Global Political

Sociology and World-Systems

V 2-11-18 6996

words

Sakin Erin

and Christopher Chase-Dunn

A chapter in the Cambridge New Handbook of Political Sociology edited by Cedric de Leon, Thomas Janoski, Isaac Martin and

Joya Misra

Irows Working Paper #120 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows120/irows120.htm

Thanks to Catherine Desroches for translating this

article into Latvian. Her translation is at https://www.

Abstract: The new global

political sociology is a response to the growing awareness that humans have

constructed an Earth-wide polity along with the global economic system. The

disciplinary boundaries among the social scientists, especially between

anthropology, sociology, political science, history and economics are

formidable to the effort to comprehend and to explain global social change and

world history. The world-systems perspective is a useful framework for global

political sociology and for explaining political, economic and cultural

globalization and the evolution of global governance. We discuss the main conceptual issues and we

review those studies that have utilized formal network analysis for studying

the world-system.

World-systems analysis is a holistic

and critical social science approach that proposes the study of social change

focusing on whole systemic human interaction networks. The general theoretical

approach is based on institutional materialism that is inspired by classical

sociology and anthropology (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2016).[1] The

world-system perspective emerged in the 1960s and 1970s to explicate the nature

of the core/periphery hierarchy over the last five centuries. Its originators

were Immanuel Wallerstein, Samir Amin, Andre Gunder Frank and Giovanni Arrighi

(Amin 1980a; Frank 1966, 1967 1969; Arrighi 1994; Wallerstein 2011[1974]).

Wallerstein (2000:74) says:

We

take the defining characteristic of a social system to be the existence within

it of a division of labor, such that the various sectors or areas are dependent

upon economic exchange with others for the smooth and continuous provisioning

of the needs of the area.

According to Wallerstein’s formulation,

whole historical social systems are clusters of individuals, organizations and

polities that are systemically interconnected with one another. These interaction networks have not always

been global (Earth-wide). In the past, when transportation and communications

technologies were less developed, world-systems were smaller (Wallerstein

2000:75-6). What makes a whole system is not the amount of space it encompasses

but rather the degree of interconnectedness such that what happens in one place

has large consequences for what happens in another place (see also Tilly 1984).

When transportation and communication technologies limit long-distance

interactions the consequences of events fall off with distance, and so whole

systems are smaller. Only with the development of the capitalist world-economy

did the modern world-system become global. A hierarchical division of labor

emerged linking the European core states with their colonial empires in Africa,

Asia, Oceania and the Americas. This global division of labor has been

politically organized as a system of fighting and allying sovereign states in

the core and a set of colonial empires. Waves of decolonization since the

eighteenth century extended the system of theoretically sovereign states to the

non-core. In global political sociology the state is understood as an

organization that claims jurisdiction over a territory. Nations are a form of

collective identity or a solidarity similar in form to ethnicities, clans, and

lineages. Nationalism refers to the sentiments and beliefs that constitute and

reinforce a nation.

One

Logic or Four?

Global

political sociology recapitulates a long-standing debate between historians and

social scientists regarding the advantages and dangers of emphasizing either

systemic structures, on the one hand, versus particularity, uniqueness and

conjunctural complexity on the other. Focusing on the global does not resolve

this debate on way or the other, but a reasonable compromise can be based on

the recognition that some aspects of human social change are, indeed, open-ended

and conjunctural whereas other aspects are more systemic, structural and

predictable.[2]

Among the systemists there continue

to be debates about the nature of systemic logics and how they may or may not have

changed over time. Realist international relations theorists assume the

existence of a timeless geopolitical power logic in which competing states try

to conquer one another or keep from being conquered. Formalist economists see a

timeless logic of competition among rational individuals to acquire valuables.

Evolutionary Marxists see transformations of systemic logics based on normative

integration constructed as kinship to institutionalized coercion in the

tributary (state-based) modes of accumulation to capitalist accumulation based

on the acquisition of profits from commodity production and financial

transactions. World-system analysts have argued that underlying logic of the

modern global system combines the geopolitics of the interstate system with the

logic of capitalist accumulation (Chase-Dunn 1998: Chapter 7).[3]

This formulation is based on the idea that the multipolar interstate system and

the capitalist world-economy reproduce one another. The international migration

of capital prevents world empire (global state formation) and nationalism and

the system of competing states undercut political movements that challenge the

rule of capital.

Michael Mann (2016) contends that

many important sociocultural developments that have shaped world history and

prehistory have been conjectural accidents that are not predictable by theories

of sociocultural evolution, though he admits that some developments are best

understood as evolutionary (list both kinds in footnote). Mann’s work on modern

social change 1986; 2004) applies his Weberian schema in which four

institutional realms develop somewhat separately, with occasional important

interactions with one another. The four realms are economics, politics, the

military and ideology. Mann explicitly

denies that there is a single modern global system and his critiques of those

he calls “hyperglobalists” are often trenchant. He prefers to describe the

major institutional changes occurring in his four reams separately to produce

his world historical narrative. His work is a valuable structural account of

modern world history despite his refusal to see a systemic logic operating at

the level of the whole world-system.

