East

and West in

World-Systems

Evolution

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute for Research on

World-Systems

University of

California-Riverside

and

Thomas D. Hall

Sociology

Abstract:

This paper uses the comparative world-systems perspective to address issues

raised in Andre Gunder Frank’s world historical study of East Asia and Giovanni

Arrighi’s comparison of

To be presented at the

conference on Andre Gunder Frank’s Legacy of Critical

Social Science, April 11-13, 2008

Andre Gunder Frank’s legacy is deep and wide. He

was a founder of dependency theory and the world-systems perspective. He took

the idea of a whole historical system very seriously and his rereading of Adam

Smith has borne new fruit in Giovanni Arrighi’s (2007) recent comparison of

The comparative world-systems perspective uses

world-systems, defined as important and consequential interaction networks, to

describe and explain human socio-cultural evolution since the emergence of

language. It compares earlier and smaller regional world-systems to later and

larger continental and global world-systems in order to see the patterns of

structural change. The claim is that, at least since the emergence of

chiefdoms, much of human socio-cultural evolution cannot be explained without

using world-systems (rather than single societies) as the unit of analysis. This

is because semiperipheral societies have been an important source of innovation

and transformation in all world-systems that have core/periphery hierarchies (Chase-Dunn

& Hall 1997: Ch. 5).

Spatial

Boundaries of World-Systems

Before the global world-system emerged in the 19th

century CE nearly all regional systems were composed of spatially nested

interaction networks. There were smaller bulk goods networks (BGNs), in which

food and everyday raw materials were circulated. These were encompassed by

larger networks of sovereign polities that fought and allied with one another

(political-military networks – PMNs).[1]

These in turn were encompassed within even larger networks in which prestige

goods and information flowed (PGNs and INs).

Bulk goods and political-military networks were extremely important for

the reproduction or change in local socio-cultural structures in all systems.

Prestige goods networks were more important in some systems than in others, and

the nature of the functioning of prestige goods was different in some systems

than in others.[2]

Using nested interaction networks to define the spatial

boundaries of systems makes it possible to map the expansions and contractions

of interaction networks over time.[3] David Wilkinson (1987) produced a chronograph

of the expansion of what he originally called “Central Civilization” (a

political-military network) that began with 3rd millennium BCE

Mesopotamia and

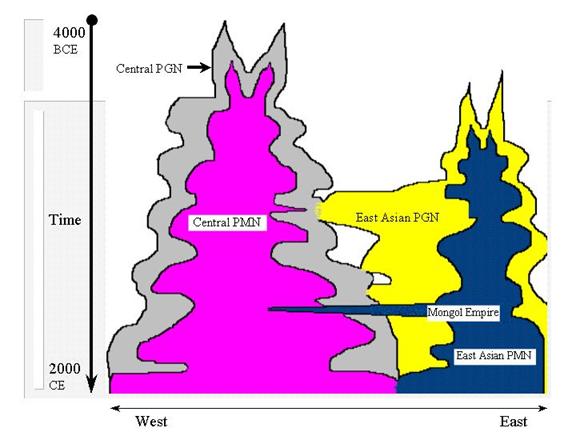

Figure 1: East/West Networks Expand

and Merge

Figure 1 portrays the

expansion of state-based world-systems in both

This approach to bounding systems is much more

empirically explicit than that adopted by Andre Gunder Frank in his work on

5000 years of world system history (Frank and Gills 1993). Frank and some of

his followers (e.g. Chew 2001) seemed to think that there was already a global,

or at least a Eurasia-wide world-system 5000 years ago. This was an instance in

which “painting with broad strokes” missed a lot of important detail. The important volume by Arrighi, Hamashita

and Selden (2003) gets the spatial bounding of East-West connections mostly

right.

Semiperipheral

Development

Another important recurrent pattern that becomes

apparent once we use world-systems as the unit of analysis for analyzing socio-cultural

evolution is the phenomenon of “semiperipheral development.” This means that

semiperipheral groups are unusually prolific innovators of techniques that both

facilitate upward mobility and transform the basic logic of social reproduction.

This is not to say that all semiperipheral groups produce such transformational

actions, but rather that the semiperipheral location is more fertile ground for

the production of innovations than is either the core or the periphery. This is

because semiperipheral societies have access to both core and peripheral

cultural elements and techniques, and they have invested less in existing

organizational forms than core societies have. So they are freer to recombine

the organizational elements into new configurations and to invest in new

technologies, and they are usually more highly motivated to take risks than are

older core societies. Innovation in older core societies tends toward minor

improvements. Semiperipheral societies are more likely to put their resources

behind radically new concepts.

Thus

knowledge of core/periphery hierarchies and semiperipheral locations is

necessary for explaining how small-scale interchiefdom systems evolved into the

capitalist global political economy of today. The process of rise and fall of

powerful chiefdoms, called “cycling” by anthropologists (Anderson 1994; Hall

2001, 2006), was occasionally punctuated by the emergence of a polity from the

semiperipheral zone that conquered and united the old core region into a larger

chiefly polity or an early state. This phenomenon is termed the “semiperipheral

marcher chiefdom” (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997:83-84, Kirch 1984:199-202).

Much

better known is the analogous phenomenon of “semiperipheral marcher states” in

which a relatively new state from out on the edge of a core region conquered

adjacent states to form a new core-wide empire (Mann 1986; Collins 1981).

