Upward

Sweeps of Empire and City Growth

Since

the Bronze Age

Chris Chase-Dunn, Alexis Alvarez,

Hiroko Inoue, Richard Niemeyer,

Anders Carlson, Ben Fierro and

Kirk Lawrence

Institute

for Research on World-Systems

Sociology,

Abstract: This

paper uses quantitative estimates of the sizes of cities and empires to

tentatively identify upward sweeps in

which uniquely large cities and empires emerged in the Central

Political/military network since the Bronze Age, and it formulates a causal

model to explain both the cyclical rise and fall of cities and empires and the

upward sweeps.

To be presented at the annual meeting of the American

Sociological Association Regular session on Globalization, Friday, August 11,

2006, 4:30 pm, Montreal. IROWS Working Paper #22

Draft v.8-7-06 6351 words

This paper is part of an NSF-funded project on the causes of the emergence of large states and empires since the Bronze Age.[1] Here we use quantitative estimates of the population sizes of cities and of the territorial sizes of states and empires to identify instances in which the scale of polities and settlements rapidly increase, a phenomenon that we call “upward sweeps.” Our project seeks to construct causal explanations of both the more usual cyclical rise and fall of large polities and cities and the less frequent instances in which much larger empires and cities emerge. The long-run evolutionary trend of the scale of human social organizations to expand needs to be studied in its particularities and comparatively so that we may explain how the processes of growth may be similar or different across large expanses of time.

Measuring Cities

and Empires

Research on upward sweeps depends on the accuracy of quantitative estimates of the population sizes of cities and the territorial sizes of states and empires. Reliably estimating these quantities tends to become more problematic the further we recede in time. In this paper we use quantitative estimates of the territorial sizes of the largest empires produced by Rein Taagepera in a series of studies published since the 1970s. [2]

And we use estimates of the population sizes of cities

produced by Tertius Chandler (1987).[3] These will produce tentative identifications

of upward sweeps of urban and empire growth that will be improved upon by using

more complete and accurate estimates in the next round of our investigation. It

is our eventual goal to enhance the Taagepera data by adding some large empires

that are missing from Taagepera’s data set (see Turchin, Adams and Hall 2006:

Table 1). And we can upgrade

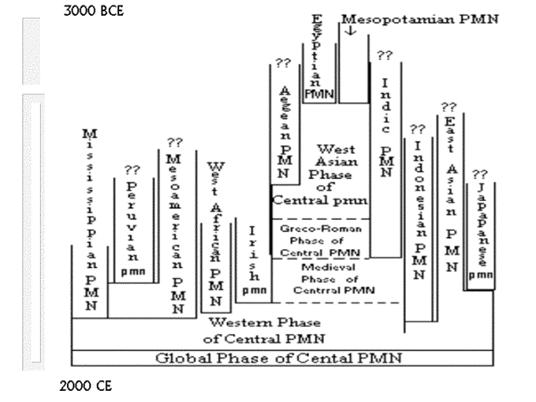

Whereas our

larger study will compare several different world regions[4] this

paper examines size estimates beginning in the Bronze Age of what we and David

Wilkinson call the Central System. Largely separate constellations of cities

and states emerged in Mesopotamia and

Figure 1: Chronograph of the Central System (following Wilkinson 1987)

Upward Sweeps

and Ceilings

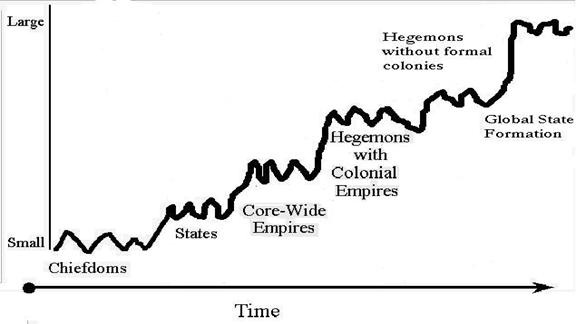

Figure 2 (below) is a stylized depiction of the rise and fall of large polities and occasional upward sweeps that portrays, not the history of a single world region, but rather the general evolution[5] of what has happened over the past 12,000 years as many small polities (bands, tribes and chiefdoms) have developed into a much smaller number of larger polities (states, empires and a possible future world state).

