the Intermovement

Network in the U.S. social forum process:

Comparing

Atlanta 2007 with Detroit 2010[1]

Christopher Chase-Dunn Ian

Breckenridge-Jackson

Department of Sociology and Institute for Research on World-Systems

(IROWS)

University of

California-Riverside,

Draft v. 2-3-14 6932 words

Abstract:

This article compares survey results of attendees at the United States Social

Forum meeting in Atlanta in 2007 with surveys from the U.S. Social Forum in

Detroit in 2010 to study continuities and changes in the sizes and links among

social movements. Respondents indicated their active involvement in a list of twenty-seven

social movement themes. Over half of the respondents indicated active involvement

in two or more movements. Using the overlaps among movements based on shared members

we infer the structure of links among the movements. We use formal network

analysis to examine continuities and changes in the structure of movement connections.

Our findings demonstrate. important continuities and some significant changes

in the sizes and the patterns of movement interconnections from 2007 to 2010.

We find that the overall structure

of the network of interconnected movements did not change, and was also quite

similar to that found at global meetings of the World Social Forum. In Detroit

human rights and antiracism, both of which had the highest connectedness scores

in Atlanta, significantly increased

their relative connectedness to become the major hubs linking most of the other

movement themes. But we also found that environmentalism increased both its

centrality and size, while the peace movement decreased both its size and its

centrality in the network of movement interconnections.

This article examines changes in the

organizational space of the social movements that are involved in the United

States Social Forum (USSF) process. In

this study we seek to understand the structure of connections among progressive

movements and how those connections may be evolving over time. For this purpose

we analyze results obtained from surveys of participants in the U.S. Social

Forum that was held in Atlanta in June of 2007 with a comparable survey that

was carried out at the U.S. Social Forum meeting in Detroit in June of 2010. We examine the contours of the social

movement connections found among USSF participants, and how these are changing

over time.

The Social Forum process began when

the World Social Forum was founded in Porto Alegre,

Brazil in 2001. The global, regional and local Social Forum meetings are meant

to be spaces in which movement activists can collaborate and organize

campaigns. The first national Social Forum in the United States was held in

June of 2007 in Atlanta, Georgia. We carried out a written survey of the

attendees at that meeting and another very similar survey at the USSF held in

Five hundred sixty-nine of the attendees

at the 2010 USSF in

There were more students (25% of respondents) and fewer

full-time employees (33%) than one might expect. The group was highly educated,

with more than one participant in four having a graduate or other advanced

degree. The median household income of respondents was very similar to that of

the U.S. as a whole (about $40,000 a year). As might be expected, most respondents were

from the United States., although many were born outside the

Comparing the surveyed attendees at the USSF10 with those

surveyed at the USSF07 in

There is a large scholarly

literature on networks, coalitions and alliances among social movements (e.g.

Carroll and Ratner 1996; Krinsky and Reese 2006; Obach 2004; Reese, Petit, and Meyer 2008; Rose 2000; Van

Dyke 2003; Meyer and Corrigall-Brown 2005; Juris 2008).

One of the big findings is that

coalitions among social movement organizations tend to emerge and strengthen

when the values or constituencies that are held dear by activists are strongly

threatened by repression or by counter-movements (Van Dyke 2003; Mason 2013). Our study is theoretically motivated by this

literature as well as by the analysis of world revolutions (Wallerstein

2004; Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000; Mason 2013).

The social movement literature on coalitions studies several different

levels of cooperation and differentiates coalitions that occur within broad

movement themes from less frequent coalitions that occur across the boundaries

of different social movements – inter-movement coalitions (Van Dyke and McCammon 2010). Our study is of these less frequent

inter-movement links as indicated by the co-participation of individual

activists.

Social movement organizations may be

linked with one another both informally and formally. At the formal level,

organizations may provide legitimacy and support to one another, and they may

collaborate in joint action. Informally, movements can be connected by the

choices of individuals to be active participants in two or more movements. These informal linkages enable learning and influence to

pass among movement organizations, even when there may be limited official

interaction or leadership coordination. We

assess the extent and pattern of informal linkages among movements by surveying

attendees at the USSF as to their active involvement in a designated set of

movement themes and by focusing on those individuals who profess active

involvement in two or more movements.

Those respondents who are involved

in more than one movement are more likely to be synergists (Carroll and Ratner

1996; Wallerstein 2004) who see the larger connections

among different movements and who may be more likely to play an active role in

facilitating collective action within the larger “movement of movements.”

