Trade and the flag:

integration and conflict in 19th and

early 20th century

deglobalization

Chris

Chase-Dunn, Anders Carlson, Chris Schmitt, Shoon Lio,

Richard

Niemeyer and Robert A. Hanneman

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University

of California-Riverside,

To be presented at the Section on Peace, War, and Social Conflict Roundtable, Fri, Aug 11 - 2:30pm - 3:25pm, Annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Montreal. Draft v.8-9-06; 7470 words

IROWS

Working Paper #19 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows19/irows19.htm

Abstract:

The density and contours of

networks of transnational and international economic integration are

hypothesized by many theorists to be causally related to the patterns of

cooperation and conflict. [1]

The usual notion is that trade creates ties of symmetrical interdependence,

which are likely to inhibit conflict. We seek to test this hypothesis in the

19th and early 20th century run-up to World War I. We examine the

relationship between the structure of conflict and the contours of trade ties

during the 19th century wave of globalization and deglobalization. How were the international trade ties related

to the patterns of conflict and alliance that emerged during World War I?

Waves of Globalization

Over the past few

decades, there has been a surge of interest in the relationship between

globalization and political conflict in the interstate system. Most of the theorists

of the global capitalism school contend that beginning with the 1960s and

1970s, the world of national economies became transformed into a transnational

and global political economy (e.g. Sklair 2001). Scholars using the world-systems perspective

contend that the world-system of capitalism has been importantly transnational

for hundreds of years and that globalization in the sense of the expansion and

intensification of large-scale intercontinental interaction networks is both an

upward trend and a cycle. There were earlier periods of rapid globalization

that were followed by periods of deglobalization in which large-scale

interactions diminished. Keynesian

national development (the global New Deal) was the predominant strategy of the

development project led by the hegemonic

Neoliberalism was

the political ideology that became hegemonic in the 1980s because the competing

core countries -

Yet, in contrast

to the global capitalism school, we argue that the old system of national

states still exists and that something like the current wave of globalization

had happened before during the decline of British hegemony in the late 19th and early 20th century.

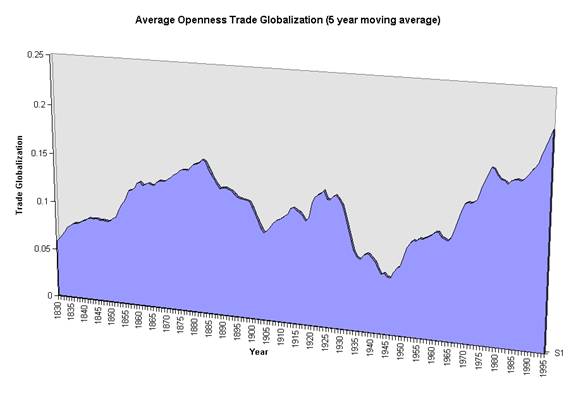

Studies of trade globalization – the ratio of international trade to the world

GDP-- show that there was a high peak in

the 1880s, then a decline until 1900, then another small rise, and a crash in

1929, and then a rise after World War II to the present,

which is somewhat higher than the peak in 1880, but not extremely higher (see

Figure 1). Investment globalization probably followed a similar trajectory

(Chase-Dunn, et al 2002)

Figure 1: Waves of trade globalization (Chase-Dunn, Kawano and

Brewer 2000)

Global Elite Networks and International

Trade Links

This paper is

part of a larger project, the purpose of which is to study the contours of global

elite and international integration since 1840 and to study the relationship

between these contours of connection and the patterns of conflict that emerged

over the same time period. There have

been a significant number of theoretical and empirical works by political

scientists and sociologists that examine the effects of economic

interdependence and international conflict (McMillan 1997; Barbieri and

Schneider 1999; Barbieri 2002; Rosecrance and Thompson 2003; Maoz 2004, Maoz et al 2006, forthcoming). Various

liberal theories of globalization argue that economic integration should

decrease international conflict. [3]We

observe that these approaches should distinguish between horizontal connections

(of equality) and vertical connections (power-dependency relations). The latter

may be quite likely to produce conflict (Barbieri 2002; Rosecrance and Thompson

2003).

Contra these

perspectives, many observers have noted that interdependent connections have

not served to prevent major conflicts in the modern international system

(Thompson and Tucker 1997; Rosecrance and Thompson 2003). Both

Our larger project

consists of two parts. In the first we are using a world historical perspective

to examine the links between elite individuals, families and organizations

within each country with those same actors in other countries. This involves a

close reading of the histories of each country with attention to connections

with other countries (see Reifer and Chase-Dunn 2003; Barr et al 2006). The second part of our project (discussed here) uses

quantitative data on the interactions among nation-states to trace the changing

patterns of network connections since 1880.

