Social Science and

World Revolutions

Skin for Chispa Voom avatar, Second Life, 2007

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Director of the Institute for Research on World-Systems and

Distinguished Professor of Sociology, University of

California-Riverside

www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/ccdhmpg.htm

draft v. 8-22-2017

7536 words

IROWS Working Paper #121 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows121/irows121.htm

Published in the Journal of

World-Systems Research Voume 23,#2 2017

Interview

with Jeff Kentor and Andrew Jorgenson,

At

the 2014 annual meeting of the American Sociological Association (ASA) I

received a Distinguished Career

Award from the Political Economy of World-Systems (PEWS) section of the ASA. At

the 2015 ASA meeting a session was organized by Jeffrey Kentor in which several

colleagues presented comments on aspects of my academic work. Several of those

presentations were subsequently turned into documents and are included in this

special section of the Journal of

World-Systems Research. I have been asked to comment upon them and I will

also take this opportunity to present a brief overview of my scholarly life

since graduation from high school.

The authors of the comments are all colleagues that study

topics related to my work and whom I have known for many years. They are

Jennifer Bair and Marion Werner, Albert Bergesen, Peter Grimes, Ho-Fung Hung, Andrew Jorgenson, Jeffrey Kentor, John Meyer, Valentine

Moghadam, Michael Timberlake and Jonathan Turner.

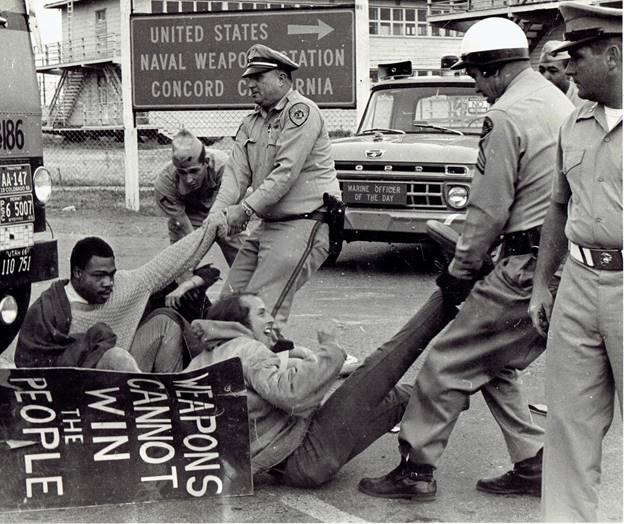

I have been very fortunate to have lived most of my life during the second half of the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st century, which has been a period of relative peace and security in the world, and to have been a middle-class white citizen of the United States. My life in the academy has also been fortunate. After high school, I majored in journalism at Shasta College in Redding, California and then transferred to the University of California at Berkeley in 1964 where I majored in Psychology. At Berkeley I took Collective Behavior from Herbert Blumer and a Social Psychology course from Edward E. Sampson, and I participated in the Free Speech Movement in 1964. In 1966 I applied to the sociology graduate program at Stanford and was accepted. These were the years of what I came later to understand to have been the World Revolution of 1968. I was an activist in the anti-war movement and was arrested at the Concord Naval Weapons Station in Port Chicago, California for stopping napalm trucks (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Stopping Napalm Trucks at the Concord Naval Weapons Station. 1967[1]

In 1969 I dropped out of

the graduate program at Stanford and took a job teaching sociology at Cañada

College in Redwood City, California where I burned my draft card in a pumpkin

with several of my students. I was not rehired when my contract expired and so

I drove my Volkswagen bus to Panama because Che Guevara had said “two, three, many Vietnams.” I organized an anti-war demonstration on the

Canal Zone and fell afoul of the authorities. I was in way over my head and was

lucky to survive the return trip to California. The California Department of

Education tried to revoke my community college teaching credential on grounds

of moral turpitude, citing my arrest at Port Chicago as evidence. My claim to having a good moral character was

entirely based on the fact that I had stopped napalm trucks at Port Chicago. The

hearing officer restored my credential.

After returning from Panama I was

living in San Francisco and driving a truck for the Salvation Army. Stanford Professor John Meyer somehow got my phone number and he called to

encourage me to return to the Stanford graduate program, which I did. I joined a cross-national comparative

research project on the expansion of education and economic development in all

the countries of the world led by Meyer and Mike Hannan (Meyer and Hannan 1979).

My dissertation used this cross-national research design to examine the effects

of dependence on foreign investment on national economic growth and

inequality. It was inspired by Al Szymanski’s Columbia University

dissertation research on the same topic.

I found that countries that had greater dependence on foreign investment

(which later became known as “capital penetration”) grew more slowly and had

more income inequality than countries with less dependence on foreign

investment (Chase-Dunn 1975). I was very fortunate to have John Meyer as my

main mentor, and I also am greatly indebted to Morris

Zelditch, Bernard Cohen and Joseph Berger who taught me the fundamentals of

the comparative method and theory construction which every social scientist

should know.[2] I also formed a lifelong friendship with Al Bergesen, also a graduate student

in sociology at Stanford. And I met Immanuel Wallerstein during his stay at the

Center for Advanced Studies in Palo Alto. And I became life-long friends with Wally Goldfrank, a world-system

sociologist who invited me to teach a course at the University of

California-Santa Cruz in the early 1970s.

