The Global Right in the World Revolutions of 1917 and 20xx[1]

Chris Chase-Dunn, Jennifer S.K. Dudley and Peter Grimes

Institute for Research on World-Systems; University

of California-Riverside

v. 10-12-18 9407 words

This is IROWS Working Paper #118 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows118/irows118.htm

Abstract: An understanding of the current global resurgence of

right-wing national and transnational “neo-fascist” social movements can best

be understood by comparing the recent movements with the global political

circumstances happening in the first half of the 20th century. Such a

comparison can help us understand the similarities and differences between then

and now to gain insights about what could be the consequences of the

reemergence of populist nationalism and fascist movements. This paper uses the

comparative evolutionary world-systems perspective to study the global right

from 1900 to the present. We see fascism as a hybrid of capitalism and a tributary

mode of accumulation that co-evolves with capitalism and socialism. The point

is to develop a better understanding of 21st century fascism, populist

nationalism and authoritarian practices and to help construct a praxis for the

New Global Left.

The world-system

literature on world revolutions has tended to focus on the rebellions and

social movements of the Left to see how these clustered assemblages of

collective behavior from below have been related to changes in the larger

structural and institutional context of world politics and capitalist

development. The constellations of social movements from below have been

analyzed and compared with one another in order to understand their political

ideologies and social constituencies and the effects that they have had on the

evolution of global institutions and regimes. But reactionary and right-wing

movements have largely been left out of this analysis.

The exception is W.L. Goldfrank’s

(1978; 1990) analysis of fascism in world historical perspective, a valuable

review of the theories and comparative literature on 20th century

fascism that builds on the approach developed by Karl Polanyi to flesh out an

analysis at the level of the global system. Goldfrank sees 20th

century fascism as a reaction to the crises of the capitalist world-economy,

employing Polanyi’s idea of the double-movement in which societies become

over-commodified and then react against commodification. But the rise of

right-wing sects, movements and parties in the last few decades and obvious

similarities between populist nationalisms and the use of symbols and tactics

taken from the playbook of 20th century fascism require an update

and rethinking of Goldfrank’s seminal work that also

takes more recent scholarship into account.

The comparative evolutionary world-systems perspective

The world-systems

perspective presents a structural interpretation of the cycles and trends that

have constituted the expansion and evolution of global capitalism (Arrighi 1994; Wallerstein 2011; Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2016). It focuses on the global core/periphery

hierarchy and global class relations (Amin 1980).[2] This holistic structural

approach in which the whole global system is the unit of analysis allows us to

see both the similarities and differences between the contemporary world

historical period and earlier similar periods. The expansion and deepening of

capitalism have created the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers; waves of

colonization in which European powers subjugated most of Asia, the Americas and

Africa using military and economic power to mobilize peripheral capitalism

based on coerced labor (slavery and serfdom); and the reactive waves of

decolonization leading to the juridical incorporation of these former colonies into

the original European system as sovereign states. The expansion and deepening

of capitalist production and the increasing size of the nation-states that

played the role of hegemons were driven by movements of resistance that were

located both within core polities and in the periphery and the semiperiphery.

Each of the capitalist hegemons

(the Dutch in the l7th century, the British in the 19th century

and the United States in the 20th century) were themselves once

formerly semiperipheral states that rose to core status in struggles with

contending great powers. Their successes were partly based on their abilities

to deal with resistance from below more effectively than their competitors, as

well as on comparative advantages in production and institutional innovations (Wallerstein

1984).

It

is important to accurately grasp both the structural similarities and the differences

between the current world historical period and earlier periods that were

similar but also dissimilar. The United States has been in decline in terms of

hegemony in economic production since 1945 and this has been similar in many

respects to the decline of British hegemony in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries (Chase-Dunn et al 2011).

Giovanni Arrighi (2006) noted that the period of British hegemonic

decline (1870-1914) moved rather quickly toward military interimperial rivalry

because economic challengers such as Germany and Japan were developing powerful

military capabilities that were used to contest the Pax Britannica. The U.S.

hegemony differed because the post WWII United States ended up as the single military

superpower, a status that was amplified by the demise of the Soviet Union. After

World War II, Japan and Germany could not play the military card because they

were stuck with the consequences of having lost the last World War. And they

benefited economically by allowing the U.S. to provide security. This, and the

immense size of the U.S. economy, slowed the process of hegemonic decline

compared to the British, but the decline of U.S. hegemony has itself invigorated

counter-hegemonic movements of both the Left and the Right that

are opposed to the contemporary world order.

The declining power of

the U.S. poses huge challenges for global governance. Newly emergent national

economies such as India and China need to be integrated into the global

structure of power but, as in the 19th century with Germany and

Japan, this is a complicated and conflictive process. The unilateral use of

military force by the Bush administration and America-Firstism

of the Trump administration have further delegitimized the

institutions of global governance and increased the possibility of serious interimperial rivalry.

These developments

parallel, to some extent, what happened a century ago, increasing the likelihood

of another Malthusian correction such as what occurred in the first half of the

20th Century. At the beginning of the 20th Century the global

population was 1.65 billion, whereas in 2018 there are 7.7 billion humans on

Earth. At the beginning of the 20th century fossil fuels were

becoming less expensive as oil was replacing coal as the major source of energy

(Grimes 1999, 2003; Podobnik 2006). It was this use

of inexpensive non-renewable energy that facilitated the abolition of slavery

and serfdom and made the geometric expansion and industrialization of humanity

possible.

Now we are facing global

warming as a consequence of the spread and rapid expansion of industrial

production and energy-intensive consumption. None of the existing alternative

technologies offer low cost energy of the kind that made the past expansion

possible. Many believe that overshoot has already occurred in terms of how many

humans are alive, and how much energy is being used by some of them, especially

those in the Global North. Global climate change is already increasing the

problems of global governance and inequalities in ways radically different than

during the decline of British Hegemony in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries. And this contextual

difference is likely to produce altered forms of counter-hegemonic movements. For

example, the New Global Left has seen the rise of an important climate justice

movement (Bond 2012). And right-wing populist politicians have denied the

existence of anthropomorphic (human-caused) global warming and have advocated

the dismantling of those environmental regulations that have been intended to

reduce global warming and pollution.

