Stability and Change in the contours of Alliances Among movements in the social forum process

Christopher Chase-Dunn and Matheu Kaneshiro

Department of Sociology and Institute for Research on World-Systems (IROWS)

University of California-Riverside, Riverside, CA 92521

Draft v. 7-24-08 5243 words

Korean drummers at the Opening March at the United States Social Forum in Atlanta

Abstract: This paper compares survey results of attendees at the World Social Forum meeting in Porto Alegre in 2005 with surveys from the WSF07 in Nairobi and the United States Social Forum in 2007 in Atlanta to study continuities and changes in the alliances among transnational social movements. Respondents indicated their active involvement in a list of eighteen social movements. Around 60% of respondents indicted active involvement in two or more movements and from these choices we can see which movements share individual activists and we can infer the structure of alliances among the movements. Since we have results over a 2 ½ year period and from social forum meetings in very different locales we can use formal network analysis to examine continuities and changes in the structure of alliances. A main problem of the problem of the paper will be to disentangle differences that may be due to the very different meeting sites from differences that are due changes over time in the structure of movement alliances.

To be presented at the Critical Sociology Conference on “ POWER AND RESISTANCE: CRITICAL REFLECTIONS, POSSIBLE FUTURES” The Boston Park Plaza Hotel & Towers, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, August 3, 2008.Session title: “THE SOCIAL FORUM PROCESS AND GLOBAL SOCIAL CHANGE.” This is IROWS Working Paper #44 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows44/irows44.htm

This paper examines changes in the organizational space of the transnational social movements that are involved in the World Social Forum (WSF) process. In this study we seek to understand the structure of connections among progressive transnational movements and how those connections may be evolving over time. For this purpose we analyze results obtained from surveys of participants in the WSF in 2005 in Porto Alegre, the WSF in 2007 in Nairobi and the U.S. Social Forum (USSF) that was held in Atlanta in 2007.[1] We examine the contours of the social movement connections found among WSF participants, and how these may be changing over time. The tricky problem is that our findings probably reflect other things as well as changes in the structure of the network of popular movements in the global public sphere. Undoubtedly the locations of the meetings, the nature of the groups that sponsored the meetings, and the somewhat different purposes of the meetings, also influence the network structures that emerged at each meeting. We shall try to sort out these different elements affecting the structure of alliances.

There is a large scholarly literature on networks, coalitions and alliances among social movements (e.g. Carroll and Ratner 1996; Krinsky and Reese 2006; Obach 2004; Reese, Petit, and Meyer 2008; Rose 2000; Van Dyke 2003). Our study is theoretically motivated by this literature as well as by world-systems analyses of world revolutions (Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein 1989; Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000) and Antonio Gramsci’s analysis of ideological hegemony, counter-hegemonic movements and the formation of historical blocks [see also Carroll and Ratner(1996) and Carroll (2006a, 2006b)].

Social movement organizations may be integrated both informally and formally. Informally, they are connected by the voluntary choices of individual persons to be active participants in multiple movements. Such linkages enable learning and influence to pass among movement organizations, even when there may be limited official interaction or leadership coordination. In the descriptive analysis below, we assess the extent and pattern of informal linkage by surveying attendees at the WSF. At the formal level, organizations may provide legitimacy and support to one another, and strategically collaborate in joint action. The extent of formal cooperation among movements within “the movement of movements” both causes and reflects the informal connections.

The extent and pattern of linkages among the memberships and among the organizational leaderships of social movement organizations may be highly consequential. Some forms of connection [e.g. “small world” networks, (Watts 2003)] allow the rapid spread of information and influence; other forms of connection (e.g. division into “factions” by region, gender, or issue area) may inhibit communication and make coordinated action more difficult. The ways in which social movements are linked may facilitate or obstruct efforts to organize cross-movement collective action. Network analysis can reveal whether or not the structure of alliances contains separate subsets with only weak ties, or the extent to which the network is organized around one or several central movements that mediate ties among the other movements.