In

1975 I moved to Baltimore, Maryland to take a job at Johns Hopkins University.

At first I was half time in Sociology and half time at the Center for

Metropolitan Research, where a colleague, Roger Stough, introduced me to urban

geography. I worked with Ricky Rubinson in Sociology, a fellow

graduate of Stanford, to develop a structural version of world-systems analysis

that combined our Stanford training in theory and quantitative methods with the

ideas coming from the progenitors of world-systems analysis – Immanuel

Wallerstein, Samir Amin, Andre Gunder Frank and Giovanni Arrighi.

I also became friends with Marxist Geographer David

Harvey

and joined his “Reading Capital” seminar.

The American Sociological Review

published an article in which I summarized the findings of my dissertation and

I began a long and fruitful collaboration with Volker Bornschier of the University of

Zurich. Our book Transnational Corporations and Underdevelopment, was published in 1985.

In 1975 Volker and I attended a conference at the Rockefeller Bellagio

Center

on Lake Como in Italy at the invitation of Neil Smelser (seated in the center in Figure 2) and Harry Makler (seated at the far

left). The meeting was organized by the Research Committee on

Economy and Society

(RC02) of the International Sociological Association. Brazilian Sociologist

(and later President of Brazil) Fernando Henrique Cardoso (seated next to Smelser

in Figure 2) was in attendance, as was Alberto Martinelli (later to be president

of the International Sociological Association). Alberto is seated to the left

of Barbara Stallings. Arnaud Sales is seated at the far

right, and I am next to him (eyes closed). Volker is standing second from the

far right.

In

1979 I received a research grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to

study the growth of cities in all the countries of the world over the past 200

years in order to examine the development of urban

primacy in national city systems. In the

later 1970s I also began to regularly attend the conferences of the

International Studies Association and the read the works of international

relations scholars and to formulate my version of the world-systems perspective

in interaction with them (e.g. Chase-Dunn 1981). The work of George Modelski

and William R. Thompson was especially important despite our very different

sets of intellectual ancestors (Chase-Dunn and Inoue, Forthcoming).

In

1985 I finished writing Global

Formation

and in 1989 it was published by Basil

Blackwell. It presented a structural and semi-formalized version of the world-system

perspective.[3]

In Chapter 10 there is a section (p.

214) in which I assert that the search for distinct boundaries between the core

and the semiperiphery and the semiperiphery and the periphery is a pointless

exercise because the core/periphery hierarchy is really a set of continuous

distributions of different kinds of economic and military power. The

categorical terms are heuristic ways of pointing to the top, the middle and the

bottom of a set of continuous distributions. Despite that extensive literature,

beginning with Arrighi and Drangel (1986) that searches for, and often finds,

gaps between the “zones” there is no theoretical explanation of what would

produce these gaps. The fact that there has been some upward and downward

mobility means that regions occasionally will have passed through the gaps. I

stick with my contention that the global stratification system is a set of

continuous hierarchical dimensions.

While

writing Global Formation I became

interested in the possibility of comparing the modern whole world-system with

earlier smaller systems – cross-world-system studies. And the first version of

what later became formulated as the semiperipheral development hypothesis

occurred to me (Chase-Dunn 1990; see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 5).

Figure 2: Bellagio

RC02 Conference, 1975

In 1994 Salvatore

Babones, Susan Manning, Tom Brown and I founded the Journal of

World-Systems Research,[4]

an open-access electronic journal that eventually became the official journal

of the Political Economy of World-Systems (PEWS) section of the American

Sociological Association. It was in this period that Tom Hall and I turned toward the comparison of the modern

system with earlier regional world-systems. Our book, Rise and Demise was published in 1997. It retooled the concepts

that had been developed to comprehend the modern system for the larger job of

comparing world-systems[5]

and we developed a general iteration model[6]

to explain the spirals of size and complexity that have occurred in

world-systems since the Stone Age. In

1991 I got another NSF grant to study small world-systems and in 1998 The Wintu

and Their Neighbors: A Very Small World-System in Northern California (with Kelly Mann) was

published by the University of Arizona Press. We used ethnographic and

archaeological evidence to examine the nature of a small system in which the

interacting polities were all village-living hunter-gatherers. My collaboration

with Terry Boswell led to the publication of our Spiral of Capitalism and Socialism in 2000 (Lynne Rienner)

in which we added a series of “World Revolutions” [7]

to our model of the evolution [8]

of the modern world-system. Yukio Kawano, Ben Brewer and I did research on

waves of trade globalization, which was published in the American Sociological Review in 2000.[9]

I was also fortunate that Stephen Bunker came to my Department at

Johns Hopkins. He and Alejandro Portes and Maria Patricia

Fernandez-Kelly were

great colleagues during those years. Beverly Silver and Giovanni Arrighi came later from

Binghamton and the Hopkins Sociology Department became an important node in the

scattered world of world-systems research.