Figure 2: Rise, Fall and Upward Sweeps of Polity Size

George Modelski’s (2003) recent study of the growth of cities over the past 5000 years points to a phenomenon also noticed and theorized by Roland Fletcher (1995) – cities grow and decline in size, but occasionally a single new city will attain a size that is much larger than any earlier city, and then other cities catch up with that new scale, but do not much exceed it. It is as if cities reach a size ceiling that it is not possible to exceed until new conditions are met that allow for that ceiling to be breached.

This paper has two main purposes: 1. to empirically identify upward sweeps of city and empire growth in the Central System, and 2. to formulate a revised explanation of the cyclical patterns of rise and fall and the occasional upward sweeps of city and empire growth. First let us examine the sweeps.

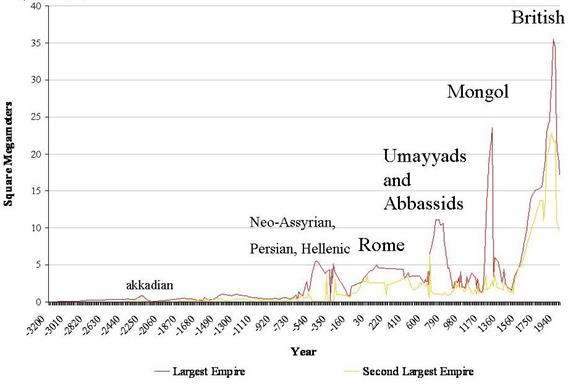

Figure 3

plots Taagepera’s estimates of the territorial sizes of the largest and second largest

empires in the Central System for the purpose of identifying empire upsweeps.

We know that the first upsweep was that of Uruk and the Uruk expansion that

began on the flood plain of Southern Mesoportamia (Algaze 1993), but we do not

have quantitative estimates of the settlement and empire sizes. After a long

period of competing city-states in

Figure 3: Rise, Fall and Upward Sweeps as revealed by

Taagepera's estimates of the territorial sizes of the largest empires in the

Central System

After the fall of the Akkadian

Empire there was a millennium of no comparably large states until

East/West Synchrony

Earlier research has demonstrated

the existence of a pattern that is probably relevant for figuring out the

causes of growth/decline cycles and upward sweeps. From about 500 BCE until about 1500 CE cities and

empires in East Asia and the West Asian/Mediterranean region were growing and

declining in the same periods, whereas intervening

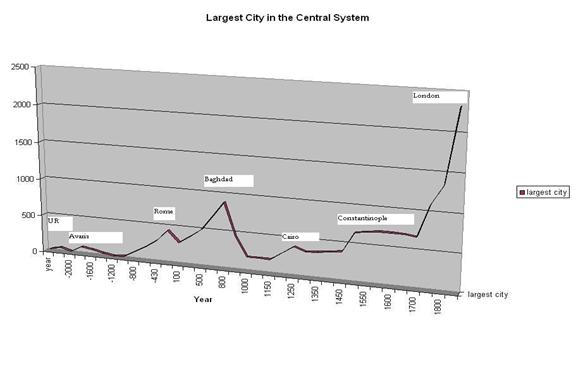

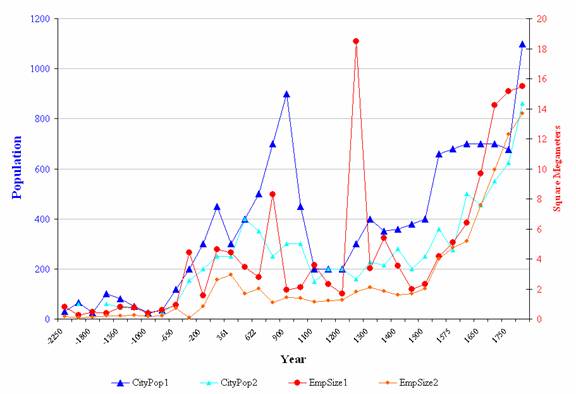

Figure 4: City Size Upsweeps in the Central System

Urban Upward

Sweeps

Figure 4

graphs the population size estimates of largest cities in the Central System.