The extent and pattern of linkages among

the memberships of social movement organizations may be highly consequential. Social

movement research has repeatedly found that network connections among

individuals are the most important factor explaining movement participation

(Snow and Soule 2010). Some forms of

connection [e.g. “small world” networks, (Watts 2003)] allow the rapid spread

of information and influence while other network structures (e.g. division into

“factions”) inhibit communication and make coordinated action more difficult. The

ways in which social movements are linked with one another can facilitate or

obstruct efforts to organize cross-movement collective action. Formal network

analysis can reveal whether or not the structure of alliances contains separate

subsets with few ties, or the extent to which the network is organized around

one or several central movements that connect the other movements by means of

overlapping members.

The

Social Forum Surveys

The

University of California-Riverside Transnational Social Movement Research

Working Group has conducted four paper surveys of attendees at Social Forum

events. We used previous studies of the global justice movements by Starr

(2000) and Fisher and Ponniah (2003) to construct our

original list of eighteen social

movement themes that we believed would be represented at the January 2005 World

Social Forum (WSF) in Porto Alegre, Brazil. We also

conducted a survey at the WSF in Nairobi, Kenya in 2007 in which we used most

of these same movement themes, but we separated human rights from anti-racism

and we added eight additional movement themes (development, landless,

immigrant, religious, housing, jobless, open source, and autonomous). We used

this same larger list of 27 movement themes at the US Social Forum (USSF) in

Atlanta in July of 2007.[5]

In what follows we study changes and

continuities in the relative sizes of movements and changes in the network

centrality (multiplicative coreness) of movements.

Relative movement size is indicated by the percentage of surveyed attendees who

claim to be actively involved in each movement theme. We asked each attendee to check whether or

not they identified with, or were actively involved in each of the movement

themes with following item on our survey questionnaire:

(Check all of the following

movements with which you (a) strongly identify with and/or are actively

involved in:

(a) strongly

identify:

(b) are actively involved in:

1. oAlternative

media/culture

oAlternative media/culture

2. oAnarchist

oAnarchist

3. oAnti-corporate

oAnti-corporate

4. oAnti-globalization oAntiglobalization

5. oAntiracism

oAntiracism

6. oAlternative Globalization/Global

Justice

oAlternative

Globalization/Global Justice

7. oAutonomous

oAutonomous

8. oCommunist

oCommunist

9. oDevelopment aid/Economic development

oDevelopment aid/Economic development

10.oEnvironmental

oEnvironmental

11.oFair Trade/Trade

Justice

oFair Trade/Trade Justice

12.oFood Rights/Slow

Food

oFood Rights/Slow Food

13.oGay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender/Queer Rights oGay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender/Queer Rights

14.oHealth/HIV

oHealth/HIV

15.oHousing

rights/anti-eviction/squatters

oHousing rights/anti-eviction/squatters

16.oHuman

Rights

oHuman Rights

17.oIndigenous

oIndigenous

18.oJobless workers/welfare

rights

oJobless workers/welfare rights

19.oLabor

oLabor

20.oMigrant/immigrant

rights

oMigrant/immigrant rights

21.oNational Sovereignty/National

Liberation oNational Sovereignty/National Liberation

22.oOpen-Source/Intellectual Property

Rights oOpen-Source/Intellectual Property Rights

23.oPeace/Anti-war

oPeace/Anti-war

24.oPeasant/Farmers/Landless/Land-reform

oPeasant/Farmers/Landless/Land-reform

25.oReligious/Spiritual

oReligious/Spiritual

26.oSocialist

oSocialist

27.oWomen's/Feminist

oWomen's/Feminist

28.oOther(s), Please list

___________________ oOther(s), Please

list _________________

Table 1 below reports the numbers and

the percentages that these numbers reflect of all the actively involved movement choices. This is an indicator of

relative movement size, and changes in the percentages tell if a movement theme

has grown and or declined in popularity among the attendees as the USSF

meetings. Multiplicative coreness is a formal network

statistic that is calculated from the network affiliation matrices presented

below. Coreness tells how central a network node

(movement theme) is in the network of movement links based on the overlapping

involvements of individual attendees. A movement that is greatly tied to many

other movements by having co-members with them, and one that is the sole link

between more peripheral movements and the core of centrally located movements

gets a high score on the coreness measure. Size and coreness are

positively correlated because a larger movement is more likely to have more

ties with other movements. But size and coreness are

not perfectly correlated (see Table 5 below).

Movement Sizes at the US Social Forum

We asked participants which of these movement themes they

strongly identified with, and with which were they actively involved as

shown above. Table 1 shows the movement themes

and the numbers of participants who said they were actively involved in each of

the movements in 2007 and 2010. The number of choices of movements is

considerably larger than the total number of attendees surveyed because over

half of the respondents indicated active involvement if more than one movement

theme.

