global South, and to the “family of movements” involved in it

(Wallerstein 2004a, 634)? Are there

significant cleavages between socialists and communists and other global

justice activists in terms of demographics, group affiliations, or issue

opinions? If so, what implications might

such cleaveages suggest for the future of the global justice movement?

This paper is divided into several sections. First, the World Social Forum and its

connection to the global justice movement will be discussed. Evidence will be presented that indicates that

socialists and communists may be a peripheral rather than a central part of this

movement. Then results will be presented

from an analysis of survey data collected at the 2005 World Social Forum held

in

The World Social Forum and the Global Justice Movement

The World Social Forum (WSF) is an annual congregation

and meeting space for a wide variety of social movements, including

environmentalists, workers, feminists, gay rights activists, indigenous groups,

and human rights activists, united in – if nothing else – their opposition to

neoliberal capitalist globalization. The

WSF was first held in

I said, “We need a symbolic rupture with

everything Davos stands for. That has to

come from the South.

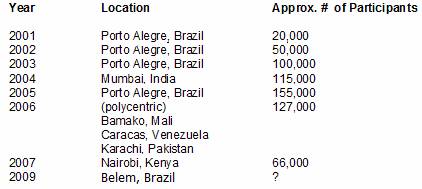

Since 2001 the WSF has become

an annual event and has been held in

The

WSF prides itself on the fact that it is organized differently from many other

entities: it is an “open space” in which social movements and activists can

exchange knowledge and ideas in a decentralized, non-hierarchical fashion. According to the Charter of Principles

developed by the WSF International Council (2001, #8), “The World Social Forum

is a plural, diversified, non-confessional, non-governmental and non-party context

that, in a decentralized fashion, interrelates organizations and movements

engaged in concrete action at levels from the local to the international to

build another world.” Indeed, plurality

and diversity are the WSF’s organizing logic.

At each Forum numerous organizations hold workshops focused around

specific themes or topics. There are

also events, such as parades and the “Assembly of Social Movements,” that

involve large numbers of Forum members collectively, but for the most part the

WSF remains quite decentralized.

Although criticisms of this structure will be discussed later, many

activists see these organizational principles as beneficial.

The

WSF has been described as an outgrowth or manifestation of a wider movement

opposed to the consequences of neoliberal capitalist globalization. This movement has many

names: the “global justice

movement,” the “anti-globalization movement,” the “alter-globalization

movement,” the “anti-capitalist movement,” the “family of anti-systemic movements.” In the words of the WSF itself, it is the “global movement for social justice and solidarity” (Call of

Social Movements 2002, #11). In

reality, it is not a single movement, but

Table 1:

World Social Forums[1]

encompasses a wide variety of

different social movements, including “women, people

of color, indigenous people, homosexuals, oppressed nationalities, immigrants,

students, youth, the elderly, ecological groups, cultural movements, [and] landless and homeless

populations” (Leite 2005, 39). The WSF describes

this amalgamation in the following way:

We are diverse -- women and men, adults and youth, indigenous peoples,

rural and urban, workers and unemployed, homeless, the elderly, students,

migrants, professionals, peoples of every creed, colour and sexual

orientation. The expression of this

diversity is our strength and the basis of our unity. We are a global solidarity movement, united

in our determination to fight against the concentration of wealth, the

proliferation of poverty and inequalities, and the destruction of our earth.

(Call of Social Movements 2002, #2)

The global

justice movement – as this paper will refer to it – is generally thought of as

a new phenomenon, having arisen to counter the relatively new phenomenon of

neo-liberal globalization.[2] Its somewhat shallow roots extend back to the

1999 anti-WTO protests in

Socialists and Communists within the WSF and Global Justice Movement

Given the purported

“newness” of the WSF and global justice movement, what is its relationship to “old”

leftist movements, such as socialists and communists, who have a much longer

history of resisting global capitalism?