Core/Periphery

Hierarchies

The idea that there are system-wide

socially structured hierarchies in whole world-systems is a central notion for

world-systems analysis. The comparative and evolutionary version developed by

Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) makes the issue of the existence or non-existence of

a core/periphery hierarchy an empirical issue for each system based on the

finding that some small-scale systems had very mild forms of core/periphery

hierarchy (Chase-Dunn and Mann 199x). The

modern core is composed of a number of internally and externally strong states

that are home to the headquarters of global firms and that have economies based

on capital-intensive production using highly skilled labor. The contemporary

core states are in Western Europe, North America and include Japan. The

periphery consists of states that are internally and externally weak in which

production consists of agricultural and mineral raw material exports and

low-productivity agriculture. The periphery is composed of former colonies in

Asia, Africa and Latin America. The semiperiphery is composed of two different

kinds of states: small states with middle levels of development (e.g. South

Korea, Israel; South Africa, Taiwan, etc.), and large states that include both

developed and little-developed regions (e.g. China, India, Indonesia, Mexico,

Brazil, Argentina, Russia, etc.). There

have always been hierarchical global commodity chains linking production

processes into the transnational hierarchical division of labor that

constitutes the core/periphery structure (Wallerstein and Hopkins 2000).

The institutional basis and nature

of core/periphery relations change over time, but they are always a mix of

institutionalized political coercion and economic comparative advantages that

undergird unequal exchange in which the core extracts resources from the

non-core. Tributary empires extracted taxes and tribute from conquered

territories and subaltern polities. Capitalist core states have obtained

favorable terms of trade from formal colonialism and then from

semimonopolization of products in which they have a comparative advantage and

from foreign investment and financial centrality. The neo-colonial

core/periphery hierarchy which has emerged following decolonization combines

interstate clientelism with foreign investment and financial services to

extract profits from the non-core. Technological rents and international

financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and global banks

are increasingly relied upon.

The Modern System

The modern world-system emerged in

Europe and its colonies in the long 16th century between 1450 and

1640 CE (Wallerstein 2011). Though capitalism in many forms had existed since

the Bronze Age, the modern system was the first whole network in which the

capitalist mode of accumulation became predominant. The endless accumulation of

capital, which is the primary principle around which capitalist accumulation is

organized (Arrighi 1994), requires a world-economy that is based on

exploitation, monopolization and unequal exchange. Military, political, and

cultural forms of organization are used to successfully accumulate capital in a

competitive and hierarchical system. In the fifteenth century Genoa and

Portugal made an alliance based on this logic of accumulation that resulting in

the emergence of the Europe-centered world-system (Arrighi 1994). The United

Provinces of the Netherlands followed suit in the seventeenth century, emerging

as a far reaching capitalist nation-state that joined characteristics of

earlier capitalist city-states in a federal structure that facilitated the

invention of joint stock companies, a stock exchange and a far reaching

colonial empire based on profit-taking rather than tribute or taxation

(Wallerstein 1984). A great struggle for global domination between the British

and the French in the 18th century eventuated in the 19th

century hegemony of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, which was then

followed, after another period of interimperial rivalry, by the 20th

century hegemony of the United States.

According

to Wallerstein, the modern world-system is different from earlier world-empires

such as ancient Rome and China because no single state has conquered the whole

world-economy and transformed into a world-empire. Instead, the core has

remained organized as group of competing states in which hegemons have risen

and fallen but no single state has taken over the whole system. The global

capitalist class expanded their trade networks in search for much needed labor

and raw materials, which led to the colonization of most of the rest of the

world by Europeans. The modern world-system is structured as an hierarchical

international division of labor that consists of three zones: the core, the

semiperiphery, and the periphery. Andre Gunder Frank (1966) developed the idea

of “the development of underdevelopment” to explain the reproduction of the

core/periphery hierarchy. The periphery and the semiperiphery provide raw

materials and cheap labor for the expanding production of the system, while at

the same time it functions as a marketplace for the commodities produced in the

core zone. The semiperiphery is a buffer zone between the core and periphery

preventing the bifurcation of the system. Immanuel Wallerstein (2000) contends

that the semiperiphery is essential for assuring the political stability of the

system. The core/periphery hierarchy is one of the most important structures of

the current world-system. In the modern world-system this structure has been

reproduced over centuries despite upward and downward mobility of a few

national societies. The basis of power in the current system is the

concentration of innovations in new lead industries and in military and

organizational technologies that affect the relative power and capacities of

firms and states.

State-Centrism

and Core/Periphery Hierarchy

Core/periphery hierarchies have

always been organized class structures as well as interpolity relations.

