Long Cycles and World-Systems:

Theoretical Research Programs

Marquesan warrior from Nukahiva

Christopher Chase-Dunn and Hiroko

Inoue

Institute

for Research on World-Systems, University of California Riverside

![]()

An earlier version was presented at the annual meeting of

the Social Science History Association, Chicago, November 18, 2016. A revised

version will appear in William

R.Thompson (ed.) Oxford

Encyclopedia of Empirical International Relations Theories,New

York: Oxford

University Press and the online Oxford Research

Encyclopedia in Politics v. 1-19-17, 8962 words

This is IROWS Working Paper #115

available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows115/irows115.htm

The world-systems theoretical

research program employs anthropological and biological frameworks of

comparison to comprehend the evolution of geopolitics and economic

institutions. The scale and complexity of the contemporary global system is

analyzed as the outcome of processes that structured the Darwinian evolution of

cultureless social insects as well as the sociocultural evolution of human

organizations.[1]

Multilevel selection, and especially group selection primarily driven by

warfare, was a primary force behind of the emergence of large-scale social

organization for both humans and ants.[2]

The

world-system perspective emerged in the context of the world revolution of 1968

with a focus on the structural nature of global stratification – now called

global north/south relations. Because it emerged mainly from sociology and

radical economics it was somewhat immune to the tectonic debates between the realists

and the liberals in international relations. But there has been considerable

overlap with some international relations schools, especially the long cycle empirical

theory developed by George Modelski and William R. Thompson (Modelski 1987;

Modelski and Thompson 1988;1996). Despite different conceptual terminologies,

these approaches have had much in common, and both became interested in

questions of long-term sociocultural evolution. One important difference is with regard to the

attention paid to the non-core. Like most international relations theorists,

Modelski and Thompson focused most of their attention on the “great powers” in

the interstate system – what world-system scholars call the core (but see

Thompson and Modelski 1998; Reuveny and Thompson 2007). The world-systems

scholars see the whole system, including the periphery and semiperiphery, as an

interdependent and hierarchical whole in which power differences and economic

differences are reproduced by the normal operations of the system. The

core/periphery hierarchy is a fundamental theoretical construct for the

world-system theory.

International

relations theory is about the logic of power that exists in networks of

competing and allying polities. It has been developed mostly by observing and

trying to explain what happened in the European state system since the treaty

of Westphalia in 1648, but a similar logic was probably operating in earlier

interpolity systems (Wohlforth et al

2007). The comparative world-systems theoretical research program has been

developed to comprehend and explain sociocultural evolution as it has occurred

in an anthropological comparative framework – by considering prehistoric small

scale human polities and interacting systems of those polities since the Stone

Age. We review some of the basic

concepts of the world-systems empirical theory and report upon the research

that has been done to test some of the propositions that stem from it.

Territoriality is a feature of interaction among

microorganisms, insects, plants and animals. A complete grasp of the roots of

human imperialism would need to take this larger biogeographical context into

account. Organized warfare and competition for territory first emerged about 50

million years ago among social insects, especially ants. In an early version of

imperialism some ants kill the queen in an invaded colony and substitute their

queen for the dispatched old queen and thus harness the labor of the invaded

colony for raising and feeding the offspring of the invaders. The ant/human

comparison reveals a fascinating case of parallel evolution in which rather

similar behaviors and social structures emerged by very different processes of

selection--Darwinian in the case of insects, cultural in the case of humans

(Gowdy and Krall 2015; Turner and Machalek 2017: Chapter 15). Ants forge strong

cooperation based on so-called genetic eusociality. Most of the workers in a colony are closely

genetically related because they are the offspring of a single queen. This

produces a superorganism at the level of the colony and so it is colonies

rather than individuals or small groups that compete with one another for

territory and resources. The social insects prove that even Darwinian natural selection

operating in the absence of culture and in the presence of only simple

communication techniques and relatively simple nervous systems in individuals

can produce complex social structures when group selection is operating. This

is the important thing about the emergence of warfare among colonies of social

insects. Gowdy and Krall (2015) stress the importance of collective food

gathering, but it is the interaction of resource acquisition and competition

for territory that drives the emergence of complex social structures among

insects. These same mechanisms turn-out to be important for driving the

emergence of complex social structures among humans, though the process is

speeded up by the emergence of culture and complex cognition.

Human cooperation beyond

the level of the family is based on ideology and institutional mechanisms that

facilitate integrated action. It is the

evolution of institutional mechanisms such as states and markets

that

have made it possible for large groups of humans to cooperate with one another.

Competition for resources occurs simultaneously at several different levels

–between individuals, families, organizations and polities. Warfare among

polities has been an important selection mechanism driving sociocultural and

human biological evolution since the Stone Age.

Our

stance on theory is germane to the tasks set by the editor of this collection

(Thompson 2017). We follow the cumulative theory and testing approach embodied

in Imre Lakatos’s (1978) schema of theoretical research programs. Theories should

be explicitly and clearly formulated regarding the meanings of concepts and

interrelated causal propositions. Formalization can be axiomatic or can be

simulation models. We favor the latter (see Fletcher et al 2011). Different

formalized models can be compared regarding their simulation outcomes and parts

of these can be empirically tested. Our theoretical research program is still

under construction, but we can report some of the results so far.

The Long Cycle

Theory

Many social scientists have

correctly stressed the importance of warfare as a major selective mechanism

producing social change in world history (Spencer 1898, Mann 1986;

Army Ants

2013; Turner 1985, 2010; Cioffi-Revilla

1996; Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997; Turchin 2003, 2007; Morris 2014). The long

cycle theory asserts and demonstrates important interactions between economic

and military power. As we have already said, there is a considerable overlap of

both analytical framework and theoretical assumptions between the world-system

perspective and some formulations of international relations theory. The approach within international relations

theory that is closest is the long cycle approach developed by George Modelski

and William R. Thompson (1996). This perspective has many grounding schemes in

common with the world-system perspectives, despite that the conceptual

terminologies are rather different.

Modelski and Thompson (1996) contend

that the current global political economy began to take shape around 1500AD.

