Social movement

Networks

As Reflected in Web Publications

Christopher Chase-Dunn and James

Love

Department of Sociology and Institute for Research on World-Systems

(IROWS)

University of

California-Riverside,

Draft v. 4-2-09 6133 words

Abstract: This paper

uses the Internet to study the sizes of and the contours of relationships among

contemporary social movements. Trends in movement size are estimated and we use

published web pages that contain mentions of pairs of social movements to

examine the network of movements. These results are compared with other studies

that use survey research to study movement networks. We use both counts of

published web pages produced by Google searches and trends in the volume of

searches produced by Google Trends.

To

be presented at the annual meeting of

the Pacific Sociological Association, This is IROWS Working Paper #49 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows49/irows49.htm

Thanks to Christine Petit

and Richard Niemeyer for their help on this research.

This paper examines the organizational space of

contemporary social movements by counting Web sites that mention pairs of

movements by name. In this study we seek

to understand the structure of connections among progressive social movements

and how those connections may be evolving over time. For this purpose we

analyze results obtained from using the Google search engine to count the number

of web sites containing certain phrases and pairs of phrases.[1]

We examine the contours of the social movement connections found on web pages,

and how these have changed over time.

The tricky problem is that our findings probably reflect other things as

well as changes in the structure of the network of popular movements in the

global public sphere. Undoubtedly our choice of the English language and the

vagaries of Internet search engines may also be consequential for our findings.

We shall try to sort out these different elements affecting the structure of

movement connections based on Web publications.

There is a large scholarly literature on networks, coalitions

and alliances among social movements (e.g. Carroll and Ratner 1996; Krinsky and

Reese 2006; Obach 2004; Reese, Petit, and Meyer 2008; Rose 2000; Van Dyke

2003). Our study is theoretically motivated by this literature as well as by

world-systems analyses of world revolutions (Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein

1989; Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000) and Antonio Gramsci’s analysis of

ideological hegemony, counter-hegemonic movements and the formation of

historical blocks [see also Carroll and Ratner(1996) and Carroll (2006a,

2006b)].

The Internet is both a vast trove of information

and a global interaction network for producing new information about how people

think and their capabilities for transnational collective action. For those

social scientists who are interested in global phenomena this makes feasible

the extension of older research methods into new realms, and this extension is

fraught with issues that need to be resolved so that we can know how much to

trust the information generated by Internet research (e.g. see Bainbridge

2009). This paper will explore some of these issues.

We assume that the number of published sites on the Web

is to some extent a positive function of the number of people who support each

movement. This should be the case because popular support should provide more

resources and more activity, resulting in more publication. But there are

undoubtedly other factors besides popular support. Wealthy individuals or

political groups can pay for the production of Web publications. Official

government agencies and political campaigns can use the discourse of social

movements. Nevertheless we still think it is likely that the amount of

publication on the Web should be related to the size and strength of social

movements and we have used the Google search engine since 2004 to determine the

number of web pages on which certain phrases that indicate content relative to

each of seventeen social movements.

Social movement organizations may be integrated both

informally and formally. Informally,

they are connected by the voluntary choices of individual persons to be active

participants in multiple movements. Such

linkages enable learning and influence to pass among movement organizations,

even when there may be limited official interaction or leadership coordination. In the descriptive analyses below, we assess

the extent and pattern of informal linkage by ascertaining the links of

movements as indicated by Web publications.

At the formal level movement organizations may provide legitimacy and

support for one another, and they may collaborate in joint action. The extent of identification and formal

cooperation among movements both causes and reflects informal connections among

participants and the publication of web documents that combine movement

discourses.

The extent and pattern of linkages among the memberships

and among the organizational leaderships of social movement organizations are

highly consequential for the potential for collective action in local and

global political struggles. Some forms

of connection [e.g. “small world” networks, (Watts 2003)] allow the rapid spread

of information and influence; other forms of connection (e.g. division into

“factions” by region, culture, language or issue area) may inhibit

communication and make coordinated action more difficult. The ways in which

social movements are linked (or not linked) may facilitate or obstruct efforts

to organize cross-movement collective action. Network analyses can reveal

whether or not the structure of alliances contains separate subsets with only

weak ties, and the extent to which the network of movements is organized around

one or several central movement nodes that mediate ties among the other

movements.