Classes have been both regionally nested within national societies and

transnational. Samir Amin (1980) produced a structural analysis of global classes

long before the global capitalism hyperglobalists discovered the transnational

capitalist and working classes. And the

core/periphery hierarchy is not just a tripartite stack of zones that contain

states. There has always been a system-wide class structure in which both

national and transnational class relations were important. There have been

system-wide class structures in world-systems since the evolutionary emergence

of class relations in complex chiefdoms. The theorists of a global stage of

capitalism have disparaged the “state-centrism” of world-systems analysis along

with other social theorists and observers that continue to see a world of

disconnected national societies. The world-systems theorists were among the

first to challenge the state-centric analysis of separate national societies as

if each were on the moon. In the world-systems perspective polities (including

states) are not all-encompassing and disconnected whole social systems. The

state is an organization in field of social interactions that include other

states and all the transnational interactions that cross state boundaries.

Sovereignty is a legal theory about jurisdiction, not a true description of

autonomous existence. State policies differ with respect to their efforts to

attain autonomy, but all states in the system, including the core states, are

heavily influenced by processes that are occurring in the larger system. The

global class structure is intertwined with the interstate system, such that

workers in the core states have a rather different relationship capital than do

workers in the non-core. And this changes over time as the class struggle

interacts with core/periphery relations. The primary sector of core workers

were able to become included in the Keynesian developmental project after World

War II but were “peripheralized” back into the precariat with the rise of the

neoliberal globalization project.

National and transnational class relations have been and continue to be

important for understanding the evolution of global capitalism (Robinson

2014).

The evolution of global governance: political globalization

Although

the world-system perspective emerged to comprehend the Europe-centered modern

world-system since the sixteenth century CE, some scholars have expanded the

theory to examine continuities with earlier periods (e.g. Frank and Gills 1993)

or to compare the modern system with earlier regional systems (Chase-Dunn and

Hall 1997). These have interacted with theorists of global capitalism and

international relations theory in political science to produce a new political

sociology of world-systems that examines the evolution of world politics in the

context of political and economic globalization.

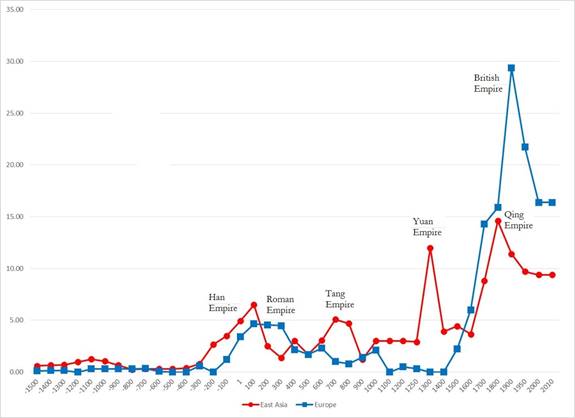

As anthropologists and world historians

have long noted, the scale and complexity of political organization has

increased over the long run, albeit in waves. Figure 1 shows the territorial

sizes of the largest polities in Europe and East Asia between 1500 BCE and 2010

CE.

Figure 1: Territorial Sizes of largest polities in Europe and East Asia (square megameters):

1500 BCE- 2010CE (Source

Chase-Dunn et al 2015, Figure 6)

The recent decline in the sizes of the largest

polities is due to the decolonization of the colonial empires, the demise

traditional territorial empires, and the extension of the interstate system to

the non-core. But the sizes of the modern hegemons have continued to increase

(from the Dutch to the British to the U.S. hegemony, and so the long-term trend

toward eventual global state formation has continued. The current decline of

U.S. hegemony indicates the emergence of a new multipolar inter-regnum that

will likely be followed by the rise of a new hegemon or global state formation.

The new political sociology needs to comprehend the long-term

trends as well as recent developments in the evolution of the global polity.

The modern world-system is somewhat similar to earlier regional world-systems

in that there is a cycle of the rise and fall of powerful polities. The

existing system of global governance is based on a mixture of institutions that

developed within formerly separate regional international systems. In the 19th century

the European international system merged with the system that had long existed

in East Asia (Arrighi, Hamashita and Selden 2003; Chase-Dunn and Hall

2011). The European Westphalian interstate system surrounded and

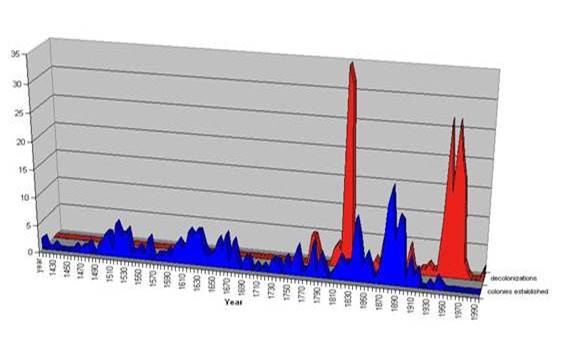

engulfed the trade-tribute system of East Asia (Arrighi 2006). In the 20th century

the last great wave of decolonization extended the system of sovereign national

states to the rest of the non-core (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Waves of colonization and decolonization, 1415-1995 CE (Source: Henige 1970)

Thus did the system of colonial empires that had been a major

structure of global governance since the rise of the West come to an end. But the

institutional means by which core countries could dominate and exploit non-core

countries did not end. Colonial structures were replaced by neocolonial

institutions such as financial indebtedness and foreign direct investment. This

neocolonial regime was organized after World War II around international

institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and what

became the World Trade Organization. But the rise and fall of hegemonies that

had long been a characteristic of the European system (Wallerstein 1984;

Arrighi 1994) continued as the major structural basis of global governance. The

British hegemony declined and the U.S. hegemony rose.

