Racism and The Evolution of

Distant Othering

Chris

Chase-Dunn, Marilyn Grell-Brisk and E.N. Anderson

Institute

for Research on World-Systems

University

of California-Riverside

To be

presented at the ASA session on “The ‘Other’, Global Inequalities, and Race”

Sun, August 12, 2:30 to 4:10pm, Philadelphia, PA. This is IROWS Working Paper

#129 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows129/irows129.htm

V 8-2-18, 14416 words

Abstract: This paper presents an

overview of the ways in which human individual and collective identities and

ideas about outsiders have changed as human polities have gotten larger, more

complex and more hierarchical since the Stone Age. We are especially interested in forms of

distant othering that are similar in some ways to modern racism and seek to

understand how racism has evolved and where it may be going. We contend that

all human polities have defined the boundaries of solidarity and support in

ways that excluded and demonized other humans and non-humans, but that the

boundaries have expanded over time to include larger and larger numbers of

people. Boundary expansion has not been a smooth upward curve. When population

grows beyond the ability of institutions to provide resources, people go back

to smaller units of solidarity to try to protect their access to

resources. Thus, there have been cycles

of expansion and contraction with occasional upswings in the scale of

cooperation. And both solidarity and othering are entwined with the building

and maintenance of power structures. Status threats

incite reactive movements when status characteristics are changing, especially

on the part of those who think their privileges and resources are threatened. Comprehension

of the long-term cyclical trends of inclusive solidarity and othering has

implications for meeting the challenges of the 21st century.

We

are social scientists studying the long-term, large scale evolution[1] of

organizational structures, institutions and the ideational changes that relate

to the scale changes that have emerged since the Stone Age. We employ concepts

mainly from sociology and anthropology, disciplines that have examined

sociocultural evolution and the behavior of human individuals and groups. Our

discussion presumes the classical and contemporary literature on the self as an

institution (Mead 1934), identity theory, the connection between the self and

others, role theory and Simmel’s important concept of social distance (Simmel

1955, 1971).

Othering is based on the

construction of socially legitimate boundaries between the individual self and

others and between “us” and “them” -- in-groups and out-groups. Othering and selfing are like wrestlers in a clinch. All human societies

have organized identities around othering. And othering has always been

important for reproducing differences and inequalities. But “the other” has

evolved along with the uneven expansion of social complexity and the emergence

of hierarchies since the Stone Age. This paper describes the evolution of the

self, the other and the forms taken in distinguishing between in-groups and

out-groups with a focus on how racism as a form of othering has changed over

the course of human sociocultural evolution from Stone Age nomadic foraging

groups to the contemporary global system.

We mainly focus on the issue of socially distant others because we want

to discern the ways in which things like modern racism have existed and evolved

in the past.

Our theoretical perspective is institutional

materialism and we study sociocultural evolution using the comparative

world-systems perspective (Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2015). Immanuel Wallerstein (1987) contended that racism is structurally

connected with the modern core/periphery hierarchy. Thus, we are very

interested in the issue of modern global racism as it is related to the

core/periphery hierarchy in the contemporary global system. We also want to

inquire about the connections between distant othering and premodern

core/periphery hierarchies.

Georg Simmel (1955, see also Coser 1956) noted that conflict is an important form of

association because in-group solidarity is related to, and mainly produced by,

competition and conflict between groups. What “they” are depends on, and is

related to, what “we” are and what “I” am.

Sociocultural evolution has involved the invention of institutions that

allow larger, more complex and more hierarchical human polities to function.

Accompanying these long-term changes have been the emergence of more complex

selves as well as larger and more abstract collective identities and

solidarities. And these have been related to the restructuring of

conceptualizations of internal and external others. Human nature is understood

biologically to include the capability for institutionalized and socially

constructed categories to be taken as natural and real (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2015: Chapter 3). As is well-known, racism is

socially constructed. It works differently in different modern polities, and it

has taken different forms as human polities got larger and more complex.

Status characteristics are beliefs

about social categories that are consensually held by members of a society

(Berger, Cohen and Zelditch 1972). Status

characteristics are stereotypes that structure expectations about the behavior

and evaluations of others, especially strangers. Many status characteristics

are ranked. Examples are wealth, income, education, gender, ethnicity and

race. In this approach, racial

categories are socially constructed, and the content and evaluation of these

categories differ across societies and change over time within a society.

Profiling is an example of how status characteristics affect expectations. And

expectations about behavior often stimulate feelings such as comfort, fear and

anger. Status characteristics vary in the degree of consensus about them. They

are often contested, and they change over time. Status threats incite reactive

movements when status characteristics are changing, especially on the part of those

who think their privileges and resources are threatened. Obvious contemporary

examples are race and gender (Alvarez 2019)

The idea of social distance is made

most clear in Simmel’s (1972 [1908]) essay on the stranger. Simmel’s stranger

lives within the local society but is seen as socially distant from most of the

community members. This distance is primarily due to the stranger’s origins. Of

course, Simmel is talking about Jews in Europe and ethnic minorities. Social

distance does not equate physical distance as the stranger is simply

“perceived” as outside the group despite being in constant contact with the

group. This stranger is in the group but not of the group. Still, there can be

both internal and external distant others. For example, the phenomenon of

scape-goating may involve identifying and blaming

enemies within the society and external enemies. Our discussion of the

evolution of distant othering will take this into account.

The analysis of modern racism often

distinguishes between the attitudes, beliefs and emotions of individuals and

institutional or structural racism in which outcomes of power processes produce

material inequalities. Here we are

interested in the subjective (individual and collective) aspects of othering,

and in the connections between the institutional and structural forms of power

that produce differential outcomes.

The

evolution of human sociability, language, and culture remains highly

controversial. There is no question that

intolerance, prejudice, and othering are deeply inscribed in human society (Kteily, Bruneau, Waytz, and

Cotterill 2015; Kteily, Hodson, and Bruneau 2016).

Castano has argued that the hated or despised group is typically thought of as

human, just unworthy of consideration or of good treatment. This is primarily

due to a lack of empathy. He introduces the term “infrahumanization”

for this. Genocide and prejudice scholars have remarked on this phenomenon.

For Thomas Hobbes (1657) and John

Locke (1689), humans in their natural state were true “savages” (Latin homo sylvaticus, “person

of the forest”). They were warlike,

isolated in small groups, nomadic, and without laws, private property, or true

moral orders. The authors located their

“savages”, not amongst themselves but rather, in “America,” despite having

plenty of material at hand to show them that American Native people were not

even remotely like their stereotypes.

Still, Hobbes and Locke’s notion of

the savage was most likely based on the old idea of the “wild man,” going back

to Enkidu and persisting in the medieval European “savages” and “wodewoses.” This

idea of the “savage” in America created a foundation for the despicable

treatment of Indigenous people by the settlers of the New World and

Australia. The most striking exception in

the early exploration period is the very strong and enlightened advocacy of the

Spanish humanists, notably Bartolome de Las Casas (1992, orig. 16th

century), but also Diego Duran, Bernardino de Sahagun, among `others. They fearlessly and successfully argued that

Native Americans were fully human, had souls, could not be killed at will, and

had rights (including property) that had to be respected. They argued less successfully that Native

people should not be enslaved.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau later argued

for a less negative view of “savages.”

