Comparing World-Systems:

Empire

Upsweeps and Non-core marcher states Since the Bronze Age*

Targaryen Marcher Lord

Hiroko

Inoue, Alexis Álvarez,

E.N. Anderson,

Kirk Lawrence, Teresa

Neal, Dmytro Khutkyy,

Sandor Nagy, Walter DeWinter and Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute

for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

![]()

National Science Foundation Grant #: NSF-HSD SES-0527720

To be presented at the annual

meeting of the Pacific Sociological Association, Oakland, CA ,

March

30-April 2, 2016 Marriott Downtown City Center draft v. 4-1-16, 11479 words.

This paper is available as IROWS Working Paper #56 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows56/irows56.htm

Appendix:

Classification of Empire Upsweeps https://irows.ucr.edu/cd/appendices/semipmarchers/semipmarchersapp.htm

*Thanks to Rein Taagepera, a prodigious and pioneering coder of the territorial sizes of polities.

Need more on the 17th and 18th Egyptian dynasties,

Abstract: This research examines one of the

implications of the hypothesis of semiperipheral development: that major

increases in the sizes of polities have been accomplished mainly by conquests

carried out by semiperipheral or peripheral marcher states. We use the

comparative evolutionary world-systems perspective to frame our study of

twenty-one upsweeps in the territorial size of the largest polities in four

regional world-systems and in the expanding Central Political/Military Network

since the Bronze Age. We seek to determine whether or not each of these

twenty-one upsweeps were instances in which a semiperipheral or peripheral

marcher state produced the polity size upsweep by means of conquest. The

hypothesis of semiperipheral development holds that polities that are not in

the core have been, and continue to be, unusually fertile locations for the

implementation of organizational and technological innovations that transform the

scale and the developmental logic of world-systems. This is because

semiperipheral and peripheral polities have less invested in older

institutional structures and than do core polities and they also have greater

incentives to take risks on new technologies and organizational forms. One

important manifestation of semiperipheral development is the marcher state

phenomenon: a recently founded sedentary polity out on the edge of an older

core region conquers the older core polities and puts together a core-wide

empire that is significantly larger than earlier polities have been. This

phenomenon has occurred repeatedly, but it is not the only way in which large

empires have emerged. We find that over

half of the twenty-one identified empire upsweeps were likely to have been

produced by marcher states from the semiperiphery (10) or from the periphery

(3). We also investigate those upsweeps that did not involve non-core conquest

to determine what caused them.

This paper is a part of a larger

project that is studying the growth/decline phases and upward sweeps of

settlement and polity sizes in order to test explanations of long-term patterns

of human socio-cultural evolution. We use the comparative and evolutionary

world-systems perspective first outlined by Chase-Dunn and Hall (1993,1997) as

our orienting theoretical approach. The focus is on interpolity systems

(world-systems) rather than on single polities.[1]

We study how sociocultural evolution occurred in systems of interacting

polities. We propose a somewhat revised definition and typology of semiperipherality based on our study of empire upsweeps.

The main focus of this article is on the evolutionary significance of semiperipherality since the period in the early Bronze Age

in which states first emerged.

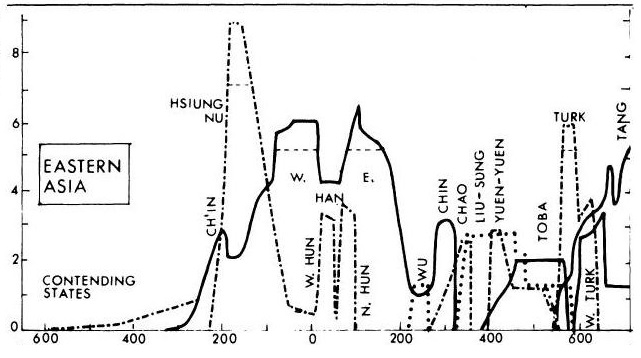

Figure 1: Rein Taagepera’s (1979:118) East Asia Graph 600 BCE to 600 CE

Regions,

Political-Military Networks and Upward Sweeps

There

has been a long-term upward trend in which human polities have grown in

population and territorial size while the total number of sovereign polities

has decreased (Carneiro 1978).[2]

Human polities have evolved from bands to tribes to chiefdoms to states and

then to empires. This long-term trend has occurred in a series of events that

we call upward sweeps (upsweeps). Upsweeps are defined as those instances in

which a polity emerges that is at least 1/3 larger in territorial size than the

average of the three previous peaks of polity size (Inoue et al 2012).

All hierarchical world-systems have

experienced a cycle of centralization and decentralization in which a large

polity in an interpolity system emerged and then declined. This sequence of

rise and fall is seen in interpolity systems composed of chiefdoms (Anderson

1994), states, empires and modern hegemons. In such cycles most of the upward

phases result in a polity that is nearly the same size as the one that existed

at the previous peak of polity size. This we call a “normal rise.” An upsweep

involves a significant increase in the size of the largest polity relative to the

previous peak. These upsweeps are much less frequent than are normal

rises. But they are the events that

instantiate the long-term trend toward larger polities and so they are very

important for the evolution of sociocultural complexity.

The Settlements and Polities (SetPol) Research Working Group at the Institute of Research

on World-Systems[3]

has quantitatively identified twenty-one such polity upsweeps in five world

regions since the early Bronze Age (Inoue et

al 2012). In order to identify these polity upsweeps we have mainly used

Rein Taagepera’s (1978a, 1978b, 1979, 1997) estimates

of the territorial sizes of the largest states and empires in four world

regions and in the interpolity system that David Wilkinson (1987) has called

“Central Civilization.”[4]

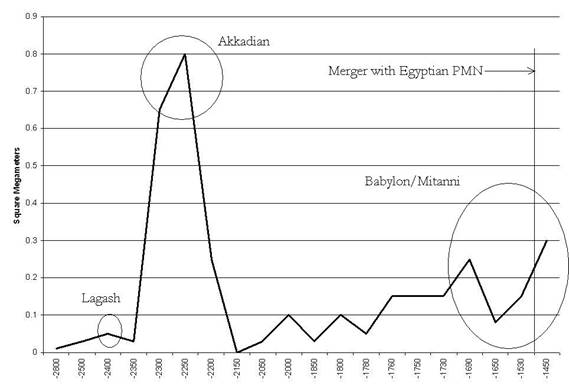

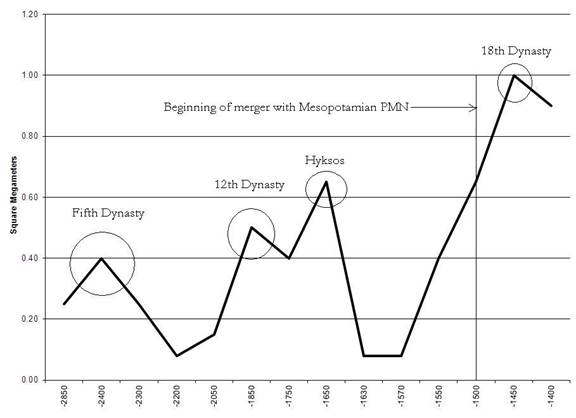

Figure

2: Largest polities in the Mesopotamian PMN, 2800

BCE-1500 BCE (Square Megameters)[5]

