Continuities

and transformations in the evolution of

world-systems:

Terminal crisis

or a new systemic cycle of accumulation?*

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute for Research

on World-Systems

University of

California-Riverside

![]()

v. 8-5-11 10223

words

Keynote address to be presented at the Vth Brazilian

Colloquium of PEWS, State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), August 8-9, 2011. Conference theme:

“The Contemporary Capitalist World-Economy: Terminal Crisis or Hegemonic

Transition?"

V Colóquio Brasileiro em Economia Política dos

Sistemas-Mundo

A Economia-Mundo

Contemporânea: crise estrutural ou transição hegemônica?

*I am grateful to Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence and Tom

Hall for help with this paper.

This is IROWS Working Paper #70 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows70/irows70.htm

Abstract:

This paper discusses continuities and transformations of systemic

logic and modes of accumulation in world historical and evolutionary

perspective since the Stone Age and in recent years, and the prospects for

systemic transformation in the next several decades. It also considers the

meaning of the recent global financial meltdown by comparing it with earlier

debt crises and periods of collapse. Has this been just another debt crisis

like the ones that have periodically occurred over the past 200 years, or is it

part of the end of capitalism and the transformation to a new and different

logic of social reproduction? I consider the contemporary network of global countermovements

and progressive national regimes that are seeking to transform the capitalist

world-system into a more humane, sustainable and egalitarian civilization and

how the current crisis is affecting the network of counterrmovements and

regimes, including the Pink Tide populist regimes in Latin America and the Arab

Spring movements. I describe how the New Global Left is similar to and

different from earlier global countermovements. The point is to provide a

comparative and evolutionary framework that can discern what is really new

about the current global situation and inform collectively rational responses.

The Comparative Evolutionary World-Systems Perspective

This paper will employ

three different time horizons in the discussion of continuities and

transformations.

1.

50,000 years;

2.

5,000 years;

3.

500 years.

Hall and Chase-Dunn (2006; see also Chase-Dunn and Hall

1997)) have modified the concepts developed by the scholars of the modern

world-system to construct a theoretical perspective for comparing the modern

system with earlier regional world-systems. The main idea is that sociocultural

evolution can only be explained if polities are seen to have been in important

interaction with each other since the Paleolithic Age. Hall and Chase-Dunn

propose a general model of the continuing causes of the evolution of technology

and hierarchy within polities and in linked systems of polities

(world-systems). This is called the iteration model and it is driven by

population pressures interacting with environmental degradation and interpolity

conflict. This iteration model depicts basic causal forces that were operating

in the Stone Age and that continue to operate in the contemporary global system

(see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 6; Fletcher et al 2011). These are the continuities.

The

most important idea that comes out of this theoretical perspective is that

transformational changes in institutions, social structures and developmental

logics are brought about mainly by the actions of individuals and organizations

within polities that are semiperipheral

relative to the other polities in the same system. This is known as the hypothesis of semiperipheral development.

As regional world-systems became spatially larger and the

polities within them grew and became more internally hierarchical, interpolity

relations also became more hierarchical because new means of extracting

resources from distant peoples were invented. Thus did core/periphery

hierarchies emerge. Semiperipherality is the position of some of the polities

in a core/periphery hierarchy. Some of the polities that are located in semiperipheral

positions became the agents that formed larger chiefdoms, states and empires by

means of conquest (semiperipheral marcher polities), and some specialized

trading states in between the tributary empires promoted production for

exchange in the regions in which they operated. So both the spatial and

demographic scale of political organization and the spatial scale of trade

networks were expanded by semiperipheral polities, eventually leading to the

global system in which we now live.

The modern world-system came into being when a formerly

peripheral and then semiperipheral region (

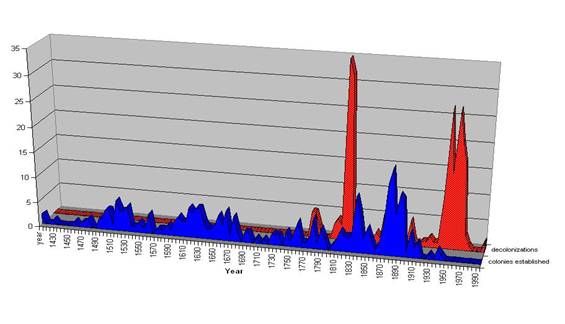

Figure 1: Waves of Colonization and Decolonization Since

1400 - Number of colonies established and number of decolonizations (Source:

Henige (1970))

In

between these periods of hegemony were periods of hegemonic rivalry in which

several contenders strove for global power. The core of the modern world-system

has remained multicentric, meaning that a number of sovereign states ally and

compete with one another. Earlier regional world-systems sometimes experienced

a period of core-wide empire in which a single empire became so large that

there were no serious contenders for predominance. This did not happen in the

modern world-system until the

The sequence of hegemonies can be understood as the evolution

of global governance in the modern system. The interstate system as

institutionalized at the Treaty of Westphalia in 1644 is still a fundamental

institutional structure of the polity of the modern system. The system of

theoretically sovereign states was expanded to include the peripheral regions

in two large waves of decolonization (see Figure 1), eventually resulting in a

situation in which the whole modern system became composed of sovereign

national states.