Contrary to persistent myth, he never used the phrase “noble savage,”

nor did he think savages were particularly noble. His savage was in fact the chimpanzee

(Rousseau 1986 [1755]), which was, indeed, hairy, nonlinguistic,

forest-dwelling, somewhat social, and powerful, like the wodewose. He was the first, but far from the last, to

see the chimp as our ancestor.

Religious wars spun out of control

in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, leading to

exhaustion that led in turn to religious tolerance in a few countries (Te Brake 2017). The

slave trade, already huge, vastly increased in the 18th

century. Rapid colonial expansion led to

genocides from Australia and the Americas to west China (the Dzungarian genocide

of the mid-18th century) and Siberia. It is with settler colonialism and the slave

trade that we see a significant rise in racism and distant othering, and in the

idea that distant people are savages or otherwise inferior. More precisely, Stocking (1968) and Baker

(1998) have demonstrated that the rise of racism can be traced to its

connection with exploitative economics.

Samuel Bowles (2006, 2008) argued

that humans evolved in competing groups; the bigger and more combative groups

eliminated the smaller ones, leading to the rapid evolution of larger groups

and more warlike and murderous behavior.

Despite factual evidence to support it, this notion has been challenged.

The most recent contribution is based on a sophisticated simulation involving

comparison of a wide range of mammals. González-Forero and Gardner (2018) argued that bigger brains allow

bigger social groups and more communication, which allow better foraging, and

thus a positive feedback mechanism is created.

Sociability alone could not account for the increasing size of the human

brain over time because mammals that are highly social, actually

have smaller brains than their more independent relatives (gnus and

naked mole-rats are examples).

Competition does not either, since it has high costs that interfere with

maintaining large brains and complex behavior.

They conclude that only a widening diet and ecological niche can explain

it, pointing to social omnivores of high intelligence, such as raccoons and

wolves.

While this is a good model (cf. Anderson 2014), it does

not explain the extreme levels of intergroup violence and hatred that exist in

almost all known societies. The most likely scenario is one in which large

foraging groups expanded into new areas, displacing existing smaller

groups—initially, at least, more primitive hominins.

Nevertheless, not all human groups are combative. A few extremely peaceful ones are known.

These are typically small and threatened by larger, stronger and more

aggressive neighbors; coming to peace through fear. In the best comparative

study to date, Robarchek and Robarchek

(1998) compared the extremely peaceful Semai, with

the more violent Waorani. Both societies were fairly

similar in their everyday existence, hunting, food cultivation, system

of lineage. They practiced permissive childrearing and were gentle and tolerant

most of the time. The only difference relevant to their behavior was their

relations with outsiders. The Semai were constantly

harassed, robbed, and enslaved by the far more powerful Malays, and had no

recourse except to flee. There was little doubt that their peacefulness was

basically fear: they could not successfully resist and therefore would chose to

leave. They generalized their fear response into nonviolence in all situations. The Waorani were

able to fight back against heavy odds, succeeding in part by creating the image

of themselves as utter mad-dog fighters.

Again, they generalized this response.

The Robarcheks noted that people can choose

where to situate themselves on the fight-flight-freeze response continuum, and

then culture constructs responses.

Falk and Hildebolt (2017)

showed that societies worldwide have an average violence rate that is moderate,

but that tribal societies vary enormously.

The Semai and their neighbors pin the peaceful

end, the Waorani and the New Guinea Highland groups

anchor the warlike one. Small

hunting-gathering bands are generally relatively peaceful, and so are modern

states. Chiefdoms and early states are

particularly violent. Steven Pinker

(2011) argues that peacefulness has been increasing throughout history; figures

loosely support him, but many anthropologists consider his work on tribal

violence highly exaggerated and note that he underplays modern violence,

relying e.g. on war and murder rates without looking into genocide, slavery,

and deliberately-caused famine (Fry 2013).

In almost all cases, neighbors are enemies. Neighboring tribes and states develop

enmities that grow over time. The famous

rivalry of the French and English is typical.

Other cases include the Thai vs. the Burmese and Khmer, the Chinese vs.

the central Asian steppe peoples, the Japanese vs. the Koreans, the Amhara vs.

the Tigre and Oromo, the Aztecs vs. the Tlaxcalans,

and so on around the world. Typically, a

polity—be it a hunting-gathering band or a modern state—will ally itself with

the neighbor’s neighbors on the other side.

The hated group is thus crushed between two polities. This is a dangerous strategy, however. Once the hated group is crushed, the two

allies are suddenly each other’s’ neighbors.

They then often fight. As an

example, in the Mongol conquest of China, the Song Dynasty allied itself with

the Mongols to crush the Jin Dynasty, but once Jin was destroyed the Mongols simply went on to conquer

Song—using the Jin armies, now Mongol subjects!

Highly negative stereotypes of neighbors are

universal. Neighbors are subhuman,

immoral, disgusting, and, in short, barbarians, to the extent they are

culturally different from “us.” In non-state

societies, there is usually little contact with groups more remote than the

immediate neighbors, but some societies specialized in long-range raiding and

slave-taking on a large scale. Examples

range from the Haida and Lekwiltok of the Northwest Coast

of North America to the Vikings, some Turkic groups, and the East African

Arabs. Such groups always develop highly negative stereotypes of the

people they raid, partly to justify to themselves the cruelty they use in their

activities.

Otherwise, truly distant peoples are little

considered. Often, they are thought to

be too weird to be truly human. The

bizarre beings in Pliny—the dog-headed people, people whose faces are on their

chests, and so on—are matched by the beings in the Chinese Classic of Mountains

and Seas (Shan Hai Jing 1999), which

apparently represent shamanistic visions of spirit lands.

This brings us to the important and underappreciated fact

that worldwide, strangers are generally

welcomed. Field anthropologists have

found themselves welcomed everywhere except in societies that had had recent

and frequent negative interactions with outsiders. Even E. E. Evans-Pritchard (1940), carrying

out ethnographic research on a group that had been subjected to seven major

British colonial military assaults in the recent past, managed to do a thorough

ethnography in spite of intense early suspicion. Most field ethnographers report incredible

levels of hospitality, generosity, and help.

It is the neighbors that one hates, not the aliens. Almost every comprehensive ethnography

records negative stereotypes and historic feuds with neighbors.

Stone Age Othering

As populations

grew the annual migration routes of nomadic foragers shrank and eventually

sedentism emerged as people learned how to store enough food to remain longer

in winter camps that became hamlets and then villages (Nassaney and Sassaman 1995). The

transition from larger to smaller annual migration routes corresponded with the

emergence of regional styles of tool kits, especially projectile points, that

archaeologist interpret as evidence of the emergence of regional ethnic

identities.

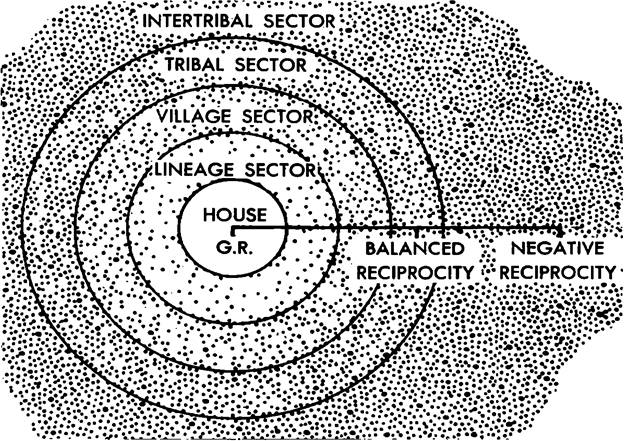

We begin with Marshall Sahlins’s (1972: 196-204) typology of the institutional

forms of interaction in small-scale, Stone Age, societies. In small-scale human

societies the economy and the polity are mainly organized around kinship, a

consensual normative moral order that designates social obligations based on a

set of kin categories that individuals occupy. Sahlins

notes that sharing and reciprocity are usually organized in such societies

based in kinship distance. Sharing, or what Sahlins

calls generalized reciprocity does not calculate who gets what and so there is

no quantification of debt.[2]

All the interactors have the right to take what they need and the failure to

reciprocate does not result in the giver ceasing to give. In Sahlins’s model of the “domestic mode of production this

form of interaction occurs among very close kin, usually within the household.

