Maritime

Capitalism in

Seventeenth-Century

China:

The

Rise and Fall of Koxinga Revisited

Ho-fung Hung

Department of Sociology,

The Johns Hopkins

University

541 Mergenthaler Hall,

3400 N. Charles

Street,

Baltimore, MD

21218

hofung@jhu.edu

Working paper, October 2000

IROWS Working Paper # 72

available at irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows72/irows72.htm

University of

California-Riverside

In

seventeenth-century China,

Zheng Chenggong, known to Europeans as Koxinga, and his family emerged as a

formidable commercial and military power in maritime East

Asia that was tamed by neither the Ming/Qing governments nor the

European colonizers. In this paper, I will reject the conventional interpretation

that presents the Zhengs’ maritime power as no more than an ad hoc, individual

venture the final failure of which was inevitable given the strength and

hostility of the Chinese Empire. By synthesizing original sources and recent findings

from the secondary literature, I will revisit the rise and fall of the Zhengs

by arguing that: (1) Over three generations, the Zheng familial enterprise had

evolved from a decentralized trade network into a vertically integrated,

bureaucratically managed business organization with an economic size comparable

to the VOC and the Qing Empire at large; (2) By the 1660s, the Zheng regime had

become an independent Imperial-merchant state anchored at Taiwan, while the

Qing government had tilted toward giving up its attempt to take Taiwan; (3) The

final collapse of the Zheng regime in 1683 was contingent and far from

inevitable. It would have sustained had it not been exhausted by its

unnecessary and miscalculated military adventure to fight back on mainland China in the

1670s. This new look at the rise and fall of the will deepen our understanding

of the “interactive emergence of European domination” in Asia.

In 1675, when the maritime power of the United

Provinces was at its zenith in Europe, Federick Coyett, a former Dutch governor

of colonial Taiwan, observed

the emergence of a similar power in East Asia

during the dynastic transition from Ming to Qing. The Zheng family, under the

leadership of Zheng Chenggong, who was the son of an armed trader Zheng Zhilong

and was known to the Europeans as Koxinga, expelled the Dutch from Taiwan in

1662 and turned the island into a base for expanding its commercial empire and

resisting the nascent Qing regime. Coyett draws a parallel between the Zheng –

Qing conflict and Dutch – Spain

conflict at the two ends of Eurasia. The

relation between the Zhengs and the Qing was seen as a conflict between a maritime

and a continental power:

When, in the previous century, our beloved Fatherland had

fallen into such extremity that it seemed no longer possible to resist the

power of the Spaniards, and when the Church had to all appearance become their

slaves, that highly celebrated Prince, the greatest politician of the time,

whose memory is so dear to the Dutch nation, and on whose martydom the first

foundations of our precious freedom were laid, forced the desperate Council to

surrender their country to the mercy of the waters by breaking the dykes and

dams; thus causing it to sink away as if in a precipice, and compelling the

people, with their wives, children, and moveable property, to take refuge in

their ships. They would then have to depend absolutely on God’s mercy, and go

to sea in search of other countries, where they could found a new republic.. In like manner Koxinga, after many long

years of war with the Tartars [Manchus], who pursued him very vigorously, was

brought to a state of great extremity; so much so that he has forced to hide

his wife and children and all their moveable goods in junks, and to remove from

one island to another.

When, … all [Qing forces] joined together against him, success

forsook him for a time, and he was compelled to seek his fortune at sea. Here

his influence soon increased as much as power on land decreased; especially

because the Tartars had little experience of sea life. (Coyett 1903:384; 412)

The Dutch observation was confirmed by the Spaniards.

After ousting the Dutch from Taiwan

in 1662, Zheng Chenggong sent an Italian Dominican priest, Fray Victorio

Riccio, to Manila

as his representative and demanded an annual tribute from the Spanish Colony.

He threatened to conquer the Philippines

with the example of Taiwan.

Receiving no response, Zheng decided to organize an expedition to Manila. The city

immediately fell into chaos and panics. The garrisons from all over the Colony

were withdrawn and the troops were concentrated to defend the fort of Manila. The Spanish

government hysterically witch-hunted Zheng’s collaborators among the Chinese

residents and executed a large number of suspects. (Ts’ao 1972: 14; Anonymous

1906: 218-9; Foccardi 1986: 96-7)

Having heard of the news that Zheng

died in 1663 without materializing his plan, the Colony was greatly relieved.

An anonymous Jesuits wrote in fear and aspiration that:

In short, this people [i.e., the Chinese] is the most ingenious

in the world; and when they see any contrivance in practice they employ it with

more facility than do the Europeans. Accordingly, they are not now inferior in

the military art, and in their method of warfare they excel the entire world.

…Europeans who have seen it [Zheng’s army] are astonished. …From this may be

inferred the joy that was felt throughout the city and the so special kindness

of God in putting an end to this tyrant [Zheng Chenggong] in the prime of his

life… (Anonymous 1906 [1663]: 257-8)

After the Zhengs consolidated their regime in Taiwan, they reconsidered invading the Philippines in

1673. The new Governor of Manila, who began his office in 1669, reacted by

sending an ambassador to Taiwan

to express his friendly overtures. Zheng’s plan was dropped at last because of

his renewed engagement in Mainland China. Thereafter, Manila

benefited from its good relationship with Taiwan,

and the city was visited every year by five to six Taiwan junks which flooded the

Colony with high quality Chinese silk (Ts’ao 1972: 14; Wills 1974: 27; TWWJ

28:416 ).

The English would definitely agree

with their Dutch and Spanish rivals. In the seventeenth century, the English

were newcomers in East Asia and could not find

a niche in the region under Dutch hostility and Qing’s reluctance to trade.

They turned to Zheng Chenggong’s successor Zheng Jing (whom they called “the

King of Tywan”) and tried to plug themselves into Zheng’s commercial networks.

In 1670, an agent of the East Indian Company was sent from Bantam to Taiwan with

valuable gifts.

A trade agreement was signed between the Zheng

regime and the EIC. The English was granted the right to establish a factory in

Taiwan

and purchase silk, Japanese copper, sugar and deerskin from the Zhengs. In

return, they had to supply Taiwan

with 200 bucks of gunpowder, 200 matchlock guns and 100 piculs of iron every year. Besides, the Company had to keep two

expert gunners in Taiwan

“for the King’s service,” (to train Zheng’s artillery) and a blacksmith for

“making King’s guns.” Although the English kept complaining that they were

charged with unreasonably high prices for the goods, they had no choice other

than to comply. (Ts’ao 1972: 14; Wong 1984: 155-156; Shepherd 1993: 100; Morse

1926: 44-8; Lai 1982: 278-82; Paske-Smith 1930: 82-122)

In addition, the Zheng regime in Taiwan was an

active contender against the Qing Empire within the Sinocentric tributary

order. It received tributes from certain Southeast Asian states (such as Siam and Annam). In 1671, and once again in

1673, Ryukyu tributary vessels on their way to China were seized by Zhengs’

warships. It was not only a humiliation to the Qing government, but also

created a diplomatic squabble between Taiwan

and Japan – which was

another contender against the Sinocentric order in East

Asia at that time (Zhang 1966: 63, 65, 79; Wong 1983: 154; see

Hamashita 1988, 1994 and Kawakatsu 1994

for Japan’s place in the Sinocentric order).

In most of the seventeenth century, the Zheng Empire

was an insuperable power enjoying naval and commercial supremacy in maritime East Asia. It was tamed by neither the Qing Empire nor

the European colonizers. If the Zheng He Expedition between 1405 and 1433 is

comparable to later Iberian “maritime Imperialism” in terms of the geographical

reach of the Expedition (see Finlay 1992), the power of the Zheng family is

definitely comparable to the maritime capitalism of the contemporaneous

European Companies in terms of the Zhengs’ mutually reinforcing pursuit of

power and profits. Apart from the similarities, how was the Zheng Empire

different from its European counterpart? How did it interact with the

continental, Imperial state of China?

How did it collapse finally? What is its significance in our understanding of

the history of China and Asia? These are the questions this paper seeks to answer.

MARITIME

POWERS, CONTINENTAL STATE, AND EUROPEAN COMPANIES IN EARLY MODERN ASIA

Under a burgeoning literature on

maritime Asia (e.g. Ptak and Rothermund eds 1991; Chaudhuri 1990; Pearson 1988;

Das Gupta and Pearson, eds. 1987; Pearson 1987; Subrahmanyam 1990a, b&c;

Reid 1988; Blusse 1988), the Eurocentric and teleological view that Asia was no

more than a passive victim of the mighty Companies from Europe and that Asia

was predestined to be peripherized by the expanding European world-system has

been under attack for the last two decades.

