Crisis of What: the end of capitalism or another systemic

cycle of capitalist accumulation?

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

Riverside, CA 92521

v. 6/7/13 8519 words

Paper to be presented at the Global Studies Association Conference on “Surviving the Future: Owning the World or Sharing

the Commons” June 7-9, 2013 at Marymount

College: Palos Verdes Campus (Los Angeles). This

is IROWS Working Paper #81 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows81/irows81.htm

Abstract: This paper discusses the nature of the

current global systemic crisis in order to evaluate the likelihood of several

possible futures in the next few decades. Employing a comparative world

historical and evolutionary world-systems perspective, I consider the ways in

which the contemporary crisis is similar to or different from earlier crisis

periods in the evolution of global capitalism and how the constellation of antisystemic movements and challenging regimes are similar

to, or different from, the challengers in earlier crisis periods. I designate

alternative possible models and discuss contending proposed visions of the

human future and use a structural analysis of social change to assign

probabilities to the different outcomes, while acknowledging that the future,

like the past, is somewhat open-ended and the somewhat unpredictable actions of

individuals and groups can shift the probabilities that we are trying to

estimate.

The comparative

evolutionary world-systems perspective uses comparisons between small

world-systems of foragers with expanding systems in the Bronze and Iron Ages as

well as an evolutionary perspective on the modern world-system since the 13th

century to comprehend the nature of the current world-historical period and the

probabilities of different sorts of reorganization that could occur within the

next several decades (Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2013). The focus is primarily on the

forest rather than the trees. And different kinds of forests are compared with

one another and ascertain how they have evolved over long periods of time. One of the big ideas that has emerged from this

comparative and evolutionary perspective is the notion of “semiperipheral

development” --

the idea that semiperipheral polities

often contribute to systemic social change by implementing organizational and

ideological forms that facilitate their own upward mobility and that sometimes

transform the logics of social reproduction and development. This paper

considers the question as to how contemporary semiperipheral

national regimes and alliances of these with one another, as well as with

transnational social movements -- might either mainly reproduce the existing

institutional structures and logic of the capitalist world-economy while

undergoing a shuffling of the predominant centers of accumulation or might

transform the global system into a qualitatively different, more egalitarian

world society in the next several decades. In order to intelligently comprehend

the possibilities for the next several decades we need to compare the current

world historical situation with earlier conjunctures that were somewhat

similar, but also importantly different. Sorting out the differences as well as

the similarities is a crucial task for these purposes.

The evolution of the modern

world-system has been composed of the expansion and deepening of commodified processes of production and accumulation, but

also of the evolution of the institutions of global governance. The structures

of authority have evolved from tributary empires to national states

increasingly controlled by capitalists, and an interstate system that

reproduces national sovereignty. Global governance in this system has mainly

been organized by a series of hegemonic core states – the Dutch in the 17th

century, the British in the 19th century and the U.S. in the 20th

century. And the increasing size of the hegemons has resulted in a cyclical trend

toward greater centralization of global governance. The decolonization of the

great colonial empires of the European core states extended the system of

theoretically sovereign nation-states to the non-core, creating an isomorphic

global polity of national states. But international political organizations and

super-national regional and global institutions have emerged over the tops of

the states composing the interstate system over the past 200 years. And

institutions of neo-colonialism such as foreign investment, aid regimes, and

covert political manipulation of non-core states by the Great Powers, have

reproduced the hierarchical nature of the global political economy.

The

political globalization evident in the trajectory of global governance evolved

because the powers that be were in heavy contention with one another for

geopolitical power and for economic resources, but also because resistance

emerged within the polities of the core and in the regions of the non-core. The

series of hegemonies, waves of colonial expansion and decolonization and the

emergence of a proto-world-state occurred as the global elites contended with

one another in a context in which they had to contain strong resistance from

below. We have already mentioned the waves of decolonization. Other important

forces of resistance were slave revolts, the labor movement, the extension of

citizenship to men of no property, the women’s movement, and other associated

rebellions and social movements.

These movements affected the

evolution of global governance in part because the rebellions often clustered

together in time, forming what have been called “world revolutions” (Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein

1989).[1]

The Protestant Reformation in Europe was an early instance that played a huge

role in the rise of the Dutch hegemony.

The French Revolution of 1789 was linked in time with the American and

Haitian revolts. The 1848 rebellion in Europe was both synchronous with the

Taiping Rebellion in China and was linked with it by the diffusion of ideas, as

it was also linked with the emergent Christian Sects in the United States. 1917

was the year of the Bolsheviks in Russia, but also the Chinese Nationalist

revolt, the Mexican revolution, the Arab Revolt and the General Strike in

Seattle led by the Industrial Workers of the World in the United States. 1968

was a revolt of students in the U.S., Europe, Latin America and Red Guards in

China. 1989 was mainly in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, but important

lessons about the value of civil rights beyond justification for capitalist

democracy were learned by an emergent global civil society. The current world revolution of 20xx

(Chase-Dunn and Niemeyer 2009) is an important context for the questions about semiperipheral development and future likely outcomes that

are the main topics of this article.

The big idea here is that the

evolution of capitalism and of global governance is importantly a response to resistance and rebellions

from below. This has been true in the past and is likely to continue to be

true in the future. Boswell and Chase-Dunn (2000) contend that capitalism and

socialism have dialectically interacted with one another in a positive feedback

loop similar to a spiral. Labor and socialist movements were obviously a

reaction to capitalist industrialization, but also the U.S. hegemony and the

post-World War II global institutions were importantly spurred on by the World

Revolution of 1917 and the waves of decolonization. An important idea that

comes out of this theoretical perspective is that transformational changes tend

to be brought about by the actions of individuals and organizations within

polities that are semiperipheral relative to the

other polities in the same system. This is known as the hypothesis of semiperipheral development.