His diagram of kinship distance and forms of exchange (1972:199

Figure 5.1. Reciprocity and Kinship Residential Sectors) is a nested set of

circles with the household in the center. As we move out from the center to the

lineage and village sector the type of interaction becomes “balanced

reciprocity” in which a gift is expected to be repaid.[3]

Beyond the village sector is the tribal sector, and beyond that is the intertribal

sector where something called negative reciprocity is in operation. Negative

reciprocity is a relationship in which theft is legitimate. There is no

expectation of repayment. One is supposed to get as much as one can and give as

little.

Figure 1. Reciprocity and Kinship Residential Sectors Source: Sahlins 1972: 199 Figure 5.1.

This model of institutional types of

interaction is germane to understanding the ways in which individual and

collective identities operate within small-scale societies and is both similar

and different from the ways in which modern individual and collective

identities and the other operates. The self has much obligation to socially

close others and obligation decreases with social distance until it becomes

negative reciprocity involving either no obligation or active enmity. Most small-scale societies had little

inequality among lineages and so rank did not play a big role in structuring

forms of interaction.[4] We know from ethnographic studies of

small-scale societies that genders were highly differentiated, though some had

third-gender men who lived socially as women and had important jobs. But gender

differentiation was usually not accompanied by gender hierarchy. The identities of men and women were

constructed as different, but women usually had important participation in

group decision-making. And these small-scale societies usually had a form of

individualism that was organized as differentiated relations with spiritual

allies. Coming of age for each person involved a spirit quest in which a deal

was made with one or more powerful allies. Thus, the relationship with the

powers of the universe was somewhat constructed by each individual and each had

a personal relationship (or relationships) with these that changed over time.

Every person was unique with regard to his or her

relationship with spiritual others. Those individuals, both women and men, who

spent more time communicating with their spiritual allies were deemed to be

doctors or shamans who had the ability to help others ward off bad spirits

causing sickness. This form of individualism existed despite a very simple

societal division of labor in which all men were hunters and all women were gatherers.

Animistic religions saw non-humans and what moderns see as inanimate objects,

such as trees or mountains, as the other.

A mountain is a spiritual power that requires demonstrations of respect

lest it do injury. The universe is alive, and the entities require respectful

communication. Shamanic specialists become possessed by spirits and can take

the form of a bird or an animal or insect. Every person has the capability to

use spiritual allies to do harm or good to others, and so everyone could become

a witch. This possibility can undermine the solidarities and trust expected of

close kin and co-villagers, which could cross-cut the outer edges of

reciprocity in ways that reduce the ability of polities to mobilize warfare

with one another (Bean 1974).

Leadership was usually a matter of a

designated head man who welcomed visitors on ritual occasions and gave

speeches. The head man is also often entrusted with the care of the village

medicine bundle that is the symbol and substantiation of the sovereign polity.

This position usually passed from father to son, but if no son with appropriate

rhetorical skills were available the position might pass to a daughter.

Specialized leaders were sometimes designated to coordinate intergroup hunting

efforts such as deer drives. Usually the best hunter was selected for this.

In some ethnographically-known societies of sedentary

foragers the head man sometimes had more than one wife, often the sister of the

first wife (sororal polygyny). Sovereign

polities usually included one or a few villages. Beyond that, alliances were

formed based on participation in ritual feasting, dancing, gambling, reciprocal

gift-giving and support in warfare (Vayda 1967). Wars were of two kinds: line wars were ritual

encounters meant to resolve violation of collective territorial claims to

gathering or hunting sites or other transgression. The two sides would line up and throw rocks

or shoot arrows at one another until someone was injured. Then the headmen from

each side would talk about whether what had happened could resolve the issue or

not. If not, the “fighting” could continue. Eventually the issue was usually

resolved without much injury. Line wars

tended to occur among polities who shared a language or who had ties by

inter-marriage. The other kind of warfare was raiding. In a raid, a village of the

enemy was attacked, and an effort was made to exterminate all the residents.

Raid wars occurred primarily between polities that did not share a language and

between which there were few intermarriages.

The difference between line wars and

raid wars suggests an important distinction between types of negative

reciprocity. There is a big gap between indifference and a level of enmity that

justifies extermination. Close othering involves both

similarities and obligations, while distant

othering involves differences and either no obligation or negative

obligation (enmity). In many small-scale

societies the word for those who share a language often means “the people.”

This implies that others outside of this collective identity are the

non-people. This is an important form of distant othering that is similar too,

but also different from, distinctions between in-groups and out-groups in

larger scale polities. Often distinctions about differences in beliefs about

creation or differences in food preferences are used to denigrate proximate and

more distant others. All human polities have something like modern nationalism,

a collective identity in which people see themselves as like one another and

different from others. The general term for such a collective identity is

“solidarity.” Collective identities are

first constructed in kinship terms, but later they are constituted in different

ways.

Trade among small-scale societies is

usually organized as gift-giving between heads of physically adjacent polities.

Goods may travel long distances from being traded from group to group

(so-called down-the-line trade) but there is no long distance “merchants”

bringing goods from afar. This is because strangers from afar are usually seen

as trespassers and are likely to be killed. Long-distance trade or procurement

treks are extremely dangerous. An example of an internal stranger would be a

witch who is believed to use spiritual power to harm others. Such internal

strangers are often killed. Distant othering also involves stories about

giants, demons, wild men (sasquatch or big foot) and old women who steal

children and eat them (Suttles 1987: Chapter 6).

An intermediate form of distant

othering also found in some small-scale societies occurred when war captives were

taken to be traded. The pre-contact Pacific Northwest of North America feature a large, hierarchical system in which the core

polities had enough economic power to motivate the peripheral polities to

employ warfare against one another. Within the coastal polities (Haida, Kwatkiutl, Tlingit, etc.,), hereditary “big men” maintained

their status and power in a system of competitive feasting and gift-giving

known as the potlach. These maritime polities were hunter-gatherers with access

to valuable coastal food resources (marine mammals, fish and shellfish): they

had enough economic power to extract war captives from peripheral polities. The

peripheral polities raided one another and sold captives in exchange for food and other valuables. The coastal polities had ranked

lineages, slaves, and a very strong ideology of superior birth. Between five and

twenty-five percent of the population of the coastal polities were slaves

(Mitchell and Donald 1985). This was an unusual kind of core/periphery

hierarchy.

The Pacific Northwest shows the existence of

economic imperialism in the absence of pronounced commodification. A

proto-money (dentalium shells) was used as medium of exchange. But most

exchange took the form of reciprocal gift-giving carried out by village heads.

