21st Century Deglobalization and the Struggle for

Global Justice in the World Revolution of 20xx

![]() Christopher Chase-Dunn

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

A revised version is Forthcoming in the Routledge Handbook on Transformative Global Studies; Editors: S. A. Hamed Hosseini, Barry K. Gills and James Goodman

v. 12-9-2019 9010 words

This is IROWS Working Paper #136 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows136/irows136.htm

Keywords: globalization, deglobalization, world-system, world revolutions, world politics. the New Global Left, global capitalism, neoliberalism, modes of accumulation, sociocultural evolution, global governance, hegemony

Abstract:

Structural globalization has been both a cycle and an upward trend as periods of greater global integration have been followed by periods of deglobalization on a stair-step toward the greater connectedness of humanity. In the current period the world-system may be entering entered another phase of structural deglobalization as the contradictions of capitalist neoliberalism have provoked different kinds of anti-globalization populism and trade wars. This plateauing and downturn in economic connectedness is occurring in the context of U.S. hegemonic decline and the emergence of a more multipolar power configuration among states. And the combination of greater communications connectivity and greater awareness of North/South inequalities, as well as destabilizing conflicts and climate change in the Global South, have provoked waves of refugee migrations and reactions against immigrants. The result is a period of chaos that is similar in some ways with what occurred in the first half of the 20th century, but also different. This chapter considers ways in which progressive forces might come together in the 21st century to bring about a more egalitarian, democratic and sustainable global commonwealth.

This chapter briefly summarizes the continuities and transformations of systemic modes of accumulation in world historical and evolutionary perspective since the Stone Age. It also considers the prospects for systemic transformation in the next several decades. It describes and discusses the contemporary network of global anti-systemic social movements that are seeking to transform the capitalist world-system into a more humane, sustainable and egalitarian civilization and how the current crisis is affecting the network of movements and regimes. It discusses the rise and demise of the Pink Tide populist regimes in Latin America, the World Social Forum, the Arab Spring and the anti-austerity movements in Europe and the United States as well as the revival of economic nationalism, anti-immigrant sentiments, right-wing populism and neofascist movements and authoritarian regimes. It examines how the New Global Left is like, and different from, earlier constellations of progressive movements in earlier world revolutions. The point is to provide a comparative and evolutionary framework that can discern what is new about the current global situation and inform progressive collectively rational responses. And the chapter discusses the long-run trajectory of global economic integration (waves of structural globalization and deglobalization) and how the world-system is now be headed into another period of structural deglobalization and challenges to the neoliberal globalization project.

Hall and Chase-Dunn (2006; see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997) have modified the concepts developed by the scholars of the modern world-system to construct a theoretical perspective for comparing the modern system with earlier regional world-systems. This is called the comparative evolutionary world-systems perspective (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014). The main idea is that sociocultural evolution can only be explained if polities are seen to have been in important interaction with each other since the Paleolithic Age. Hall and Chase-Dunn (2006) propose a general model of the continuing causes of the evolution of technology and hierarchy within polities and in linked systems of polities (world-systems). This is called the iteration model and it is driven by population pressures interacting with environmental degradation and interpolity conflict. This iteration model depicts basic causal forces that were operating in the Stone Age and that continue to operate in the contemporary global system (see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 6; Fletcher et al 2011). These are the continuities.

As regional world-systems became spatially larger and the polities within them grew and became more internally hierarchical, interpolity relations also became more hierarchical because new means of extracting resources from distant peoples were invented. Thus, did core/periphery hierarchies emerge out of interpolity systems that were based on more equal exchange. Semiperipherality is the position of some of the polities in a core/periphery hierarchy. Some of the polities that were in semiperipheral positions became the agents that formed larger chiefdoms, states and empires by means of conquest (semiperipheral marcher polities), and some specialized trading states in between the tributary empires promoted production for exchange in the regions in which they operated. So, both the spatial and demographic scale of political organization and the spatial scale of trade networks were expanded by semiperipheral polities, eventually leading to the global system in which we now live.

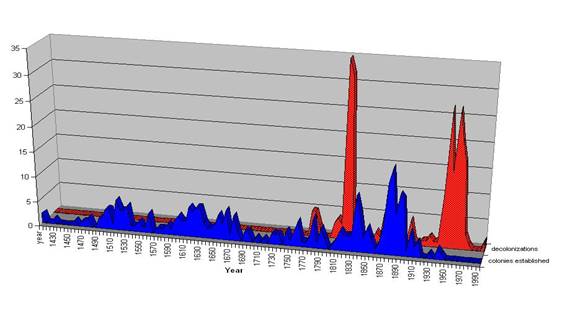

The modern world-system came into being when a formerly peripheral and then semiperipheral region (Europe) developed an internal core of capitalist states that were eventually able to dominate the polities of all the other regions of the Earth. This Europe-centered system was the first one in which capitalism became the predominant mode of accumulation, though semiperipheral capitalist city-states had existed since the Bronze Age in the spaces between the tributary empires. The Europe-centered system expanded in a series of waves of colonization and incorporation (See Figure 1). Commodification in Europe expanded, evolved and deepened in waves since the thirteenth century, which is why historians disagree about when capitalism became the predominant mode. Since the fifteenth century the modern system has seen four periods of hegemony in which leadership in the development of capitalism was taken to new levels. The first such period was led by a coalition between Genoese finance capitalists and the Portuguese crown (Wallerstein 2011[1974]; Arrighi, 1994). After that the hegemons have been single nation-states: the Dutch in the seventeenth century, the British in the nineteenth century and the United States in the twentieth century (Wallerstein, 1984a). Europe itself, and all four of the modern hegemons, were former semiperipheries that first rose to core status and then to hegemony.

Figure 1: Waves of Colonization and Decolonization Since 1400 - Number of colonies established and number of decolonizations (Source: Henige (1970))

In between these periods of hegemony were periods of hegemonic rivalry in which several contenders strove for global power. The core of the modern world-system has remained multicentric, meaning that several sovereign states ally and compete with one another. Earlier regional world-systems sometimes experienced a period of core-wide empire in which a single empire became so large that there were no serious contenders for predominance. This did not happen in the modern world-system until the United States became the single super-power following the demise of the Soviet Union in 1989.

