The Prehistory of

Money:

Protomoney and the meaning of exchange

in precontact

Southern California

Christopher

Chase-Dunn, Eugene N. Anderson,

Hiroko Inoue, and Alexis Álvarez

Institute for Research on

World-Systems

irows.ucr.edu

![]()

University of California-Riverside

v. 4-25-13 7120 words

An earlier version was presented at the annual meetings of the International Studies Association, San Francisco, April 3, 4pm, 2013. Session on “Money in World History” under the auspices of the World Historical Systems subsection of the International Political Economy Section of the International Studies Association

This

is IROWS Working Paper #80 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows80/irows80.htm

Abstract:

The evolutionary world-systems perspective sees semiperipheral

development as an important cause of human sociocultural evolution since the

Stone Age. In this paper we consider the roles that semiperipheral

polities may have played in the evolution of economic institutions in the stone age. We consider the emergence of protomoney

in a world-system of sedentary foragers in Southern California – an instance of

“money in world prehistory.”

Our theoretical perspective is the

institutional materialist evolutionary world-systems approach. This perspective

focuses on the ways that humans have organized social production and

distribution, and how economic, political, and religious institutions have

evolved in systems of interacting polities (world-systems) since the Paleolithic Age. We employ an underlying model in which

population pressures and interpolity competition have

always been, and still remain, important causes of social change, while the

systemic logics of social reproduction and growth have gone through qualitative

transformations (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997: Chapter 6). Thus we are both continuationists and transformationists.

A

stylized model of evolution of economic institutions

This

paper will focus mainly on the evolution of economic institutions and the roles

played by semiperipheral polities in the long-term

commodification of goods, wealth, labor and land. It uses the results of a

research project that studies the development of settlements and polities by

comparing regional world-systems and studying them over long periods of time.[1]

Here

we start with a brief stylized overview of our version of the evolution of

qualitatively distinct economic institutions and then we will elaborate and

qualify this model by examining some particular cases. In small-scale and

egalitarian systems social production is mainly based on shared conceptions of

norms that designate obligations among members of kin groups. Anthropologists

call this the kin-based mode of

production (Wolf 1997). It is based

on consensual moral orders that are imbedded in the mother tongues that people

learn from childhood. The mobilization

of social labor is primarily organized by means of family obligations based on

sharing and reciprocity. In some of these small-scale societies there is also

ritualized (sacralized) gifting that reinforces

alliances across households, settlements and sometimes across the boundaries of

independent polities (Douglas 1990). Most of these small-scale systems are

egalitarian in the sense that there may be some gender and age inequalities,

but there are few inequalities across households.

As sociocultural systems become more

complex, hierarchical kinship distinctions emerge that allow elites to use

institutionalized power to accumulate resources and to regulate the uses of

land and other valuable natural resources. Classes, forms of property and

prestige goods systems emerge that make it possible for the chiefly elite to

appropriate some of the labor and goods produced by commoners. In some of these

systems prestige goods emerge as a mechanism for symbolizing alliances among

village heads. Under some conditions prestige goods can evolve into proto-money

that serves as a more generalized symbol of value in trade networks. The

function of such intervillage exchange is to allow

surplus food to be acquired by villages that are experiencing a temporary

shortage. Intervillage and interpolity

trade serves as a substitute for raiding. In some systems prestige goods are

monopolized by the elites and are used to reward subalterns and to regulate

marriage, reinforcing the political hierarchy. These are called “prestige goods

systems” in the anthropological literature. But some egalitarian systems have

prestige goods or proto-money that mainly functions to ensure the provision of

goods for the general population during periods of shortage (e.g. the Wintu – see Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998). Small-scale societies also differ in the

extent to which private property exists. Many have only the usufruct in which

procurement locations are reallocated yearly by group decision-making, whereas

others designate property rights to individual sites that are inherited. But

even when individual or household rights to sites exist these are not commodified because they cannot be bought or sold.