The idea

of the “semiperiphery” is a relational concept. Semiperipheral polities are in the middle of a

core/periphery hierarchy, but what that means depends on the nature of existing

organizations and institutions and the forms of interaction that exist within a

particular world-system. Semiperipheral marcher

chiefdoms are necessarily somewhat different from semiperipheral

marcher states and semiperipheral modern

nation-states. The evolutionary

world-systems perspective points to the similarities as the basis for the claim

that studying whole world-systems is necessary in order to explain

socio-cultural evolution. But this does not tell us what semiperipherality

is in any particular world-system. For that we have to know the nature of those

institutions that regulate interactions in the particular system. And

successfully playing the game of upward mobility that involves challenging the

core powers, moving up in the system and sometimes transforming the very nature

of the whole system, is an even more complicated matter involving innovation

and the implementation of new technologies, ideologies and forms of

organization. It is important to mention that not all semiperipheral

polities are agents of transformation. Some act to reproduce the institutions

that are predominant. But a semiperipheral location

is fertile ground for those who want to implement organizational, ideological

or technological changes that are transformative.

Some

observers have claimed that the world is now flat because of globalization. But

studies of global inequalities do not find a strong trend toward a flatter

world. Even with the rapid economic growth of China and India in the past few

decades, the global stratification system has not become significantly more

equal (Bornschier 2010). The large international

differences in levels of development and income that emerged during the

industrial revolution in the 19th century continue to be an

important feature of the global stratification system. Others have claimed that

globalization and “the peripheralization of the core”

evident in the migration of industrial production to semiperipheral

countries has eliminated the core/periphery hierarchy. Deindustrialization of

the core and the process of financialization have had

important impacts on the structure of core/periphery relations, but it is

surely an exaggeration to contend that the core/periphery hierarchy has

disappeared. Certainly U.S. economic hegemony is in decline and there are newly

arising challengers from the semiperiphery. But

recent upward and downward mobility has not appreciably reduced the overall

magnitude of inequalities in the world-system.

The

proponents of a global stage of capitalism have often focused on an allegedly

recent emergence of a transnational capitalist class. William Carroll’s (2010)

research shows how transnational interlocking directorates and political

networks have changed over the past several decades to link wealthy and

powerful families in Europe with those in North America and Japan. Though a few

individuals from semiperipheral countries have

managed to join the club, it remains mainly a network of big property owners

from core countries. William Robinson (2008) has also focused attention on how

the conditions of workers and peasants have been transformed by capitalist

globalization, and he contends that a global class structure is emerging that

will have consequences for the future of class relations and world politics.

The

concepts of a transnational capitalist class and the further transnationalization of workers and peasants are important

ideas, and they may also be usefully employed to examine relations among elites

and masses in earlier centuries as well. There has always been a

world-system-wide class structure. Immanuel Wallerstein

(1974:86-87) analyzed the class structure of the Europe-centered world-system

of the long sixteenth century. Samir Amin (1980) explicitly studied the global

class structure before globalization became an important focus of study. In the centuries before the most recent wave

of globalization there have been several important efforts by both capitalists

and workers to coordinate their actions internationally. The global class

system remains importantly impacted by the global North/South stratification

system despite greater awareness of global interactions and the strengthening

of transnational social movements.

Semiperipheral

development has sometimes, but not always, led to the attaining of core status

and hegemony in a core/periphery hierarchy and at other times it has only

contributed to the development and spreading of new forms of interaction that

eventually led to systemic transformation. These successful semiperipheral marcher states that produced large empires

by means of conquest were often also implementers of new “techniques of power”

that made larger systems more sustainable. The semiperipheral

capitalist city-states that accumulated wealth by means of production and trade

diffused commodity production to wide regions, providing incentives for subsistence

producers to also produce a surplus, and inventing writing and accounting

systems and forms of property and organization that sometimes diffused to the

commercializing tributary empires to which they were semiperipheral.

Some semiperipheral polities innovate

new technologies, ideologies or forms of organization, but new ideas also come

from core areas where there are bigger information network nodes and sometimes

from the periphery. But semiperipheral polities are

more likely to take the risk of investing resources in new techniques, ideas or

organizational forms regardless of their origins. They implement new stuff, while older core

polities get stuck in the old ways. What will be the systemic consequences of the

actions and developments of contemporary semiperipheral

peoples?

With

the emergent predominance of capitalism the relationship between core/periphery

relations and class structure changed. Now core polities tended to have less

inequality because a large middle class developed, producing a diamond-shaped

class structure ♦. Non-core

polities tended to have more inequality because a small

elite dominates and exploits a large mass of poor peasants and poor urban

residents, producing a pyramid-shaped class structure ▲. This stabilizes the system to some extent

because now core powers have greater internal stability than non-core powers.

But semiperipheral development continued because

economic development was still uneven. The relationship between class structure

and the core/periphery hierarchy continues to be important. Now the

core/periphery hierarchy crosscuts the class structures within polities. In the

core a relative harmony of classes is based on having a larger middle class and

on the ability of core elites to reward subalterns with the returns to

imperialism. In the periphery class conflict is also undercut by the

core/periphery hierarchy to some extent, because some elites side with the

masses against colonialism and neo-colonialism. But in the modern semiperiphery class conflict is not suppressed by the

core/periphery hierarchy. On the contrary, class conflict is exacerbated

because some elites have both the opportunity and the motive to adopt policies

such as economic nationalism that are intended to move the national economy up

the food chain of the global economy, while other elite factions prefer the

status quo. Movements supported by workers and peasants can more often find

allies among the elites. This explains why antisystemic

movements were able to attain state power in semiperipheral

Russia and China in the 20th century (Chase-Dunn 1998, Chapter 11).

The

Contemporary Core/Periphery Hierarchy

The social science literature on measuring the

relative positions of national societies in the larger core/periphery hierarchy

continues to be contentious. Is there really a single dimension that captures

most of important distinctions between national societies with regard to

economic, political, military and cultural power, or is the core/periphery

hierarchy multidimensional, and if so what are the most important dimensions?[2]

Arrighi and Drangel (1986)

argued that the semiperiphery is a discrete economic

stratum that is separated by empirical gaps from core and peripheral

zones. They contend that GNP per capita

is by itself an adequate measure of position in the world-system, and they find

empirical gaps in the distribution of national GNP per capita that are said to

be the boundaries between the core and the semiperiphery

and the semiperiphery and the periphery. Salvatore Babones (2005) also found these gaps in the international

distribution of levels of economic development (GNP per capita).