The World Social Forum Surveys

We used previous studies of the global justice movements by Starr (2000), Fisher and Ponniah (2003) and Petit (2004) to construct a list of social movements that we believed would be represented at the January 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The eighteen movements that we studied in 2005 are listed in Table 1 below. At the WSF in Nairobi, Kenya we used most of these same movements, but we separated human rights from anti-racism and we added nine additional movements (development, landless, immigrant, religious, housing, jobless, open source, and autonomous, and this same larger list was used at the USSF in Atlanta in July of 2007. Most of our results use only the original list of 18, with human rights and anti-racism combined as they were in the 2005 survey.

We asked participants which of these movements they strongly identified with, and with which were they actively involved. Our surveys also focussed on the social characteristics of participants, their political activism, and their political views (see Reese et al 2008). The six-page survey asked participants’ opinions on a set of questions designed to capture the main political divisions within the global justice movement described in previous research (Byrd 2005; Brecher, Costello, and Smith 2002; Starr 2000; Fisher and Ponniah 2003; Teivainen 2004). In 2005 we collected a total of 639 surveys in three languages: English, Spanish, and Portuguese.[2]

Although we were unable to survey all linguistic groups, we sought to ensure that we had a broad sample of WSF participants; we conducted our survey at a wide variety of venues, including the registration line, the opening march, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez’s speech (which drew tens of thousands), various kinds of thematic workshops, solidarity tents at multiple locations, outdoor concerts, and the youth camp. Our survey of attendees at the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre is not a perfectly representative sample, though we tried to make it as representative as possible given the limitations of collecting responses during the meetings.

Participation in Social Movements at the 2005 World Social Forum

The size distribution of the eighteen movements in terms of number of participants who say they are actively involved is shown in Table 1.

|

|

number of selections |

% of total selections |

|

alternative media/culture |

133 |

10% |

|

anarchist |

20 |

2% |

|

anti-corporate |

43 |

3% |

|

anti-globalization |

68 |

5% |

|

global justice |

81 |

6% |

|

human rights/anti-racism |

161 |

12% |

|

communist |

32 |

2% |

|

environmental |

142 |

11% |

|

fair trade |

67 |

5% |

|

queer rights |

37 |

3% |

|

health/HIV |

52 |

4% |

|

indigenous |

48 |

4% |

|

labor |

72 |

6% |

|

national liberation |

38 |

3% |

|

peace |

113 |

9% |

|

slow food |

38 |

3% |

|

socialist |

87 |

7% |

|

feminist |

66 |

5% |

|

Total Responses |

1298 |

100% |

|

Number of Respondents |

560 |

|

Table 1: total numbers and percentages of movements selected as actively involved at the 2005 WSF

The size distribution of movement selections in Table 1 shows that the highest percentages of selections were made of human rights/anti-racism (12%), environmental (11%), alternative media/culture (10%) and peace (9%). Some activists have refused to participate in the World Social Forum (or have held counter-events) and some others (those advocating armed struggle) are excluded by the WSF Charter. These factors might account for the small numbers of some of the movements (e.g. anarchists and communists). It is said that anarchists do not fill out questionnaires, but we had very few refusals and 20 of our respondents indicated that they are actively involved anarchists.

We also analyzed the responses to the question about “strong identification” with movements to compare these with the “actively involved” question shown in Table 1. More than twice as many people indicate “identification” as opposed to “active involvement”, but the relative percentages are very similar, and the network results (below) on the identification matrix are also very similar to those found for active involvement. The UCINet QAP routine for correlating two network matrices produces a Pearson’s r correlation coefficient of .909 between the identification and active involvement matrices.[3]

Patterns of Linkage among the Social Movements

We employed two different approaches to analyzing the structure of connections among the movements at the WSF05: bivariate correlations and formal network analysis. First we examined the Spearman’s rank-order correlations among the pairs of movements in which respondents said they are actively involved. These correlations tell us how frequently the participants in one movement had similar profiles of participation in other movements. That is, are participants in one particular movement (e.g. anarchism) more likely (positive correlation) or less likely (negative correlation) to participate in another particular movement (e.g. environmentalism). The correlations among movements are based on the patterns of choices of those 418 respondents who said that they were involved in two or more movements.