Almost every large conquest empire one can think of is an instance of this. A

less frequently perceived phenomenon that is a quite different type of

semiperipheral developed is the “semiperipheral capitalist city-state.” Dilmun,

early Ashur, the Phoenician cities, the Italian city-states, Melakka, and the

Hanseatic cities of the Baltic were instances. These small states in the

interstices of the tributary empires were agents of commodification long before

capitalism became predominant in the emergent core region of

The semiperipheral development idea is also an

important tool for understanding the real possibilities for global social

change today because semiperipheral countries are the main weak link in the

global capitalist system – the zone where the most powerful antisystemic

movements have emerged in the past and where vital and transformative

developments are most likely to occur in the future.

The

Idea of Evolution

It

remains necessary to clarify what we mean and what we do not mean by the word

“evolution.” Sanderson (1991; 2007) has explained that the scientific study of

evolution must be cleansed of certain assumptions that tend to be included by

most users of this word. We are not necessarily talking about “progress.”

Progress is an idea that requires specifying a set of desiderata, value

commitments, and assumptions about what is good and what is not. That is a fine

thing to do and we shall do it toward the end of this paper. Progress can be an

empirical question once one has defined what is meant. But the study of

evolutionary patterns of change need not assume either progress nor its

opposite, regress. It is simply a study of certain directional patterns of

change.

In general societies have gotten larger and more complex

and more hierarchical albeit with occasional reverses in these patterns. We

further note that new social forms most often arise out of a necessity fostered

by social interactions, resource shortages, climate change, diffusion of new

ideas, technologies, or microorganisms, and most typically a combination of one

or more of these. New social forms often appear via a satisficing mechanism:

the first form that is found to work is seized. As more versions appear (say

states) and come into competition a selection process favors those that can outproduce

and outfight the others, that is, a maximization process. However the

“selection pressure” is locally determined, both spatially and chronologically.

We also note that these changes, or evolution, are rarely linear, or even

smooth. Rather, they are marked by many reversals, collapses, fragmentations,

etc. (Hall 2006). Development of complexity often engenders other societies to

become more complex, though at times promotes break up or collapse to simpler forms.

Scientific explanations of evolutionary change do not employ purposes as causes

(teleology) and they do not assume inevitability.

Central and East

Asian Evolution since the Stone Age

East Asian complexity and

hierarchy emerged as sedentary agriculture developed in inland fertile valleys.

Horticultural settlements developed into chiefdoms and farmers traded and

fought with those groups that continued to rely primarily on hunting and

gathering. Eventually the hunter-gatherers were pushed onto the steppes, where

they shifted toward pastoralism. Thus began the long sedentary/nomadic dance

that was to have such huge consequences for the evolution of East Asian

world-systems. The pastoralists traded meat and live animals for grain. Some of

them settled on the edges of the region of sedentary polities to form new

semiperipheral chiefdoms, and later states. Often small states and nonstate

societies were linked by trade networks (Smith 2005).

In

It was not until the first century B.C. that the

The partial isolation of Chinese civilization from the

West was great enough to prevent the diffusion of phonetic writing, an

invention that spread widely in the West displacing earlier ideographic forms

of writing. By the time contacts with the West became more common, the Chinese

already had a substantial investment in a great literature written in their

ideographic script and this became the symbolic core of Eastern civilization

that could not be lightly thrown away in favor of a less cumbersome form of

representing language. Ideographic writing also had the advantage that it could

easily transcend dialect, and even language differences. It served as a lingua

franca, not unlike Latin in

Indeed, the silk road cities, and occasional statelets

were hotbeds of change, as would be expected in nodal areas. Recent works by

McNeill and McNeill (2003) and Christian (2004) have stressed the importance of

trade and communications networks in the processes of human socio-cultural

evolution. Both of these recent works employ a network node theory of

innovation and collective learning that is similar to the human ecology

approach developed earlier by Amos Hawley (1950). Innovations are said to be

unusually likely to occur at transportation and communications nodes where

information from many different sources can be easily combined and recombined.

This is one, but only one, of the reasons Andre Gunder

Frank (1992) argued for the Centrality of

Central Asia. Central Asian states seldom made the semiperipheral marcher

state transition – with the glaring exception of the Mongols (Hall 2005) – they

were conduits of change in many directions. Indeed, Central Asian nomads were

the vectors of many social changes, in all directions (for instance see

Barfield 1989; Kradin 2002; Kradin et al. 2003). For most of its four millennia history