This down-the-line trade relocated war captives from distant slave raiders to

the maritime core polities. But slaves and their children in the core polities

usually became integrated into the local kinship system by marriage and

adoption: so, this was a very different kind of system from the better-known

chattel slavery based on racism that emerged in and was an important

developmental feature of the modern Europe-centered world-system (Patterson

1982). Regarding the issue of distant othering, the ability of the war-captive

slaves to regularly become integrated into the core kinship structures implies

the absence of a form of distant othering that conceptualizes subordinates as

permanently inferior (like racism). This

case is unusual both because it was a form of imperialism and core/periphery

exploitation that was not based on the project of military power from the core

to the periphery, and because it formed a core/periphery hierarchy that was not

based on racism or a form of distant othering similar to

racism. The integration of former slaves into the kin networks of the core

societies implies a lack of distant othering similar to

racism.

Othering

in Big Man and Chiefdom Systems

Human settlements and polities grew, and socially constructed

inequalities increased, at first in chiefdoms and then in early states. Big man and chiefdom polities evolved

hierarchical forms of kinship in which lineages were ranked and class

distinctions between commoners and sacred chiefs became institutionalized. Chiefs were members of lineages that were

thought to be more closely descended from founding ancestors and to have

special powers over the forces of the universe. Commoners had no legitimate

independent claim to land and were thought to be only very distantly related to

revered ancestors. This was the birth of class society and it had significant

consequences for the social construction of selves as well as close and distant

others. Land and nature, rather than seen as a living spirits that all were

empowered to placate, became the property of chiefs because of their alleged

descent from revered ancestors. Creation myths typically involved stories about

ancestor coming out of local caves or geographically dramatic islands.

Topophilia was reconstructed as legitimation of power. This provided the basis for chiefs to convert

reciprocity into centralized redistribution. Yet, the idea that the leaders and

the led were still linked by generalized reciprocity remained. As Sahlins (1972: 205) notes, “noblesse oblige

hardly cancelled out the droits du

seigneur.”

To have access to

land for horticulture, commoners had to turn over a portion of their production

to chiefs. The chiefs had obligations to the commoners, but the basis of

unequal exchange was laid in the institutionalization of land ownership. And

this was maintained by ideological constructions and by the exercise of

institutionalized coercion. Chiefs imposed taboos to regulate resource use, and

commoners who violated taboos were punished and sometimes killed. This was the

beginning of the tributary mode of accumulation.[5]

But the remaining aspects of reciprocity attached to kinship obligations were a

limitation on how large and centralized a chiefdom could be. This limitation

was eventually transformed by the emergence of states in which the connection

between power and kinship was separated, allowing priests and kings to

autonomously control resources that were not subject to reciprocity.

Cannibalism and

ritual sacrifice of war captives is known from both chiefdom cultures and early

states. This presumes distant othering, but there are interesting ironies.

Maori warriors ate enemy warriors to gain their power, though once this had

happened it became a source of pride for the eater and shame for the eaten. “I ate your grandfather” was a putdown said

by the descendent of a warrior who had eaten someone’s ancestor. The practice

of ritual human sacrifice is frequently found in archaeological evidence from

early states. Ethnographic knowledge

often implies that being sacrificed when a kind died or when a new temple was

erected was seen as a badge of honor, not a statement

about distant othering.

Bronze

Age Othering

Early states and cities first emerged in Bronze Age Mesopotamia in

a region that already had paramount chiefdoms and the beginnings of irrigated

agriculture. States are different from chiefdoms in that they have specialized

institutions of regional control and the central power of the state is less

organized around kinship. The form this took in Mesopotamian cities was

theocracy in which the temple was the state and both the city residents and the

priests were slaves of the city god. The temple economy, which tithed and

redistributed food and other goods, was on top of a kin-based economy organized

around sharing and reciprocity (Zagarell 1986). Kinship identities were still important, but

a new identity had been added –slaves of the city god. The first city to emerge was Uruk, but copycat cities emerged nearby on the flood plains

of the Tigris and the Euphrates, each organized around a different city

god. The city was the god and the state.

The collective identity was organized as membership in an urban community.

“Citizenship” was organized as obligations to the temple and rights to

participate in rituals and feasting. The

temple owned property within the city and agricultural land outside the city.

But kin groups also owned both. These

early states shared a Sumerian language and culture, but earlier

Semitic-speaking migrants from surrounding regions also became residents,

forming an ethnically distinct class of workers and servants (Yoffee 1991).

Cuneiform writing was

invented in the Mesopotamian states to keep records regarding transactions in

the temple. Mental labor and abstract

cognition allowed for the altering of the self of the ruling class and

distinguished them from the selves of the direct producers (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2015: Chapter 9).

Because the

Mesopotamian flood plain contained little stone, and because trees and timber

quickly became scarce, the cities organized long-distance trading with adjacent

regions, trading grain and pottery for copper, tin, building and precious

stones and other goods desired but not locally available. Uruk

organized what was probably the first colonial empire in which citizens of Uruk moved to quarters in distant settlements to carry out

this trade (Algaze 1989, 1993). This was also an

early example of what Philip Curtin (1984) called a “trade diaspora.” Trusted co-citizens or co-religionists take

up residence in distant locations to carry out long-distance trade. This has implications for distant othering.

Non-citizens and

non-co-religionists are not likely to observe the norm of reciprocity. Trade diasporas emerge in a situation in

which trade is profitable but trust and other institutional mechanisms that

ensure payment of debts are not in place (negative reciprocity). When minority

ethnic groups specialize in long-distance trading they become Simmel’s

stranger, an internal socially distant other. Trade diasporas lose their

function when trust and institutional mechanisms emerge that allow direct trade

with distant peoples – what Curtin calls a “trade ecumene.” The

institutionalization of money and markets allows strangers to interact with and

trust one another even though they do not know much about each other or share a

lot of cultural assumptions. Thus, does the emergence of commodification of

goods and wealth, decrease reliance on cultural consensus and facilitate

multicultural interdependence.

Bronze Age

Mesopotamia may be the birth place of a set of othering distinctions organized

around ideas of civilization, barbarism and savagery. But most healthy human societies see

themselves as the center of the universe and this conviction is usually based

on beliefs about cultural superiority vis-à-vis distant others. As reported

above, sedentary foragers already did this and they

had beliefs about the “wild man” that functioned to reproduce what they

believed authentic humans to be.

Gilgamesh was a king of Uruk in a period in

which competing city states were emerging and the palace, home of the battle

king, had emerged as an important locus of power contending with the temple

(Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2015: Chapter 8). Fragments of

early stories about Gilgamesh were woven into single “epic of Gilgamesh” during

the late Bronze Age when Gilgamesh was deified as a culture hero during the

Third Dynasty of Ur, a Sumerian restoration that occurred after the fall of the

Akkadian Empire. The epic of Gilgamesh

reflects the competitive relationship between the temple and the palace.

Gilgamesh refused to become the consort of Inanna, a powerful priestess. And

Gilgamesh got important support from his Wildman friend Enkidu, with whom he

was able to fight and defeat powerful enemies. The Enkidu figure is an

interesting instance of the idea of the noble savage. This is a recurring trope

in all systems that have a core/periphery hierarchy. Peripheral peoples are often seen as inferior

and sometimes as threatening savages, but sometimes they are depicted as noble

savages living in a pure state of nature. Distant othering in core/periphery

hierarchies seems to include both versions at least since the Bronze Age and

they contend with one another. Beliefs about the Wildman are similarly ambivalent

in many cultures (Anderson 2005; Bartra 1994, 1997).

