Synchronous

East-West

Urban and

Empire Upsweeps?

Christopher

Chase-Dunn, Hiroko Inoue, Alexis Alvarez, Kirk Lawrence and James Love

Institute for

Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

Frederic Teggart’s

Earlier studies found a curious interregional synchrony in the growth

and decline of large cities and empires. From about 500 BCE until about 1500 CE

cities and empires in East Asia and the West Asian/Mediterranean region appeared

to be growing and declining in the same periods, whereas intervening

To

be presented at the 2009 conference of the Social

Science History Association, Long Beach, CA Sunday, November 15: 10:15

AM-12:15 PM. Session

on Synchrony in History. V. DRAFT:

v. 11/17/09 xxxx words

This paper is available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows53/irows53.htm

New graphs of east/west cities and empires together.

Results of new search for east/west city

and empire synchrony. Also south

Upward sweeps stuff.

Diff between cycles and upsweeps.

Population stuff.

Partial correlations.

Adrefs turchin, upsweeps pap. Strogatz, lagged synch?

The growth and decline patterns and upward sweeps in the sizes of the

world’s largest cities and empires and their changing locations over the past

three millennia provide an important window on world history and sociocultural

evolution. Earlier research has shown what appears to be a fascinating

synchrony in the growth/decline phases of the largest cities and empires in

East Asia and in the West Asian/Mediterranean region (e.g. Chase-Dunn and Willard 1993; Chase-Dunn,

Manning and Hall 2000; Chase-Dunn and Manning 2002).

Using

data on the population sizes of largest cities and the territorial sizes of

largest empires it has seemed that medium-term growth/decline phases in

Earlier Findings

The population and areal sizes of

human settlements have increased since the emergence of sedentism around 12,000

years ago, and so have the sizes of the largest polities. But these general

long-term trends have been complicated by sequential middle-term declines in

the sizes of the largest cities and empires in all regions where urban and

polity sizes have been studied quantitatively. The population size estimates of

both modern and ancient cities are subject to large errors, and existing

compilations (Chandler 1987; Modelski 2003) badly need to be improved using

better methods of estimation (e.g. Pasciuti and Chase-Dunn 2002). The same can

be said for existing compilations of estimates of the territorial sizes of the

world’s largest empires (Taagepera 1978a, 1978b, 1979, 1997). When these

upgraded estimates become available, the East/West synchrony findings discussed

here will need to be reexamined with the improved data.

This phenomenon of East/West urban

and empire synchrony in middle-run growth/decline phases has been subjected to

several different methods of analysis. Both changes in the size of the largest

cities and changes in the steepness of the city-size distributions have been

used. And earlier studies have used two different kinds of spatial units of

analysis: constant regions and expanding political-military networks

(interaction networks of fighting and allying states). The East/West synchrony

has been found with both.

Detrending

is important because the long-term trend for city and empires sizes to increase

and so this alone would produce a positive correlation across distant regions.

Two different methods of detrending have been used: partial correlation

controlling for year and decadal change scores in which the earlier year is

subtracted from the later year. In the studies of empire sizes, empires that

touch adjacent macro-regions such as the Mongol Empire of the thirteenth

century CE have been removed from the analysis because they build in a degree

of synchrony by appearing in both regions at the same time. The synchrony

finding is strong even when this case has been removed from the calculations.

