Articulating the web of transnational social movements

Chris

Chase-Dunn, Anne-Sophie Stäbler

Ian

Breckenridge-Jackson and Joel Herrera

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside chriscd@ucr.edu

To be presented at the World Congress of Sociology in Yokohama, July

17, 2014. An earlier version was presented at the Global Studies Conference March 1, 2014 Orfalea

Center for Global and International Studies; University of California, Santa

Barbara. This is IROWS Working Paper #84 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows84/irows84.htm

draft v. 7-25-14; 12060 words

Abstract: How can

the New Global Left coalesce to once again address emergent global crises? Our

research on transnational social movements and global civil society

investigates the potential for a network of radical social movements to come

together to play an important role in world politics in the coming decades. The

histories of united and popular fronts are particularly relevant to

contemporary and near-future situations. The world-systems perspective sees the

evolution of global governance and the capitalist world economy as driven by a

sequence of world revolutions in which local rebellions that are clustered

together in time pose threats to the structures of global power. Our study

seeks to understand how this is happening in the early 21st century.

This paper studies the potential for transnational social movements and progressive regimes to transform the capitalist world-system into a more humane and democratic world society within the next fifty years. In order to investigate this potential we focus on the interconnections between existing movements and the processes by which movements have merged, collaborated and articulated in the past. We also discuss the potential for the formation of capacious organizational instruments that can have consequences for the nature of the world-system in the next decades. The general logic of coalition formation is considered and the literature on coalitions within and among social movements is reviewed. The focus here is on the whole world polity, but the much larger literature on movement coalitions within national societies is considered with an eye to implications for understanding processes of convergence and divergence among transnational social movements. The histories of united fronts and popular fronts are considered as to their relevance to the contemporary and near future situation. The contentious relationship between antisystemic social movements and reformist and antisystemic governments is also considered. And we hazard some guesses about which of the existing social movement coalitions might be able to forge a more formidable assault that could seriously alter the existing institutions and structures of the world-system.

The

comparative evolutionary world-systems

perspective studies the emergence of complex and hierarchical human societies

over very long periods of time, comparing small-scale regional world-systems in

which all the humans are nomadic hunter-gatherers with the global networks and

complex institutions of the contemporary system (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014). Social change has always importantly involved

social movements. [1] New cults emerged to redefine ontology and

the moral order, to construct new forms of authority or to contest or resist

authority.

Norman Cohn (1970; 1993) contends that

millenarianism and eschatology emerged first with Zoroaster and then diffused

through Judaism to Christianity. But studies of cargo cults and revitalization

movements such as the ghost dance DuBois (2007) suggest that apocalyptic

beliefs may have already existed in at least some small-scale societies as part

of their repertoires of contention.

Chiliastic stories about the old world coming to an end and the new

world beginning are powerful motivators of risky behavior of the kind that

makes social movements go, both in the past and in the present.

Social movements are

hard to study because, even more than other social phenomena, they are

complicated and messy. Todd Gitlin (2012:141) puts it

this way in his 2012 study of the Occupy Wall Street movement:

Movements are

social organisms, living phenomena that breathe in and adapt to their

environments, not objects frozen into their categories while taxonomists poke

and prod them. They come, go, mutate, expand, contract, rest, split, stagnate,

ally, cast off outworn tissue, decay, regenerate, go round in circles, are

always accused of being co-opted and selling out, and are often declared dead.

In

this paper we will focus on transnational social movements in the context of

global civil society in order to investigate the potential for a network of radical social

movements to come together to play an important role in world politics in

the next few decades. We know that important institutional changes in the

modern world-system have been spurred by social movements in the past. The New Deal was given a powerful shove by

the labor movement, including socialists, communists and anarchists, in the

1930s. The problem addressed here is how

a powerful coalition of antisystemic movements[2]

might once again become an important force in the context of the crises that are

emergent in the 21st century.

The

world-systems perspective sees the evolution of global governance and the

capitalist world-economy as importantly driven by a sequence of world

revolutions in which local rebellions that were clustered together in time

posed powerful threats to the rule of the “great powers” and predominant global

elites (Wallerstein 2004). Successful contenders among those global

elites who wanted to maintain their privileges and power, or those that sought

such heights, had to figure out how to organize a

modicum of world order in the context of often-powerful rebellions from below.

The Protestant Reformation was such a world revolution in the 16th

century and it played an important part in the rise of Dutch hegemony. The world revolution of 1789 included the

French Revolution, but also the successful independence struggles in the United

States and Haiti, and then in most of the colonies in Latin America. The world revolution of 1848 broke out mostly

in the capitals of Europe to challenge monarchies and to assert the

self-determination of nations, but it had echoes in the new Christian sects

that emerged within the United States and even as far as the Taiping Rebellion

in China. The world revolution of 1917 included the Russian revolution, but

also the Mexican and Chinese revolutions, the Arab uprising of 1916, and gave

impetus to the great wave of decolonization struggles in Asia and Africa that

climaxed after World War II. In the world revolution of 1968 students mobilized

in the U.S., Mexico, France, Italy and China to protest both the Old Left and

the middle class values of the welfare state and consumerism (Gitlin 1993; Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2014).

In 1989 important

movements in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and China challenged Communist

regimes in the name of democracy. And, starting in 1994 with the Zapatista

revolt in Southern Mexico, another world revolution has emerged to contest

global justice, continued warfare, autocratic rule, and corporate capitalist

austerity policies. This last may end up with the moniker of “2011” when the

Arab Spring swept through the Middle East and on to Spain, Greece and the

Occupy Wall Street Movement (Gitlin 2012; Mason

2013). [3]

The focus of this

paper is on the New Global Left, which is a component of the larger global

civil society of actors who are consciously participating in world politics.

Some players within the New Global Left are trying to change the nature of

world society as a whole, while others are simply trying to defend themselves

against larger forces. And a significant group is trying to create local

communities that are constructed to redress some of the problems that global

capitalism has created. The New Global

Left is just the latest incarnation of a global left that has been engaging in

world politics for centuries.

Each world revolution reflects the nature of

contemporary contradictions, the ideological heritages of earlier world

revolutions, and the institutional structures that are predominant during its

historical period. World revolutions are

complicated because local and national struggles have different and often

unique characteristics due to the different histories of each local community

and national society, and because people in different zones of the larger system,

e.g. in the Global North and the Global South, often have different interests

and experiences. Nevertheless, each

world revolution takes on a particular character of its own that is due to the

nature of the constellation of movements that make it up, and the nature of

contending movements and the actions and ideologies of the authorities that are

challenged. And the nature of each global left is a moving target that must be

reassessed as the world revolution proceeds.

Contemporary “global

civil society” is composed of all the individuals and groups who knowingly

orient their political participation toward issues that transcend local and

national boundaries and who try to link up with those outside of their own home

countries in order to have an impact on local, national and global issues (Stäbler 2014).[4]

The New Global Left is that subgroup of global civil society that is critical

of neoliberal and capitalist globalization, corporate capitalism and the

exploitative and undemocratic structures of global governance (Santos 2006;

Steger et al 2013). The larger global

civil society also includes defenders of global capitalism and of the existing

institutions of global governance as well as other challengers of the current

global order. The New Global Left is the

current incarnation of a constellation of popular forces, social movements,

global political parties and progressive national regimes that have contested

with the great powers and global elites for centuries. The existing

institutions of global governance have been shaped by the efforts of competing

elites to increase their powers and to defend their privileges, but also by the

efforts of popular forces and progressive states to challenge the hierarchical

institutions, defend workers’ rights, access to the commons, the rights of

women and minorities, the sovereignty of indigenous peoples and to democratize

the local, national and global institutions of governance (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014).

