Anarchism in the Web of

Transnational Social Movements

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Joel

Herrera, John Aldecoa,

Ian Breckenridge-Jackson and

Nicolas Pascal

For presentation at the annual meeting of the International Studies

Association, Atlanta, Georgia, March 19, 2016. SC73:

Anarchist Perspectives on the Capitalist World Economy

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

Draft 3-12-16; 8307 words

![]()

This is IROWS Working

Paper #107

available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows107/irows107.htm

Abstract: Anarchists and anarchism have played a

visible role in global civil society since the 19th century and in

the New Global Left since it began to emerge in the 1990s. Horizontalism and social

libertarianism have been central components of the World Revolution of 20xx,

and were important aspects of the world revolutions of 1968 and 1989. Self-professed anarchists have participated

in the Social Forum process at the global, national and local levels and have

had an important influence on the emerging character of the contemporary world

revolution. We use surveys taken at a succession of Social Forum gatherings to

examine how self-identified anarchist activists are similar to, or different from,

the other attendees at these events and to investigate the links that this

movement theme has with other social movements. We note that some anarchist

ideas are more important in the discourse of the New Global Left than would be

suggested by the number of activists who say they are anarchists. We find that self-identified anarchists are

more radical, younger, more likely to be males and more likely to see the local

terrain of struggle as more important than national or global terrains in

comparison with other attendees at Social Forum events.

Anarchists and

anarchist ideas have been important elements of the New Global Left and the

current world revolution since the Zapatista rebellion in Southern Mexico

against the neoliberal North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994.The World

Social Forum process has been an important venue for the formation of a New

Global Left since 2001 (Santos 2006; Reitan 2007;

Smith et al. 2014). The founding of the World Social Forum in 2001 was a

reaction to the exclusivity of the World Economic Forum held in Davos,

Switzerland since 1971. The emergence of the World Social Forum signaled the

coming together of a movement of movements focused on issues of global justice

and sustainability. The social forum process has since spread to all the

regions of the world. [1]

The

Transnational Social Movement Research Working Group at the University of

California-Riverside[2]

began conducting paper surveys of the attendees at Social Forum meetings at the

world-level meeting held in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 2005. Similar surveys were

mounted at the United States Social Forum held in Atlanta, Georgia in 2007, the

world-level Social Forum held in Nairobi, Kenya in 2007 and the U.S. Social

Forum meeting held in Detroit, Michigan in 2010. The surveys included questions

on demographic characteristics, levels of activism, political attitudes and

involvement in a long list of movement themes[3]

(Chase-Dunn et al. 2007 Coyne et al. 2010; Reese et al.,

2008, 2012). In this article we use the Social Forum survey data to examine the

ways in which Social Forum

attendees who claim to be actively involved in anarchism are similar or

different from other attendees and from other attendees who also are actively

involved in other movements. We also use

our survey data to examine the connections that anarchists have with other

social movements based on their assertion of active involvement in other

movements.

Anarchism

in the geoculture and in the New Global Left

Individualism

and personal liberty have a long and complicated history. Many foraging

(hunter-gatherer) societies make it the responsibility of each person to find

particular spiritual allies and to cultivate a personal relationship with these

allies so that they may be called upon to provide power and medicine when

needed. But this kind of foraging individualism is embedded in a kin-based mode

of production in which individual persons are understood to be importantly

linked and co-dependent upon nature and other family members. These small-scale

societies highly value egalitarianism and the autonomy of rather small polities

(Flannery and Marcus 2012; Bettinger 2015; Scott

2009). The emergence of complex and hierarchical societies produces a new kind

of individualism beginning with the allegedly unique qualities of chiefs and

kings, and eventuating in the idea that each human is a unique being that is

endowed with important rights [little gods as John W. Meyer (2006: xxx) puts it.] Taoism in

ancient China asserted the individual’s right to contravene all social

institutions in pursuit of harmony with the force (Bender 1983). But Taoism is

very different from those versions of modern anarchism that demand heroic

action. Bringing the self into harmony with the force proscribes heroic action

(Raphals 2001).

Human rights emerged with the appearance of

confessional world religions in the Iron Age with the focus on each

individual’s personal relationship with god.