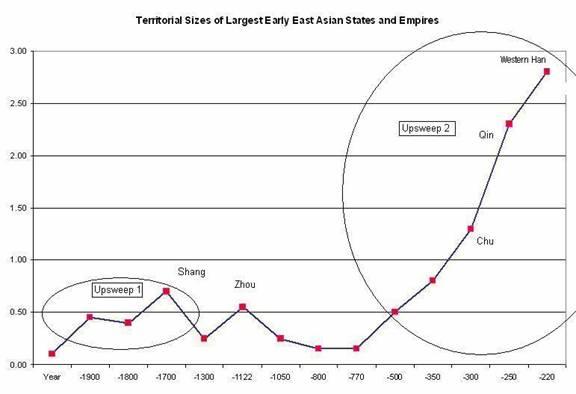

Figure 2: Largest Empires in the East Asian Region

Figure 2 shows the

territorial sizes in square megameters of the largest states and empires in

East Asia from 1900 BCE to 206 BCE with the sequential upsweep carried out by

The history of core/periphery interaction in

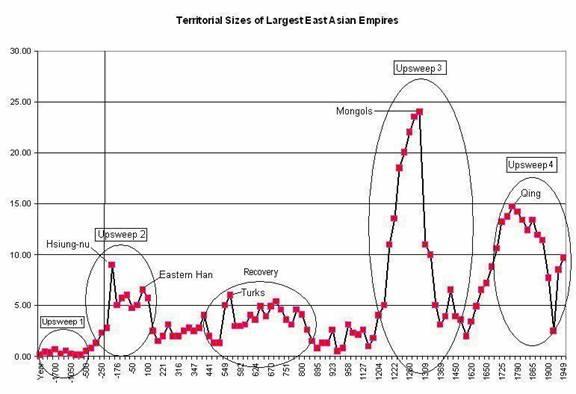

Figure

3: Territorial sizes of largest states and empires in

Figure 3 shows the sizes

of the largest states and empires in

All these upward sweeps in the territorial sizes of empires involved

semiperipheral or peripheral marcher states. The Hsiung-nu were classic horse

pastoralist nomads who came out of

In his classic study, Inner

Asian Frontiers of China, Owen Lattimore graphically described the cycles

of Chinese dynasties thus(1940: 531):

Although

the social outlook of the Chinese is notable for the small honor it pays to

war, and although their social system does not give the soldier a high

position, every Chinese dynasty has risen out of a period war, and usually a

long period. Peasant rebellions have been as recurrent as barbarian invasions.

Frequently the two kinds of war have been simultaneous; both have usually been

accompanied by famine and devastation, and peace has never been restored

without savage repression. The brief chronicle of a Chinese dynasty is very

simple: a Chinese general or a barbarian conqueror establishes a peace which is

usually a peace of exhaustion. There follows a period of gradually increasing

prosperity as land is brought back under cultivation, and this passes into a

period of apparently unchanging stability. Gradually, however, weak administration

and corrupt government choke the flow of trade and taxes. Discontent and

poverty spread. The last emperor of the dynasty is often vicious and always

weak--as weak as the founder of the dynasty was ruthless. The great fight each

other for power, and the poor turn against all government. The dynasty ends,

and after an interval another begins, exactly as the last began, and runs the

same course.

Lattimore qualifies this characterization for different

periods. But it remains an

insightful description of a process that repeated itself over the centuries

until

Reorient and Largest Cities: The Timing of the

Rise of the West

Andre Gunder Frank’s (1998) provocative study of the

global economy from 1400 to 1800 CE contended that

Frank’s

model of development is basically a combination of state expansion and

financial accumulation, although in Reorient he focused almost

exclusively on financial centrality as the major important element. His study

of global flows of specie, especially silver, is an important contribution to

our understanding of what happened between 1400 and 1800 CE. Frank also uses

demographic weight, and especially population growth and growth of the size of

cities, as an indicator of relative importance and developmental success.

Figure 4: Regional Urban Population as a % of the World’s Largest Cities

In Figure 4 we see the

emergence of the world’s first cities in Mesopotamia and

The

relative size-importance of European cities (indicated by the solid line) shows

a long oscillation around a low level, indicating

All

the largest cities on Earth, including those in the

The

trajectory of

For

Frank’s

depiction of a sudden and radical decline of

Our

examination of the problem of the relative importance of regions relies

exclusively on the population sizes of cities, a less than ideal indicator of

power and relative centrality.[4]

Nevertheless, these results suggest some possible problems with Andre Gunder

Frank’s (1998) characterization of the relationship between Europe and

Counter

to Frank’s contention, however, the rise of European hegemony was not a sudden

conjunctural event that was due solely to a developmental crisis in

This process of regional core formation and its associated emphasis on capitalist commodity production further spread and institutionalized the logic of capitalist accumulation by defeating the efforts of territorial empires (Hapsburgs, Napoleonic France) to return the expanding European core to a more tributary mode of accumulation.

Acknowledging some of the

unique qualities of the emerging European hegemony does not require us to

ignore the important continuities that also existed as well as the

consequential ways in which European developments were linked with processes

going on in the rest of the Afroeurasian world-system. The more recent emergence of East Asian cities as

again the very largest cities on Earth occurred in a context that was

structurally and developmentally distinct from the multi-core system that still

existed in 1800 CE. Now there is only one core because all core states are

directly interacting with one another. While the multi-core system prior to the

eighteenth century was undoubtedly systemically integrated to an important

extent, it was not as interdependent as the global world-system has now become.

A

new East Asian hegemony is by no means a certainty, as both the

Modes of Accumulation

and the East/West Comparison

In 1989 Gunder Frank wrote the first version of his

contention that “the modes of production” distinction made by Marxists is just so

much ideological nonsense (Frank 1989).[5]

He had discovered that something very like capitalism existed in the ancient

and classical worlds, and he had become quite skeptical about the idea of the

transition from feudalism to capitalism in

This

conceptual move on Frank’s part was arguably an over-reaction to some very important

but not well-understood insights – that markets, money, merchant capitalism,

finance capitalism, capitalist manufacturing and wage labor had played a much

more important role in the ancient and classical worlds than many others had

recognized, and that much of the Marxist version of the transformation of modes

of production was very Eurocentric. Furthermore, as did many others by 1989, Frank

came to see the

Our own position is that there, indeed, have been major transformations

in the modes of accumulation. One reason both Frank, and to lesser extent

Arrighi, miss this is that they start their histories well after states have

been invented. We however (1997) start about 12 millennia ago, and recognize,

along with many anthropologists, that the invention of the state is itself a

major shift, marking the invention of the tributary modes of accumulation. That

this transition has occurred independently several times in human history

indicates that it is part of a regular process of socio-cultural evolution (Sanderson 1999; Chase-Dunn and Lerro forthcoming; Hall and

Chase-Dunn 2006).