Our notion of the

New Global Left includes both civil society entities: individuals, social

movement organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), but also

political parties, party-networks and progressive national regimes. In this

paper we will discuss the relationships among the movements and the progressive

populist regimes that have emerged in Latin America in the last two decades.

These regimes are an important part of the New Global Left, though it is

well-known that the relationships among the movements and the regimes are both

supportive and contentious (Chase-Dunn, Morosin and

Alvarez 2014; Herrera 2014).[5]

The boundaries of

the progressive forces that have come together in the New Global Left are fuzzy

and the process of inclusion and exclusion is ongoing. The rules of inclusion

and exclusion that are contained in the Charter of the World Social Forum,

though still debated, have not changed much since their formulation in 2001.[6]

The New Global Left

has emerged as resistance to, and a critique of, global capitalism. It is a

coalition of social movements that includes:

·

old social movements that emerged in the 19th

century (labor, anarchism, socialism, communism, feminism, environmentalism,

peace, human rights) along with

·

more recent incarnations of these and movements

that emerged in the world revolutions of 1968 and 1989 (queer rights,

anti-corporate, fair trade, indigenous as well as

·

even more recent ones such as the climate justice movement, slow food-food

rights, global justice-alterglobalization,

anti-globalization, health-HIV and alternative media.

The explicit focus on the Global South and global justice is somewhat

similar to some earlier incarnations of the Global Left, especially the

COMINTERN, the Bandung Conference and the anti-colonial movements. The New

Global Left contains remnants and reconfigured elements of earlier Global

Lefts, but it is a qualitatively different constellation of forces because:

o there are

new elements,

o the old

movements have been reshaped, and

o a new

technology (the Internet) has been used to try to resolve North/South issues

within movements and contradictions among movements.

There has also been a learning process in which the earlier successes

and failures of the Global Left are being taken into account in order to not

repeat the mistakes of the past. The relations within the family of antisystemic movements and among the populist regimes are

both cooperative and competitive. This needs to be brought out into the open in

order that the cooperative efforts may be enhanced so that global collective

action for restructuring the world-system may be more effective.

Collective Action and Coalition

Theories

Many theoretical

approaches in social science are relevant for understanding the process of

coalition formation. Exchange theory predicts that parties that benefit one

another should be more likely to engage in cooperative behavior. Balance theory

predicts that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Balance of power theory

predicts that coalitions in a triad of competing players are most likely to form

among the weaker players in opposition to the strongest player. All these theories presume a level of unified

rational action that is unlikely to be present when the subjects of analysis

are social movements. But they are nevertheless suggestive.

A good summary of

the main elements involved in coalition formation among social movements is

that by Sidney Tarrow (2005). Regarding coalitions within and between

social movements, Tarrow contends that the most

common purposes of these are to combat a common threat or to take advantage of

an opportunity; hence, the often-temporary nature of coalitions. The common

threat or existence of opportunity is what gives rise to the coalition and

allows it to exist (see also Van Dyke 2003; Van Dyke and McCammon

2010). According to Tarrow four elements are

necessary to maintain a coalition:

1.

Members must frame the issue that brings them

together with a common interest.

2.

Members’ trust in each other and believe that

their peers have a credible commitment

to the common issue(s) and/or goal(s).

3.

The coalition must have a mechanism(s) to manage

differences in language,

orientation,

tactics, culture, ideology, etc. between and among the collective's

members

(especially in transnational coalitions).

4.

The shared incentive to participate and,

consequently, benefit.

Cooperative action and coalitions vary in

intensity and longevity. At one extreme are mergers that involve covenants in

which the former parties lose their separate identities and create a new

integrated and structured organization. At the other extreme are temporary

alliances for specific limited purposes in which the parties maintain their

separate identities and organizations.

Zald and

McCarthy (1987) use organizational analysis, especially based on the necessity

for social movement organizations to obtain resources, to consider the factors

that are involved in conflict and cooperation among social movements. They make

an important distinction between inclusive and exclusive social movement

organizations and discuss how this affects competition and cooperation. Social

movement industries are defined as congeries of social movement organizations

that pursue the same or similar goals (Zald and

McCarthy 1987:161). They also distinguish between sympathizers and constituents

and between beneficiaries and altruistic benefactors. And they consider the

situational and organizational factors that affect cooperation and

competition among social movement organizations.

Transnational social movements have big

challenges that more local movements have to a much lesser extent. There is a global culture in formation (Meyer

2009; Chase-Dunn 1998), but many big cultural differences between nations,

classes, and ethnic groups remain. People in different parts of the

world-system have different problems and different interests. Thus all

transnational movements have huge problems of communication and value

differences, differences in modes of political expression, differences in the

relative importance of issues, and differences in the availability of

resources. All these factors undermine identification and trust. These

differences exist within each social movement industry (Zald

and McCarthy 1987), and between social movement industries. Nevertheless

transnational social movements emerged in earlier centuries when these problems

were even more daunting and yet they managed to form powerful coalitions that

were significant players in world politics. The current availability of less

costly technologies of communications and transportation has proven to be a

great opportunity for organizing movements internationally.

Ruth Reitan (2007) addresses the issue of types of solidarity among global activists.

Conscience

constituents are direct supporters of a social movement organization who do not

stand to benefit directly from the accomplishment of that organization’s goals

(McCarthy and Zald

1977). According to Reitan two forms

of solidarity emerge among those distant from the immediate consequences that

are the focus of the movement: altruistic solidarity and reciprocal

solidarity. Altruistic solidarity occurs

when “sympathy with the suffering of

others who are deemed worthy of one’s support seems to be the prevailing

affective response among those who choose to act” (Reitan

2007:51). Altruistic solidarity is characterized by low risk

activism that may be largely apolitical, suppress contentious action, and even

reproduce inequality. In her research on emergency food providers, Poppendieck

(1999:231) argues that charitable altruism is “a gift, offered with

condescension and accepted in desperation, that is necessitated by incapacity

and failure” and maintains social distance between the giver and receiver.

Further, Poppendieck

(1999:9) identifies the “‘moral safety valve’ function of

charitable programs [in] relieving the discomfort of the privileged and thus

the pressure for more fundamental action.”

On the other hand, “reciprocal

solidarity” emerges when “a perceived connection between one’s own problems or

struggle and that of others tends to lead to empathy with another’s suffering

and a sense that its source is at least remotely

threatening to oneself” (Reitan 2007:51). Reciprocal solidarity is characterized by pluralism and

mutual cooperation between conscience constituents and beneficiary constituents

in pursuit of structural change. Conscience constituents engaged in reciprocal

solidarity may attempt to unpack privilege in order to understand their position(s)

in larger systems of power that tend to recreate themselves in social movements

(Eichstedt 2001; McIntosh 2007; Paulsen and Glumm 1995). These stark distinctions, however, are largely

analytical, as “movements today are comprised of identity, reciprocal, and

altruistic solidarities alike, in different mixes towards different outcomes” (Reitan 2007:56).

Reitan

recognizes the importance and validity of both altruistic and reciprocal

solidarity, but also considers their limitations. She tells the story of

Jubilee 2000, a coalition of churches in the Global North who began a campaign

of debt relief for countries in the Global South who had become hugely indebted

to banks in the Global North in the last decades of the 20th

century. Jubilee 2000 was based mainly

on altruistic solidarity with somewhat weak participation from the Global

South. But, when the campaign succeeded in bringing banks to the table for

negotiations about debt relief, the leadership of Jubilee 2000 made compromises

that were seen as betrayal by the activists from the Global South, who then

formed their own organization, Jubilee South.