Bronze

Age Mesopotamia also developed the threatening savage version of the distant

other. The

accumulation of stored wealth was greater than ever before, and this

constituted a license to steal for peripheral nomads. Incursions by

nomads from the periphery were an important phenomenon that influenced the

development of agrarian empires and cities in several world regions (Thompson

and Modelski 1998). The Amorite tribes were nomadic pastoralists who came into

Mesopotamia from the deserts of the northwest. In order to prevent their

incursions, the Ur III dynasty constructed a Great Wall of Mesopotamia clear

across the northern edge of the core region (Postgate 1992:43). This led to an

ideology of "subhuman barbarism" that seems to have been somewhat

like modern racism. Jerrold Cooper (1983:xxx) contends that

the Mesopotamians did not generally vilify different ethnic groups, but saw the

Gutians as savage, beastlike imbeciles, and the

Amorites as curious primitives, less horrible, if every bit as threatening

militarily, than the Guti. Cooper’s characterization

of the Sumerian beliefs about the Gutians and the

Amorites suggests that something like racism is not a uniquely modern

phenomenon. Of note here, is that the very negative distant othering in

Mesopotamia seems to have emerged regarding peoples who were

seen as threatening to the core societies. In this case Wallerstein’s

hypothesis of a connection between core/periphery hierarchy and racism is borne

out.

Peter Turchin (2003) argued

that the relevant process is one in which group solidarity is enhanced by being

on a “metaethnic frontier” in which the clash of

contending cultures produces strong cohesion and cooperation within frontier

societies, thus promoting state formation and empire formation (see also Turchin 2009). Turchin focuses

especially on relations between polities that face each other on a transition

boundary between steppe and irrigated agricultural ecological zones.

His (2009) mirror-empires model proposes that antagonistic distant

othering interactions between nomadic pastoralists and settled agriculturalists

often resulted in an autocatalytic process in which both nomadic and farming

polities scaled up their polity sizes. This phenomenon is an instance of

Simmel’s contention that in-group solidarity is produced by between-group

competition, especially when the within-group/between-group difference involves

a large cultural divide.

Iron Age and Axial Age

Othering: The Rise of World Religions

Cities and empires rose and fell, but

they got larger in episodic events that are known as upsweeps (Inoue et 2012;

Inoue et al 2015). Empires rose because states developed the military

capability to conquer adjacent regions and the governance capability to extract

resources from the conquered regions. The law (written rules), bureaucracies,

armies, transportation technologies and the emergence of commodified exchange

using money facilitated the expansion of empires. Trading city states emerged

within the interstices of tributary empires, encouraging commodity production

and the expansion and intensification of trade networks (Chase-Dunn, Anderson,

Inoue and Alvarez 2015). The law emerged

as written rules to extend over groups of people who did not share a single

consensual moral order. This was

functional for states that had conquered and incorporated culturally different

groups. Normative order based on

consensus continued to exist, but within a framework in which the state

proclaimed and enforced laws. The state

had now become an institution that could claim to rule over peoples that spoke

different languages and had different beliefs. But authority in this situation,

is frequently seen as illegitimate and this raises the level of resistance and

rebellion. People who had been conquered often saw themselves as subject to

illegitimate power. Religious social

movements emerged in colonized regions that produced new forms of individual

and collective identities and expanded moral orders to catch up with the scale

of legal orders.

Peter

Turchin (2003: Chapter 9) notes the relevance of Ibn Khaldun’s

cyclical model of the rise and fall of regimes and the importance of changing

levels of asabiyah (loyalty, solidarity and

group feeling) as old regimes became decadent and new challengers emerged from

the desert to form new regimes (see also Amin 1980; Chase-Dunn and Anderson

2005; Anderson 2018). The phenomenon of peripheral and semiperipheral

march states and their role of these in the formation by conquest of larger and

larger empires is related to issues of solidarity and internal othering (Inoue et al 2016). As empires got larger

inequalities within states also became more extreme. Non-core polities were

usually less stratified than core polities in premodern world-systems.

Peripheral

and semiperipheral marcher lords are often alpha

males who have strong solidarity with their warriors, whereas the elites of

urbanized agrarian empires are socially distant from their soldiers and have

trouble inspiring their trust. Institutions like the harem undercut class

solidarity among men, as many poor men must go without female mates because the

king or emperor has so many.

Sex and

Empire

Walter Scheidel’s (2009a) fascinating

discussion of empires and harems employs an evolutionary psychology approach to

explain why men with power wanted to gain sexual access to large numbers of

women; but it also provides an insight into the spreading of a global moral

order that can allow distant othering. Wealthy and powerful kings could have

both the r and the K reproduction strategies.[6] But

why did monogamy become the predominant form of marriage in modern global

culture, even for rich and powerful men. Most polities had allowed polygyny

(one husband, more than one wife) for a small number of men. Human instincts

probably have not changed much over the past 2000 years, but there are few

polities remaining that allow wealthy and powerful men to have more than one

wife (at the same time). So evolutionary psychology cannot supply the answer.

In subsequent work, Scheidel (2009b) has tried to address what is known about

the causes of what he calls the institution of “socially imposed universal

monogamy” (SIUM) and its displacement of polygyny][7] in

world history. A purely historicist explanation would note that the Romans

and the Greeks were monogamous and the European polities that descended from

them eventually took over the world and so monogamy was imposed by the

powerful. Christianity got monogamy from the Romans, as a perusal of the Old

Testament will make plain. Christians took over most of the world because of

European colonialism and the rise of industrial capitalism. Thereby, the rules

of the winners became the global moral order. This is probably the best overall

explanation, although Scheidel points out that there

is very little research on the history of colonialism and monogamy that would

substantiate this account.

Henrich et al 2012 have

published a study of polygyny and monogamy that suggests several ways in which

SIUM is functional for society. This raises the issue of the direction of the

causal arrow between winners and monogamy. Is SIUM a competitive advantage in

competition among polities, and if so how does that work? Since the gender

birthrate is naturally 50/50, elite polygyny deprives some men of wives. This

is a well-known problem for modern religious groups who practice polygyny. Many

young men have no prospect of marrying because older richer men have taken most

of the women. Henrich et al (2012) contend that monogamous

marriage systems reduce competition among males for mates and decrease the

number of unattached males who are an important group in the commission of

violent crimes. So, monogamy decreases competition among men and lowers the

crime rate. And women also benefit from SIUM because it reduces the average

male/female age difference within marriages, lowers the fertility rate, and

reduces gender inequality and within-household violence. Henrich et al.

(2012) also contend that polygyny may have been functional for war-making

empires because it increased the size of the pool of unattached young males who

could serve as soldiers who were strongly motivated to capture women from other

polities.

But it also likely that

SIUM facilitates greater solidarity between elites and their soldiers than does

elite polygyny. Greater solidarity between classes is a big advantage in

competition among states. Soldiers and citizens are more likely to identify

with, and to support, leaders who appear to follow the general moral rules

regarding legitimate access to women. This might have been an important source

of Greek and Roman advantages over their polygynous opponents. However, once

monogamy became sanctified by the religion of the European West, it became part

of the cultural package that European colonialism imposed on most of the rest

of the world. So economic and military power, as well as possible functional

advantages must be an important part of the explanation of the spread of SIUM.

