Global

state formation: modeling the rise, fall and upward sweeps of large polities in

world history and the global future

angkhor wat

Christopher

Chase-Dunn

Sociology, University of California-Riverside

Eugene N. Anderson

Anthropology, University of

California-Riverside

Peter Turchin

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of

Connecticut

v. 8/23/05

An

earlier version was submitted to the National Science Foundation’s Human and

Social Dynamics (research-focused project initiative,

subcontract to UCONN, collaborate with ESRI (Redlands).

NSF 05-520 Human and Social Dynamics http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2005/nsf05520/nsf05520.htm

Topical area: "agents of change" AOC

Designated as Full Research Proposal

Due to NSF February 23, 2005.

Start date: October 1, 2005.

36 months

Project Summary

Patterns of

expanding state formation constitute a long-term evolutionary trend that will

probably eventually result in the emergence of a single world state. The very

nature of the expansion of political integration has itself evolved because new

institutions that facilitate regional integration, cooperation and conflict

have emerged. Military conquest and the

long-term interaction between sedentary agrarian empires and confederations of

pastoral nomads came eventually to be replaced by a process of geopolitical and

economic competition among states in a world that has increasingly been

integrated by market exchange. In the last 200 years international governmental

and transnational non-governmental organizations have emerged that constitute

the first beginnings of world state formation, and the national states have

been partially reconfigured as instruments of an increasingly integrated global

elite. World state formation may be desirable because the problems created by

human technological and social change are increasingly global in scope. But a

world state will need to be legitimated in the eyes of a majority of the human

population of the Earth and this means that democracy must be constructed on a

global scale. This proposed project

will allow us to examine several probable future trajectories of global

political integration based on models of growth, decline and systemic

transformation that are developed by studying patterns of political integration

in several regions over the past 3000 years.

The main purpose of the

proposed project is to study and model the growth of states in selected regions

of the world over the past 3000 years. In the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries expansion and intensification of intercontinental interactions has

been called globalization. But earlier regional systems also exhibited similar

waves of “globalization,” albeit on a smaller spatial scale, and these waves of

network expansion and contraction, punctuated by occasional huge jumps in the

scale of networks, eventually led to the formation of the modern global social

system. This project will study the spatial nature of interaction networks over

time and the relationship between these networks and the growth decline/phases

of cities and states. The three-year project will develop, parameterize and

test models of social change using newly upgraded estimates of the sizes of

cities and states, climate change, trade routes, and warfare.

Intellectual Merit

The project will develop a new theoretical

synthesis based on Peter Turchin's (2003) model of the dynamics of agrarian

state growth and decline, network theory, a population pressure and ecological

model, and explanations of the rise and fall of modern hegemons. The

"agents of change" focus will test the hypothesis of “semiperipheral

development” – the idea that that it has mainly been semiperipheral societies

that have expanded networks, made larger states, and innovated and implemented

new techniques of power and new productive technologies that have transformed

the very logic of social change.

Broader Impacts

The

products of the project will help to inform scholars and policy-makers about

long-run patterns of historical social evolution and their implications for the

human future, especially world state formation. The World Historical Systems Time Map will be a spatio-temporal

web-enabled data set in a standardized interoperable format that will be useful

for scholars and students all over the world.

The elaboration of cooperative and coordinated global policies for

dealing with the emergent problems of the twenty-first century will be usefully

informed by understanding the probable trajectories of international political

integration.

Project Description

This project will study the spatial nature

of interaction networks over time and the relationship between these networks

and the growth decline/phases of cities and states. The three-year project will

develop, parameterize and test models of social change using newly upgraded

estimates of the sizes of cities and states, climate change, trade routes, and

warfare. The project will develop a new

theoretical synthesis based on Peter Turchin's (2003) model of the dynamics of

agrarian state growth and decline, network theory, a population pressure

iteration model and explanations of the rise and fall of modern hegemons. The

"agents of change" focus will test the hypothesis of “semiperipheral

development” – the idea that it has mainly been semiperipheral societies that

have expanded networks, made larger states, and innovated and implemented new

techniques of power and new productive technologies that have transformed the

very logic of social change. The elaboration of cooperative and coordinated global policies for

dealing with the emergent problems of the twenty-first century will be usefully

informed by understanding the probable trajectories of international political

integration.

Elements of the

Project

The

project will be led by a sociologist, and population ecologist and an

anthropologist. Its theoretical and empirical efforts combine demography and

integrative ecology with a world historical approach to human social evolution.

Thus it is truly interdisciplinary.

The

large temporal and spatial scope of this project is necessary to properly study

how the dynamics of human macrosystems have evolved. This project will focus on

building non-linear dynamic models, enhancing existing data, and testing the

models with sophisticated new methods for social network and spatio-temporal

analysis. The central intellectual merit of the project will be to develop

dynamical models of the rise and fall of states over the past 3000 years in

order to provide insights about the probable future trajectories of global

state formation. We will begin with a demographic and ecological model of the

growth and decline of land-based “tellurocratic” states followed by development

of a model of the growth of “thalassocratic” maritime capitalist city-states.

These models will then be combined to model the transition to the “modern”

pattern of the rise and fall of capitalist hegemonic nation-states. We will

also build and test a model of the interactions among world regions that can

account for the East/West synchrony of growth/decline phases of cities and

states discovered in earlier research. These models will help us to explain the

human past and will have important implications for the future of global

governance because the causes of past political expansion and of future state

formation will be modeled. Using city

and regional population sizes and the

territorial sizes of states and empires as the main indices

of civilizational rise and fall, the project will model the interacting effects of population

growth, environmental degradation, resource use, migration, and the growth and

decline of cities and empires. The project will also model the

interactions of regional systems with one another. Interregional trade,

warfare, incursions and disease vectors are important factors that have

affected social change in regional interaction networks.

The products of the project will help to inform scholars and

policy-makers about long-run patterns of historical social evolution allowing

them to better anticipate and confront problems of sustainability, global

inequality and social conflict that are likely to emerge in the 21st

century. The World Historical Systems

Time Map will be a spatio-temporal web-enabled data set in a standardized

interoperable format that will be useful for scholars and students of long-term

social change all over the world. The

educational products of the project will inform scholars and students about the

patterns of human social evolution and their interaction with natural systems.

The data resource development of this project will

focus on city and state sizes, trade routes and amounts, warfare, climate

change, and epidemic diseases, and the classification of states and nomadic

peoples as to their position in intersocietal hierarchies (core, periphery and

semiperiphery). Using a multiple indicator measurement error approach, the

project will estimate the values of important variables using proxy

indicators. The resultant data archive

will include information on all the large cities and states since 1000 BCE in

the targeted regions as well as data on climate change, trade, migration and

incursions, warfare and population size estimates.

The

analyses will use GIS, spatio-temporal statistical methods, network analyses

and structural equations modeling to test theoretical models. The temporal

framework of the project is 3000 years (from 1000 BCE to the present),

including the period of the agrarian empires and preindustrial cities as well

as the modern global system. The spatial focus is four regions in Afroeurasia

from 1000 BCE to 1500 CE, and then the whole globe over the past 500 years.

