Last of the hegemons:

Chris Chase-Dunn, Roy Kwon,

Kirk Lawrence and Hiroko Inoue

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

![]()

v.11/15/2010 9828 words

Abstract: This paper

reexamines quantitative indicators of national economic and military power

since 1820 and discusses their meanings for the trajectory of power

concentration in the contemporary world-system. We discuss the causes of

For presentation at the session at the

Social Science History Association meeting on “The United States in Decline:

Why It Is Happening and What It Means” November 18, 12

IROWS Working Paper # 65 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows65/irows65.htm

*Thanks to William R. Thompson for seapower estimates from 1945 to 2007) and to Peter J. Taylor for “last of the hegemons.”

All

hierarchical human systems exhibit a sequence of concentration and

deconcentration of power, but the nature of power and the causes of rise and

fall evolve as world-systems get larger and more complex. The modern

world-system has experienced a series of episodes of global governance

organized around the predominance of a hegemonic national state that has

enjoyed a temporary superiority in economic centrality and political/military

power and influence: the United Provinces of the Netherlands in the 17th

century, the United Kingdom of Great Britain in the 19th century and

the United States of America in the 20th century. All three were

former semiperipheral polities that rose to core status and then took up the

role of political and economic hegemony.

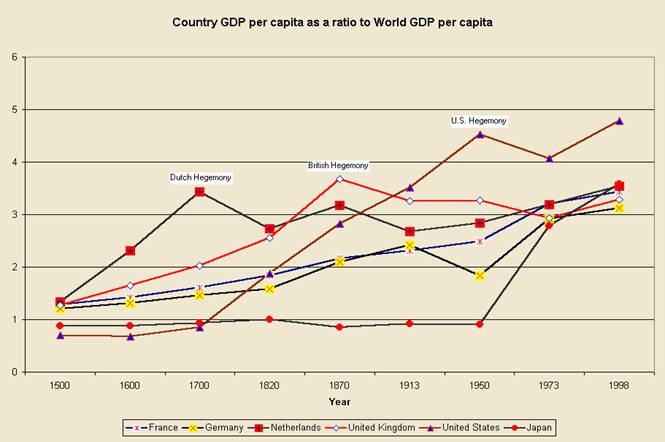

This

sequence, along with the institutionalization and spread of the international

system of sovereign states and the rise of supranational political institutions

since the Napoleonic Wars, constitutes the evolution of global governance as it

has occurred in the modern system. Figure 1 uses ratios of national Gross

Domestic Product(GDP) per capita to the average world GDP per capita to

illustrate the three hegemonies and to show the relative trajectories of

Figure 1: Three Hegemonies: GDP per capita as a ratio

to world GDP per capita 1500CE- 1998CE, Source: Maddison (2001)

We

are now once again in a period of deconcentration, an inter-regnum in which a

hegemon is declining. Hegemons perform functions of global governance,

especially by maintaining a level of stability within which the global economy

can operate relatively smoothly. Periods in which there is no hegemon tend to

be more contentious and violent, as contenders for global leadership struggle

with one another over who will be the next hegemon. We contend that the period

in which we are now heading is unlikely to eventuate in the rise of another

hegemon that could replace the

We

will rely primarily on Giovanni Arrighi’s (1994, 2006) careful comparison of

the similarities and differences between the current situation and the systemic

conditions that existed during the decline of British hegemony in the last

decades of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th

century. The similarities

include:

·

the hegemonies occurred in the context of great waves of economic

globalization (Chase-

Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000)

·

the hegemon’s loss of comparative advantage in the manufacturing of

consumer goods and then

capital

goods,

·

the emergence of a period of financialization in which the hegemon’s

centrality in the global

economy

appears to recover, albeit temporarily. The elements of this include:

o the hegemon’s

continuing centrality in global circuits of capital,

o financial advantages

due to control of “world money” (the pound sterling and the U.S. dollar)

o specialization in

financial services, and

o innovation in the

production of new financial securities and forms of investment

These

developments allow the hegemon to experience a late “belle époque” or an

“Indian summer” during which its decline in economic hegemony stabilizes. There

may also be some new technological innovations in this period,[1]

but the main tool for making profits shifts toward the expansion of credit and

financial services.

Another

similarity between the two periods of hegemonic decline is what has been termed

“imperial overreach.” Some of the leaders of the declining hegemon come to fear

that financialization is a bubble that cannot continue to expand, and so they

choose to play the other card in the hegemon’s hand --preponderant military

superiority (Kennedy 1980; Modelski 2005).

The story of the neoconservative plan to restore global order by using

Another

similarity: the language of the declining hegemon is English. This has had a

huge consequence for global linguistic standardization. Great efforts to

promote a synthetic global language, Esperanto, in order to facilitate global

communication and cooperation, failed. But English has become the de facto

language of global business despite that it is resisted and resented by many

national cultures and that cosmopolitans and multiculturalists try to support

multilingual interaction and communication. This has largely been the product

of two centuries of hegemony by English-speaking powers and successive waves of

global economic integration.

But

there are also important differences between the two periods of

hegemonic decline. The British went into

decline during a period in which the world-system was still greatly structured

by colonial empires, including the huge

While

the U.S. internal regime is somewhat similar to that of Great Britain, it is

also different. The biggest differences have to do with size and access to internal

resources. Whereas the British Isles are small, the United States came to be a

continental-sized power with substantial internal natural resources. Britain

became the workshop of a world in which it needed to import a lot of raw

materials, whereas the U.S. has internal raw materials that compete with the

products of other lands (Bonini 2009).

Having

been formed as a republic, and having largely obliterated the Southern landed

aristocracy, the U.S. is a purer form of capitalist democracy than Britain was

or is:

·

No House of Lords;

·

No constitutional monarchy;

·

A more complicated and purely ideological version of citizenship that

was needed to incorporate immigrants from quite different cultural backgrounds;

·

A partially-formed welfare state constituted more around the status

of soldier than the status of citizen (Skocpol 1992);

·

A labor movement that has been militant at times, but in which the

radical elements were more thoroughly defeated and politically marginalized.