This enables us to use the national network patterns to place the

information from our studies of elites in a world historical context, and to

study the congruence or lack thereof, between different kinds of international

connections. We also intend to examine the relationships between international

network structures and the patterns of conflictive relations that were so

evident in the first half of the twentieth century. We know that the

international system bifurcated into Allies and Axis states in the World Wars. Were

these conflict-alliance bloc structures related to the trade network? Did the

network of global trade become more factional in the years prior to the

outbreak of world war? And did these factions correspond with the emergent

conflict factions?

We also will eventually

use network data to compare the overall magnitude of global integration in the

nineteenth century with the magnitude and forms of integration that have

emerged since World War II.[5] The

question of global magnitudes is important because many students of

globalization have assumed that the high degree of contemporary integration of

the global capitalist class will prevent the emergence of future interimperial

rivalry and war among core states. But if there was a similarly high level of

global elite integration in the late nineteenth century this assumption may be

brought into question.

In this paper we analyze

mainly international trade relations, but international financial links are another

important dimension of global economic networks that we plan to empirically

examine in the future. Imports and exports of goods and services are much

easier to get comparable information on than flows of investment, especially

for the nineteenth century. Ideally we would like to differentiate trade flows

into goods that are more strategic and profitable vs. those that are less so.

But that is not possible on a sufficient scale for the nineteenth century.

Transnational Relations and State-centrism

The use of data on nation-states is defensible on both

theoretical and practical grounds, and should not expose us to the slings and

barbs of those who would accuse us of state-centrism. Firstly, national states

have been, and still are, important organizations within the world-system.

Transnationalism has not just arisen since 1980. There have been waves of

transnationalism and waves of nationalism since the chartered companies of the

seventeenth century organized production and distribution on a global scale. The contemporary transnational corporations

undoubtedly organize a greater portion of the total world economy than the 17th

century chartered companies did. But then and now, national states were and

remain important players on the global stage.

We may say this

without denying the perspective developed by William I. Robinson (2004) and

others on the emergence of a transnational capitalist state that reconfigures

existing national states (and international organizations) as its instruments.

Indeed, we see the emergence of a transnational state, not just in the period

since the 1980s, but since the Concert of Europe that was

The practical

reason for using data on national states is that they are the only data that

are available for most of the regions of the system over the time period that

we seek to study. As with all secondary data

analyses, we need to be chary about the ways in which the structuring of the

data by its original providers may distort our results.

Methods for Our Analysis

We adopt the

generalized strategy of measurement error modeling that is part of the

structural equations tradition. This means that instead of trying to pick the

best single empirical indicator of an underlying concept or variable, we want

to use several proxy indicators and to model the relationships among the

proxies as well as using them to estimate the true underlying values of the

variables. In practice we may not have enough data to be able to actually

employ the techniques of structural equations modeling of measurement error.

But we shall use the generalized logic of gathering multiple proxy indicators

whenever this is possible.

Because the data

are less complete in the early decades, we have a growing population of nodes

as we get closer to the present. This, and the actual changes that occurred in

country boundaries over the period studied (e.g. the break-up of the Ottoman

and Austro-Hungarian empires, etc.), mean that we have a changing set of nodes

in the network. This makes it difficult to know whether observed changes were

due to real changes in the pattern of trade ties or to the inclusion of nodes

that were formerly not included because of missing data. One approach to this

problem that we have used in earlier research is to study constant groups over time. If we find similar trends between the

constant groups and the networks that are adding (or deleting) nodes we can

infer that observed changes are not due to changes in the compared units.

Variable Construction

Trade Network Data

Much of the late 19th

century and early 20th century trade data are reported in the

country’s domestic currency, which makes cross-national comparison

impossible. There are several possible

ways to deal with this problem. One is to convert all the country currency

values into a single currency such as the pound sterling or the U.S. dollar

using currency market exchange rates.[6] There

are a number of known problems with this approach. Currency market exchange rates are set by the

competitive buying and selling of currencies during some periods, but in other

periods the exchange rates have been set by international agreements. Between

the Bretton Woods conference in 1944 and the early 1970s the U.S. dollar was

pegged to a fictitious gold standard, and other currencies were pegged to the

dollar. These regulated exchange rates can still be used to change country

currencies into dollars, but this conversion reflects a worldwide agreement to

regulate currency markets rather than a world market for money. In 1974 the

dollar and other currencies were freed to exchange in world money markets.