Prior NSF

Support

Christopher

Chase-Dunn: SES-0077975 "Trajectories and

Causes of Structural Globalization: 1800-2000" Amount: $129,898 PERIOD:

September 1, 2000 through August 31, 2002. Results:

Determined the trajectories of trade and investment globalization in the 19th

and 20th centuries to study the timing of waves of economic integration and to

compare the heights of the peaks. Publications: Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Yukio

Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 "Trade Globalization since 1795: waves of

integration in the world-system," American Sociological Review

65:77-95.

SES-0350819

“The Social Foundations of Global Conflict and

Cooperation: Waves of Globalization and

Global Elite Integration, 19th to 21st Century” (with

Thomas E. Reifer) Amount: $152,312

PERIOD: April 1, 2004 through May 31 31, 2006.

These projects are examining waves of global integration in the last two

centuries, whereas the current proposed project will study waves of regional

integration over the past 3000 years and will model the transition to the

modern international system, compare its dynamics with those of the agrarian

systems, and model several trajectories of probable future global state

formation.

Peter Turchin: IRCEB 0078130

"Building a Mechanistic Basis for Landscape Ecology of Ungulate

Populations." Amount: $2,834,494.

Period: September 1, 2000 through August 31, 2004. Results: Three papers have been already

published and a further 11 manuscripts have been submitted for publication.

E.N.

Anderson: Senior Advisor, DEB 0409984. Database award #

001626--002. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Engineered Crop Genes:

Natural and Human Constraints and Consequences. 9-1-2004 to 8-31-2008.

Macrosocial

Systems

Macrosocial

systems (or “world-systems”) are systems of societies that are strongly linked

to one another by interaction networks (trade, alliances, warfare, migration

and information flows). Thousands of years ago these were small regional

affairs, but they have gotten larger, merged with one another and the big ones

have engulfed smaller ones. This process of network expansions has eventuated

in the single global macrosocial system of today. One important meaning of the

globalization is the expansion and intensification of large-scale interaction

networks. At the same time that macrosystems have become spatially larger, the

societies and intersocietal systems that make them up have become more complex

and hierarchical. And the dynamics of systemic expansion may have qualitatively

changed as new institutions, especially markets and financial systems, have

emerged and become predominant.

The

patterns of expansion and incorporation can be traced by examining changes in

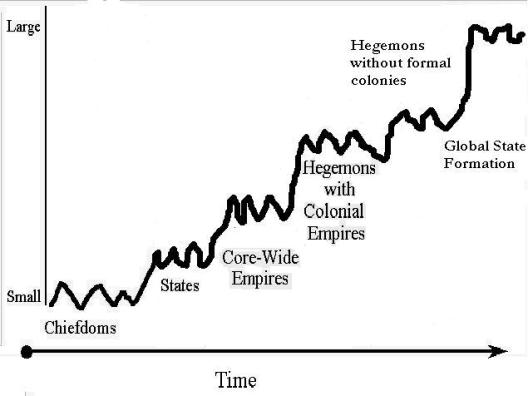

the spatial extent of interaction networks (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997). Figure 1 illustrates the spatiotemporal

history of the political/military network (PMN) that emerged first in

Mesopotamia 5000 years ago.

Figure

1: 5000 Year Emergence of the Central

System (adapted from Wilkinson 1987)

The processes of expansion and

increasing complexity have not produced a smooth upward trend in which the

originally less complex and hierarchical areas became increasingly more

complex. Rather social change has been characterized by uneven development in

both space and time. Original areas where leading edge developments have

emerged eventually lost out to new regions where unprecedented levels of

complexity and hierarchy developed. Temporal cycles of expansion and political

centralization were punctuated by occasional upward sweeps to new higher levels

– a stair-step pattern.

All hierarchical macrosystems, even

including those based on chiefdoms (Anderson 1994) and early states (Marcus 1998) experience

a sequence of the rise and fall of large polities – a cycle of

centralization and decentralization of political power. This is known in

state-based systems as the rise and fall of empires. In the modern macrosystem

of the last few centuries a similar (but also different) phenomenon can be seen

in the rise and fall of hegemonic core states such as Britain in the nineteenth

century and the United States in the twentieth century. Interaction networks also expand and

contract in a pattern that we can call pulsation. This expansion and

intensification of large interaction networks corresponds to one important

aspect of what is called “globalization” in the modern world-system. The recent wave of global trade and

investment integration since World War II was preceded by a globalization phase

during the last half of the nineteenth century that attained nearly the same

degree of worldwide connectedness (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer 2000).

These cyclical

processes (rise and fall; pulsation) must

be modeled in order to understand the more rare instances in which new

higher levels of integration and hierarchy have emerged. Both cities and

empires in Eastern and Western Asia have been found to grow and decline

synchronously from 500 BCE until 1500 CE, but South Asia did not follow this

pattern (Chase-Dunn, Manning and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and Manning 2002).

The four regional

intersocietal systems we propose to study before 1500 CE are: 1. West

Asia/Mediterranean; 2. East Asia; 3. South Asia; and 4. Central Asia. Except

for Central Asia we will focus on the settlement systems surrounding the

largest cities in each region. In Central Asia we will focus on cities and the

main areas inhabited by nomadic pastoralists. After 1500 CE we will study these

same regions plus Europe and the Americas.

The dynamics of agrarian states

The

primary resources in agrarian economies are land and people. Geopolitical

models, such as those developed by Randall Collins and Robert Hanneman (Collins 1995, Hanneman et al. 1995), postulate that state power is

directly related to the amount of territory and population that the state

controls. This functional dependence leads to positive-feedback dynamics: a

state that expands territory increases its power, which in turn enables it to

expand more, and so on (a classical example is the Roman expansion under the

late republic). However, eventually the ability of the state to extend its

territorial control becomes limited by the difficulty and expense of projecting

power across space. This connection between the state size and “logistical

loads” is sometimes referred to as the imperial

overstretch principle (Kennedy 1987).

Spatial

location is important

for explaining the geopolitical trajectories of states. Historians noticed long

ago that new, aggressive states that have an excellent chance to grow into a

large empire tend to arise on the marches (edges) of old empires (McNeill 1963). Within the comparative

world-systems perspective, this phenomenon is termed semiperipheral marcher conquest, in which a new state from out on

the edge of the circle of old states conquers all (or most) of the states in

the old core region to form a “universal empire” (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997). The geopolitical theory explains

this empirical pattern by invoking the marchland

position principle: states with enemies on fewer fronts expand at the

expense of states surrounded by enemies (Collins 1995). However, a comprehensive empirical

test on the European material during the first two millennia CE indicates that

there is no statistical association between protected position of a region and

the size of polity emerging from it (Turchin 2003). An alternative explanation is

suggested by the observation that not all imperial marchlands or

semiperipheries give birth to aggressively growing polities. It appears that

incipient empires arise only in locations where pre-existing imperial

boundaries coincide with intense cultural, or ethnic, frontiers. During the

last two millennia the most common symbolic markers demarcating such metaethnic frontiers (the prefix meta indicates the intensity of ethnic

difference across the frontier) have been based on world religions (thus, the

most common variety in the European context are the Christian-Muslim

frontiers). Metaethnic frontiers are zones where groups come under enormous

pressure, and where ethnocide or even genocide, but also ethnogenesis, commonly

occur (Hall 2000). Intense intergroup competition

eventually results in one group with high internal cohesion absorbing other

ethnically similar groups, and in the process constructing the core of a rising

empire (Turchin 2003).