World Revolutions

The rise and fall of the

hegemonic core powers over the past four centuries have produced institutional changes

that have made possible the successive global waves of capitalist accumulation

(Arrighi 1994). One example is the expansion of

global production, which required accessing raw materials to feed the new

industries, and food to feed the expanding populations, each already adding to global

warming (Bunker and Ciccantell 2005). Hegemonic

core powers knew that coercion is a very inefficient means of domination, so

they sought legitimacy by proclaiming leadership in advancing civilization and

democracy. But the ideals contained in these claims were also appropriated by

those below who sought to protect themselves from exploitation and domination.

So, the contending core powers had to adapt to and address the claims of

challengers within their home societies and in the Global South. World orders

are not just coercive; they also require normative and institutional legitimacy

(Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000: 53-64; Linebaugh and Redicker 2000).

There has been an ideological and political struggle in both the

Europe-centered world-system and in the East Asian world-system[3] for centuries, sometimes

fueling strong social movements, regime changes and wars of national liberation

from colonialism.

Most histories have led us to define revolutions

as a national scale events in which new social forces came to state power and

restructured social relations (Goldstone 1997; 2014). Yet at the world-system

level this concept does not easily apply. There is no global state to take

over. But there is a global polity, a world order composed of competing and

cooperating states and other actors. exists. It is that world polity or world

order that is the arena of contestation within which world revolutions have

occurred and that world revolutions have restructured.[4]

Boswell and

Chase-Dunn (2000) designated periods of global rebellions that had long-term

consequences for changing world orders in the Europe-centered system. Years

that symbolize these major world revolutions (after the Protestant Reformation)

are 1789, 1848, 1917, 1954, 1968 and 1989. Arrighi, Hopkins and

Wallerstein (1989) analyzed the world revolutions of 1848, 1917, 1968 and 1989.

[5] They observed that the

demands put forth in a world revolution did not usually become

institutionalized until a later consolidating revolt had occurred. So, the

revolutionaries appeared to have lost in the failure of their most radical

demands, but later enlightened conservatives managing hegemony incorporated some

of these demands as reforms to cool out resistance from below and to legitimate

their own leadership claims.

This view of the modern

world-system as having constituted a single arena of political struggle and

economic competition since the long sixteenth century implies that there has

been an evolving global civil society since then (Kaldor 2003). Global

civil society includes all the actors who

consciously participate in world politics. In the past, it consisted

primarily of statesmen, religious leaders, scientists, financiers, cosmopolitan

literary figures[6]

and the owners and top managers of chartered companies such as the Dutch and

British East India Companies. These elites saw the global arena of political,

economic, military and ideological struggle as one unit (Braudel,

1984). They promoted religious and secular social movements in which

masses were sometimes mobilized, as in the Protestant Reformation. In turn, reactions

such as the Catholic Restoration constituted part of the Global Right. The

Society of Jesus (Jesuits) was an early instance of a consciously transnational

political party (Chase-Dunn and Reese 2007). Since the world revolution of 1789 non-elites

began consciously participating in world politics. A series of “global left”

transnational social movements arose. Though the Haitian

revolution of 1804 was mainly a revolt of slaves on the sugar plantations in

Haiti, some of the leaders were literate former slaves that had been inspired

by the ideas of the French and American revolutions (Linebaugh and Rediker 2000; Dubois 2004).

While global civil

society is still a small minority of the total population of the earth, the

falling costs of communication and transportation have enabled more non-elites

to become transnational political actors and increased the extent to which

local revolts have been able to communicate and coordinate with one another.

But local revolts have always played a role in world revolutions because colonial

powers reacted to them. Global consciousness is not necessary for global

consequences. An objective global interaction network of indirect connections

existed long before most people became aware of it. But the spread of global consciousness

has made globalization an increasingly contentious aspect of world politics.

Our earlier research

focused on what Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2006) called the “new global left” and compared it with earlier

incarnations of the global left (Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro 2009; Chase-Dunn and Niemeyer 2009; Smith et

al 2014). This movement of movements

includes environmentalists, feminists, workers organizations, the peace

movement and many smaller movements. The global left is part, but not all, of

global civil society. Other important contemporary transnational political actors

are the forces organized around the World Economic Forum, and the new reactionary

populist and neo-fascist movements and the jihadists (Anderson, 2005; Zuquete and Lindblom 2005; Moghadam 2009; Bond 2013).

Another world revolution

has been brewing since the last decades of the 20th century. Chase-Dunn and Niemeyer (2009) have called it

the world revolution of 20xx (because it is not yet clear what the key symbolic

year should be). They claim that it began with the anti-International Monetary

Fund riots in the 1980s and the Zapatista revolt in Southern Mexico in 1994.

World revolutions are

hard to study and difficult to compare with one another because they are very complex

“events”. The time periods and places to include (and exclude) are hard to

judge. They each have had different mixes of social movements,

rebellions and revolutions, and counter-movements. And they have occurred unevenly in time and

space. What have been the bases for cooperation and competition uniting

these diverse movements? How did they influence each other?[7] How did the revolts

and resistances affect the struggles among the elites in their efforts to

maintain their positions or gain new advantages? The scientific study of world revolutions is

yet in its infancy but in this article, we are raising a new issue: what has been the nature of the global right

in the 20th and 21st centuries, and how was the 20th

century version similar or different from what is emerging now in the 21st

century?

Evolutionary Logics of Accumulation

The comparative evolutionary world-systems

perspective sees human prehistory and history as having evolved from a

kin-based mode of accumulation that regulates interaction by means of

consensually held norms to tributary modes that add institutionalized and

organized coercion over the top of kin-based forms, to the capitalist mode that

is based on accumulation of profits from commodity production and financial

services.

The tributary modes of accumulation have directly

used state power (institutionalized coercion based on the law and its

enforcement) to extract surplus product from populations through taxes,

tribute, serfdom and slavery. States that mainly employ tributary accumulation have

usually been controlled by military, priestly and land-owning elites whose

wealth in mainly based on this form of accumulation. The tributary states emerged

during the Bronze Age out of kin-based chiefdoms. They engaged in military

competition with one another for territorial conquest and tribute. In contrast, capitalism accumulates surplus

value by making profits on the production of commodities and financial

services. Although early capitalism grew in areas beyond tributary control, the

growth of system-wide trade in the Iron Age, promoted by semiperipheral

capitalist city-states, encouraged the internal commercialization of tributary

empires (Sanderson 1995). Since the 16th

century CE capitalism has become the predominant logic of the Europe-centered

(modern) world-system in a series of waves in which nation-states have increasingly

come to be controlled by capitalists and market forces and money have deepened and

geographically expanded their influence. But the tributary modes have continued

to reassert themselves during periods of crisis and have co-evolved with capitalism. The Hapsburg Empire, the

Napoleonic episode, 20th century state communism (the Soviet Union

and the Chinese Peoples Republic) and the fascist movements and regimes of the

1930s and 1940s were all resurgences of the tributary modes in which

institutionalized coercion in different forms was the main backbone of

accumulation.