Our Internet research on the structure of alliances among

social movements has been paralleled by a series of studies of transnational

social movements that have participated in the World Social Forum process

(Smith et al 2007; Chase-Dunn et al 2007). These studies obtained

survey responses from attendees at World Social Forum meetings in

The Relative

Sizes of Social Movements

Christine

Petit (2004) described her Google searchs performed on July 28, 2004 as

follows: “…I typed in the phrase ‘civil

rights movement’ and noted the number of websites containing that text.” The

parentheses return pages that have all the words together, whereas a search

without the parentheses would return all pages that contain the words even

though the are at separate places in the web document. She then did this for

each of the other sixteen movements listed in Table 1 below. And then she typed

in pairs of movements e.g. “civil rights movement” “anarchist movement”.

Table 1 shows the total number of hits for all the

movements and the percentages for each movement for 2004, 2006 and 2008. It

should be noted that the total number of hits increase from 2,055,310 in 2004

to 39,377,900 in July of 2006, and

then decreased to 12,556,340 in October of 2008. We suspect that the Google

search engine methodology became more selective between 2006 and 2008. It is

quite unlikely that the number of pages on the Internet decreased. But Table 1

shows that the relative percentages of many of the movements are quite stable

between 2006 and 2008, so we think it is likely that whatever difference in

search engine methodology that was implemented between 2006 and 2008 did not

much affect the relative distribution of movement presences on the Web, which

is the focus of our study.

|

Movement |

July 28, 2004 |

July 18, 2006 |

October 22, 2008 |

|

civil rights |

27.80% |

34.30% |

30.82% |

|

labor/labour |

19.50% |

15.80% |

14.38% |

|

peace/anti-war |

18.60% |

20.20% |

12.21% |

|

women's/feminist |

12.90% |

10.00% |

11.29% |

|

environmental |

7.10% |

7.20% |

7.10% |

|

socialist |

2.50% |

2.40% |

4.14% |

|

communist |

1.90% |

1.10% |

3.20% |

|

gay rights |

1.80% |

4.60% |

1.82% |

|

human rights |

1.80% |

0.90% |

7.67% |

|

anarchist |

1.20% |

1.00% |

1.36% |

|

anti-globalization |

1.50% |

0.70% |

0.83% |

|

national liberation/ sovereignty |

1.10% |

0.20% |

2.92% |

|

fair trade/trade justice |

0.70% |

0.40% |

0.46% |

|

global justice |

0.60% |

0.30% |

0.35% |

|

slow food |

0.50% |

0.50% |

1.11% |

|

indigenous |

0.40% |

0.30% |

0.33% |

|

anti-corporate |

0.10% |

0.00% |

0.02% |

|

Total % |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

Total Number of Hits |

2,055,310 |

39,377,900 |

12,556,340 |

Table 1: Movement sizes as indicated by relative numbers of Web pages

These movement categories were originally designed

by Christine Petit for her 2004 study, and in order to be able to study changes

over time we have held to her original categories. Civil rights in the

The big five movements in Table 1 are civil rights,

labor, peace, feminism and environmentalism. Below these, the movements are

much smaller. In the Appendix we have a table that shows movement sizes based

on our studies of attendees at the World Social Forum in

We have already mentioned changes in the total number of

hits between 2004 and 2008 and the up-down trend of the civil rights movement.

Seven of the seventeen movements are quite stable over time in terms of

relative percentages: feminism, environmentalism, anarchism, fair trade, global

justice, and the indigenous movement. Peace and gay rights demonstrated an

up-and-down pattern across the three time points, as did civil rights. Labor

went down, as did anti-globalization, fair trade, global justice and

anti-corporate. Socialism and communism went up in the last period, as did

human rights and slow food.

Can we simply equate the relative sizes as an indicator

of movement strength, and can we interpret increases and decreases as changes

in the popularity and power of movements? It is well-known that Internet usage

and the publication of Web materials has been increasing geometrically since

the mid-1990s, and that both usage and publication have been diffusing across

the globe (Zook 2005). The growth and the trajectory of diffusion probably

affect the distribution of movement hits differently. Some movements were early

adopters and some have come later to Web publication. Thus trends should

reflect the diffusion process as well as changes in movement strength. Late

adopters should increase their percentages of Web publications over the time

period studied and early adopters should go down in terms of the relative

percentages of web pages.