Each of the hegemonies was larger as a proportion of the

whole system than the earlier one had been. And each developed the institutions

of economic and political-military control by which it led the larger system

such that capitalism increasingly deepened its penetration of all the areas of

the Earth. And after the Napoleonic Wars in which

The political globalization evident in the trajectory of

global governance evolved because the powers that be were in heavy contention

with one another for geopolitical power and for economic resources, but also

because resistance emerged within the polities of the core and in the regions

of the non-core. The series of hegemonies, waves of colonial expansion and

decolonization and the emergence of a proto-world-state occurred as the global

elites tried to compete with one another and to contain resistance from below.

We have already mentioned the waves of decolonization. Other important forces

of resistance were slave revolts, the labor movement, the extension of

citizenship to men of no property, the women’s movement, and other associated

rebellions and social movements.

These movements affected the evolution of global

governance in part because the rebellions often clustered together in time,

forming what have been called “world

revolutions” (Arrighi et al.,

1989). The Protestant Reformation in

The current world revolution of 20xx (Chase-Dunn and

Niemeyer, 2009) will be discussed as the global countermovement in this paper.

The big idea here is that the evolution of capitalism and of global governance

is importantly a response to resistance

and rebellions from below. This has been true in the past and is likely to

continue to be true in the future. Boswell and Chase-Dunn (2000) contend that

capitalism and socialism have dialectically interacted with one another in a positive

feedback loop similar to a spiral. Labor and socialist movements were obviously

a reaction to capitalist industrialization, but also the

Time

Horizons

So what does the comparative and evolutionary

world-systems perspective tell us about continuities and transformations of

system logic? And what can be said about the most recent financial meltdown and

the contemporary global countermovement from the long-run perspectives? Are

recent developments just another bout of financial expansion and collapse and

hegemonic decline? Or do they constitute or portend a deep structural crisis in

the capitalist mode of accumulation. What do recent events signify about the

evolution of capitalism and its possible transformation into a different mode

of accumulation?

50,000

Years

From the perspective of the last 50,000 years the big

news is demographic and ecological. After slowly expanding, with cyclical ups

and downs in particular regions, for millennia the human population went into a

steep upward surge in the last two centuries. Humans have been degrading the

environment locally and regionally since they began the intensive use of

natural resources. But in the last 200 years of industrial production

ecological degradation by means of resource depletion and pollution has become

global in scope, with global warming as the biggest consequence. A demographic

transition to an equilibrium population size began in the industrialized core

countries in the nineteenth century and has spread unevenly to the non-core in

the twentieth century. Public health measures have lowered the mortality rate

and the education and employment of women outside of the home is lowering the

fertility rate. But the total number of humans is likely to keep increasing for

several more decades. In the year 2000 there were about six billion humans on

Earth. But the time the population stops climbing it will be 8, 10 or 12

billion.

This population big bang was made possible by

industrialization and the vastly expanded use of non-renewable fossil fuels.

Fossil fuels are captured ancient sunlight that took millions of years to

accrete as plants and forests grew, died and were compressed into oil and coal.

The arrival of peak oil production is near and energy prices will almost surely

rise again after a long fall. The recent financial meltdown is related to these

long-run changes in the sense that it was brought on partly by sectors of the

global elite trying to protect their privileges and wealth by seeking greater

control over natural resources and by over-expanding the financial sector. But

non-elites are also implicated. The housing expansion, suburbanization, and

larger houses with fewer people in them have been important mechanisms,

especially in the

5,000

Years

The main significance of

the 5,000-year time horizon is to point us to the rise and decline of modes of

accumulation. The story here is that small-scale human polities were integrated

primarily by normative structures institutionalized as kinship relations—the so-called kinship-based

modes of accumulation. The family was the economy and the polity, and the

family was organized as a moral order of obligations that allowed social labor

to be mobilized and coordinated, and that regulated distribution. Kin-based

accumulation was based on shared languages and meaning systems,

consensus-building through oral communication, and institutionalized

reciprocity in sharing and exchange. As kin-based polities got larger they

increasingly fought with one another and polities that developed

institutionalized inequalities had selection advantages over those that did

not. Kinship itself became hierarchical within chiefdoms, taking the form of

ranked lineages or conical clans. Social movements using religious discourses

have been important forces of social change for millennia. Kin-based societies

often responded to population pressures on resources by “hiving-off” -- a

subgroup would emigrate, usually after formulating grievances in terms of

violations of the moral order. Migrations were mainly responses to local

resource stress caused by population growth and competition for resources. When

new unoccupied or only lightly occupied but resource-rich lands were reachable

the humans moved on, eventually populating all the continents except

Around five thousand years ago the first early states and

cities emerged in

A tributary mode became predominant in the Mesopotamian

world-system in the early Bronze Age (around 3000 BCE). The East Asian regional

world-system was still predominantly tributary in the nineteenth century CE.