Of the 153 unique correlations (18*17/2) there are only seven that are negative, and these are small and not statistically significant. That is, there is an overwhelming tendency for solidarity; participation in one movement almost always makes participation in any other more likely – albeit to highly varying degrees. Seventy-eight of the correlations were positive and statistically significant at the .01 level. The correlations are not high. The largest correlation is .488 between the anti-globalization and the anti-corporate movements. The other rather significant positive correlations (above .3) are anti-corporate/alternative globalization; anti-corporate/peace; and queer rights/health-HIV.

We worried that the presence of respondents who had not checked any of the movements might be lowering the correlations and reducing significance levels, and that some of these might be from incomplete questionnaires rather than real responses to the questions. Indeed 24% (135) of the respondents checked none of the movements as ones in which they were actively involved (see Table 2 below). But our fears were allayed by the fact that respondents were far more likely to have checked at least some movements with which they strongly identified. Only 1.3% (8) of the questionnaires had no movements selected as strongly identified. This means that almost all of the 112 respondents who checked no movements as those in which they were actively involved were actually reporting a real situation and our results for the involvement matrix should be accurate.

Network analysis is superior to bivariate correlation analysis because it allows the whole structure of a network to be analyzed including all the direct and indirect links and non-links. This makes it possible to identify cliques or factions within a network and to examine the centrality or peripherality of network nodes – in this case social movements.

In order to use network analysis we must choose a “cut-off” point that defines strong versus less strong ties among movement pairs. We selected a tie strength cut-off of one-half of a standard deviation above the mean number of movement interconnections to define a “strong” linkage. Using this cutoff, we display the “strong ties” among the movements in Figure 1.

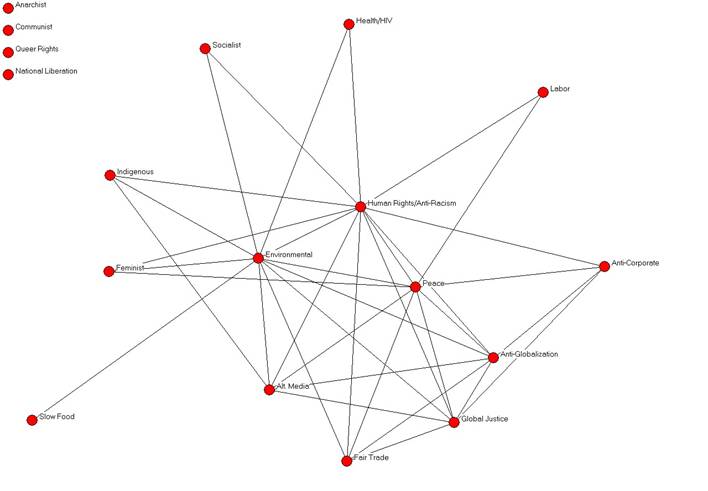

Figure 1: The network of movement linkages at the 2005 WSF in Porto Alegre

Even with this rather high cutoff all of the movements are connected by only one degree of separation, except for the anarchists, communists, queer rights and national liberationists. They are not included in the network graph because they fall below the dichotomization point in terms of movement connections using the one-half of a standard deviation above the mean cut-off. But the matrix of all ties has no empty cells, so even these movements that are less strongly tied are not really true isolates.

Figure 1 shows the centrality of Human Rights/Anti-Racism and Environmental movements in the network of transnational social movements represented at the World Social Forum in 2005. It also indicates that the Peace, Alternative Media, Anti-Globalization and Global Justice movements are rather central. These six movements are major“hubs” or an “inner circle”. But the overall structure is multicentric with not very large differences in network centrality among the most central six. This pattern is not very hierarchical. No single movement is the most “inclusive” or a “peak organization” for all of the others.

Comparisons of WSF2005 with WSF2007 and USSF 2007

We have repeated the network analyses above using the results of our surveys in Nairobi in 2007 and Atlanta in 2007. The purpose of these comparisons is to examine the question of stability and change in the network of transnational social movements participating in the social forum process, and to look for differences that might indicate changes or that might stem from the fact that the meetings were held in different locations and were organized under rather different circumstances and with varying degrees of support from the host governments. Brazil is a semiperipheral country in Latin America. Kenya is a peripheral country in East Africa. The United States is the reigning hegemon of the global system. Porto Alegre has been a strong-hold of the Brazilian Workers Party that has been an important source of support for the establishment and continuation of the World Social Forum. The 2005 meeting in Porto Alegre was attended by Brazilian President Lula and Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez.