Frederick

Teggart’s (1939) path-breaking world historical study of temporal

correlations between events on the edges of the Roman and Han Empires argued

the thesis that incursions by Central Asian steppe nomads were the key to

East/West synchrony. An early study of city-size distributions in Afroeurasia

(Chase-Dunn and Willard 1993; see also Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: 222-223) found

an apparent synchrony between changes in city size distributions and the growth

of largest cities in

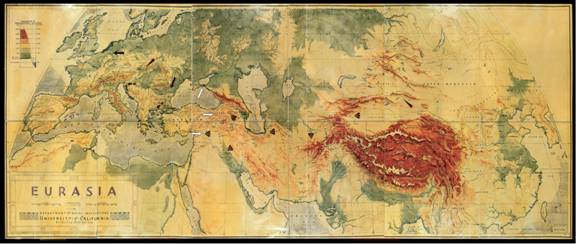

Figure 1: Sizes of Largest cities in

Figure 1: Sizes of Largest cities in

Comparable

other instances of distant systems that came into weak contact with one another

can be found. Within the Old World, the Mesopotamian and Egyptian core

regions were interacting with one another by means of prestige goods exchange

from about 3000 BCE until their political-military networks (state systems)

merged in 1500 BCE. Chase-Dunn, Pasciuti, Alvarez and Hall (2006) have already

examined this case for synchrony and have not found it, though the data on

Bronze Age city and empire sizes are very crude with regard to temporality and

accuracy. It is also possible to study the temporality of rise and fall and

oscillations among distant regions in the

Chase-Dunn,

Alvarez and Pasciuti (2005) also report detrended correlations between constant

regions for total population estimates taken from McEvedy and Jones

(1975). These total population estimates at 100-year intervals show rather high

growth/decline synchronies for several regions, also noted and discussed by

McEvedy and Jones (1975: 343-48).

The

East/West growth/decline synchrony seems to be rather robust, though better

estimates and finer temporal resolution of empire and city sizes might

challenge it. Interregional synchrony can be caused when two cyclical processes

get simultaneously reset, either by the same cause or by different causes. This

could be a one-shot occurrence. Or a process that is similarly cyclical can

cause synchrony. Candidates for the East/West synchrony are: climate change,

epidemic diseases, trade interruptions, or attacks by

Possible Explanations

Climate

change might affect regions by causing growth and decline of agricultural productivity

that in turn affects cities and empires. Perhaps because

But

climate change could also be involved in somewhat more complicated ways.

Central Asian steppe nomads (discussed below) were very susceptible to climate

change because their pastoral economy was greatly affected by changes in

temperature and rainfall. It is possible that climate change in

The

above hypotheses all conceive of climate change as an exogenous variable. But

it is also possible that city and empire growth change the climate. We know

that population growth and the development of complex civilizations changes the

environment by means of deforestation, soil erosion and the construction of

large irrigation systems (Diamond 2005). These changes may have affects on

climate. Modern studies show that the construction of large cities creates an

“urban heat island” that changes the environment in the immediate vicinity and

downwind of cities. Cities ingest and egest water, air and energy, and while

industrial cities do this on a much larger scale, earlier large cities also did

it to some extent. So large-scale agriculture and city-building may be causes of

climate change. Thus climate change may also be an endogenous variable.

We

know that Central Asian steppe nomads who raised horses and sheep periodically

formed large confederacies and attacked the agrarian empires of the East and

the West (Barfield 1989). Famous examples are the Huns and the Mongols. Perhaps

there was a cycle of Central Asian incursions that impacted upon the agrarian

civilizations of the East and the West and that accounts for the synchrony.

We

know that epidemic diseases spread across

We

also know that the Roman and Han empires were linked by long distance trade

routes across the Silk Roads and by sea. Perhaps interruptions to trade, or

periods of greater and easier trade flows, affected the Eastern and Western

civilizations simultaneously.

It

is also possible that two systems that are cycling independently can become

synchronized if they are both reset by a simultaneous accidental shock. This is

the so-called “Moran Effect” known in population ecology. We have discussed

this possibility in Chase-Dunn, Alvarez and Pasciuti (2006).

Figure

2 is a propositional inventory that includes most of the possible causes of

East/West synchrony.