Figure 2 shows the territorial sizes of

the largest polities in the Bronze Age Mesopotamian political-military network

(PMN) between 2800 BCE and 1500 BCE. A political-military network is a set of

fighting and allying polities. This is equivalent to what International

Relations Political Scientists call “the international system” except that they

rarely study such systems before the treaty of Westphalia in 1648 CE. Figure 2 illustrates the difference between

empire upsweeps and normal rises. Lagash carried out an upsweep because it

became significantly larger than the largest earlier polities had been. The

Akkadian Empire was a gigantic upsurge. The Babylon/Mitanni upsweep was not as

big as the Akkadian had been, but it was more than 1/3 larger than the average

of the three previous peaks and so qualifies as an upsweep. Around 1500 BCE the

Mesopotamian and Egyptian PMNs merged to become what we call the Central PMN.

We

contend that interaction networks, rather than homogenous cultural or

ecological regions, are the best way to bound evolving human systems for the

purposes of studying the causes of socio-cultural evolution (Chase-Dunn and

Jorgenson 2003)[6]. But one problem with using interaction

networks is that they expand (and contract) over time, which can make the

results of comparisons dependent on the decisions one has made about the timing

of changes in the spatial boundaries of networks. Our project uses four world

regional political-military networks (PMNs) and one expanding PMN – what we

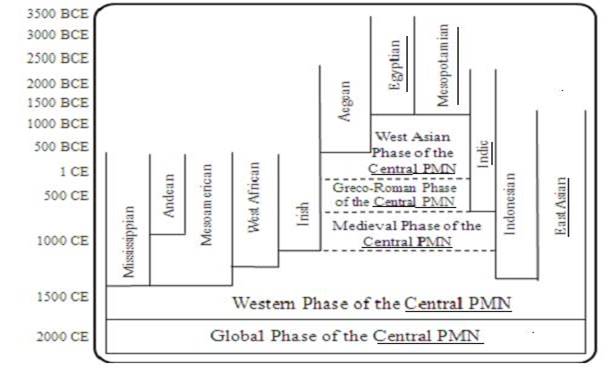

call, following David Wilkinson (1987), the Central PMN (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Chronograph the expansion of the Central

PMN and its engulfment of regional PMNs since the Bronze Age. [revised from

Wilkinson (1987); the PMNs studied here

are underlined]

The

four regional PMNs are Mesopotamia, Egypt, East Asia and South Asia. The

Central PMN, a network of allying and warring states and empires, is bounded

following Wilkinson.[7]

It begins around 1500 BCE when the formerly separate Egyptian and Mesopotamian

interpolity systems merged and it then expanded to eventually become the

contemporary global international system (see Figure 3). Long-distance trade in

prestige goods linked the East Asian PMN with the Central PMN since the time of

the Roman and Han empires, but East Asia had a substantially separate

interpolity system (PMN) until China was surrounded and penetrated by the

European powers in the 19th century.[8]

Core/Periphery

Relations

The notion of core/periphery relations

has been a foundational concept in both the modern world-system perspective

(Wallerstein 1974) and in the comparative evolutionary world-systems

perspective (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1993, 1997; Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2014). World-systems are systems of interacting polities and they often (but

not always) are organized as interpolity hierarchies in which some polities

exploit and dominate other polities. Chase-Dunn and Hall redefined and expanded

the core/periphery concept to make it more useful for comparing the modern

world-system with earlier regional world-systems. The core/periphery

distinction is a relational concept.

In other words, what coreness, peripherality

and semiperipherality

are depends on the larger context in which they occur – the nature of

the polities that are interacting with one another and the nature of their

interactions.

When we use the idea of

core/periphery relations for comparing very different kinds of world-systems we

need to broaden the concept and to make an important distinction (see

below). But the most important point is

that we should not assume that all

world-systems have core/periphery hierarchies just because the modern

system does. It should be an empirical question in each case as to whether

core/periphery relations exist. Not

assuming that world-systems have core/periphery structures allows us to compare

very different kinds of systems and to study how core/periphery hierarchies

themselves have emerged and evolved.

The distinction between civilization and

barbarism (and savagery) has a long history as polities have engaged in

“othering” and in social science. We seek to replace disparaging terminologies

with less loaded concepts, but our search for empirical evidence of

core/periphery distinctions often encounters documents in which othering plays

an important part, and it is best to be aware of these issues in order to make

the best judgments about what was really going on.

For comparing

different kinds of systems it is also helpful to distinguish between core/periphery differentiation and core/periphery hierarchy. “Core/periphery differentiation” means that

polities with different population densities are interacting with one another.

As soon as we find village dwellers in sustained interaction with nomadic

neighbors we have core/periphery differentiation. “Core/periphery hierarchy” refers to the

nature of the relationships between polities.

Interpolity hierarchy exists when some polities are exploiting and/or

dominating the people in other polities. Well-known examples of interpolity

domination and exploitation include the British colonization and

deindustrialization of India, or the conquest and subjugation of Mesoamerica by

the Spaniards. But core/periphery hierarchy is not unique to the modern

Europe-centered world-system of recent centuries. Roman and Aztec imperialism

are also famous.[9]

Distinguishing between

core/periphery differentiation and core/periphery hierarchy allows us to deal

with situations in which larger and more population dense polities are

interacting with smaller ones, but are not exploiting them. It also allows us

to examine cases in which smaller, less dense polities were exploiting larger

and denser polities such as occurred in the long, and consequential,

interaction between the nomadic horse pastoralists of Central Asia and the

agrarian states and empires of China and Western Asia. The most famous case was

that of the Mongol Empire of Chingis Khan, but confederations

of Central Asian steppe nomads managed to extract tribute from agrarian states

long before the rise of Mongols (Barfield 1989).[10]

The question of

core/periphery status also should be considered with regard to different

spatial scales of interaction. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1993,1997) point out that

regional world-systems often were composed of important interaction networks

that had different spatial scales. They use a “place-centric” approach to

spatially bounding systemic interaction networks that estimates the fall-off of

interaction effects from a focal settlement or polity (Renfrew 1975). The

network is spatially bounded by deciding how many indirect links (degrees of

separation) are result in the fall-off

of regular and two-way interactions that have an important impacts on the

reproduction or transformation of institutions at the focal locale (Chase-Dunn

et al 2016). Bulk goods networks (in which everyday foods and raw materials

were exchanged) were usually smaller in extent relative to political-military

networks (PMNs) of allying and fighting polities. Prestige goods networks (in

which high value per weight goods were exchanged) usually were larger than

PMNs, as were Information Networks. Systems vary in terms of how important the

exchange of prestige goods and/or information are for the reproduction of

social institutions. The issue of

core/periphery status always needs to be asked for both the bulk goods and

political-military networks and should also be considered for prestige goods

and information networks when they are systemic.

