High Bar

Rules of Thumb for

Time-Mapping Systemic

Human

Interaction

Networks

Eastern

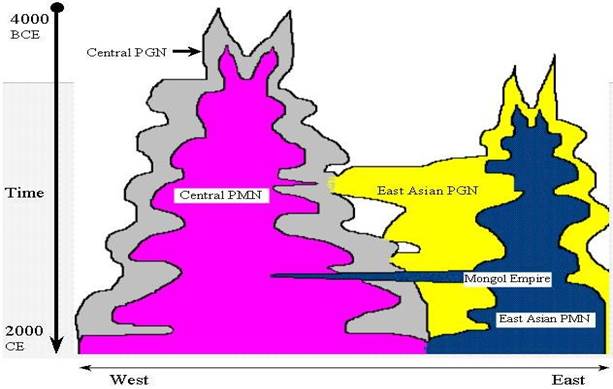

and Western Systemic Spatio-temporal Networks

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Hiroko Inoue and Teresa Neal

Institute for

Research on World-Systems (IROWS)[1]

University of

California-Riverside

Paper to be presented at the

ISA-supported Workshop on

Systemic Boundaries,

Institute for Research on World-Systems, March 5, 2016

This is IROWS Working Paper #105

available at irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows105/irows105.htm

DRAFT v. 2/21/16, 8208 words

We propose a general set of decision

rules for specifying the spatial and temporal boundaries of interpolity

systems in anthropolical comparative perspective.

What is needed is a systematic method for separating significantly (high bar)

independent cases that can be the basis of comparative analysis and for

determining when and where regional systems merged with one another to become

the global system that we have today. We

try to specify rules that will work across the anthropological spectrum of

human polities from nomadic foraging bands to the single global society of

today.

We also describe David Wilkinson’s

approach to the spatio-temporal bounding of state

systems and trade ecumenes since the Bronze Age.

We briefly discuss the concepts that

are needed for the bounding task:

- systemness,

- place-centricity,

- fall-off and

- exogenous impacts.

And we specify rules of thumb for systemic

connectedness for four types of interaction that typically have different

spatial scales:

- bulk goods networks,

- political-military networks,

- prestige goods networks and

- information/communications networks.

Bounding

Sociocultural Regions

Most

efforts to bound human sociocultural regions rely on the notion of homogeneity.

So the Handbook of North American Indians

divides space up according to alleged institutional and artifactual

similarities among indigenous groups. Civilizationists

long attempted to designate cultural regions by studying similarities and

differences in ideology (Melko and Scott 1987).. The problem with this approach is that it is

well known-that interaction produces both similarities and differences. So

groups that are interacting with one another frequently differentiate their

identities and often specialize in certain activities that come to form a

regional division of labor. These tendencies greatly complicate approaches that

try to characterize regions in terms of cultural similarties,

and they suggest that interactions and connectivity is a better approach

(Wilkinson 1993; Chase-Dunn and Jorgenson 2003).

Sociocultural Systemness

Systemic interaction in human

sociocultural systems is defined as two-way and regularized interaction that is

important for the reproduction or change of local social structures (Friedman

and Rowlands 1977; Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997). Sociocultural systemness

means largely self-contained interaction among a set of interdependent entities

that produces coherence and observable patterns.[2] Systemness is a variable. The

degree of systemness generally declines with

distance. Social scientists divide into “splitters” who emphasize the

uniqueness and autonomy of local social structures and “lumpers” who emphasize

the importance and systemic nature of long-distance connections. The intent

here is to propose some general rules for specifying the spatio-temporal

boundaries of largely separate and independent whole social systems that can be

accepted by those social scientists who wish to test propositions about the

causes of social change by comparing cases.

Since all polities[3] interact with adjacent neighboring

polities, the establishment of spatio-temporal

systemic boundaries requires using a place-centric approach.[4] A focal location must be chosen in order to answer the

question of what is included within this system and what is outside of it? The focal location could be a household or a

settlement or a polity or a set of adjacent polities. Since all known interpolity systems display systemic interaction among

directly adjacent territorial polities, we propose that the best way to

designate a focal locale is to pick five adjacent autonomous territorial

polities. These we shall call the focal

five.

Designating

the focal locale as five adjacent polities allows us to use a combination of

direct and short (one degree of separation) indirect linkages for designating

expansions of a system or mergers between two formerly separate systems. When a system expands the new connection is

typically formed between one of the polities in the focal locale with a polity

out on the edge, but not all of them. So, for example, when the Mesopotamian and Egyptian state

systems became linked, it was because some of the states (not all of them) in

the Mesopotamian system began having direct political-military relations with

Egypt. But not all the states in the Mesopotamian system did this. And the ones

that started direct warring with Egypt did not directly link with all the

states in the Egyptian interpolity system (e.g.

Kush). Allowing one degree of separation solves this problem and we shall do

that for each of the different kinds of systemic interaction discussed below.

Robert Hanneman et al 2016 propose an alternative method that uses data on whole

multidimensional networks and formal network analysis of modularity to

empirically locate systemic regions of concentrated interaction and

connectedness . This is a promising alternative approach to spatially bounding

interaction systems that should be compared with the place-centric approach

proposed here.

When

all human polities were nomadic foraging bands, before about 12,000 years ago,

there was already a single global network because all bands interacted with

their neighbors, but there was not yet a single global system. Systemic

interaction networks were small because the consequences of events and

activities at any point did not travel very far in space. Fall-off is the concept that

archaeologists (e.g. Renfrew 1975, 1977, Renfrew and Cherry 1986) have used to

comprehend the decline of effects over distance. Fall-off curves were short

when all polities were composed of nomadic foragers, and they may have become

somewhat shorter once sedentism emerged. Rather than

moving people to resources, as nomads did, sedentary people increased exchanges

among groups, using some goods that had been produced by people in other

groups. As exchange networks expanded,

the fall-off curve got longer. The question of systemness

requires a decision about where on the fall-off curve to draw a line. When the

fall-off curve gets to zero there are no consequential interactions between

locations A and B. Things that happen at A do not at all effect what happens as

B. So all systemic networks are located within the domain of their fall-off

curves. But systemness requires more than just

occasional or slight consequences.[5]

Exogenous vs. Endogenous Impacts

Both time and space are important

for determining sociocultural systemness. An

exploratory expedition or an incursion that does not result in regularized

alliance connections or two-way trade between the region of origin and the

region of arrival does not constitute systemic interaction. The arrival of

genetic materials (food crops), exotic tools or ideas, does not necessarily

constitute a systemic connection. These can be exogenous impacts and

they may have large one-time consequences for a local system, but not be part

of that system. A systemic connection is

developed when two regions come to expect future interaction or when people in

one region become dependent upon inputs coming from another region. Both

equal (symmetric) and unequal (asymmetric) exchange can be systemic. Two-way exchange does not necessarily mean

equal exchange. Repeated coercive

extraction of resources constitutes systemic interaction. Threats are an important type of interaction.