In our 1997 book, Rise

and Demise, we characterized

Taxation, tribute-gathering and rents from landed

property were the mainstays of the state and the ruling class. Paper money was used in Sung China in the 10th

century CE. But the state and the ruling class of mandarins, or the

marcher-state usurpers who sometimes came to power, were mainly dependent on

the use of state coercion to extract surplus product from the direct producers.

This is rather different from a capitalist system in which profit-making and

the appropriation of surplus value through employment of wage labor has become

the mainstay of the state and the ruling class.

In Volume 1 of The

Modern World-System Immanuel Wallerstein (1974) noted a key difference

between

This explanation was rejected as so much Eurocentric

claptrap by Frank, because Max Weber and Karl Marx had said as much, and they

needed to be thrown into the dustbin of Eurocentrism with all the other dead

white guys. In Adam Smith Giovanni

Arrighi, reviews and recasts the recent work on Chinese economic history that

has been partly inspired by Gunder Frank’s analysis (e.g. Bin Wong 1997; Kenneth

Pomeranz 2000; Kaoru Sugihara 2003) These

authors show extensive markets, commodity production, buyer-driven commodity

chains, etc. in China and confirm that Chinese economic institutions in 1900

were not inferior to those of the West.

Arrighi (2007) ends up with the conclusion that the key question is “who

controls the state?” In

One may ask what happened to capitalist efforts to gain

state power in

Giovanni Arrighi’s Adam

Smith in Beijing is dedicated to Andre Gunder Frank and Frank’s influence

is obvious throughout. Arrighi does not accept Frank’s blanket rejection of the

distinction between the tributary mode of accumulation and the capitalism mode

of accumulation. In The Long Twentieth

Century Arrighi describes

Both Frank and Arrighi share the conviction that

Arrighi contends that the kind of market society that is

said to be emerging in

Arrighi further contends that

The notion that China concentrated only on domestic

problems after the Ming abandonment of the treasure fleets is contradicted by

Peter Perdue’s (2005) careful study of Qing expansion in Central Asia, and the

notion that China is an exemplar of contemporary egalitarianism in relations

with the periphery is contradicted by the situation in Tibet and by many

observers of Chinese projects in Africa. While we do not condone China-bashing,

and we agree with Arrighi that China is a somewhat more progressive force in

world society than many other powerful actors, (including the current U.S.

regime) the idea that adoption of the Chinese model of political economy,

so-called market society, can be the main basis of a more egalitarian, just,

and sustainable form of global governance is a bit of a stretch. On the other

hand there are important elements of the idea of market society that probably

are quite relevant for a formulation of what should be the goals of

contemporary progressives, and that are possibly achievable during the twenty-first

century. (more below).

World

Revolutions and

As far as we know the idea of world revolutions was first developed by Terry Hopkins, Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi in their 1989 book Antisystemic Movements (Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein 1989). The idea is that the structure of global governance in the modern world-system evolves because of competition among core states for hegemony and because subordinated groups of people resist oppression and domination. These latter forms of resistance coalesce when local and national social movements, uprisings, rebellions and revolutions cluster in time, and as these subordinate groups increasing become connected to one another across space. Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein (1989) analyzed the world revolutions of 1848, 1917, 1968 and 1989. They contend that the demands put forth in a world revolution do not usually become institutionalized until a consolidating revolt has occurred, or until the next world revolution. So the revolutionaries appear to have lost in the failure of their most radical demands, but enlightened conservatives who are trying to manage hegemony end up incorporating the reforms that were earlier radical demands into the current world order.

Up until the nineteenth centuries movements of

resistance in the East and the West were mainly disconnected with one another.

In

Rerise of the

Global Left

We agree with Arrighi that the current rise of

The world revolution of “20xx” (twenty dos equis) is

going on now (Chase-Dunn 2008). There are many continuities with earlier

revolutions, and we substantially agree with Arrighi’s specification of how the

decline of

The family of antisystemic movements in the global

justice movement of movements has achieved some recent successes, and has

endured some failures. There has not been much in the way of domestic violence

or divorce, but some new relatives have appeared and some of these either want

to move into the house or refuse to do so. Nevertheless, a multicentric and

strongly linked network of movements has emerged in the context of the World

Social Forum process (Chase-Dunn et al

2007). The labor movement is no longer hegemonic on the Left, even in its own

eyes. Most of the labor activists in the global justice movement now see a big

tent in which labor plays an important role, but is only one of several other

important players (Santos 2006).

What Exactly

is Wrong with Capitalism?

The ideological hegemony of neoliberalism has been a

useful foil for encouraging social movements and NGOs to scale up their

activities -- to become more transnational and to form global networks of

opposition. If a problem is obviously

not resolvable at the local or national level, people will make larger

coalitions and create global networks, as many (but not all) have done (Reitan

2007).