But another way to look at the core/periphery

hierarchy is as a multidimensional set of power hierarchies, that includes

economic, political and military power forming a continuous hierarchy that is a

relatively stable stratification hierarchy in the sense that most of national

societies stay in the same position over time, but that also experiences

occasional instances of upward and downward mobility? From this perspective the

labels of core, periphery and semiperiphery are just

convenient signifiers of relative overall position in a continuous hierarchy

rather than truly discrete categories. Semiperipherality

is just a rough appellation for those that are rather more in the middle of a

continuous distribution of positions.

There are likely to be important different ways to be semiperipheral depending on where a national society is on

the different hierarchical dimensions. And these differences may be related to

how a national society, or the movements that are based in these national

societies, behave in world politics. I contend that the question of cutting

points between allegedly discrete core, peripheral and semiperipheral

zones is largely a matter of convenience in what is, in the long run, a

continuous set of distributions of different kinds of power. In order to

produce a map that shows where the semiperipheral

countries are it is necessary to adopt cutting points, but it is not necessary

to claim that there are empirically discrete positions within the global

hierarchy.

Jeffrey Kentor’s

(2000, 2008) quantitative measure of the position of national societies in the

world-system remains the best continuous

measure because it includes

GNP per capita, military capability, and economic dominance/dependence (Kentor

2008). One may trichotomize Kentor’s

continuous indicator of world-system position into core, periphery and semiperipheral

categories in order to do research and to produce the kind of map shown in

Figure 3 below. The core category is nearly equivalent to the World Bank’s

“high income” classification, and is what most people mean by the term “Global

North.” The “Global South” is divided into two categories: the semiperiphery

and the periphery. The contemporary semiperiphery

includes large countries (e.g. Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil, India, China) and smaller countries with

middle levels of GNP per capita (e.g. Taiwan, South Korea, South Africa,

Israel, etc.).

Figure 1: The contemporary global hierarchy of national societies: core, semiperiphery and periphery (Bond 2013).

Figure 1 depicts the contemporary global hierarchy of

national societies divided into the three world-system zones. The core

countries are in red, the peripheral countries are yellow, and the semiperipheral

countries in the middle of the global hierarchy are orange. Several terms have been used in recent

popular and social science literatures that are approximately equivalent to

what we mean by the semiperiphery: Newly Industrializing Countries (NICS),

“emerging markets,” and most recently BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and

South Africa). In Figure 1 it is visually obvious that North America and Europe

are mostly core, Latin

America is mostly semiperipheral, Africa is mostly

peripheral and Asia is a mix of the three zones.

As we have said above, the evolutionary world-systems perspective contends that

semiperipheral

regions have been unusually fertile locations where social organizational forms

that transformed the scale and logic of world-systems have been implemented.

The hypothesis of semiperipheral development suggests

that close attention should be paid to events and developments within the semiperiphery,

especially the emergence of social movements and new kinds of national regimes.

The World

Social Forum (WSF) process is conceptually global in extent, but its entry upon

the world stage as an instrument of the New Global Left has come primarily from

semiperipheral

Brazil and India. The “Pink Tide” process in Latin America, led by Venezuelan

President Hugo Chavez, has been constituted by the emergence of both reformist

and antisystemic national regimes in fourteen out of

twenty-three Latin American countries since the Cuban Revolution (Chase-Dunn

and Morosin 2013). We want to pay special attention

to these kinds of phenomena and to their interaction with one another because

of the hypothesis of semiperipheral

development.

Wallerstein’s development of the concept of the semiperiphery has often implied that the main function of

having a stratum in the middle is to somewhat depolarize the larger system

analogously to a large middle class within a national society (e.g Wallerstein

1976). This functionalist tendency has

been elaborated in the notion of “subimperialism”

originally developed by Ruy Mauro Marini (1972) and

more recent discussed by Patrick Bond (2013) in his analysis of the BRICS. This approach focusses on the instances in

which semiperipheral polities have reinforced and

reproduced the existing global structures of power. Bond’s study of

post-apartheid South Africa’s “talk left, walk right” penchant is convincing.

But he may underestimate the extent to which the emergent BRICS coalition is

counter-hegemonic. The discussion of the need for an alternative to the U.S.

dollar in the global economy and the proposal for a new development bank for

the Global South have had unsettling effects on the powers-that-be in the core

states even if Bond makes little of these challenges. As we have said above, semiperipheral development is not carried out by all semiperipheral polities. It is undoubtedly the case that

the very existence of polities that are in between the extremes of the

core/periphery hierarchy tends to hide the polarization that is a fundamental

process in many world-systems. But the

fact that emerging powers are increasingly banding together and promulgating

policies that challenge the hegemony of the United States and the institutions

that have been produced by the European and Asian core powers indicates that semiperipheral challengers do not just reproduce the

existing global hierarchy. The question

for the New Global Left is how to encourage the potential for constructing a

more egalitarian world society. Bond is certainly right that the transnational

social movements need to push the BRICS to more effectively address the

fundamental problems of ecological crisis, global inequality and global

democracy.