On the one hand, “old” social movements – including socialists,

communists, anarchists, and labor advocates – have played an undeniable part in

the WSF process. According to Walden

Bello, it is useful to think of the WSF and the global justice movement as “a

mix of the old and the new”:

You have the coming together of different

streams: the Marxists influence the stream, there is an ecological

environmental stream, the feminist stream, the radical developmentalist stream

and what is interesting is the interaction of all these streams both

theoretically and politically. There has

been a creative cross-fertilisation of the different traditions. (ctd in Ashman

2004, 148)

Socialist and communist

groups have organized panels and workshops at the WSFs. At the United States Social Forum (USSF) in

A Workshop at

However, relative to the WSF and the global justice movement

overall, socialist and communist views are not necessarily central.

For

some, socialism is still an adequate designation, however abundant and

disparate the conceptions of socialism may be.

For the majority, however, socialism carries in itself the idea of a

closed model of a future society, and must, therefore, be rejected. They prefer other, less politically charged

designations, suggesting openness and a constant search for alternatives…according

to some, the idea of socialism is West-centric and North-centric… (113-14).

It could be that

some Forum participants avoid identifying themselves with “socialism” or

“communism” for strategic reasons, while still accepting the ideas associated

with those ideologies. They might

instead frame their arguments around the idea of workers’ rights or social

justice. This seems plausible given a

conversation between two activists that took place at a workshop organized by

Solidarity at the USSF:[3]

Older Woman: Anytime you

say you’re a socialist, people say – you know, they come up with what sound

like clichés, but they’re serious – they say, “that’s never worked, how could

that work?”

Younger Woman: Don’t say

it.

Older Woman: Well, but if

you’re a member of the organization…

Younger Woman: I think that the working class in the United States

is just not radical enough to quite relate, and so I’m just saying to get to

their issues, talk about their issues, and we can save the other things

[socialism] for another day…don’t get hung up on it.

There is no evidence,

however, that the majority of Forum-goers do indeed accept the fundamental

elements of socialist and communist ideology, at least in its classical Marxist

incarnation. On the contrary, Waterman

(2005) notes that “the WSF opposes itself or distances itself (or is autonomous from) the

state-national, the inter-state institution, political parties, militarism and

insurrection, institutionalized unionism, from Marxism, socialism and

class-struggle (at least as the primary motive force of history)” (45). This rejection of economics as the primary

determinant of social life is evident in the WSF Charter of Principles, which

states that “the World Social Forum is

opposed to all totalitarian and reductionist views of economy, development and

history” (#10). Leite argues that “While a large number of forum participants identified with

some form of socialism, the majority was very distant from any type of

tradition linked to the international socialists of the twentieth century”

(96). And Waterman (2005) argues that

even labor issues in general have taken a somewhat peripheral role at the

Forum:

Within the context of the WSF, if not possibly also of the GJ&SM

[global justice and solidarity movement] more generally, labour and labour

struggles have never been a major theme, nor a cross-thematic issue. Labour questions have been typically presented

either in the largely ossified form of the traditional unions…or as separate

issues concerning worker rights, women workers, migrants, rural labour, land

reform, the social economy, etc. (46)

Some well-known leftist scholars have

chimed in on this issue. World-systems

scholar Immanuel Wallerstein (2004a) argues that the WSF is an embodiment of a

new “family” of anti-systemic movements that is opposed in fundamental ways to

the “old left” – specifically, communist, social democratic, and national

liberation movements. In particular, he

argues that the “new left” eschews the old left’s strategy of utilizing state

power to achieve reforms, is skeptical of political parties, and rejects the

idea that the conflict between capital and labor is the most important source

of exploitation in society. Given that

these are concepts associated with classical Marxism and communism, one would

expect that many members of the “new left” would not associate themselves with

those older movements. Additionally,

Marxist author Alex Callinicos (2003) is careful to distinguish socialism from

the rest of the anti-capitalist movement (his term for the anti-globalization or

global justice movement). According to

Callinicos, “The distinctive character

of the contemporary anti-capitalist movement reflects its emergence in an

ideological climate defined by the apparent triumph of liberal capitalism and

the eclipse of Marxism” (84). He goes on

to note that “supporters of the FI [the Trotskyist Fourth International] from

both Latin America and Europe have been heavily involved in the World Social

Forms at Porto Alegre,” but that “they remain very much a minority force,” and

that “the idea that socialism is the alternative to capitalism has as yet

little currency in the movement, in the North at least” (85).