But seven of the movements did not much change their

relative scores, and three others went up and then down. Labor,

anti-globalization, fair trade, global justice and anti-corporate went down.

Were these early adopters or did they actually decrease in movement strength

relative to other movements? Socialism, communism, human rights and slow food

went up in the last period. Were these late adopters or did they increase in

relative movement strength?

The geographical pattern of diffusion may also have

affected the Web activity of movements. As mentioned above, the civil rights

movement has been connected with the campaign for racial equality in the

Movement Topic

Size as Reflected By Web Search Activity

We have also used Google Trends, a tool for estimating

the number of searches performed by the Google Search Engine, and comparing

these over time to look for trends. We used this tool to examine the size

relationship among movement topics for the largest movements in our study

above. The number of searches is a different kind of indicator from the number

of web pages published. It shows how much interest the public has in topics and

how this has changed over time. Google Trends uses weekly data on searches

since January of 2004.

When we submit whole phrases such as “anarchist movement”

in Google Trends the program states

that: "Your terms - "anarchist movement" - do not have

enough search volume to show graphs." Only “civil rights movement” has

enough search volume to return a graph. This shows that searches for civil

rights movement varied over time and that the relative volume of searches

tended to decline over the period from 2004 to 2009 (See Figure 1).

Google Trends scaling

According to Google, data

are standardized based on the average search traffic of the term you

enter. Rather than producing raw search

results for the term, Google averages the weekly search counts during the

selected period and denotes this average as a 1. For example, if we searched “civil rights”

from 2004 to 2009 the graph would produce a baseline average for all searches

requested during the given period, represented as 1. However, if we observed that in early 2005,

the graph spiked to 3.5, this would inform us that searches during early 2005

were 3.5 times greater than the average searches attempted from 2004-2009. Google calls this relative scaling. When

multiple search targets are included in the same graph the user is allowed to

specify which of the items will be used to scale the rest of the items. We

chose to standardize the search counts on the “civil rights” movement topic. The

Google methodology does not make it clear how searches are compared across

different languages.

Figure 1: Relative volume of searches for "civil rights movement", 2004-2009[2]

For our study of the

relative size of movements we want to compare search volumes for the different

movements. We were not able to do this for the whole phrases containing the

word “movement,” but we were able to do it for main topics of the five largest

movements listed in Table 1 above based the sizes of published web material.

That is, we submitted the topics “civil rights,” “labor,” “peace,” “feminism,”

and “environmentalism” to Google Trends to examine how the search volumes for

these movement terms compare with one another. This worked in Google Trends and

produced the results shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Relative volume of searches for movement topics, 2004-2009

Figure 2 uses the civil

rights as unity (1) to scale the relative volumes of the five movement topics.

Civil rights is the blue line with diamonds and produces a trend similar to the

one shown in Figure 1 except that now we can see the relative sizes of the

search volumes for the other movement topics.

Whereas the study of numbers of web pages for social

movements discussed in Table 1 reveals that the civil rights movement is

considerably larger than the labor movement based on the number of web pages

published, when we examine the volume of searches we find that the topic of

“labor” is far larger than is the topic of “civil rights” based on comparing

the number of web searches by individuals using the Google search engine. So in

relative size terms numbers of web publications and the volume of searches are

somewhat different animals. The question for this paper is what do these

indicators have to do with the relatives sizes of social movements in terms of

numbers of adherents and other resources?

We surmise that the web page counts are better indicators of relative

movement size than are the search volumes. A large number of web searches that

contain a particular movement topic may only mean that something has happened

that has piqued the public’s interest in that topic. It is more akin to popularity than movement

size. Of course popularity can be a resource. But it may also be a liability.

It all depends on the meaning context. Searches for labor or civil rights may

be launched by both proponents and opponents of the the associated movements.