In 2000 I moved to the University of

California-Riverside (UCR) to found the Institute for Research on

World-Systems (IROWS).[10] Andrew Jorgenson and I worked together

with other graduate and undergraduate students at UCR to produce more studies

of the trajectory of investment

globalization

and the rise and fall of the

Dutch, British and U.S. hegemonies. In 2005 Peter

Turchin

and I got a National Science Foundation grant to study global state formation. Beginning soon after I

arrived in Riverside, the Settlements and Polities (SetPol) Research Working Group has been

quantitatively studying the growth of cities and empires since the Bronze Age.[11]

Alexis Alvarez, Hiroko Inoue, emeritus Anthropology Professor E. N. (Gene) Anderson and many graduate and

undergraduate students at UCR have collaborated on a series of papers produced

by this project. Empirically focusing on the population sizes of the largest

cities and the territorial sizes of the largest polities in political/military

networks and world regions has allowed us to identify those upsweep events in

which the scale of socio-economic and political complexity increased greatly

(Inoue et al 2012; Inoue et al 2015. We have also been able to

ascertain that over half of the urban and polity size upsweeps can be

attributed to the actions of non-core (semiperiphery and peripheral) marcher

states (Inoue et al 2016), a finding

that confirms the necessity of using the world-system as a unit of analysis for

explaining sociocultural evolution.[12]

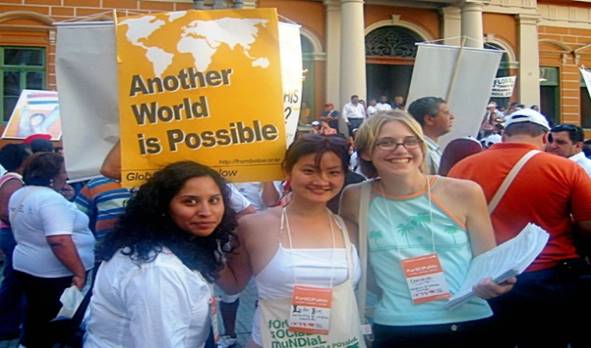

UCR Professor Ellen Reese and I worked with a

large group of graduate and undergraduate students on the Transnational Social Movements Research

Working Group.

We mounted four surveys of attendees at meetings of the World Social Forum in

Porto Alegre, Brazil (see Figure 3) and in Nairobi, Kenya, and at meetings of

the U.S. Social Forum in Atlanta and Detroit (Smith et al 2014). Our surveys discovered a rather stable network of

overlapping social movements that constitute the structure of the global

justice movement (Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro 2008).

Figure 3:

UCR Sociology Graduate Students Erika

Gutierrez, Linda Kim and Christine Petit at the World Social Forum in Porto

Alegre, Brazil 2005

While

still in Baltimore I began working on a textbook for an undergraduate sociology

course on Social Change.[13]

This book, co-authored with Bruce Lerro, finally appeared in

2014. It was originally published by Paradigm Publishers but is now held by

Routledge.[14]

The SetPol project is now working on an

improved version of the iteration model of world-systems evolution first

presented in Chapter 6 in Rise and Demise.

We have made great efforts to spatially

bound whole world-systems.[15] The results of the SetPol project will be

published in a forthcoming monograph.

Commodity

chains and system-wide class relations

Jennifer Bair and Marion Werner’s essay (this section) on

new geographies of uneven development notes

some of the issues on which my theoretical stance differs from other

world-system scholars and addresses several issues that have become important

since the publication of my Global

Formation in 1989. They also read a

1988 essay of mine that cites Trotsky’s ideas of uneven and combined

development in connection with the importance of semiperipheral societies for

the evolution of world-systems.[16]

Bair [17]and

Werner note that my version of class analysis allows for a continuum from

protected to coerced labor with an important sector of protected labor in the

core. The theorists of a global stage of capitalism, starting with Ross and

Trachte (1990), have argued that globalization was causing the

peripheralization of the core as the neoliberal project attacked the welfare

state and labor unions and much of the protected sector was downgraded to the

precariat. Most of this happened after 1985 which was when I finished writing Global Formation. The growing inequality

within the core, as Jen and Marion and others have noted, has important

political consequences and is one of the main forces behind the rise of

right-wing populist movements and parties in Europe and the United States. But

the fat in the system left over from the New Deal reforms and the boom years

after World War II continue to be important factors differentiating the global

core from the non-core. The core has become somewhat peripheralized, but the

differences from the non-core are still significant. Globalization has not

produced a homogenized global class structure in which there is no longer a

core/periphery hierarchy. The world is not flat. As Jen and Marion note, the global class

structure and the core/periphery hierarchy have changed, but huge global

inequalities remain, and continue to be a significant context for both economic

and political developments. The growth

of inequality within the core has produced movements that seem to further

sanctify the rule of capitalist property rather than challenging it. The

growing importance of the color line mentioned by Wallerstein and the increasing

awareness of global inequalities in the core, spurred by mass migration of

economic and civil war refugees, have stimulated racist, nationalist and

zenophobic counter-movements. The potential also exists for an organized

response from unions, displaced workers, oppressed racial and ethnic groups and

environmentalists but the anti-organizational movement culture that has been the

heritage of the New Left in the World Revolution of 1968 undercuts the

emergence of an articulated response from the New Global Left.