Some

socialist and communist groups have expressed criticism of the WSF specifically

because it is not socialist enough.

At the 2004 WSF in India, this took the form of the “Mumbai Resistance”

(MR), a gathering of radical Maoist groups that was intended as an alternative

and challenge to the WSF – although it garnered only

about two percent of the turnout witnessed at the WSF (Wallerstein 2004b). According

to Ching (2004), an attendant at the MR,

MR 2004 has criticized the WSF for

promoting the idea of “another world is possible” without actually explaining

the content of that world. MR 2004 has pointed out that the WSF has pinned

peoples’ hope on a vague and abstract world that does not have any concrete meaning.

MR also believes that another world is

possible and the future world MR 2004 pursues has very precise content: a world

advancing toward socialism. (335)

MR also criticized the WSF for its

exclusion of political parties and groups that use violence. Another criticism comes from communist P. J.

James (2004):

The so-called ‘pluralism’ advocated by

the WSF, its close affinity to ‘new social

movements’ (NSMs), and its hatred

towards class movements, all have wider ideological ramifications. Their roots

lie deep in the post-Marxist prognosis on the decline or disappearance of the

working class as a revolutionary force and the ascendancy of NSMs and NGOs as

the “new revolutionary subject of history.” (248)

In addition, a common critique offered

by socialists and communists is that the WSF’s decentralized, non-political structure and failure to plan or advocate

specific actions has rendered the Forum nothing more than “talking shop.” Rather than an “open space,” these groups

would like to see the WSF become something more organized and agentive. “Our overall aim must to be create a new world

political organisation,” writes the League for the Fifth International (2006),

“whose declared objective is to bury capitalism and imperialism once and for

all, and build another world - a socialist one.”

It

is probably partly the perceived failure of “socialism” in

The

Social Forum that we’re at is overwhelmingly people of color and young

people. We don’t reflect that and it’s a

problem for us. And I think it’s a

problem in terms of the conversation that we’re having because most people at

the Social Forum, if they ask, ‘how are we going to rebuild a movement in the

Given

these issues, this paper asks the following question: To what extent have socialist and

communist activists become part of this “new” global justice movement, and

particularly the WSF process? Are there

significant cleavages between them and other Forum participants in terms of

demographics, issue opinions, and group affiliations?

Methods

This paper

draws upon survey data collected from participants at three different Social Forums:

the Fifth WSF, held from January 26-31,

2005, in

The

Check

all of the following movements with which you:

(a)

strongly identify: (b)

are actively involved in:

oAlternative media/culture oAlternative media/culture

oAnarchist oAnarchist

oAnti-corporate oAnti-corporate

oAnti-globalization oAnti-globalization

oAlternative

Globalization/Global Justice oAlternative

Globalization/Global Justice

oHuman

Rights/Antiracism oHuman Rights/Antiracism

oCommunist oCommunist

oEnvironmental oEnvironmental

oFair

Trade/Trade Justice oFair Trade/Trade Justice

oGay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender/

Queer Rights oGay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender/Queer

Rights

oHealth/HIV oHealth/HIV

oIndigenous oIndigenous

oLabor oLabor

oNational

Sovereignty/National Liberation oNational Sovereignty/National

Liberation

oPeace/Anti-war oPeace/Anti-war

oFood

Rights/Slow Food oFood Rights/Slow Food

oSocialist oSocialist

oWomen's/Feminist oWomen's/Feminist

oOther(s),

Please list ________________ oOther(s), Please list _______________

Figure 1: List of social movements on the 2005 survey

at

identifying with or being actively involved in any

movement. Since I was interested in how

socialists and communists differ from other activists, I felt it would

be inappropriate to include those individuals – such as researchers,

journalists, and curious bystanders – who were attending the forums for reasons

other than movement affiliation. This

left 562 respondents in the

Hypotheses

I have divided my analysis into three

sections: demographic factors, opinions, and affiliations with groups and

movements. In terms of demographics, I

expect that H1: socialists and communists will be older, on average, than

other Forum attendants. This makes

sense given that the movements themselves are older; older individuals would

likely have joined the movements prior to the collapse of the

In terms of issue opinions, I predict that H6: socialists

and communists will be more radically anti-capitalist than the other Forum

attendants: they will be more likely to want to abolish capitalism rather

than reform it, and also more likely to want to abolish the economic

institutions of global capitalism – the IMF, the WTO, and the World Bank. I also expect that H7: they will be more

supportive of the idea of world government.