Nevertheless it is interesting to compare the

search volumes displayed in Figure 2. By far the highest are “labor,” which is

cyclical with annual high peaks in August or September, and annual low points

in December or January. The “peace” topic is similar in volume to labor, but

without the annual spiky peaks and low points. Civil rights is much lower in

volume, but is still higher than feminism, which is itself higher than

environmentalism. It is probably unfair

to use the topic of “environmentalism” to assess the amount of public interest

in environmental issues. When we

substitute “global warming” for “environmentalism” in Figure 3 we see that

global warming starts off at about the same level as civil rights, but then in

late 2006 it shows a large wave of search volume and stays fairly high until

2008. In 2009 the wave has fallen off somewhat, but it is still twice as high

as civil rights.

Figure 3: Movement topic search volumes with global warming, 2004-2009Figure 3: Movement topic search volumes with global warming, 2004-2009

We also use evidence from the Internet to study the interconnections among different social movements.

Network Structure of Social Movements in Internet Pages

We compare the overlapping of movements by counting web pages that mention the

names of movement pairs, e.g. environmental movement/labor movement at three

time points: 2004, 2006 and 2008. The counts of overlaps need to be

dichotomized for the purposes of network analysis using UCINet and we tried to

do this in a way that would make our results comparable with the study of

movement networks based on survey results. But the distributions of raw counts

were severely skewed (e.g. see Table 2 shows the raw counts for 2008), thus

raising the average of the counts far above the median of counts. To make the

distribution more normally distributed we performed a logarhythmic

transformation (log to the base ten) on the raw counts. We dichotomized the

logged overlap counts using the same cutting point used in the network analysis

reported above: ½ standard deviation above the mean to produce a network matrix

of zeros and ones. Table 3 shows the dichotomized scores for 2008.