We have no estimate of the size of

|

1875 |

|

4,241,000 |

|

2,250,000 |

|

1900 |

|

6,480,000 |

|

4,242,000 |

|

1914 |

|

7,419,000 |

|

6,700,000 |

|

1925 |

|

7,774,000 |

|

7,742,000 |

|

1950 |

|

12,463,000 |

|

8,860,000 |

|

1970 |

|

20,450,000 |

|

17,252,000 |

After the 1950s a new ceiling of around 20 millions is

reached by the largest urban agglomerations. Megacities in

Figure 5: The two largest cities in the Central System

Figure 5

graphs the largest and the second largest cities in the Central System. This

implies that the huge size of

Urban and

Empire Upsweeps

So what is the temporal relationship between city and empire upsweeps?

Figure 6 graphs together the two largest cities and the two largest empires from 2250 BCE to 1850 CE.

Obviously there is a long-term upward trend in both city and empire sizes, but are the medium term growth/decline phases correlated and do the upward sweeps occur in the same periods. Do large cities emerge before or after large empires do?

Figure 6: Two largest cities and empires in the Central System

|

Bivariate |

CityPop1 |

CityPop2 |

EmpSize1 |

EmpSize2 |

|

CityPop1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

CityPop2 |

0.991** |

1 |

|

|

|

EmpSize1 |

0.635** |

0.625** |

1 |

|

|

EmpSize2 |

0.542** |

0.519** |

0.937** |

1 |

Table 1: Bivariate Pearson's r correlation coefficients between largest cities and largest empires over time

Table 1 shows the Pearson’s r correlation coefficients over time between the largest and second largest cities and the largest and second largest empires. All the correlations are positive and statistically significant, but this could be due to the long-term growth trends.

|

Partial^ |

CityPop1 |

CityPop2 |

EmpSize1 |

EmpSize2 |

|

CityPop1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

CityPop2 |

0.989** |

1 |

|

|

|

EmpSize1 |

0.529** |

0.535** |

1 |

|

|

EmpSize2 |

0.397* |

0.390* |

0.896** |

1 |

|

^ Controlling for Decade |

|

|

* Significant at 0.05 |

|

|

** Significant at 0.01 |

|

Table 2: Partial correlations controlling for year

Table 2 shows the partial correlation coefficients after year is controlled. This is one way to try to take out the long-term trend and to see the more medium-term relations between growth/decline phases and upward sweeps. Though these coefficients are a bit smaller than those in Table 1 they are still positive and statistically significant. Notice that the partial correlations between the largest and second largest empires are also positive and significant.[8]

In Figure 6 above it appears that the upward sweeps of city and empire sizes do occur more or less together, but it is difficult to see any clear pattern of leads or lags. The issue of leads and lags is important for distinguishing between different causal processes, so we will return to it when we redo this analysis using improved estimates of city population sizes. If it is true that empire formation is the most important cause of urban upsweeps then empire upsweeps should regularly precede urban upsweeps.

Explaining

Upsweeps

Earlier work on socio-cultural evolution has produced a synthesized “iteration model” of the processes by which hierarchies and new technologies have emerged in regional world-systems since the Paleolithic (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 6). The iteration model assumes a system of societies that are interacting with one another in ways that are important for the reproduction and transformation of social structures and institutions. This comparative world-systems theory uses interaction networks rather than spatially homogenous characteristics to bound regional systems. Bulk goods exchanges are an important network in all systems, and so are alliances and conflicts among polities (the so-called political/military network – PMN). Some systems are importantly linked by the long-distance exchanges of prestige goods.

While Chase-Dunn and Hall used trade networks to spatially bound world-systems, they left trade out of the iteration model that explains why world-systems evolve. More recent works by McNeill and McNeill (2003) and Christian (2004) have stressed the importance of trade and communications networks in the processes of human cultural evolution. Both of these recent works employ a network node theory of innovation and collective learning that is similar to the human ecology approach developed earlier by Amos Hawley (1971). Innovations are said to be unusually likely to occur at transportation and communications nodes where information from many different sources can be easily combined and recombined.

One advantage of using world-systems as the explicit unit of analysis and of examining the possibility that world-systems may be organized by core/periphery structures is that it allows us to see that there are important and repeated exceptions to the network node theory of innovation. It is often societies out on the edge of a system rather than at the center that either innovate or that successfully implement new strategies and technologies of power, production and trade. Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997: Chapter 5) synthesize earlier formulations into a theory of semiperipheral development in which a few of the societies that are in between the core and the periphery of a system are the ones that are most likely to come forth with strategies and behaviors that produce evolutionary transformations and upward mobility. This phenomenon takes various forms in different kinds of systems: semiperipheral marcher chiefdoms, semiperipheral marcher states, semiperipheral capitalist city states, the semiperipheral position of Europe in the larger Afroeurasian world-system, modern semiperipheral nations that arise to hegemony, and contemporary semiperipheral societies that engage in and support novel and potentially transformative economic and political activities.