It is shown that in their course of expansion into Asia, European traders always ran into indigenous

merchants as tough rivals. The latter were not inferior, or even superior, in

many aspects to the Europeans. The integration of state-building and

profit-making activities, as an essential characteristic of the European

Companies ( Steensgaard 1974; Tracy ed. 1990; Tracy ed. 1991; Israel 1989;

Blusse and Gaastra eds. 1981; Lane 1979; cf. Tilly Arrighi Wallerstein), was

never unique to them. A widely noticed example counterpoising the uniqueness of

the European model was the maritime-oriented state of Oman. Over the

seventeenth century, the Omanis’ sphere of prevalence extended from the Persian

Gulf to the east coast of Africa and west coast of India. The Portuguese, Dutch and

the English could hardly break the trade monopoly of the Omanis, and were kept

at bay by them (Bathurst 1972; Boxer and de Azevedo 1960; Alpers 1975;

Subrahmanyam 1995: 770-2).

Evidences also point to the fact that Asian empires

were not invariably hostile to maritime communities. By studying the Ottomans’,

Safavids’ and Mughals’ relation with various commercial communities,

Subrahmanyam (1995) finds that traders could always benefit from their active

alliance with the continental state, and “under the carapace of the Islamic

Empires of the early modern epoch, merchant groups could not only expand

geographically but gradually redefine their place and engage in new ways with

political power” (774). These refreshing studies are in tandem with the

re-conceptualization of the nature of European expansion into Asia

as an “interactive emergence of European domination” (Wills 1993), emphasizing

the active role played by Asian traders in the process. More case studies are in need to substantiate

this claim and to illuminate any intra-Asian variation.

On the part of China, Wills pioneers to illustrate

that there existed a tradition of maritime commerce, a tradition of positive

interaction between profits and powers, in late Imperial China. He notices that

the Dutch VOC faced a number of difficulties in establishing themselves in East Asia, with the competition from the Zheng family as

a big obstacle (Wills 1974). Later, Wills (1979) moves further to locate the

Zhengs, and the tradition of maritime China

in general, within the late Imperial history of China:

[W]e see them [maritime

traders, ports, etc.] as “peripheral” to the main patterns of Chinese

history... [T]heir influence was limited in periods of political instability

and they were more or less repressed, exploited, and distorted by the dominant

core system in times of stability.

[T]he

case of Cheng Ch’eng-kung [Zheng Chenggong] .. suggests that the maritime

interaction of profit and power fully realized its political potential only in

combination with strict military discipline and strong committment to a

political cause. In the events discussed here, this happened only in a narrow

focus on an extraordinary individual, not in an often-repeated pattern of

personal power and legitimation, still less in the involvement of a whole community

in the pursuit of maritime profit and power. Cheng Ch’eng-kung was neither Shih

K’o-fa [Shi Kefa, a renowed Ming hero who selflessly resisted the Qing] nor a

K’ang-hsi [Kangxi, the Qing Emperor from 1661 to 1722]; Amoy [Xiamen,

a port that served as Zheng’s base before he retreated to Taiwan] was not a Venice

or an Amsterdam.

(204-6; 234)

In

sum, Wills contentions are threefold: (1) the naval-cum-commercial power of the

Zhengs was nothing more than a personal endeavor, and the individual adventures

of maritime traders were more ad hoc than accumulative; (2) the Imperial power

was antagonistic to the maritime power, and would crush it whenever it could;

(3) the final collapse of the Zhengs were inevitable. In addition, Wills hints

later that the vulnerability and political subjugation of maritime China are exceptional to the overall pattern of

maritime Asia, in contrast to the port-states tradition in Southeast Asia and Oman for

example:

The two quotations above illustrate

the most comprehensive framework to date that puts the Zheng family in the

context of Chinese late Imperial history and the history of maritime Asia. A number of revealing studies on the subject

appeared after Wills’ path-breaking works in the 1970s to enrich our knowledge

on the Zhengs.

Each of the research focuses on certain specific aspects of the Zhengs venture.

Most of them follow or share Wills’ grand interpretation that the rise and fall

of the Zhengs is a fortuitous episode in Chinese history.

In this paper, I try to unravel this

“China exceptionism” in

maritime Asia as suggested by Will’s

interpretation of the Zhengs family. Through a synthesize of secondary sources

and original research,

I will reinterpret the rise and fall of the Zheng family and argue that: (1)

The enterprise of the Zheng family was far more than a personal endeavor. Over

three generations (Zheng Zhilong, Zheng Chenggong and Zheng Jing), it had

evolved from a loose familial trade networks to a vertically integrated,

bureaucratically managed trade organization; (2) The political ambitions of the

Zhengs and Qing’s policy towards them, as well as the strategies they employed

to deal with each other were in flux. By 1670, a stable maritime order had

emerged over the Taiwan Strait in which the Zheng regime became a virtually

independent Imperial-merchant state exercising its dominance over maritime East

Asia, while the Qing government no longer bothered incorporating Taiwan into

the Empire; (3) The final collapse of the Zhengs’ maritime Empire in 1683 was

largely a result of contingencies. Had not the Taiwan

regime collapsed by itself because of its over-ambitious engagement in the

mainland, the Qing government would not have been able to incorporate Taiwan into the

Qing Empire in the end.

In what follow, I will first outline the rise of

Zheng Zhilong that laid the foundation of Zheng Chenggong’s maritime empire.

Then I will decipher the structure of economic and political organizations of

the Zheng regime. At last, I will analyze the concatenation of events that led

to the collapse of the Zheng regime in 1683.

THE

RISE OF THE ZHENG FAMILY

Ming China entered the phase of dynastic decline in

the middle of the sixteenth century. Corruption of the Imperial bureaucracy

grew and budget deficit enlarged. Meanwhile, the balance of power in the North

was disrupted by the expansion of the Jurchens. In the Southeast coast, illegal

trade conducted by armed Chinese and Japanese traders – known collectively as wokou or “Japanese pirates” to the

Chinese government – flourished when trade with China

was encouraged by the coastal warlords in Japan. (Lin 1987: 85-111; He 1996:

45-7; Tong 1991: 115-29; Wakeman 1985: Ch.1; Huang 1969: 105-23; Wills 1979:

210-1; So 1975) The intrusion of the Portuguese in the region escalated the

level of violence among the Chinese and Japanese traders when the Portuguese

traded their firearms for silk from the Chinese. Nonetheless, because of the

over-extension of Portuguese maritime power, the Portuguese were weak in East Asia and never displaced the Chinese and Japanese

traders as the leading forces in East Asian trade. Though the Ming government

lifted its sea ban in 1567, trade with Japan was still forbidden. Armed smuggling

continued (He 1994: 49-52; Boxer 1969: 56-7; Souza 1986: 130-1).

The militarization of maritime trade led to the rise

of highly organized and militant Chinese merchant groups. Their power inflated

drastically after the retreat of the Japanese merchants in the 1630s under the

Tokugawa Seclusion Policy that forbade its subjects to travel abroad (for

discussion of the Seclusion Policy, see Howe 1996: 12 and Lee 1999). Zheng

Zhilong was one of these armed Chinese traders. He was born in 1604 in a merchant

family in Fujian.

In 1621, he became a follower of Li Dan, one of the most influential Chinese

traders in the Japan and Manila trade routes. Meanwhile, he was employed by the Dutch VOC

as an interpreter in 1624. (Lin 1987:

112-7; Yang 1982: 294; Chen 1984: 151; Wong 1984: 120-3; Blusse 1981: 94) In

1625, Li Dan died. Zheng immediately took over all of his property and trade

networks under the military support of the Dutch. (Foccardi 1986: 6-8; Blusse

1981:98; Wills 1979: 217-8; Lin 1987: 114-5)

After a few years, he was the strongest Chinese on

the sea. He monopolized both the connections with the Dutch, who had controlled

Taiwan and turned it into

their key trading post in East Asia since

1624, and the supply of Chinese products, and became more independent. He was

upgraded from an employee to an ally of the Dutch in 1628, when the two parties

signed a three years trade agreement. Zheng was to supply Dutch Taiwan annually

with 1,400 dan of raw silk, and a

certain amount of sugar and textiles, whence the VOC promised him an annual

supply of 1,000 dan of pepper. In

1630, Zheng and the Taiwan

Governor signed a treaty on mutual military protection. He was then 26 years

old. (Chen 1984: 188; Yang 1982: 309)

Zheng Zhilong’s dominance in coastal China alarmed

the Ming government. In 1630, the secretary of the Ming military ministry

reported to the Emperor that “all Zhilong’s ships are barbarian [i.e. Dutch]

ships, all his canons are barbarian canons, and he now possesses up to a

thousand warships.” (MSL Chongzhengchangpian 41: 3.12 yiyi) When the inland turbulence picked

up, the Ming government gave up subjugating Zheng by force, and instead tried

to incorporate him into Ming’s power structure. In 1628, an alliance was formed

between the Ming government and Zheng. Zheng was entitled Patrolling Admiral (youji jiangjun), bearing the responsibility of eliminating all

other “pirate groups” under the logistic support of the Imperial navy. By 1636,

all competing merchant groups had been smashed or incorporated into Zheng’s

network. All foreign trade activities of China were put under his unified

leadership (Wills 1979: 218-9; Struve 1988: 667; Chen 1984: 156-7; Wong 1983:

127-9; Lin 1987: 117-23; MSL Chongzhengchangpian

11: 1.9 gengwu, 41: 3.12 yiyi; Foccardi 1986: 16).