And, once a global moral order has emerged, emulation of global modernity also

becomes a factor. China was never a colony, but the Peoples Republic made

polygyny illegal in 1955. Laws prohibiting polygyny were adopted in 1880

in Japan as part of the modernization effort that was the Meiji Restoration. Post-colonial

India made polygyny illegal in 1953 (Henrich et al 2012:

657). Therefore, the global spread of monogamy was a matter of comparative

advantage in warfare, imposition by the victors and emulation. This is relevant

for our examination of othering because class relations within polities are

part of othering and because the expansion of polities and the rise of the West

has produced convergence on a global moral order in which cannibalism, ritual

human sacrifice and polygyny are proscribed. This reduces the cultural

differences upon which distant othering is usually based.

The rise of the world religions[8] during and after the

Axial Age[9] display the

interaction between social movements and forms of governance. World religions

in our sense separate the moral order from kinship, allowing for and

encouraging the inclusion of non-kin into the circle of protection. This is the

expansion of human rights beyond the bounds of kinship and the expansion of

what Peter Turchin (2016a) calls “Ultrasociety”

– altruistic behavior among non-kin.

Marvin Harris (1977) pointed to the frequency of ritual cannibalism

practiced on enemies in systems of small scale polities. In small systems

non-kin are not really humans. They are enemy others that are not due any

positive reciprocity (Sahlins 1972). The question of who the humans are and who

are not the humans is important in all cultures. In small-scale polities the

distinction between “the people” and the non-people is usually a mixture of

kinship relations and familiarity with a language. The moral order applies to

the circle of the people and heavy othering sees the non-people as not fully

human.[10] When interaction

networks and polities expanded, important debates occurred as to whether newly

encountered peoples had souls, or not. The rise of what we currently call

humanity as a social construction was a long slow, back and forth and uneven

process that continues in the current struggle over citizenship.

World

religions locate great agency in the individual person even if it is only the

right to declare obedience. To become a

member of the moral order a convert must confess and proclaim belief in the

godhead. This is the act of an individual person. One’s own action is required.

Non-world religions usually tie membership to one’s birth parents. Salvation is

also a further democratization of the afterlife. Now the masses too may go to heaven or become

enlightened.

Marvin

Harris (1977) contend that the rise of world religions was functional for

expanding empires because they included the conquered populations within the

moral order of the conquerors. This proscribed cannibalism and reduced the

amount of resistance mounted by prospective conquerees.

The king makes you pay tribute and taxes, but he will not eat you. Most world

religions began as social movements from the semiperiphery

or the periphery (Bactria, Palestine) that were eventually adopted by the

emperors. Prophets and charismatic leaders mobilized cadres who spread the word

orally and with written documents. Sects and communities of believers were

organized, eventually producing formally structure churches. Older institutions

resisted, often repressing the new movements, but they continue to spread, in

some cases becoming conquering armies, and in other cases becoming adopted by

kings and emperors. Some of the world

religions were monotheistic, but others had no godhead at all except the path

to enlightenment. Peter Turchin’s (2016a: Chapter 9) depiction of the rise of the

world religions during the Axial Age focusses on the importance these moral

orders had for the construction of legitimate authority. The king and even the emperor were supposed

to also obey the religious commandments, at least in theory. This gave the

conquered a claim to membership in the moral community and provided a basis for

claims against the authorities if they were violating the rules. Turchin mentions that monotheism puts God above the

Emperor, but in China the same function was performed by the idea of the

mandate of heaven without a daddy in the sky. These religions often include a

large dollop of magical wishful thinking that gives hope to the downtrodden,

such as the promise of immortality.

There

is a well-developed and convincing literature on early Christianity as a social

movement (Blasi 1988; Stark 1996; Mitchell, Young and Bowie 2006). The

interesting thing already mentioned is world-systemic context of the origin of

the movement. Christ and his followers emerged in a context of a powerful Roman

colonialism in which the colonized peoples were faced with overwhelming force.

The ideology of individual salvation and rendering unto Caesar what is

Caesar’s, with concentration on the rewards of life after death was a powerful

medicine for those who faced a mighty Roman imperialism. Paul’s mission to

other colonized peoples and the delinking of salvation from ethnic origin was a

recipe that allowed the movement to spread back to the poor peoples of the

core. And eventually it was adopted by the Roman emperors themselves as a

universalistic ideology that could serve as legitimation for a multi-ethnic

empire. The prince of peace and salvation ironically proved to be a fine

motivator for later imperial projects such as the reconquest of Spain from the

Moors and the conquest of Mesoamerica and the Andes (Padden 1970). And as Cora Dubois (2007:116) has

said, it also worked for the conquered as a way for them to survive

psychologically and to adapt to a world in which their indigenous lifeways were

coming to an end (see Chase-Dunn’s discussion on “revitalization movements”).[11]

Another interesting characteristic

of early Christianity is that it was primarily an identity movement. The early

Christians did not propose to change the larger social or political order

(Blasi 1988). They simply wanted the freedom to be allowed to have dinner

together in Christ’s name. Repression of the movement by authorities who saw

this as a violation of religious propriety was a driving force in the formation

of the early Christian communities.

Hinduism

and Confucianism are not very proselytizing but they both spread successfully

because they provided a new justification for hierarchy and

state-formation. The spread of Hinduism

to mainland and island Southeast Asia occurred because its notion of the

god-king (deva-raja) provided a useful ideology for the centralization of state

power in a context of smaller contending polities (Wheatley 1975). Confucianism

provided a different justification for state power based on the notion of the

mandate of heaven and it spread from its original heartland to the rest of

China and Korea.

East

Asia also saw periodic eruptions of popular heterodox religious movements. Mass

heterodox movements are known to have been a recurrent feature of East Asian

dynastic cycles (Anderson 2019). During

a period of peasant landlessness during the Han dynasty large numbers of poor

people were drawn to worship the Queen Mother of the West who grew longevity

peaches that, once eaten, made people immortal (Hill 2015). The Queen Mother

lived in a mythical palace on a mountain somewhere in the West. This idea seems

to have been present as early as the Shang Dynasty, but recurrent eruptions of

the worship of the Queen Mother corresponded with periods in which there were

large numbers of landless peasants. The attraction of stressed masses, to “pie

in the sky when you die” reoccurs in world history.

The world religions developed

important new forms of individualism and new kinds of collective solidarity

that legitimated and facilitated larger empires and trade networks. These were

important steps on the way to modern individualism and human rights.

Chinese and Japanese

Distant Othering

The Chinese are famous for

their low opinion of “barbarians,” but, as usual, the story is more

complex. Early groups now called

“barbarians” (or the Chinese equivalent) were called by specific ethnic terms

that do not appear to have been particularly pejorative at the time. They were simply the names of the

groups. Most were neighbors and thus

often enemies, and their lifestyles were judged negatively, but they were not

quite as uncouth and loathsome as the English word suggests. The literature from the Warring States period

and later Han Dynasty histories refers to the Rong and Di in the north and

northwest, the Qiang in the west, the Koreans in the

east, and the Yue in the south. The Qiang and of course the Koreans are still with us. The Rong and Di were early conquered and

assimilated, and we have no idea what languages they spoke. The “Hundred Yue” were a diverse group,

speaking a wide range of languages including Tai, Hmong, Mien, and Vietnamese

(“Viet” is the Vietnamese pronunciation of “Yue”). They were judged negatively in proportion to

how different their cultures were from the Chinese. Unassimilated ones were

“raw” barbarians, Sinicized ones were “cooked.”