That is nearly a 5,000-year run. The kin-based mode lasted even longer. All

human groups were organized around different versions of the kin-based modes in

the Paleolithic, and indeed since human culture first emerged with language. If

we date the beginning of the end of the kin-based modes at the coming to

predominance of the tributary mode in

500

Years

This brings us to the capitalist mode, here defined as

based on the accumulation of profits returning to commodity production rather

than taxation or tribute. As we have already said, early forms of capitalism

emerged in the Bronze Age in the form of small semiperipheral states that

specialized in trade and the production of commodities. But it was not until

the fifteenth century that this form of accumulation became predominant in a

regional world-system (

Thus, in comparison with the earlier modes, capitalism is

yet young. It has been around for millennia, but it has been predominate in a

world-system for less than a millennium. On the other hand, many have observed

that social change in general has speeded up. The rise of tribute-taking based

on institutionalized coercion took more than 100,000 years. Capitalism itself

speeds up social change because it revolutionizes technology so quickly that

other institutions are brought along, and people have become adjusted to more

rapid reconfigurations of culture and institutions. So it is plausible that the

contradictions of capitalism may lead it to reach its limits much faster than

the kin-based and tributary modes did.

Transformations

Between Modes

For Immanuel Wallerstein (2011 [1974]), capitalism

started in the long sixteenth century (1450-

1640), grew larger in a series of cycles and upward trends, and is now

nearing “asymptotes” (ceilings) as some of its trends create problems that it

cannot solve. Thus, for Wallerstein the world-system became capitalist and then

it expanded until it became completely global, and now it is coming to face a

big crisis because certain long-term trends cannot be accommodated within the

logic of capitalism (Wallerstein, 2003).

Wallerstein’s evolutionary transformations come at the beginning and at

the end. In there is a focus on expansion and deepening as well as cycles and

trends, but no periodization of world-system evolutionary stages of capitalism

(Chase-Dunn 1998: Chapter 3). . This is very different from both Arrighi’s

depiction of successive (and overlapping) systemic cycles of accumulation and

from the older Marxist stage theories of national development. Wallerstein’s

emphasis is on the emergence and demise of “historical systems” with capitalism

defined as “ceaseless accumulation.” Some of the actors change positions but

the system is basically the same as it gets larger. Its internal contradictions

will eventually reach limits, and these limits are thought to be approaching

within the next five decades.

According

to Wallerstein (2003) the three long-term upward trends (ceiling effects) that

capitalism cannot manage are:

1.

the long-term

rise of real wages;

2.

the long-term

costs of material inputs; and

3.

rising taxes.

All

three upward trends cause the average rate of profit to fall. Capitalists

devise strategies for combating these trends (automation, capital flight, job

blackmail, attacks on the welfare state and unions), but they cannot really

stop them in the long run. Deindustrialization in one place leads to

industrialization and the emergence of labor movements somewhere else (Silver,

2003). The falling rate of profit means that capitalism as a logic of

accumulation will face an irreconcilable structural crisis during the next 50

years, and some other system will emerge. Wallerstein calls the next five

decades “The Age of Transition.”

Wallerstein

sees recent losses by labor unions and the poor as temporary. He assumes that

workers will eventually figure out how to protect themselves against globalized

market forces and the “race to the bottom”. This may underestimate somewhat the

difficulties of mobilizing effective labor organization in the era of

globalized capitalism, but he is probably right in the long run. Global unions

and political parties could give workers effective instruments for protecting

their wages and working conditions from exploitation by global corporations if

the North/South issues that divide workers could be overcome.

Wallerstein

is intentionally vague about the organizational nature new system that will

replace capitalism (as was Marx) except that he is certain that it will no

longer be capitalism. He sees the declining hegemony of the

Stages

of World Capitalist Development: Systemic Cycles of Accumulation

Giovanni

Arrighi’s (1994) evolutionary account of “systemic cycles of accumulation” has

solved some of the problems of Wallerstein’s notion that world capitalism

started in the long sixteenth century and then went through repetitive cycles

and trends. Arrighi’s account is explicitly evolutionary, but rather than

positing “stages of capitalism” and looking for each country to go through them

(as most of the older Marxists did), he posits somewhat overlapping global

cycles of accumulation in which finance capital and state power take on new

forms and increasingly penetrate the whole system. This was a big improvement

over both Wallerstein’s world cycles and trends and the traditional Marxist

national stages of capitalism approach.

Arrighi’s (1994, 2006) “systemic cycles of accumulation”

are more different from one another than are Wallerstein’s cycles of expansion

and contraction and upward secular trends. And Arrighi (2006) has made more out

of the differences between the current period of

Arrighi sees the development of market society in

Arrighi also provides a more explicit analysis of how the

current world situation is similar to and different from the period of

declining British hegemonic power before World War I ( see summary in

Chase-Dunn and Lawrence 2011:147-151).

Wallerstein’s

version is more apocalyptic and more millenarian. The old world is ending. The

new world is beginning. In the coming systemic bifurcation what people do may

be prefigurative and causal of the world to come. Wallerstein agrees with the

analysis proposed by the students of the New Left in 1968 (and large numbers of

activists in the current global justice movement) that the tactic of taking

state power has been shown to be futile because of the disappointing outcomes

of the World Revolution of 1917 and the decolonization movements (but see

below).