We

can now see Fascism in the larger view of world history, as a hybrid of

capitalism and the tributary mode of production that emerged after economic

institutions had evolved high levels of commodification. Twentieth century

fascism emerged as a reactionary populist-nationalist movement in a context of

economic and political crises, which was then joined by big capitalist

land-owners and industrialists who sought to use it to counter the radical

challenges coming from the left. It became authoritarian state control of the

economy and the polity at the behest of privately-owned large corporations. Fascism

is the latest hybrid form that the tributary modes have taken, and it continues

to evolve, as seen in the differences between 20th and 21st

century fascism discussed below.

Definitions of Fascism and World Historical

Comparisons

It is important to review the

efforts of social scientists to define fascism to go beyond the use of this

term as an expletive. W. L. Goldfrank (1978) and Michael

Mann (2004) noted that fascism as a unitary phenomenon is difficult to define because

it was not uniform but varied greatly by location and context and it evolved

over time. It is particularly hard to define fascist ideology because the

leaders were often extremely pragmatic and inconsistent in their choice of

ideologies. One of the key features of fascism – hypernationalism—

was constructed differently in dissimilar locations, which produced locally specific

internal and external enemies.[8] Definitions of fascism in the scholarly

literature vary in width, choice of characteristics and in emphasis on

different characteristics. Some

emphasize the nature of deeds (e.g. Paxton 2004) while others focus more on

ideology (e.g. Griffin 1991). Michael Mann (2004: 13) strikes a good balance

between these:

I define fascism in terms of the key values,

actions and power organizations of fascists. Most concisely, fascism is the

pursuit of a transcendent and cleansing nation-statism

through paramilitarism.

Both Mann’s (2004) and

Robert Paxton’s (2004) excellent studies realize that this definition may not exactly

fit somewhat similar phenomena that have emerged since 1945, but they are both

willing to examine the nature of late 20th and early 21st

century fascisms to tease out the similarities and the differences. A working

definition of fascism and its traits helps both researchers and opponents to

identify emergent contemporary fascist and similar threats. One or two of the characteristic

features may not be present in a contemporary right-wing movement but it may

still be accurate to designate it as neo-fascist.

Our studies of the new global left have

used survey research to study the network of linked movements that have emerged

as the global justice movement in the World Social Forum process (Smith et al 2014; Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro

2009; Chase-Dunn et al 2014; Almeida

and Chase-Dunn 2018; 2019). The

assumption that the participants in the Social Forum process were

representative of the transnational social movements of the Left in the whole

world is somewhat problematic (see Reese et

al 2015). But trying to locate a single venue for the global right is even

harder. The only venues that might help such a study would be the World

Economic Forum (WEF) or the Bilderberger Group. But researchers are not allowed

to carry out surveys at these gatherings, precluding research. Nevertheless, we

will try to prehend the structure of the contemporary global right and to estimate its

structure and nature in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries.

We use Mary Kaldor’s (2003)

definition of global civil society: all the actors who are consciously engaged

in contesting power and ideology on a global scale, though our definition

includes groups that go beyond most definitions of civility (e.g. terrorists). Our view of the global polity is organized

around Immanuel Wallerstein’s (2012) study of the rise of centrist liberalism

in the 19th century.[9] We see the neoliberal

globalization project that emerged in the 1970 as a recent expression of the

centrist liberalism that emerged in the 19th century.[10]

Neoconservatism

emerged in the last decade of the 20th century as a response to the

decline of U.S. economic hegemony. So,

neoliberalism is in the center with the global right and the global left on

each flank. Inspired by Kaldor, our conception of the contemporary global right

includes neo-conservatives, conservative and reactionary think-tanks and media

outlets, populist nationalists, anti-immigrant movements, neo-fascists, male

supremacists, racial supremacists, and reactionary religious fundamentalisms

(radical jihadists, Hindu nationalists and Christian identity groups). This broad constellation of contemporary

counter-hegemonic far right groups suggests comparisons with analogously

diverse players in the world revolution of 1917 (WR1917). We know from studies

of fascism that in some countries fascism was posed as secular national

socialism and syndicalism, whereas in others it was formulated in religious

terms. Italian

and German fascisms were anticlerical. However, religion-based fascism did

exist. A perceived “ideological crisis

within the state” was tied to the rise of fascism in Turkey. Paxton (2004: 203)

cites examples of religious fascism such as the “Falange Española, Belgian Rexism, the Finnish Lapua

Movement, and the Romanian Legion of the Archangel Michael”. [11] But how did other

religious fundamentalisms (Islam, Christianity, etc.) interact with the social

movements of the right and the left in WR1917?

Immanuel Wallerstein

(2017) explains the rise of Islamic fundamentalism as a reaction to the

economic downturn of the 1970s, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the

failure of the movements of the world revolution of 1917 to produce a more

humane and sustainable global society, and so their loss of popular support. He

contends out that religious identities became less and less important in

politics from the Protestant Reformation until 1970.[12] He also points out

the ambiguous relationship that religious fundamentalism has had with states. God’s

law is higher than state law, but the fundamentalists try to take state power

to impose god’s law.

Religious fundamentalism since

the 1970s has also been a reaction against the world revolution of 1968, further

commodification of traditional functions formerly handled by families or

communities, gains for gender and racial equality and individual freedom

(disempowering traditional tribal authority). Religion plays an important role

in contemporary right-wing social movements as a force for mobilization,

cohesion-building and the effort to restore the authority of patriarchal

families and religious leaders. Religions provide frames and imagined golden

ages that are used by many right-wing movements to build their ideologies (Whittier

2014). One reason why religious fundamentalism

became counter-hegemonic after 1970, but was not very important in the world

revolution of 1917, is that fundamentalism became a functional

counter-hegemonic substitute for revolutionary Marxism and related Leftist

ideologies that had been the basis of the Global Left in the 20th

century (Grimes, 2003). Wallerstein contends

that one of the causes of the recent rise of political/religious fundamentalism

was the perceived failure of secular counter-hegemonic movements. It is as if there is an ideological menu

embedded in the geoculture from which individuals and

groups take frames, and when one appears to have been discredited others are selected.