This story is meant to show the limitations of altruistic solidarity and

the necessity for activists from the Global South to have their own autonomous

organizations. A related issue is the

sometimes contentious relationship between NGOs (organizations with budgets and

paid staff) and social movement organizations that rely on mass memberships and

volunteer (unpaid) leadership.

Reitan (2007) tells the story of

Via Campesina, a global union of small farmers, that rejected participation by NGOs after these

were seen as attempting to steer the organization. Via Campesina

opted to restrict membership to farmers only, even excluding friendly

participant-observing sociologists as well as NGOs.

Related to the

discussion of altruistic solidarity is the discourse about cosmopolitan

identity. Yanacopolous and Smith discuss this as

follows:

“As

organizations increasingly working across national borders and addressing

transnational issues – such as development – NGOs could be seen as the

expression of a key cosmopolitan norm. In seeking to communicate global ideas

and persuade individuals to respond to the welfare of the 'distant other',

development NGOs could be seen as promoting a post-national cosmopolitan agenda

which challenges difference and which seeks to change dominant attitudes and

dispositions. Underlying these connections is a contestable notion of NGOs as

values-based organizations seeking 'alternatives' which better address poverty

and injustice” (Yanacopolous and Smith 2008: 301)…. “...despite the

apparent resonance between NGOs and cosmopolitan norms, NGOs'

cosmopolitanism is currently somewhat ambivalent.” (ibid: 303).

And,

Perhaps

more significant is the critique of the ways NGOs - and the development

industry more generally - has proclaimed universal values that are in effect

firmly rooted in the particular Western liberal traditions and histories from

which NGOs have emerged. This, then, reproduces Van der Veer's (2002) notion of

a colonial cosmopolitanism in which the desire to empathize and understand the

'other' is part of a system of controlling and managing the 'other'. A second

problem with this proclamation of universal values allied to an engagement with

the distant 'other' has been the way it has largely been realized in terms of

charity towards the 'other' as opposed to justice (Yanacopulos, 2007) (Yanacopulos and Smith

2008:307).

There has been a lively debate within the cosmopolitan

tradition concerning the relative merits of charity vis-a-vis justice-based approaches. Obviously, one of the problems with NGOs and their adoption

of global civil society since the 1980s is that it fits nicely into the

neoliberal New Policy Agenda (McIllwaine 2007; Eschle and Stammers 2004). In the US context,

the nonprofit industrial complex (the domestic version of NGOs) has been

criticized for depoliticizing potential activists by turning them into passive

service recipients. On the other hand, service provisioning can also

be understood to “improve the daily lives of constituents, as well as to build

solidarity, political analysis, self-determination, and loyalty” and therefore

complimentary or constitutive of activism (Luft 2009).

More

recently Reitan (2012a:324) has discussed the 'frayed

braid' composed of the three strands of the historic global left (liberalism,

marxism, and anarcho-autonomism), pointing out

that in the current setting, these strands have not broken apart as they did in

previous world revolutions. Reitan contends that the

different strands of the braid have learned from the past. She also says ,

there is “a desire for building intermovement

solidarity and broader alliances while retaining intra-movement identity and

autonomy.” (Reitan 2012a, 324).

And further

… activists are reflecting on and debating together,

hybridizing, experimenting with and challenging the limits of these traditions

in unique ways. Groups and individuals inspired by each tendency hone their

tactics, refine positions, and strengthen identities, while simultaneously

seeking alliances, coordinating actions, and articulating nascent strategies

with a wide range of others. Throughout this mobilization cycle they have

sought to dialogue, build trust, craft consensus declarations, and act in

coalitions when possible or in parallel affinity blocs when not. While

tensions are ever present, activists make ongoing efforts to mitigate, manage,

bridge, or downplay them toward joint action—or at the very least to not work

at cross-purposes.” (Reitan 2012a, 325)

Reitan (2012b) also

addresses the issues involved in the upscaling of transnational social

movements – moving from the local to the transnational level of

organizing. She says

rather than simply an exodus—i.e.

‘spillover’ or ‘spillout’—from one movement to

another, or a distinct transnational movement arising spontaneously, key

bridge-building organizations have proven crucial in shifting down to harness

nascent activist energies by brokering new ties and reinvigorating old ones as

well as frame extending between emerging and extant concerns, in order to scale

back up as a broader transnational movement for Global Peace and Justice (Reitan 2012b, 337).

Reitan

writes that:

the

process of transnational coalescence entails bridge-builders...who, when

faced with a new bellwether or trigger issue, temporarily scale down (i.e.

internalize, or loop back) to the local, national, or macroregional

levels, but with the aim to scale up again to the transnational level of

contention as a broader movement. To do so, they use various framing tactics

while brokering new ties and diffusing information among existing and new

activists, particularly frame extension, in order to foster transnational

coalescence...between ‘new’ and ‘old’ issues and movements (Reitan

2012b, 338).

Reitan also

discusses the “rooted cosmopolitans” named by Sidney Tarrow

(2005:42). These are activists “whose

relations place them beyond their local or national settings without detaching

them from locality.” “Thus, rather than being rootless cosmopolitans these

bridge-builders are among the most committed and seasoned activists, with

expertise, leadership experience and ready access to domestic-level material

and symbolic resources” (Reitan 2012b:339). These are the activists featured in Keck and Sikkink’s (1998) analysis of “transnational advocacy

networks” and they pinpoint one of the motives for upscaling (going

transnational). This is the so-called “boomerang effect” in which social

movement activists use their ties abroad to bring pressure on reticent local or

national authorities.

This discussion also reminds us of Wallerstein’s (2004) mention of the importance of

‘synergists” who participate in, and link, different social movements with one

another, as well as the study of such bridgers by

Carroll and Ratner (1996).

Justice Globalism as an Ideological

Constellation

Manfred Steger, James Goodman and Erin K. Wilson

(2013) present the results of a systematic study of the political ideas

employed by forty-five NGOs and social movement organizations associated with

the International Council of the World Social Forum. Using a modified form of

morphological discourse analysis developed by Michael Freeden

(2003) for studying political ideologies, Steger, Goodman and Wilson analyzed

texts (web sites, press releases and declarations) and conducted interviews to

examine the key concepts, secondary concepts and overall coherence of the

political ideas expressed by these organizations as proponents of “justice

globalism.” Steger et al see three main contending ideological constellations for the

contemporary “global imaginary”: market globalism (what others have called

neoliberalism), political Islam and justice globalism. Their study is mainly about the conceptual

and policy content of justice globalism but, since several of the key concepts

are also used by market globalists, (democracy, justice, human rights,

development) the ways in which the uses of these terms are distinguished from

their meanings in the neoliberal discourse are an important part of the efforts

made by justice globalists to clarify their approach. Steger et al also utilize Freeden’s

(2003) notion of “decontestation” whereby central

concepts are reinforced by metaphors and narratives that establish greater

consensus about their meanings.

The key concepts of justice

globalism extracted by Steger et al

(2013: Table 2.1 pp. 28-29) are:

·

participatory

democracy,

·

transformative

change,

·

equality of access

to resources and opportunities,

·

social justice,

·

universal rights,

·

global solidarity and

·

sustainability.

The meanings of

each of these concepts have emerged in an on-going dialectical struggle with

market globalism. Steger et al

discuss each of these and evaluate how much consensus exists across the

forty-five movement organizations studied. They claim that there is a

relatively impressive degree of consensus, but their results also reveal

on-going contestation. For example, though most of the organizations seem to

favor one or another form of participatory democracy, there is also awareness

of some of limitations of participatory democracy, and different attitudes

toward participation in representative democracy.