Semiperipheral

Development

The semiperiphery concept was also

originally developed for the study the modern world-system (Wallerstein 1976).

But it too has been expanded for the purposes of comparing world-systems. For Immanuel

Wallerstein the semiperiphery is a middle stratum in the global hierarchy that

helps to reduce the strains that emerge from polarization. Chase-Dunn and Hall

(1997: Chapter 5) contend that semiperipheral polities are often the “seedbeds

of change” because some of them implement new technological and organizational

features that allow them to successfully compete with core polities. This is

thought to account for the phenomenon of uneven development and the movement of

core regions from their original locations (Chase-Dunn and Grell-Brisk

2016)..

Hub theories of innovation have been

popular among world historians (McNeill and McNeill 2003; Christian 2004) and

human ecologists (Hawley 1950). The hub theory holds that new ideas and

institutions tend to emerge in large and central settlements where information

cross-roads bring different ideas into interaction with one another. The hub

theory is undoubtedly partly correct, but it cannot explain some of the

long-term patterns of human sociocultural evolution, because if an information

cross-road was able to out-compete all contenders then the original information

hub would still be the center of the world. But that is not the case. We know

that cities and states first emerged in Bronze Age Mesopotamia. Mesopotamia is

now Iraq. It had 100% of the world’s largest cities and the most powerful

polities on Earth in the Early Bronze Age (Morris 2010, 2012). Now it has

neither the largest cities nor the most powerful polities. Most of the regional

world-systems have undergone a process of uneven development in which the old

centers were eventually replaced by new centers out on the edge.

Chase-Dunn and Hall contend that it is

often polities out on the edge that transform the institutional structures and

accomplish the upsweeps. This hypothesis is part of a larger claim that

semiperipheral polities often play transformative roles that cause the

emergence of complexity and hierarchy within polities and in world-systems.

This is the most important justification of the claim that world-systems,

rather than single polities (or societies), are a necessary unit of analysis

for explaining human sociocultural evolution. [11]

The node theory does not well account for the spatially uneven nature of evolutionary change. The cutting edge of evolution moves. Old centers have often been transcended by polities out on the edge that were able to rewire network nodes in a way that expanded the spatial scale of networks.

The phenomenon of semiperipheral

development has taken various forms: semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms,

semiperipheral marcher states, semiperipheral capitalist city-states, the

semiperipheral position of Europe in the larger Afroeurasian

world-system, modern semiperipheral nation-states that have risen to hegemony,

and contemporary semiperipheral societies that are engaging in novel and

potentially transformative economic and political activities that may change

the nature of the contemporary global system.

Philippe Beaujard (2005:239) makes the point that core/periphery

relations often involve co-evolution. Even when exploitation and domination of

the non-core by the core occurs, polities in both zones are altered and

co-evolve. In many systems in Afroeurasia and the

Americas interactions between hunter-gatherers and farmers led to the emergence

of polities that specialized in pastoralism (Lattimore 1940; Barfield 1989; Honeychurch 2013; Hamalainen

2008). Some of the pastoralists were exploited and dominated by core polities

but others turned the tables and were able to extract resources from agrarian

states.

There

are several possible processes that might account for the phenomenon of

semiperipheral development. Randall Collins (1981) has

argued that the phenomenon of marcher states conquering other states to make

larger empires is due to the geopolitical “march land advantage.” Being out on

the edge of a core region of competing states allows more maneuverability

because it is not necessary to defend the rear. This geopolitical advantage

allows military resources to be concentrated on vulnerable neighbors. Peter Turchin (2003) argued that the relevant process is one in

which group solidarity is enhanced by being on a “metaethnic

frontier” in which the clash of contending cultures produces strong cohesion

and cooperation within frontier societies, thus promoting state formation and

empire formation (see also Turchin 2009). Turchin focuses especially on relations between polities

that face each other on a transition boundary between steppe and irrigated agricultural

ecological zones. His (2009)

mirror-empires model proposes that antagonistic interactions between nomadic

pastoralists and settled agriculturalists often resulted in an autocatalytic

process in which both nomadic and farming polities scaled up their polity

sizes.

Carroll Quigley (1961) distilled another version of the semiperipheral development hypothesis from the works of Arnold Toynbee. Another factor affecting within-group solidarity is the different degrees of internal stratification usually found in premodern systems between the core and the semiperiphery. Core societies often have old, crusty and bloated elites who rely on mercenaries and “foreigners” as subalterns, while semiperipheral leaders are more often charismatic individuals who attract strong loyalty from their soldiers. Less stratification can mean greater group solidarity. And this may be an important part of the semiperipheral advantage in systems in which within-polity inequality is greater in the core than in the non–core.

But Arnold Toynbee (1946) also suggested another way in which the peoples of

semiperipheral regions might be motivated to take risks with new ideas,

technologies and strategies. Semiperipheral polities are often located in

ecologically marginal regions that have poor soil and little water or other

natural disadvantages. Patrick Kirch relies on this

idea of ecological marginality in his depiction of the process by which

semiperipheral marcher chiefs were most often the conquerors that created

island-wide paramount chiefdoms in the Pacific (Kirch

1984). It is quite possible that all these features combine to produce what

Alexander Gershenkron (1962) called “the advantages

of backwardness” that allow some semiperipheral societies to transform and to

dominate regional world-systems.

Those new

technologies and organizational forms that transform the logic of development

and allow world-systems to get larger, more complex and more hierarchical, are

often invented and implemented by semiperipheral polities. Innovation and

implementation are separate, but connected issues. Owen Lattimore (1980)

contended that non-core polities are often the locus of important innovations.

But it is obvious that innovations occur within core societies as well. What

are perhaps more important are the decisions to implement and invest in new

ideas and organizational changes. While some innovations may emerge from

non-core polities, it is perhaps more important that polities out on the edge

have a greater incentive to take the risks involved in implementing new

technologies and organizational forms.