But human sociocultural systems are

subsystems within larger biological and geophysical systems (Hornborg and Crowley (2007). Human interactions with the

biosphere and the geosphere have always been, and continue to form important

constraints and to pose challenging opportunities for polities. And non-human

species often display forms of behavior that are similar to those known in

human world-systems (territoriality, warfare, demographic cycles, a complex

division of labor, etc.). Whereas geophysical processes such as global climate

change were once safely considered as exogenous causes of human social change,

that is no longer the case.

Nevertheless, it is important to develop methods for distinguishing

substantially autochthonous human sociocultural systems for purposes of

comparative study and hypothesis testing. When exogenous impacts are a

plausible cause of social change, as with climate change, these possible causes

must be included in models and in comparative research designs.

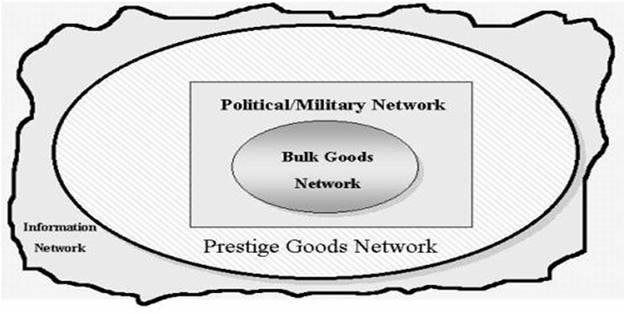

Nested Networks and Sociocultural Systemness

The specification of decision rules

is somewhat complicated by the observation that different kinds of important

interaction often have dissimilar spatial scales, and so may require somewhat

different decision rules. Thus we will propose decision rules for four

different kinds of potentially systemic interaction that take into account the

nature of the interaction processes and how they are affected by space and time.

These four networks are bulk goods systems, political-military systems, prestige

goods networks and information/communications networks. They are understood to

be spatially nested in most premodern whole systems (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Nested Systemic Interaction Networks

This nested approach is already one

step toward distinguishing between degrees of systemness

because bulk goods interaction networks and political/military networks are

always systemic, whereas the larger prestige goods and information networks are

only systemic in some cases.

The world-systems perspective in

both the Frankian and Wallersteinian versions have

emphasized the importance of core/periphery relations. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997)

agreed that interpolity hierarchies are often crucial

for prehension of the nature particular systems and

for explaining social change, but they also allow for the possibility that some

small-scale world-systems in the past have not had core/periphery hierarchies

based on asymmetrical interactions among polities. This allows for the study of

the emergence and evolution of core/periphery hierarchies. Chase-Dunn and Hall

also point out that the issue of whether or not interpolity

interactions are exploitative or not needs to be asked at each level of the

nested interaction networks.

Bulk

Goods Systems

Food and other resources that are

heavy relative to their “value” (so-called “bulk” goods) do not travel very

far, but they are systemic in all human polities.[6] Most bulk goods

are obtained locally, but in many interpolity systems

some bulk goods are obtained across polity boundaries, either by trade or

raiding, or both. Eventually the bulk goods network caught up with the larger

networks to produce the global system of today. But in earlier eras systemic interaction

networks were nested as depicted in Figure 1.

Gills and Frank (1991; see also Frank

and Gills, 1993) proposed that polities that exchange surplus product with one

another are systemically connected and that these connections extend to all the

polities that are indirectly connected. By this logic they assert that there

was a single Afroeurasian-wide world system that

became connected with the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century CE. They

also imply that both trade and information/communications flows are important

aspects of systemness (see below). The observation that all polities are in

interaction with their neighbors and so, if we count all indirect connections,

there is a single global (or hemispheric) network is correct. But, as Charles

Tilly (1984:62) observed, indirect

connectedness does not necessarily constitute systemness. It all depends on the rate at which the

consequences of connections decreases over space – the fall-off curve. Both bulk and prestige goods involve surplus

product transfers and interdependence, but these different kinds of exchange

have very dissimilar spatial ranges.[7]

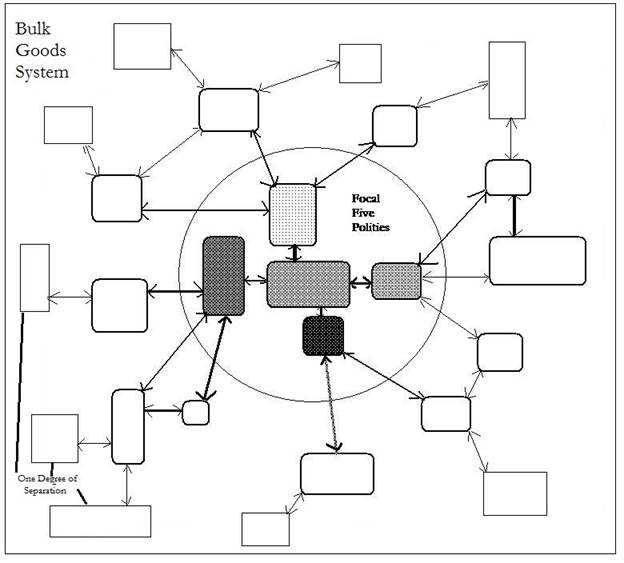

How should the spatial boundaries of the bulk goods system

be delimited? The focal locale is

conceived as five autonomous adjacent polities. Starting from this focal locale,

all other polities that are the source of bulk goods constituting at least five

percent of total bulk goods consumption

and obtained at least once in an average year by any of the five focal polities

are part of the systemic bulk goods network (see Figure 2). This usually

includes all, or most, adjacent polities and some polities that are

non-adjacent. We also include polities

that are not directly connected with the focal five, but that are connected by

one degree of separation. How far the bulk goods network extends is a function

of transportation technology and the institutional nature of production and

exchange.

Many scholars have pointed out

that the sovereign boundaries between polities were not as institutionalized in

the past as they have become today (e.g. Hall 2016). While this is obviously

true, it does not mean that earlier polities were not territorial. Even nomadic

hunter-gatherers and pastoralists have notions of collective property regarding

use rights over places. In ethnographically-known systems of sedentary

foragers, such as existed in precontact California,

trespass involving the unauthorized use of gathering or hunting sites was a

major cause of disputes and warfare among tribelets. In precontact

Hawaii territorial boundaries between autonomous chiefdoms and regions within

chiefdoms (ahuapua) were formally marked by posts on

trails. So the idea that boundaries

between polities were so amorphous in premodern worlds that the notion of an interpolity system is inappropriate simple does not hold

water. Certainly there were many regions

in which boundaries were contested, as they still are, but the basic logic of

geopolitical competition for territory was already operating among nomadic hunter-gatherers

and also operated when the boundaries were fuzzy.