The rise and fall of hegemons intermittently supplies global

regulation for the world-system, but the method of choosing leadership has been

by means of a contest in which the winners of global wars become the hegemons.

This is a form of leadership selection that humanity can no longer afford

because of the development of weapons of mass destruction.

There was also a continuation of a trend that had begun with the

Concert of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars – the emergence of both general and

specialized international political organizations that began the formation of a

world state. The League of Nations was followed by the

more substantial United Nations (U.N.).

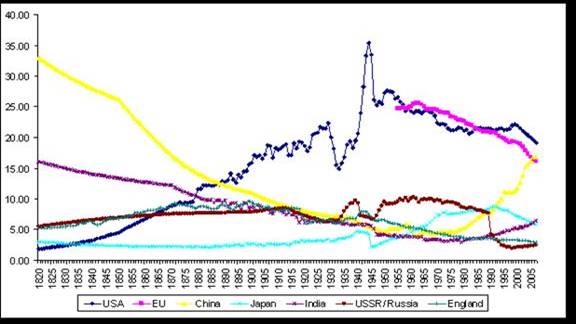

The long-term trends over the past two centuries have included the

extension of national sovereignty to the Global South because of the

decolonization movements (Figure 2 above), the growing size of the hegemon in

the transition from the British to the U.S. hegemony (Figure 3 below;

Chase-Dunn, Kwon, Lawrence and Inoue 2011) and the emergence of still-weak

but strengthening global-level political institutions. This has been

a long-term process of political globalization in which global

governance is becoming more centralized and more capacious because of the

increasing relative size of the hegemon and the emergence of global proto-state

organizations. Of course, there have also been counter-movements and periods in

which the long-term trends reversed. We are in such a period now because U.S.

hegemony is in decline[1] (Wallerstein

2003; Chase-Dunn, Kwon, Lawrence and Inoue 2011; Friedman 2017) and

support for the United Nations is also in decline because the U.S. has been its

main supporter.

The current period is

similar in many important ways to the period just before the outbreak of World

War I. The hegemon is in decline and powerful potential challengers are

emerging. In all earlier periods of this sort a World War among the contenders

has settled the issue of who should be the next hegemon (Chase-Dunn and

Podobnik 1995). We can no longer afford to use this primitive form

of leadership selection because a war among core states using weapons of mass

destruction would probably be suicidal for humanity. Thus the system

of global governance must evolve an effective mechanism for managing uneven

development and interstate conflicts without resort to major

wars. No single state is large enough to replace the United

States in the role of hegemon. The system is moving toward a multipolar

structure in which the U.S. hegemony is slowly declining and challengers are

rising. In the past this has been a prelude to world war. What is

needed to prevent violent interimperial rivalry is a structure of global

governance that can effectively resolve future conflicts without resort to

violence (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2008; Chase-Dunn and Inoue 2010).

But

there are also several important differences between the current period and the

period of decline of the British hegemony. Britain was never as economically

large relative to the size of the whole world economy as the United States has

been (see Figure 3). And Britain never had such a preponderance of military

power. Even at the height of British hegemony there were other core states that

had significant military power. Giovanni Arrighi (2006) noted that the period

of British hegemonic decline (1870-1914) moved rather quickly toward

conflictive interimperial rivalry because economic competitors such as Germany

and Japan could develop powerful military capabilities that were used to

challenge the British. The U.S. hegemony has been different in

that the United States ended up as the single superpower after the demise of

the Soviet Union. Some economic challengers (Japan and Germany) cannot easily

play the military card because they are stuck with the consequences of having lost

the last World War. This, and the immense size of the U.S. economy, will

probably slow the process of hegemonic decline down compared to the rate of the

British decline.

And the decline of Britain took place during the transition from

the coal energy regime to the oil energy regime (Podobnik 2006), whereas U.S.

decline is occurring as the world approaches its peak production of fossil

fuels and when global climate change is threatening to disrupt the

world-system. These developments parallel, to some extent, what happened a

century ago, but the likelihood of another “Age of Extremes” (Hobsbawm 1994) or

a Malthusian correction such what occurred in the first half of the 20th

century could be exacerbated by some new twists. The number of people on Earth

was only 1.65 billion when the 20th century began, whereas at

the beginning of the 21st century there were 6 billion.

Moreover, fossil fuels were becoming less expensive as oil was replacing coal

as the major source of energy. It was this use of inexpensive, but

non-renewable, fossil energy that made the geometric expansion and

industrialization of humanity possible.

Now we are facing global warming as a consequence of the spread

and rapid expansion of industrial production and energy-intensive consumption.