In some systems specialized institutions of

regional control emerged within polities[2]

that were separate from, and over the top of, the kin-organized subsistence and

political economy. These were the first states, and the larger political

economy came to be based on various forms of tithing, taxation,

labor-appropriation and tribute. The general term for this kind of political

economy is the tributary mode of

accumulation. In some of the early

states primordial versions of commodified exchange

emerged such as lending money at interest and letters of credit, but most

exchange continued to be regulated by customary or politically-specified rules

and rates of exchange. [3]Interpolity (foreign) trade was usually carried out by

representatives of the state – what Polanyi (1957a) called “state-administered

trade.” But there were also some city-states that specialized in trade. The commodified institutions that emerged within early

tributary states were surrounded by powerful state-based institutionalized

coercion that regulated most of the economy. For thousands of years commodified forms of wealth, land, goods and labor existed

within political economies in which institutionalized coercion was the

predominant mode of economic regulation. But these commodified

forms nevertheless spread and developed within and between the tributary

empires. Tributary states became semi-commercialized and more and larger semiperipheral capitalist city-states specializing in trade

and commodity production emerged.[4]

Eventually a rather highly commodified system emerged in Western Europe during the

period after the fall of the Roman Empire in which the power of tributary

states was weak. A large number of semiperipheral capitalist city-states concentrated first on

the Italian peninsula and then spread across the Alps to the low

countries and then to the North Sea and the Baltic. These were agents of

an expanding Mediterranean and Baltic market economy. When territorial states

again emerged the most powerful of them were shaped by the existence of this

strongly commodified regional market economy, and the

emergent political elites were dependent on support from merchants and bankers

to meet the costs of raising armies in this very competitive interstate system.

The first territorial core state (not a semiperipheral

city-state) that was controlled by capitalists was the Dutch federation in the

17th century. This signaled the arrival of a capitalist world-system

in which the logic of profit-making instead of tribute-gathering had moved from

the semiperiphery to the core.

Money

in World Prehistory

The above stylized overview depicts

the emergence of money and market exchange as first occurring in the context of

Bronze Age state-based world-systems. But we want to have a closer look at

something of interest that happened in some stateless systems. Our tendency is

to side with the substantivists in the debate over whether or not

market exchange existed in stateless world-systems but we are willing to be

persuaded if there is evidence to the contrary. The substanvists contend that there was no market exchange before the emergence of

states, while the formalists think that all societies use the same logic

with regard to the rational individual calculation of gain and loss. Since

Karl Polanyi and his colleagues developed the substantivist

approach to economic sociology in the 1950s a debate has waned and waxed among

archaeologists, anthropologists, historians and sociologists over the "substantivist/formalist" question. The substantivists argue that exchange relations are embedded

in social structures, and that markets are historically created institutions,

not timeless logics expressing the truck-and-barter instincts of "economic

man". Polanyi distinguished between three qualitatively distinct forms of

integration: reciprocity, redistribution and market exchange. Important

statements of the substantivist position by Polanyi

and his colleagues are contained in Polanyi, Arensberg

and Pearson, eds. (1957). Marxist

variants have been argued by Sahlins(1972) and Wolf( 1982).

The formalists argue that economic rationality has similar properties in

all human societies, and they emphasize the importance of rational choice

approaches for nomadic foragers as well as contemporary consumers. The

formalist perspective has been defended by Blanton , Kowalewski, Feinman and Appel( 1981).Curtin's(1984) study of cross cultural trade

improves the formalist position by adding some new concepts: trade diasporas

and trade ecumenes.

Before the emergence of states human polities were small and not very internally stratified. The kin-based modes of production worked best in small-scale polities in which decisions could be made by consensus. Normative order requires a lot of consensus, and this works best when there are few socially structured inequalities. Sedentism and some degree of social complexity often emerged among some of those foraging peoples (hunter-gatherers) who occupied environments that provided enough food to sustain a settled population. These sedentary foragers developed methods of storing food for the off-season. They also sometimes developed trade networks that evened out the distribution of resources during years of drought or other climatic variations that affect the food supply. And trade allowed resources to move from ecological zones in which they were more abundant to zones in which they were scarce. Trade networks of this sort can be understood as an institutional substitute for raiding (Vayda 1967). Some of these systems developed proto-money in which a standardized symbol of value (usually beads made from sea-shells) came to be used as a form of social storage that facilitated intervillage exchange and allowed for the accumulation of tradable value that was less subject to spoilage than stored food.[5]

Most hunter-gatherers did not utilize

a standardized and durable symbol of value. Exchange within settlements was

most usually organized as sharing (generalized reciprocity) and gift-giving

(balanced reciprocity). Inter-settlement exchange was usually either balanced

reciprocity between groups or “negative reciprocity” in which enemy polities

tried to steal from one another (Sahlins

1972:193-196). The model of economic man used by most economists does not work

well in helping us to understand the cultural meaning of most exchange in such

cases. It is rather a sacralized moral order that regulates exchange. Sahlins points

out that kinship distance (from close to distant kinship relations) is

the main explanation for the distribution of sharing, balanced reciprocity and

negative reciprocity. Sharing is within

the household and with close kin in other households. Negative reciprocity,

including chicanery and theft, are also explained because these are the

appropriate behaviors toward those who are outside the moral order – non-kin

strangers (Sahlins 1972:196-199). Sahlins

(1972:196) says: “The several reciprocities from freely bestowed gift to

chicanery amount to a spectrum of sociability, from sacrifice in favor or

another to self-interested gain as the expense of another.”