The network node theory does not well account for the spatially uneven nature of evolutionary change. The cutting edge of evolution moves. Old centers are often transcended by societies out on the edge that are able to rewire network nodes in a way that expands the spatial scale of networks.

There are several possible processes that might account for the phenomenon of semiperipheral development.[9] Randall Collins (1999) has argued that the phenomenon of marcher states conquering other states to make larger empires is due to the marcher state advantage. Being out on the edge of a core region of competing states allows more maneuverability because it is not necessary to defend the rear. This geopolitical advantage allows military resources to be concentrated on vulnerable neighbors. Peter Turchin (2005) argues that the relevant process is one in which group solidarity is enhanced by being on a “metaethnic frontier” in which the clash of contending cultures produces strong cohesion and cooperation within a frontier society, allowing it to perform great feats. Carroll Quigley (1961) distilled a somewhat similar theory from the works of Arnold Toynbee.

But Toynbee also suggested another way in which semiperipheral regions might be motivated to take risks with new ideas, technologies and strategies. Semiperipheral societies are often located in ecologically marginal regions that have poor soil and little water or other disadvantages. Patrick Kirch relies on this idea of ecological marginality in his depiction of the process by which semiperipheral marcher chiefs are most often the conquerors that create island-wide paramount chiefdoms in the Pacific (Kirch 1984). It is quite possible that all these features combine to produce what Alexander Gershenkron called “the advantages of backwardness” that allow some semiperipheral societies to transform and to dominate regional world-systems.

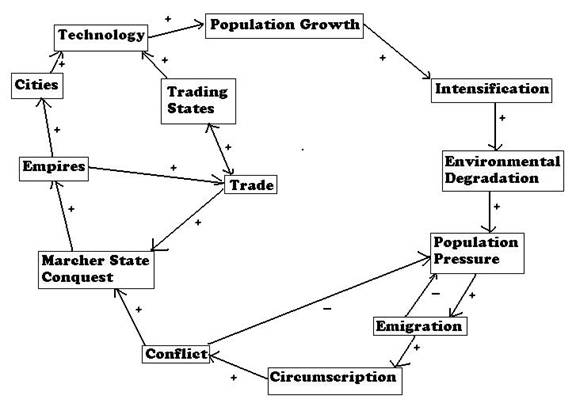

Iteration Revised

For the purposes of explaining upward sweeps we have reformulated the iteration model to focus on state-based systems[10] by adding trade, marcher states, capitalist city states, cities and empires (see Figure 7). The top and right side of the revised iteration model is unchanged. Here we have the basic ideas from Marvin Harris and Robert Carneiro as reformulated by Allen Johnson and Timothy Earle (1987) regarding population growth, intensification, environmental degradation, population pressure, emigration, circumscription and conflict.[11] This is a general model of the population ecology and the demographic regulator that works for humans as well as for other animal populations. Human world-systems that are unable to evolve larger polities, hierarchies and/or new technologies of production get stuck in the “nasty bottom” of the iteration model (Kirch 1991), and systems that expand beyond their institutional capabilities collapse back to the nasty bottom (Diamond 2004).

Figure 7: Revised Iteration Model For Empire and City Upsweeps in State-based Systems

In state-based systems periods of intensified conflict

within and between societies lower the resistance to hierarchy formation. A

semiperipheral marcher state can “roll up the system” under such circumstances.

Thus did the Neo-Assyrians, the Achaemenid Persians, Alexander, the Romans, the

Islamic Caliphates and the Aztecs produce the core-wide empires that constitute

the great upward sweeps of state size in the age of state-based systems.

During the Bronze and Iron Age expansions of the

tributary empires a new niche emerged for states that specialized in the

carrying trade among the empires and adjacent regions. These semiperipheral

capitalist city states were usually “thalassocratic” entities that used naval

power to protect sea-going trade (e.g. the Phoenician city-states,

The expansion of trading and communications networks

facilitated the growth of empires and vice versa. The emergence of agriculture,

mining and manufacturing production of surpluses for trade gave conquerors an

incentive to expand state control into distant areas. And the apparatus of the

empire was itself often a boon to trade. The specialized trading states

promoted the production of trade surpluses, bringing peoples into commerce over

wide regions, and thus they helped to create the conditions for the emergence

of larger empires.