In the Han Dynasty, the Xiongnu

state arose in Mongolia and conquered southward, taking a large slice of

northwest China and menacing the entire country. They were the first of many steppe empires to

attack China’s frontiers. China’s

attitude toward them were more negative and they were viewed as the other. The

Chinese described them as wandering nomads, “people of the mutton-reeking

tents,” and other unflattering stereotypes.

A whole literary tradition developed from those stuck among the supposed

uncouth nomads, whether as prisoners, as brides, or as traders.

Over time, and usually through conquest, northwest

Chinese grew accustomed to steppe ways, and were laughed at by other Chinese,

who saw them as sunken into barbarism with their mutton, yogurt, kumys (fermented mares’ milk), and rough clothing suitable

for horse-riding (Anderson 1988, 2014).

The steppe nomads developed a low opinion of settled

people: slothful, weak, degenerate, eating soft foods that weakened them. This stereotype they carried with them into

Central Asia, where they attacked Iranic societies,

only to learn quickly that Iranians could fight hard whether settled or

not. A steady drift of Turkic steppe

people settling in towns and cities complicated the picture.

Once most Yue were conquered and assimilated into south

China, Chinese began to regard southeast Asians in an increasingly slighting

way. Man and fan became more

prejudicial terms for foreigners, especially southern ones. The Europeans were assimilated to this

slot. Famous in English colonial days in

Hong Kong and southeast Asia was the Cantonese insult fan kuai lou (Mandarin

fan gueizi),

literally “foreign ghost person” but usually translated “foreign devil.” However, fan

was also continually used as a simple nonjudgmental word for “foreign.”

Quite separate and distinct are the Chinese myths of the ye lang, “wild

man.” This is the Chinese version of the

Tibetan yeti. Both are local forms of the universal

human belief in wild, hairy, humanoid creatures that do not speak but are

powerful and wily—in short, “savages” of the “wodewose”

form. They most likely represent local

stories inspired by bears, monkeys, or memories of the orangutan (once native

to China). In Tibet, hairs and

footprints of “yeti” are often found,

and so far, have invariably turned out to be from bears. Unlike even the rawest of raw barbarians, the

ye lang and

yeti are not considered to be fully

human.

The Japanese in early times competed with the

Emishi (presumably related or like the Ainu) and judged them harshly as uncouth

and uncultured sorts—true barbarians.

They continued through time to regard outsiders as frightening,

uncultured, and unpleasant. As usual,

this was most true of their immediate neighbors, especially the Koreans. The Chinese were greatly respected. Truly strange aliens, the Europeans, suddenly

and mysteriously appeared in the 16th century, and were widely

distrusted—not without reason, since the Portuguese soon started to plot

invasion. This led to a closed,

xenophobic mindset that dominated well into the late 20th century.

It is often claimed that racism is a

modern phenomenon, and certainly if we define it as differences among humans

regarding genetic makeup then it is. Genes are a recent discovery, but earlier

ideas about blood and phylogenetic differences in skin color, facial features,

hair color and texture, etc. have all been used in distant othering. Cedric

Robinson (1983) found evidence of white racism toward Africans in medieval

Europe, thus concluding that racism existed before European colonialism and the

predominance of capitalism. Still, John Craig Venter, who helped mapped the

human genome has argued that “the concept of race has no genetic or scientific

basis; and… there is no way to tell one ethnicity from another in the five

Celera genomes” (Venter 2001: 317) and “skin colour

as a surrogate for race is a social concept, not a scientific one” (BBC News

2007) (also, see Fields and Fields 2014 Racecraft).

The modern story of racism focusses on

white racism and the non-white peoples of lands that were colonized by the

Europeans. Whiteness itself was invented

in this process. And the categorization of non-white peoples into different,

and inferior races was a complicated process. From the perspective of distant

othering this was the construction of superior and inferior identities to

justify genocide and exploitation. But

the exact terms of the constructions of racial hierarchy took some interesting

turns. One of the most important was a dispute in 16th century Spain

about whether “Indians” (indigenous peoples of North and South America) had

souls. Bartolome de las Casas, a Spanish priest, contended that the Indians did

have souls and were fully human. He opposed slavery and the encomienda and is

seen as a progenitor of the human rights movement.

Regarding the effects of racist

slavery on the slaves and slave owners Toni Morrison (2017) uses several

examples to demonstrate how sadistic and morally depraved slave owners

(including the wives) were, while claiming the savagery of the Africans. The

most compelling examples come from the writings of Thomas Thistlewood

who documents the repeated rapes of African women in the same way he documents

his household management details. It is cold, removed and written with no

emotion, even making a notation about whether he had an orgasm (see Burnard

2004 for a collection of Thistlewood’s writings).

Another appalling example was from The

History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, written from the slave's perspective

(Prince, 1831). In it, is a description the wife of a slave owner beating Mary

for a broken vase which Mary was not at fault for breaking. She beats Mary

until she is exhausted, takes a break, and gets back to beating Mary. Morrison

(2017:29) writes, "how hard they work to define the slave as inhuman,

savage, when in fact the definition of the inhuman describes overwhelmingly the

punisher." [12]

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker (2000)

contend that the connection between race and slavery emerged in England during

the 17th century as Africa became the main source of slaves for New

World plantations. Before this, slavery

was a legal status that could be held by any person, not just Africans. The

story of the incorporation of Africa into the expanding Europe-centered

world-system is relevant for our study of distant othering. Africa was an external arena, largely

disconnected from the emerging modern world-system in the long 16th

century. The plantation complex was an

organizational structure based on the Roman latifundium in which slave labor

was used to produce agricultural commodities. Its use in the production of

sugar cane began on islands in the Mediterranean and then spread to islands in

the Atlantic adjacent to Africa and then to the Americas (Curtin 1990). The Atlantic slave trade arose to supply

labor to the plantation economies of the European colonies in the Americas.

Africa was a source of labor power obtained by buying slaves that were captives

of African polities specializing in capturing and selling people (Rodney 1970;

1974). This was a phase of plunder and parasitism that had severe consequences

for African societies and produced a racialize core/periphery hierarchy. Most of Africa was colonized by European

states only in the last quarter of the 19th century. At the Berlin

Conference on Africa in 1884 the European states parceled out Africa. This was

an effort by the British to peacefully incorporate rising Germany into a world

economy in which Britain was still the hegemon. But it gave the Europeans a

stake in colonial economies within Africa and transitioned from plunder to

parasitism (Wallerstein 1986).

There is a huge gulf between the

traditional rivalry of the French and English –fighting a lot but seeing each

other as fully human, and frequently shifting residence, intermarrying, and

admiring each other’s achievements –and the extreme racism seen in the

enslavement of Africans and Native Americans by European colonists. Most

othering is somewhere in between. There is a vast range, with societies

distributed along a complex gradient.

The Rise of Secular

Humanism and Science

Humanism and science are core

ideologies of modernity. Usually these are understood as products of the

European Enlightenment but they both have roots in the world religions of the

Axial Age discussed above. And secular humanism was much more central to both

Buddhism and Confucianism than it was to the daddy in the sky religions of the

West. As we have already mentioned,

world religions make a crucial step toward individualism when they separate

kinship from the moral order by erecting a moral community in which an

individual can become a member by means of confession or self-declaration.

Locating this power at the level of the individual person is the beginning of

modern individualism. The world

religions all did this. The rise of

humanism also raises the issue of how human nature is conceived and where the

boundaries between the human and the not human are placed. These boundaries

continued to evolve as polities and trade networks got larger.