An

implicit assumption of the geopolitical model discussed above is that

geopolitical resources, land and people, come as a package. In reality,

however, the population of a state can grow (or decline) without corresponding

addition or loss of territory. Growing population density initially increases

geopolitical power of the state, because there are more taxpayers and recruits

for the army. However, population growth in excess of the productivity gains of

the land has deleterious effects on social institutions (Goldstone 1991). It leads to persistent price

inflation, falling real wages, rural misery, and urban migration; an increased

number of aspirants for elite positions and intense intra-elite competition;

and spiraling state expenses due to inflation and expanding real costs, since

armies and bureaucracies grow together with population. As all these trends

intensify, the state goes into bankruptcy and loses military control. Elite

movements of regional and national rebellion and a combination of

elite-mobilized and popular uprisings lead to the complete breakdown of central

authority (Goldstone 1991). In turn, state collapse and

ensuing sociopolitical instability cause higher death and emigration rates,

lower birth rates, and negative effects on the productive infrastructure such

as irrigation canals and flood-control dams.[1]

Models incorporating both the effect of population growth on state stability,

and the feedback from state instability to population decline suggest that we

should observe long-term demographic-political cycles, with periods of roughly

two-three centuries (Turchin 2003).

Theories of Rise and Fall

Complex

interchiefdom systems experienced a cycle in which a single paramount chiefdom

became hegemonic within a system of competing polities by conquering adjacent

chiefdoms (D.G. Anderson 1994; Kirch 1984).[2]

Once states emerged within a region they went through an analogous cycle of

rise and fall in which a single state became hegemonic and then declined.

Eventually most of these systems of states (interstate systems), experienced

the phenomenon of semiperipheral marcher conquest in which a new state

from out on the edge of the circle of old states conquered all (or most) of the

states in the old core region to form a “universal empire”.[3]

These

patterns repeated themselves in several world regions for thousands of years,

with occasional leaps in which a semiperipheral marcher state conquered larger

regions than had ever before been subjected to a single power (e.g. Assyrian Empire,

Achaemenid Persia, Alexandrian Empires, the Chin and Han Dynasties, Roman

Empire, the Islamic Caliphates, the Aztec and Inca Empires, the Manchu Dynasty

in China). During the Bronze and Iron Age expansions of the tributary empires a

new niche emerged for states that specialized in the carrying trade among the

empires and adjacent regions. These semiperipheral capitalist city states were

usually “thalassocratic” entities that

used naval power to protect sea-going trade (e.g. the Phoenician city-states,

Venice, Genoa, Malacca), but Assur on the Tigris, the “Old Assyrian city-state

and its colonies,” (Larsen 1976) was a land-based example of this phenomenon

that relied mainly upon donkey caravans for transportation. The semiperipheral

capitalist city-states did not typically conquer other states[4]

to construct large empires, but their trading and production activities

promoted regional commerce and the emergence of markets within and between the

tributary states.

With

the eventual rise of Europe and intensified capitalism a modification of the

old pattern of semiperipheral marcher conquest appeared. In the European

interstate system the semiperipheral marcher states were outdone by a new breed

of capitalist nation-states. These capitalist hegemons established primacy in

the larger system without conquering adjacent core states, and so the core

remained multicentric despite the continued rise and fall of hegemonic core

powers. Imperialism over adjacent states was reorganized as colonial empires in

which each core state had its own distant peripheral colonies – the European

domination of peoples in Africa, Asia and the Americas. The efforts by some

modern core powers to conquer their neighbors were defeated by coalitions that

sought to reproduce a multistate structure among core states. Thus the

oscillation between “universal state” and “interstate system” came to end and

was replaced by the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers. The hegemonic

sequence of the modern interstate system alternates between two structural

situations as hegemonic core powers rise and fall: hegemony and hegemonic

rivalry. This was the new form of the process of rise and fall.

The Westphalian

interstate system, in which the sovereignty of separate and competing states is

institutionalized by the right of states to make war to protect their

independence, has become a taken for granted institution in the modern

world-system. Historians of international relations (e.g. Kennedy 1987) and

theorists of international relations (e.g. Waltz 1979) have come to define this

situation as a natural state of being. Authors with greater temporal depth

(e.g. Wilkinson 1988, 1999) have argued that the peculiar resistance of the

modern interstate system to the emergence of a universal state by means of conquest

has been the result of an evolutionary learning process unique to modern Europe

in which states realized that in order to protect their own sovereignty they

should band together and engage in “general war” whenever a “rogue state”

threatens to conquer another state.

A

rather different explanation of the modern transition from the pattern of

semiperipheral marcher state conquest to the rise and fall of hegemonic core

powers points to the emergent predominance of capitalist accumulation in the

European-centered interstate system.

Once capitalism had become the predominant strategy for the accumulation

of wealth and power it partially supplanted the geopolitical logic of

institutionalized political coercion as a means to accumulation. Powerful capitalist

core states emerged that could effectively prevent semiperipheral marcher

states from conquering whole core regions to erect a “universal state.” The

first capitalist-nation state to successfully do this was the Dutch republic of

the seventeenth century.

There

are several important ways in which explanations of modern rise and fall are

different from one another. One important distinction is between the

functionalists (who see emergent global hierarchies as serving a “need for global

order,”) and conflict theorists (who dwell more intently on the ways in which

hierarchies serve the privileged, the powerful and the wealthy). The term

“hegemony” usually corresponds with the conflict approach, while the

functionalists tend to employ the idea of “leadership,” though several analysts

occasionally use both of these terms (e.g. Arrighi and Silver 1999). Another

difference is between those who stress the importance of political/military

power vs. what we shall call “economic power.” This issue is confused by

disciplinary traditions (e.g. differences between economics, political science

and sociology). Most economists entirely reject the notion of economic power,

assuming that market exchanges occur among equals. Most political scientists and

sociologists would agree that economic power has become more important than it

formerly was. Some of the literature on

recent globalization goes so far as to argue that states and military

organizations have been largely subsumed by the power of transnational

corporations and global market dynamics (e.g. Ross 1995).

The three most important approaches to theorizing modern

hegemony are those of Wallerstein (1984, 2002), Modelski and Thompson (1994);

and Arrighi (1994). Wallerstein defines hegemony as comparative advantages in

profitable types of production. This economic advantage is what serves as the

basis of the hegemon’s political and cultural influence and military power.

Hegemonic production is the most profitable kind of core production, and hegemony

is just the top end of the global hierarchy that constitutes the modern

core/periphery division of labor. Hegemonies are unstable and tend to devolve

into hegemonic rivalry.

Wallerstein

sees a Dutch seventeenth century hegemony, a British hegemony in the nineteenth

century and U.S. hegemony in the twentieth century. He perceives three stages within each hegemony. The first is

based on success in the production of consumer goods; the second is a matter of

success in the production of capital goods; and the third is rooted in success

in financial services and foreign investment stemming from the

institutionalized centrality of the hegemon in the larger world-system.

George Modelski and William R.

Thompson (1994) contend that the world needs order, and world powers rise to

fill this need. Such powers rise on the

basis of economic comparative advantage in newly leading industries, which

allow them to acquire the resources needed to win wars among the great powers

and to mobilize coalitions that keep the peace. World wars are the arbiters

that function as selection mechanisms for global leadership. But the comparative advantages of the

leaders diffuse to competitors and new challengers emerge. Successful challengers

are those that ally with the declining world leader against another challenger

(e.g. the U.S. and Britain against Germany).