This is like Immanuel Wallerstein’s

depiction of the rise of the modern world-system in the long 16th

century (Wallerstein 2011a). They argue

that major processes operating now were already recognizable in the 16th

century (Thompson 2000). Modelski

(1990), following the functionalism of Talcott Parsons (1966, 1971), sees

globalization as a general process of evolutionary learning by the human

species. The story is one in which the

human species transformed and built new institutions over a millennium, and the

successive steps revealed the “development of a planetary constitutional

design” (Modelski 2006:14)

Sociocultural evolution is, in Modelski’s

approach, a multilevel and self-organizing process. Using a Kantian and Parsonsian learning model

of social evolution, the long cycle approach contends that the generative

principle of world politics is based on an evolutionary learning process

(Modelski 1990). A major assumption is that the world needs to

have an order and that world powers rise to fulfill this need. It is presumed

that the long cycle in which great powers rise and fall results in a

progressive evolution of world politics that emerges from the functional needs

of the system (Modelski and Thompson 1996).

In

the long run of sociocultural evolution both the long cycle approach and the world-systems

perspective see the rise and fall of powerful polities as an important dynamic. The long cycle model depicts a process of

co-evolution of economic and political power sequences while the world-system

approach examines the hegemonic sequence (see Wallerstein 1984; Chase-Dunn

1998:

Chapter 9). The long cycle theory focusses on both economic

and military power. Economic power is

seen as an important and driving basis of global military power. The focus is

on the development within the leading power of new cutting-edge technologies of

production in which the leading power holds a comparative advantage (Modelski

and Thompson 1996). Military power is seen to be of two different kinds:

land-based forces allow powerful states to influence their contiguous

neighbors, while seapower is the key to global leadership (see also Rasler and Thompson. 1994).[3]

Modelski and Thompson (1988, 1996) measured

the concentration and deconcentration of naval power in the European interstate

system to reveal the world power sequences of Portugal in the 15th

century, the Dutch in the 17th century and the Britain in the 18th

and 19th centuries (two long cycles), and the U.S. in the 20th

century. The rise of new lead industries

is the basis of competitive political and economic advantages that have been

the main causes of the rise and fall of great powers. Modelski and Thompson

also show the ways in which the

Kondratieff Wave (K-waves of 40 to 60-year business cycles) are associated with

the rise and decline sequence of system leaders. K-waves and long long cycles are intertwined

such that there are two K-waves within each approximately 100-year long cycle. Modelski

(2005) also sees a long-term trend across hegemonies in which economic power

becomes more important and political/military power becomes more democratic.

Global

powers rise due to their comparative economic advantages in innovative and

transformative technological sectors in world commerce and industry – so-called

“new lead industries.” The economic resources from new lead industries allow it

to

win wars and to exercise

both military and political influence in the system. War and diplomacy are the mechanisms that produce

global integration and the concentration of global power, but success in war is

mainly a consequence of success in the development of new lead industries. Modelski

(2005) also employed the idea of imperial overreach that was formulated in Paul

Kennedy’s Rise and Fall of the Great

Powers (1987). During the decline phase of a long cycle the system leader

sometimes overplays the military card after economic comparative advantage has been

lost. The U.K prosecution of the Boer Wars and U.S. unilateral military policy

during the 2nd Bush administration are given as examples. phase

Periods of hegemony are associated with peace

and periods of hegemonic decline are associated with war. Long cycles are seen to be composed of four

phases: the winner of a global war emerges from the

struggle for global leadership and maintains its position through naval power.

The logistical and ideological costs associated with global leadership

contribute to the world power's decline, giving way to two new stages: delegitimation

(decline in relative power) and deconcentration (challenges from emerging

rivals). Deconcentration proceeds until new contenders for world leadership

attempt to push the declining leader out of its hegemonic position. Modelski

and Thompson also note that hegemonic success often passes to a challenger that

has been allied with the previous hegemon.

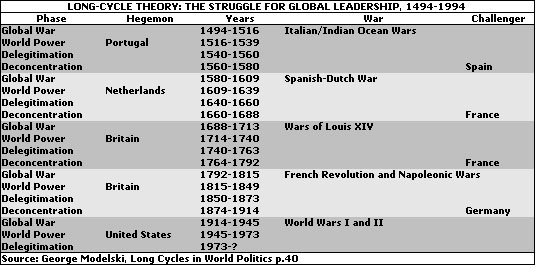

There have been five long cycles since the 16th

century (see Table 1), with Britain having completed two of them as hegemon.

This led Joachim Rennstich (2001) to argue that the United States might be able

to serve as hegemon in another power cycle (but see Chase-Dunn et al 2011).

Table 1:

Long cycles in the modern system

The long cycle perspective claims to be

based on structural functionalist theoretical assumptions about social learning

and progress. Indeed, despite all the

attention to the importance of economic power, the word “capitalism” is never

mentioned by Modelski and Thompson.[4]

Others have pointed out that assertions about progress are troublesome and

unnecessary aspects of some theories of sociocultural evolution (Sanderson

1990). Patterns and their causes may be described and explained without the baggage

that is involved in normative statements about whether what has happened is

good or evil. The explanations in the long cycle theory can be evaluated

separately from its functionalist claims about learning and progress.

We should also note that George

Modelski (2003) produced a monumental contribution to our knowledge of the

population sizes of large cities since the Bronze Age by updating extending the

important compendium produced by Tertius Chandler. Modelski saw the emergence

of large cities as a central component of sociocultural evolution, a

perspective shared by some world-systems scholars (e.g. Inoue et al. 2015) and some historians

(Braudel 1984, Morris 2010, 2013).

World-System Theory

The world-system approach is less functionalist

and more critical of power. Perhaps this is due in part to its origins during

the world revolution of 1968 and the anti-Vietnam war movement, but it may also

stem from greater attention to those who live at the bottom of the system (the

non-core). And rather than talking only

of economic development and economic comparative advantage, the

world-systemists describe and analyze the rise to predominance of capitalism. They

employ ideas from both Karl Marx and Max Weber to produce a critical prehension

of world historical social change. The world-systems theorists have mainly been

sociologists while the long cycle theorists are political scientists. In the

1960s sociologists were busy overthrowing their intellectual parents,

especially Talcott Parsons, while political scientists had different ancestors

and were more easily able to see the good things in Parsons’s evolutionary

synthesis. The main constructor of the world-systems approach in the 1970s were

Immanuel Wallerstein, Terence Hopkins, Samir Amin, Andre Gunder Frank and

Giovanni Arrighi. While there are interesting and important differences among

them, we will focus here primarily on Wallerstein, Hopkins and Arrighi because

their approaches are the most germane for the comparison with the long cycle

theory.