The sequence of hegemonies can be understood as the evolution of global governance in the modern system. The interstate system as institutionalized at the Peace Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 is still a fundamental institutional structure of the polity of the modern system. The system of theoretically sovereign states was expanded to include the peripheral regions in two large waves of decolonization (see Figure 1), eventually resulting in a situation in which the whole modern system became composed of sovereign national states. East Asia was incorporated into this system in the nineteenth century, though aspects of the earlier East Asian tribute-trade state system were not completely obliterated by that incorporation (Hamashita, 2003).

Each of the hegemonies was larger as a proportion of the whole system than the earlier one had been. And each developed the institutions of economic and political-military control by which it led the larger system such that capitalism increasingly deepened its penetration of all the areas of the Earth. And after the Napoleonic Wars in which Britain finally defeated its main competitor, France, global political institutions began to emerge over the tops of the international system of national states. The first proto-world-government was the Concert of Europe, a fragile flower that wilted when its main proponents, Britain and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, disagreed about how to handle the world revolution of 1848. The Concert was followed by the League of Nations and then by the United Nations and the Bretton Woods international financial institutions (The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and eventually the World Trade Organization).

The political globalization evident in the trajectory of global governance evolved because the powers that be were in heavy contention with one another for geopolitical power and for economic resources, but also because resistance emerged within the polities of the core and in the regions of the non-core. The series of hegemonies, waves of colonial expansion and decolonization (see Figure 1) and the emergence of a proto-world-state occurred as the global elites tried to compete with one another and to contain resistance from below. I have already mentioned the waves of decolonization, which extended the European state system to the Global South.[1] Other important forces of resistance were slave revolts, the labor movement, the extension of citizenship to men of no property, the women’s movement, and other associated rebellions and social movements.

These movements affected the evolution of global governance in part because the rebellions often clustered together in time, forming what have been called “world revolutions” (Arrighi et al., 1989). The Protestant Reformation in Europe was an early instance that played a huge role in the rise of the Dutch hegemony. The French Revolution of 1789 was linked in time with the American and Haitian revolts. The 1848 rebellion in Europe was both synchronous with the Taiping Rebellion in China and was linked with it by the diffusion of ideas, as it was also linked with several new Christian sects that emerged in the United States. 1917 was the year of the Bolsheviks in Russia, but also the same decade saw the Chinese Nationalist revolt, the Mexican Revolution, the Arab Revolt and the General Strike in Seattle led by the Industrial Workers of the World in the United States. 1954 was the last wave of national liberation movements and the formation of a “non-aligned” coalition of new nations in the Global South at the Bandung Conference. 1968 was a revolt of students, young people and racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S., Europe, Latin America and Red Guards in China. 1989 was mainly in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, but China embarked on a form of state capitalist neoliberalism and important lessons about the value of civil rights beyond justification for capitalist democracy were learned by an emergent global civil society (Arrighi et al., 1989; Martin 2003).

The current world revolution of 20xx (Chase-Dunn and Niemeyer, 2009) will be discussed as a global countermovement in this chapter. The big idea here is that the evolution of capitalism and of global governance is importantly a response to resistance and rebellions from below. This has been true in the past and is likely to continue to be true in the future. Boswell and Chase-Dunn (2000) contended that capitalism and socialism have dialectically interacted with one another in a positive feedback loop like a spiral. Labor and socialist movements were obviously a reaction to capitalist industrialization, but also the U.S. New Deal, hegemony and the post-World War II global institutions were importantly spurred on by the World Revolution of 1917 and the waves of decolonization.

The important book on world revolutions by Giovanni Arrighi, Terence Hopkins and Immanuel Wallerstein (1989) pointed out that revolutionaries rarely attain their demands immediately. Rather what happens is that “enlightened conservatives” implement the demands of an earlier revolution in order to cool out the challenges of a current world revolution. This is the way in which world revolutions have produced the evolution of global governance and the systemic cycles of accumulation.

Transformations Between Modes of Accumulation

If we take a sociocultural evolution perspective on world-systems there have been two qualitative transformations in the predominant logics of sociocultural production and reproduction (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2014). The kin-based modes of accumulation in which small-scale human societies mobilized social labor based on normative consensus about family obligations was the first mode of accumulation. It was predominant in small-scale world-systems since the emergence of modern humanity and cultural integration based on linguistic abstractions from about 300,000 years ago until the emergence of states in Mesopotamia in the early Bronze Age. With early state formation a new logic of social production and reproduction became predominate in regional world-systems. This was based on institutionalize coercion and Marxists call this the tributary modes of production. This logic of accumulation became predominant in the Mesopotamian world-system in about 3000 BCE when city-states emerged in the valley of the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers in what is now Iraq. Other systems of this kind emerged later in Egypt, the Indus River valley, the valley of the Huang He (Yellow) river in what is now China, Mesoamerica and the Andes. Accumulation of wealth in the tributary systems was mainly based on the ability of states and empires to extract taxes and tribute. Capitalism is based on a different kind of accumulation. It’s wealth came from and comes from the extraction of surplus profits from commodity production and trade. This requires an institutional context that includes money and production for exchange. States that specialize in trade emerged in the Bronze Age. Dilmun carried on a trade between Mesopotamia and the Indus River valley. Semiperipheral capitalist city-states were specialists in capitalism in the interstices of tributary world-systems for thousands of years before capitalism became the predominant logic of accumulation in the European world-system in the long sixteenth century.[2]

Here is the point. The kin-based modes of accumulation were predominant in all small-scale world-systems for at least 100,000 years or more (depending on when we designate the emergence of modern humans who were using abstractions to constitute a culturally constructed moral order). The tributary modes of accumulation first became predominant in a world-system only about 7500 years ago in Mesopotamia and this mode of accumulation became predominant much later in most world regions. The capitalist mode of accumulation became predominant in the Europe-centered world-system from 600 to 400 years ago. So, the point is this is still a young mode of accumulation in world historical and evolutionary comparative perspective (but see below).