The U.S. a purer form of the liberal capitalist

democracy than its mother country was or is.

There are also both

important similarities and important differences between the 19th and

20th century waves of globalization that need to be taken into

account in order to understand the contemporary world historical

situation. Both were periods of

increasing integration based on long-distance trade, increasing foreign

investment and the expansion and cheapening of global transportation and

communications. In both periods markets were deregulated and disembedded from

political and socio-cultural controls (Polanyi 1944). In both waves of

globalization a hegemonic core power rose to centrality in the global political

economy and then declined, losing first its comparative advantages in the production

of consumer goods and then capital goods. Both declining hegemons then used their

centrality in global networks to make money on financial services. Indeed, much

of the whole world economy became financially organized around the hegemon,

whose currency served as world money. The size of the symbolic economy of

“securities” – financial instruments representing ostensible future income

streams—grew far larger than the economy that was based on transactions of

material goods and services. In both waves of globalization capitalist

industrialization spread to new areas and came to involve a far larger number

of the world’s people in global networks of production and exchange.

There

were also important structural differences between the two waves of globalization.

Again, formal colonialism was abolished from the global polity during the most

recent great wave of globalization. The interstate system of legally sovereign

states was extended to the non-core, and so core states could no longer extract

tax revenues from their colonial empires. In the late 19th century

and early 20th century the British were able to use their empire,

especially its direct control over India, to finance the operations of the

British state. And Britain also was able to mobilize large numbers of soldiers

from its colonies to fight in the Boer Wars and in World War I. Both colonial

revenue and cannon fodder were available to the hegemon as well as to some of the

other contending core powers. That is a

source of support that no longer exists because of the evolution of global

governance. When the U.S., like Britain, began to use its centrality in global

military power to try to shore up its declining hegemony, it had to rely

primarily on U.S. citizens to perform soldierly duties. And it could not, as

did the British, directly tax a colonial empire to financially support its

adventures.

Of

course, there have been functional substitutes. The U.S. has tried to get its

allies to pay more of the costs of the Gulf Wars and the war in Afghanistan by

sending troops. Soldiers have been recruited disproportionately from

non-citizen immigrants within the United States by holding out the promise of

gaining formal citizenship. And the U.S. government has increasingly privatized

security by hiring companies of mercenaries to provide services in war zones.

There have been huge efforts to rely on “smart warfare technologies” as a

substitute for troops on the ground. None of these new factors have made the

U.S. foray into “imperial over-reach” any more successful than was the British

effort. The transition from hegemonic leadership to a policy that unilaterally employs

military supremacy in what appears to be a self-serving way generates too much

resistance from both the targets of coercion and from erstwhile allies. The

costs of empire were great in the 19th century, but they went up in

the 20th century because formal legal colonialism had been abolished.

Rather than using colonial subjects as cannon fodder the U.S. must use

immigrants seeking citizenship and highly paid private mercenaries. [2]

The United States: “Too Large To

Fail”

Probably the most

important structural difference between the 19th and 20th

century waves of globalization is the far greater relative size of the hegemon.

Figure 2 shows the proportions that the U.S. and British home markets

constituted in the total world Gross Domestic Product. At its peak in about

1900 Britain’s share was less than 10%. At its peak in 1945 the U.S. share was

35% and, though it has declined in a series of steps down since then, it was still

19% in 2007. This is nearly twice as large as the British economy was at its

peak. Thus the relative size of the hegemon in the larger world economy has

more than doubled. This simple fact has allowed the U.S. to play the

financialization card much more effectively than the British were able to do.

Figure 2 graphs the

shares of global GDP of selected countries: the United States, the United

Kingdom, China, India, Russia/USSR and the 12 European countries that were the

original members of the European Union (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland,

France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Sweden, UK, Portugal, Spain) added

together to show what has happened with the European Union’s trajectory in the

global economy. GDP is a measure of economic size that is strongly influenced

by territorial and population size as well as by level of economic development.

Figure 2 shows the U.S. trajectory that is the main focus of this paper. As

reported in Chase-Dunn, Reifer, Jorgenson and Lio (2005) the U.S. share of the

global economy peaked in 1945 when the rest of the developed world was in a

shambles as result of the destruction caused by World War II. Since then the U.S. share has declined, but

the downward slope has been interrupted by two periods in which the U.S. share

stabilized for a few years. These periods were from 1958 to 1968 and from 1985

to 1997. And there were brief reversals of the downtrend from 1947 to 1951 and

from 1997 to 1999. Since 2000 the U.S. share has steadily declined.

Figure

2: Country shares of world GDP,

1820-2006

Figure

3 is a similar graph that shows the same countries and time period as Figure 2

except that it displays the GDP per capita of each country as a ratio to the

world average GDP per capita. This is more purely a measure of relative

economic development rather than economic size.

Figure 3: GDP Per Capita as a ratio to World Average GDP

Per Capita

The GDP per capita ratios for the European

Union (EU) shown in Figure 3 were computed by summing the population of all EU

members and dividing the EU GDP by this summed total population to

get the average GDP per capita for all EU nations. Then we took this

average GDPPC and divided it by the average world GDP per capita to get the GDP

per capita ratios.

There are important differences between

Figures 2 and 3 as well as some similarities. The U.S. trajectory is similar in

the two graphs until about 1980. After that the relative level of economic

development shown in Figure 3 rose again during the neoliberal financialization

period from 1980 to 2000, whereas in purely size terms shown in Figure 2 the

U.S. trajectory was flat during this period. In both graphs the U.S. declined

sharply after 2000. The trajectory of the EU is also quite different in the two

graphs. In terms of economic size (Figure 2) the EU declined after 1970, while

in terms of relative level of development (Figure 3) the EU went up from 1950

to 1980 and then flattened out and then declined. Japan’s rise was much more

dramatic in terms of relative develop than it was in terms of size. And huge

differences are shown in the relationships that China and India display with

the other core powers. In terms of economic size (and using the PPP exchange

rates provided by Maddison) China seems to have converged with the U.S. by 2007

shown in Figure 2. But in Figure 3 (relative levels of development) China and

India were still far below the U.S and the other core powers.

