Periodizing the

Thought of

Andre

Gunder Frank:

From

Underdevelopment to

the

19th Century Asian Age

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute for Research

on World-Systems

University of

California-Riverside

draft v. 3/19/2015. 9158 words

An earlier version was presented at the annual meeting of

the International Studies Association, New Orleans, Feb. 19, 2015 This is IROWS Working Paper #88 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows88/irows88.htm

Abstract:

This paper reviews Andre Gunder Frank’s contributions

to our understanding of the modern world-system, the long-term evolution of

world-systems and the issues raised in Frank’s posthumous book about the Global

Nineteenth Century. Early, middle and late Frank’s are praised and critiqued

and those scholars who are continuing the Gunder

Project are supported and encouraged.

Andre

Gunder Frank’s legacy is wide and deep. He was one of

the founders of dependency theory and the world-systems perspective. He took

the idea of whole historical systems very seriously and his rereading of Adam

Smith inspired Giovanni Arrighi’s (2007) reevaluation

of the comparison of, and relations between, China and the West. This paper

reviews Frank’s contributions to our understanding of the modern world-system,

the long-term evolution of world-systems and some of the issues raised in his

posthumous book about the Global Nineteenth Century (Frank 2014). I divide

Frank’s thought into three periods (early, middle and late) in order to

explicate his ideas and to compare them with one another and with those of

other scholars.

All intellectuals change their

thinking as time passes. Some elaborate on their earlier ideas or pursue

directions that had occurred to them in earlier projects. Some make radical

changes that require retraining. Andre Gunder Frank

was unusual in the extent to which he sought to correct mistakes in his own

earlier work and was will to rethink basic assumptions. There are continuities

in his work to be sure. He was passionate about grand ideas as new ways of

looking at the world. He had a strong commitment in favor of the underdogs. He

was never afraid of confronting his own earlier ideas and he enjoyed

challenging taken-for-granted assumptions and myths. His detractors called him a gadfly and said

he “painted with broad strokes.” Broad strokes are often a good start down

paths that are hard to think.

Gunder was an early adopter and important diffuser of the

dependency perspective that emerged from Latin American social scientists in

the 1950s. His 1966 article "The Development of Underdevelopment"

(published in Monthly Review) was an important element in the Third Worldism that became an important element of Western

independent socialism after the Cuban Revolution. Marxist economists Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy were significant

contributors to this trend. The basic idea, which Frank held to the end, is

that the nature of social institutions and class relations in poor and

powerless countries are not primarily due to traditional local power structures

but that these institutions and class structures have been shaped by hundreds

of years of exposure to the powers of “the metropole”

(Gunder’s original term for the powerful core

countries). Colonialism and neo-colonialism have left what we now call the

Global South in a state of dependent underdevelopment. So the modernity/traditionalism

contrast was seen as a global socially constructed and reproduced stratified

power hierarchy.

Gunder soon came

into contact with other Third Worldists and, with

Samir Amin, Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi (all Africanists) he helped to formulate the emerging

world-system perspective. Frank’s research (Frank 1967, 1969, 1979b) showed

that Latin American societies were heavily shaped by colonialism and

neo-colonialism and argued that these dependent social formations should be

understood, not as feudalism, but as peripheral capitalism because they were a

necessary part of the larger capitalist world-system. The conceptualization of

capitalism as mode of accumulation that contained both wage labor (in the core)

and coerced labor (in the non-core) was elaborated by Frank and by the other

founders of the world-system perspective. Wallerstein

(1974) realized that serfdom had played a somewhat similar part in the peripheralization of Poland. Frank helped to formulate the idea that the

capitalist world-system was a single integrated whole and that it was a

systemically stratified system in which global inequality was reproduced and

the role of the non-core was an important and necessary part of the system.

This was a challenge to Marx’s definition of capitalism as necessarily

requiring wage labor and more orthodox Marxists accused Frank and the others of

“circulationism” because they seemed to focus on the

importance of trade between the core and the periphery rather than class

relations within each country. But the world-systems formulators explicitly

examined the global class structure as well as considering carefully the class

structures within countries (e.g. Amin 1980b).

Frank’s (1978)

examination of world history from 1492 to 1789 provided an insightful account

of the whole system and contributed to the reformulation of the study of

systemic modes of production by recasting them as modes of accumulation,

which included production, distribution and the different institutional ways in

which wealth and power were appropriated.

The Middle Frank: Ancient Hyperglobalism

Gunder

began to develop an interest in questions concerning the continuities and

discontinuities between the modern system of the last five centuries and

earlier periods. Other scholars were also doing this. Janet Abu-Lughod’s (1989) influential study examined a multicore

Eurasian system in the thirteenth century CE. Chase-Dunn and Hall published a

collection entitle Core/Periphery Relations in the Precapitalist

Worlds in 1991. Gunder began reading world

historians such as Philip Curtin and William H. McNeill. He developed an

important working partnership with Barry Gills in this period and together they

published the collection entitled The World System: Five Hundred Years or

Five Thousand? in 1993. Gills and

Frank argued, following Kasja Ekholm

and Jonathan Friedman (1982), that a “capital-imperialist” mode of accumulation

had emerged during the Bronze Age and that this system went through phases in

which state power was more important interspersed by phases in which markets

and private accumulation by wealthy families were more important. This mode of

accumulation had been continuous since the Bronze Age and so there was no

transition to capitalism in Europe. Already Gunder

had staked out this position in his 1989 Review article “Transitions and modes: in imaginary

Eurocentric Feudalism, Capitalism and Socialism, and the Real World System

History.” So capital imperialism had been continuous since the Bronze Age

emergence of cities and states. The emergence of capital imperialism was never

analyzed because it occurred before the emergence of cities and states in

Mesopotamia, which was the beginning of the Frank-Gills system of capital imperialism.

Frank and Gills also argued that there had been a single Afroeurasian

world system since the Bronze Age because neighboring societies share surpluses

and so are systemically linked with one another and if all indirect links are

counted there would be a single network of interaction. Frank also implied that

there will be no future transition to socialism.[1]

The capital-imperialist system is a great wheel that has gone around since the

Bronze Age and will continue into the future indefinitely.