Energy prices have temporarily come down because of fracking and overproduction

by countries that are dependent on oil exports, but the low hanging “ancient

sunlight” in coal and oil has been picked. “Peak oil” is

approaching. “Clean coal” and controllable nuclear fusion remain

dreams. The cost of energy will probably go up no matter how much is invested

in new kinds of energy production.[3] None

of the existing alternative technologies offer low cost energy of the kind that

made the huge expansion possible. Many believe that overshoot has already

occurred in terms of how many humans are alive, and how much energy is being

used by some of them, especially those in the core. Adjusting to rising energy

costs and dealing with the environmental degradation caused by industrial

society will be difficult, and the longer it takes the harder it will become.

Ecological problems are not new, but this time they are on a global scale. Peak

oil and rising costs of other resources are likely to cause more resource wars

that exacerbate the problems of global governance. The war in Iraq was both an

instance of imperial over-reach and a resource war because the U.S.

neoconservatives thought that they could prolong U.S. hegemony by controlling

the global oil supply. The Paris Agreement on greenhouse gas

emissions reached in December of 2015 is good news, but compliance will be

difficult, especially for non-core countries and the Trump administration is

threatening to ignore global warming.

And the British government still had a colonial empire that it

could tax in order to support its military position whereas the shift from

colonialism to clientelism (Go 2011) means that the U.S. can only legally tax

its own citizens to support its global military preponderance. This may be seen

a progress, but it is also a factor that is likely to result in the decline of

the currently stable structure of global military power.

Political globalization and the rise and fall of hegemons have

been driven, in part, by a series of world revolutions – periods in which

social movements, rebellions and revolutions within countries – have clustered

in time. We have studied the emergence of the New Global Left and

now are giving attention to the nature of the New Global Right. The world

revolution of 1917 included the Russian, Mexican and Chinese revolutions and

the rise of organized social movements based on the labor movement and anti-imperialism.

During the 1920s and the 1930s – the “age of extremes” -- fascist

movements emerged in many countries.

Figure 3:

Shares of World GDP (PPP), 1820-2006 CE [Source: Chase-Dunn, Kwon, Lawrence and

Inoue 2011]

The New

Global Right (NGR), like the New Global Left (NGL), is a complex conglomeration

of movements. Radical Islam harkens back to a mythical golden age of god-given

law in reaction to the perceived decadence of capitalist modernity.

Neo-conservatives advocate the use of U.S. military superiority to guarantee

continued access to inexpensive oil. Populist nationalists reject the

universalism of neoliberalism and the multiculturalism of the global justice

movement. They hark back to religious, racial and national golden ages and seek

protection from immigrants and the poor of the Global South. Politicians

mobilize support from those who have not benefited from neoliberal capitalist

globalization, often using nationalist or racial imagery. The New Global Right

is both a response to neoliberal capitalist globalization and to the New Global

Left. And the New Global Left is increasingly responding to what many perceive

to be the rise of 21st century fascism. The interesting world

historical question is how the NGR is similar to and different from the Global

Right that emerged out of the World Revolution of 1917 in the 1920s and 1930s.

Fascism (nationalism on steroids) was a reaction to the crisis of global

capitalism that occurred in the first half of the 20th century.

Strong fascist parties and regimes emerged in several core and non-core

countries (Goldfrank 1978), and there were even efforts to organize a fascist

international. Fascist movements were driven in part by the threats posed by

socialists, communists and anarchists. And, in turn, the popular fronts and

united fronts that emerged on the left in the 1930s were partly a response to

the threats posed by fascism. The New Global Right is mainly

populist nationalism now, but if another, deeper, global economic crisis

emerges (which is likely) it could morph in to true fascism.

Formal Network Studies

The

hierarchical structure of the world-system and its systemic boundaries can be

empirically studied using formal (quantitative) social network methods. The

method of formal network analysis is appropriate because world-system theory is

based on interrelations among sets of actors in which both direct and indirect

connections are important. Perceiving

the world-system as a global network of local and transnational interactions

among individuals, organizations, states and international organizations

(Wilkinson 1987, 1991) warrants the application of network methods to describe

the system and to test hypotheses. In the following section we review research

that has used formal network analyses to study the modern world-system.

The world-system functions as a network of

entities that are involved in a variety of different kinds of interactions.

Social network science is a relatively young approach (Granovetter 1973,

Wellman 1983). The application to world-system research dates back to David

Snyder and Ed Kick’s (1979) study of world-system position and the economic

growth of nation-states. The relational understanding of economic growth among

nations has been central in the theories of the founding fathers of political

economy (See Smith 1776 [1977]). Ricardo’s principle of comparative advantage

was premised on a concept of dyadic relations among pairs of nations. As such,

it postulated that a nation will draw maximum benefit if it exchanges goods and

services produced at a lower cost by another nation. In this dyadic exchange,

the greatest goods will be optimized for the greatest number of people. The

classical economists such as Smith and Ricardo did not contextualize exchanges

between dyads of nations when developing this formulation. Dyadic exchanges

occur within a complex structure of indirect connections. These complex structures

of direct and indirect connections are the reality behind hierarchical

core/periphery relations position in this global hierarchy has consequences for

national development and is an important determinant of economic, political,

and social welfare outcomes that tend to disadvantage the non-core. These

structural consequences can be better captured by treating international and

transnational relations as networks of direct and indirect ties.