For Immanuel Wallerstein (2011 [1974]), capitalism became a predominant logic of social reproduction in the long sixteenth century (1450-1640), grew larger in a series of cycles and upward trends, and is now nearing “asymptotes” (ceilings) as some of its trends create problems that it cannot solve. Thus, for Wallerstein the world-system became capitalist and then it expanded until it became completely global, and now it is coming to face a big crisis because certain long-term trends cannot be accommodated within the logic of capitalism (Wallerstein, 2003). Wallerstein’s evolutionary transformations come at the beginning and at the end. There is a focus on expansion and deepening as well as cycles and trends, but no periodization of world-system evolutionary stages of capitalism (Chase-Dunn 1998: Chapter 3). This is very different from both Arrighi’s depiction of successive (and overlapping) systemic cycles of accumulation (SCAs) and from the older Marxist stage theories of national development. Wallerstein’s emphasis is on the emergence and demise of “historical systems” with capitalism defined as “ceaseless accumulation”. Some of the actors change positions but the system is basically the same as it gets larger. Its internal contradictions will eventually reach limits, and these limits are thought to be approaching within the next five decades.

According to Wallerstein (2003) the three long-term upward trends (ceiling effects) that capitalism cannot manage are: 1. the long-term rise of real wages; 2. the long-term costs of material inputs; and 3. rising taxes.

All three upward trends cause the average rate of profit to fall. Capitalists devise strategies for combating these trends (automation, capital flight, job blackmail, attacks on the welfare state and unions), but they cannot really stop them in the long run. Deindustrialization in one place leads to industrialization and the emergence of labor movements somewhere else (Silver, 2003). The falling rate of profit means that capitalism as a logic of accumulation will face an irreconcilable structural crisis during the next 50 years, and some other system will emerge. Wallerstein called the next five decades “The Age of Transition.”

Wallerstein saw recent losses by labor unions and the poor as temporary. He assumed that workers would eventually figure out how to protect themselves against globalized market forces and the “race to the bottom”. This may underestimate somewhat the difficulties of mobilizing effective labor organization in the era of globalized capitalism, but he was probably right in the long run. Global unions and political parties could give workers effective instruments for protecting their wages and working conditions from exploitation by global corporations if the North/South issues that divide workers could be overcome.

Wallerstein was intentionally vague (as was Marx) about the organizational nature of the new system that will replace capitalism, except that he was certain that it would no longer be capitalist. He saw the declining hegemony of the United States and the crisis of neoliberal global capitalism as strong signs that capitalism can no longer adjust to its systemic contradictions. He contended that world history has now entered a period of chaotic and unpredictable historical transformation. Out of this period of chaos a new and qualitatively different non-capitalist system would emerge. It might be an authoritarian (tributary) global state that preserves the privileges of the global elite or it could be an egalitarian system in which non-profit institutions serve communities (Wallerstein, 1998).

Stages of World Capitalist Development: Systemic Cycles of Accumulation

Giovanni Arrighi’s (1994) evolutionary account of “systemic cycles of accumulation” provides a more nuanced depiction of the structural history of capitalism over the past 500 years. Arrighi’s account is explicitly evolutionary, but rather than positing national stages of capitalism and looking for each country to go through them (as most of the older Marxists did), he posits somewhat overlapping global “systemic cycles of accumulation” in which finance capital and state power take on new forms and increasingly penetrate and organize the whole system. This was a big improvement over both Wallerstein’s world cycles and trends and the traditional Marxist national stages of capitalism.

Arrighi’s (1994, 2006) systemic cycles of accumulation are more different from one another than are Wallerstein’s cycles of expansion and contraction and upward secular trends. Arrighi (2006) also was more explicit about the differences between the current period of U.S. hegemonic decline and the decades at the end of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century when British hegemony was declining (see summary in Chase-Dunn and Lawrence 2011:147-151). The emphasis is less on the beginning and the end of the capitalist world-system and more on the emergence of new institutional forms of accumulation and the increasing incorporation of modes of control into the logic of capitalism. Arrighi (2006), taking a cue from Andre Gunder Frank (1998), saw the rise of China as portending a new systemic cycle of accumulation in which “market society” would eventually come to replace neoliberal finance capital as the leading institutional form in the next phase of world history. Arrighi did not posit a near-term end of capitalism and the emergence of another basic logic of social reproduction and accumulation. His analysis was more cognizant the “types of capitalism” and “multiple modernities” literature except that he was focusing the whole system rather than separate national societies.

Arrighi (2006) saw the development of market society in China as a consequence of the differences between the East Asian and Europe-centered systems before their merger in the 19th century, and as an outcome of the Chinese Revolution. His discussion of Adam Smith’s notions of societal control over finance capital suggests that the big problems with capitalism stem from allowing finance capital to run the show. His respect for the Chinese Communist Party’s model of development which attempts to spread the wealth and feed the people is suggestive in that it poses an alternative to rule by finance capital and is redolent of the “developmental state” model analyzed by Peter Evans (1979) in Brazil, Japan and Korea in which a professionalized technocratic elite directs investment decisions in ways that benefit the masses, though Arrighi did not suggest this comparison. The problem with seeing this model as the seed of a new systemic cycle of accumulation is that, as Arrighi acknowledged, it emerged under somewhat unusual conditions in some semiperipheral nation-states, but not in others, and may be rather difficult to replicate in other regions.

Wallerstein’s version was more millenarian. The old world was ending. The new world was beginning. Using imagery from complexity theory he supposed that in the coming systemic bifurcation what people do may be prefigurative and causal of the world to come. Wallerstein (1984b) also agreed with the analysis proposed by the students of the New Left in 1968 (and large numbers of activists in the current global justice movement) that the tactic of taking state power has been shown to be futile because of the disappointing outcomes of the World Revolution of 1917 and the national liberation movements (but see below). Arrighi suggests instead that capitalism will be able to reorganize and to take the rough edges off the neoliberal globalization project, and that this will occur as a result of the rise of China.