Semiperipheral polities are often involved in processes of

rapid internal class formation and state formation and they do not have large

investments in, and commitments to, doing things the way they have been done in

older core polities. They do not have institutional or infrastructural sunk

costs. So they are freer to implement new institutions and to experiment with

new technologies.

There are several different ways to be

semiperipheral (see below) and semiperipheral polities not only sometimes

transform systems but they also sometimes take over and become the new

predominant core polities. We have

already mentioned semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms. The chiefdoms that

conquered and unified a number of smaller chiefdoms into larger paramount

chiefdoms were usually from semiperipheral locations. Peripheral peoples did not usually have the

institutional and material resources that would allow them to implement new

adaptive strategies or to take over older core regions. It was in the semiperiphery that core and

peripheral social characteristics could be recombined in new ways. Sometimes this meant that more adaptive and

competitive techniques of power were strongly implemented in semiperipheral

polities.

Much better known than

semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms is the phenomenon of semiperipheral marcher states. Many of the largest empires in all

world regions were assembled by conquerors who came from semiperipheral

polities. The most famous examples are

the Achaemenid Persians, the Macedonians led by Alexander[12],

the Romans, the Islamic Caliphates, the Ottomans, the Manchus and the Aztecs.

But some semiperipheries

transform institutions, but do not take over the interpolity system of which

they are a part. The semiperipheral capitalist city-states operated on the

edges of the tributary empires where they bought and sold goods in widely

separate locations, encouraging farmers and craftsmen to produce a surplus for

trade (Chase-Dunn et al 2015). The Phoenician cities (e.g. Tyre, Sidon, Biblos, Carthage,

etc.), as well as Malacca, Venice, Genoa and the cities of the Hanseatic

League, spread commodification and expanded markets by producing manufactured

goods and trading them across great regions.[13] In this way the semiperipheral capitalist

city-states helped to commercialize the world of the tributary empires without

themselves becoming core powers.

The modern world-system has

experienced a sequence of the rise and fall of hegemonic core states. The

Dutch, the British and the U.S. were countries that had formerly been in

semiperipheral positions relative to the modern core/periphery hierarchy. And indeed the rise of Europe within the

larger Afroeurasian world-system was also a case of

semiperipheral development, one in which a formerly peripheral and then

semiperipheral region eventually rose to become a new core and to bring all the

regions into a now-global interpolity system (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014).[14]

Indicators

of Semiperipherality

The main purpose of this article is to

determine which, and how many, of the twenty-one quantitatively identified

empire upsweeps were brought about by semiperipheral marcher states. In order

to do this we need to specify what we mean by semiperipherality.

This is not a simple task because, as we have mentioned above, world-system

positions (core, periphery, semiperiphery) are relational concepts. In other

words, what semiperipherality is depends on the

larger context in which it occurs – the nature of the polities that are

interacting with one another and the nature of their interactions. The most

general definition of the semiperiphery

is: an intermediate location in an interpolity core/periphery structure. The

minimal definition of core/periphery relations, as mentioned above, is that

polities with different degrees of population density are interacting with one

another. This is what Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) have called “core/periphery

differentiation.” The idea of “core/periphery hierarchy” is more stringent. It

requires interpolity domination and exploitation. In this study we will be

looking for evidence that a polity that conquered other polities and was

responsible for an upward sweep in territorial size was semiperipheral relative

to the other polities it was interacting with before it started on the road to conquest. We will use four main

empirical indicators to make such determinations:

·

the geographical location of the society relative to other societies

that have greater or lesser amounts of population density. Is it out on the

edge of a region of core polities?;

·

the relative level of development: population density, which is usually

indicated by the sizes of settlements, the relative degree of complexity and

hierarchy, the mode of production: e.g foraging,

pastoralism, nomadism vs. sedentism, horticulture vs.

agriculture, the size of irrigation systems, etc. Foragers (hunter-gatherers)

and pastoralists are usually peripheral to more sedentary agriculturalists and

those who dwell in large settlements;

·

the recency of the adoption of sedentism,

agriculture, class formation and state formation; and

·

relative ecological marginality.

Core polities usually hold to best

locations in terms of soil and water. The semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms of

the Pacific Islands were typically from the dry side of the island where land

was steeper and soil was thinner (Kirch 1984). Of

course, which land is better depends on the kind of resources that are being

used and the technologies available for appropriating resources. But ecological

marginality is often an important aspect of semiperipherality.

Polities in ecologically marginal regions have a powerful incentive for taking

the risks of conquest.

The Aztecs are a proto-typical example

of a semiperipheral marcher state. They were nomadic hunter-gatherers who

migrated into the valley of Mexico and settled on an uninhabited island in Lake

Texcoco. There had already been large states and

empires in the valley of Mexico for centuries. The Aztecs hired themselves out

as mercenary soldiers, developed a class distinction between nobles and

commoners and claimed to have been descended from the Toltecs,

an earlier empire. Then they began conquering the older core states of the

valley of Mexico, strategically picking first on weak and unpopular states,

until they had gathered enough resources to “roll up the system.” The Aztec

story has all of the elements specified above that we will use in examining our

upsweep cases.

One issue that complicates the

determination of world-system position is: semiperipheral to what? A polity may

have different relationships with different other polities in the same

interpolity network. For example, Macedonia had one kind relationship with the

other Greek states, and a different kind of relationship with the Persian

Empire. Semiperipherality is relative to the system as a whole, but may also be affected by

important differences between other states in a system and by the existence of

different kinds of relations with those other states.

Philippe Beaujard (2005) makes good use of the semiperiphery concept

in his study of the emergence of a world-system surrounding the Indian Ocean. Beaujard (2005:442) mentions instances in which the

emergence of regional settlements that connected hinterlands with core areas

were facilitated by the presence of merchants and religious elites who were

migrants from core regions. Beaujard’s study of the emergence of unequal exchange

between the coastal Swahili cities and the interior of the East African

mainland notes that immigrants from the Arabian core helped to form commercial

ties, intermarried with local elites, and converted locals to Islam, thereby

promoting a process of class-formation that led to the emergence of

semiperipheral polities along the coast (see also Fleischer et al 2015). Beaujard

also affirms our point that innovations sometimes occur in semiperipheral

polities (445).

We have mainly focused on

the world-system positions of polities, but Beaujard’s

analysis of East Africa suggests that core/periphery relations may be involved

in important processes of social change even when individuals and families are

not in control of whole polities. We are interested in all the ways in which

core/periphery relations may be connected with social change.

The logical alternatives to semiperipherality are coreness and peripheralness. Core states are

older, more stratified, have bigger settlements, and they have had the

accoutrements of civilization, such as writing, longer. Peripheral polities are

often nomadic hunter-gatherers or pastoralists, hill people, forest people or

desert people. If they are sedentary, their villages are small relative to the

settlements of those with whom they are interacting. We also note that some conquest empires were

formed by peripheral marcher states or by old core states that made a comeback.