This follows from socialism’s universalist aspirations; to quote the Communist

Manifesto, “the working-man has no country.” Also, congruent with the criticism posed by

some socialist and communist groups that the WSF is not “political” enough, I

expect that H8: socialists and communists will be less supportive than other

Forum-goers of the organization of the WSF as a nonpolitical, decentralized

“open space.”

Regarding group

affiliations, I expect that H9: socialists and communists will be more

likely than other Forum attendants to be affiliated with labor unions,

given socialism’s focus on labor as the agent of progressive change. I also predict that H10: they will be more

likely to be affiliated with political parties, given the nature of

socialism as a very political ideology centered around the use of state power

to achieve societal change, and the fact that there are a great many socialist

and communist parties in existence (as opposed to, say, feminist parties, or

parties centered around other movements).

Findings

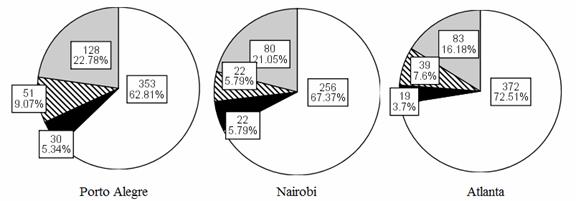

Altogether there were 403

socialists and 183 communists in the sample (Figure 2). The striped area in Figure 2 represents the

overlap – 112 people identified with both communism and socialism. Due to the relatively small overlap, I

thought it would be appropriate to separate my analysis of socialists from my

analysis of communists. Hence, the two

groups are treated individually. Figure

3 breaks down the percentage of socialists and communists by meeting site.

Two things are immediately noticeable. First, as expected, socialism and communism

are not

Figure

2: Socialists and communists as a

percentage of total sample

Figure 3: Percentage of socialists and communists by

meeting

dominant affiliations among participants at the Forum;

two-thirds of the sample identify with neither socialism nor communism. Second, in accordance with H5, socialists and

communists comprise a smaller percentage of the sample in

Demographics

A logistic regression

was run to determine the probability that a respondent would indicate being a

socialist, using meeting site, gender, race, age, and years of education as

predictive factors. Table 2 presents the

results. As

hypothesized, there was a statistically significant partial effect of meeting

location: The odds of being a socialist at the WSF in

When

the same regression was run for communists (Table 3), only gender had a

statistically significant partial effect.

Men were 1.55 times as likely to be communists than were women.

|

Predictor |

B |

Wald c2 |

P |

Odds Ratio |

|

Meeting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.345 |

4.469 |

.035 |

1.412 |

|

|

.329 |

3.108 |

.078 |

1.390 |

|

Gender |

.389 |

8.305 |

.004 |

1.476 |

|

Education |

-.182 |

1.626 |

.202 |

.833 |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

25

and under |

.154 |

.879 |

.348 |

1.167 |

|

26

to 35 |

-.044 |

.069 |

.793 |

.957 |

|

Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

Black/African |

-.399 |

4.147 |

.042 |

.671 |

|

Latino/Hispanic |

-.050 |

.043 |

.836 |

.951 |

|

Mixed or other |

-.185 |

1.260 |

.262 |

.831 |

Table 2:

Results of logistic regression predicting socialism from meeting

location, gender, education, age, and race/ethnicity

|

Predictor |

B |

Wald c2 |

P |

Odds Ratio |

|

Meeting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.065 |

.090 |

.765 |

1.068 |

|

|

-.014 |

.003 |

.957 |

.986 |

|

Gender |

.440 |

5.781 |

.016 |

1.552 |

|

Education |

-.329 |

2.994 |

.084 |

.719 |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

25

and under |

.355 |

2.493 |

.114 |

1.427 |

|

26

to 35 |

.284 |

1.545 |

.214 |

1.329 |

|

Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

Black/African |

.009 |

.001 |

.970 |

1.009 |

|

Latino/Hispanic |

.195 |

.598 |

.439 |

1.216 |

|

Mixed or other |

.213 |

.452 |

.502 |

1.237 |

Table 3:

Results of logistic regression predicting communism from meeting

location, gender, education, age, and race/ethnicity

Issue Opinions

A number of

crosstabulations were performed to determine whether socialists and communists

differed from other Social Forum participants in their opinions on issues

related to globalization and capitalism.

The prediction that socialists and communists would be more radically

anti-capitalist than other activists was largely supported. Both socialists and communists were more likely

to prefer abolishing capitalism over reforming it (Table 4). Given that the abolishment of capitalism and

its replacement by some form of collective ownership of the means of production

is the quintessential socialist goal, this is not surprising. What

may be more interesting is that a sizeable minority of both socialists and

communists advocated reforming capitalism rather than replacing it. Because socialism and communism by definition

seek the replacement of capitalism, it would seem that these inconsistent

attitudes need to be explained. This

matter will be re-examined in the Discussion. In addition, both socialists and

|

Reform or Abolish

Capitalism? |

Socialist |

Non-Socialist |

Communist |

Non-Communist |

|

Reform it |

32.4% |

48.0% |

22.1% |

46.7% |

|

Abolish it |

67.6% |

52.0% |

77.9% |

53.3% |

|

|

Χ2 = 26.58

p < .001 |

Χ2 =

36.85 p < .001 |

||

Table 4

|

World Bank |

Socialist |

Non-Socialist |

Communist |

Non-Communist |

|

Reform it |

28.6% |

39.9% |

21.7% |

39.0% |

|

Abolish it or Replace it |

71.4% |

60.1% |

78.3% |

61.0% |

|

|

Χ2 = 8.26

p = .004 |

Χ2 =

10.33 p = .001 |

||

Table 5

communists were more likely to want to abolish or

replace, as opposed to reform, the World Bank (Table 5).[7] They were also more likely to want to abolish

or replace the IMF, but this reached significance only for socialists (χ2 = 5.00, p =.025). On the other hand, communists, but not

socialists, were significantly more likely to want to abolish or replace the

WTO (χ2 = 3.91,

p =.048). Also

as expected, both socialists and communists were more likely to disagree with

the idea that the Social Forum should remain a nonpolitical “open space” and

not take positions on issues. However,

this was just shy of significance for communists (see Table 6).[8] Finally, contrary to my prediction,

neither socialists nor communists were more likely than other Forum attendees

to support the idea of world government.

Roughly 40% of both socialists and communists felt that a democratic

world government was a good idea and possible to achieve, a slightly but not

significantly larger proportion than the rest of the sample.

|

WSF should remain open

space |

Socialist |

Non-Socialist |

Communist |

Non-Communist |

|

Agree |

50.0% |

58.1% |

47.5% |

56.9% |

|

Disagree |

50.0% |

41.9% |

52.5% |

43.1% |

|

|

Χ2 = 4.95 p = .026 |

Χ2 =

3.70 p = .054 |

||

Table 6

Group and Movement Affiliations

H10

predicted that socialists and communists would be more likely to be affiliated

with a political party. This was confirmed

(Table 7), although roughly three-fourths of both socialists and communists did

not indicate having a party affiliation. Socialists and communists were also more

likely to be union affiliates (Table 8), although this was just shy of

significance for communists.