The British were

capital investors in the rest of the world, and returning profits on foreign

investments were an important factor sustaining the “belle époque” of the

Edwardian era before World War I. The U.S. has obtained great returns on

investment abroad, but it has also been sustained by huge flows of investment

from abroad into the U.S. This is a big difference between British and U.S.

hegemonic decline. The British mainly exported capital and got returns from investments

abroad. The U.S. has done that too. The investments abroad of U.S.

multinational corporations grew rapidly in the decades after World War II. U.S.

companies established subsidiaries in many countries, branch offices and

manufacturing operations as well as resource-extracting firms (mines, logging

companies, fruit companies, etc). This is called “direct” investment because

the headquarters firm owns and controls the subsidiary. Other core countries and some non-core

countries also greatly expanded the operations of their own multinational

corporations. The core countries also expanded their purchases of bonds from

foreign national and local governments, and eventually core capital flowed in

to newly emerging stock markets in noncore countries. This is called

“portfolio” investment because the owner does not have control over the

day-to-day operations of the entities whose securities are purchased. All this

was similar to the export of capital by the British and other core countries in

the great wave of 19th century globalization.

But then something

different emerged -- huge inflows of foreign investment into the United States,

first from other core countries, especially Japan and Britain, but later from

non-core countries as well, especially China. It is these flows, which have

taken the form of buying bonds as well as investment in real estate and stocks,

which sustained the long U.S. expansion during the 1990s and the first years of

the 21st century. Michael Mann (2006) has called this “dollar

seignorage.” U.S. federal government

spending has been made possible without increasing taxes because governments

and investors abroad have been willing to buy U.S. government bonds. This

massive influx of money has also allowed the U.S. to sustain a huge trade deficit

in which imports of foreign goods and services have come to vastly exceed the

amount of U.S. goods that are exported, despite the outsourcing of jobs by U.S.

companies (see Figure 4). Because of its ability to sell bonds the U.S.

government was able to keep interest rates low and so developers built new

housing, and homeowners were able to sell their old houses and move into larger

houses because the prices of housing tended to go up. Residential mortgages

were also subsidized as they had been since the G.I Bill of Rights after World

War II, but the mortgage industry kept expanding credit and lowering the

requirements for obtaining a housing loan. Mortgages from the residential and

commercial real estate markets were also repackaged by Wall Street financial

entrepreneurs as global commodities and sold to institutional investors all

over the world. Thus did the wave of financialization during the U.S. hegemonic

decline take on new dimensions that differentiate it from what happened at the

end of the 19th century. The

U.S. government was also able to finance overseas wars in Afghanistan and Iraq

by selling bonds to foreign investors, including the Chinese, who came to have

such a stake in the U.S.-led financial bubble that they have become important

supporters rather than challengers.

Figure 4: U.S Trade Balance

(Exports/Imports), 1970-2006

The dollar sector of

the world economy is so large that there are no alternatives big enough to

replace it even when foreign investors have become disenchanted about the

prospects of future returns on their investments. The Euro would seem a

possibility, but the sheer size of the mountain of securities in

dollar-denominated investments makes the Euro sector look like a dwarf. The

difference in relative size between Britain in the 19th century and

the U.S. in the 20th century means that the rest of the world is

much more dependent on the economy of the hegemon now, and would-be competitors

have come to have a huge stake in the ability of the U.S. to buy their

products. As is sometimes said about gigantic corporations such as General

Motors, the U.S. economy is “too large to fail.”

The Global Policeman

The U.S. is also far

more supreme in military terms than Britain ever was. The United States

currently maintains 737 military bases abroad. By comparison, at the peak of

its global power in 1898 Britain had 36 bases (Johnson 2006: 138-39).

Figure 5: Seapower:

Warships as a Proportion of Total Warships

Modelski and

Thompson (1988; 1996) contend that global reach, as indicated by naval power,

is the best measure of concentration and deconcentration of power in the global

system. Their careful study of the evolution of warships has been used to

construct a measure of the rise and fall of global military power. Figure 5 shows

the relative seapower of Britain, the U.S., France, Russia and Germany since

1820. Modelski and Thompson (1988:11-13) estimate naval power by obtaining

information on the number of warships in the possession of each great power and

then dividing this figure by the total number of warships in the possession of

all world naval powers. This index for

each nation represents the national share of the world’s warships. Modelski and

Thompson (1988:44) only include “global powers” in their calculation of the seapower

index, which they define as nations that either (1) possess at least 10% of all

warships in the world or (2) account for at least 5% of total world naval

expenditures. Utilizing these criteria,

while multiple nation-states are considered global powers for years prior to

World War II, only the US and Russia qualify as world powers after World War II.

Figure 5 shows the

declining relative seapower of Great Britain, the amazingly low relative

seapower of Germany, the main challenger for hegemony in World Wars I and II,

and the relationship between the U.S. and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

The overwhelming superiority of the U.S. has gotten even greater since the fall

of the Soviet Union in 1989.

Another measure of

relative military power is that developed by the Correlates of War Project

(Singer 1987). The Correlates of War (COW) Project estimates the power of

nation-states by selecting key indicators that reflect the breadth and depth of

the resources a nation could utilize in militarized disputes. This is referred to as national material

capabilities (NMC). NMC is measured by utilizing national estimates of

demographic, industrial, and military capacity to create on overall measure of

NMC, these variables are: total population, urban population, primary energy

consumption, iron and steel production, military personnel and military

expenditures.