Another problem

is that market exchange rates reflect the activities of large currency traders,

rather than just the daily conversions of currencies carried out by people who

need to change money. The actions of currency traders are intended to make

profits by buying and selling money, and this activity does not necessarily

reflect the value of the goods and services that national economies produce.

This is why economists have tried to devise a better method for converting

currencies into a single comparable metric that is based on purchasing power in

different countries (Kravis Heston and Summers 1982). These so-called purchasing

power parity (PPP) conversion ratios are not available for the 19th

century and the whole approach has been savaged by critics (e.g. Korzeniewicz,

Stach and Patil 2004).

Another method of

making country currency values comparable is to compute a percentage using a

denominator in the same metric units (country currencies). We have the total value of exports and

imports for each country in country currency, so we could compute the

percentage of the country’s trade with a particular other trade partner. This puts the numbers into a comparable

metric: percentages. But this is not a good solution to the problem for our

purposes. It does eliminate the need to use exchange rates, but at the cost of

computing a variable that will not be useful for our purpose of examining the relative

importance of a particular trade link in the context of the larger world trade

network. Knowing that the imports of

(did we use imports, exports, both or what?)

Construction of Conflict Dyads

The

countries considered in this analysis are those that fought in World War I, those

core countries of

To quantify

the intensity of conflict between two states (dyads), we relied upon three

separate indicators: 1) the Correlates of War data set compiled by Singer and

Small measuring the number of battle deaths experienced by each country in the

WWI, and 2) the Barbieri conflict data set consisting of two ordinal measures of conflict during WWI: one

representing the level of aggression country A displayed towards country B, and

the other representing the level of aggression country B displayed towards

country A.

Interestingly, each of these data sets exhibited complimentary

weaknesses. The Correlates of War data

is useful after a country goes to war because it demonstrates how

“intensely” the country was committed to fighting as a function of the number

of its dead, but the data says nothing of the level of conflict between

countries before they go to war.

In a similar fashion, the Barbieri data does an excellent job of

demonstrating the “ramping up” processes leading up to WW1, but after the fact

it is useless in distinguishing various levels of commitment to the war once it

has begun. Further, both data sets in

isolation demonstrated very high skewness and kurtosis, making interpretation

of correlation coefficients problematic.

To

remedy both of these problems we constructed a standardized index of conflict

intensity that combined all three measures.

This was carried out by transforming the “raw” values of each data set

into standardized scores using SPSS, and summing the result. At this point we realized that by

constructing the index in this fashion, we had inadvertently reduced the

contribution of the Correlates of War data.

What was once a very large difference in intensity between “a

militarized shared border,” and, “a combined war dead of over one million

soldiers,” had now been reduced to a one or two point index difference. Also, one country’s decision to enter into the

war as an ally of another is an indicator level of (low) conflict intensity

that was not being taken into account. So we modified our conflict indicator by

doubling the weight of the contribution of the battle deaths, and also coding

for whether or not a state was an ally of another.

So as to make neutrality during WWI represent zero

conflict between a pair of states, the index was scaled so that a value of –3.16

equated to war ally, 0 equated to neutral and a value of 16 equated to the highest level of conflict intensity. We do not have a measure that takes into

account various degrees of “war ally,” so the index jumps from –3.14 to 0, and

then ramps up incrementally to more than 16.

It should also be noted that although this final measure of conflict

does still display minor skewness and kurtosis, it is by far the best in this

regard when compared to the Correlates of War and Barbieri indicators (see Table

1).

|

|

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Level

of Conflict |

552 |

-3.14 |

16.09 |

.6315 |

3.14 |

2.023 |

4.8 |

| COW

|

552 |

0 |

3500000 |

208681.88 |

602579.10 |

3.143 |

9.584 |

| Barbieri Conflict Measure |

552 |

0 |

20 |

1.04 |

3.998 |

3.747 |

12.386 |

Dyadic Correlations between Conflict and Trade in 1880-1913

After constructing the conflict index, a Pearson r

test was used to determine the correlation between levels of trade for eight

time periods leading up to World War I and the intensity of conflict between

combatants during the war. The results

are shown in Table 2:

|

|

Intensity

of Conflict |

|

Amount

of Trade 1913 2-tailed Significance |

.231 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1912 2-tailed Significance |