Terence

Hopkins and Immanuel Wallerstein (1979) described the cyclical rhythms and

secular trends of the capitalist world-economy as a stable systemic logic that

expands and deepens from its start to its end, but that does not much change

its basic nature over time. Giovanni Arrighi (1994) saw overlapping systemic

cycles of accumulation in which rising and falling hegemons expand and deepen

the commodification of the whole system. His modern world-system oscillates

alternates back and forth between more corporatist and more market-organized

forms of political structure while the extent of commodification deepens in

each round (Arrighi 2006). He builds on Wallerstein’s focus on hegemony as

based on comparative advantages in profitable types of production (Wallerstein

1984, 2004). And he utilizes Wallerstein’s idea that each hegemon goes through

stages in which the comparative advantage is first based on the production of

consumer goods, and then capital goods and then finance capital (see also

Arrighi and Silver 1999; Arrighi 2008). Arrighi

was also inspired by the work of Fernand Braudel to focus special attention on

the changes in the relationships between finance capital and state power that occurred

as the modern world-system evolved. For

both Wallerstein and Arrighi the hegemon is the top end of a global hierarchy

that constitutes the modern core/periphery division of labor. Hegemonies are

unstable and tend to devolve into hegemonic rivalry as comparative advantages

diffuse and the hegemon cannot stay ahead of the curve. Arrighi’s formulation

allows for greater evolutionary changes as the modern system expanded and deepened

while the Wallerstein/Hopkins formulation depicts a single continuous underlying

logic that does not change much except at the beginning and the end of the

historical system.

As we have mentioned above, the

world-systems scholars study the dialectical and dynamic interaction between

the core, the semiperiphery and the periphery and how these interactions are

important for the reproduction of the core/periphery hierarchy and how they

affect the outcomes of struggles within the core for hegemony (Boswell and Chase-Dunn

2000). The hegemon and the other great powers are the top end of a global

stratification system in which resources are competitively extracted from the

non-core and resistance from the non-core plays an important role in the

evolution of the system. This approach focusses on both institutions and on

social movements that challenge the powers that be. It is noted that

rebellions, labor unrest and anti-colonial and anti-imperial movements tend to

cluster together in certain periods. Often in the past the rebels were unaware

of each other’s efforts, but those in charge of keeping global order knew when

rebellions broke out on several continents within the same years or decades.

These periods in which collective unrest cluster in time are called “world

revolutions” by the world-systems scholars (Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein

1989). These semi-synchronized waves of resistance

can be labeled by pointing to the symbolic years that connote the general or

average nature of the movements – 1789 (the American, French. Bolivarian and

Haitian revolutions); 1848—(the “Springtime of Nations” plus the Taiping

Rebellion in China; 1917 – (the Mexican, Chinese and Russian revolutions); 1955

– (the anti-colonial revolts and the non-aligned movement at the Bandung Conference);

1968—(the student rebellions) 1989—(the demise of and reformation communist

regimes); and the current period of global unrest that seemed to have peaked in

2011

(Chase-Dunn and Niemeyer 2009). These complex “events” had important

consequences for both reproducing and restructuring the modern world-system.

Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein (1989) notice a pattern in which enlightened

conservatives try to coopt powerful challenges from below by granting some of

the demands of earlier world-revolutions. This has been an important driving

force toward democracy and equality over the past several centuries.

The modern system is multicultural in

the sense that important political and economic interaction networks connect

people who have very different languages and religions. Most earlier world-systems have also been

multicultural. There is, however, an emerging global culture that is produced

by the interaction of all the subcultures. It is a contentious mix that tends

to be dominated by the national and civilizational cultures of the core states,

but it is also an outcome of global communications and contentious resistance

(Meyer 2009). Immanuel Wallerstein (2001b) uses the term “geoculture” for the

predominant political ideology of centrist liberalism.

The

Comparative World-Systems Theoretical

Research Program (TRP)

Both the long cycle approach and the

world-systems perspective have adopted a very long-term framework that seeks to

explain sociocultural evolution over very long periods of time. George Modelski’s (1964) article on Khautyla

compares the institutional nature of the historically-known South Asian

interstate system with the institutions that emerged in the European system

with the treaty of Westphalia in 1648. The comparative and evolutionary world-systems

TRP explicitly employs an anthropological framework of comparison to examine

polities, settlements and interpolity system since the Stone Age. World-systems are defined in this approach

as systemic interaction networks in which regularized exchanges occur among formally

autonomous, but interdependent, polities.

World-systems are understood to be networks

of interacting polities. Systemness

means that these polities are interacting

with one another in important ways – interactions are two-way, necessary,

structured, regularized and reproductive. Systemic interconnectedness exists

when interactions importantly influence the lives of people within the

connected polities, and are consequential for social continuity or social

change.

Earlier regional world-systems did

not cover the entire surface of the planet. The word “world” refers to the

importantly connected interaction networks in which people live, whether these

are spatially small or large. Only the

modern world-system has become a global (Earth-wide) system composed of a

network of national states. It is a single economy composed of international

trade and capital flows, transnational corporations that produce products on

several continents, as well as all the economic transactions that occur within countries and at local

levels. The whole world-system is more

than just international relations. It is the whole system of human

interactions. The contemporary world economy is all the economic interactions

of all the people on Earth, not just international trade and investment.

When we discuss and compare different

kinds of world-systems it is important to use concepts that are applicable to

all of them. Polity is a general

term that means any organization that claims sovereign control over a territory

or a group of people. Polities include bands, tribes and chiefdoms as well as

states and empires. All world-systems are politically composed of multiple

interacting polities. Thus we can fruitfully compare the modern interstate

system with earlier systems in which there were tribes or chiefdoms, but not

states.

The modern world-system is structured

politically as an interstate system – a system of competing and allying states.

Political Scientists commonly call this “the international system”, and it is

the main focus of the field of International Relations. Some of these states

are much more powerful than others, but the main organizational feature of the

world political system is that it is multicentric.

There is no world state. Rather there is a system of states. This is a

fundamentally important feature of the modern system and of many earlier

regional world-systems as well.

The comparative world-systems

approach developed by Chase-Dunn and

Hall (1997; see also Chase-Dunn and Jorgenson 2003) notes that different kinds

of important interaction have different spatial scales. For all systems there

is a relatively small network of the exchange of basic foods and raw materials.