In the U.S., Bible

study groups provided the backdrop for recruitment to right-wing groups, while

right-wing rhetoric “mourns” the movement away from white, Christian roots (Polletta and Callahan 2017: 6). A conquest narrative and

premillennial apocalypticism are bound together by a blood rhetoric, all tied

directly to religious sources in Hebrew, Islamic and Christian scriptures (Gorski

2017). Religious boundaries are transformed into racial ones, synthesizing

religious and ethnic nationalism. These narratives have come to life, sometimes

literally as in the Puritan conquest of the native peoples of North America,

and sometimes allegorically as a way to reinforce racial boundaries and harken

back to a day of white, Christian primacy (Gorski 2017). Islamic

neo-fundamentalism mirrors its Christian counterpart. A global rise in militant

Islam, tied to calls for a return to strict adherence to religions tenets, has emerged

as a reaction to the neoliberal globalization project. Reactionary movements reject

traditional Muslim and modern Western culture, globalization, and

universalizing secular modernism and commodification.

Fascist movements and regimes in the 20th century

were authoritarian attacks on democracy and the rule of law, but their

hyper-nationalism further institutionalized nationalism as an important form of

modern collective solidarity, and they served to provoke a cosmopolitan

reaction against extreme forms of nationalism that became embedded in the geoculture and the international institutions that emerged

after World War II (the United Nations and the international financial

institutions).

Comparing the Global Right with the Global

Left

Our construction of the geoculture as an evolving constellation of contending

ideologies of the right, center and left notes that these assemblages interact

with one another as well as reflecting the changing contexts formed by the institutional

structure of the modern world-system (Nagy 2017). One obvious difference between much of the

global right and the global left is with respect to nationalism. The global

left in the World Revolution of 1917 was explicitly internationalist. Most socialists, communists and anarchists

believed in proletarian internationalism and condemned nationalism as false

consciousness that was promoted by capitalists to undermine the class struggle

and to get workers to go to war. This was an important instance of secular

global humanism and cosmopolitanism, though it was mainly understood as

international class solidarity. It came to grief when the German state tricked

the German socialists into voting for war credits at the outbreak of World War

I, thus abrogating an agreement among the national parties of the Second

International to not go to war and kill each other at the behest of their

national capitalists. It was this development that sealed Vladimir Lenin’s

disgust with the labor movements of the core and provoked his turn to the “Third

Worldism” of the Third International (Claudin, 1975).

Internationalism,

transnational humanism and Global Southism (formerly

Third Worldism) continue to be important

characteristics of the New Global Left in the World Revolution of 20xx (Steger,

Goodman and Wilson 2013; Carroll 2016).

Fascist movements before and after World War I attacked

the workers movements and socialist parties both because the fascists opposed

class struggle in favor of organic nationalism and because they opposed the

internationalism and pacifism of the Left (Paxton 2004). Attacking peasant

unions and labor unions also gained the fascists the support of land owners and

some large capitalists, and this became an important source of powerful elite

support and finance for those fascist sects that were able to move on to become

mass movements and to take over national regimes. But hypernationalism

was also an obstacle to transnational and international cooperation and

organization. The fascists did try to

organize a fascist international during the late 1920s and the 1930s (Laqueur and Mosse 1966), but their own commitment to the myths of nationalism

stood in the way (Paxton 2004: 20, Fn. 83).

This was, and still is, an important difference and conflict between the

global right and the global left.[13]

Dani Rodrik (2018) contends that two kinds of populism have

arisen to contest the neoliberal globalization project. In Latin America in the

1980 and the 1990s the structural adjustment policies of the International

Monetary Fund that required austerity and privatization were supported by

neoliberal national politicians who attacked the labor unions and parties of

formal sector workers, but this produced a populist reaction in many countries in

which progressive politicians were able to gain election by campaigning against

these policies and by mobilizing the residents of the “planet of slums” (Chase-Dunn

et al 2015). This phenomenon was

called the “Pink Tide.” Regimes based on

left-wing populism emerged in most Latin American countries, and Rodrik rightly

sees this as a reaction against the neoliberal globalization project. Right

wind populism emerged, and is still emerging, in countries of the Global North

in which neoliberal globalization produced deindustrialization and many workers

lost their jobs. This occurred in

contexts in which it was easier for politicians to blame immigrants and minorities

than to point the finger at the big winners of global capitalism. And some of

the big winners provided support for the politics of hypernationalism,

zenophobia, racism and sexism that are the working

muscles of right-wing populism and neofascism.

Right-wing populist politicians exploit cleavages along

cultural lines, rallying individuals against foreigners and minorities.

Left-wing populist movements, on the other hand tended to garner support based

on economic cleavages. They pointed to the wealthy and large corporations as

responsible for economic shocks. The ease of mobilization around these

cleavages depends on the salience of the issue for constituents. Individuals

who feel their jobs and public services have been threatened by immigrants and

minorities are easier to mobilize along ethno-national and cultural cleavages.

The cultural cleavages Rodrik describes are becoming

easier to exploit in areas impacted most by massive migrations and economic relocation

and divestment. Global warming has led to declining agricultural output, declining

peripheral state revenue to purchase the loyalties of competing local

constituencies, natural disasters, and the collapse of peripheral states

leading desperate people to flee local conflicts and poverty by seeking refuge

elsewhere. In the north, automation has led to unemployment among skilled and

unskilled workers (Grimes,1999). Right-wing politicians have been able to prey

on the fears of the economically insecure individuals in the Global North, who

see waves of migrants as threats to their social and economic way of life.

Comparing the Contemporary Global Right with

the Global Right in WR1917

The global right in WR1917 was

composed of reactionary conservatives still resisting the rise of centrist

liberalism and the remains of a few far-right sects that had emerged in the

late 19th century, especially during economic downturns. The fin de siècle intellectual climate was

tired of parliamentary debates and stalemates among contending parties.