Economic

Globalization

Regarding

the issue of whether or not the recent meltdown is itself a structural crisis

or the beginning of a long process of transformation, it is relevant to examine

recent trends in economic globalization. Is there yet any sign that the world

economy has entered a new period of deglobalization of the kind that occurred

in the first half of the twentieth century?

Immanuel

Wallerstein contends that globalization has been occurring for five hundred

years, and so there is little that is importantly new about the so-called stage

of global capitalism that is alleged to have emerged in the last decades of the

twentieth century. Well before the emergence of globalization in the popular

consciousness, the world-systems perspective focused on the world economy and

the system of interacting polities, rather than on single national societies. Globalization,

in the sense of the expansion and intensification of larger and larger

economic, political, military and information networks, has been increasing for

millennia, albeit unevenly and in waves. And globalization is as much a cycle

as a trend (see Figure 5). The wave of global integration that has swept the

world in the decades since World War II is best understood by studying its

similarities and differences with the waves of international trade and foreign

investment expansion that have occurred in earlier centuries, especially the

last half of the nineteenth century.

Wallerstein

has insisted that

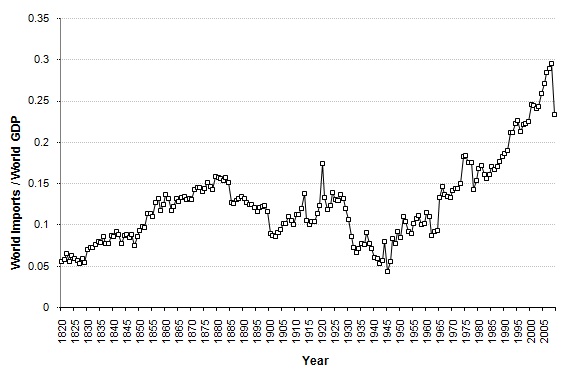

Figure 2: Trade Globalization 1820–2009: World Imports as a Percentage of World GDP (Sources: Chase-Dunn et al. (2000); World Bank (2011))

Figure

2 is an updated version of the trade globalization series published in

Chase-Dunn et al., (2000). It shows

the great nineteenth century wave of global trade integration, a short and

volatile wave between 1900 and 1929, and the post-1945 upswing that is

characterized as the “stage of global capitalism.” The figure indicates that

globalization is both a cycle and a bumpy trend. There have been significant

periods of deglobalization in the late nineteenth century and in the first half

of the twentieth century. Note the steep decline in the level of global trade

integration in 2009.

The long-term upward trend has been bumpy, with

occasional downturns such as the one shown in the 1970s. But the downturns

since 1945 have all been followed by upturns that restored the overall upward

trend of trade globalization. The large decrease of trade globalization in the

wake of the global financial meltdown of 2008 represents a 21% decrease from

the previous year, the largest reversal in trade globalization since World War

II. The question is whether or not this sharp decrease represents a reversal in

the long upward trend observed over the past half century. Is this the

beginning of another period of deglobalization?

The Financial

Meltdown of 2007-2008

The

recent financial crisis has generated a huge scholarly literature and immense

popular reflection about its causes and its meaning for the past and for the

future of world society. This contribution is intended to place the current

crisis, and the contemporary network of transnational social movements and

progressive national regimes, in world historical and evolutionary perspective.

The main point is to accurately determine the similarities and differences

between the current crisis and responses with earlier periods of dislocation

and breakdown in the modern world-system and in earlier world-systems.

This analysis is reported

in Chase-Dunn and Kwon (2011). The conclusions are that financial crises are

business as usual for the capitalist world-economy. The theories of a “new

economy” and “network society” were mainly justifications for financialization.

The big difference is the size of the bubble and the greater dependence of the

rest of the world on the huge

The

World Revolution of 20xx

The contemporary world revolution is similar to earlier

ones, but also different. Our conceptualization of the New Global Left includes

civil society entities: individuals, social movement organizations, non-governmental

organizations (NGOs), but also political parties and progressive national

regimes. In this chapter we will focus mainly on the relationships among the

movements and the progressive populist regimes that have emerged in Latin

America in the last decade and on the Arab Spring that began in

The boundaries of the progressive forces that have come

together in the New Global Left are fuzzy and the process of inclusion and

exclusion is ongoing (

The New Global Left has emerged as resistance to, and a critique of, global capitalism (Lindholm and Zuquete, 2010). It is a coalition of social movements that includes recent incarnations of the old social movements that emerged in the nineteenth century (labor, anarchism, socialism, communism, feminism, environmentalism, peace, human rights) and movements that emerged in the world revolutions of 1968 and 1989 (queer rights, anti-corporate, fair trade, indigenous) and even more recent movements such as the slow food/food rights, global justice/alterglobalization, antiglobalization, health-HIV and alternative media (Reese et al., 2008). The explicit focus on the Global South and global justice is somewhat similar to some earlier instances of the Global Left, especially the Communist International, the Bandung Conference and the anticolonial movements. The New Global Left contains remnants and reconfigured elements of earlier Global Lefts, but it is a qualitatively different constellation of forces because:

1. there are new elements,

2.

the old

movements have been reshaped, and

3. a new technology (the Internet) is being used to mobilize protests in real time and to try to resolve North/South issues within movements and contradictions among movements.