|

Movement |

total |

civil |

labor |

anti-war |

women's |

enviro. |

socialist |

commun. |

gay |

human |

anti-glob |

anarchist |

national |

global |

slow food |

indigen. |

fair |

trade just. |

sovereign |

anti-corp |

|

civil rights |

4,190,000 |

|

111,000 |

37,100 |

53,500 |

37,200 |

8,200 |

5,790 |

21,900 |

13,300 |

2,820 |

1,930 |

1,290 |

1,940 |

474 |

686 |

279 |

76 |

719 |

133 |

|

labor |

1,150,000 |

111,000 |

|

13,400 |

18,800 |

20,700 |

89,300 |

38,800 |

2,620 |

7,120 |

3,170 |

6,270 |

2,470 |

1,890 |

184 |

800 |

576 |

63 |

214 |

211 |

|

anti-war |

655,000 |

37,100 |

13,400 |

|

6,590 |

7,100 |

8,610 |

3,850 |

3,690 |

2,690 |

4,340 |

2,260 |

1,680 |

3,580 |

98 |

349 |

408 |

63 |

222 |

157 |

|

women's |

787,000 |

53,500 |

18,800 |

6,590 |

|

11,400 |

4,240 |

4,840 |

5,980 |

13,800 |

1,250 |

1,030 |

777 |

685 |

145 |

559 |

150 |

22 |

123 |

53 |

|

environmental |

861,000 |

37,200 |

20,700 |

7,100 |

11,400 |

|

2,330 |

1,660 |

1,920 |

15,300 |

3,750 |

1,160 |

208 |

1,170 |

851 |

679 |

645 |

70 |

280 |

229 |

|

socialist |

533,000 |

8,200 |

89,300 |

8,610 |

4,240 |

2,330 |

|

12,500 |

2,040 |

1,140 |

2,240 |

5,990 |

1,620 |

530 |

2,530 |

324 |

30 |

991 |

856 |

46 |

|

communist |

408,000 |

5,790 |

38,800 |

3,850 |

4,840 |

1,660 |

12,500 |

|

433 |

527 |

861 |

2,410 |

6,230 |

315 |

86 |

233 |

15 |

7 |

83 |

27 |

|

gay rights |

228,000 |

21,900 |

2,620 |

3,690 |

5,980 |

1,920 |

2,040 |

433 |

|

3,260 |

272 |

149 |

30 |

67 |

22 |

19 |

18 |

5 |

50 |

7 |

|

human rights |

943,000 |

13,300 |

7,120 |

2,690 |

13,800 |

15,300 |

1,140 |

527 |

3,260 |

|

790 |

90 |

754 |

596 |

60 |

425 |

99 |

10 |

2,350 |

6 |

|

anti-globalization |

106,000 |

2,820 |

3,170 |

4,340 |

1,250 |

3,750 |

2,240 |

861 |

272 |

790 |

|

2,000 |

1,210 |

3,190 |

401 |

240 |

719 |

150 |

140 |

627 |

|

anarchist |

167,000 |

1,930 |

6,270 |

2,260 |

1,030 |

1,160 |

5,990 |

2,410 |

149 |

90 |

2,000 |

|

525 |

471 |

8 |

73 |

17 |

7 |

88 |

28 |

|

national liberation |

314,000 |

1,290 |

2,470 |

1,680 |

777 |

208 |

1,620 |

6,230 |

30 |

754 |

1,210 |

525 |

|

95 |

6 |

111 |

9 |

5 |

68 |

6 |

|

global justice |

45,400 |

1,940 |

1,890 |

3,580 |

685 |

1,170 |

530 |

315 |

67 |

596 |

3,190 |

471 |

95 |

|

28 |

168 |

288 |

85 |

71 |

96 |

|

slow food |

138,000 |

474 |

184 |

98 |

145 |

851 |

2,530 |

86 |

22 |

60 |

401 |

8 |

6 |

28 |

|

7 |

212 |

13 |

124 |

5 |

|

indigenous |

42,100 |

686 |

800 |

349 |

559 |

679 |

324 |

233 |

19 |

425 |

240 |

73 |

111 |

168 |

7 |

|

34 |

7 |

108 |

5 |

|

fair trade |

44,000 |

279 |

576 |

408 |

150 |

645 |

30 |

15 |

18 |

99 |

719 |

17 |

9 |

288 |

212 |

34 |

|

814 |

8 |

20 |

|

trade justice |

15,100 |

76 |

63 |

63 |

22 |

70 |

991 |

7 |

5 |

10 |

150 |

7 |

5 |

85 |

13 |

7 |

814 |

|

2 |

6 |

|

sovereignty |

52,100 |

719 |

214 |

222 |

123 |

280 |

856 |

83 |

50 |

2,350 |

140 |

88 |

68 |

71 |

124 |

108 |

8 |

2 |

|

1 |

|

anti-corporate |

5,570 |

133 |

211 |

157 |

53 |

229 |

46 |

27 |

7 |

6 |

627 |

28 |

6 |

96 |

5 |

5 |

20 |

6 |

1 |

|

Table 2: Raw number of paired hits for social movements in 2008

|

movement |

civil |

labor |

anti-war |

women's |

enviro. |

socialist |

commun. |

gay |

human |

anti-glob |

anarchist |

national |

global |

slow food |

indigen. |

fair |

trade just. |

sovereign |

anti-corp |

|

civil rights |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

labor |

1 |

|

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

anti-war |

1 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

women's |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

environmental |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

socialist |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

communist |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

gay rights |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

human rights |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

anti-globalization |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

anarchist |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

national liberation |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

global justice |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

slow food |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

indigenous |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

fair trade |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

trade justice |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

sovereignty |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

|

anti-corporate |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Table 3: Paired hits dichotomized at 1 standard deviation above the mean in 2008

The QAP routine in UCINet was

used to calculate the Pearson’s r correlation coefficients for the logged

network matrices scores in 2004, 2006 and 2008.

2004-2006 .91

2004-2008 .91

2006-2008 .88

Table 4: QAP Pearson's r correlations for logged pair scoresLogged Pearson’s r correlation coefficients

The three matrices of log scores are highly correlated with one another, indicating a rather high level of stability of the network of social movements.

2004 2006 2008

1

civil rights movement

.367 .336 .363

2 labor

movement/labour .367 .408 .393

3 peace/anti-war

movement .367 .479 .366

4 women's

movement/feminist .324 .297 .291

5

environmental movement

.274 .274 .308

6

socialist

movement .299 .310 .363

7

communist

movement .236 .206 .291

8

gay rights

movement .171 .146 .310

9 human

rights movement .199 .146 .155

10

anti-globalization movement .270 .224

.166

11

anarchist

movement .278 .224 .053

12 national

liberation movement .173 .116 .000

13

global justice movement .143

.178 .000

14

slow food

movement .028 .000 .022

15

anti-corporate movement .024

.000 .096

16

indigenous movement .000

.000 .000

17 fair trade/trade justice

movement .000 .000 .000

18

sovereignty

movement .000 .043 .155

Table 5: Multiplicative coreness scores from binary movement matrices, 2004, 2006 and 2008