David Wilkinson’s (1991) survey of the core, peripheral and semiperipheral

zones of thirteen interpolity systems, is helpful in suggesting criteria for

designating these zones, but Wilkinson did not address the question we are

asking here: were the polities that produced empire upsweeps semiperipheral

before they did this?

We should also note that some large

empires have been formed by internal revolt in which a subordinate ethnic group

or caste revolted and took power in an existing state and then carried out an

expansion by conquest. The slave-soldiers of the Mamluk

Sultanate are an obvious example, and Norman Yoffee

(1991) has contended that the Akkadian empire was the result of an ethnic revolt

(but see our decisions about the Akkadian Empire in the Appendix). And some

territorial upsweeps have been generated by dynastic changes that were

generated by processes mainly internal to the polity that carried them out. A

dynastic coup can lead to a territorial upsweep. The point here is that there

are possible alternatives to the semiperipheral marcher state route to an

empire upsweep. We will also note cases

in which core/periphery relations are in some way involved even though it is

not a case of a semiperipheral marcher state.

We mentioned Beaujard’s

(2005) study of how migrants from the core to the semiperiphery led to social

changes. In the Sui-Tang upsweep discussed below Turkic generals from the

frontier led military coups that produced dynastic changes and territorial

upsweeps. And Peter Turchin’s (2009) mirror-empires model implies that an

upsweep could be caused by tensions generated along a steppe/sown edge that is

not a result of conquest of the sown by the steppe, but rather the expansion of

the sown polity that is a result of external threats from the steppe.

Demographic

structural cycles [also called “secular cycles” by Turchin

and Nefadov (2009)] are processes of demographic

growth and increasing population pressure within polities that cause class

conflict and state break-down. Turchin and Nefedov explicated Jack Goldstone’s (1991) model of the

secular cycle, an approximately 200 yearlong demographic cycle, in which

population grows and then decreases. Population pressures emerge because the

number of mouths to be fed and the size of the group of elites get too large

for the resource base, causing conflict and the disruption of the polity. Turchin and Nefedov (2009) tested their

formulation on a number of agrarian empires, confirming the principle that

cycles of population growth and elite overproduction led to sociopolitical

instability and regime transitions within states.

The

demographic structural cycle is understood to occur almost entirely within

polities, but the origin of this kind of model stems from Ibn Khaldun’s theory of both state formation and state

breakdown – dynastic cycles. Ibn Khaldun was a

Tunisian Arab from an Andalusian family.

In the 14th century CE he argued that dynasties typically

lasted three or four generations. A

dynasty would get old and corrupt, and “barbarians” (what we call

semiperipheral marcher states) would take over.

The leader of a “barbarian” marcher polity had to be generous,

charismatic, and a brilliant and sophisticated war leader as well as a good

manager of men in order to inspire his warriors and get their support. His followers thus developed ‘asabiyah, basically loyalty, but more than loyalty --

an obligation formed by the leader’s generosity (they owed him for feasting,

presents, etc.) and by respect for his ability and success. Thanks to genius and ‘asabiyah, a particular marcher polity could take over and

start a new dynasty. The first

generation went well. The leader was the

charismatic founder. There was lots of

land and loot, to say nothing of women and slaves, captured from the former

dynasty. The warriors were duly rewarded

for their ‘asabiyah by getting tons of

goodies. They settled down, but they

were still warlike enough to hold the state against all comers.

The

second generation was often a Golden Age, with the dynasty ruling over a realm

of peace and prosperity. Wealth derived

from using the land and other resources, producing taxes which were used to

support brilliant culture, science, and literature. The empire tended to expand at the expense of

neighbors and the population grew.

The

third generation was a time of decline.

The land filled up with people.

Production declined because of environmental degradation and taxes also

declined. The rulers therefore had to

extort more to keep going. Military

expansion hit a limit -- war now costs more than it is bringing in. The ratio

of war expenses to captured loot declined because of expanding frontiers and

more enemies. Meanwhile the court is now

far from its charismatic founder. The

royal family has expanded, and there are countless supernumerary princes

running around desperate for wealth. The

bureaucracy has expanded to try to control the mess. Princes and bureaucrats fall prey to

corruption. How else can they keep up their lifestyle? This means still more taxes on a population

that has expanded and thus is faced with a shrinking land base per capita.

The

fourth generation is overpopulated, corrupt, and broke. The population naturally begins to rebel, or

at best they are disloyal to their rulers.

The stage is set for the next set of barbarians to take over. The whole cycle takes 75-100 years

(generations are typically 25 years). Buildup of population and rural poverty,

failure of food production to keep up, environmental deterioration worse in

final decades than in earlier ones, corruption increases and military

adventuring becomes overstretched.

A

very sophisticated model of state formation is presented by Victor Lieberman (2003, 2009; see

also Turchin 2015) that combines both internal and

external factors to explain waves of cultural integration and how these played

out somewhat differently in regions of Eurasia depending on how exposed they

were to nomadic or seaborne invaders. While the demographic structural approach

focusses on state breakdown, Lieberman focusses on state-building projects and

their consequences for cultural integration and the emergence of national

identities. From his vantage point as an historian of Burma he focusses on

mainland Southeast Asia, and then, in a refreshing version of positionality,

uses his model to examine similar developments in other regions of Eurasia.

Lieberman’s

approach is relevant to our study of upsweeps of polity size and non-core

marcher states because he contends that the processes of integration differed

because some regions were less exposed to invasion than others. What he calls the six “protected rimlands” of Eurasia were regions that were on the edges of

earlier civilizational complexity, and that were less exposed to conquest

because of geographical barriers to nomadic or seaborne invaders. The six

protected rimlands are Burma, Siam, Vietnam, Russia,

France and Japan. Because these areas were less exposed to marcher states and

incursions they were able to forge strong states and strong national cultures.

On the other hand, China, much of Southwest Asia, the Indian subcontinent and

island Southeast Asia were vulnerable to maritime or nomadic invaders and so

integration was slowed down because of conquest by culturally different people

(Lieberman 2003: 79).

Lieberman

(2003: 44-5) presents a model of the causes of integration, but he is also

careful to note that:

External

and domestic factors remained influential throughout the period under study,

but their relative weights and interconnections varied widely by time and

place. I therefore argue less of a single lockstep pattern than for a loose

constellation of influences whose local contours must be determined empirically

and without prejudice.