There has also been a learning process in which the

earlier successes and failures of the Global Left are being taken into account

in order to not repeat the mistakes of the past. Many social movements have

reacted to the neoliberal globalization project by going transnational to meet

the challenges that are obviously not local or national (Reitan, 2007). But

some movements, especially those composing the Arab Spring, are focused mainly

on regime change at home. The relations within the family of antisystemic

movements and among the Latin American Pink Tide populist regimes are both

cooperative and competitive. The issues that divide potential allies need to be

brought out into the open and analyzed in order that cooperative efforts may be

enhanced and progressive global collective action may become more effective.

The Pink Tide

The World Social Forum (WSF) is not the only political force that demonstrates the rise of the New Global Left. The WSF is embedded within a larger socio-historical context that is challenging the hegemony of global capital. It was this larger context that facilitated the founding of the WSF in 2001. The anti-IMF protests of the 1980s and the Zapatista rebellion of 1994 were early harbingers of the current world revolution that challenged the neoliberal capitalist order. And the World Social Forum was founded explicitly as a counter-hegemonic project vis-à-vis the World Economic Forum (an annual gathering of global elites founded in 1971).

World history has proceeded in a series of waves.

Capitalist expansions have ebbed and flowed, and egalitarian and humanistic

countermovements have emerged in a cyclical dialectical struggle. Polanyi

(1944) called this the double-movement, while others have termed it a “spiral

of capitalism and socialism.” This spiral of capitalism and socialism describes

the undulations of the global economy that have alternated between expansive

commodification throughout the global economy, followed by resistance movements

on behalf of workers and other oppressed groups (Boswell and Chase-Dunn, 2000).

The Reagan/Thatcher neoliberal capitalist globalization project extended the

power of transnational capital. This project has reached its ideological and

material limits. It has increased inequality within some countries, exacerbated

rapid urbanization in the Global South (so-called Planet of Slums [

A global network of countermovements has arisen to

challenge neoliberalism, neoconservatism and corporate capitalism in general.

This progressive network is composed of increasingly transnational social

movements as well as a growing number of populist governments in

An important difference between these and many earlier Leftist regimes in the non-core is that they have come to head up governments by means of popular elections rather than by violent revolutions. This signifies an important difference from earlier world revolutions. The spread of electoral democracy to the non-core has been part of a larger political incorporation of former colonies into the European interstate system. This evolutionary development of the global political system has mainly been caused by the industrialization of the non-core and the growing size of the urban working class in non-core countries (Silver, 2003). While much of the “democratization” of the Global South has consisted mainly of the emergence of “polyarchy” in which elites manipulate elections in order to stay in control of the state (Robinson, 1996), in some countries the Pink Tide Leftist regimes have been voted into power. This is a very different form of regime formation than the road taken by earlier Leftist regimes in the non-core. With a few exceptions earlier Left regimes came to state power by means of civil war or military coup.

The ideologies of the Latin American Pink Tide regimes

have been both socialist and indigenist, with different mixes in different

countries. The acknowledged leader of the Pink Tide as a distinctive brand of

leftist populism is the Bolivarian Revolution led by Venezuelan President Hugo

Chavez. But various other forms of progressive political ideologies are also

heading up states in

Most

of these regimes are supported by the mobilization of historically subordinate

populations including the indigenous, poor, and women. The rise of the

voiceless and the challenge to neoliberal capitalism seemed to have its

epicenter in

The rise of the left has engulfed nearly all of South

America and a considerable portion of Central America and the

President Hugo Chavez of

The early Structural Adjustment Programs imposed by the

International Monetary Fund in Latin America in the 1980s were instances of

“shock therapy” that emboldened domestic neoliberals to attack the “welfare

state,” unions and workers parties. In many countries these attacks resulted in

downsizing and streamlining of urban industries, and workers in the formal

sector lost their jobs and were forced into the informal economy, swelling the

“planet of slums” (

The very existence of the World Social Forum owes much to

the Pink Tide regime in

The relations between the progressive transnational

social movements and the regimes of the Pink Tide have been both collaborative and

contentious. We have already noted the important role played by the Brazilian

Workers’ Party in the creation of the World Social Forum. But many of the

activists in the movements see involvement in struggles to gain and maintain

power in existing states as a trap that is likely to simply reproduce the

injustices of the past. These kinds of concerns have been raised by anarchists

since the nineteenth century, but autonomists from

The older Leftist organizations and movements are often

depicted as hopelessly Eurocentric and undemocratic by the neo-anarchists and

autonomists, who instead prefer participatory and horizontalist network forms

of democracy and eschew leadership by prominent intellectuals as well as by

existing heads of state. Thus when Lula, Chavez and Morales have tried to

participate in the WSF, crowds have gathered to protest their presence. The

organizers of the WSF have found various compromises, such as locating the

speeches of Pink Tide politicians at adjacent, but separate, venues. An

exception to this kind of contention is the support that European autonomists

and anarchists have provided to Evo Morales’s regime in

The

Meltdown and the Countermovements

What have been the effects of the global financial

meltdown on the countermovements and the progressive national regimes? The

World Social Forum slogan that “Another World Is Possible” seems far more

appealing now than when the capitalist globalization project was booming. Critical