The World Social Forum was held in 2007 in Nairobi in order to hold an important global-level meeting in Africa, but the Nairobi government was not very sympathetic with the political goals of the social forum process. Rather the government seemed to see the event as an opportunity to increase tourism. The whole tenor of the meeting was affected by this. More conservative groups, especially religious ones, were prominent at the Nairobi meeting. This gathering was also greatly affected by the fact that a large proportion of the attendees were Africans. The United States Social Forum in Atlanta in July of 2007 was explicitly intended by the WSF International Committee to be organized by, and intended for, grass roots movement within the United States. Global and national NGOs and national unions were allowed to participate but they did not play a central role in organizing the meeting. The “internal Third World” and women were important as both organizers and participants in the USSF. These differences, as well as purely geographical factors, probably played a role in shaping the differences that we find in the structure of movement networks across the three meetings.

|

|

WSF2005 |

|

WSF2007 |

|

USSF2007 |

|

|

# of movements actively involved |

# of respondents |

percent |

#of respondents |

percent |

# of respondents |

percent |

|

0 |

135 |

24.1 |

129 |

29.9 |

120 |

21.6 |

|

1 |

123 |

21.9 |

59 |

13.7 |

89 |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

93 |

16.6 |

73 |

16.9 |

68 |

12.3 |

|

3 |

69 |

15.3 |

52 |

12.1 |

55 |

9.9 |

|

4 |

37 |

6.6 |

36 |

8.4 |

71 |

12.8 |

|

5 |

30 |

5.4 |

29 |

6.7 |

47 |

8.5 |

|

6 |

23 |

4.1 |

16 |

3.7 |

24 |

4.3 |

|

7 |

13 |

2.3 |

11 |

2.6 |

22 |

4 |

|

8 |

10 |

1.8 |

6 |

1.4 |

18 |

3.2 |

|

9 |

2 |

0.4 |

6 |

1.4 |

16 |

2.9 |

|

10 |

2 |

0.4 |

5 |

1.2 |

10 |

1.8 |

|

11 |

3 |

0.5 |

2 |

0.5 |

4 |

0.7 |

|

12 |

2 |

0.5 |

3 |

0.7 |

2 |

0.4 |

|

13 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0.7 |

2 |

0.4 |

|

14 |

2 |

0.5 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0.5 |

|

15 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.2 |

1 |

0.2 |

|

16 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0.4 |

|

17 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.2 |

|

Totals(2 or more) |

544 (286) |

|

431 (243) |

|

555 (346) |

|

Table 2: Number of movements in which respondents say they are actively involved

Table 2 above shows that the percentage of the respondents that did not check any of the eighteen movements to indicate active involvement varied from 22% in Atlanta to 30% in Nairobi. In Porto Alegre it was 24%. Recall that we also asked respondents to check those movements with which they strong identified. Only about 2% checked no movements with which they were strongly identified, so we think that the question about active involvement acted as a high bar that was respected by respondents. From 14% (Nairobi) to 22% (Porto Alegre) indicated that they were actively involved with only one movement, and from 54% (Porto Alegre) to 62% (Atlanta) said they were actively involved in two or more movements. In Nairobi it was 56%. The correlations among movements and the network connections that we are studying are based entirely on the patterns of choices of those respondents who said that they were actively involved in two or more movements. Whereas few respondents indicated that they were actively involved in more than eight movements, more significant numbers indicated involvement in from three to seven movements. Those respondents who are involved in multiple movements may be more likely to be synergists who see the connections among different movements and who are more likely to play an active role in facilitating collective action within the larger “movement of movements.”