Sahlins’s

(1974) concept of ‘balanced reciprocity” includes both the exchange of

equivalent gifts but also “transactions which stipulate returns of commensurate

worth or utility within a finite and narrow period. … The parties confront each

other as distinct economic and social interests (194-5). His main effort is to differentiate balanced

reciprocity from generalized reciprocity, not from market exchange, which he

does not really consider because he is studying Stone Age Economics. He

includes a lot of things in his category of “negative reciprocity” some of

which could be arm-length market exchange in which there is no personal

relationship between the buyer and the seller. For the problem of comprehending

the institutional nature of the social economy in prehistoric California

discussed below we need to make a clear distinction between balanced

reciprocity and market exchange. The main difference seems to be intent. In

balanced reciprocity the main intent is to be fair and to give as much as you

get in order to reinforce a social relationship. With market exchange the

intent is to make a profit. But this also requires a category of others that

are more distant than kin, but not yet enemies. It is this category that

emerges as the notion of kin-based solidarity expands to include co-ethnics,

co-nationals and eventually the whole human species.

Most

of the band and tribal level groups that Sahlins is

studying do all these forms of exchange without the use of a standardized

symbol of value (money). But there are some exceptions. In some regions tribal

groups do develop and extensively use a standardized medium of exchange. Sahlins (1972:227) calls this primitive money, by which he

means “those objects in primitive societies that have token value rather than

use value and that serve as means of exchange.”[6] Sahlins (227) then designates a few regions in which

small-scale societies are known to have made extensive use of primitive money:

“western and central Melanesia, aboriginal California and certain parts of the

South American tropical forest.” Sahlins’s claims

that these exceptions constitute instances of balanced reciprocity, not market

exchange.

Sahlins

contends that the use of primitive money for balanced reciprocity occurs under

certain conditions: a course-grained ecology in which rather different

ecological zones are close to one another, which encourages exchange; an

intermediate level of segmentary tribal organization

in which intervillage trade is between politically

autonomous but culturally related groups, “transactions in durables, more

likely to be balanced than food transactions(230)”. And he also says, “But more important, the

proportion of peripheral-sector exchange, the incidence of exchange among more

distantly related people, is likely to be considerably greater in tribal than

in band societies” (228).

Our purpose here is to examine the

idea that there may be a relationship between semiperipherality

and the emergence of specialized production of proto-money in world-systems of

sedentary foragers.

We

define market exchange in the way that economists do – a price-setting market

is one in which the terms of trade (prices) are set by competitive buying and

selling among sets of purchasers and sellers who are trying to make a profit on

the exchanges. Sharing, reciprocity,

gift-giving, generalized exchange and the payment of tribute and taxes are not

market exchange. Non-market exchanges rates sometimes reflect transportation

and production costs, but this is usually because the exchangers are trying to

be generous, and generosity involves guesses about how much effort was needed

to obtain a valued thing. A market economy is one in which a majority of the

goods and services that are necessary to the everyday lives of average persons

are obtained by marketized buying and selling.

Most egalitarian world-systems of

sedentary foragers do not have stable core/periphery hierarchies in which some

polities are able extract surplus product from other polities (e.g.

Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998). But there is often a condition of core/periphery

differentiation in which polities with greater population density and larger

settlements frequently interact with polities with less population density and

smaller settlements, or with nomadic peoples.

Semiperipherality in a situation of core/periphery

differentiation is constituted by having relative middle-sized settlements with

middle-levels of wealth and that mediate relations between a core region and a

peripheral region.