His model is described thus (Lieberman

2003: 44-5) :

…: External, including

maritime, factors enhanced the economic and military advantages of privileged

lowland districts. In reciprocal fashion, multicausal

increases in population, domestic output, and local commodification aided

foreign trade, while widening further the material gap between incipient

heartlands and dependent districts. So too, by stimulating movements of

religious and social reform and by strengthening transportation and

communication circuits between emergent cores and outlying dependencies,

economic exchange enhanced easch core’s cultural

authority. As warfare between cohering polities grew in scale and expense, and

as the subjugation of more alien populations aggravated problems of imperial

control, those principalities that would survive were obliged systematically to

strengthen their patronage and military systems, to expand their tax bases, and

to promote official cultures over provincial and popular traditions. Insofar as sustained warfare increased popular

dependence on the throne, it heightened the appeal of ethnic and religious

patterns championed by the capital. Pacification and military reforms also had

a variety of unplanned economic and social effects generally sympathetic to

integration. ….

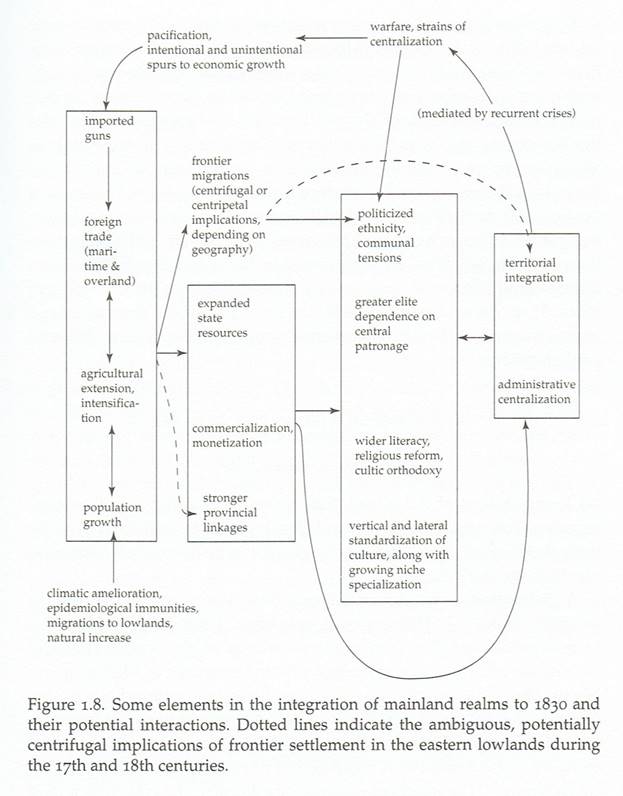

And he presents a diagram that also shows the

effects of climate change and epidemic diseases (Lieberman 2003:65):

Lieberman’s

model is probably relevant for earlier waves of political integration and state

expansion of the sort we are considering in Mesopotamia, Egypt and the early

Central PMN. His contention that external invasions slow down integration is

somewhat supported by the case of Egypt, where there relatively fewer

incursions. China, despite being exposed to Central Asia steppe nomads and

forest conquerors from Manchuria, managed to have some upsweeps that were

caused by internal dynastic processes.

And the Khmer Empire never really recovered after its first charter floration because its stronger and better integrated

neighbors (Siam and Vietnam) were able to prevent the reformation of a strong

Cambodian state. Lieberman’s model, when combined with the factors of the

demographic structural approach that explain state breakdown, provides us with

the best overall model for explaining waves of political consolidation, but it

does not explain well the rise of the West and the huge upsweep that was

the British Empire. Though Lieberman is

careful to consider the effects of economic integration and commodification on

local integration, he does not explain how centrality in global circuits of

trade and investment could eventually lead to the modern hegemonies.

Types

of Upsweeps

So we find five different kinds of

upsweeps:

1. semiperipheral

marcher state (SMS), a

polity that is in a semiperipheral position within a regional system conquers a

large area and produces a territorial upsweep;

2. peripheral

marcher state (PMS), in

which a polity that is peripheral in a regional system conquers the core, (e.g.

the Mongol Empire).

3. mirror-empire

(ME), in which a core state that is under pressure from a non-core polity

carries out a territorial expansion

4. internal

revolt (IR), a state

formed by an internal ethnic or class rebellion, such as what Yoffee (1991) argues for the Akkadian Empire, or the Mamluk Empire

5. internal

dynastic change (IDC), a coup carried

out by a rising faction within the

ruling class of a state leads to a territorial expansion.[15] The first three types involve relations among

polities, whereas the last two are mainly due to processes operating within polities.

Our review of the upsweeps also suggests

that there have been different kinds of semiperipheral marcher states that have

different combinations of the features discussed above. The summary of our

efforts to find evidence for each case is contained in the Appendix for this

article.[16] The effort to locate evidence in favor of, or

against, the semiperipheral origins of the upsweeps has been more difficult for

the earlier cases because evidence for them is circumstantial or lacking. Thus

the categorization of the origins of upsweeps must be qualified in terms of the

degree of certainty.

Table 1 shows the twenty-one cases

identified as empire upsweeps in our quantitative study (Inoue et al 2012). It also shows the results of our effort to

categorize each of these upsweeps into the five types of polity upsweeps

outlined above.

The Mongol empire is shown twice in

Table 1 because it was important for both the East Asian and the Central PMNs,

but it is not counted twice in Table 2 below. The first three upsweeps in Table

1 are from the Mesopotamian regional world-system (see also Figure 2 above).

Mesopotamia

2800 BCE to 1500 BCE

|

Peak Year |

Peak

Size (Sq.

Megameters) size |

Polity

name |

Type

of Upsweep |

|

-2400 |

0.05 |

probably an IDC |

|

|

-2250

|

0.8 |

SMS

and IR |

|

|

-1450 |

0.3 |

SMS |

Egypt 2850 BCE to 1500

BCE

|

Peak Year |

Peak

Size (Sq.