Structural Globalization and Deglobalization

Globalization is here understood to be two rather different things. Sometimes this word refers to the neoliberal globalization project -- a collection ideas and policies that emerged in the 1970s and spread across the world (Mc Michael 2017). But it also has been used to mean an increase in the degree of integration in the world-system. This is called structural globalization (Chase-Dunn 1999).

Regarding the question of whether the financial crisis of 2007-2008 and other crises are structural, signaling the beginning of a process of systemic transformation or just another transition to a new form of capitalism, it is relevant to examine recent trends in economic globalization. Is there yet any sign that the world economy has entered a new period of structural deglobalization of the kind that occurred in the first half of the twentieth century?

Immanuel Wallerstein contended that globalization in the sense of greater and greater economic and political interconnectedness has been occurring for five hundred years, and so there is little that is importantly new about the so-called stage of global capitalism that is alleged to have emerged in the last decades of the twentieth century (Robinson 2018).

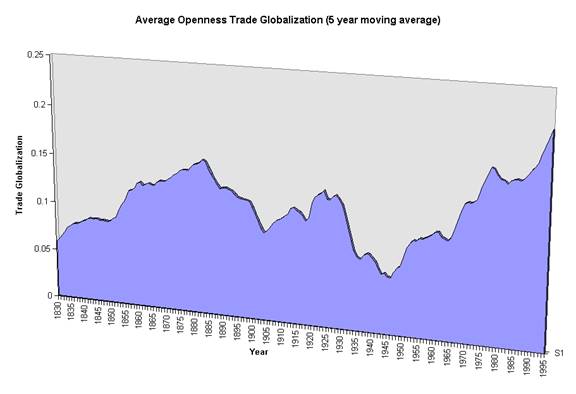

Well before the emergence of globalization in the popular consciousness, the world-system perspective focused on the world economy and the system of interacting polities, rather than on single national societies. Globalization, in the sense of the expansion and intensification of larger and larger economic, political, military and information networks, has been increasing for millennia, albeit unevenly and in waves. And globalization is both a cycle as a trend (see Figure 2.) The wave of global integration that has swept the world in the decades since World War II is best understood by studying its similarities and differences with the waves of international trade and foreign investment expansion that have occurred in earlier centuries, especially the last half of the nineteenth century.

William I. Robinson’s delineation of a new stage of global capitalism provides important insights about the degree to which the transnational capitalist class has been able to shape global governance in recent decades by repurposing national states to pursue the neoliberal program of privatization, etc, and the high level of transnational financial and production organization that has emerged. But Robinson’s emphasis on the uniqueness of the recent wave of globalization is partly based on his claim that before the emergence of the global capitalism in the last decades of the 20th century the world-system was composed of national economies that were largely autonomous from one another with regard to the circulation of capital (Robinson 2018:55) The world-system perspective contends that the circuits of capital have been organized as an axial division of labor linking the core with the non-core at least since the emergence of the Europe-centered world-system 500 years ago. Robinson is right to argue that globalization has gone to a new higher level of integration in the recent period, but he does not see that there were earlier waves of integration that were separated by troughs of deglobalization.

Figure 2: Average Openness Trade Globalization, 1830-1995 (Weighted) Source: Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer (2000)

The trade globalization series published in Chase-Dunn et al., (2000) shows the great nineteenth century wave of global trade integration, a short and volatile wave between 1900 and 1929, and the post-1945 upswing that is characterized as the “stage of global capitalism.” This indicates that globalization is both a cycle and a bumpy trend. There were significant periods of deglobalization in the late nineteenth century and in the first half of the twentieth century.

Figure 3 shows that there was a drop in the measure of trade globalization (the sum of global imports divided by global GDP) in 2008 and then a recovery but this indicator fell from 2012 to 2016 and then recovered in 2017. This may indicate that the world-system is entering another period of structural deglobalization, though this in not certain because there have been short-term downturns before that were followed by recoveries of the upward trend since 1945. If indeed we have entered another period of deglobalization this has implications for political strategies that assumed that structural globalization was going to continue increasing.

Wallerstein has insisted that U.S. hegemony is continuing to decline. He interpreted the U.S. unilateralism of the Bush administration as a repetition of the mistakes of earlier declining hegemons that attempted to substitute military superiority for economic comparative advantage (Wallerstein, 2003). Most of those who denied the notion of U.S. hegemonic decline during what Giovanni Arrighi (1994) called the “belle epoch” of financialization have now come around to Wallerstein’s position in the wake of the current global financial crisis. Wallerstein contended that once the world-system cycles and trends, and the game of musical chairs that is capitalist uneven development, are considered, the “new stage of global capitalism” does not seem that different from earlier periods.

World (1987)

18.221

Figure 3: Trade Globalization 1970–2017: World Imports as a Percentage of World GDP (Sources: Chase-Dunn et al. (2000); World Bank (2018)[3]

The updated series shows a steep decline in the level of global trade integration in 2009 followed by a recovery and then another decline until 2016 and then another recovery in 2017.[4]

The long-term upward trend in trade globalization has been bumpy, with occasional downturns like the one in the 1970s. But the downturns since 1945 have all been followed by upturns that restored the overall upward trend of trade globalization. Figure 2 shows the large decrease of trade globalization in the wake of the global financial meltdown of 2008. This was a 21% decrease from the previous year, the largest reversal in trade globalization since World War II. But the ratio of imports to global GDP increased again in 2017. The World Bank estimate for 2018 is not yet available. The question is whether or not the sharp decrease after the financial meltdown was the beginning of a new reversal in the long upward trend observed over the past half century or just another hiccup. It should be noted that this indicator of economic globalization has not yet reached the level that it had in 2008. Bond (2018), Van Bergeijk (2018) and Witt (2019) have argued that we are already in the midst of another wave of deglobalization.