But the neoliberal boogeyman has also created some

problems for the orientation of the movements.

Because neoliberals use “market magic” as a justification for attacking

and dismantling all institutions that operate to protect the interests of

workers or the poor, this encourages movement leaders and writers to go back to

railing about commodification and commercialism, as the Marxist left has done

in the past. Karl Polanyi’s works on the negative properties of disembedded markets

have had an understandable resurgence of popularity. Some of this is good

because it gives people a way to resist the arguments of the neoliberal

ideologues. And some of it is good because the notion fair trade is a valuable part

of local and North/South altruistic solidarity. But it would be unwise to carry

the anti-market sentiment as far as was done in the

This raises the issue of what is really wrong with

capitalism. Most Leftist agree that capitalism destroys the environment,

exacerbates social inequalities and leaves vast numbers of people in extreme

poverty and bad health. But what is it about the institutional features of

capitalism that cause these negative outcomes?

For his analyses of the evolution of hegemony Giovanni

Arrighi has adopted a Braudelian understanding of capitalism that contrasts the

local market economy (which is not capitalism) with haute finance, which is capitalism. We agree with the part about

the relative worthiness of small commodity production. But we think that a contemporary political

analysis needs to once again also consider the issue of the institutional

nature of property. Private property in

the major means of production (meaning large private firms) is an important

institutional form of modern capitalism. No one now advocates the expansion of

state-owned firms as the solution to the problems created by capitalism because

the

As we have said above, Giovanni Arrighi suggests in Adam Smith that a more benign form of

market economy is emerging in

The Chinese use the term “market socialism” to describe

there own model. At present this seems to mean a state managed by the Communist

Party and a market society in which private ownership of the major means of

production is allowed.

Whether or not

This said, we think that simply extended social democracy

to the global level as advocated by the LSE scholars and others, does not

address the more fundamental issues of economic democracy that must be

addressed in moving toward a more just and sustainable world society. Boswell

and Chase-Dunn (2000) outlined a modified version of John Roemer’s model of

market socialism in which capital itself is socialized (see also Loy

Forthcoming).

Left cosmopolitans are advocating globalization from

below, while indigenous peoples and some neo-anarchists and autonomists simply

want self-reliance and the right to do what they want to do without

interference. These are huge issues and they reverberate in East-West

relations. There has been very little participation by people from the People’s

Republic of

Multilateral

Global Governance

Though

Arrighi does not specifically address the issue of hegemonic evolution, it is a

topic that his analysis of the past of and of

We

extend Arrighi’s analysis of the evolution of hegemony in the following way.

The next hegemon will not be a single state and neither will it be the European

Union, which is about the same size economically as the

Bibliography

Anderson, E. N. and Christopher Chase-Dunn “The

Rise and Fall of Great Powers” in

Christopher Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) 2005. The Historical

Evolution of World-Systems.

Anthony, David W. 1998.

“The Opening of the Eurasian Steppe at 2000 BCE.” Pp. 94-113 in The Bronze Age

and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern Central Asia, edited by Victor Mair, Vol.

1.

Appelbaum, Richard and

William I. Robinson (eds.) Critical

Globalization Studies.

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth Century.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Takeshi Hamashita, and Mark

Selden 2003 The Resurgence of

500, 150 and 50 Year Perspectives.

Arrighi, Giovanni. 2006. “Spatial and other

‘fixes’ of historical capitalism” Pp. 201-212 in C., Chase-Dunn and Salvatore

Babones (eds.) Global Social Change: Historical and Comparative Perspectives.

_____. 2007 Adam Smith in

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K. Hopkins and Immanuel

Wallerstein. 1989. Antisystemic Movements.

Arrighi, Giovanni and

Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos and Governance

in the Modern World-

System: Comparing Hegemonic Transitions.

Barfield, Thomas

J. 1989. The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic

Empires and

_____. 1992. “Response to Frank’s Centrality of

Central Asia.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 24:2(April-June):76-79.

_____. 2001a. “Steppe Empires,

_____. 2001b.

“The Shadow Empires:

Beckwith,

Bentley, Jerry

H. 1993.

Bergesen,

Albert and Ronald Schoenberg 1980 “Long waves of colonial expansion and

contraction 1415-1969” Pp. 231-278 in Albert Bergesen (ed.) Studies of the

Modern World-System.

Boli, John and George M. Thomas (eds.) 1999 Constructing world culture : international

nongovernmental

organizations since 1875

Boswell, Terry and Christopher

Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral of Capitalism

and

Socialism: Toward Global Democracy.

_____. 2000 "From state socialism to global

democracy: the transnational politics of the modern world-system." Pp.

289-306 in Thomas D. Hall (ed.) A World-Systems Reader: New Perspectives on

Gender, Urbanism, Cultures, Indigenous Peoples, and Ecology.

Bunker, Stephen and Paul

Ciccantell. 2004. Globalization and the Race for Resources.

MD:

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher. 1990 "World state formation: historical processes and

emergent necessity" Political Geography Quarterly, 9,2: 108-30

(April).

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

1998 Global Formation: Structures of the

World-Economy (2nd

ed.)

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 1999. "Globalization:

A World-Systems Perspective" Journal of World-Systems Research

5:2:165-185.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 2005. “Global public

social science.” The American Sociologist

36,3-4:121-132 (Fall/Winter). Reprinted

Pp. 179-194 in

(ed.)