discourse has been taken more seriously by a broader audience. Marxist

geographer, David Harvey, has been interviewed on the BBC. The millenarian

discourses of the Pink Tide regimes and the radical social movements seem to be

at least partly confirmed. The “end of history” triumphalism and theories of

the “new economy” seem to have been swept into the dustbin. The world-systems

perspective has found greater support, at least among earlier critics such as

the more traditional Marxists. The insistence of Wallerstein, Arrighi, and

others that

On a more practical level, most of the social movement

organizations and NGOs have had more difficulty raising money, but this has

been counterbalanced by increased participation (Allison et al., 2011). The

environmental movement has received some setbacks because the issue of high

unemployment has come to the fore. The

The

Arab Spring

The

movements that have swept the Arab world since December of 2010 are also part

of the world revolution of 20xx and they may play a role in the New Global

Left. As in earlier world revolutions, contagion and new technologies of

communication have been important elements. And as in earlier world

revolutions, rather different movements stimulated by different local

conditions converge in time to challenge the powers that be. The Arab Spring

movements have been rather different from the global justice movements. Their

targets have mainly been authoritarian national regimes rather than global

capitalism. Youthful demonstrators have used Facebook to organize mainly peaceful protests that have succeeded

in causing several old entrenched regimes to step down. The countries in which

these movements have succeeded are not the poorest countries in Africa and the

The

issues raised by the Arab Spring movements have mainly been about national

democracy, not global justice. But the example of masses of young people

rallying against unpopular regimes now seems to be spreading to the second-tier

core states of

Conclusions

So

do recent developments constitute the beginning of the terminal crisis of

capitalism or another systemic cycle of accumulation. As mentioned above,

predominant capitalism has not been around very long from the point of view of

the succession of qualitatively different logics of social reproduction. But

capitalism itself has speeded up social change and its contradictions do seem

to be reaching levels that cannot be fixed. Declarations of imminent

transformation may be useful for mobilizing social movements, but the real

problem is the clearly specify what is really wrong with capitalism and how

these deficiencies can be fixed. Whether or not we are in the midst of a

qualitative transformation this task will need to be accomplished.

Regarding a new systemic cycle of

accumulation, Arrighi’s bet on the significance of the rise of

The

But

things are more interesting in the semiperiphery and the Global South. So far

the

Bibliography

Allison,

Juliann, Ian Breckenridge-Jackson, Katja M. Guenther, Ali Lairy, Elzabeth

Schwarz, ellen Reese, Miryam E. Ruvalcaba and Michael Walker 2011 “Is the

economic crisis a crisis for social justice activism/” Policy Matters 5,1 (Spring) http://policymatters.ucr.eduAlexis

Alvarez, Hiroko Inoue, Kirk Lawrence, Evelyn Courtney, Edwin Elias, Tony Roberts and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2011 “Semiperipheral Development and Empire Upsweeps Since the Bronze Age” IROWS Working Paper #56 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows56/irows56.htm

Amin,

Samir. 1997. Capitalism in an Age of Globalization.

Arrighi,

Giovanni. 1994 The Long Twentieth Century.

——. 2006. Adam

Smith in

——, Terence K. Hopkins, and Immanuel Wallerstein.

1989. Antisystemic Movements.

—— and Beverly Silver. 1999. Chaos and Governance

in the Modern World-System: Comparing Hegemonic Transitions.

Barbosa,

Luis C. and Thomas D. Hall 1985 “Brazilian slavery and the world economy” Western Sociological Review 15,1:

99-119.

Bergesen,

Albert and Ronald Schoenberg. 1980. “Long waves of colonial expansion and

contraction 1415-1969” Pp. 231-278 in Albert Bergesen (ed.) Studies of the

Modern World-System.

Bornschier,

Volker. 2010. “On the evolution of inequality in the world system” in Christian

Suter (ed.) Inequality Beyond Globalization: Economic Changes. Social Transformations

and the Dynamics of Inequality.

Bornschier,

Volker and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.) The Future of Global Conflict.

Boserup,

Ester1981. Population and Technological Change.

Boswell,

Terry and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral of Capitalism and

Socialism: Toward Global Democracy. Boulder, CO.: Lynne Rienner.

Brenner,l

Robert 2002 The Boom and the Bubble: The

Bunker,

Stephen and Paul Ciccantell 2005 Globalization and the Race for Resources.

Carroll,

William K. 2010 The Making of a

Transnational Capitalist Class.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher 1998 Global Formation: Structures of the

World- Economy.