Secular humanism and modern citizenship are extensions of this idea of a

powerfully constituted unique person with great capabilities and

responsibilities. Anarchism as an

explicit political ideology emerged in the context of the English revolution,

employing a philosophy of radical Protestantism. Gerard Winstanley

and the True Levelers challenged property rights and the authority of both the

king and parliament. This kind of radical egalitarianism in religious

contestation had been a recurrent theme in Europe since medieval times (Cohn

1957).

Thus anarchist ideas are very old

and something reproduces them so that they reemerge again and again in somewhat

different forms. Some think that human biological nature is inherently

individualistic, (e.g. Turner and Maryanski 2008)

whereas others see a dynamic in which all forms of hierarchy and authority produce

reactions against themselves that legitimate a strong desire for autonomy and

the assertion that individual persons are capable of deciding important issues

for themselves. It is our observation

that, despite the fact that anarchists conceive of themselves, and are

perceived by others, to be oppositional figures within an emerging global

culture, their actions and ideas are importantly sanctified and reproduced by

global culture itself. The modern moral

order sanctifies radical individualism in profound ways. It is now commonly

believed that each individual has the right and obligation to construct a

unique sexual and gender identity rather than allowing the larger moral order

to assign conventional gender roles. Not

everyone agrees that this is a good thing, but many think that the old

authorities should not be allowed to interfere with a person’s rights and

duties with regard to identity construction.[4]

But anarchism is not just reproduced

in every generation. Its significance in

the

World Revolution[5]

of 20xx is much greater than the number of activists who identify as anarchists

or who are actively involved in anarchist movements. So this radical form of individual autonomy

has great appeal in the context of a powerful modernity that legitimates

individualism.

Robert

Schaeffer (2014) notes that social movements have learned from Roberto Michels’s analysis of the oligarchical tendencies of

political parties. The social movement literature has long observed that most

movements go through a life cycle in which they begin as inchoate, spontaneous

and unorganized mass movements and then turn into more institutionalized

organizations. When they get to the organizational phase they often become more

interested in the survival of the organization than in the pursuit of the

original goals of the movement. This observation has been confirmed by the

observation of what happened to the movements of the 19th and 20th

centuries, and social movement activists have devised methods for trying to

prevent the oligarchical tendencies. Mao Zedong mobilized the Red Guards

against the Chinese Communist Party to try to prevent the restoration of

capitalism in China (unsuccessfully). Anarchists abjure participation in

electoral politics and devise methods for direct democracy such as those

developed by the Occupy Movement. They also abjure hierarchical organizational

structures and prescribe horizontalism. The

autonomists in Europe abjure support from formal governments and advocate

independence from official resources. The Zapatistas in Southern Mexico refuse

to participate in Mexican electoral politics. The anti-statist ideas that were

proclaimed by the New Left in the world revolution of 1968 have found broad

support in the global justice movement. And the debacle of Syriza

in Greece reinforces the idea that involvement in electoral politics leads to

the sacrifice of radical alternatives to institutionalized structures.

Schaeffer (2014) also contends that

social movements that use violent tactics are less likely to be supported by

women. The World Social Forum Charter

proscribes movements that advocate armed struggle from sending representatives.

There has been a shift away from violent tactics in the New Global Left after

the terrorist antics of some leftist groups in the 1970s. And anarchists, who

used to advocate “propaganda of the deed,” have generally moved away from

assassination in the direction of property destruction. The debate about

tactics was heated in some locations of the Occupy Movement, especially Oakland,

California, but the direction has generally been toward non-violent forms of

confrontation. Beheadings and suicide

bombings are left to the radical Islamists.

Dana Williams (2016) notes that anarchists often display a greater

degree of hypermasculinity than other movements, and

our survey results show that anarchists

are significantly more likely to be male (58.0%) than the other

movements (42.3%). The reputation of the

Black Bloc would seem to confirm this, but the stress on property destruction

rather than injury to people implies that the anarchists are part of the larger

trend on the left away from violence as a tactic.

And

anarchism does not suffer as much as socialism and communism do from the

perceived heritage of what happened in the 20th century. Socialists

were major agents of the construction of the welfare state in the core, and

Communists took state power in the semiperiphery. Anarchists do not bear the

brunt of the perceived failures of the 20th century to the same

extent as Socialists and Communists do.