The Challengers: Counter-hegemonic, reformist and antisystemic

There

are several different kinds of significant contemporary challengers to the

powers-that-be in the world-system. The question of reproduction vs.

transformation requires understanding the different kinds of challengers. Here we follow Jackie Smith and Dawn Weist (2012) in distinguishing between counter-hegemonic

movements, regimes and coalitions that opposed U.S. hegemony but are not

politically progressive (Iran, North Korea, Al Qaeda and the subimperialist actions of some of the BRICS). [3]

Among regimes, movements and

coalitions that are progressive we distinguish between those that are

reformists and those that are antisystemic. Our study of Latin American regimes

(Chase-Dunn and Morosin 2013) makes a distinction

between reformist regimes that have adopted some socially progressive policies

or taken some anti-neoliberal international positions and antisystemic

regimes such as most of the members of ALBA, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America. [4]

Smith and Weist (2012:10) define antisystemic as follows: ‘“Antisystemic

movements’ include a diverse ‘family of movements’ working to advance greater

democracy and equality (Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein 1989). According to Wallerstein,

‘to be antisystemic is to argue that neither liberty

nor equality is possible under the existing system and that both are possible

only in a transformed world’ (1990:36).”

Thus we have three categories for

organizing a discussion of challengers: counter-hegemonic, reformist and

anti-systemic. Some of the challengers

to global neoliberalism and the hegemony of the United States are not

progressive. Thus the New Global Left

must distinguish between its allies and those political actors that are deemed

to not be progressive. And among the

latter there may be some that can be worked with on a tactical basis or

convinced to pursue more progressive goals.

International geopolitics is a game

that state regimes need to play. The logic of “the enemy of my enemy is my

friend” is hard to escape when one is in charge of national defense. This is the main factor behind the phenomenon

of “strange bedfellows,” as when Hugo Chavez allied with Iran’s Mahmoud

Ahmadinejad or Syria’s Bashar al-Assad.

Regarding the hypothesis of semiperipheral development and the Pink Tide phenomenon in

Latin America, we found that both semiperipheral and

peripheral countries were equally likely to have moved toward either reformist

or antisystemic regime forms in the last few decades.

But when we examine the timing of these moves we find that semiperipheral

countries were more likely than peripheral countries to have made these changes

earlier (Chase-Dunn and Morosin 2013: Tables

2-4). Latin America as a whole has had

more of these progressive challenging regimes because there has been a regional

propinquity effect, and because it Latin American the non-core “backyard” of

the global hegemon (the United States).

Also Latin America is has a larger proportion of semiperipheral

countries than do other world regions.

It should also be noted that the

spread of the trappings of electoral democracy (polyarchy)

to the non-core has provided opportunities for progressive movements to

peacefully attain power in local and national state organizations. Salvador

Allende’s election in Chile was an example that was followed by the more recent

electoral victories of populists of various kinds in Latin America. The

imposition of draconian structural adjustment programs in Latin America in the

1980s and the rise neoliberal politicians who attacked labor unions and subsidies

for the urban poor led to a reaction in many countries in which populist

politicians were able to mobilize support from the expanded informal sector

workers in the megacities, leading in many cases to the emergence of reformist

and antisystemic national regimes.

The

establishment of relatively institutionalized electoral processes in most Latin

American countries and the failure of most leftist efforts to effectively

employ armed struggle encouraged the leaders of the World Social Forum process

to proscribe individuals who represent political groups that advocate armed

struggle from attending the WSF meeting as representatives of those groups.[5]

But all this should not lead us to suppose that violence and military power are

no longer important in politics. The fate of Allende and of the presidencies of

Jean Bertrand Aristide in Haiti remind us that death squads, the military, and

foreign intervention are still powerful factors in Latin American politics as

well as elsewhere.

The relationship between the progressive

national regimes and the progressive transnational social movements has been

contentious. Despite strong support from the Brazilian Workers Party and the

Lula regime in Brazil, the charter of the World Social Forum does not allow

people to attend the meetings as formal representatives of states. When Chavez and Lula tried to make

appearances at WSF meetings large numbers of movement activists protested. The horizontalists, autonomists and anarchists see those who

hold state power as the enemy even if they claim to be progressives. Exceptions have been made, as when European

autonomists provided support for Evo Morales’s

presidency in Bolivia (e.g. López and Iglesias Turrión, 2006).

The World Social Forum (WSF) process

has itself been a complicated dance toward global party formation and the

construction of a new global United or Popular Front (Amin 2007; Chase-Dunn and

Reese 2007). Its charter prohibits the

WSF itself from adopting a program or policy stances. The WSF is supposed to be an arena for the

grass roots movements to use to organize themselves and make alliances with one

another. In practice this has led to

competition among the movements and NGOs for hegemony within a hoped for

emergent New Global Left.

As

discussed below, studies of attendees at global World Social Forum meetings in

Porto Alegre, Brazil and Nairobi, Kenya reveal a multicentric network of overlapping movements, in which

four or five most central movements connect all the rest with one another

(Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro (2009). Up until 2011 the World Social Forum process

had little participation from the Middle East.

The Arab Spring revolts got the attention of activists, and in March of

2013 the World Social Forum was held in Tunis. The connection of the Arab Spring

revolts and continuing political contestation in Egypt with global

neoliberalism and austerity has been obscured by the struggle for national

democracy within the Middle Eastern countries and the rise of Islamist parties.

The

Network of Movements in the New Global Left

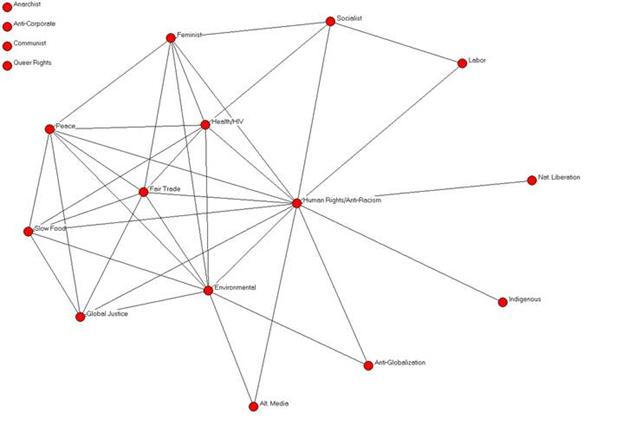

Survey research conducted at the meetings of

the World Social Forum in Porto

Alegre, Brazil in 2005 and Nairobi, Kenya in 2007

revealed a network of alliances among eighteen movement types based on the fact

that many individuals are active in more than one movement type (Chase-Dunn and

Kaneshiro 2009). Comparison of the WSF05 and WSF07

network figures showed that the basic multicentric

structure of the movement of movements did not change. In both networks there

was a set of hub movements that strongly integrate all the other

movements. As was the case for the WSF05

network, the matrix of movement pairs for the WSF07 meeting has no zeros,

meaning that all of the 18 movements have at least one participant in all of

the other movements. Only one of the forty-three anarchists was also actively

engaged in the slow food movement, the socialists and the feminists. But

there were no zeros and so all the movements were connected to other movements

by the fact that some individuals were active both of them.