Soon the Dutch realized that Zheng was their

toughest competitors in the East Asian market, and they decided to do away with

him once and for all. In July 1633, a Dutch assault of Zheng’s naval base at Xiamen triggered a war between the Zhengs and the Dutch

along the southeast coast of China.

It ended up in the humiliating defeat of the Dutch who retreated hastily back

to Taiwan in October and

never set their foot on the China

coast again (Chen 1984: 158; Blusse 1981: 102-3; Wills 1998: 370-1).

In 1641, a peace and trade treaty was signed between

Zheng and the VOC. The Dutch would pay an annual tribute of 30,000 écus to Zheng to exchange for stable supply

of Chinese commodities. Peace was restored under a new maritime order. The

Dutch could only find his place in this order as Zheng’s humble partner, while

the Ming government had actually transferred the governance of the coastal

regions to Zheng.

At the peak

of Zheng’s career, the Ming government

in Beijing collapsed in 1644, followed by the

fall of the Southern Ming court in Nanjing

in 1645. A number of Ming courts were set up by different Ming princes at

various places in southern China.

Lungwu court was founded in Fujian

and Zheng became its protector. However, when the Manchu troops were approaching

the border of Fujian in 1646, Zheng withdrew

his force from Fuzhou

and let the Qing forces capture this provincial capital without any resistance.

Zheng’s calculation that Manchus would co-opt him like the Ming court did

turned out to be a mistake. He was arrested and sent to Beijing, where he was held hostage till he

was executed in 1661. (Struve 1988: 665-73, 675-6; HSJWL: Yongli 1.1; HJJY: Lungwu

2.8; MHJY: Lungwu 2.9, MHJL Lungwu 2.9; Wills 1998: 224; Chen 1984:

160-3; Lin 1987: 123-4)

The Zheng family was caught in a familial feud after

Zhilong was arrested. It was not until 1650 was it reunified under the strong

leadership of Zhilong’s eldest son, Zheng Chenggong,who forcibly eliminated his uncles’ power.

The Zheng family recouped rapidly from the chaos of leadership transition and

re-attained the status of supremacy in East Asian trade. Zheng Chenggong

significantly upgraded the family’s commercial capacity by turning his father’s

trade networks into a vertically integrated and bureaucratically administered

organization.

Compared to his father, Zheng Chenggong was much

more purposeful as well as effective in mobilizing the trade revenue to

establish an intact politico-military apparatus that turned his family venture

into a maritime empire. The Zheng regime continued to be the most prominent

player in the East Asian water even after Zheng Chenggong retreated to Taiwan in 1662 following his failure in taking Nanjing, the traditional

imperial center in the South. The Zheng regime was further consolidated and

turned into a de facto independent

kingdom on Taiwan

– a well defended island insulated from the attack of Qing’s feeble navy –

under the leadership of Zheng Chenggong’s successor Zheng Jing.

THE

MAKING OF A VERTICALLY INTEGRATED COMMERCIAL ORGANIZATION

The Mainland Period

From the 1620s to the 1640s, Zheng Zhilong’s

supremacy in maritime China

allowed him to accumulate an enormous amount of wealth for his family. It is

reflected by the fact that during a Qing attack of Xiamen in 1651, 900,000 taels of gold, equivalent to about 10

million taels of silver, were seized

(CZSL: Yongli 5.4.1, 7.8).

It was all the liquid capital he had commanded. This amount was extraordinarily

large, given that the total cash revenue of the Qing government in the same

year was 21 million taels of silver,

(Wakeman 1985: 1070) and the surplus accumulated by the VOC in Batavia between 1613 and 1654 was only 15.3

million guilders, or 4.4 million taels of

silver.

(Glamann 1958: 248) Zhilong turned Fujian

into his own paradise. He bought great estates there and built his extravagant palace

near Xiamen. He

was considered by the coastal population as the “King of Southern China”

(Foccardi 1986: 18).

However, Zheng Zhilong’s enterprise was no more than

a decentralized trade network. He never managed to consolidate his grip of the

whole network that was built upon incorporating rival merchant groups. Instead,

he shared the control of the business with his brothers and other members of

the Zheng family. It is why the Manchus did not co-opt Zheng Zhilong after he

surrendered (as they usually did to other surrendered Ming generals and

officials), but used him to threaten and blackmail the rest of the Zheng

family. The Manchus realized that Zheng did not control his family effectively

and was incapable of delivering its whole power structure to the Qing (Wills

1979:222).

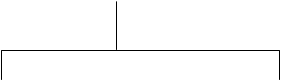

After guaranteeing his leadership in the family,

Zheng Chenggong set out to rebuild his father’s enterprise. He upgraded his

family’s commercial capacity by converting the trade network into a centrally

commanded structure. Five companies (wushang)

and two fleets were set up to conduct inland and overseas trade. Each of the

five companies was divided into two branches (hang), one conducing inland trade and the other conducting maritime

trade. One was located in the Lower Yangzi region under the coordination of

Zheng’s secret regional headquarter at Hangzhou,

and was responsible for purchasing indigenous products. The goods were then

shipped to the other branch located at Xiamen.

The latter then distributed the cargoes to either one of the two fleets – the Eastearn Sea

fleet (dongyangchuan) or the Westesrn Sea fleet (xiyangchuan). They in turn sold the goods at the Japanese and

Southeast Asian markets respectively. Each company and fleet received its

capital from the treasury. All incomes were delivered back to the treasury

after the goods were sold. All of the treasury, five companies and two fleets

were centrally administered by the minister of finances of the Zheng regime,

who was Zheng Chenggong’s brother Zheng Tai. The treasury’s account records

were reported to, then dated and stamped by Chenggong regularly. The operation

of the whole structure was kept in check by an independent monitoring officer (lucha).

Besides, the companies and treasury lent money to

independent merchants in lack of capital. The activities of these merchants

were coordinated by the minister of finance. The inland five companies also

served as intelligence agencies that collected information about Manchus’

activities. (Nan 1982; Yang 1992: 258) The structure and operation of the whole

organization are illustrated below.

(Figure

1 about here)

Through

this organization, Zheng’s seafaring enterprise was integrated with the Lower Yangzi market and production zone. A centralized

and vertically integrated commercial organization was instituted as the revenue

generating apparatus of the Zheng regime.

Major items of trade controlled by the Zheng

enterprise included silk textiles, ceramics and gold from China, copper, silver and sulphur from Japan, and spices from Southeast

Asia. More than 80 percent of the Chinese junks trading in Nagasaki and Southeast Asia

belonged to the Zhengs. (Yang 1984b: 224-6; see also Han 1982: 148-55) All other vessels sailing in Zhengs’ sphere

of influence (which meant nearly the whole maritime East

Asia) had to fly his flag, and pay him a toll of 3,000 taels of gold. In return, the Zhengs

protected them from any danger at sea, which was mainly the attack of the

Dutch.

The annual interest rate of the loans offered to the independent merchants was

around 100 percent. The Zhengs also provided shipping services to the merchants

who did not bother travelling abroad to sell their goods (Lin 1984: 199; Nan

1982: 218-20; Li 1982: 226-7; Han 1982; Zhang 1982).

It is estimated that in the 1650s, the average

annual profit of Zheng’s direct involvement in trade was 2.4 million taels, equivalent to about 8.5 million

guilders. (Yang 1984b) It was nearly five times bigger than the VOC’s annual

profit in East Asia, slightly larger than the Company’s profit in the whole Asia, and more than one-tenth of the annual cash revenue

of the Qing government around the same period.

During the Zheng Chenggong era, the Dutch continued

to be a humble player in the East Asian trade as they continued to rely on

Zheng for supply of Chinese goods. Zheng Chenggong was regarded by the Governor

General of Batavia

as “the man who can spit much in our face in Eastern seas” (Foccardi 1986: 59).

To guarantee its access to Chinese products, the VOC paid an annual tribute of

5,000 taels of silver, 100,000

arrows, and 1,000 dan of sulphur to Xiamen (CZSL: Yongli 11.6; Han 1984: 212-3; Yang 1992:

265; Coyett 1903: 389; HJJY Yongli

11.6; MHJY Yongli 11.6).