Romanticism and transcendent ideologies were becoming more popular. Countries

that were new to mass politics had relatively weak regimes that could not

effectively deal with the problems caused by World War I or the problems that

came along with the global financial collapse of 1929. These crises were

opportunities for anarchists, socialists, communists and fascist sects to

become mass parties, especially in locations in which the left was becoming

powerful and threatening. The important

point here is that fascism was itself a popular movement at first and that it

was only later that it was supported by traditional agrarian and capitalist

elites who saw it as preferable to dispossession by communists. Michael Mann (2004: 21) contends that the

elites often overreacted to perceived threats to their interests from leftist

movements that were not actually powerful enough to dispossess them. But the

result was that fascist parties were embraced by some of the old conservatives

and were enabled to take state power in Italy and Germany. These, and the

militarist authoritarian regime in Japan, mounted a global challenge to liberal

capitalism from the right.

One feature common to the German,

Japanese, and Italian attempts to build domestic support was in their

respective efforts to create new empires.

The Germans sought to conquer Europe, the Italians sought colonies in Africa,

and the Japanese attempted to conquer all of East Asia

and the Pacific. The U.S. hegemony that emerged after World War II was justified

as a centralist liberal “free world” regime that had been formed in the

struggle against colonialism, communism, fascism and Japanese imperialism.

The second world war shows that fascists need enemies to attack,

but the internal and external enemies they chose varied depending on their

national and international context. Many

20th century fascists were anti-Semitic, yet Mussolini only accepted

anti-Semitism as a condition for his alliance with the Nazis. Nazism was racial, but Italian fascism was a

form of cultural hypernationalism that did not

require racial purity. The global right of the first half of the 20th

century also contained movements and regimes that were authoritarian, but not

fascist.

The difference between the two that matters here was described

by Goldfrank (1978). There he defined a truly fascist

regime as one emerging from, and expressing, a genuine popular movement from

below, in contrast to an authoritarian regime that is imposed upon the populace

by the elites. According to this distinction

the Vargas regime in Brazil and the Peron regime in Argentina were not fascist,

and nor was the militaristic authoritarian regime in Japan. These are instead better

understood to have been non-democratic coups from above in which state power was used to mobilize development,

expansion and resistance to the economic domination of the Great Powers in the

core (Goldfrank 1978). These were non-fascist, but

authoritarian statist responses to the crises of global capitalism and should

be considered to have been part of the global right. They sometimes made use of

fascist symbols and ideas, but they were not mainly based on ultranationalist

movements from below.

The contemporary global right is

composed of rather different reactionary groups. Jihadists (and Muslims in

general) are a favorite enemy of the neo-fascists who have announced that

sharia law will be enacted in the United States because decadent liberals and

multiculturalists are encouraging Muslims to take over. Jihadists attack

commercialized global youth culture, which they see as individualist,

consumerist and sexually immoral. The good news here is that the jihadists and

the neo-fascists are unlikely allies. So, the contemporary global right is far

from unified.

Neo-Fascist Movements

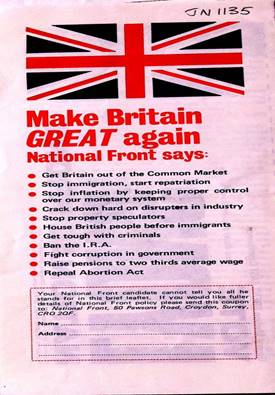

Most

neo-fascist movements do not simply regurgitate the rhetoric of the early 20th

century fascist movements. They are shaped by the contemporary socio-political-economic

context (Paxton 2004; Alvarez 2019)). Neo-fascist movements have not (yet) been

as violent, and nor have they glorified violence, as much their 20th

century predecessors. They are generally covert and adaptive, attempting to capture public

spaces. In the old days that meant

streets, villages and newspapers. In recent decades it has meant cheap rural television

and radio venues, the internet and online social networks.

Harris et al (2017) claim that the leadership

of neo-fascist movements relies on misdirection, and on their supporters’

comfort with alternative facts so that they can survive in a globalized economy

while pushing isolationist and racist agendas. As with the New Global Left,

they are a reaction to the neoliberal globalization project, but instead of

proposing an alternative form of democratic and multicultural globalization

they propose reactive nationalism, he-tooism, xenophobia,

protectionism and making x great again.

Paxton

(2004) recognized a series of events that presaged the growing popularity of contemporary

right-wing movements:

…ethnic cleansing

in the Balkans; the sharpening of exclusionary nationalisms in postcommunist eastern Europe; spreading ‘skinhead’ violence

against immigrants in Britain, Germany, Scandinavia, and Italy; the first

participation of a neofascist party in a European government in 1994, when the

Italian Alleanza Nazionale, direct descendant of the

principal Italian neofascist party, the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI), joined

the first government of Silvio Berlusconi; the entry of Jörg

Haider’s Freiheitspartei (Freedom Party), with its

winks of approval at Nazi veterans, into the Austrian government in February

2000; the astonishing arrival of the leader of the French far Right, Jean-Marie

Le Pen, in second place in the first round of the French presidential elections

in May 2002; and the meteoric rise of an anti-immigrant but nonconformist

outsider, Pym Fortuyn, in the Netherlands in the same month. Finally, a whole

universe of fragmented radical Right ‘grouplets’ proliferated, keeping alive a

great variety of far-Right themes and practices (2004:173)

Another difference between the

earlier and more recent versions of fascism is the attitude toward the national

state. Most of the earlier versions glorified the state as an instrument of the

purified nation. The realities of state control were more complicated in both

Italy and Germany, but at the level of ideology “statism”

was an important fascist value.

Contemporary neo-fascist movements do not glorify the state. They favor

more authoritarian and interventionist state actions, but they do not glorify

the state as such. This difference is one reason why some scholars prefer the

term “populist nationalism” over “neo-fascism.” Another important difference is

about military expansionism. Glorification of military expansionism was an

important part of both Italian and German fascism, Japanese authoritarianism,

Argentinian efforts to reclaim the Malvinas, and current Russian military

annexation of the portions of Ukraine required to access the strategic port of

Sevastopol. But no neo-fascist movement or party has endorsed such a policy, at

least so far. The decolonization of the

whole periphery and the establishment of international organizations such as

the United Nations that oppose conquests and support the sovereignty of member

states has effectively delegitimized formal colonialism. Clientelism and covert interventions continue

to be the main modes of exercising power in geopolitics. It is likely that neo-fascist

regimes would not hesitate to employ these, but a return to military conquest

seems unlikely.