|

Political party

affiliation |

Socialist |

Non-Socialist |

Communist |

Non-Communist |

|

Yes |

23.2% |

8.6% |

25.2% |

10.9% |

|

No |

76.8% |

91.4% |

74.8% |

89.1% |

|

|

Χ2 = 49.72 p < .001 |

Χ2 =

25.67 p < .001 |

||

Table 7

|

Union affiliation |

Socialist |

Non-Socialist |

Communist |

Non-Communist |

|

Yes |

26.0% |

15.8% |

24.1% |

17.8% |

|

No |

74.0% |

84.2% |

75.9% |

82.2% |

|

|

Χ2 = 17.75 p < .001 |

Χ2 =

3.53 p = .060 |

||

Table 8

The final

factor at which I looked was whether socialists and communists were affiliated

with other social movements at the WSF and USSF. I coded a participant as an affiliate of a

given social movement if he or she checked “strongly identify” and/or “actively

involved” next to that movement on the survey.

Because there was no limit on the number of movements a subject could

check, many people were “synergists,” or affiliates of more than one

movement. I wondered whether socialists

and communists would be affiliated with fewer movements than others, which

would indicate that they formed a relatively insular group at the Forum. In fact, nearly all socialists and communists

in the sample were synergists – only four socialists were affiliated with

socialism alone, and only three communists were affiliated with communism

alone. The median number of movements with

which socialists and communists were affiliated was 10. Since the surveys at each meeting contained a

different number of total movements from which respondents could choose, it may

be more meaningful to break down the results by meeting (Table 9).

It appears that both socialists and communists are well connected with

other movements at the Forum.

|

|

Socialista |

Communistb |

Total # of movements on

survey |

|

|

8 |

9 |

18 |

|

|

10.5 |

9.5 |

27 |

|

|

14 |

13 |

27 |

a Including “socialist” and excluding “other”

b Including “communist” and excluding “other”

Table 9: Median number of social movement affiliations

for socialists and communists

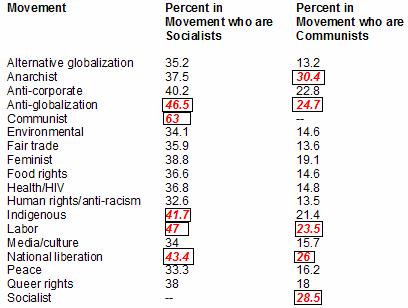

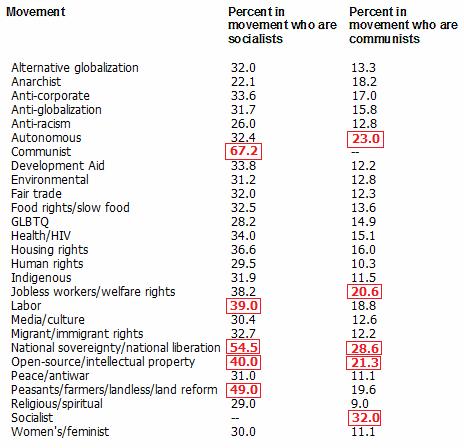

Table 10 displays the percentage of individuals in

each movement at

Table 10 (

Table 11 (

socialists and communists was anti-globalization,

understandable if globalization is identified with the rule of global

capital. On the other hand, socialists

and communists were not as centrally involved in “newer” social movements like

health/HIV, queer rights, media/culture, environmentalism, and feminism. One unexpected finding was the connection

between communism and anarchism; given the history of sometimes very bitter

ideological conflict between communists and anarchists, it seems strange that

nearly one third of the individuals identifying with anarchism in the

Table 11

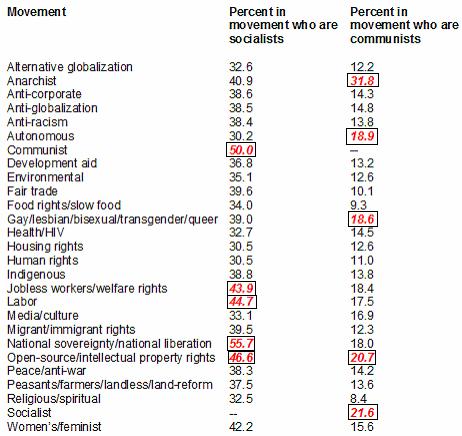

displays the results for the

Finally,

the results for the USSF in

Table 12 (

To

summarize, socialism and communism do not seem to be isolated movements at the

WSF. Rather, the vast majority of these

individuals were also members of other movements. Chief among these are the labor and national

liberation movements, which are generally considered “old” movements and which

have historical ties to socialism. Socialists

and communists may find it easier to relate to these movements than to the

“new” social movements – like environmental, feminist, or gay and lesbian

rights – which do not generally focus on economic issues as a primary source of

exploitation.