Many

of Frank’s friends on the Left were very unhappy with this new analysis, but Gunder stuck to his guns, while continuing to critique

neo-colonialism and exploitation of the downtrodden. The new emphasis was on

the important continuities in the system, which were extended to the Americas

after 1492, creating a single global system. Frank also developed a fascination

with Central Asia in this period because of its long importance as a link

between the East and the West and the hybrid and innovative social formations

that emerged from there. In this he was a progenitor of a new (or renewed)

Central-Asia-Centrism that flourished after Frank’s affections moved on to East

Asia.

Janet Lippman Abu-Lughod’s important 1989 study of the multicentric

Eurasian world-systems of the l3th century CE was a very valuable and

inspiring contribution. Abu-Lughod helped to clear

the way forward in world-systems analysis by rejecting the idea of the ancient hyperglobalists that there has always been either a single

global (Earth-wide) system (Modelski 2003 and Lenski 2005) or a single Afroeurasian

system since the early Bronze Age (Frank and Gills 1993). Abu-Lughod agreed

with Wallerstein (1974) that as we go back in time

there were multiple regional whole

systems that should be studied separately and compared. Things would be

much simpler if it made sense to use the whole Earth as the unit of analysis

far back in time. The ancient hyperglobalists are

correct that there has been a either a single global network (or an Afroeurasian and American network) for millennia because

all human groups interact with their neighbors and so they are indirectly

connected with all others (though connections across the Bering Sea may have

been nearly non-existent for a period after the humans migrated from Central

Asia to the Americas). David Christian (2004: 213) contends that there have

been four “world zones” of information interaction (Afroeurasia,

America, Australia/Papua New Guinea and the Pacific) over the past 4000 years. But

all these claims about ancient macro-region interaction systems ignore the

issue of the fall-off of interaction

effects (Renfrew 1975 and below).

Frank and Gills (1993) contended that there had

been a single Afroeurasian system since the rise of

cities and states in Mesopotamia. But, if we read Frank and Gills as studying

the important continuities of the expanding West Asian/North African interstate

system and the Afroeurasian prestige goods network,

much of their analysis of core/periphery relations is quite valuable.

A Precontact North America-wide system?

Peter

Peregrine and Charles Lekson (2006, 2012) claim there

was a continent-wide American ‘oikumene’ that

extended to Honduras in Central America before the arrival of the Europeans.[2]

They contend that information spread quickly and cite several stories from

historian Herbert Eugene Bolton as evidence. The issue here is the spatial

scale of what Chase-Dunn and Hall (1996) have called the Information Network.

Information is exchanged, often in connection with trade, and this kind of

interaction is important for the diffusion of ideas and technologies. Though

information is lighter than other goods it is still subject to the frictions of

space, and so there is information fall-off and point in reached beyond which

no information travels.

Chase-Dunn and Hall have tended to assume that the Information Network is about

as big as the Prestige Good Network, but this is just a rough guess. Peregrine

and Lekson’s idea that information could rapidly

spread across the entire North American continent by means of foot

transportation and in a situation in which intelligible languages were rather

localized is somewhat far-fetched. We know that indigenous Americans developed

specialized trade languages for intergroup communication and there was regional

multilingualism that allowed information to move from group to group. But how

far and fast could information move?

Cora Alice Du Bois’s (1939) study of the

diffusion of the Ghost Dance cult from Western Nevada to Northern California

and Southern Oregon may help us get a handle on the issue of the spatial scale

of Information Networks. Du Bois interviewed people who had participated in and

observed the spread of the Ghost Dance cult. The 1870 Ghost Dance came from the

same area as the more famous 1890 Ghost Dance that inspired a Sioux uprising,

and the doctrine was very similar. The Indian dead were returning and all the

Europeans would disappear. As informants told Du Bois, this was a “hurry-up

word.” Doing a special dance would hasten the arrival of the formerly dead and

the emergence of the new world. This kind of millenarianism is familiar to

students of social movements and may have been an occasional feature of precontact indigenous social movements as well. It is hard

to sort out the autochthonous ideological elements from the borrowed aspects of

the Ghost Dance, and using it to estimate the geographical nature of precontact information systems has the same problem. By

1870 Indians in Nevada, California and Oregon had some access to roads, horses

and wagons, which they did not have before 1849 or so. These undoubtedly

extended their abilities to communicate with each other by making longer trips

easier. This said, the geography of the 1870 Ghost Dance was still rather

limited by several important factors. Language was one. Many Indian communities

had multilingual members, but the composition of these and their willingness to

aid the spread of the Ghost Dance doctrine were important determinants of where

the movement spread to and where it did not. Some communities, those that had

been less disrupted by the arrival of the Euroamericans,

were more resistant. The old “doctors” (spiritual specialists) in these did not

approve of the new ideas and were able to prevent the introduction or adoption

of the songs and dances in less disrupted regions. The Ghost Dance songs and

ideas were carried from their origin in Eastern Nevada by inspired individuals

who went abroad to tell the word. And the word was taken farther by new

recruits, who often modified the content and adapted it to local traditions.

From Walker Lake in Nevada, where the Ghost Dance emerged, to the farthest

point north in Southern Oregon is about 300 miles as the crow flies. The range

of a cult was probably less in precontact North

America, especially before the arrival of the horse. This is far from the

continent-wide oikumene posited by Peregrine and Lekson. But it does not exclude the possibility that ideas

and information can diffuse very long distances by passing from group to group,

nor that there may have been a occasional very long distance trip by an

individual or a small group. Such adventures would probably have been rare, but

they may account for the diffusion of “Southern Cult” artistic styles from

Mesoamerica that appeared during the decline of the Mississippian interaction

sphere. In any case, Gunder

Frank’s notion of connectedness is based on the transmission of “surplus,” not

the transmission of information or ideas. Physical goods containing human labor

are likely to be even more subject to the tyranny of distance than are ideas.

Modes of Accumulation and the East/West

Comparison

In

1989 Andre Gunder Frank wrote the first version of

his contention that “the modes of production” distinction made by Marxists is

just so much ideological nonsense (Frank 1989).[3]

He had discovered that something very like capitalism existed in the ancient

and classical worlds, and he had become quite skeptical about the idea of the

transition from feudalism to capitalism in Europe, which he increasingly saw as

a Eurocentric construction that ignored important larger Eurasian-wide

dynamics. Frank came to accept something close to Kasja

Ekholm and Jonathan Friedman’s (1982) notion of

“capital-imperialism” in which the world system had oscillated back and forth

between more state-organized and more market-organized conditions since the

emergence of cities and states in Mesopotamia. According to Frank’s view there

were no transitions from qualitatively different logics of social reproduction.