A Perfect Storm in Palo Alto

Al

Bergesen’s essay (this section) describes what I

would prefer to call, following Marshal Sahlins, the structure of the

conjuncture. The world revolution of 1968 hit Palo Alto right after the

Sociology Department at Stanford had been restructured around an experimental

theoretical research program inspired by Imre Lakatos’s (1978) philosophy of

science. The Department was strong on sociological social psychology but weak

on macrosociology so they hired John Meyer and Mike Hannan. Out of this conjuncture

came several other major contributions to social science. Buzz Zelditch, Bernie

Cohen and Joe Berger were producing a profound theoretical research program on

status characteristics and expectation states (Berger,

Cohen and Zelditch 1971).

John Meyer

was in the process of formulating his Weberian take on an emerging global culture

that has become known as the world polity or world society perspective (Meyer

2009). Mike Hannan was reinventing Amos Hawley’s human ecology for explaining

the evolution of formal organizations (Hannan and Freeman 1993).

Al Bergesen’s

description of the elements that came together in my dissertation include the

world revolution of 1968, the theory construction approach of the Stanford

graduate program, John Meyer’s quantitative empiricism inherited from Paul

Lazersfeld (which led me to search for a key variable that would capture

international economic dependence) and the panel regression research design

contributed to the Meyer-Hannan cross-national research project by Mike

Hannan. Regarding the key variable, I

came upon Net Factor Income from Abroad in the International Monetary Fund’s Balance of Payments Yearbooks, and

subcategory of this called Debits on Investment Income (DII). Debits on

investment income is an accounting item set up by Harry Dexter White, the main

U.S. organizer of the International Monetary Fund, to help track global

investments. It is a yearly estimate of the amount of profits made on foreign

investments within a national economy. Assuming an average rate of profit, DII

allows for the estimation of the total stock of foreign direct investment

within a national economy. When this is calculated as a ratio to GNP it yields

an estimate of the degree to which a national economy is dependent on foreign

investment—so-called “capital penetration.” I coded DII from the collection of

Balance of Payments Yearbooks at the Stanford Library. Better

operationalizations of investment dependence were to become subsequently

available.

The panel

regression model had been developed by David Heise (1970) in order to

disentangle reciprocal causation in which two variables are causes of one

another. This was the case with both educational expansion and economic

development studied in the Meyer-Hannan project and for my study of investment

dependence and economic growth. Panel regression uses measures at different

time points to separate out the two different causal effects and makes it

possible to examine the effects of different time lags. We found that

investment dependence had short-run positive effects but long-run negative

effects on economic development.

The world

of cross-national quantitative analysis has moved on and the issue of capital

penetration effects has become more complicated. Glenn

Firebaugh’s (1992, 1996) studies claimed to show

that the negative effect of investment dependence on economic growth is a

statistical illusion caused by the fact that the positive effect of foreign

investment on growth is smaller than that of domestic capital investment. Issues about the time lags of effects, the

kinds of penetration that have negative effects and that the negative effects

may vary across time periods and in different world regions, as well as the

important advances that have been made in cross-national quantitative methods,

mean that this subject should be revisited.

Sun Burning Out Like A Match

Peter Grimes’s essay (this section) is a

path-breaking theoretical formulation that describes how complexity theory

explains a great deal about physical, biological and sociocultural evolution.

Peter[18]

focusses on the importance of the

capture and control of energy for the emergence of complexity. He notes that it

is out on the edge between high-energy and low-energy regions that positive

feedback loops allow some entities to climb back up the down staircase of

entropy to erect greater complexity and hierarchy. These are the physical,

biological and sociocultural upsweeps of complexity. With deep knowledge of

both natural and social sciences, Peter is able to discover important

similarities across phase transitions of very different kinds. His scope of

comparison is truly cosmocentric and encompasses what physicists tell us was

the beginning of time (the big bang – the modern creation myth) to the present

and with interesting implications about the future. Peter is working on a book

that will unify science by detailing

the similarities, the differences and the interconnections between phase

transitions. Watch this space.

The Hegemonic Sequence and the Future

of Global Governance

Ho-Fung

Hung’s essay (this section) on hegemonic

transitions and the contemporary geopolitical and geoeconomic situation suggests

that the comparative and evolutionary world-systems perspective may be useful

for understanding the possible forms that global governance may take in the 21st

century. Ho-Fung[19] points

out that Chinese investment in U.S. Treasury Bonds is the major element

supporting the U.S. dollar as world reserve currency. The continuation of the

ability of the U.S. federal government to print world money enables huge

government expenditures without raising taxes. This phenomenon has been called “dollar seignorage” by Michael

Mann (2013:

268-273). Despite the fact that the U.S. has a

huge trade deficit and has lost its centrality in the production of

manufactured goods, the financialization of the global economy built around the

U.S. dollar as global money has slowed the rate of U.S. hegemonic decline and

sustained the role of the U.S. as the biggest military power in the world. Ho-Fung argues that the Chinese Communist

Party is the mainstay of continuing U.S. hegemony because China is heavily

invested in the export model of development and because the dollar and U.S.