Giovanni

Arrighi’s (1994) The Long Twentieth Century employs a Braudelian

approach to the analysis of what he terms “systemic cycles of accumulation.”

Arrighi sees hegemonies as successful collaborations between finance

capitalists and wielders of state power. His tour of the hegemonies begins with

Genoese financiers who allied with Spanish and Portuguese statesmen to perform

the role of hegemon in the fifteenth century. In Arrighi’s approach the role of

hegemon itself evolves, becoming more deeply entwined with the organizational

and economic institutional spheres that allow for successful capitalist

accumulation. He sees a Dutch hegemony of the seventeenth century, then a

period of contention between Britain and France in the eighteenth century, and

a British hegemony in the nineteenth century, followed by U.S. hegemony in the

twentieth century.

A

distinctive element of Arrighi’s approach is his contention that profit making

from trade and production becomes less profitable toward the end of a ‘systemic

cycle of accumulation” and so big capital increasingly focuses on financial

manipulations. Arrighi’s approach is

compatible with the idea that new lead industries are important for the rise of

a hegemon, but he sees the economic activities of big capital during the

declining years in terms of speculative financial activities. These latter

often correspond with a period of “growth” in which incomes are rising during a

latter-day belle époque of the systemic cycle of accumulation. But this

period of accumulation is based on the economic power of haute finance

and the centering of world markets in the global cities of the hegemons rather

than on their ability to produce real products that people will buy, and so

these belle époques are unsustainable bubbles that are followed by

decline.

The

main task of the proposed project will be to develop dynamical models of the

rise and fall of states and the occasional upward sweeps in which newly

emergent states break through the extant ceiling of state size to produce a

much larger polity than has ever existed before (See Figure 2). We will begin

with a demographic and ecological model of the growth and decline of land-based

“tellurocratic” states. Then we will develop a model of the growth of

“thalassocratic” maritime capitalist city-states. These models will then be

combined to model the transition to the “modern” pattern of the rise and fall

of capitalist hegemonic nation-states.

Figure 2: Rise and Fall with Upward Sweeps of State

Size

The basic model

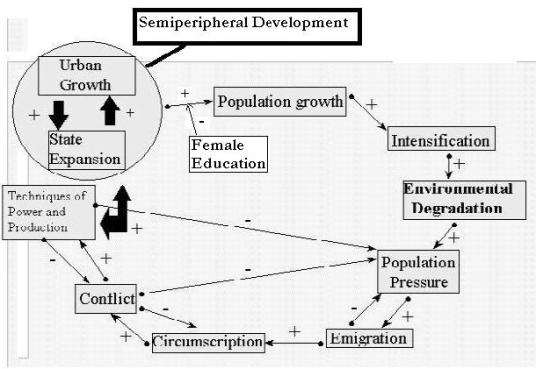

Figure

3 (below) illustrates our several hypotheses about the causal relations among the main variables that cause

city and empire growth. At the top of Figure 3 is Population Growth. Procreation is socially regulated in all human

societies, but despite this there has been a long-run tendency for population

to grow. Population Growth leads to Intensification,

defined by Marvin Harris (1977:5) as “the investment of more soil, water,

minerals, or energy per unit of time or area.”

Intensification leads to Environmental

Degradation as raw material inputs become scarcer and the unwanted

byproducts of human activity (pollution, etc.) modify the surrounding

environment. Together Intensification and Environmental Degradation lead to

rising costs in terms of labor time needed to produce the food and raw

materials that people need, and this condition is called Population Pressure. In order to feed more people, farmers must use more marginal land

because the best soils have become degraded. Or deer hunters must travel father

to find their quarry once deer have become depleted in nearby districts. Thus

the cost in time and effort of producing a given amount of food increases

(Boserup 1965; 1981). Some resources are less subject to depletion than others

(e.g. fish compared to big game), but increased use usually causes rising

costs. Other types of environmental degradation are due to the side effects of

production, such as the build-up of wastes and pollution of water sources.

These also increase the costs of continued production or cause other problems.

As long as there were available

lands to occupy, the consequences of population pressure led to Migration. And so humans populated the

whole Earth. The costs of Migration

are a function of the availability of desirable alternative locations, moving

costs, and the effective resistance to immigration that is mounted by those who

already live in these alternative locations.

Circumscription (Carneiro 1970) occurs when

the costs of leaving are higher than the costs of staying. This is a function

of available lands, but lands are differentially desirable depending on the

technologies that the migrants employ. Generally people have preferred to live

in the way that they have lived in the past, but Population Pressure or other push factors can cause them to adopt

new technologies in order to occupy new lands.

Figure 3: Demographic and Environmental Causes of City

and State Growth[5]

The factor of resistance from extant occupants is also a complex

matter of similarities and differences in technology, social organization and

military techniques between the occupants and the groups seeking to immigrate. Circumscription increases the

likelihood of higher levels of Conflict in

a situation of Population Pressure

because, though the costs of staying are great, the exit option is closed

off. This can lead to several different

kinds of warfare, but also to increasing intrasocietal struggles and conflicts

(civil war, class antagonisms, etc.) A

period of intense conflict tends to reduce Population

Pressure if significant numbers of people are killed off. And some systems

get stuck in a vicious cycle in which warfare and other forms of conflict

operate as a demographic regulator, e.g. the Marquesas Islands (Kirch 1991).

This cycle corresponds to the path that goes from Population Pressure to Migration

to Circumscription to Conflict, and then a negative arrow

back to Population Pressure. When

population again builds up another round of heightened conflict knocks it back

down again..

Under

the right conditions a circumscribed situation in which the level of conflict

has been high will be the locus of the emergence of more hierarchical

institutions, larger states and larger cities. Carneiro (1970) and Mann (1986)

contend that people will tend to run away from state-formation if they can in

order to maintain autonomy and equality. But circumscription prevents exit, and

exhaustion from prolonged or extreme conflict may make subservience to a new

state the least bad alternative. It is often better to accept a king than to

continue fighting. And so kings (and big men, chiefs and emperors) emerged out

of situations in which conflict had reduced the resistance to centralized power.

This is quite different from the usual portrayal of those who hold to the

functional theory of stratification.

The world-system insight here is that the newly emergent elites most

often come from regions that have been semiperipheral. These larger states

build new or expand existing cities.

Intersocietal systems

are often structured as hierarchies in which powerful core states dominate

and/or exploit less powerful semiperipheral and peripheral peoples. And yet

some semiperipheral agents of change are unusually able to put together

effective campaigns for erecting new levels of hierarchy.[6]

This may involve both innovations in the “techniques of power” and innovations

in productive technology (Technological

Change). Newly emergent elites often implement new production technologies

as well as new waves of intensification. This, along with the more peaceful

regulation of access to resources organized by the new elites, creates the

conditions for a new round of Population

Growth, which brings us around to the top of Figure 3 again. Female

education and involvement in the world of work outside the household lowers the

birth rate, and many countries in the contemporary world have stable population

sizes, but the world as a whole has not yet reached that point and so the

iteration model is still working. At some humans are likely to reach a stable

population maximum, and the iteration model will need to be greatly modified to

explain subsequent development.