This view ignored what had happened before the emergence of states (the

so-called kin-based modes of production), and it minimized the idea of a long-term

trend in which large tributary states became increasingly commercialized as

they adopted and expanded the use of money and markets. Frank also largely

ignored what have been called “semiperipheral

capitalist city-states” in the ancient and classical worlds. And he completely

denied that Europe had experienced a transformation in which capitalism had

become the predominant mode of accumulation.

This conceptual move on Frank’s part

was arguably an over-reaction to some very important but not well-understood

insights – that markets, money, merchant capitalism, finance capitalism,

capitalist manufacturing and wage labor had played a much more important role

in the ancient and classical worlds than many others had recognized, and that

much of the Marxist version of the transformation of modes of production was

very Eurocentric. Furthermore, as did many others by 1989, Frank came to see

the Soviet Union more as a somewhat modernized and totalitarian version of

capital-imperialism than as an experiment in socialism. Frank’s response to

these insights was to completely throw out the idea that modes of accumulation

evolve. As with the contention that there had been a single Afroeurasian

world system since the Bronze Age, he may have over-reacted in order to make a

dramatic break with his own earlier thought and that of many others.

My

position is that there, indeed, have been major transformations in the modes of

accumulation. One reason both Frank, and to lesser extent Arrighi

(1994), missed this is that they started their histories well after states had

been invented. An anthropological framework of comparison recognizes that the

invention of the state was itself a major shift, marking the invention of the

tributary modes of accumulation. That this transition occurred independently

several times in human history indicates that it was part of a regular process

of socio-cultural evolution (Sanderson 1999; Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2014; Hall and Chase-Dunn 2006).

In

Rise and Demise, Chase-Dunn and Hall

characterized Rome and China as commercializing tributary empires in which

substantial amounts of marketization, commodity production and wage labor had

emerged, but the predominant logic of social reproduction remained based on the

appropriation of surplus product through the use of state power. Taxation,

tribute-gathering and rents from landed property were the mainstays of the

state and the ruling class. Paper money

was used in Sung China in the 10th century CE. But the state and the

ruling class of mandarins, or the marcher-state usurpers who sometimes came to

power, were mainly dependent on the use of state coercion to extract surplus

product from the direct producers. This is rather different from a capitalist

system in which profit-making and the appropriation of surplus value through

employment of wage labor has become the mainstay of the state and the ruling

class. China was commercialized, but the central state was still a tributary

state, not a capitalist state. A capitalist

state is controlled by capitalists and acts primarily in their interest, though

state power is sometimes used to also serve others who are allied with and

needed by the capitalists. Capitalist states existed in the ancient and

classical worlds, but they were out on the semiperipheral

edge, in the interstices between the tributary states and empires. Only in

Europe did a cluster of semiperipheral capitalist

city-states emerge, and then later a capitalist core state, the United

Provinces of the Netherlands in the seventeenth century.

In

Volume 1 of The Modern World-System

Immanuel Wallerstein (1974) noted a key difference

between China and the West that had huge consequences. He pointed out that

China had a central government -- single “world empire” that could make and

enforce a system-wide policy. Wallerstein pointed out

that at the same time that the Portuguese King Henry the Navigator was heading

out, with Genoese support, to circumnavigate Africa for the purposes of

outflanking the Venetian monopoly on East Indian spices, the Ming Dynasty was

abandoning the Treasure Fleet explorations to Africa and the West in order to

concentrate on defending the heartland of the middle kingdom from steppe

invaders. In Europe there was no central emperor to tell the Portuguese to

desist. Europe was developing a multicentric

interstate system in which finance capital was beginning to play and important

role in directing state policy (see Arrighi 1994),

while China was maintaining a relatively centralized tributary empire. Arguably

this was the most important difference between China and the West. It was the

weakness of tributary states in the West after the fall of Rome that allowed

capitalism to become a predominant form of accumulation, while the strong

tributary state in China, run by mandarins and semiperipheral

conquerors, repeatedly succeeded in confiscating the wealth of merchants who

posed a political threat to state control.

This

explanation was rejected as so much Eurocentric claptrap by Frank, because Max

Weber and Karl Marx had said as much, and they needed to be thrown into the

dustbin of Eurocentrism with all the other dead white guys. In Adam Smith in Beijing Giovanni Arrighi, reviews and recasts the recent work on Chinese

economic history that has been partly inspired by Gunder

Frank’s analysis (e.g. Bin Wong 1997; Kenneth Pomeranz

2000; Kaoru Sugihara 2003) These authors

show extensive markets, commodity production, buyer-driven commodity chains,

etc. in China and confirm that Chinese economic institutions in 1900 were not

inferior to those of the West. Arrighi (2007) ends up with the conclusion that the key

question is “who controls the state?” In Europe capitalists came to control,

first city-states, and then nation-states. In China that never happened, though

it may be happening now for the first time.

Giovanni

Arrighi’s Adam

Smith in Beijing is dedicated to Andre Gunder

Frank and Frank’s influence is obvious throughout. Arrighi

does not accept Frank’s blanket rejection of the distinction between the

tributary mode of accumulation and the capitalism mode of accumulation. In The Long Twentieth Century Arrighi describes China as having been a tributary state.

But in Adam Smith Arrighi

depicts China as having developed a more labor-intensive form of market society

that is less inhumane than the kind of capitalism that developed in the West.

Like Frank, Arrighi appears to have abandoned any

discussion of the possibility of a future transition to a qualitatively

different socialist mode of accumulation, though this is not explicitly

discussed. While Frank sees history as

great wheel that goes around and around between more state-organized and more

market-organized forms, Arrighi sees some possibility

of progress in the sense of a more egalitarian form of market society, with

China playing the role of exemplar and midwife.[4]

Both

Frank and Arrighi share the conviction that East Asia

is again rising to a central position, though Frank did not say as explicitly Arrighi has exactly what is meant by this. As reviewed

above, Frank argued that China had been the center of the Eurasian world-system

until the late eighteenth century and that then Europe had suddenly gotten the

upper hand, but that the European societies and their offshoots were now in

decline and China will be the center once again. In Adam Smith Arrighi is careful to avoid

saying that China will become the next global hegemon. Rather he sees China as

the exemplar of a better form of political economy – market society, and so the

world will become flatter (less unequal) to the extent that other countries

emulate the Chinese model of networked and state-led market society.