Figure 2: The Bulk Goods Systemic Network of Five Focal Polities

The Political/Military System

Interpolity political-military systems are sets of polities that

make war and alliances with one another.[8]

As with other networks, this requires specification of a focal locale, because

all polities make war or alliances with neighboring polities. Systemness at this level is about the ability of polities

to provide protection for their members from attacks from other polities and

the distances over which power can be projected in order to force compliance or

to produce influence. Warfare is understood to involve both actual attacks and

threats of attacks. Alliances are

understood as agreement to provide material support and actual provision of

such support. Formal agreements and informal understandings involving the

exchange of diplomats and/or cross-polity marriages are sometimes indicators of

such alliances.[9]

The big issue here is whether or not

political/military systemness can extend beyond

direct interaction. David Wilkinson’s method of bounding interpolity

interaction systems requires direct and sustained interactions, which is a very

high bar of systemness. We find it plausible to

contend that systemic political/military interaction should include at least

one degree of separation, meaning that the neighbors of one’s neighbors also

usually have an important impact on security, geopolitical processes and

opportunities to obtain resources.

Wilkinson describes the merger of

the Egyptian and Mesopotamian interstate systems to form what he calls Central

Civilization as follows: “The merger of the

Mesopotamian and Egyptian interpolity

systems began as a result of Eighteenth Dynasty Egypt’s invasions, conquests,

and diplomatic relations with states of the Southwest Asian (Mesopotamian)

system -- first of all Mitanni, then the

Hittites, Babylon, and Assyria. The

signal event was Thutmosis

I’s invasion of Syria in about 1505 BCE.

The fusion of the systems began then but enlarged and intensified until

1350 BCE. Thutmosis III’s many campaigns in Syria and the

establishment of tributary relations, wars and peace-making under Amenhotep II,

as well as the peaceful relations and alliance with Mitanni by Thutmosis IV, eventually

led to Egyptian hegemony under Amenhotep III” (Wilkinson personal communication

Friday, April 15, 2011).[10]

Regarding the incorporation of the

Indic PMN into the Central PMN, Wilkinson does not count the Alexandrian

conquests in India because that linkage was temporary. So the Indic PMN was first permanently

connected to the Central PMN in CE 1008 when Mahmud of Ghazni

conquered North India.[11]

By Wilkinson’s rule the East Asian

interstate system did not become permanently connected to the Central PMN until

the European states established treaty ports in China in the 19th

century CE. The PMN connection between

the East and the West formed by the Mongol Empire was temporary. [12] The decision to

allow one degree of indirect connection would probably result in an earlier

date for the merger of the Central and East Asian PMNs. Allowing one degree of separation makes it

easier to depict the merging of two state systems while still retaining the

focal locale approach developed here. If only direct connections count, Egypt

would get added to the Central PMN, but not the adjacent states that were part

of the Egyptian PMN prior to the merger.

The abstract formulation of our

geopolitical connectedness principle is as follows: beginning with a focal five

adjacent territorial polities, both direct conflicts or strong alliances with

any of the focal five constitute systemness and so

does one degree of separation. The neighbors of neighbors affect decisions and

opportunities, and so they are included in the PMN. This is a slight

modification of what appears to be Wilkinson’s decision rule to include only

direct connections. But the spirit of

the high bar of connectedness is honored here.

The Prestige Goods Network

Prestige goods are high value goods that are worth

transporting long distances. They are generally light and resistant to decay,

which makes them transportable over long distances.[13] The most famous historical prestige

goods network is the East/West caravan trade across the several routes that

were called the Silk Road and the maritime routes around South Asia that

connected the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean with East and Southeast Asia.

These routes emerged well before the Han and Roman Empires. Archaeologists know

that valuables were traded over long distances in the precontact

Americas as well.

Prestige goods are systemic in some systems but not in others. Economic anthropologists

(e.g. Johnson and Earle 2000:

257-258) distinguish between staple and wealth finance systems. In staple

systems bulk goods are exchanged and accumulated by elites and symbols of value

do not play a big role in the processes of production, reproduction and

accumulation. Valuables may be used for decoration, but they are not important

to the political economy. This is what Wallerstein meant by “presciosities.” In wealth finance systems prestige goods

come to play an important role as storable wealth that facilitates exchange

within and between polities and may be important in reproducing hierarchies.[14]

What are good rules of thumb for determining the spatial

scale of prestige goods systemic networks? Prestige goods exchanges in small scale-systems

are often structured as “down-the-line” trade in which goods move from group to

group and there are no long-distance merchants. There are different ways in

which prestige goods can be systemic. The large literature on prestige goods systems usually points

to how local elites use their monopoly over exotic goods to shore up their

power over subalterns. If you cannot get married without this special exotic

pot and these are only available from Uncle Joe, Joe has a lot of leverage over

when you can get married and probably whom you can marry (Meillausoux

1981; Peregrine 1991; Helms 1988, 1992)). But another way that prestige goods

can be important for local social structures is when they serve as proto-money

– a storable medium of value that can be used to obtain other necessities

during times of scarcity. This use of proto-money in indigenous California

allowed trade to substitute for raiding during periods of scarcity (Vayda 1967; Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998).[15]

Flows of prestige goods are also commonly organized as

tribute payments extracted by a powerful empire or by a marcher state that

threatens an empire. The Chinese trade/tribute system was a complex combination

of trade and symbolic tribute payments that the Chinese dynasties required of

their trading partners. As with bulk goods, prestige goods exchanges can be

either symmetrical or asymmetrical mixes of coercion and cooperation.

The first issue is whether or

not imported prestige goods are playing a systemic role in the reproduction or

change of local social structures. This is best indicated by the distinction

between staple and wealth finance described above. In staple finance systems

prestige goods are unlikely to be systemic. In wealth finance systems they are

very likely to be systemic. Of course some systems combine wealth and staple

finance, and for these the call can be made by examining the extent to which

social structures are dependent on the importation or export of prestige goods.

Once this is decided the question becomes how far to include exchange partners

in the system. As with other systemic networks, there is a fall-off curve. Once again we begin with a focal five adjacent territorial

polities.