This is often smaller than the network of polities that are making war and

alliances with one another. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) call this the

Political/Military Network (PMN). This is the general equivalent of the modern

international system except that the polities may be tribes or chiefdoms rather

than states. The PMN is often smaller than the network of exchange of prestige

goods, valuables that move long distances and that may or may not be important

in the reproduction or change of local social structures.

The comparative evolutionary

world-systems theoretical research program uses David Wilkinson’s (1987) spatio-temporal

bounding of PMNs, which Wilkinson calls “civilizations.” This approach

delineates the spatial and temporal boundaries of networks of cities and states

that are making war and alliances with one another, beginning with the

Mesopotamian and Egyptian PMNs in the early Bronze Age. Wilkinson’s chronograph

shows that these two separate state systems merged with one another in the

decades around 1500 BCE forming a larger network that eventually expands to

include all the other networks and constituting the modern global system.

So

the modern world-system is now a global economy with a global political system

(the interstate system). It also includes all the cultural aspects and

interaction networks of the whole human population of the Earth. Culturally the modern system is composed of:

·

several civilizational

traditions, (e.g. Islam, Christendom, Hinduism, Confucianism, Secular Humanism,

etc.)

·

nationally-defined cultural

entities -- nations (and these are composed of class and functional

subcultures, e.g. lawyers, technocrats, bureaucrats, etc. , and

·

the cultures of indigenous and

minority ethnic groups within states.

While a global culture is in

formation it is important to note that the modern world-system is not primarily

integrated by normative consensus. The strongest forces producing social order

are states and markets (Chase-Dunn 1998: Chapter 5) and these are important

precisely because they do not require high levels of consensus about what

exists and what is good.

Chase-Dunn

and Hall (1997) allowed for the possibility that some world-systems did not

have core/periphery hierarchies. They also point to a general pattern that

occurred once world-systems became hierarchical -- a cycle of the rise and fall

of more powerful polities similar in some respects with the long cycle in the

modern system (Anderson 1994). They also

noted some emergent characteristics that qualitatively altered the ways in

which military and economic power operated as these systems became larger and

more complex.

Certain processes operate in all human world-systems

large and small, at least so far. Demographic cycles occur within polities and

in whole world-systems, and these both drive and are driven by changes in

technology, political organization and economic networks. Chase-Dunn and Lerro

(2014: Chapter 2) present a recent version of the “iteration model” first

proposed by Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997: Chapter 6). This model proposes a

positive feedback loop in which population growth causes population pressure,

which causes migration until the land is filled up with humans (circumscription[Carneiro

1970]) which then causes within polity and between-polity conflict to rise,

lowering population pressure by killing off people. Some systems escape this

demographic regulator by forming larger polities and by increasing trade and

production. But this then allows for more population growth so the process goes

around again.

Institutions

such as states, cities, empires, markets and international organizations emerge

that alter the ways in which cooperation, competition and conflict shape the

emergence of larger and more complex systems. In both the long cycle and

world-systems approaches governance is understood to refer to those

institutions that structure the order of an interpolity system. So global governance in the modern system is

provided primarily by the process of the rise and fall of system leaders – or

hegemons. The nature of the polities and the nature of interpolity relations

are important, as are whatever suprapolity institutions and structures may

exist. In this sense, “global governance” can be understood as having evolved

in interpolity systems since the Stone Age.

The comparative world-systems TRP

studies how core/periphery hierarchies emerged and evolved. Chase-Dunn and Mann

(1998) showed that regional inequalities were mild in a small-scale

world-system that existed in Northern California before the arrival of the

Europeans. Though there was territoriality, there was little in the way of

exploitation or domination by powerful polities of weaker adjacent

polities. But as polities became

internally more hierarchical core/periphery exploitation emerged. Indigenous paramount

chiefdoms on the Chesapeake Bay extracted tribute from neighboring polities (Rountree

1993). Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) note an important aspect of sociocultural

evolution that cannot be well-studied by focusing on the great powers alone.

They notice the phenomenon of semiperipheral development in which polities

located in semiperipheral positions within core/periphery structures often play

important roles in transforming the scale and institutional nature of

world-systems. They designate and study

several different kinds of semiperipheral development: semiperipheral marcher

chiefdoms, semiperipheral marcher states, semiperipheral capitalist

city-states, the semiperipheral position of Europe and the Afroeurasian

world-system prior to the rise of the West, the semiperipheral position of the

modern hegemons prior to their rise to hegemony (the Dutch in the 17th

century; The British in the 19th century and the United States in

the 20th century) (see also Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014). It is semiperipheral development that best

explains the spatial movement of the cutting edge of complexity and hierarchy

that occurred as world-systems got larger.

Empirical Studies of Upsweeps in

World-Systems

Our research on the upsweeps[5]

in the territorial sizes of largest polities[6]

and the population sizes of largest cities[7]

since the Bronze Age is germane to testing competing hypotheses about the

causes of long-run trends in the formation of complexity and hierarchy

(Chase-Dunn et al. 2006).[8] We have conducted a series of quantitative

studies that have identified those instances in which the scale of polities and

cities significantly changed (upsweeps and downsweeps) Inoue et al 2012; Inoue et al 2015) and we have begun testing the hypothesis that these

scale changes were caused by semiperipheral marcher states (Inoue et al 2016). We contend that polities in

semipeiphery have been in fertile locations for implementation of

organizational and technological innovations that have transformed the scale and

sometimes the logic of world-systems (Inoue et

al. 2016). Semiperipheral polities enjoy geopolitical advantages

(the marcher state advantage of not having to defend the rear) and “advantages

of backwardness” such as less sunk investment in oldr organizational forms; less

subjection to core power relative to peripheral polities; and greater incentives

to take risks on innovations and new institutional development.

Upsweeps in the territorial size of the largest polity in an

interpolity system can occur when one of the states conquers the others to form

a larger polity. We try to determine whether or not the conquering state had

previously been in a semiperipheral or peripheral location within the regional

interpolity system. [9]

In our studies of upsweeps and non-core

marcher states we examined four regional world-systems (Mesopotamia, Egypt,

East Asia, and South Asia) as well as the expanding Central political/military

network that is designated by David Wilkinson’s (1987) temporal and spatial

bounding of state systems since the Bronze Age. This produced a list of

twenty-one territorial upsweeps.