Arrighi contends that the kind of market society that is

said to be emerging in China is kinder and gentler to workers because it does

not replace labor with machines in such disruptive manor and it is less

destructive to the environment than Western capitalism because it does not

employ as large-scale methods of harvesting nature. It is also supposedly less

imperialistic. He contends that there

was an “industrious revolution” in China in the eighteenth century in which

intensive labor was used to produce commodities instead of replacing labor with

machines. This kind of market society was characterized by Mark Elvin (1973) as

a “high level equilibrium trap” in which capital had little incentive to invest

in labor-saving technology because labor was so cheap. Arrighi

emphasizes the upside of this for employment. He also contends that the Chinese

Revolution helped to create the conditions under which this kind of market

society could reemerge in the decades since Mao’s demise.[5]

Arrighi further contends that China was less imperialistic

than the West in earlier centuries, concentrating more on domestic development

than on global expansion. The East Asian PMN with China at its core was

somewhat less prone to interstate war than was the multicentric

European system of competing core states. Physical and human geography are also

relevant here. As John Fitzpatrick

(1992) first point out, despite a relatively great degree of centralization,

the East Asian system was still an interstate system that periodically broke

down into smaller warring states. These breakdowns were less frequent than the

nearly constant interstate wars of Europe, but this is probably due to the

preponderance of power held by the East Asian hegemon – China, than to any

difference in the modes of accumulation. An eight hundred pound gorilla can

keep the peace. The East Asian

trade-tribute system studied by Takeshi Hamashita

(2003) was a rather hierarchical form of international political economy,

though it was probably less rapacious than European colonialism. But again this

was at least partly due to the fact that the core was a single core-wide state

rather than a collection of competing core states.

The

notion that China concentrated only on domestic problems after the Ming

abandonment of the treasure fleets is contradicted by Peter Perdue’s (2005)

careful study of Qing expansion in Central Asia, and the notion that China is

an exemplar of contemporary egalitarianism in relations with the periphery is

contradicted by the situation in Tibet and by many observers of Chinese

projects in Africa (e.g. Bergesen 2014a). While we do

not condone China-bashing, and we agree with Arrighi

that China may be a somewhat more progressive force in world society than many

other powerful actors, the idea that adoption of the Chinese model of political

economy can be the main basis of a more egalitarian, just, and sustainable form

of global governance is a bit of a stretch. On the other hand there are

important elements of the idea of market society that probably are quite

relevant for a formulation of what should be the goals of contemporary

progressives, and that are possibly achievable during the twenty-first century.

The Late Frank: Sinocentrism

Gunder’s (1998) provocative study of the global

economy from 1400 to 1800 CE contended that China had been the center

of the global system since the Iron Age. Marx,

Weber and most other social scientist were hopelessly Eurocentric and this fatally

distorted their concepts and explanations of what had happened in world

history. The idea that capitalism arose in Europe is a myth. Capital imperialism had been the dominant

mode of accumulation since the early Bronze Age. Gunder contended

that the rise of European hegemony was a sudden and conjunctural development

caused by the late emergence in China of a “high level equilibrium trap” and

the success of Europeans in using bullion extracted from the Americas to buy

their way into Chinese technological, financial and production networks. Frank

contended that European hegemony was fragile from the start and will be

short-lived with a predicted new rise of Chinese predominance in the near

future. He also argued that the scholarly ignorance of the importance of China

invalidates all the social science theories that have mistakenly construed the

rise of the West and the differences between the East and the West. As I have

said above, in Frank’s view there never was a transition from feudalism to

capitalism that distinguished Europe from other regions of the world. He argued

that the basic dynamics of development were similar in the Afroeurasian

system for 5000 years (Frank and Gills 1993).

In ReOrient

Gunder forcefully argued that it is fundamental

and necessary to study the whole system

in order to look for continuities and transformations. He contended that the

most important way to do this is to look at multilateral trade, investment and

money flows. He argues correctly that very little quantitative research has

been done on the whole global system. When he reviews what has been done he finds that the

Rise of the West occurred much later than most thought and that it was due

mostly to the ability of the European states to extract resources from their

colonies. In the Global 19th Century the

gap that emerged between China and the West was smaller and shorter than most observers

knew. He contends that the rise of the West was short and insubstantial and the

global system is now returning to the China-centered structure that it has had

for most of the history of the world system.

Gunder’s

model of development emphasizes a combination of state expansion and

financial accumulation, although in Reorient he focused almost

exclusively on financial centrality as the major important element. His study

of global flows of specie, especially silver, importantly extends the work of

Flynn (1996) and others to expand our understanding of what happened between 1400

and 1800 CE. Frank also used demographic weight, and especially population

growth and the growth of cities, as indicators of relative importance and

developmental success (see also Morris 2010, 2013)

|

World Region |

City |

Population in thousands |

|

East Asia |

Nanjing |

1000 |

|

South Asia |

Vijayanagara |

400 |

|

West Asia-Africa |

Cairo |

360 |

|

Europe |

Paris |

280 |

|

East Asia |

Hangzhou |

235 |

|

America |

Tenochtitlán |

200 |

Table 1: World Largest cities in 1400 CE

Table 1 shows the sizes of six

largest cities on Earth in 1400 CE. Two of the six (Nanjing and Hangzhou) were

in China and Nanjing was the largest and much larger than the second largest,

which was Vijayanagara, the capital of a large empire

that emerged in the southern part of South Asia to resist Moslem incursions. So,

based on city sizes, Gunder is right that China was

the center at the beginning of the period studied in ReOrient.