The size distribution of movement

selections in Table 1 shows that the largest movements represented at the

Atlanta meeting in 2007 were antiracism ( with 7.73%

of the choices), peace/anti-war ( with 7.57% of the choices) and human rights

(7.36 % of the choices). This means that nearly 8% of all the 2419 choices of

movement active involvement were claiming active involvement in antiracism. The

movements in Table 1 are ranked according to their percentages in Atlanta. In

Detroit in 2010 antiracism was still the largest, but the second largest was now

the environmental movement. The Pearson’s r correlation between the percentages

of the movement themes in 2007 and 2010 is .88.

The last column in Table 1 shows the

percentage growth or decline for each movement theme between 2007 and

2010. Peace/Anti-war and Global Justice

declined, as did Indigenous. We suspect that the peace movement activism

declined because of a combination of things that happened between 2007 and

2010. In the U.S. presidential election of 2008 Barack Obama had promised to

stop the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and by 2010 it was clear that these wars

were winding down. The huge global anti-war movement that had emerged in 2003 (Meyer.

and Corrigall-Brown 2005; Reese, Petit, and Meyer 2008) had

subsided. Most observers also saw a decline in the level of activism in the

global justice movement. It is somewhat

ironic that the percentage of USSF attendees that were actively involved in the

indigenous movement declined between 2007 and 2010 because the National

Planning Committee for the Detroit event made a successful effort to involve

Native Americans from Michigan in the planning of the Detroit meeting, and the

Michigan indigenes played a very visible role in the Detroit meeting. It would

appear that despite this stress on local involvement the numbers of indigenous

activists declined. The percentage declined from 2.7% in Atlanta to 1.5% in

Detroit. [6]

Both the Slow Food and Environmental movements

seem to have grown significantly. The Slow Food movement, a protest against

mass commoditized consumption that champions locally-grown and organic foods, began

in Italy and has been spreading to the U.S. and elsewhere. The increased salience of global warming and climate justice issues have

encouraged more participation by environmental activists. Some say that anarchists are unlikely to fill

out surveys, but forty-six of our respondents in Detroit indicated that they were

actively involved anarchists. The

percentage of anarchists increased from 1.7% in Atlanta to 2.6% of movement

choices in Detroit. The high visibility of anarchists and horizontalists

in the Occupy movement in 2011 (e.g. Graeber 2013; Gitlin 2012; Milkman, Luce and Lewis 2013) suggests

that the Social Forum process may be drawing from a somewhat different crowd.

But the percentage of anarchists at the USSF increased between 2007 and 2010

(see Table 1, last column).

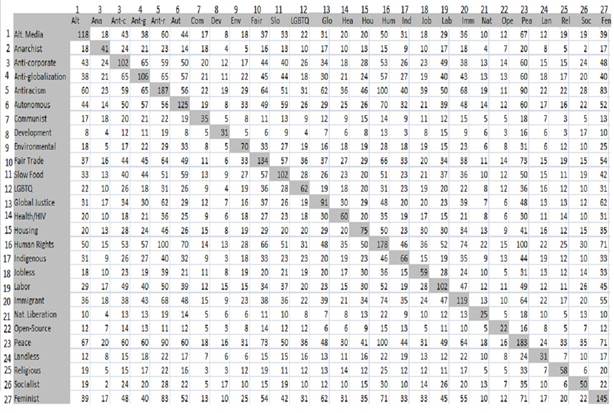

Table 1: Relative Sizes of Movements based on the percentages of movement themes selected as actively involved at the 2007 USSF and the 2010 USSF

We also analyzed the responses to

the question about “strong identification” with movements to compare these with

the “actively involved” question. More than twice as many people indicated “identification”

as opposed to “active involvement”, but the relative percentages were very

similar, and the network results based on the identification matrix was also

found to be very similar to the results for active involvement.

Patterns

of Linkage among the Social Movements

We use formal network analysis to

study the pattern of links among social movements based on attendees’

indications of active involvement in two or more movement themes. Network

analysis is superior to bivariate correlation analysis because it allows the

whole structure of a network to be analyzed, including all the direct and

indirect links as well as the non-links. This makes it possible to identify

cliques or factions among a set of nodes and to examine the centrality or peripherality of network nodes – in this case social

movement themes.

Table 2: Affiliations of 27 Movement Themes, Atlanta 2007

Table 2 contains the selections

of all those attendees in 2007 who selected two or more movement themes. The

diagonal contains the total of all those who selected each movement and these

are the same counts that are in Table 1 for 2007. The other cells are for

movement pairs and contain the number of affiliation selections in which

individuals profess active involvement in both movements. Excluding the

diagonal, the average cell size for Table 2 is 25 and the Standard Deviation of

the distribution of cell sizes is just less than 18.