The emergence of

regional market exchange and states specializing in trade articulate changes in

intensification, environmental degradation and population pressure with

technological change, and so the mechanisms at the bottom of the model in

Figure 2 are by-passed at least temporarily until population growth is so great

that these articulations are overwhelmed. Then the process once again shifts

toward greater conflict.

City growth. The growth of cities, a major component of

the anthropogenic built environment, is affected by multiple factors. One important factor is demographic

change. In the agrarian era cities were

population sinks, and relied on immigration from rural areas to sustain

themselves. Rural population growth exacerbated this “sink” effect. When rural

population increased beyond a certain threshold, rural areas suffered from an

excess of labor, prompting migration to the cities. Such periods were usually

accompanied by a flowering of crafts, because labor was cheap, and elites,

enjoying greater returns from agriculture (due to high rents) tended to spend

some of their wealth on the products of artisan labor. On the other hand, low

real wages meant that an increasing proportion of the urban population was

living below the subsistence level. As a result, urban mortality rates tended

to rise, and birth rates to decline.

Another important factor affecting city growth is technological

development, which leads to greater agricultural productivity and a larger

proportion of population living in the cities.

Improvements in sanitation and health did not greatly affect the urban

mortality rate until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Imperial expansion. So far we have addressed the nonspatial aspects of the modeled

system – either acting in a

local fashion (population growth, agricultural intensification) or, conversely,

in a global fashion (global climate change, millennial growth of technological

knowledge). What makes a model explicitly spatial, however, are processes that

connect various localities, and whose strength declines with distance. One such

mechanism is the spatial expansion of empires resulting from conquest of

adjacent territories. The first, and obvious, factor is the size of the

population controlled by the empire. However, the effect of population size on

military strength is nonlinear. One of

the important factors affecting imperial conquest is the strength of the state

(S), since wealthy empires can raise

large armies, purchase expensive equipment, and sustain armies in the field for

lengthy periods of time. Thus, an empire during the unfavorable phase of the

demographic cycle (when it suffers from fiscal crisis) has great difficulties

in financing war operations. These are periods when empires are extremely

vulnerable to adversary empires, or to barbarians. Other mechanisms affecting

warfare that we will investigate are changes in military technology and the

military advantages of developed by Central Asian steppe nomads during a long

period within the project time frame.

An important spatial process affecting imperial growth is the

logistical aspect of the ability of the state to project its power over

distance. This theory has been well developed as a result of work by Randall

Collins (1999) on geopolitics (see also Hanneman 1995 and Turchin 2003b). We

will model geopolitical processes by focusing on spatial units located on or

near the boundary between adjacent states, and calculating the power that each

state can bring to bear on these spaces. In the simplest formulation, the power

of State 1 delivered to square with coordinate x,y is:

P1(x,y,t) = S1 exp[-d1(x,y)/h]

where S1 is the resources of State

1 and d1 is the distance

from the center of State 1 to the spatial unit x,y. Parameter h

modulates how fast power diminishes with distance (and its units are km). P2(x,y,t) is calculated

analogously. The relative values of P1

and P2 determine whether

State 1 or State 2 will conquer the unit. For example, a simple rule is that

the probability of the square going to State1 is equal to P1/(P1+P2), and vice versa.

The logistics parameter h

can be made a function of the local geography. It is easier to project power

across flat space than across mountains. We will also investigate the effect of

a multiplier that will reflect the military technology available to each state,

or reflect the difference between, say, nomads and settled polities.

Core/periphery status. Examination of the hypothesis that semiperipheral societies

are frequently the loci of change agents that expand and transform

institutional structures will require coding the position of societies in

core/periphery hierarchies. Fortunately David Wilkinson (1991) has already

produced a coding of sedentary societies into core, peripheral and

semiperipheral categories. Our plan is to improve upon Wilkinson’s work by

distinguishing between different kinds of semiperipheries and by including

nomadic peoples.

Causes of East/West

Synchrony

One important product of our modeling

project will be to determine the causes of a fascinating synchrony that emerged

between East Asia and the distant West Asian/Mediterranean region in the

growth/decline phases of cities and empires, but did not involve the

intermediate South Asian region. Studies have used data on both city sizes and

the territorial sizes of empires to examine the hypothesis that regions distant

from one another were experiencing synchronous cycles of growth and decline

(e.g. Chase-Dunn, Manning and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and Manning 2002). Frederick Teggart’s (1939) path-breaking world historical study

of temporal correlations between events on the edges of the Roman and Han

Empires argued the thesis that incursions by Central Asian steppe nomads were

the key to East/West synchrony. A study of city-size distributions in

Afroeurasia (Chase-Dunn and Willard 1993; see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997:

222-223) found an apparent synchrony between changes in city size distributions

and the growth of largest cities in East Asia and West Asia-North Africa over

the period from 500 BCE to 1500 CE. That

finding led to a study of the territorial sizes of empires, which found a

similar synchrony (Chase-Dunn, Manning and Hall 1999). [7]

Plausible causes of these synchronies are climate change, epidemics, trade

cycles, and the incursions of Central Asian steppe nomads.

Global State Formation

The scientific literature on future

global state formation has mainly consisted of linear or quadratic

extrapolations of several different cross-temporal empirical indicators. Robert

Carneiro’s (1978) original study quantified the long-term decline in the number

of autonomous polities on Earth to predict an emergent world state in about

1000 years from the present. Earlier studies by Raul Naroll (1967) and Louis

Marano (1973) had used the territorial sizes of states for a similar purpose.

Peter Peregrine, Melvin Ember and Carol R. Ember (2004) employ a similar

extrapolation approach that uses indicators based on codings of archaeological

evidence. Based on an indicated

quadratic curve over the past 12,000 years, they predict the emergence of a

global state by CE 5000.

The

careful study of the territorial sizes of the largest empires over the past

3000 years by Rein Taagepera (1978, 1997) shows that the largest states in

different regions tended to rise and fall with occasional radical upward

swings. Taagepera observes that the median duration of large polities at more

than half their peak size has been around 130 years. He also notes that

polities that expand fast are somewhat shorter-lived than polities that expand

more slowly. And he reports that three sudden increases in polity sizes

occurred around 3000 BCE, 600 BCE and CE 1600. [8]

Upward Sweeps

The

question of the timing of upward sweeps to new levels is entirely germane to

the problem of modeling global state formation. So also is the issue of how

unusually large states have been formed in the past. Upward sweeps have mainly

been instances of a semiperipheral marcher state conquering and unifying

adjacent older core states and nearby peripheral areas. So conquest has been

the main mechanism of large-scale political integration. But the pattern of

hegemonic rise and fall in the modern world-system has been different. The most

powerful states, the hegemons (the Dutch, the British and the United States),

have fought semiperipheral challengers (e.g. Napoleonic France and Germany) to

prevent the emergence of a core-wide empire. We contend that this is because

the hegemons are the most capitalist states in the system, the ones for whom

economic success is most closely tied to the ability to make superprofits on the

technological rents that return from new lead technologies.

Only during hegemonic decline have

the modern capitalist hegemons shown a tendency toward “imperial overreach” in

which their military power is employed in a last ditch effort to prop up a

declining economic hegemony. These efforts have not been successful, and a new

hegemon only emerges after a period of hegemonic rivalry and world war. This is

a method of choosing “global leadership” that we can no longer afford to

employ, and so the issue of institutions that can peacefully resolve the

struggle for hegemony is of the first importance for our very survival as a

species.