This allows them to plausibly claim that their political formulae have

not yet failed because they have not yet really been tried, except in small and

little known contexts. Important

anarchist political principles include participatory democracy, delegation

instead of representation, consensual decision-making, and refusal to

participate in electoral politics and other institutionalized political

mechanisms. Anarchists believe that formalized states with legal and coercive

powers over people are bad and unnecessary.

As a matter of principle, they do not participate in state institutions.

Of course, there are many different kinds of anarchism, and the history of

anarchist movements, though a global history, differs greatly from place to

place and has diverse meanings for contemporary political activists.

Nevertheless the responses we got in the four different survey venues are

generally consistent with one another.[6]

Who

are the anarchist activists in the Social Forum Process?

We have used survey responses from the four Social Forum meetings at which surveys were mounted to see how many attendees identified themselves as either strongly identified with, or actively involved in, anarchism. We also looked to see whether or not anarchist activists were similar to, or different from, other attendees regarding demographic characteristics and attitudes toward political issues.[7] The survey question was worded as follows:

Check all of the following movements with which you:

(a) strongly identify (b) are actively involved in:

In the Porto

Alegre 2005 survey this was followed by a list of 18 movement themes, including

“Anarchist.” In the other surveys the list included 27 movement themes.

|

|

Porto Alegre 2005 |

Nairobi 2007 |

Atlanta 2007 |

Detroit 2010 |

All |

|

Strongly identify with anarchism |

66 (11.7%) |

23 (5.5%) |

77 (14.7%) |

121 (25.9%) |

287 (14.5%) |

|

Actively involved in anarchism |

20 (3.6%) |

6 (1.4%) |

41(7.8%) |

46 (9.8%) |

113 (5.7%) |

|

Total

Number of Attendees surveyed |

563 |

422 |

524 |

468 |

1977 |

Table 1: Anarchism and activism in the Social Forum Process

Table 1 shows

the numbers and percentages of those who identified themselves as identifying

with, or being actively involved in, anarchism at each of the four venues.

A number of important observations are implied

by the findings in Table 1. Each of the surveys included around 500

respondents, but we are not entirely sure how representative our samples were

of all the people who attended the Social Forum meetings and so we are not sure

how well we can generalize to the whole group of attendees. A truly random

sample would have required a complete list of participants, which we did not

have. In order improve the representativeness of the sample, the surveys were

distributed at a variety of locations where people congregated at each meeting

(e.g. registration lines, workshops, food stalls, etc.). Combining the results

from all of the surveys increases the number of respondents to 1977, which is

useful for this study because we are examining a group that is small minority

among the whole sample of attendees. There are difficulties involved in

combining the results from the different surveys because in some cases the

wording of questions was somewhat different, and also because anarchism may not

have a uniform global meaning. It very likely means something different in

Brazil and Kenya from what it means in the United States. And self-identified anarchists who chose to

participate in Social Fora may differ in motivation and orientation in

different regions of the world. Our surveys were done in the major languages

that were used at the different venues (English, Portuguese, Spanish, French

and Swahili).

Table 1 shows that only a small

proportion of respondents report active involvement in anarchist movements—about

6% across all four meetings. These proportions are especially small in the

global meetings where only 3.6% and 1.4% of respondents said they were actively

involved anarchists (Porto Alegre and Nairobi, respectively). Although still

small, there were proportionately more anarchists at the U.S. Social Forum,

where close to 8% and 10% of respondents at the Atlanta and Detroit meetings,

respectively, were actively involved in anarchism. Table 1 also shows that

there were proportionately more attendees who say they strongly identify with

anarchism than who say they are actively involved in anarchism – from twice to

three times as many. Comparing rows 2 and 3 shows the large drop-off from

“strongly identify” to “actively involved”. We have found this same large

drop-off for all social movement themes in all of our surveys (e.g. Chase-Dunn

and Kaneshiro 2009). It is not unique to the anarchist movement. It means that

attendees take seriously the difference between sympathizing with a movement

and actually doing work for that movement.

Table 1 also shows that more than

one fourth (26%) of the surveyed attendees in Detroit say they strongly

identify as anarchists. And the

percentage that says they are actively involved was higher than at any of the

other venues (9.8%) including Atlanta.