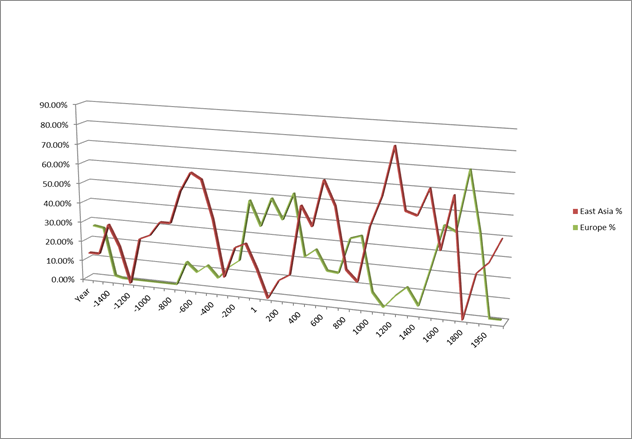

Figure 1: East Asian and European Urban Population as a % of the total population in the World’s 6 Largest Cities, 1500 BCE to CE 2010

Figure 1 shows the percentage of the total population in the world’s six largest cities held by cities in Europe and East Asia since 1500 BCE. Both regions rise and fall but the waves are not synchronous. Rather there is the sea-saw pattern noted by Morris and other observers. Europe had a rise that began during the late 3rd millennium and then crashed in the late 2nd millennium. East Asia had a rise that began in the late 2nd millennium BCE, crashed and then recovered and peaked in 500 BCE. East Asia has another rise in the middle of first millennium CE, a decline and then another rise during the first part of the 2nd millennium CE, a decline that ends in 1800 CE and then a recovery. Europe has a small recovery during the last centuries of the first millennium CE, a crash, and then a rise to a level higher than that of East Asia that peaks in 1850 and then a decline that is due to the rise of American cities as well as the recovery of cities in East Asia. Figure 1 indicates that in 1200CE Europe had no cities among the world’s six largest but then it began a long rise. It passed East Asia between 1800 and 1900, and then underwent a rapid decline in importance as indicated by the relative size of its largest cities.

For East Asia we see in Figure 1 a rise to the highest peak of all (80%) in 1300 CE. Not until 1900 was East Asia bested by the European cities after a rapid decline after 1800. The European cities were bested again by the East Asian cities between 1950 and 2000 during the rapid decline of the European cities in terms of their size-importance among the world’s largest cities. This most recent rise of the East Asian cities is a consequence of the upward mobility of Japan, China and the East Asian NICs in the global political economy.

The

trajectory of Europe displayed in Figure 1 supports part of Gunder Frank’s

(1998) analysis, but contradicts another part. The small cities of Europe in

the early period indicate its peripheral status vis a vis the core

regions of West Asia/North Africa, South Asia and East Asia. As Frank argues in

ReOrient, Europe did not best East Asia (as

indicated by city sizes) until the beginning of the 19th century.

But the long European rise, beginning in the thirteenth century, contradicts

Frank’s depiction of a sudden and conjunctural emergence of European hegemony.

Based on relative city sizes it appears that the rise of Europe occurred over a

period of 600 years. And

Frank’s contention that the European peak was relatively shallow is somewhat

contradicted by the height of the peak in 1900, which time European cities had

70% of the population of the world’s six largest cities.

Frank’s

ReOrient depiction of a sudden and

radical decline of China that began in 1800 CE is supported in Figure 1. His

analysis in ReOrient,

which focuses on the period from 1400 to 1800 CE, does not examine the relative

decline of East Asian predominance that began in 1300 CE.

This

examination of the problem of the relative importance of regions relies

exclusively on the population sizes of cities, a less than ideal indicator of

power and relative centrality.[6]

Nevertheless, these results suggest some possible problems with Andre Gunder

Frank’s (1998) characterization of the relationship between Europe and China

before and during the rise of European hegemony. Frank’s contention that Europe

was primarily a peripheral region relative to the core regions of the

Afroeurasian world-system is supported by the city data, with some

qualifications. Europe was, for millennia, a periphery of the large cities and

powerful empires of ancient Western Asian and North Africa. The Greek and Roman

cores were instances of semiperipheral marcher states that conquered important

parts of the older West Asian/North African core. After the decline of the

Western Roman Empire, the core shifted back toward the East and Europe was once

again a peripheral region relative to the Middle Eastern core.

Counter

to Frank’s contention, however, the rise of European hegemony was not a sudden

conjunctural event that was due solely to a late developmental crisis in China.

The city population size data indicate that an important renewed core formation

process had been emerging within Europe since at least the 13h

century. This was partly a consequence of European extraction of resources from

its own expanded periphery. But it was also likely due to the unusually

virulent forms of capitalist accumulation within Europe, and the effects of

this on the nature and actions of states. The development of European

capitalism began among the city-states of Italy and the Baltic. It spread to

the European interstate system, eventually resulting in the first capitalist

nation-state – the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century as well as the later

rise of the hegemony of the United Kingdom of Great Britain in the nineteenth

century.

This process of regional core formation and its associated emphasis on capitalist commodity production further spread and institutionalized the logic of capitalist accumulation by defeating the efforts of territorial empires (Hapsburgs, Napoleonic France) to return the expanding European core to a more tributary mode of accumulation.

Acknowledging

some of the unique qualities of the emerging European hegemony does not require

us to ignore the important continuities that also existed as well as the

consequential ways in which European developments were linked with processes

going on in the rest of the Afroeurasian (and then

global) world-system. The

recent reemergence of East Asian cities has occurred in a context that has been

structurally and developmentally distinct from the multi-core system that still

existed in 1800 CE. Now there is only one core because all core states are

directly interacting with one another. While the multi-core system prior to the

eighteenth century was undoubtedly systemically integrated to some extent by

long-distance trade, it was not as interdependent as the global world-system

has now become.

An

emerging new round of East Asian hegemony is by no means a certainty, as both

the United States and German-led Europe and India will be strong contenders in

the coming period of hegemonic rivalry (Bornschier and Chase-Dunn 1999;

Chase-Dunn et al 2005). In this

competition megacities may be more of a liability than an advantage because the

costs of these huge human agglomerations have continued to increase, while the

benefits have been somewhat diminished by the falling costs of transportation

and communication and the emergence of automated military technologies. Nevertheless

megacities will continue to be an indicator of predominance because societies

that can afford them will have demonstrated the ability to mobilize huge

resources.

The Last Frank: the Global 19th century Asian Age

The posthumous publication of Gunder’s

last book would have never happened without the Herculean work of Robert A. Denemark in converting a massive corpus of notes and drafts

into a coherent whole. The first chapter is a long list of debunked myths in

which everything you have ever heard about the 19th century is

declared to be bunk and alternative assertions are proclaimed. The bombastic

tone is classical Gunder. There are too many issues

to address here. Instead I will focus on what I see as the main contributions.

While Frank attacks some of what he

himself said in ReOrient regarding the

timing of the emergence of the gap between China and the West, the main thrust

is the same. The rise of the West was more recent and less in magnitude than

anyone thought. While there were some amazing technological developments,

mainly the invention of the steam engine, the continuities were more important

than the transformations. There were no Dutch or British hegemonies and the

so-called “industrial revolution” was a minor sideshow that did not much change

the structure of the global system.