Discussion

Table 13

presents a summary of this paper’s findings.

Overall, I found partial support for my hypotheses. In terms of demographics, socialists and

communists were significantly more likely to be male than female. Whether this reflects the historical concern

of socialism with the predominately male working class, and whether women tend

to be drawn instead to other movements, such as feminism, that they percieve as

more conducive to their interests, is a question for further study. On the other hand, in terms of age,

educational attainment, and race/ethnicity, socialists and communists generally

mirrored the rest of the sample – with the exception that socialists (but not

communists) were more likely to be white rather than black.

Finally, as expected, there were fewer socialists and

communists at the USSF in

Turning to issue opinions, results were

also mixed. On the one hand, socialists

and communists were more radically anti-capitalist than were other activists at

the Forum, as evidenced by their preference to abolish rather than reform

capitalism and capitalist institutions.

|

Supported |

H2: Socialists and

communists will be more likely to be male H6: Socialists and

communists will be more radically anti-capitalist than the other Forum

attendants H10: Socialists and

communists will be more likely to be affiliated with political parties |

|

Partially Supported |

H3: Socialists and

communists will be more likely to be white [black individuals were less

likely to be socialists, but not less likely to be communists] H8: Socialists and

communists will be less supportive of the WSF as an “open space” [This was

significant for socialists only] H9: Socialists and

communists will be more likely to be affiliated with labor unions [This

was significant for socialists only] H5: Socialists and communists will constitute a

smaller percentage of total Forum attendees at the USSF than they will in |

|

Not Supported |

H1: Socialists and

communists will be older, on average, than other Forum attendants H4: The average level of

educational attainment for socialists and communists will be lower than that

of other Forum attendants H7: Socialists and

communists will be more supportive of the idea of world government |

Table 13: Summary of findings

On the other hand, they were not more likely than other

activists to support the idea of world government. In fact, a majority of them felt that a

democratic world government was either a bad idea or a good but implausible

idea. Socialists, but not communists,

were less supportive of maintaining the Social Forum as a nonpolitical “open

space.” While a majority of other Forum

attendants supported the idea of open space, socialists were evenly split on

the issue.

Finally,

regarding group affiliations, both socialists and communists were more likely

than other activists to be members of political parties, and socialists were

more likely to be union members. They

were connected to other movements at the Forum and did not form an isolated

group, although they tended to have more ties to the classical allies of

socialism – labor and national liberation movements – than to newer movements

like feminism or environmentalism.

The overall results of this analysis

suggest that while socialists and communists are not a dominant part of the WSF

process, and while they have some differences with other Forum participants

regarding issue opinions and group affilations, these differences do not seem

to be overwhelming. This could be

considered good news for the global justice movement. Of course, caveats are in order. First, the fact that socialists and

communists do not seem to be significantly different from other WSF

participants cannot be taken to mean that this is true for socialists and

communists in general. This

analysis looked at a self-selected sample of socialists and communists – those

who decided to participate in the Forum.

It could be that socialists and communists who did not go to the

Forum, such as those who attended the Mumbai Resistance instead, differ in

significant ways from those who were surveyed here. Recall the finding that a considerable

minority of socialists and communists surveyed indicated that they believed

capitalism should be reformed rather than abolished. Perhaps this is evidence that these

individuals were not strongly attached to socialism and communism or did not

have a sophisticated understanding of the ideologies. This might also explain why a considerable

number of communists were affiliated with anarchism; perhaps they did not

understand either ideology well enough to recognize the contradictions between

the two.