.232 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1911 2-tailed Significance |

.233 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1910 2-tailed Significance |

.235 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1905 2-tailed Significance |

.173 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1900 2-tailed Significance |

.103 .016* |

|

Amount

of Trade 1895 2-tailed Significance |

.110** .010 |

|

Amount

of Trade 1890 2-tailed Significance |

.101* .017 |

|

Amount

of Trade 1885 2-tailed Significance |

.088* .040 |

|

Amount

of Trade 1880 2-tailed Significance |

.044 .299 |

|

*** Significant at .001 level ** Significant

at .01 level *

Significant at .05 level |

|

Table 2: Dyadic Correlations between Conflict and Trade in 1880-1913

As indicated

by the table, the amount of imports one country received from another had a

significant positive correlation with the level of conflict experienced within

the dyad during WWI. This was the case

in each of the above years, except 1880, which was also positive.

Controlling for Size:

Partial Correlation between Trade and Conflict

Given that a portion of the intensity of conflict index is

measured in battle deaths, it is advisable to control for the size of the

population of the countries involved.

Population dyads were created as a control variable using 1913

population data compiled by the

Correlates of War Project and the

|

Partial Correlation Controlling for Population |

|

|

|

Intensity

of Conflict |

|

Amount

of Trade 1913 2-tailed Significance |

.2289 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1912 2-tailed Significance |

.2302 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1911 2-tailed Significance |

.2304 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1910 2-tailed Significance |

.2327 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1905 2-tailed Significance |

.1703 .000*** |

|

Amount

of Trade 1900 2-tailed Significance |

.1012 .018* |

|

Amount

of Trade 1895 2-tailed Significance |

.1081 .011 |

|

Amount

of Trade 1890 2-tailed Significance |

.0994* .020 |

|

Amount

of Trade 1885 2-tailed Significance |

.0864** .043 |

|

Amount

of Trade 1880 2-tailed Significance |

.0425 .319 |

|

*** Significant at .001 level ** Significant

at .01 level *

Significant at .05 level |

|

Table 3: Dyadic Correlations between Conflict and Trade in 1880-1913 controlling

for population size

Although controlling for population size reduced the strength of

the positive correlation between level of trade and conflict by small amount,

the relationship once again remains significant in all years except 1880. Thus

our new analysis of dyadic correlations using an improved measure of conflict

confirms earlier results by Barbieri (2002) that show a significant positive

relationship between trade connections and the emergence of conflict. But does

this relationship hold up when we examine the whole network of interaction.

Analysis of dyads cannot take account of indirect connections but formal

network analysis can examine the structure of the whole system and look for

cliques or factions in the system. Are there strong subgroups in the trade

structure and, if so, do these correspond with the conflict factions that

emerged in World War I?

Network Analysis of Trade and Conflict

We used UCINet to produce comparable square matrices of our conflict and trade datasets for purposes of formal network analysis. A square matrix is produced by UCINet for purposes of formal network analysis. Network analysis is superior to dyadic correlation analysis because it allows the whole structure of a network to be analyzed including all the direct and indirect links and non-links. This makes it possible to identify cliques or factions within a network and to examine the centrality or peripherality of network nodes. The nodes in this analysis are countries.

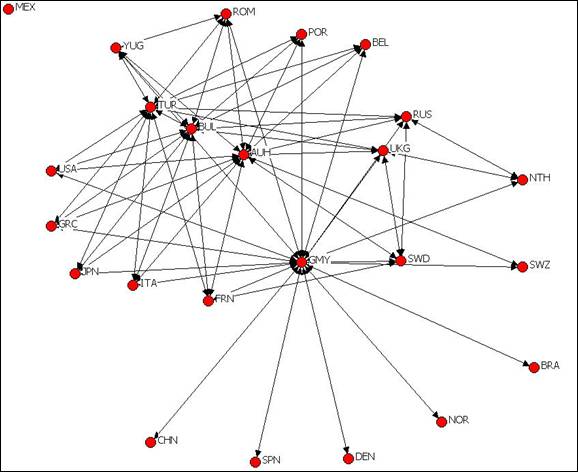

The

conflict matrix contains the values for each pair of countries computed for

our level of conflict indicator described above. This is then used to produce

Figure 2 by means of specifying a cutting point in the distribution of dyad

values. For Figure 2 we used ________________________________.

Figure 2: Level of Conflict Network for World War I. (Country names are Correlates of War abbreviations.)