England was never the workshop of the world. The cotton textile industry

was a brief blip that rapidly spread abroad. The point at which Britain eclipsed

China was either 1850 or 1870.

In

Frank and Gills (1993) it was asserted that the structure of the global system

stands on a “three legged stool”: ecological/economic, sociopolitical and

cultural-religious. But, as in ReOrient, Frank mainly concerns himself with the structure

of international trade. The newly ecological Gunder

is more evident in his discussion of the ways in which the reproduction of

the core/periphery hierarchy involved

the export of social and physical entropy from the core to the periphery. At

the same time he contends that the consequences of European imperialism in the

19th century were strongly resisted in many areas of the

non-core. He once again affirms that the

main cause of the rise of the West was based on its ability to exploit and

dominate and derive resources from colonized areas, especially India.

Gunder’s review of other scholars who claim to have analyzed the

global system in the 19th rightly points out that most of them do

not include China – more instances of

Eurocentrism. The main exception is the research on multilateral trade by Folke Hilgerdt published in 1942

and 1945. Gunder rightly observes that the structure

of the whole system cannot be well represented by focusing on bilateral

connections –determining the interactions between two countries -- because this

leaves out their relations with other countries. This is the same insight that

is correctly trumpeted by the advocates of formal network analyses of social

structures. Gunder also denigrates the use of

variable characteristics that indicate the relationships between a single

country and the rest of the world, such as indicators of trade openness that

show the ratio of the size of the national GDP to trade with the rest of world.

Frank lumps these in with the idea of bilateral connections, but they are

different. He is right to point out that a lot of information is lost in these

calculations. Instead he prefers what he calls multilateral structures, and in

practice he focuses on what he calls trade

triangles that examine the exchange relations among three countries. This

is an important methodological insight for studying the structure of the world

economy and Frank makes good use of it to support his claims about the lateness

and shallowness of the Rise of the West.

The Frank Project is part social science and part commitment to a more egalitarian world society. Several eminent scholars have stepped to the plate to carry the research that Gunder began in new directions. I have already mention Robert A. Denemark’s huge effort to produce the last of Gunder’s books. Barry Gills, Albert J. Bergesen, Sing Chew, Patrick Manning and now Peter Peregrine and Charles Lekson are taking Gunder’s ideas in different important directions. Related work was done by George Modelski and Gerhard Lenski who share(d) Gunder’s idea of a global human system extending back to the Bronze Age, and William R. Thompson did research and published with Frank on cycles in the Bronze Age. As for the emancipatory side, a

s Gunder would have said, la

luta continua (the struggle continues).

Bibliography

Abu-Lughod, Janet Lippman 1989. Before European Hegemony The World System

A.D. 1250-1350

New York: Oxford University Press.

Amin, Samir. 1980a. Class and Nation, Historically and in the Current Crisis. New York: Monthly Review Press.

_______1980b “The class structure of the contemporary imperialist system.” Monthly Review 31,8:9-26.

Anderson, E. N. and Christopher

Chase-Dunn “The Rise and Fall of Great Powers”

in Christopher Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) 2005. The Historical

Evolution of World-Systems. London: Palgrave.

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth Century. London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Takeshi

Hamashita, and Mark Selden 2003 The

Resurgence of East Asia :

500, 150 and 50 Year

Perspectives. London: Routledge

Arrighi, Giovanni. 2006. “Spatial and

other ‘fixes’ of historical capitalism” Pp. 201-212 in C., Chase-Dunn and

Salvatore Babones (eds.) Global Social Change:

Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

_____. 2007 Adam Smith in Beijing. London: Verso

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K. Hopkins

and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic Movements. London and New

York: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni

and Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos and

Governance in the Modern World-

System: Comparing Hegemonic Transitions. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota

Press.

Beaujard, Philippe. 2005 “The

Indian Ocean in Eurasian and African World-Systems Before

the Sixteenth

Century” Journal of World History 16,4:411-465.

_______________2010. “From Three possible Iron-Age

World-Systems to a Single Afro-

Eurasian

World-System.” Journal of World History

21:1(March):1-43.

Bergesen, Albert J. 2013 “The new surgical

imperialism: China, Africa and Oil” Pp. 300-318

in George Steinmetz (ed.) Sociology and Empire. Durham, NC: Duke

University Press.

_____________2014

“World-system theory after Andre Gunder Frank” A

paper to be

presented at the annual meeting of

the International Studies Association, New

Orleans, February 19.

Bergesen, Albert and Ronald Schoenberg 1980

“Long waves of colonial expansion and contraction 1415-1969” Pp. 231-278 in

Albert Bergesen (ed.) Studies of the Modern

World-System. New York: Academic Press.

Boli, John

and George M. Thomas (eds.) 1999 Constructing

world culture : international

nongovernmental

organizations since 1875 Stanford, Calif. : Stanford University Press.

Boswell, Terry

and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The

Spiral of Capitalism and

Socialism: Toward Global Democracy.

Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Bosworth,

Andrew 1995 "World cities and world economic cycles" Pp. 206-228 in

Stephen

Sanderson (ed. ) Civilizations and World Systems. Walnut Creek,CA.: Altamira.

Braudel, Fernand

1972 The Mediterranean and the

Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II.

New York:

Harper and Row, 2 vol.

_____________. 1984. The Perspective of the World, Volume 3

of Civilization and Capitalism.

Berkeley: University of California Press

Bunker, Stephen

and Paul Ciccantell. 2004. Globalization and the

Race for Resources. Baltimore,

MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chandler,

Tertius 1987 Four

Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census.

Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellon Press

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1988. "Comparing world-systems:

Toward a theory of semiperipheral

development," Comparative Civilizations Review, 19:29-66, Fall.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher 2008 “The

World Revolution of 20xx” Jerry Harris

(ed.) GSA Papers 2007: Contested

Terrains of Globalization.

Chicago: ChangeMaker.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and E.N.

Anderson (eds.) 2005. The Historical Evolution

of World-Systems. London: Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Salvatore Babones. 2007. Global

Social Change. Baltimore, MD:

Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Thomas D. Hall (eds.) 1991 Core/Periphery

Relations in the Precapitalist

Worlds. Boulder: Westview Press

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Bruce Lerro

2014 Social Change: Globalization from

the Stone Age

to the Present. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Boulder, CO.: Westview.