As

a rule of thumb for prestige goods in a wealth finance political economy we

propose that, when 5% percent or more of the total yearly importation of

prestige goods comes from a polity to any one of the focal five

polities, that polity should be included in the PGN. The issue of degrees of separation is not

crucial because of the nature of down-the-line trade structures. In such

systems trade goods obtained from neighbors may have passed through many hands.

If 5% by weight or more of total prestige goods imports has come to at least one of the focal

five polities from a distant polity,

that distant

polity should be considered to be within the PGN of the focal five.

The Information/Communications Network

World historian William H. McNeill (1990) noted

that information flows transmitted by humans has often had important

consequences for social change. In

response to McNeill’s prodding Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) included information

networks as one of the types of interaction that can be systemic. As indicated

in Figure 1 above, information networks in nested systems were hypothesized to be somewhat larger than

prestige goods networks. There has been very of little investigation of the

systemic nature of information networks (but see Neal 2015; 2016) and little study of how to spatially and

temporally bound them. As Neal (2016) notes, information is ubiquitous and so

the discussion in human interaction networks requires that we focus on flows of

information among groups of humans – communications. Communications flows are obviously an

important component of the reproduction and change of local social structures

in both small-scale and complex systems. The structure of attention and

communication within small groups, organizations and states is a well-known

central component of political and economic processes (Deutsch 1966). Cross-cultural

communication is an important aspect of geopolitical and economic relations in

multicultural networks. Messengers, line-of-sight signaling, multilingualism and

both sign and oral trade languages are known in even small-scale systems like

that of indigenous California. Communications technologies have reflected and

transformed the nature of historical empires (Innis 1972[1950]) and the modern

global system has been importantly impacted by the emergence of the telegraph,

the radio, the telephone and now the Internet (Hugill

1999, Zook 2005).

But is the information/communications network

itself systemic beyond the roles it plays in bulk goods, political-military and

exchange networks? Are systemic information networks usually larger than prestige goods networks because

information is even lighter than prestige goods and so has a longer fall-off

curve?

Several of the same issues raised in the

discussion of bulk goods, political-military and prestige goods networks can be

asked about information/communications networks. How much information transfer

is necessary in order to constitute systemness

according to the high bar criterion advocated above. Do information flows play

different roles in dissimilar systems in the reproduction and transformation of

local social structures? What are the typical shapes of information fall-off

curves, and at what point on the curve is it prudent to draw the line between

systemic inclusion and exclusion? Do information flows need to be two-way in

order to be systemic?

As with

other exogenous impacts discussed above, some information flows are episodic and should

not be considered as systemic. So the high bar of two-way flows is probably a

good requirement.

Information can be quantified by

counting messages. Of course some

messages are long and others are short. But, for comparisons across space and

time, counts of the number of messages allow for the estimation fall-off

curves. In small-scale systems reports of unusual events (news) spread from

group to group. Part of information fall-off is due to the decay of information

accuracy that occurs because of errors that occur when messages are translated

from one language into another.[16]

Cora DuBois’s (2007[1939]) study of the

diffusion of the 1870 ghost dance from Western Nevada (Walker River Paiute) to Native

Americans in Northern California and Southern Oregon shows how far new ideas spread

and the processes of change that occurred as an ideological innovation became

adapted to local conditions. Both the 1870 and the more famous 1890 ghost

dancers believed that the Indians that had died were going to return and that

all the whites would die, and that in order to bring on this millenarian event

believers needed to dance a special dance and sing special songs. The ghost dance has been seen by social

scientists as a “revitalization movement” in which indigenous societies were

adapting to the radical changes brought by the arrival of Europeans to their

world (Wallace 1956).

The distances involved in the diffusion of the

1870 ghost dance were probably greater than when earlier ideologies spread

across indigenous polities because some Indians had acquired the use of horses

and wagons by the 1870s --- transportation technologies that had not been

available to their ancestors. The spatial scale of the spread of the 1890s

version of the ghost dance was much larger (Smoak 2006), probably reflecting the

further lowering of transportation and communications costs for indigenous

peoples between the 1870s and the 1890s.

DuBois’s study shows that the diffusion of cult

messages among preliterate populations[17] mixed direct contacts made by prophets who

traveled to distant peoples to tell the word with down-the-line processes in

which local entrepreneurs heard about the new dances and songs and made up

their own versions. She also notes that the diffusion was uneven. Groups that

had not been very disrupted by the arrival of the whites were less likely to

become involved with the ghost dance. The old “sucking doctors” (shamans who

cured by extracting bad spirits) resisted the new “dream doctors” who preached

a nontraditional vision of the dead and encouraged women and children to

participate in the ritual dances (from which they had formerly been excluded

because of alleged spiritual dangers).

The sucking doctors in regions that were more remote, and so less disrupted, were able

to convince their co-villagers to reject the ghost dance. The local entrepreneurs mixed ideas from the

Paiute ghost dance with older cults ( e.g. Kuksu,

Bole Maru) to

produce new combinations for local, neighboring and more distant audiences, and

so the content of the rituals became modified as they traveled.[18]

This example is not ideal for the purpose of

estimating the information/communications fall-off curve for precontact America because we cannot be sure how much of

the process of information diffusion had been affected by the arrival of the Europeans.

We know that earlier cults, dances and songs had spread across linguistic

groups in indigenous California. But we do not know about the spatial

characteristics of those diffusions because they are invisible in

archaeological evidence. But the 1870

ghost dance suggests that the information network was larger than the prestige

goods network. We know from archaeological evidence that prestige goods

exchanges in late prehistoric Northern California utilized clam disk shell

beads as protomoney. These beads were produced mainly

by the Pomo who lived around Clear Lake, about 500 kilometers from the northern

edge of the clam disk bead exchange network. The farthest distance that the

1870 ghost dance is known to have traveled is about 800 kilometers from Walker

Lake to central Oregon.

Some anthropologists contend that information

traveled very far and rapidly across indigenous polities in indigenous America (Peregrine

and Lekson 2006, 2012; Smith and Fauvelle

2015) forming a continent-wide “oikoumene.” Noting inspiration from Frank’s (1998, see

also Gills and Frank 1991) idea that there was a single Afroeurasian

world system since the emergence of cities and states in Mesopotamia, Smith and

Fauvelle (2015) cite ethnohistorical

reports that seem to substantiate the idea that very long-distance

transportation and communication networks existed in Pre-Columbian North

America.[19] They

note Frank and Gills’s idea that important systemic connections based on trade and information flows should result in increasingly

synchronous waves of polity formation between connected regions. [20] Smith and Fauvelle

(2015) contend that waves of the emergence of sociopolitical complexity in precontact Southern California and the U.S. Southwest

(Arizona, New Mexico and Northern Mexico) reveal synchrony and support the

existence of systemic inter-regional connections. As noted above, the Frank and

Gills approach to systemic connectedness combines the idea of trade and

information connections, and does not explicitly consider the issue of

fall-off. Nevertheless the ethnohistorical evidence of long-distance information flows

cited by Peregrine, Lekson, Smith and Fauvelle suggests the need for closer attention to the

issue of systemness in the precontact

Americas.