Compare Figure 2 with the list of the

blocks in World War I in Table 4.

|

Allies (Entente) |

Central Powers |

Neutrals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Balkans (YUG) |

|

|

Table 4: Conflict Blocs in World War I

The

Central Powers in the middle of Figure 2 are not linked by conflict ties with

one another (except for something between

(insert the graphic of trade network in

1880 here and compare it with the next figure)

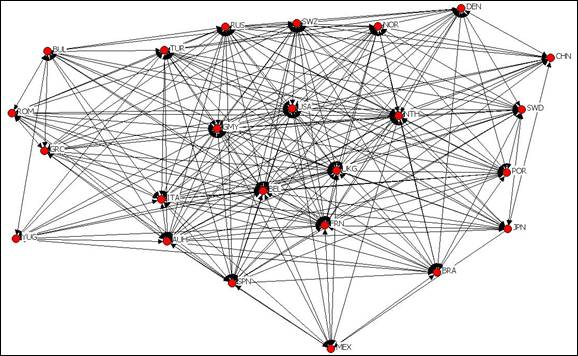

Figure

3 shows the network structure of trade in 1913 just before the outbreak of

World War I. The cutting point we used for the trade network graphic is

______________.

Figure 3 Trade Network for 1913. (Country names are the Correlates of War abbreviation.)

The

trade network graphic uses the values for dyads that we used in our

correlational analysis above. We have trade networks every five years from

1880 to 1913. This is a dense network but it clearly has a multicentered core

and a periphery.

Multiplicative Coreness

The

interaction matrices were also used to calculate multiplicative coreness. A multiplicative core

is characterized as a set of nodes possessing a high density of connections

amongst themselves, while the multiplicative periphery is characterized as

possessing few interconnections. The

consequence of such a structural condition is that nodes located within the

core are often capable of greater coordinated action and a greater

mobilization of resources, while nodes in the periphery are not. Computed a

coreness score for each country using the trade matrices for every five years

between 1880 and 1913 and then used these score to compute a gini coefficient

that indicates how much dispersion there is in the distribution of coreness

scores across countries.

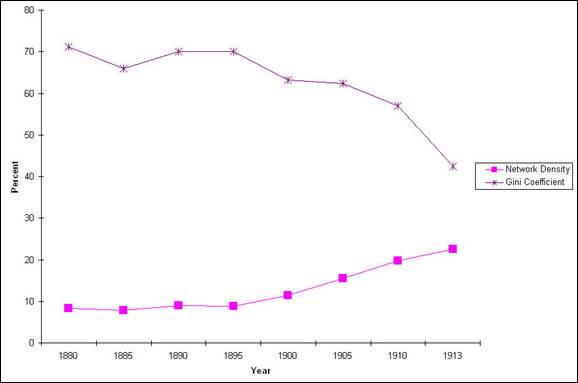

Figure 4 Graph of the relationship between the Gini Coefficient and Level of Network Density for the Trade Network from 1880 to 1913

Figure 4 is the graph

demonstrating the relationship between the Gini Coefficient and the Level of

Network Density for the Trade Network of participants in World War 1. In network analysis, Gini Coefficient

measures the amount of inequality between the core and periphery nodes in

terms of the distribution of connections. (What is network density?) Within the trade network presented here the

level of inequality as indicated by the Gini Coefficient declines slightly

from 1880 to 1910 and then it declines steeply. This indicates that the

network is becoming less centralized as British hegemony in the world economy

is declining because other countries are growing. From 1880 to 1910 the core of the network

consists solely of the

At the same time the

Gini Coefficient is decreasing, the density of the network is increasing. In other words, the centralization of control

over trade in the world-system is decreasing at the same time the level of

competition for trade is increasing. Thus at the level of the global economy,

a clear increase in the level of competition and distribution of resources

preceded the world war, and these changes accelerated in the years just before

the outbreak of the war. [7]

Table 5: QAP correlations between the level of trade between nodes in the network and the level of conflict occurring during World War 1

We used

the QAP routine in UCINet to produce Pearson’s r correlation coefficients for

the values in the square conflict and trade matrices. QAP assesses the frequency of

random correlations as large as those actually observed, making it possible to

test the statistical significance of the observed correlations between two

square matrices despite the fact that the cells are not independent from one

another.