One striking thing about Table 2 is that there are no zeros. This means

that all of the movement themes are connected with all of the other themes by

having a least a few individuals who profess active involvement in both. The

smallest number of links in Table 2 is between the Socialist and Anarchist

themes (2). Four of the attendees we

surveyed indicated that they were actively involved in both Communist and

Anarchist movements.

We used UCINet to analyze the structures of movement networks.[7] The UCINet QAP routine produces a Pearson’s r correlation coefficient between dichotomized affiliation network matrices. Pearson’s r correlation coefficient between the 2007 and the 2010 matrices was .73.[8] This is a slightly larger positive correlation than was found between the movement theme affiliations between the World Social Forum meeting in Nairobi and the U.S. Social Forum meeting in Atlanta, which was 0.71 (Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro 2009). It is unsurprising that the Atlanta USSF would be more similar to the Detroit USSF than it would be to the Nairobi WSF, but the surprise is that the national and global affiliation matrices are so similar.

Table 3: Affiliations of 27 Movements, Detroit 2010

As with Table 2, there are no zeros in

Table 3, showing that all the movement themes are connected by some co-members.[9]

Excluding the diagonal, the average cell size for Table 3 is 17.7 and the

Standard Deviation is 11.1. That the average number of

overlaps in 2010 was 7.2 smaller than in 2007. In order to use formal network analysis we

must dichotomize this matrix by choosing a cutting point that defines strong

versus weak ties among movement pairs. As

in our earlier research (Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro 2009), we selected a tie

strength cut-off of one-half of a standard deviation above the mean number of

movement interconnections to define a “strong” linkage. All the cells below

that cutting point are assigned a value of zero and those at or above are

assigned a value of one.

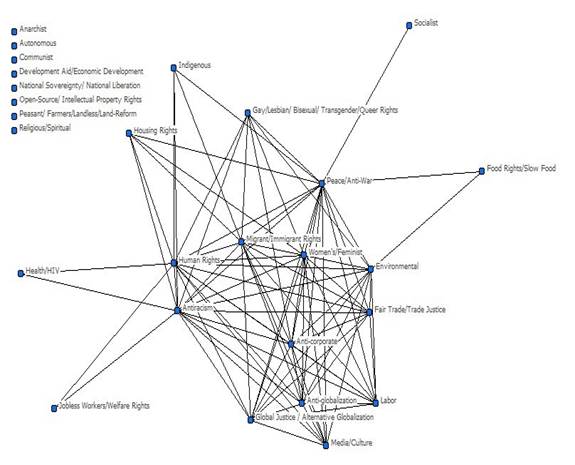

From these scores, network diagrams for

2007 (Figure 1) and 2010 (Figure 2) are produced.[10]

Figure 1: Atlanta USSF 2007 Intermovement Network

Diagram

Figure 2: Detroit USSF 2010 Intermovement Network

Diagram

Comparisons of the

USSF 2007 and the USSF 2010

The purpose of comparing the USSF 2007 intermovement network with that found for the USSF in 2010

is to examine the question of stability and change in the network of social

movements participating in the social forum process, and to look for

differences that might indicate changes or that might stem from the fact that

the meetings were held in different locations and were organized under rather

different circumstances. There are big differences between the cities of

Atlanta and Detroit. And the political and economic situation in the U.S. changed

a lot between 2007 and 2010. The election of President Barack Obama in 2008 and

the advent of a global financial crisis and economic slow-down were major

intervening events.

Regarding stability, the overall

structure of the two movement networks did not change. They are both multicentic structures in which a few central movement

themes link all the rest. Human rights is an inclusive

movement that overlaps with many other movements, and so its centrality in both

national and global movement networks is not surprising. The U.N. Declaration

of Human Rights is a totemic document of global governance and even those who

contest the meaning of these values by championing the rights of communities or

the rights of nature, or by emphasizing the rights of

women or of oppressed groups continue to identify with the overall concept of

human rights.

Both the International Council of

the World Social Forum and the National Planning Committee of the US Social

Forum learned from experiences in Atlanta and tried to make changes to improve

the Detroit meeting of the US Social Forum.

For example, there was a big public protest by a group of indigenous

activists at the end of the Atlanta meeting. The National Planning Committee

for Detroit made a strong effort to contact local indigenous groups from

Michigan early on and to get them to help organize the Detroit meeting and to

play a central role in plenary events and marches. Both meetings were explicitly intended by the

WSF International Committee to be organized by, and intended for, activists

from grass roots movement within the United States. Global and national NGOs

and national unions were allowed to participate, but they did not play a

central role in organizing the meetings. The “internal

Figures 1 and 2 above visually

display the network structures based on overlaps among activists who said they were

actively involved in more than one of the movement themes. The group of

movement themes in the upper left corners of Figures 1 and 2 contain those

movement themes that did not have enough overlaps to be included above the

cut-off points used to calculate network position. In 2007 the Anarchists were

in this relatively isolated group, whereas in 2010 they made it into the main

network because they became more connected with other movement themes. The

Health/HIV and Indigenous movement themes were in the main network in 2007 but

in 2010 they appeared to decline in network centrality and were in the group of

isolates.