Though many of the earlier fascist

movements embraced syndicalism and were anti-capitalist in their early phases,

most neo-fascists and right-wing populists now strongly support capitalism and

oppose state intervention into the economy (Hochschild 2016; Skocpol and

Williamson 2012).[14] This appears to be part

of a continuing reaction against the welfare state that was pioneered by the

rise of neoliberalism in 1970s and 1980s and continues to be an important theme

in right-wing populist and neo-fascist movements.

Pro-capitalist popular

authoritarianism, and even fascism, are experiencing growing popularity in some

Asian and Latin American countries. Docena (2018) cites

three inter-related crises as the catalyst for this growth—crises of neoliberal

capitalism, liberal democracy, and anti-systemic or leftist radical-democratic

movements. These conditions are found more in areas deeply penetrated by global

capitalism and where liberal-democratic elites have already replaced

dictatorships. These elites have continued the policies of their predecessors,

such as export-oriented development, loosened business restrictions, attacks on

labor, reduced social spending, and stalled redistribution. As unemployment and

poverty increase, people see symbols of unattainable wealth spring up around

them in the form of shopping malls and luxury condominiums. In response to the

ineffective leftist anti-systemic movements and perceived corruption of the Pink

Tide populist regimes, the people in these areas are turning towards an

authoritarian solution as opposed to an anti-elite, anti-neoliberal response.

Reactions to Globalization and the Future of

the Global Right

At present an “interlocking

set of new enemies” is are seen as tearing at the status quo, including

“globalization, foreigners, multiculturalism, environmental regulation, high

taxes, and the incompetent politicians” (Paxton 2004: 181). The neoliberal globalization project has led

to a transformation of the world economy, thereby providing “a new fertile

terrain for far-right mobilizations” (Saull 2013:

631). The fragmented, insecure precariat no longer gathers in membership-based

collective organizations (Standing 2011). A globalized economy provides

opportunities to blame immigrant labor, finance capital, foreign investment,

labor-outsourcing, and ineffective politicians for local economic dislocations

(Saull 2013).

Spektorowski (2016) claims

that racial ethno-regionalism is supplanting nationalism in the global

political-economy. He argues that post-national European fascism may be the

next stage in the evolution of fascism in transnational regions with a focus on

preserving an “ethnic federation of European people” in the form of a “strong,

dominant, and productive conglomeration” (Spektorowski

2016: 126). But this vision of transnational racial struggle is undermined by

the rise of hypernationalism.

Classical

fascist rhetoric claimed to transcend class struggle (Mann 2004). But a divide now

exists between those qualified for open sector, internationally competitive

jobs and those stuck in sectors that are unable to compete globally (Kriesi et al

2006). Globally-minded liberals and progressives have become the enemy of

locally-focused traditionalists (Hochschild 2016). Individuals can only vote in

their local and national elections. The European Parliament is a partial

exception, but international organizations such the United Nations are lacking

in their institutional ability to directly represent citizens (Monbiot 2003).

New Right movements seek to demonize

characteristics of centrist liberalism such as “materialism, individualism, the

universality of human rights, egalitarianism and multiculturalism” (Griffin

2004: 295). These movements claim to restore the primacy and purity of

ethno-national groups, now threatened by globalization and immigration. The

immigration issue is not likely to go away soon. Population continues to grow

in eight countries in the Global South in which prospects for economic

development and job growth are bleak. The peak wave of 2015 has receded, but

economic forces, political disruptions, and civil wars are likely to continue

to make South/North immigration a contentious issue for the next few decades

(Mason 2015).

Western Europeans and Americans have known

mostly “peace, prosperity, functioning democracy, and domestic order” (Paxton

2004: 187) since World War II. Right-wing populist politicians who are trying

to build a mass movement usually distance themselves from the political

violence of their most ardent supporters.[15] The neo-fascist fringe groups do use forceful

confrontation as a tactic and this is reminiscent of the fascists of the 20th

century, but, at least so far, lethal violence appears to have been restricted

to mentally challenged individuals inspired by the rhetoric of others.

Some neo-fascist organized actions have

displayed considerable political savvy in framing and coordinating their street

tactics. The demonstrations against “sharia law” claimed that it legalizes

female genital mutilation, thereby attempting to mobilize women and feminists

to support anti-Moslem and anti-immigrant causes.

The energy that some neo-fascist

groups have shown and the apparent rapid spread of authoritarian rightist

populism and neofascist movements across the globe is disturbing. The currently

low unemployment rate, the revival of housing construction and the real estate

market and the Trump-induced stock market bump slowed these movements down. But

a new financial crisis and/or an economic slowdown will increase the level of

frustration and support for these neo-fascist sects and movements. This,

combined with a global ecological crisis, could lead to the “perfect storm”

theorized by Glenn Kuecker (2007).

Conclusions and Speculations

This project is yet incomplete. Our

effort to reconstruct the constellation of right wing

reactionary movements that were players in the World Revolution of 1917 needs more

work. We surmised that religious

fundamentalism was not as big a force in but this

issue needs more thought and historical study for purposes of comparing 20th

and 21st centuries global rights. We also see a need to look more

closely at the issue of fascist international coordination and organization

both in the first half of the 20th century and in the late 20th

and early 21st centuries. And we are also interested in the role of finance

capital in the rise of fascism in the 20th century and its potential

involvement in the 21st century. Because the story is unfolding before

our eyes, our efforts to characterize the nature of 21st century neo-fascism

and its similarities and differences with earlier incarnations remains provisional,

but our characterization of similarities and differences suggest what to keep

an eye on. An ironic hypothesis is suggested by our comparisons so far. Fascism

in the Age of Extremes [the first half of the 20th century] was

importantly a reaction against the strength of the rising international labor

movement and socialist, anarchist, and communist organizations that were

promoting proletarian internationalism and threatening the property of the rich.

Now the Left is decidedly weak, but it might gain new strength and more

articulation and organization in response to the threat posed by 21st

century neo-fascism. Something like this occurred in the 1930s when anarchists,

socialists, and communists were driven to organize united fronts to combat

fascism. A democratic eco-socialist

movement network with an articulated global organizational instrument might yet

emerge to take up the job of confronting the rise of neo-fascism (Amin 2018). Regarding

the future of fascism, our observation that fascism has come in waves and what

we said about the co-evolution of tributary modes, capitalism, and socialism

implies that new forms of fascism and authoritarianism are likely to emerge in

the 21st and 22nd centuries as humanity struggles to

implement a sustainable and humane form of global society.