Table 5 shows the coreness scores calculated from the dichotomized movement matrices for 20-04, 2006 and 2008. Coreness reflects the density of connections of each node. This table shows that most of the movements do not change their centrality or lack of it much over the four year time period. The gay rights movement gets more central between 2006 and 2008 and the anti-globalization movements declines since 2004. The anarchist movement become less central after 2006 as do the global justice and national liberation movements. The sovereignty movement gets more central.

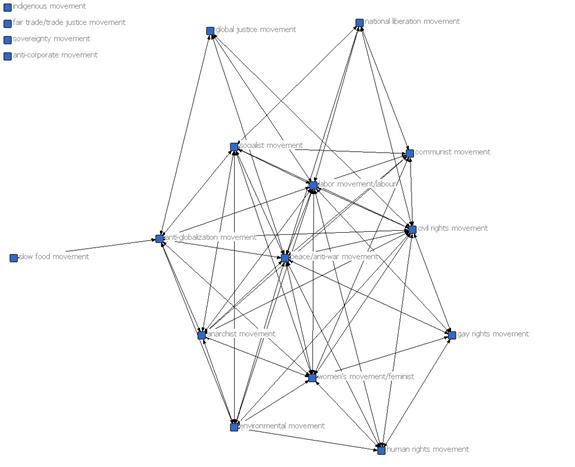

Figure 5 below depicts the network structure of movement links based on the Internet page counts for 2004. None of the movements were completely disconnected from the matrix by the dichotomization of the logged overlap scores. But the slow food movement has only one tie to the network through the anti-globalization movement. The civil rights movement is both the largest in terms of individual counts of web pages and in terms of overlaps with other movements as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Movement network structure in 2004 based on web hit pairs

Figure 4 includes both the civil rights movement and the human rights movement. It is often assumed that the human rights and civil rights movements are basically the same thing, but there are important differences between the two based on our web page study. The civil rights movement is far larger in terms of total web page publications than is the human rights movement. And with regard to position in the network of social movements, the civil rights movement is much more central. In retrospect it was probably a mistake to not to include civil rights in our list of studied movements at the World Social Forum. There we found that human rights/anti-racism was one of the largest movements and was the most central in the network of movements. We do not know how our study of movements using survey results at the WSF meetings might have been different if we had included civil rights.

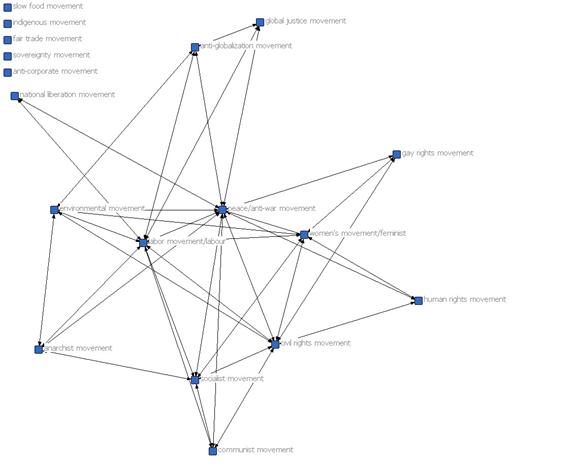

Figure 5: Movement network structure in 2006 based on Internet page pair mentions

The 2006 web page network results included a huge jump in the total of web pages with movement name pairs, which raised the mean number of overlaps. Despite that we logged the counts, the cutting point at ½ a standard deviation above the mean left five movements disconnected from the main network of movements: slow food, indigenous, fair trade/trade justice, and anti-corporate. The gay rights movement is less well-connected than it was in 2004.