The

approach that we propose is to model the main causes of state formation and

upward sweeps taking into account the ways in which the basic processes have

been altered by the emergence of new institutions. We will elaborate and improve upon the recent work of Robert

Bates Graber (2004). Graber develops

both an ahistorical and an historical population pressure model of political

integration. His ahistorical model is a very simplified version of the

iteration model displayed in Figure 3 above that includes population growth

rates and the number of independent polities. Graber’s historical model takes

account of the emergence of the League of Nations and the United Nations as our

approach will do. But we add the rise and fall cycle, the emergence of markets

and capitalism, and the growth of other international political organizations

and non-governmental organizations to our model of political globalization.

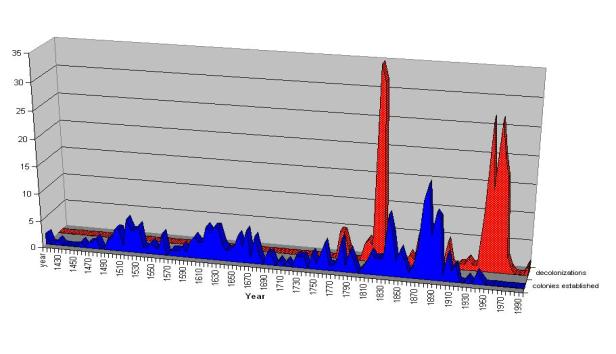

The

main political structure of the modern world-system has been, and remains, the

international system of states as theorized and constituted in the Peace of

Westphalia. This international system of competing and allying national states

was extended to the periphery of the modern world-system in two large waves of

decolonization of the colonial empires of core powers. The modern system

already differed from earlier imperial systems in that its core remained

multicentric rather than being occasionally conquered and turned into a

core-wide empire. Instead, empires were organized as distant peripheral

colonies rather than as conquered adjacent territories. Earlier instances of

this type of colonial empire were produced by thallasocratic states, mainly

semiperipheral capitalist city-states that specialized in trade. In the modern

system this form of colonial empire became the norm, and the European core

states rose to global hegemony by conquering and colonizing the Americas, Asia

and Africa in a series of expansions (see Figure 4). The international system

of sovereign states was extended to the colonized periphery in two large waves

of decolonization (see Figure 4). After a long-term trend in which the number

of independent states on Earth had been decreasing, that number rose again with

decolonization and the core states decreased in size when they lost their

colonial empires.

Extension of the

State System to the Periphery

The

decolonization waves were part of the formation of a global polity of states.

And one of the decolonized regions became “the first new nation,” and

eventually rose to hegemony to become the largest hegemon the modern system has

seen – the United States. The doctrine

of the national self-determination, long a principle of the European state

system, was extended to the periphery.

Figure 4: Waves of colonization and decolonization

based on Henige (1970)

This multistate system has also

experienced waves of international political integration that began after the

Napoleonic Wars early in the nineteenth century. Britain organized a “Concert

of Europe” (Jervis 1985) that was intended to prevent future French revolutions

and Napoleonic adventures. During the middle of the nineteenth century a large

number of specialized international organizations emerged such as the

International Postal Union (Murphy 1994) that underwrote the beginnings of a

global civil society that included more than elites, and this network of

transnational voluntary associations grew much larger during the most recent

wave of economic globalization since World War II. After World War I the League of Nations was intended to provide

collective security, though it was weakened by the failure of the United States

to join. After World War II the United Nations became a proto-world-state, the

efficacy of which has waned and waxed since then. The system of national states

is being slowly overlain by global and regional transnational political

organizations that blossom after periods of war and during periods of economic

globalization.

Our

historical model will add marketization, decolonization, new lead technologies,

the rise and fall of hegemons, and the rise of international political

organizations to the population pressure model in order to forecast future

trajectories of global state formation. And we will assemble empirical data for

the last two hundred years on the trend toward global political integration in

order to parameterize our models. This will allow us to examine how changing assumptions

about the relationships among variables will affect probable future

trajectories of international political integration. Our conceptualization of

the cyclical nature of many processes will allow us to consider how downward

plunges and possible collapses might affect the probable trajectories of global

state formation.

We

will also take into account the structural differences between recent and

earlier periods. For example, the period of British hegemonic decline moved

rather quickly toward conflictive hegemonic rivalry because economic

competitors such as Germany were able to develop powerful military

capabilities. The U.S. hegemony has been different in that the United States

ended up as the single superpower after the decline of the Soviet Union.

Economic challengers (Japan and Germany) cannot easily use the military card

because they are stuck with the consequences of having lost the last World War.

This, and the immense size of the U.S. economy, will probably slow the process

of hegemonic decline down relative to the speed of the British decline

(Chase-Dunn, Jorgensen, Reifer and Lio, Forthcoming). [9]

Our

modeling of the global future will also consider changes that have occurred in

labor relations, urban-rural relations, the nature of emergent city regions,

and the shrinking of the global reserve army of labor (Silver 2003).

TheTrajectory of Political Globalization

We

conceptualize political globalization analogously to our understanding of

economic globalization as the relative strength and density of larger versus

smaller interaction networks and organizational structures. Much has been written about the emergence

and development of global governance and many see an uneven and halting upward

trend in the transitions from the Concert of Europe to the League of Nations

and the United Nations toward the formation of a proto-world state. The

emergence of the Bretton Woods institutions (the International Monetary Fund

and the World Bank) and the more recent restructuring of the General Agreement

of Tariffs and Trade as the World Trade Organization, and the visibility of

other international fora (the Trilateral Commission, The Group of Seven

[Eight]; the World Economic Forum, the World Social Forum meetings, etc.)

support the idea of emerging global governance. The geometric growth of international non-governmental

organizations (INGOs) is also an important phenomenon of global governance and

the emergence of global civil society (Murphy 1994; Boli and Thomas 1999).

As

we have discussed above, all world-systems go through cycles of political

centralization and decentralization with occasional leaps toward new and higher

levels of political integration (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997). In the modern

world-system the cycle for the last 400 years has taken the form of the rise

and fall of hegemonic core states. Some claim that the hegemonic sequence is now morphing into a new structure of core

condominium (Goldfrank 1999). We intend

to study both the hegemonic sequence and emerging global governance. While

these might be combined into a more general concept of political globalization,

we contend that it is important to keep them separate because hegemonic rise

and fall is an old feature of the world-system, whereas political globalization

is arguably much more recent. Political

globalization can be analytically reduced to the question of the relative

strength of larger vs. smaller political and military organizations (including

also the functionally “economic” ones (IMF, World Bank, WTO) mentioned above.[10]

Data Development,

Measurement Strategies and Units of Analysis

This project will develop a World

Historical System Time Map using an optimalized Afroeurasian cartographic grid

that includes the focal regions we are studying. We will establish an Internet

Collaboratory website. This will enable us to share access to the joint

products of our research and to update modeling and data enhancements easily

with all the project participants.

The project will develop programs to

directly link the spatio-temporal database with our simulation models and

statistical analyses, and to move modeling results back into the

spatio-temporal format for visualization of modeling results. We will produce a

relational database that is in an interoperable format to be linked with

digital gazetteers and libraries such as the Alexandria Digital Library and the

Electronic Cultural Atlas Initiative.