Capitalist

city-states and ports of trade

Sabloff and

Rathje (1975) contend that the same settlement can oscillate back and forth

between being a “port of trade” (neutral territory that is used for

administered trade between different competing states and empires – see Polanyi

et al 1957) and a “trading port” (an autonomous and sovereign polity that

actively pursues policies that facilitate profitable trade). This latter

corresponds to what Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997) mean by a semiperipheral

capitalist city-state. Sabloff and

Rathje also contend that a trading port is more likely to emerge during a

period in which other states within the same region are weak, whereas a port of

trade is more likely during a period in which there are large strong states.[12]

The archaeological investigation of Cozumel carried out by Sabloff and Rathje

was designed to try to test the hypothesis that

This

general idea also corresponds with the notion that world-systems oscillate

between periods in which they are more integrated by horizontal networks of

exchange versus periods in which corporate and hierarchical organization is

more predominant (Ekholm and Friedman 1982; White, Kejzar and Tambayong 2006). Arrighi

(1994) contends that modern “systemic cycles of accumulation” display a

somewhat similar alternation, with the Genoese-Portuguese network based cycle

followed by a more corporate Dutch organized cycle and that by a more

network-based British cycle and then a more corporate

So what does this have to do with upward sweeps of empires and upward sweeps of city sizes? Regarding upward sweeps of empires, if semiperipheral capitalist city states were major agents of the spread of commodified exchange and the expansion and intensification of trade then upward sweeps in which larger states emerged to encompass regions that had already been unified by trade should have occured after a period in which semiperipheral capitalist city-states have been flourishing.

Regarding

upward sweeps of city sizes, these should have followed upward sweeps of empire

sizes because it was empires that created the largest cities as their capitals.

The settlements of semiperipheral capitalist city-states were typically smaller

than the capital cities of empires. It was not until the rise of

References

Abu-Lughod, Janet Lippman 1989 Before European

Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350

Algaze, Guillermo 1993 The

Uruk World System.

Anderson, David G. 1994 The

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The

Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times.

Bairoch, Paul 1988 Cities

and Economic Development.

Barabási, A.-L. 2002. Linked: The New Science of Networks.

Barfield, Thomas J.

1989. The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and

Bentley, Jerry H. 1993.

Bergesen, Albert and Ronald Schoenberg 1980 “Long waves of colonial

expansion and contraction 1415-1969” Pp. 231-278 in

Albert Bergesen (ed.) Studies

of the Modern World-System.

Boserup, Ester1981. Population

and Technological Change.

Braudel, Fernand 1979 The

Perspective of the World.

Carneiro, Robert L. 1978

“Political expansion as an expression of the principle of competitive

exclusion,” Pp. 205-223

in Ronald Cohen and

Elman R. Service (eds.) Origins of the State: The Anthropology of Political

Evolution.

Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

________ 2004 “The

political unification of the world: whether, when and how – some speculations.”

Cross-Cultural Research 38,2:162-177 (May).

Christopher Chase-Dunn. 1990 "World state

formation: historical processes and emergent necessity"

Political

Geography Quarterly, 9,2: 108-30 (April). https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows1.txt

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Thomas D. Hall. 1997 Rise and Demise: Comparing World-Systems

Boulder, CO.: Westview

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Alexis Alvarez, Andrew Jorgenson, Richard Niemeyer, Daniel

Pasciuti and John Weeks 2006 “Global City Networks in

World Historical

Perspective To be presented at the session on “Cities in

the Political Economy of

Global Capitalism” organized by Mike Timberlake and

sponsored by the Section on

Community and Urban Sociology and the Section on

Political Economy of World-

Systems at the annual meeting of the American Sociological

Association,

8:30 am Monday, August 14, 2006. IROWS Working Paper #28

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows28/irows28.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and E. Susan Manning 2002 “City

systems and world-systems: four millennia of city growth an decline.”

Cross-Cultural

Research 36,4:379-398.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Alexis Alvarez, and Daniel Pasciuti 2005 "Power and

Size; urbanization and empire formation in world-systems"

Pp. 92-112 in C. Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The

Historical Evolution of World-Systems.