Public Sociology: The Contemporary Debate.

Transnaction

Press.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher 2007. “Sociocultural

evolution and the future of world society.”

World

Futures 63,5-6:408-424.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher 2008 “The

World Revolution of 20xx” Jerry Harris

(ed.) GSA Papers 2007: Contested

Terrains of Globalization.

ChangeMaker.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and E.N. Anderson (eds.)

2005. The

Historical Evolution of World-Systems.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Salvatore Babones. 2007.

Global Social Change.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and

Terry Boswell 1999 "Postcommunism

and the Global

Commonwealth" Humboldt Journal of Social

Relations 24,1-2: 195-219.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Bruce Lerro

Forthcoming, Social Change.

Bacon.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and

Thomas D. Hall 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems.

Boulder, CO.: Westview.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Thomas Hall, & Peter Turchin. 2007.

“World-Systems in the Biogeosphere: Urbanization, State Formation, and Climate

Change Since the Iron Age.” Pp.132-148 in The

World System and the Earth System: Global Socioenvironmental Change and

Sustainability Since the Neolithic, edited by Alf Hornborg and Carole L.

Crumley.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Hiroko Inoue, Alexis Alvarez, and Richard Niemeyer 2008 “Global State Formation In World Historical Perspective” in Yildiz Atasoy (ed). World Hegemonic Transformations, The State and Crisis in Neoliberalism. London York

Chase-Dunn, C. and

Andrew K. Jorgenson, “Regions and Interaction Networks: an

institutional materialist perspective,” 2003 International

Journal of Comparative

Sociology 44,1:433-450.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Andrew

Jorgenson and Thomas Reifer 2005 "The Trajectory of the

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 “Trade

globalization

since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system.”

American Sociological Review, February.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Susan Manning, and Thomas D. Hall. 2000. "Rise and Fall: East-West Synchronicity

and Indic Exceptionalism Reexamined."

Social Science History

24:4(Winter):727-754.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Susan Manning, 2002 "City systems and world-systems:

four millennia of city growth and decline," Cross-Cultural

Research 36, 4: 379-398 (November).

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher, Christine Petit, Richard Niemeyer, Robert A. Hanneman and Ellen

Reese 2007 “The Contours of Solidarity and Division Among Global

movements” International Journal of Peace Studies 12,2:1-15)

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and

Bruce Podobnik 1999 “The next world war: world-system cycles and trends” in Volker Bornschier and Christopher

Chase-Dunn (eds.) The

Future

of Global Conflict.

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Ellen Reese 2007 “Global party formation in world

historical perspective” Pp. 53-91 in

Katarina Sehm-Patomaki and Marlo Ulvila (eds.) Global Political Parties

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Alexis Alvarez, Hiroko Inoue, Richard Niemeyer, Anders

Carlson, Ben Fierro and Kirk Lawrence 2006 “Upward Sweeps of Empire and City

Growth Since the Bronze Age” IROWS Working Paper #22. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows22/irows22.htm

Chew, Sing 2001

World Ecological Degradation. Walnut

Cree, CA:

Christian,

David. Christian, David. 1998. A History

of

_____. 2004. Maps of Time.

Clark, Gregory 2008 “

Curtin, Philip 1984 Crosscultural Trade in World History. Cambrdige:

Danaher, Kevin (ed.) 2001

Democratizing the Global Economy: The

and the IMF.

Diamond, Jared.

1997. Guns, Germs, and

Steel: The Fates of Human

Societies.

Ekholm, Kasja and

Jonathan Friedman 1982 “’Capital’ imperialism and exploitation in the

ancient

world-systems” Review 6:1 (summer):

87-110.

Elvin, Mark. 1973. The Pattern of the Chinese Past.

Stanford:

Elvin, Mark 2004 The retreat of the elephants : an environmental history of

University

Press.

Engels, Frederic 1935 Socialism: Utopian and Scientific.

Fagan, Brian 2004 The Long Summer.

Fisher, William F. and

Thomas Ponniah 2003 Another World Is Possible.

Fitzpatrick, John. 1992. "The Middle Kingdom,

the

Florini, Ann 2005 The

Coming Democracy: New Rules for Running A

Frank, Andre Gunder. 1989. “Transitions and modes:

in imaginary Eurocentric Feudalism, Capitalism and Socialism, and the the Real

World System History.”

Frank, Andre Gunder.

1992. "The Centrality of

Number 8.

Frank, Andre Gunder 1998 Reorient: Global Economy in the Asian Age.

Berkeley, CA.:

Frank, Andre

Gunder and Barry K. Gills (eds.) 1993 The World System: Five Hundred Years

or Five Thousand ?

Friedman, Jonathan and Christopher Chase-Dunn

(eds.) 2005. Hegemonic Declines: Present and Past. Boulder, CO.:

Paradigm Press.

Gill, Stephen 2000

“Toward a post-modern prince? : the battle of

new politics of globalization” Millennium 29,1: 131-140

Hall, Thomas D. 2001. 2001. "Chiefdoms, States, Cycling, and

World-Systems Evolution: A Review Essay." Journal of World-Systems

Research 7:1(Spring):91-100 [E-Journal http://jwsr.ucr.edu/index.php].

_____. 2005. “Mongols in World-System History.”

Social Evolution & History 4:2(September): 89-118.