——. Orfalea Lecture on the evolution of societal

organization. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxNgOkU6NzY

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Salvatore Babones (eds.) Global Social Change: Historical and

Comparative Perspectives.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Terry Boswell 2009 “Semiperipheral development and global democracy” in

Phoebe Moore and Owen Worth, Globalization and the Semiperiphery:

Chase-Dunn,

C. Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 “Trade globalization since 1795: waves

of integration in the world-system” American Sociological Review 65, 1: 77-95.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Chase-Dunn, C. Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence and

Hiroko Inoue 2011 “Last of the hegemons:

Chase-Dunn C. and Roy Kwon 2011 “Crises and

Counter-Movements in World

Evolutionary Perspective” in Christian Suter and Mark Herkenrath (Eds.) The Global Economic Crisis: Perceptions and Impacts (World Society Studies 2011).Wien/Berlin/Zürich: LIT Verlag

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Kirk Lawrence 2011 “The Next Three Futures, Part One: Looming Crises of

Global Inequality, Edcological Degradation, and a Failed System of Global

Governance” Global Society 25,2:137-153

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows47/irows47.htm

Chase-Dunn

C. and Ellen Reese 2007 “Global political party formation in world historical perspective”

in Katarina Sehm-Patomaki & Marko Ulvila eds. Global Political Parties.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and R.E. Niemeyer 2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” Pp. 35-57 in Mathias, Albert, Gesa

Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational

Political Spaces. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/

Chase-Dunn, C. and Bruce Lerro 2008 “Democratizing Global Governance: Strategy and Tactics in Evolutionary Perspective” IROWS Working Paper #40

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Bruce Podobnik 1995 “The Next World War: World- System Cycles and Trends” Journal

of World-Systems Research,Volume 1, Number 6, http://jwsr.ucr.edu/archive/vol1/v1_n6.php

Cioffi,

John W. 2010 “The Global

Financial Crisis: Conflicts of Interest, Regulatory Failures, and Politics” Policy

Matters 4,1 http://policymatters.ucr.edu/

Collins,

Randall 2010 “Geopolitical conditions of internationalism, human rights and

world law” Journal of Globalization

Studies 1,1: 29-45.

Davis,

Mike 2006 Planet of Slums.

Dymski, Gary A. 2009 “Sources & Impacts of the Subprime Crisis: From Financial Exploitation to Global Economic Meltdown” UCR Program on Global Studies University of California-Riverside, 2008-2009 Colloquium Series Tuesday, January 13

Evans, Peter B. 1979 Dependent Development: the alliance of

multinational, state and local capital in

Fletcher, Jesse B;

Apkarian, Jacob; Hanneman, Robert A; Inoue, Hiroko; Lawrence, Kirk; Chase-Dunn,

Christopher. 2011”Demographic

Regulators in Small-Scale World-Systems” Structure and Dynamics 5,

1

Frank, Andre Gunder 1998 Reorient:: Global Economy in the Asian Age.

Goldfrank, Walter L. 1999 “Beyond hegemony” in Volker

Bornschier and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.) The Future of Global Conflict.

Goldstone,

Jack A. 1991 Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World.

Gramsci,

Antonio 1971 Selections for the Prison Notebooks.

Grinen,

Leonid and Andrey Kortayev 2010 “Will the

global crisis lead to global transformations?: the global financial system—pros

and cons” Journal of Globalization Studies

1,1:70-89 (May).

Hall,

Thomas D. and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2006 “Global social change in the long

run” Pp. 33-58 in C. Chase-Dunn and S. Babones (eds.) Global Social Change: Historical and Comparative Perspectives.

Hamashita,

Takeshi 2003 “Tribute and treaties: maritime

Harvey,

David 1982 The Limits to Capital.

Cambridge, MA: Blackwell

——. 2010 The

Enigma of Capital.

——. 2010 “The crisis of capitalism” http://davidharvey.org/2010/05/video-the-crises-of-capitalism-at-the-rsa/

Henige,

David P. 1970 Colonial Governors from the Fifteenth Century to the Present.

Madison, WI.: University of Wisconsin Press.

Henwood,

Doug 1997 Wall Street : how it works and

for whom London:

Verso

Hilferding,

Rudolf 1981 Finance

Capital: A Study Of The Latest Phase Of Capitalist Development. London : Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Hobsbawm,

Eric 1994 The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991.

New York: Pantheon.

Kamlani, Deirdre Shay 2008 “The four faces

of power in sovereign debt restructuring: Explaining Bargaining Outcomes

Between Debtor States and Private Creditors Since 1870” Unpublished Thesis,

London School of Economics.

Klein, Naomi. 2007 The

Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Henry Holt and

Company.

Korzeniewicz, Roberto P. and Timothy Patrick Moran.

2000. “Measuring World Income Inequalities.” American Journal of Sociology 106(1):

209-221.

Korzeniewicz,

Roberto P and Timothy Patrick Moran. 2009. Unveiling Inequality: A World Historical

Perspective. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Krippner,

Greta R. 2010 “ The political economy of financial exuberance,” , Pp.141-173 in

Michael Lounsbury (ed.) Markets on Trial: The Economic Sociology of the U.S.