In this paper we examine the

hypothesis that semiperipheral communities may have

been agents of the development of proto-money in small-scale world-systems. The

regional world-systems of indigenous northern and southern California are used

to test this hypothesis. In both regions the manufacturing of primitive money became

a specialized activity of households that were in settlements that were of

medium size relative to the sizes of those settlements that were larger and

those that were smaller in adjacent regions.[7]

Very

Small World-Systems in California

In both Northern and Southern California different kinds of proto-money emerged as important for intervillage exchange networks. In the north the Pomo villages located near Clear Lake in the Coast Range in between the Sacramento River Valley and the coast of the Pacific Ocean specialized in the production of clam disk shell beads.[8] They obtained clam shells from the coast near Tamales Bay by means of direct procurement and by trade with indigenes living on the coast,[9] and they labored to turn these shells into small disks with a hole drilled in the center. These disk beads were then strung and a standard length of strung beads came to serve as a symbol of value in an exchange network that extended both north and south in the Sacramento River Valley and the adjacent mountain ranges. The Pomo were hill dwellers living adjacent to the valley-dwelling Patwin, who had some of the largest settlements in indigenous California – up to about 1500 residents – along the lower Sacramento River. The Pomo villages were large but not as large as those of the Patwin. The Pomo were a linguistic group that spoke spoke different languages within the Pomo language family of the Hokan language phylum.[10] As with other indigenous peoples of California, they were organized politically as “tribelets” – politically autonomous villages or small affiliated groups of villages that occasionally made war on one another but that also engaged in extensive trade in which food and other valuables were exchanged (Kroeber 1925). Prestige goods moved rather long distances by means of down-line-trade, moving from group to group. There were no long distance traders because it was dangerous to pass through the territories of non-allied groups. Long distance procurement treks were sometimes undertaken, but they were also dangerous. The most common cause of war was trespass, in which resources that were collectively owned by a tribelet were used without permission by outsiders (Chase-Dunn and Mann 1998: Chapter 8).

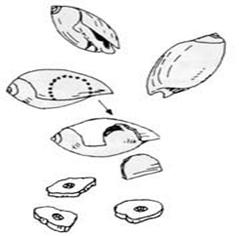

In Southern California the Chumash

villages along the Santa Barbara coast, inland in the valleys and Coast Range,

and on the northern Channel Islands were the center of an exchange network that

connected them with the Southern Channel Islands as well as with people living

in the San Joaquin Valley (the Yokuts) and the

regions south of the San Gabriel Mountains and extending across the Mohave

Desert into what is now Arizona and New Mexico. This exchange network used disk

beads as a standardized medium of value. The beads were manufactured from Olivella sea shells mainly by residents of the Northern

Channel Islands. The Olivella shell beads were

drilled with chert drills that were also manufactured

mainly by people dwelling on Santa Cruz Island where there were quarries

containing a kind of chert that was particularly

appropriate for making the drills. The shells were cut and roughly shaped, and

then drilled and strung and then sanded to roundness by rolling on a rough flat surface

until they were small and uniform. This took a lot of work, and households on

the Channel Islands spent a good deal of their labor time producing these

beads, which they then used to obtain vegetable foods from the mainland that

were in short supply on the islands.

The

Chumash were a linguistic group that spoke related, but sometimes

unintelligible dialects of a family of related languages. The largest Chumash villages were located

near fresh water sources on the coast. Villages on the islands and in the

interior were smaller. We contend that

both the Pomo villages and some of the Island Chumash villages were semiperipheral in a system that had a settlement size

hierarchy as well as differences in wealth. The largest villages on the

northern Channel Islands were smaller than those on the mainland coast, but

there were also smaller villages on the islands. The villages on San Miguel

Island, the northern-most of the Channel Islands, were quite small (Figure 1

below from Gamble 2006:71 Figure 7). [11]

We contend that the Island Chumash in the larger villages on Santa Cruz Island

were in a semiperipheral position vis-à-vis the

smaller villages on the islands and the larger villages of the mainland coast.

And we also contend that the Pomo were in a semiperipheral

position vis-à-vis the smaller villages of adjacent Coast Range peoples and

vis-à-vis the larger Patwin villages in the lower

Sacramento River Valley (King 1978).[12] Population density is an important dimension

of power in systems in which warfare and production technologies are not very

different across groups. The winners in intergroup conflicts are those that are

able to quickly mobilize larger numbers of fighters to either attack or protect

from attack. Village size is the best indicator of population density in settlement

systems of the kind found in indigenous California.

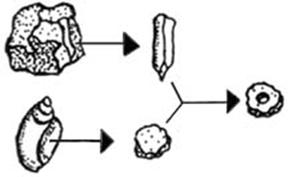

Figure 1:

Population estimates of village size based on mission register documents.