We are not sure why there were proportionately more anarchists at the

Detroit meeting, but it might have to do with the increasing radicalism after

the financial crisis of 2008.

The following

tables compare, across the four venues, actively involved anarchists with all

other attendees and with all other attendees who were also actively involved in

at least one of the other social movement themes. We include other “actively

involved” because some of our findings imply greater radicalism on the part of

the anarchists activists, but we want to know if this is related to the focus

on anarchism, or is just a feature of all those who are actively involved. It

is generally known from social movement research that higher participation by

individuals is related to greater concern and we suspect that this may also be

related to greater radicalism.

Similarities

and Differences between anarchists and other attendees at the Social Fora

|

AGE |

|

Total |

||||

|

Not actively involved |

Actively involved (any) |

Anarchist |

||||

|

|

17 and under |

|

3 |

19 |

2 |

24 |

|

|

1% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

||

|

18 - 25 |

|

88 |

245 |

46 |

379 |

|

|

|

36%1 |

24% |

53%1 |

28% |

||

|

26 - 35 |

|

54 |

251 |

26 |

331 |

|

|

|

22% |

25% |

30% |

25% |

||

|

36 - 45 |

|

42 |

147 |

8 |

197 |

|

|

|

17% |

15% |

9% |

15% |

||

|

46 - 55 |

|

28 |

148 |

3 |

179 |

|

|

|

11% |

15% |

3% |

13% |

||

|

56 - 65 |

|

26 |

130 |

1 |

157 |

|

|

|

11% |

13% |

1%2 |

12%2 |

||

|

65 and over |

|

3 |

59 |

1 |

63 |

|

|

|

1% |

6% |

1% |

5% |

||

|

Total |

|

244 |

999 |

87 |

1330 |

|

1Z-value: 18-25 anarchists vs total --- (z= 4.81, p< .001) ***

2Z-value: 56-65 anarchists vs total --- (-3.06, p< .001) ***

Table 2: Age composition of anarchists

at the Social Fora

Anarchist activists are significantly younger than other

activists and than the whole sample of attendees. Fifty-three percent of the anarchist

activists are in the 18 to 25 year age group, whereas only 38% of the attendees

are in that group. And whereas 12% of the attendees were between 56 and 65

years old, only 1% of the anarchist activists are that old.

We also found that much less

likely to be religious than other attendees and that they are more than twice

as likely to say that they are radicals than the other activists. And as we

mentioned above, more of the anarchists activist are male than are the other

activists (58% vs. 42% (sig. P<.05).

Table 2 shows the racial/ethnic

composition of the actively involved anarchists compared with the racial/ethnic

breakdown of the other Social Fora attendees.[8]

|

|

Porto Alegre 2005 |

Nairobi 2007 |

Atlanta 2007 |

Detroit 2010 |

All |

|

Actively involved in anarchism |

|||||

|

White or Caucasian |

6 (33%) |

0 (0.0%) |

25 (66%) |

23 (60%) |

54 (54%)1 |

|

Black, African |

2 (11%) |

4 (68%) |

1 (3%) |

1 (3%) |

8 (8%)2 |

|

Latina/o |

3 (17%) |

1 (17%) |

4 (10%) |

5 (13%) |

13 (13%) |

|

Mixed or multi-ethnic/racial |

3 (17%) |

1 (17%) |

6 (16%) |

3 (8%) |

13 (13%) |

|

Arab/Arabic/Middle Eastern |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