Bibliography

Aldecoa, John, C.

Chase-Dunn, Ian Breckenridge-Jackson and Joel Herrera 2019 “Anarchism in the

Web of Transnational Social Movements” Journal of World-Systems Research.

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows107/irows107.htm

Almeida, Paul and C. Chase-Dunn 2018 “Globalization and social

movements” Annual Review of Sociology Vol.

44:1.1–1.23 https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041307

Almeida, Paul and C. Chase-Dunn 2019 Global Change and Social Movements Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Alvarez,

Rebecca 2019 “Fascism,

Masculinism, and the Alt-Right Appeal to Status Anxiety”

Canadian Review of Sociology

Amin, Samir 2018 “Letter of Intent for an Inaugural Meeting of the

International of Workers and

Peoples” IDEAs network, July 3 http://www.networkideas.org/featured-articles/2018/07/it-is-imperative-to-reconstruct-the-internationale-of-workers-and-peoples/

Anderson, Perry 2005 Spectrum. New York: Verso

Arrighi,

Giovanni 1994. The Long Twentieth Century.

Arrighi, Giovanni 2006. Adam Smith in Beijing. London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K. Hopkins and

Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic

Movements. London and New York: Verso.

Beck, Colin J. 2011 “The world cultural

origins of revolutionary waves: five centuries of

European

contestation. Social Science History 35,2: 167-207.

Bond, Patrick 2012 The Politics

of Climate Justice: Paralysis Above, Movement

Below Durban, SA: University of Kwa-zulu Natal Press

___________ (ed.) 2013 Brics in

Africa: anti-imperialist, sub-imperialist of inbetween? Centre

for Civil Society, University of Kwa-Zulu-Natal.

Boswell, Terry and Christopher Chase-Dunn.

2000 The Spiral of Capitalism and

Socialism: Toward Global Democracy. Boulder, CO.: Lynne Rienner.

Braudel, Fernand. 1984 Civilization and Capitalism, 15th - 18th Century. Vol.

3: The Perspectives of the World.

New York: Harper and Row.

Carroll, William K.

2016. Expose, Oppose, Propose: Alternative Policy Groups and the

Struggle for Global Justice. New York: Zed.

Chase-Dunn, C. 2016 “Social Movements and

Collective Behavior in Premodern polities” IROWS Working Paper #110 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows110/irows110.htm

Chase-Dunn, C and

Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise:

Comparing World-Systems

Chase-Dunn, C, and Ellen Reese 2007

“The World Social Forum: a global party in the making?” Pp. 53-92 in Katrina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila

(eds.) Global Political Parties, London: Zed Press.

______________ Alessandro Morosin and Alexis Álvarez 2015 “Social Movements and

Progressive

Regimes in Latin

America: World Revolutions and Semiperipheral

Development” Pp,. 13-

24 in Paul

Almeida and Allen Cordero Ulate (eds.) Handbook

of Social Movements across Latin

America, Dordrecht, NL: Springer

Chase-Dunn, C. and R.E. Niemeyer

2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” Pp. 35-57 in Mathias Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational Political

Spaces. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/New York

Chase-Dunn

C. and Matheu Kaneshiro 2009 “Stability and Change in the contours of

Alliances

Among movements in the social forum process” Pp. 119-133 in David

Fasenfest (ed.) Engaging Social Justice. Leiden:

Brill.

Chase-Dunn, Chris, Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence

and Hiroko Inoue 2011 “Last of the hegemons: U.S. decline and global

governance” International Review of Modern Sociology 37,1: 1-29 (Spring).

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Bruce Lerro 2016 Social Change : Globalization from the Stone

Age to the Present. New York: Routledge

Chase-Dunn C. and Nico Pascal 2014

“Articulation in the Web of Transnational Social

Movements” global-e: a global studies

journal. Volume 8, Issue 3 (April)http://global-ejournal.org/2014/04/30/vol8iss3/ see also IROWS

Working Paper #84 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows84/irows84.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. James Fenelon, Thomas D. Hall, Ian

Breckenridge-Jackson and Joel

Herrera 2019 “Global Indigenism and the Web of

Transnational Social Movements”

in

Ino Rossi (ed.) New Frontiers of Globalization Research: Theories, Globalization

Processes,

and Perspectives from the

Global South Springer Verlag. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows87/irows87.htm

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Rebecca Àlvarez Forthcoming “Forging an Organizational Instrument

for the Global Left:

The Vessel” A paper presented at the conference on "Economic

Development

and Democracy: What to Expect from the World-System in the 21st

Century?" at the 12th Edition, the Brazilian

Colloquium on Political Economy of the World-System, Federal University of

Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brasil, August 27-28, 2018. IROWS Working

Paper #130 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows130/irows130.htm

Claudin, Fernando. 1975 The Communist Movement: From Comintern To Cominform. (2 vols.) Monthly Review Press.

N.Y.

Davis, Mike

2018 Old Gods, New Enigmas: Marx’s Lost

Theory. London: Verso

de Sousa Santos, Boaventura 2006 The

Rise of the Global Left. London: Zed Press.

Docena, Herbert. 2018. The Rise of

Populist Authoritarianisms in Asia: Challenges for Peoples’ Movements. Bangkok, Thailand: Focus on the Global

South. Retrieved February 3, 2018. the_rise_of_populist_authoritarianisms_in_asia-revised._final.pdf.

Dubois, Laurent 2004 Avengers

of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution

Cambridge: Belnap Press of Harvard

Griffin, Roger 1993 The

Nature of Fascism. London: Routledge

___________ 2004 “Fascism’s new faces (and

new facelessness) in the ‘post-fascist’ epoch” Erwagen, Wissen, Ethik,

15, 3, 287-300

Goldfrank, Walter .L. 1978

“Fascism and world economy” Pp. 75-120 in Barbara Hockey Kaplan (ed.) Social Change in the Capitalist World

Economy. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

________________ 1990 “Fascism and the

great transformation” Pp. 87-92 in Kari Levitt Polanyi (ed.) The Life and Work of Karl Polanyi.

Montreal: Black Rose Books.

Goldstone,

Jack. 1991. Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World.