Chase-Dunn, C., Richard Niemeyer, Alexis Alvarez,

Hiroko Inoue, Kirk Lawrence, and Anders Carlson 2006

“When North/South relations were East/West: urban

and empire synchrony, 500 BCE-1500 CE”

Presented at the annual meetings of the

International Studies Association,

Christian, David 2004 Maps of Time.

Cioffi-Revilla, Claudio 1996 “Origins and Evolution of War and Politics,”International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 40, no. 1, March pp. 1-4.

Collins, Randall 1999 Macrohistory: Essays in

the Sociology of the Long Run.

Denemark, Robert, Jonathan Friedman, Barry K.

Gills and George Modelski (eds.) 2000

World System History: the social science of

long-term change.

Diamond, Jared 2004 Collapse.

Ekholm, Kasja and Jonathan Friedman 1982 “’Capital’ imperialism and exploitation in the ancient world-systems” Review 6:1 (summer): 87-110.

Fischer, David Hackett

1996 The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History.

Fletcher, Roland 1995 The

Limits of Settlement Growth.

Fletcher, Roland n.d. “Compilation of city size

and area estimates”

Frank, Andre Gunder and Barry K. Gills (eds.) 1993

The World System: Five Hundred Years or Five Thousand ?

Friedman, Jonathan and Michael Rowlands 1977 "Toward an

epigenetic model of the

evolution of

'civilization.'" Pp. 201-78 in J. Friedman and M. Rowlands (eds.) The Evolution of Social Systems.

Galloway, Patrick R. 1986 “Long-term fluctuations

in climate and population in the preindustrial era.”

Population and Development Review 12,1:1-24 (March).

Goldfrank, Walter L. 1999

“Beyond hegemony” in Volker Bornschier and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.)

The Future of Global

Conflict.

Gimblett, Randy 2001 Integrating Geographic

Information Systems and Agent-Based Modeling: Techniques for Simulating

Social and Ecological Processes

Goldstone, J. A. 1991.

Revolution and rebellion in the Early Modern world.

Graber, Robert Bates 2004

“Is a world state just a matter of time?: a population-pressure alternative.” Cross-Cultural Research

38,2:147-161 (may).

Hanneman, Robert A. 1988-89 Computer Assisted

_________1995 "Discovering Theory Dynamics by

Computer Simulation: Experiments on State Legitimacy and Capitalist

Imperialism."

Pp. 1-46 in Peter Marsden (ed.) Sociological Methodology (with Randall Collins and Gabrielle Mordt).

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri 2004 Multitude. New York

Harris,

Marvin. 1977. Cannibals and Kings: The Origins of Cultures.

Hawley, Amos 1971 Urban

Society: an ecological approach.

Johnson, Allen W. and Timothy Earle. 1987. The

Evolution of Human Societies: From Foraging Group to

Stanford:

Johnson, Amber Lynn 2004 “ Why not to expect a “world state.” Cross-Cultural Research 38,2: 119-132 (May).

Kirch,

Patrick V. 1984 The Evolution of Polynesian Chiefdoms.

_________ 1991 “Chiefship and competitive

involution: the Marquesas Islands of Eastern Polynesia”

Pp.

119-145 in Timothy Earle (ed.) Chiefdoms: Power, Economy and Ideology.

Larsen, Mogens T. 1976 The

Lattimore, Owen. 1940. Inner Asian Frontiers of

republished 1951, 2nd ed.

Lenski, Gerhard 2005 Ecological-Evolutionary

Theory.

Levy, Jack S. and William R. Thompson 2005 The

Evolution of War.

Li, B. L. and E. L. Charnov. 2001.

Diversity-stability relationships revisited: scaling rules for biological

communities near equilibrium. Ecological Modelling, 140: 247-254.

Marano, Louis A 1973 “A macrohistoric trend toward world government.” Behavior Science Notes 8,1, 35-39

Mann, Michael. 1986. The sources of

social power: Volume I: A history of power from the beginning to

a.d. 1760.

McNeill, J.R. and William McNeill 2003 The

Human Web.

Modelski,

George 2003

Modelski, G., W. R. Thompson. 1996. Leading sectors and world powers: the co-evolution of global politics and economics.

Murphy, Craig

1994 International Organization and Industrial Change: Global Governance since

1850.

Naroll, Raul 1967 “Imperial cycles and world order,” Peace Research Society: Papers, VII, Chicago Conference, 1967: 83-101.