A social network refers to connections

among a set of entities, which can be individuals, nation-states, firms or

other types of actors (Wasserman and Faust 1994). World-systems theory

emphasizes the hierarchical positionality of global relations without offering

ways to operationalize these concepts (Snyder and Kick 1979). Social network

analysis (SNA) offers a way of empirically testing hypotheses about the

consequences of positionality by means of its mathematical algorithms for

deriving characteristics of whole networks and of network nodes from

information about all the direct and indirect connections among nodes. SNA provides a mechanism to explain how

entities in social systems are connected to each other directly as well as how

the disparate parts of the network can affect each other through indirect

linkages (Borgatti et al 2013). Because of these advantages SNA has been used

by a growing number of researchers for studying the world-system (Lloyd et al. 2009).

The

world-system studies applying SNA methods use network algorithms to assign

countries and cities to their proper positions such in the core, the periphery

and the semiperiphery. These methods portray the boundaries between these

structural positions with a great accuracy and indicate whether or not these

conceptual categories are empirically separate from one another (Arrighi and

Drangel 1986) or are just labels for different positions on a continuous

hierarchy (Chase-Dunn 1998: Chapter 10). The core/periphery structure in the

SNA approach has its own unique concept. According to Borgatti and Everett (1999),

the network core/periphery model is based on the notion the core nodes are

connected to other core nodes in a maximal sense and they are only loosely

connected to the periphery nodes by a cohesive. An SNA core/periphery structure

reveals patterns of interaction among entities constituting the core and

periphery and the extent to which advantages are accrued to the core by these

connections.

The

SNA studies of the world-system test the notion of structural hierarchy, but

they also assess the unequal exchange relations between the zones and the

extent to which there is mobility between zones. The most common method used is

to identify roles and positions of each entity in a network of relations

(Wasserman and Faust 1994, Borgatti et al.

2013). This approach proceeds from a relation or set of relations to predict

the degree of similarity among nodes based on “equivalence criteria” assigning

entities to equivalent groups or blocks (Lloyd et al. 2009). World-system

studies using SNA employ two different approaches for identifying the role and

position of a nation-state: structural equivalence, which uses the CONCOR

network algorithm, and regular equivalence (structural isomorphism), which is

associated with the REGE algorithm. These algorithms assume that a node’s

position in set of relations should be defined by its connections with other

nodes (Borgatti and Martin 1992). Structural equivalence is a very strict

criterion, as it requires structurally equivalent nodes to have identical

relationships with other nodes. In terms of countries, two nations would be

structurally equivalent with one another if they have exactly the same trading

partners. This approach is not useful for assessing the structure of the global

system because the requirement of exact structural equivalence is almost never

met (Smith and White 1992). Because of this SNA studies of the world-system

usually use regular equivalence. In this case the U.S. and Belgium occupy the

same position in the world economy even though they do not necessarily trade

with the exactly the same nations.

The

strict structural equivalence criterion was first used in Snyder and Kick’s

(1979) classical block-model study, which analyzed the world-system structure

using both economic and non-economic ties–trade flows, diplomatic relations,

military interventions and conjoint treaty membership– among nations spanning

1960-1967 period to examine the structural positions of the whole system. Using

CONCOR, they found that the structural core/periphery relationship was more

evident in trade relations. Snyder and Kick discovered a more refined

world-system structure in which there were three partitions within the

semiperiphery and six within the periphery. They used their SNA-derived

position measures in a cross-national regression to examine differences in

rates of economic growth. Their OLS regression analysis showed that the

differential economic growth among nations was attributable to their position

in the world-system such that the core tended to be more grow more than the

lower tiers. This contradicted the notion that linkages to the developed

nations bring modernization and development. A more recent study using

structural equivalence criterion (Kick and Davis 2001) confirms that the core

primarily consists of Western industrial nations.

Studies

employing regular equivalence (Nemeth and Smith 1985 and Smith and White 1992)

also analyze the core/semiperiphery/periphery structure and the extent to which

there is mobility across these categories. Smith and White (1992) examined the

trade data for industrially sophisticated commodities at three different time

points, 1965, 1970, 1980. Their block model of regular equivalence yielded five

different world zones: core, strong semiperiphery, weak semiperiphery, strong

periphery and a weak periphery. Their results indicated that higher zones of

the world-system produce capital intensive manufactured goods while lower zones

produce labor intensive commodities. Their analysis of trade data for 1965 and

1980 revealed more upward mobility than downward mobility in the world division

of labor (Smith and White 1992). Their findings implied that the categories of

the world-system are more continuous than categorical.