The Taiwan Period

In order to weaken Zheng’s regime by cutting off the

supply from the mainland, the Qing government implemented the scotch-earthed evacuation

policy in 1660. All residents in the Xiamen

area had to be moved 10 miles away from the seashore. It was then extended to

the whole Fujian province in 1661, to Guangdong in 1662 and part of Zhejiang in 1663. All coastal villages and

towns were burnt down. Castles were built along the evacuation line. (QSLZZZLZ:

44; HJJY: Yongli 15.10; MHJY: Yongli 15.10; Foccardi 1986: 90; Ts’ao

1972: 12; Shepherd 1993: 96)

The evacuation policy of Qing caused great

difficulty to Taiwan

initially (MHJY: Yongli 17.1). The

effect of the measure faded, nevertheless, when illicit trade across the Strait

resumed. The “five companies” system survived and continued its operation

through the 1660s and 1670s.

Over the period, Taiwan

was never short of silk supply from the mainland. (Nan 1982: 204-8; Ju 1986:

141-6; Lin 1984: 198-9; Li 1982: 228-9; Shepherd 1993: 96) In addition, the

deerskin resources and sugar cane plantation in Taiwan generated additional profits

for the Zhengs (Ju 1986:147-9; Wong 1983: 154-5; Shepherd 1993: 100).

Ironically, the evacuation policy backfired as it let the Zhengs further

monopolize the supply of Chinese products in the international market. It is

observed by a Qing officer that,

After our court imposed a strict ban on sea trade,

not a single junk is able to go into the sea. However, some merchants, who

monopolize the supply of products, bribe the officials and soldiers guarding

the coast, and trade with the Zheng family secretly. Consequently, the profits

on the sea are manipulated solely by the Zhengs, and their wealth and supplies

become more and more abundant. (quoted in Han 1982: 143; see also Ng 1983: 53)

Taiwan was then turned from an

insignificant island into the most important entrepot in East

Asia:

The Cheng [Zheng] trading

junks also called in at Tonking, Quinam, Cambodia, Siam

and other ports of Southeast Asia to obtain

goods for their Chinese and Japanese trade. … In return exchanged Chinese goods

and Japanese copper and gold “koban”. Copper and gold were then re-exported to

the ports of India.

Thus, brisk trade was carried on with the neighboring areas, … the Cheng was

benefiting from the advantageous position of Taiwan,

and could still hold their dominant position as an important intermediary of

the international trade in East Asia. (Ts’ao 1972: 15)

Under Zheng Chenggong and Zheng Jing, the Zhengs

commercial empire transcended the phase of personal endeavor as characterized by

the trade networks of Zheng Zhilong. Zhengs’ commercial organization was

vertically integrated and bureaucratically administered, contrary to the

typical image of Chinese business as informal trade network. In terms of

economic size, the Zheng enterprise was well comparable to the VOC and even the

Qing continental empire at large. Below,

we will see how the Zhengs utilized their commercial income to build up a

political-military apparatus which is described by Wakeman as the “most

aggressive assault forces in all of East Asia”

(1985: 1047) at the time.

THE

BUILDING OF AN INDEPENDENT

IMPERIAL-MERCHANT STATE

Territorial Ambition of

Zheng Chenggong

Witnessing the unexpected reconsolidation and strengthening

of the Zheng family under Zheng Chenggong, the Qing government offered a

generous proposal to seek his cooperation in 1652. The Manchus promised a

semi-autonomous status and the release of his father to exchange for Zheng’s

submission. They also promised to grant the Zheng family a jurisdiction of four

prefectures. In an edict to Zheng, the Emperor wrote:

… Competent officials are

needed to defend [the coastal area] anyway. Why should I choose somebody else

to take up the duty? Isn’t it much better to give the responsibility to you and

your followers? … Now I would like to grant you the title of dukedom, and

actual administrative power. You will be able to share the merit of founding

the Empire, and your whole family will be honored… I will allow you to decide

how to defend against or get rid of the pirates in the Fujian area. I will also allow you to

manage, check and tax all seafaring ships. You can keep all of your original

officials and followers… If you accept my grace and trust, you should be responsible

for repaying me by serving me wholeheartedly. The peace and prosperity of the

coastal area are now in your hands… (CZSL: Yongli

8.1.10)

The

negotiation lasted for two years. Qing’s concession and patience are

understandable as the Manchus were not confident in crushing the Zhengs by

force, provided that the Manchu troops were indeed “baffled and frightened by

the sea,” though they excelled in land operations. (Struve 1988: 711; see also

Wills 1979:23; Foccardi 1986: 55) Had Zheng accepted Qing’s offer, a

configuration of power resembling that between Zheng Zhilong and the Ming

government would have been restored. Nevertheless, Zheng Chenggong was never

serious about the negotiation and knew about the Manchus’ weakness, as he wrote

to his father, who had been under Qing custody, at the beginning the negotiation:

The coastal area has long

been our possession. The profits from the Eastern and Western trade are well

enough for our own survival and expansion. We have much room to maneuver. Why

should I not enjoy this autonomy and subjugate myself to others? … In the Qing

court, there must be some officials with a good sense, and know that the

seashore of Fujian and Guangdong

is thousands miles away from Beijing.

The road in-between is so difficult that most of the soldiers and horses sent

to here would definitely be exhausted, sick and dead… (CZSL: Yongli 7.8)

Zheng was

actually not just concerned about securing his control over the coastal area.

During the temporarily peaceful environment in the early 1650s, Zheng was

preparing for a military campaign to expand his sphere of dominance to the

Yangzi Delta. A formidable political-military apparatus was built by using the

handsome trade revenue.

Zheng Chenggong established his own shipbuilding and

military industry in Xiamen.

The rich lacquer and oak resources in Fujian

were mobilized to build warships after European model. A large amount of

military supply, such as cannons, metal (for making weapons), and saltpeter

(for making gunpowder) was imported from Japan (Struve 1988: 699-701; Huang

1982: 265; Han 1984: 209; Li 1982: 226). By 1655, an army of 250,000

well-equipped fighting men and 2,300 ships was under Zheng’s command. (Struve

1988: 714). Politically, Zheng declared his allegiance to the faraway and

fragile Yongli court established in Southwest China by a Ming prince fled from Beijing in 1644. In this

way he could establish his legitimacy and summoned support from the Ming

loyalists in the coastal area without actual subjugation to any Ming monarch

and bureaucracy (Wills 1994: 226; Struve 1988: 712).

In 1655, Zheng renamed Xiamen

as Ximingzhou, or “Memorial Prefecture

for Ming,” and made it the capital of his regime. A Ming-style government was

established, comprising the ministry of secretary, finance, ceremony, military,

justice and public works. Zheng’s proclaimed loyalty to the Ming and his

impressive military might attracted a lot of disoriented Ming loyalists.

Ex-Ming officials alleged to him were appointed to govern the villages and cities

he captured. At its apogee, the Zhengs controlled eighteen prefectures in Fujian, four prefectures in Guangdong

and two prefectures in Zhejiang.

Regular taxation was imposed upon the population within his jurisdiction.

Archaeological evidence even showed that European-style and standardized silver

coins with Zheng Chenggong’s name on it were made and circulated in the area.

(Foccardi 1986: 45, 56; Wong 1983: 138, 142; Struve 1988: 714; CZSL: Yongli 9.2, 9.3; MHJY: Yongli 12.2; Guo1982 a & b)

In 1654, Zheng wrote to his father to stay his

determination to fight though the latter was still in Manchus’ hand. He declared

that “I have forgotten that I had a father for a long time” (CZSL: Yongli 8.4, 8.5). The Qing government

realized that any longing for peace would be unrealistic, and launched an

assault on Xiamen

in 1656. The Qing troops were repelled and decimated swiftly. After the

repulsion of the Qing assault, Zheng initiated the long-prepared campaigns

aimed at taking control of the Yangzi Delta. In the spring of 1658, right

before he set out to capture Nanjing, Zheng disclosed his ambition to his

generals, stating that “if we are successful in getting control of the Yangzi

River, half of the Empire at the River’s South will be mine” (HJJY: Yongli 12.5 29; see also CZSL: Yongli 9.1).

Though Zheng’s troops were victorious all along the Zhejiang coast and the Yangzi

River, they ended up in a disastrous

defeat by the Qing’s cavalry and infantry out of Nanjing’s city wall.(Struve 1988:718-21; Wills 1979: 226-27;

Foccardi 1986: 63-5; 67-70; CZSL: Yongli 13.7.17-13.7.23;

158-62; HJJY: Yongli 13.6; MHJY: Yongli 13.6-13.7; Wills 1994: 226-228;

Wakeman 1985: 1048) Nonetheless, Zheng’s navy was unscathed and was able to

transport all of the survivors back to Xiamen.