____________________________________ 2011“East and West in world-systems evolution” Pp.

97-119 in Patrick Manning and Barry K. Gills (eds.) Andre Gunder Frank and GlobalDevelopment, London: Routledge.

Chase-Dunn, C.

and Andrew K. Jorgenson, “Regions and Interaction Networks: an

institutional materialist

perspective,” 2003 International Journal of Comparative

Sociology 44,1:433-450.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 “Trade

globalization

since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system.”

American Sociological Review, February.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Susan Manning, 2002 "City systems and

world-systems: four millennia of city growth and decline," Cross-Cultural

Research 36, 4: 379-398 (November).

Chase-Dunn, Chris, Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence

and Hiroko Inoue 2011 “Last of the

hegemons:

U.S. decline and global governance” International Review of Modern

Sociology 37,1: 1-29 (Spring).

Chew, Sing C.

2001 World ecological degradation : accumulation, urbanization, and

deforestation, 3000

B.C.-A.D. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press

___________ 2007 The Recurring Dark Ages : ecological stress,

climate changes, and system

transformation Walnut Creek,

CA: Altamira Press

Christian, David 2004 Maps of Time:

An Introduction to Big History. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Curtin, Philip 1984 Crosscultural Trade in World History. Cambrdige:

Cambridge University Press.

Davis,

Mike 2001 Late Victorian Holocausts. London: Verso.

Du

Bois, Cora Alice 1939 The 1870 Ghost

Dance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ekholm, Kasja and

Jonathan Friedman 1982 “’Capital’ imperialism and exploitation in the

ancient world-systems” Review 6:1 (summer): 87-110.

Elvin, Mark.

1973. The Pattern of the Chinese Past.

Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Elvin, Mark

2004 The retreat of the elephants : an environmental

history of China. New Haven: Yale

University

Press.

Engels,

Frederic 1935 Socialism: Utopian and

Scientific. New York: International Publishers

Fagan, Brian 2004 The Long Summer. New York: Basic Books

Fitzpatrick, John. 1992. "The

Middle Kingdom, the Middle Sea, and the Geographical Pivot of History." Review XV, 3 (Summer): 477-521

Flynn,

Dennis O. 1996 World Silver and Monetary

History in the 16th and 17th Centuries.

Brookfield, VT: Variorum.

Frank,

Andre Gunder.

1966. "The Development of

Underdevelopment." Monthly Review September:17-31. [Republished in 1988, reprinted 1969 pp. 3-17

in Latin America: Underdevelopment or Revolution, edited by

A. G. Frank. New York: Monthly Review Press.]

_________________

1967 Capitalism

and underdevelopment in Latin America. New York: Monthly

Review Press.

Frank, Andre Gunder

1969 Latin America: Underdevelopment or revolution? New

York: Monthly Review Press

_________________1978 World Accumulation, 1492-1789 New York: Monthly Review Press.

__________________1979a: Dependent Accumulation and Underdevelopment New York:

Monthly Review Press

___________________1979b Mexican Agriculture 1521-1630:transformation

of the mode of production. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Frank, Andre Gunder.

1989. “Transitions and modes: in imaginary Eurocentric Feudalism, Capitalism

and Socialism, and the Real World System History.” Review 15:3(Summer):

335-72

Frank, Andre

Gunder. 1992. "The Centrality of Central Asia." Comparative Asian

Studies

Number 8.

Frank, Andre

Gunder 1998 Reorient: Global Economy in

the Asian Age. Berkeley, CA.:

University

of California Press.

_________________ 2014 Reorienting

the 19th Century: Global Economy in the Continuing Asian

Age. Edited and

with an Introduction by Robert A. Denemark. Boulder,

CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Frank,

Andre Gunder and Barry K. Gills (eds.) 1993 The World System: Five Hundred

Years or Five Thousand ? London: Routledge.

Friedman, Jonathan and Christopher

Chase-Dunn (eds.) 2005. Hegemonic Declines: Present and Past. Boulder,

CO.: Paradigm Press.

Gills, Barry K. 2001 Globalization and the Politics of Resistance.

New York: Palgrave

___________ and William R. Thompson 2006

Globalization and Global History.

London: Routledge.

Hall, Thomas D. 2001. 2001 "Chiefdoms, States, Cycling, and

World-Systems Evolution: A Review Essay." Journal of World-Systems

Research 7:1(Spring):91-100

_____. 2005. “Mongols in World-System

History.” Social Evolution & History 4:2(September): 89-118.

_____. 2006. “[Re] Periphalization,

[Re]Incorporation, Frontiers, and Nonstate Societies: Continuities and

Discontinuities in Globalization Processes.” Pp. 96-113 in Globalization and

Global History edited by Barry K. Gills and William R. Thompson. London:

Routledge.

Hall, Thomas D. and Christopher

Chase-Dunn. 2006. “Global Social Change in the Long Run.” Pp.33-58 in Global

Social Change: Comparative and Historical Perspectives, edited by

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Salvatore Babones. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hall, Thomas D., Christopher Chase-Dunn and Richard Niemeyer. 2009 “The Roles of Central Asian Middlemen and Marcher States in Afro-Eurasian World-System Synchrony.” Pp. 69-82 in The Rise of Asia and the Transformation of the World-System,

Political Economy of the World-System Annuals. Vol XXX, edited by Ganesh K. Trinchur. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Press.

Hamashita, Takeshi 2003 “Tribute and treaties:

maritime Asia and treat port networks in the era of negotiation, 1800-1900” Pp.

17-50 in Giovanni Arrighi, Takeshi Hamashita and Mark Selden (eds.) The Resurgence of East Asia: 500, 150 and 50 Year Perspectives.

London: Routledge.

Hui, Victoria Tin-Bor 2005 War and state Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hung, Ho-Fung 2001 “Maritime capitalism

in seventeenth-century China: the rise and fall of Koxinga in comparative

perspective” Irows Working Paper #72 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows72/irows72.htm

_____________2005 “Contentious peasants,

paternalist state and arrested capitalism in

China’s long eigthteenth

century” Pp. 155-173 in Chase-Dunn and

Anderson, The

Historical

Evolution of World-Systems.

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez,

Kirk Lawrence, Anthony Roberts, Eugene N Anderson and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2012 “Polity scale shifts in

world-systems since the Bronze Age: A comparative inventory of upsweeps and

collapses” International Journal of

Comparative Sociology http://cos.sagepub.com/content/53/3/210.full.pdf+html

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Eugene N. Anderson, Andrew Owen, Rebecca Álvarez, Kirk

Lawrence and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2015 “Urban

scale shifts since the Bronze

Age: upsweeps, collapses and semiperipheral development” Social Science History

Volume

39 number 2, Summer

Kradin, Nicholai. 2002.