As was the case in the dyadic analysis, there is a clear non-negative correlation between trade and conflict. In other words, the more the nodes of the network trade with each other, the more likely they are to go to war. Unlike the dyadic analysis though, only the levels of trade in 1913 and 1910 are significant predictors of the level of conflict in World War 1. Interestingly, the size of the positive correlations is the same for both the dyadic and network analysis.

We used UCINet’s Faction routine to identify trade factions from the trade network matrix. The Faction routine allows valued data but requires specification of the number of factions. When three factions are specified UCINet groups the countries as shown in Table 6 based on the trade network data. Table 6 also shows which countries are in which conflict bloc.

|

Entente Allies |

Central Powers |

Neutral |

|

|

|

|

|

Belgium 2 |

Austria-Hungary 2 |

Brazil 1 |

|

France 2 |

Bulgaria 2 |

China 3 |

|

Greece 2 |

Germany 1 |

Denmark 1 |

|

Italy 3 |

Turkey 2 |

Mexico 3 |

|

Japan 3 |

|

Netherlands 1 |

|

Portugal 1 |

|

Norway 1 |

|

Romania 2 |

|

Spain 1 |

|

Russia 2 |

|

Sweden 1 |

|

UK 2 |

|

Switzerland 1 |

|

USA 3 |

|

|

|

Balkans 2 |

|

|

Table 6: War Factions and Trade Faction (1,2, and 3)

Table 7 below is a crosstabulation of the conflict blocs and the trade factions.

|

|

|

War faction |

|

|

Total |

| |

|

Entente Allies |

Central Powers |

Neutrals |

|

|

Trade faction #1 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

9 |

|

| |

Trade faction #2 |

7 |

3 |

|

10 |

| |

Trade faction #3 |

3 |

|

2 |

5 |

| Total |

|

11 |

4 |

9 |

24 |

For the Entente

Allies 7 of 11 are in trade faction #2. For the Central Powers 3 of 4 are

also in trade faction #2. For the Nuetrals 7 of 9 are in trade faction #1.

None of the Central Powers are in trade faction #3, which contains 3 Entente Allies

and 2 Neutrals.

So there is not a great match

between the trade factions and the conflict blocs. Trade faction #2 contains

75% of the Central Powers and 64% of the Allies. The best match is

that 7 of 9 Neutrals are in trade faction #1. It would seem logical

according to the liberal hypothesis that a country would remain neutral if it

was trading with both sides and did not want to offend either one. But

instead Tables 6 and 7 show that those countries that were less connected

with either side by trade were more likely to remain nuetral. And

Thus the

results of network analysis do not contradict earlier findings or the

replicated (and improved) dyad analysis described above. Indeed there is some

additional positive support for the notion that trade connections do not

reduce the likelihood of conflict. But a new connection between trade and

conflict is shown in Figure 4 above. The overall shape of the trade network

was changing in the decades prior to the war and these changes accelerated

just before the war. The network was getting denser and less hierarchical.

The centrality of

The lack

of correspondence that we find between trading factions and the conflict

blocs that emerged in the Great War echos what many war historians have often

said – the structure of alliances were fluid and did not gell until just

before the conflagration. As late as 1901, during the second Boer War, the

populations of both

References

Alderson, Arthur S. and

Jason Beckfiled 2004 “Power and position in the world city system,”

American Journal of Sociology 109:811-51.

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth Century.

Bairoch, Paul and

Richard Kozul-Wright 1998 “Globalization myths: some historical

reflections on

integration, industrialization and growth in the world economy,”

pp. 37-68 in Richard

Kozul-Wright and Robert Rowthorn (eds.) Transnational

Corporations and the Global Economy.

Barbieri, Katherine

2002 The Liberal Illusion: Does

Trade Promote Peace?

Barr, Kenneth, Shoon

Lio, Christopher Schmitt, Anders Carlson, Kirk Lawrence, Jonathan

Krause, Yvonne Hsu, Christopher Chase-Dunn and Thomas

E. Reifer 2006 “Global

conflict and elite integration in the 19th and early 20th centuries” Presented at the

Annual

Meeting of the American Sociological Association, in

at 10:30 am on August 11, 2006 at the session on World Systems organized by

Farshad

Araghi. IROWS Working Paper

#27 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows27/irows27.htm

Bollen, Kenneth A. 1989

Structural Equations with Latent Variables.

Bornschier,

Volker and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.) 1999 The

Future of Global Conflict

Carroll, William K.

Forthcoming “Global cities in the global corporate network” American

Journal

of Sociology.