_____. 2006. “[Re] Periphalization,

[Re]Incorporation, Frontiers, and Nonstate Societies: Continuities and

Discontinuities in Globalization Processes.” Pp. 96-113 in Globalization and

Global History edited by Barry K. Gills and William R. Thompson.

Hall, Thomas D. and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2006.

“Global Social Change in the Long Run.” Pp.33-58 in Global Social Change: Comparative

and Historical Perspectives, edited by Christopher Chase-Dunn, Salvatore

Babones.

Harvey, David 2003 The New Imperialism.

Hawley, Amos. 1950. Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure.

Held, David and Anthony

McGrew 2002 Globalization/Antiglobalization.

Hobsbawm, Eric 1994 The Age of Extremes: A History of the World,

1914-1991. New

Honeychurch, William and Chunag Amartuvshin. 2006.

“States on Horseback: The Rise of Inner Asian Confederations and Empires.” Pp.

255-278 in Archaeology of Asia,

edited by Miriam T. Stark.

Hung, Ho-Fung 2001 “Maritime capitalism in

seventeenth-century

_____________2005 “Contentious peasants,

paternalist state and arrested capitalism in

Historical

Evolution of World-Systems.

Johnson,

Chalmers 2000 Blowback: The Costs and

Consequences of American Empire.

Henry Holt.

Kaldor,

Mary 2003 Global Civil Society: An Answer

to War.

Keck, Margaret E. and

Kathryn Sinkink 1998 Activists Beyond

Borders: Advocacy

Networks in International Politics.

Kirch, Patrick V. 1984 The Evolution of

Polynesian Chiefdoms.

Koenig-Archibugi, Mathias 2008 “Is global

democracy possible?” A paper presented at the annual meeting of the

International Studies Association,

Kradin,

Nicholai. 2002. “Nomadism, Evolution and World-Systems: Pastoral Societies in Theories of Historical

Development.” Journal of World-Systems Research 8:3(Fall):368-388 [ejournal

http://jwsr.ucr.edu/index.php].

Kradin, Nikolay

N., Dmitri M. Bondarenko, Thomas J. Barfield, eds. 2003. Nomadic Pathways in Social Evolution. The Civilization Dimension Series, Vol. 5.

Lattimore,

Owen. 1940. Inner

Asian Frontiers of

_____. 1962. Studies in Frontier History: Collected Papers, 1928-58.

_____. 1980.

"The Periphery as Locus of Innovations." Pp. 205-208 in Centre and Periphery: Spatial

Variation in Politics, edited by Jean Gottmann.

Lee, J. S. 1931. “The Periodic Recurrence of

Internecine Wars in

Lee, J. S. (1933) in Studies Presented to Ts’ai

Yuan P’ei on His Sixty-fifth Birthday Part I, ed. Fellows and Assistants of

the Institute of History and Philology (

Levine, Marsha, Colin Renfrew & Katie Boyle,

eds. 2003. Prehistoric Steppe Adaptation

and the Horse. McDonald Institute Monographs.

Linduff, Katheryn M. 1998. “The Emergence and

Demise of Bronze-Producing Cultures Outside the Central Plain of

_____. 2003. “A Walk on the Wild Side: Late Shang

Appropriation of Horses in

Linebaugh, Peter and

Marcus Rediker. 2000. The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners

and the Hidden History of the

Revolutionary

Liu, Xinru and Lynda Norene Shaffer. 2007. Connections across

Loy, Patrick Forthcoming “

Mair, Victor H., ed. 1998. The Bronze Age &

Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern

Mair, Victor H. 2003. “The Horse in Late

Prehistoric

Mair, Victor H. ed. 2006. Contact and Exchange in

the Ancient World.

Martin, William G. et

al Forthcoming. Making Waves: Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005.

Mander, Jerry and Edward

Goldsmith (eds.) The Case Against The

Global Economy: and

For a Turn Toward the Local.

Markoff, John 1996 Waves of Democracy: Social Movements and

Political Change.

CA.: Pine Forge Press.

_____. 2006 “Globalization and the future of

democracy” Pp. 336-362 in C. Chase-Dunn and S. Babones, Global Social Change.

McMichael, Philip 1996 Development and Social Change: A Global

Perspective.

McNeill, William H. 1982. The Pursuit of Power: Technology, Armed Force, and Society since A.D. 1000.

McNeill, J.R. and William

McNeill 2003 The Human Web.

Modelski, George 2003

Modelski, George and William R. Thompson. 1996. Leading Sectors and

World Powers: The Coevolution of Global Politics and Economics. Columbia,

SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Moghadam, Valentine 2005 Globalizing Women.

Press.

Monbiot, George 2003 Manifesto for a

Murphy, Craig 1994

International Organization and Industrial

Change: Global Governance since 1850.

Pomeranz, Kenneth 2000 The Great Divergence:

Europe,

Economy. Princeton:

Puett, Michael. 1998. “

Purdue, Peter C. 2005

Rediker, Marcus B.

2007. The Slave Ship.

Renfrew, Colin. 2001. “The Indo-European Problem

and the Exploitation of the Eurasian Steppes: Questions of Time Depth.” Pp.

3-18 in Complex Societies of Central

Eurasia from the 3rd to the 1st Millennium BC: Regional Specifics in Light of

Global Models, V1 edited by Karlene Jones-Bley and D. G. Zdanovich.