Berkeley: University of California Press

_______________2014 Revolutions.

New York: Oxford University Press

Gordon, Linda 2017 The Second Coming of the KKK. New York: Norton

Gorski, Philip. 2017. “Why evangelicals

voted for Trump: A critical cultural sociology.” American Journal of

Cultural Sociology 5(3):338-354.

Grimes, Peter 1999. “The Horsemen and the

Killing Fields: The Final Contradiction of Capitalism.” Chapter 2 of Goldfrank, Walter; David Goodman, and Andrew Szasz (eds.) Ecology and the World-System. Greenwood Press,Westport, Conn.

Grimes, Peter 2003 “Sociologist of Energy:

Howard Ehrlich interviews Peter Grimes” Social

Anarchism: A

Journal of Theory and Practice Number 34, pp. 37-50 ISSN: 0196-4801

Harris,

Jerry, Carl Davidson, Bill Fletcher Jr., and Paul Harris 2017 “Trump and

American Fascism” International Critical

Thought.

Hochschild, Arlie R. 2016 Strangers in Their Own Land. New York:

New Press.

Hung, Ho-Fung 2011 Protest with Chinese Characteristics:

Demonstrations, Riots and Petitions in the Mid-

Qing Dynasty. New York: Columbia

University Press

Kaldor, Mary 2003 Global Civil Society. Malden,

MA: Polity Press

Kuecker, Glen 2007 “The perfect storm” International

Journal of Environmental, Cultural and

Social

Sustainability 3,5: 1-10. https://scholarship.depauw.edu/hist_facpubs/3/

Kirk, Ashley and Patrick Scott 2017

“French election results: the maps and charts that explain how Macron beat Le

Pen to become President” The Telegraph

May 8, 2017 Retrieved Jul. 22, 2017 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/0/french-election-results-analysis/

Klein, Naomi. 2017. No Is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the

World We Need. Chicago, IL: Random House Group Ltd.

Kriesi, Hans Peter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martine Dolezal, Simon Bornschier

and

Timitheos Frey. 2006. “Globalization and the transformation

of the national political space: European countries compared” European Journal of Political Research

45, 921-956

Laqueur, Walter Z.(ed.) 1976. Fascism: a reader’s guide Berkeley:

University of California Press

_____________ and George L. Mosse

(eds.) 1966 International Fascism,

1920-1945. New York: Harper and Row

Linebaugh,

Peter and Markus Rediker. 2000. The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners and the Hidden

History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon.

Mann, Michael 2004 Fascists. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Mason, Paul 2015 Postcapitalism

New York: Farrer, Straus and Giroux

Meyer, John W.

2009 World Society. Edited by Georg Krukcken

and Gili S. Drori. New

York:

Oxford University Press.

Minkowitz, Donna 2017 “The Racist Right Looks Left.” The Nation, December 8.

Moghadam, Valentine M. 2009. Globalization

and Social Movements: Islamism, Feminism and the Global Justice Movement. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Monbiot, George 2003 Manifesto for

a New World Order. New York: New Press.

Nagy, Sandor.

2017 "Global

Swings of the Political Spectrum since 1789: Cyclically Delayed

Mirror Waves of Revolutions

and Counterrevolutions" IROWS Working

Paper #124 at http://irows.urc.edu/papers/irows124/irows124.htm

Paxton, Robert O. 2004 The Anatomy of Fascism. New York:

Vintage Books (Random House).

Podobnik, Bruce 2006 Global Energy

Shifts: Fostering Sustainability in a Turbulent Age.

Philadelphia,

PA: Temple University Press.

Polletta, Francesca and Jessica Callahan. 2017.

“Deep stories, nostalgia narratives, and fake news: Storytelling in the Trump

era.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology doi: 10.1057/s41290-017-0037-7.

Reese, Ellen, C. Chase-Dunn, Kadambari Anantram, Gary

Coyne, Matheu Kaneshiro,

Rodrik, Dani.

2018. “Populism and the Economics of Globalization.” Journal of International Business Policy DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-001-4

Sanderson, Stephen K. 1995 Social Transformations London: Basil

Blackwell.

Saull, Richard G. 2013

“Capitalist

Development and the Rise and ‘Fall’ of the Far-Right” Critical Sociology Vol 41,

Issue 4-5, 2015.

_____________Alexander Anievas, Neil Davidson, Adam Fabry (eds.) 2015. The Longue Durée of the Far Right. London: Routledge.

Skocpol, Theda and Vanessa Williamson 2012 The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican

Conservatism.

Oxford University Press.

Smith, Jackie, Marina Karides, Marc Becker, Dorval Brunelle, Christopher

Chase-Dunn,

Donatella della Porta, Rosalba Icaza Garza, Jeffrey S.

Juris, Lorenzo Mosca, Ellen Reese,

Peter

Jay Smith and Rolando Vazquez 2014 Global Democracy and the World

Social Forums. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers; Revised 2nd edition.

Spektorowski, Alberto. (2016). Fascism and post-national europe: Drieu la rochelle and alain de benoist. Theory,

Culture & Society, 33(1), 115-138.

Standing, Guy. 2011. The Precariat:

The New Dangerous Class. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Steger, Manfred, James

Goodman and Erin K. Wilson 2013 Justice

Globalism: Ideology, Crises, Policy. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984

“The three instances of hegemony in the history of the

capitalist

world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current

Issues and

Research

in Macrosociology, International Studies

in Sociology and Social Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2011a [1974]. The

Modern World-System, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press.

__________ 2012 The Modern World-System, Volume

4 “The triumph of centrist

liberalism” Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel 2017 “The Political

Construction of Islam” Chapter 8, Pp. 125-140 in Immanuel Wallerstein 2017 The World-System and Africa. New York: Diasporic Africa Press.

Whiteneck, Daniel 1996 “The Industrial Revolution

and Birth of the Anti-Mercantilist Idea: Epistemic Communities and Global

Leadership” Journal of World-Systems

Research Vol 2, Issue 2. https://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/jwsr/article/view/69/81

Whittier,

Nancy. 2014. “Rethinking Coalitions: Anti-Pornography Feminists, Conservatives,

and Relationships between Collaborative Adversarial Movements.” Social

Problems 61(2):175-193.

Zuquete, Jose Pedro and Charles Lindblom 2009 The Struggle for the World. Palo

Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.