The ratio of global investment flows to the size of the global economy provides additional evidence that the world economy may have entered another period of deglobalization (Figure 4).[5]

Figure 4: Investment Globalization 1970–2018: World Foreign Direct Investment Flows as a Percentage of World GDP: Source: World Bank (2019) World Development Indicators

The ratio of international investment flows to the global GDP took a dive in the late 1990’s, recovered and then took another dive in 2007, which was followed by a weak recovery and then another dive in 2018. We still want to find out what happened to trade globalization in 2018 and 2019, and to investment globalization in 2019. But the evidence so far is consistent with the idea that the world economy is indeed entering another period of deglobalization.

Some progressives may see this as an opportunity for the Global South. There has always been a tension within the New Global Left regarding antiglobalization versus the idea of an alternative progressive form of globalization. Samir Amin (1990) and Waldon Bello (2002) are important progressive advocates of deglobalization and delinking of the Global South from the Global North in order to protect against neo-imperialism and to make possible self-reliant and egalitarian development. Alter-globalization advocates an egalitarian world society that is integrated but without exploitation and domination. The alter-globalization project has been studied and advocated by Geoffrey Pleyers (2011) as an “uneasy convergence” of largely horizontalist autonomous and independent activist groups and more institutionalist actors like intellectuals and NGOs.

The World Revolution of 20xx

Recall the definition of world revolutions provided above – periods in world history in which rebellions, unrest and revolutions are breaking out in different regions of the world-system. The contemporary world revolution is like earlier ones, but also different. Our conceptualization of the New Global Left includes civil society entities: individuals, social movement organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), but also political parties and progressive national regimes.[6] In this chapter I discuss the relationships among the movements and the progressive populist regimes that have emerged in Latin America in recent decades, the Arab Spring that began in Tunisia in December of 2010, the anti-austerity and Occupy movements that emerged in 2011. I understand the Latin American “Pink Tide” regimes to be an important part of the New Global Left, though it is well-known that the relationships among the movements and the regimes are both supportive and contentious.

The boundaries of the progressive forces that have come together in the New Global Left are fuzzy and the process of inclusion and exclusion is ongoing (Santos, 2006). The rules of inclusion and exclusion that are contained in the Charter of the World Social Forum, though still debated, have not changed much since their formulation in 2001.[7]

The New Global Left has emerged as resistance to, and a critique of, global capitalism (Lindholm and Zuquete, 2010). It is a coalition of social movements that includes recent incarnations of the old social movements that emerged in the nineteenth century (labor, anarchism, (Aldecoa 2019) socialism, communism, feminism, environmentalism, peace, human rights) and movements that emerged in the world revolutions of 1968 and 1989 (queer rights, anti-corporate, fair trade, indigenous (Chase-Dunn et al 2019)) and even more recent movements such as the slow food/food rights, global justice/alterglobalization, antiglobalization, health-HIV and alternative media (Reese et al., 2008). The explicit focus on the Global South and global justice is somewhat like some earlier instances of the Global Left, especially the Communist International, the Bandung Conference and the anticolonial movements. The New Global Left contains remnants and reconfigured elements of earlier Global Lefts, but it is a qualitatively different constellation of forces because: 1. there are new elements, 2. the old movements have been reshaped, and 3. a new technology (the Internet) is being used to mobilize protests in real time and to try to resolve North/South issues within movements and contradictions among movements.

There has also been a learning process in which the earlier successes and failures of the Global Left are being considered in order to not repeat the mistakes of the past. Many social movements have reacted to the neoliberal globalization project by going transnational to meet the challenges that are obviously not local or national (Reitan 2007). But some movements, especially those composing the Arab Spring, are focused mainly on regime change at home. The relations within the family of antisystemic movements and among the Latin American Pink Tide populist regimes are both cooperative and competitive. The issues that divide potential allies need to be brought out into the open and analyzed in order that progressive global collective action may become more effective.

Arab Spring, Pink Tide and Deglobalization

The global political, economic, and demographic situation has evolved in ways that challenge some of the assumptions that were made during the rise of the global justice movement and that require adjustments in the analyses, strategies, and tactics of progressive social movements. The Arab Spring, the Latin American Pink Tide, the Indignados in Spain, and the rise of New Leftist social media-based parties in Spain (Podemos) Italy and in Greece and the spike in mass protests in 2011 and 2012 were interpreted as the heating up of a world revolution against neoliberal globalization that had started in the late 20th century with the rise of the Zapatistas (Chase-Dunn and Almeida 2020). But the outcomes of some of these movements have brought the tactics of the global justice movement into question. The left-wing Syriza Party, elected in Greece in 2015, was a debacle that was crushed by the European banks and the EU. They doubled down on austerity, threatening to bankrupt the pensioners of Greece unless the Syriza regime agreed to new structural adjustment policies, which it did. This was a case in which another world was possible but did not happen. This disappointment was a poke in the eye of the other new leftist social media parties in Italy and Spain as well as the global justice movement.

The huge spike in global protests in 2011-2012 was followed by a lull and then a renewed intensification of citizen revolts from 2015-2016 (Youngs 2017). The Black Lives Matter movement, the Dakota Access Pipeline protest, the #MeToo movement, the global Women’s Marches and the Antifa rising against neo-fascism show that the World Revolution of 20xx is still happening, but that the powers that be have resources that can stymy mass protests in the absence of more organized political challenges.

The mainly tragic outcomes of the Arab Spring and the decline of the Pink Tide progressive populist regimes in Latin America were bad blows for the Global Left. The Social Forum process was late in coming to the Middle East and North Africa, but it eventually did arrive. The Arab Spring movements in the Middle East and North Africa were mainly rebellions of progressive students and young people using social media to mobilize mass protests targeting aging authoritarian regimes. The outcome in Tunisia, where the sequence of protests started, has been relatively good thus far, especially with respect to women’s rights (Moghadam 2019). But the outcomes in Egypt, Syria, Bahrein Turkey and Iran were disasters (Moghadam 2018).[8] The mass popular movements calling for democracy were defeated by Islamist movements that were better organized and by military coups and/or outside intervention. In Syria, parts of the movement were able to organize an armed struggle, but this was defeated by the old regime with Russian help. Extremist Islamic fundamentalists took over the fight from progressives, and the Syrian civil war produced a huge wave of refugees that combined with economic migrants from Africa to cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. This added fuel to the already existing populist nationalist movements and political parties in Europe, propelling electoral victories inspired by xenophobic and racist anti-immigrant sentiment. In Iran, the green movement was repressed. In Turkey, Erdogan has prevailed, repressing the popular movement as well as the Kurds. All these developments, except Tunisia, have been major setbacks for the Global Left.