Three of the movements (anarchist, communist and queer rights) that were

disconnected by the high bar of connectedness in the WSF05 matrix were also

disconnected in WSF07, whereas National Liberation met the test in Nairobi, but

not in Porto Alegre, and Anti-corporate failed the

test in Nairobi but not in Porto Alegre.. One of the same movements appears near the center (Human

Rights/Anti-racism), but some that were rather central in 2005 had moved out

toward the edge in 2007 (Peace, Global Justice and Alternative Media). The

Environmentalists were still toward the center, but not as central as they had

been in Porto Alegre. Health/HIV was much more

central than it had been in Brazil, probably reflecting both an increase in

global concern and a much larger crisis in Africa. Regarding overall structural

differences between the two matrices, the 2007 network was more centered around

a single movement (Human Rights/Anti-racism), but there were also more direct

connections among some of the movements out on the edge (e.g. feminists and

socialists, socialists and labor, slow food and global justice.

Figure 2: The network of movement

linkages at the 2007 WSF in Nairobi (Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro

2009)

Crisis of

What?

In earlier work Kirk Lawrence and I have

discussed three broad possible scenarios that depict in general terms what

might happen in the several decades (Chase-Dunn and Lawrence 2011; Lawrence

2012). We imagine the possibility of another round of U.S. hegemony in which the

United States reindustrializes based on its comparative advantages in new lead

high technology industries and provides global order that accommodates rising

powers and challenging social movements.

We concluded that this scenario was unlikely to come about because of

the continuing political stalemate within the U.S. and growing resistance to

U.S. unilateral use of military power. The illegal use of drones to murder

civilians in Pakistan and elsewhere confirms that the Obama administration has

continued the illegitimate unilateral use of military power begun by the Bush

administration. This kind of imperial over-reach is a strong sign that the U.S.

hegemony is continuing to decline, substituting supremacy for hegemonic

leadership. So one thing that is clearly in crisis is U.S.

hegemony. And it is rather unlikely that this could be turned around.

All earlier hegemonic declines led to periods of disorder and then to what Arrighi (1994) called new systemic cycles of capitalist

accumulation.

Kirk Lawrence and I also

contemplated the possible emergence of a democratic world government that would

coordinate collectively rational responses to population pressure, global

climate change and ecological degradation, global inequality and rivalries

among national states and transnational social movements. We see this as a

possible outcome that might be brought about if progressive transnational

social movements could form a powerful coalition and could work with

progressive national regimes in the Global South to democratize global

governance and to organize a legitimate authority with the capacity to help

resolve the great crises of the 21st century. This next phase could either take the form of

another systemic cycle of capitalist accumulation, perhaps based on a globalized

form of Keynesianism, or it might involve a qualitative transformation to a new

type of world society based on forms of socialism.

And

we also contemplated “collapse” in which continuing U.S. hegemonic decline,

rising challenges from the BRICS, a contentious multilateralism among

contenders for global predominance, conflictive action by both progressive and

regressive transnational social movements lead to high levels of conflict that

prevent coordinated responses to the emergent crises. This scenario could be

much like what happened in the first half of the 20th century, or it

could be worse because of the potential for huge destruction caused by more

lethal weapons and because of the more globalized extent of ecological

degradation. This is may be the most

likely scenario. But the other paths are not yet completely impossible for the

next few decades.

Giovanni

Arrighi (2007), in his last book, Adam Smith in Beijing, discussed the

possible emergence of another systemic cycle of capitalist accumulation that

would be less warlike and exploitative than the kind of capitalism that emerged

with the rise of the Europe-centered world-system. Arrighi

saw the rise of China as providing a model of “market society” in which the

power of finance capital is balanced by the strength of technocrats who are

able to implement development projects that are kinder to labor and less driven

by the military industrial complex. China is not large enough economically,

despite its immense number of people, to become the next hegemon. And, as Arrighi carefully explains, the current regime in Beijing

has made great efforts to avoid any discourse about hegemonic rise and global

leadership. He persuasively contends that the current Chinese leadership just

wants a level playing field upon which China can develop its economic

potential. These leaders are also quite sensitive and resentful of criticism

from the West about the nature of their political institutions. Arrighi, Andre Gunder Frank

(1998) and many other academics in the West have accurately recognized the

pervasive nature of Eurocentrism. Our lack of

knowledge about East Asian history has facilitated negative images of East

Asian backwardness, including the Marxian notion of “the Asiatic Mode of

Production” and these have served well as justifications for colonialism and

intervention. And anti-communism has also served these purposes.

The

obvious need of Western political leaders for a bogeyman (now that Osama Bin

Laden has been dispatched) understandably makes the current Chinese leadership

nervous. The Chinese leaders are well aware that the racist imagery of the

Yellow Peril and China-bashing might again serve the agenda of Western

political leaders looking for a scapegoat for current or future catastrophes.

This

said, the New Global Left (Santos 2006) needs a good

analysis of the possible helpful, or not so helpful, roles that the Chinese

people and current and future Chinese governments might play in the coming

decades. Arrighi’s analysis implies that the

Chinese development path provides a useful example for the rest of the world,

and that the rise of China may help the rest of the world to reduce global

inequalities and to move toward a more sustainable and just form of political

economy.