Figure 6 graphs the

COW NMC values for the U.S., Great Britain, the European Union, China and

India. There are some very big

differences from the seapower graph presented in Figure 5. The COW measure takes into account the size

of the military as indicated by the number of soldiers. The Chinese military is

very large because the Chinese population is very large. Demographic size has always been an important

component of war capability. The

Modelski and Thompson emphasis on seapower and global reach distinguishes

between regional power systems in which forces confront their adjacent

neighbors (usually with armed ground forces), and global power, in which the

ability to coordinate force on an intercontinental scale using naval power is

important (see also Rasler and Thompson 1984). They see an important

interaction between global and regional military geopolitics that can only be

observed and analyzed by distinguishing between naval global reach and regional

army power. The results shown in the Correlates of War NMC graph (Figure 6)

conflate the global reach (naval) and regional (army) power estimates. Figure 6 implies that China surpassed the

U.S. in terms of relative military capability in 1995. This only makes sense by

making the kind of global/regional distinction proposed by Modelski and

Thompson.

Figure 6: Correlates of War (COW) National Military Capability (NMC) as a Proportion of Total World Military Capability

We concur with

Modelski, Thompson and Rasler that there is an important distinction between

military global reach and the ability to exercise military power vis a vis

adjacent states. But for us this is conflated with the link between global

capitalism and global military power. The kind of global capitalism represented

by the U.S. and British hegemonies has been liberal and neoliberal capitalism

in which capitalist merchants, industrialists and financiers have unusually

predominant sway over the policies of their national states. But the U.S. is

also unusual in the extent to which it is both a continental-sized state with

important internal natural resources and a state that is under the control of

global capitalists. We also agree, at

least partially, with some of the theorists of a new stage of global capitalism

who are focusing attention on the notion of global class relations and the

emergence of a transnational state. The trajectory of the U.S discussed here is

part of the long process of the transnationalization of class relations and a

process of political globalization in which international political

organizations have become more and more important for global governance.

The strongest

economic challenges to U.S. hegemony in manufacturing during the decades after

World War II came from Germany and Japan, the countries that lost the war. During the long Cold War between the U.S. and

the Soviet Union, the other core countries were content to let the U.S. be the

superpower in military terms and so they did not develop their own military

capabilities to any significant extent. After World War II both Germany and

Japan renounced the use of military power, and kept only small capabilities,

relying on the U.S. for protection. The consequence, after the demise of the

Soviet Union, is that serious global military power is a near monopoly of the

hegemon. This is a very stable military structure compared with what existed in

the world-system before World War I. No single country, and not even a

coalition of countries, could militarily challenge the United States. But this

structure had been legitimized by the Cold War and by a relatively multilateral

approach to policy decisions employed by the United States in which major

decisions were taken in consultation with the other core powers.

The Democratic Peace and Future

Rivalry

International

relations theorists have argued that conflict within the core is quite unlikely

because all the major core powers have democratic regimes. The “democratic

peace” idea is that sharing a set of political values makes conflict less

likely, and that democratic regimes should be less likely than non-democratic

ones to initiate warfare. The relevance of this hypothesis for the future of

the probability of war among powerful states is based on the assumption that

the great powers remain democratic. This seems plausible enough if we could

assume stable economic development, well-legitimized institutions of global

governance and fair access to a growing supply of natural resources. Environmental

crises, population pressure, financial crises and hegemonic decline might well

provide challenges that the “democratic peace” factor is not strong enough to

mitigate (Chase-Dunn and Podobnik 1995).

A similar argument

applies in the case of those who contend that a global stage of capitalism has

emerged ,or is emerging, in which there is a single integrated transnational

capitalist class (Sklair 2001) and an emerging transnational state (Robinson

2004, 2008). Globalization has indeed increased the degree of global

coordination and integration, but will the institutions that have emerged be

strong enough to prevent the return of conflict among the great powers during a

new period of deglobalization, hegemonic decline, peak oil, resource wars and

strong challenges from social movements and counter-hegemonic regimes in the

non-core? That is the question.

The United States

has been in decline in terms of hegemony in economic production since at least

the 1970s and, as we have seen above, this has been similar in many respects to

the decline of British hegemony in the late 19th century. The great

post-World War II wave of globalization and financialization is faltering, and

some analysts predict another descent into deglobalization. The declining

economic and political hegemony of the U.S. poses huge challenges for global

governance. Newly emergent national economies such as India and China need to

be fitted in to the global structure of power. The unilateral use of military

force by the declining hegemon has further delegitimated the institutions of

global governance and has provoked resistance and challenges. A similar bout of

“imperial over-reach” in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries on the part of Britain led to a period of hegemonic rivalry and world

war. Such an outcome is less likely now, but not impossible.

After the attacks of

September 11, 2001 the United States adopted a more unilateral approach in

which actions were taken despite the opposition of some of its most powerful

allies. Germany and the U.N. Security Council did not support the invasion of

Iraq in 2003. This unilateral approach was reminiscent of Britain’s “imperial

over-reach” at the turn of the 20th century, but the context is importantly different.

In both cases uneven economic development has led to the emergence of new

challenges to the economic pre-eminence of the hegemon, but during the U.S.

hegemonic decline there are no serious military challengers among the

contending states. Armed resistance is mainly confined to those who employ

“weapons of the weak” (e.g. suicide bombers) and a few low-intensity guerrilla

forces in non-core countries. The U.S.

has been encouraging Germany and Japan to expand their military capabilities in

order to take up some of the expensive burden of policing the world. The U.S.

share of total global military power is so great that it is hard to imagine a

situation any time soon in which the structure of military power among core

states would become similar to the more even balance of miltary capabilities

that existed before World War I.