Treasury Bonds are still the most stable investment for the huge volume of

trade surplus generated by Chinese exports to Europe and the United States.

Ho-Fung contends that China’s

massive investment in low-yield U.S. Treasury bonds is “tantamount to a tribute

payment through which Chinese savings have been transformed into American consumption

power.” The question is how much longer

will dollar seignorage continue, and what will happen to global governance when

it finally collapses. A multipolar structure of global economic and military

power seems likely. What we do not want to do is what happened in the first

half of the 20th century.[20]

Living With the Animals in College Building South

Andrew Jorgensen arrived

at UC-Riverside in January of 2001, a gift from Jeff Kentor. Together we set up

the Institute for Research on World-Systems which at that time was located in

College Building South, the former home of the Director of the Citrus

Experiment Station, which was the land-grant institution that morphed into the

University of California-Riverside. This was one of the oldest buildings on

campus. It had fireplaces and was located at the extreme south end of campus on

a little side road up in the bushes, but across the road was a very nice

botanical garden with a pond and bananas trees that were trying hard to produce

bananas in the desert of Southern California. As Andrew mentions in his essay

(this section) the old house had a kitchen in between our offices, and it was

in the kitchen that our projects were germinated. Andrew used his cross-national comparative

skills to investigate the export of environmental degradation by core

countries. Since then he has produced an impressive corpus of studies on

environmental causes and consequences, and he is now chair of the Sociology

Department at Boston College.

Andrew also reports our friendship

with a large snake that loitered outside his office in College Building South.

After he moved on we had a family of raccoons living in the attic. The raccoon babies

were rescued by Rebecca Alvarez and Nelda Thomas. And Alexis Alvarez had pet

turtles in the pond. We hosted several conferences during the College Building

South years (see www.irows.ucr.edu/conferences/conf.htm ) and we

did a lot of research with undergraduate and graduate students at UC-Riverside

(see Figure 4).

Figure 4:

IROWS Colleagues at College Building South (Alexis Alvarez, Rebecca Alvarez,

Nelda Thomas, Chris Chase-Dunn, Lulin Bao and Hiroko Inoue)

After

Capital Penetration, More Capital Penetration

Jeff Kentor got his Ph.D in Sociology at

Johns Hopkins in 1998. He and Andrew Jorgenson are the

founding co-editors of Sociology of Development, published by University of California Press. Much of his

career was spent at the University of Utah, and it was from there that he sent

Andrew Jorgenson to UC-Riverside in 2001. Jeff is now chair of the Sociology Department

at Wayne State University. His essay

(this section) cites some of the more recent publications that have come out of

the capital penetration tradition. His essay also mentions the taped interview

that he and Andrew conducted with me at UC-R on June 7, 2017 in which I tell my

academic story. Thanks to Jeff and

Andrew for the opportunity to do this.

My

Intellectual Dad

John Meyer’s kind letter to Jeff Kentor

recounts some of the story told above. I wrote what is above before I had read

it. John saved my occupational life and his inspirational mentoring has also

produced several cohorts of graduate students who have gone on to productive

careers in sociology.

I only want to add one bit to

his account. Despite that the senior sociology faculty at Stanford was somewhat

less than sympathetic to my revolutionary urges, when I was arrested for

disturbing the peace and resisting arrest (a felony) at Stop the Draft Week in

Oakland in 1967 they bailed me out of jail. I thanked them then and I thank

them now. It took many more years to stop that war, but it was done. John is a

great sociologist who has inspired me with his dedication to research and his

attention to mentoring. I have tried to pass these things on.

Gender, Tunisia, the Arab Spring and

the World Revolution of 20xx

Valentine

Moghadam’s essay (this section) discusses the

relevance of the notion of semiperipheral development and world revolutions for

explaining local and transnational social movements that have emerged in the

last decade. Moghadam is an expert on the global feminist movement and on

Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) societies. She takes a refreshingly

political-economic approach to understanding global social change. Her essay

focusses mostly on Tunisia, but she also discusses the important role of that

women have played in democratic socialist social movements in both the core and

the non-core (see also Schaefer 2014).

Her analysis of both the hopeful aspects and the tragedies of the Arab Spring

movements is a valuable contribution to our effort to comprehend the

contemporary world revolution. Tunisia has indeed been an inspiring example for

democratic socialists, but most of the rest of the Arab Spring movements have

shown the limitations of Habermasian discourse and Ghandhian civil disobedience

in situations in which repressive states, imperial rivalries and powerful

reactionary counter-movements are willing and able to use violent repression in

politics. The New Age values of the New Global Left are at a big disadvantage

when politics get nasty. The demise of

the Latin American Pink Tide conveys a different lesson. The Pink Tide was a

wave of progressive redistributionist policies that swept Latin America (Chase-Dunn. Morosin and Alvarez 2014) but this welfare

depended on raw materials extractivism. The Pink Tide arose with the

commodity boom fueled by China but now it is foundering as commodity prices

have fallen.