It is also

likely that “socialism” and “communism” have different meanings for different

people. For instance, one person might

associate socialism with a classless society and abolition of the market, while

another might have a more moderate definition focused around stronger rights

for workers or reducing economic inequality – more of a social democratic than

a truly socialist outlook. The latter

definition is probably more likely among people from countries that have large

established socialist parties. For

example, some individuals in

That said, these findings

may still be considered “good news” for those supporters of the WSF and the

global justice movement, such as Wallerstein, who hope that this new “family of

social movements” can muster enough internal solidarity – despite all its

pluralism – to be a force for change. Perhaps

it is true that, in the words of Cassen (2003) “A global constellation is

coming into being that is beginning to think along the same lines, to share its

strategic concepts, to link common problems together, to forge the chains of a

new solidarity” (59).

References

Ashman, S. (2004). Resistance to neoliberal

globalization: a case of “militant particularism”?

Politics, 24(4), 143-153.

“Call of social movements.”

(2002). In J. C. Leite (2005), The World Social Forum: strategies of

resistance (pp. 187-195).

Callinicos, A. (2003). An anti-capitalist manifesto.

Cassen, B. (2003). On the attack. New Left Review, 19,

41-60.

Chase-Dunn, C. (1998). Global formation: structures

of the world economy. Rowman &

Littlefield.

Ching, P. (2004). Critical views of the World Social

Forum – from Mumbai Resistance.

Inter-Asia Cultural

Studies, 5(2), 331-335.

Giugni, M.,

Bandler, M., and Eggert, N. (2006). The global justice movement: how far does

the classic social movement agenda go in explaining transnational contention? United

Nations Research Instititute for Social Development, Civil Society and

Social Movements Programme Paper Number 24.

IBASE. (2007). World

Social Forum: An x-ray of participation in the policentric forum 2006,

James, P. J. (2004). The World Social Forum’s “many

alternatives” to globalisation. In Jai Sen, Anita

Anand, Arturo Escobar, & Peter Waterman (eds.) (2004), World Social Forum:

challenging empires (pp. 246-250).

Kitschelt, H. (1986). Political opportunity structures

and political protest: Anti-nuclear

movements in four

democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 16, 57-85.

League for the Fifth International. (2006). 2006 World

Social Forum meets in three

centres. Online at

<http://www.fifthinternational.org/index.php?id=14,366,0,0,1,0>

Leite, J. C. (2005). The

World Social Forum: strategies of resistance.

Books.

March, L., & Mudde, C. (2005). What’s left of the

radical left? The European radical left

after 1989: decline and

mutation. Comparative European Politics, 3, 23-49.

Reese, E., Herkenrath,

M., Chase-Dunn, C., Giem, R., Guttierrez, E., Kim, L., & Petit, C.

North-South contradictions and bridges at the World Social Forum. Forthcoming

in Rafael Reuveny and William R. Thompson (eds.) North and South in the

world political economy. Available online at

<http://www.irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows31/irows31.htm>

globalization (part 1).

Paper presented at the XXIV International Congress of the Latin American

Studies Association. Online at <http://www.choike.org/documentos/wsf_s318_sousa.pdf>

--------. (2006). The rise of the global left: the

World Social Forum and beyond.

Zed Books.

Tarrow, S. (1994). Power in movement: Social

movements, collective action and politics.

Wallerstein,

---------. (2004a). The dilemmas

of open space: the future of the WSF. International Social

Science Journal, 56.182,

629–637.

--------- . (2004b).

The rising strength of the World Social Forum. Commentary No. 130,

Waterman, P. (2002). Reflections on the 2nd World

Social Forum in

left internationally?

Working Paper Series No. 362, Institute of Social Studies,

----------. (2003). The global justice and solidarity

movement and the World Social Forum: a

backgrounder. In Jai Sen,

Anita Anand, Arturo Escobar, & Peter Waterman (eds.) (2004), World

Social Forum: challenging empires (pp. 55-66).

----------. (2005). The

old and the new: dialectics around the Social Forum process. Development,

48(2), 42-47.

World Social Forum International Council. (2001). WSF

charter of principles. Online at

<http://www.forumsocialmundial.org.br/main.php?id_menu=4&cd_language=2>