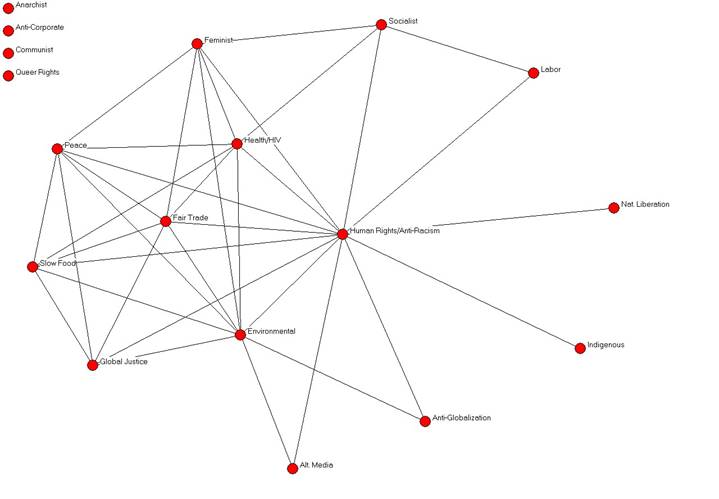

Figure 2: The network of movement linkages at the 2007 WSF in Nairobi

Comparison of the WSF05 and WSF07 network figures shows that the basic multicentric structure of the movement of movements did not change. In both networks there is a set of hub movements that strongly integrate all the other movements. The same cut-off of one-half of a standard deviation above the mean number of connections is used in both Figure 1 and Figure 2 (and also in Figure 3 below), and the same movements are used (see explanation above on page 3). As was the case for the WSF05 network, the matrix of movement pairs for the WSF07 meeting has no zeros, meaning that all of the 18 movements have at least one participant in all of the other movements. Only one of the forty-three anarchists is also actively engaged in the slow food movement, the socialists and the feminists. But there are no zeros. This was also the case in the WSF05 matrix.

Three of the movements (anarchist, communist and queer rights) that were disconnected by the high bar of connectedness in the WSF05 matrix were also disconnected in WSF07, whereas National Liberation met the test in Nairobi, but not in Porto Alegre, and Anti-corporate failed the test in Nairobi but not in Porto Alegre.. One of the same movements appears near the center (Human Rights/Anti-racism), but some that were rather central in 2005 have moved out toward the edge in 2007 (Peace, Global Justice and Alternative Media). The Environmentalists are still toward the center, but not as central as they were in Porto Alegre. Health/HIV is much more central than it was in Brazil, probably reflecting both an increase in global concern and a much greater crisis in Africa. Regarding overall structural differences between the two matrices, the 2007 network is more centered around a single movement (Human Rights/Anti-racism), but there are also more direct connections among some of the movements out on the edge (e.g. feminists and socialists, socialists and labor, slow food and global justice.