Realizing that expanding his territory in mainland China was out of question,

and cognizant of the news that the Yongli court collapsed after the Yongli

Emperor was arrested by the Manchus in Burma, Zheng changed his strategy by leaving

the mainland, taking Taiwan and turning it into his new base (Struve 1988:

705-10; 722; CZSL: Yongli 15.1; HJJY Yongli 15.3; MHJY: Yongli 15.3)

State-Building in Taiwan

In the spring of 1661, Zheng

summoned most of his warships and crossed the Taiwan

Strait. The Dutch were outnumbered and surrendered on February 1,

1662. A treaty was signed between Zheng and the Dutch Council in Taiwan that

allowed the former to confiscate all VOC’s property on the island and the

latter to evacuate peacefully (Coyett 1903 [1675]: 414-55; Ts’ao 1972:12; HJJY:

Yongli 15.3-16.2; MHJY: Yongli 15.3-16.2 ; CZSL: Yongli 15.4.1-15.5.2).

Zheng Chenggong recentered his regime at Taiwan

immediately. Fort

Porvintia, a military

castle built by the Dutch, was renamed Dongdumingjing,

or the “Ming Eastern Capital.” It became the new capital of the Zheng

Empire, replacing the endangered Xiamen.

Taiwan was renamed Dongningzhou, - “the Prefecture of Peace

at the East.” (MHJY: Yongli 16.2;

HJJY: Yongli 16.2; CZSL: Yongli 15.5.2; QSGZCGZ :56) Zheng did

not abandon the Ming calendar, custom and style of clothing, nor did he

relinquish the claim of crushing the Manchus someday. Nevertheless, in an edict

outlining the principal policies of his new government in Taiwan, he

declared to his followers that “now we establish our families and found our

nation [kaiguolijia] in the Ming

Eastern Capital. The foundation of our enterprise cannot be uprooted for tens

of thousands of generations.” (CZSL: Yongli

15.5.18)

Institutions such as Confucian academies, prisons

and salt plants were founded in Taiwan.

Population and land census were carried out. An examination system for the

selection of civil officials and a welfare system taking care of the aged and

weak were established (ZCGZ: 22; ZSGZCGZ: 56; MHJY: Yongli 18.3). The Dutch system of tax farming was inherited. More

advanced agricultural methods were introduced to the residents. Zheng also encouraged

his officials to take uncultivated land and turn it into their own estates,

with an obligation of fulfilling the tax quota imposed. Soldiers were sent with

seed and plows to reclaim the remaining land. The provision problem was solved

and a fiscal system with an agrarian-bureaucratic outlook took shape (CZSL: Yongli 15.5.18; HSJWL: Yongli 21; Shepherd 1993: 93-4, 97).

Before the Nanjing

failure, Zheng Chenggong aspired to controlling the South of Yangzi River.

After his retreat to Taiwan,

he began to present himself as the political leader of the overseas Chinese. In

fact, one of the stated reasons for his expedition to Taiwan was to

liberate the Chinese migrants and aborigines from the Dutch tyranny (HJJY: Yongli 15.3; MHJY: Yongli 15.3). Later, Zheng threatened to punish the Spanish

harassment of Chinese in the Philippines

by conquering the archipelago (Foccardi 1986: 97). The political project of the

Zhengs was ever changing. It seems that Zheng, and more notably his successors,

were downplaying their ambition of conquering mainland China, and were

more occupied with strengthening their independent power in the maritime zone

of East Asia. It can be reflected by the position of the Zhengs during their

intermittent negotiation with the Qing government between 1663 and 1683.

Between 1663 and 1683, the Qing government

repeatedly sought the surrender of the Zhengs by presenting the offer of

semi-autonomous status as it was promised to Zheng Chenggong in 1652. Every

time the Zhengs returned with a counterproposal. They promised they would give

up armed struggle against the Qing if the later granted Taiwan the status of a tribute vassal,

“following the example of Korea

and Ryukyu.” In that case Taiwan

would “pay tribute [to the Qing Emperor] without shaving their hair and

settling back to Mainland China”

(HSJWL: Yongli 23; HJJY Yongli 16.6, 23, 31.12, 32.10, 33.7; MHJY:

Yongli 23, 31.12; PDHKFL: 4.1-4.2;

ZCGZ: 26; QSLZZZLZ: 48; QSGZZGC: 57, 60; QSL: Kangxi 22.5.23). Zhengs’ request was never accepted, as the Kangxi

Emperor was firm that “the thieves in Taiwan

are Fujianese, Taiwan is

incomparable to Korea

and Ryukyu” (QSL: Kangxi 22.5.23;

PDHKFL: 4.1-4.2).

After the Qing quitted its attempt to conquer Taiwan, Taiwan was no longer regarded as an

important issue in the Qing government. The troops stationed in Fujian were reduced.

(HJJY: Yongli 23; MHJL: Yongli 18, 19; see also QSL: Kangxi 5.1.26) The Manchus even did not

consider Taiwan

as part of the Qing Empire.

A de facto independent kingdom of Taiwan was in place. This was well

described by a Qing writer that:

After Shi Lang was called back to Beijing,

[Zheng’s] surrendered soldiers were dispersed and stationed in different

provinces, and the coastal area was strongly fortified and defended, [the Qing

government] diverted its attention from Taiwan. At the same time, [Zheng]

Jing’s army had not been mobilized [to attack the coastal area]. Henceforth,

there were a number of years of peace (QSGZCGZ: 57).

Having survived the succession crisis subsequent to

Zheng Chenggong’s death, the Zheng regime was reconsolidated in Taiwan. Zheng

Jing ousted his opponents and became the heir of the throne. With the peaceful

environment after 1665, and being successful in breaking the embargo through

smuggling, the Zhengs were able to recover from the losses of the early 1660s

and further expand their maritime empire. Zheng Jing’s inclination to

consolidate an independent, maritime power in Taiwan was illustrated by his

letter to a Qing negotiator in 1667:

Today’s Dongning [Taiwan], having thousands of miles

of land, has become an independent glory out of the [Qing’s] territory. We have

food storage enough for several decades, and the barbarians from all directions

are complying with us. All goods are circulating smoothly, and our people live

and are educated well. We are able to live strongly and healthily on our own.

Why should we adore the title of dukedom? Why should we want the lands in

mainland? If the Qing court really cares about the livelihood of the coastal

residents, it should treat us with the rites of dealing with a foreign

countries [yi waiguo zi li jiandai],

opening trade with us, withdrawing the troops and letting the people rest, then

I will definitely follow. (KXTYTWDASLXJ: 69)

In the early 1670s, the prosperity and stability of

the Taiwan kingdom peaked

with the pinnacle of Zhengs’ prestige in maritime East

Asia, as shown by the European perception of the Zhengs as presented

in the paragraphs quoted in the beginning of this essay. By then, nobody in the

world, including the Qing court, would expect the sudden collapse of the Zheng

Empire and a quick resolution of the Taiwan question. But it did happen.

THE

COLLAPSE OF THE ZHENG REGIME

At the end of 1673, the Rebellion of the Three

Feudatories – Wu Sangui in Yunnan, Shang Kexi

in Guangdong and Geng Jingzhong in Fujian – broke out in the mainland. Zheng saw it as

an opportunity to fight back to China

and decided to join the Rebellion promptly. An anti-Manchus alliance between

Zheng and Wu was formed, and a Geng-Zheng united operation to capture the Lower Yangzi region was seriously considered. (HJJY: Yongli 24.2-28.10; MHJY: Yongli 28; MHJL: Yongli 28.2-28.5; Foccardi 1986: 110-3; Wakeman 1985: 1099-1127)

In 1674, Zheng Jing recaptured a number of coastal

cities in Fujian including Xiamen. Most residents evacuated from the

coastal area moved back. Soon Zheng’s army pushed into Guangdong. In 1676, his forces reached the

vicinity of Guangzhou.

(HJJY: Yongli 28.7, 30.2; MHJY: Yongli 29.5, 29.6, 30.1, 30.2; Foccardi

1986: 113; QSGZCGZ: 58) The English regarded the Zheng’s revival in the

mainland as a golden opportunity for them to open the China trade. In

1675, the EIC, states of Annam

and Siam sent their envoys

and tributes to Taiwan and

asked for trade in coastal China.

Subsequently, Xiamen

reopened for free trade and became a lucrative city again. A new commercial

headquarter of EIC was established there (HJJY: Yongli 29.6, 32.12; MHJY: Yongli

29.6; MHJL: Yongli 29.6; Ju 1986:

140; QSGZCGZ: 58).

In the middle of the 1670s, the Zhengs regained its

glory in coastal China.

However, their ambition soon backfired, as the unfruitful campaign triggered a subsistence

crisis in Taiwan.

The Zheng family had been facing the difficulty of feeding their army ever

since the 1650s. Owing to land infertility, Fujian was “a major rice-importing region

famous for buying rice at a high price” in the seventeenth century

(Kishimoto-Nakayama 1984: 230). Zheng’s trading networks never penetrated into

the rice exporting provinces such as Hunan

and Shangdong, which were firmly controlled by the Manchus. The Lower Yangzi

Delta, from where most of Zheng’s purchases came, was itself a rice deficient

area because of its specialization in cash crop cultivation after the sixteenth-

century commercial revolution (Li 1986; Chen 1991: 70-77).