Val tries

to put the best face on the neglect of gender analysis in my work. I agree with

what she says about the importance of unpaid female labor in core/periphery

relations. If I could do it over again I would pay more attention to this issue

and to the ecological aspects of world-systems. Though it may be too little too

late, I can mention that my textbook (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2016) is better on

both counts (gendering and ecological issues) and that I have recently devoted

attention to the issue of why monogamy became the predominant form of marriage

in modern global culture, even for rich and powerful men (Chase-Dunn and

Khutkyy 2016). In critiquing the

evolutionary psychology explanation of Walter Scheidel (2009a, 2009b) Dmytro

Khutkyy and I propose that monogamous polities could outcompete polygynous ones

because they had greater interclass solidarity and hence were better at

warfare. The idea that the rules apply to the powerful was well as those

without power does not produce equality for either men or women, but it is

preferable to a moral order in which the powerful can do whatever they want. I

am not sure if this helps fill my gendering gap but it shows that I do think

about these things.

Urban Studies, Settlement Systems and World-Systems

Mike Timberlake (this

section) reviews the development of urban studies during the globalization

awakening and provides a helpful and accurate survey of the IROWS research on settlement

systems. Mike arrived at Johns Hopkins as a postdoc not long after I was

exposed to urban geography and together we began to think about the world city

system. His valuable book, Urbanization in the World

Economy came out in 1985. We began

corresponding with urban geographer Peter J. Taylor and attended conferences

with others working on world cities (Saskia Sassen, Janet Abu-Lughod, etc.). His

essay also provides a helpful and accurate survey of the comparative and

quantitative research literature on cities and urban systems that has been

carried out by colleagues who were inspired by, or participated in, our early

studies of cities in the modern system. The only thing I would like to add to

Mike’s overview is a mention of the efforts we have made to improve the

estimates of the population sizes of premodern cities (see Pasciuti 2002 and

Pasciuti and Chase-Dunn 2002). As to whether

I am an urban sociologist, I should say that I have come to think of myself as

one after studying settlement systems since 1980 and teaching a lower division

course called “The City” since 2000.

Intersocietal Dynamics and

Sociocultural Evolution

Jon Turner’s essay (this

section) summarizes the comparative evolutionary world-systems perspective and

proposes some modifications. Turner is a famous sociological theorist who

coaxed me into moving to Riverside in 2000. His scope of comparison is

anthropological and we share an interest in the sociocultural evolution of

human societies and in comparing human social organizations with those of other

species (see Turner and Machalek 2017). Turner

prefers the term “inter-societal dynamics”[21] and he contends that

core/periphery relations are not as important as they have been purported to

be. He also contends that, while whole-system intersocietal dynamics are important,

they may not be the most important for explaining social change.

Jon Turner’s essay provides an

opportunity to clarify a few matters. He contends that small-scale systems

should be called intersocietal systems rather than world-systems. We have tried to make it clear that our use

of the term “world” refers to the set of interaction networks that are

important for reproducing and/or changing the institutions of everyday life.

Those connections constitute the relevant world in which people live. When communications and transportation

technologies were less developed “the tyranny of distance” was stronger. The

relevant “world” of direct and indirect interaction links for people in any locale

did not extend as far across space as it did after intercontinental travel had

become easier. This is what we mean when we speak of “very small world-systems.” [22]

Jon also contends that the core/semiperiphery/periphery

structure does not work very well for small-scale systems. We agree, but we

have introduced the distinction between core/periphery differentiation (a

situation in which polities with different degrees of population density are

interacting with one another) and core/periphery hierarchy, in which one or

more polities are dominating or exploiting other polities (Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2016:23). And we make it clear that it should not be assumed that all

world-systems have core/periphery hierarchies just because the modern system

does.[23]

Turner’s summary of our iteration

model and the study of upsweeps are clear and helpful exposition, and his

elaboration of his own models for understanding how warfare works as a selection

mechanism driving sociocultural evolution is a valuable contribution. He praises

the value of simulation modeling, and I agree.[24] Our SetPol project is

working on a multilevel model that we hope will be an improvement of the

whole-system iteration model by including the processes that are operating within societies, as does Turner’s

Figures 1 and 2 (and Turchin and Nefadov’s [2009]“secular cycle” model), as

well as processes operating at the level of whole world-systems (Chase-Dunn and

Inoue 2018). [25]

Regarding Turner’s contention that

the work of the world-systems theorists has been distorted by the assumption

that the contemporary capitalist system will be transcended by a socialist

world society,[26]

we can note that Wallerstein (2011) has not predicted how the structural crisis

that is now brewing will turn out, and that Chase-Dunn and Lerro (2014: Chapter

20) describe three possible outcomes for the next few decades, one of which is

similar to Turner’s prediction – “distintegration of the existing world system

to something less integrated than it is today, with very active geo-political

and geo-economic dynamics ruling a conflict-ridden world.” We call this

“collapse.” While this is certainly a

possible outcome, one of the findings from our studies of earlier upsweeps and

downsweeps is that downsweeps (collapses) do not last very long. So the issue of what will follow a possible

collapse is an important consideration. We agree that human history is partly

open-ended and so nothing is inevitable, but some outcomes are more likely than

others. And of the probable outcomes, some are much more desirable than

others. Undo pessimism is probably just

as distorting as undue optimism.