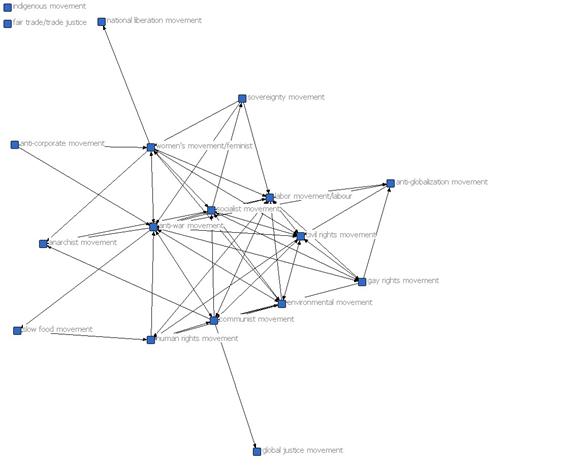

Figure 6: Movement network structure in 2008 based on Internet page pair mentions

By 2008 the slow food movement has become reconnected to the main network and the gay rights movement has again become as strongly connected with other movements as it was in 2004.

Conclusions

As

with our other studies of movement network structures based on survey research

responses, the networks show a rather consistent pattern of both movement size

distributions and the network of connections among movements. In all cases we have a single multicentric

web in which a few more centrally located movements connect most of the rest to

one another. This is a robust network structure that is unlikely to experience

major splits despite that often large contradictions among the goals pursued by

the individual movements. The web network results confirm our findings based on

individual commitments to movements in that there are at least some links among

most of the movements. This structure bodes well for the emergence of a new

global left that may be able to effectively contend in world politics.

Appendix: Comparing Web and Survey Results

Christine

Petit (2004) conducted a Google search engine project to study networks among

social movements as represented by texts available on the World Wide Web in

2004 and in 2006 she replicated her study in order to make it possible to

ascertain change over time and so that we can compare the results with our

survey evidence from the Porto Alegre World Social Forum of 2005.

|

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

|

|

July 04 Web hits |

% of total July04 |

%movement selections at WSF05 |

July06 web hits |

% of total July06 |

% 04-06 change in hits |

|

anarchist movement |

25,100 |

1.7% |

1.50% |

395,000 |

1.5% |

0% |

|

anti-corporate movement |

1,780 |

.1% |

3% |

15,100 |

.05% |

-.05% |

|

anti-globalization movement |

30,300 |

2% |

5% |

291,000 |

1% |

-1% |

|

global justice movement |

11,500 |

.8% |

6% |

112,000 |

.4% |

-.4% |

|

human rights movement |

36,500 |

2.5% |

12% |

362,000 |

1.4% |

-1.1% |

|

communist movement |

40,000 |

2.7% |

2% |

425,000 |

1.6% |

-1.1% |

|

environmental movement |

146,000 |

10% |

11% |

2,820,000 |

11% |

1% |

|

fair trade/trade justice movement |

14,830 |

1% |

5% |

159,200 |

.6% |

-.4% |

|

gay rights movement |

37,100 |

2.5% |

3% |

1,830,000 |

7% |

4.5% |

|

indigenous movement |

8,090 |

.5% |

4% |

120,000 |

.5% |

0% |

|

labor movement/labour |

400,000 |

27% |

6% |

6,220,000 |

24% |

-3% |

|

national liberation/sovereignty movement |

21,610 |

1.5% |

3% |

87,600 |

.3% |

-1.2% |

|

peace/anti-war movement |

382,000 |

26% |

9% |

7,950,000 |

31% |

5% |

|

slow food movement |

10,500 |

.7% |

3% |

199,000 |

.8% |

.1% |

|

socialist movement |

52,000 |

3.5% |

7% |

952,000 |

4% |

.5% |

|

women's movement/feminist |

266,000 |

18% |

5% |

3,940,000 |

15% |

-3% |

|

total |

1,483,310 |

|

|

25,877,900 |

|

|

Table 6: Internet hits in 2004 and 2006 compared with movement sizes obtained from survey questionnaires at the World Social Forum in 2005

For Table 6 we combined the fair trade movement and trade

justice movement web hits to make the Petit study comparable with the WSF

survey, and did the same with national liberation movement and the sovereignty

movement.

The comparison between web hits and movement choices at the WSF (Columns B,C

and E) show that the relative sizes are rather similar for ten of the sixteen

movements that are compared. This establishes a baseline of comparability

between these two very different sources of information about movement

linkages.

Six of the movements display what appear to be significant differences between

web texts and numbers of activists at the World Social Forum. Human rights,

global justice, indigenous and fair trade are better represented at the WSF

than on the web. Labor, peace and feminism are significantly less

represented at the WSF than on the web.