Zheng Chenggong’s remedies in the 1650s were

establishing soldier colonies (tuntian)

and raiding the Qing granaries. The first method was not reliable so far as the

soldiers were frequently mobilized for the endless military campaigns. The

second method became the most crucial one. It is estimated that between 1656

and 1661, Zheng at least launched 24 military actions with the primary

objective of seizing food. Still, Zheng’s rice storage was never enough for

more than a few months. When Zheng’s freedom of action was strictly limited

after the Nanjing

failure, the provision crisis sharpened (Yang 1984a: 89; see also CZSL: Yongli 7.8, 10.10.6; 10.12.29 for

examples).

To a certain extent, the conquest of

Taiwan

was a conscious attempt to find an ultimate solution for the problem. Zheng

Chenggong persuaded his generals to support the expedition to oust the Dutch

and take Taiwan by

emphasizing that the Island was full of

virgin, fertile land (CZSL: Yongli

15.1; HJJY: Yongli 15.3, MHJY: Yongli 15.3; see also Wills 1979: 228;

Yang 1984a: 90). Even though Zheng’s army took over all of the food storage

left by the Dutch, the first year of the Taiwan regime was still under a

near-famine situation. Preventing their alienation from the local population,

the Zhengs disciplined their soldiers strictly and kept them from looting the

Chinese and aborigine villagers. Staples were purchased from the residents at high

prices. The expected food supply from Xiamen

was delayed many times. Rice was rationed. Some officers started eating wood

debris and many fell sick (CZSL: Yongli

15.3.27-15.4.1, 15.6-15.8.28; Shepherd 1993: 94). Zheng Chenggong’s planned

assault on Manila right after he set his foot on

Taiwan

might have something to do with the food shortage.

With the aggressive policies of

increasing agricultural productivity, clearing tax delinquency, and turning all

soldiers into colonizer-farmers, the food shortage was alleviated in the

following year. Agricultural manpower increased considerably by the influx of

refugees driven out of the coastal regions by Qing’s evacuation. Temporary rice

supply was raised by the duty fee policy that encouraged rice imports from Southeast Asia. These efforts ended up in the great

harvest of 1666, which marked the beginning of the golden age of the Taiwan kingdom.

(Wong 1983: 153; Shepherd 1993: 96-100; Ts’ao 1972: 15) However, the affluence

of Taiwan

was interrupted by Zheng Jing’s participation in the Rebellion of the Three

Feudatories. The new round of coastal warfare threw the Zheng Empire into the

most serious provision crisis it ever confronted. It was exactly this crisis

that brought Zheng’s prowess to an abrupt end.

In 1674, all of the soldier

colonists in Taiwan –

numbered to around 18,000 – were called to leave their fields and head for Fujian. As these

soldiers constituted one-third of the total Chinese population of Taiwan and was

the core productive force on the island,

their sudden departure led to an immediate downturn of agricultural output.

Worse, a substantial portion of the already discounted food supply in Taiwan was shipped to Fujian to support the military campaign.

When Zheng Jing found that the Taiwan supply was insufficient, he issued an

order allowing the extraction of cash and grain taxes from the mainland

residents who just resettled in the his occupied territories after Zheng

revoked the evacuation policy there. (HSJWL: Yongli 28.12; HJJY: Yongli 28.12)

As long as Zheng was expanding his

territory in the mainland between 1674 and 1676, especially after they entered

the heartland of Guangdong

in the spring of 1676, the problem of food supply was contained. However,

following the surrender of Geng Jingzhong at the end of 1676 and the surrender

of Shang Zhixin in spring 1677, Zheng was isolated and kept losing grounds to

the Manchus. The morale of the army eroded with the diminishing of provisions,

and a vicious circle ensued. In 1677, with all major coastal cities lost, a

majority of Zheng troops retreated to Xiamen

with hunger. Every Xiamen

adult citizen was forced to submit one dou

of rice to the army every month. Tax evasion was widespread. Zheng’s generals

suggested pulling all remaining troops out of the mainland. Zheng Jing was

hesitant initially and started sending back his generals’ families back to Taiwan. But

after a month or so he rejected the proposal and insisted on staying. When the

seesawing between Zheng and Qing went on, the tax quota was tripled, and an

additional cash tax was levied in 1679. (HJJY: Yongli 31.2, 33.2; MHJY: Yongli

31.2 MHJL: Yongli 31.2, 31.3, 33.3)

Though Zheng managed to regain some

grounds in Fujian

in 1677 and 1678, his military structure fell apart. The shipment of grain from

Taiwan

was frequently interrupted. Brutal violence of Zheng’s army such as arbitrary

extortion, looting of civilian property, and burning of villages refusing to

pay taxes was widely reported. Hungry generals and soldiers surrendered one

after the other, given the Qing promise of amnesty and rewards. In 1680, having

heard of the news that the Qing reinforcement was coming close to Xiamen,

Zheng’s fighters rushed onto the ships and headed back to Taiwan in a stampede.

Qing took the city without any resistance. The Xiamen residents had suffered so much that

they welcomed the Qing troops with joy. (HSJWL: Yongli 32.3, 34.1-34.4; HJJY: Yongli

34.2.28; MHJY: Yongli 34.2; MHJL: Yongli 32.8.24, 33.3)

In 1679, Zheng Jing realized that

the day of his kingdom was numbered. He lost his will to rule and handed the

actual leadership to his son, Zheng Kezang, who was then 16 years old. (HJJY:

33.2; MHJY: 34.10) Jing died in 1681 and a bloody coup d’etat followed suit.

Zheng Jing’s wife and her allies murdered Kezang and purged his supporters. Jing’s

another son, Zheng Keshuang was made the new leader of the regime, despite the

fact that he was only 12 years old. (HJJY: Yongli

35.1-35.2; MHJY: Yongli 35.1-35.2)

The return of the exhausted and hungry soldiers in 1680

exacerbated the food crisis and ungovernability of the island. The situation in

1680 was much tougher than that in 1662. This time, the Zhengs had no Dutch

granaries to seize. The rice storage of the island was already almost exhausted,

and the treasury of the government had been dried up because of the expedition.

The Zhengs tried to mitigate the crisis by extending and intensifying tax

extraction. A large number of villagers reacted by burning down their houses,

fleeing to the mountain and evading the tax. Some of the soldiers revolted for

payment, in resonance with a series of aborigines rebellions. Grain price

skyrocketed and a famine broke out in the winter of 1682. The crisis was

aggravated by a fire that wiped out 1,600 houses in Tainan, the capital city of the Zheng regime.

In the spring of the next year, a massive famine broke out. (HSJWL: Yongli 36.1; HJJY: Yongli 36.7, 36.12, 37.1; MHJY: Yongli

35.10-37.1; MHJL: Yongli 37.2; see

also Shepherd 1993: 103)

Disregarding the hesitation or opposition of most

officials, the Kangxi Emperor decided to grasp the chance and take the risk of

attacking Taiwan

in 1680. The Emperor had not shut the door of peace, however. Accompanying the

preparation for the campaign, the same offer of a semi-autonomous status was

presented to the Zhengs in 1680 and one more time in 1683. The negotiations

broke down again as the Zhengs were still insisting on a status of tribute

vassal. They might still believe that the Manchus would not have the courage

and capability to cross the Taiwan Strait.

(PDHKFL: 2: 3, 3: 1, 4: 1-2; Wong 1983: 175; QSL: Kangxi 19.8.5, 22.5.23)

In spite of the widespread chaos, Taiwan was

still well defended. After an initial setback, the Qing troops landed on the

strategic Panghu Islands West of Tainan amid an unexpectedly favorable weather

in July 1683. On the Islands, a fierce battle

endured for seven days. The Qing force cleared the Zheng’s forces at a high

cost. In addition to tremendous losses in soldiers and warships, many high rank

commanders were killed. Even the commander in chief was seriously injured. The

Qing force was apparently not able to recoup and push forward immediately.

Zheng’s generals proposed an expedition to invade the Philippines and

“rebuild the nation” (zaizuoguojia)

there. The plan was abandoned at last when the morale continued to fall and

pessimism grew. Zheng’s followers defected successively. At last, the Zhengs

surrendered unconditionally in August.

Zheng Keshuang was granted the title of dukedom (though without actual

power) and resettled ashore. The loyal generals of Zheng were treated well and

placed into high positions in the Qing land forces.