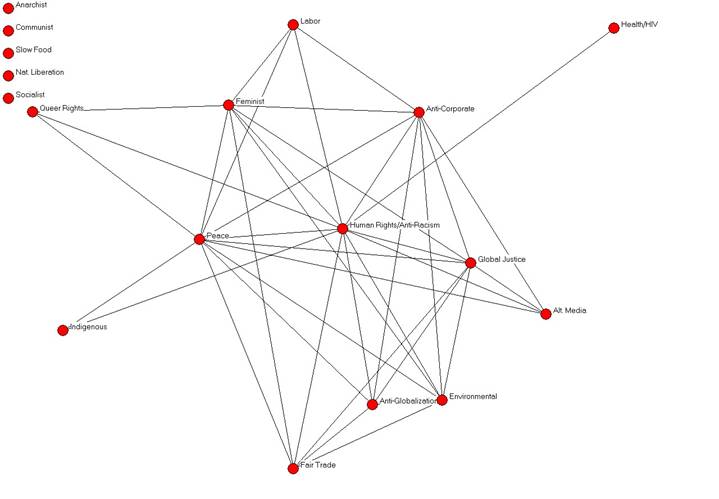

Figure 3: The network of movement linkages at the 2007 USSF in Atlanta

Figure 3 shows the network structure of movements obtain from responses by attendees at the United States Social Forum meeting that was held in Atlanta, Georgia in July of 2007. Once again the anarchists and communists do not make the one-half of a standard deviation above the mean number of connections cut-off, but now they are joined by national liberation, socialists and slow food. As with the earlier movement interconnection matrices, there are no empty cells. All the movements are interconnected by at least 2 common participants. Alternative media is rather better connected relative to its position in Nairobi, though not as central and connected as it was at Porto Alegre. The feminists appear rather more central than they were in either Porto Alegre or Nairobi. And Health/HIV is much farther out than it was in Nairobi and somewhat farther out than it was in Porto Alegre. Anti-corporate is closer to the center than it was in Porto Alegre and Nairobi. The USSF network is still multicentric and has the same hubs as in the Porto Alegre network, except that feminism has moved into the center. There are still no separate factions.

These same differences are revealed when we compare the multiplicative coreness scores of the movements across the meetings. Multiplicative coreness indicates the extent to which a node possesses a high density of connections with other nodes. Less coreness is characterized as possessing few interconnections. Nodes with high coreness are often capable of greater coordinated action and a greater mobilization of resources, while nodes with less coreness are not. Table 3 shows the coreness scores and the ranks of the movements.

|

|

2005 |

|

2007 |

|

USSF |

|

|

|

Coreness Rank |

Multiplicative Coreness Scores |

Coreness Rank |

Multiplicative Coreness Scores |

Coreness Rank |

Multiplicative Coreness Scores |

|

Human Rights/Anti-Racism |

1 |

0.441 |

1 |

0.491 |

1 |

0.476 |

|

Peace |

2 |

0.364 |

3 |

0.309 |

2 |

0.363 |

|

Environmental |

3 |

0.345 |

2 |

0.336 |

4 |

0.269 |

|

Alternative Media |

4 |

0.300 |

11 |

0.194 |

9 |

0.228 |

|

Global Justice |

5 |

0.272 |

5 |

0.272 |

5 |

0.267 |

|

Anti-Globalization |

6 |

0.251 |

9 |

0.198 |

6 |

0.252 |

|

Fair Trade |

7 |

0.232 |

6 |

0.269 |

8 |

0.231 |

|

Feminist |

8 |

0.202 |

7 |

0.249 |

3 |

0.290 |

|

Socialist |

9 |

0.190 |

10 |

0.197 |

15 |

0.119 |

|

Labor |

10 |

0.199 |

12 |

0.169 |

10 |

0.210 |

|

Anti-Corporate |

11 |

0.177 |

15 |

0.107 |

7 |

0.251 |

|

Indigenous |

12 |

0.174 |

13 |

0.159 |

12 |

0.163 |

|

Health/HIV |

13 |

0.162 |

4 |

0.293 |

14 |

0.139 |

|

Slow Food |

14 |

0.151 |

8 |

0.211 |

13 |

0.141 |

|

National Liberation |

15 |

0.132 |

14 |

0.120 |

17 |

0.070 |

|

Queer Rights |

16 |

0.120 |

16 |

0.093 |

11 |

0.202 |

|

Communist |

17 |

0.098 |

17 |

0.083 |

18 |

0.060 |

|

Anarchist |

18 |

0.070 |

18 |

0.027 |

16 |

0.093 |

Table 3: Multiplicative Coreness Scores and Ranks of Movements in the WSF05, WSF07 and USSF07 Networks

Both the scores and the ranks tell the story. Seven movements changed their ranks by more than four places: Alternative Media, Feminism, Health/HIV, Anti-Corporate, Socialist, Slow Food and Queer Rights (underlined in Table 3). The other 11 movements were rather stable in terms of their coreness scores and ranks.

It should also be noted that the total number of network connections at the USSF was approximately two times greater than at the WSF05 or the WSF07. The average number of interconnections among movements at both the WSF05 and the WSF06 was sixteen, while at the USSF07 the average number of connections was thirty-one. This is not mainly due to a larger number of respondents. There were 544 respondents in Porto Alegre, 431 in Nairobi and 555 in Atlanta. Rather the level of interconnectedness among movements, that is the number of links produced by people being actively involved in more than one movement, was simply greater at the USSF meeting in Atlanta. Table 2 above shows that a larger percentage of respondents indicated active involvement in a larger number of movements

While we are interested in detecting and explaining the changes that occurred in the networks, we are also interested in the amount of stability. The progressive wing of the global public sphere, what Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2006) has called the “global left,” is an assemblage in formation, but it also exhibits a degree of continuity over time and across space. Our earlier research on the WSF05 movement network examined this issue by comparing the web of social movements derived from the study of WSF05 attendees to a network structure produced by studying the number of joint mentions of movement titles on web pages on the Internet (Chase-Dunn et al 2007:11-13). Despite these very different approaches to studying movement interlinks, the results were remarkably consistent.