Financial Crisis: Part B (Research in the Sociology of Organizations, Volume

30) Bingley, UK: Emerald Group

Publishing Limited

Kuecker,

Glen 2007 “The perfect storm” International Journal of Environmental,

Cultural and Social Sustainability 3

Lawrence, Kirk. 2009 “Toward a democratic and collectively rational

global commonwealth: semiperipheral transformation in a post-peak world-system”

in Phoebe Moore and L Owen Worth, Globalization and the Semiperiphery: New

York: Palgrave MacMillan.

_____________ 2006 “The Recent Intensification of American Economic and Military Imperialism: Are They Connected? Presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Montreal, August 11.

Martin, William G. et al 2008 Making Waves: Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005. Boulder, CO: ParadigmMitchell,

Brian R. 1992. International Historical

Statistics: Europe 1750-1988. 3rd edition. New York: Stockton.

Mitchell,

Brian R. 1993. International Historical

Statistics: The Americas 1750-1988. 2nd edition. New York:

Stockton.

Mitchell,

Brian R. 1995. International Historical

Statistics: Africa, Asia, and Oceania 1750-1988. 2nd edition.

New York: Stockton.

Monbiot,

George 2003 Manifesto for a New World Order. New York: New Press

Patomaki,

Heikki 2008 The Political Economy of Global Security. New York:

Routledge.

Pfister, Ulrich and Christian Suter 1987:

"International financial relations as part of the world

system." International Studies

Quarterly, 31(3), 23-72.

Polanyi,

Karl 1944 The great transformation. New York: Farrar &

Rinehart

Podobnik, Bruce 2006 Global Energy Shifts. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Reese, Ellen, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Kadambari Anantram,

Gary Coyne, Matheu Kaneshiro, Ashley N. Koda, Roy Kwon, and Preeta Saxena.

2008. “Research Note: Surveys of World Social Forum Participants Show Influence

of Place and Base in the Global Public Sphere.” Mobilization: An International

Journal 13(4): 431-445. Revised version

in A Handbook of the World Social Forums

Editors: Jackie Smith,

Scott

Byrd, Ellen Reeseand Elizabeth Smythe. Paradigm Publishers

Reifer, Thomas E. 2009-10 “Lawyers, Guns and Money: Wall Street Lawyers,

Investment Bankers and Global Financial Crises, Late 19th to Early 21st

Century” Nexus:

Chapman's Journal of Law & Policy,

15: 119-133

Reinhart, Carmen M. and Kenneth S. Rogoff 2008

“This time is different: a panoramic view of eight centuries of financial

crises” NBER Working Paper 13882 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13882

Reitan, Ruth 2007 Global Activism. London:

Routledge.

Robinson,

William I 1996 Promoting Polyarchy: Globalization, US Intervention and

Hegemony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——. 2008. Latin America and Globalization.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Unversity Press

——. 2010 “The crisis of global capitalism: cyclical, structural or systemic?” Pp. 289-310 in Martijn Konings (ed.) The Great Credit Crash. London:Verso.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa 2006 The Rise of the Global Left. London: Zed Press.Sen, Jai, and Peter Waterman (eds.) World Social Forum: Challenging Empires. Montreal: Black Rose BooksSmith, Jackie Marina Karides, Marc Becker, Dorval Brunelle, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Donatella della Porta, Rosalba Icaza Garza, Jeffrey S. Juris, Lorenzo Mosca, Ellen Reese, Peter Jay Smith and Rolando Vazquez 2007 Global Democracy and the World Social Forums. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers

Silver, Beverly J. 2003 Forces of Labor:

Workers Movements and Globalization Since 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Suter, Christian 1987 "Long waves in core-periphery

relationships within the international financial

system: debt-default cycles of sovereign borrowers." Review, 10(3).

——. 1992 Debt cycles in the world-economy : foreign

loans, financial crises, and debt settlements, 1820-1990 Boulder : Westview Press

——. 2009 “Financial crises and the institutional

evolution of the global debt restructuring regime, 1820-2008” Presented at the

PEWS Conference on “The Social and Natural Limits of Globalization and the

Current Conjuncture” University of San Francisco, August 7.

Taylor,

Peter 1996 The Way the Modern World Works: Global Hegemony to Global

Impasse. New

York: Wiley.

Turchin, P. 2003. Historical dynamics: why

states rise and fall. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Turchin,

Peter and Sergey A. Nefedov 2009 Secular Cycles. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press

Turner,

Jonathan H. 2010 Principles of Sociology, Volume 1 Macrodynamics. Springer

Verlag

Wallerstein,

Immanuel. 1984a “The three instances of hegemony in the history of the capitalist

world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and Research

in Macrosociology, International

Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

——. 1984b The politics of the world-economy:

the states, the movements and the civilizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——. 1998.

Utopistics. or, historical choices of the

twenty-first century.

New York: The New Press.

——.

2003 The Decline of American Power. New York: New Press

——. 2010 “Contradictions in the Latin American Left” Commentary No. 287, Aug. 15, http://www.iwallerstein.com/contradictions-in-the-latin-american-left/

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2011 [1974] The Modern World-System, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press.

World Bank. 2009. World Development Indicators [CD ROM]. Washington DC: World Bank

World Bank 2011. World

Development Indicators [online]. Washington DC: World Bank.