The U.S. would have

to greatly reduce its military capability, and potential challengers would have

to dramatically increase theirs. Since military capability is highly dependent

on economic wealth, the decline of U.S. economic hegemony could eventually have

such a result, a point that was made by Barack Obama during the presidential

campaign of 2008. But it takes time to build up military capability. This could happen quickly if an arms race

situation were to emerge such as the one that existed before World War I

between Germany and Britain. But in the current situation who would play the

role that Germany played before World War I -- an economic challenger that

morphs into a military challenger? No single country could do this because the

U.S. supremacy is so great. But a coalition of countries (Japan and China,

China and Russia, Germany and Russia, or the European Union) could conceivably

do it at some point in the future.

Another Round of U. S. Hegemony?

Modelski

and Thompson (1994) contended that there were two rounds of British hegemony;

one in the 18th century and another one in 19th century.

They contend that under some circumstances a hegemon can succeed itself. The

logic of sclerosis can be overcome if new internal interest groups who are

partisans of new industries can overcome the power of the vested interests of

the old industries. Normally this is not possible within the confines of a

single national polity and this explains why hegemony usually moves on. Indeed

uneven develop has been the main rule for centuries. If this were not so an

initial comparative advantage would last for millennia. Mesopotamia, the

original heartland of cities and states in the Bronze Age, would still be the

leading edge of human sociocultural evolution. Long term studies of the

largest of cities and empires show that hegemonic empires rarely succeed

themselves, although this has happened occasionally (Wilkinson 1991).

The most explicit argument for the likelihood of another round of U.S. hegemony was made by Joachim Rennstich (2001, 2004). Rennstich noted that the decline of earlier great powers had much to do with institutional rigidities. The British had a hard time moving from the family-centered firm to the corporate structure pioneered in the U.S. But the U.S. is a more flexible society with a history of political efforts to restrain monopolies. The rise of the NASDAQ stock exchange despite resistance from the New York Stock Exchange is an important example of U.S. institutional flexibility. Rennstich contended that the U.S. has developed a powerful capability by which newly rising industries could escape the clutches of old vested interests and flourish. He noted that high technology firms that felt that they were being sidelined at the New York Stock Exchange were able to form their own stock market, the NASDAQ. This was possible because the culture of the U.S. genuinely supports innovation and independence, and because an anti-monopoly tradition in the U.S. federal government occasionally gets trotted out by political entrepreneurs who go after firms that appear to be too greedy at the expense of the consuming public.

Rennstich also noted that U.S. culture is somewhat unusually open to social and

economic change relative to other national cultures. Europeans worry about

genetically modified foods (GMOs), whereas consumers in the U.S. do not seem to

mind that ‘frankenfoods” can be sold to them without labeling. Rennstich’s

point is that this is a very flexible culture that is open to change, and that

this characteristic is probably an advantage in future competition over new

lead industries (especially biotechnology). Of course there are other

interpretations of the GMO issue. Large corporations have great influence over

the activities of government regulators in the U.S. and spend large amounts of

money to influence public opinion. These

factors might work for or against a new round of hegemony based on

reindustrialization depending on the balance of forces within the U.S.

corporate elite. Arguably the powers

that be on Wall Street do not need another round of U.S. hegemony based on new

lead industries because they are making plenty of profits by investing outside

of the U.S.. This is similar to what happened with the expansion of foreign

investment by the British capitalist class.

It is well-known that the U.S. has had a comparative advantage in higher

education, especially in research universities that develop advances in both

pure and applied sciences. This advantage should lead to an advantage in the

commercialization of new technological advances and, in principal, could be the

basis of a restoration of U.S. economic hegemony that is profitable enough to

continue to support those aspects of hegemony that are less profitable.

Information technology has probably already run the course of the product cycle

from technological rents to competition over production costs.

There will undoubtedly be a few new gadgets and profitable Internet services that will redound to U.S. firms such as Apple and Google, but this is not likely to be the basis of a new growth industry in which returns are concentrated within the U.S. We have already mentioned that British hegemonic decline occurred despite that Britain continued to lead in some new high technologies such radio, radar and television. Britain also maintained its centrality in the global telegraph network during World War I, enabling it to read communications between the Germans and other countries that were intended to be secret (Hugill 1999). But a few cutting edge innovations are not enough for the restoration of economic hegemony.

Biotechnology and nanotechnology have greater possibilities. And green technology that allows more efficient use of natural resources is also a possibility. A restoration of U.S. economic hegemony could also provide the resources for a potential restoration of U.S. political hegemony. Of course the new regime would have to distance itself from the kind of unilateral adventurism displayed in the second Iraq war, and would have to respect the existing institutions of multilateral global governance that the U.S. championed after World War II. Greater concern about global equality and a genuine effort to understand peoples who are culturally different might go a long way toward undoing the damage done by the neoconservatives during the Bush administration from 2000 to 2008.

One advantage of such a development that might find support both at home and

abroad is that the current unipolar structure of the global military apparatus

could be maintained, thus reducing the probability that another round of

hegemonic rivalry might descend into world war, as it always has in the past.

Such a unipolar structure of military power could be made much more legitimate

by bringing it under the auspices of the United Nations or an expanded and

democratized North Atlantic Treaty Organization. If this were combined with

disarmament of national forces, the overall size and expense of the global

military apparatus could be reduced.

Rennstich made his

argument about the possibility of another round of U.S. hegemony ten years ago. The characteristics he pointed out may have

partly accounted for the recovery of the U.S. in the 1990s, though these

characteristics will probably not be strong enough to overcome the path

dependencies that stand in the way of a geneuine resportation of U.S. hegemony

based on comparative advantage in production.

The Obama campaign

in 2006 promised a new political regime with a strong industrial policy of

renewal that was willing to husband resources and invest in education and

product development, and that could overcome the internal resistance to new

taxes by mobilizing a popular constituency to support these developmental

projects. The election of Obama reminded world-systems evolutionists that world

history is open ended. The demise of these policy proposals also reminds us

that unexpected conjunctural events tend to get ironed out by the structural

forces of the longue duree.