Regarding overall network structural

features the results for 2007 and 2010 are quite similar. In both years the

movement themes are connected in a single network that is multicentric.

There are no major subnetworks in which sets of

movements are exclusively connected with one another, but not with other

subsets. What changes from 2007 is the relative centrality of some of the movement themes.

Multiplicative coreness indicates the extent to which a network node possesses a high density of connections with other nodes. The coreness scores presented in Table 4 have been calculated based on the dichotomized interaction matrices produced from Tables 2 and 3 above. Less coreness is characterized as possessing few interconnections. Nodes with high coreness are often capable of greater coordinated action and a greater mobilization of resources, while nodes with less coreness are not. Table 4 shows the coreness scores, the ranks of the movements that are also displayed in Figures1 and 2 above, and Table 4 also shows the amount of change in coreness scores between 2007 and 2010.

|

Rank

in 2007 |

2007 Coreness |

Rank

in 2010 |

2010 Coreness |

Change

in Coreness |

|

|

Human Rights |

1 |

0.313 |

1 |

0.322 |

0.009 |

|

Antiracism |

1 |

0.313 |

2 |

0.319 |

0.006 |

|

Peace/Anti-War |

3 |

0.31 |

8 |

0.278 |

-0.032 |

|

Migrant/Immigrant

Rights |

4 |

0.302 |

5 |

0.285 |

-0.017 |

|

Women's/Feminist |

5 |

0.293 |

7 |

0.282 |

-0.011 |

|

Environmental |

6 |

0.285 |

3 |

0.31 |

0.025 |

|

Anti-corporate |

7 |

0.281 |

5 |

0.285 |

0.004 |

|

Anti-globalization |

8 |

0.264 |

9 |

0.25 |

-0.014 |

|

Global

Justice / Alternative Globalization |

8 |

0.264 |

14 |

0.176 |

-0.088 |

|

Fair

Trade/Trade Justice |

10 |

0.244 |

4 |

0.29 |

0.046 |

|

Labor |

10 |

0.244 |

13 |

0.185 |

-0.059 |

|

Media/Culture |

12 |

0.221 |

11 |

0.222 |

0.001 |

|

Gay/Lesbian/

Bisexual/ Transgender/Queer Rights |

13 |

0.173 |

12 |

0.197 |

0.024 |

|

Housing

Rights |

14 |

0.125 |

18 |

0.026 |

-0.099 |

|

Indigenous |

15 |

0.1 |

20 |

0 |

-0.1 |

|

Jobless

Workers/Welfare Rights |

16 |

0.05 |

16 |

0.092 |

0.042 |

|

Health/HIV |

16 |

0.05 |

20 |

0 |

-0.05 |

|

Food

Rights/Slow Food |

18 |

0.048 |

10 |

0.238 |

0.19 |

|

Socialist |

19 |

0.025 |

19 |

0.015 |

-0.01 |

|

Development

Aid/Economic Development |

20 |

0 |

15 |

0.102 |

0.102 |

|

Anarchist |

20 |

0 |

17 |

0.044 |

0.044 |

|

Autonomous |

20 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Communist |

20 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

National

Sovereignty/ National Liberation |

20 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Open-Source/

Intellectual Property Rights |

20 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Peasant/

Farmers/ Landless/Land Reform |

20 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Religious/Spiritual |

20 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

*Note:

Movements with equal coreness scores were given the

same rank |

|||||

Table 4: Multiplicative Coreness Scores and

Ranks of Movements in the USSF07 and USSF2010 Networks

The movements in Table 4 are sorted from

high to low based on their coreness scores at the

Atlanta meeting in 2007. In 2007 there

was a multicentric network with three movements

sharing the center – human rights, anti-racism and peace (see Figure 1 above).

Other very central movements were immigrant rights, feminists and

environmentalists.

Much of the structure of movement

linkages was retained at the 2010 USSF in Detroit, though there were some

important changes in the positions of particular movement themes. The last

column of Table 4 shows how much the coreness score

of each movement changed from 2007 to 2010. In Detroit human rights and

antiracism, both of which had the highest connectedness scores in Atlanta, increased

their relative connectedness scores, remaining the major hubs linking most other

movement themes. And this increase in connectedness happened despite that both

human rights and anti-racism decreased their sizes relative to other movement

themes (see Table 5 below). The peace movement decreased from 3rd to

8th in the connectedness ranking of movement themes. Immigrant

rights fell from 4th to 5th while environmentalism

increased its level of connectedness from 6th to 3rd and

also increased its relative size.