Washington, D.C. Institute for the Study of

Reitan, Ruth. 2007. Global

Activism.

Robinson, William I 1996 Promoting Polyarchy: Globalization, US Intervention and

Hegemony.

_____. 2004 A Theory

of Global Capitalism.

University Press.

Roemer, John 1994. A Future for Socialism.

Ross, Robert and Kent Trachte 1990 Global Capitalism: The New Leviathan.

Rueschemeyer, Dietrich,

Evelyn Huber Stephens and John D. Stephens 1992

Capitalist Development and Democracy.

Sanderson,

Stephen K. 1990 Social Evolutionism.

_____. 1999. Social Transformations: A General

Theory of Historical Development, expanded edition.

_____.

2007 Evolutionism and Its Critics.

Santiago-Valles, Kelvin.

2005. “World historical ties among “spontaneous” slave rebellions

in the

Sassen, Saskia. 2006. Territory Princeton , NJ: Princeton University

Scholte, Jan Aart.

2004. “Civil society and democratically accountable global governance.” Government and Opposition 39(2):211-233.

Sen, Jai and Madhuresh Kumar with Patrick Bond and Peter Waterman. 2007. A Political Programme for the World Social Forum?: Democracy, Substance and Debate in the Bamako Appeal and the Global Justice Movements. Indian Institute for Critical Action : Centre in

Movement (CACIM), New Delhi , India & the University of KwaZulu-Natal Centre for Civil Society (CCS), Durban , South Africa

Sherratt, Andrew. 2003. “The Horse and the Wheel:

the Dialectics of Change in the Cirum-Pontic Region and Adjacent Areas,

4500-1500 BC.” Pp. 233-252 in Prehistoric Steppe

Adaptation and the Horse,

edited by Marsha Levine, Colin Renfrew & Katie Boyle. McDonald Institute

Monographs. Silver, Beverly 2003 Forces of Labor.

Shannon, Richard Thomas

1996 An Introduction to the World-systems

Perspective.

Silver,

waves, and cycles of hegemony," Review 18,1:155-92.

Silver, Beverly and Eric

Slater 1999 “The social origins of world hegemonies,” In

Arrighi

and Silver.

Smith, Jackie, Marina Karides, et al. 2007. The

World Social Forum and the Challenges of Global Democracy.

Smith, Monica.

2005. “Networks, Territories, and the Cartography of Ancient States,” Annals of the Association of American

Geographers 95:4:832-849.

So, Alvin. 1986. The South China Silk District: Local Historical Transformation and

World-System Theory.

So, Alvin Y.

1990. Social Change and Development:

Modernization, Dependency, and World-system Theory.

So, Alvin and

Stephen W.K. Chiu 1995

Stark, Miriam T., ed.

2006. Archaeology of

Starr, Amory. 2000. Naming

the Enemy: Anti-Corporate Movements Confront Globalization.

Zed Press.

Stevis, Dimitris and

Terry Boswell. 2007. Globalization and Labor. REST

Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2002 Globalization and its Discontents.

Tarrow, Sidney. 2005. The

New Transnational Activism.

Tausch, Arno 2007 “War

cycles” Social Evolution and History

6,2: 39-74 (September).

Teggart, Frederick

J. 1939.

Tilly, Charles 2007 Democracy.

Turchin, Peter, Jonathan M. Adams, and Thomas D.

2006. “East-West Orientation of Historical Empires and

Turchin, Peter and Thomas D. Hall. 2003. “Spatial

Synchrony among and within World-Systems:

Insights from Theoretical Ecology.” Journal

of World-Systems Research 9:1(Winter):37-64 [ejournal: http://jwsr.ucr.edu/index.php].

Turchin,

Peter and Sergey Nefadov n.d. Secular

Cycles.

http://www.eeb.uconn.edu/people/turchin/SEC.htm

Turner, Jonathan H. 1995 Macrodynamics.

Underhill, Anne P. and

Junko Habu. 2006. “Early Communities in

Urry, John 1999

“Globalization and citizenship” Journal of World-Systems Research, Vol.

V, 2: 311-324.

Wagar, W.

Press.

_____. 1996 “Toward a

praxis of world integration,” Journal of

World-Systems

Research 2:1. Http://csf.colorado.edu/wsystems/jwsr.html

Wallerstein, Immanuel

1974 The Modern World-System, Volume

1.

__________________1984.

“The three instances of hegemony in the history of the

capitalist world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in

Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and

Research in Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology and Social

Anthropology,

Vol. 37.

_____. 2000 The

Essential Wallerstein.

_____. 2004 World-Systems Analysis.

_____. 2007 “The World Social Forum: from defense

to offense”

http://www.sociologistswithoutborders.org/documents/WallersteinCommentary.pdf

Walton, John and David Seddon 1994 Free Markets and Food Riots: The Politics of

Global Adjustment

Waterman, Peter. 2006.

“Toward a Global Labor Charter Movement?” http://wsfworkshop.openspaceforum.net/twiki/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=6

Wilkinson, David. 1987 "Central civilization" Comparative Civilizations Review 17:31-59 (Fall).

_____. 1991 “Core, peripheries and civilizations,”

Pp. 113-166 in C. Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.) Core/Periphery Relations

in Precapitalist Worlds.

Winant, Howard 2001 The World Is A Ghetto.

Wilmer, Franke1993 The Indigenous Voice in World Politics.

Wong, R. Bin 1997