The results of the study showed that

out of twenty-one cases of territorial upsweeps, ten cases were produced by

semiperipheral marcher states, and three cases were by peripheral marcher

states (Inoue et al. 2016). So about a half of the examined cases of territorial

upsweeps were caused by conquests by noncore marcher states and the other half

were not. This means that the hypothesis of noncore development does not

explain everything about the events in which polity sizes significantly

increased in geographical scale, but also that the phenomenon of noncore

development cannot be ignored in any explanation of the long-term trend in the

rise of polity sizes. We

characterized the events not caused by non-core marcher states as follows: 1.

mirror-empires -- a core state that was under pressure from a non-core polity

carried out a territorial expansion; 2. An internal revolt -- a new regime was formed by an internal ethnic

or class rebellion; and 3. internal

dynastic change -- a coup carried out by

a rising faction within the ruling class of a state led to a territorial

expansion (Inoue et al. 2016). These were instances in which processes

internal to existing core states were important causes of territorial

expansion. We also found that nine of the eighteen urban upsweeps were

produced by noncore marcher state conquests and eight directly followed, and

were caused by, upsweeps in the territorial sizes of polities (Inoue et al 2015). Whereas about half of the upsweep events were

caused by one or another form of non-core development, there were a significant

number of upsweep events in which the causes seem to be substantially internal (Inoue et al. 2016).

Thus what is needed is a multilevel model in

which processes that occur within polities are linked with processes occurring

between polities. Such a model would have important implications for debates in

international relations theory as well as for interdisciplinary approaches to

explaining sociocultural evolution.

A Multilevel Model of World-Systems

Evolution

The world-system perspective tends to focus on the network

and relational dynamics that are external to single polities despite occasional

holistic claims (above) that the contemporary system is composed of all the

individuals on Earth and is more than international relations. The findings of our studies of upsweeps

suggest that we need to examine both within-polity and between-polity as well

as whole system variables simultaneously in a multilevel model. In searching

for models of processes occurring within polities we are inclined to turn to the

structural demographic approach developed by Jack Goldstone (1991) and

elaborated and tested by Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefadov (2009). We are also

encouraged by Jack Goldstone’s (2014) studies of social movements and revolutions to

include these in our multilevel model of sociocultural evolution. Additionally,

our overall scheme for integrating both within-polity, between-polity and

system-level dynamics is inspired by the ecological models of the multilevel panarchy

theory (Green et al 2015; Gotts 2007;

Gunderson and Holling 2002; Holling 1973). Peter Turchin’s (2003) modified model of Ibn Khaldun’s

explanation of dynastic cycles and the long cycle approach of Modelski and

Thompson (1996) are also inspirations for our new (revised) model. We will also incorporate insights from Victor

Lieberrman’s (2003, 2009) studies of state formation in South East Asia and his

comparisons with similar processes in other regions.

Structural demographic theory

Jack Goldstone (1991) formulated the

first version of what has become known as the structural-demographic theory of

state collapse. Demographic growth causes population pressure on resources and

this results in fiscal problems for the state, which leads to increasingly

violent competition among elites and popular rebellion (see also Turchin 2016b). The theory has been respecified as a “secular

cycle” by Turchin and Nefadov (2009) and empirically verified by historical comparative

studies (Turchiin and Nefadov 2009; Korotayev et al. 2011; Korotayev et al

2015). Goldstone’s original model and

the succeeding models developed out of it have shown that the internal dynamics

of state breakdown and regime change involve revolutions, civil wars, dynastic

conflicts other outbreaks of social and political instability caused by

within-polity population growth.

Along with the internal dynamics specified

by structural-demographic theory, Peter Turchin’s (2006) model includes an

external mechanism that causes the emergence of large-scale empires. This model describes how variations in

within-polity solidarity were caused by inter-polity competition. The model uses the ethnic frontier theory of

Ibn Khaldun to contend that large-scale empires emerge on meta-ethnic frontiers

because intense competition between ethnically different groups produced higher levels of solidarity that

unified groups. The model also includes the

evolutionary adaptation theory proposed by Richardson and Boyd (2005) and

argues that the intense competition produced by interpolity warfare operated as

a selection mechanism that promoted the emergence of groups that had adaptive

advantages based on higher levels of solidarity and within-group cooperation. Groups with greater solidarity and

cooperation develop complex and large polities.[10] As in the long cycle approach of Modelski and

Thompson (1988, 1996), war is a selection mechanism that promotes the formation

of more powerful, more complex and more hierarchical polities.[11]

Panarchy

The panarchy approach has come to be

well-known as conceptual framework that seeks to bridge ecological and social

science explanations since the 1970s (Simon 1962; Hollings 1973). The framework has often been used to produce

analogies from ecology to explain complex social systems in social

science. Research inspired by the panarchy

model is similar in many respects to the world-systems approach. It employs a

nested multilevel analytical framework with cyclical processes to study the

emergence and transformation of complex systems (Gotts 2007; Gunderson and

Hollings 2002; Odom Green et al

2015). The panarchy model employs a holistic structure that integrates

ecological, social, and economic processes of stability and change.

The panarchists assert that a whole

system is more than the sum of its parts and that whole systems are often complex,

hierarchical and dynamic. Herbert Simon’s

(1962) classical formulation of adaptive hierarchical multilevel organizations laid

the foundation for the development of the panarchy tradition. Panarchy involves

partially autonomous and distinct nested levels that are formed from the

interactions among sets of variables operating at each level. Unlike the hierarchical structure of a

top-down authoritative control structure, Simon asserted that each level has

its own speed of change—smaller local levels change faster; larger and global

levels change more slowly and transformations can occur at each level without

affecting the integrity of the whole system.

Such adaptive hierarchical systems with partial autonomy of subsystems are

claimed to evolve faster than systems that have a single vertical hierarchical

structure (Simon 1962).

In the panarchy model, the smaller

levels have an impact on the larger level in the form of "revolts" in

which local events overwhelm larger level dynamics. Larger level dynamics set conditions for the

smaller level events by means of “remember” in which the accumulated structure

at the larger level impacts the reorganization of lower level events (Gunderson

and Hollings 2002). Resilience, or the

capacity of a system to tolerate disturbances, allows the system to avoid

collapse (Gunderson and Hollings 2002).