The Zheng Empire vanished. (PDHKFL: 4:1-4, 6; HSJWL: Yongli 37.6-37.12; HJJY: Yongli

37.6, MHJY: Yongli 37.6; MHJL: Yongli 37.6; ZCGZ: 38-9; QSLZZZLZ: 48-9;

QSGZCGZ: 60-61; Shepherd 1993: 474;Wong 1983: 180-5; QSL: Kangxi 22.6.29-22.9.10, 23.3.6)

After a brief confusion in the Qing

court, Taiwan

was at last incorporated into the Empire in 1684. The island was colonized

after it was strongly fortified. In 1683, all restrictions on seafaring

activities were lifted by the Qing government. Chinese merchant groups were

active in the coastal area again. However, to preempt the possibility of any

trouble from those private traders, the authorities watched the shipbuilding

industry closely. Strict regulations were imposed to restrict the size and

weight of seafaring ships. No weapons were allowed on board. (Tian 1987: 12-6;

QSL: Kangxi 22.10.10, 23.1.21) A new

era of maritime trade in China

came, and it was wittily captured by Wills (1991) as an era when “trade was

legal, but maritime China

had lost it fragile political autonomy” (54; see also Ng 1991, 1983).

THE

CONTINGENT NATURE OF THE FALL OF TAIWAN

The records of the EIC shows that the English in

Taiwan were well aware of the fact that Taiwan fell not because of the might of

Qing’s navy but the internal turmoil on the Island. By the time the Qing force

had captured the Penghu

Islands, the Zhengs were

troubled by “being poor, and provisions most excessive deare.” And “[t]he King

[of Tywan] and Grandees, observing the discontent of the poor, and of the army,

resolved that it was impossible any longer to continue the contest, or for the

King to retain the throne of his ancestors” (quoted by Paske-Smith 1930: 117).

Had Zheng Jing not fought back to the mainland in

1674, or had he accepted his generals’ suggestion of pulling out in 1677, the

subsistence crisis of Taiwan

in 1680 might not have broken out and the Taiwan government would not have

collapsed. The most probable alternative outcome would be the continuing

coexistence of the two rivalries across the Strait. If the Zhengs had no seized

the opportunities given by the Rebellion of the Three Feudatories to embark on

the adventure of regaining their grounds in mainland China, they would have likely expanded

his territory in the maritime zone instead. As we have seen, the conquest of

the Philippines

was always on their agenda. Zheng Jing was actually preparing for an expedition

to Manila right

before the Rebellion in the mainland erupted.

Maybe some will argue that the

failure of the Zhengs was still inevitable as their commercial profits relied

so heavily on the goods from the mainland. Smuggling might go on in large

volume for some time. But it would be crushed by the Qing government someday

after it managed to consolidate itself, as it actually did in the eighteenth

century. But the question is, was the Qing consolidating itself during the

deadlock across the Taiwan Strait?

After the Manchus failed to conquer Taiwan, they

quitted trying to defeat the Zhengs by force. What they could rely on was its

ineffective and even counterproductive scorched-earth evacuation policy, as we

have seen. On the other hand, the sea ban brought a great damage to the Qing

economy, which was as silverized and commercialized as the late Ming economy,

for it cut the mainland off from all sources of silver supply. By the 1650s,

the Manchus had built up an efficient Imperial bureaucracy, resumed regular

taxation, and put down most contenders of power. High level of political

stability was attained, and production recovered. (Wakeman 1985: 1050-1127)

Nonetheless, the evacuation policy created an empire-wide silver shortage. The

situation was worsened by the increasing military expenditures incurred by the

hostilities across the Taiwan Strait.

The result was a deteriorating fiscal deficit of the

Qing state. In 1661, the Qing government imposed extra taxes to make ends meet.

Nearly 5.7 million taels of silver

were levied in addition to regular tax that year. The silver shortage led to

serious deflation. Peasants, merchants and landlords were hit hard as they

became incapable of fulfilling the ever-increasing tax quotas. Many Qing

officials were aware of the connection between the economic crisis and the

evacuation policy, and advocated a relaxation of the sea ban. Now the

empire-wide economic downswing between circa 1656 and 1680 is well documented

and is known as the “Kangxi depression.”

(Wakeman 1985: 1070, 1070ff; Huang 1969: 122; Vogel 1987: 2; Kishimoto-Nakayama

1979, 1984; Atwell 1986)

It is unclear how the “Kangxi depression” was

related to the reappearance of political upheavals in the 1670s. But in 1672,

on the eve of the Rebellion of the Three Feudatories, an able secretary of the

governor of Zhejiang

noted that,

The whole land has now been brought under the same

rule, the only exception is Taiwan,

but it is located far beyond the sea and cannot do any harm to our land and

people. The present dynasty commands the largest area of land in history. But

land without people is worthless and people without wealth is valueless, and in

the present dynasty, we find that the poverty afflicting the whole population

is unprecedented in the history of China. (Wei Jirui, quoted in

Kishimoto-Nakayama 1984: 229)

There

were not many choices in front of the Qing government. If it had insisted on

continuing the evacuation policy, its fiscal and economic crisis might not have

been solved and it might have crumbled at last. If it had yielded to the pressure

of silver shortage and lifted the sea ban, the supply problem of Taiwan would have

been solved once and for all, and the Zheng regime could have persisted

successively established itself as an independent tribute vassal of the Qing

empire as it wished.

Viewed in this light, the final stabilization of the

Qing Empire in the eighteenth century – which was a result of the massive

influx of American silver after the lifting of sea ban (see Quan 1987, 1996a) –

cannot be taken for granted. It is wrong to suppose that the Zhengs were

destined to fail when a land-oriented and strong dynasty was restored in the

mainland. In fact, the final consolidation of such a dynastic order was to a

certain extent a function of the contingent resolution of the Taiwan question.

Have the Zheng Empire survived into the eighteenth

century in one way or other, the development of Chinese merchants’ military

capabilities, and their supremacy in maritime East Asia

would have continued. The history of East Asia and China in the following centuries,

in that case, would have been very different from what we know it today.

CONCLUDING

REMARKS

To recapitulate, we see that the business of the

Zhengs was much more than a mere familial venture. Beging as a familial network

of armed traders under Zheng Zhilong, the enterprise was an accumulative

outcome of protracted illegal trade and military conflict in coastal China since the

mid-sixteenth century. When Zheng Zhilong joined the world of maritime East Asia in the 1620s, there were numerous preexisting trade

networks having developed for over one hundred years. What Zheng achieved was

to take over and unify this bulk of networks – and all related “hardware” such

as junks and ammunition. Then Zhilong’s trade network was transformed radically

by Zheng Zhenggong into a vertically integrated and bureaucratically managed

organization well comparable to the VOC in its structure and economic size. The

organization was not a joint stock company, but it was more than a one-family

business. Behind it was a community of independent Chinese traders protected

and financed by the Zhengs.

Upon the profits generated from this enterprise, the

Zhengs instituted a political-military apparatus for realizing his territorial

ambition and facilitating the enterprise’s further commercial expansion. Of

course, the Zheng regime, though was financed principally by trade revenue, was

no Republic, as its political form was a replica of the Ming Imperial

government. Hence I identify the regime as an Imperial-Merchant state rather

than merely a merchant state. In the 1660s, the Taiwan-based Zheng regime was

turned into a de facto independent power that invites comparison with other

maritime states in Asia such as Oman

and Siam.

It even nearly took onto the path of overseas colonialism, as the conquest of

the Philippines

recurrently appeared on their agenda.

The relation between the Zhengs and

the Qing Empire was constantly in flux. They kept changing their ambitions and

strategy against the other along the way. After the nascent Qing regime found

it impossible to subject the Zhengs by force, it turned to seek to build an

alliance with them by granting them semi-autonomous power to govern the

Empire’s Southeast coast. The Qing proposal was rejected by the Zhengs, who

first were aspired to controlling the southern part of China, and later to building an independent

state on Taiwan following

the example of the kingdom

of Korea and Ryukyu. By

the 1660s, the Qing government had abandoned conquering Taiwan and was

about to leave the Zhengs there. The Manchus would not have been able to

incorporate Taiwan in the

Empire in 1683, had the Zheng regime not collapsed in 1680 under the weight of

its retrospectively miscalculated decision of fighting back to China in the

1670s.

The Zheng’s final collapse was contingent upon a

number of factors, and was never predetermined. Any teleological account of its

final failure, and the conception that the maritime communities of China were exceptionally and essentially weak as

compared with other commercial groups in maritime Asia

has to be revised. On the other hand, we would suspect whether the

extraordinary economic and politico-military strength of the Zheng was

exceptional compared with other indigenous maritime powers in Asia, hence

constituting another kind of China

exceptionalism. How is the Zheng Empire compared with other

political-commercial actors in maritime Asia,

such as the Omanis state? How was the path of “interactive emergence of

European dominance” at the expense of indigenous traders in East Asia similar

to or different from the paths in other sub-regions in Asia?

Had the Zheng Empire survived, would it have grown into the greatest stronghold

of maritime Asia against European encroachment and revised the course of European

expansion at large, provided with the centrality of Chinese products in the

world market, as well as East Asia’s geographical remoteness from Europe? They are the questions that await further

exploration.