The most recent

financial meltdown that began in 2006 is similar in many ways with earlier debt

cycles, but different in others (Chase-Dunn and Kwon 2010). Despite

greater reliance on less centrally-coordinated market-based approaches to debt

problems (Suter 2009), there has not been a total collapse of the global

financial system. The Wall Street bail-out allowed the stock markets to

recover. There appears to be a very slow recovery of investment but a

continuing high level of unemployment. This said, the global economy has not

really collapsed. There have been a few protectionist challenges to the

“free trade” regime, but trade globalization was still going up as recently as

2006. Investment globalization has become wobbly, but it has not yet

collapsed. The recent meltdown has not as yet led to something like the

Great Depression that began in 1929. Within the United States there has

not been a rebirth of strong anti-capitalist social movements. Rather the

populist right has made the most hay out of anti-Wall Street sentiment. A “New

Deal” situation has not emerged. Rather the right has gained support by

accusing the black President of being a socialist and a Muslim, while those on

the Left him as a Hoover rather than a Roosevelt. All this portends a

continuing slow decline of U.S. hegemony rather than any abrupt change or

another round of hegemony by the U.S. This is not surprising from the point of

view of recurrent cycles of hegemonic rise and fall.

Rivalry, Ecocatastrophe and

Deglobalization: The Perfect Storm

A more likely

scenario for the next several decades is continued U.S. hegemonic decline and

resultant economic and political/military restructuring of the world-system.

Here the scenario bears a strong likeness to what happened during the decline

of British hegemony at the end of the 19th century, but with a few

important differences. We have already seen some developments that are strongly

reminiscent of the British hegemonic decline. The neoliberal “globalization

project” was mainly a crisis-management response to a profit squeeze in manufacturing

when Japan and Germany caught up with the U.S. after recovering from World War

II. The rise of the neoconservatives and unilateral “imperial over-reach” was

again crisis management in response to the obviously untenable position of the

U.S. balance of trade that emerged after 1990. These and the rise of new

economic competitors such as China and India are strong similarities to the

earlier period of hegemonic decline. We have also mentioned the expansion

of finance capital that was an important characteristic of the last phase of

both British hegemony and of U.S. hegemony.

There is

another important difference between the periods of British and U.S.; hegemonic

decline that we have not yet mentioned. British decline and the inter-regnum

between the British and U.S. hegemonies occurred during a period of transition

from the coal to the oil energy regime in which the cost of energy was falling

(Podobnik 2006). This time around hegemony is declining during a period

of generally rising costs of non-renewable resources. This energy cost

difference probably slants the system toward chaos.

It is well-known

that the rise of greater centralization and state-formation over the long run of

sociocultural evolution has been made possible by the ability of complex societies

to capture free energy. Hierarchies and greater complexity are expensive in

energy terms. Reductions in the availability of free energy have often been

associated with the collapse of hierarchies and of complex divisions of labor

(Tainter 1988). The coming peaks of resource production probably also raise the

probability of future resource wars, especially in the absence of a strong and

legitimate hegemon or a legitimate global state (Heinberg 2004).

The size difference

between Britain and the U.S. noted above probably slants against a fast

collapse. Even the economic challengers have a vested interested in the current

U.S.-centered financial system and are unlikely to do intentionally do anything

that will undermine it. They own too many U.S. bonds and they depend too much

on the ability of buyers in the U.S. to purchase their products.

And though

U.S. military capability will undoubtedly decline as the ability of the U.S.

economy to support it wanes, this could take a long time, just as it will take

time for new economic centers to develop their military capabilities. The

military and economic size factors do not preclude hegemonic decline, but they

do slow it down and also put off the onset of strong hegemonic rivalries.

Future environmental

catastrophes are likely due to industrialization and population growth

overshoots and overconsumption in the core. Perhaps global warming could be

slowed down by reducing the production of greenhouse gases. With the election

of Barack Obama the U.S. administration signaled strong support, but the

challenges of global adoption and enforcement seem less likely to be met now.

The pressure to use more coal as oil prices continue to rise is likely to overcome

the all the good intentions and international treaties. Environmental

catastrophe will destabilize both the economy and existing political

arrangements. Fragile states will be challenged by internal resource wars (such

as the “blood diamond” wars in Africa) and whole countries will be increasingly

tempted to use armed force to protect or gain access to natural resources. The

collapse of fisheries, the arrival of peak water, deforestation, and pollution

of the streams, ground water and seas and increasing global temperature and sea

level will add to economic problems and exacerbate population pressures. The

environmental dimension of the current situation could conceivably make a

positive contribution to global governance if the response encourages the

formation of international institutions that can organize a cooperative

approach to solving the problems. But they could also make such a solution less

likely by increasing competition over increasingly scarce natural resources. In

the collapse scenario competition and conflict overwhelm cooperation and

institution-building.

Deglobalization will

mean less international trade, less international investment and the

reemergence of greater local and national self-reliance for the production of

goods and services. The rise of transportation costs because of rising

energy prices is one factor that should reduce international trade. Efforts to

reduce carbon emissions will also involve greater regulation of long distance

transportation by air, ship and truck and this will encourage a return to more

local and regional circuits of production and consumption. International

investment will decline if there is greater international conflict because the

risks associated with investments in distant locations will increase.

Greater local

self-reliance will be good for manufacturing and for farmers in places where

imports have been driving locals out of business. But the cost of many goods

will go up. Services may continue to be supplied internationally if the global

communications grid is maintained. It is expensive to maintain the

satellites and cables, but this may be a good investment because long-distance

communication can increasingly substitute for long-distance transportation.

International business and political meetings can be held in cyberspace rather

than by flying people from continent to continent. The carbon footprint of

transoceanic communication is considerably smaller than the carbon footprint of

transportation because information is lighter than people and goods. But

the infrastructure of global communication also relies on international

cooperation, and so the rise of conflict might make communications less

reliable or the big grid might even come down (Kuecker 2007).

A Global Democratic and Sustainable

Commonwealth?