When the system goes beyond its resilience point its capacity to absorb

change is exceeded. Then the system is

likely to cross a threshold and to reorganize into a regime with a new set of

processes, feedbacks, and structures (Odom et

al. 2015).[12]

Non-core development, long cycles, the

secular cycle and world revolutions

Insights from the structural demographic (secular cycle) and

panarchy approaches can be combined with the world-system iteration model and

the non-core development hypothesis to produce a new synthetic multilevel model

of sociocultural evolution. The within-polity

dynamics of the structural-demographic model should help account for those

upsweep instances that do not involve conquests by non-core marcher states by

taking account of within-polity population pressures, fiscal crises,

intra-elite competition, social movements and political instability that have

led to state collapse and recoveries that have led to upsweeps. Some of these

variables are likely to operate both within and between polities. Social

movements, rebellions, and incursions from the non-core may cluster in time. World

revolutions have been conceptualized and studied only with respect to the

modern Europe-centered system (Chase-Dunn and Khutkyy 2016). But other studies indicate that earlier

regional world-systems also experienced periods in which collective behavior

events clustered during the same time periods with consequences for the whole

system (Thompson and Modelski 1998b). We are optimistic that a new synthetic

theory of sociocultural evolution that combines the insights

and research results from these approaches is nigh.

Bibliography

Amin, Samir

1980. Class and Nation, Historically and in the Current Crisis. New

York: Monthly Review Press.

Anderson,

David G. 1994 The Savannah River Chiefdoms: Political Change in the Late

Prehistoric Southeast. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Anderson, E. N. and Christopher

Chase-Dunn “The Rise and Fall of Great Powers” in Christopher

Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) 2005. The Historical Evolution of World-Systems. London: Palgrave.

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994. The

Long Twentieth Century. London: Verso.

______________ 2008 Adam

Smith in Beijing. London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni 2006 “Spatial and other ‘fixes’ of

historical capitalism” Pp. 201-212 in C. Chase-Dunn and

S. Babones (eds.) Global Social Change. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni,

Terence Hopkins and Immanuel Wallerstein 1989 Antisystemic Movements. London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni,

Silver, Beverly J., ‘Introduction’, In Arrighi, G., Silver, B.J., et al, Chaos

and Governance in the Modern World-System (Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1999), 1-36.

Beaujard, Philippe. 2010. “From Three possible

Iron-Age World-Systems to a Single Afro-Eurasian World-System.” Journal

of World History 21:1(March):1-43.

Boswell,

Terry and Mike Sweat 1991 “Hegemony, long waves and major wars: a time series

analysis of systemic dynamics, 1496-1967” International

Studies Quarterly 35,2: 123-150.

Boswell, Terry, and Chase-Dunn, Christopher, The Spiral of

Capitalism and Socialism: Toward Global Democracy (Boulder: Lynne Reinner

Publishers, 2000).

Braudel, Fernand

1984. The Perspective of the World, Volume 3 of Civilization

and Capitalism. Berkeley: University of California Press

Carneiro, Robert L. 1970. "A theory of the origin of

the state," Science 169: 733-38.

Chase-Dunn, C.. 1998. Global Formation: Structures of the World-Economy. Lanham, MD:

Rowman and Littlefield.

Chase-Dunn, C. 1988. "Comparing world-systems:

Toward a theory of semiperipheral development," Comparative

Civilizations Review, 19:29-66, Fall.

____________ 2006

“Globalization: A world-Systems perspective” Pp. 79-108 in C. Chase-Dunn and S.

J. Babones (eds.) Global Social Change Historical and Comparative Perspectives

Baltimore MD: Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise

and Demise: Comparing World-Systems Boulder, CO.: Westview Press.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and E.N. Anderson (eds.) 2005.

The Historical Evolution of

World-Systems. London: Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Richard Niemeyer and Juliann Allison. 2006. "Futures of

biotechnology and geopolitics" IROWS Working Paper # 23

Chase-Dunn, C. and Andrew K.

Jorgenson 2003 “Regions and Interaction Networks: an

institutional materialist perspective,” International Journal of

Comparative Sociology 44,1:433-450.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and R.E. Niemeyer. 2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” Pp. 35-57 in

Mathias Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.).

Transnational Political Spaces.

Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/New York.

Chase-Dunn, C, E. N. Anderson, Hiroko Inoue and

Alexis Álvarez 2015 “The Evolution of Economic

Institutions: City-states and forms of imperialism

since the Bronze Age” IROWS Working Paper #79 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows79/irows79.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence and Hiroko Inoue 2011 ‘Last of the Hegemons: U.S.

Decline and Global Governance’ International Review of Modern Sociology,

37: 1-29.

Chase-Dunn, C and Bruce Lerro 2014 Social

Change: Globalization from the Stone Age to the Present. Boulder,

CO: Paradigm

Chase-Dunn, C. and Kelly M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and

Their Neighbors. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Dmytro Khutkyy. 2016.

"The Evolution of Geopolitics and Imperialism in Interpolity Systems"

Institute for Research on World-Systems, Working Paper #93 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows93/irows93.htm

Cioffi-Revilla,

Claudio 1996 ”The origins and evolution of war and politics” International

Studies Quarterly 40:1-22.

Ekholm, Kasja and Jonathan

Friedman 1982 “’Capital’ imperialism and exploitation in the ancient world-systems” Review 6:1

(summer): 87-110.

Ekholm, Kasja and Jonathan

Friedman 1982 “’Capital’ imperialism and exploitation in the ancient world-systems” Review 6:1

(summer): 87-110.

Fletcher, Jesse B; Apkarian, Jacob; Hanneman, Robert A;

Inoue, Hiroko; Lawrence, Kirk; Chase-

Dunn,

Christopher. 2011 ”Demographic Regulators in

Small-Scale World-Systems” Structure

and Dynamics 5,

1

Frank, Andre Gunder, and Barry K. Gills eds.1993 ‘The 5,000-Year

World System: An Interdisciplinary Introduction’, In A.G. Frank and B.K. Gills,

eds., The World System: Five Hundred Years or Five Thousand? (London:

Routledge, Pp. 3-55.

Friedman, Jonathan and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds) 2005. Hegemonic decline: present and past.

Boulder: Paradigm Publishers

Gills,

Barry K. and William R. Thompson (eds.) 2006. Globalization and Global History.

London: Routledge.

Goldstone, Jack. 1991. Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern

World. Berkeley: University of California Press

_______________2014 Revolutions. New York: Oxford

University Press

Gotts,

Nicholars M. 2007. "Resilience, Panarchy, and World-Systems Analysis"

Ecology and Society 12(1):24

Gowdy, John, and Lisi Krall 2015 "The

economic origins of ultrasociality."Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22): 1-63.

Gunderson, Lance and C. S. Holling.