The basic strategy is to use

statistical analyses of urban growth and changes in the territorial size of

empires over the last three thousand years to parameterize our models. This

will involve utilizing and extending three existing compilations of data:

Tertius Chandler's (1987) Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth, George

Modelski’s (2003) World Cities, -3000-2000 and Rein Taagepera's (1978a;

1978b; 1979; 1986; 1997) studies of the territorial sizes of empires.

We have developed a plan for

enhancing these datasets on city populations and locations, the territorial

sizes and geographical boundaries of states and empires, power configurations

of interstate systems, climate change indicators, warfare, trade fluctuations,

migrations and incursions. Using these data we will construct several different

kinds of measures (e.g. city size distributions, empires size distributions)

and will utilize sophisticated methods for splicing earlier, poorer indicators

with later, better ones.

Units of Analysis

Our spatio-temporal database will code the locations

of events, settlements, polity boundaries, wars, epidemics and climate change

indicators. We will use three different approaches to the problem of units of

comparison for our statistical analyses:

1.

single

states;

2.

political/military

networks (which change their sizes over time because of expansion),

3.

and

constant regions (East Asia; South Asia, Central Asia; West Asia/Mediterranean;

and (after 500 BP) North and South America.

Using both political/military

networks (2) and constant regions (3) will allow us to crosscheck our results

to see if our way of bounding “cases” affects inferences about causal

relations.

Model Testing

We plan to test portions of our models using

structural equations modeling (SEM) and path analysis. Our data sets will have

a pooled-cross-section and time-series (panel) structure that can be used for

the estimation of structural equation models.

For example, a city’s population size at any t+1 will be modeled

as a linear additive function of its size at t, plus the magnitude of

trade inflows to the city at t, and the political centrality of the city

at t. The error structures of

such models are relatively complex, owing to both the pooled cross-sectional

and time-series design, and to the geographical or network embeddedness of

cases, but econometric modeling approaches to such problems are well

understood. We will test hypotheses about the causes of rise/fall and synchrony

with multiple time series analysis across PMNs and regions with attention to

the need to detrend variables and problems of temporal autocorrelation.

There is a single size distribution of political/military

organizations in the modern world-system. We will operationalize three

different parts of this size distribution, as well as the whole thing. Our conceptualization of political

globalization will be analogous to our understanding of economic globalization

– a ratio of the size and importance of global and international organizations

vs. the sum of size and importance of national (and multinational) states. But we will also operationalize the

hegemonic sequence by examining changes in the distribution of economic and

military power among the core states using the research of Modelski and

Thompson (1996). And we will study the

changing shape of the whole system of states as well, taking into account the

processes of colonization and decolonization (Bergesen and Schoenberg 1980),

the incorporation of the peripheral and semiperipheral regions into the

interstate system, and changes in the distribution of economic and

political/military power in the whole system of states. We will also combine political globalization,

hegemonic rise and fall, and state power stratification into a single overall

measure of the distribution of power among state and proto-state institutions.

This latter we will call “overall global political/military inequality.”

Education Activities

Involvement

in this project will provide to graduate and undergraduate participants an

advancement of learning in both an individual and a social sense, and will

encourage the students to become generalists with a capacity to conduct their own

research as well as to move easily into more advanced doctoral or professional

study of global processes. We will

train the graduate and undergraduates working on this research project to do

interdisciplinary non-linear modeling and comparative research. They will be

exposed to the process of solving problems and moving research forward by being

involved in the weekly meetings conducted with the PIs and other advisors who

play a part in the project. Students will gain interdisciplinary data analysis

and modeling skills and will be encouraged to collaborate in the writing and

presentation of scholarly research papers for professional meetings and the

development of web-accessible materials stemming from our project.

Though

a major effort will be devoted to building and testing mathematical models, this project will also upgrade existing data

on key measures on the World Historical System Time Map.[11]

This refreshed spatio-temporal relational database will be used to produce

interpretive maps of the emergence of cultural complexity for high school and

college classes. Our data base

construction and model building will benefit from the collaboration of GIS

scientists from Environmental Sciences Research Institute (ESRI), a private

industry developer of GIS software and provider of spatial analyses in

Redlands, California. Graduate research assistants from our project will be

encouraged to participate in summer internships at ESRI.

A

key element of this project is the development and publication of an educational

web site based on our research and teaching. We will produce and make available

to the world community an educational resource that contains products from our

project that have been rewritten for use in high school and college courses.

The title of this educational web site will be “Human Social Dynamics,

Globalization and World State Formation.” This will include syllabi for

interdisciplinary global studies courses, graphical representations of our data

and modeling results, numerical geochronological datasets for use by students

for statistical analyses, and working papers produced by our project. We will

use the results of our data collection and analyses, and our World Historical

System Time Map to produce animated maps of Afroeurasia and the Americas for

presentation on our educational web site.

These will show where cities and empires rose and fell over the past

3000 years, how climate changed, and the emergence of trade routes, information

flows, and warfare interactions and alliances. Our education web site will have

versions in English, French, Mandarin, Russian and Spanish; and the graphical

presentations will be of use to teachers all over the world. These will be available for use in high

school world history and global history courses as well as in college courses

on environmental history, global studies, climate change, human ecology,

comparative civilizations, social evolution, and geography.

Management Plan

Realizing

our model-building goals will require a concentrated and coordinated effort in

collaboration with the data infrastructure effort. Assemblage of an integrated

geo-chronological database will involve a great deal of coordinated labor. The

Internet Collaboratory website will enable us to coordinate our efforts and to

share access to the joint products of our research with our senior advisors and

student researchers. Statistical

analyses to test causal propositions and fully operational complex models will

be achieved only after a considerable amount of prior work, and will depend on

the development of an interoperable knowledge system of spatially and

chronologically tagged information, the World Historical System Time Map

(WHSTM).

The

co-Principal Investigators are Christopher Chase-Dunn (Sociology, UCR), E.N.

Anderson (Anthropology, UCR) and Peter Turchin (Ecology and Evolutionary

Biology, University of Connecticut).

Chase-Dunn will carry out the overall administration of the project

(with grants management help at UC Riverside). He will oversee the project’s

Internet Collaboratory, and modeling of the causes of synchrony. Anderson will

coordinate the enhancement of datasets and the development of the World

Historical Systems Time Map. Turchin will build non-linear dynamic

spatio-temporal mathematical models of the historical dynamics of state growth

and decline, rise and fall, and upward sweeps in interstate systems. The project has 18 Advisors from

the United States and China (see below).

The Co-PIS at UC-Riverside and the

University of Connecticut will oversee graduate and undergraduate research

assistants. The evaluations of the project activities will be done by project

participants in interaction with students and colleagues attending professional

conferences until the final year. At the final working conference five experts

in dynamical modeling and macrohistorical social science who have not

participated in the project will prepare critiques of the penultimate version

of our models for presentation at the conference.