Arrighi contends that contemporary China is

pursuing a model of market society that is similar in many ways to the

paternalistic commodifying “natural” path that Adam

Smith saw in earlier centuries. Arrighi’s contention

that China has not yet developed full-blown capitalism is largely based on

Samir Amin’s observation that the rural peasantry has not yet been dispossessed

of land and so full proletarianization has not

emerged. The continued existence of the household registration system that the

Chinese Communist Party uses to try to regulate rural to urban migration also

guarantees rural residents access to farmable land (means of production).

One

may wonder whether or not dispossession of land is still a requisite of

capitalism in the age of flexible accumulation and outsourcing. Mike Davis

(2005:97-100) tells the story of the Bangkok-based Charoen Pokphand Company

(CP), a large-scale poultry producer who brought Tyson-style (American)

industrialized chicken production (the “Livestock Revolution”) first to

Thailand and then to China. Davis (2005:99) quotes Isabelle Delforge

as saying “With contract farming, large companies control the whole production

process: they lend money to farmers, they sell them chicks, feed and medicine, and they have the right to buy the whole

production. But usually the company is not committed to buy the chickens if the

demand is low. Contract farmers bear all the risks related to production and

become extremely dependent on demand from the world market. They become factory

workers in their own field.” Davis reports that, after starting in Shenzen, CP has built more than one hundred feed mills and

poultry-processing plants throughout China. This all sounds rather like

capitalism despite that farmers have not been dispossessed of their land.

Arrighi also implied that the current Chinese

regime is relatively environment-friendly. Others contend that this was indeed

the case in traditional China, but not of the Communist regime. The Chinese

Communist Party’s (CCP) embrace of the family-owned automobile for the masses

could have at least required California-style catalytic-converters fifteen

years ago, a proven technology for reducing auto emissions that would not have

added much to the cost of each car. Instead Chinese cities are choking on

automobile exhaust fumes. Decisions like that are both bad for the

environment and for the human population. Regarding greenhouse gas emissions,

Global South activists such as Walden Bello (2012) contends that China must be

included among the countries that should undertake rapid reduction in

emissions.

It

would seem logical that Arrighi’s depiction of

Chinese “market society” as a more sustainable and labor-friendly form of

society than that of the capitalist West implies that other nations should

emulate the Chinese model in order to deal with the issues of inequality and

environmental degradation that capitalist globalization has presented us with

in the 21st century. But Arrighi (personal

communication) denied that he was saying this. He pointed out that the

historical conditions that produced the institutional complexes and culture of

China today are impossible to replicate, and also that the world does not need

one model, but rather many approaches. And yet it is important to ask whether

or not the institutional elements that Arrighi found

in China are of use elsewhere in the efforts to construct more humane and

sustainable national societies and a democratic and egalitarian world society. [6]

The notion that China may be an exemplar of

contemporary egalitarianism in relations with the periphery would seem to be

contradicted by the situation in Tibet and by the reports of many observers of

Chinese projects in Africa. Progressive world citizens should not condone

China-bashing, and I agree with Arrighi

that China is, and is likely to continue to be, a somewhat more progressive

force in world politics than many other powerful actors. But what does the

Chinese model of market society imply for those who are looking for progressive

alternatives to global capitalism?

Arrighi’s (2007) effort to tease out the

combination of economic and political institutional forms that make the

difference between better and worse forms of modernity is a valuable start, but

needs to be further developed. The contemporary global justice movement that

perceives a “democratic deficit” in the existing institutions of global

governance and in many forms of representative democracy that exist within core

states is not likely to find much worth emulating in the paternalistic Confucianist state that the CCP regime seems to be

embracing. At the 2008 opening ceremony to the Beijing

Olympic Games Confucian harmony had erased all vestiges of the Chinese

Revolution except the red flag. Mao was gone. The class struggle was gone. The

heroic workers and peasants were gone. And so was the Red Detachment of Women.

The representation of modern China to the world was a vision of social harmony,

technological achievements of the traditional past, openness to the world, and

precise, large-scale drumming and tai chi. It was Confucian

harmony and the paternalism of the “grandfather state” devoid of any

alternative version of legitimate authority except national pride.

The

issue of democracy cannot be brushed aside as only a manifestation of

Eurocentric ignorance. It is unfortunate that the neoliberals and the

neoconservatives have used the discourse about representative democracy and

human rights to badger the Chinese regime, but this will not make the democracy

problem go away for the New Global Left.

And

the issue of institutional forms of property also badly needs to be addressed.

The CCP is promoting the rapid expansion of private property in the major means

of production and the reorganization of state-owned firms. But private and/or

state ownership of large firms are not the only options. Investment

decisions in large-scale undertakings could be shaped by market mechanisms,

thus allocating capital to firms that are productive and efficient, while

profits are distributed to all adult citizens (Roemer 1994). The role of the

state in this kind of market socialism is to redistribute shares to each

individual at the age of adulthood and to incentivize the protection of the

environment. In Eastern Europe most of the post-1989 experiments in

public ownership were carried out in the context of “shock therapy” in which

neoliberal economists engineered a transition from former state-led and

centrally planned economies to capitalism. Citizens were issued coupons, which

were then rapidly bought up by a new class of capitalists (usually former party

apparatchiks), thus proving that this kind of market socialism does not work.

But a country like China could carry out experiments with real market socialism

in which the whole public benefits from the profits of large firms while at the

same time using market mechanisms to allocate both capital and labor. That

would be a kind of market society worth emulating.

Both a new stage of capitalism and a

qualitative systemic transformation to some form of socialism are possible

within the next several decades, but a new systemic cycle of capitalism is

probably more likely. Capitalism has only been a predominant mode of production

for about five centuries. It is still young. The kinship and tributary modes

lasted much longer.