We

propose that systemic information networks are most likely to be spatially

associated with prestige goods networks and to be more important in

systems that are organized around wealth finance than in those organized around

staple finance.. The rules of thumb that we

have proposed above for spatially bounding prestige goods

networks can also be used for bounding information

networks

in most cases. As with the case with prestige goods networks, the first task is

to determine whether or not two-way information/communications from distant

sources is playing a systemic role in the reproduction or transformation of

local social structures in some of the five focal polities. A strong clue is whether or not prestige

goods are playing a systemic role.

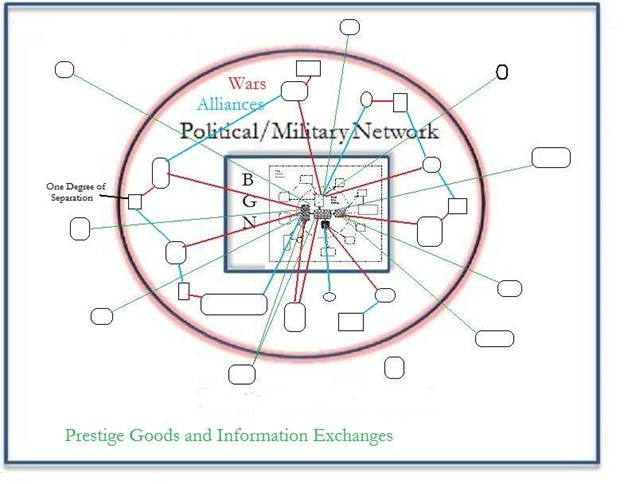

The nested networks with a focal locale of five

polities is depicted in Figure 3. The center of Figure 3 is the same as the

bulk goods network of the five focal polities shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 does

not display all the interactions, but only those that are needed for estimating

the spatial scale of the political-military, prestige goods and information

networks. As with PMNs and PGNs one degree of separation is allowed.

Figure 3: Nested networks systemically connecting five

focal polities

Spatial

Bounding of PMNs and PGNs In State Systems

The ISA-sponsored Workshop on Systemic Boundaries is intended to interrogate and develop general and

consensual decision rules regarding the spatial and temporal boundaries of

substantially independent whole interaction systems that can be used for

comparative research using these regional systems as units of analysis. The

workshop will also examine the decision rules proposed above and will examine

David Wilkinson’s decisions about when and where the Central PMN expanded and incorporated

other interstate systems.

The following tables designate some

of Wilkinson’s bounding proposals and indicate problematic cases in the spatio-temporal bounding of international systems and trade

networks. Some of the issues involve the timing of

emergent linkages among regional networks that were not yet connected with the

Central PMN (e.g. when did the East Asian and Southeast Asian PMNs become

connected?). We will also examine the implications of the problem

cases for the specification of the general decision rules proposed above.

In order to apply the place-centric

approach to regional systems Wilkinson focusses on those areas in which large

cities first emerged. So he begins the spatial bounding of regions as soon as

they have a largest city with at least 20,000 residents. The decision rules

developed above have been designed to be useful no matter how big the

settlements are, and for starting at any place where humans polities (including

bands, tribes, chiefdoms and states) are present. But Wilkinson’s systemic

regions start with those areas that have cities of a certain size. This is a

convenient approach that facilitates the task of developing scholarly consensus

regarding the designation of a set of whole systems that researchers can

compare.

|

International System |

Code |

Begin* |

Merged or Engulfed |

notes |

|

Mesopotamia |

mesop |

3400 BCE |

1500 BCE |

|

|

Egypt |

egypt |

2500 BCE |

1500 BCE |

|

|

Central |

cent |

1500 BCE |

|

|

|

Aegean |

aeg |

1600 BCE? |

600 BCE |

Or was this part of the central system after 1500 BCE? |

|

South Asian |

sas |

1800 BCE |

1100 CE |

|

|

Japanese |

japa |

600 CE |

? |

Or was this part of the East Asian system after the failed

Mongol invasions? |

|

East Asian |

eas |

1400 BCE |

1830 CE |

|

|

Mesamerican |

mesoa |

200 CE |

1500 CE |

|

|

West African |

wafr |

800 CE |

1600 CE |

|

|

Southeast Asian |

sea |

600 CE |

1500 CE |

Should what Wilkinson calls Indonesia be seen as connected with

mainland Southeast Asia? And when did Southeast Asia become connected with

East Asia? |

|

Mississippian |

missi |

1100 CE |

1500 CE |

|

|

Andean |

ande |

1300 CE |

1500 CE |

|

|

Irish? |

ire |

? |

? |

When did the Irish system become linked with the Central system? |

|

Other? |

|

|

|

|

Table 1: Chronograph of beginnings and merger/engulfment of

thirteen state systems

*Starts when largest city reaches a

population size of 20,000

|

Prestige Goods Trade Network |

Code |

Begin* |

Merged or Engulfed |

notes |

|

Mesopotamia |

mesop |

3400 BCE |

? |

|

|

Egypt |

egypt |

2500 BCE |

? |

|

|

Central |

cent |

1500 BCE |

? |

|

|

Aegean |

aeg |

1600 BCE? |

? |

When did it become part of Central

trade network? |

|

South Asian |

sas |

1800 BCE |

? |

|

|

Japanese |

japa |

600 CE |

??? |

When was Japan linked to the East

Asian trade network? |

|

East Asian |

eas |

1400 BCE |

? |

|

|

Mesamerican |

mesoa |

200 CE |

1500 CE |

|

|

West African |

wafr |

800 CE |

? |

|

|

Southeast Asian |

sea |

600 CE |

? |

Should what Wilkinson calls

Indonesia be seen as connected with mainland Southeast Asia? And when did

Southeast Asia become connected with East Asia? |

|

Mississippian |

missi |

1100 CE |

1500 CE |

|

|

Andean |

Ande |

1300 CE |

1500 CE |

|

|

Irish? |

Ire |

? |

? |

When did the Irish system become

linked with the Central trade network? |

|

Other? |

|

|

|

?? |

Table 2: Chronograph of beginnings and merger/engulfment of

thirteen prestige goods systems

*Starts when largest city reaches a

population size of 20,000

Political/military

networks (PMNs) since the Bronze Age

We begin bounding PMNs by focusing

on those five focal adjacent polities in which at least one of the focal five

contains a city with a residential population of at least 20,000 humans. These

focal five polities are the focal locale of the direct and indirect political/military

links. An alliance or war between any of the focal five polities and a distant

polity constitutes a link for the whole PMN that is being bounded and the

system extends to one indirect political/military link.