Asian |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (10%) |

4 (4%) |

|

Indigenous |

1 (6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (3%) |

1 (3%) |

3 (3%) |

|

Other |

3 (17%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (3%) |

1 (3%) |

5 (5%) |

|

Total |

18 (18%) |

6 (6.0%) |

38 (38%) |

38 (38%) |

100 (100%) |

|

NOT actively involved in anarchism |

|||||

|

White or Caucasian |

147 (39.8%) |

94 (33.0%) |

193 (50.5%) |

181 (54.2%) |

615 (44.9%)1 |

|

Black, African |

54 (15%) |

117 (41%) |

51 (13%) |

33 (10%) |

255 (18.6%)2 |

|

Latina/o |

23 (6%) |

10 (3%) |

53 (14%) |

51 (15%) |

137 (10%) |

|

Mixed or multi-ethnic/racial |

33 (9%) |

10 (3%) |

38 (10%) |

34 (10%) |

115 (8%) |

|

Arab/Arabic/Middle Eastern |

3 (1%) |

6 (2%) |

7 (2%) |

3 (1%) |

19 (1%) |

|

Asian |

25 (7%) |

30 (10%) |

17 (4%) |

17 (5%) |

89 (6%) |

|

Indigenous |

7 (2%) |

9 (3%) |

2 (0.5%) |

3 (1%) |

21 (1%) |

|

Other |

77 (21%) |

9 (3%) |

21 (5%) |

12 (4%) |

119 (8%) |

|

Total |

369 (27%) |

285 (21%) |

382 (28%) |

334 (24%) |

1370 (100%) |

|

Strongly identify with anarchism |

|||||

|

White or Caucasian |

17 (39%) |

5 (31%) |

42 (65%) |

50 (62%) |

114 (56%) |

|

Black, African |

6 (14%) |

8 (50%) |

2 (3%) |

7 (9%) |

23 (11%) |

|

Latina/o |

3 (7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

6 (9%) |

10 (12%) |

19 (9%) |

|

Mixed or multi-ethnic/racial |

3 (7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

7 (11%) |

7 (9%) |

17 (8%) |

|

Arab/Arabic/Middle Eastern |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (1%) |

2 (1%) |

|

Asian |

4 (9%) |

1 (6%) |

1 (1%) |

2 (2%) |

8 (4%) |

|

Indigenous |

1 (2%) |

1 (6%) |

1 (1%) |

1 (1%) |

4 (2%) |

|

Other |

10 (23%) |

0 (0.0%) |

6 (9%) |

2 (2%) |

18 (9%) |

|

Total |

44 (21%) |

16 (8%) |

65 (32%) |

80 (39%) |

205 (100%) |

|

1: z=2.05, p< .05; 2: z= -3.11, p< .001 |

|

||||

Table 3: Racial/ethnic

composition of anarchists at the Social Fora

The majority of

anarchist both actively involved and strongly identified anarchists in our

entire combined sample identify as white (54% and 55%), which is considerably

larger than the proportion of whites that are not actively involved anarchists

(44%). This difference also holds for

the Atlanta and Detroit surveys, but not for the Porto Alegre or Nairobi surveys. So whiteness is related to anarchism in the

U.S. but not at the global meetings. In the combined sample actively involved

anarchists are less likely to be black (8% versus 18.6%) and so are strongly

identified anarchists (11.2% vs. 18.6%) and this difference holds for Atlanta,

Detroit and Porto Alegre, but not for Nairobi.

In Nairobi both the actively involved and the strongly identified

anarchists were more likely to be black and less likely to be white. The next two largest racial/ethnic groups are

Latinos and mixed-race persons—both at 13%. Both are slightly overrepresented

in comparison to non-anarchists and strongly identified anarchists but these

differences are not statistically significant.

We also found that more anarchists say they are working class (38%) than other activists (27%), and more anarchists claim that they are lower class (20%) than do other activists (10%).

|

Table 4 Attitude toward

capitalism |

||||

|

Non-activist |

Activist |

Anarchist |

All |

|

|

Reform it |

179

(56%) |

558

(41%) |

19

(18%) |

756

(42%) |

|

Abolish it |

105

(33%) |

726

(53%)2 |

81

(76%)1, 2 |

912

(51%)1 |

|

Neither |

35

(11%) |

80

(6%) |

6

(6%) |

121

(7%) |

|

Total |

319 |

1364 |

106 |

1789 |

|

1Z-value: 5.088*** 2Z-value: 4.624*** *p

< .05 (two-tail), **p < .01 (two-tail), ***p < .001 (two-tail) |

||||

The results in Table 4 suggest that

anarchists are radically anti-capitalist in comparison to other activists as

well as non-activists. Fewer anarchists want to reform capitalism, and

three-fourths of the anarchists think capitalism should be abolished only one

half of the other actively involved and one third of the non-activists want to

abolish capitalism. Z-tests show that these differences are statistically

significant.