The

progressive evolution of global governance has occurred in the past when

enlightened conservatives implemented the demands of an earlier world

revolution in order to reduce strong pressures from below that were being

brought to bear in a current world revolution. The most likely outcome of the

current conjuncture may a global form of Keynesianism in which enlightened

conservatives in the global elite form a more legitimate, capable and

democratic set of global governance institutions to deal with the problems of

the 21st century.[7] If the trajectory of U.S. hegemonic decline

is slow and episodic, as it has been up to now, and if financial and ecological

crises are spread out in time and if conflicts within and between nation-states

are moderate and spread out in time, then the enlightened conservatives will

have a chance to produce a reformed world order that is still capitalist but

that meets the current challenges at least partially. But if the perfect storm

of global calamities should all come together in a short period of time (a

single decade), even though there would be a heavy price to pay and it would

fall mainly on the world’s poor, the progressive movements and the progressive

non-core regimes would then have a chance to radically change the mode of

accumulation to a form of democratic global socialism.

References

Amin,

Samir 1980 “The class structure of the contemporary imperialist system.” Monthly

Review

31,8:9-26.

__________2007

“Towards the fifth international?” Pp. 123-143 in Katarina Sehm-

Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Global Political Parties.

London: Zed Press.

_______ 2013 “Six Decades of Development Debate” 25 and 26 April at SOAS, University of London http://www.historicalmaterialism.org/news/distributed/samir-amin-six-decades-of-development-debate

Appelbaum, Richard P. and William I. Robinson (eds.) 2004 Critical

Globalization Studies. NY:

Routledge

Arrighi, Giovanni (ed.)

1985 Semiperipheral Development: The Politics of Southern

Europe in the Twentieth

Century Beverly Hills: Sage.

______________1994

The Long Twentieth Century London: Verso.

______________ 2006 Adam Smith in Beijing. London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K.

Hopkins, and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic

Movements. London: Verso

Arrighi, Giovanni and Jessica Drangel 1986 “The stratification of the world-economy: an

exploration

of the semiperipheral zone”Review 10,1: 9-74.

Babones, Salvatore J. 2005 "The

Country-Level Income Structure of the World-Economy." Journal

of World-Systems Research 11:29-55.

Bello, Walden 2012 “The China Question in the Climate Negotiations: A Developing Country

Perspective”

http://lists.fahamu.org/pipermail/debate-list/2012-September/032039.html

Boatca, Manuela 2006 “Semiperipheries in the World-System: Reflecting Eastern

European and

Latin American Experiences” Journal

of World-Systems Research, 12,1: 321-346.

Bond,

Patrick 2013 “Subimperialism as lubricant of

neoliberalism: South African ‘deputy

sheriff’

duty within

BRICS” Paper

to be presented at the Santa Barbara

Global Studies Conference

session on "Rising Powers: Reproduction or

Transformation?" February

22 – 23, 2013

see also http://www.zcommunications.org/south-africa-s-sub-imperial-seductions-by-patrick-bond

Bornschier, Volker. 2010. “On

the evolution of inequality in the world system” Pp. 39–64

in Christian Suter

(ed.)

Inequality Beyond Globalization: Economic Changes. Social

Transformations and the Dynamics of

Inequality. Berlin: World Society

Studies.

Boswell, Terry and Christopher

Chase-Dunn. 2000 The Spiral of

Capitalism and Socialism: Toward Global

Democracy.

Boulder, CO.: Lynne Rienner.

Carroll, William K.

2010 The Making of a Transnational

Capitalist Class. London: Zed Press.

Castañeda, Jorge G. 2006. “Latin

America’s Left Turn.” Foreign Affairs 85(3):28-43.

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1988. "Comparing world-systems: Toward a

theory of semiperipheral

development,"

Comparative Civilizations Review, 19:29-66, Fall.

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1980.

"The development

of core capitalism in the antebellum United States: tariff politics and class

struggle in an upwardly mobile semiperiphery"

in Albert J. Bergesen

(ed.) Studies of the Modern World-System. New York: Academic Press.

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1990 "Resistance to imperialism: semiperipheral

actors," Review, 13,1:1-31 (Winter).

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1998 Global Formation: Structures of

the World-Economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman and

Littlefield

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Thomas D. Hall 1995 "Cross-world-system comparisons: similarities

and

differences,"

Pp. 109-135 in Stephen Sanderson (ed.) Civilizations and World Systems

Studying

World-Historical

Change.

Walnut Creek, CA.: Altamira Press

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Kelly M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and Their

Neighbors. Tucson: University of

Arizona Press.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and E.N. Anderson (eds.) 2005. The Historical Evolution of World-Systems. London:

Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn, C. , Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis

Alvarez and Thomas D. Hall. 2006 “Waves of

Globalization and Semiperipheral

Development in the Ancient Mesopotamian and

Egyptian World-Systems” Pp. 114-138 in Barry Gills and

William R. Thompson (eds.),

Globalization and Global History London: Routledge.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Ellen Reese 2007 “The World Social Forum: a global party in the making?” Pp. 53-92 in Katrina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Global Political Parties, London: Zed Press.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Matheu

Kaneshiro

2009 “Stability and Change in the contours of Alliances

Among movements in the social forum process”

Pp. 119-133 in David Fasenfest (ed.)

Engaging Social Justice. Leiden:

Brill.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Terry Boswell

2009 “Semiperipheral devolopment and global democracy” PP

213-232

in Owen Worth and Phoebe Moore, Globalization

and the “New” Semiperipheries,

Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn, C. and R.E. Niemeyer 2009

“The world revolution of 20xx” in Mathias Albert, Gesa

Bluhm, Han

Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational Political Spaces.