Eventually the

human species will probably escape from the spiral of population pressure and

ecological degradation that has driven human socio-cultural evolution since the

Stone Age. If the demographic transition continues its march through the Global

South this is likely to occur by the year 2100 or so. After the total human

population ceases to rise it will still take time to become adjusted to the

economic, environmental and political problems that will result from a global

population of 8, 10 or 12 million people. And even then history will not end

because human institutional structures will continue to evolve and to generate

new challenges.

But the focus of

this paper is the next several decades. The problem raised by the analysis

above is that the existing institutions of global governance are in crisis and

a new structure that is both legitimate and capable needs to emerge to enable

the humans to deal with the problems that we have created for ourselves. But

what could speed global state formation up such that an effective and

democratic global government could be formed by the middle of the 21st

century?

First recall that in

our understanding of the evolution of global governance world state formation

has been occurring since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. The Concert of

Europe was a multilateral international organization with explicit political

intent – the prevention of future revolutions of the type that emerged in

France in 1789 and the prevention of future Napoleonic projects. The Concert of

Europe was fragile and eventually foundered on the differences between the

rigid conservatism of the Austro-Hungarian Empire led by Prince Metternich, and

the somewhat more enlightened conservatism of the British, led by Lord

Castlereigh. But the emergence of a proto-world state was tried again in the

guise of the League of Nations and once again as the United Nations

Organization. We can notice that the big efforts have followed world wars. And

we should also mention that the United Nations is a very long way from being a

true world state in the Weberian sense of a monopoly of legitimate violence.

All the previous

advances in global state formation have taken place after a hegemon has

declined and challengers have been defeated in a world war among hegemonic

rivals. In Warren Wagar’s (1999) future scenario a global socialist state is

able to emerge only after a huge war among core states in which two thirds of

the world’s population are killed. A similar scenario is also suggested by

Heikki Patomäki (2008). The idea here is that major organizational changes

emerge after huge catastrophes when the existing global governance institutions

are in disarray and need to be rebuilt. But using a global war as a deus ex

machina in a science fiction novel is quite different from planning

and implementing a real strategy that relies on a huge disaster in order to

bring about change – “disaster socialism,” to borrow a phrase suggested by

Naomi Klein’s (2007) discussion of how neoliberal globalizers have been able to

make hay out of tragedies. Obviously political actors who seek to promote the

emergence of an effective and democratic global state must also do all that

they can to try to prevent another war among the great powers. Humanistic

morality must trump the possibility of strategic advantage.

This said, it is

very likely that major calamities will occur in the coming decades regardless

of the efforts of far-sighted citizens and social movements. That is why we

have imagined the collapse scenario above. And it would make both tactical and

strategic sense to have plans for how to move forward if indeed a perfect storm

of calamities were to come about.

But we should also

try to imagine how an effective and democratic global government might emerge

in the absence of a huge calamity. Instead we will suppose that a series of

moderate-sized ecological, economic and political calamities that are somewhat

spaced out in time can suffice to provide sufficient disruption of the existing

world order and motivation for its reconstruction along more cooperative,

effective and democratic lines.

The scenario we have

in mind involves a network of alliances among progressive social movements and

political regimes of countries in the Global South along with some allies in

the Global North. We are especially sanguine about the possibility of

relatively powerful semiperipheral states coming to be controlled by democratic

socialist regimes that can provide resources to progressive global parties and

movements. The long-term pattern of semiperipheral development that has

operated in the socio-cultural evolution of world-systems at least since the

rise of paramount chiefdoms suggests that the “advantages of backwardness” may

again play an important role in the coming world revolution.

Our scenario would

involve a coalescent party-network of the New Global Left that would emerge

from the existing “movement of movements” participating in the World Social

Forum (WSF) process. The first WSF was mainly organized by the Brazilian labor and

landless peasant movements. The global meetings have been held in the Global

South (Brazil, India, Kenya and Senegal).

The long evolution

of the modern world-system has been marked by waves of increasing democracy and

global state formation brought about by a series of world revolutions and

efforts by pragmatic conservatives to construct hegemony based on both coercion

and consent. The form that will best suited for the future is a global

democratic and collectively rational commonwealth. The main source of this

sweeping change is already emerging in the contemporary semiperiphery and the

periphery. The most powerful challenges

to capitalism in the 20th century came from semiperipheral Russia and China,

and the strongest supporters of the contemporary global justice movement are

semiperipheral countries such as Brazil, Mexico and Venezuela and South Africa.

Popular social movements have become increasingly transnational and information

technology makes it much easier to organize global party networks than when

Lenin tried to use a radio transmitter to call activists to the meeting of the

first Comintern. And different forms of capitalism are challenging the

neoliberal form championed by Britain and the United States. Semiperipheral

societies are not constrained to the same degree as older core societies. They

are freer to devise and implement new institutions. China’s “market society” is

a different form of capitalism. Giovanni Arrighi (2006) contended that the

Chinese form may be more capable of dealing effectively with the challenges of

“globalization from below” than the neoliberal form has been. The historically

transformative role of the semiperiphery has been strong in the past and is likely

to be strong in the future.

Bibliography

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth

Century. London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos

and Governance in the Modern World-System: Comparing

Hegemonic

Transitions. Minneapolis:

University ofMinnesota Press.