Source: Gamble 2006: 71.

It is in dispute as to whether or not the core polities with larger villages were exploiting the non-core regions in this Southern California system. Sahlins contends that the institutional nature of exchange among polities of this kind is usually balanced reciprocity, which requires equal exchange. Clarence King (1976) and Lynn Gamble (2008) contend that an important part of the Chumash economy was based on market exchange, which may also imply equal exchange. But Mikael Fauvelle (2011) contends that the island/mainland Chumash relationship was “asymmetrical exchange” because the mainlanders were able to use their alleged monopoly of asphaltum, a necessity for the building and repair of plank canoes, to skew the terms of trade in their favor. Both the institutional nature of the exchanges and the question of equal or unequal exchange are at issue in the case of the Island/Mainland Chumash political economy. Whether or not the trade was unequal, all agree that villages were larger on the coast than they were in the interior or on the islands. And Gamble (2006:188) says that the islanders were poorer and held fewer and smaller trade feasts. [13]

It is widely agreed in the

anthropological literature that generalized reciprocity (sharing) and balanced

reciprocity (gift-giving) were the major institutional

forms of exchange in both Northern and Southern California. Proto-money (clam

disk shell beads) in Northern California was primarily owned and exchanged by

village headmen who wore it to symbolize their status (a prestige good) and

used it to trade for food and other needed materials from the head-men of

nearby villages. Exchanges of this kind took place primarily at trade feasts in

which groups from the surrounding region were invited to eat, dance and gamble. This was mainly balanced reciprocity in which

headmen were striving to demonstrate their generousity.

Anthropologists contend that the

complexity and stratification in Chumash society was reproduced by a system of

redistribution in which chiefs and members of the elite ‘antap

societies and canoe-owners were able to extract food and other resources from

non-elites. The Chumash trade feasts required chiefs from other villages to

bring substantial amounts of food to the celebrations to help feed the

attendees and to pay the dancers. The feast-holders’ reputation for hospitality

was an important product of these events, but there was also an element of

coercion. For mortuary ceremonies the ‘antap society

allegedly appointed a “poisoner” whose job it was to poison one of the

attending wealthy men from another village in order to motivate the provision

of substantial contributions (Gamble 2008:198). Redistribution was also evident

in the Brotherhood of the Tomol, the craft guild that

both constructed and owned the plank canoes (tomol)

that made it possible to fish in the ocean and to carry out the trade with the

Channel Islands. When a load of fish was brought home, the whole load was taken

to the canoe-owner who then distributed it to his subalterns. So both reciprocity

and redistribution were important parts of the Southern California political

economy.

But what about market exchange? Clarence King (1976) and Lynn Gamble (2008)

contend that market exchange was a significant component of the Chumash

economy. Of course it is easy to suppose that observers from a highly

commercialized economy (ours) might project their own institutional meanings on

to a system that was in reality quite different from their own. The very existence of proto-money suggests

market exchange. But did market exchange really exist in the indigenous Chumash

system, and if it did, was it a significant component of the whole

economy? The archaeological evidence

clearly shows the emergence of the shell bead industry and trade network and

the concentration of production on the Channel Islands. Archaeologists also note that there was a

trend over time toward the increased production of callus beads, in which a

harder and thicker portion of the Olivella shell was

used to produce a distinctive kind of bead with a bump that was easily

perceived when the beads were strung together (Pletka

2004). This bead was perceived as more valuable in the Chumash system.

Figure 2:

Part of the process of making Olivella disk beads

using a stone drill

The standard length of strung beads

was the “ponco” which was two turns of the string

about the wrist and the extended third finger (Gamble 2008:223; see also King

1976:297). Jose Longinos Martinez wrote in 1792: “The

value of the ponco depends on the fineness and color

of the beads, ours being held in the greatest of esteem; it also depends on

their abundance and their price relative to ours” (quoted in Gamble 2006:223).

Martinez is referring to the glass beads introduced by the Spaniards for

purposes of trading with the Chumash as “ours.”

But this quotation implies that different kinds of beads had different

exchange values and this was likely to have been the case before the arrival of

the Spaniards as well. This would explain why the islanders shifted production

from the bead made from the thin part of the shell wall to the thicker callus

beads. It was like printing five dollar bills instead of one dollar bills. Or

at least this is what we would tend to assume.