The most recent studies have a mix of

results sometimes confirming the results of the earlier studies and at other

times contradicting them. For example, Mahutga (2006) constructs five sets of

block models that contain several zones: core, strong periphery, strong

semiperiphery, weak semiperiphery, strong periphery and periphery. Analyzing

economic data spanning 1965 to 2000, he concludes that the international

division of labor based on the unequal exchange between the core and periphery

remains intact, with upward mobility being evident in only a few countries. A

study by Kick and Davis (2000) found that the classical three-tiered structure

had been replaced by a core, a semi-core, a semiperiphery and a periphery. Kim

and Shin (2002) explain this trend as due to a dynamic process of

globalization. Looking at commodity trade networks from 1959 to 1996, they

argue that the world became increasingly globalized. The growth in the number

of trading partners allowed poorer

peripheral countries to become more integrated into a world economy that was

becoming less hierarchical (Kim and Shin 2002).

Other studies (Kick, et al 2011) have found that there are multiple

cores but that the core/semiperiphery/periphery structure as formulated by

Wallerstein (1974) remains intact. Contrary to this finding, Clark and

Beckfield’s (2009) trichotomous partition model based on the international

trade network during the 1980 to 1990 decade found an expanded core and a set

of upwardly mobile states from the semiperiphery and the periphery. They also found an expanding core, a

semiperiphery and stagnating periphery but they also show that the network still

exhibits a core/periphery hierarchy.

Global political sociology can benefit

from the use of formal network analysis to better understand the trajectories

of political and economic globalization. Knowledge of both the attributes of

entities and their direct and indirect connections are needed. The formal

network studies have tended to confirm the utility of the world-systems

concepts for describing and explaining recent global social change.

REFERENCES

Amin,

Samir. 1980a. Class and Nation,

Historically and in the Current Crisis. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Amin,

Samir. 1980b. “The Class Structure of the Contemporary Imperialist System.” Monthly Review 31(8): 9-26.

Arrighi, Giovanni. 1994 The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Time. London: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Jessica Drangel. 1986. "Stratification of the World‑Economy: an Explanation of the Semiperipheral

Zone." Review 10:1(Summer):9-74.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos and Governance in the Modern World-System:

Comparing Hegemonic Transitions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

___________, Takeshi

Hamashita and Mark Selden 2003 The resurgence of

Borgatti,

Stephen and Martin Everett 1992. “Notions of Positions in Social Network

Analysis.” Sociological Methodology, 2:1-35.

Borgatti,

Stephen and Martin Everett 1999. “Models of Core/Periphery Structures.” Social Networks, 21:375-95.

Brieger,

Ronald L. 1981. “Structures of Economic Interdependence Among Nations” Pp.

353-79 in Continuities in Structural Inquiry, edited by Peter M Blaue and

Robert K. Merton, London: Sage Press.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher. 1998. Global Formation.

Structures of the World-Economy. 2nd Ed. Boston: Rowman and

Littlefield Publishers.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Peter Grimes 1995. “World-Systems Analysis.” Annual Review of Sociology 21: 387-417.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise

and Demise: Comparing World-Systems. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Thomas

D. Hall, "Cross-world-system comparisons: similarities and

differences," Pp. 109-135 in Stephen Sanderson (ed.)

Civilizations and World Systems Studying

World-Historical Change. Walnut Creek,

CA.: Altamira Press (1995).

Chase-Dunn, Chris, Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence and Hiroko Inoue 2011

“Last of the

hegemons: U.S. decline

and global governance” International Review of Modern

Sociology 37,1: 1-29 (Spring). https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows65/irows65.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and

Hiroko Inoue 2012 “Accelerating democratic global

state formation” Cooperation and Conflict 47(2)

157–

175. http://cac.sagepub.com/content/47/2/157

Chase-Dunn,

C. Hiroko

Inoue, Alexis Alvarez, Rebecca Alvarez, E. N. Anderson and Teresa

Neal 2015

“Uneven

Political Development:: Largest Empires in Ten world Regions and the

Central International

System since

the Late Bronze Age” IROWS Working Paper

#85 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows85/irows85.htm

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Bruce Lerro 2016 Social Change:

Globalization From the Stone Age to the Present. New York: Routledge

Clark,

Rob and Jason Beckfield 2009. “A New Trichotomous Measure of World-system

Position Using the International Trade Network.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 50(1): 5-38.

Ekholm,

Kasja and Jonathan Friedman 1982.

"'Capital' Imperialism and Exploitation in the Ancient

World-systems." Review 6:1(Summer):87-110. (Originally published pp. 61-76 in History and Underdevelopment, (1980)

edited by L. Blusse, H. L. Wesseling and G. D. Winius. Center for the History

of European Expansion,

Erin,

Şakin. 2008. Ottoman Empire’s Role in the Emergen of the

“European” World-system. Frankfurt: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller Publishing House.

Frank,

Andre G. 1966. “The Development of Underdevelopment.” Monthly Review 9:17-3.

[Republished in 1988, reprinted 1969 Pp. 3-17 in Latin America: Underdevelopment or Revolution, edited by A.G.

Frank. New York: Monthly Review Press.]

Frank,

Andre G. 1967. Capitalism and

Underdevelopment in Latin America. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Frank,

Andre G. 1969. Latin America:

Underdevelopment or Revolution? New York: Monthly Review Press.

Freeland,

Chrystia. 2012. Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super Rich and the Fall

of Everyone Else. New York: Penguin Press.