“Nomadism, Evolution and World-Systems:

Pastoral Societies in Theories of Historical Development.” Journal

of World-Systems Research 8:3(Fall):368-388

Lattimore,

Owen. 1940. Inner

Asian Frontiers of China. New

York: American Geographical Society,

republished 1951, 2nd ed. Boston: Beacon

Press.

_____. 1980

"The Periphery as Locus of Innovations." Pp. 205-208 in Centre and Periphery: Spatial

Variation in Politics, edited by Jean Gottmann. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Martin, William

G. et al Forthcoming. Making Waves: Worldwide Social Movements,

1750-2005.

Boulder, CO: Paradigm

Mann, Michael.

1986. The Sources of Social Power, Volume 1:

A history of power from the beginning

to

A.D. 1760. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

McNeill,

William H. 1963 The Rise of the West.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press

McNeill, John

R. and William H. McNeill 2003 The Human Web. New York: Norton.

Modelski, George 2003 World Cities: –3000 to

2000. Washington, DC: Faros 2000

______________

Tessaleno Devezas and

William R. Thompson (eds.) 2008 Globalization

as

Evolutionary Process: Modeling

Global Change. London: Routledge

Modelski, George and William R. Thompson. 1996. Leading Sectors and

World Powers: The Coevolution of Global Politics and Economics. Columbia,

SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Morris,

Ian 2010 Why the West Rules—For Now. New York:

Farrer, Straus and Giroux

______

2013 The Measure of Civilization. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

_______

and Walter Scheidel (eds.) The Dynamics of Ancient Empires: State Power from Assyria to

Byzantium.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Peregrine, Peter N. and Stephen H. Lekson 2006 “Southeast, Southwest, Mexico:

Continental

Perspectives on Mississippian Polities” In Leadership and Polity in

Mississippian

Society. Brian M. Butler and Paul D. Welch, eds. Pp. 351-364.

Carbondale,

Southern Illinois University Press.

__________________________________2012

“The North American Oikoumene” In The

Oxford

Handbook of North American Archaeology. Timothy R. Pauketat,

ed. Pp.

64-72.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pomeranz, Kenneth 2000 The Great Divergence:

Europe, China and the Making of the Modern World

Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Renfrew, Colin 1975 “Trade as Action at

a Distance: Questions of Integration and

Communication”

In Ancient Civilization and Trade. Jeremy A. Sabloff

and C. C.

Lamberg-Karlovsky, eds. Pp. 3-59. vol. 3. Albuquerque:

University of New Mexico

Press.

Robinson,

William I 2004 A Theory of Global Capitalism. Baltimore: MD. Johns

Hopkins

University Press.

________________2015 “The

transnational state and the BRICS: a global capitalism perspective”

Third

World Quarterly, 36:1, 1-21 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.976012

Ross, Robert and Kent Trachte 1990 Global

Capitalism: The New Leviathan. Albany:

State

University of New York Press.

Sanderson,

Stephen K. 1990 Social Evolutionism. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Scheidel, Walter

2009 “From the “great convergence” to the “first great divergence”:

Roman and Qin-Han state formation”

Pp. 11-23 in Walter Scheidel (ed.) Rome and

China: Comparative Perspectives on

Ancient World Empires.

New York: Oxford University

Press.

Silver, Beverly 2003 Forces of Labor.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shannon,

Richard Thomas 1996 An Introduction to

the World-systems Perspective.

Boulder,

CO: Westview.

Sherratt, Andrew G. 1993a. "What Would a Bronze-Age World

System Look Like? Relations Between

Temperate Europe and the Mediterranean in Later Prehistory." Journal

of European Archaeology 1:2:1-57.

_____.

1993b. "Core, Periphery and

Margin: Perspectives on the Bronze

Age." Pp. 335-345 in Development and Decline in the Mediterranean

Bronze Age, edited by C. Mathers and S. Stoddart.

Sheffield: Sheffield Academic

Press.

_____.

1993c. "Who are You Calling Peripheral? Dependence and Independence in European

Prehistory." Pp. 245-255 in Trade and Exchange in Prehistoric Europe, edited by C. Scarre and F. Healy.

Oxford: Oxbow (Prehistoric

Society Monograph).

_____.

1993d. "The Growth of the Mediterranean Economy in the Early First

Millennium BC." World Archaeology 24:3:361-78.

Sugihara, Kaoru

2003 The East Asian path of economic

development: a long-term perspective”

Pp. 78-123 in Giovanni Arrighi, Takeshi Hamashita and Mark Selden (eds.) The Resurgence of East Asia: 500, 150 and 50 Year Perspectives.

London: Routledge.

Turchin,Peter 2011 . Strange Parallels: Patterns in

Eurasian Social Evolution . Journal

of

World Systems Research

17(2):538-552

Turchin, Peter, Jonathan M. Adams, and Thomas

D. 2006. “East-West Orientation of Historical Empires and Modern States.” Journal

of World-Systems Research.12:2(December):218-229.

Wagar, W. Warren 1992 A Short History of the Future.

Chicago; University of Chicago

Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel 2011 [1974] The Modern World-System, Volume 1.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wilkinson, David. 1987 "Central civilization" Comparative Civilizations Review 17:31-59 (Fall).

_____. 1991 “Core, peripheries and civilizations,” Pp. 113-166 in C. Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.) Core/Periphery Relations in Precapitalist Worlds. Boulder, CO: Westview Press http://www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/books/c-p/chap4.htm

Wilkinson,

Toby C., Susan Sherratt and John Bennet

2011 Interweaving Worlds: Systemic

Interactions in Eurasia, 7th to 1st Millennia BC.

Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Wohlforth, William C., Richard Little, Stuart J. Kaufman,

David Kang, Charles A Jones,

Victoria Tin-Bor

Hui, Arther Eckstein, Daniel Deudney

and William L Brenner 2007

“Testing balance of power theory in

world history” European Journal of

International

Relations 13,2: 155-185.

Wolf

, Eric 1997 Europe and the People Without History, Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Wong, R.

Bin 1997 China Transformed: Historical

Change and the Limits of European Experience. Ithaca: Cornell University

Press.