Megameters) |

Polity name |

Type of Upsweep |

|

-2400 |

0.4 |

probably

an IDC |

|

|

-1850 |

0.5 |

IDC |

|

|

-1650 |

0.65 |

SMS and IR |

Central

PMN 1500 BCE to 1991AD

|

Peak

Year |

Size Sq. Megameters |

Polity

name(s) |

Type

of Upsweep |

|

-1450 |

1 |

IDC |

|

|

-670 |

1.4 |

ME |

|

|

-480 |

5.4 |

SMS |

|

|

117 |

5 |

SMS |

|

|

750 |

11.1 |

Islamic

Empires |

SMS |

|

1294 |

29.4 |

PMS |

|

|

1936 |

34.5 |

SMS |

East

Asia 1300 BCE to 1830 AD

|

Peak Year |

Size in Sq. Megameters |

Polity name(s) |

Type of Upsweep |

|

-1050 |

1.25 |

Probably SMS |

|

|

-176 |

4.03 |

* |

|

|

Mongol-Yuan (same as above in Central

System. Counted only once) |

|||

Table 1:

World-system position origin of those polities that produced territorial

upsweeps

Table 2:

Count of the 21 upsweep cases in Table 1 with regard Type of Territorial Upsweep

The Egyptian 2nd- 5th dynasties[17]

The

increase in territorial size was based on that

wave of unification and state formation of Egypt that started toward the

end of the 2nd dynasty. [18]

Van de Mieroop’s (2011:50) review of the Old Kingdom

literature on the causes of the unification of lower and upper Egypt presents

different views, concluding that the most likely scenario was one in which “a regional elite expanded its power

gradually over the entirety of the country by eliminating other elites…” He says that scholars

agree that territorial unification happened, but no one explains well why it

happened. He contends that the most

likely of the competing interpretations focusses on internal state formation

processes that led to territorial expansion rather than external causes. Increased state formation toward the end of

the 2nd dynasty, and territorial and state expansion in the 3rd

through 5th dynasties are indicated by architectural evidence of the

enlarging monumental/mortuary buildings (see

also Beaujard 2112:176). [19]

The Egyptian 2nd- 5th dynasties[17]

The

increase in territorial size was based on that

wave of unification and state formation of Egypt that started toward the

end of the 2nd dynasty. [18]

Van de Mieroop’s (2011:50) review of the Old Kingdom

literature on the causes of the unification of lower and upper Egypt presents

different views, concluding that the most likely scenario was one in which “a regional elite expanded its power

gradually over the entirety of the country by eliminating other elites…” He says that scholars

agree that territorial unification happened, but no one explains well why it

happened. He contends that the most

likely of the competing interpretations focusses on internal state formation

processes that led to territorial expansion rather than external causes. Increased state formation toward the end of

the 2nd dynasty, and territorial and state expansion in the 3rd

through 5th dynasties are indicated by architectural evidence of the

enlarging monumental/mortuary buildings (see

also Beaujard 2112:176). [19]

Figure 4: Largest states and empires in the

Egyptian PMN, 2850 BCE-1500 BCE

More on 17th

and 18th dynasties here

dissertation, Interdepartmental

archaeology program, UCLA.

_____. 2005. “Power is in

the Details: Administrative Technology and the Growth of Ancient

Near Eastern Cores.” Pp. 75-91 in The Historical Evolution of World-Systems,

edited by

Christopher Chase-Dunn and E. N.

Anderson. New York and London: Palgrave.

Anderson,

David G. 1994 The Savannah River Chiefdoms. Tuscaloosa: University of

Alabama Press.

Anderson, E.

N., and Christopher Chase-Dunn.

2005. “The Rise and Fall of Great

Powers.” Pp. 1-

19 in C. Chase-Dunn and E. N.

Anderson (eds.): The Historical Evolution of World-Systems.

New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Pp. 1-19.

Barfield, Thomas J. 1989 The

Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China. Cambridge, MA.: Blackwell

Beaujard, Philippe.

2005 The Indian Ocean in Eurasian and African World-Systems Before

the

Sixteenth Century・ Journal of World History 16,4:411-465.

Eurasian

World-System.”Journal of World History

21:1(March):1-43.

_______________ 2112

Les mondes de l’océan

Indien Tome II:

L’océan Indien, au coeur des

globalisations de l’ancien Monde

du 7e au 15e siècle. Paris: Armand Colin

Carneiro, Robert L.

1978. "Political Expansion

as an Expression of the Principle of Competitive

Exclusion." Pp. 205-23 in Origins of the State: the Anthropology of Political Evolution,

edited by

Ronald Cohen and Elman R. Service. Philadelphia:

Institute for the Study of Human

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher. 1988 "Comparing World Systems: Toward a

Theory of Semiperipheral

Development." Comparative

Civilizations Review 19(Fall):29-66.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Andrew K. Jorgenson, “Regions and Interaction Networks: an institutional

materialist perspective,” 2003 International Journal of Comparative Sociology 44,1:433-450.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Thomas D. Hall 1993 "Comparing world-systems: concepts and working

hypotheses" Social Forces 71,4 (June).

_____________________________. 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis Alvarez and

Thomas D. Hall 2006 “Waves of

globalization and semiperipheral

development in the ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian

world-systems. Pp. 114-138 in Globalization and Global History edited

by Barry K. Gills and

William R. Thompson. London:Routledge.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Bruce Lerro 2013 Social Change: Globalization From the Stone Age to the Present.

Chase-Dunn, C. E.

N. Anderson, Hiroko Inoue and Alexis Álvarez

2015 “The Evolution of

Economic Institutions: City-states

and forms of imperialism since the Bronze Age”

Presented at the International Studies Association 2015

annual meeting, New Orleans IROWS

Working Paper #79 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows79/irows79.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and Marilyn Grell-Brisk

2016 “Uneven and Combined Development in

the

Sociocultural

Evolution of World-Systems” in Alex Anievas and Kamran Matin (eds.)

Historical

Sociology and World History. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield

Chase-Dunn, C and Bruce Lerro 2014 Social Change: Globalization

from the Stone Age to the

Present. Boulder,

CO: Paradigm

Boundaries, University of

California-Riverside, March 5.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Hiroko Inoue 2016”Size upswings of

cities and polities: comparisons of world-

systems since

the Bronze Age” Presented at the annual meeting of the International

Studies

Association, Atlanta, Georgia, March

16, 2016

Collins,

Randall. 1981 “Long term social change

and the territorial power of states,” Pp.

71-106 in

R. Collins (ed.) Sociology Since Midcentury. New York:

Academic Press.

Dee, Michael,

David Wengrow , Andrew Shortland

, Alice Stevenson , Fiona Brock , Linus Girdland

Flink and

Christopher Bronk Ramsey 2013 “An absolute chronology

for early Egypt using

radiocarbon dating and Bayesian

statistical modelling” Proceedings of the Royal Society A 469:

20130395.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2013.0395

Ferguson, R.

Brian, and Neil L. Whitehead, eds.

1992 War in the Tribal Zone: Expanding

States and

Indigenous

Warfare. Santa Fe, NM:

School of American Research Press.

Fleisher,

Jeffrey; Paul Lane; Adria LaViolette; Mark Horton;

Edward Pollard; Eréndira Quintana

Morales; Thomas Vernet;

Annalisa Christie; Stephanie Wynne-Jones. 2015. “When Did the

Swahili Become Maritime?” American Anthropologist 117:100-115.

Goldstone,

Jack. 1991. Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World.