Galtung, Johan 2009 The Fall of the U.S. Empire.

Kolofon Press.

Granovetter,

Mark. 1973. “Strength of Weak Ties.” American

Journal of Sociology, 78(6): 1360-80.

Go, Julian 2011 Patterns of Empire: The

British and American Empires, 1688 to the

present Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Goldfrank, W.L. 1978 “Fascism and world economy” Pp. 75-120 in

Barbara Hockey

Kaplan (ed.) Social

Change in the Capitalist World Economy. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hall,

Thomas and Christopher Chase-Dunn 1993. “The World-Systems Perspective and

Archaeology: Forward into the Past.” Journal

of Archaeological Research 1(2): 121-143.

Henige, David P. 1970 Colonial Governors From the

Fifteenth Century to the Present. Madison, WI:

University of

Wisconsin Press.

Hobsbawm, Eric J. 1994 The Age of Extremes: A History of the World,

1914-1991.

Pantheon.

Frank,

Andre G. and Barry K. Gills. 1993. “The 5,000-Year World-system: An

Interdisciplinary Introduction” Pp.3-55 in The

World-system: Five Hundred or Five Thousand? Edited by Ander G. Frank and

Barry K. Gills. London: Routledge.

Kick,

Edward L. and Byron Davis. 2001. “World-System Structure and Change: An

Analysis of Global Networks and

Economic Growth across Two Time Periods.” American

Behavioral Scientist 44:1561-78.

Kick,

Edward L, Laura A. McKinney, Steve McDonald and Andrew Jorgenson 2011. “A

Multiple-Network Analysis of the World-system of Nations, 1995-1999.” Pp.

311-328 in Handbook of Social Network

Analysis edited by John Scott and Peter J. Carrington. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Lloyd,

Paulette, Matthew C. Mahutga and Jan De Leeuw. 2009. “Looking back and Forging

Ahead: Thirty Years of Social Network Research on the World-system.” American Sociological Association, XV(1): 48-85.

Mahutga,

Matthew C. 2006. “The Persistence of Structural Inequality? A Network Analysis

of International Trade, 1965-2000.” Social

Force 84 (4): 1863-1889.

Mann, Michael. 1986. The

Sources of Social Power, Volume 1: A

history of power from the beginning to A.D. 1760. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

Mann, M. 2013 The Sources of Social Power. Vol. 4:

Globalizations, 1945-2011. Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press.

________. 2016 “Have human societies evolved? Evidence from

history and pre-history” Theory and

Society 45:203-237.

McMichael,

Philip. 2012. Development and Social

Change: A Global Perspective. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publicatios.

Modelski,

George and William R. Thompson. 1996. Leading Sectors and World

Powers: The

Coevolution of Global Politics

and Economics. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina

Press.

Modelski, George. 2005. “Long-Term Trends in Global

Politics.” Journal of World-Systems

Research. 11(2): 195-206.

Nemeth,

Roger J and David A. Smith. 1985. “International Trade and World-system

Structure: A Multiple Network Analysis.” Review,

8:517-60.

Patomaki, Heikki 2008 The

Political Economy of Global Security. New

York: Routledge.

Robinson, W. I. 2014 Global Capitalism and the Crisis of

Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Schneider, Jane. 1977. “Was there a

Pre-capitalist System?” Peasant Studies

6(1): 20-29.

Silver,

Beverly and E. Slater 1999. “The Social Origins of World Hegemonies”. In G.

Arrighi,

et

al Chaos and Governance in the Modern World System. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press,

151-216.

Smith,

Adam. 1776 [1977]. An Inquiry into the

Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

Smith,

David A. and Douglas R. White. 1992. “Structure and Dynamic of the Global

Economy: Network Analysis of International Trade 1965-1980.” Social Forces, 70(4): 857-893.

Snyder,

David and Edward L. Kick 1979. “Structural Position in the World-system and

Economic Growth, 1955-1970: A Multiple-Network Analysis of Transnational

Interactions.” American Journal of

Sociology 84: 1096-126.

Tilly, Charles 1984 Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge

Comparisons. New York: Russell Sage

Foundation.

Wallerstein,

Immanuel. 1979. The Capitalist World

Economy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984 “The three instances of hegemony

in the history of the

capitalist

world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues

and

Research

in Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology and Social

Anthropology,

Vol.

37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Wallerstein,

Immanuel. 1993. “The World-System after the Cold War.” Journal of Peace Research,

30(1):1-6.

Wallerstein,

Immanuel. 1999. The End of the World as We Know It: Social

Science for the Twenty-First Century. Minneapolis, MN: The University of

Minnesota Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2000. The Essential Wallerstein. New York: The

New Press.

Wallerstein,

Immanuel. 2011 [1974]. The Modern

World-System, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel and

Terence K. Hopkins. 2000. "Commodity Chains in the World-Economy Prior to

1800." in The Essential

Wallerstein. New York: The New Press.

Wallerstein,

Immanuel, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian, and Craig Calhoun.

2013. Does Capitalism Have A Future?

New York: Oxford University Press.