Looking at the change scores for the web hits in Column F, we see that the

biggest increases are in gay rights (4.5%) and the peace movement (5%). The women’s movement and the labor

movement have gone down by 3%, but the rest of the movements have stayed about

the same in percentage terms while the total numbers of hits increased

dramatically between 2004 and 2006. The general stability of the relative sizes

despite the rapid growth over the two year period and fairly good match with

the WSF survey data increases our confidence that we are measuring something

significant about the discursive space of transnational movements with the Internet

results.

References

Amin, Samir 1997 Capitalism

in an Age of Globalization.

__________

2006. “Towards the fifth international?” Pp. 121-144 in Katarina Sehm-Patomaki

and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Democratic Politics Globally. Network Institute

for Global Democratization (NIGD Working Paper 1/2006),

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K.

Hopkins, and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic Movements.

Bainbridge,

William S. 2009 “Expanding the use of the Internet in religious research” Review of Religious Research

Borgatti,

S. P. and Everett, M. G. and Freeman, L. C. 2002 UCINET 6 For Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis http://www.analytictech.com/

Boswell, Terry and Christopher

Chase-Dunn. 2000. The Spiral of Capitalism and Socialism: Toward Global

Democracy.

Byrd, Scott C. 2005. “The

della Porta, Donatella. 2005a. “Multiple Belongings, Tolerant

Identities, and the Construction of ‘Another Politics’: Between the European

Social Forum and the Local Social Fora,” Pp. 175-202 in Transnational Protest and Global Activism, edited by Donatella

della Porta and Sidney Tarrow. Lanham:

Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Fisher, William F. and Thomas

Ponniah (eds.). 2003. Another World is Possible: Popular

Alternatives to Globalization at the World Social Forum.

Hanneman,

Robert and Mark Riddle 2005.

Introduction to Social Network Methods.

IBASE

(Brazilian Institute of Social and Economic Analyses) 2005. An X-Ray of Participation in the 2005 Forum:

Elements for a Debate

Krinsky, John and Ellen Reese. 2006. “Forging and

Sustaining Labor-Community Coalitions: The Workfare Justice Movement in Three

Cities.” Sociological Forum 21(4): 623-658.

Obach, Brian

K. 2004 Labor and the

Environmental Movement: The Quest for Common Ground.

Petit, Christine. 2004.

“Social Movement Networks in Internet Discourse” Presented at the annual meetings of the American

Sociological Association, San Francisco. IROWS Working

Paper #25.https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows25/irows25.htm

Reese, Ellen, Christine Petit,

and David S. Meyer. 2008 “Sudden

Mobilization: Movement Crossovers, Threats, and the Surprising Rise of the

Reese, Ellen, Christopher

Chase-Dunn, Kadambari Anantram, Gary Coyne, Matheu

Kaneshiro, Ashley N. Koda, Roy Kwon, and Preeta Saxena

2008

“Place and Base: the

Public Sphere in the Social Forum Process” IROWS Working Paper # 45.

Reitan, Ruth 2007 Global

Activism.

Rose, Fred 2000 Coalitions

Across the Class Divide: Lessons from the Labor, Peace, and Environmental

Movements.

Sen, Jai and Madhuresh Kumar with Patrick Bond and Peter Waterman 2007 A Political Programme for the World Social Forum?: Democracy, Substance and Debate in the Bamako New Delhi , India & the University of KwaZulu-Natal Centre for Civil Society (CCS), Durban , South Africa

Schönleitner, Günter 2003 "World Social

Forum: Making Another World Possible?" Pp. 127-149 in John Clark (ed.): Globalizing

Civic Engagement: Civil Society and Transnational Action.

Smith, Jackie, Marina Karides, et al. 2007 The

World Social Forum and the Challenges of Global Democracy.

Starr, Amory. 2000. Naming

the Enemy: Anti-corporate Movements Confront Globalization.

Van Dyke,

Nella 2003 “Crossing movement boundaries: Factors that

facilitate coalition protest by American college students, 1930-1990.” Social Problems 50(2):226–50.

Zook, Matthew A. 2005 The Geography of the Internet Industry.