2002. Panarchy: Understanding

Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington: Island Press.

Hall, Thomas D., Christopher Chase-Dunn and Richard Niemeyer. 2009

“The Roles of Central Asian Middlemen and Marcher States in Afro-Eurasian

World-System Synchrony.” Pp. 69-82 in The Rise of Asia and the

Transformation of the World-System, Political Economy of the World-System

Annuals. Vol XXX, edited by Ganesh K. Trinchur. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Press

Holling

C. S. 1973. “Resilience and stability of ecological systems.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics.

4: 1–23.

Hopkins, Terence and Immanuel Wallerstein 1979 “Cyclical rhythms

and secular trends of the capitalist world-economy” Review 2,4:483-500

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Kirk Lawrence,

Anthony Roberts, Eugene N Anderson and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2012 “Polity scale shifts in

world-systems since the Bronze Age: A comparative inventory of upsweeps and collapses” International

Journal of Comparative Sociology http://cos.sagepub.com/content/53/3/210.full.pdf+html

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Eugene N. Anderson, Andrew

Owen, Rebecca Álvarez, Kirk Lawrence and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2015 “Urban

scale shifts since the Bronze Age: upsweeps, collapses and semiperipheral

development” Social Science History Volume 39 number 2, Summer

Inoue,

Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, E.N. Anderson, Kirk Lawrence, Teresa Neal, Dmytro

Khutkyy, Sandor Nagy, Walter DeWinter and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2016.

"Comparing World-Systems: Empire Upsweeps and Non-core marcher states

Since the Bronze Age" http://ierows.ucr.edu/papers/irows56/irows56.htm

Kardulias, P, Nick. 2014. “Archaeology and

the Study of Globalization in the Past.” Journal

of Globalization Studies 5:1(May

2014):110-121.

Kennedy, Paul. 1987 The Rise

and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Random House.

Kirch, Patrick V. 1991. "Chiefship and Competitive Involution: the

Marquesas Islands of Eastern Polynesia." Pp. 119-145 in Chiefdoms:

Power, Economy and Ideology, edited by Timothy Earle. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Korotayev,

Andrey, Jack A. Goldstone, and Julia Zinkina. 2015. "Phases of global

demographic transition correlate with phases of the Great Divergence and Great

Convergence." Technological

Forecasting and Social Change. 95 (June):163–169.

Korotayev,

A., J. Zinkina, S. Kobzeva, J. Bozhevolnov, D. Khaltourina, A. Malkov, and S.

Malkov. 2011. A Trap at the Escape from the Trap? Demographic-Structural

Factors of Political Instability in Modern Africa and West Asia. Cliodynamics

2:276–303.

Lakatos, Imre 1978 The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes V. 1 Edited by

John Worrall and

Gregory

Currie. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levy, Jack L. and William R. Thompson 2011 The Arc of

War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lieberman, Victor. 2003. Strange Parallels: Southeast

Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830. Vol. 1: Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

______________ 2009. Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia

in Global Context, c. 800-1830. Vol 2: Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the

Islands. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Mann, Michael. 1986. The Sources of Social Power Volume

I: A History of Power From the Beginning to A.D. 1760. New

York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

____________

2013 The Sources of Social

Power, Volume 4: Globalizations, 1945-2011. New York: Cambridge University

Press.

Mann,

M. 2016 “Have human societies evolved? Evidence from history and

pre-history” Theory and

Society 45:203-237.

Meyer, John W. 2009 World Society. Edited by

Georg Krukcken and Gili S. Drori. New

York: Oxford

University Press.

Modelski, George 1964.

"Kautilya: foreign policy and international system in the ancient Hindu

world," American Political Science Review 58, 3: 549-60.

Modelski, George 1987 Long Cycles in World Politics. Seattle: University of Washington

Press.

_______________1990. "Is world politics

evolutionary learning?" International

Organization. 44 (1): 1-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300004628

______________

2005 “Long term trends in world politics” Journal

of World-Systems Research 11,2:195-206.

Modelski, George 2003 World Cities: –3000 to 2000.

Washington, DC: Faros 2000

Modelski, George. 2006.

“Globalization as evolutionary process” in pp. 22-29. Modelski, George, T. Devezas, and W. Thompson (eds.) 2006. Globalization as Evolutionary Process:

Modeling, Simulating, and Forecasting Global Change. London: Routledge.

Modelski, George and William R. Thompson. 1988 Seapower in Global Politics, l494-1993 Seattle, WA.: University of Washington Press.

Modelski, George and William R. Thompson 1996. Leading Sectors and World Powers: the Coevolution of Global Economics

and Politics. Columbia: University

of South Carolina Press.

Modelski, George, T. Devezas, and W. Thompson (eds.) 2006 Globalization as Evolutionary Process:

Modeling, Simulating, and Forecasting Global Change. London: Routledge.

Morris, Ian 2010 Why the

West Rules—For Now. New York: Farrer, Straus and Giroux

______ 2013 The Measure

of Civilization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Morris, Ian. 2014. War! What Is It

Good For?: Conflict and the Progress of Civilization from Primates to Robots.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Nassaney,

Michael S. and Kenneth E. Sassaman (eds.) 1995 Native American Interactions

: multiscalar analyses and interpretations in the eastern woodlands.Knoxville : University of Tennessee Press

Odom,

Olivia, Green, Ahjond S Garmestani, Craig R Allen, Lance H Gunderson, JB Ruhl,

Craig A Arnold, Nicholas AJ Graham, Barbara Cosens, David G Angeler, Brian C

Chaffin, and CS Holling. 2015. "Barriers and bridges to the integration of

social–ecological resilience and law" Frontiers

of Ecological Environment. 13(6): 332–337

Parsons, Talcott. 1966. Societies:

Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

_________ 1971 The System of Modern Societies.

Rasler, Karen A. and William Thompson. 1994. The Great Powers and Global Struggle: 1490 1990. Lexington:

University Press of Kentucky.

Rennstich,

Joachim K. 2001 “The Future of Great Power Rivalries.” In Wilma Dunaway (ed.) New

Theoretical Directions

for the 21st Century World-System New York: Greenwood Press.

Reuveny,

Rafael and William. 2007. R. Thompson

(eds.) North and South in the Global Political Economy. Cambridge, MA:

Blackwell.