The important

notion of “horizontality” is not examined in detail, but it is well-known that

networks of equal and leaderless individuals are preferred to formal or

informal hierarchy within movements.

Some of the

organizations studied by Steger et al

eschew participation in established electoral processes, while others do not.

Steger et al highlight the importance of “multiplicity” as an approach that values diversity

rather than trying to find “one size fits all” solutions. They note that the Charter of the World

Social Forum values inclusivity and the welcoming of marginalized groups. But Steger et al do not give much attention to the issue of prefiguration

--“building the new society inside the shell of the old,” though this stance

has found wide support from many important global justice social movement

organizations. The Zapatistas, the

Occupy anarchists, and many in the environmental movement are engaged in

efforts to construct the sustainable alternative world that they want to see

rather than trying to change the whole system. Also not much attention is given

to the notion of community rights in the human rights discourse, nor to the idea that nature (“mother earth” has rights as proposed

by the World People's Conference on

Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth held in Cochabamba, Bolivia in 2010.

The discussion of global solidarity emphasizes the centrality of what Ruth Reitan (2007) has called “altruistic solidarity” – the

identification with poor and marginalized peoples – without much consideration

of solidarity based on common circumstances or identities. Steger et

al do, however, mention the important efforts to link groups that are

operating at both local and global levels of contention.

Steger et al also designate five central

ideological claims that find great consensus among the global justice

activists:

- Neoliberalism

produces global crisis,

- Market-driven

globalization has increased worldwide disparities in wealth and well-being,

- Democratic

participation is essential for solving global problems,

- Another

world is possible and urgently needed, and

- People

power not corporate power.

These assertions shape the policy alternatives

proposed by global justice activists. The Steger et al study is a useful paragon of how to do research on political

ideology and it provides important insights into what we have called the New

Global Left.

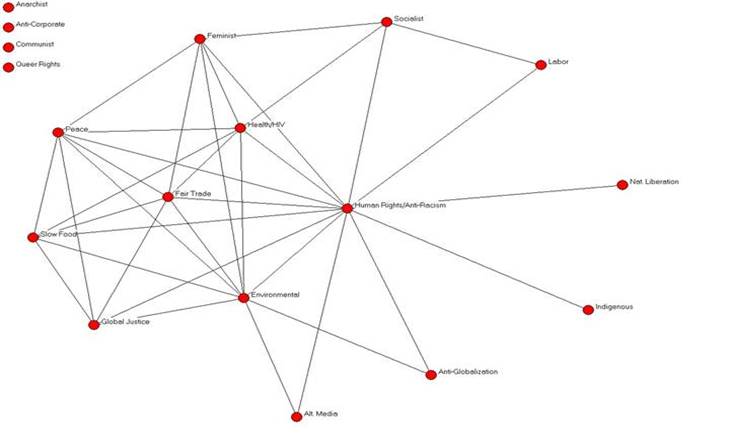

The Social Forum Surveys

Our research on the World Social Forum has produced maps

of the network of movements that are involved in the social forum process (see

Figure 1). This is probably a fair

representation of the structure of the left wing portion of global civil

society. The University of

California-Riverside Transnational Social Movement Research Working Group has

conducted four paper surveys of attendees at Social Forum events. [7]

We used previous studies of the global justice

movement by Amory Starr (2000) and by William Fisher and Thomas Ponniah (2003) to construct our original list of eighteen

social movement themes that we believed would be represented at the January

2005 World Social Forum (WSF) in Porto Alegre,

Brazil. We also conducted a survey at the WSF in Nairobi, Kenya in 2007 in

which we used most of these same movement themes, but we separated human rights

from anti-racism and we added eight additional movement themes (development,

landless, immigrant, religious, housing, jobless, open source, and autonomous).

We used this same larger list of 27 movement themes at the US Social Forum (USSF)

in Atlanta in 2007 and in Detroit at the USSF in 2010.

We studied changes and continuities in the relative sizes of movements and changes in the network centrality (multiplicative coreness) of movements. Relative movement size is indicated by the percentage of surveyed attendees who claimed to be actively involved in each movement theme. We asked each attendee to check whether or not they identified with, or were actively involved in each of the movement themes[8] with following item on our survey questionnaire:

(Check all of the following movements with which you (a) strongly identify with and/or (b) are actively involved in:

(a) strongly

identify:

(b) are actively involved in:

1. oAlternative

media/culture

oAlternative media/culture

2. oAnarchist

oAnarchist

3. oAnti-corporate

oAnti-corporate

4. oAnti-globalization oAntiglobalization

5. oAntiracism

oAntiracism

6. oAlternative Globalization/Global Justice

oAlternative Globalization/Global Justice

7. oAutonomous

oAutonomous

8. oCommunist

oCommunist

9. oDevelopment aid/Economic development oDevelopment aid/Economic development

10.oEnvironmental

oEnvironmental

11.oFair Trade/Trade

Justice

oFair Trade/Trade Justice

12.oFood Rights/Slow

Food

oFood Rights/Slow Food

13.oGay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender/Queer Rights oGay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender/Queer Rights

14.oHealth/HIV

oHealth/HIV

15.oHousing

rights/anti-eviction/squatters

oHousing

rights/anti-eviction/squatters

16.oHuman

Rights

oHuman Rights

17.oIndigenous

oIndigenous

18.oJobless workers/welfare

rights

oJobless workers/welfare

rights

19.oLabor

oLabor

20.oMigrant/immigrant

rights

oMigrant/immigrant rights

21.oNational Sovereignty/National

Liberation oNational Sovereignty/National Liberation

22.oOpen-Source/Intellectual Property

Rights oOpen-Source/Intellectual Property Rights

23.oPeace/Anti-war

oPeace/Anti-war

24.oPeasant/Farmers/Landless/Land-reform

oPeasant/Farmers/Landless/Land-reform

25.oReligious/Spiritual

oReligious/Spiritual

26.oSocialist

oSocialist

27.oWomen's/Feminist

oWomen's/Feminist

28.oOther(s), Please list

___________________ oOther(s), Please list _________________

Figure 1:

The Network of Movement Linkages at the 2007 World Social Forum in Nairobi

The UCINet QAP

routine produces a Pearson’s r correlation coefficient that shows the degree of

similarity between two dichotomized affiliation network matrices. The Pearson’s

r coefficient varies from -1 (a perfectly negative linear relationship between

two variables) and +1, a perfectly positive linear relationship. The Pearson’s r correlation coefficient

between the USSF 2007 and the USSF 2010 movement affiliation matrices was

0.74. This is a rather strong positive

correlation and is slightly larger than was found between the World Social

Forum meeting in Nairobi and the U.S. Social Forum meeting in Atlanta, which

was 0.71 (Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro 2009). It is unsurprising that the Atlanta

USSF network would be more similar to the Detroit USSF than it would be to the

Nairobi WSF, but the surprise is that the national and global affiliation matrices are

so similar. This implies that there is a fairly similar structure of network

connections among movements that is global in scope and that the global level

network is rather close to the network produced when activists from grassroots

movements within the U.S. come together. This is the movement of movements

within which we hope to help construct a more effective instrument. [9]

Fronts

The history of broad-based left wing movement

coalitions in earlier periods is relevant for understanding articulation

processes in the contemporary world revolution.

The 3rd International (COMINTERN) was a complex of red

networks assembled to coordinate the political actions of communists in the

years after World War I. It was in this context that a transnational group of

communist intellectuals claimed to lead the global proletariat in a world

revolution that was intended to transform capitalism into socialism and

communism by abolishing large-scale private property in the means of production

(Hobsbawm 1994).