Thanks to Jeff Kentor and Andrew

Jorgenson for organizing the ASA session and for putting together this

collection of essays addressing my work. And thanks to Jackie Smith for the

opportunity to publish this in the Journal

of World-Systems Research. This

brief version of my academic memoirs leaves out the issue of how most of my

personal life interacted with my professional life, but that will have to wait

for another occasion. Let me also thank my parents, my brother Bill, my wife

Carolyn Hock and my daughters Cori, Mae and Frances for all their love and

support. And, as my friend Gunder Frank would have said, the struggle continues.

References

Apkarian,

Jacob, Jesse B. Fletcher, Christopher Chase-Dunn and Robert

A. Hanneman 2013

“Hierarchy

in Mixed Relation Networks: Warfare Advantage and Resource Distribution in

Simulated World-Systems”

Journal

of Social Structure,

Vol. 14. http://www.cmu.edu/joss/content/articles/volume14/Apkarian_etal.pdf

Arrighi,

Giovanni and Jessica Drangel 1986 “Stratification of the world-economy: an

explanation of

the semiperipheral zone” Review 10,1:9-74.

Berger,

Joseph, Bernard P. Cohen and Morris Zelditch, Jr. 1971 “Status Characteristics and Social

Interaction” Technical Report No. 42, Stanford Laboratory

for Social Research

Chase-Dunn, C. 1975 “International

Economic Dependence in the World-System”

Stanford University,

Sociology, PhD. Dissertation

Chase-Dunn, C. 1981. "Interstate system and capitalist

world-economy: one logic or

two?" International

Studies Quarterly 25, 1:19-42, March.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Thomas D. Hall. 1997. Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Boulder, CO:

Westview

Press

Chase-Dunn. C. 1990

"Resistance to imperialism: semiperipheral actors," Review, 13,1:1-31 (Winter).

Chase-Dunn, C., Richard Niemeyer, Alexis Alvarez, Hiroko Inoue, Hala Sheikh-Mohamed and Eran Chazan 2007 “Cycles of Rise and Fall, Upsweeps and Collapses: Changes in the Scale of

Settlements and Polities Since the Bronze Age” IROWS Working Paper #34

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows34/irows34.htm

C. Chase-Dunn, C and Matheu

Kaneshiro 2008

“Stability and Change in

the contours of Alliances Among movements in the social forum process”

IROWS Working Paper # 44

Chase-Dunn, C. and Kirk Lawrence 2010 “Alive and well: a response to Sanderson” International Journal

of Comparative Sociology 51,6:470-480

Chase-Dunn, C. , Alessandro Morosin and Alexis Alvarez 2014 “Social Movements and

Progressive

Regimes in Latin America: World

Revolutions and Semiperipheral Development” in Paul

Almeida and Allen Cordero Ulate

(eds.) Handbook of Social Movements across Latin

America, Springer

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Marilyn Grell-Brisk 2016 “Uneven and Combined Development

in the Sociocultural Evolution of

World-Systems” Pp. 205-218 in

Alex Anievas and Kamran Matin (eds.)

Historical Sociology and World History. Lanham, MD:

Rowman and Littlefield

Chase-Dunn C. and Dmytro Khutkyy 2016 “The Evolution of Geopolitics and

Imperialism in Interpolity Systems”

in Peter Bang, C. A. Bayly & Walter Scheidel (eds. The Oxford

Handbook World History of Empire

Chase-Dunn, C. and Bruce Lerro 2016 Social Change : Globalization from

the Stone Age to the Present. London: Routledge.

Chase-Dunn,

C., Hiroko Inoue, David Wilkinson and E.N. Anderson 2017 “The

SETPOL

Framework: Settlements

and polities in World-Systems” IROWS Working

Paper

#116

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows116/irows116.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. an

Hiroko Inoue 2017 “Problems of Peaceful Change: Interregnum,

Deglobalization and

the Evolution of Global Governance. IROWS

Working Paper #117

http//:irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows117/irows117.htm

Chase-Dunn,

C and Hiroki Inoue 2018 “Spirals

of sociocultural evolution within polities and in

interpolity systems” To be presented at the

annual meeting of the International Studies

Association, San Francisco, April 4-7

Chase-Dunn,

C and Hiroki Inoue, Forthcoming “Long Cycles and World-Systems:

Theoretical Research Programs” in William R.Thompson (ed.) Oxford Encyclopedia of Empirical

International

Relations Theories,New York: Oxford University Press

and the online Oxford

Research Encyclopedia

in Politics. Irows Working Paper # 115

at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows115/irows115.htm

Cioffi-Revilla,

Claudio 2001 “Origins of the international system: Mesopotamian and West Asian

Polities, 6000 BC to 1500 BC”

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.189.2373&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Collins, Randall 1992 "The

geopolitical and economic world systems of kinship-based and agrarian-coercive

societies."