|

Table

5 Attitude toward the World Bank In

the long run, what do you think should be done about these existing global

institutions: World Bank |

||||

|

Non-activist |

Activist |

Anarchist |

All |

|

|

Reform |

110 (52%) |

322 (34%) |

7 (8%) |

439 (35%) |

|

Replace |

30 (14%) |

204 (21%) |

19 (23%) |

253 (20%) |

|

Abolish |

58 (27%) |

406 (42%)2 |

54 (66%)1, 2 |

518 (41%)1 |

|

Do

Nothing |

14 (7%) |

27 (3%) |

2 (2%) |

43 (3%) |

|

Total |

212 |

959 |

82 |

1253 |

|

Notes:

This table does not include respondents at the Porto Alegre meeting. 1Z-value: 4.362*** 2Z-value: 4.131*** *p

< .05 (two-tail), **p < .01 (two-tail), ***p < .001 (two-tail) |

||||

Table 5 shows

the pattern of responses to a question about global institutions, specifically

the World Bank. The Porto Alegre survey is not included because this question

was not asked in a way that clearly separated the World Bank from the

International Monetary Fund and the United Nations in the Porto Alegre survey.

The results in Table 4 indicate that 66% of the actively involved anarchists

are in favor of abolishing the World Bank, whereas only 42% of the activists in

other movements want to abolish the World Bank.

The differences between these proportions and between anarchists and the

overall sample are statistically significant. The same differences were found

in response to questions about the International Monetary Fund and the World

Trade Organization.

|

Table

6 Attitude toward the United Nations In

the long run, what do you think should be done about these existing global

institutions: United Nations |

||||

|

Non-activist |

Activist |

Anarchist |

All |

|

|

Reform |

158 (74%) |

713 (76%) |

37 (46%) |

908 (74%) |

|

Replace |

17 (8%) |

122 (13%) |

19 (23%) |

158 (13%) |

|

Abolish |

14 (7%) |

57 (6%)2 |

24 (30%)1, 2 |

95(8%)1 |

|

Do

Nothing |

23 (11%) |

49 (5%) |

1 (1%) |

73 (6)% |

|

Total |

212 |

941 |

81 |

1234 |

|

Notes:

This table does not include respondents at the Porto Alegre meeting. 1Z-value: xxxxxx 2Z-value: xxxxxx *p

< .05 (two-tail), **p < .01 (two-tail), ***p < .001 (two-tail) |

||||

A similar

pattern is found in responses to a question about the United Nations, but there

is also interesting difference. As with the other international institutions

discussed about, anarchists are more likely than other attendees to favor

abolition and less likely to favor reform.

But in comparison with the other international institutions (the World

Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization)

anarchists are much more supportive of the United Nations. Only 30% of the

actively involved anarchists want to abolish the U.N. whereas 66% want to

abolish the World Bank.

|

Table

7 Democratic World Government Do

you think it is a good or bad idea to have a democratic world government? |

||||

|

Non-activist |

Activist |

Anarchist |

All |

|

|

Good

idea and plausible |

126 (39.7%) |

497 (38.8%) |

32 (33%) |

655 (38.6%) |

|

Good

idea but not plausible |

106 (33.4%) |

450 (35.1%)2 |

17 (17.5%)1, 2 |

573 (33.8%)1 |

|

Bad

idea |

85 (26.8%) |

334 (26.1%)4 |

48 (49.5%)3, 4 |

467 (27.6%)3 |

|

Total |

317 |

1281 |

97 |

1695 |

|

1Z-value: -1.104 2Z-value: -1.133 3Z-value: 4.566*** 4Z-value: 4.893*** *p

< .05 (two-tail), **p < .01 (two-tail), ***p < .001 (two-tail) |

||||

The surveys also asked Social Fora attendees about their attitude

toward the idea of a democratic world government. Table 7 shows that anarchist

activists are more likely to think that a democratic world government is a bad

than those who are not involved in anarchist movements and this is not related

to active involvement in general. These differences are statistically

significant.