Gamble specifies what she thinks

would have to be the case if true market exchange were to be present in the

Chumash system: “Were the principles of supply and demand present in Chumash

transactions both within their boundaries and beyond? Were individuals free to

exchange beads for goods that they needed and desired, or was the release of

beads controlled?” (2008:227).

Recall that Polanyi (1957b) conceives of a

market system as one in which average persons can purchase everyday goods and

services. Both King and Gamble claim that this was the case in the Chumash

system, but what is the evidence that they use to support this claim? Gamble mentions “early ethnohistoric

accounts” and then goes on to quote John P. Harrington’s informants such as

Fernando Kitsepawit Librado a VentureÑo Chumash who Harrington befriended in about

1910, more than 100 years after the Chumash system had been radically

transformed by Eurasian epidemic diseases, Franciscan missionization,

the establishment of a Presidio in Santa Barbara, and the founding and

expansion of haciendas that employed the Indians as vacqueros (cowboys). Librado

had worked for a hacienda

in Ventura. Harrington’s latter-day informants provided valuable information

about the Chumash languages, and the stories they told about the old times were

suggestive, but disentangling indigenous versus colonial institutional forms of

economic exchange from the statements of such informants is exceedingly

difficult because the “memory culture” is likely to have gotten distorted by

the institutional structure of the colonial culture.

Of

greater value are the reports of observed behavior by the early explorers and

observers in the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Both Gamble and King quote

instances in which Spanish soldiers were able to purchase food and prestige

goods such as carved soapstone bowls from the Chumash using glass beads. These

events support the notion that some market exchange did exist in the in the

Chumash system.

Gambling is mentioned by Jose Longinos Martinez (quoted in Gamble 2006:223) and is an important

activity in Chumash mythology (e.g. Blackburn 1975: 91-3). This may be relevant

to the issue of whether or not protomoney was used by

other than chiefs in both Northern and Southern California. In Northern

California games of chance were an important recreational activity that was

engaged in by the general population during trade feasts. This is relevant for

the question of whether or not proto-money was used for market exchange by

non-chiefs. If it was used for gambling

by non-chiefs it may have also been used at least some of the time for the

purchase of goods and services from non-kin or distant kin.[14]

King (1976:293) quotes Harrington’s

statement from Fernando Librado as follows:

At many of the villages on

the coast of the mainland, as many as half of the population talked the Santa

Cruz Island language. The Santa Cruz Island people lived permanently in

these villages, like permanent colonists. During the time of harvest, when the

acorns, etc. were ripe, many Indians came from the island to the mainland and

went inland to gather the wild fruit.

Librado’s

statement may mean that there were members of the same kin groups residing on

both the islands and the mainland. If this were true much of the

island/mainland exchange could have been sharing or gift-giving among close

kin, like the celebrated “vertical archipelago” in the Andes (Murra 1980). And the practice of direct procurement on the

mainland by islanders also demonstrates another alternative to provisioning

beside either market exchange or balanced reciprocity.

The questions is how significant was

the existence of some market exchange for the whole nature of the social

economy? Unfortunately it is probably impossible to even make an educated guess

about how much of the food and everyday raw materials of average persons were

obtained by means of market exchange.

The contention by Gamble and King that the Chumash system was more

commercialized than was the system in Northern California is quite plausible,

but Gamble also says “I believe that the Chumash in many ways were close to

being a capitalist society despite the fact that they were non-agriculturalists

and lacked a state-level political organization (2008:234). While we are

sympathetic to a broader definition of capitalism than that used by Marx

(commodity production by means of wage labor) we are not willing to stretch the

notion to include the kind of economy that existed in Southern California

before the arrival of the Europeans. Gamble (2006:234-235) use Dalton’s (1965)

distinction between “marketless, ”“market-dominated”

and “peripheral markets “ in which some market exchange and money exist but

they do not constitute a major proportion of the whole of production and

distribution. She adopts the position that the Chumash social economy was an

instance of “peripheral markets.” Gamble

(2006:235) also notes that other anthropologists agree the production of disk

beads by households on the Channel Islands was probably not monitored or

directly controlled by political elites.

Regarding the issue of supply and

demand, we have already mentioned Sahlins’s

discussion of how transportation costs and labor time can play a role in

gift-giving exchanges because a successful performance of hospitality requires

knowledge of the scarcity and labor exerted to produce the goods that are being

given. Both gift-giving and market exchange require knowledge of the relative

value of goods. This can be manifested as the functioning of supply and demand

even in the absence of market exchange.