O’Rourke, Kevin H and Jeffrey G. Williamson 1999 Globalization and History: The Evolution of a 19th Century Atlantic Economy.

Pasciuti, Daniel and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2002 “Estimating the population sizes of

cities.” https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/estcit/estcit.htm

Peregrine, Peter N., Melvin Ember and Carol R. Ember 2004 “Predicting the future state

of the world using archaeological data: an exercise in archaeomancy.” Cross-

Cultural Research 38,2: 133-146 (may).

Polanyi, Karl.

1944. The Great Transformation: The

Political and Economic Origins of Our Time.

_____ Conrad M.

Arensberg, and Harry W. Pearson (eds.) 1957.Trade and Market in the Early

Empires

Quigley, Carroll 1961 The Evolution of Civilizations.

Roscoe, Paul 2004 “The

problems with polities: some problems in forecasting global political

integration.” Cross-Cultural Research 38,2:102-11.

Redman, Charles L. 1999 Human

Impact on Ancient Environments.

Roys, Ralph L. 1957 The

Political Geography of the

Sabloff, Jeremy and William J. Rathje 1975 A Study of Changing Pre-Columbian Commercial Systems.

Sanderson, Stephen K.

1990 Social Evolutionism.

Sassen, Saskia. 1991. Global

Cities. Princeton:

Silver, Beverly 2003 Forces

of Labor.

Scheidel, Walter n.d. THE STANFORD ANCIENT CHINESE AND

MEDITERRANEAN EMPIRES

COMPARATIVE HISTORY PROJECT (ACME) http://www.stanford.edu/~scheidel/acme.htm

Spufford, P. 2002, Power

and Profit: The Merchant in Medieval

Taagepera,

Rein 1978a "Size and duration of empires: systematics of size"

Social Science Research 7:108-27.

______

1978b "Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600

B.C." Social Science Research, 7 :180-96.

______1979

"Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 600 B.C. to 600

A.D." Social Science History 3,3-4:115-38.

_______1997

“Expansion and contraction patterns of large polities: context for

Taylor, Peter J. 1996 The Way the Modern World

Works: World Hegemony to World Impasse .

Teggart, Frederick J. 1939.

Tilly, Charles 1990 Coercion, Capital and

Tobler, Waldo and

Turchin, P. 2003. Historical dynamics: why states rise and

fall.

Turchin, Peter 2005 War and Peace and War: The Life Cycles of

Imperial Nations.

Turchin, P., and T. D. Hall. 2003. Spatial synchrony among and within world-systems: insights from theoretical ecology.

Journal of World Systems Research 9,1 http://csf.colorado.edu/jwsr/archive/vol9/number1/pdf/jwsr-v9n1-turchinhall.pdf

Turchin, Peter, Jonathan M. Adams, and Thomas D. Hall forthcoming

“East-West Orientation of Historical

Empires and

Journal of World-Systems Research.

Thompson, William R. 1990 "Long waves, technological innovation and relative decline." International Organization 44:201-33.

________________ (ed.) 2001 Evolutionary

Interpretations of World Politics.

Van der Pijl, Kees. 1984. The Making of an

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984. “The

three instances of hegemony in the history of the capitalist

world-economy.”

Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current

Issues and Research in Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology

and Social

Anthropology, Vol. 37.

________________ 2000 The Essential

Wallerstein.

Wendt, Alex 2003 “Why a world state is inevitable” European Journal of International Relations. 9,4: 491-542.

White, Douglas R., F. Harary. 2001 “The

Cohesiveness of Blocks in Social Networks:Node Connectivity and Conditional

Density.”

Sociological Methodology 2001, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 305-359. Blackwell

Publishers, Inc.,

White, D. R., Natasa Kejzar and Laurent Tambayong

2006 “Discovery of oscillatory dynamics of city-size distributions in world

historical systems” Presented at the International Institute for Applied

Systems Analysis,

Wilkinson, David. 1987 "Central civilization" Comparative Civilizations Review 17:31-59 (Fall).

_________ 1991 “Core, peripheries and

civilizations,” Pp. 113-166 in C. Chase-Dunn and T.D. Hall (eds.)

Core/Periphery Relations in Precapitalist Worlds.

_________2004 “The power configuration of the central world-system, 1500-700 BC” Journal of World-Systems Research 10,3: 655-720.