The COMINTERN adopted its own statutes at its

second congress in 1920. It was led by an Executive Committee and a Presidium.

The statutes stated that congresses with representatives from all over the

world were to meet “not less than once a year.” The COMINTERN also organized

and sponsored a number of other “front organizations” – the Red International

of Labor Unions, the Communist Youth International, International Red Aid, the

International Peasants’ Council, the Workers’ International Relief and the

Communist Women’s Organization (Sworakowski 1965;

COMINTERN Electronic Archive).

The COMINTERN was founded in the Soviet Union,

the “fatherland of the proletariat,” and so it is often depicted as having been

mainly a tool of Soviet foreign policy. There is little doubt that this became

true after the rise of Stalin. In perhaps the most blatant example, Stalin

tried to use the COMINTERN to get Communist Parties all over the world to

support the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939. But during Lenin’s

time the COMINTERN held large multinational congresses attended by people with

at least forty languages as their native tongues. The largest of these

congresses had as many as 1600 delegates attending. Sworakowski

(1965:9) says,

After some attempts at restrictions in the

beginning, delegates were permitted to use at the meetings any language they

chose. Their speeches were translated into Russian, German, French and English,

or digests in these languages were read to the congresses immediately following

the speech in another language. Whether a speech was translated verbatim or

digested to longer or shorter versions depended upon the importance of the

speaker. Only by realizing these time-consuming translation

and digesting procedures does it become understandable why some congresses

lasted as long as forty-five days.[10]

The COMINTERN was

abolished in 1943, though the Soviet Union continued to pose as the protagonist

of the world working class until its demise in 1989. Paul Mason (2013) reminds us of the

importance of threats from other social movements that pose challenges that drive

former sectarians to try to be more inclusive.

The United Front originated as an effort by Communists to create an

alliance with other socialists, peasants and all workers. The Popular Front was an even broader

coalition that included all those who were willing to oppose fascism, including

capitalists and their parties. These

efforts have usually been seen as manipulative moves by communists to

infiltrate and control other movement organizations, but David Blaazer’s (1992) study of Popular Front leaders in Britain

shows that many of the non-communist participants were not ignorant dupes of

the communists. They were committed democrats and socialists who were willing

to work with communists in order to mobilize the fight against fascism (see

also the essays in Graham and Preston, 1987).

The anti-anticommunism of the New left in the world revolution of 1968

was another example of an inclusive social movement that was willing to

overlook a bad history in order to combine forces with former competitors (Gitlin 1993). So the

unfrayed braid observed by Reitan

had earlier incarnations.

But the general point made by Mason stands. The

forces of divergence in the global left of the 1930s were partly overcome by

the clear and present danger of the rise of a great wave of fascism (Goldfrank 1978). Of course in the midst of all this

cooperation the Trotskyists proclaimed a Fourth International in 1938 (James

1997). And after the demise of fascism

that resulted from the outcome of World War II, the left fragmented again in

most countries. Maoists in China managed

to put together a coalition strong enough to beat the Nationalists and to

govern the new Peoples Republic. But in

other countries this produced a new fissure between the Maoists and other

elements of the left.

Does this history of

fronts have implications for the present and the near future? Might there be a

21st century functional equivalent of fascism that could drive

elements of the New Global Left closer together, or serve as a driving force

for the organization of new capable instruments of global political

activity? Here we should distinguish

between what social movement scholars call counter-movements[11]

versus other contending movements

that have goals that are very different from the New Global Left but are not

responses to it. Counter-movements are movements that emerge to counter-act and

oppose the efforts of other movements (Snow and Soule (2010:82) William I. Robinson

(2013) contends that recent developments in response to the growth of

resistance from below and the disarray caused by the various contemporary

crises of global corporate capitalism constitute the rise of “21st

century fascism” in the guise of a globally coordinated police state. Others

have spoken of “surveillance capitalism” and the “national security state.”

Such a development could become such a large threat that the divergent elements

in the New Global Left might be forced to forge a strong and organized

response. Some of the horizontalists and prefigurers would need to compromise their principles in

order to put together more pragmatic and better organized instruments with

which to counter 21st century fascism.

Regarding contending movements from below, the obvious candidate mentioned by Steger, et al is political Islam. Interestingly, there has been little discourse within the New Global Left regarding political Islam. Cosmopolitans want to uphold the freedom of religion and to protest racist attacks on innocent Moslems. The New Global Left has, at least so far, been willing to let the neoliberals carry the ball regarding gender discrimination, female genital mutilation, and other issues. But the events in Egypt and the other Middle Eastern Arab Spring situations make it obvious that the issues involved must eventually be confronted. Inclusive diversity and multiplicity must eventually reach their limits. That said, it is unlikely that political Islam will play a role analogous to that of 20th century fascism in provoking a stronger alliance of movements of the New Global Left.

States and

Social Movements

Our concern for

capacity (and muscle) in world politics suggests the importance of a discussion

of the contentious current relationship between antisystemic

social movements and reformist and antisystemic

regimes such as those that have been elected in many Latin American countries. We

agree with Patrick Bond (2013) that many of the semiperipheral

state challengers to the hegemony and policies of the United States (the

so-called BRICS)[12]

seem mainly to be trying to move up the food chain within the capitalist

world-system rather than trying to produce a more democratic and sustainable

world society. Revolutions are needed within these polities to produce regimes

that will be effective agents of transformative social change. This said, transnational social movements should be prepared to work

with progressive regimes that emerge in order to try to change the rules of the

global economic order (Evans 2009; 2010).

It is well-known that many transnational

movement organizations scorn politics-as-usual and resist efforts by

progressive regimes to provide resources and leadership to movements. Autonomism makes this a basic principle and the World

Social Forum Charter proscribes individuals from attending as representatives

of governments. This is part of the

anti-elitism of the culture of grass roots movements. President Lula of Brazil and President Chavez

of Venezuela had to give their speeches at a venue near to, but not part of,

the World Social Forum meetings in Brazil.[13] When nineteen prominent

leftist academics tried to issue a declaration in the name of the World Social

Forum at end of the meeting in Porto Alegre in 2005 they were widely

denounced as elitists. This is related

to the horizontalist stance that has been strong in

the Social Forum process since its emergence. The activists want leaders to

“bubble up from below.” The Zapatistas of Chiapas take this position. Similar

elements were widespread in the student movements of the 1960s (Gitlin 1993). Facilitators were preferred over

grandstanders. The New Left critique of the Old Left was heavily based on a

rejection of the goal of taking state power, which tended to become an end in

itself and to corrupt the transformative projects of movements. This shows an

awareness of what Robert Michels termed “the

oligarchical tendencies of political parties.”

The “leaderless”

discourse of the Occupy Movement was another incarnation of horizontalism.

Horizontalism is constituted by a strong commitment

to the value of each unique individual, and the equality of individuals, and to

the empowerment of marginalized groups. In this sense it is redolent of the

global moral order described and analyzed by John W. Meyer (2009). Radical individualism has been an important

feature of millenarian religious and political movements since medieval times

(Cohn 1970).

A comparative

world historical perspective on state/movement relations would stress the importance

of the effects that earlier world revolutions had because of the emergence of

regimes in the semiperiphery that explicitly

challenged and the existing world order and the global rule of capital.[14]

The rise of the Bolshevik Regime in Russia, as well as strong labor movements

within the core states, spurred the New Deal and social

democracy to save capitalism by reforming it. In the world-systems perspective

states are organizations that claim sovereignty but that are

actually interdependent parts of a larger polity – the interstate system. A

movement that attains state power in a modern national state has not conquered

the whole system. It has taken over an institution that is part of a larger

system.