The existence of even a small degree

of market exchange in Southern California would seem to constitute a major

challenge to the Polanyian substantivist

approach to the evolution of economic institutions in which markets did not

emerge until the state-based political economies of the Iron Age. But

as with the Kultepe tablets discussed below, Polanyi

might have been wrong about the timing and location of the emergence of market

relations, but still right about the general notion that an

important class of human societies do not have markets and that markets

are institutional inventions that emerged under certain conditions. The Kultepe tablets pushed this invention back from the Iron Age

to the Bronze Age. The Chumash may push

it back to complex sedentary foragers of the Stone Age.

If we are right that semiperipheral polities in both Northern and Southern

California were the main specialists in the production of proto-money, what

might have been the forces that brought this to be? Recall that Sahlins’s

(1974:227-30) discussion of primitive money mentions that a standardize medium

of exchange may be useful when ecological differences encourage a lot of

exchange between distant kin or non-kin.

He also mentions the functionality of a durable symbol of value when the

exchange “between coastal in inland people where an exchangeable catch of fish

cannot always be met by complementary inland products “(230). Fish were involved in both

the Pomo/Patwin and the Chumash island/coastal

trades. Islanders specialized in fishing

and the Patwin harvested the huge migratory flows of anadromous fish (salmon and steelhead) in the Sacramento

River. Both cultures dried fish, to make

it more long-lasting as a source of protein, but fresh fish must have also been

an important trade item. Semiperipherality, as

indicated by relatively less population density and less social hierarchy, is

also related to ecological marginality. Hill people are usually poorer than

valley people, and island people are usually poorer than coastal people because

the territories that they inhabit have fewer natural resources that can be used

by humans as food. In order to have something to exchange for needed food items

(vegetable foods in the case of the island Chumash) the semiperipheral

peoples have a greater incentive to spend their labor time producing

proto-money.

But did these semiperipheral

peoples innovate the use of proto-money or did they actively encourage its

wide-spread use in intervillage exchange? The shift

from thin to thick callus bead production may indicate that there was an

element of agential innovation, or at least early implementation, in the case

of the island Chumash. And was there a

similar phenomenon in the earlier shell bead networks that Bennyhoff

and Hughes (1982) found linking Northern California with the western Great

Basin? Archaeological evidence could be

useful for shedding further light on these questions.

References

Arnold,

Jeanne E. 1993 “Labor and the rise of complex hunter-gatherers” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 12:75-119.

______________(ed.) 2004 Foundations

of Chumash Complexity. Perspectives in California

Archaeology, Volume 7.

Los Angeles: Cotsen

Institute of Archaeology, University of California-Los Angeles.

_____________2012

“Prestige trade in the Santa Barbara channel region” California Archaeology 4,1: 145-148.

Arrighi, Giovanni 2006

“Spatial and other ‘fixes’ of historical capitalism” Pp. 201-212 in C.

Chase-Dunn and S. Babones

(eds.) Global Social Change.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Blanton,

Richard E. and Lane F. Fargher 2012 “Market

Cooperation and the Evolution of the Pre-Hispanic

Mesoamerican World-System” in

Salvatore Babones and Christopher Chase-Dunn (eds.) Routledge Handbook of

World-Systems

Analysis: Theory and Research London: Routledge

Brown, Alan K. (ed.) A Description of Unpublished Roads. San Diego, Ca; San Diego State University

Press.

Chapman,

Anne C. 1957 “Port of trade enclaves in Aztec and Maya civilizations” Pp.

114-153 in Karl Polanyi, Conrad

M. Arensberg

and Harry W. Pearson, Trade and Markets

in the Early Empires. Chicago: Henry Regnery.

Chase-Dunn,

C. 1988. "Comparing world-systems: Toward a

theory of semiperipheral development," Comparative

Civilizations Review, 19:29-66, Fall.

Chase-Dunn, C. 2013

“The evolution of systemic logics” https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows77/irows77.htm

Chase-Dunn,

C. and Kelly M. Mann 1998 The Wintu and Their

Neighbors. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Chase-Dunn,

C. and E.N. Anderson (eds.) 2005. The Historical

Evolution of World-Systems. London: Palgrave.

Chaudhuri, K. N. 1985 Trade and Civilisation

in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History

from the Rise of Islam to 1750.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Curtin,

Philip D. 1984 Cross-Cultural Trade in World History

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Douglas,

Mary 1990 “Foreword” to The Gift by

Marcel Mauss, Translated by W.D. Halls, New York:

Norton.