Advisors

Robert Carneiro

(American Museum of Natural History)

Claudio Cioffi (Computational Social

Science, George Mason University)

Roland Fletcher (Anthropology,

University of Sydney)

Robert Hanneman (Sociology, UCR)

Jack Goldstone (Sociology, George

Mason University)

Thomas D. Hall (DePauw

University)

Wang Jun, Beijing, (National Academy

of Geography, Beijing)

David Kowalewski (Political Science,

Alfred University)

Bai-lian Li (Botany and Plant

Sciences, UCR)

Craig Murphy (Political Science,

Wellesley College)

Jenny Pournelle, (Silk Road Project)

William I. Robinson (Sociology,

University of California-Santa Barbara)

Rein Taagepera, (Political Science,

University of California-Irvine)

Peter J. Taylor, (University of

Loughborough)

William R. Thompson (Political

Science, Indiana University)

Pao K. Wang (Atmospheric and Oceanic

Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison)

David Wilkinson (Political Science,

UCLA)

Zhiqian Yu: (ESRI, Redlands)

Work Plan

1st year

(October 2005-September 2006)

Organize and implement coordination

and communication among principal investigators and advisors. Begin weekly

Project Meetings at UC, Riverside. Set up the Internet Collaboratory for

the research project. Hire and train undergraduate and graduate research

assistants.

Ø Data: Establish standards: spatial

notations, time, location, and resolution.

Develop coding protocols for city, empire, core/periphery status and

climate change data. Develop separate bibliographies for city sizes, empire sizes

and climate change information. Systematically search libraries at the

University of California and the University of Connecticut, and Interlibrary

Loan Collections. Begin search and acquisition of climate change databases.

Develop specialized search engine software for digital data acquisition from

JSTOR and other digitized databases. Develop separate initial databases using

easily obtained information for city sizes, empire sizes, climate change,

warfare, trade, and migrations. Merge the already-coded city, empire and

climate change data in a prototype of the integrated geochronological database

(WHSTM1). Fine-tune design of the database. Locate significant gaps in the data. Make a plan for efficiently

filling them given resource constraints. Work on nesting, linking problems and

develop connections with interoperable on-line geocoded digital libraries.

Coordinate this with TimeMap®, ADEPT and ECAI.

Ø

Software:

Acquire and customize state-of-the-art spatiotemporal relational database and

network analysis software.

Ø

Model

Development: Fine-tune the overall modeling plan with feedback from all

participants. Develop modeling

standards. Acquire existing models. Formulate base models. Create simple

regional models (limited time-frames, limited numbers of variables). Arrange

all components in a format where they can communicate with one another. Redo

existing models for our purposes. Work on parameters, initial values. Get them

running separately. Figure out how to couple them. Work on nesting, linking

problems and further develop connections with GIS. Report on revision of

prototypes to incorporate emerging models and interoperability considerations.

Develop prototype complex causal models of macrosocial processes in interaction

with the environment.

Ø

Education:

Develop interdisciplinary courses on World Historical Systems and the

Environment. Send graduate research

assistants from our project to participate in summer GIS internships at ESRI in

Redlands, California.

2nd year

(October 2006-September 2007)

January Working Conference

at University of California-Riverside

Ø Data:

Develop the mechanism for updating and cross-linking data bases. Work on

filling in gaps, splicing series, generating statistics that can be input into

statistical analyses. Compare different approaches to interpolation and

uncertainty management. Produce WHSTM2.

Ø Analyses: Examine the interactions

within regions among urbanization, empire formation and climate change. Examine

the hypothesis of cross regional synchronization of city and empire

growth/decline phases with the WHSTM2.

Ø

Education:

Give interdisciplinary courses. Establish educational web site on

“Globalization and the Environment.” Involve students in research, teaching,

publications and conferences.

Ø

3rd year (October

2007-September 2008)

v latest versions of models;

v penultimate version of WHSTM;

v the results of statistical analysis

of the integrated database.

Revise or fine-tune the data model,

the resulting database and the analyses taking criticisms and suggestions from

advisors into account. Revise models taking criticisms and suggestions into

account. Produce final models.

Ø Model Development: Reparameterize

complex models with WHSTM2. Further refine the models.

Ø Analyses: Develop a temporal

map-rendering engine and data quality visualizations for the animations. Use

preliminary data to test different causal propositions. Set up Structural

Equations Model (SEM) of causes of synchronization. Use completed data set to

test SEM models and to parameterize complex models. See if we still find

synchronization of city and empire growth decline phases 650 BCE to 1500 CE

using upgraded datasets. If so, test models of causation of this

synchronization using SEM.

Ø Education: Produce proto-types of

animated graphics for educational web site using WHSTM2. Develop

linguistic themes in Mandarin, French, Spanish and Russian using appropriate

civilizational place names. Continue courses and student involvement in

research. Publish final versions of our models. Put the WHSTM into most recent formats compatible with

Alexandria Digital Library and the Electronic Cultural Atlas Initiative.

Publish the final revised version of the World Historical System Time Map,

(now linked with data resources in other locations), final statistical datasets

and final versions of animated graphics on our educational web site,

“Globalization and World State Formation.”

Present papers at conferences. Write books and articles for publication.

Prepare project report for NSF.

Project Significance

The

three-year project will develop new mechanism-rich spatio-temporal models of state formation, rise and

fall and upward sweeps of state size. This

project will produce an integrated complex model of social change in

interaction with the environment that will provide a quantitative understanding

of the long-term dynamics of world historical development. The modeling and

data-gathering efforts will provide important scientific interpretations of the

long-run dynamics of interactions of the cultures and institutions developed by

humans with the natural environment. The World Historical System Time Map is a

geo-chronological database containing information on fundamentally important

variables in a standardized format for other researchers as well as for

teachers, students and decision makers. The project will produce and make

available to the world community, through the educational web site "Human

Social Dynamics, Globalization and World State Formation", an educational

resource that contains products that have been rewritten for use in high school

and college courses.

The

modeling of the dynamics of agrarian interaction networks will make it possible

to compare these with the global interaction network that has emerged in the

last two centuries in order to understand both the similarities and the

differences. The educational products of the project will help to inform the

next generation of scientists and world citizens about the patterns of social

evolution and their implications for future global governance and the

educational products of the project will help to inform scholars and students

about the patterns of social evolution and their implications for human life on

Earth in the coming decades. The products of this proposed effort will allow

scientists, citizens and policy-makers to better anticipate and confront

problems of sustainability and social conflict that are likely to emerge in the

21st century. The project of

global polity building will be informed by study of the conditions that will

influence probable future trajectories of world state formation.

References Cited:

Abu-Lughod,

Janet Lippman 1989 Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D.

1250-1350 New York:

Oxford University Press.

Arrighi,

Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of

Our Times. London:

Verso

Bairoch,

Paul 1988 Cities and Economic Development.

Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Barabási,

A.-L. 2002. Linked: The New Science of Networks. Cambridge, MA: Perseus

Publishing.

Barfield,

Thomas J. 1989. The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China.

Cambridge,

MA: Basil Blackwell.

Bentley,

Jerry H. 1993. Old

World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern

Times. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Bergesen,

Albert and Ronald Schoenberg 1980 “Long waves of colonial expansion and

contraction

1415-1969” Pp. 231-278 in Albert Bergesen (ed.) Studies of the Modern

World-System. New York: Academic Press

Boli, John

and George M. Thomas 1997 “World culture in the world polity,” American

Sociological Review

62,2:171-190 (April).

__________

(eds.)1999 Constructing World Culture:

International Nongovernmental Organizations

Since 1875.

Stanford: Stanford University Press.