Carroll, William K. and

Colin Carson 2003 “The Network of Global Corporations and

Policy Groups: A Structure for Transnational Capitalist

Class Formation?” Global

Networks

3 (1): 29-57.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher 1990 “World State Necessity” Political Geography Quarterly, 9,2: 108-30 (April). https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows1.txt

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

2005 “Upward sweeps in the historical evolution of world-

systems” IROWS Working Paper #20 available at

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows20/irows20.htm

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 "Trade

Globalization since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system,"

American Sociological Review

65:77-95 (February). summarized in Scientific

American June 2003.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Andrew Jorgenson, Rebecca

Giem, Shoon Lio, Thomas E. Reifer and John Rogers, 2002 “Waves of Structural

Globalization since 1800: New results on Investment Globalization”

A paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association,

August 16-19, Chicago.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Andrew Jorgenson, Shoon

Lio and Thomas Reifer, 2005

"The Trajectory of the

United States in the World-System: A Quantitative Reflection"

Sociological Perspectives.

Choucri, Nazli and

Robert North 19xx Nations In Conflict.

Eugene Date Management

Software: www.eugenesoftware.org

Freeman, Linton C.,

Douglas R. White and A. Kimball Romney 1992 Research Methods in Social Network Analysis. Transaction Press

Goldfrank, Walter L.

1977 “Who rules the world: class formation at the international level” Quarterly Journal of Ideology 1,

____________1983 “The

limits of an analogy: hegemonic decline in

the

Hanneman, Robert nd Introduction to Social Network Methods

http://faculty.ucr.edu/%7Ehanneman/SOC157/TEXT/TextIndex.html

Held, David, Anthony

McGrew, David Goldblatt and Jonathan Perraton. 1999. Global Transformations:

Politics, Economics and Culture.

Hirschman,

Albert O. 1980 [1945] National Power

and the Structure of Foreign Trade.

Johnson, Ian 2000 “A

step-by-step guide to setting up a TimeMap dataset.” Archaeological

Computing Laboratory.

Junne,

Gerd 1999 “Global cooperation or rival trade blocs?” in Volker Bornschier and

Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.)

The

Future of Global Conflict.

.

Kentor, Jeffrey. 2000a.

“Shifting Patterns of Organizational Control in the World-Economy 1800 1990.”

Funded Grant Proposal

to World Society Foundation:

_____. 2000b. Capital and Coercion: The Economic and

Military Processes That Have Shaped the World Economy 1800-1990.

Kentor, Jeffery and

Yong Suk Jang 2004 “Yes, there is a transnational business community.” International Sociology 19,3:352-368.

Korzeniewicz, Roberto

Patricio, Angela Stach and Vrushali Patil 2004 “Measruing national income: a

critical assessment.”

Comparative Studies in Society and History

Krasner, Stephen D.

1976 “State power and the structure of international trade,” World Politics 28,3:317-47.

Kravis, Irving B., Alan

Heston and Robert Summers 1982 World

Product and Income:

International Comparisons of Real Gross Product.

University Press.

Krempel, Lothar

and Thomas Pluemper 1999

“International division of labor and global economic processes:

an analysis of the

international trade in automobiles” Journal

of World-Systems Research, 5,3:487-498

Levy, Jack S. 1983 War in the Modern Great Power System,

1495-1975.

University Press of

Maddison, Angus 1995 Monitoring the World Economy, 1820-1992.

Economic Cooperation

and Development.

_________ 2001 The World Economy: A Millennial

Perspective.

Cooperation and

Development

Mitchell, B.R. 1992 International Historical Statistics:

____________ 1993 International Historical Statistics: The

NY:

____________ 1995 International Historical Statistics: Africa, Asia, &

2nd ed. NY:

Maoz, Zeev 2006. “Network Polarization, Network Interdependence, and International Conflict, 1816-2002.” Journal of Peace Research, 43(4): 391-411 http://jpr.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/43/4/391 Maoz, Zeev, R. Kuperman, L. Terris, and I. Talmud. 2004 “International Relations: A Network Approach." in New Directions for International Relations, Edited by A. Mintz and B. Russett. Lanham , MD : Lexington Kuperman, and L. Terris). http://soc.haifa.ac.il/~talmud/evolution.pdf Maoz, Zeev, R. Kuperman, L. Terris, and I. Talmud. forthcoming "Structural Equivalence and International Conflict, 1816-2000: A Social Networks Analysis of Dyadic Affinities and Conflict." Journal of Conflict Resolution http://soc.haifa.ac.il/~talmud/strucequiv.pdf Maoz, Zeev, R. Kuperman, L. Terris, and I. Talmud. forthcoming "The Enemy of my Enemy: The Effects of Indirect Enmity Relations on Direct Dyadic Relations," Journal of Politics .