Earle, Timothy 2002 Bronze Age Economics: The beginnings of

political economies. Boulder, CO:

Westview.

Ekholm, Kasja

and Jonathan Friedman 1982 “’Capital’ imperialism and exploitation in the

ancient world-systems” Review

6:1 (summer): 87-110.

Frankenstein, Susan. 1979 "The Phoenicians in the Far West: A

Function of Neo-Assyrian imperialism." Pp. 263-94

in Power and Propaganda: A Symposium on Ancient Empires, Mogens T. Larsen (ed.).

Copenhagen: Akademisk

Forlag.

Friedman, Jonathan 1998 System, Structure and Contradiction: the evolution of Asiatic Social

Formations. Walnut Creek, CA;

Altamira Press.

_______________

and Michael Rowlands. 1977. "Notes Towards

an Epigenetic Model of the Evolution of 'Civiliza

tion'." Pp. 201-278 in The Evolution of Social Systems, edited by J. Friedman and M.

J. Rowlands. London:

Duckworth

(also published in same title and pages, University of Pittsburgh Press,

Pittsburgh, 1978).

Gamble,

Lynn H. 2008 The Chumash World at European Contact. Berekeley: University of California Press.

Graeber, David 2011 Debt: the first 5000 years. Brooklyn,

N.Y. : Melville House

Johnson, John R 1982 “An Ethnohistoric Study of the Island Chumash” Master’s Thesis, Dept

of Anthropology,

University of California-Santa

Barbara.

_____________ 1988 “Chumash

Social Organization: An Ethnohistoric Perspective”. PhD Dissertation, Department

of Anthropology, University of California-Santa Barbara.

King, Chester 1976 “Chumash Inter-village

Economic Exchange” Pp. 289-318 in Lowell J. Bean and Thomas C.

Blackburn

(eds.) Native Californians: A Theoretical

Retrospective. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press.

Lane, Frederic C. 1979 Profits from Power: readings in protection rent and

violence-controlling enterprises.

Albany: State University of

New

York Press

Larsen, Mogens T. 1976 The Old

Assyrian City State and Its Colonies. Copenhagen: Akademisk

Forlag

Lieberman,

Victor. 2003. Strange

Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global

Context, c. 800-1830. Vol. 1:

Integration on the

Mainland. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

McKillop, Heather 2005 In Search of the Maya Sea Traders.

College Station, Texas: Texas A and M University

Press.

Murra, John Victor 1980 [1955] The Economic Organization of the Inca State. Research in Economic

Anthropology,

Supplement 1, Greenwich, Conn.: Jai

Press.

Polanyi,

Karl. 1957a. "Marketless

trading in Hammurabi's time." Pp. 12-26 in Trade and Market in the Early Empires, edited

by Karl Polanyi, Conrad M. Arensberg,

and Harry W. Pearson. Chicago: Regnery.

_____. 1957b. "Aristotle Discovers the

Economy." Pp. 64-96 in Trade and Market in the Early Empires,

edited by Karl

Polanyi, Conrad M. Arensberg, and Harry

W. Pearson. Chicago: Regnery.

Reid,

Anthony. 1988. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680. Vol. I, The Lands below the Winds. New Haven:

Yale

University Press.

Sabloff, Jeremy and William J.

Rathje 1975 A Study of Changing

Pre-Columbian Commercial Systems. Cambridge: Peabody

Museum of

Archaeology and Ethnology. Harvard University.

Sahlins, Marshall 1972 Stone

Age Economics. Chicago: Aldine.

Scheidel, Walter and Sitta Von Reden (eds.) The Ancient Economy. New York: Routledge.

Stein,

Gil J. 1999 Rethinking World-Systems:

Diasporas, Colonies and Interaction in Uruk

Mesopotamia.

Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Taussig, Michael T. 1980 The Devil and

Commodity Fetishism in South America. Chapel Hill: North

Carolina University Press.

Vayda,

Andrew P. 1967 “Pomo trade feasts” Pp. 494-500 in Tribal and Peasant Economies edited by

George

Dalton. Garden City, NY: Natural History

Press.

Wheatley,

Paul. 1961. The

Golden Khersonese:

Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D.

1500. Kuala

Lumpur: Univ. of Malaya Press.

Wolf

,

Eric 1997 Europe and the People Without History, Berkeley: University of California Press.