______________

2006 Adam Smith in Beijing. London: Verso

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Bruce Podobnik 1995 "The next world war: world-system cycles and trends," Journal of World-Systems Research 1:6

Chase-Dunn, C. Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer

2000 “Trade globalization since 1795:

waves of integration in the world-system” American Sociological Review 65,1:77-95

Chase-Dunn, C. Thomas Reifer, Andrew Jorgenson

and Shoon Lio 2005

"The U.S. Trajectory: A Quantitative

Reflection, Sociological Perspectives 48,2: 233-254.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Kirk Lawrence 2010 “ The Next

Three Futures: Another U.S. Hegemony,

Global Collapse or Global Democracy?” Global Society. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows47/irows47.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and R.E. Niemeyer 2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” in Mathias Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational Political Spaces. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/New York

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Hiroko Inoue 2010 “Accelerating Global State Formation

and Democracy” IROWS Working Paper #55

Chase-Dunn C. and Roy Kwon 2010 “Crises and

Counter-Movements in World Evolutionary

Perspective” IROWS Working Paper #60 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows60/irows60.htm

Bonini, Astra 2009 “Is

there Really a ‘Resource Curse’?: Raw Material Wealth and Economic Mobility in

the World System”

Presented at the Annual Meetings of the

American Sociological

Association.

Brenner, Robert 2002 The Boom and the Bubble:

The U.S. in the World Economy. London: Verso.

Bunker, Stephen and Paul Ciccantell 2005 Globalization

and the Race for Resources. Baltimore:

Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Carroll, William K. 2010 The Making of a

Transnational Capitalist Class. London: Zed Press.

Friedman, Jonathan and Christopher

Chase-Dunn (eds.) 2005. Hegemonic

Declines: Present and

Past. Boulder, CO.: Paradigm Press.

Go, Julian 2007 “Global fields and

imperial forms: field theory and the British and American

empires” Paper presented at the annual meeting

of the American Sociological Association, New York.

Goldfrank, Walter L. 1999

“Beyond hegemony” in Volker Bornschier and Christopher Chase-Dunn

(eds.) The Future of Global Conflict. London:

Sage.

Heinberg, Richard. 2004. Powerdown.

Gabriola Island, BC: Island Press.

Hugill, Peter J. 1999 Global

Communications since 1844: Geopolitics and Technology. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Johnson, Chalmers A.

2006. Nemesis : the last days of the American Republic.

New York: Metropolitan Books.

Kennedy, Paul 1987 The Rise and Fall of the

Great Powers, New York: Vintage Books.

Klein, Naomi.

2007. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Henry Holt and

Company.

Kuecker, Glen 2007 “The perfect storm” International

Journal of Environmental, Cultural and Social

Sustainability 3

Lawrence, Kirk. 2009 “Toward a democratic and

collectively rational global commonwealth:

semiperipheral

transformation in a post-peak world-system” in Phoebe Moore and Owen

Worth, Globalization and the Semiperiphery: New York:Palgrave MacMillan.

Lachmann, Richard 2003 “Elite Self-Interest and Economic Decline in Early Modern Europe

American Sociological Review 68, 3: 346-372

McCormick, Thomas J. 1989 America’s Half Century: United States Foreign Policy in the Cold War.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Maddison, Angus.

2001. The World Economy: A

Millennial Perspective. Paris:

Organization of

Economic Cooperation and

Development.

Mann, Michael. 2002. Incoherent

Empire. New

York, NY: Verso.

_____________ 2006 “The Recent Intensification

of American Economic and Military Imperialism:

Are They Connected? Presented at the annual

meeting of the American Sociological

Association, Montreal, August 11.

Patomaki, Heikki 2008 The Political Economy

of Global Security. New York: Routledge.

Podobnik, Bruce 2006 Global Energy Shifts.

Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press

Quigley, Carroll.

1981 The Anglo-American Establishment. New York: Books in Focus

Rasler, Karen and William R. Thompson 1994 The Great Powers and Global Struggle, 1490-

1990. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

Reifer, Thomas E. 2009-10 “Lawyers, Guns and Money: Wall Street

Lawyers, Investment Bankers and

Global Financial Crises, Late 19th to Early 21st Century” Nexus: Chapman's

Journal of Law

& Policy, 15: 119-133

Rennstich, Joachim K. 2001 “The Future of Great

Power Rivalries.” In Wilma Dunaway (ed.) New

Theoretical Directions for the

21st Century World-System New York: Greenwood Press.

_______ 2002 “The

phoenix cycle:global leadership transition in a long-wave

perspective.” Paper

presented

at the annual spring Political Economy of World-Systems conference,

University of California, Riverside, May 3-4.

Robinson, William I. 2004 A Theory of Global

Capitalism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press

_______________

2008. Latin American and Global Capitalism: A Critical Globalization

Perspective.

Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa 2006 The Rise of

the Global Left. London: Zed Press.

Singer, J. David. (1987).

"Reconstructing the Correlates of War Dataset on Material Capabilities of

States,

1816-1985" International Interactions, 14: 115-32.

Sklair, Leslie 2001 The Transnational

Capitalist Class. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Skocpol, Theda 1992 Protecting

soldiers and mothers : the political origins of social policy in the United

States

Cambridge, Mass. :

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Silver,

Beverly and E. Slater 1999. “The Social Origins of World Hegemonies”. In G.

Arrighi, et al

.

Chaos and Governance in the Modern World System. Minneapolis: University

of Minnesota Press, 151-216.

Stokes, Doug and Sam Raphael 2010 Global Energy

Security and American Hegemony Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press

Suter,

Christian 1992

Debt cycles in the world-economy : foreign loans, financial crises, and debt

settlements, 1820-1990 Boulder : Westview Press

_____________2009 “Financial crises and the

institutional evolution of the global debt restructuring regime,

1820-2008” Presented at the PEWS Conference on

“The Social and Natural Limits of Globalization and the Current Conjuncture”

Tainter, Joseph A. 1988. The Collapse of

Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, Peter 1996 The Way the Modern

World Works: Global Hegemony to Global Impasse. New

York:

Wiley.

Wagar, W. Warren. 1999. A Short History of

the Future, 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago

Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984a “The three

instances of hegemony in the history of the capitalist

world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard

Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and Research in Macrosociology,

International Studies in Sociology and Social

Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Wilkinson, David.1991 “Core, peripheries and

civilizations,” Pp. 113-166 in C. Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.)

Core/Periphery

Relations in Precapitalist Worlds.

http://www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/books/c-p/chap4.htm