Secular humanism and science are

still challenged by religious fundamentalism, and these are sometimes

counter-hegemonic ideologies that mobilize resistance to contemporary global

institutions. Though religious fundamentalism

is a recurrent phenomenon, it is notable that it did not play a very important

counter-hegemonic role in the world revolutions of the past. However, since the

demise of the Soviet Union and the secular socialist and communist movements of

the 20th century, religious fundamentalism has taken an increasingly

counter-hegemonic role (Wallerstein 2008; Moghadam (2009; 2012).

Nationalism is perhaps the most

important collective identity in the contemporary world-system. Ethnic

identities have long emerged and ethnogenesis has been an important process

since the Stone Age (Barth 1969; Hall 1984).

Benedict Anderson’s (1991) important study of nation-building focusses

on the importance of literacy and the printing press as communications

technologies that facilitated the growth of what he called “imagined

communities.”[13]

Nationalism is constructed in different ways, and its strength varies across

countries and over time within countries.

Civic nationalism is based on shared histories, traditions and customs.

Racial nationalism is based on beliefs about hereditary similarities.

Patriotism is a sentiment that motivates cooperation and sacrifice for the

nation. As with other collective identities, rituals, symbols, songs, political

constitutions and historical memories are important for producing and

reproducing membership. The solidarity produced by nationalism is a vital

component of the ability of countries to compete with one another, especially

militarily.

Furthermore, the deeply

institutionalized nature of nationalism is an important feature of global

society that demonstrates the power of socially constructed solidarities that

are beyond the scope of genetically produced altruism. Nationalism is viewed as

part of the global moral order but so is individualism, which justifies a

degree of distance from nationalism and patriotism. Individuals are supposed to

be loyal to their nation, but they are also supposed to be loyal to their

families and to themselves. Hyper-nationalism

seems to reemerge in periods in which the global political economy is in

crisis, as in the first half of the 20th century and the early

decades of the 21st century.

Fascism in the 20th century was primarily organized around

hyper-nationalism.[14] It can be understood as a reaction against

internationalism and global cosmopolitanism, that gains strength when there is

economic and political turmoil. People go back to earlier collective identities

when they feel threatened or afraid.

The abolition of slavery and

serfdom, decolonization and the extension of citizenship have been important

modern processes that have had large consequences for both within-society and

between society othering. The French Revolution was a blow against monarchy and

the divine right of kings and for the legitimation of governance from below ---

popular sovereignty. The extension of

the franchise to men of no property and to women and the abolition of legal

slavery were important developments in the further institutionalization of

human rights. These developments were made possible by social movements from

below that were mobilized by elites that were competing with other elites, and

by energy regime transitions that reduced the reliance on unskilled human

labor. The core/periphery hierarchy has

not been abolished and global inequality is still huge, but neocolonialism is

still an improvement over colonialism.

Individualism is another pillar of

modernity. Possessive, honorific,

socialist and anarchist individualism are forms that vie with one another in the

context of social changes that increasingly locate legitimacy and

responsibility at the level of the person (Meyer 2009). Beck and Beck (2002)

call the organizational and cultural features of this transition

“individualization.” It corresponds with

the reorganization of work and occupations that has produced the replacement of

the proletariat with the precariat (Standing 2011; 2014; Kalleberg

2009). The human rights movement

supports the idea that individuals are unique and should be empowered. This strong

emphasis on individual freedom has been an important legitimation for

capitalism, but it does not follow that individualism should be attacked by

those who wish to organize a more humane and less ecologically destructive form

of human society. Human rights and

individualism are enemies of distant othering.

The current wave of anti-immigrant

sentiment and racism can be understood as a reactionary response to neoliberal

globalization that scape-goats certain people for problems caused by neoliberal

capitalism. Distant othering is back in

the form of white nationalism, shithole countries, terrorists and MS-13

animals. Alternative forms of progressive cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism

are in retreat, as is neoliberal globalization. We are entering a period of

deglobalization corresponding with U.S. hegemonic decline. But the long and uneven upward trend toward

the extension of citizenship and humanism is likely to continue after the

current downturn has had its day.

What about the future of distant

othering and racism? Transhumanism, cyborgs and machines that are smarter than

humans are going to provide opportunities for more distant othering in the

future. And scientific racism is still around. Herrnstein and Murray (1994) are

still infamous. More recently we have the work of Cochrane and Harpending (2009) who summarize the evidence from the

HAPMAP study that shows that biological change among humans has speeded up over

the past 10,000 years contrary to what most social scientists believe, but then

they go on to speculate about how this could account for uneven development of

different world regions and inequalities among contemporary groups. The

implication is that existing inequalities have been caused by genetically-based

differences in intelligence. The winners

really are smarter and the losers are getting what they deserve!!.

Fields and Fields (2014) call it by its correct name – Racecraft, a jedi

mind trick used to justify exploitative, repressive action. Color-blind racism

and the idea of racial formations are mainly reformulations of the idea of

structural racism – a focus on unequal outcomes across racial groups that does

not tell us much about the causes these outcomes.

While we are in the midst of a downturn in the expansion and institutionalization

of human rights, the long-run evolutionary trend has been toward more inclusive

solidarities and the extension of citizenship to the whole human species. The

recent rise of hate crimes and atrocities that are occurring around gender,

race, ethnicity and nationalism are repugnant, but the idea of status threat

implies that these signal that the status characteristics organized around

gender and race are changing, and in the long run gender and racial equality

will become more accepted and institutionalized. While racial fears are still used by

politicians to mobilize support for reactionary actions and policies, we think

that humanity will construct a democratic and collectively rational global

commonwealth in which conflicts can be resolved peacefully. This is by no means

inevitable because we have developed the technical capability to destroy

ourselves. This could happen, but unless it is very thorough, the humans will

survive and will eventually get back to something like the situation we are now

in. We are hopeful that the 21st century will not be as bad as the

first half of the 20th century was and that the 22nd

century will be much better. The long run trajectory of distant othering gives

us hope.

Bibliography

Algaze, Guillermo 1989

"The Uruk Expansion: Cross-Cultural Exchange as a Factor in Early

Mesopotamian Civilization."

Current Anthropology 30:5:(December):571-608.

_____. 1993. The Uruk World

System: The Dynamics of Expansion of

Early Mesopotamian Civilization.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Almeida, Paul and Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2019 Global Change and Social

Movements. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University

Press.

Alvarez, Rebecca 2019

Vigilante Gender Violence and the Sociocultural

Evolution of Gender Inequality

Amin, Samir 1980 Class and Nation, Historically and in the

Current Crisis. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Anderson, Benedict 1991 Imagined Communities. London: Verso

Anderson,

E. N. 1988. The Food of China. New Haven:

Yale University Press.

_____________ 2005 “The Wodewose” http://www.krazykioti.com/articles/the-wodewose/

______________2014. Food

and Environment in Early and Medieval China. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania

Press.

_____________ and Barbara A. Anderson

2017 Halting Genocide in America.

Anderson, E. N. and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2005 “The Rise

and Fall of Great Powers” in

Christopher Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The

Historical Evolution of World-Systems. London:

Palgrave.

Baker, Lee D. 1998 From

Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the

Construction of Race, 1896-1954.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Balibar,

Etienne and Immanuel Wallerstein 1991 Race,

Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities. London:

Verso.

Barth,

Frederick. 1969. Ethnic