Campus Verlag:

Frankfurt/New York

Chase-Dunn, C. and Kirk Lawrence 2011 “The Next Three

Futures, Part One: Looming Crises of

Global Inequality, Ecological Degradation,

and a Failed System of Global Governance”

Global Society 25,2:137-153 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows47/irows47.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Hiroko Inoue 2012 “Accelerating democratic

global state formation”

Cooperation and Conflict 47(2) 157–175. http://cac.sagepub.com/content/47/2/157

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Bruce Lerro

2013 Social Change: Globalization from the Stone Age to the Present.

Boulder, CO: Paradigm

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Alessandro Morosin 2013 “Latin America in the World-System: World

Revolutions and Semiperipheral Development.” Paper presented at the Santa Barbara

Global

Studies Conference February 22 – 23

Chase-Dunn, C.

and Anthony Roberts 2012 “The structural crisis of global capitalism and the

prospects for world

revolution in the 21st century” International

Review of Modern Sociology 38,2:

259-286 (Autumn) (Special Issue on The Global Capitalist Crisis and

its Aftermath edited by

Berch Berberoglu)

Davis, Mike 2005 The Monster At Our Door: The Global

Threat of Avian Flu. New York: New Press

Durand, Cliff and Steve Martinot (eds.) 2012 Recreating

Democracy in a Globalized State. Atlanta: Clarity

Press.

Frank, Andre Gunder 1998 Reorient:

Global Economy in the Asian Age. Berkeley, CA.:

University of

California Press.

Graeber,

David 2013 The Democracy Project. New York: Spiegel

and Grau

Hall, Thomas D. and C. Chase-Dunn 2006 “Global social

change in the long run” Pp. 33-58 in C.

Chase-Dunn and S. Babones

(eds.) Global Social Change.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press.

Hamashita, Takeshi 2003

“Tribute and treaties: maritime Asia and treaty port networks in the era of

negotiations,

1800-1900” Pp. 17-50 in Giovanni Arrighi, Takeshi Hamashita and Mark

Selden (eds.) The Resurgence of East Asia. London: Routledge

Henige,

David P. 1970 Colonial Governors From

the Fifteenth Century to the Present. Madison, WI:

University of Wisconsin Press.

Hung, Ho-Fung (ed.) 2009 China and the Transformation of Global

Capitalism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Kentor,

Jeffrey. 2000. Kentor, Jeffrey.

Capital and Coercion: The Role of Economic and Military Power in the

World-Economy 1800-1990. New York: Routledge.

__________

2008 “The Divergence of Economic and Coercive Power in the

World Economy

1960 to

2000: A Measure of Nation-State Position” IROWS Working Paper #46

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows46/irows46.htm

Lawrence, Kirk 2009 “Toward a democratic and collectively

rational global commonwealth:

semiperipheral transformation in a

post-peak world-system” Pp. 198-212 in Owen Worth

and Phoebe Moore (eds.) Globalization

and the “New” Semiperipheries New York: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Levine, Mark 2013 “The revolution, back in black” Al-Jazeera Feb. 2

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/02/201322103219816676.html

Lindblom, Charles and Jose

Pedro Zuquete2010 The Struggle for the

World: Liberation Movements for the

21st Century. Palo Alto, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Marini, Ruy Mauro 1972 “Brazilian sub-imperialism” Monthly Review 23,9:14-24.

Martin,

William (ed.) 1990 Semiperipheral States in the World-Economy New York:

Greenwood.

Petras, James. 2010. “Latin

America’s Twenty First Century Capitalism and the US Empire.”

http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=22223

Radice, Hugo 2009 “Halfway to

Paradise?

Making Sense of the Semiperiphery” Pp 25-39 in Owen

Worth and Phoebe Moore, Globalization

and the “New” Semiperipheries, Palgrave.

Reese,

Ellen, Mark Herkenrath, Chris Chase-Dunn, Rebecca Giem, Erika Guttierrez, Linda

Kim,

and Christine Petit 2007 “North-South

Contradictions and Bridges at the World Social

Forum”

Pp. 341-366 in Rafael Reuveny and William R.Thompson (eds.) North and South in

the Global Political Economy. Cambridge, MA:

Blackwell. university Press).

___________,

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Kadambari Anantram,

Gary Coyne, Matheu Kaneshiro,

Ashley N. Koda, Roy

Kwon and Preeta Saxena 2008

“Research Note: Surveys of World

Social

Forum participants show influence of place and base in the global public

sphere”

Mobilization: An International Journal.

13,4:431-445.

Robinson, William I

1996 Promoting Polyarchy: Globalization, US

Intervention and Hegemony. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

——.

2008. Latin America and Globalization. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Unversity Press

——. 2010 “The crisis of global capitalism: cyclical, structural or systemic?” Pp. 289-310 in Martijn Konings

(ed.) The Great Credit Crash. London:Verso.

Roemer, John 1994. A Future for

Socialism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Santos,

Boaventura de Sousa 2006 The Rise of the Global

Left.

London: Zed Press.

Sen, Jai and Madhuresh Kumar with Patrick Bond and Peter Waterman 2007 A

Political Programme for

the World Social Forum?: Democracy,

Substance and Debate in the Bamako Appeal and the Global Justice

Movements. Indian Institute for

Critical Action : Centre in Movement (CACIM), New

Delhi,

India & the University of KwaZulu-Natal

Centre for Civil Society (CCS), Durban, South

Africa.

http://www.cacim.net/book/home.html

Smith,

Jackie and Dawn Weist 2012 Social Movements in the

World-System.

New York: Russell-Sage

Soros,

George 2000 Open Society: reforming global capitalism. New York: Public

Affairs

Wallerstein, Immanuel 1976 “Semiperipheral countries and the contemporary world crisis”

Theory

and Society 3,4:461-483.

_________________1984a “The three instances of hegemony in the history of the

capitalist

world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in

Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and Research

in

Macrosociology,

International Studies in

Sociology and Social Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

_________________ 1984b The politics of the world-economy

: the states, the movements, and

civilizations Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

________________ 2003 The Decline of American Power. New York: New

Press.

________________1990 “Antisystemic

Movements: History and Dilemmas.” In Transforming

the

Revolution: Social

Movements and the World-System, edited by Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi,

Andre

G. Frank, and Immanuel Wallerstein.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

_________________

2010

“Contradictions in the Latin American Left” Commentary

No. 287,

Aug. 15,

http://www.iwallerstein.com/contradictions-in-the-latin-american-left/

Worth,

Owen and Phoebe Moore (eds.) 2009 Globalization

and the “New” Semiperipheries. New

York: Palgrave MacMillan.