There were other big changes. Alternative globalization went down from the 8th

to the 14th position; fair trade/trade justice went up from 10th

the 4th position; labor went down from 10th to 13th

position and Slow Food/Food Rights went up from 18th to 10th

position. The second largest change score was that of development aid/economic

development which moved from rank 20 to rank 15. Anarchists moved up from rank 20 in

2007 to rank 17 in 2010. And the jobless

workers/welfare rights movements also increased their centrality, though their

ranking remained the same.

Several movements shifted out toward the

periphery of the movement network. The biggest shift of this kind was that of

the indigenous movement, which went from rank 15 in 2007 to rank 20 in

2010. We already noted above that the

relative size of the indigenous movement appears to have decreased (Table 1). The

second largest negative change in the coreness

measure was that of housing rights, which went from rank 14 in 2007 to rank 18 in

2010 and it also decreased in relative size. And the global justice/alternative

globalization movement (from 8 to 14), labor movement (from 10 to 13), and

health/HIV movement (from 16 to 20) moved further toward the outer edge. While its coreness

score change was moderately negative, the peace/anti-war movement dropped steeply

from its central position at 3rd all the way to 8th in

the coreness ranking. Nine movements did not change their ranking in

the coreness scores and 16 had change scores of less

than .03.

|

Change in Size |

Change in Coreness |

|

|

Human Rights |

-1.37 |

0.009 |

|

Antiracism |

-0.56 |

0.006 |

|

Peace/Anti-War |

-2.09 |

-0.032 |

|

Migrant/Immigrant Rights |

0.24 |

-0.017 |

|

Women's/Feminist |

-0.79 |

-0.011 |

|

Environmental |

1.34 |

0.025 |

|

Anti-corporate |

0.54 |

0.004 |

|

Anti-globalization |

-0.74 |

-0.014 |

|

Global Justice / Alternative Globalization |

-2.08 |

-0.088 |

|

Fair Trade/Trade Justice |

0.03 |

0.046 |

|

Labor |

-0.08 |

-0.059 |

|

Media/Culture |

0.38 |

0.001 |

|

Gay/Lesbian/ Bisexual/ Transgender/Queer Rights |

0.38 |

0.024 |

|

Housing Rights |

-0.41 |

-0.099 |

|

Indigenous |

-1.22 |

-0.1 |

|

Jobless Workers/Welfare Rights |

-0.03 |

0.042 |

|

Health/HIV |

0.02 |

-0.05 |

|

Food Rights/Slow Food |

2.42 |

0.19 |

|

Socialist |

0.45 |

-0.01 |

|

Development Aid/Economic Development |

0.19 |

0.102 |

|

Anarchist |

0.88 |

0.044 |

|

Autonomous |

0.23 |

0 |

|

Communist |

-0.10 |

0 |

|

National Sovereignty/ National Liberation |

0.26 |

0 |

|

Open-Source/ Intellectual Property Rights |

0.60 |

0 |

|

Peasant/ Farmers/Landless/Land-Reform |

0.57 |

0 |

|

Religious/Spiritual |

0.34 |

0 |

Table 5: Changes in Sizes and Coreness Scores between 2007 and 2010; Pearson’s r correlation = .67

Size and coreness

are positively correlated because a larger movement is more likely to have more

ties with other movements. But these two dimensions are not perfectly

correlated (r= .67), and when we look at changes in both the relative size and

the coreness of movements from 2007 to 2010, we

sometimes find movements that decreased in size but increased in coreness and vice

versa (see Table 5). This is possible because a movement can be more linked

with other movements despite that it decreases in size. Movement themes that

got relatively smaller while increasing in network coreness

were human rights, anti-racism and jobless workers/welfare rights (underlined in Table 5). Movement themes

that got larger while decreasing in relative network centrality were immigrant

rights, health/HIV and socialist (bolded in Table 5).

Conclusions

The results

presented in this article are, in some ways, unsurprising. Our earlier studies (that

used the eighteen movement themes that we originally developed for our survey

of the World Social Forum meeting in Porto Alegre,

Brazil in 2005), found substantial stability in the structure of inter-movement

connections. This held even when comparing the results of our survey at the US

Social Forum in Atlanta with two global meetings of the World Social Forum

(Porto Alegre in 2005 and Nairobi in 2007 (Chase-Dunn

and Kaneshiro 2009). This implies that U.S. political

culture and the global political culture represented by the World Social Forum

process at its international meetings are rather similar entities, and this has

important implications for the analysis of transnational social movements as

well as the larger context of global civil society.