This explains

much about the policies of the so-called communist states that came to power in

the 20th century. They engaged in semiperipheral

protectionism in order to industrialize and they invested huge resources on

military capability in order to prevent conquest by capitalist core

states. It is entirely understandable

why social movements should seek to maintain their autonomy from states, but

the ideology of non-participation in “politics-as-usual” could benefit by

recognition of the functionality of coordination between radical and reformist

social movement organizations. Radical

movements that threaten to transform the whole social order increase the

likelihood that enlightened conservatives will make deals with less radical and

more legitimate social movement organizations and NGOs.[15] This is how it has worked in the past and how

it is likely to work in the future.

Awareness of this dynamic should be useful to social movement

organizations, promoting greater tolerance and collaboration between radicals

and reformists.

The Global Class

Structure

Analysts

of an alleged global stage of capitalism contend that a transnational

capitalist class has recently emerged and that global capitalism is also

producing a newly transnationalized working class (e.g.

Sklair 2001; Robinson 2006). This analysis has the

implication that class struggle should now be occurring at the global level.

World-systems analysts have been studying the system-wide configuration of

classes over the past several hundred years (Wallerstein

1974; Amin 1980) but whether or not recent changes are seen in long-run

perspective, there have obviously been important recent changes and these have

implications for analyzing potential movement that might emerge in response to

recent crises. The analysts of global capitalism have talked about “the peripheralization of the core” as a way of describing the

attack on core workers and unions that has been carried out by neoliberals. The

casualization of labor and the growth of the informal sector has been an

important phenomenon in both core and non-core countries since the rise of Reaganism-Thatcherism.

Beverly Silver’s (2003) study of waves of labor unrest shows that the

export of the industrial proletariat from the core to the semiperiphery

produced militant labor movements in the new regions of industrial manufacturing

in the semiperiphery.

Savan Savas Karataşlı, Sefika Kumral,

Ben Scully and Smriti Upadhyay ( 2014) study the recent wave of unrest that spread around the globe from 2008 to 2011,

building upon Silver’s (2003) studies of labor unrest using protest and labor unrest data coded from

major news sources. They provide a

useful review of efforts in the social science literature to analyze this

global cycle of protest. They note that most analyses underplay the significance

of the role of wage-earners in these protests. They use their coded protest

data to examine the extent to which this recent wave of protests indicates a

recurrence of past forms of unrest or whether the current period represents a

different pattern.

Silver (2003) divides labor protest

into two categories: Marx-type and Polanyi-type. Marx-type unrest refers to

offensive struggles of new working classes in formation, whereas Polanyi-type

unrest refers to the defensive protests of workers whose previous gains are

being undermined as well as resistance against proletarianization

(Karatasli et al 2014).

The authors

find that, along with a mix of Marx-type unrest[16] and Polanyi-type unrest[17], which are part of the

older cyclical process of capitalism making and unmaking livelihoods,[18] a third type of unrest,

driven by what Marx called stagnant relative surplus population[19],

also played a large part in the protests of 2011 and presents a “secular trend in which capitalism destroys more

livelihoods than it creates over time.” The growing number of this third type

of worker, composed largely of those who can work but are unable to be absorbed

by the productive capacity of the economy, and their presence in protests and

social movements that have continued in the aftermath of 2011, gives credence

to the idea that the problems faced in regions of unrest are chronic and

enduring. This growing excluded segment of the population is an important force

in these movements and the secular increase in this section of the working

class poses a critical challenge to the capitalist system.[20]

Karatasli et al

2014 criticize those who focus discussion of “the precariat”

(e.g. Standing 2011; see also Korotayev and Zinkina 2011)) of middle-class workers whose job conditions

and incomes have declined and on educated young people who cannot get a job

commensurate with their expectations and face large education-related debts (“graduates without a future”)[21] It would seem that both these and the less

educated young who cannot find employment could be understood as different parts

of the stagnant relative surplus population. Karatasli

et al (2014) strongly demonstrate

that workers have played a large role in the 2011 protest wave, and they

correctly note that this has often been overlooked by other analysts of these protests.

Contenders

for Articulation

Which

of the existing transnational social movements and movement coalitions that

have come out of the Social Forum process could plausibly emerge as central to

the formation of a more capacious coalition of the New Global Left that could strongly

challenge the global rule of capital in the 21st century? We agree

with Steger et al that a coherent

ideological framework already exists. And our survey findings support the

optimism from Ruth Reitan and Jackie Smith (Smith and

Wiest 2012) regarding the existence of already

functioning collaboration within the Social Forum process and elsewhere. But we

also see the need for stronger and more capable instruments to play a role in

world politics in the emerging period of crises. Where might such a force for articulation

come from?

Workers

(Again)

Could a

reconfigured movement based on workers rights and global unionism come out of

the global precariat that has been produced by

neoliberal capitalist attacks on labor unions and the welfare state? Peter

Waterman has proposed a Global Labor Charter that is intended to mobilize such

a coalition and Guy Standing (2014) proposes charter for the precariat.

Mike Davis (2006) has suggested that the

informal sector workers of the Global South might step forward as a historical

subject, and William I Robinson (2006) has theorized the emergence of a

transnational working class that has been created by the processes of global

capitalism. Austerity politics by neoliberals might provide the basis for such

a movement, and elements of an anti-austerity coalition seemed to be operating

in the European Summer and the Occupy Movements. Perhaps a reconfigured version

of the Old Left notion of the world working class as the midwife of a possible

other world might yet be able to articulate the anti-systemic movements. Social

movement unionism and experiments in cross-border organizing have had some

successes as well as notable failures. But in a deepening crisis these efforts

might yet pan out.

The precariat

also includes the unemployed educated seen by Mason as the main participants in

the recent waves of popular protest demonstrations that have emerged since the

Arab Spring. The educated unemployed (or underemployed) are also burdened with

large debts incurred when neoliberals shifted much of the cost of public higher

education on to students. In the context of growing levels of income and wealth

inequality within many core countries (Picketty 2014)

this would seem to prepare the ground for social movements in which radicalized

middle class elements might once again ally with the urban poor and workers, as

they did in the world revolution of 1848 (Mason 2013).

Feminists

Maria Mies

(1986) argued that women and the marginalized peasants and workers of the

Global South formed an exploited and potentially revolutionary subject that

could rise to challenge global capitalism. Ecofeminists

have emphasized the complementarities of a kinder gentler approach to nature

and the politics of women. Socialist feminists have noted the growing important

of female labor in all the world’s regions and the leadership shown by global

feminists in confronting and partially resolving North/South differences among

women (Moghadam 2005). Anarchists such as David Graeber

(2013) have noted that many of the processual

innovations that were utilized in the Occupy Movement came out of feminist

practices.[22] Feminists have links with many of the other

movements, as shown by the results of our research on the network of social

movement connections in Figure 1 above.

Climate Justice

Arguably the most imminent crisis

produced by contemporary global capitalism is the onrushing arrival of

anthropogenic climate change. The environmental movement has strong links with

some elements of the labor movement, with global indigenism,

and with feminism (mentioned above). Patrick Bond (2012) has written convincingly of the

emerging centrality of the climate justice movement. Climate justice emerged

from the environmental justice movement, which was a combination of

environmentalism and human rights and anti-racism. It has long been noted that the poor are the

first to suffer the effects of pollution and environmental degradation. Steger et al (2012) devoted an entire chapter

of their study of justice globalism policy implications to the “climate crisis”

and Ruth Reitan and Shannon Gibson (2012) studied

three climate activist networks that participated in the Copenhagen climate

summit in 2009, supporting the notion that climate justice has great potential

as a unifying framework for the New Global Left.