O’Rourke, Kevin H and

Jeffrey G. Williamson 1999 Globalization

and History: The Evolution of

a

19th Century Atlantic Economy.

Polanyi, Karl 2001

[1944] The Great Transformation.

Rasler, Karen A. and

William Thompson. 1994. The Great

Powers and Global Struggle: 1490 1990.

Reifer, Thomas E. 2002

“Globalization & the National Security State Corporate Complex (NSSCC) in

the Long Twentieth Century,”

Reifer, Thomas E. and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2003 “The Social Foundations of Global Conflict and

Cooperation:

Waves of Globalization

and Global Elite Integration, 19th to 21st Century. Research Proposal Funded

by the National

Science Foundation’s

Sociology Program. https://irows.ucr.edu/research/glbelite/globeliteprop03.htm

Reifer, Thomas E.

“Globalization, Democratization & Global Elite Formation in Hegemonic

Cycles: A Geopolitical Economy,”

2005, in Jonathan

Friedman & Christopher Chase-Dunn, eds., Hegemonic Declines, forthcoming

Paradigm Publishers, Ch. 7, pp. 183-201.

Robinson, William I.

2004 A Theory of Global Capitalism.

Rosecrance, R. 1963. Action

and Reaction in World Politics.

Rosecrance, Richard and

Peter Thompson 2003 “Trade, foreign investment and security,” Annual Review of Political Science

6:377-98.

Sklair, Leslie. 2001. The Transnational Capitalist Class.

Smith, David A. and

Douglas R. White 1992 “Structure and Dynamics of the Global

Economy: Network

Analysis of International Trade 1965-1980,” Social Forces 70:857-

894

Sassen, Saskia 2001 The Global City:

Press.

Sklair, Leslie 2001 The Transnational Capitalist Class.

Smith, David A. and

Michael Timberlake. 2001. “

1977-1997: An Empirical

Analysis of Global Air Travel Links.” American

Behavioral

Scientist 44, 10: 1656-1678.

Snyder, Jack 1991. Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International

Ambition.

_____. 2000. From Voting

to Violence: Democratization and

Nationalist Conflict.

_____.2003."Imperial

Temptations." The National Interest. 71:29-40.

Su, Tieting. 1995.

"Changes in World Trade Networks: 1938, 1960, 1990" Review XVIII, 3

:431-459 (Summer)

Van der Pijl, Kees.

1984. The Making of an

______________ 1998 Transnational Classes and International

Relations,

Weber, Max. 1961. General Economic History,

Appendix

Histogram

for Level of Conflict Index

Supplementary

Trade Data

According to Barbieri (2003), “The

Statesman’s Yearbook contains country profiles that usually include

tables of foreign trade figures. When

these tables are not present, information was pieced together by reading

entries related to a particular state’s economic activities. For the period 1873-1885 U.S. Congressional

records proved to be a useful source of trade data, in particular U.S.

Congress (House) Miscellaneous Documents (1887), “Abstract of the Foreign

Commerce of Europe, Australia, Asia and Africa, 1873-1885,” United States

Consular Reports, No. 85, October. (

According to Barbieri (2003), “several problems arose

when converting trade figures from local currencies to US dollars. The primary problem was the lack of available

exchange rates for many states. In

many instances trade data reports were available, but exchange rates were

unavailable. In addition, Polity II

contains a variable that lists the name of the national currency to which the

exchange rate is presumed to correspond.

However, in many instances no currency name is given. Also, in some instances, particularly in

Latin American states, the value of import and export flows are reported in

two different currencies. For example,

silver pesos may be used for imports, while gold pesos are used for

exports. This requires separate

exchange rates for converting imports and exports into US dollar values (see

Appendix for supplementary data sources).”

Links

to Related Data Online

Conflict Data Sets: http://www.pcr.uu.se/pdf/conflictdataset2.pdf

http://www.umich.edu/~cowproj/dataset.html

(Link to Correlates of War Project; includes a number of datasets that deal

with war/conflict)

Katherine Barbieri

Trade Data Sets:

http://sitemason.vanderbilt.edu/site/k5vj7G/new_page_builder_4

http://weber.ucsd.edu/~kgledits/Polity.html

(Link to POLITY project datasets, which include data on cross-national

authority structures)