Review

15:3(Summer):373-388.

Firebaugh, Glenn 1992 "Growth Effects of Foreign and Domestic

Investment." American Journal of

Sociology 98 (July):105-130.

_______________1996

"Does Foreign Capital Harm Poor Nations? New Estimates Based on

Dixon and Boswell's Measures of

Capital Penetration." American

Journal of Sociology, 102

(September): 563-575. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/230957?journalCode=ajs

Fletcher,

Jesse B, Jacob Apkarian, Anthony Roberts, Kirk Lawrence, C. Chase-Dunn and

Robert A. Hanneman

‘War

Games: Simulating Collins’ Theory of Battle Victory’ 2012 Cliodynamics:

The Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical History

2,2: 252-275. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hk4279k

Hannan, Michael T., and John H. Freeman.1993 Organizational

ecology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University

Press.

Heise, David 1970 “Causal

inferences from panel data” Edgar F. Borgatta and G.W. Bohrnstedt

(eds.)

Sociological Methodology 1970. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Inoue,

H., A. Álvarez, K. Lawrence, A. Roberts, E. N. Anderson, & C.

Chase-Dunn 2012

“Polity scale

shifts in world-systems since the Bronze Age: A comparative inventory of

upsweeps and collapses”

International

Journal of Comparative Sociology June 53 (3): 210-229 http://cos.sagepub.com/content/53/3/210.full.pdf+html

Inoue,

Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Eugene N. Anderson, Andrew Owen, Rebecca

Álvarez, Kirk Lawrence and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2015

“Urban scale

shifts since the Bronze Age: upsweeps, collapses and semiperipheral

development” Social Science History. Volume 39 number 2, Summer

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows89/irows89.htm

Inoue, H., Alvarez,

A., Anderson, E. N., Lawrence, K., Neal, T., Khutkyy, D., Nagy, S., &

Chase-Dunn, K. 2016

“Comparing

World-Systems: Empire Upsweeps and Noncore Marcher States Since the Bronze Age”

IROWS Working Paper

#56, IROWS, University of California-Riverside. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows56/irows56.htm

Lakatos, Imre

1978 The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes V. 1

Edited by John Worrall and

Gregory

Currie. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mann, Michael 2013 The Sources of

Social Power, Volume 4: Globalizations, 1945-2011. New York:

Meyer, John W.

2009 World Society. Edited by Georg Krukcken and Gili S.

Drori. New

York:

Oxford University Press.

_____________

and Michael T. Hannan (eds.) 1979 National Development

and the World System: Educational, Economic, and Political Change, 1950-1970.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pasciuti ,

Daniel 2002” A

measurement error model for Estimating the Population Sizes of

Preindustrial Cities”

https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/estcit/modpop/modcit.pop

Pasciuti,

Daniel and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2002 “Estimating the Population Sizes of

Cities” https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/estcit/estcit.htm

Ross,

Robert J. S, and Kent C. Trachte 1990 Global

Capitalism: the New Leviathan. Albany, NY: State

University

of New York Press.

Sanderson,

Stephen K. 1990 Social

Evolutionism. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

__________________

2005 “World-Systems

Analysis after Thirty Years: Should it Rest in Peace?”

International Journal of Comparative Sociology

Vol 46, Issue 3: 179-213

Schaeffer,

Robert K. 2014 Social Movements and Global Social Change.: The Rising Tide Lanham, MD:

Rowman and Littlefield.

Scheidel, Walter

2009a “Sex and empire: a Darwinian perspective” Pp.

255-324 in Ian Morris and Walter Scheidel (eds.)

The Dynamics of Ancient Empires. New

York: Oxford University Press

_________________2009b

“A peculiar institution? Greco-Roman monogamy in global

context.” The History of the Family 14,

280–291.

Smith, Jackie, Marina Karides, Marc Becker, Dorval Brunelle,

Christopher Chase-Dunn,

Donatella della Porta,

Rosalba Icaza Garza, Jeffrey S. Juris,

Lorenzo Mosca, Ellen Reese,

Peter Jay Smith and Rolando Vazquez 2014 Global

Democracy and the World Social Forums.

Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers

Timberlake, Michael (ed.) 1985

Urbanization in the World Economy. New York: Academic Press.

Turchin,

Peter and Sergey A. Nefadov

2009 Secular Cycles. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Turner, Jonathan H. 2010 Theoretical

principles of sociology: Volume 1 Macrodynamics. New York London:

Springer

Turner,

Jonathan H. and Richard Machalek 2017 The New Evolutionary Sociology:

New and Revitalized

Theoretical

Approaches New York: Routledge

Wallerstein,

Immanuel 2011 “Structural Crisis in the World-System: Where Do We Go from Here?”

Monthly Review V. 62, issue 10 https://monthlyreview.org/2011/03/01/structural-crisis-in-the-world-system/