Of course there are other

possibilities for the role of articulator.

We have cited Reitan’s (2012b) consideration

of the peace movement. The emerging context of crises will be an important set

of forces that will favor some frames over others. The order, speed of onset,

and interaction of different kinds of crises will also favor either a more

reformist global Keynsianism versus a more radical restructuring of political and

economic institutions.

Conclusions

As

a famous East Asian revolutionary said, ‘the situation is excellent.”

Capitalism is in crisis again and the forces of progress are moving to try to

create a more humane, democratic and sustainable world society. A coherent social science perspective exists with

which to analyze the structures and institutions of the system (the comparative

evolutionary world-systems

perspective) and a coherent political ideology, justice globalism, has come out

of the Social Forum process. What is needed now is organization. Climate

justice, feminism or a new version of the workers’ movement could be frameworks

for uniting those who want to build a new society within the skeleton of the

old with those who want to reorganize the whole system. That would be a serious

instrument.

Bibliography

Amin,

Samir 1980 “The class structure of the contemporary imperialist system.” Monthly

Review 31,8:9-26.

__________2008.

“Towards the fifth international?”

Pp. 123-143 in Katarina Sehm-

Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Global Political Parties.

London: Zed Press.

Anderson, Perry 2005 Spectrum.

London: Verso

Anheier,

Helmut and Hagai Katz 2003 “Mapping Global Civil

Society” pp. 241-258 in Mary

Kaldor, Helmut Anheier and Marlies Glasius (eds.) Global

Civil Society 2003. New

York:

Oxford University Press.

Bandy, Joe and Jackie Smith 2005 Coalitions Across Borders: Transnational

Protest and the

Neoliberal Border. Lanham, MD: Rowman

and Littlefield.

Beck, Colin J. 2011 “The world cultural origins of

revolutionary waves: five centuries of

European contestation. Social

Science History 35,2: 167-207.

Benjamin, Medea and Andrea Freedman 1989 Bridging the Global Gap: A Handbook to

Linking

Citizens of the

First and Third Worlds.

Cabin John, MD: Seven Locks Press.

Blaazer,

David 1992 The Popular Front and the Progressive

Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge

University

Press.

Bond, Patrick 2012 The

Politics of Climate Justice: Paralysis Above, Movement Below Durban, SA:

University

of Kwa-zulu Natal Press

___________ (ed.) 2013 Patrick Bond Brics in Africa: anti-imperialist, sub-imperialist of in

between? Centre for

Civil Society, University of Kwa-Zulu-Natal.

Boswell, Terry and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral of

Capitalism and Socialism:

Toward Global Democracy. Boulder , CO : Lynne Rienner

Burawoy, Michael. 2012. “Our Livelihood Is at

Stake—We Must Pursue Relationships

beyond the University.” Network: Magazine of British Sociological Association, Summer

Brookes, Marissa 2013 “Varieties of power in

transnational labor alliances: an analysis of

workers’ structural, institutional and coalitional power in

the global economy” Labor

Studies Journal 38(3):181-200.

Calhoun,

Craig. 2013. “Occupy Wall Street in Perspective.” British Journal of Sociology 64 (1): 26–38.

Carroll William K and J. P. Sapinski Embedding

Post-Capitalist Alternatives: The Global Network of Alternative Knowledge

Production

Journal of World Systems Research Volume 19, Number 2, Pages

211-240

Castells, Manuel 2012 Networks of outrage and hope

: social movements in the Internet age Cambridge:

Polity Press

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1998 Global Formation, Chapter 5,

“World culture, normative integration and

community”

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Little field.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Ellen Reese 2008 “Global party formation in world historical

perspective” in Katarina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Global

Party

Formation.

London: Zed Press.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Matheu Kaneshiro 2009 “Stability and Change in the

contours

of Alliances Among movements in the social forum process” Pp. 119-

133 in David Fasenfest (ed.) Engaging Social Justice. Leiden:

Brill.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Bruce Lerro

2014 Social Change: Globalization from the Stone Age to the

Present. Boulder, CO: Paradigm

Chase-Dunn,

C. and

R.E. Niemeyer 2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” Pp. 35-57 in

Mathias Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.)

Transnational

Political Spaces. Campus Verlag:

Frankfurt/New York

Chase-Dunn, C. and Ian Breckenridge-Jackson 2014 “The Intermovement

Network in the

U.S. social forum process: Comparing

Atlanta 2007 with Detroit 2010”

Chase-Dunn, C. Alessandro Morosin and Alexis Álvarez 2014 “Social Movements and

Progressive

Regimes in Latin America: World Revolutions and Semiperipheral

Development”

in Paul Almeida and Allen Cordero Ulate (eds.) Handbook of Social

Movements across Latin

America, Springer

Chase-Dunn C.

and Ellen Reese. 2007. “Global Party Formation in World Historical

Perspective,”

in Global Political Parties , Pp. 82-120 edited by

Katarina Sehm-

Patomaki and

Marko Ulvila. London: Zed Books.

Cohn, Norman 1970 The Pursuit of the Millennium:

Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical

Anarchists of the Middle

Ages.

New York: Oxford University Press

____________1993

Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come: the Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

COMINTERN

Electronic Archive http://www.comintern-online.com/

Coyne,

Gary, Juliann

Allison, Ellen Reese, Katja Guenther, Ian

Breckenridge-Jackson,

Edwin Elias, Ali Lairy,

James Love, Anthony Roberts, Natasha Rodojcic, Miryam

Ruvalcaba,

Elizabeth Schwarz, and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2010 “2010 U.S. Social Forum Survey

of Attendees: Preliminary Report “Irows Working Paper # 64 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows64/irows64.htm

Curran, Michaela, Elizabeth A. G. Schwarz* and C Chase-Dunn 2014 “The

Occupy

Movement in

California” in Todd A. Comer ed. What Comes After Occupy?: The

Regional

Politics of Resistance. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows74/irows74.htm

Davis,

Mike 2006 Planet of Slums. London:

Verso

della Porta,

Donatella. 2005 “Multiple Belongings, Tolerant

Identities, and the Construction of ‘Another Politics’:

Between

the European Social Forum and the Local Social Fora,” Pp. 175-202 in Transnational Protest and Global Activism,

edited by Donatella della

Porta and Sidney Tarrow. Lanham, MD: Rowman

& Littlefield

Du Bois, Cora 2007 [1939] The 1870 Ghost Dance. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press

Eichstedt, Jennifer L. 2001. “Problematic White Identities and a Search for Racial Justice.” Sociological Forum

16(3):445–70.

Eschle, Catherine and Neil Stammers. 2004. “Taking Part:

Social Movements, INGOs, and Global Change.”

Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, Volume 29: 333-372.

Evans, Peter B. 2009 “From

Situations of Dependency to Globalized Social Democracy,”

Studies in Comparative

International Development 44:318–336

____________ 2010 “Is it Labor’s Turn to

Globalize? Twenty-first Century Opportunities and Strategic Responses”

Global Labour Journal (1)3: 352-‐379.

Fisher, William F. and Thomas Ponniah (eds.). 2003.

Another World is Possible: Popular Alternatives

to Globalization at the World Social Forum. London: Zed Books.

Freeden, Michael 2003 Ideology: A Very Short

Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freeman,

Jo 1970 “The tyranny of structuralessness” http://www.jofreeman.com/joreen/tyranny.htm

Fukuyama, Francis 2013 “The middle class revolution” Wall Street Journal, June 29

Gill,

Stephen 2000 “Toward a post-modern prince?:

the battle of Seattle as a moment in the

new politics of globalization” Millennium

29,1: 131-140

Gitlin, Todd 1993 The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage.