In this article we are using a larger

list of 27 movement themes to compare two U.S. Social Forum meetings, and we

find even greater stability in the structure of movement alliances and relative

sizes. Regarding movement sizes, the

Pearson’s r correlation between the percentages in Table 1 above is .88. The QAP Pearson’s r correlation coefficient

between the 2007 and the 2010 matrices in Tables 2 and 3 is .73.

There were, however, some important

changes. While the overall network structure retained a multicentric

form with four or five movements occupying the center of the network and being

similar to one another in terms of relative coreness,

some of these central movements changed positions with other movements that

were less central in 2007. Environmentalists

were centrally located in all of our earlier results, but they were not as

important as they became in the Detroit meeting of the U.S. Social Forum. They

displaced peace/anti-war at the very center of the movement network and nudged

the migrant/immigrant rights and women’s/feminist movements slightly out from

the center. While food rights/slow food increased in size and development

aid/economic development decreased in size, both increased their network

centrality. The peace movement dropped from 3rd to 8th in

connectedness rank, while the indigenous, housing rights, global justice, and

labor movements lost both centrality in the movement network and relative size.

Some of these changes in size and

centrality may have had to do with the changing salience of movement

topics. Environmentalism is on the rise,

especially the climate justice movement. The decreased size and coreness of the peace movement may have been related to the

promises of the Obama administration to withdraw U.S. troops from Iraq and

Afghanistan. As mentioned above, the slow food/food justice movement has been

spreading from its point of origin in Italy and this may account for its

increase in size and coreness between 2007 and 2010. It

is plausible that the declining size and coreness of

the global justice movement between 2007 and 2010 was a consequence of how

economic stress, even when global in scope and causation, focusses activists on

more local problems.

The apparent decrease in network

centrality and relative size of the indigenous movement theme is an ironic

outcome which occurred despite the great efforts of the USSF organizers to

showcase indigenous issues in Detroit. We surveyed 66 activists in Atlanta who

identified themselves as actively involved in indigenous issues, but only 26 in

Detroit. And the relative centrality of these in the connectedness matrix also

declined. One possibility is that indigenous activists were so busy at the Detroit

meeting that they did not have time to respond to our survey. The other

possibility is that attendance of indigenous activists actually declined as a

response to the issues raised by the unhappy indigenous activists in Atlanta,

who took control of the closing plenary session to protest perceived

indignities. Because we do not know whether or not our sample of attendees was

a random sample we cannot be sure. The solution here would be to have access to

registration data for these meetings with enough detail to be able to check

survey results against the registration data.

Perhaps the most important result of our

studies of intermovement networks is the finding of a

rather stable multicentric structure of relations

among movements at both the global and the national levels. The geographical locations

of meetings and world historical events obviously have impacts on this

structure, as we found in comparing Porto Alegre with

Nairobi, but the basic underlying structure is being reproduced. The collective

action problem is how to mobilize coordinated organizational instruments that

can help humanity to deal with the huge challenges that it has created for

itself in the 21st century. The Social Forum process remains an

important venue in that effort.

References

Allison, Juliann, Ian Breckenridge-Jackson, Katja

M. Guenther, Ali Lairy, Elizabeth

Schwarz, Ellen Reese, Miryam E. Ruvalcaba, and Michael

Walker 2011 “Is

the

Economic Crisis a

Crisis for Social Justice Activism?” Policy Matters, Volume

5,

Issue 1 http://www.policymatters.ucr.edu/

Amin, Samir

1997 Capitalism in an Age of Globalization.

__________ 2006. “Towards the fifth international?” Pp.

121-144 in Katarina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.)

Democratic Politics Globally. Network Institute for Global Democratization

(NIGD Working Paper 1/2006),

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K.

Hopkins, and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic Movements.

Borgatti, S. P. and Everett, M.

G. and Freeman,

L. C. 2002 UCINET 6 For Windows: Software

for Social Network Analysis

http://www.analytictech.com/

Boswell,

Terry and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2000. The Spiral of Capitalism and Socialism: Toward

Global Democracy.

CO: Lynne Reinner.

Byrd, Scott C. 2005. “The

Chase-Dunn, C.

and Ellen Reese 2007 “The World Social Forum: a global party in

the

making?” Pp. 53-92 in Katrina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko

Ulvila (eds.) Global

Political

Parties,

London: Zed Press.

Chase-Dunn, C. and R.E. Niemeyer 2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” Pp.

35-57 in

Mathias

Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.)