Figure 2: Possible Causes of East/West Synchrony

Figure 2: Possible Causes of East/West Synchrony

More

research is required to find out which of these possible causes was responsible

for the East/West synchrony. We have found some evidence that temperature

changes in

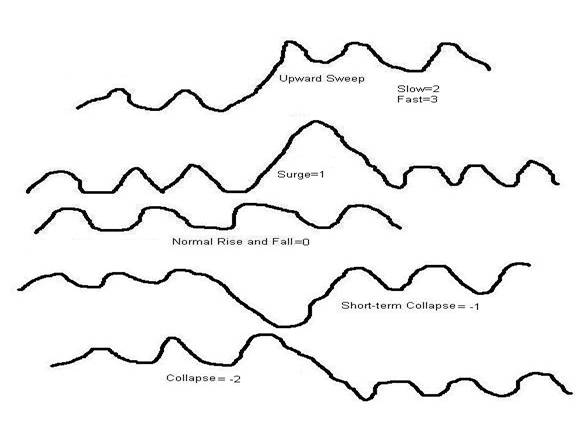

Cycles, Upward Sweeps, Collapses and Ceilings

We empirically identify “upward sweeps,” when the scale of cities and states dramatically increased. We review and synthesize explanations of chiefdom-formation, state-formation, empire-formation and the rise and fall of modern hegemonic core states in order to produce formal explanatory models. And we study the emergent characteristics that distinguish these different scales in order to comprehend how the processes have qualitatively evolved, and in order to consider what kinds of qualitative transformation might occur in the future. Our approach avoids the unscientific pitfalls of progressivist, functionalist, inevitabalist and teleological presumptions that have plagued many earlier approaches to socio-cultural evolution. We do not identify complexity and hierarchy with progress, but neither do we assume that they are the opposites of progress.

Our project compares relative small regional systems with larger continental and global systems, thus we must abstract from scale in order to examine changes in the structural patterns of small, medium and large human interaction networks. That said, we are also interested in medium term change in the scale of polities and settlements. We are not considering very long-term trends in this discussion. When an interacting set of polities or settlements is the unit of analysis nearly all systems oscillate in what we may term a normal cycle of rise and fall – the largest city or polity reaches a peak and then declines and then this or another city or polity returns to the peak again. We call this a normal cycle of rise and fall. It roughly approximates a sine wave, although few cycles that involve the behavior of groups of humans actually display the perfect regularity of amplitude and period found in the pure sine wave. In Figure 3 the cycle of rise and fall is half way down the figure and is labeled “normal rise and fall.” At the top of Figure 3 is a depiction of an upward sweep in which the size of the largest entity (state or city) increases by a factor of 2. Such a sweep may be relatively rapid or may be slow, and Rein Taagepera (1978a) contends the speed of the rise is often related to the sustainability of the upsweep, at least in the case of empires. Taagepera notices that empires that rise more slowly tend to last longer than those that rise abruptly. When an upward sweep is sustained and a new level of scale becomes the norm we call this an upward sweep. When it is temporary and returns to the old lower norm we call it a “surge” (see the 2nd line from the top in Figure 3). We also distinguish between three types of decline, a “normal” decline which is part of the normal rise and fall cycle, a short-term collapse in which a decline goes significantly below what had been established as the normal trough, and a sustained collapse in which the new lower scale becomes the norm for some extended period of time. Jared Diamond (2005) has examined the complex causes of a large collection of collapses, though he does not rely on quantitative indicators of collapse and he often focuses on particular societies or settlements that collapsed while ignoring neighboring societies or settlements that rose. If intersocietal interaction networks (world-systems) had been Diamond’s unit of analysis instead of single societies most of the cases of “collapse” that he studied would have been instances of normal rise and fall cycles rather than instances of system-wide collapse. A genuine collapse is when all the societies in a region go down and stay down for a long period. [2]

Figure 3: Types of medium-term scale change in the largest settlement or polity in an interacting region

Replication of the Earlier Synchrony Findings:

Cities

The

published studies that found synchrony between Eastern and Western

growth/decline phases of largest cities in each region were based on Tertius

Chandler’s (1987) compendium of estimates of the sizes of large cities. George

Modelski (2003) has produced a new and improved compendium of city size

estimates. For this paper we have used Modelski’s estimates to study upward

sweeps of city sizes and here we use them to once again examine the question of

East/West urban synchrony. The regions we are comparing are East Asia,

including

Figure 4 below

shows the results of the East/West comparision of largest cities and should be

compared with Figure 1 above that shows the same results using

Figure 4: East/West Largest Cities

Figure 5: East-West Largest City Annual Growth Rates

|

Correlations |

|||

|

|

|

W annual growth rate |

E annual growth rate |

|

W annual growth rate |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.181 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.215 |

|

|

N |

49 |

49 |

|

|

E annual growth rate |

Pearson Correlation |

.181 |

1 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.215 |

|

|

|

N |

49 |

49 |

|

Table 1: East-West Largest City Growth Rate Correlation

The Pearson’s r bivariate correlation coefficient for the East and West

largest annual growth rates is over the whole period from 1700 BCE to 1900 CE

is .18 (n=49) and this is not a significant correlation. We also have examined

the subperiod from 500 BCE to 1500CE during which an East-West city synchrony

was found based on

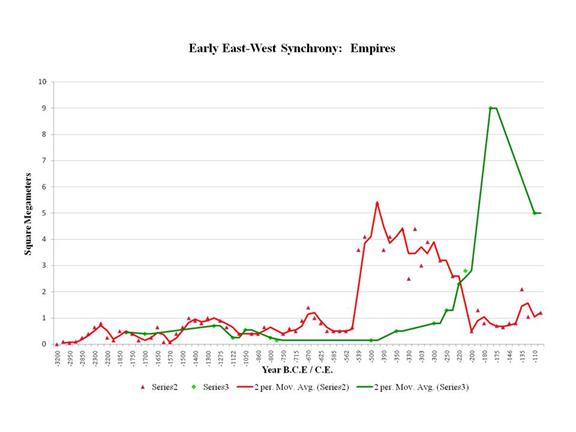

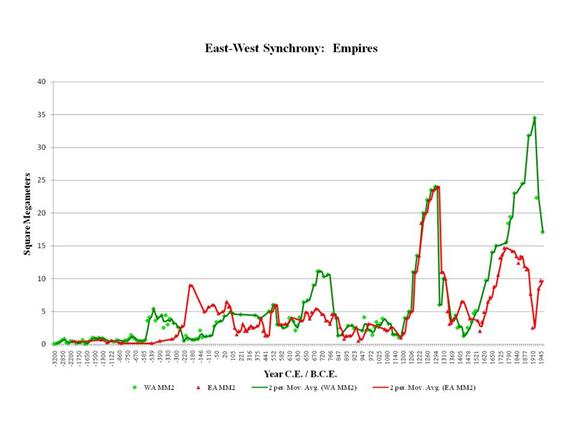

Replication of the Earlier Synchrony Findings:

Empires

Bibliography

Bairoch, Paul 1988 Cities

and Economic Development: From the Dawn of History to the Present.

Barfield, Thomas J. 1989 The

Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and

Barnes,

Ian, and Robert Hudson.1998.The History Atlas of

Boyle, Peter. 1977. The

Mongol World Empire, 1206 – 1370.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Alice Willard, 1993 "Systems of

cities and world-systems: settlement size hierarchies and cycles of political centralization,

2000 BC-1988AD" A paper presented at the International Studies

Association meeting, March 24-27,

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Susan Manning and Thomas D. Hall, 2000 "Rise

and Fall: East-West Synchronicity and Indic Exceptionalism Reexamined"

Social Science History 24,4: 721-48(Winter) .

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Susan Manning, 2002 "City systems and

world-systems: four millennia of city growth and decline," Cross-Cultural

Research 36, 4: 379-398 (November).