Another way to estimate the degree of stability across time and space is to use the QAP routine in UCINet to calculate the Pearson’s r correlation coefficients between the WSF05, WSF07 and USSF matrices of movement interlinks. Table 4 shows the results.

|

|

WSF05 |

WSF07 |

USSF07 |

|

WSF05 |

1 |

.80 |

.82 |

|

WSF07 |

|

1 |

.71 |

|

USSF07 |

|

|

1 |

Table 4: Pearson’s r correlation coefficients of movement interlinks

All three of the Pearson’s r correlation coefficients were statistically significant. These positive correlations indicate a good degree of stability, though the correlation between Nairobi and the USSF in Atlanta was somewhat smaller than the other two correlations.

Conclusions

Probably the biggest finding is that there is a fairly stable network structure of movements as indicated by the responses of attendees at Social Forum meetings in very different locations and even though the meetings had rather different kinds of support from governments and political organizations. As mentioned above, a rather similar structure is found when we examine the contents of web pages. This means that there is indeed a global movement of movements and that it is a multicentric network without separate factions and integrated by a set of more central movements that link the rest. The key role played by the human rights movement in the Social Forum process is important, even though many activists resent the use of the human rights discourse by the powers that be to justify the existing structures of global governance. Those who want to democratize global governance should confront this issue head on by sharply distinguishing genuine concern for individual and group civil rights as well as issues of economic human rights and economic democracy, from the use of human rights discourse to justify neoliberal policies.

But we also found interesting differences between the network structures at the three meetings studied. Human rights/anti-racism was more central at the Nairobi meeting than it was at the other two meetings. As can be seen from Figure 3 above, human rights/antiracism is the only link between many traditional leftist movements, such as socialism, labor, and national liberation ( and also indigenism) and more middle-of-the-road or more functionally specific, and newer, social movements, whereas in both Porto Alegre and Atlanta the older left and labor movements had direct links with the newer or more specifically functional social movements. We have noted above that the Kenyan government was not very sympathetic with the radical political goals of the World Social Forum. It should also be mentioned that Nairobi is a major hub for Northern NGOs operating in Africa. These factors may account for the greater centrality of human rights/anti-racism at the WSF07. The alternative media group was also quite a bit less well linked to other movements at the WSF07 in Nairobi than in the other two meeting locations. We suspect that this may have to do with the greater connections that alternative media activists, who are mainly from Europe and the U.S., have with Latin America than with Africa.

So geography and the nature of local political support have important effects, and we think these are the main explanations for the differences we find in the WSF05, WSF07 and USSF networks of movements. We do not see any strong temporal trends in the development of the movement network. Indeed the WSF05 and USSF07 networks are more strongly correlated with one another than either is with the WSF07 that occurred between them in time (see Table 4 above). This complex entity is a robust multicentric network that has the possibility of engaging in global collective action.

References

Amin, Samir 1997 Capitalism in an Age of Globalization. London: Zed Books.

__________ 2006. “Towards the fifth international?” Pp. 121-144 in Katarina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Democratic Politics Globally. Network Institute for Global Democratization (NIGD Working Paper 1/2006), Tampere, Finland.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K. Hopkins, and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic Movements. London: Verso.

Borgatti, S. P. and Everett, M. G. and Freeman, L. C. 2002 UCINET 6 For Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis http://www.analytictech.com/

Boswell, Terry and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2000. The Spiral of Capitalism and Socialism: Toward Global Democracy. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner.

Byrd, Scott C. 2005. “The Porto Alegre Consensus: Theorizing the Forum Movement.” Globalizations. 2(1): 151-163.