This allows one indirect link or one

degree of separation. Direct links can

exist between non-adjacent polities if they travel across other polities to

engage in warfare or the kinds of links that are involved in alliances (gift

exchanges, intermarriages, treaties, communications, diplomatic missions, etc.).

So each PMN consists of a set of five focal polities and those polities

elsewhere with which one or more of the focal polities are directly engaging in

warfare or alliances and it extends to the polities that are one degree of

separation from the focal polities.

Incursions in which a group invades

a territory but is not under the control of the polity from which it came

(Vikings, sea peoples, etc.) do not constitute a PMN link with the polity from

which they came. But if the invading

group does continue its relationship with its polity of origin then it does

constitute a systemic link.

Prestige

goods networks (PGNs) since the Bronze Age

A prestige goods network is a set of

polities that are exchanging significant amounts of

prestige goods with one another. In order to spatially bound such networks we

must pick a set of five focal polities, because all polities trade with their

immediate neighbors. Once again we begin

bounding PGNs by focusing on that set of five adjacent polities in which at

least one contains a city with a population of at least 20,000 residents.

In

the case of exchange links, systemness depends on the

amount and importance of imported and exported prestige goods for maintaining

or changing local social structures. In

some PGNs imported prestige goods facilitate interpolity

cooperation. In others prestige goods are used by local elites to control

subalterns. In both of these kinds of prestige goods systems important goods

may be obtained from indirect down-the-line trade in which goods move from

polity to polity. In such cases it makes sense to not limit the PGN boundaries

to direct links, but to allow as many indirect links as are involved in the

network of significant provisions. When 5% percent or more of the total yearly

importation of prestige goods comes from a polity

to any one of the focal five polities, that polity should be included in the PGN.

Our proposed decision rules are tentative.

We invite critical discussion and proposals for improving this formulation.

References

Abu-Lughod, Janet L.

1989 Before European

Hegemony: The World System A.D.

1250-1350. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, E. N. and Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2005. “The Rise and Fall of Great Powers” in Christopher

Chase-Dunn

and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The Historical Evolution

of World-Systems. London: Palgrave.

Arnold, Jeanne

E. (ed.) 2004 Foundations of Chumash

Complexity. Perspective in California

Archaeology, Volume 7. University of

California, Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute.

Arrighi, Giovanni,

Takeshi Hamashita, and Mark Selden 2003.

The Resurgence of East Asia: 500,

150 and 50 Year Perspectives. London: Routledge.

Beaujard, Philippe. 2005. “The Indian Ocean in Eurasian

and African World-Systems before the

Sixteenth

Century” Journal of World History 16, 4:411-465.

.

2010. “From Three possible Iron-Age World-Systems to a Single

Afro-Eurasian World-System.”

Journal

of World History 21:1(March):1-43.

Bolton, Herbert

E. 1908 Spanish Exploration in the

Southwest, 1542–1706. New York: Barnes and Noble.

________________1930

Font’s Complete Diary of the Second Anza

Expedition. Anza’s California Expeditions,4.

Berkeley: University

of California Press.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher 1998 Global

Formation: Structures of the

World-Economy. 2nd Edition. Lanham, MD:

Rowman and

Littlefield

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Alexis

Alvarez, and Daniel Pasciuti 2005 “Power and

Size: urbanization and empire formation in world-systems”

pp. 92-112 in C. Chase-Dunn

and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The historical Evolution of World-systems.

New York: Palgrave.

Chase-Dunn, C., Hiroko Inoue, Alexis Alvarez, Rebecca Alvarez, E.

N. Anderson and Teresa

Neal 2015 “Uneven

Urban Development:Largest Cities since the Late

Bronze Age”

Presented at the annual conference of the American Sociological

Association, Chicago,

August 24, 2015

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows98/irows98.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis Alvarez and Thomas D. Hall. 2006 “Waves of

Globalization

and Semiperipheral Development in the Ancient Mesopotamian and

Egyptian World-

Systems” Pp.

114-138 in Barry Gills and William R. Thompson (eds.),

Globalization

and Global History London: Routledge.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Andrew K. Jorgenson, “Regions

and Interaction Networks: an institutional

materialist

perspective” 2003 International Journal of Comparative Sociology

44,1:433-450.

Chase-Dunn, C. and T.D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Boulder, CO: Westview

Press.

Christopher Chase-Dunn and

Thomas D. Hall, 1998 "World-Systems in North America:

Networks,

Rise

and Fall and Pulsations of Trade in Stateless Systems," American Indian Culture and

Research Journal 22,1:23-72. http://wsarch.ucr.edu/archive/papers/c-d&hall/isa97.htm

Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2010 “Evolution of Nested Networks in the Prehistoric U.S. Southwest:

A

Comparative World-Systems

Approach”. Evolution: An Interdisciplinary Almanac.

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows24/irows24.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Bruce Lerro 2014. Social Change: Globalization from

the Stone Age to the

Present. Boulder,

CO: Paradigm.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Kelly M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and

Their Neighbors: A very Small World-System in Northern California

Tucson:

University of Arizona Press.

Curtin,

Philip D. 1984. Cross-Cultural Trade in World History Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Davis,

Jeffrey Edward 2010 Hand Talk: Sign Language Among American

Indian Nations. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Deutsch,

Karl W. 1966 Nationalism and social communication; an inquiry

into the foundations

of nationality, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

DuBois, Cora 2007

[1939] The 1870 Ghost Dance. Lincoln,

University of Nebraska Press.

Ekholm, Kasja and Jonathan Friedman 1982. “’Capital’ imperialism

and exploitation in the

ancient world-systems” Review 6:1

(summer): 87-110.

Frank, Andre Gunder 1998 Reorient.

Berkeley: University of California Press

Frank, Andre Gunder and Barry K. Gills

( eds.) 1993. The World

System: Five Hundred Years or Five

Thousand? London: Routledge.

Friedman, Jonathan and Michael Rowlands 1977 "Notes Towards an Epigenetic Model of

the Evolution of 'Civilization'."

Pp.

201-278 in The Evolution of Social

Systems, edited by J. Friedman and M. J. Rowlands. London:

Duckworth (also published in same title and

pages, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, 1978).

Gills, Barry K.

and Andre G. Frank 1991 “5000 Years of World System History: The Cumulation of

Accumulation” Pp. 67-113 in C.

Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds) Core/Periphery Relations in

Precapitalist

Worlds. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

http://www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/books/c-p/chap3.htm

Gills, Barry K.

and William R. Thompson 2006 Globalization

and Global History. London: Routledge.

Hall, Thomas D. 1986. "Incorporation into the

World-system: Toward a

Critique." American Sociological Review 51:3(June):390-402.

_____________2016 “Bounding the fuzzy zone at the

edges of world-systems” Paper to be presented at the ISA-sponsored

workshop on Systemic Boundaries,

UC-Riverside, March 5

Hanneman, Robert

A. 2016 “Network boundaries and systemness” paper presented at the

workshop on “Systemic Boundaries” Institute for

Research on World-Systems. University of

California-Riverside, March 5.

Helms,

Mary W. 1988. Ulysses'

Sail: An Ethnographic Odyssey of Power,

Knowledge, and Geographical

Distance.

Princeton:

_____. 1992.

"Long-distance Contacts, Elite Aspirations, and the Age of Discovery

in

Cosmological

Context." Pp. 157-174 in Resources, Power, and Interregional

Interaction, edited by

Edward

Schortman and Patricia Urban.

Hornborg, Alf and Carole Crumley (eds) 2007 The World System and the Earth System. Walnut

Creek,

CA: Left Coast Press.

Hugill, Peter J. 1999 Global Communications Since 1844:

Geopolitics and Technology. Baltimore, MD: Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Hui, Victoria Tin-Bor 2005. War and

state Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

. 2008.

“How China was ruled” China Futures, Spring, 53-65

Innis,

Harold 1972 [1950]. Empire and Communications. Toronto: University

of Toronto Press.

Inoue,

Hiroko 2016 “East Asia, Southeast Asia, Central System PMN and Trade

network” A paper to be

presented at the workshop on systemic

boundaries, University of California-Riverside, March 5

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Kirk Lawrence, Anthony Roberts, Eugene

N Anderson and Christopher Chase-Dunn

2012. “Polity scale shifts in world-systems since the

Bronze Age: A comparative inventory of upsweeps and collapses”

International Journal of Comparative Sociology http://cos.sagepub.com/content/53/3/210.full.pdf+html

Inoue, Hiroko, Alexis Álvarez, Eugene N. Anderson, Andrew Owen,

Rebecca Álvarez, Kirk Lawrence and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2015. “Urban scale shifts

since the Bronze Age: upsweeps, collapses and semiperipheral development”

Social Science History Volume

39 number 2, Summer.

Johnson,

Allen W. and Timothy Earle 2000, The

evolution of human societies, 2nd. edition. Stanford: Stanford University

Press

Lenski, Gerhard, Jean Lenski

and Patrick Nolan 1995. Human

Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology, seventh edition.

New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Lieberman,

Victor. 2003. Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia

in Global Context, c. 800-1830. Vol. 1: Integration on the

Mainland.

Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

. 2009. Strange

Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830. Vol

2: Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China,

South

Asia, and the Islands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mann,

Michael. 1986. The Sources of Social Power Volume I: A History of Power

from the Beginning to A.D. 1760. New York, NY:

Cambridge

University Press.

.

2013. The Sources of Social Power, Volume 4: Globalizations, 1945-2011.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

McNeill, William

H. 1990 "The Rise of the West

after Twenty-Five Years." Journal

of World History 1:1-21 (reprinted in

Civilizations and

World-Systems: Two Approaches to the

Study of World-Historical Change, edited by

Stephen K. Sanderson.

Walnut Creek,

CA: Altamira Press).

Meillassoux, Claude 1981 Maidens,

Meal and Money: Capitalism and the Domestic Community. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Melko, Matthew and Leighton

R. Scott (eds.) 1987 The

Boundaries of Civilizations in Space and Time.

Modelski, George 2008 “Globalization as evolutionary

process” Pp. 11-29 in George Modelski, Tessaleno Devezas and

William R.

Thompson (eds.) Globalization as

Evolutionary Process. London: Routledge.

Morris,

Ian 2013. The Measure of Civilization. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Morris, Ian and Walter Scheidel (eds.) 2008. The

Dynamics of Ancient Empires: State Power from Assyria

to Byzantium. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Neal, Teresa 2015 ““What is the

Information Network and how is it found in the pre-modern

world-system?” Presented at the

annual meeting of the California Sociological Association,

Sacramento, November 13.

_________2016 ““The Indian Ocean System: military and trade systemic

connectedness with the

Central East Asia, Southeast Asia

and Central Asia" A paper to be presented at the

workshop on systemic boundaries,

University of California-Riverside, March 5

Peregrine, Peter N. 1991

"Prehistoric Chiefdoms on the American Mid-continent: A

World-system Based on

Prestige Goods." Pp. 193-211 in Core/Periphery

Relations in

Precapitalist Worlds, edited by

Christopher Chase-Dunn and Thomas D. Hall.

Boulder, CO:

Westview Press.

________________

and Stephen H. Lekson 2006 “Southeast, Southwest, Mexico:

Continental

Perspectives on Mississippian Polities”

Pp. 351-374 in Leadership and Polity in

Mississippian

Society. Brian M. Butler and Paul D.Welch,(eds) Carbondale: Southern Illinois University

Press.

____________________________________2012”The

North American Oikoumene” Pp. 64-72 in

The

Oxford Handbook of North American Archaeology. Timothy R. Pauketat, (ed.) Oxford:

Oxford University Press

Renfrew, Colin R. 1975. "Trade as Action at a Distance: Questions of Integration and

Communication."

Pp. 3-59 in Ancient

Civilization and Trade, edited by J. A. Sabloff

and C. C. Lamborg‑Karlovsky.

Albuquerque, NM: University of

New Mexico Press.

_____. 1977. "Alternative Models for Exchange and

Spatial Distribution." Pp. 71-90 in

Exchange Systems in Prehistory, edited by T. J.

Earle and T. Ericson. New York: Academic Press.

Renfrew, Colin R. and John F. Cherry, eds. 1986 Peer Polity

Interaction and Socio-political Change.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kannan, Rajgopal, Lydia Ray and

Sudipta Sarengi 2007 “The Structure of Information Networks”

Economic Theory, 30,

119-134

SESHAT: Global History Databank http://evolution-institute.org/seshat

Sherratt, Andrew G. 1993a. "What Would a

Bronze-Age World System Look Like? Relations between

Temperate

Europe and the Mediterranean in Later Prehistory." Journal of

European Archaeology 1:2:1-57.

.

1993b. "Core, Periphery and Margin: Perspectives on the

Bronze Age." Pp. 335-345 in

Development and Decline in the Mediterranean Bronze Age,

edited by C. Mathers and S. Stoddart. Sheffield:

Sheffield Academic Press.