Berkeley: University of

Hall, Thomas

D. 2000 "Frontiers, Ethnogenesis, and World-Systems: Rethinking the

Theories."

Pp. 237-270 in A World-Systems Reader: New Perspectives on Gender, Urbanism, Cultures,

Indigenous

Peoples, and Ecology edited by Thomas D. Hall. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Thomas D. Hall 2006 “Global social change in the

long run” Chapter 3

Cohn, Norman 1993 Cosmos, Chaos and the

World to Come: the Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith. New

Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.

Fang, Hui,

Gary M. Feinman and Linda M. Nicholas 2015 “Imperial

expansion, public investment Flammini, Roxana

2008 “ANCIENT

CORE-PERIPHERY INTERACTIONS: LOWER

NUBIA

DURING MIDDLE KINGDOM EGYPT (CA. 2050-1640 B.C.)” jOURNAL

OF wORLD-sYSTEMS

rESEARCH vOL 14, nUMBER 1.

http://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/jwsr/article/view/348

Hamalainen, Pekka 2008 The Comanche

Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hassan,

Fekri A.1988 “The predynastic

of Egypt” Journal of World Prehistory Vol. 2, Number 2.: 135-

_____________ 1997 “Holocene paleoclimates of Africa”

African Archaeological Review 14,4: 213-230

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1022255800388

Hawley, Amos. 1950. Human Ecology: A Theory of

Community Structure. New York: Ronald

Honeychurch, William 2013 “The Nomad as State Builder: Historical

Theory and Material Evidence

from

Mongolia” Journal of World Prehistory

26:283–321

Hopkins,

Terence K. and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1987 "Capitalism and the

Incorporation of New

Zones Into the World-economy." Review 10:4(Fall):763-779.

Ibn Khaldun. 1958 Muqaddimah. Tr. Franz Rosenthal. New York: Pantheon.

Inoue,

Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez,

Kirk Lawrence, Anthony Roberts, Eugene N Anderson and

Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2012 “Polity scale shifts in world-systems since the Bronze Age: A

comparative inventory of upsweeps and collapses” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 53,3: 210-229.

Inoue,

Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez,

Eugene N. Anderson, Andrew Owen, Jared Ahmed and Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2015 “Settlement Scale Shifts Since the Bronze Age: Upsweeps, Collapses and Semiperipheral Development” Social Science History Volume 39 number 2, Summer

Kirch, Patrick 1984 The

Evolution of Polynesian Chiefdoms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Kradin, Nikolay N. 2002. “Nomadism, Evolution and

World-Systems: Pastoral Societies in

Theories of Historical

Development.” Journal of World-Systems

Research, 8,3.

Lattimore,

Owen 1940 Inner

Asian Frontiers of China. New

York: American Geographical Society,

republished

1951, 2nd ed. Boston: Beacon Press.

______________

1980 "The Periphery as Locus of

Innovations." Pp. 205-208 in Centre and

Periphery: Spatial Variation in Politics, edited by Jean Gottmann. Beverly Hills: Sage.

La Lone,

Darrell. 2000 "Rise, Fall, and Semiperipheral

Development in the Andean World-System"

Journal of World-Systems Research

6:1(Spring):68-99

Lawrence, Kirk. 2009 “Toward a democratic and collectively rational global

commonwealth:

semiperipheral

transformation in a post-peak

world-system” in Phoebe Moore and Owen

Worth, Globalization and the Semiperiphery: New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Lieberman, Victor. 2003. Strange

Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830.

Vol. 1: Integration on the

Mainland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

. 2009. Strange

Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830. Vol

2:

Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and

the islands. Cambridge:

Mann, Michael 1986. The

Sources of Social Power: A History of Power from the Beginning to A.D. 1760.

Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

McNeill, John R. and William H. McNeill 2003 The Human Web. New York: Norton.

Morris, Ian 2010 Why

The West Rules – For Now. New York: Farrer, Straus and Giroux

_____. 2012 The Measure of Civilization.

Princeton: Princeton University Press

process. The History of the East) Moscow: Territory of the Future

Publishing house

Quigley, Carroll 1961 The Evolution of Civilizations.

Indianapolis: Liberty Press.

Renfrew, Colin 1975 “Trade as Action

at a Distance: Questions of Integration and Communication”

In Ancient Civilization and Trade. Jeremy A. Sabloff

and C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, eds. Pp.

3-59. vol. 3.

Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Sanderson, Stephen K. 1990 Social Evolutionism. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Scheidel, Walter 2010 “The Xiongnu and the comparative study of empire”

Princeton/Stanford _____. 1978b "Size and duration of empires:

growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600 B.C." Social Science

_____.1979 "Size and duration of empires:

growth-decline curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D." Social

_____.1997 “Expansion and contraction patterns of large

polities: context for Russia.” International

Studies Quarterly 41,3:475-504.

Toynbee, Arnold. 1946. A Study of History (Somervell abridgement),

Oxford: Oxford University

Turchin, Peter. 2003. Historical Dynamics. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Turchin, Peter. 2006. War and Peace and War. New York: Pi

Books.

___________ 2009 “A theory for

formation of large empires” Journal of Global History 4 , pp. 191–

____________ 2015 Strange Parallels:

Patterns in Eurasian Social Evolution. Journal

of World-Systems

Research,

[S.l.], p. 538-552, aug. http://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/jwsr/article/view/405

___________ 2014 “The Circumscription Model of the Egyptian State” Social

Evolution Forum

Turchin, Peter, Jonathan M. Adams, and Thomas D. Hall 2006.

“East-West Orientation of

Historical Empires and Modern

States.” Journal of World-Systems

Research.12:2(December):218-

Turchin, Peter and

Sergey Nefadov. 2009. Secular Cycles. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Van De Mieroop,

Marc 2011 A History of Ancient Egypt.

Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell

World-Economy in the Sixteenth

Century. New

York: Academic Press.

__________________. 1976 “Semiperipheral countries and the

contemporary world crisis” Theory

Wengrow, David 2006 The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa,

10,000 to 2650 BC. Cambridge University Press, New

York

World-Systems Archive

(http://wsarch.ucr.edu)

Wilkinson, David. 1987 "Central

civilization" Comparative Civilizations Review 17:31-59 (Fall).

_____. 1991 “Cores, peripheries and civilizations” Pp.113-166 in C. Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall

(eds.) Core/Periphery Relations in Precapitalist Worlds. Boulder, CO: Westview.

http://www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/books/c-p/chap4.htm

Yoffee, Norman 1991

“The collapse of ancient Mesopotamian states and civilization.” Pp. 44-68 in

Norman

Yoffee and George Cowgill (eds.) The Collapse of

Ancient States and Civilizations.