Carroll, William K. and R.S. Ratner 1996 “Master framing and cross-movement networking in contemporary social movements” Sociological Quarterly 37,4: 601-625. Carroll, William K. 2006a “Hegemony and counter-hegemony in a global field of action” Presented at a joint RC02-RC07 session on alternative visions of world society, World Congress of Sociology, Durban, South Africa, July 28. ______________ 2006b “Hegemony, counter-hegemony, anti-hegemony” Keynote address to the annual meeting of the Society for Socialist Studies, York University, Toronto, June. Forthcoming in Socialist Studies, Fall, 2006. Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Christine Petit, Richard Niemeyer, Robert A. Hanneman and Ellen Reese 2007 “The contours of solidarity and division among global movements” International Journal of Peace Studies 12,2: 1-15 (Autumn/Winter)della Porta, Donatella. 2005a. “Multiple Belongings, Tolerant Identities, and the Construction of ‘Another Politics’: Between the European Social Forum and the Local Social Fora,” Pp. 175-202 in Transnational Protest and Global Activism, edited by Donatella della Porta and Sidney Tarrow. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Fisher, William F. and Thomas Ponniah (eds.). 2003. Another World is Possible: Popular Alternatives to Globalization at the World Social Forum. London: Zed Books.

Hanneman, Robert and Mark Riddle 2005. Introduction to Social Network Methods. Riverside, CA: http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/

IBASE (Brazilian Institute of Social and Economic Analyses) 2005. An X-Ray of Participation in the 2005 Forum: Elements for a Debate Rio de Janeiro: IBASE http://www.ibase.org.br/userimages/relatorio_fsm2005_INGLES2.pdf

Krinsky, John and Ellen Reese. 2006. “Forging and Sustaining Labor-Community Coalitions: The Workfare Justice Movement in Three Cities.” Sociological Forum 21(4): 623-658.

Obach, Brian K. 2004 Labor and the Environmental Movement: The Quest for Common Ground. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Petit, Christine. 2004. “Social Movement Networks in Internet Discourse” Presented at the annual meetings of the American Sociological Association, San Francisco. IROWS Working Paper #25.https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows25/irows25.htm

Reese, Ellen, Christine Petit, and David S. Meyer. 2008 “Sudden Mobilization: Movement Crossovers, Threats, and the Surprising Rise of the U.S. Anti-War Movement.” Social Movement Coalitions, edited by Nella Van Dyke and Holly McCammon

Reese, Ellen, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Kadambari Anantram, Gary Coyne, Matheu

Kaneshiro, Ashley N. Koda, Roy Kwon, and Preeta Saxena 2008

“Place and Base: the Public Sphere in the Social Forum Process” IROWS Working Paper # 45.

Reitan, Ruth 2007 Global Activism. London: Routledge.

Rose, Fred 2000 Coalitions Across the Class Divide: Lessons from the Labor, Peace, and Environmental Movements. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa 2006 The Rise of the Global Left. London: Zed Press.

Sen, Jai and Madhuresh Kumar with Patrick Bond and Peter Waterman 2007 A Political Programme for the World Social Forum?: Democracy, Substance and Debate in the Bamako Appeal and the Global Justice Movements. Indian Institute for Critical Action : Centre in Movement (CACIM), New Delhi, India & the University of KwaZulu-Natal Centre for Civil Society (CCS), Durban, South Africa. http://www.cacim.net/book/home.html

Schönleitner, Günter 2003 "World Social Forum: Making Another World Possible?" Pp. 127-149 in John Clark (ed.): Globalizing Civic Engagement: Civil Society and Transnational Action. London: Earthscan.

Smith, Jackie, Marina Karides, et al. 2007 The World Social Forum and the Challenges of Global Democracy. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Starr, Amory. 2000. Naming the Enemy: Anti-corporate Movements Confront Globalization. London: Zed Books.

Van Dyke, Nella 2003 “Crossing movement boundaries: Factors that facilitate coalition protest by American college students, 1930-1990.” Social Problems 50(2):226–50.

Watts, Duncan 2003. Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. New York: W.W. Norton.