Transnational Political Spaces. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/

Chase-Dunn, C.

and Anthony Roberts 2012 “The structural crisis of global capitalism and

the prospects for world revolution in the 21st

century” International Review of Modern

Sociology 38,2: 259-286 (Autumn)

(Special Issue on The Global Capitalist Crisis and

its Aftermath edited by Berch Berberoglu)

Coyne, Gary, Juliann Allison, Ellen Reese, Katja Guenther, Ian Breckenridge-Jackson,

Edwin

Elias, Ali Lairy, James Love, Anthony Roberts,

Natasha Rodojcic, Miryam

Ruvalcaba, Elizabeth Schwarz, and Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2010 “2010 U.S. Social Forum

Survey of Attendees:

Preliminary Report “Irows Working Paper # 64 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows64/irows64.htm

della Porta,

Donatella. 2005a. “Multiple Belongings,

Tolerant Identities, and the Construction of ‘Another Politics’:

Between the European Social Forum and

the Local Social Fora,” Pp. 175-202 in Transnational

Protest and Global Activism,

edited by Donatella della

Porta and Sidney Tarrow. Lanham: Rowman

& Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Fisher, William F. and

Thomas Ponniah (eds.).

2003.

Another World is

Possible: Popular Alternatives to Globalization at the World Social Forum.

Gitlin, Todd 2012 Occupy Nation. New York: HarperCollins

Graeber, David 2013 The Democracy Project: A History, A Crisis, A Movement. New York:

Spiegel and Grau

(Random House).

Hanneman, Robert and Mark Riddle 2005. Introduction to Social

Network Methods.

http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/

|

Krinsky, John and Ellen

Reese. 2006.

“Forging and Sustaining Labor-Community Coalitions:

The Workfare Justice

Movement in Three Cities.” Sociological

Forum 21(4): 623-658.

Mason,

Paul 2013 Why Its Still Kicking Off Everywhere: the New Global

Revolution. London: Verso

Martin, William G. et al, Making Waves: Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005. 2008 Boulder,

CO: Paradigm

Meyer.David S. and Catherine Corrigall-Brown

2005 “Coalitions and political context: U.S.

movements

against wars in Iraq” Mobilization 10:

327-344.

Milkman, Ruth,

Stephanie Luce and Penny Lewis 2013 “Changing the subject: a bottom-up

account of

Occupy Wall Street in New York City” CUNY: The Murphy Institute

http://sps.cuny.edu/filestore/1/5/7/1_a05051d2117901d/1571_92f562221b8041e.pdf

Obach, Brian K. 2004

Labor and the Environmental Movement: The Quest for Common Ground.

Petit,

Christine. 2004.

“Social Movement Networks in Internet Discourse” Presented at the

annual meetings of the American Sociological Association,

San Francisco. IROWS Working

Paper #25.https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows25/irows25.htm

Reese,

Ellen, Christine Petit, and David S. Meyer. 2008 “Sudden Mobilization: Movement

Crossovers,

Threats,

and the Surprising Rise of the U.S. Anti-War Movement.” Social

Movement Coalitions, edited by

Nella Van Dyke and

Holly McCammon

Reese, Ellen, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Kadambari

Anantram, Gary Coyne, Matheu

Kaneshiro, Ashley N. Koda,

Roy Kwon and Preeta Saxena 2008 “Research

Note: Surveys of World Social Forum participants show influence

of place and base in the

global public sphere” Mobilization: An International Journal. 13,4:431-445.

Reitan, Ruth 2007 Global

Activism.

Rose,

Fred 2000 Coalitions Across

the Class Divide: Lessons from the Labor, Peace, and Environmental Movements.

NY: Cornell University Press.

Schönleitner, Günter 2003 "World Social Forum:

Making Another World Possible?" Pp. 127-149 in John Clark (ed.):

Globalizing Civic

Engagement: Civil Society and Transnational Action.

Smith, Jackie, Marina Karides, et al.

2014 The World Social Forum and the

Challenges of Global Democracy. Boulder, CO:

Paradigm Publishers. Revised edition.

Smith, Jackie and Dawn Weist 2012

Social Movements in the World-System. New York: Russell-Sage

Snow, David A

and Sarah A. Soule 2009 A Primer on Social Movements New York:

Norton.

Starr, Amory.

2000. Naming the Enemy: Anti-corporate Movements Confront Globalization.

Van

Dyke, Nella 2003“Crossing

movement boundaries: Factors that facilitate coalition protest by American

college

students,1930-1990.” Social Problems 50(2):226–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/sp.2003.50.2.226

Van Dyke, Nella and Holly J. McCammon

(eds.) Strategic Alliances: Coalition

Building and Social Movements. Minneapolis,

MN: University of Minnesota

Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel 2004 World-Systems Analysis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Watts, Duncan

2003. Six Degrees: The Science of a

Connected Age.

Zald, Mayer N. and John D. McCarthy 1987 Social Movements in and Organizational

Society. New

Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books