The replacement of most of the Pink Tide progressive regimes and Latin America by reinvented local neoliberals and/or Trump-like strong men has largely been a consequence of falling prices for agricultural and mineral exports because Chinese demand slackened. The social programs of the leftist populist movements were dependent on their ability to tax and redistribute returns from these exports. This outcome was forecast by Veltmeyer and Petras (2014). Some of these rightward transitions have been accomplished by electoral processes, which can be seen as an improvement for Latin America where regime transitions in the past have been carried out by military coups and violence. But recent developments in Honduras, Bolivia and Venezuela indicate that Latin America has not fully transitioned to electoral regime change. In Brazil the threat of military rule continues to play a role in politics, but at least so far, the rightward shift has been less violent than it was in earlier regime transitions.

The continuing rise of right-wing populist and neofascist movements and their electoral victories in both the Global North and the Global South have added a new note that is reminiscent of the rise of fascism during the World Revolution of 1917 (Chase-Dunn Grimes and Anderson 2019). This raises the issue of the relationships between movements and counter-movements and the possibility that the further articulation of the Global Left could be driven by the need to combat 21st century fascism. The glorification of strong leaders in the right-wing populist and neo-fascist movements was also seen in the 20th century. But charismatic leaders have also been important in progressive movements in the past. The Democratic Socialists of America (D.S.A.) in some ways seem to be reacting against the “leaderless” ideology of the horizontalists by capitalizing on the extraordinary popularity of their most famous member, Bernie Sanders. The platform proposed by Sanders incorporates many of the tropes of the New Left and the global justice movement.

What Is Really Wrong with Capitalism?

The movements and regimes that seek to transcend capitalism need clear ideas about what is wrong with capitalism and how these deficiencies could be fixed. I agree with Arrighi (2006) that markets are not themselves the problem with capitalism. The use of the ideas of marketization and privatization by neoliberal politicians to attack labor unions and the welfare state tend to cause an over-reaction against markets and commodification.

Markets are useful for providing signals about demand as people vote with their money. Earlier world revolutions attacked commodification as a central problem of capitalism. This was a way of mobilizing masses who were alienated from the impersonality of market interactions as well as the huge inequalities that seemed to be produced by marketized exchange. John Roemer’s (1994) model of market socialism, in which the stocks of large firms are distributed equally to each citizen and can be traded for stocks that are considered more profitable, would keep pressure on large firms to be efficient and to make profits while distributing the rewards more equally to the whole population. This solves the problem of “soft budget constraints” in command economies such as the Soviet Union and the Peoples’ Republic of China because firms must sell products on a competitive market and must compete for capital. Such a model has not yet been tried. The experiments in coupon distribution carried out during the neoliberal “shock therapy” in Eastern Europe after the fall of communism were cruel jokes in which the old Communist oligarchies were able to set themselves up as new capitalist owners of the major means of production. Though I agree that “socialism” organized as a centralized command economy based on state ownership should not be tried again, I think that other models of socialism may well have an important place in the future because capitalism produces and reproduces unacceptable levels of inequality. Boswell and Chase-Dunn (2000) imagine a plausible form of socialism at the global level that combines Roemer’s market socialism with global institutions that reduce core/periphery relations and give some power to workers in the periphery.

The world revolution of 1917 also attacked individualism as one of the evils of capitalism. This was a big mistake. Protecting the rights of human individual is a valuable element of modernity that should not be attacked by socialists. Calling it “bourgeois individualism” and denigrating the legal protections of individuals that became ensconced in the U.N Declaration of Human Rights and enforced by some states is a mistake. Collective rationality and validation of human communities does not require the rejection of individualism as a value. This was a reactive mistake of earlier progressive movements and of the extreme national collectivism implemented in the fascist regimes of the 20th century. The majority of the Earth’s peoples have become acculturated to market exchange and individual rights. The culture of consumerism is not a problem because market exchange is alienating. It is a problem because it has been organized as profligate wasting of natural resources and pollution. Neo-socialist movements need to construct new versions of collective rationality that respect the rights of individuals.

The big issues of the 21st century are ecological degradation, north/south inequalities and a crisis of global governance due to the decline of U.S. hegemony. The current climate change crisis is unprecedented in the past 12,000 years. Atmospheric CO2 concentration is at its highest level for three million years. Polar ice caps are rapidly melting and the extent of damage to the biosphere from industrial and consumer pollution is huge. The threat to both the masses and the elites have led some to suppose that climate justice may serve as a fulcrum around which the network of progressive movements could come together to form a more capacious instrument of global struggle (Chase-Dunn and Almeida 2020).

Inequalities can be dealt with by means of the strategy of market socialism or by a global version of Keynesianism or some mixture of the two. Both would require legitimate and capacious institutions of global governance. Crises of ecological degradation such as global warming and climate justice also will require more legitimate and effective global institutions. And ecological degradation causes resource wars. Warfare can be reduced by means of conflict resolution carried out by democratic institutions of global governance. Capitalism is an ecological problem because capitalist firms usually externalize the environmental costs of their operations. Changing this will require regulatory institutions that have the capacity to enforce democratically made decisions about the use of natural resources and about who will pay for cleaning up pollution.

Conclusions

Do recent developments constitute the beginning of the terminal crisis of capitalism or the beginning of another systemic cycle of accumulation? As mentioned above, predominant capitalism has not been around very long from the point of view of the succession of qualitatively different logics of social reproduction. But capitalism itself speeds up social change. The contradictions of capitalism specified by Wallerstein will eventually reach levels that cannot be accommodated. But when will that happen? Declarations of an imminent transformation to a qualitatively different more humane and sustainable mode of accumulation are useful for mobilizing social movements. But millenarianism risks disappointment when the new utopian age does not arrive. But experiments in market socialism and ecologically sound communities are needed in order to demonstrate that these forms of social life are viable.