Figure 1

Zheng’s Central

Administration

Financial

Minister

Monitoring Officer

Financial

Minister

Monitoring Officer

(huguan)

(lucha)

Treasuries

Treasuries

Western Eastern Inland Five Overseas Five

Sea Fleet Sea Fleet Companies Companies

(xiyanchuan) (dongyangchuan) (shanluwushang) (shuiluwushang)

Independent Merchants

Independent Merchants

Co-ordinating

Co-ordinating

Financing

Financing

Figure 1. Vertically Integrated

Business Organization of the Zheng Regime

Derived from CZSL (Yongli 11.50) and Nan

(1982)

References

Primary

Sources

Anonymous 1906 [1663]. Events in Manila,

1662-63 in E. H. Blair and J. A. Robertson ed. The Philippine Islands 1493-1898. Vol.

36. Cleveland, Ohio: The Arthur H. Clark Company.

Coyett, Frederick 1903 [1675]. Verwaerloosde Formosa

in William Campbell ed. 1903. Formosa Under the Dutch: Described From

Contemporary Records. London:

Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. 383-538.

CZSL: Yang Ying 1958 [1672]. Congzheng shilu Taipei: Taiwan yinxing

jinjie yanjiushi.

HJJY: Haiji

jiyao. Huang Dianquan ed. 1957. Zhengchenggong

shiliu hekan. Taipei:

Haidong shufang. 22-49.

HSJWL: Haishang

jianwenlu. Huang Dianquan ed. 1957. Zhengchenggong

shiliu hekan. Taipei:

Haidong shufang. 1-21.

MHJL: Minghai

Jilue. Huang Dianquan ed. 1957. Zhengchenggong

shiliu hekan. Taipei:

Haidong shufang. 79-101.

MHJY: Minghai

Jiyao. Huang Dianquan ed. 1957. Zhengchenggong

shiliu hekan. Taipei:

Haidong shufang. 50-78.

QSGZCGZ: Qingshigao

zhengchenggong zhuan. Taiwan

yinxing jinjie yanjiushi ed. 1960. Zheng

Chenggong chuan zhujia Taipei: Taiwan yinxing

jinjie yanjiushi. 51-62.

QSLZZZLZ: Qingshi

liezhuan zhengzhilong zhuan In Taiwan yinxing jinjie yanjiushi ed.

1960. Zheng Chenggong chuan zhujia Taipei: Taiwan

yinxing jinjie yanjiushi. 4-50.

QSL: Zhang Banzheng ed. 1993. Qing shilu: Taiwan

shi ziliao zhuanji. Fujian: Fujian renmin chubanshe.

PDHKFL: Guoli zhongyang yinjiuyuan lishi yuyian yanjiu

suo ed. 1930 [Qing] Pingding haikou fanglue Beijing:

Guoli zhongyang yinjiuyuan lishi yuyian yanjiu suo.

MSL: Li Hung and Xue Guozhong ed. 1993. Mingshilu leizuan: fujian

taiwan

juan. Wuhan: Wuhan renmin chubanshe.

TWWJ: Jian Risheng 1986 [1704]. Taiwan weiji. Shanghai: Shanghai gujie chubanshe.

ZCGZ: Zheng

Yizou Zheng Chenggong zhuan in Taiwan yinxing jinjie yanjiushi ed.

1960. Zheng Chenggong chuan zhujia Taipei: Taiwan

yinxing jinjie yanjiushi. 1-40.

Secondary

Sources

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power,

and the Origins of Our Times. London:

Verso.

Atwell, William S. 1986. “Some Observations on the

‘Seventeenth-Century Crisis’ in China

and Japan.”

Journal of Asian Studies. XLV: 2.

223-44.

Blusse, Leonard 1981. “The VOC as Sorcerer’s

Apprentice: Stereotypes and Social Engineering on the China Coast.”

W. L. Idema. Leyden Studies in Sinology. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 87-105.

Boxer, Charles R. 1988. Dutch Merchants and Mariners in Asia:

1602-1795. London:

Variorum Reprints.

Chao, Zhongchen 1993. “Wanming baiyin daliang liuru zi

yingxiang” Lishi yanjiu yuekan. 93:1.

33-39.

Chen, Bisheng 1984. “Zheng zhilong de yisheng.”

Fujiansheng zhengchenggong xueshu tulunhui xueshu ju. ed. Zhengchenggong yanjiu luncong. Fuzhou:

Fujian jiaoyu

chubanshe. 148-64.

Chen, Xuewen 1991. “Mingqing shiqi minyuetai diqu de

zhetangye.” Chen Xuewen. Minging shehui

jinjieshi yanjiu. Taipei:

Hedao Chubanshe.67-86.

Croizier, Ralph C. 1977. Koxinga and Chinese Nationalism: History, Myth, and the Hero. Cambridge, MA: East Asian Center, Harvard

University.

Fan, Jinmin 1998. Mingqing

jiangnan shangye de fazhan. Nanjing: Nanjing daxue chubanshe.

Flynn, Dennis O. and Arturo Giraldez. 1995. “Born with

a ‘Silver Spoon’: The Origin of World Trade in 1571.” The Journal of World History. 6:2. 201-221.

Foccardi, Gabriele 1986. The Last Warrior: The Life of Cheng Ch’eng-Kung, The Lord of the “Terrace Bay” – A Study on the T’ai-Wan

Wai-Chih By Chiang Jih-Sheng (1704). Venice:

Otto Harrassowitz Wiesbaden.

Glamann, Kristof 1958. Dutch-Asiatic Trade: 1620-1740. Copenhagen: Danish Science Press.

Guo, Moruo 1982a. “Yao zhengchenggong yinbi de faxian dao

zhengshi jinjie zhngce de gaibian.” Xiamen

daxue lishixi. ed. Zhengchenggong yanjiu

luanwenxuan Fuzhou:

Fujian renmin

chubanshe. 104-23.

---- 1982b. “Zaitan yauguan zhengchenggong yinbi de

yixie wenti.” Xiamen

daxue lishixi. ed. Zhengchenggong yanjiu

luanwenxuan. Fuzhou: Fujian renmin chubanshe. 124-35.

Hamashita, Takeshi 1988. “The Tribute Trade System and

Modern Asia.” The Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko. No. 46.

7-25.

---- 1994. “The Tribute Trade System and Modern Asia.” In A. J. H. Latham and H. Kawakatsu eds. Japanese Industrialization and the Asian

Economy. 91-107. London and New York: Routledge.

Han, Zhenhua 1982. “Zhengchenggong shidai di haiwai

maoyi he haiwai maoyisheng de xingzhi, 1650-1662.” Xiamen daxue lishixi. ed. Zhengchenggong yanjiu luanwenxuan. Fuzhou: Fujian

renmin chubanshe. 136-87.

----- 1984. “Zailun zhengchenggong he haiwei maoyi de

guanxi.” Xiamen

daxue lishixi. ed. Zhengchenggong yanjiu

luanwenxuan II. Fuzhou: Fujian renmin chubanshe. 206-20.

He, Fengquan 1996. Aomen

yu putaoya dafanchuan: putaoya he jindai zaoqi taipingyang maoyiwang de

xingcheng. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe.

Howe, Christopher 1996. The Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy: Development and Technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War. Hong Kong: Oxford UP.

Huang, Ray 1969. “Fiscal Administration During the

Ming Dynasty.” Charles O. Hucker ed. Chinese

Government in Ming Times. New York and London: Columbia

UP.

Huang, Yuzhai 1982. “Zhengchenggong shidai he

ribandichuanmufu.” Fujian

sheng zhengchenggong xueshu tulunhui xueshu ju. ed. Taiwan Zhengchenggong yanjiu lunwenxuan. Fuzhou: Fujian

renmin chubanshe. 263-70.

Ju, Delan 1988. “Qing kaihai cinghou de zhongri

changqi maoyi (1684-1722)”) Selected

Essays in Chinese Maritime History III. Taipei: Academia Sinica. 369-415.

Kawakatsu, Heita 1994. “Historical Background.” A. J.

H. Latham and H. Kawakatsu eds. Japanese

Industrialization and the Asian Economy. 4-8. London

and New York:

Routledge.

Kishimoto-Nakayama, Mio 1984. “The Kangxi Depression

and Early Qing Local Markets.” Modern China 10:2.

227-56.

Lai, Yongxiang 1982. “Zhengying tongsheng guanxi zi

jiantao. Fujian

sheng zhengchenggong xueshu tulunhui xueshu ju. ed. Taiwan Zhengchenggong yanjiu lunwenxuan. Fuzhou: Fujian

renmin chubanshe. 271-92.

Lee, John 1999. “Trade and Economy in Preindustrial

East Asia, c. 1500 – c. 1800: East Asia in the

Age of Global Integration.” Journal of

Asian Studies. 58(1). 2-26.

Li Ruiliang 1982. “Zhengchenggong yu haiwai maiyi.” Xiamen daxue lishixi. ed.

Zhengchenggong yanjiu luanwenxuan. Fuzhou: Fujian renmin chubanshe.

223-321.

Li, BoZhong 1986. “Jiangnan yu qita shengfen