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

Alexis Alvarez, and Daniel Pasciuti 2005 "Power and

Size; urbanization and empire formation in world-systems" Pp. 92-113

in C. Chase-Dunn and E.N. Anderson (eds.) The Historical Evolution of

World-Systems.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher ,

Alexis Alvarez and Daniel Pasciuti, 2005 “World-systems in the

biogeosphere: three thousand years of urbanization, empire formation and

climate change.” Pp. 311-332 in Paul Ciccantell, David A. Smith and Gay Seidman

(eds.) Nature, Raw Materials, and Political Economy.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher,

Daniel Pasciuti, Alexis Alvarez and Thomas D. Hall 2006 “Growth/decline phases

and semiperipheral development in the ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian

world-systems” Pp. 114-138 in Barry K. Gills and William R. Thompson (eds.) Globalization and Global History.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher

and Thomas D. Hall 2006 “Global social change in

the long run” Chapter 3 in C. Chase-Dunn and Salvatore Babones (eds.) Global

Social Change.

Christian, David 2004 Maps

of Time.

Cioffi-Revilla, Claudio and David Lai 2001 “Chinese Warfare and Politics in the Ancient East Asian International System, ca. 2700 B.C. to 722 B.C.” International Interactions 26,4: 1-32.

Diamond, Jared 2005 Collapse.

Fagan, Brian 1999 Floods,

Famines and Emperors: El Nino and the Fate of Civilizations.

Basic Books.

Friedman, Jonathan and

Christopher Chase-Dunn 2005 Hegemonic Declines: Past and Present.

Lattimore, Owen 1940

Inner Asian Frontiers of

Haywood, John. 1998. Historical Atlas of the Ancient World. Oxforshire, OX: Andromeda Oxford Ltd.

_______

1998. Historical Atlas of the

Classical World. Oxforshire,

OX: Andromeda Oxford Ltd..

_______

1998. Historical Atlas of the

Medieval World. Oxforshire, OX: Andromeda Oxford Ltd..

_______

1998. Historical Atlas of the

Modern World. Oxforshire, OX: Andromeda Oxford Ltd.

Inoue, Hiroko 2009 “xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx”

Presented at the 2009 conference of the Social

Science History Association, Long Beach, CA Sunday, November 15: 10:15

AM-12:15 PM. Session on “Synchrony

in History.” https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows54/irows54.htm

Kradin, Nikolay N.. 2002.

“Nomadism, Evolution and World-Systems:

Pastoral Societies in Theories of Historical Development.” Journal of

World-Systems Research, 8,3.

Lee, J. S. 1931. “The Periodic Recurrence of Internecine

Wars in

Lee, J. S. (1933) in Studies Presented to Ts’ai Yuan P’ei on His Sixty-fifth Birthday Part I, ed. Fellows and Assistants of the Institute of History and Philology (Institute of History and Philology, Taipei), pp. 157-166.

McEvedy, Colin and

Richard Jones 1975 Atlas of World Population History.

Penguin.

McNeill, William H. 1976 Plagues

and

McNeill, John R. and

William H. McNeill 2003 The Human Web.

Modelski, G. (2003).

World cities: -3000 to 2000.

Pasciuti, Daniel and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2002 “Estimating the population sizes of

cities.” https://irows.ucr.edu/research/citemp/estcit/estcit.htm

Taagepera,

Rein 1978a "Size and duration of empires: systematics of size"

Social Science Research 7:108-27.

______

1978b "Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600

B.C." Social Science Research, 7 :180-96.

______1979

"Size and duration of empires: growth-decline curves, 600 B.C. to 600

A.D." Social Science History 3,3-4:115-38.

_______1997

“Expansion and contraction patterns of large polities: context for

Teggart,

Frederick J. 1939

Turchin,

Peter and Thomas D. Hall 2003 “Spatial synchrony among and within

world-systems: insights from theoretical ecology.” Journal of World-Systems Research 9,1:

37-64.