Richerson, Peter J. and Robert Boyd. 2005. Not by Genes Alone: How culture transformed human evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Rountree, Helen C. (ed.) 1993 Powhatan

Foreign Relations, 1500-1722 Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Sanderson, Stephen K. 1990 Social

Evolutionism: A Critical History.

SESHAT: Global History Databank http://evolution-institute.org/seshat

SetPol Project. The Research Working Group on Settlements and

Polities, Institute for Research on World-Systems, University of California- Riverside

https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/citemp.html

Simon, Herbert A. 1962. "The Architecture of Complexity" Proceedings of the American Philosophical

Society. l(106,No. 6): 467-482.

Spencer, Herbert. 1898. The

Principles of Sociology, 3 vols.

http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/spencer-the-principles-of-sociology-3-vols-1898

Taagepera, Rein 1978a "Size and duration of empires:

systematics of size" Social Science Research 7:108-27.

______ 1978b "Size and duration of empires:

growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600 B.C." Social Science Research, 7 :180-96.

______1979 "Size and duration of empires:

growth-decline curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D." Social Science History 3,3-4:115-38.

_______1997 “Expansion and contraction patterns of large

polities: context for Russia.” International Studies Quarterly 41,3:475-504.

Thompson, William R. 1990 "Long waves, technological innovation and

relative decline." International

Organization. 44:201-33.

Thompson, William R. 1995.

"Comparing World Systems: Systemic Leadership Succession and the

Peloponnesian War Case." Pp. 271-286 in The Historicial Evolution

of the International Political Economy, Volume 1, edited by

Christopher Chase-Dunn. Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar.

Thompson, William R. 2000 The Emergence of the International Political Economy. London:

Routledge.

Thompson, William R. (ed.) 2001. Evolutionary

Interpretations of World Politics. London: Routledge.

Thompson,

William R. 2002 “Testing a Cyclical Instability Theory in the Ancient Near

East.”

Comparative Civilizations

Review 46 (Spring): 34-78.

__________________

2004 “Eurasian C-Wave Crises in the First Millennium B.C.E.,” in Eugene

Anderson

and Christopher Chase-Dunn, eds., The Historical Evolution of

World-Systems New

York:

Palgrave-Macmillan

___________________

2004 “Complexity, Diminishing Marginal Returns, and Fragmentation in

Ancient Mesopotamia.” Journal of World-Systems

Research 10, 3; 613-652.

Thompson, William R. (ed.) 2006. Globalization and Global History.

London: Routledge.

Thompson,

William R. 2006 “Early Globalization, Trade Crises, and Reorientations in the

Ancient

Near

East,” Pp. 33-59 in Oystein S. LaBianca and

Sandra Schram (eds.), Connectivity in

Antiquity:

Globalization as Long-term Historical Process. London:

Equinox

__________________

2006 ”Crises in the Southwest Asian Bronze Age.” Nature and Culture

[Leipzig]

1:88-131.

__________________

2006 “Climate, Water and Political-economic Crises in Ancient

Mesopotamia

and Egypt,” in Alf Hornborg and Carole Crumley,eds., The

World System and

the Earth

System: Global Socio-environmental Change and Sustainability Since the

Neolithic. Oakland, Ca.: Left Coast Books

Thompson,

W.R. 2008 "Synthesizing Secular, Demographic-Structural, Climate, and

Leadership Long Cycles: Explaining Domestic and World Politics in the Last Millennium."

in The Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association. San Francisco.

Thompson, William R. 2017

Introduction. Oxford Encyclopedia of Empirical International Relations

Theories

New York: Oxford University Press

___________________ and

Andre Gunder Frank 2005 “Bronze Age Economic Expansion and

Contraction Revisited.” Journal of World History 16,

2: 115-72

_______________________________________

2006 “Early Iron Age Economic Expansion and

Contraction

Revisited,” in Barry K. Gills and William R. Thompson (eds.), Globalization

and

Global

History. London: Routledge

________________

and George Modelski 1998 “Pulsations in the World System: Hinterland to Center

Incursions and Migrations, 4000 B.C. to 1500 A.D.,” in Nicholas Kardulias

(ed.), Leadership, Production and

Exchange: World Systems Theory in Practice (Boulder, Co: Rowman and

Littlefield,

Turchin,

Peter. 2003. Historical dynamics: why

states rise and fall. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

___________

2007. War and Peace and War: The Rise and

Fall of Empires. Plume.

____________ 2016a Ultrasociety

Chaplin, CT: Beresta Books

____________ 2016b “Intra-elite competition” Cliodynamica

Turchin, Peter and Sergey Nefedov. 2009 Secular

Cycles. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Turchin, Peter, Jonathan M. Adams, and Thomas D.

2006. “East-West Orientation of Historical Empires and Modern

States.” Journal of World-Systems Research. 12:2(December):218-229.

___________ and Sergey Gavrilets 2009

“The evolution of complex hierarchical societies” Social Evolution &

History, Vol. 8 No. 2, September: 167–198.

______________, Thomas E.Currie, Edward A.L. Turner

and Sergey Gavrilets 2013 “War,

space, and the evolution of Old World complex societies” PNAS October vol.

110 no. 41: 16384–16389 Appendix:

http://www.pnas.org/content/suppl/2013/09/20/1308825110.DCSupplemental/sapp.pdf

Turner,

Jonathan H. 1985. Herbert Spencer: A

Renewed Appreciation. Sage Publications.

Turner,

Jonathan H. 2010. Theoretical Principles

of Sociology, Volume 1: Macrodynamics. Springer.

Turner,

Jonathan and Richard Machalek 2017 The

New Evolutionary Sociology: New and Revitalized Theoretical Approaches New

York: Routledge

Wallerstein, Immanuel 1984. "The three instances of hegemony in the

history of the capitalist world-economy," pp. 37-46 in I. Wallerstein

(ed.) The

Politics of the World-Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

__________________ 2006

‘The Curve of American Power’ New Left Review, 40: 77-94.

------------------------------2011a

[1974] The Modern World-System, Vol. 1: Capitalist Agriculture and the

Origins of

the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

------------------------------2011b The

Modern World-System IV: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789-1914 Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Wilkinson, David 1987 "Central

Civilization." Comparative Civilizations Review 17:31-59.

Wohlforth, William C., Richard Little, Stuart J. Kaufman,

David Kang, Charles A Jones, Victoria Tin-Bor Hui, Arther Eckstein,

Daniel Deudney and William L Brenner 2007 “Testing balance of power theory in

world history” European Journal of International Relations 13,2: 155-185.