New York: Bantam Books

__________ 2012 Occupy Nation.

New York: HarperCollins

Goldfrank, W.L. 1978 “Fascism and world economy” Pp. 75-120 in Barbara Hockey

Kaplan

(ed.) Social

Change in the Capitalist World Economy. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Graeber, David 2013 The Democracy Project: A History, A Crisis, A

Movement. New York:

Spiegel

and Grau

(Random House).

Graham, Helen and Paul Preston (eds.) 1987 The Popular Front in Europe New York:

St.

Martin’s

Press

Hall, Thomas D, James V. Fenelon, Ian

Breckenridge-Jackson, Joel Herrera and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2014

“The global indigenous movement and the larger

web of antisystemic movements” Paper to be presented

at the

annual meeting of the Social Science History Association, Toronto, November

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2012. Declaration. New York: Argo Navis Author

Services

Herrera, Joel S. 2014 “Neoliberal

Reform and Latin America’s Turn to the Left”

honors thesis,

University of California-Riverside. Submitted for publication

Herkenrath, Mark 2011 Die Globalisierung

der sozialen Bewegungen: Transnationale

Zivilgesellschaft

und die Suche nach einer gerechten Weltordnung. Weisbaden: VS

Verlag

Hobsbawm, Eric J. 1994 The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991. New York:

Pantheon.

Hochschild, Adam 2005 Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the

Fight to Free an Empire’s

Slaves. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

James, C. L. R. 1997 Revolutionary

Marxism: Selected Writings 1939-1949. Brill

Juergensmeyer, Mark

2003 Terror in the Mind of God.

Berkeley: University of California Press

Johnston, Hank and Paul

Almeida (eds.) 2006 Latin American Social

Movements: Globalization,

Democratization

and Transnational Networks.

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Juris, Jeffrey S. 2008 Networking

Futures : the Movements Against Corporate

Globalization

Durham,

N.C. : Duke University Press

Kalleberg, Arne L 2009 “Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment

Relations in

Transition” American Sociological Review 74,1: 1-22

_____________2011 Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized

and Precarious Employment

Karatasli, Savan Savas, Sefika Kumral,

Ben Scully and Smriti Upadhyay 2014“Class,

Crisis,

and the 2011 Protest Wave:

Cyclical and Secular Trends in Global Labor Unrest” in

Immanuel Wallerstein,

Christopher Chase-Dunn and Christian Suter (eds.) Overcoming

Global

Inequalities. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Karides, Marina, Walda

Katz-Fishman, Rose M. Brewer, Jerome Scott and Alice Lovelace

2010 The United States Social Forum: Perspectives of a Movement.

Chicago: Changemaker

Keck, Margaret E. and Katherine Sikkink. 1998. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy

Networks in

International

Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Korotayev,

A.V., and J.V Zinkina. 2011.

“Egyptian Revolution: A Demographic Structural Analysis.”

Entelequia, Revista Interdisciplinar (13): 139–170.

Krinsky, John and

Ellen Reese. 2006. “Forging and Sustaining Labor-Community

Coalitions:

The Workfare Justice

Movement in Three Cities.” Sociological Forum 21(4): 623-658.

Lindblom, Charles

and Jose Pedro Zuquete 2010 The Struggle for the World: Liberation

Movements for the 21st

Century. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Luft, Rachel E. 2009. “Beyond Disaster Exceptionalism: Social Movement developments

in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.” American

Quarterly 61(3):499–527.

Lynd, Staughton and Andrej Grubacic 2008 Wobblies

and Zapatistas: Conversations on Anarchism,

Marxism and

Radical History. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

Mason, Paul 2013 Why Its Still Kicking Off Everywhere:

The New Global Revolutions London:

Verso

Martin, William G. et al, Making Waves: Worldwide Social Movements,

1750-2005. 2008

Boulder,

CO: Paradigm

McCarthy,

John D., and Mayer N. Zald. 1977. “Resource Mobilization and Social

movements: A Partial Theory.” American Journal

of Sociology 82(6):1212–41.

McIlwaine,

Cathy 2007 “From local to global to transnational civil society:

reframing

development

perspectives on the non-state sector.” Geography

Compass, Volume 1,

Number 6: 1252 –

1281.

McIntosh, Peggy. 2007. “White Privilege and Male Privilege.”

Pp. 377–84 in Race,

ethnicity, and gender: selected readings, edited by Joseph F Healey and Eileen

O’Brien.

Los Angeles: Pine Forge Press.

Meyer, David S. and Sidney Tarrow (eds.) 1998 Social Movement Society: Contentious

Politics for a

New

Century.

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Meyer, David S. and Catherine Corrigall-Brown

2005 “Coalitions and political context: U.S.

movements

against wars in Iraq” Mobilization 10:

327-344.

Meyer, John W. 2009 World Society:

The Writings of John W. Meyer. New York: Oxford University Press.

Obach,

Brian K. 2004 Labor and the Environmental Movement: The Quest for Common

Ground. Cambridge,

MA: MIT

Press.

Paulsen, Ronnelle, and Karen Glumm. 1995. “Resource Mobilization and the

Importance of Bridging

Beneficiary and

Conscience Constituencies.”

National Journal of Sociology 9(2):37–62.

Martin, William G. et al 2008 Making Waves:

Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005. Boulder,

CO:

Paradigm

Mies, Maria 1986 Patriarchy

and accumulation on a world scale : women in the

international division of

labour , London: Zed Books

Milkman, Ruth, Stephanie Luce and Penny Lewis 2013 “Changing

the subject: a bottom-up

account of Occupy

Wall Street in New York City” CUNY:

The Murphy Institute

Moghadam, Valentine M. 2005 Globalizing

Women: Transnational Feminist Networks. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press.

___________________2012. “Anti-systemic Movements Compared.” In Routledge

International

Handbook of World-Systems Analysis , edited by

Salvatore J. Babones and

Christopher Chase-Dunn New York: Routledge.

Morrow, Felix 1974 [1936] Revolution and Counter-revolution in Spain. New York: Pathfinder

Press.

Poppendieck, Janet. 1999. Sweet Charity?: Emergency Food and the End of Entitlement. New York:

Penguin

Patomaki, Heikki 2008 The Political Economy of Global Security. New York: Routledge.

Picketty, Thomas 2014 Capital in the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Pleyers,

Geoffrey. 2010. Alter-Globalization.

Cambridge, MA: Polity.

Reitan, Ruth 2007 Global

Activism. London: Routledge.

___________. 2012a. “Introduction: Theorizing

and Engaging the Global Movement:

From Anti-Globalization to Global Democratization.” Globalizations

Volume 9,

Number 3: 323-335.

___________. 2012b. “Coalescence of the Global Peace and Justice Movements.”

Globalizations

Volume 9, Number 3: 337-350.

____________

and Shannon Gibson 2012 “Climate change or

Social Change?

Environmental and Leftist

Praxis and Participatory Action Research” Globalizations

9,3:395-410.

Revolutionary

Communist Party 2010 Constitution for the

New Socialist Republic in North America.

Chicago: RCP Publications

Robinson, William I 1996 Promoting Polyarchy:

Globalization, US Intervention and Hegemony.

Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

______________2013 “Policing the global crisis” Journal of World-Systems Research Volume

19, Number 2:193-197

________________2006 Latin America and Global Capitalism.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University

Press.

______________2014 Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Humanity.

Cambridge: Cambridge

University

Press.