. 1993c.

"Who are You Calling Peripheral? Dependence and Independence in

European Prehistory."

Pp. 245-255 in Trade and Exchange in

Prehistoric Europe, edited by C. Scarre and

F. Healy. Oxford: Oxbow (Prehistoric Society Monograph).

. 1993d.

"The Growth of the Mediterranean Economy in the Early First Millennium

BC."

World Archaeology 24:3:361-78.

Schneider,

Jane. 1977 "Was There A Pre-capitalist

World-system?" Peasant Studies

6:1:20-29.

(Reprinted pp. 45-66 in Core/Periphery

Relations in Precapitalist Worlds, edited by

Christopher Chase-Dunn and Thomas D. Hall.

Boulder, CO: Westview Press). http://www.irows.ucr.edu/cd/books/c-p/cprel.htm

Smith, Erin and Mikael Fauvelle

2015 “Regional Interactions between California and the Southwest:

The

Western Edge of the North American Continental System” American Anthropologist 117,

4:710–721

Smith, Michael E. and Lisa Montiel. 2001.

“The Archaeological Study of Empires and Imperialism in

Pre-Hispanic Central Mexico” Journal of Anthropological

Archaeology 20, 245–284.

Smoak, Gregory

E. 2006 Ghost Dances and Identity

Berkeley: University of California Press

Thompson, William R. 2002 “Testing a Cyclical Instability

Theory in the Ancient Near East.”

Comparative Civilizations Review

46 (Spring): 34-78.

__________________ 2004 “Eurasian

C-Wave Crises in the First Millennium B.C.E.,” in Eugene

Anderson

and Christopher Chase-Dunn, eds., The Historical Evolution of World-Systems New

York:

Palgrave-Macmillan

___________________ 2004 “Complexity,

Diminishing Marginal Returns, and Fragmentation in

Ancient Mesopotamia.” Journal of World-Systems

Research 10, 3; 613-652.

___________________ and Andre Gunder

Frank 2005 “Bronze Age Economic Expansion and

Contraction Revisited.” Journal of World History

16, 2: 115-72

_______________________________________

2006 “Early Iron Age Economic Expansion and

Contraction

Revisited,” in Barry K. Gills and William R. Thompson (eds.), Globalization

and

Global

History. London: Routledge

Thompson, William R. 2006 “Early

Globalization, Trade Crises, and Reorientations in the Ancient

Near

East,” Pp. 33-59 in Oystein S. LaBianca

and Sandra Schram

(eds.), Connectivity in

Antiquity:

Globalization as Long-term Historical Process.

London: Equinox

__________________ 2006 ”Crises

in the Southwest Asian Bronze Age.” Nature and Culture

[Leipzig] 1:88-131.

__________________ 2006 “Climate,

Water and Political-economic Crises in Ancient

Mesopotamia

and Egypt,” in Alf Hornborg and Carole Crumley,eds., The World System and the

Earth

System: Global Socio-environmental Change and Sustainability Since the

Neolithic.

Oakland, Ca.:

Left

Coast Books

Tilly, Charles 1984 Big Structures, Large

Processes, Huge Comparisons. New York: Russell Sage

Foundation.

Turchin, Peter, Jonathan M. Adams, and Thomas D.

2006. “East-West Orientation of Historical Empires

and Modern States.” Journal of

World-Systems Research. 12:2(December):218-229.

Turchin, Peter and Sergey Gavrilets 2009.

“The evolution of complex hierarchical societies” Social Evolution

& History,

Vol. 8

No. 2, September: 167–198.

Turchin, Peter, Thomas E.Currie,

Edward A.L. Turner and Sergey Gavrilets. 2013.

“War,

space, and the evolution of Old World complex societies” PNAS October vol.

110 no. 41: 16384–16389

Appendix: http://www.pnas.org/content/suppl/2013/09/20/1308825110.DCSupplemental/sapp.pdf

Vayda, Andrew

P. 1967 "Pomo trade feasts." Pp.494-500 in George Dalton (ed.) Tribal

and Peasant

Economies. Garden

City, NY: Natural History Press.

Wallace,

A.F.C. 1956 “Revitalization movements” American Anthropologist 58: Pp 264-281.

Wallerstein,

Immanuel. 2011 [1974] The Modern

World-System, Vol. 1: Capitalist

Agriculture and the Origins of the European

World-Economy in

the Sixteenth Century. New

York: Academic. Republished 2011 by

University of California Press.

Wallerstein 1976 “Three stages of African

involvement into the world-economy” in Peter C.W.

Gutkind and Immanuel Wallerstein (eds.) Volume 1. Beverly

Hills, CA; Sage.

Wilkinson, David. 1976. "Central civilization." Comparative Civilizations Review

7(Fall):31-59.

_____. 1987 "The Connectedness Criterion and Central

Civilization." Pp. 25-29 in

The Boundaries of Civilizations in Space and Time, edited by Matthew Melko and Leighton R. Scott.

Lanham, MD.: University Press of America.

_____. 1991 "Cores, Peripheries and Civilizations." Pp. 113-166 in Core/Periphery Relations in

Precapitalist Worlds,

edited by Christopher

Chase-Dunn and Thomas D. Hall. Boulder,

CO: Westview Press.

_____. 1992 "Cities, Civilizations and Oikumenes: I." Comparative

Civilizations Review 27(Fall):51-87.

_____. 1993a. "Cities, Civilizations and Oikumenes: II."

Comparative Civilizations Review 28(Spring):41-72.

_____. 1993b. "Civilizations, Cores, World-Economies

and Oikumenes."

Pp. 221-246 in Frank and Gills (eds.)

The World System: 500 Years or 5000? London: Routledge.

_____. 1995 "Civilizations are World

Systems!" Pp. 234-246 in Civilizations

and World-Systems:

Two Approaches to the Study of

World-Historical Change, edited by Stephen K.

Sanderson. Walnut Creek, CA:

Altamira Press.

________2003. “Civilizations

as Networks: Trade, War, Diplomacy, and Command-Control.” Complexity Vol.8 No. 1, 82-86

http://eclectic.ss.uci.edu/~drwhite/Complexity/Wilkenson.pdf

_____________ 2016 “Political Linkage Archetypes” paper to be

presented at the ISA-sponsored

workshop on Systemic Boundaries,

UC-Riverside, March 5

http://wsarch.ucr.edu/archive/conferences/confname/archetype.docx

A bibliography of Wilkinson’s

publications is available at

http://wsarch.ucr.edu/archive/conferences/confname/wilkinsonbib.docx

Zook, Matthew A. 2005

The Geography of the Internet.

Malden, MA: Blackwell