|

Table 8 Best Level for

Solving Problems Out of the following,

which level is most important for solving the majority of contemporary

problems? |

||||

|

Non-activist |

Activist |

Anarchist |

All |

|

|

Communities/sub-national |

177

(59%) |

730

(59.1%) |

76

(78%) |

983

(60.2%) |

|

Nation-states |

27

(9%) |

126

(10.2%) |

4

(4%) |

157

(9.6%) |

|

International/global |

96

(32%) |

380

(30.7%) |

17

(18%) |

493

(30.2%) |

|

Total |

300 |

1236 |

97 |

1633 |

|

1Z-value: 3.495*** 2Z-value:

3.666*** *p

< .05 (two-tail), **p < .01 (two-tail), ***p < .001 (two-tail) |

||||

The surveys also asked about which level is

most important for solving the majority of contemporary problems: communities,

nation-states, or international/global. Table 8 shows that 78 percent of

anarchist activists indicated that the community level is most important and

this percentage was higher than for those who were actively involved in other

movement themes (59.1%). The differences in proportions are statistically

significant according to the z-test.

|

Table 9 Global Social

Movement? Do you consider yourself

to be a part of a global social movement? |

||||

|

Non-activist |

Activist |

Anarchist |

All |

|

|

No |

88

(38.3%) |

141

(14.2%) |

7

(7.6%) |

236

(18%) |

|

Yes |

142

(61.7%) |

851

(85.8%)2 |

85

(92.4%)1, 2 |

1078

(82%)1 |

|

Total |

230 |

992 |

92 |

1314 |

|

Notes:

This table does not include respondents at the Porto Alegre meeting. 1Z-value: 2.6141** 2Z-value: 1.8092 |

||||

But the local

focus indicated by the results in Table 8 is somewhat contradicted by the

results in Table 9. The surveys asked attendees whether or not they think of

themselves as involved in global social movement. Ninety-two per cent of the

anarchist activists said yes, and this was a higher percentage than those that

were actively involved in other movement themes and with the total sample. The

difference between anarchists and other activists is not statistically

significant according to the z-tests reported in Table 9, but the difference

between anarchists and the total sample is.

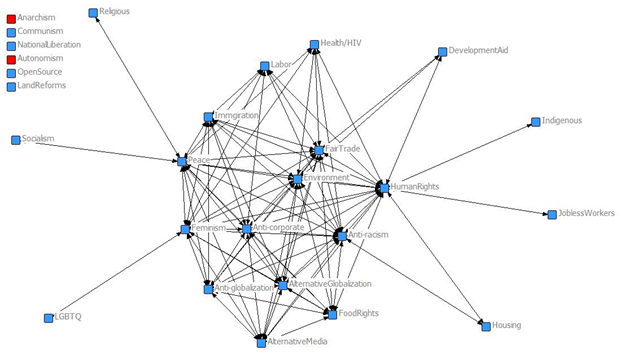

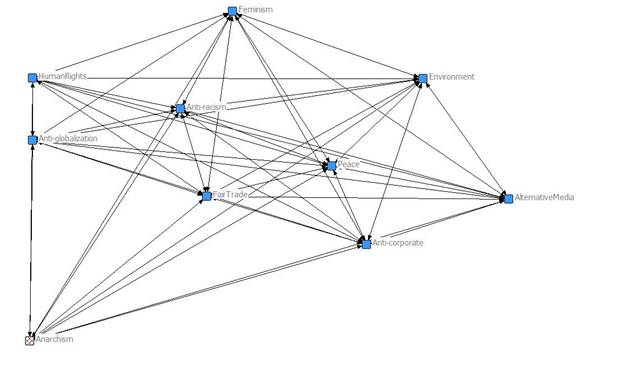

The

connections that anarchist activists have with other social movements

Social movement

organizations may be integrated both informally and formally. At the

formal level, organizations may provide legitimacy and support to one another,

and strategically collaborate in joint action. Informally, they are connected

by the choices of individuals who are active participants in more than one

movement. Such informal linkages enable learning and influence to pass among

movement organizations, even when there may be limited official interaction or

leadership coordination. The extent of formal cooperation among movements

within “the movement of movements” both causes and reflects the informal

connections. In the analysis below we assess the extent and patterns of

informal linkages among social movement themes based on the responses we got

from our four surveys of attendees at the four Social Fora meetings we studied.