Either a new stage of capitalism or a qualitative systemic transformation are possible within the next three decades. It was noted above that the evolution of global governance has occurred in the past when enlightened conservatives implemented the demands of an earlier world revolution in order to cool out the pressures from below that were brought to bear in a current world revolution. The current crisis and world revolution could lead to a kind of global Keynesianism in which part of the global elite, spurred on by revolts of both the left and the right, forms a more legitimate and democratic set of global governance institutions to ameliorate some of the problems of the 21st century.

If U.S. hegemonic decline remains slow, as it was since the 1970s until the coming of the Trump regime, and if financial and ecological crises are spread out in time and conflicts among ethnic groups and nations are also spread out, then the enlightened conservatives and their allies would have a chance to build another world order that is still capitalist but that meets the current challenges at least partially. But if the perfect storm of calamities (Kuecker 2007) should all come together in the same period the progressive movements would have a chance to radically change and improve the mode of accumulation toward some form of green global socialism.

In the meantime, and either way, the movements need to clarify what is wrong with capitalism and what might be done to replace it. Even if the transformation to a collectively rational global commonwealth does not occur this time around, pushing the ideas and the demands can move things in the right direction. Progressive world revolutions usually lose in the short run, but in the middle or long run they win, at least so far. I advocate a more organized approach to world politics than has been the practice of the global justice movement so far. The rise of right-wing populism and neofascism is provoking the global left to consider the creation of a new instrument of struggle. The horizontalist culture of the global left and many progressive movements at the local and national levels means that older centralized forms of organization will be resisted, but there are new diagonalist forms that combine the virtues of local autonomy with the capacity for global-level mobilization and contention. Progressive diagonalist forms are emerging within the European Union and it may well be time to form a global party-network to carry on the global justice movement, contend with right-wing populism and neo-fascism and mobilize resistance in both the Global South and the Global North (Alvarez and Chase-Dunn 2019).

References

Aldecoa, John, C. Chase-Dunn, Ian Breckenridge-Jackson, and Joel Herrera. 2019. “Anarchism in the Web of Transnational Social Movements.” Journal of World-Systems Research 25(2): 373-394.

Alvarez, Rebecca, and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2019. “Forging a Diagonal Instrument for the Global Left: The Vessel.” Journal of World-Systems Research 25 (2). doi: https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2019.947.

Amin, Samir. 1990. Delinking: Towards a Polycentric World. London: Zed Books.

Arrighi, Giovanni. 1994 The Long Twentieth Century. London: Verso.

——. 2006. Adam Smith in Beijing. London: Verso

——, Terence K. Hopkins, and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic Movements. London: Verso.

—— and Beverly Silver. 1999. Chaos and Governance in the Modern World-System: Comparing Hegemonic Transitions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bello, Walden. 2002. Deglobalization. London: Zed Books.

Bond, Patrick 2018 “East-West/North-South – or imperial-subimperial?: The BRICS, global governance and capital accumulation” Human Geography 11,2

Boswell, Terry and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral of Capitalism and

Socialism: Toward Global Democracy. Boulder, CO.: Lynne Rienner.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher 1998 Global Formation: Structures of the World- Economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Chase-Dunn, C. 1999 "Globalization: a world-systems perspective," Journal of World-Systems Research 5,2

Chase-Dunn, C. and Andrew Jorgenson 2007 “Trajectories of trade and investment globalization” Pp. 165-185 in Ino Rossi (ed.) Frontiers of Globalization Research: Theoretical and Methodological Approaches. New York: Springer https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows10/irows10.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and Terry Boswell 2009 “Semiperipheral development and global democracy” in Phoebe Moore and Owen Worth, Globalization and the Semiperiphery: New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Chase-Dunn, C. Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 “Trade globalization since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system” American Sociological Review 65, 1: 77-95.

Chase-Dunn C. and Roy Kwon 2011 “Crises and Counter-Movements in World

Evolutionary Perspective” in Christian Suter and Mark Herkenrath (Eds.) The Global Economic Crisis: Perceptions and Impacts (World Society Studies 2011). Wien/Berlin/Zürich: LIT Verlag

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Chase-Dunn, C. Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence and Hiroko Inoue 2011 “Last of the hegemons: U.S. decline and global governance” International Review of Modern Sociology 37,1:1-29

Chase-Dunn, C. and Kirk Lawrence 2011 “The Next Three Futures, Part One: Looming Crises of Global Inequality, Ecological Degradation, and a Failed System of Global Governance” Global Society 25,2:137-153 http://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows47/irows47.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and R.E. Niemeyer 2009 “The world revolution of 20xx” Pp. 35-57 in Mathias, Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational Political Spaces. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/New York

Chase-Dunn, C. and Bruce Lerro 2014 Social Change: Globalization from the Stone Age to the Present. London: Routledge

Chase-Dunn, C. Hiroko Inoue, Teresa Neal, and Evan Heimlich 2015 “The Development of World-Systems” Sociology of Development 1,1: pp. 149-172 (Spring) http://socdev.ucpress.edu/content/1/1/149

Chase-Dunn, C. Peter Grimes and E.N. Anderson 2019 “Cyclical Evolution of the Global Right” Canadian Review of Sociology Volume56, Issue4 (November) : 529-555

Chase-Dunn, C., James Fenelon, Thomas D. Hall, Ian Breckenridge-Jackson, and Joel Herrera. 2019. “Global Indigenism and the Web of Transnational Social Movements.” In New Frontiers of Globalization Research: Theories, Globalization Processes, and Perspectives from the Global South, ed. Ino Rossi. New York: Springer.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Paul Almeida 2020 Global Struggles and Social Change. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Davis, Mike 2006 Planet of Slums. London: Verso

Evans, Peter B. 1979 Dependent Development: the alliance of multinational, state and local capital in Brazil. Princeton Unviersity Press.