Turchin,

Peter and Sergey Nefadov 2009 Secular Cycles.

|

West |

|

|

East |

|

|

|

Year |

Largest City Population |

City Name |

Year |

Largest City Population |

City Name |

|

-1700 |

60 |

|

1700 |

40 |

Erlitou |

|

-1650 |

67 |

|

-1650 |

24 |

Erlitou |

|

-1600 |

75 |

Avaris |

-1600 |

24 |

BO (Yanshi) |

|

-1500 |

60 |

|

-1500 |

74 |

|

|

-1484 |

64 |

|

-1484 |

100 |

|

|

-1400 |

80 |

|

-1400 |

104 |

|

|

-1300 |

120 |

|

-1300 |

120 |

Yin |

|

-1200 |

160 |

Pi-Ramses |

-1200 |

120 |

Yin |

|

-1173 |

150 |

|

-1173 |

120 |

Anyang/Yinxu |

|

-1100 |

120 |

Pi-Ramses |

-1100 |

112 |

|

|

-1000 |

120 |

|

-1000 |

100 |

Haoqing |

|

-900 |

100 |

Memphis/Thebes/Babylon |

-900 |

125 |

Haoqing |

|

-800 |

100 |

Memphis/Thebes/Babylon |

-800 |

125 |

Haoqing |

|

-700 |

100 |

Memphis/Thebes/Babylon/Nineveh |

-700 |

100 |

|

|

-600 |

200 |

|

-600 |

200 |

Louyang |

|

-500 |

200 |

|

-500 |

200 |

|

|

-400 |

200 |

Carthage/Babylon |

-400 |

320 |

Xiatu |

|

-300 |

500 |

|

-300 |

350 |

Linzi |

|

-200 |

600 |

|

-200 |

200 |

|

|

-100 |

1000 |

|

-100 |

400 |

Changan |

|

1 |

800 |

|

1 |

420 |

Changan |

|

100 |

1000 |

|

100 |

420 |

|

|

200 |

1200 |

|

200 |

100 |

|

|

300 |

1000 |

|

300 |

250 |

|

|

400 |

800 |

|

400 |

300 |

|

|

500 |

500 |

|

500 |

500 |

Luoyang/Nanjing |

|

600 |

600 |

|

600 |

500 |

|

|

700 |

400 |

|

700 |

1000 |

Changan |

|

800 |

700 |

|

800 |

800 |

Changan |

|

900 |

900 |

|

900 |

200 |

Loyang/Kyoto |

|

1000 |

1200 |

|

1000 |

400 |

|

|

1100 |

1200 |

|

1100 |

1000 |

|

|

1150 |

1100 |

|

1150 |

1000 |

|

|

1200 |

1000 |

|

1200 |

1000 |

Kaifeng/Hangzhou |

|

1250 |

300 |

|

1250 |

1250 |

|

|

1300 |

400 |

|

1300 |

1500 |

|

|

1350 |

350 |

|

1350 |

1250 |

|

|

1400 |

360 |

|

1400 |

1000 |

|

|

1450 |

380 |

|

1450 |

1000 |

|

|

1500 |

400 |

|

1500 |

1000 |

|

|

1550 |

660 |

|

1550 |

1000 |

|

|

1600 |

700 |

|

1600 |

1000 |

|

|

1650 |

700 |

|

1650 |

844 |

|

|

1700 |

700 |

|

1700 |

688 |

|

|

1750 |

676 |

|

1750 |

900 |

|

|

1800 |

1117 |

|

1800 |

1100 |

|

|

1825 |

2100 |

|

1825 |

1350 |

|

|

1850 |

3750 |

|

1850 |

1648 |

|

|

1875 |

4850 |

|

1875 |

900 |

|

|

1900 |

6500 |

|

1900 |

1497 |

|

Table 2: Largest Cities in the East and the

Central System (numbers in blue are interpolations)