Fletcher, Jesse B; Apkarian, Jacob; Hanneman, Robert A; Inoue, Hiroko; Lawrence, Kirk; Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 2011”Demographic Regulators in Small-Scale World-Systems” Structure and Dynamics 5, 1

Frank, Andre Gunder 1998 Reorient:: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Berkeley: University of California Press

Frank, Andre Gunder and Barry K. Gills.( eds.) 1993. The World System: Five Hundred Years or Five Thousand? London: Routledge.

Gills, Barry & Christopher Chase-Dunn 2019 “In search of unity: a new politics of solidarity and action for confronting the crisis of global capitalism” Globalizations, 16:7, 967-972, DOI: 10.1080/14747731.2019.1655889 https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rglo20/16/7?nav=tocList

Hall, Thomas D. and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2006 “Global social change in the long run” Pp. 33-58 in C. Chase-Dunn and S. Babones (eds.) Global Social Change: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

Hamashita, Takeshi 2003 “Tribute and treaties: maritime Asia and treaty port netowrks in the era of negotiations, 1800-1900” Pp. 17-50 in Giovanni Arrighi, Takeshi Hamashita and Mark Selden (eds.) The Resurgence of East Asia. London: Routledge

Henige, David P. 1970 Colonial Governors from the Fifteenth Century to the Present. Madison, WI.: University of Wisconsin Press.

Inoue, Hiroko Alexis Álvarez, E.N. Anderson, Kirk Lawrence, Teresa Neal, Dmytro Khutkyy,

Sandor Nagy, Walter DeWinter and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2016 “Comparing World-Systems: Empire Upsweeps and Non-core marcher states Since the Bronze Age”

IROWS Working Paper #56 http://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows56/irows56.htm

Kuecker, Glen 2007 “The perfect storm” International Journal of Environmental, Cultural and Social Sustainability 3

Lindholm, Charles and Jose Pedro Zuquete 2010 The Struggle for the World: Liberation Movements for the 21st Century. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. Martin, William G. et al 2008 Making Waves: Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005. Boulder, CO: ParadigmMc Michael, Phillip 2017 Development and Social Change. Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage.

Mitchell, Brian R. 1992. International Historical Statistics: Europe 1750-1988. 3rd edition. New York: Stockton.

Mitchell, Brian R. 1993. International Historical Statistics: The Americas 1750-1988. 2nd edition. New York: Stockton.

Mitchell, Brian R. 1995. International Historical Statistics: Africa, Asia, and Oceania 1750-1988. 2nd edition. New York: Stockton.

Moghadam, Valentine M. 2018 “Feminism and the future of revolutions” Socialism and Democracy, 32(1): 31-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1461749 ________ 2019 “Women and Employment in Tunisia: Structures, Institutions, and Advocacy”Sociology of Development, Vol. 5 No. 4, Winter 2019; (pp. 337-59) DOI: 10.1525/sod.2019.5.4.337

Nagy, Sandor. 2017. “Global Swings of the Political Spectrum since 1789: Cyclically Delayed Mirror Waves of Revolutions and Counterrevolutions.” IROWS Working Paper #124, http://irows.urc.edu/papers/irows124/irows124.htm.

Patomäki, Heikki. 2019 “A world political party: The time has come” GT (Great Transition) Network Essay, (February) Retrieved from https://www.greattransition.org/

Pleyers, Geoffrey (2011). Alter-Globalization. Malden, MA: Polity Press

Polanyi, Karl 1944 The great transformation. New York: Farrar & Rinehart

Reese, Ellen, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Kadambari Anantram, Gary Coyne, Matheu Kaneshiro, Ashley N. Koda, Roy Kwon, and Preeta Saxena. 2008. “Research Note: Surveys of World Social Forum Participants Show Influence of Place and Base in the Global Public Sphere.” Mobilization: An International Journal 13(4): 431-445.

Reitan, Ruth 2007 Global Activism. London: Routledge.

Robinson, William I 1996 Promoting Polyarchy: Globalization, US Intervention and Hegemony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——. 2008. Latin America and Globalization. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Unversity Press

——. 2010 “The crisis of global capitalism: cyclical, structural or systemic?” Pp. 289-310 in Martijn Konings (ed.) The Great Credit Crash. London:Verso.

Robinson, William I. 2019 Into the Tempest: Essays on the New Global Capitalism. Chicago: Haymarket

Rodrik, Dani (2018). “Populism and the Economics of Globalization.” Journal of International Business Policy. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-001-4.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa 2006 The Rise of the Global Left. London: Zed Press.Sen, Jai, and Peter Waterman (eds.) World Social Forum: Challenging Empires. Montreal: Black Rose Books

Silver, Beverly J. 2003 Forces of Labor: Workers Movements and Globalization Since 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Bergeijk, Peter A.G. 2018 “Deglobalisation 2.0: Trump and Brexit are but symptoms” (March 13) Deglobalisation Series https://issblog.nl/2018/03/13/deglobalisation-series-deglobalisation-2-0-trump-and-brexit-are-but-symptoms-by-peter-a-g-van-bergeijk/

Veltmeyer, Henry and James Petras 2014 The New Extractivism: A Post-Neoliberal Development Model or Imperialism of the Twenty-First Century? London: Zed Press

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984a “The three instances of hegemony in the history of the capitalist world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and Research in Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

——. 1984b The politics of the world-economy: the states, the movements and the civilizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——. 1998. Utopistics. or, historical choices of the twenty-first century. New York: The New Press.

——. 2003 The Decline of American Power. New York: New Press

——. 2010 “Contradictions in the Latin American Left” Commentary No. 287, Aug. 15, http://www.iwallerstein.com/contradictions-in-the-latin-american-left/

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2011 [1974] The Modern World-System, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press

Witt, Michael A. 2019 “De-globalization: theories, predictions and opportunities for international business research” Journal of International Business Studies Volume 50, Issue 7, pp 1053–1077| https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41267-019-00219-7

World Bank 2019. World Development Indicators [online]. Washington DC: World Bank.

http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators

Youngs, Richard (2017). “What are the meanings behind the worldwide rise in protest?”

openDemocracy (October). https://www.opendemocracy.net/protest/multiple-meanings-global-protest